Writing Therapy: How to Write and Journal Therapeutically

Of course, the answer to that question will be “yes” for everyone!

We all fall on hard times, and we all struggle to get back to our equilibrium.

For some, getting back to equilibrium can involve seeing a therapist. For others, it could be starting a new job or moving to a new place. For some of the more literary-minded or creative folks, getting better can begin with art.

There are many ways to incorporate art into spiritual healing and emotional growth, including drawing, painting, listening to music, or dancing. These methods can be great for artistic people, but there are also creative and expressive ways to dig yourself out of a rut that don’t require any special artistic talents.

One such method is writing therapy. You don’t need to be a prolific writer, or even a writer at all, to benefit from writing therapy. All you need is a piece of paper, a pen, and the motivation to write.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values and self-compassion and give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students or employees.

This Article Contains:

- What Is Writing Therapy?

Benefits of Writing Therapy

How to: journaling for therapy, writing ideas & journal prompts, exercises and ideas to help you get started, a take-home message, what is writing therapy.

Writing therapy, also known as journal therapy, is exactly what it sounds like: writing (often in a journal) for therapeutic benefits.

Writing therapy is a low-cost, easily accessible, and versatile form of therapy . It can be done individually, with just a person and a pen, or guided by a mental health professional. It can also be practiced in a group, with group discussions focusing on writing. It can even be added as a supplement to another form of therapy.

Whatever the format, writing therapy can help the individual propel their personal growth , practice creative expression, and feel a sense of empowerment and control over their life (Adams, n.d.).

It’s easy to see the potential of therapeutic writing. After all, poets and storytellers throughout the ages have captured and described the cathartic experience of putting pen to paper. Great literature from such poets and storytellers makes it tempting to believe that powerful healing and personal growth are but a few moments of scribbling away.

However, while writing therapy seems as simple as writing in a journal , there’s a little more to it.

Writing therapy differs from simply keeping a journal or diary in three major ways (Farooqui, 2016):

- Writing in a diary or journal is usually free-form, where the writer jots down whatever pops into their head. Therapeutic writing is typically more directed and often based on specific prompts or exercises guided by a professional.

- Writing in a diary or journal may focus on recording events as they occur, while writing therapy is often focused on more meta-analytical processes: thinking about, interacting with, and analyzing the events, thoughts, and feelings that the writer writes down.

- Keeping a diary or journal is an inherently personal and individual experience, while journal therapy is generally led by a licensed mental health professional.

While the process of writing therapy differs from simple journaling in these three main ways, there is also another big difference between the two practices in terms of outcomes.

These are certainly not trivial benefits, but the potential benefits of writing therapy reach further and deeper than simply writing in a diary.

For individuals who have experienced a traumatic or extremely stressful event, expressive writing guided purposefully toward specific topics can have a significant healing effect. In fact, participants in a study who wrote about their most traumatic experiences for 15 minutes, four days in a row, experienced better health outcomes up to four months than those who were instructed to write about neutral topics (Baikie & Wilhelm, 2005).

Another study tested the same writing exercise on over 100 asthma and rheumatoid arthritis patients, with similar results. The participants who wrote about the most stressful event of their lives experienced better health evaluations related to their illness than the control group, who wrote about emotionally neutral topics (Smyth et al., 1999).

Expressive writing may even improve immune system functioning, although the writing practice may need to be sustained for the health benefits to continue (Murray, 2002).

In addition to these more concrete benefits, regular therapeutic writing can help the writer find meaning in their experiences, view things from a new perspective, and see the silver linings in their most stressful or negative experiences (Murray, 2002). It can also lead to important insights about yourself and your environment that may be difficult to determine without focused writing (Tartakovsky, 2015).

Overall, writing therapy has proven effective for different conditions and mental illnesses, including (Farooqui, 2016):

- Post-traumatic stress

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

- Grief and loss

- Chronic illness issues

- Substance abuse

- Eating disorders

- Interpersonal relationship issues

- Communication skill issues

- Low self-esteem

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

There are many ways to begin writing for therapeutic purposes.

If you are working with a mental health professional, they may provide you with directions to begin journaling for therapy.

While true writing therapy would be conducted with the help of a licensed mental health professional, you may be interested in trying the practice on your own to explore some of the potential benefits to your wellbeing. If so, here there are some good tips to get you started.

First, think about how to set yourself up for success:

- Use whichever format works best for you, whether it’s a classic journal, a cheap notebook, an online journaling program, or a blog.

- If it makes you more interested in writing, decorate or personalize your journal/notebook/blog.

- Set a goal to write for a certain amount of time each day.

- Decide ahead of time when and/or where you will write each day.

- Consider what makes you want to write in the first place. This could be your first entry in your journal.

Next, follow the five steps to WRITE (Adams, n.d.):

- W – What do you want to write about? Name it.

- R – Review or reflect on your topic. Close your eyes, take deep breaths, and focus.

- I – Investigate your thoughts and feelings. Just start writing and keep writing.

- T – Time yourself. Write for five to 15 minutes straight.

- E – Exit “smart” by re-reading what you’ve written and reflecting on it with one or two sentences

Finally, keep the following in mind while you are journaling (Howes, 2011):

- It’s okay to write only a few words, and it’s okay to write several pages. Write at your own pace.

- Don’t worry about what to write about. Just focus on taking the time to write and giving it your full attention.

- Don’t worry about how well you write. The important thing is to write down what makes sense and comes naturally to you.

- Remember that no-one else needs to read what you’ve written. This will help you write authentically and avoid “putting on a show.”

It might be difficult to get started, but the first step is always the hardest! Once you’ve started journaling, try one of the following ideas or prompts to keep yourself engaged.

Here are five writing exercises designed for dealing with pain (Abundance No Limits, n.d.):

- Write a letter to yourself

- Write letters to others

- Write a poem

- Free write (just write everything and anything that comes to mind)

- Mind map (draw mind maps with your main problem in the middle and branches representing different aspects of your problem)

If those ideas don’t get your juices flowing, try these prompts (Farooqui, 2016):

- Journal with photographs – Choose a personal photo and use your journal to answer questions like “What do you feel when you look at these photos?” and “What do you want to say to the people, places, or things in these photos?”

- Timed journal entries – Decide on a topic and set a timer for 10 or 15 minutes to write continuously.

- Sentence stems – These prompts are the beginnings of sentences that encourage meaningful writing, such as “The thing I am most worried about is…” “I have trouble sleeping when…” and “My happiest memory is…”

- List of 100 – These ideas encourage the writer to create lists of 100 based on prompts like “100 things that make me sad” “100 reasons to wake up in the morning,” and “100 things I love.”

Tartakovsky (2014) provides a handy list of 30 prompts, including:

- My favorite way to spend the day is…

- If I could talk to my teenage self, the one thing I would say is…

- Make a list of 30 things that make you smile.

- The words I’d like to live by are…

- I really wish others knew this about me…

- What always brings tears to your eyes?

- Using 10 words, describe yourself.

- Write a list of questions to which you urgently need answers.

If you’re still on the lookout for more prompts, try the lists outlined here .

6 Ways to process your feelings in writing – Therapy in a Nutshell

As great as the benefits of therapeutic journaling sound, it can be difficult to get started. After all, it can be a challenge to start even the most basic of good habits!

If you’re wondering how to begin, read on for some tips and exercises to help you start your regular writing habit (Hills, n.d.).

