Content Search

Dec bangladesh: 1998 flood appeal final report, an independent evaluation, attachments.

Roger Young and Associates

FINAL REPORT (1)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ACRONYMS

1. Introduction 2. Methodology and Process of the Evaluation 3. Identification and Analysis of the Assessment Issues 4. Identification and Analysis of the Response Issues 5.Identification and Analysis of Organizational, Management and Special Issues 6. Recommendations

Appendix A.I - Methodological Note on Indicators, Dr. Pat Diskett Appendix A.II - Checklist Appendix A.III - Definitions Appendix B - Sampling Framework Appendix C - List of Persons Met for Discussion Appendix D - Debriefing by Evaluation Team to Dhaka-based Agencies Appendix E - Readings and References Appendix F - Comments on Draft Report by DEC and Funded Agencies Appendix G - Evaluation Terms of Reference

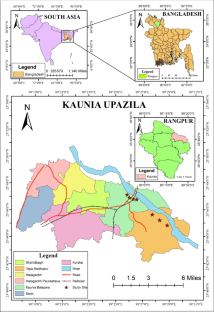

FIGURE 1 Riverbank Erosion and Flood Affected Areas EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

From July to September 1998, Bangladesh suffered the most extensive, deepest and longest lasting flooding of this century. An estimated one million homes were damaged, the main rice and other staple crops were lost due to flooding, and some 30 million persons in 6 million families were affected by the floods.

In mid-September 1998, three weeks after the Government of Bangladesh had approved external assistance to deal with a national emergency situation, the DEC launched a public appeal for aid to those affected by the floods. A sum of £ 3.8 million was raised and distributed to 11 of the DEC agencies best placed to respond to the disaster. The majority had a long-standing history of relief and rehabilitation activities in Bangladesh, working directly and /or through affiliation with local partners.

As a disaster prone country, vulnerable to recurrent flooding, cyclones and drought, Bangladesh has had considerable experience with disaster management. Government and non-governmental organisations have had significant disaster response experience over the past thirty years in Bangladesh, including famine in 1971, floods in 1974, 1987, 1988 and 1998 and cyclones of major proportions in 1971 and 1991.

An independent evaluation of the DEC activities was carried out in September-October 1999 with interviews of DEC agencies in Britain and Ireland, and visits to their offices and/or partners in Bangladesh. The evaluation team met with Government of Bangladesh and United Nations officials as well as with national NGOs, community leaders and beneficiaries. This report represents the findings and recommendations of an independent evaluation of the DEC "Bangladesh Flood Appeal" funded response to the 1998 flood.

The evaluation team was asked to review the effectiveness and efficiency of the DEC "Bangladesh Flood Appeal" funded disaster response, to assess the accountability of DEC agencies using public funds, to assess the value added of DEC funding, and to assess the level of coordination among DEC partners and agencies and other disaster response actors.

Accountability and Value Added

Do DEC funds provide additional funds to agencies and are these funds adequately reported and accounted for?

DEC financing for the Bangladesh flood appeal has provided DEC agencies with additional funds to undertake relief and rehabilitation activities. The scale of the 1998 floods in Bangladesh were so massive and long lasting that the need for humanitarian assistance was far greater than the supply of assistance resources. While many agencies received financial support from their own donors, and used internal finances, they also had to turn to official agencies such as DfID and the European Community Humanitarian Office (ECHO). The DEC financing has been additional to these funds and has permitted agencies to scale-up their relief and rehabilitation activities. There was no evidence that any DEC agency, or donors, had substituted DEC funds for their own financing.

Moreover, some agencies had not been successful in accessing EC and/or DfID funds at the time of the DEC appeal. Therefore, the evaluation team concludes that DEC funds did permit agencies to access funds that were not otherwise available. DEC funds facilitated an estimated 25% additional activities by the participating agencies.

Scaling up has consisted of either a greater coverage of geographical areas or a larger number of activities provided in the rehabilitation phase.

DEC funds are accounted for by the participating agencies in a transparent and accountable manner. The reporting requirements are adequate and include:

- a statement of the agency's competencies and provisional plan of action to be submitted within 48 hours of a formal request to the broadcasters to support a national appeal;

- a more definitive plan of operation to be submitted within 4 weeks of the appeal launch; the agencies' share of funds raised by the appeal is based upon a predetermined distribution formula;

- a final narrative report due in the 7th month following the launch of an appeal, detailing actual operations and including an assessment of the agency's original statement of priority needs, and areas covered, the number of people assisted and a statement of funds received and expended.

Assessment Issues

How well did agencies and partners target vulnerable groups and households when they were assessing and selecting beneficiaries?

Most assessment procedures reviewed by the mission were adequately thorough and careful. Again, this can be attributed to the quality of the contacts with affected communities, since assessments relied heavily on information from partners or staff working in the field.

Several agencies mention that coordination at the local level (involving both government and NGOs) was good enough to enable them to prevent duplication, and/or to target households missed by other schemes.

The most frequently cited criteria for targeting were: households suffering severe loss; landless or assetless households; female-headed households; the elderly and individuals with disabilities. There are indications the effectiveness of targeting declined in that order, with the last category being the most difficult to identify and reach.

Some agencies targeted beneficiaries who were already part of their regular programming, who would not necessarily meet the above criteria for relief and rehabilitation. Others offset this bias by delivering flood relief by area and selecting beneficiaries within those areas with the assistance of village leaders, or local relief committees.

The evaluation team did not have sufficient field exposure to determine whether there were instances of relief going to non-affected or undeserving households. Most agencies did extend their relief and rehabilitation work beyond established target groups and beneficiaries.

For example, one agency that initially concentrated efforts with its eight core partners, provided funds to a further 43 local agencies and used its own staff to work in four severely flooded thanas where it had no partners.

Few agencies relied on local government sources to determine beneficiaries. Many said they by-passed VGF (Vulnerable Group Feeding) card-holders, unless they were sure union authorities had distributed cards only to those genuinely in need.

Some agencies noted that partners tended to direct rehabilitation interventions to their own programme participants, even though their initial relief coverage was more extensive.

Who Benefits from Disaster Responses?

This is a very difficult question to answer with certainty. The resources available to provide relief and rehabilitation could not meet the needs of those affected by the 1998 floods. Damages have been estimated at well over £ 1.5 billion while estimated relief financing from all sources amounted to an estimated £ 600 million. Many needs remain unmet.

Ideally appeal funds would go to those most in need, those most severely affected by the floods. However, assessment of need was imperfect in the context of the floods; homes were submerged and families had abandoned their homes. Many agencies were able to rely on communities themselves to identify the neediest. The evaluation team was told that most disaster relief went to communities affected by the floods, but not necessarily always to the most severely affected people within these communities.

There is some criticism that NGOs in general targeted their own group members disproportionately. Group members who were participating in the well-developed credit and savings programs are known to be among the poor, but not the poorest members of a given community. The most disadvantaged members of a community may not always have benefited from some NGOs disaster response.

Given the scope of this evaluation it is not possible to provide a definitive answer to the question. It would seem that the more effective efforts at appropriate targeting did include consulting local communities. Where the communities are well known to the partners, verification and monitoring that the disaster response was targeted to the most severely affected was more accurate.

To what extent did beneficiaries participate in decisions regarding targeting and activities?

