How do you spell the Spanish slang - "essay" - meaning person?

used like, "what did you say essay?"

Hi and welcome to the forum.

It's " ese " and it means something like homeboy.

Ese is also like a thug. I wouldn't use it unless you knew the person really well.

Making educational experiences better for everyone.

Immersive learning for 25 languages

Marketplace for millions of educator-created resources

Fast, easy, reliable language certification

Fun educational games for kids

Comprehensive K-12 personalized learning

Trusted tutors for 300+ subjects

35,000+ worksheets, games, and lesson plans

Adaptive learning for English vocabulary

- Human Editing

- Free AI Essay Writer

- AI Outline Generator

- AI Paragraph Generator

- Paragraph Expander

- Essay Expander

- Literature Review Generator

- Research Paper Generator

- Thesis Generator

- Paraphrasing tool

- AI Rewording Tool

- AI Sentence Rewriter

- AI Rephraser

- AI Paragraph Rewriter

- Summarizing Tool

- AI Content Shortener

- Plagiarism Checker

- AI Detector

- AI Essay Checker

- Citation Generator

- Reference Finder

- Book Citation Generator

- Legal Citation Generator

- Journal Citation Generator

- Reference Citation Generator

- Scientific Citation Generator

- Source Citation Generator

- Website Citation Generator

- URL Citation Generator

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- AI Writing Guides

- AI Detection Guides

- Citation Guides

- Grammar Guides

- Paraphrasing Guides

- Plagiarism Guides

- Summary Writing Guides

- STEM Guides

- Humanities Guides

- Language Learning Guides

- Coding Guides

- Top Lists and Recommendations

- AI Detectors

- AI Writing Services

- Coding Homework Help

- Citation Generators

- Editing Websites

- Essay Writing Websites

- Language Learning Websites

- Math Solvers

- Paraphrasers

- Plagiarism Checkers

- Reference Finders

- Spell Checkers

- Summarizers

- Tutoring Websites

Most Popular

11 days ago

AI or Not AI? A Student Suspects One Of Their Peer Reviewer Was A Bot

10 days ago

How To Summarize A Research Article

Loose vs lose, how to cite a blog, apa paraphrasing, what does essay mean in spanish.

In the world of language learning, understanding the meaning of words across different languages is a fascinating endeavor. One such word that often captures the attention of language enthusiasts is “essay.” In this guide, we will explore what the word “essay” means in Spanish, its cultural significance, and provide valuable insights for those interested in writing essays in Spanish.

Unveiling the Translation: The Meaning of “Essay” in Spanish

When we try to find the Spanish translation for the English word “essay,” we come across the term “ensayo.” The word “ensayo” carries the essence of an essay, representing a written composition that presents a coherent argument or explores a specific topic. It is a versatile term used in various contexts, such as academic, literary, and even journalistic writing. If you’re interested in diving deeper into Spanish or other languages, online language tutoring services can be a valuable resource. They provide personalized guidance to help you understand the usage in different contexts.

Exploring Cultural Nuances: The Cultural Impact of “Essay” in Spanish

Language is deeply intertwined with culture, and understanding the cultural implications of a word is crucial for effective communication. In the context of Spanish, the word “ensayo” holds significance beyond its literal meaning. It reflects the rich literary traditions and academic rigor associated with the Spanish language.

In Spanish literature, essays play a vital role in expressing thoughts, analyzing complex ideas, and offering critical perspectives. Renowned Spanish and Latin American writers have contributed significantly to the genre, showcasing the power of essays as a means of cultural expression.

Writing Essays in Spanish: Tips and Techniques

If you are interested in writing essays in Spanish, here are some valuable tips and techniques to enhance your skills.

Understand the Structure

Just like in English, Spanish essays follow a specific structure. Start with an introduction that sets the context and thesis statement, followed by body paragraphs that present arguments or discuss different aspects of the topic. Finally, conclude with a concise summary that reinforces your main points.

Embrace Language Nuances

Spanish is known for its richness and expressive nature. Incorporate idiomatic expressions, figurative language, and varied vocabulary to add depth and flair to your essays. This will not only showcase your language proficiency but also engage your readers.

Research and Refer to Established Writers

To improve your Spanish essay writing skills, immerse yourself in the works of established Spanish and Latin American writers. Reading essays by renowned authors such as Octavio Paz, Jorge Luis Borges, or Gabriel García Márquez can provide valuable insights into the art of essay writing in Spanish.

In conclusion, the Spanish translation of the English word “essay” is “ensayo.” However, it is essential to understand that “ensayo” encompasses a broader cultural and literary significance in the Spanish language. It represents a means of expressing thoughts, analyzing ideas, and contributing to the rich tapestry of Spanish literature.

For those venturing into the realm of writing essays in Spanish, embracing the structural conventions, incorporating language nuances, and seeking inspiration from established writers will pave the way for success. So, embark on your Spanish essay writing journey with confidence and let your words resonate within the vibrant world of Spanish language and culture.

Remember, whether you are exploring literary essays, academic papers, or personal reflections, the beauty of essays lies in their ability to capture the essence of thoughts and ideas, transcending linguistic boundaries.

Are there any synonyms for the word ‘essay’ in the Spanish language?

In Spanish, there are a few synonyms that can be used interchangeably with the word “ensayo,” which is the most common translation for “essay.” Some synonyms for “ensayo” include “redacción” (composition), “prosa” (prose), and “artículo” (article). These synonyms may have slight variations in their usage and connotations, but they generally convey the idea of a written composition or discourse.

What are the common contexts where the word ‘essay’ is used in Spanish?

The word “ensayo” finds its usage in various contexts in the Spanish language. Here are some common contexts where the word “ensayo” is commonly used:

- Academic Writing: In the academic sphere, “ensayo” refers to an essay or a written composition assigned as part of coursework or academic assessments. It involves presenting arguments, analyzing topics, and expressing ideas in a structured manner.

- Literary Essays: Spanish literature has a rich tradition of literary essays. Renowned writers use “ensayo” to explore and analyze various literary works, authors, or literary theories. These essays delve into critical interpretations and provide insights into the literary landscape.

- Journalistic Writing: Journalists often employ “ensayo” to write opinion pieces or in-depth analyses on current events, social issues, or cultural phenomena. These essays offer a subjective perspective, providing readers with thoughtful reflections and commentary.

- Personal Reflections: Individuals may also write personal essays or reflections on topics of interest or experiences. These essays allow individuals to share their thoughts, feelings, and insights, offering a glimpse into their personal perspectives.

Are there any cultural implications associated with the Spanish word for ‘essay’?

Yes, there are cultural implications associated with the Spanish word for “essay,” which is “ensayo.” In Spanish-speaking cultures, essays are highly regarded as a form of intellectual expression and critical thinking. They serve as a platform for writers to convey their ideas, opinions, and reflections on a wide range of subjects.

The cultural implications of “ensayo” extend to the realm of literature, where renowned Spanish and Latin American authors have made significant contributions through their essays. These essays often explore cultural identities, social issues, historical events, and philosophical concepts, reflecting the cultural richness and intellectual depth of Spanish-speaking communities.

Moreover, the tradition of essay writing in Spanish fosters a deep appreciation for language, literature, and the exploration of ideas. It encourages individuals to engage in thoughtful analysis, promotes intellectual discourse, and contributes to the cultural and intellectual heritage of Spanish-speaking societies.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Spanish Guides

Te quiero vs. Te amo

Nov 25 2023

Learning about Parts of the Body in Spanish

Nov 24 2023

What Does Compa Mean?

Remember Me

Is English your native language ? Yes No

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Translation of essay – English-Spanish dictionary

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- I want to finish off this essay before I go to bed .

