Market Research

Your ultimate guide to questionnaires and how to design a good one

The written questionnaire is the heart and soul of any survey research project. Whether you conduct your survey using an online questionnaire, in person, by email or over the phone, the way you design your questionnaire plays a critical role in shaping the quality of the data and insights that you’ll get from your target audience. Keep reading to get actionable tips.

What is a questionnaire?

A questionnaire is a research tool consisting of a set of questions or other ‘prompts’ to collect data from a set of respondents.

When used in most research, a questionnaire will consist of a number of types of questions (primarily open-ended and closed) in order to gain both quantitative data that can be analyzed to draw conclusions, and qualitative data to provide longer, more specific explanations.

A research questionnaire is often mistaken for a survey - and many people use the term questionnaire and survey, interchangeably.

But that’s incorrect.

Which is what we talk about next.

Get started with our free survey maker with 50+ templates

Survey vs. questionnaire – what’s the difference?

Before we go too much further, let’s consider the differences between surveys and questionnaires.

These two terms are often used interchangeably, but there is an important difference between them.

Survey definition

A survey is the process of collecting data from a set of respondents and using it to gather insights.

Survey research can be conducted using a questionnaire, but won’t always involve one.

Questionnaire definition

A questionnaire is the list of questions you circulate to your target audience.

In other words, the survey is the task you’re carrying out, and the questionnaire is the instrument you’re using to do it.

By itself, a questionnaire doesn’t achieve much.

It’s when you put it into action as part of a survey that you start to get results.

Advantages vs disadvantages of using a questionnaire

While a questionnaire is a popular method to gather data for market research or other studies, there are a few disadvantages to using this method (although there are plenty of advantages to using a questionnaire too).

Let’s have a look at some of the advantages and disadvantages of using a questionnaire for collecting data.

Advantages of using a questionnaire

1. questionnaires are relatively cheap.

Depending on the complexity of your study, using a questionnaire can be cost effective compared to other methods.

You simply need to write your survey questionnaire, and send it out and then process the responses.

You can set up an online questionnaire relatively easily, or simply carry out market research on the street if that’s the best method.

2. You can get and analyze results quickly

Again depending on the size of your survey you can get results back from a questionnaire quickly, often within 24 hours of putting the questionnaire live.

It also means you can start to analyze responses quickly too.

3. They’re easily scalable

You can easily send an online questionnaire to anyone in the world and with the right software you can quickly identify your target audience and your questionnaire to them.

4. Questionnaires are easy to analyze

If your questionnaire design has been done properly, it’s quick and easy to analyze results from questionnaires once responses start to come back.

This is particularly useful with large scale market research projects.

Because all respondents are answering the same questions, it’s simple to identify trends.

5. You can use the results to make accurate decisions

As a research instrument, a questionnaire is ideal for commercial research because the data you get back is from your target audience (or ideal customers) and the information you get back on their thoughts, preferences or behaviors allows you to make business decisions.

6. A questionnaire can cover any topic

One of the biggest advantages of using questionnaires when conducting research is (because you can adapt them using different types and styles of open ended questions and closed ended questions) they can be used to gather data on almost any topic.

There are many types of questionnaires you can design to gather both quantitative data and qualitative data - so they’re a useful tool for all kinds of data analysis.

Disadvantages of using a questionnaire

1. respondents could lie.

This is by far the biggest risk with a questionnaire, especially when dealing with sensitive topics.

Rather than give their actual opinion, a respondent might feel pressured to give the answer they deem more socially acceptable, which doesn’t give you accurate results.

2. Respondents might not answer every question

There are all kinds of reasons respondents might not answer every question, from questionnaire length, they might not understand what’s being asked, or they simply might not want to answer it.

If you get questionnaires back without complete responses it could negatively affect your research data and provide an inaccurate picture.

3. They might interpret what’s being asked incorrectly

This is a particular problem when running a survey across geographical boundaries and often comes down to the design of the survey questionnaire.

If your questions aren’t written in a very clear way, the respondent might misunderstand what’s being asked and provide an answer that doesn’t reflect what they actually think.

Again this can negatively affect your research data.

4. You could introduce bias

The whole point of producing a questionnaire is to gather accurate data from which decisions can be made or conclusions drawn.

But the data collected can be heavily impacted if the researchers accidentally introduce bias into the questions.

This can be easily done if the researcher is trying to prove a certain hypothesis with their questionnaire, and unwittingly write questions that push people towards giving a certain answer.

In these cases respondents’ answers won’t accurately reflect what is really happening and stop you gathering more accurate data.

5. Respondents could get survey fatigue

One issue you can run into when sending out a questionnaire, particularly if you send them out regularly to the same survey sample, is that your respondents could start to suffer from survey fatigue.

In these circumstances, rather than thinking about the response options in the questionnaire and providing accurate answers, respondents could start to just tick boxes to get through the questionnaire quickly.

Again, this won’t give you an accurate data set.

Questionnaire design: How to do it

It’s essential to carefully craft a questionnaire to reduce survey error and optimize your data . The best way to think about the questionnaire is with the end result in mind.

How do you do that?

Start with questions, like:

- What is my research purpose ?

- What data do I need?

- How am I going to analyze that data?

- What questions are needed to best suit these variables?

Once you have a clear idea of the purpose of your survey, you’ll be in a better position to create an effective questionnaire.

Here are a few steps to help you get into the right mindset.

1. Keep the respondent front and center

A survey is the process of collecting information from people, so it needs to be designed around human beings first and foremost.

In his post about survey design theory, David Vannette, PhD, from the Qualtrics Methodology Lab explains the correlation between the way a survey is designed and the quality of data that is extracted.

“To begin designing an effective survey, take a step back and try to understand what goes on in your respondents’ heads when they are taking your survey.

This step is critical to making sure that your questionnaire makes it as likely as possible that the response process follows that expected path.”

From writing the questions to designing the survey flow, the respondent’s point of view should always be front and center in your mind during a questionnaire design.

2. How to write survey questions

Your questionnaire should only be as long as it needs to be, and every question needs to deliver value.

That means your questions must each have an individual purpose and produce the best possible data for that purpose, all while supporting the overall goal of the survey.

A question must also must be phrased in a way that is easy for all your respondents to understand, and does not produce false results.

To do this, remember the following principles:

Get into the respondent's head

The process for a respondent answering a survey question looks like this:

- The respondent reads the question and determines what information they need to answer it.

- They search their memory for that information.

- They make judgments about that information.

- They translate that judgment into one of the answer options you’ve provided. This is the process of taking the data they have and matching that information with the question that’s asked.

When wording questions, make sure the question means the same thing to all respondents. Words should have one meaning, few syllables, and the sentences should have few words.

Only use the words needed to ask your question and not a word more .

Note that it’s important that the respondent understands the intent behind your question.

If they don’t, they may answer a different question and the data can be skewed.