Many of the agencies and their partners followed the participatory approaches used by their development programmes to shape the relief effort. There were quite varied interventions even within the programmes of single agencies, indicating they were reflecting local demands and assessments. Agencies without extensive community development experience were more inclined to deliver their programmes with less regard for community choices.

Examples of planned responses that were altered to meet beneficiary demands include removing unsuitable clothing from foreign relief packages and adding more food; including some cash, ORS, extra oil and women’s sanitary napkins in relief packages.

The rehabilitation phase provided more scope for participatory inputs than the relief phase. The evaluation could not determine to what extent rehabilitation activities - for example housing - were determined by the recipients as opposed to the donors. Many agencies provided rehabilitation inputs as loans not grants, which was maybe based on their own needs or strategies.

Response issues

How well did the elements of relief activities (food, medical aid, shelter, water and sanitation, fodder, etc) match identified needs?

The DEC agencies and their local partners all have considerable experience with flood relief in Bangladesh, and it was not difficult for them to determine what was required and develop the appropriate procedures for delivering it. The mission did not learn of instances where relief packages contained superfluous goods or were missing essential goods, though there was wide variation in proportions and contents.

Several agencies reported they were able to deliver services, such as medical aid, which they did not normally provide, by hiring temporary staff or getting outside assistance. Some assigned head office staff to strengthen local capacity or to help manage coordination and monitoring.

Throughout Bangladesh there was a widespread mobilisation of volunteer assistance during the 1998 floods. The DEC-funded organizations also benefited from this response, getting help from the public or from their own networks.

Some agencies reported the supplies of relief goods in the affected areas were more than adequate. This meant local officials and politicians were less likely to commandeer or divert supplies. The local availability of relief supplies did contrast with the overall shortage of relief materials in a national context.

With a few exceptions the DEC agencies reported they were able to procure what they planned to distribute and to handle the logistics of distribution. Shortages of non-grain seeds appeared to be the principal procurement problem. Some complained there were cash flow problems caused by the banks’ poor system for transferring funds to branch offices.

To what extent was standardisation an issue?

Although the basic list of requirements for both relief and rehabilitation were similar, there was no standardisation of the proportion of these in each overall package, nor was there much standardisation of the amount or design of the separate elements (e.g. in the size or content of food packages or the type and cost of houses). Different agencies did different things, based on organisational priorities, skills of their partners or policy decisions, given the available funds.

There is a continuing debate over whether rehabilitation disbursements should be grants or loans. There is a wide variation among the agencies on handling this choice. There is also variation on loan terms, and the disposition of funds made available from loan recovery.

Did the response activities build on lessons learned from past flood disasters?

There is general consensus that disaster relief was handled better for the 1998 flood than for the severe flooding ten years before in 1988. One crude indicator of this is the much lower fatality rate (1,376 in 1998 compared to about 6,000 in 1988).

There are some interesting comparisons to the findings of an ODI evaluation of the 1988 flood relief:

- the 1988 report noted the housing interventions varied widely in design, cost, etc. This is still the case in 1998.

- the 1988 report found the response was very top-down and there was little community-level participation. This appears to be less of an issue in 1998.

- the 1988 report criticised the continuity and effectiveness of local coordination efforts. In 1998, DEC agencies were quite positive about the adequacy of communications, preparedness, and government-NGO cooperation.

Effectiveness

Agencies that implemented effective relief and rehabilitation activities demonstrated the following competencies:

- effective disaster preparedness, both of the agency and its partners through recurrent training, and disaster manuals; also a preparedness of communities through prior and recurrent training, facilitating mechanisms to foster cooperation and community action at the time of the floods;

- efforts to assess specific needs, and the degree of deprivation; this was especially difficult in a context where many were in need of humanitarian aid, living on rooftops or had had to abandon their homes for flood shelters;

- an ability to coordinate agency efforts with other actors, including government at central and local levels, UN organizations and other NGOs to ensure that duplication of effort was minimised and that relief and rehabilitation activities were directed towards the most severely affected communities.

Cost effectiveness

There are several important examples of cost effective initiatives undertaken by the DEC agencies and partners. Three examples are cited here:

- the use of NGO partner agencies, to extend the reach of the disaster response was an initiative taken by the majority of DEC agencies, as a result of lessons learned in the 1988 flood; this allowed agencies to reach more people in need at lower costs than establishing their own programmes;

- a nutritional assessment carried out by one agency to assess the nature and extent of malnutrition, especially in children. This survey served to provide accurate and timely information that also allowed other agencies to develop appropriate food packages and targeting. With limited food resources to distribute, this rapid survey proved effective and informed several agencies' responses.

- the construction of flood shelters for humans and livestock; with relatively modest costs for construction, these shelters permitted families to access shelter and a place to save their livestock, an essential asset for rural poor families.

Organization and Management Issues

Did the 1998 experience build on, or improve, coordination mechanisms among organizations providing relief, at the local and national level?

One good example of coordination was the sharing of the nutrition survey results, which led to modifications in plans and interventions for food relief. This led the agency itself to reduce its draw on the DEC funds.

Some thought the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) was late in declaring an emergency but there was little subsequent complaint about the government’s role in coordinating the relief efforts. Compared to the 1988 floods (when there was no NGO Affairs Bureau) the government did not unduly delay NGO plans or withhold approval for specific activities; although, a few agencies complained that approvals for rehabilitation work through the NGO Bureau were delayed, compared to approvals that were provided for work in the relief phase.

Perhaps the most important lesson communities have learned from previous disasters is that they can influence what happens in a disaster effort delivered by government and non-government bodies. People have not only developed concepts of their right to be provided with relief and rehabilitation but also of the value of doing something for themselves. The extent of public participation and volunteerism was very impressive in the 1998 flood disaster. The scale and intensity of the 1998 flood and the reduced loss of life relative to previous floods suggests that the people have highly developed capacities to cope under difficult circumstances. The general public has also learned the importance of safe drinking water, as demonstrated by the widespread use of tubewell water, even during the height of the flooding.

The Mission concludes that there was adequate coordination among government and non-governmental actors during the flood response. As a result of this coordination, duplication of relief and rehabilitation efforts was for the most part, kept at minimum levels. On the whole, those who most needed relief and rehabilitation efforts were provided for, although to varying extents.

One key coordination forum for DEC agencies was the Disaster Forum, a body that brought all the major actors together in the 1998 flood response. At the national level, the NGO association ADAB, and the government's NGO Affairs Bureau were also coordinating NGO activities. DEC agencies believe these were useful in directing activities to areas of need. Government efforts at relief and rehabilitation were coordinated through the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief and its operational body posted at District level, the Disaster Management Bureau. Most observers believe that the newly established Disaster Management Committees at the local level, comprising government officials, NGO representatives and locally elected officials operated adequately to coordinate the disaster response.

At the local level, all relief and rehabilitation activities were centrally authorised by government, through the approval of the Master Role by the TNO (Thana Nirbahi Officer or chief local official) at thana level coordinating committees made up of government officials and NGO representatives. NGOs were able to monitor government relief efforts and to negotiate with officials where abuses were present. Several DEC agencies worked together at the local level to ensure effective coverage, sometimes in areas where no other organisations were working.