- His essay was full of spelling errors .

- Have you given that essay in yet ?

- Have you handed in your history essay yet ?

- I'd like to discuss the first point in your essay.

(Translation of essay from the Cambridge English-Spanish Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

Translation of essay | GLOBAL English–Spanish Dictionary

(Translation of essay from the GLOBAL English-Spanish Dictionary © 2020 K Dictionaries Ltd)

Examples of essay

Translations of essay.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

to add harmonies to a tune

Shoots, blooms and blossom: talking about plants

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English–Spanish Noun Verb

- GLOBAL English–Spanish Noun

- Translations

- All translations

Add essay to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Translations dictionary

or esse [ es -ey] or [ ey -sey]

What does ese mean?

Ese , amigo , hombre . Or, in English slang, dude , bro , homey . Ese is a Mexican-Spanish slang term of address for a fellow man.

Related words

Where does ese come from.

Ese originates in Mexican Spanish. Ese literally means “that” or “that one,” and likely extended to “fellow man” as shortened from expressions like ese vato , “that guy.”

There are some more elaborate (though less probable) theories behind ese . One goes that a notorious Mexican gang, the Sureños (“Southerners”), made their way from Mexico City to Southern California in the 1960s. Ese is the Spanish name for letter S , which is how the gang members referred to each other. Or so the story goes.

Ese is recorded in English for a “fellow Hispanic man” in the 1960s. It became more a general term of address by the 1980s, though ese remains closely associated (and even stereotyped) with Chicano culture in the US.

Ese is notably found in the Chicano poetry of José Antonio Burciaga and Cheech & Chong comedy routines (Cheech Marin is Mexican-American.)

White confusion over ese was memorably parodied in a 2007 episode of the TV show South Park . On it, the boys think they can get some Mexican men to write their essays , but them men write letters home to their eses .

Examples of ese

Who uses ese?

For Mexican and Mexican-American Spanish speakers, ese has the force of “dude,” “brother,” or “man,” i.e., a close and trusted friend or compatriot .

I needa kick it wit my ese's its been a minute — al (@a1anxs) February 1, 2019

It’s often used as friendly and familiar term of address…

Always a good time with my ese. 😎 pic.twitter.com/xxM4YroWDV — | Y | G | (@yg_monroe) January 12, 2019

…but it can also be more aggressively and forcefully.

Cypress Hill 2018: Who you tryin' ta mess with, ese? Don't you know I'm seeking professional help for my deep rooted emotional problemsssssss?!? — JAY. (@GoonLeDouche) June 30, 2018

“You’d have to be crazy to swipe left.” Who you tryna get crazy with, ese? Don’t you know I’m loco? Sorry, always wanted to say that. Anyway, swipe left. Might actually be crazy. — Why I Swiped Left (@LeftyMcSwiper) December 17, 2018

Ese is associated with Mexican and Chicano American culture, where it can refer to and be used by both men and women. The term is also specifically associated with Mexican-American gang culture.

What's up ese? pic.twitter.com/0vAQxZZ6SO — AlesiAkiraKitsune© (@AlesiAkira) January 21, 2019

It is often considered appropriative for people outside those cultures to use ese , especially since some non-Mexican people may use ese in ways that mock Mexicans and Mexican-American culture.

This is not meant to be a formal definition of ese like most terms we define on Dictionary.com, but is rather an informal word summary that hopefully touches upon the key aspects of the meaning and usage of ese that will help our users expand their word mastery.

- By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other categories

- Famous People

- Fictional Characters

- Gender & Sexuality

- Historical & Current Events

- Pop Culture

- Tech & Science

- Translations

Matador Original Series

3 Essential Slang Words You Need to Know Before Your Next Trip to Mexico

M exico has its own language not instructed by Spanish schools and phrase books: Mexican slang. It’s an informal language whose meanings shift in a heartbeat from insults to compliments, a language Mexican people manipulate deftly and instinctively in all sorts of contexts. The following three Mexican slang words and phrases will give you a base for you to attempt to understand and blend in with the locals.

Mexican slang word #1: Cabrón

A cabrón can either be a badass or a real jerk, a male you talk about with disgust or fear.

There’s also the feminine version, cabrona. Same standards apply: There are the the revered, awe-inducing cabronas and the detested ones.

Then there’s “qué cabrón,” a phrase used to describe a thing or situation as opposed to a person. This, too, can be positive or negative, but it’s got a particular edge to it. For example:

1. Narcos entered a popular restaurant and collected the cell phones of all the customers, warning them not to make any phone calls or act out of the ordinary. The narcos ate peacefully, returned the cell phones, paid everyone’s bills, and continued on their way. Qué cabrón.

2. You ran out of water, and the government isn’t sending more water to the Centro Histórico for three days. You just had a party and now have a sink full of beer glasses, skillets full of chipotle sausage residue, and greasy plates. Qué cabrón.

Insider tip for Mexican slang mastery: For added flair, add an “ay” before cabrón when used for people, and mix it up with an “está cabrón” instead of “que cabrón” in the case of situations.

Mexican slang word #2: Madre

In the quintessential Mexican read, The Labyrinth of Solitude , Octavio Paz has a great passage about the significance of la madre (“the mother”) in Mexican slang and culture.

The madre is identified with all things negative, the padre with all things positive. This, argues Paz, is a reflection of two historical and cultural factors in Mexico.

The first is the idea of the long-suffering mother, the passive recipient of pain and burden who is, to use another classic Mexican slang term, chingada (meaning “screwed,” for a polite interpretation).

The second is the historical resentment and resignation towards the woman whom Paz claims is the mother of modern Mexico — La Malinche. La Malinche was a Nahuatl woman who aided Cortéz in the colonization of Mexico, translating for him, offering insider information, and giving him a son.

So la madre is not treated kindly by Mexican slang. Whether you feel squeamish about it or not, be prepared to hear at least one of the following Mexican slang phrases on a daily basis:

1. Qué madres: what the hell? As in, the sudden explosion of firecrackers on any random street corner, the drunken antics of your friend after too much mezcal , the thing floating in your soup.

2. Que poca madre tienes: literally, how little mother you have, this Mexican slang phrases when directed at you means that you’re so rude and act so badly that it’s like you had no mother to raise you.

3. Es poca-madre: The hyphen and the use of the verb “ser” makes all the difference — it translates as “amazing.” So if Mexico kills in soccer with a 5-0 victory, it’s definitely poca-madre.

4. Hasta la madre utterly sick of something. Your boyfriend’s behavior could drive you to feeling hasta la madre, and so could consistent rain every afternoon or the incessant barking of the dog next door. You’re at the end of your rope, the breaking point. To translate the phrase directly, you’re almost “to the point of motherhood.”

5. Padre: Means “cool.” Plain and simple. So if you score great concert tickets for you and your friends, it’s padre.

Mexican slang word #3: Huevos

There’s a whole linguistic universe surrounding huevos here, so let’s just stick to the most commonly used.

1. Qué huevón/huevona: “What a lazy egg.”

2. Qué hueva: It translates literally as “what egginess.” Eggs here have the same association with laziness with an additional component of boredom. For example, you could toss out a “que hueva” at the suggestion of watching soccer on TV.

A version of this article was previously published on August 18, 2009, and was updated on February 14, 2022.

More like this

Trending now, 16 cancún airbnbs for an unforgettable beach vacation, embrace cancún’s energy and counter with calm at this riviera maya resort, adults, this restful all-inclusive in mexico’s riviera maya is for you, discover matador, adventure travel, train travel, national parks, beaches and islands, ski and snow.

Being Latina and the struggle of the dualities of two worlds

Reflections on why our identities can help create a better world for all of us.