Some contextual help text, either in the introduction to the questionnaire or before the question itself, can help make sure the respondent understands your goals and the scope of your research.

Use mutually exclusive responses

Be sure to make your response categories mutually exclusive.

Consider the question:

What is your age?

Respondents that are 31 years old have two options, as do respondents that are 40 and 55. As a result, it is impossible to predict which category they will choose.

This can distort results and frustrate respondents. It can be easily avoided by making responses mutually exclusive.

The following question is much better:

This question is clear and will give us better results.

Ask specific questions

Nonspecific questions can confuse respondents and influence results.

Do you like orange juice?

- Like very much

- Neither like nor dislike

- Dislike very much

This question is very unclear. Is it asking about taste, texture, price, or the nutritional content? Different respondents will read this question differently.

A specific question will get more specific answers that are actionable.

How much do you like the current price of orange juice?

This question is more specific and will get better results.

If you need to collect responses about more than one aspect of a subject, you can include multiple questions on it. (Do you like the taste of orange juice? Do you like the nutritional content of orange juice? etc.)

Use a variety of question types

If all of your questionnaire, survey or poll questions are structured the same way (e.g. yes/no or multiple choice) the respondents are likely to become bored and tune out. That could mean they pay less attention to how they’re answering or even give up altogether.

Instead, mix up the question types to keep the experience interesting and varied. It’s a good idea to include questions that yield both qualitative and quantitative data.

For example, an open-ended questionnaire item such as “describe your attitude to life” will provide qualitative data – a form of information that’s rich, unstructured and unpredictable. The respondent will tell you in their own words what they think and feel.

A quantitative / close-ended questionnaire item, such as “Which word describes your attitude to life? a) practical b) philosophical” gives you a much more structured answer, but the answers will be less rich and detailed.

Open-ended questions take more thought and effort to answer, so use them sparingly. They also require a different kind of treatment once your survey is in the analysis stage.

3. Pre-test your questionnaire

Always pre-test a questionnaire before sending it out to respondents. This will help catch any errors you might have missed. You could ask a colleague, friend, or an expert to take the survey and give feedback. If possible, ask a few cognitive questions like, “how did you get to that response?” and “what were you thinking about when you answered that question?” Figure out what was easy for the responder and where there is potential for confusion. You can then re-word where necessary to make the experience as frictionless as possible.

If your resources allow, you could also consider using a focus group to test out your survey. Having multiple respondents road-test the questionnaire will give you a better understanding of its strengths and weaknesses. Match the focus group to your target respondents as closely as possible, for example in terms of age, background, gender, and level of education.

Note: Don't forget to make your survey as accessible as possible for increased response rates.

Questionnaire examples and templates

There are free questionnaire templates and example questions available for all kinds of surveys and market research, many of them online. But they’re not all created equal and you should use critical judgement when selecting one. After all, the questionnaire examples may be free but the time and energy you’ll spend carrying out a survey are not.

If you’re using online questionnaire templates as the basis for your own, make sure it has been developed by professionals and is specific to the type of research you’re doing to ensure higher completion rates. As we’ve explored here, using the wrong kinds of questions can result in skewed or messy data, and could even prompt respondents to abandon the questionnaire without finishing or give thoughtless answers.

You’ll find a full library of downloadable survey templates in the Qualtrics Marketplace , covering many different types of research from employee engagement to post-event feedback . All are fully customizable and have been developed by Qualtrics experts.

Qualtrics // Experience Management

Qualtrics is the technology platform that organizations use to collect, manage, and act on experience data, also called X-data™. The Qualtrics XM Platform™ is a system of action, used by teams, departments, and entire organizations to manage the four core experiences of business—customer, product, employee, and brand—on one platform.

Over 12,000 enterprises worldwide, including more than 75 percent of the Fortune 100 and 99 of the top 100 U.S. business schools, rely on Qualtrics to consistently build products that people love, create more loyal customers, develop a phenomenal employee culture, and build iconic brands.

Related Articles

June 27, 2023

The fresh insights people: Scaling research at Woolworths Group

June 20, 2023

Bank less, delight more: How Bankwest built an engine room for customer obsession

June 16, 2023

How Qualtrics Helps Three Local Governments Drive Better Outcomes Through Data Insights

April 1, 2023

Academic Experience

Great survey questions: How to write them & avoid common mistakes

March 21, 2023

Sample size calculator

March 9, 2023

Experience Management

X4 2023: See the XM innovations unveiled for customer research, marketing, and insights teams

February 22, 2023

Achieving better insights and better product delivery through in-house research

December 6, 2022

Improved Topic Sentiment Analysis using Discourse Segmentation

Stay up to date with the latest xm thought leadership, tips and news., request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

How to Design Effective Research Questionnaires for Robust Findings

As a staple in data collection, questionnaires help uncover robust and reliable findings that can transform industries, shape policies, and revolutionize understanding. Whether you are exploring societal trends or delving into scientific phenomena, the effectiveness of your research questionnaire can make or break your findings.

In this article, we aim to understand the core purpose of questionnaires, exploring how they serve as essential tools for gathering systematic data, both qualitative and quantitative, from diverse respondents. Read on as we explore the key elements that make up a winning questionnaire, the art of framing questions which are both compelling and rigorous, and the careful balance between simplicity and depth.

Table of Contents

The Role of Questionnaires in Research

So, what is a questionnaire? A questionnaire is a structured set of questions designed to collect information, opinions, attitudes, or behaviors from respondents. It is one of the most commonly used data collection methods in research. Moreover, questionnaires can be used in various research fields, including social sciences, market research, healthcare, education, and psychology. Their adaptability makes them suitable for investigating diverse research questions.

Questionnaire and survey are two terms often used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings in the context of research. A survey refers to the broader process of data collection that may involve various methods. A survey can encompass different data collection techniques, such as interviews , focus groups, observations, and yes, questionnaires.

Pros and Cons of Using Questionnaires in Research:

While questionnaires offer numerous advantages in research, they also come with some disadvantages that researchers must be aware of and address appropriately. Careful questionnaire design, validation, and consideration of potential biases can help mitigate these disadvantages and enhance the effectiveness of using questionnaires as a data collection method.

Structured vs Unstructured Questionnaires

Structured questionnaire:.

A structured questionnaire consists of questions with predefined response options. Respondents are presented with a fixed set of choices and are required to select from those options. The questions in a structured questionnaire are designed to elicit specific and quantifiable responses. Structured questionnaires are particularly useful for collecting quantitative data and are often employed in surveys and studies where standardized and comparable data are necessary.

Advantages of Structured Questionnaires:

- Easy to analyze and interpret: The fixed response options facilitate straightforward data analysis and comparison across respondents.

- Efficient for large-scale data collection: Structured questionnaires are time-efficient, allowing researchers to collect data from a large number of respondents.