- Start writing about where you are in your life at this moment.

- For five to 10 minutes just start writing in a “stream of consciousness.”

- Start a dialogue with your inner child by writing in your nondominant hand.

- Cultivate an attitude of gratitude by maintaining a daily list of things you appreciate, including uplifting quotes .

- Start a journal of self-portraits.

- Keep a nature diary to connect with the natural world.

- Maintain a log of successes.

- Keep a log or playlist of your favorite songs.

- If there’s something you are struggling with or an event that’s disturbing you, write about it in the third person.

If you’re still having a tough time getting started, consider trying a “mind dump.” This is a quick exercise that can help you get a jump start on therapeutic writing.

Researcher and writer Gillie Bolton suggests simply writing for six minutes (Pollard, 2002). Don’t pay attention to grammar, spelling, style, syntax, or fixing typos – just write. Once you have “dumped,” you can focus on a theme. The theme should be something concrete, like something from your childhood with personal value.

This exercise can help you ensure that your therapeutic journal entries go deeper than superficial diary or journal entries.

More prompts, exercises, and ideas to help you get started can be found by following this link .

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

In this piece, we went over what writing therapy is, how to do it, and how it can benefit you and/or your clients. I hope you learned something new from this piece, and I hope you will keep writing therapy in mind as a potential exercise.

Have you ever tried writing therapy? Would you try writing therapy? How do you think it would benefit you? Let us know your thoughts in the comments!

Thanks for reading, and happy writing!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Abundance No limits. (n.d.). 5 Writing therapy exercises that can ease your pain . Author. Retrieved from https://www.abundancenolimits.com/writing-therapy-exercises/.

- Adams, K. (n.d.). It’s easy to W.R.I.T.E . Center for Journal Therapy . Retrieved from https://journaltherapy.com/journal-cafe-3/journal-course/

- Baikie, K. A., & Wilhelm, K. (2005). Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 11(5) , 338-346.

- Farooqui, A. Z. (2016). Journal therapy . Good Therapy . Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/journal-therapy

- Hills, L. (n.d.). 10 journaling tips to help you heal, grow, and thrive . Tiny Buddha . Retrieved from https://tinybuddha.com/blog/10-journaling-tips-to-help-you-heal-grow-and-thrive/

- Howes, R. (2011, January 26). Journaling in therapy . Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/in-therapy/201101/journaling-in-therapy.

- Murray, B. (2002). Writing to heal. Monitor, 33(6), 54. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/monitor/jun02/writing.aspx

- Pollard, J. (2002). As easy as ABC . The Guardian . Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2002/jul/28/shopping

- Smyth, J. M., Stone, A. A., Hurewitz, A., & Kaell, A. (1999). Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 281 , 1304-1309.

- Tartakovsky, M. (2014). 30 journaling prompts for self-reflection and self-discovery . Psych Central . Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2014/09/27/30-journaling-prompts-for-self-reflection-and-self-discovery/

- Tartakovsky, M. (2015). The power of writing: 3 types of therapeutic writing . Psych Central . Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2015/01/19/the-power-of-writing-3-types-of-therapeutic-writing/

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Hello, Such an interesting article, thank you very much. I was wondering if there was a particular strategy in which writing down questions produced answers. I started doing just that: writing down doubts and questions, and I found that answers just came. It was like talking through the issues with someone else. Is there any research on that? Is this a known strategy?

Hi Michael,

That’s amazing that you’re finding answers are ‘arising’ for you in your writing. In meditative and mindfulness practices, this is often referred to as intuition, which points to a form of intelligence that goes beyond rationality and cognition. This is a fairly new area of research, but has been well-recognized by Eastern traditions for centuries. See here for a book chapter review: https://doi.org/10.4337/9780857936370.00029

As you’ve discovered, journaling can be incredibly valuable to put you in touch with this intuitive form of knowing in which solutions just come to you.

This also reminds me of something known as the rubber ducking technique, which programmers use to solve problems and debug code: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubber_duck_debugging

Anyway, hope that offers some food for thought!

– Nicole | Community Manager

I have never tried writing therapy, but I intend to. Its so much better than seeing the psychiatrist for my behavior issues, which nobody has even identified yet.

Hi great article, just wondering when it was originally posted as I wish to cite some of the text in my essay Many thanks

Glad you enjoyed the post. It was published on the 26th of October, 2017 🙂

Hope this helps!

Hi Courtney

I know you posted this blog a while ago but I’ve just found it and loved it. It articulated so clearly the benefits of writing therapy. One question – is there any research on whether it’s better to use pen and paper or Ian using a PC/typing just as good. I can write much faster and more fluently when I use a keyboard but wonder whether there is a benefit from the physical act of writing writing with a pen. Thanks.

Great question. The evidence isn’t entirely clear on this, but there’s a little work suggesting that writing by hand forces the mind to slow down and reflect more deeply on what’s being written (see this article ). Further, the process of writing uses parts of the brain involved in emotion, which may make writing by hand more effective for exploring your emotional experiences.

However, when it comes to writing therapy, the factor of personal preference seems critical! The issue of speed can be frustrating if your thoughts tend to come quickly. If you feel writing by hand introduces more frustration than benefits, that may be a sign to keep a digital journal instead.

Hope that helps!

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Holistic Therapy: Healing Mind, Body, and Spirit

The term “holistic” in health care can be dated back to Hippocrates over 2,500 years ago (Relman, 1979). Hippocrates highlighted the importance of viewing individuals [...]

Trauma-Informed Therapy Explained (& 9 Techniques)

Trauma varies significantly in its effect on individuals. While some people may quickly recover from an adverse event, others might find their coping abilities profoundly [...]

Recreational Therapy Explained: 6 Degrees & Programs

Let’s face it, on a scale of hot or not, attending therapy doesn’t make any client jump with excitement. But what if that can be [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (47)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (27)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (36)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (48)

- Resilience & Coping (34)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

join the list

Join 4,000+ ambitious women ready to redefine success and put an end to toxic hustle culture. , get on the list.

Sign up to get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can go from "busy" to "present" and tap into a slower life that prioritizes your energy and peace

Ultimate Guide to Creative Writing Therapy (with Writing Therapy Prompts)

March 22, 2023

I believe that taking care of yourself should always come first. So, my job is to help you create a slow and mindful life that aligns with your values and goals so you can finally go from a state of constantly doing to peacefully being.

