Studies in Higher Education

Subject Area and Category

Publication type.

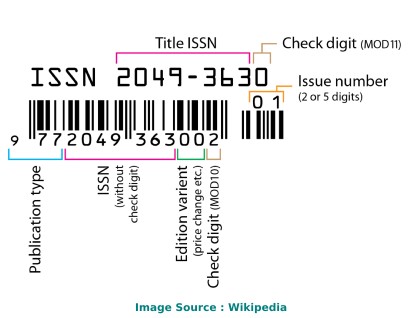

03075079, 1470174X

Information

How to publish in this journal

The set of journals have been ranked according to their SJR and divided into four equal groups, four quartiles. Q1 (green) comprises the quarter of the journals with the highest values, Q2 (yellow) the second highest values, Q3 (orange) the third highest values and Q4 (red) the lowest values.

The SJR is a size-independent prestige indicator that ranks journals by their 'average prestige per article'. It is based on the idea that 'all citations are not created equal'. SJR is a measure of scientific influence of journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where such citations come from It measures the scientific influence of the average article in a journal, it expresses how central to the global scientific discussion an average article of the journal is.

Evolution of the number of published documents. All types of documents are considered, including citable and non citable documents.

This indicator counts the number of citations received by documents from a journal and divides them by the total number of documents published in that journal. The chart shows the evolution of the average number of times documents published in a journal in the past two, three and four years have been cited in the current year. The two years line is equivalent to journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

Evolution of the total number of citations and journal's self-citations received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. Journal Self-citation is defined as the number of citation from a journal citing article to articles published by the same journal.

Evolution of the number of total citation per document and external citation per document (i.e. journal self-citations removed) received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. External citations are calculated by subtracting the number of self-citations from the total number of citations received by the journal’s documents.

International Collaboration accounts for the articles that have been produced by researchers from several countries. The chart shows the ratio of a journal's documents signed by researchers from more than one country; that is including more than one country address.

Not every article in a journal is considered primary research and therefore "citable", this chart shows the ratio of a journal's articles including substantial research (research articles, conference papers and reviews) in three year windows vs. those documents other than research articles, reviews and conference papers.

Ratio of a journal's items, grouped in three years windows, that have been cited at least once vs. those not cited during the following year.

Leave a comment

Name * Required

Email (will not be published) * Required

* Required Cancel

The users of Scimago Journal & Country Rank have the possibility to dialogue through comments linked to a specific journal. The purpose is to have a forum in which general doubts about the processes of publication in the journal, experiences and other issues derived from the publication of papers are resolved. For topics on particular articles, maintain the dialogue through the usual channels with your editor.

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2022. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

2023-2024 Best Education Schools

Ranked in 2023

A teacher must first be a student, and graduate education program rankings can help

A teacher must first be a student, and graduate education program rankings can help you find the right classroom. With the U.S. News rankings of the top education schools, narrow your search by location, tuition, school size and test scores. Read the methodology »

For full rankings, GRE scores and student debt data, sign up for the U.S. News Education School Compass .

Here are the 2023-2024 Best Education Schools

Teachers college, columbia university, university of michigan--ann arbor, northwestern university, university of pennsylvania, university of wisconsin--madison, vanderbilt university (peabody), stanford university, university of california--los angeles, harvard university.

SEE THE FULL RANKINGS

- Clear Filters

New York , NY

- # 1 in Best Education Schools (tie)

$1,913 per credit (full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

$1,913 per credit (part-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

3,192 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The education school at Teachers College, Columbia University has a rolling application deadline. The application fee... Read More »

TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

$1,913 per credit (full-time)

$1,913 per credit (part-time)

ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

Average gre verbal (doctorate).

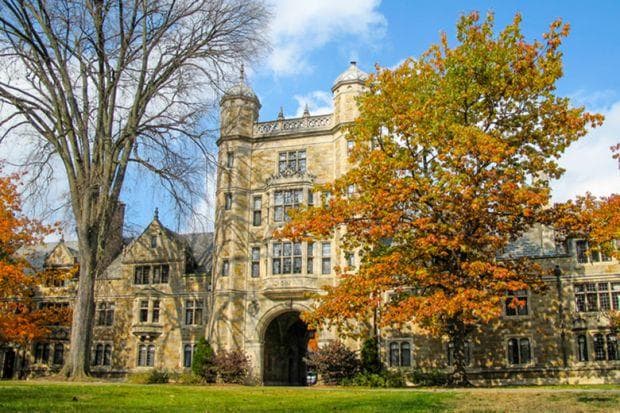

Ann Arbor , MI

$26,392 per year (in-state, full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

$53,178 per year (out-of-state, full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

404 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The School of Education at University of Michigan--Ann Arbor has a rolling application deadline. The application fee... Read More »

$26,392 per year (in-state, full-time)

$53,178 per year (out-of-state, full-time)

Evanston , IL

- # 3 in Best Education Schools (tie)

N/A TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

229 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University has an application deadline of Dec. 4. The... Read More »

Philadelphia , PA

$1,786 per credit (full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

$1,786 per credit (part-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

1,105 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The School of Education at University of Pennsylvania has an application deadline of Dec. 1. The application fee for... Read More »

$1,786 per credit (full-time)

$1,786 per credit (part-time)

Madison , WI

$10,728 per year (in-state, full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

$24,054 per year (out-of-state, full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

765 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The School of Education at University of Wisconsin--Madison has an application deadline of Nov. 30. The application fee... Read More »

$10,728 per year (in-state, full-time)

$24,054 per year (out-of-state, full-time)

Nashville , TN

- # 6 in Best Education Schools

$2,215 per credit (full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

$2,215 per credit (part-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

809 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The Peabody College of Education and Human Development at Vanderbilt University (Peabody) has an application deadline... Read More »

$2,215 per credit (full-time)

$2,215 per credit (part-time)

Stanford , CA

- # 7 in Best Education Schools (tie)

$56,487 per year (full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

343 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The application fee for the education program at Stanford University is $125. Its tuition is full-time: $56,487 per... Read More »

$56,487 per year (full-time)

Los Angeles , CA

$11,700 per year (in-state, full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

$26,802 per year (out-of-state, full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

701 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The education school at University of California--Los Angeles has an application deadline of Dec. 1. The application... Read More »

$11,700 per year (in-state, full-time)

$26,802 per year (out-of-state, full-time)

Cambridge , MA

- # 9 in Best Education Schools (tie)

707 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The application fee for the education program at Harvard University is $85. The Graduate School of Education at Harvard... Read More »

New York University (Steinhardt)

$51,186 per year (full-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

$2,020 per credit (part-time) TUITION AND FEES (DOCTORATE)

1,752 ENROLLMENT (FULL-TIME)

The Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development at New York University (Steinhardt) has an... Read More »

$51,186 per year (full-time)

$2,020 per credit (part-time)

U.S. News Grad Compass

See expanded profiles for more than 2,000 programs. Unlock entering class stats including MCAT, GMAT and GRE scores for business, medicine, engineering, education and nursing programs.