- Reduces response bias: The predefined response options minimize potential response bias and maintain consistency in data collection.

Limitations of Structured Questionnaires:

- Lack of depth: Structured questionnaires may not capture in-depth insights or nuances as respondents are limited to pre-defined response choices. Hence, they may not reveal the reasons behind respondents’ choices, limiting the understanding of their perspectives.

- Limited flexibility: The fixed response options may not cover all potential responses, therefore, potentially restricting respondents’ answers.

Unstructured Questionnaire:

An unstructured questionnaire consists of questions that allow respondents to provide detailed and unrestricted responses. Unlike structured questionnaires, there are no predefined response options, giving respondents the freedom to express their thoughts in their own words. Furthermore, unstructured questionnaires are valuable for collecting qualitative data and obtaining in-depth insights into respondents’ experiences, opinions, or feelings.

Advantages of Unstructured Questionnaires:

- Rich qualitative data: Unstructured questionnaires yield detailed and comprehensive qualitative data, providing valuable and novel insights into respondents’ perspectives.

- Flexibility in responses: Respondents have the freedom to express themselves in their own words. Hence, allowing for a wide range of responses.

Limitations of Unstructured Questionnaires:

- Time-consuming analysis: Analyzing open-ended responses can be time-consuming, since, each response requires careful reading and interpretation.

- Subjectivity in interpretation: The analysis of open-ended responses may be subjective, as researchers interpret and categorize responses based on their judgment.

- May require smaller sample size: Due to the depth of responses, researchers may need a smaller sample size for comprehensive analysis, making generalizations more challenging.

Types of Questions in a Questionnaire

In a questionnaire, researchers typically use the following most common types of questions to gather a variety of information from respondents:

1. Open-Ended Questions:

These questions allow respondents to provide detailed and unrestricted responses in their own words. Open-ended questions are valuable for gathering qualitative data and in-depth insights.

Example: What suggestions do you have for improving our product?

2. Multiple-Choice Questions

Respondents choose one answer from a list of provided options. This type of question is suitable for gathering categorical data or preferences.

Example: Which of the following social media/academic networking platforms do you use to promote your research?

- ResearchGate

- Academia.edu

3. Dichotomous Questions

Respondents choose between two options, typically “yes” or “no”, “true” or “false”, or “agree” or “disagree”.

Example: Have you ever published in open access journals before?

4. Scaling Questions

These questions, also known as rating scale questions, use a predefined scale that allows respondents to rate or rank their level of agreement, satisfaction, importance, or other subjective assessments. These scales help researchers quantify subjective data and make comparisons across respondents.

There are several types of scaling techniques used in scaling questions:

i. Likert Scale:

The Likert scale is one of the most common scaling techniques. It presents respondents with a series of statements and asks them to rate their level of agreement or disagreement using a range of options, typically from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.For example: Please indicate your level of agreement with the statement: “The content presented in the webinar was relevant and aligned with the advertised topic.”

- Strongly Agree

- Strongly Disagree

ii. Semantic Differential Scale:

The semantic differential scale measures respondents’ perceptions or attitudes towards an item using opposite adjectives or bipolar words. Respondents rate the item on a scale between the two opposites. For example:

- Easy —— Difficult

- Satisfied —— Unsatisfied

- Very likely —— Very unlikely

iii. Numerical Rating Scale:

This scale requires respondents to provide a numerical rating on a predefined scale. It can be a simple 1 to 5 or 1 to 10 scale, where higher numbers indicate higher agreement, satisfaction, or importance.

iv. Ranking Questions:

Respondents rank items in order of preference or importance. Ranking questions help identify preferences or priorities.

Example: Please rank the following features of our app in order of importance (1 = Most Important, 5 = Least Important):

- User Interface

- Functionality

- Customer Support

By using a mix of question types, researchers can gather both quantitative and qualitative data, providing a comprehensive understanding of the research topic and enabling meaningful analysis and interpretation of the results. The choice of question types depends on the research objectives , the desired depth of information, and the data analysis requirements.

Methods of Administering Questionnaires

There are several methods for administering questionnaires, and the choice of method depends on factors such as the target population, research objectives , convenience, and resources available. Here are some common methods of administering questionnaires:

Each method has its advantages and limitations. Online surveys offer convenience and a large reach, but they may be limited to individuals with internet access. Face-to-face interviews allow for in-depth responses but can be time-consuming and costly. Telephone surveys have broad reach but may be limited by declining response rates. Researchers should choose the method that best suits their research objectives, target population, and available resources to ensure successful data collection.

How to Design a Questionnaire

Designing a good questionnaire is crucial for gathering accurate and meaningful data that aligns with your research objectives. Here are essential steps and tips to create a well-designed questionnaire:

1. Define Your Research Objectives : Clearly outline the purpose and specific information you aim to gather through the questionnaire.

2. Identify Your Target Audience : Understand respondents’ characteristics and tailor the questionnaire accordingly.

3. Develop the Questions :

- Write Clear and Concise Questions

- Avoid Leading or Biasing Questions

- Sequence Questions Logically

- Group Related Questions

- Include Demographic Questions

4. Provide Well-defined Response Options : Offer exhaustive response choices for closed-ended questions.

5. Consider Skip Logic and Branching : Customize the questionnaire based on previous answers.

6. Pilot Test the Questionnaire : Identify and address issues through a pilot study .

7. Seek Expert Feedback : Validate the questionnaire with subject matter experts.

8. Obtain Ethical Approval : Comply with ethical guidelines , obtain consent, and ensure confidentiality before administering the questionnaire.

9. Administer the Questionnaire : Choose the right mode and provide clear instructions.

10. Test the Survey Platform : Ensure compatibility and usability for online surveys.

By following these steps and paying attention to questionnaire design principles, you can create a well-structured and effective questionnaire that gathers reliable data and helps you achieve your research objectives.

Characteristics of a Good Questionnaire

A good questionnaire possesses several essential elements that contribute to its effectiveness. Furthermore, these characteristics ensure that the questionnaire is well-designed, easy to understand, and capable of providing valuable insights. Here are some key characteristics of a good questionnaire:

1. Clarity and Simplicity : Questions should be clear, concise, and unambiguous. Avoid using complex language or technical terms that may confuse respondents. Simple and straightforward questions ensure that respondents interpret them consistently.

2. Relevance and Focus : Each question should directly relate to the research objectives and contribute to answering the research questions. Consequently, avoid including extraneous or irrelevant questions that could lead to data clutter.

3. Mix of Question Types : Utilize a mix of question types, including open-ended, Likert scale, and multiple-choice questions. This variety allows for both qualitative and quantitative data collections .

4. Validity and Reliability : Ensure the questionnaire measures what it intends to measure (validity) and produces consistent results upon repeated administration (reliability). Validation should be conducted through expert review and previous research.