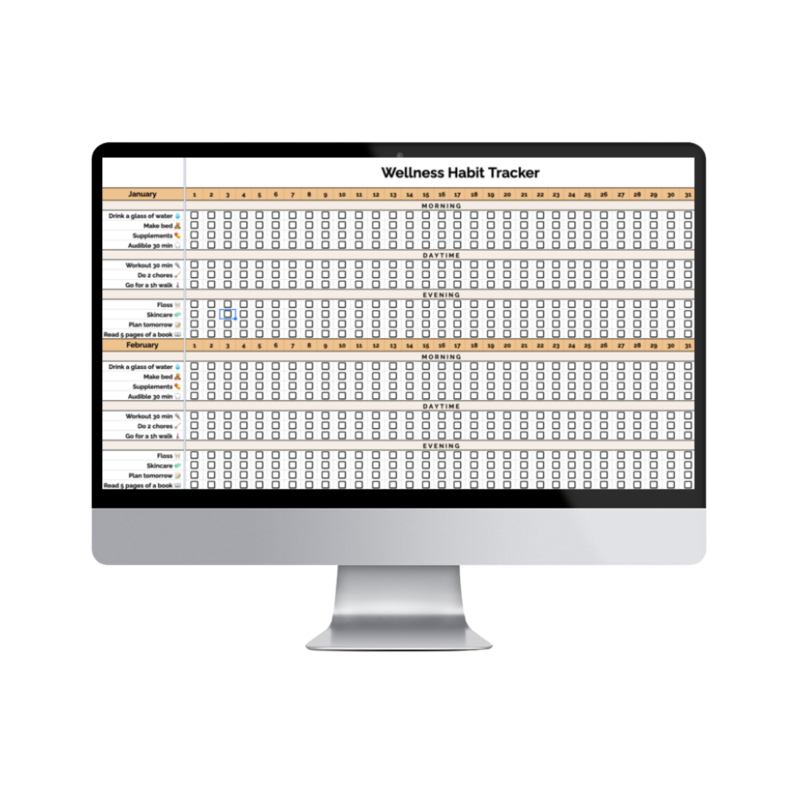

5-Minute Wellness Habit Tracker That *Actually* Works

This super customizable and in-depth wellness habit tracker is specifically designed to help you protect your time, have blissful boundaries, achieve your goals, and be extra productive every day so you can finally go from overwhelmed to organized in just 5 minutes/day.

join the movement

Sign up to get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can tap into a slower life and go from constantly doing to peacefully being.

Creative writing therapy, or therapeutic writing is a form of therapeutic intervention that uses writing as the tool to explore and express your thoughts, feelings and emotions. It’s also known as journal therapy – and it’s essentially the art of writing in a journal to heal yourself.

Writing therapy can be a useful tool for people who struggle with mental health, have experienced trauma or grief, or are simply looking for a creative outlet to process their thoughts and feelings. Today we’re going to explore what creative writing therapy is, how it works, and the potential benefits of writing therapy. We’ll also share writing therapy prompts to help you get started and explore writing therapy today.

Please keep in mind that there is no true substitute for seeing a licensed therapist, and if you feel like you could benefit from talking to someone and getting help with what you’re going through – you’re not alone! There are tons of incredible therapists out there to help you. Here at Made with Lemons we’re big advocates for therapy and if you’d like a more inside scoop to our own journey with therapy, join On Your Terms . It’s a wellness newsletter that shares a more inside look to our own wellness journey as well as tools to help you along yours. Learn more about On Your Terms here.

Get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can go from “busy” to “present” and show up as your best self.

What is Creative Writing Therapy?

Writing therapy, also known as therapeutic writing, is a form of creative and expressive therapy that involves writing about your personal experiences, thoughts and feelings. It can take many forms, including journaling, poetry, creative writing, letter writing, or memoirs. Writing therapy can be done individually or in a group setting. It can also be facilitated by a therapist, counselor or writing coach.

The purpose of creative writing therapy is to help you express and process your emotions in a safe and supportive environment. It’s helpful to be able to write out your thoughts and feelings that might be hard to articulate in other ways.

You might also see therapeutic writing used to help explore issues that are difficult to discuss in traditionally talking therapy sessions. And when your therapist invites you to try writing therapy, it’s also used in conjunction with other forms of therapy, such as trauma-focused therapy, to enhance its effectiveness.

An example of creative writing therapy could be writing a letter to a person who hurt you, and then shredding or burning the letter to release some of the hurt and anger.

How Does Therapeutic Writing Work?

Writing therapy works by allowing individuals to express their thoughts and feelings in a way that is both private and creative. The act of writing can help you organize your thoughts and gain clarity on your emotions. Writing can also be a way to release pent-up emotions and relieve stress.

For example, if you’re feeling stressed after a long day of work, taking a few moments to write down what’s stressing you out and allowing yourself to let it go, can help you have a calm and more relaxing evening.

Writing therapy should be a truly non judgemental space. It’s a time to write without worrying about grammar, punctuation, or spelling. The goal here is to let words flow freely, without judgment or criticism. Creative writing therapy sessions can be structured or unstructured, and sometimes it’s helpful to use prompts or exercises to help you get started. (i.e. what in your life is bringing you the most anxiety, or writing a letter to your friend to express ___________ hurt you when they said that.)

Oftentimes we find it easier to write about our hurt, our pain and the experiences that caused that, as opposed to opening up to talk about those things. In this way, writing can be a way to explore and process complex emotions such as grief or anger in a safe and supportive environment, where no one can get hurt further by what’s being felt and expressed.

Potential Benefits of Writing Therapy

Now let’s talk about some of the benefits of therapeutic writing.

Improved mental health

Writing therapy can be a tool that helps you manage symptoms of depression, anxiety and other mental health conditions. You can use journaling therapy to express and process difficult emotions, which over time can lead to improved mental regulation and a better sense of control over your thoughts and feelings.

Increased self-awareness

Creative writing therapy can help you gain a better insight into your thoughts and behaviors. By reflecting on your experiences through writing, you can start to identify patterns and gain an understanding of yourself.

Stress relief

Therapeutic writing can be a way to relieve stress and reduce anxiety. Writing is often cathartic, allowing you to release pent-up emotions and start to feel relief from things that would otherwise feel overwhelming.

Improved communication skills

Journal therapy can also help you improve your overall communication skills. When you practice expressing yourself through writing, you can develop more confidence to communicate more effectively in both your personal and professional relationships. In essence, writing your feelings can help you communicate them better when needed.

Increased creativity

Lastly, creative writing therapy can also be a way to tap into your creativity and imagination. We talk a lot about your inner child around here, and journal therapy can be another helpful way you can interact with your inner child. Through writing you can explore new ideas and perspectives, leading to your own personal growth.

How to try Creative Writing Therapy Today

Now let’s talk about how you can try therapeutic writing for yourself today. These tips are going to help you get started with writing therapy from home, as a personal activity to help heal yourself.

Set aside dedicated time for writing therapy

Like most self improvement and self care techniques, it helps to set aside a dedicated time to write regularly. We know this can be a challenging task, especially if you’re struggling with mental health issues or challenges in your life. A good place to start is to set aside a few minutes each evening to write and decompress from your day. It can be just 2 minutes before bed. Remember, therapeutic writing is a non judgemental activity, so the amount of time you dedicate isn’t important, it’s just important to show up for yourself.

Find a quiet and comfortable space

Find a place that’s quiet and comfortable, and where you can write without interruptions. Some people find it helpful to create a writing ritual, such as lighting a candle or playing soft music to create a sense of calm and focus. Find what works for you, in a space where you can be alone for a few minutes.

Choose a writing therapy prompt or topic

At the end of this guide we’re going to share writing therapy prompts to help you explore creative writing therapy and give you a starting point. You can also talk to your therapist to get prompts, or find some online. Prompts can be general, such as “write about what makes you grateful or happy”, while others can be more specific, such as “write about a time that you felt overwhelmed.”

Write freely and without judgment

The most important thing about writing therapy is to write freely, without judging yourself. Allow yourself to write without worrying about grammar, punctuation or spelling. Don’t put a time limit on your writing, or feel like you have to write a certain number of words or pages. The goal here is to allow your thoughts and emotions to flow freely without any judgment at all.