A few days ago, I attended a Zoom presentation organized by ASUN entitled “What does it mean to be Latinx?” Every time I witness the complexity of identities in the Latinx community in the United States, I am amazed. Amazed that we are always perceived as a homogenous group, when in reality, we couldn’t come from more different backgrounds, and we couldn’t have more different and complex identities. Also, the challenges we face are as different as each of our stories. So, in the spirit of Hispanic Heritage Month, please indulge me in letting me tell you my story.

There is a well-known character in Mexican history that invokes both love and condemnation from most Mexicans. Her name was Malintzin but history knows her as La Malinche . Her story is similar to that of U.S.A.’s Pocahontas ; the beautiful indigenous woman who abandons her tribe to help the white man. (The legends omit how she became the property of such White men, but that’s another story).

La Malinche was a Nahúatl woman who was given to Hernán Cortés as a slave. Due to her upperclass education, she spoke two languages, an ability that made her very useful to Hernán Cortés in communicating with the indigenous people as he went about conquering Mexico. On one hand, she was intelligent and, clearly, resilient. But on the other hand, she helped Cortés begin the Spanish colonization of the Nuevo Mundo. This duality is what gives her such a complex identity. And this duality is one that follows me.

When I was in high school, several of my classmates would sometimes call me Malinchista . As you can imagine, that was NOT a compliment. By definition, a Malinchista is “a person who denies her own cultural heritage by preferring foreign cultural expressions” (I’m not making it up; look it up).

In my early teens, I discovered American football. While switching channels on the television, I stumbled across a game being played in several feet of snow. I had never seen this! The game was being played in Minnesota. That year, the Dallas Cowboys won the Super Bowl, and I became a die-hard fan of Roger Staubach and “America’s Team.” This marked the initiation of my love for all things American. I learned about Formula 1, Sports Illustrated and Tiger Beat. Yes, Tiger Beat introduced me to the American darlings of my generation. My bedroom walls were covered with pictures of American teen idols I had never seen before in my life (in the 1970s, Mexican TV programming didn’t broadcast many American TV shows; I only remember Dallas and The Partridge Family , which of course, I loved).

I also loved English-language songs. I used to spend my money buying cancioneros , books similar in format and quality to comic books, for people who were learning to play the guitar. The cancioneros had the lyrics of the songs along with the music notes. I literally used these cancioneros to practice my English. I would translate each word of the songs, and then I would play the records over and over until I memorized the lyrics and could actually follow the singer pronouncing the words. Do you know how hard it is to sing at full speed: “Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall?”

By the time I was in college, I had already spent time in the city of Dallas (and yes, I made the pilgrimage to Irving, Texas and the Cowboys’ stadium) – and perfected my English. I started studying English when I entered first grade. By middle school, my parents were paying a private tutor. In Mexico, English was accepted as the lingua franca needed to succeed in the world, and my parents were going to make sure I learned it. (My dad had taught himself English, and he shared my enthusiasm for English language magazines, although not for the Dallas Cowboys.) Learning a second language allowed me to learn about, navigate and integrate into a different culture. And, unlike La Malinche , I did this of my own volition.

When I made the decision to come to the United States to study, my father told me, “If you ever decide this is not for you or things don’t work out, come back home.” But I was not turning back. In my mind, America was the best place in the whole world (my small world, at least). I had spent a semester in an exchange program at the University of Oklahoma, and I knew back then I belonged in the United States. One of the things that caught my attention early on was the fact that people could wear their pajamas to class (I know you’ve seen it), and nobody blinked an eye. One could wear her hair in blue spikes or wear slippers to the grocery store, and no one would say a thing. To me, that was amazing! People didn’t bother you, judge you or care what you wore. I felt America was the place where not only public services worked, but where you could be yourself and you could be free to be whomever you wanted to be. There was a sense of freedom that was refreshing.

However, for a long time I felt like I didn’t belong here, and I didn’t belong in Mexico, either. Navigating two worlds was not precisely difficult but sometimes unsettling . You spend your time “live switching” from English to Spanish to Spanglish and back again. You mix Cholula with Five Guys hamburgers. You watch American soccer but listen to the Mexican commentators (otherwise it’s like listening to golf announcers). And you truly think Mexican soccer fans are like the old Oakland Raiders fans, only worse. Women in Mexico are as rabid fans as many men, but, at least back in my day (I feel ancient now), you didn’t see many women go to the stadiums. As a woman, I never felt safe. I only went to a match if my male friends went with me. This is one of the most striking differences between the U.S. and Mexico: American soccer fans are so mild-mannered in comparison!

Another striking difference I noticed when I first came to the U.S. was that I was not getting cat calls out when I was out walking in the streets. In Mexico, everywhere I went (since I was a preteen, for goodness’ sake), I would be subjected to cat calls and whistles – and the harassment only got worse the older I got. My experience as a woman was of always being on high alert. But when I came to the U.S., I felt respected. I could exist without being harassed continually. Women here seemed to have a voice and the same opportunities as men to grow and pursue their dreams. I felt free to pursue a career and to not be expected to only dream of marrying and having children. Although, over the years, I’ve come to realize there still is much room for improvement.

Back in the 1500s La Malinche did what she could to survive (did I say historians think she died before she was 30?). History asked her to do a task she didn’t want, and she did her best. I am sure she considered her options and bought time, respect and the right to live in the best way she could. She used her skills to earn a place in history, and although her role continues to be debated, I cannot blame her. Did I turn my back on my country? Or did I look for a better life? My circle of Latina friends in the U.S. is full of intelligent, professional women who left their countries and built a better life – a different life – here in the United States. They all miss their families, and they all support their biological families in many ways. What they can do from here, however, is more than they could have done had they stayed in their countries of origin.

Being Latina in America is both an honor and a challenge. We struggle with the dualities of our worlds. We struggle with the adjectives that define us. We are a complex mix of races, traditions and experiences. We care for our people, and we work tirelessly to do what must be done to help each other. The complexity of our identities can help us create a better world for all of us, a world where our differences are not viewed as a threat but as an asset. A world where we all thrive. ¡Sí, se puede!

By: Claudia Ortega-Lukas Graphic Designer & Communications Professional

Living The Wolf Pack Way: Outstanding Letter of Appointment winner Jocelyn Mata’s journey

Jocelyn Mata describes how family, hard work and opportunity led her to become an oncology social worker with Renown Health and teach in the School of Social Work at the University of Nevada, Reno

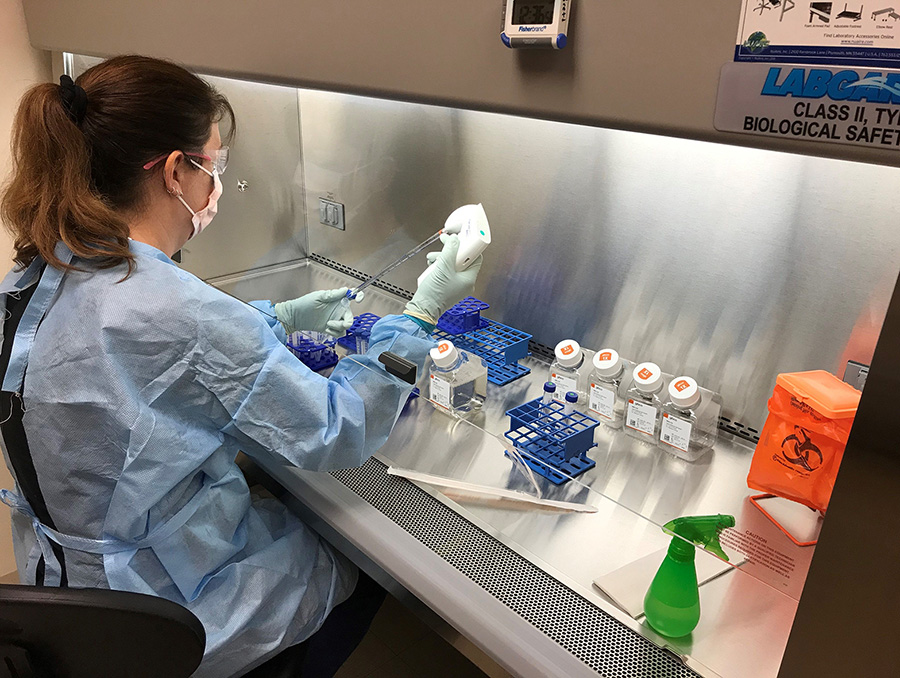

Biomedical Research Awareness Day BRAD 2024

Bradley Ferguson encourages you to stop by the info table and come to a lunch-and-learn session April 18 to celebrate #BRADGlobal