5. Appropriate Length : Keep the questionnaire’s length appropriate and manageable to avoid respondent fatigue or dropouts. Long questionnaires may result in incomplete or rushed responses.

6. Clear Instructions : Include clear instructions at the beginning of the questionnaire to guide respondents on how to complete it. Explain any technical terms, formats, or concepts if necessary.

7. User-Friendly Format : Design the questionnaire to be visually appealing and user-friendly. Use consistent formatting, adequate spacing, and a logical page layout.

8. Data Validation and Cleaning : Incorporate validation checks to ensure data accuracy and reliability. Consider mechanisms to detect and correct inconsistent or missing responses during data cleaning.

By incorporating these characteristics, researchers can create a questionnaire that maximizes data quality, minimizes response bias, and provides valuable insights for their research.

In the pursuit of advancing research and gaining meaningful insights, investing time and effort into designing effective questionnaires is a crucial step. A well-designed questionnaire is more than a mere set of questions; it is a masterpiece of precision and ingenuity. Each question plays a vital role in shaping the narrative of our research, guiding us through the labyrinth of data to meaningful conclusions. Indeed, a well-designed questionnaire serves as a powerful tool for unlocking valuable insights and generating robust findings that impact society positively.

Have you ever designed a research questionnaire? Reflect on your experience and share your insights with researchers globally through Enago Academy’s Open Blogging Platform . Join our diverse community of 1000K+ researchers and authors to exchange ideas, strategies, and best practices, and together, let’s shape the future of data collection and maximize the impact of questionnaires in the ever-evolving landscape of research.

Frequently Asked Questions

A research questionnaire is a structured tool used to gather data from participants in a systematic manner. It consists of a series of carefully crafted questions designed to collect specific information related to a research study.

Questionnaires play a pivotal role in both quantitative and qualitative research, enabling researchers to collect insights, opinions, attitudes, or behaviors from respondents. This aids in hypothesis testing, understanding, and informed decision-making, ensuring consistency, efficiency, and facilitating comparisons.

Questionnaires are a versatile tool employed in various research designs to gather data efficiently and comprehensively. They find extensive use in both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies, making them a fundamental component of research across disciplines. Some research designs that commonly utilize questionnaires include: a) Cross-Sectional Studies b) Longitudinal Studies c) Descriptive Research d) Correlational Studies e) Causal-Comparative Studies f) Experimental Research g) Survey Research h) Case Studies i) Exploratory Research

A survey is a comprehensive data collection method that can include various techniques like interviews and observations. A questionnaire is a specific set of structured questions within a survey designed to gather standardized responses. While a survey is a broader approach, a questionnaire is a focused tool for collecting specific data.

The choice of questionnaire type depends on the research objectives, the type of data required, and the preferences of respondents. Some common types include: • Structured Questionnaires: These questionnaires consist of predefined, closed-ended questions with fixed response options. They are easy to analyze and suitable for quantitative research. • Semi-Structured Questionnaires: These questionnaires combine closed-ended questions with open-ended ones. They offer more flexibility for respondents to provide detailed explanations. • Unstructured Questionnaires: These questionnaires contain open-ended questions only, allowing respondents to express their thoughts and opinions freely. They are commonly used in qualitative research.

Following these steps ensures effective questionnaire administration for reliable data collection: • Choose a Method: Decide on online, face-to-face, mail, or phone administration. • Online Surveys: Use platforms like SurveyMonkey • Pilot Test: Test on a small group before full deployment • Clear Instructions: Provide concise guidelines • Follow-Up: Send reminders if needed

Thank you, Riya. This is quite helpful. As discussed, response bias is one of the disadvantages in the use of questionnaires. One way to help limit this can be to use scenario based questions. These type of questions may help the respondents to be more reflective and active in the process.

Thank you, Dear Riya. This is quite helpful.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Science under Surveillance: Journals adopt advanced AI to uncover image manipulation

Journals are increasingly turning to cutting-edge AI tools to uncover deceitful images published in manuscripts.…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Research Question 101 📖

Everything you need to know to write a high-quality research question

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2023

If you’ve landed on this page, you’re probably asking yourself, “ What is a research question? ”. Well, you’ve come to the right place. In this post, we’ll explain what a research question is , how it’s differen t from a research aim, and how to craft a high-quality research question that sets you up for success.

Research Question 101

What is a research question.

- Research questions vs research aims

- The 4 types of research questions

- How to write a research question

- Frequently asked questions

- Examples of research questions

As the name suggests, the research question is the core question (or set of questions) that your study will (attempt to) answer .

In many ways, a research question is akin to a target in archery . Without a clear target, you won’t know where to concentrate your efforts and focus. Essentially, your research question acts as the guiding light throughout your project and informs every choice you make along the way.

Let’s look at some examples:

What impact does social media usage have on the mental health of teenagers in New York?

How does the introduction of a minimum wage affect employment levels in small businesses in outer London?

How does the portrayal of women in 19th-century American literature reflect the societal attitudes of the time?

What are the long-term effects of intermittent fasting on heart health in adults?

As you can see in these examples, research questions are clear, specific questions that can be feasibly answered within a study. These are important attributes and we’ll discuss each of them in more detail a little later . If you’d like to see more examples of research questions, you can find our RQ mega-list here .

Research Questions vs Research Aims

At this point, you might be asking yourself, “ How is a research question different from a research aim? ”. Within any given study, the research aim and research question (or questions) are tightly intertwined , but they are separate things . Let’s unpack that a little.

A research aim is typically broader in nature and outlines what you hope to achieve with your research. It doesn’t ask a specific question but rather gives a summary of what you intend to explore.

The research question, on the other hand, is much more focused . It’s the specific query you’re setting out to answer. It narrows down the research aim into a detailed, researchable question that will guide your study’s methods and analysis.

Let’s look at an example:

Research Aim: To explore the effects of climate change on marine life in Southern Africa.

Research Question: How does ocean acidification caused by climate change affect the reproduction rates of coral reefs?

As you can see, the research aim gives you a general focus , while the research question details exactly what you want to find out.

Need a helping hand?

Types of research questions

Now that we’ve defined what a research question is, let’s look at the different types of research questions that you might come across. Broadly speaking, there are (at least) four different types of research questions – descriptive , comparative , relational , and explanatory .

Descriptive questions ask what is happening. In other words, they seek to describe a phenomena or situation . An example of a descriptive research question could be something like “What types of exercise do high-performing UK executives engage in?”. This would likely be a bit too basic to form an interesting study, but as you can see, the research question is just focused on the what – in other words, it just describes the situation.

Comparative research questions , on the other hand, look to understand the way in which two or more things differ , or how they’re similar. An example of a comparative research question might be something like “How do exercise preferences vary between middle-aged men across three American cities?”. As you can see, this question seeks to compare the differences (or similarities) in behaviour between different groups.