Future Coordination Issues

Given the extensive experience of the DEC agencies collectively in disaster response in Bangladesh, there is an opportunity to document and exchange individual agency policy and implementation around specific activities, related to disaster preparedness and response. The following is a partial list of themes or issue areas that would benefit from further coordination among DEC agencies, by reviewing their experiences from the 1998 flood response:

- Disaster preparedness and management - collectively, DEC agencies in Bangladesh have a wide experience of disaster preparedness and management, including the capacity to build a response approach at community level. DEC agencies themselves, have varying degrees of capability and priority. Agencies could share this knowledge and develop mechanisms to strengthen partners' preparedness and organizational capacity for disaster responses.

- Targeting and coverage - agencies recognise the complexities surrounding appropriate targeting and ways to reach more of the most severely affected persons in a disaster; several initiatives and innovations by DEC agencies could be documented and reviewed.

- Housing - given the extensive damage to housing during the flood and the wide variety of housing rehabilitation offered by agencies, it would be useful to document these experiences with a view to developing guidelines of appropriate housing interventions specific to different geographical locations, different types of disaster and varying community preferences; standardisation is not desirable but some greater uniformity in practice for similar situations would be feasible.

- Loans, Grants, Local Disaster Funds, Emergency Replacement Funds - agencies had different policies and approaches to the use of grants or loans in the rehabilitation phase. Some loan funds are being used to develop future disaster funds for communities while others are being used to provide emergency credit funds for partner agencies. As this area of response is a new and somewhat uncharted ground for most DEC agencies, the donating public deserves further documentation and assessment by DEC agencies.

As a disaster prone country, vulnerable to recurrent flooding, cyclones and drought, Bangladesh has had considerable experience with disaster management. Government and non-governmental organisations have had significant disaster response experience over the past thirty years, including famine in 1971, floods in 1974, 1987, 1988 and 1998 and cyclones of major proportions in 1971 and 1991.

The evaluation team has therefore come to expect a degree of professionalism, preparedness and coordination among the DEC agencies that may not be appropriate in other emergency contexts currently being confronted by these same agencies. Our standards for the Bangladesh evaluation have been set high.

Disasters are by their nature dynamic and this was also true of the 1998 Bangladesh floods. The 1998 flood was more extensive and longer lasting than any other in recent history. Although some agencies were alerting government and their UK-based head offices of the potential scale and damage from the flooding as early as mid-July, the Government and official agencies were slower to recognise the enormity of the floods. The Government of Bangladesh requested official external assistance at the end of August 1998, after some districts had been flooded for over seven weeks.

By the time of the DEC ‘Bangladesh Flood Appeal’ in mid-September 1998, many of the most vulnerable communities living alongside the major river systems in Bangladesh had been flooded for over two months.

The flood waters had begun to recede, albeit slowly, by the third week of September. Agencies in Dhaka began to receive funds from the DEC in mid-October, after initial search and rescue and feeding programmes had been completed. By this time, full and supplementary feeding, health and nutrition, while still priorities were waning in importance. The medium term priorities were to rebuild lost housing and to ensure that families had access to employment opportunities and an ability to grow and/or to buy food.

DEC agencies responded to the floods with a variety of activities, summarised in Table 1. Relief activities account for about a third of DEC financing, largely to cover feeding programmes in rural and urban areas. The majority of funds were used to finance programmes in the rehabilitation phase, with activities to ensure livelihoods for affected people including housing, work programs, cash grants and agricultural inputs.

BANGLADESH FLOOD APPEAL 1998/99 DEC AGENCY EXPENDITURES BREAKDOWN by ACTIVITIES

(Figures expressed as a percentage of expenditures)

BANGLADESH FLOOD APPEAL 1998/99 AGENCY TOTAL DISBURSEMENTS AND DEC PROPORTION

Source: DEC Agency reports Notes:* does not include £ 728,736 food security grant approved but not received as at 10/1999.

2.0 METHODOLOGY AND PROCESS

The DEC requires an independent evaluation of its 1998 Bangladesh Flood Appeal funds. The evaluation should assess the appropriateness and effectiveness of the activities financed by the appeal. This evaluation was undertaken in September-October 1999.

The terms of reference for the evaluation request the evaluators to review the following issue areas:

- The transparency and accountability of agencies undertaking relief and rehabilitation activities;

- The effectiveness of agencies in achieving the stated goals of their planned activities;

- Given the disaster prone nature of Bangladesh, to assess the extent of disaster preparedness by agencies and local communities;

- The coverage of relief activities, the assessment and identification of need and the appropriate target group;

- The extent to which lessons from previous disaster relief have been incorporated;

- The effectiveness of coordination efforts by agencies and with the Government of Bangladesh.

Secondly, the issue of how to attribute DEC financing to specific activities had to be confronted. DEC funds allowed agencies to scale up their response efforts. An audit, per se, would tell us little.

The evaluation team, in consultation with the DEC, decided to address the terms of reference for the Bangladesh 1998 appeal through a review of existing documentary evidence, as provided by agencies to the DEC under current reporting requirements. The documentation review was complimented by a series of comprehensive interviews with DEC agencies, at head office in the UK, as well as in their Dhaka offices and field centers.

The purposes of the interviews were to:

- Seek agencies views regarding the key lessons learned in the 1998 flood response;

- Elicit additional information and documentation on preparedness, needs assessments, targeting and coverage of activities in light of the most severely affected communities and regions;

- Understand the rationale for, experience with and use of partner agencies to implement the majority of the response;

- Understand the rationale for the response of each agency to the floods;

- Review coordination and collaboration among DEC agencies, the larger NGO community in Bangladesh and with the Government of Bangladesh and UN agencies.

The evaluation team met with representatives from the Government of Bangladesh directly responsible for disaster management, UN agencies and large national NGOs, that had been directly involved in the 1998 flood response. The team met with local representatives of official donors from DfID and the European Community , which had provided additional financing to many of the DEC agencies.

The team developed a field trip plan to visit a severely affected riverbasin area along the Jamuna river system. The visit to Jamalpur district was intended to allow the team to observe directly a number of flood proofing initiatives of DEC agencies, to meet a sample of partner agencies and to meet local officials and beneficiaries in this area.

Due to security problems at the local level this field trip was cancelled at the last moment, and an alternative trip to Chawhali thana in Sirajganj district, an equally flood prone char area (sandy strips of land, usually deposited along rivers as a result of upstream erosion), set up. Given the last moment arrangements, it was not possible to meet as many partners as originally planned. The other observations and interviews however were still possible, albeit in reduced form.

A briefing was held with representatives of the local DEC agencies and some partners at the outset of the Bangladesh part of the evaluation process and a debriefing with these same representatives at the end of the field-based work. A briefing for UK-based agencies was held to discuss the preliminary draft of the report.

The evaluation team consisted of five consultants. As team leader, Roger Young coordinated the evaluation process, conducted the interviews in the UK and participated with the interview and assessment team in Dhaka. Dr. Pat Diskett of the Cranfield Centre for Disaster Management provided a set of guidelines to the team on evaluation methodology in the context of relief and rehabilitation. (See Appendix A). Carol Eggen participated in the interviews in Dhaka and contributed to the assessment of lessons learned. Dale Posgate participated in the field review and contributed to the overall analysis. Aziz Siddique developed the sampling framework for the field-based review.

The purpose of this evaluation is to provide DEC and its constituents with a summary review of the appropriateness and effectiveness of the DEC funded response to the 1998 flood and to identify any strengths and weaknesses that could inform future DEC-funded initiatives.

Thus the evaluation focused on analysing the process and the results of the DEC-funded activities. Since each agency has provided narrative reports on their activities, the evaluation report will not describe these in any detail.