Presenting Virtual Reality in Japan

Michael Wilson, specialist, Virtual Reality Programming & Development for University Libraries, discusses his experience demonstrating VR work from the @One while visiting Japan

History of Student Life on Campus

Sesquicentennial Archivist Rebecca Sparagowski dives into the history of student life on campus in a new exhibit from University Libraries

Editor's Picks

Anthropology doctoral candidate places second in regional Three-Minute Thesis Competition

A look at careers of substance and impact

NASA astronaut Eileen Collins shares stories at Women in Space event

University of Nevada, Reno and Arizona State University awarded grant to study future of biosecurity

Nevada Today

University Professor Deborah Boehm and team contribute to a guide for preparing publicly engaged scholars

“Build Bridges, Not Walls” encourages meaningful community engagement

Giving Day: The Wolf Pack Way

Help raise vital funds campuswide by donating to the area that matters most to you on Thursday, April 11

Finding her ‘why’ – one medical student’s journey

Taree Chadwick, M.D. Class of 2024, shares why she decided to switch career paths and become a doctor

University of Nevada, Reno President Brian Sandoval named to State of Nevada Awards and Honor Board Selection Committee

Speaker of the Nevada Assembly Steve Yeager appointed President Sandoval and Former Governor Bob Miller for 3-year terms

Students versus staff in the fight against food waste

A Pack Place battle for sustainability with WasteNot 2.0

Foundation Outstanding Letter of Appointment Instructional Faculty Award and Exceptional Letter of Appointment Instructional Faculty College/School Awards for fall 2023

Awardees are recognized for their exemplary service to students and individual achievements

FAA grants civil UAS operations waiver for University operated Nevada Autonomous Test Site

1,000 square-mile test site area in Northern Nevada, first in a series of sites planned for drone research, development, testing

Kendra Isable represented the University at the Western Association of Graduate Schools annual conference

For Latinos, a Spanish word loaded with meaning

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

When Boyle Heights shop owner Arturo Macias hears fellow Latinos use the Spanish word for “wetback,” he doesn’t necessarily take offense.

Macias, who crossed illegally into the U.S. through Tijuana two decades ago, has heard the term “ mojado ” for much of his life and sees it less as an insult than a description of a common immigrant experience.

“As a country of immigrants,” he says in Spanish, “in one way or another, we’re all mojados .”

Macias is very offended, however, when he hears a non-Latino say “wetback.” That distinction befuddles his 20-year-old daughter Karina.

“It definitely is a term to divide people,” she said. “You can’t use it as a term of endearment at all, whether it’s someone outside of your culture or not.”

An Alaska’s congressman’s reference to “wetbacks” during a radio interview last week stirred an uproar and he was forced to apologize. In Latino communities, the episode highlighted how cultural reactions to the word have changed through generations.

Everyone seems to agree that the English version of the term is highly offensive to Latinos when others use it. But when Latinos use mojado — which literally means “wet” but is also used to describe illegal immigrants in the United States — it’s different.

“My grandfather, for all practical purposes, was a mojado . They call each other mojados ,” veteran Latino activist Arnoldo Torres said. “It’s about understanding the complexity. Of seven, eight, nine, generations of Latinos that have lived in the United States.”

Torres was already dealing with the fallout of the word 30 years ago.

In 1983, Ernest Hollings, a South Carolina senator running for the Democratic presidential nomination, used the English term at a dinner during a campaign stop in Des Moines. Hollings apologized and met with a group of Latino leaders, including Torres, then the executive director of the League of United Latin American Citizens.

“We said, ‘Look, this is why it’s offensive.’ We weren’t looking for some astronomical apology,” Torres said. “Our hope was very simple. If we’re able to educate him, maybe he can tell others.”

Each time the word resurfaces, it carries with it a long history and a nuanced reputation.

The English term, originally coined after Mexicans illegally entered the U.S. by swimming or wading across the Rio Grande, evolved to include a broader group of immigrants who entered into the country on foot or in cars. The Spanish translation espaldas mojadas , is typically shortened to just mojado or mojada , depending on the person’s gender.

In 1954, as the U.S. economy sputtered to find its footing after the Korean War, the government launched the now-infamous Operation Wetback, a deportation drive that sent Mexicans back to Mexico in droves and roused complaints of racial profiling and fractured families.

During that decade, the term was still splashed across the pages of the country’s major newspapers.

In 1952, the New York Times ran a story under the headline: “Hero in Korean War Deported as Wetback; Served in Army 3 Years After Entering U.S.” Three years later, the Associated Press wrote a story about “the ‘wetback invasion’ across the Mexican border.” And Angelenos at the time read headlines like “Wetback, 16, Gets School Diploma in Jail” and “Roundup of Wetbacks in L.A. Still On,” in the Los Angeles Times.

Amin David, a Latino rights activist from Orange County, remembers when Latinos could joke with one another about the term — “One of the jokes that we used to say was that if we crossed the Rio Grande we wouldn’t even get our backs wet because there was no water,” he recalled.

“It moved from a humorous-type label to a very derogatory one,” David said, adding that he noticed the shift begin in the 1960s.

Gustavo Arellano, editor of the OC Weekly and author of the syndicated ¡Ask a Mexican! column, said the term started to drop off in the 1980s and ‘90s. As its usage waned, “illegal alien” gained footing.

“When you want to insult Mexicans, calling them a ‘wetback’ is so 1950s,” Arellano said. “It’s so dated.”

The Alaska congressman who sparked the most recent furor is Republican Don Young. He spoke of “50 to 60 wetbacks” who picked tomatoes at his father’s farm in California.

“I used a term that was commonly used during my days growing up on a farm in Central California,” he said in an apology Friday. “I know that this term is not used in the same way nowadays, and I meant no disrespect.”

For Raul Ruiz, a professor of Chicano Studies at Cal State Northridge, Young’s apology was a bit off. He conceded that the term used to be more common, but doesn’t think it used to be any less offensive.

Ruiz, 70, admits some Latinos use mojados freely. But he says it has a different meaning coming from an Anglo.

“I’m not trying to excuse it, but the word mojado isn’t totally a pejorative in the way Mexicans use it in referring to themselves,” Ruiz said. “It really isn’t as mean-spirited at all.”

Back at Macias’ clothing shop in Boyle Heights, his family continued to discuss the term.

For Karina Macias, a UC Berkeley student who spent a recent afternoon during her spring break helping her parents run the shop, Young’s words are surprising given the growing political clout of Latinos.

“As the Latino population increases, the Latino impact on society increases,” she said. “If there’s a Latino in office, you can’t put ‘wetback’ in the headlines.”

She turned to her mother, who was leaning on the counter near the cash register, and asked her, in Spanish, what she thought about the word “ mojado .”