Advertisement

The institutionalization of rankings in higher education: continuities, interdependencies, engagement

- Open access

- Published: 05 April 2023

- Volume 86 , pages 719–731, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jelena Brankovic ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0485-9096 1 ,

- Julian Hamann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3196-908X 2 &

- Leopold Ringel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4894-3337 1

3243 Accesses

4 Citations

33 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this article, we introduce the special issue of Higher Education that centers on the question of the institutionalization of rankings in higher education. The article has three parts. In the first part, we argue that the grand narratives such as globalization and neoliberalism are unsatisfactory as standalone explanations of why and how college and university rankings become institutionalized. As a remedy, we invite scholars to pay closer attention to the dynamics specific to higher education that contribute to the proliferation, persistence, and embeddedness of rankings. In the second part, we weave the articles included in the issue into three sub-themes—continuities, interdependencies, and engagement—which we link to the overarching theme of institutionalization. Each contribution approaches the subject of rankings from a different angle and casts a different light on continuities, interdependencies, and engagement, thus suggesting that the overall story is much more intricate than often assumed. In the third and final part, we restate the main takeaways of the issue and note that systematic comparative research holds great promise for furthering our knowledge on the subject. We conclude the article with a hope that the special issue would stimulate further questioning of rankings—in higher education and higher education research.

Similar content being viewed by others

The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems.

Simon Marginson

At all costs: educational expansion and persistent inequality in the Philippines

Karol Mark Ramirez Yee

Institutional Quality and Education Quality in Developing Countries: Effects and Transmission Channels

Benjamin Kamga Fomba, Dieu Ne Dort Fokam Talla & Paul Ningaye

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Blunt facts?

Over the course of the past century, rankings have proliferated dramatically. Loosely understood as a specific way of quantifying and presenting performance comparisons (Werron & Ringel, 2017 ), rankings can nowadays be found in an increasing number of sectors, at any level, from local to global. Nation-states, businesses, cities, restaurants, and artists are among the many entities whose performances are regularly compared, quantified and rank-ordered. Not only are rankings becoming more common and in some cases quite salient, but they are also becoming more diverse and elaborate, and some of them notably resource-intensive to produce and sustain. At the same time, keeping track of the latest rankings results, and not least of the requirements for participation and data submission, has become ever more demanding. And in some domains, rankings have become ubiquitous to such an extent that they are now an object of a sustained interest of both key stakeholders and scholars studying it. Higher education is one of those domains.

Rankings of higher education institutions, whether we refer to them as college or university rankings, have been around for more than a century (Hammarfelt et al., 2017 ; Myers & Robe, 2009 ). But despite this long history, it was not before the 1980s and the first editions of college rankings published by US News & World Report that rankings attained the status of a phenomenon beyond narrow policy and otherwise specialized circles, in the United States at least (Espeland & Sauder, 2007 ). In a somewhat similar fashion, the first so-called global rankings of universities in the early 2000s would prompt worldwide interest, effectively making them a hotly debated topic across policy, administrative, and scholarly circles (Brankovic et al., 2022 ; O’Connell, 2013 ; Paradeise & Filliatreau, 2016 ). About a decade later, Sarah Amsler would observe:

We are drowning in words about rankings: how they emerged, how to design them, how to theorize them, their classifications and comparisons, the extent of their effectiveness for different purposes, why to critique them, why to defend them, improvements that will make them methodologically robust, etc. Writing about rankings has become a global business. What more can possibly be said? (Amsler, 2014 , p. 155, emphasis added)

One could have expected at this point that the scholarly conversation on rankings was about to reach saturation, leading to a decline in interest and overall attention. However, this is not what happened. If “writing about rankings,” as Amsler put it, was a global business a decade ago, it seems that the business only grew in the years that followed. Notably, throughout the second decade of this century, rankings further evolved, became more complex to produce and maintain, but arguably also more of a business-as-usual in everyday higher education affairs. By this point, the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU, also commonly known as the Shanghai ranking), the rankings produced by Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) and Times Higher Education (THE), and later also U-Multirank, became common references in higher education management, policy, and research. And although rankings as such have stopped being inherently newsworthy for many people in and around higher education, they have continued to make international and national news world over (Barats, 2020 ; Shahjahan et al., 2022 ). Scholars have kept writing about them, with even greater intensity it seems. Footnote 1

A striking characteristic of much of the literature on rankings in higher education—and especially when it comes to the works published in journals specializing in education, higher education, and science studies—is that it largely takes rankings for granted. The questions such as why and how rankings have become so pervasive are rarely addressed as an empirical puzzle. Rather, regardless of their attitude toward academic performance evaluation (critical, neutral, or affirmative), scholars would typically assume that rankings have origins and drivers beyond higher education, and are loosely connected, sometimes causally even, with globalization, managerialism, neoliberalism, recent geopolitical, and other broader trends (e.g., Collins & Park, 2015 ; Hazelkorn, 2016 ; Locke, 2014 ; Lynch, 2014 ; Peters, 2019 ). Footnote 2 This writing is often permeated with a sense that rankings were and still are, one way or the other, inevitable. It is further notable that a great deal of research is more or less explicitly evaluative and normative: university rankings would be judged—and often deemed inadequate—for their fitness for purpose, soundness of their methodologies, transparency, or their performative and other kind of effects on higher education (e.g., see recent volumes edited by Hazelkorn & Mihut, 2021b ; Stack, 2021 ; Welch & Li, 2021 ). Without any doubt, the research on rankings to date has greatly contributed to a better understanding of the dynamics surrounding rankings in higher education. And yet, we do not seem to be any closer to explaining their ubiquity—and to some extent also their legitimacy—than we were a decade ago.

To address this problem, we propose seeing the proliferation and normalization of rankings in higher education as part of the larger process of institutionalization (Colyvas & Jonsson, 2011 ). The very claim that rankings are becoming institutionalized, however unproblematic it may seem, requires qualification. Broadly speaking, and for our purposes here, we see institutionalization as a process in which a phenomenon, such as rankings, becomes progressively embedded in a community’s belief systems, norms, and practices (Berger & Luckmann, 1966 ; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983 ; Jepperson, 1991 ; Zucker, 1977 ). Its existence becomes taken for granted and as such rarely questioned by members of the community. In suggesting that this could be the case with rankings in higher education, we do not mean to say that rankings are not criticized or alternatives to existing rankings are not discussed. What we mean is that even for critical scholars a world without them may seem too far off. The widespread sentiment shared by proponents and opponents that rankings are inevitable, in fact, attests that this indeed may be the case. Despite the ongoing criticism addressed at specific rankings and their producers, for most actors in higher education the idea that higher education institutions operate within hierarchies, based on some notion of quality or performance, seems to be a legitimate one. In view of such a widespread consensus, it does not surprise that a rank given to a university often assumes the status of a “blunt fact”—which universities can do little to ignore (Sauder & Espeland, 2009 , p. 77).

Observing rankings through the lens of institutionalization, however, does not mean that the future developments can only take one direction, that is, the one of further or deeper institutionalization. For institutionalization is, as a rule, an uneven, patchy process, of varying depth, and not least also a reversible one (Oliver, 1992 ). Therefore, applying the lens of institutionalization allows us to open up a space for asking questions about the nature of this process. Doing this would require us to go beyond the issues of rankings’ legitimacy as such and their alignment with higher educations’ historical tendency—in some contexts at least—to vertically differentiate between higher education institutions based on some notion of quality, performance, or prestige (Brankovic, 2018 ; Clark, 1983 ). Institutionalization, in particular in a strong form, would arguably mean that rankings themselves become an institution and are as such integrated into the modes of reproduction, and not only “contingent on alignment with existing cultural and cognitive frames” (Colyvas & Jonsson, 2011 , p. 45). Neither taken-for-grantedness nor legitimacy are sufficient conditions for considering rankings as permanent features of higher education. For this to be the case, the “chronic” (re)production, legitimation, and maintenance of rankings would need to be also embedded in higher education’s frames, rules, and routines (Colyvas & Jonsson, 2011 ; Jepperson, 1991 ). Footnote 3 By implication, for the institutionalization of rankings to be considered a process unfolding on a global scale , this embeddedness would need to be evidenced not only in some parts of the world, but progressively all over the world. Whether this is indeed happening, and not least the degree to which it may be happening, is an empirical question whose addressing requires moving beyond the usual accounts on how and why rankings have become pervasive in higher education.