This analysis raises some issues about the response and its implementation and elicits lessons learned for the DEC and its constituents. The issues discussed below are some, but given the mission’s scope, not all, of those that consistently arise in the disaster relief process. The issues raised are not meant to indicate that the DEC experience in the 1998 floods was especially problematic.

The analysis necessarily generalises from the experience of the several agencies and numerous partners involved, recognising there was considerable variance among these in the scope and quality of their activities. The issues fall under three headings, relating to "assessment", "response" and "organization and management".

3.0 IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF ASSESSMENT ISSUES

3.1 Targeting Areas

The 1998 flood affected 51 out of 64 districts. Districts that were closer to the three major river basins were most seriously affected by the flood, both in pervasiveness and intensity. Within each district, villages in particular low-lying unions and wards were more severely affected.

DEC agencies worked in 49 districts but the pattern of their disaster response coverage was somewhat dependent on the organisation’s history, constitutional framework, development mandate and field presence for regular programming in Bangladesh (see Figure 1 and Appendix B).

Agencies receiving DEC funds worked in a variety of ways to implement the 1998 flood relief and rehabilitation programme. Many DEC agencies worked through partner NGOs or local groups for the delivery of services during the 1998 flood. Agencies such as CARE and Oxfam, which have routinely been active in disaster management over the years, had pre-selected NGO partners with a field presence in disaster locations, such as the cyclone belt or the flood plains along particular river basins. Several agencies receiving DEC funds (BDRCS, CARE, Caritas) were able to utilise their own implementation capacity at extensively spread regional and district offices throughout the country. Several agencies implemented the 1998 flood programme through a combination of direct delivery through their own staff and support to NGO partners. The following is a summary of implementation systems:

- BDRCS - delivered through their District Committees, Squads, volunteers and own staff;

- Caritas (Cafod) and World Vision - mostly delivered through their own staff with a few partners;

- CARE, Concern, HEED (Tearfund) and Koinonia (Tearfund) - delivered both directly and through support to NGO partners and local groups;

- Oxfam, Christian Aid, SCF and ActionAid - disaster responses were delivered through NGO partners, (including their staff, volunteers and community groups) with their own staff used for monitoring and supervision;

- Resource Integration Centre (HAI) - delivered directly, as a partner NGO with CARE;

- Dhaka Ahsania Mission (Cafod) - delivered directly, through their community volunteers from literacy centres.

3.2 Targeting Beneficiaries

There was considerable variation on the selection of beneficiaries for relief and rehabilitation services during the 1998 flood. All relief and rehabilitation issues were centrally authorised by government, through the approval of the Master Role by the Thana Nirbahi Officer (TNO) the senior local government official and the thana coordinating committee made up of government officials and representatives of NGOs at the thana level. Although all agencies had attempted to ensure distribution to the most affected, the most vulnerable and the poorest, there were a myriad of factors that influenced those selections. These included the influence of local government officials, familiarity with local communities from previous programming and the proximity of the community to road and river transportation.

The evaluation team concludes that good practices for accurate beneficiary selection include the following:

- Agencies that had worked on disaster preparedness were in the best position to effectively select beneficiaries because they were able to:

- understand what needed to be done, in light of the scale of operation;

- define the criteria to be used to select the "most" of any classification;

- determine methods for selection;

- implement and monitor selection.

- Agencies that had pre-selected partner NGOs for disaster-based relief and rehabilitation had usually provided their partners with up-to-date training and guidelines in beneficiary selection.

- Agencies whose regular programming was based on well-developed, socio-political knowledge were able to provide their field staff and partner NGOs with the analytical capability needed for accurate beneficiary selection in rural Bangladesh.

- As beneficiary selection or self-selection became less obvious during the rehabilitation stages, agencies reported difficulty in the management of beneficiary selection. Concern developed effective household needs assessments and trained their partner NGOs in short, but precise survey methods to control for beneficiary selection when the demands were great from all sides.

- Most agencies reported that they were less able to control beneficiary selection when partner NGOs were involved in distribution of disaster services because each NGO had their own client groups, served with specific programmes and located in specific areas. Although NGO partners also work with the poor in their regular programmes, the nature of a savings and credit programme does not mean that the poorest people are necessarily part of their groups. Nor does the provision of a regular development programme in one union of a district necessarily mean that a partner NGO has the local knowledge necessary to select beneficiaries in another, flood-affected union of the district.

4.0 IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF RESPONSE ISSUES

The DEC agencies and their local partners all have considerable experience with disaster assistance in Bangladesh and in principle, they knew what was to be done.

4.1 Search and Rescue

In deeply flooded areas, the accessibility of high land was critical to the survival of people and livestock. Traditional building practices in rural Bangladesh include the provision of earthen plinths for the house, as well as the homestead compound. The height of the plinth and the amount of earth to be raised varies, according to the homestead’s location on the flood plain and the resources of the household.

In a regular monsoon flood, economically secure households will be able to remain in their home, even though during the peak of the flood they may have to live for a few days on raised bamboo plinths within the house. Households with cattle, straw and grain stores are particularly reluctant to leave their compound during a flood. Poorer households without high land or in cases of river erosion, without homesteads, often take refuge in the compound of wealthier relatives, school compounds, market places or on thin strips of high land alongside roads, railways or embankments.

In the deepest flooded areas, across the country, there was very little high land left for either rich or poor households. During the height of the flood, thousands of households along with their poultry and livestock, had to be moved from the tops of their house to flood shelters on high land. Only a few DEC agencies that had high levels of disaster preparedness were able to mobilise boats for search and rescue operations.

4.2 Food Assistance

Food distribution was a highly demanded and appropriate activity during both the relief and rehabilitation phases of the Bangladesh flood response. Seven of the 11 DEC agencies provided some form of food aid, accounting for 29% of the total DEC expenditures.

The actual food package or rations distributed depended on the phase of the flooding and the resources available to individual agencies. Beneficiaries may have received dry food, such as high protein biscuits, or cooked food, when and where people had no access to fuel to cook a meal, during the initial relief phase.

Later in the disaster, agencies began to distribute food packages consisting of some combination of rice, pulses, cooking oil, salt and in some cases cash to buy other items in the market.

The actual quantity of food items varied among the DEC agencies and reflected a policy decision on how many families to feed, given a certain quantity of food available. In discussing this with agencies, the Mission team is satisfied that individual agency decisions were well informed and reasonable in the circumstances.

4.3 Flood Shelters

DEC agencies reported a variety of circumstances in which flood shelters were arranged. The most successful cases occurred when partner NGOs had been engaged in disaster preparedness with community participants. In flood-prone areas along vulnerable river basins, trained village committees were able to quickly locate suitable high land and NGO partners provided the labour costs (under cash-for-work programmes) to raise the land and create a flood shelter. Some village committees were so well prepared that they had maps of their locality to indicate the location of the most distressed households, either by the type of occupant (elderly widow, female-head) or by its location in relation to high land.

Village committees who could arrange for flood shelters with adequate space for livestock were able to convince rural households to move before the last moment. Built for the 1998 flood, Oxfam demonstrated that the value of cattle saved on a flood shelter of approximately 4 acres was as great as tk 4,000,000 (Stg 150,000) against a construction cost of only tk 700,000 (Stg 8,560).