Next up, we’ve got exploratory research questions , which ask why or how is something happening. While the other types of questions we looked at focused on the what, exploratory research questions are interested in the why and how . As an example, an exploratory research question might ask something like “Why have bee populations declined in Germany over the last 5 years?”. As you can, this question is aimed squarely at the why, rather than the what.

Last but not least, we have relational research questions . As the name suggests, these types of research questions seek to explore the relationships between variables . Here, an example could be something like “What is the relationship between X and Y” or “Does A have an impact on B”. As you can see, these types of research questions are interested in understanding how constructs or variables are connected , and perhaps, whether one thing causes another.

Of course, depending on how fine-grained you want to get, you can argue that there are many more types of research questions , but these four categories give you a broad idea of the different flavours that exist out there. It’s also worth pointing out that a research question doesn’t need to fit perfectly into one category – in many cases, a research question might overlap into more than just one category and that’s okay.

The key takeaway here is that research questions can take many different forms , and it’s useful to understand the nature of your research question so that you can align your research methodology accordingly.

How To Write A Research Question

As we alluded earlier, a well-crafted research question needs to possess very specific attributes, including focus , clarity and feasibility . But that’s not all – a rock-solid research question also needs to be rooted and aligned . Let’s look at each of these.

A strong research question typically has a single focus. So, don’t try to cram multiple questions into one research question; rather split them up into separate questions (or even subquestions), each with their own specific focus. As a rule of thumb, narrow beats broad when it comes to research questions.

Clear and specific

A good research question is clear and specific, not vague and broad. State clearly exactly what you want to find out so that any reader can quickly understand what you’re looking to achieve with your study. Along the same vein, try to avoid using bulky language and jargon – aim for clarity.

Unfortunately, even a super tantalising and thought-provoking research question has little value if you cannot feasibly answer it. So, think about the methodological implications of your research question while you’re crafting it. Most importantly, make sure that you know exactly what data you’ll need (primary or secondary) and how you’ll analyse that data.

A good research question (and a research topic, more broadly) should be rooted in a clear research gap and research problem . Without a well-defined research gap, you risk wasting your effort pursuing a question that’s already been adequately answered (and agreed upon) by the research community. A well-argued research gap lays at the heart of a valuable study, so make sure you have your gap clearly articulated and that your research question directly links to it.

As we mentioned earlier, your research aim and research question are (or at least, should be) tightly linked. So, make sure that your research question (or set of questions) aligns with your research aim . If not, you’ll need to revise one of the two to achieve this.

FAQ: Research Questions

Research question faqs, how many research questions should i have, what should i avoid when writing a research question, can a research question be a statement.

Typically, a research question is phrased as a question, not a statement. A question clearly indicates what you’re setting out to discover.

Can a research question be too broad or too narrow?

Yes. A question that’s too broad makes your research unfocused, while a question that’s too narrow limits the scope of your study.

Here’s an example of a research question that’s too broad:

“Why is mental health important?”

Conversely, here’s an example of a research question that’s likely too narrow:

“What is the impact of sleep deprivation on the exam scores of 19-year-old males in London studying maths at The Open University?”

Can I change my research question during the research process?

How do i know if my research question is good.

A good research question is focused, specific, practical, rooted in a research gap, and aligned with the research aim. If your question meets these criteria, it’s likely a strong question.

Is a research question similar to a hypothesis?

Not quite. A hypothesis is a testable statement that predicts an outcome, while a research question is a query that you’re trying to answer through your study. Naturally, there can be linkages between a study’s research questions and hypothesis, but they serve different functions.

How are research questions and research objectives related?

The research question is a focused and specific query that your study aims to answer. It’s the central issue you’re investigating. The research objective, on the other hand, outlines the steps you’ll take to answer your research question. Research objectives are often more action-oriented and can be broken down into smaller tasks that guide your research process. In a sense, they’re something of a roadmap that helps you answer your research question.

Need some inspiration?

If you’d like to see more examples of research questions, check out our research question mega list here . Alternatively, if you’d like 1-on-1 help developing a high-quality research question, consider our private coaching service .

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Writing survey questions.

Perhaps the most important part of the survey process is the creation of questions that accurately measure the opinions, experiences and behaviors of the public. Accurate random sampling will be wasted if the information gathered is built on a shaky foundation of ambiguous or biased questions. Creating good measures involves both writing good questions and organizing them to form the questionnaire.

Questionnaire design is a multistage process that requires attention to many details at once. Designing the questionnaire is complicated because surveys can ask about topics in varying degrees of detail, questions can be asked in different ways, and questions asked earlier in a survey may influence how people respond to later questions. Researchers are also often interested in measuring change over time and therefore must be attentive to how opinions or behaviors have been measured in prior surveys.

Surveyors may conduct pilot tests or focus groups in the early stages of questionnaire development in order to better understand how people think about an issue or comprehend a question. Pretesting a survey is an essential step in the questionnaire design process to evaluate how people respond to the overall questionnaire and specific questions, especially when questions are being introduced for the first time.

For many years, surveyors approached questionnaire design as an art, but substantial research over the past forty years has demonstrated that there is a lot of science involved in crafting a good survey questionnaire. Here, we discuss the pitfalls and best practices of designing questionnaires.

Question development

There are several steps involved in developing a survey questionnaire. The first is identifying what topics will be covered in the survey. For Pew Research Center surveys, this involves thinking about what is happening in our nation and the world and what will be relevant to the public, policymakers and the media. We also track opinion on a variety of issues over time so we often ensure that we update these trends on a regular basis to better understand whether people’s opinions are changing.

At Pew Research Center, questionnaire development is a collaborative and iterative process where staff meet to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development. We frequently test new survey questions ahead of time through qualitative research methods such as focus groups , cognitive interviews, pretesting (often using an online, opt-in sample ), or a combination of these approaches. Researchers use insights from this testing to refine questions before they are asked in a production survey, such as on the ATP.

Measuring change over time

Many surveyors want to track changes over time in people’s attitudes, opinions and behaviors. To measure change, questions are asked at two or more points in time. A cross-sectional design surveys different people in the same population at multiple points in time. A panel, such as the ATP, surveys the same people over time. However, it is common for the set of people in survey panels to change over time as new panelists are added and some prior panelists drop out. Many of the questions in Pew Research Center surveys have been asked in prior polls. Asking the same questions at different points in time allows us to report on changes in the overall views of the general public (or a subset of the public, such as registered voters, men or Black Americans), or what we call “trending the data”.

When measuring change over time, it is important to use the same question wording and to be sensitive to where the question is asked in the questionnaire to maintain a similar context as when the question was asked previously (see question wording and question order for further information). All of our survey reports include a topline questionnaire that provides the exact question wording and sequencing, along with results from the current survey and previous surveys in which we asked the question.