Write honestly and openly

Along with being judgment free, it’s also so important that you write honestly and openly. Writing therapy is a space for honesty and openness. This space is created for you to share your thoughts and emotions, even if they're difficult or uncomfortable to confront. Just be open to exploring them, and remember that you don’t have to share this with anyone, so it’s a space where you can be fully honest with yourself.

Reflect on your writing

After writing, you can take a few moments to reflect on what you have written. It might even be helpful to come back to what you have written at another time, when you have a clear head or have left the emotions behind. This can help you consider the emotions and patterns that you have expressed. Doing this reflection can help you gain more insight into your thinking patterns and emotions for future sessions.

Consider sharing your writing with a therapist or counselor

Lastly, consider sharing your writing with a therapist or counselor. They can help you process emotions and gain a deeper understanding of yourself. Sharing your writing can also help you feel less alone in your struggles and provide important validation for your experiences.

20 Writing Therapy Prompts

- When do I feel the most like myself?

- How do I feel at this moment?

- What do I need more of in my life?

- What do I look forward to every day?

- What is a lesson that I had to learn recently?

- Based on my daily routine, where do I see myself in 5 years?

- What don’t I regret?

- What would make me happy right now?

- What has been the hardest thing to forgive myself for?

- What’s bothering me? And why?

- What do I love about myself?

- What are my priorities right now?

- What does my ideal day look like?

- What does my ideal morning look like? Evening?

- Make a list of 30 things that make you smile

- Make a gratitude list

- The words I’d like to live by are…

- I really wish others knew this about me…

- What always brings tears to my eyes?

- What do I need to get off my chest today?

Creative writing therapy can be a powerful tool for exploring and processing thoughts and emotions. When you set aside a dedicated time to write, and create a safe and supportive space for yourself, you can gain insight into your emotions and develop better tools to manage them. With practice and commitment, writing therapy can become a habit for your self care routine.

If you’d like to build the habit of writing therapy in your own life, then we’d like to invite you to download our habit tracker. It’s super easy to use, beautifully designed and completely free. All you need is a google account to access it. Grab a copy of our habit tracker here.

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment

How to Create the Perfect Anti “That Girl” Morning Routine in Less Than One Hour »

« Revamp Your Life This Spring: The Ultimate Spring Reset Guide

Previous Post

back to blog home

Summer of Self-Care (60 Solo Date Ideas for Summer 2023)

How to Live a Sober Life (70 Ways to Practice Sober Self-Care)

A Complete Guide to Mushroom Microdosing

Self Love Ideas Based on Your Love Language

Glowy Skincare Routine: How to Get Naturally Glowing Skin From Home

What vitamins should I be taking to optimize health and increase energy?

so hot right now

This super customizable and in-depth wellness habit tracker is designed to help you protect your time, achieve your goals, and be more productive every day so you can finally go from overwhelmed to organized in just 5 minutes.

Wellness Habit Tracker

Ready to success and put an end to toxic hustle culture?

Get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can go from "busy" to "present" and show up as your best self in life and business in this weekly newsletter.

Do you sleep 7-8+ hours but feel exhausted? Does resting feel selfish and unproductive? Get your free download to find out about the 7 types of rest and why you'll burnout without it.

7 Types of Rest You Need

FREE DOWNLOAD

3 Steps to Avoid Burnout & Create More Intentionality in Your Life and Business

free class!

Come say hi on the 'gram!

apply for 1:1 coaching

GET my newsletter

© MADE WITH LEMONS 2020- 2023 | Privacy Policy | Terms & CONDITIONS | Design by Tonic

London-based multi-passionate Lifestyle designer for busy female entrepreneurs, lover of Golden Retrievers, skin care obsessed, & proud plant mom.

Learn from me

@madewithlemonsco

Your Information is 100% Secure And Will Never Be Shared With Anyone. You can unsubscribe at any time. By submitting this form you confirm you have read our privacy policy and you accept our terms and conditions

Join the anti-hustle movement!

Your Information is 100% Secure And Will Never Be Shared With Anyone. You can unsubscribe at any time.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Writing Can Help Us Heal from Trauma

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo

Three prompts to get started.

Why does a writing intervention work? While it may seem counterintuitive that writing about negative experiences has a positive effect, some have posited that narrating the story of a past negative event or an ongoing anxiety “frees up” cognitive resources. Research suggests that trauma damages brain tissue, but that when people translate their emotional experience into words, they may be changing the way it is organized in the brain. This matters, both personally and professionally. In a moment still permeated with epic stress and loss, we need to call in all possible supports. So, what does this look like in practice, and how can you put this powerful tool into effect? The author offers three practices, with prompts, to get you started.

Even as we inoculate our bodies and seemingly move out of the pandemic, psychologically we are still moving through it. We owe it to ourselves — and our coworkers — to make space for processing this individual and collective trauma. A recent op-ed in the New York Times Sunday Review affirms what I, as a writer and professor of writing, have witnessed repeatedly, up close: expressive writing can heal us.

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo is an author , TEDx speaker, and founder of Bold Voice Collaborative , an organization fostering growth, resilience, and community through storytelling for individuals and organizations. An adjunct faculty member at DePaul University’s College of Communication, her writing has appeared in venues including The Washington Post, The Guardian, and CNN.com.

Partner Center

What Is Creative Writing Therapy

Table of Contents

What is creative writing therapy?

Creative writing therapy, or therapeutic writing is a form of therapeutic intervention that uses writing as the tool to explore and express your thoughts, feelings and emotions. It’s also known as journal therapy – and it’s essentially the art of writing in a journal to heal yourself.

How far could creative writing act as therapy?

Whatever the format, writing therapy can help the individual propel their personal growth, practice creative expression, and feel a sense of empowerment and control over their life (Adams, n.d.). It’s easy to see the potential of therapeutic writing.

What is creative writing training?

Studying creative writing will help you enhance your general linguistic skills and hone your unique writing voice. You’ll learn new ways to express yourself clearly and creatively in various written forms. Those enhanced communication skills can be a powerful asset in the business world as well as your personal life.

What are the different types of writing therapy?

It may be supervised by a mental health professional or even occur with little or no direct influence from a counselor. There are several types of writing therapy, including, but not limited to narrative therapy, interactive journaling, focused writing, and songwriting.

What is an example of writing therapy?

Compose a letter. Imagine this person has written to you and asked you: “How are you doing, really?” Another exercise is to “write to someone with whom you have ‘unfinished business’ without sending it.” The goal is for you to gain a clearer understanding of your own thoughts and feelings about the person, she said.

What is an example of creative therapy?

Creative therapy uses art forms — such as dance, drawing, or music — to help treat certain conditions. Trained therapists can administer creative therapy to help people experiencing a range of mental, emotional, and physical issues. Creative therapy does not require a person to have any sort of artistic ability.

What is the purpose of writing therapy?

Writing therapy is a form of expressive therapy that uses the act of writing and processing the written word for therapeutic purposes. Writing therapy posits that writing one’s feelings gradually eases feelings of emotional trauma.

How do you start therapeutic writing?

- Create a routine of your journaling habits. Many people begin journaling with the best intentions, but find that the habit is difficult to establish. …

- Find somewhere quiet to write. …

- Decide on the topic you want to explore. …

- Start writing! …

- Repeat. …

- Sources and references:

Is creative writing good for your brain?