The Mission concludes that the use of flood shelters, which provided enough space for families, parts of their house, their belongings and their livestock was highly effective in not only saving lives but also in retaining some degree of economic security of households in the post-flood period.

4.4 Sanitation and Clean Drinking Water

Submersion of sanitary latrines and lack of access to toilets was a major problem during the prolonged flood of 1998. The health risks were more acute in congested urban areas than in rural areas where the concentration of faeces was reduced by larger bodies of water. Beneficiaries reported that the sanitary toilets provided for women and men at centralised locations, such as flood shelters and relief centres were greatly appreciated.

The provision of clean drinking water was a problem of major proportions. In Dhaka, CARE and the municipal water authority operated a large-scale programme to transport and distribute clean drinking water to residents in deeply flooded areas.

Tubewells are the common source of drinking water in the rural areas and over the past 10 years the general public has developed a high level of awareness about the need for clean drinking water. In the beginning of the flood, agencies promoted the practice of raising tubewells to prevent contamination from rising flood waters. As the flood progressed and tubewells became submerged, people waded through floodwaters or hired boats to obtain water from tubewells on high ground. One of the most essential services provided by flood shelters was access to clean drinking water and toilet facilities.

With the rural population almost entirely dependent on firewood for domestic use, there was no fuel accessible to purify water through boiling. In an attempt to provide clean water at household level, agencies distributed bleaching powder, buckets and plastic water containers, as part of the relief package. Agencies did not widely distribute water-purification tablets because beneficiaries reported such water to be distasteful and laboratory tests done at ICDDR,B indicated that the tablets available were of limited effectiveness. Finding that the scale of impure drinking water could not be addressed by purification measures, agencies promoted the wide-spread use of rehydration salts, distributing ORS packets with the relief supplies and mobilising thousands of volunteers in all parts of the country to prepare and package ORS. As the floodwaters receded, many agencies provided bleaching powder and technical advice on the cleaning and rehabilitation of tubewells.

Some agencies reported their concerns about the requirement for water consumption with some of the food items that were distributed, i.e. the flattened rice known as cheera. It was felt by some agencies that certain foodstuffs such as high protein biscuits, was a better alternative because they required less water for consumption.

Based on the request of beneficiaries, a number of agencies used DEC funds to provide health services. The general public feared there would be major outbreaks of disease in congested areas where there had been an absence of potable water and sanitation facilities and a prolonged exposure to stagnant water. Several agencies delivered an inclusive health programme based on the linkages with water, sanitation, nutrition and health education, while other agencies provided a traditional health programme that was simply curative.

Curative treatment was provided mainly for diarrhoeal diseases, acute respiratory infections and skin conditions. Depending on the need, agencies provided curative treatment from stationary and mobile clinics. In deeply flooded areas, treatment was provided from boats. Paramedics making home visits from boats were more effective than the actual provision of treatment from a boat.

Treatment by paramedics who were local tended to be more effective than teams of medical doctors who were sent to rural areas. NGOs with experience in health programming tended to mobilise trained paramedics and provide them with treatment guidelines and standardised essential medicines. Paramedical health teams familiar with people’s local conditions provided more effective treatment than teams of medical doctors sent in from outside the locality, and who tended to over-prescribe.

Several agencies reported the effective use of government health clinics for their referred patients, particularly because there was increased medical staff available during the flood. Agencies which reported that government health services were ineffective tended to lack previous working relationships with thana-based health centres or the capacity for follow-up home visits through their own paramedic staff.

Essential medicines were provided free of charge and in many cases, ORS was provided as part of the food ration. Inclusion of antibiotics in the food ration was not considered to be a good practice because such blanket coverage was both wasteful and risky when severe medical conditions were masked. An outbreak of measles was recognised and reported by one agency, which was then able to mobilise government immunisation services.

4.6 Nutrition

Several DEC agencies were particularly concerned with the nutritional status of children, pregnant women and lactating mothers during the 1998 flood. The minimum nutritional value for the food ration was also dependent on understanding the national nutritional status during the flood. Variations are known to occur during different flood stages, as well as in different geographic locations where vulnerable populations have been mapped against food scarcity. To gain an overall understanding of children’s nutritional status, SCF conducted a rapid survey in selected areas of the country in September 1998.

This study, provided to NGO partners and other agencies, indicated that although vulnerable populations and areas showed a nutritional status diminished to 1996 levels, the nutritional status for children of the general population was not as severe as had been anticipated. The validity of SCF’s rapid nutritional assessment was acceptable when cross-checked with the nation-wide nutritional survey carried out by Helen Keller International. To monitor the long-term effects on poor children of the loss of family assets and livelihoods in the flood, SCF has conducted follow-up nutritional surveys in December 1998 and in August 1999.

4.7 Housing

One of the major components of the 1998 flood rehabilitation programme was housing. Following life and food security, beneficiaries considered housing to be their next priority and the expenditure of DEC funds for housing reflects this response to beneficiary demand (food 29%; housing 19%).

Yet there is wide range of variation in the response of DEC agencies to the need for shelters and housing during the 1998 flood. Such variations appear to be reflections of:

- the type of beneficiaries who were being provided with housing;

- differing geographical areas (flood plains, flood banks, cyclone-prone) have different needs and require different housing interventions;

- different demands for shelter and housing in the relief and rehabilitation periods;

- the use of the participatory process with communities and householders in house design, construction and cash and kind contributions;

- the experience of agencies in disaster housing;

- the capacity of agencies to distribute and monitor inputs to housing;

- the development philosophy of agencies.

During the rehabilitation period, several agencies provided materials for beneficiaries to replace a house with basic upgrades such as reinforced cement concrete (RCC) pillars and a double roof (to prevent dislodging of tin sheets during a high wind) at a cost of approximately taka 6,000 (£ 75). Beneficiaries supplied all labour costs including the raising of the earthen plinth above flood levels. Another agency that provided cash for housing, asked for repayment of 50% of the fund, which was then utilised to repair the community’s literacy centre, damaged in the flood.

Several agencies that have experience in housing have taken policy decisions that they will no longer distribute free houses, even to disaster victims. When faced with difficult economic choices, poor families often have to sell their houses and are some of those who again have to be supplied with housing during the next disaster. Even with agreements signed with the agency and monitored at Union Council level, beneficiaries have been reported to sell the materials from their freely obtained house. Although Caritas has a policy for free housing, in the next round of housing to be provided, most beneficiaries will be asked to pay 30% of costs and this money will be invested in some form of future disaster fund. Extremely poor families, such as female-heads of household will be exempted from payment. HEED provides houses at cost and beneficiaries are provided with a 5-year period for repayment on a monthly basis.

Several agencies with experience in low-cost housing constructed particular ‘disaster-proof’ houses that cost between tk 13,000 and tk 15,000 (£ 165.and £ 180). Such houses were specifically designed to:

- withstand decay from prolonged water immersion (in flood-prone areas);

- to secure a tin roof during high winds (in tornado-prone areas);

- require low maintenance and annual repair (for hard-core poor and female-headed households);

- be environmentally conservative (wood scarcity in Bangladesh).

- the 1988 report noted the housing interventions varied widely in design, cost, etc. This is still the case in 1998;

- the 1988 report found the response was very top-down and there was little community-level participation. This appears to be less of an issue in 1998;

- the 1988 report criticised the continuity and effectiveness of local coordination efforts in housing. In 1998, DEC agencies were quite positive about the adequacy of communications, preparedness and government-NGO cooperation.