The Center’s transition from conducting U.S. surveys by live telephone interviewing to an online panel (around 2014 to 2020) complicated some opinion trends, but not others. Opinion trends that ask about sensitive topics (e.g., personal finances or attending religious services ) or that elicited volunteered answers (e.g., “neither” or “don’t know”) over the phone tended to show larger differences than other trends when shifting from phone polls to the online ATP. The Center adopted several strategies for coping with changes to data trends that may be related to this change in methodology. If there is evidence suggesting that a change in a trend stems from switching from phone to online measurement, Center reports flag that possibility for readers to try to head off confusion or erroneous conclusions.

Open- and closed-ended questions

One of the most significant decisions that can affect how people answer questions is whether the question is posed as an open-ended question, where respondents provide a response in their own words, or a closed-ended question, where they are asked to choose from a list of answer choices.

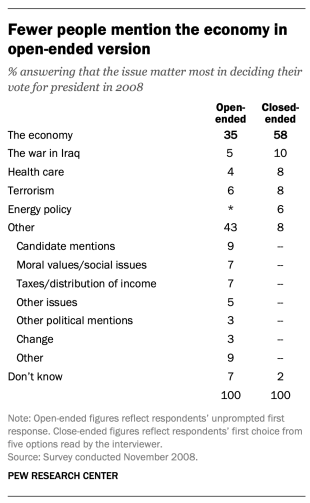

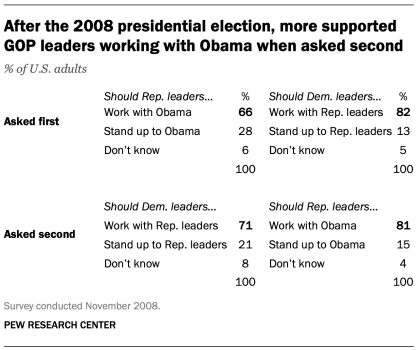

For example, in a poll conducted after the 2008 presidential election, people responded very differently to two versions of the question: “What one issue mattered most to you in deciding how you voted for president?” One was closed-ended and the other open-ended. In the closed-ended version, respondents were provided five options and could volunteer an option not on the list.

When explicitly offered the economy as a response, more than half of respondents (58%) chose this answer; only 35% of those who responded to the open-ended version volunteered the economy. Moreover, among those asked the closed-ended version, fewer than one-in-ten (8%) provided a response other than the five they were read. By contrast, fully 43% of those asked the open-ended version provided a response not listed in the closed-ended version of the question. All of the other issues were chosen at least slightly more often when explicitly offered in the closed-ended version than in the open-ended version. (Also see “High Marks for the Campaign, a High Bar for Obama” for more information.)

Researchers will sometimes conduct a pilot study using open-ended questions to discover which answers are most common. They will then develop closed-ended questions based off that pilot study that include the most common responses as answer choices. In this way, the questions may better reflect what the public is thinking, how they view a particular issue, or bring certain issues to light that the researchers may not have been aware of.

When asking closed-ended questions, the choice of options provided, how each option is described, the number of response options offered, and the order in which options are read can all influence how people respond. One example of the impact of how categories are defined can be found in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in January 2002. When half of the sample was asked whether it was “more important for President Bush to focus on domestic policy or foreign policy,” 52% chose domestic policy while only 34% said foreign policy. When the category “foreign policy” was narrowed to a specific aspect – “the war on terrorism” – far more people chose it; only 33% chose domestic policy while 52% chose the war on terrorism.

In most circumstances, the number of answer choices should be kept to a relatively small number – just four or perhaps five at most – especially in telephone surveys. Psychological research indicates that people have a hard time keeping more than this number of choices in mind at one time. When the question is asking about an objective fact and/or demographics, such as the religious affiliation of the respondent, more categories can be used. In fact, they are encouraged to ensure inclusivity. For example, Pew Research Center’s standard religion questions include more than 12 different categories, beginning with the most common affiliations (Protestant and Catholic). Most respondents have no trouble with this question because they can expect to see their religious group within that list in a self-administered survey.

In addition to the number and choice of response options offered, the order of answer categories can influence how people respond to closed-ended questions. Research suggests that in telephone surveys respondents more frequently choose items heard later in a list (a “recency effect”), and in self-administered surveys, they tend to choose items at the top of the list (a “primacy” effect).

Because of concerns about the effects of category order on responses to closed-ended questions, many sets of response options in Pew Research Center’s surveys are programmed to be randomized to ensure that the options are not asked in the same order for each respondent. Rotating or randomizing means that questions or items in a list are not asked in the same order to each respondent. Answers to questions are sometimes affected by questions that precede them. By presenting questions in a different order to each respondent, we ensure that each question gets asked in the same context as every other question the same number of times (e.g., first, last or any position in between). This does not eliminate the potential impact of previous questions on the current question, but it does ensure that this bias is spread randomly across all of the questions or items in the list. For instance, in the example discussed above about what issue mattered most in people’s vote, the order of the five issues in the closed-ended version of the question was randomized so that no one issue appeared early or late in the list for all respondents. Randomization of response items does not eliminate order effects, but it does ensure that this type of bias is spread randomly.

Questions with ordinal response categories – those with an underlying order (e.g., excellent, good, only fair, poor OR very favorable, mostly favorable, mostly unfavorable, very unfavorable) – are generally not randomized because the order of the categories conveys important information to help respondents answer the question. Generally, these types of scales should be presented in order so respondents can easily place their responses along the continuum, but the order can be reversed for some respondents. For example, in one of Pew Research Center’s questions about abortion, half of the sample is asked whether abortion should be “legal in all cases, legal in most cases, illegal in most cases, illegal in all cases,” while the other half of the sample is asked the same question with the response categories read in reverse order, starting with “illegal in all cases.” Again, reversing the order does not eliminate the recency effect but distributes it randomly across the population.

Question wording

The choice of words and phrases in a question is critical in expressing the meaning and intent of the question to the respondent and ensuring that all respondents interpret the question the same way. Even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties, ” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.

There has been a substantial amount of research to gauge the impact of different ways of asking questions and how to minimize differences in the way respondents interpret what is being asked. The issues related to question wording are more numerous than can be treated adequately in this short space, but below are a few of the important things to consider:

First, it is important to ask questions that are clear and specific and that each respondent will be able to answer. If a question is open-ended, it should be evident to respondents that they can answer in their own words and what type of response they should provide (an issue or problem, a month, number of days, etc.). Closed-ended questions should include all reasonable responses (i.e., the list of options is exhaustive) and the response categories should not overlap (i.e., response options should be mutually exclusive). Further, it is important to discern when it is best to use forced-choice close-ended questions (often denoted with a radio button in online surveys) versus “select-all-that-apply” lists (or check-all boxes). A 2019 Center study found that forced-choice questions tend to yield more accurate responses, especially for sensitive questions. Based on that research, the Center generally avoids using select-all-that-apply questions.