CREATIVE WRITING STRENGTHENS OUR MEMORY: It can help contextualise ideas and make them more manageable in our brains. The written word can be more trustworthy than our own thinking. Even a small note on a piece of paper might spark our recollection of an unfinished task.

What are the 4 types of creative writing?

The primary four forms of creative writing are fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and screenwriting. Writers will use a mixture of creative elements and techniques to tell a story or evoke feelings in the reader. The main elements used include: Character development.

Can I teach myself creative writing?

Many beginners can feel intimidated or embarrassed by their creative work and where their imagination takes them. Through freewriting, creative writing exercises, writing prompts, and practice, you can improve your own writing skills to become a better writer.

What skill is creative writing?

Creative writing is an art. And like everything artistic, it requires imagination. Whether it is a poem, story, blog, or any other form of writing, the writer must use imagination and expression to evoke emotion from the readers.

Who created writing therapy?

James Pennebaker was the first researcher that studied therapeutic effects of writing. He developed a method called expressive writing, which consists of putting feelings and thoughts into written words in order to cope with traumatic events or situations that yield distress (Pennebaker & Chung, 2007).

What kind of writing do therapists do?

Most of those I spoke to said they jot down information about symptoms, demographics, treatment history, and personal history during that first meeting so as to get a sense of both what potential issues they’ll be tackling and who the patient is more generally.

What are the 6 writing techniques?

The Six Traits of writing are Voice, Ideas, Presentation, Conventions, Organization, Word Choice, and Sentence Fluency. It creates a common vocabulary and guidelines for teachers to use with students so that they become familiar with the terms used in writing. It develops consistency from grade level to grade level.

What are the benefits of creative writing in therapy?

CREATIVE WRITING HELPS YOU TO EXPRESS YOUR FEELINGS: Some may also use creative writing as a way of connecting with others. Sharing tales and perspectives while also learning from, and supporting one another. Writing about difficult situations can help us release our feelings in a healthy way.

What is creative writing and examples?

What is an example of creative writing? One example of creative writing is fiction writing. Fiction includes traditional novels, short stories, and graphic novels. By definition, fiction is a story that is not true, although it can be realistic and include real places and facts.

What is creative writing in simple terms?

Creative writing, a form of artistic expression, draws on the imagination to convey meaning through the use of imagery, narrative, and drama. This is in contrast to analytic or pragmatic forms of writing. This genre includes poetry, fiction (novels, short stories), scripts, screenplays, and creative non-fiction.

What is creative arts therapy used for?

Creative arts therapy is a profession that uses active engagement in the arts to address mental, emotional, developmental, and behavioral disorders. Creative arts therapy uses the relationship between the patient and therapist in the context of the artistic process as a dynamic force for change.

Related Posts

Why is art journaling therapeutic, what is art journal therapy, why is art journaling important, does journaling help with mental health, what is the goal of expressive arts therapy, what is dbt art therapy, what is gestalt art therapy, what are 3 writing prompts, what are four benefits of art therapy, leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Please enter an answer in digits: nine − 6 =

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Use Writing Therapy to Release Negative Emotions and Trauma

Whether it’s lyrics or journaling—expression through writing can be cathartic

Ayana is the Associate Editor at Verywell Mind, where she aims to publish mental health content that is both engaging and of high quality.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/verywell-Ayana-Underwood1-b3c1567c2c4c4480b6eab25cabb974b1.jpg)

Yolanda Renteria, LPC, is a licensed therapist, somatic practitioner, national certified counselor, adjunct faculty professor, speaker specializing in the treatment of trauma and intergenerational trauma.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YolandaRenteria_1000x1000_tight_crop-a646e61dbc3846718c632fa4f5f9c7e1.jpg)

Verywell / Julie Bang

- What to Know About Writing Therapy

The Major Benefits of Writing Therapy

- How to Get Started With Expressive Writing

Every Friday on The Verywell Mind Podcast , host Minaa B., a licensed social worker, mental health educator, and author of "Owning Our Struggles," interviews experts, wellness advocates, and individuals with lived experiences about community care and its impact on mental health.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts / Amazon Music

Putting pen to paper feels a bit like an anomaly in a world obsessed with texting, tweeting, and sliding into people’s DMs. But let’s try something different. The next time you’re in your Notes app, give your thumbs a break and grab a pen and piece of paper instead. If you don’t have any paper handy, grab that Starbucks receipt and start writing whatever you were about to type. See how it feels.

It might feel a bit awkward at first, especially if you haven’t had to physically write anything down in a long while. But as you keep writing, you may feel really engaged with the words you’re jotting down. Tapping letters on a screen isn’t the same as drawing out each letter of every word. Writing things down will inherently bond you to the words you write. And because of that, writing becomes quite powerful for the psyche . Aside from being a feel-good activity, writing can also let us process negative emotions and trauma in what turns out to be a pretty soul-cleansing experience.

In fact, singer/songwriter and season three winner of The Voice, Cassadee Pope , seconds this. Pope, who's been in the music industry since she was 11 years old, has been pretty open about her mental health struggles—from bad breakups to the emotional impact of her parent’s divorce. Pope told Minaa B., LMSW , host of The Verywell Mind Podcast, “I needed an outlet with everything that was happening with my family. So that was really what I leaned on most, was songwriting.”

Now, you don’t have to be a gifted songwriter to reap the benefits of writing, but let's talk about why writing can be so good for your mental health.

At a Glance

Writing can be a powerful therapeutic tool. Getting your thoughts down can help you understand them and process them more effectively than keeping them all in your head. People who use writing therapy report better overall mood and fewer depressive symptoms. If you’re struggling with a mental health condition and need to vent your frustrations—consider making a journal your new BFF.

What to Know About Writing Therapy (Write This Down)

Writing therapy (aka emotional disclosure or expressive writing) is pretty much exactly what it sounds like. It involves using writing of any kind, like creative writing, freewriting, and poetry, as a therapeutic tool. Writing therapy can be especially for those who are more withdrawn or have trouble opening up to others.

Writing therapy can be so beneficial to our mental health because it’s basically a form of venting. You know how good it feels to come home after a long day of work and go on and on about how much you dislike that one coworker for a reason you can’t even put your finger on. Or when you spill all of your dating frustrations to your bestie over the phone. It’s a nice release of stress. You can release stress in a similar way when you write, too. Just pretend that piece of paper is your therapist, closest confidante, or even yourself.

No one else has to know whatever you choose to jot down (or rage-write about). Your journal or diary is your personal safe haven, and your innermost thoughts are safe on those pages.

Research shows that writing about painful experiences can even improve your immune system. Getting all of your thoughts out on paper is a big stress reliever. It’s also known that trying to suppress negative emotions can be detrimental to your overall well-being, so verbal release may only help you in the long run. Another advantage of writing therapy is that it gives your emotions and thoughts some structure. For instance, my therapist knows I love writing—especially writing poetry. So, when I was dealing with a particularly traumatic time in my life, she told me that my next few homework assignments would be to write poetry about my feelings. Because poetry is a form of creative writing, I had to really think about the diction and imagery I wanted to convey in the poems.

As a result, I really had to unpack my feelings so that my poem would paint a clear picture of what I was going through. I worked on the poem each night before bed and had it ready for my next weekly session.