In examining this process, we start with a simple point: in order to question the institutionalization of rankings as a social phenomenon, we need to take seriously both the broader social, political, and historical conditions, and the conditions specific to higher education, and treat them as objects of empirical investigation. From this follows that we need to observe not only the broad institutional developments, but also how these shape and are shaped by the dynamics pertaining to the social-organizational and even individual levels of the social order (Jepperson & Meyer, 2011 ); and relatedly, not only how rankings diffuse, but also how they “stick” (Colyvas & Jonsson, 2011 , p. 30). This requires turning our gaze to the ensemble that possibly fosters the institutionalization of rankings: not only the organizations producing them, but also policy makers, universities and their administrators, publishers, researchers, consultants, and many others (as illustrated or empirically shown in, e.g., Hallett & Ventresca, 2006 ; Scott et al., 2000 ; Zilber, 2002 ), some of whom are possibly even unaware of their contribution. For us scholars who study rankings, addressing this question, by definition, also implies turning the analytical gaze towards ourselves, given that we too—like those rankings we write (and rant) about—are invested in knowledge claims about higher education. Last but not least, it means being reflexive about our position(s) as participants in higher education, who are usually employed at the institutions evaluated by the very rankings we seek to study objectively. This is one way the challenges arising in researching university rankings could differ from those arising in researching, for example, rankings of prisons or hospitals: “we” are both observers and parties concerned.

Once we recalibrate our lens for capturing the material and discursive conditions that undergird rankings, and not least the spatial and temporal ones, it becomes apparent that in front of us lie not some mysterious and immovable forces, but very real people, processes, and structures. It is when we start observing interactions, routines, practices, and actors, and not least how they evolve, that we are in a position to see rankings—and organizational status hierarchies (re)produced through them—as an artifice whose institutionalization is not a linear path dependency, but a practical accomplishment that we still know too little about. The question then becomes how rankings proliferate, persist, and become embedded, which urges us to take a more comprehensive view on the multiplicity of contributing and potentially entangled factors. As we start treating the ubiquity and legitimacy of rankings as empirical questions, grand narratives such as globalization and neoliberalism—while surely important macro-conditions—become in and of themselves unsatisfactory as standalone explanations.

Continuities, interdependencies, and engagement

The special issue The Institutionalization of University Rankings: Continuities, Interdependencies, Engagement aims to broaden the burgeoning scholarly conversation on rankings in higher education, specifically by shifting the attention towards empirical questions about the underlying conditions of their ubiquity, both in higher education and higher education research. This special issue brings together scholars of diverse backgrounds who have different interests with regards to rankings and higher education. In the spirit of the journal, they draw from a range of epistemic traditions, including sociology, history, organization and management studies, critical theory, and of course higher education and science studies. The seven articles, each from a different angle and with a different theoretical or empirical foci, aim to contribute to a better understanding of what university rankings are, where they come from, the way they operate, and how they have become increasingly entangled in the processes and structures of higher education and science.

In the remainder of this section we organize the contributions along three themes: continuities, interdependencies, and engagement. Specifically, these themes draw attention to (a) how rankings, their relevance, and the purposes and meaning(s) assigned to them evolve over time ( continuities ); (b) what relationships and structural entanglements emerge around and keep rankings going ( interdependencies ); and (c) how the institutionalization of rankings is fostered through the interaction with different audiences ( engagement ). These are not discrete categories and are better viewed as strategies of evidencing the multiplicity of conditions that enable the sustenance and proliferation of rankings in higher education. Under each theme, we discuss a selection of articles included in the special issue, whereby we highlight how each connects to continuity, interdependencies, or engagement. Notably, and as we show later on, none of the articles is limited to one theme, as they are all stand-alone works that make their own contributions to the study of rankings, which also go beyond this special issue. We proceed by discussing each theme in turn.

Continuities

There is a tendency in the literature to narrate the history of college and university rankings as a succession of events, usually centering on the publication of various “successful” rankings and their respective methodologies (e.g., Hazelkorn & Mihut, 2021a ; Myers & Robe, 2009 ; Usher, 2017 ). Paired with the enduring interest in the effects, this tendency has led to foregrounding certain rankings, in particular the more recent ones, at the expense of the context in which present and past rankings were produced and the circumstances that enabled (or impeded) their impacts. However, left unchecked, this tendency carries with itself a risk of promoting narratives of history that are overly deterministic and too simplified. Furthermore, taking specific historical events and neatly delineated eras for granted, instead of questioning them, could easily magnify change and novelty at the expense of continuity and more gradual transitions. After all, questioning the institutionalization of rankings requires a better understanding of not only why some rankings succeed or perish, in the sense given above, but also appreciating the historical contingencies in their evolution.

A striking example of a continuous and gradually intensifying interest in rankings stretching over many decades is found in the history of rankings in the United States. In their contribution, titled “The emergence of university rankings: a historical-sociological account,” Wilbers and Brankovic ( 2021 ) take a closer look at this process, with the aim to better understand the circumstances under which ranking universities based on repeated observations became a widely accepted method of discussing quality and excellence. The authors argue that the increasing attention to rankings during the 1960s and 1970s—across administrative, policy, and scientific circles—was possible in large part due to a shift in the understanding of what it meant to perform as a university. The crux of this understanding, which found a fitting expression in the zero-sum ranking table, is that the performance of one organization can be determined only in relation to the performances of other organizations. By casting light on the often-neglected developments during the 1960s and 1970s, the article also contributes to a fuller understanding of the historical context leading to the 1980s—the decade in which US News & World Report would emerge on the college ranking scene.

China is a somewhat contrasting case. Here, too, we see a prolonged interest in rankings, but pursued chiefly by the country’s central government. In their article “The politics of university rankings in China,” Ahlers and Christmann-Budian ( 2023 ) argue that in the case of China, university rankings are an organic part of the state’s top-down science, technology, and innovation policy structure, rather than a tool primarily for international comparison, as it is sometimes portrayed. Since the first national ranking published by the ministry for science and technology in the 1980s, via the first international ranking by Shanghai Jiao Tong University in the early 2000s, until today, the discourse on rankings in China has been largely shaped by national concerns. Western rankings and other performance indicators would be increasingly challenged, also on the grounds that they are not sufficiently relevant for the Chinese context. Ahlers and Christmann-Budian conclude that, unlike most countries in which international rankings tend to exert a more direct influence on universities, in China, this effect has always been thickly mediated by its government’s strategic interest in higher education and science—which long precedes the first global rankings.