It is also important to ask only one question at a time. Questions that ask respondents to evaluate more than one concept (known as double-barreled questions) – such as “How much confidence do you have in President Obama to handle domestic and foreign policy?” – are difficult for respondents to answer and often lead to responses that are difficult to interpret. In this example, it would be more effective to ask two separate questions, one about domestic policy and another about foreign policy.

In general, questions that use simple and concrete language are more easily understood by respondents. It is especially important to consider the education level of the survey population when thinking about how easy it will be for respondents to interpret and answer a question. Double negatives (e.g., do you favor or oppose not allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry) or unfamiliar abbreviations or jargon (e.g., ANWR instead of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) can result in respondent confusion and should be avoided.

Similarly, it is important to consider whether certain words may be viewed as biased or potentially offensive to some respondents, as well as the emotional reaction that some words may provoke. For example, in a 2005 Pew Research Center survey, 51% of respondents said they favored “making it legal for doctors to give terminally ill patients the means to end their lives,” but only 44% said they favored “making it legal for doctors to assist terminally ill patients in committing suicide.” Although both versions of the question are asking about the same thing, the reaction of respondents was different. In another example, respondents have reacted differently to questions using the word “welfare” as opposed to the more generic “assistance to the poor.” Several experiments have shown that there is much greater public support for expanding “assistance to the poor” than for expanding “welfare.”

We often write two versions of a question and ask half of the survey sample one version of the question and the other half the second version. Thus, we say we have two forms of the questionnaire. Respondents are assigned randomly to receive either form, so we can assume that the two groups of respondents are essentially identical. On questions where two versions are used, significant differences in the answers between the two forms tell us that the difference is a result of the way we worded the two versions.

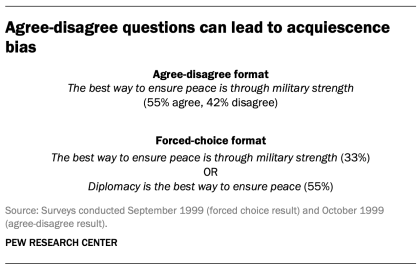

One of the most common formats used in survey questions is the “agree-disagree” format. In this type of question, respondents are asked whether they agree or disagree with a particular statement. Research has shown that, compared with the better educated and better informed, less educated and less informed respondents have a greater tendency to agree with such statements. This is sometimes called an “acquiescence bias” (since some kinds of respondents are more likely to acquiesce to the assertion than are others). This behavior is even more pronounced when there’s an interviewer present, rather than when the survey is self-administered. A better practice is to offer respondents a choice between alternative statements. A Pew Research Center experiment with one of its routinely asked values questions illustrates the difference that question format can make. Not only does the forced choice format yield a very different result overall from the agree-disagree format, but the pattern of answers between respondents with more or less formal education also tends to be very different.

One other challenge in developing questionnaires is what is called “social desirability bias.” People have a natural tendency to want to be accepted and liked, and this may lead people to provide inaccurate answers to questions that deal with sensitive subjects. Research has shown that respondents understate alcohol and drug use, tax evasion and racial bias. They also may overstate church attendance, charitable contributions and the likelihood that they will vote in an election. Researchers attempt to account for this potential bias in crafting questions about these topics. For instance, when Pew Research Center surveys ask about past voting behavior, it is important to note that circumstances may have prevented the respondent from voting: “In the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, did things come up that kept you from voting, or did you happen to vote?” The choice of response options can also make it easier for people to be honest. For example, a question about church attendance might include three of six response options that indicate infrequent attendance. Research has also shown that social desirability bias can be greater when an interviewer is present (e.g., telephone and face-to-face surveys) than when respondents complete the survey themselves (e.g., paper and web surveys).

Lastly, because slight modifications in question wording can affect responses, identical question wording should be used when the intention is to compare results to those from earlier surveys. Similarly, because question wording and responses can vary based on the mode used to survey respondents, researchers should carefully evaluate the likely effects on trend measurements if a different survey mode will be used to assess change in opinion over time.

Question order

Once the survey questions are developed, particular attention should be paid to how they are ordered in the questionnaire. Surveyors must be attentive to how questions early in a questionnaire may have unintended effects on how respondents answer subsequent questions. Researchers have demonstrated that the order in which questions are asked can influence how people respond; earlier questions can unintentionally provide context for the questions that follow (these effects are called “order effects”).

One kind of order effect can be seen in responses to open-ended questions. Pew Research Center surveys generally ask open-ended questions about national problems, opinions about leaders and similar topics near the beginning of the questionnaire. If closed-ended questions that relate to the topic are placed before the open-ended question, respondents are much more likely to mention concepts or considerations raised in those earlier questions when responding to the open-ended question.

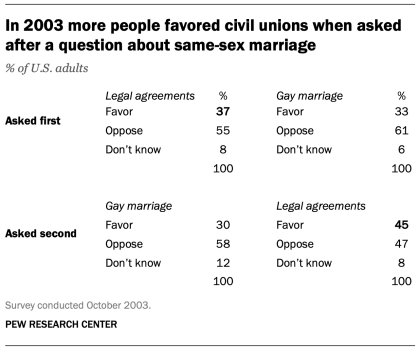

For closed-ended opinion questions, there are two main types of order effects: contrast effects ( where the order results in greater differences in responses), and assimilation effects (where responses are more similar as a result of their order).

An example of a contrast effect can be seen in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in October 2003, a dozen years before same-sex marriage was legalized in the U.S. That poll found that people were more likely to favor allowing gays and lesbians to enter into legal agreements that give them the same rights as married couples when this question was asked after one about whether they favored or opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry (45% favored legal agreements when asked after the marriage question, but 37% favored legal agreements without the immediate preceding context of a question about same-sex marriage). Responses to the question about same-sex marriage, meanwhile, were not significantly affected by its placement before or after the legal agreements question.

Another experiment embedded in a December 2008 Pew Research Center poll also resulted in a contrast effect. When people were asked “All in all, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country today?” immediately after having been asked “Do you approve or disapprove of the way George W. Bush is handling his job as president?”; 88% said they were dissatisfied, compared with only 78% without the context of the prior question.

Responses to presidential approval remained relatively unchanged whether national satisfaction was asked before or after it. A similar finding occurred in December 2004 when both satisfaction and presidential approval were much higher (57% were dissatisfied when Bush approval was asked first vs. 51% when general satisfaction was asked first).

Several studies also have shown that asking a more specific question before a more general question (e.g., asking about happiness with one’s marriage before asking about one’s overall happiness) can result in a contrast effect. Although some exceptions have been found, people tend to avoid redundancy by excluding the more specific question from the general rating.