The next day, I hopped online to meet with my therapist and tell her I had completed my assignment. In response, she asked me to read it aloud. What?! I quickly grew nervous since I was not expecting that. But, considering she’s never led me astray, I reluctantly recited my poem. It was an emotional experience, and my voice audibly cracked a few times, but it felt really good—euphoric, even. So when Pope says that singing her lyrics is "cathartic," I completely get it. She says her singing can be a bit “disarming” because “ I’m believing every word so intensely, and I feel them so intensely.”

So, not only does writing release some deep-seated feelings, orating them breathes life into them. There’s this particularly beautiful Chinese proverb that says: ‘I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I write and I understand.’ Once our thoughts are written down, we can see them in front of us, through this practice they become real. Then, we can dig in and unpack what it all means to us.

Other Benefits of Writing Therapy

If you’re still not convinced about the power of writing, here are some other amazing benefits of writing to take note of (pun intended):

- Lowered blood pressure

- Reduced anxiety and depression symptoms

- Improved cognition

- Increased antibody production

- Better overall mood

Ready to Get Started With Expressive Writing?—Here’s How

The great thing about writing is that it can be about anything you want. There are zero restrictions on what you can say. If you’ve had an upsetting experience or need to release some frustrations about daily stressors, try writing about it.

Pope talks about how she’s been using songwriting to get more authentic about her life as of late. In fact, she was kind enough to dish on the details about a new song of hers that’s set to release soon titled “Three of Us.” In this track, she details what it’s like being the “third wheel” when you’re in a relationship with someone who’s dealing with a substance use disorder : “It's about me, you, and the drugs.” In describing the lyrics, she says, “It's probably the most revealing song I've ever released.”

Now, if you’ve already got an experience you want to write about, feel free to get started when you’re alone and in a private space. But if you don’t know where to start, here are some prompts to start flexing your writing muscles.

Writing Prompts to Help You Get to Know Yourself Better

When you’re ready, get something to write with and a blank sheet of paper. Here are some prompts you can use to get started:

- What does the perfect day look like for you? Think about the activities you’d engage in and who you would be spending your time with. Try engaging your five senses to dive deep into your imagination.

- Write a story about the last time you were embarrassed. This time, reframe the experience into a positive one where you learn something new about yourself.

- Think about the best piece of advice you've ever received from someone. How has it helped to shape your life?

- Write a song or a poem about what it’s like to eat your favorite dessert. Consider the flavors, textures, and how you feel when you eat this specific treat. Where are you eating it? Did someone special make it for you, or did you make it yourself?

- What does self-love really mean to you? Who taught you what loving yourself looks like? What have you learned to embrace about yourself?

- If you’ve experienced a painful event, free-write about it. Don’t worry about grammar, spelling, or legibility—just write whatever comes to mind. You can even draw if that helps.

These writing prompts should get you more comfortable with expressing your feelings. Once you make sense of your own experiences, you might be ready to share them with friends, significant others, and other people you trust. If you have a therapist or plan to start therapy, you’ll already have some material to share that you can explore in the session.

When you connect through storytelling, you begin to strengthen your support network. Pope shared how much she leaned on her friends after a bad breakup. “ If you have community, lean into it and don't be afraid that someone's gonna judge you if you made a mistake or a bad decision, a poor decision, don't be afraid of that. It's so much more healthy to just let it out,” she says.

Pope also cautions that doing this can also reveal the people who accept you just as you are—flaws included: “ If somebody judges you or tries to make you feel bad about it, then OK, great. That one person is not a safe space for you.”

What This Means For You

If you’re uncomfortable opening up to your friends this way, that’s perfectly fine. Never feel pressured to share some uncomfortable thoughts or experiences. You can keep them to yourself in your journal or reserve them all for your therapist.

Writing is a good place to start when you want to better understand who you are and how your experiences have affected you. If you’re struggling with processing your emotions and feel that you need someone to talk to, consider seeing a mental health professional.

Mugerwa S, Holden JD. Writing therapy: a new tool for general practice? . Br J Gen Pract . 2012;62(605):661-663. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X659457

American Psychological Association. Writing to heal .

Krpan KM, Kross E, Berman MG, Deldin PJ, Askren MK, Jonides J. An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: the benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder . J Affect Disord . 2013;150(3):1148-1151. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.065

By Ayana Underwood Ayana is the Associate Editor at Verywell Mind, where she aims to publish mental health content that is both engaging and of high quality.

Submit your details to get your report

Dummy Text. Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) numbers among the greatest philosophers.

Email Address

Remember me

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Writing therapy: types, benefits, and effectiveness, thc editorial team august 7, 2021.

In this article

What Is Writing Therapy?

How does writing therapy work, types of writing therapy, potential benefits of writing therapy, conditions treated by writing therapy, summary and outlook.

Writing therapy, or “expressive writing,” is a form of expressive therapy in which clients are encouraged to write about their thoughts and feelings—particularly those related to traumatic events or pressing concerns—to reap benefits such as reduced stress and improved physical health. 1 Writing therapy may be used in many environments, including in person or online . It may be supervised by a mental health professional or even occur with little or no direct influence from a counselor. There are several types of writing therapy, including, but not limited to narrative therapy, interactive journaling, focused writing, and songwriting. Although traditional psychotherapy , or talk therapy, has been standard practice in many therapeutic and counseling environments, evidence shows that writing therapy has many potential physical and psychological health benefits. 2

What Is the History of Therapeutic Writing / Expressive Writing?

Humans have expressed belief in the healing power of the written word since ancient times. For example, in the fourth century B.C.E., certain groups in Egypt believed that ingesting meaningful words written on papyrus would bring about health benefits. Words were thought to have medicinal and magical healing powers, so much so that inscribed above Egypt’s famed library of Alexandria was the phrase “The Healing Place of the Soul.” 1

However, the roots of modern therapeutic writing may be found in bibliotherapy , a form of therapy that employs literature and reading to help people deal with challenges in their own lives. 3 This practice dates back to the fifth century B.C.E. when it was thought to cure a condition called melancholia, or a deeply experienced depression .

More recently, writing therapy gained momentum in the United States in the early 19th century, 1 and it was popularized in the early 20th century with psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s Creative Writers and Day Dreaming. Though talk therapy was still the go-to approach, writing therapy gained steam in the 1930s and 1940s as creative therapies involving the arts , such as music, dance, and writing grew. The 1965 American Psychological Association (APA) convention, held in Chicago, Illinois, hosted a symposium that focused on written communications with clients. This symposium, organized by a division of the APA called Psychologists Interested in the Advancement of Psychotherapy, generated a boom in writing therapy research in the 1970s. 1

In the 1980s, social psychologist James Pennebaker emerged as a leading advocate and researcher of writing therapy. His research focused on the benefits of writing about or discussing one’s emotional disturbances, including reduced stress and improved immune function. He also claimed that writing about traumatic events could help people cope. His work helped propel writing therapy into the mainstream of psychotherapeutic practice. 1

There are two main theories as to how writing therapy works. The first posits that inhibition or suppression of emotions , traumatic events, or aspects of one’s identity constitutes a long-term, low-level stressor and has adverse health effects, such as an increased likelihood of becoming ill. Writing therapy can serve as an act of disclosure, and of written emotional expression, and therefore remove the stressor. However, this theory has become less accepted because research has shown that different acts of expression do not reap the same health benefits as writing therapy. 4