While both articles speak to continuities, they are also revealing of the interdependencies between those credited with producing a ranking and other parties contributing to it, including their supporters, sponsors, and critics, thus a more nuanced picture of what makes a ranking—and its effect(s)—possible and indeed likely. Clearly, and as the two cases also illustrate, the constellation of actors and the nature of their involvement vary across countries as well as over time. This, however, complicates the usual understanding of agency when it comes to university rankings, in which the role of the so-called “rankers” tends to be over-dramatized. Yet, as we shall argue in the following section, considering agency as distributed rather than unitary has potentially much to offer to the study of rankings.

Interdependencies

The best-known university rankings nowadays are complex undertakings. To produce a ranking, major ranking organizations rely on continuous participation of multiple third parties, including universities, their administrative staff, and individual faculty members. Universities supplying data or academics completing reputation surveys are examples of this participation. The complexity becomes evident also when we observe that rankers are embedded in an increasingly dense network of organizations that collect, supply, and compile data for various rankings (Chen & Chan, 2021 ; Krüger, 2020 ; Williamson, 2021 ). Finally, the complexity is evident from the fact that some rankers are engaged in a host of additional and supplementary activities: for instance, they organize events, sell consulting services to universities and governments, and actively engage with various other audiences. However, research tends to treat rankings as almost exclusively a doing of the organizations owning major rankings, such as THE and QS, whereby the role and agency of other actors, such as that of higher education institutions, are often neglected (as also recently argued by Locke, 2021 ). Understanding how rankings become (or do not become) institutionalized requires broadening this scope by, among others, paying close notice to distributed agencies and therefore interdependencies between rankers and other actors in higher education.

In their study “The power in managing numbers: changing interdependencies and the rise of ranking expertise,” Chun and Sauder ( 2022 ) investigate universities’ ranking management departments in South Korea. The authors note that these units have become increasingly influential because they have turned the management of rankings within and across universities into a valuable new form of expertise. This new kind of expertise, the authors argue, has reshaped key interdependencies both within universities and between universities and external constituents, and has further led to a change in work routines and new organizational practices. Drawing on the insights from their study, Chun and Sauder challenge the usual line of argument in which rankings are credited with generating competition by calling attention to how they also lead to new forms of cooperation. They thus conclude:

A key recipe for successful rankings is to incorporate multiple actors to collectively build expertise in the management of rankings. Rankings maintain and extend their influence over higher education through proliferating relational ties and interdependencies among universities, rankings, and other external parties. (Chun & Sauder, 2022 , p. 17).

Interdependencies often arise in relation to resources, which are especially important to consider in the case of commercially driven ranking organizations. In addition to playing the role of impartial arbiters in creating rankings of higher education institutions, these organizations also act as businesses who sell services to those same institutions, including advertising and consulting. In his contribution to the special issue, titled “Does conflict of interest distort global university rankings?” Igor Chirikov ( 2022 ) tackles the relationship between these two roles. He sets out to empirically determine whether a conflict of interest leads to privileging certain universities over others by examining the effect of the universities in Russia contracting with QS on ranking outcomes. The findings suggest that, regardless of changes in the institutional characteristics, the universities with frequent QS-related contracts did improve their respective ranks more than their competitors. Similar to the recent study by Jacqmin ( 2021 ), in which the author analyzes the relationship between advertising on THE website and THE rankings, Chirikov’s work urges us to pay closer attention to the nature of linkages and (inter)dependencies that emerge between ranking organizations, higher education institutions, and other parties directly and indirectly involved in sustaining rankings.

As both Chun and Sauder’s and Chirikov’s studies demonstrate, rankings are made possible through an ongoing collaboration and cooperation between different parties, whose interests and orientations are variously aligned. In his contribution to the special issue, “How university rankings are made through globally coordinated action: a transnational institutional ethnography in the sociology of quantification,” Gary Barron ( 2022 ) is specifically concerned with the distributed nature of the production of rankings. He conceptualizes data and infrastructure work across sites as globally coordinated action, whereby individual members of academic and administrative staff become a part of that infrastructure, as they work with the data on an ongoing basis across countless physical sites. Barron notes that the contribution of higher education institutions to the production of rankings is not uniform; rather, it assumes different modalities, which center on individuals and organizational units doing routine work, often without having a full grasp of the overarching network of relationships of which they make a vital part.

Studying interdependencies, and not least how they evolve, holds promise for improving our understanding not only of how rankings produce new relationships in higher education, but also how they strengthen and transform existing ones. The importance of relationships between actors has also been recognized in the recent work by Engwall, Edlund, and Wedlin ( 2023 ) on the spread of evaluations, including rankings, in academia, and the work by Brankovic, Ringel, and Werron ( 2022 ) on the role of boundary work in the legitimation of university rankings. Moreover, one can easily see the relevance of studying interactional and relational dynamics for advancing our understanding of continuities vis-à-vis rankings, and history more generally. And, as we shall see in the following section, interdependencies are not only structural but also very much discursive and even actively initiated and sustained by rankers and their audiences.

One important aspect of rankings is the fact that they are a public comparison of performances (Brankovic et al., 2018 ). Even though this has been highlighted in some of the classic works on the subject (e.g., Espeland & Sauder, 2007 ), research largely takes the public character of rankings for granted. Hence, what precisely follows from it is not well understood. Upon closer observation, we note that, as a function of their public character, rankings engage with various expert and non-expert audiences for which they serve—or are believed to serve—different needs. As different as these audiences are, what they have in common is that they need, or are perceived as being in need of, orientation, legitimation, or status signals (Esposito & Stark, 2019 ; Hamann & Schmidt-Wellenburg, 2020 ). Yet how rankings invoke, engage, and influence their audiences, and how this engagement contributes to or challenges their institutionalization, is something we have very little insight into.

Reaching out to and catering for various audiences has always marked rankers’ efforts to secure attention and legitimacy. The growing importance of social media in public life has made it an attractive space for various organizations to, on the one hand, promote their causes, services, or products and, on the other, foster engagement across diverse audiences. In their article “The ‘LOOMING DISASTER’ for higher education: how commercial rankers use social media to amplify and foster affect,” Riyad Shahjahan, Adam Grimm, and Ryan Allen ( 2021 ) critically examine the social media activities of THE and QS. Analyzing THE’s Twitter feed and QS’ Facebook page, the authors show how these organizations use storytelling to frame and sell their products and services. Both organizations, the authors find, use social media platforms to mobilize collective emotional states and actions, in particular precarity that comes with feelings of uncertainty, insecurity, anxiety, and/or competition. The article highlights social media’s uniqueness as affective infrastructure, given its cost-effectiveness, ease of consumption, the broad and quick outreach it allows, and not least its interactive nature.

In their contribution “The discursive resilience of university rankings,” Hamann and Ringel ( 2023 ) survey the discursive environment of rankings and distinguish two modes of critique: a rather fundamental mode that draws attention to the negative effects of rankings, and a more technical mode that is concerned with their methodological shortcomings. Rankers either counter this criticism and offer alternative narratives, or confidently highlight rankings’ scientific proficiency and stress that rankings are always to be developed and improved further. Crucially, the confident responses to criticism also include attempts to engage critics, inviting them into a productive conversation about how rankings could be developed further. The ensuing and seemingly never-ending conversation between rankers and critics about how to arrive at more rigorous assessments helps bestow university rankings with what the authors refer to as “discursive resilience.” The contribution emphasizes not only that critique is an important element of the institutionalization of university rankings, but, in a general sense, also sensitizes for discursive dynamics that emerge organically and therefore unfold “behind the backs” of rankers and their critics..