The raven-haired woman with a sweet smile put her hand on her chest and raised her eyebrows. “Wow,” she said, shocked to hear her daughter use the term. “I think it’s offensive, it has always been offensive.”

Arturo simply smiled and shrugged.

More to Read

Column: California Latinos have become more skeptical of undocumented immigrants. What changed?

Feb. 9, 2024

California banned a slur from geographic place names. Fresno County won’t let go

Jan. 30, 2024

Column: Jose Huizar was our rancho’s American dream. Now, he’s headed to prison for 13 years

Jan. 26, 2024

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Marisa Gerber is an enterprise reporter at the Los Angeles Times. A finalist for the Livingston Award, she joined The Times in 2012.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Repairs on Big Sur’s collapsed Highway 1 start this week. No telling when they will end

What’s the cloud forecast for the solar eclipse in Los Angeles?

After $30-million L.A. heist, can DNA, fingerprints, video help crack case?

Your last-minute guide to enjoying the solar eclipse — in L.A. and beyond

What is the difference between a solar eclipse and a lunar eclipse?

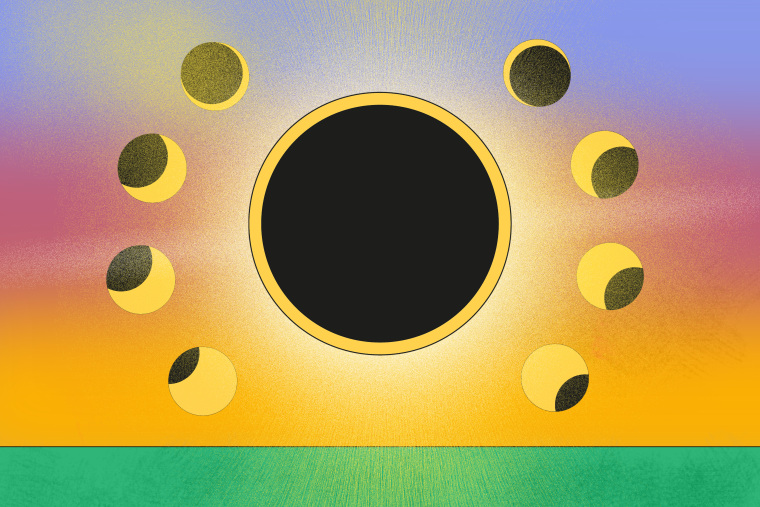

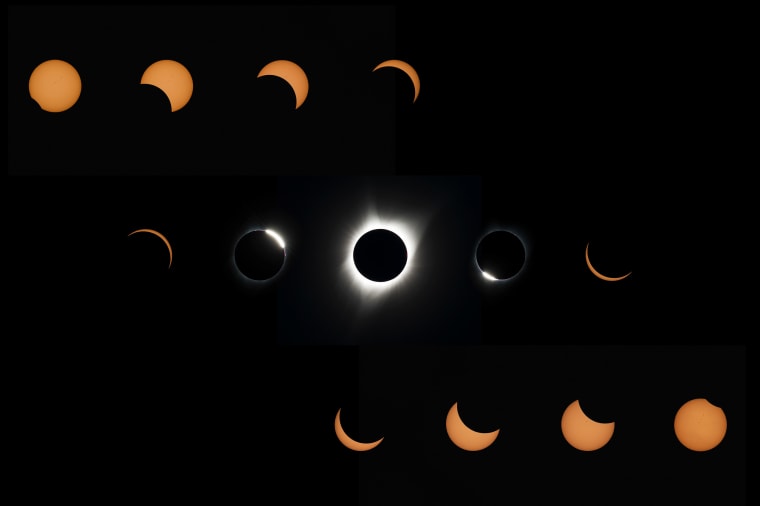

It almost time! Millions of Americans across the country Monday are preparing to witness the once-in-a-lifetime total solar eclipse as it passes over portions of Mexico, the United States and Canada.

It's a sight to behold and people have now long been eagerly awaiting what will be their only chance until 2044 to witness totality, whereby the moon will completely block the sun's disc, ushering in uncharacteristic darkness.

That being said, many are curious on what makes the solar eclipse special and how is it different from a lunar eclipse.

The total solar eclipse is today: Get the latest forecast and everything you need to know

What is an eclipse?

An eclipse occurs when any celestial object like a moon or a planet passes between two other bodies, obscuring the view of objects like the sun, according to NASA .

What is a solar eclipse?

A total solar eclipse occurs when the moon comes in between the Earth and the sun, blocking its light from reaching our planet, leading to a period of darkness lasting several minutes. The resulting "totality," whereby observers can see the outermost layer of the sun's atmosphere, known as the corona, presents a spectacular sight for viewers and confuses animals – causing nocturnal creatures to stir and bird and insects to fall silent.

Partial eclipses, when some part of the sun remains visible, are the most common, making total eclipses a rare sight.

What is a lunar eclipse?

A total lunar eclipse occurs when the moon and the sun are on exact opposite sides of Earth. When this happens, Earth blocks the sunlight that normally reaches the moon. Instead of that sunlight hitting the moon’s surface, Earth's shadow falls on it.

Lunar eclipses are often also referred to the "blood moon" because when the Earth's shadow covers the moon, it often produces a red color. The coloration happens because a bit of reddish sunlight still reaches the moon's surface, even though it's in Earth's shadow.

Difference between lunar eclipse and solar eclipse

The major difference between the two eclipses is in the positioning of the sun, the moon and the Earth and the longevity of the phenomenon, according to NASA.

A lunar eclipse can last for a few hours, while a solar eclipse lasts only a few minutes. Solar eclipses also rarely occur, while lunar eclipses are comparatively more frequent. While at least two partial lunar eclipses happen every year, total lunar eclipses are still rare, says NASA.

Another major difference between the two is that for lunar eclipses, no special glasses or gizmos are needed to view the spectacle and one can directly stare at the moon. However, for solar eclipses, it is pertinent to wear proper viewing glasses and take the necessary safety precautions because the powerful rays of the sun can burn and damage your retinas.

Contributing: Eric Lagatta, Doyle Rice, USA TODAY

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Mexican Nationalism

Introduction, official histories.

- Eugenic Nationalism

- The Ensayista Tradition

- Critiques of the Ensayista Tradition

- Mexican Nationalism in International Contexts

- Government-Sponsored Mass Media and Popular Culture

- Film, Television, Sport, and Commercial Culture

- Countermythologies

- Popular Nationalisms

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Cárdenas and Cardenismo

- Cultural History

- State and Nation Formation in Pre-Revolutionary Mexico

- The Era of Porfirio Díaz, 1876–1911

- The Novel of the Mexican Revolution

- Zapatista Rebellion in Chiapas

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Economies in the Era of Nationalism and Revolution

- The Spanish Pacific

- Violence and Memory in Modern Latin America

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Mexican Nationalism by Anne Rubenstein , Kevin Chrisman LAST MODIFIED: 27 February 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199766581-0208

Mexican nationalist thought, as articulated by Mexico’s most powerful politicians, scholars, and writers, was never intended to describe the nation as it was or as it is. Instead, it has always expressed aspirations: it has contained multiple and often-conflicting visions of the nation as it could be, should be, or might have been. Such nationalist thinking has followed two broad tracks. One is historical. It argues that the Mexican national character— lo mexicano, mexicanidad , the essence of what it is to be Mexican—was formed through the experience of a national history that was a series of painful and unfair losses overcome by heroism and persistence. This historical narrative begins with the conquest, culminates in the loss of almost half the national territory to the United States in 1848, and is brought to a happy conclusion by the Mexican Revolution. The other track that Mexican nationalist thought has followed has to do with race. Intellectuals and politicians have changed their conceptions of the relationship between Mexico’s indigenous people and other Mexicans over the years, with the most radical shift taking place in the transition from the Porfiriato to the Revolutionary government. But across the modern era in Mexico, the presence of indigenous people, the influence of indigenous cultures, and the memory of indigenous civilizations have shaped how Mexicans understand themselves and their nation. Both of these narratives have changed over time, being rewritten and reconstructed to serve the needs of a national state that was almost constantly in the process of remaking itself from independence through the first half of the 20th century. Both of these nationalist narratives, moreover, have been subject to intense scrutiny from revisionist historians, feminists, indigenous people, and other critics since at least the mid-1960s. Neither of these nationalist narratives has ever been fully accepted by the majority of Mexicans: alternative narratives emerged from—among others—peasant and indigenous communities, urban underclasses, and Catholic groups, and these narratives gave strength and shape to multiple forms of political and cultural resistance. Nonetheless, these twin discourses of Mexican nationalism persist in Mexico because they are embedded in so many aspects of daily life: textbooks, public policies, classic films, monuments, maps, and cookbooks.