For example, Pennebaker conducted a study in 1996 in which one group of participants was asked to express a traumatic experience through physical movement, and another group was asked to express themselves through both physical movement and writing. Only the group that used both movement and writing showed significant physical health improvements. Pennebaker found that the specific language used while writing is associated with the physical and mental health benefits. When people’s emotional writing compositions were analyzed by judges and by the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software, positive emotion words like “happy” and a moderate number of negative emotion words like “sad” were associated with good physical health, while high and low levels of negative emotion words were associated with poor physical health. Compositions that showed an increase in causal words like “reason” and insight words like “realize” showed the most improved physical health in their writers. 4

When engaging in writing therapy, clients are asked to write about a traumatic experience. A standard practice might involve writing for 15 to 20 minutes for three consecutive days. 5 A 2002 study published in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine found that of three groups assigned to journal for one month, the group asked to write about “cognitions and emotions related to a trauma or stressor” enjoyed the most benefits of writing therapy; they had a better perspective on the stressful experience about which they wrote. 6

Sometimes this practice is self-generated. The act of journaling has increased in popularity, especially with the growth of aesthetic practices such as bullet journaling, which combines a journal, calendar, and planner. 7

Photo by Brent Gorwin on Unsplash

There are several types of writing therapy, which generally fall into two categories: writing therapy conducted with the guidance of a mental health counselor and self-motivated writing therapy, the latter of which anyone can take up at their own pace.

A counselor or mental health professional might use writing therapy with clients who find it difficult to verbalize their thoughts or emotions. Narrative therapy, a form of writing therapy that clients and therapists can use together, is often helpful in this situation. 8 Narrative therapy involves the client and mental health professional “reauthoring” a traumatic or problematic story from the client’s life. 9 This method helps the client recontextualize their experience by removing the assumptions and context they have assigned to it to see it from a more objective perspective. 8

Another common format, which can be practiced with or without the guidance of a mental health professional, is called interactive journaling. It combines aspects of writing therapy and bibliotherapy. In interactive journaling, clients are provided with a journal prompt, or a starting point, which they then use to inform their writing. This method is especially effective in substance abuse treatment because it can educate patients and promote reflection and exploration of their experiences. It can also benefit students in the health care field because it can help them empathize with and understand their clients’ experiences. 1

Two other types of writing therapy are focused writing and songwriting. Focused writing incorporates worksheets that educate and guide clients, 10 and songwriting combines music therapy and writing therapy to provide clients with an avenue to reminisce and express their emotions. 11

Researchers have found that expressive, or therapeutic writing, can have numerous physical and psychological health benefits, some of which include: 1

- better immune function

- fewer doctor visits

- less stress

- improved grades in school

- reduced emotional and physical distress

- decreased depression symptoms

- lower blood pressure

- improved liver function

- fewer missed days of work

- strengthened memory

In addition to its general benefits, writing therapy has been an easily accessible resource to treat people with many different conditions and stressful or traumatic experiences.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Evidence suggests that writing therapy can posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and the symptoms of depression often associated with PTSD. The potential effectiveness of writing therapy in helping people cope with trauma makes it a useful alternative when more traditional modes of therapy are ineffective or impossible to access. 12

For example, a study published in 2013 in the Journal of Sexual Medicine used writing therapy to treat 70 women who had experienced childhood sexual abuse. Researchers asked the women to write about trauma or sexual schema (the “cognitive generalizations” someone has about their sexual selves, informed by prior sexual experiences) during five 30-minute sessions, which occurred over up to five weeks. 13 At three different intervals—two weeks, one month, and six months—the study participants were asked to complete interviews and questionnaires regarding their sexual function, PTSD, and depression. Researchers found that between pretreatment and posttreatment, participants reported fewer symptoms of PTSD. According to study findings, participants who wrote about sexual schema were also more likely to recover from sexual dysfunction. 14

Some studies have found that engaging in writing therapy can help reduce anxiety . 15 , 16 In a study conducted in 2020 by faculty of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences in Iran, researchers administered three writing therapy sessions to pregnant women, plus two telephone calls between the sessions and basic pregnancy care, over four to six weeks. During the first session, the women were asked to write about their concerns regarding pregnancy and brainstorm solutions that would help relieve the anxiety they induce, and the phone calls encouraged them to follow through with the solutions. In the second session, researchers employed narrative therapy techniques and asked the women to write a story that outlined their concerns about pregnancy and then applied the solutions they had previously generated. The final session fostered a group discussion between the participants about the previous assignments. The study concluded that the women who engaged in writing therapy had significantly less anxiety than a comparison group who received only the standard pregnancy care. 17

Studies have shown that symptoms of depression decrease among people who utilize writing therapy. For example, in one study published in a 2014 issue of Cognitive Therapy and Research , one group of undergraduate students was tasked with non-emotional writing, or writing that does not focus on difficult or traumatic experiences and feelings, and another group was tasked with expressive writing, writing that does deal with emotional distress and trauma, focused in this case on emotional acceptance . The students in the latter group who experienced low or low to mild symptoms of depression saw a reduction in their symptoms. 18

Another study, conducted by researchers from the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Italy with women who had recently given birth, again divided participants into two groups; one performed expressive writing, and the other simply wrote about neutral topics. The women who used expressive writing had lessened depressive symptoms, whereas those in the neutral writing group saw no significant change. 19

Bereavement

People suffering the loss of a loved one can benefit greatly from writing therapy. It can reduce the number of negative feelings surrounding the event and allow for closure. It promotes self-care and therefore helps the client recover after a loss. 20 Writing therapy can also help reduce the separation anxiety that grief can prompt, gives clients a fresh perspective on their loss, and recognizes their bereavement journey. 21

A 2011 study published in the Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology conducted 10 writing sessions over five weeks with people who had lost pregnancies. The participants were asked to write about their pregnancy loss, write a letter to a friend as if the friend were experiencing the same loss, and write a letter to themselves or to someone who witnessed the loss. The participants’ levels of grief and loss decreased after the writing therapy treatment. 22

Technology has made many forms of therapy more accessible for many people. The internet can connect people in nearly any geographical zone to therapists who may be physically distant. Writing therapy, in particular, transitions easily to the virtual world; most forms don’t require face-to-face meetings at all and can be conducted over email.

In addition, writing therapy is a form of self-help intervention that anyone may practice. Many writing prompts (such as these links from Disability Dame and Dancing through the Rain ) are available online and enable people to immediately begin writing and benefit from this therapy. 23 Whether practitioner- or self-guided, writing therapy is an accessible practice that offers many potential benefits to those who use it.

- Moy, J. D. (2017). Reading and writing one’s way to wellness: The history of bibliotherapy and scriptotherapy. In Higler, S. (Ed.), New Directions in Literature and Medicine Studies (pp. 15–30). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51988-7_2

- Holden, J. D., & Mugerwa, S. (2012). Writing therapy: A new tool for general practice? British Journal of General Practice, 62(605), 661–663. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X659457

- THC Editorial Team. (May 22, 2021). Reading as therapy: Bibliotherapy and mental wellness. The Human Condition. https://thehumancondition.com/reading-as-therapy-bibliotherapy/

- Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00403.x

- Qian, J., Sun, S., Sun, X., Wu, M., Yu, X., & Zhou, X. (2020). Effects of expressive writing intervention for women’s PTSD, depression, anxiety, and stress related to pregnancy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Research, 288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112933

- Lutgendorf, S. K., & Ullrich, P. M. (2002). Journaling about stressful events: Effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_10

- Normark, M., & Tholander, J. (2020). Crafting personal information: Resistance, imperfection, and self-creation in bullet journaling. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376410

- Goodrich, T., Hancock, E., Kitchens, S., & Ricks, L. (2014). My story: The use of narrative therapy in individual and group counseling. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 9, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2013.870947

- Madigan, S. (2011). Narrative therapy. American Psychological Association.