Some questions for consideration are:

- repair, replacement or improvement?

- portable vs permanent design?

- cash or materials?

- procure materials or engage in production?

- grants or loans? (and terms of loans)?

- ownership and legal title?

- high-cost units for a few, or low-cost units for many?

4.8 Vegetable Seeds

Vegetable seeds were provided by many agencies in the immediate post-flood period. Seed packets mostly consisted of 5 to 7 nutritious varieties that were quick-growing in muddy conditions and suitable for plantation on small homestead spaces. Vegetable seeds were distributed free of cost and often to women who were involved in post-flood child nutrition or ‘cash for work’ programmes. There was great demand for this input and several agencies reported difficulty in obtaining adequate quantity and quality of vegetable seeds.

The Mission concludes that the distribution of vegetable seeds was a highly appropriate and cost effective activity with high, short-term returns to beneficiaries.

4.9 Agricultural Rehabilitation

DEC funds were used to provide crop seeds in the late rehabilitation period. Agencies reported that beneficiaries for this input were small farmers, owning less than 1.5 acres. The combination of seeds often consisted of rice, wheat, potato and pulses. In some cases seeds were freely provided, while at other times beneficiaries paid a portion of their costs with the returned funds being deposited in disaster funds for community use.

DEC being flexible in the use of funds meant that one agency was able to use DEC funds to purchase badly needed vegetable seeds in time for the first planting after the floods. Funds promised from an official donor for the purchase of crop have yet to arrive near the end of 1999!

4.10 Cash Grants, Interest Free Loans and Micro-Credit and Disaster Funds

In the immediate post-flood period, there was a great need for beneficiaries to have capital both for consumption and to re-gain productive assets that were lost in the flood. In DEC-funded programmes there was wide variation in the way that beneficiaries were provided with funds in the rehabilitation period. The use of loans in rehabilitation activities is a relatively new phenomenon in Bangladesh and it is not surprising that policies and practices of the DEC agencies with regard to the use of grants or loans (and the terms of loans) are not consistent.

In some cases, grants were provided for beneficiaries to purchase rickshaws, boats and livestock. In some cases interest free loans were provided for agricultural production under ‘soft terms’ that included a long period for repayment of principal. In general, there was a tendency to issue soft loans with subsidized principal and/or interest and grace periods, rather than to follow the terms of current micro-finance practices in Bangladesh.

In other cases, loans were provided under the same terms as regular micro finance programmes. The provision of loans to groups of landless and poor women is a primary activity for many NGOs who were involved with the 1998 flood. Many of the beneficiaries for the relief and rehabilitation programme were those groups who receive micro-credit as part of normal programming. In the present development work, funding agencies have encouraged most NGOs to strive for self-sufficiency in their micro-credit programmes, through the collection of interest on their loans. Because of the beneficiaries’ massive loss of assets and income-earning capacity following the flood, ADAB placed a 3 month moratorium on the collection of loans. This resulted in a heavy loss for NGOs running micro-finance programmes and although large NGOs could afford not to collect interest payments for 3 months, many small NGOs found this loss of income placed their organisation in an economically vulnerable position.

In the months following the moratorium on micro-finance, large NGOs have subsequently received donor funds to re-finance their credit programmes. Several DEC agencies have also provided grants to their partner NGOs to allow them to resume their micro-credit programmes upon completion of flood relief and rehabilitation activities. In several cases, the capital and interest in soft loan programmes is being utilised to form disaster funds.

The mission concludes that DEC agencies need to document this experience and discuss if and how funds are best used in the form of grants, soft credit, micro-finance credit and disaster funds. This is not to propel the DEC agencies into the debate over the value of credit as a development tool but to give DEC a better ground for assessing proposals and their implementation. The following questions need to be considered by DEC agencies at headquarters and in Dhaka:

- are they satisfied that it is appropriate to disburse funds designated for relief and rehabilitation in the form of credit?

- does the use of funds for loans, as opposed to grants, conform with the expectations of the donating public and the tenor of its fund-raising for people in distress?

- if credit is a good idea, should there be some consensus to reduce the variance in terms that they are applying to the loans?

- should there be a consensus on how the money recovered from lending is utilised (for example, to capitalise emergency preparedness funds)?

- is there any concern that relief in the form of soft loans is undermining the integrity of their and others’ micro-finance portfolios?

- is it appropriate (in terms of skills, resources and relationship with their beneficiaries) for partners who are not normally in the micro-finance business to operate a loan scheme on a short-term ad hoc basis?

- does the DEC require more detail in submitted proposals on terms of lending and the disposition of recovered funds? (Most proposals do indicate which activities will be based on loans rather than grants but few of them describe the terms or how the loan funds will be managed in the future).

4.11 Cash for Work

Immediately following the relief stage, agencies used DEC funds in cash for work programmes, as a means of providing beneficiaries with income for household consumption needs, as well as to regain productive assets. Beneficiaries’ labour was utilised for a variety of repair work for schools grounds, roads and market places. In some instances, the cash for work programme was done by using earth cut and carried to raise building sites above flood levels. Beneficiaries are reported to have preferred ‘cash for work’ to ‘food for work’ because cash provided them with greater expenditure choices and avoided delays in having to monetise the wheat. Agencies reported that ‘cash for work’ programmes needed to be stringently monitored to avoid loss in the distribution process.

4.12 Flood-Proofing

As a result of the successful use of flood shelters during the 1998 flood, several DEC partners have supported village committees to undertake such construction for future disasters. Utilising the labour opportunities provided under cash-for-work programmes, village committees have arranged for raised earthen platforms to be constructed on such common property as school compounds and market places. In some communities along the vulnerable river basins, Oxfam, Concern and ActionAid, along with their NGO partners are working with poor households to re-locate on flood-proof land. Individual or clusters of households are being assisted to either purchase land or to obtain government khas land for the construction of high earthen platforms. Village people have eagerly contributed portions of the labour costs and the housing materials. Such constructions will provide life and property security in disasters of either deep flood inundation or river bank erosion.

The Mission concludes that in view of the recent flooding pattern in some river basins (1987, 1988, 1991, 1995, 1996 and 1998), flood-proofing for vulnerable households is a highly effective use of DEC funds, utilised in the rehabilitation period.

5. AN IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF ORGANISATION, MANAGEMENT AND SPECIAL ISSUES

5.1 Disaster Preparedness and Management

Agencies all reported that the key to effective disaster management lies in disaster preparedness. That being the case however, the degree and type of disaster preparedness in the 1998 flood varied greatly among agencies receiving DEC funding. This is to be expected, considering that more than 50 core partners were involved and, with the exception of BDRCS mandated to serve during disaster, that all agencies operate development programmes in Bangladesh.

Agencies who had incorporated "lessons learned" from the 1988 flood and the 1991 cyclone had taken steps towards disaster preparedness. Agencies such as Oxfam and CARE had well-developed Disaster Preparedness Units. In other agencies, the preparation of Disaster Preparedness Units was a "work in progress". Having made a policy decision to work with partner agencies, Concern had only selected their partners in May of 1998, while ActionAid were in the process of developing the response capacity of their partners when the floods began in July. Several agencies that had intended to be prepared after the disasters of 1988 and 1991 had been caught up with other organisational priorities and had neglected attention to routine training and up-dated disaster guidelines. Several organisations reported that at the time of the 1998 flood, their response capacity was diminished because of policy, management and administrative changes occurring either at their head office or in Dhaka.