Both contributions bring to the fore the importance of the digital sphere as a site of engagement and interaction, in particular social media, which have so far not attracted much interest from research on rankings (for some exceptions, see Lim, 2021 ; Stack, 2016 ). Rankers seem to take their social media and other types of online engagement quite seriously, which urges us to look beyond their ranking tables if we are to grasp a fuller picture of how a particular effect is produced. The recent study by Hansen and Van den Bossche ( 2022 ), which tracks rhetorical change in the Times Higher Education’s rankings coverage, vividly captures how subtle yet potent this effect can be. Altogether, these insights indicate that dynamics in the public domain—whether digital, in print or in person—are worth observing when asking questions about how rankers invoke, engage, and influence their audiences.

What more can possibly be said?

The overarching takeaway of the special issue is that the institutionalization of rankings is driven not only by macro-societal trends, but also by the ongoing engagement in multiple arenas and spheres between different parties, both inside and outside of higher education . How this plays out, however, has not been made an object of sustained empirical or theoretical interest in higher education studies, in particular not on a par with the amount of interest in describing and interpreting the effects or methodologies of rankings. We therefore wish to reiterate that, if we are to better understand how rankings in higher education become a taken-for-granted social fact, as well as how their taken-for-grantedness is challenged, greater theoretical and empirical attention is needed to the dynamics pertaining to the social-organizational and individual levels of the social order. We propose that this attention is directed to the questions that concern continuities, interdependencies, and audience engagement.

The collection of articles included in the issue is a step in the direction of what we see as an important theoretical and empirical challenge. As we noted, the three themes are not mutually exclusive, nor do the contributions to the special issue shed light only on one at a time. Rather, they closely relate to each other and are very much intertwined. And so, as rankings evolve, they shape and reshape interdependencies between actors and take up expectations of different audiences. Continuity is, after all, another way of acknowledging at least some degree of path dependency at work. Rankings build resilience in part because their engagement of different audiences is ongoing and gradually normalized and in part because their production is the work of many diverse actors, who repeatedly contribute to the collective endeavor, from one ranking cycle to the next. These considerations merit further investigation. Ultimately, as with the study of institutionalization processes more generally, puzzling over the institutionalization of rankings equally invites us to consider the temporal and the spatial, the material and the discursive.

Echoing the calls made by some of the authors in the special issue, we believe that there is a great deal we can learn about rankings by systematically comparing continuities, interdependencies, and engagement in different parts of the world and at different levels. Comparative studies have so far advanced our understanding of a range of phenomena in higher education (Kosmützky & Nokkala, 2014 ; Kosmützky et al., 2020 ; Teichler, 2014 ). And they hold good promise for unraveling the antecedents and consequences of continuities, but also of discontinuities; interdependencies and the absence thereof; and, finally, engagement as well as disengagement. Furthermore, there is a lot to be learned about rankings in higher education by extending our scope and comparing them with the institutionalization of other devices of evaluation (Hamann et al., 2023 ). But comparative research need not be limited to higher education and can take into account rankings in other domains (for an illustration, see Brankovic et al., 2021 ). After all, we should not forget that rankings in higher education (and higher education as such, for that matter) are part of a larger societal field in which various quantitative indicators have come to wield significant influence in recent years (de Rijcke et al., 2016 ; Erkkilä & Piironen, 2018 ; Mennicken & Espeland, 2019 ; Pardo-Guerra, 2022 ). In view of this, empirically identified similarities and differences between rankings and other kinds of quantification-based comparisons—within and beyond higher education—could be fruitfully exploited for the purpose of furthering our understanding of rankings in higher education.

In closing, we hope that this special issue would deepen our collective appreciation of the complexity of rankings as a social phenomenon and inspire those working on the topic to consider some of the perspectives and insights herewith offered. We equally hope that this issue would stimulate us all to further question the taken-for-grantedness of rankings in higher education as well as in higher education research. Not because we believe that rankings are all bad or harmful (if this were indeed so, things would be, we suspect, far simpler), but because it is our task as scholars to question everything in society, including—and perhaps especially—our own assumptions and beliefs.

For example, a simple query of the publications indexed in the Scopus database shows that the number of publications containing “rankings” preceded by either “university” or “college” in their titles continued to grow in the years after 2014. The same can be observed for the frequency of collocation “university rankings” in the Google Books corpus.

In his book, Grading the College , Gelber ( 2020 ) makes a similar observation about evaluation of teaching and learning in (US) higher education more generally.

As, for comparison, explicit considerations of “quality” have become progressively embedded in a host of organizational processes and practices in higher education (Elken & Stensaker, 2018 ).

Ahlers, A. L., & Christmann-Budian, S. (2023). The politics of university rankings in China. Higher Education . https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10734-023-01014-y

Amsler, S. S. (2014). University ranking: A dialogue on turning towards alternatives. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics, 13 (2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.3354/esep00136

Article Google Scholar

Barats, C. (2020). Dissemination of international rankings: Characteristics of the media coverage of the Shanghai Ranking in the French press. Palgrave Communications, 6 (1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0440-5

Barron, G. R. S. (2022). How university rankings are made through globally coordinated action: A transnational institutional ethnography in the sociology of quantification. Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00903-y

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge . Anchor Books.

Brankovic, J. (2018). The status games they play: Unpacking the dynamics of organisational status competition in higher education. Higher Education, 75 (4), 695–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0169-2

Brankovic, J., Ringel, L., & Werron, T. (2018). How rankings produce competition: The case of global university rankings. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 47 (4), 270–288. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2018-0118

Brankovic, J., Ringel, L., & Werron, T. (2021). Theorizing University Rankings by Comparison: Systematic and historical analogies with arts and sports. In E. Hazelkorn & G. Mihut (Eds.), Research Handbook on University Rankings: History, Methodology, Influence and Impact (pp. 67–79). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788974981.00013

Brankovic, J., Ringel, L., & Werron, T. (2022). Spreading the gospel: Legitimating university rankings as boundary work. Research Evaluation , rvac035. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvac035

Chen, G., & Chan, L. (2021). University Rankings and Governance by Metrics and Algorithms. In E. Hazelkorn & G. Mihut (Eds.), Research Handbook on University Rankings: Theory, Methodology, Influence and Impact . Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4730593

Chirikov, I. (2022). Does conflict of interest distort global university rankings? Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00942-5

Chun, H., & Sauder, M. (2022). The power in managing numbers: Changing interdependencies and the rise of ranking expertise. Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00823-x

Clark, B. R. (1983). The Higher Education System: Academic Organization in Cross-National Perspective. University of California Press.

Collins, F. L., & Park, G.-S. (2015). Ranking and the multiplication of reputation: Reflections from the frontier of globalizing higher education. Higher Education, 72 (1), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9941-3

Colyvas, J. A., & Jonsson, S. (2011). Ubiquity and Legitimacy: Disentangling Diffusion and Institutionalization. Sociological Theory, 29 (1), 27–53.

de Rijcke, S., Wallenburg, I., Wouters, P., & Bal, R. (2016). Comparing Comparisons. On Rankings and Accounting in Hospitals and Universities. In J. Deville, M. Guggenheim, & Z. Hrdličková (Eds.), Practising Comparison: Logics, Relations, Collaborations (pp. 251–280). Mattering Press.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review, 48 (2), 147–160.