- McGihon, N. N. (1996). Writing as a therapeutic modality. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 34(6), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.3928/0279-3695-19960601-08

- Ahessy, B. (2017). Song writing with clients who have dementia: A case study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.03.002

- Kamphuis, J. H., Reijntjes, A., & van Emmerik, A. A. P. (2013). Writing therapy for posttraumatic stress: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(2), 82–88.

- Anderson, B. L., & Cyranowski, J. M. (1994). Women’s sexual self-schema. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1079–1100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1079

- Lorenz, T. A., Meston, C. M., & Stephenson, K. R. (2013). Effects of expressive writing on sexual dysfunction, depression, and PTSD in women with a history of childhood sexual abuse: Results from a randomized clinical trial. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(9), 2177–2189. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12247

- Barrett, M. D., & Wolfer, T. A. (2001). Reducing anxiety through a structured writing intervention: A single-system evaluation. The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 82(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.179

- Shen, L., Yang, L., Zhang, J., & Zhang, M. (2018). Benefits of expressive writing in reducing test anxiety: A randomized controlled trial in Chinese samples. PLoS One, 13(2), Article e0191779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191779

- Esmaeilpour, K., Golizadeh, S., Mirghafourvand, M., Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S., & Montazeri, M. (2020). The effect of writing therapy on anxiety in pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.98256

- Baum, E. S., & Rude, S. S. (2013). Acceptance-enhanced expressive writing prevents symptoms in participants with low initial depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37. 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9435-x

- Camisasca, E., Caravita, S. C. S., Di Blasio, P., Ionio, C., Milani, L., & Valtolina, G. G. (2015). The effects of expressive writing on postpartum depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychological Reports, 117(3), 856–882. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.13.PR0.117c29z3

- Kristjanson, L. J., Loh, R., Nikoletti, S., O’Connor, M., & Willcock, B. (2004). Writing therapy for the bereaved: Evaluation of an intervention. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 6(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662103764978443

- Thatcher, C. (2021). Whys and what ifs: Writing and anxiety reduction in individuals bereaved by addiction. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/15401383.2021.1924097

- Kersting, A., Kroker, K., Schlicht, S., & Wagner, B. (2011). Internet-based treatment after pregnancy loss: concept and case study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 32(2), 72–78. http://doi.org/10.3109/0167482X.2011.553974

- Wright, J. (2002). Online counselling: Learning from writing therapy. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 30(3), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/030698802100002326

Related Articles

Art Therapy: Overview and Effectiveness

Problem-Solving Therapy: Overview and Effectiveness

Gestalt Therapy: Background, Principles, and Benefits

Bibliotherapy: Benefits and Effectiveness

Related books & audios.

The Feelings Book Journal

By lynda madison.

The Anxiety Journal

By corinne sweet.

Journal Therapy for Calming Anxiety

By kathleen adams.

The Simple Abundance Journal of Gratitude

By sarah ban breathnach.

Welcoming the Unwelcome

By pema chödrön, related organizations.

- National Coalition of Creative Arts Therapies Associations, Inc. (NCCATA)

<!– ADVERTISEMENT

–>

Explore Topics

- Relationships

- See All Subtopics

- Tic Disorders

- Energy Therapy

- Creative Arts Therapies

- Spirituality

- Mindfulness

- Forgiveness

- Life and Nature

- Philosophy and Thought

- Technology and Society

- Sadness, Grief and Despair

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

- Self-Report Measures, Screenings and Assessments

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Research Highlights

- Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT)

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

- Family Therapy

- Psychotherapy

- Humanness and Emotions

- Mental Health and Conditions

- Mindfulness and Presence

- Spirituality and Faith

Subscribe to our mailing list.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

On the Uncertain Border Between Writing and Therapy

Veronica esposito explores the intersection of creativity and trauma.

Years ago, I entered the world of mental health by getting myself a therapist. Little did I know that this small but decisive step would lead me deeper and deeper into the world of mental health, until I eventually found myself practicing therapy.

Every now and then I take a moment to look back on things, and I’m always kind of amazed: the changes the mental health world has made on me have been so great that it’s hard to imagine how the person I am today can actually occupy the same timeline as that of my pre-therapy self.

On a micro level, therapy has changed the very texture of the language that I use to speak and think my way through life; and on a macro level, it has transformed the basics of how I conceptualize myself and my world. To put it into literary terms, it’s a little like I switched the genre of my life—from say the claustrophobic modernism of a Franz Kafka to the truth-seeking comedy of a Lorrie Moore.

Going from Franz Kafka to Lorrie Moore is a pretty stunning change, and I think it shows the depth of what therapy can achieve. At its deepest, therapy seeks to make foundational change in who a person is. The various philosophies, approaches, techniques, laws, and ethics that collectively form the knowledge that therapy means to offer to the world is, at root, an attempt to imagine nothing less than how to live a good life and be a good person.

I’ve often reflected that such a transformative experience as that which I’ve had in the world of mental health must have made a sizable impact on who I am as a writer—and, in fact, many people have told me that they have seen the difference. I absolutely believe it’s there. Not just in how my writing looks and feels but in the very basis of what animates me to write, and basic assumptions I bring to my writing practice, how I envision and pursue the whole venture. My experiences have filled me with an interest in knowing exactly what therapy does for a writer’s work, which is why I set out to create this essay.

In researching this piece, I found something interesting: many creative writers and scientific researchers have explored the question of how creative writing may or may not be therapy, but I could not find anyone who had posed the question in the other direction: what impact therapy may have on one’s creative writing.

The research that I found on the matter tended—as research does—to focus on what effects specific applications of creative writing had on various mental health outcomes, like depression, dysfunction, and quality of life. There was an emphasis on trauma-processing and exploration, and the verdict was clear: writing can be an effective therapeutic tool.

By contrast, many of the creative writers who I read on the matter were much more leery of the prospect of writing being therapy. This is epitomized by memorist T Kira Madden’s Literary Hub essay “Against Catharsis: Writing is Not Therapy,” the jist of which states that artistic writing is much too prosaic and difficult to involve the “bleeding into the typewriter” that she equates with true “healing.” That is, when you’re laboring over every last word, there’s no room for catharsis—the very craftiness of creative labor precludes it, with Madden styling her writing self as just an actor working to create a product for an audience.

There were other voices, like that of Tara DaPra in Creative Nonfiction , who saw the writing process as more emotionally engaged and thus more therapeutic. In her essay “Writing Memoir and Writing for Therapy” she argues that “writing emotionally driven memoir is, in fact, cathartic, at least initially.” She see hammering out that messy first draft as akin to what one does in a therapy room, and she offers that this drafting can have further therapeutic benefits: you can let that draft sit for a while and return to your problems with fresh eyes, or the braver can show it to their friends and ask for input. In contrast to Madden’s boring workmanship, DaPra sees the writing process as driven by “emotion and instinct.”