Seen from a collective perspective, however, DEC agencies have a wealth of experience in disaster preparedness and management. The 1998 flood has provided further opportunities for agencies to sharpen their perspectives.

The evaluation team concludes that in varying degrees, the DEC agencies have knowledge and experience of the following issues related to disaster preparedness and management:

- the need for effective flood-warning systems and the wide dissemination of that information;

- regional collaboration in disaster management;

- the use of maps to target benefits to flood basins and flood plains;

- communication systems with remote disaster areas;

- the pre-selection, contracting and training of core NGO partners;

- the value of up-dated and widely accessible flood disaster guidelines;

- the preparation of vulnerable communities in disaster action planning;

- the use of cash-for-work programmes to develop community-based flood-proofing;

- the use of needs assessment and household survey in beneficiary selection;

- methods of negotiation with local power brokers to enhance the distribution of benefits to the poor and vulnerable;

- the mobilisation and effective use of volunteers, local committees and women elected members in disaster relief;

- the development of stores and disaster supplies in accessible locations;

- the value of centralised, data-bases to provide rapid accessibility to such information as local resources, shelters and information routes;

- the value of working in collaboration with government agencies such as the Ministry of Disaster Preparedness and Relief and the administration at District and Thana levels, as well as the NGO Bureau and the BWDB Flood Forecasting Centre in Dhaka;

- the value and use of networking with agencies specialised in disaster preparedness and management, such as the Disaster Forum and others;

- the use of informal committees under DEC agencies, such as Christian Aid who were able to collectively plan and accumulate knowledge leading to effective implementation.

5.2 Accountability, Management and Reporting

DEC reporting requirements, which consist of the 48 Hour Plan of Action, the 4 Week Plan of Action and a 7th Month Declaration of Expenditure Report provide an adequate basis for a review of an agency's competence to undertake relief and rehabilitation activities in the context of a particular appeal and to control for, report and monitor financial expenditures and operational activities.

After reviewing these reports, the evaluation team concludes there is adequate accountability and transparency in the reporting of the DEC appeal funds to satisfy donors that the DEC funds were used to meet emergency and rehabilitation needs for Bangladesh flood disaster in 1998/1999.

Agencies told the Mission team that the DEC reporting requirements were clear, flexible and reasonable. The DEC funds reached agencies in the field relatively quickly, the first disbursement of funds by October 1998. This relative ease of disbursement allowed agencies to finance planned activities on schedule. In contrast, one agency reported that a planned purchase of high yielding vegetable seeds had to be scaled back because of conditions imposed by EC funding. These delays meant that purchase of seeds could only be made in late 1999, a full year after the required planting time to meet the 1998 flood impact.

5.3 Coordination and Collaboration

Coordination of efforts is important in disaster responses to ensure that duplication of efforts is avoided and to extend scarce resources to those most severely affected by the disaster. Given the extensive and recurring nature of disasters in Bangladesh it is not surprising to find that there is an extensive organizational infrastructure for disaster coordination. Such organizations are composed of government agencies, NGOs, academics and donors and during the 1998 flood, most DEC agencies related to one or more of the following organizations at a national level:

- Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief and its associated body, the Bureau of Disaster Management - established in 1991, with officers posted to District level, the DMB is the operational body, responsible for all disaster management within government agencies. Currently funded and provided with technical assistance by UNDP;

- The NGO Affairs Bureau - the government department responsible for approving all NGO plans. During the 1998 flood, this government bureau was reported to have assisted NGOs to avoid duplication of services and reach areas of the country which was not covered by others;

- ADAB - an association for many NGOs, which at the time of disaster, acts as a forum for information exchange and as an advocacy body to present of NGO views to government;

- The Disaster Forum - an organization (originally established by Oxfam) which facilitates the exchange of knowledge of flood-specific disaster, with membership from government, academics, NGOs and donor agencies;

- NIRAPAD - a constituted disaster management body (originally established by CARE) which provides an exchange of information and training, mainly for CARE’s core disaster partners;

- Disaster Preparedness Information Service - established under the PRIP Trust, this body provides disaster situation reports and arranges information seminars;

The government’s strong presence at district and thana levels and the efforts of government officers to coordinate the delivery of disaster services at district and union levels was highly appreciated by agencies and NGO partners. With a strong government presence and with a general public that was more aware of its rights to receive humanitarian assistance, agencies found it easier to curb the misuse of relief goods and services by local, influential and wealthy persons.

Agencies reported that in 1998, the public’s response to disaster was greatly improved over the response in 1988. This is attributed to a greater general awareness, improved communications and the extensive government and non-government development programmes to the rural areas over the past 10 years.

The BDRCS reports that both middle and upper class people made extensive volunteer contributions, with shop-keepers eager to contribute food and housewives preparing and donating cooked meals from their homes. Students throughout the country have been mobilised to prepare dried food rations and ORS packets, often working throughout the night. Several agencies have utilised student volunteers at flood shelters, feeding centres and on water distribution teams. Student volunteers were well utilised by District Disaster Committees to collect up-to-date information of flood conditions in distant unions and villages.

Oxfam and its partners report that that poor people in char villages have mobilised resources and taken decisions to move whole communities to flood shelters. The Dhaka Ahsania Mission delivered the bulk of their flood programme through the mobilisation of poor people who had been students at their literacy centers. In Dhaka city, poor rickshaw-pullers have contributed towards disaster relief from their meager, daily earnings.

5.4 Disabled and Aged Beneficiaries

Most agencies reported that during the 1998 flood disaster, the provision of relief and rehabilitation services for disabled beneficiaries was weak. Although the disabled and the elderly were recognised as requiring special attention during a flood disaster, very few particular initiatives were available to specifically target those beneficiaries.

Under the general cultural perceptions of Bangladeshi society, it is assumed that elderly persons are cared for by the extended family. An assessment recently done by HelpAge International and funded by ECHO (Field Report, Older People in Emergencies, July 1999) indicates that increasingly, this is no longer the case. With increased levels of poverty, a weakening of extended family norms and the chaos that occurred in the 1998 flood disaster, elderly people tended to be left behind in the rush.

Older men often stayed behind to protect property and assets when the family moved to a flood shelter. Although this was often by their own choice, they were nevertheless abandoned to rising floodwaters. In normal times, poor widowed women are often responsible to find their own food, either by begging or scavenging in the community. During the 1998 flood, wealthier neighbours and Union Council members were often the only ones who had the political influence required to include poor, elderly widows on the lists for food distribution.

Cases were reported where elderly people, confined to their houses for many days were compelled to drink flood water because they had neither the physical strength needed to reach tubewells, nor the economic means to hire a boat to obtain clean water. Emphasis placed on extra nutrition for small children, pregnant women and lactating mothers often meant that older people were neglected in such supplementary diet programmes. Cases were reported where elderly women refused to go to communal flood shelters because their religious beliefs could not be respected in un-segregated conditions.

The HAI assessment indicated that the vast majority of older people found the destruction of their livelihood, combined with their ongoing poverty to be the most difficult of all problems and the one from which so many others stemmed. There were almost no programmes specifically targeted to assist the elderly to recover from loss of their income-earning assets, such as cows, goats and poultry. With the enormous demand for income-earning opportunities from able-bodied persons, the elderly were almost always excluded from cash-for-work programmes. Even on a routine basis, the elderly are not eligible for membership in savings and credit groups. Certainly with scarce resources and high demand in the immediate post-flood period of 1998, their exclusion was wide-spread.