Assimilation effects occur when responses to two questions are more consistent or closer together because of their placement in the questionnaire. We found an example of an assimilation effect in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in November 2008 when we asked whether Republican leaders should work with Obama or stand up to him on important issues and whether Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders or stand up to them on important issues. People were more likely to say that Republican leaders should work with Obama when the question was preceded by the one asking what Democratic leaders should do in working with Republican leaders (81% vs. 66%). However, when people were first asked about Republican leaders working with Obama, fewer said that Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders (71% vs. 82%).

The order questions are asked is of particular importance when tracking trends over time. As a result, care should be taken to ensure that the context is similar each time a question is asked. Modifying the context of the question could call into question any observed changes over time (see measuring change over time for more information).

A questionnaire, like a conversation, should be grouped by topic and unfold in a logical order. It is often helpful to begin the survey with simple questions that respondents will find interesting and engaging. Throughout the survey, an effort should be made to keep the survey interesting and not overburden respondents with several difficult questions right after one another. Demographic questions such as income, education or age should not be asked near the beginning of a survey unless they are needed to determine eligibility for the survey or for routing respondents through particular sections of the questionnaire. Even then, it is best to precede such items with more interesting and engaging questions. One virtue of survey panels like the ATP is that demographic questions usually only need to be asked once a year, not in each survey.

U.S. Surveys

Other research methods.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Questions

Definition:

Research questions are the specific questions that guide a research study or inquiry. These questions help to define the scope of the research and provide a clear focus for the study. Research questions are usually developed at the beginning of a research project and are designed to address a particular research problem or objective.

Types of Research Questions

Types of Research Questions are as follows:

Descriptive Research Questions

These aim to describe a particular phenomenon, group, or situation. For example:

- What are the characteristics of the target population?

- What is the prevalence of a particular disease in a specific region?

Exploratory Research Questions

These aim to explore a new area of research or generate new ideas or hypotheses. For example:

- What are the potential causes of a particular phenomenon?

- What are the possible outcomes of a specific intervention?

Explanatory Research Questions

These aim to understand the relationship between two or more variables or to explain why a particular phenomenon occurs. For example:

- What is the effect of a specific drug on the symptoms of a particular disease?

- What are the factors that contribute to employee turnover in a particular industry?

Predictive Research Questions

These aim to predict a future outcome or trend based on existing data or trends. For example :

- What will be the future demand for a particular product or service?

- What will be the future prevalence of a particular disease?

Evaluative Research Questions

These aim to evaluate the effectiveness of a particular intervention or program. For example:

- What is the impact of a specific educational program on student learning outcomes?

- What is the effectiveness of a particular policy or program in achieving its intended goals?

How to Choose Research Questions

Choosing research questions is an essential part of the research process and involves careful consideration of the research problem, objectives, and design. Here are some steps to consider when choosing research questions:

- Identify the research problem: Start by identifying the problem or issue that you want to study. This could be a gap in the literature, a social or economic issue, or a practical problem that needs to be addressed.

- Conduct a literature review: Conducting a literature review can help you identify existing research in your area of interest and can help you formulate research questions that address gaps or limitations in the existing literature.

- Define the research objectives : Clearly define the objectives of your research. What do you want to achieve with your study? What specific questions do you want to answer?

- Consider the research design : Consider the research design that you plan to use. This will help you determine the appropriate types of research questions to ask. For example, if you plan to use a qualitative approach, you may want to focus on exploratory or descriptive research questions.

- Ensure that the research questions are clear and answerable: Your research questions should be clear and specific, and should be answerable with the data that you plan to collect. Avoid asking questions that are too broad or vague.

- Get feedback : Get feedback from your supervisor, colleagues, or peers to ensure that your research questions are relevant, feasible, and meaningful.

How to Write Research Questions

Guide for Writing Research Questions:

- Start with a clear statement of the research problem: Begin by stating the problem or issue that your research aims to address. This will help you to formulate focused research questions.

- Use clear language : Write your research questions in clear and concise language that is easy to understand. Avoid using jargon or technical terms that may be unfamiliar to your readers.

- Be specific: Your research questions should be specific and focused. Avoid broad questions that are difficult to answer. For example, instead of asking “What is the impact of climate change on the environment?” ask “What are the effects of rising sea levels on coastal ecosystems?”

- Use appropriate question types: Choose the appropriate question types based on the research design and objectives. For example, if you are conducting a qualitative study, you may want to use open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed responses.

- Consider the feasibility of your questions : Ensure that your research questions are feasible and can be answered with the resources available. Consider the data sources and methods of data collection when writing your questions.

- Seek feedback: Get feedback from your supervisor, colleagues, or peers to ensure that your research questions are relevant, appropriate, and meaningful.

Examples of Research Questions

Some Examples of Research Questions with Research Titles:

Research Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health

- Research Question : What is the relationship between social media use and mental health, and how does this impact individuals’ well-being?

Research Title: Factors Influencing Academic Success in High School

- Research Question: What are the primary factors that influence academic success in high school, and how do they contribute to student achievement?

Research Title: The Effects of Exercise on Physical and Mental Health

- Research Question: What is the relationship between exercise and physical and mental health, and how can exercise be used as a tool to improve overall well-being?

Research Title: Understanding the Factors that Influence Consumer Purchasing Decisions

- Research Question : What are the key factors that influence consumer purchasing decisions, and how do these factors vary across different demographics and products?

Research Title: The Impact of Technology on Communication

- Research Question : How has technology impacted communication patterns, and what are the effects of these changes on interpersonal relationships and society as a whole?

Research Title: Investigating the Relationship between Parenting Styles and Child Development

- Research Question: What is the relationship between different parenting styles and child development outcomes, and how do these outcomes vary across different ages and developmental stages?

Research Title: The Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Treating Anxiety Disorders

- Research Question: How effective is cognitive-behavioral therapy in treating anxiety disorders, and what factors contribute to its success or failure in different patients?

Research Title: The Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity

- Research Question : How is climate change affecting global biodiversity, and what can be done to mitigate the negative effects on natural ecosystems?

Research Title: Exploring the Relationship between Cultural Diversity and Workplace Productivity

- Research Question : How does cultural diversity impact workplace productivity, and what strategies can be employed to maximize the benefits of a diverse workforce?

Research Title: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

- Research Question: How can artificial intelligence be leveraged to improve healthcare outcomes, and what are the potential risks and ethical concerns associated with its use?

Applications of Research Questions

Here are some of the key applications of research questions:

- Defining the scope of the study : Research questions help researchers to narrow down the scope of their study and identify the specific issues they want to investigate.

- Developing hypotheses: Research questions often lead to the development of hypotheses, which are testable predictions about the relationship between variables. Hypotheses provide a clear and focused direction for the study.

- Designing the study : Research questions guide the design of the study, including the selection of participants, the collection of data, and the analysis of results.

- Collecting data : Research questions inform the selection of appropriate methods for collecting data, such as surveys, interviews, or experiments.

- Analyzing data : Research questions guide the analysis of data, including the selection of appropriate statistical tests and the interpretation of results.