Few good, general scholarly overviews of Mexican nationalism from the Independence era to the 2010s are available in English, although Brading 1991 and Lomnitz 2001 (the latter cited under Countermythologies ) cover the colonial and early national periods and the post-Revolutionary era, respectively. For the most part, this section contains texts that present or analyze some part of the official history of Mexico, which is one of the two primary underpinnings of Mexican nationalism. This nationalist-historical narrative has been presented in textbooks and political debates, among other sites, and had been an important part of school curriculums from the beginning of public education in Mexico, as shown in Vaughan 1982 and Vaughan 1997 . This highly stylized story begins with the preconquest civilizations of Mesoamerica and normally concludes with the Revolutionary governments. A highly influential synthesis, Cosío Villegas 1976 , began to open the nationalist-historical narrative to some revisionist accounts and took the story through the upheavals of the late 1960s. More recently, textbooks and reference works have ventured as far as 2010, which makes the story even less smooth and seamless, as in Velásquez García, et al. 2010 . However, the more standard account—from the tragedy of the Conquest through the tragedy of the loss of the North, followed by a history centered on the deeds and characters of a small number of political leaders—reemerged in Krauze 1997 . The patriotic historical narrative taught in Mexican schools is also embedded in maps, as seen in Craib 2004 , and in national holidays, as shown in Beezley, et al. 1994 and Esposito 2010 . Sheppard 2016 suggests the uses of this narrative for opponents of the Mexican post-Revolutionary state as well as for its supporters. For the presence of Mexico’s official history in visual art, see the section on Art History . For the philosophical and social-scientific literature, which used this story to underpin essays on the national character, see the sections on the Ensayista Tradition and Critiques of the Ensayista Tradition .

Beezley, William, William E. French, and Cheryl Martin, eds. Rituals of Rule, Rituals of Resistance: Public Celebrations and Popular Culture in Mexico . Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1994.

The articles in this book begin with 16th-century religious festivals and conclude with village brass bands of the 1970s, connecting popular celebrations to the national mythology that grew up around them.

Brading, David. The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492–1867 . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Brading argues that Mexicans’ consciousness of themselves as creoles, defined in opposition to peninsulares (Spaniards), developed gradually across the colonial period and determined the form of the Mexican state post-independence.

Cosío Villegas, Daniel, ed. Historia general de México . Mexico City: Colegio de México, 1976.

Although it was never meant as a textbook, this and subsequent editions of the Historia general became the indispensable guide to Mexico’s past for anyone teaching Mexican history. Beginning with cautious departures from the official history, in its final editions (most recently the fourth edition, published in 1998) it had fully incorporated the revisionism offered by social historians.

Craib, Raymond B. Cartographic Mexico: A History of State Fixations and Fugitive Landscapes . Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

This cartographic history demonstrates that maps served as important symbols to unify the country around an identifiable picture. They also helped strengthen Mexico’s national identity domestically and internationally.

Esposito, Matthew D. Funerals, Festivals, and Cultural Politics in Porfirian Mexico . Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2010.

This book examines the importance of state-sponsored funerals and festivals during the Porfiriato , and their relation to the construction of historical narrative and national identity. Esposito argues that commemorations and rituals allowed the state to project its power and create a unified nationalism.

Krauze, Enrique. Mexico, Biography of Power: A History of Modern Mexico, 1810–1996 . Translated by Hank Heifitz. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

Emulating earlier ambitious Mexican intellectuals, Krauze combines a standard account of Mexican history before 1880 with a historical narrative for the Porfiriato and beyond that is, essentially, a series of political biographies of the nation’s rulers. These biographical sketches include some discussion of Krauze’s own relationships with some Mexican presidents.

Sheppard, Randal. A Persistent Revolution: History, Nationalism, and Politics in Mexico since 1968 . Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2016.

Since 1968, both the state and popular movements have evoked historical myths of Mexico’s Revolutionary nationalism as ways to promote or justify their political causes.

Vaughan, Mary Kay. The State, Education, and Social Class in Mexico, 1880–1928 . DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1982.

The Mexican Revolution made education more accessible, Vaughan writes, while continuing the Porfirian practice of using schools to inculcate national pride and loyalty to the state.

Vaughan, Mary Kay. Cultural Politics in Revolution: Teachers, Peasants, and Schools in Mexico, 1930–1940 . Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1997.

Post-Revolutionary-constructed state schools in rural Mexican communities provided sites for public dialogue that negotiated power between the local and the national. Rural communities used the schools as spaces to protect their local cultures, while the state used schools to craft a multiethnic populist nationalism based on ideas of development.

Velásquez García, Erik, Enrique Nalda, Pablo Escalante Gonzalbo, et al. Nueva historia general de México . Mexico City: Colegio de México, 2010.

This “New Brief History of Mexico” revises Cosío Villegas’s original Breve historia and was written by a team of distinguished historians (like the original). Expanded to sixteen chapters and 818 pages, it retains the structure of the original, organizing Mexican history around political change and—in the modern period—emphasizing the role of the United States. Unlike the original, it brings the story to the moment of its publication.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Latin American Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abortion and Infanticide

- African-Descent Women in Colonial Latin America

- Agricultural Technologies

- Alcohol Use

- Ancient Andean Textiles

- Andean Contributions to Rethinking the State and the Natio...

- Andean Music

- Andean Social Movements (Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru)

- Anti-Asian Racism

- Antislavery Narratives

- Arab Diaspora in Brazil, The

- Arab Diaspora in Latin America, The

- Argentina in the Era of Mass Immigration

- Argentina, Slavery in

- Argentine Literature

- Army of Chile in the 19th Century

- Asian Art and Its Impact in the Americas, 1565–1840

- Asian-Peruvian Literature

- Atlantic Creoles

- Baroque and Neo-baroque Literary Tradition

- Beauty in Latin America

- Bello, Andrés

- Black Experience in Colonial Latin America, The

- Black Experience in Modern Latin America, The

- Bolaño, Roberto

- Borderlands in Latin America, Conquest of

- Borges, Jorge Luis

- Bourbon Reforms, The

- Brazilian Northeast, History of the

- Brazilian Popular Music, Performance, and Culture

- Buenos Aires

- California Missions, The

- Caribbean Philosophical Association, The

- Caribbean, The Archaeology of the

- Cartagena de Indias

- Caste War of Yucatán, The

- Caudillos, 19th Century

- Cádiz Constitution and Liberalism, The

- Central America, The Archaeology of

- Children, History of

- Chile's Struggle for Independence

- Chronicle, The

- Church in Colonial Latin America, The

- Chávez, Hugo, and the Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela

- Cinema, Contemporary Brazilian

- Cinema, Latin American

- Colonial Central America

- Colonial Latin America, Crime and Punishment in

- Colonial Latin America, Pilgrimage in

- Colonial Legal History of Peru

- Colonial Lima

- Colonial New Granada

- Colonial Portuguese Amazon Region, from the 17th to 18th C...