Agencies that had been able to target disabled and elderly beneficiaries had done so only by using a house-to-house survey and the development of a distressed persons list, on an intra-household basis. As part of their preparedness programme, the Resource Integration Centre suggested that community disaster committees would most suitably be responsible for identifying and listing such distressed persons.

5.5 Gender Issues

All agencies had attempted to consider gender issues in their response to the 1998 flood. Several agencies had well-developed policies on gender in disaster and had provided this material in their guidelines and training with partner NGOs.

To the extent that women could reach distribution centres, food rations and relief packages were provided directly to women, with the expectation that, as women are directly responsible for food preparation, there would be little chance of misuse. Some agencies provided women with extra supplies in the food ration, sanitary napkins and extra oil for pregnant women and lactating mothers. Within a flood-stricken household, poor women with only one sari are often obliged to remain in wet clothes for most of the day because there is no private space to dry off. The BDRCS provided women with a sari, included in their food ration.

The issue of women’s security was understood to be a problem for women who were sleeping outdoors along embankments and on city streets. At flood centres run by some DEC agencies, particular care was taken to assure the security of women. Nevertheless, in both urban and rural areas, there were reports of women being molested when they were obliged to sleep in open spaces. In some areas, women refused to go to flood shelters because of reports of sexual violence. Domestic violence increased with reports of husbands beating their wives and children when food-supplies had run out in flood-stricken households.

Following the peak period of the flood, several agencies provided effective services at centres for malnourished children, pregnant women, the aged and the disabled. On a daily basis, patients were provided with access to clean water and sanitation facilities, a cooked meal, curative treatment, education in basic health and nutrition and vegetable seeds. Although most of these centres were run with non-DEC funds, this example is provided to illustrate ‘good practices’.

In the rehabilitation phase, several DEC agencies targeted women with the majority of their assistance, with the expectation that women’s earning would go directly to the household’s consumption needs. Oxfam and its NGO partners targeted nearly all of its cash-for-work programmes towards women, even providing an earning opportunity for elderly women by engaging them for child care on the construction sites.

Several DEC agencies reported that they had included women on disaster committees, both at community and district levels. Women were then involved in decision-making, particularly concerning the type and packaging of foodstuffs and the type of work and wages that were suitable for women in cash-for-work programmes. The BDRCS have a fixed quota for women’s participation on their committees, known as Squads. Several agencies, including CARE and Oxfam have successfully managed flood shelters and nutrition centres by engaging women who were elected members of the Union Council.

DEC agencies have undoubtedly all had the best intentions to provide women with effective response services and indeed, there were many good initiatives to target vulnerable women with effective programming. However there were also several examples of wasted opportunities. DEC agencies that appeared to have weak gender thinking in their regular programming lacked the conceptual framework required for gender-specific design in the 1998 flood programming.

6.0 RECOMMENDATIONS

The evaluation team recommends that flood disaster mapping is a primary component of effective targeting and that such mapping of river basins and flood plains be part of basic disaster preparedness.

The evaluation team recommends that DEC agencies routinely include search and rescue operations in their disaster preparedness plans. NGO partners can facilitate this process with vulnerable communities. Action plans for vulnerable communities should include lists of government and non-government resources available at district and union levels and knowledge of vulnerable areas and households within the locality.

The evaluation team recommends that the most accurate form of beneficiary selection includes the following methods:

- the selection of most flood-effected persons based on a Needs Assessment, conducted on a house-to-house basis;

- within households, the use of Most Distressed Persons lists to target the elderly, the disabled and the most vulnerable of female-headed households;

- the mandatory setting of targets for the most flood affected households or distressed persons, usually 15 to 20 percent beyond the partner NGO’s regular clientele;

- careful monitoring, including the deployment of agency staff to work with the NGO partners in the field.

The evaluation team recommends that DEC agencies, through a working group, develop a Guideline for good practices of health in flood disaster. The Guideline would outline an inclusive programme, including water, sanitation, nutrition, health education and curative treatment (essential medicines, treatment standard, referral), as well as effective delivery systems.

The evaluation team recommends that DEC agencies concerned with future flood relief and rehabilitation activities utilise the experience of DEC agencies in rapid nutritional assessment. The 1998 experience is relevant for planners to: a) determine the optimum size and type of food ration for the general population; b) develop feeding programmes for targeted households and populations in vulnerable areas; c) assess long-term needs for cash-for-work, income generation and livelihood programmes.

The evaluation team recommends that DEC agencies, through a working group, study the issues surrounding housing with view to clarification for their future use. It is unlikely that a firm standardisation of disaster housing is a reasonable or preferred goal.

The evaluation team recommends that the DEC agencies at headquarters and in the field discuss the issues of grants, soft loans and micro-finance operations, with view to coming to some broad consensus on operational guidelines.

The evaluation team recommends that DEC agencies promote community-based flood-proofing as an effective long-term rehabilitation measure, utilising cash-for-work and other income-earning initiatives.

The evaluation team recommends that in light of their collective capability, the DEC agencies review their disaster preparedness and management capacity and that annual budget provision be made to strengthen that capacity, according to the agency’s priorities. In future, the 48 hour plans should provide evidence of up-graded disaster policy, guidelines and training of the agency and its core partners.

The evaluation team recommends the following modest improvements to the DEC reporting requirements:

- The 4 Week Plan of Action should contain more analysis and assessment of coverage in relation to the most seriously affected areas and target groups; currently these plans offer only modest statements of intent regarding how needs are being assessed and how activities relate to those most seriously affected;

- The financial reporting is inconsistent; most agencies follow the DfID format for the financial report but not all; some financial reports show variances against planned expenditures; some reports show expenses against specific procurements while others are aggregated; DEC should review and agree on a financial reporting format and ensure compliance for reasons of accountability and transparency;

- As demonstrated in Table 1, there is significant variation in the amounts agencies charge DEC for administrative expenses. In some cases these are direct expenses for travel, or salaries but they may also include an element of indirect overhead costs. DEC should establish a clearer policy on allowable administrative expenses. This would seem especially important in light of the use of public funds in the DEC appeals.

- The Final Narrative reports do provide the essential reporting of activities and expenditures. A section on lessons learned and issues addressed would be useful as would maps showing coverage in light of the most severely affected areas.

- DEC Secretariat should clarify communications regarding the second round of pooled funds so agencies can plan and bid on re-pooled funds in a timely manner and be clear about the available amounts and conditions for spending these funds.

The evaluation team recommends that DEC agencies develop policy to serve the disabled and elderly population during a disaster. Agencies will need to know what is the likely percentage of disabled and elderly in an average population. Disaster action plans should include specified quotas. Based on such policy, guidelines should be outlined to identify and list such distressed persons in community planning, as well as disaster plans, to provide them with service in both the relief and rehabilitation phases.

The evaluation team recommends that DEC agencies develop up-to-date policy perspectives on Gender in Disaster and that their staff and NGO partners are exposed to these concepts through written guidelines and training. Fixing quotas for women as participants will ensure that gender perspectives are promoted when programmes are widely implemented by a number of different players.

View the in pdf format* Download the in zipped MS Word format

* Get Adobe Acrobat Viewer (free)

Related Content