Elken, M., & Stensaker, B. (2018). Conceptualising ‘quality work’ in higher education. Quality in Higher Education, 24 (3), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2018.1554782

Engwall, L., Edlund, P., & Wedlin, L. (2023). Who is to blame? Evaluations in academia spreading through relationships among multiple actor types. Social Science Information . https://doi.org/10.1177/05390184221146476

Erkkilä, T., & Piironen, O. (2018). Rankings and Global Knowledge Governance: Higher Education . Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68941-8

Book Google Scholar

Espeland, W. N., & Sauder, M. (2007). Rankings and Reactivity: How Public Measures Recreate Social Worlds. American Journal of Sociology, 113 (1), 1–40.

Esposito, E., & Stark, D. (2019). What’s Observed in a Rating? Rankings as Orientation in the Face of Uncertainty. Theory, Culture and Society, 36 (4), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276419826276

Gelber, S. M. (2020). Grading the College: A History of Evaluating Teaching and Learning. JHU Press. https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/grading-college

Hallett, T., & Ventresca, M. J. (2006). Inhabited Institutions: Social Interactions and Organizational Forms in Gouldner’s Patterns of Industrial Bureaucracy. Theory and Society, 35 (2), 213–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-006-9003-z

Hamann, J., & Schmidt-Wellenburg, C. (2020). The double function of rankings: Consecration and dispositif in transnational academic fields. In C. Schmidt-Wellenburg & S. Bernhard (Eds.), Charting Transnational Fields: Methodology for a Political Sociology of Knowledge . Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429274947

Hamann, J., Blome, F., & Kosmützky, A. (2023). Devices of evaluation: Institutionalization and impact – Introduction to the special issue. Research Evaluation .

Hamann, J., & Ringel, L. (2023). The discursive resilience of university rankings. Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00990-x

Hammarfelt, B., de Rijcke, S., & Wouters, P. (2017). From Eminent Men to Excellent Universities: University Rankings as Calculative Devices. Minerva, 55 (4), 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-017-9329-x

Hansen, M., & Van den Bossche, A. (2022). From newspaper supplement to data company: Tracking rhetorical change in the Times Higher Education’s rankings coverage. Poetics , 92 , 101637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101637

Hazelkorn, E. (2016). Introduction: The geopolitics of rankings. In E. Hazelkorn (Ed.), Global Rankings and the Geopolitics of Higher Education: Understanding the influence and impact of rankings on higher education, policy and society (pp. 1–20). Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hazelkorn, E., & Mihut, G. (Eds.). (2021). Research Handbook on University Rankings: Theory, Methodology . Edward Elgar Publishing.

Google Scholar

Hazelkorn, E., & Mihut, G. (2021). Introduction: Putting rankings in context - looking back, looking forward. In E. Hazelkorn & G. Mihut (Eds.), Research Handbook on University Rankings: Theory, Methodology, Influence and Impact (pp. 1–17). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Jacqmin, J. (2021). Do ads influence rankings? Evidence from the higher education sector. Education Economics, 29 (5), 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2021.1918642

Jepperson, R. L. (1991). Institutions, institutional effects, and institutionalization. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis (pp. 143–163). University of Chicago Press.

Jepperson, R. L., & Meyer, J. W. (2011). Multiple Levels of Analysis and the Limitations of Methodological Individualisms. Sociological Theory, 29 (1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01387.x

Kosmützky, A., & Nokkala, T. (2014). Challenges and trends in comparative higher education: An editorial. Higher Education, 67 (4), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9693-x

Kosmützky, A., Nokkala, T., & Diogo, S. (2020). Between context and comparability: Exploring new solutions for a familiar methodological challenge in qualitative comparative research. Higher Education Quarterly, 74 (2), 176–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12255

Krüger, A. K. (2020). Quantification 2.0? Bibliometric Infrastructures in Academic Evaluation. Politics and Governance, 8 (2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.2575

Lim, M. A. (2021). The business of university rankings: The case of Times Higher Education. In E. Hazelkorn & G. Mihut (Eds.), Research Handbook on University Rankings: Theory, Methodology, Influence and Impact (pp. 444–453). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4730593

Locke, W. (2014). The Intensification of Rankings Logic in an Increasingly Marketised Higher Education Environment. European Journal of Education, 49 (1), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12060

Locke, W. (2021). Researching and understanding the influence of rankings on higher education institutions: Logics, methodologies and conceptualisations. In E. Hazelkorn & G. Mihut (Eds.), Research Handbook on University Rankings: Theory, Methodology, Influence and Impact (pp. 80–92). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lynch, K. (2014). New managerialism, neoliberalism and ranking. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics, 13 (2), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.3354/esep00137

Mennicken, A., & Espeland, W. N. (2019). What’s New with Numbers? Sociological Approaches to the Study of Quantification. Annual Review of Sociology, 45 (1), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041343

Myers, L., & Robe, J. (2009). College Rankings: History, Criticism and Reform . Center for College Affordability and Productivity. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED536277

O’ Connell, C. (2013). Research Discourses Surrounding Global University Rankings. Exploring the Relationship with Policy and Practice Recommendations. Higher Education, 65 (6), 709–723.

Oliver, C. (1992). The Antecedents of Deinstitutionalization. Organization Studies, 13 (4), 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069201300403

Paradeise, C., & Filliatreau, G. (2016). The Emergent Action Field of Metrics: From rankings to altmetrics. In E. Popp Berman & C. Paradeise (Eds.), The University Under Pressure (Vol. 46, pp. 87–128). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Pardo-Guerra, J. P. (2022). The Quantified Scholar: How Research Evaluations Transformed the British Social Sciences . Columbia University Press.

Peters, M. A. (2019). Global university rankings: Metrics, performance, governance. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 51 (1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2017.1381472

Sauder, M., & Espeland, W. N. (2009). The Discipline of Rankings: Tight Coupling and Organizational Change. American Sociological Review, 74 (1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400104

Scott, W. R., Ruef, M., Mendel, P. J., & Caronna, C. A. (2000). Institutional Change and Healthcare Organizations: From Professional Dominance to Managed Care. University of Chicago Press.

Shahjahan, R. A., Grimm, A., & Allen, R. M. (2021). The “LOOMING DISASTER” for higher education: How commercial rankers use social media to amplify and foster affect. Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00762-z

Shahjahan, R. A., Bylsma, P. E., & Singai, C. (2022). Global university rankings as ‘sticky’ objects and ‘refrains’: Affect and mediatisation in India. Comparative Education, 58 (2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2021.1935880

Stack, M. (2016). Global University Rankings and the Mediatization of Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Stack, M. (Ed.). (2021). Global University Rankings and the Politics of Knowledge. University of Toronto Press. https://utorontopress.com/us/global-university-rankings-and-the-politics-of-knowledge-4

Teichler, U. (2014). Opportunities and problems of comparative higher education research: The daily life of research. Higher Education, 67 (4), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9682-0

Usher, A. (2017). A short global history of rankings. In E. Hazelkorn (Ed.), Global Rankings and the Geopolitics of Higher Education: Understanding the influence and impact of rankings on higher education, policy and society (pp. 23–53). Routledge.

Welch, A., & Li, J. (Eds.). (2021). Measuring up in higher education: How university rankings and league tables are re-shaping knowledge production in the global era . Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7921-9

Werron, T., & Ringel, L. (2017). Rankings in a comparative perspective. Conceptual remarks. In S. Lessenich (Ed.), Geschlossene Gesellschaften. Verhandlungen des 38. Kongresses der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie in Bamberg 2016 (pp. 1–10). DGS.

Wilbers, S., & Brankovic, J. (2021). The emergence of university rankings: A historical-sociological account. Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00776-7

Williamson, B. (2021). Making markets through digital platforms: Pearson, edu-business, and the (e)valuation of higher education. Critical Studies in Education, 62 (1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2020.1737556

Zilber, T. B. (2002). Institutionalization as an Interplay Between Actions, Meanings, and Actors: The Case of a Rape Crisis Center in Israel. Academy of Management Journal, 45 (1), 234–254. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069294

Zucker, L. G. (1977). The Role of Institutionalization in Cultural Persistence. American Sociological Review, 42 (5), 726–743. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094862

Download references

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the authors who have contributed to this special issue. None of it would have been possible without their ideas, work, and patience. The issue would, of course, have neither been possible without all the work put in it by the reviewers, and the support and guidance of the Editors-in-Chief of Higher Education throughout the process. All errors are our own.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Sociology, Bielefeld University, Universitätsstraße 25, 33615, Bielefeld, Germany

Jelena Brankovic & Leopold Ringel

Department of Educational Sciences, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Unter den Linden 6, 10099, Berlin, Germany

Julian Hamann

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jelena Brankovic .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Brankovic, J., Hamann, J. & Ringel, L. The institutionalization of rankings in higher education: continuities, interdependencies, engagement. High Educ 86 , 719–731 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01018-8

Download citation

Accepted : 23 February 2023

Published : 05 April 2023

Issue Date : October 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01018-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Higher education

- Institutionalization

- Organizations

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Studies in Higher Education - Impact Score, Ranking, SJR, h-index, Citescore, Rating, Publisher, ISSN, and Other Important Details

Published By: Routledge

Abbreviation: Stud. High. Educ.

Impact Score The impact Score or journal impact score (JIS) is equivalent to Impact Factor. The impact factor (IF) or journal impact factor (JIF) of an academic journal is a scientometric index calculated by Clarivate that reflects the yearly mean number of citations of articles published in the last two years in a given journal, as indexed by Clarivate's Web of Science. On the other hand, Impact Score is based on Scopus data.

Important details, about studies in higher education.

Studies in Higher Education is a journal published by Routledge . This journal covers the area[s] related to Education, etc . The coverage history of this journal is as follows: 1976-2022. The rank of this journal is 1695 . This journal's impact score, h-index, and SJR are 5.20, 120, and 1.716, respectively. The ISSN of this journal is/are as follows: 03075079, 1470174X . The best quartile of Studies in Higher Education is Q1 . This journal has received a total of 3142 citations during the last three years (Preceding 2022).

Studies in Higher Education Impact Score 2022-2023

The impact score (IS), also denoted as the Journal impact score (JIS), of an academic journal is a measure of the yearly average number of citations to recent articles published in that journal. It is based on Scopus data.

Prediction of Studies in Higher Education Impact Score 2023

Impact Score 2022 of Studies in Higher Education is 5.20 . If a similar upward trend continues, IS may increase in 2023 as well.

Impact Score Graph

Check below the impact score trends of studies in higher education. this is based on scopus data., studies in higher education h-index.

The h-index of Studies in Higher Education is 120 . By definition of the h-index, this journal has at least 120 published articles with more than 120 citations.

What is h-index?

The h-index (also known as the Hirsch index or Hirsh index) is a scientometric parameter used to evaluate the scientific impact of the publications and journals. It is defined as the maximum value of h such that the given Journal has published at least h papers and each has at least h citations.

Studies in Higher Education ISSN

The International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) of Studies in Higher Education is/are as follows: 03075079, 1470174X .

The ISSN is a unique 8-digit identifier for a specific publication like Magazine or Journal. The ISSN is used in the postal system and in the publishing world to identify the articles that are published in journals, magazines, newsletters, etc. This is the number assigned to your article by the publisher, and it is the one you will use to reference your article within the library catalogues.

ISSN code (also called as "ISSN structure" or "ISSN syntax") can be expressed as follows: NNNN-NNNC Here, N is in the set {0,1,2,3...,9}, a digit character, and C is in {0,1,2,3,...,9,X}

Studies in Higher Education Ranking and SCImago Journal Rank (SJR)

SCImago Journal Rank is an indicator, which measures the scientific influence of journals. It considers the number of citations received by a journal and the importance of the journals from where these citations come.

Studies in Higher Education Publisher

The publisher of Studies in Higher Education is Routledge . The publishing house of this journal is located in the United Kingdom . Its coverage history is as follows: 1976-2022 .

Call For Papers (CFPs)

Please check the official website of this journal to find out the complete details and Call For Papers (CFPs).

Abbreviation

The International Organization for Standardization 4 (ISO 4) abbreviation of Studies in Higher Education is Stud. High. Educ. . ISO 4 is an international standard which defines a uniform and consistent system for the abbreviation of serial publication titles, which are published regularly. The primary use of ISO 4 is to abbreviate or shorten the names of scientific journals using the technique of List of Title Word Abbreviations (LTWA).

As ISO 4 is an international standard, the abbreviation ('Stud. High. Educ.') can be used for citing, indexing, abstraction, and referencing purposes.

How to publish in Studies in Higher Education

If your area of research or discipline is related to Education, etc. , please check the journal's official website to understand the complete publication process.

Acceptance Rate

- Interest/demand of researchers/scientists for publishing in a specific journal/conference.

- The complexity of the peer review process and timeline.

- Time taken from draft submission to final publication.

- Number of submissions received and acceptance slots

- And Many More.

The simplest way to find out the acceptance rate or rejection rate of a Journal/Conference is to check with the journal's/conference's editorial team through emails or through the official website.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the impact score of studies in higher education.

The latest impact score of Studies in Higher Education is 5.20. It is computed in the year 2023.

What is the h-index of Studies in Higher Education?

The latest h-index of Studies in Higher Education is 120. It is evaluated in the year 2023.

What is the SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) of Studies in Higher Education?

The latest SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) of Studies in Higher Education is 1.716. It is calculated in the year 2023.

What is the ranking of Studies in Higher Education?

The latest ranking of Studies in Higher Education is 1695. This ranking is among 27955 Journals, Conferences, and Book Series. It is computed in the year 2023.

Who is the publisher of Studies in Higher Education?

Studies in Higher Education is published by Routledge. The publication country of this journal is United Kingdom.

What is the abbreviation of Studies in Higher Education?

This standard abbreviation of Studies in Higher Education is Stud. High. Educ..

Is "Studies in Higher Education" a Journal, Conference or Book Series?

Studies in Higher Education is a journal published by Routledge.

What is the scope of Studies in Higher Education?

For detailed scope of Studies in Higher Education, check the official website of this journal.

What is the ISSN of Studies in Higher Education?

The International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) of Studies in Higher Education is/are as follows: 03075079, 1470174X.

What is the best quartile for Studies in Higher Education?

The best quartile for Studies in Higher Education is Q1.

What is the coverage history of Studies in Higher Education?

The coverage history of Studies in Higher Education is as follows 1976-2022.

Credits and Sources

- Scimago Journal & Country Rank (SJR), https://www.scimagojr.com/

- Journal Impact Factor, https://clarivate.com/

- Issn.org, https://www.issn.org/

- Scopus, https://www.scopus.com/

Note: The impact score shown here is equivalent to the average number of times documents published in a journal/conference in the past two years have been cited in the current year (i.e., Cites / Doc. (2 years)). It is based on Scopus data and can be a little higher or different compared to the impact factor (IF) produced by Journal Citation Report. Please refer to the Web of Science data source to check the exact journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

Impact Score, SJR, h-Index, and Other Important metrics of These Journals, Conferences, and Book Series

Check complete list

Studies in Higher Education Impact Score (IS) Trend

Top journals/conferences in education.

Best universities in the United States 2024

Find the best universities in the united states 2024 through times higher education’ s world university rankings data.

- Rankings for Students

Top 10 universities in the US 2024

Scroll down for the full list of best universities in the United States

Thinking about studying in the US can be overwhelming because there are so many options. Which US university is the best? Where are the top universities in the United States?

Get free support to study in the United States

We thought you might like to know the top universities in the US based on the highly respected Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2024 .

There are 169 US universities and colleges among the world’s best, so wherever you want to study in the US, a top university will not be far away. Almost all states and about 130 cities are represented in the best US universities list.

Studying at a US university as an Indian student What is it like to study at a liberal arts college? How to make friends at university in the United States Why the US is a unique study experience for international students

California is the most represented state among the best US universities for 2024, with 14 institutions, followed by 13 universities in New York, 12 universities in Texas and 10 universities in Massachusetts.

The universities at the very top of the table are concentrated in these popular destinations, which are well known for their higher education opportunities; the top three are based in California and in Massachusetts.

Everything you need to know about the Common App A guide to student bank accounts in the US The cost of studying at a university in the United States Scholarships available in the US for international students Everything you need to know about studying in the US Everything international students need to know about US student visas

Top 5 universities in the United States 2024

5. california institute of technology (caltech).

Across the six faculties at CalTech, there is a focus on science and engineering.

CalTech has an impressive number of successful graduates and affiliates, including 39 Nobel laureates, six Turing Award winners and four Fields Medallists.

There are about 2,200 students at CalTech, and the primary campus in Pasadena, near Los Angeles, covers 124 acres (about 50 hectares). Almost all undergraduates live on campus.

In addition to Nobel laureates and top researchers, the CalTech graduate community includes a number of politicians and public advisers, particularly in the areas of science, technology and energy.

All first-year students belong to one of four houses as part of the university’s alternative model to fraternities and sororities. A number of traditions and events are associated with each house.

Caltech: ‘uniquely difficult but a wonderful place to study’

4. Princeton University

Princeton University is one of the oldest universities in the US. It is part of the prestigious group of Ivy League universities.

As well as high-quality teaching and research output, the university is known for its beautiful campus, with some buildings designed by some of America’s most well-known architects.

Notable alumni who have won Nobel prizes include the physicists Richard Feynman and Robert Hofstadter and the chemists Richard Smalley and Edwin McMillan.

Princeton has also educated two US presidents, James Madison and Woodrow Wilson. Other distinguished graduates include Michelle Obama, actors Jimmy Stewart and Brooke Shields, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and Apollo astronaut Pete Conrad.

The 10 most beautiful universities in the US

3. Harvard University

Founded in 1636, Harvard University is the oldest higher education institution in the US.

About 21,000 students are enrolled, a quarter of whom are international.

Harvard University is probably the world’s best known university, topping the Times Higher Education Reputation Rankings most years.

Although tuition is expensive, Harvard’s financial endowment allows for plenty of financial aid for students.

The Harvard library system is made up of 79 libraries and is the largest academic library in the world.

Among many famous alumni, Harvard can count eight US presidents, 158 Nobel laureates, 14 Turing Award winners and 62 living billionaires.

Unlike some other universities at the top of the list, Harvard is at least equally reputed for arts and humanities as it is for science and technology, if not more so.

What is the Ivy League?

2. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

A third of MIT’s 11,000 students are international, hailing from 154 countries. Famous alumni include astronaut Buzz Aldrin, former UN secretary general Kofi Annan and physicist Richard Feynman.

MIT cultivates a strong entrepreneurial culture, which has seen many alumni found notable companies such as Intel and Dropbox.

Unusually, the undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at MIT are not wholly separate; many courses can be taken at either level.

The undergraduate programme is one of the country’s most selective, admitting only 8 per cent of applicants. Engineering and computer science are the most popular courses among undergraduates.

Women in STEM: stories from MIT students

2. Stanford University

Many faculty members, students and alumni have founded successful technology companies and start-ups, including Google, Snapchat and Hewlett-Packard. Of the 16,000 students, most of whom live on campus, 22 per cent are international.

Based in Palo Alto, right beside Silicon Valley, Stanford University has had a prominent role in encouraging the region’s tech industry to develop.

In total, companies founded by Stanford alumni make $2.7 trillion (£2.2 trillion) each year.

The university is often referred to as “the Farm” because the campus was built on the site of the Stanford family’s Palo Alto stock farm. The campus covers 8,180 acres (3,300 hectares), but more than half of the land is not yet developed.

With its distinctive sand-coloured, red-roofed buildings, Stanford’s campus is thought to be one of the most beautiful in the world. It contains a number of sculpture gardens and art museums, as well as a public meditation centre.

As might be expected from one of the best universities in the world, Stanford is highly competitive. The admission rate stands at just over 5 per cent.

Video: how I got into Stanford University as a low-income international student

Best universities in Europe Compare top Canadian universities The best universities in Asia Best universities in Australia Best universities in the UK

Top universities in the United States 2024

Click each institution to view its full World University Rankings 2024 profile

You may also like

.css-185owts{overflow:hidden;max-height:54px;text-indent:0px;} Best public universities in the United States 2022

Best private universities in the United States 2022

Best liberal arts colleges in the United States 2022

Register free and enjoy extra benefits

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Scope. Studies in Higher Education is a leading international journal publishing research-based articles dealing with higher education issues from either a disciplinary or multi-disciplinary perspective. Empirical, theoretical and conceptual articles of significant originality will be considered. The Journal welcomes contributions that seek to ...

Aims and scope. Studies in Higher Education is a leading international journal publishing research-based articles dealing with higher education issues from either a disciplinary or multi-disciplinary perspective. Empirical, theoretical and conceptual articles of significant originality will be considered.

Q1 = 25% of journals with the highest CiteScores. SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper): the number of citations per paper in the journal, divided by citation potential in the field. SJR (Scimago Journal Rank): Average number of (weighted) citations in one year, divided by the number of articles published in the journal in the previous ...

The Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2023 include 1,799 universities across 104 countries and regions, making them the largest and most diverse university rankings to date. The table is based on 13 carefully calibrated performance indicators that measure an institution's performance across four areas: teaching, research, knowledge transfer and international

The overall rank of Studies in Higher Education is 1695. According to SCImago Journal Rank (SJR), this journal is ranked 1.716. SCImago Journal Rank is an indicator, which measures the scientific influence of journals. It considers the number of citations received by a journal and the importance of the journals from where these citations come.

U.S. News factors in data on reputation, LSAT scores, job placement success and more when ranking the top law schools. 2023-2024 Best Law Schools. # 1. Stanford University (tie) # 1. Yale ...

The Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2022 include more than 1,600 universities across 99 countries and territories, making them the largest and most diverse university rankings to date. The table is based on 13 carefully calibrated performance indicators that measure an institution's performance across four areas: teaching, research, knowledge transfer and