- Comics, Cartoons, Graphic Novels

- Contemporary Indigenous Film and Video Production

- Contemporary Indigenous Social and Political Thought

- Contemporary Maya, The

- Cortés, Hernán

- Cuban Revolution, The

- de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, Fernando

- Dependency Theory in Latin American History

- Development of Architecture in New Spain, 1500–1810, The

- Development of Painting in Peru, 1520–1820, The

- Drug Trades in Latin America

- Dutch in South America and the Caribbean, The

- Early Colonial Forms of Native Expression in Mexico and Pe...

- Economies from Independence to Industrialization

- Ecuador, La Generación del 30 in

- Education in New Spain

- El Salvador

- Enlightenment and its Visual Manifestations in Spanish Ame...

- Environmental History

- Era of Porfirio Díaz, 1876–1911, The

- Family History

- Film, Science Fiction

- Football (Soccer) in Latin America

- Franciscans in Colonial Latin America

- From "National Culture" to the "National Popular" and the ...

- Gaucho Literature

- Gender and History in the Andes

- Gender during the Period of Latin American Independence

- Gender in Colonial Brazil

- Gender in Postcolonial Latin America

- Gentrification in Latin America

- Guaman Poma de Ayala, Felipe

- Guaraní and Their Legacy, The

- Guatemala and Yucatan, Conquest of

- Guatemala City

- Guatemala (Colonial Period)

- Guatemala (Modern & National Period)

- Haitian Revolution, The

- Health and Disease in Modern Latin America, History of

- History, Cultural

- History, Food

- History of Health and Disease in Latin America and the Car...

- Honor in Latin America to 1900

- Honor in Mexican Public Life

- Horror in Literature and Film in Latin America

- Human Rights in Latin America

- Immigration in Latin America

- Independence in Argentina

- Indigenous Borderlands in Colonial and 19th-Century Latin ...

- Indigenous Elites in the Colonial Andes

- Indigenous Population and Justice System in Central Mexico...

- Indigenous Voices in Literature

- Japanese Presence in Latin America

- Jesuits in Colonial Latin America

- Jewish Presence in Latin America, The

- José María Arguedas and Early 21st Century Cultural and Po...

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de

- Latin American Independence

- Latin American Multispecies Studies

- Latin American Theater and Performance

- Latin American Urbanism, 1850-1950

- Law and Society in Latin America since 1800

- Legal History of New Spain, 16th-17th Centuries

- Legal History of the State and Church in 18th Century New ...

- LGBT Literature

- Literature, Argentinian

- Machado de Assis

- Magical Realism

- Maroon Societies in Latin America

- Marriage in Colonial Latin America

- Martí, José, and Cuba

- Menchú, Rigoberta

- Mesoamerica, The Archaeology of

- Mestizaje and the Legacy of José María Arguedas

- Mexican Nationalism

- Mexican Revolution, 1910–1940, The

- Mexican-US Relations

- Mexico, Conquest of

- Mexico, Education in

- Mexico, Health Care in 20th-Century

- Migration to the United States

- Military and Modern Latin America, The

- Military Government in Latin America, 1959–1990

- Military Institution in Colonial Latin America, The

- Mining Extraction in Latin America

- Modern Decorative Arts and Design, 1900–2000

- Modern Populism in Latin America

- Modernity and Decoloniality

- Music in Colonial Latin America

- Musical Tradition in Latin America, The

- Mystics and Mysticism

- Native Presence in Postconquest Central Peru

- Natural Disasters in Early Modern Latin America

- Neoliberalism

- Neruda, Pablo

- New Conquest History and the New Philology in Colonial Mes...

- New Left in Latin America, The

- Novel, Chronology of the Venezuelan

- Novel of the Mexican Revolution, The

- Novel, 19th Century Haitian

- Novel, The Colombian

- Nuns and Convents in Colonial Latin America

- Oaxaca, Conquest and Colonial

- Ortega, José y Gasset

- Painting in New Spain, 1521–1820

- Paraguayan War (War of the Triple Alliance)

- Pastoralism in the Andes

- Paz, Octavio

- Perón and Peronism

- Peru, Colonial

- Peru, Conquest of

- Peru, Slavery in

- Philippines Under Spanish Rule, 1571-1898

- Photography in the History of Race and Nation

- Political Exile in Latin America

- Ponce de León

- Popular Culture and Globalization

- Popular Movements in 19th-Century Latin America

- Portuguese-Spanish Interactions in Colonial South America

- Post Conquest Aztecs

- Post-Conquest Demographic Collapse

- Poverty in Latin America

- Preconquest Incas

- Pre-conquest Mesoamerican States, The

- Pre-Revolutionary Mexico, State and Nation Formation in

- Printing and the Book

- Prints and the Circulation of Colonial Images

- Protestantism in Latin America

- Puerto Rican Literature

- Religions in Latin America

- Revolution and Reaction in Central America

- Rosas, Juan Manuel de

- Sandinista Revolution and the FSLN, The

- Santo Domingo

- Science and Empire in the Iberian Atlantic

- Science and Technology in Modern Latin America

- Sephardic Culture

- Sexualities in Latin America and the Caribbean

- Slavery in Brazil

- South American Dirty Wars

- South American Missions

- Spanish American Arab Literature

- Spanish and Portuguese Trade, 1500–1750

- Spanish Caribbean In The Colonial Period, The

- Spanish Colonial Decorative Arts, 1500-1825

- Spanish Florida

- Spiritual Conquest of Latin America, The

- Sports in Latin America and the Caribbean

- Studies on Academic Literacies in Spanish-Speaking Latin A...

- Telenovelas and Melodrama in Latin America

- Textile Traditions of the Andes

- 19th Century and Modernismo Poetry in Spanish America

- 20th-Century Mexico, Mass Media and Consumer Culture in

- 16th-Century New Spain

- Tourism in Modern Latin America

- Transculturation and Literature

- Trujillo, Rafael

- Tupac Amaru Rebellion, The

- United States and Castro's Cuba in the Cold War, The

- United States and the Guatemalan Revolution, The

- United States Invasion of the Dominican Republic, 1961–196...

- Urban History

- Urbanization in the 20th Century, Latin America’s

- US–Latin American Relations during the Cold War

- Vargas, Getúlio

- Venezuelan Literature

- Women and Labor in 20th-Century Latin America

- Women in Colonial Latin American History

- Women in Modern Latin American History

- Women's Property Rights, Asset Ownership, and Wealth in La...

- World War I in Latin America

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|162.248.224.4]

- 162.248.224.4

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

The ways hispanics describe their identity vary across immigrant generations.

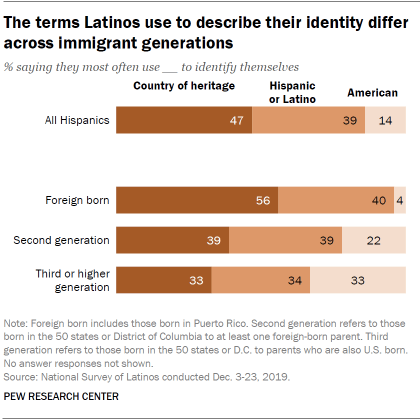

The terms Hispanics in the United States use to describe themselves can provide a direct look at how they view their identity and how the strength of immigrant ties influences the ways they see themselves. About half of Hispanic adults say they most often describe themselves by their family’s country of origin or heritage, using terms such as Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican or Salvadoran, while another 39% most often describe themselves as “Hispanic” or “Latino,” the pan-ethnic terms used most often to describe this group in the U.S.

Meanwhile, 14% say they most often call themselves American, according to a national Pew Research Center survey of Hispanic adults conducted in December 2019.

The use of these terms varies across immigrant generations and reflects their diverse experiences . More than half (56%) of foreign-born Latinos most often use the name of their origin country to describe themselves, a share that falls to 39% among the U.S.-born adult children of immigrant parents (i.e., the second generation) and 33% among third- or higher-generation Latinos.

For this analysis of what Hispanics think is important to their identity, we surveyed 3,030 U.S. Hispanic adults in December 2019 as part of Pew Research Center’s 2019 National Survey of Latinos. The sample includes 2,094 Hispanic adults who were members of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. It also includes an oversample of 936 respondents from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel, another online survey panel also recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Recruiting panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling), or in this case the whole U.S. Hispanic population.

To further ensure that this survey reflects a balanced cross-section of the nation’s Hispanic adults, the data is weighted to match the U.S. Hispanic adult population by gender, nativity, Hispanic origin group, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

For the purposes of this report, references to foreign-born Hispanics include those born in Puerto Rico. Individuals born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens by birth. The survey was conducted in both English and Spanish.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology .

Meanwhile, the share who say they most often use the term “American” to describe themselves rises from 4% among immigrant Latinos to 22% among the second generation and 33% among third- or higher-generation Latinos. (Only 3% of Hispanic adults use the recent gender-neutral pan-ethnic term Latinx to describe themselves. In general, the more traditional terms Hispanic or Latino are preferred to Latinx to refer to the ethnic group.)

The U.S. Hispanic population reached 60.6 million in 2019. About one-third (36%) of Hispanics are immigrants, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. Another third of Hispanics are second generation (34%) – they are U.S. born with at least one immigrant parent. The remaining 30% of Hispanics belong to the third or higher generations, that is, they are U.S. born to U.S.-born parents.

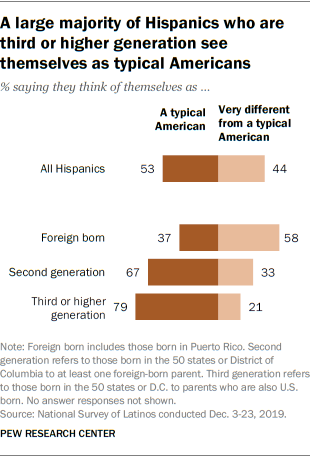

The December 2019 survey also finds U.S. Hispanics are divided on how much of a common identity they share with other Americans, though views vary widely by immigrant generation. About half (53%) consider themselves to be a typical American, while 44% say they are very different from a typical American. By contrast, only 37% of immigrant Hispanics consider themselves a typical American. This share rises to 67% among second-generation Hispanics and to 79% among third-or-higher-generation Hispanics – views that partially reflect their birth in the U.S. and their experiences as lifelong residents of this country.

Speaking Spanish seen as a key part of Hispanic identity

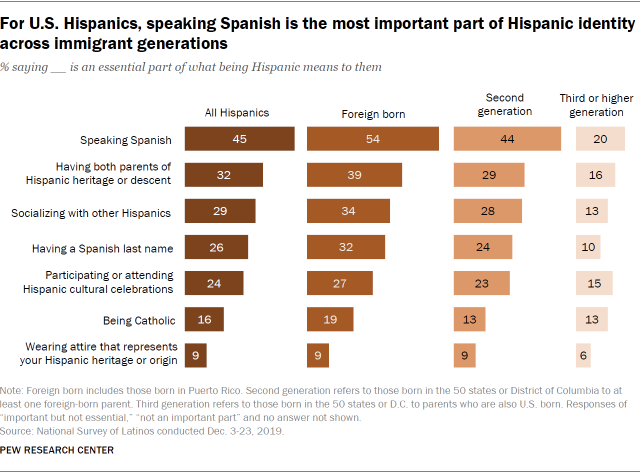

What it means to be Hispanic can vary across the group. Hispanics most often say speaking Spanish is an essential part of what being Hispanic means to them, with 45% saying so. Other top elements considered to be part of Hispanic identity include having both parents of Hispanic ancestry (32%) and socializing with other Hispanics (29%). Meanwhile, about a quarter say having a Spanish last name (26%) or participating in or attending Hispanic cultural celebrations (24%) are an essential part of Hispanic identity. Lower shares say being Catholic (16%) is an essential part of Hispanic identity. (A declining share of U.S. Hispanic adults say they are Catholic .) Just 9% say wearing attire that represents their Hispanic origin is essential to Hispanic identity.

The importance of most of these elements to Hispanic identity decreases across generations. For example, 54% of foreign-born Hispanics say speaking Spanish is an essential part of what being Hispanic means to them, compared with 44% of second-generation Hispanics and 20% of third- or higher-generation Hispanics.

Most Latinos feel at least somewhat connected to a broader Hispanic community in the U.S.

For U.S. Latinos, the question of identity is complex due to the group’s diverse cultural traditions and countries of origin. Asked to choose between two statements, Latinos say their group has many different cultures rather than one common culture by more than three-to-one (77% vs. 21%). There are virtually no differences on this question by immigrant generation among Latinos.

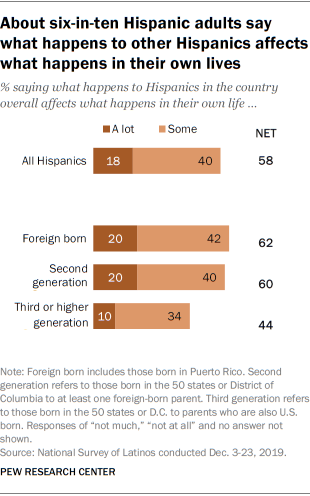

Few Hispanics report a strong sense of connectedness with other Hispanics, with only 18% saying what happens to other Hispanics in the U.S. impacts them a lot and another 40% saying it impacts them some. Immigrant Hispanics (62%) are as likely as those in the second generation (60%) to express a sense of linked fate with other Hispanics. This share decreases to 44% among the third or higher generation.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology .

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Who is Hispanic?

Majority of latinos say skin color impacts opportunity in america and shapes daily life, rising share of lawmakers – but few republicans – are using the term latinx on social media, about one-in-four u.s. hispanics have heard of latinx, but just 3% use it, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

Error message

“what does being hispanic mean to you”.

Members of the Hispanic Business Student Association share personal thoughts on their heritage and how it informs who they are and how they lead.

October 01, 2020

The Hispanic Business Student Association is a community of students interested in the cultural and professional issues that affect the Latino community. | Illustrations by Laura Pichardo

“For me, being Hispanic means standing on our ancestors’ shoulders to transform spaces not created for us and witnessing my parents’ sacrifices in pursuit of a better life — all while indulging in Mariachi music,” says Valeria Martinez, MBA ’21.

Hispanic Heritage Month begins each year on September 15 — the anniversary of independence for Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. Mexico and Chile celebrate their independence days on September 16 and September 18. To mark this year’s celebration, members of Stanford GSB’s Hispanic Business Student Association answer the question, “What does being Hispanic mean to you?”

— Jenny Luna

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom .

Explore More

New research fund promotes responsible leadership for the next century.

Stanford Alum, Business School Dean Jonathan Levin Named Stanford President

Habitat For Humanity CEO Jonathan Reckford Will Give Commencement Address

MBA Program The Stanford MBA Program is a full-time, two-year general management program that helps you develop your vision and the skills to achieve it.

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro