BROUGHT TO YOU BY

- Applications

- Computer Science

- Data Science Icons

- Machine Learning

- Mathematics

Dartmouth Summer Research Project: The Birth of Artificial Intelligence

Held in the summer of 1956, the dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence brought together some of the brightest minds in computing and cognitive science — and is considered to have founded artificial intelligence (ai) as a field..

In the early 1950s, the field of “thinking machines” was given an array of names, from cybernetics to automata theory to complex information processing. Prior to the conference, John McCarthy — a young Assistant Professor of Mathematics at Dartmouth College — had been disappointed by submissions to the Annals of Mathematics Studies journal. He regretted that contributors didn’t focus on the potential for computers to possess intelligence beyond simple behaviors. So, he decided to organize a group to clarify and develop ideas about thinking machines.

“At the time I believed if only we could get everyone who was interested in the subject together to devote time to it and avoid distractions, we could make real progress”. John McCarthy

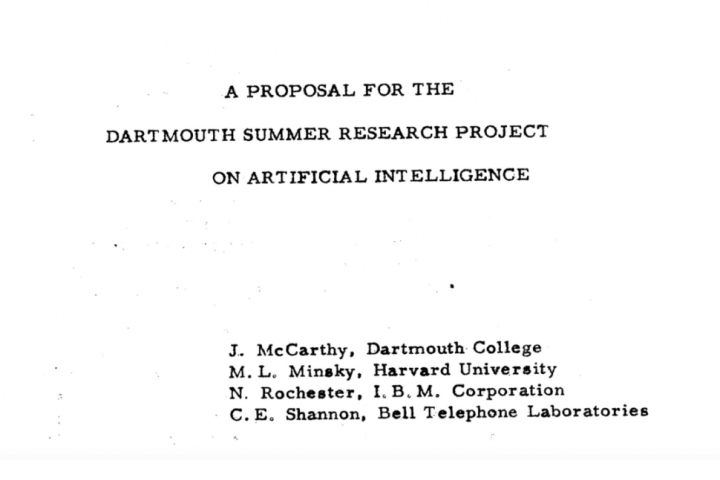

John approached the Rockefeller Foundation to request funding for a summer seminar at Dartmouth for 10 participants. In 1955, he formally proposed the project, along with friends and colleagues Marvin Minsky (Harvard University), Nathaniel Rochester (IBM Corporation), and Claude Shannon (Bell Telephone Laboratories).

Laying the Foundations of AI

The workshop was based on the conjecture that, “Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves.”

Although they came from very different backgrounds, all the attendees believed that the act of thinking is not unique either to humans or even biological beings. Participants came and went, and discussions were wide reaching. The term AI itself was first coined and directions such as symbolic methods were initiated. Many of the participants would later make key contributions to AI, ushering in a new era.

IBM First Computer

Nathaniel Rochester designs the IBM 701, the first computer marketed by IBM.

“Machine Learning” is coined

Attendee Arthur Samuel coins the term “machine learning” and creates the Samuel Checkers-Playing program, one of the world’s first successful self-learning programs.

Marvin Minsky Wins the Turing Award

Marvin Minsky wins the Turing Award for his “central role in creating, shaping, promoting and advancing the field of artificial intelligence.”

Discover more articles

K-nearest neighbors algorithm: classification and regression star, katherine johnson: trailblazing nasa mathematician, mary lucy cartwright: the inspired mathematician behind chaos theory, your inbox will love data science.

For IEEE Members

Ieee spectrum, follow ieee spectrum, support ieee spectrum, enjoy more free content and benefits by creating an account, saving articles to read later requires an ieee spectrum account, the institute content is only available for members, downloading full pdf issues is exclusive for ieee members, downloading this e-book is exclusive for ieee members, access to spectrum 's digital edition is exclusive for ieee members, following topics is a feature exclusive for ieee members, adding your response to an article requires an ieee spectrum account, create an account to access more content and features on ieee spectrum , including the ability to save articles to read later, download spectrum collections, and participate in conversations with readers and editors. for more exclusive content and features, consider joining ieee ., join the world’s largest professional organization devoted to engineering and applied sciences and get access to all of spectrum’s articles, archives, pdf downloads, and other benefits. learn more →, join the world’s largest professional organization devoted to engineering and applied sciences and get access to this e-book plus all of ieee spectrum’s articles, archives, pdf downloads, and other benefits. learn more →, access thousands of articles — completely free, create an account and get exclusive content and features: save articles, download collections, and talk to tech insiders — all free for full access and benefits, join ieee as a paying member., the meeting of the minds that launched ai, there’s more to this group photo from a 1956 ai workshop than you’d think.

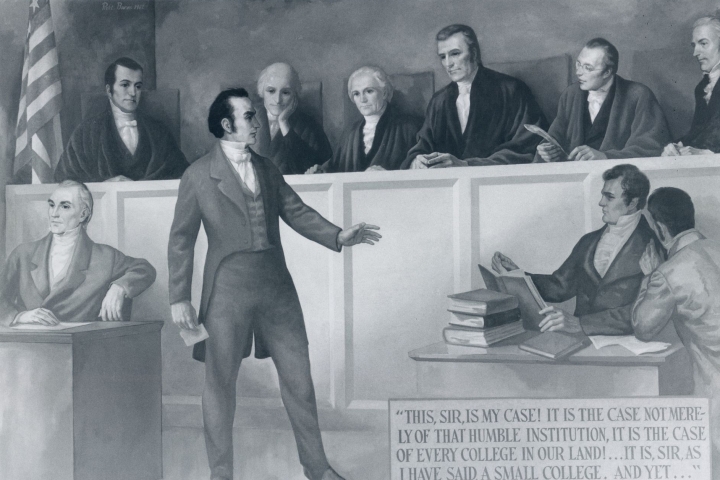

At the 1956 Dartmouth AI workshop, the organizers and a few other participants gathered in front of Dartmouth Hall.

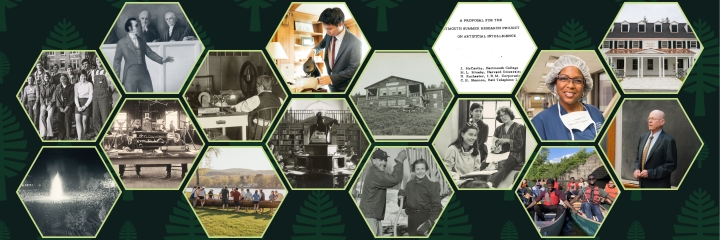

The Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence , held from 18 June through 17 August of 1956, is widely considered the event that kicked off AI as a research discipline. Organized by John McCarthy , Marvin Minsky , Claude Shannon , and Nathaniel Rochester , it brought together a few dozen of the leading thinkers in AI, computer science, and information theory to map out future paths for investigation.

A group photo [shown above] captured seven of the main participants. When the photo was reprinted in Eliza Strickland’s October 2021 article “The Turbulent Past and Uncertain Future of Artificial Intelligence” in IEEE Spectrum , the caption identified six people, plus one “unknown.” So who was this unknown person?

Who is in the photo?

Six of the people in the photo are easy to identify. In the back row, from left to right, we see Oliver Selfridge , Nathaniel Rochester, Marvin Minsky, and John McCarthy. Sitting in front on the left is Ray Solomonoff , and on the right, Claude Shannon. All six contributed to AI, computer science, or related fields in the decades following the Dartmouth workshop.

Between Solomonoff and Shannon is the unknown person. Over the years, some people suggested that this was Trenchard More , another AI expert who attended the workshop.

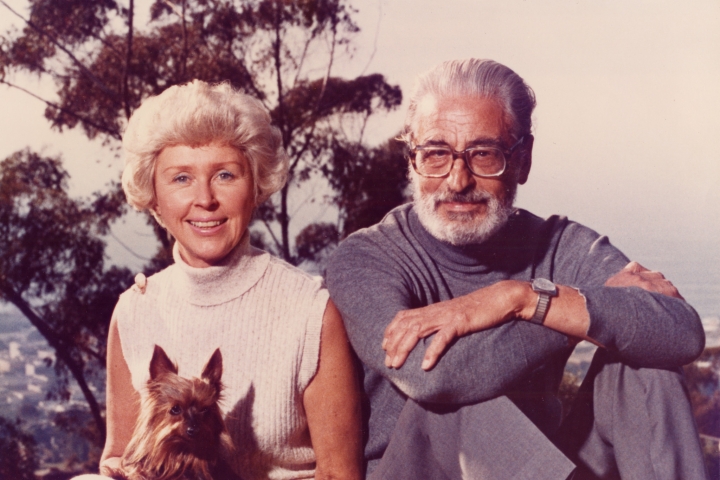

I first ran across the Dartmouth group photo in 2018, when I was gathering material for Ray’s memorial website . Ray and I had met in 1969, and we got married in 1989; he passed away in late 2009. Over the years, I had attended a number of his talks, and I had met many of Ray’s peers and colleagues in AI, so I was curious about the photo.

I thought, “Gee, that guy in the middle doesn’t look like my memory of Trenchard.” So I called up Trenchard’s son Paul More. He assured me that the unknown person was not his father.

More recently, I discovered a letter among Ray’s papers. On 8 November 1956, Nat Rochester sent a short note and a copy of the photo to some colleagues: “Enclosed is a print of the photograph I took of the Artificial Intelligence group.” He sent his note to McCarthy, Minsky, Selfridge, Shannon, Solomonoff—and Peter Milner.

So the unknown person must be Milner! This makes perfect sense. Milner was working on neuropsychology at McGill University , in Montreal, although he had trained as an electrical engineer. He’s not generally lumped in with the other AI pioneers because his research interests diverged from theirs. Even at Dartmouth, he felt he was in over his head, as he wrote in his 1999 autobiography: “I was invited to a meeting of computer scientists and information theorists at Dartmouth College…. Most of the time I had no idea what they were talking about.”

In his fascinating autobiography, Milner writes about his work in radar development during World War II, and his switch after the war from nuclear-reactor design to psychology. His doctoral thesis in 1954, “ Effects of Intracranial Stimulation on Rat Behaviour ,” examined the effects of electrical stimulation on certain rat neurons, which became widely and enthusiastically known as “pleasure centers.”

This work led to one of Milner’s most famous papers, “ The Cell Assembly: Mark II ,” in 1957. The paper describes how, when a neuron in the brain fires, it excites similar connected neurons (especially those already aroused by sensory input) and randomly excites other cortical neurons. Cells may form assemblies and connect with other assemblies. But the neurons don’t seem to exhibit the same snowballing behavior of atoms that leads to an exponential explosion. How neurons might inhibit this effect were among his ideas that led to new insights at the workshop.

Milner’s work contributed to the early development of artificial neural networks, and it’s why he was included in the Dartmouth meeting. There was considerable interest among AI researchers in studying the brain and neurons in order to reproduce its functions and intelligence.

But as Strickland notes in her October 2021 Spectrum article, a division was already forming in AI research. One side focused on replicating the brain, while the other was more interested in what the mind might do to directly solve problems. Scientists interested in this latter approach were also represented at Dartmouth and later championed the rise of symbolic logic, using heuristic and algorithmic processes, which I’ll discuss in a bit.

Where Was the Photo Taken?

Rochester’s photo from 1956 shows the left-hand side of Dartmouth Hall in the background. In 2006 Dartmouth convened a conference, AI@50 , to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the AI gathering and to discuss AI’s present and future. Trenchard More, the person most often misidentified as the “unknown person” in Nat’s photo, met with the organizers, James Moor and Carey Heckman, as well as Wendy Conquest, who was working on a movie about AI for the conference. None of the AI@50 organizers knew exactly where the 1956 meeting had taken place.

More led them across the lawn and to the left-hand side door of Dartmouth Hall. He showed them the rooms that were used, which in turn triggered an old memory. During the 1956 meeting, as More recalled in a 2011 interview , “Selfridge, and Minsky, and McCarthy, and Ray Solomonoff, and I gathered around a dictionary on a stand to look up the word heuristic , because we thought that might be a useful word.” On that 2006 tour of Dartmouth Hall, he was delighted to find that the dictionary was still there.

The word heuristic was invoked all through the summer of 1956. Instead of trying to analyze the brain to develop machine intelligence, some participants focused on the operational steps needed to solve a given problem, making particular use of heuristic methods to quickly identify the steps.

Early in the summer, for instance, Herb Simon and Allen Newell gave a talk on a program they had written, the logic theory machine . The program relied on early ideas of symbolic logic, with algorithmic steps and heuristic guidance in list form. They later won the 1975 Turing Award for these ideas. Think of heuristics as intuitive guides. The logic theory machine used such guides to initiate the algorithmic steps—that is, the set of instructions to actually carry out the problem solving.

Who Wasn’t in the Photo

There was one person who was at the Dartmouth Workshop from time to time but was never included in any of the lists of attendees: Gloria Minsky, Marvin’s wife.

But Gloria was definitely a presence that summer. Marvin, Ray, and John McCarthy were the only three participants to stay for the entire eight-week workshop. Everyone else came and went as their schedules allowed. At the time, Gloria was a pediatrics fellow at Children’s Hospital in Boston, but whenever she could, she would drive up to Dartmouth, stay in Marvin’s apartment, and visit with whoever was at the workshop.

Several years earlier, in the spring of 1952, Gloria had been doing her residency in pathology at New York’s Bellevue Hospital, when she began dating Marvin. Marvin was a Ph.D. student at Princeton, as was McCarthy, and the two were invited to Bell Labs for the summer to work under Claude Shannon. In July, just four months after their first meeting, Gloria and Marvin got married. Although Marvin was working nonstop for Shannon, Shannon insisted he and Gloria take a honeymoon in New Mexico.

Four years later, McCarthy, Shannon, and Minsky, along with Nat Rochester, organized the Dartmouth workshop . Gloria remembered a conversation between her husband and Ray, in which Marvin expressed a thought that later became one of his hallmarks: “You need to see something in more than one way to understand it.” In Minsky’s 2007 book The Emotion Machine , he looked at how emotions, intuitions, and feelings create different descriptions and provide different ways of looking at things. He tended to favor symbolic logic and deductive methods in AI, which he called “good old-fashioned AI.”

Ray, meanwhile, was focused on probabilities—the likelihood of something happening and predictions of how it might evolve. He later developed algorithmic probability, an early version of algorithmic information theory, in which each different description of something leads with a probabilistic likelihood (some more likely, some less likely) of a given outcome in the future. Probabilistic methods eventually became the underpinnings of machine learning.

These days, as chatbots enter the limelight, and compression methods are used more in AI, the value of understanding things in many ways and using probabilistic predictions will only grow in importance. That is, logic and probability methods are uniting. These in turn are being aided by new work on neural nets as well as symbolic logic. And so the photo that Nat Rochester took not only captured a moment in time for AI. It also offered a glimpse into how AI would develop.

The author thanks Gloria Minsky, Margaret Minsky, Nicholas Rochester, Julie Sussman, Gerald Jay Sussman, and Paul More for their help and patience.

- Marvin Minsky’s Legacy of Students and Ideas ›

- How Claude Shannon Helped Kick-start Machine Learning ›

- The Turbulent Past and Uncertain Future of Artificial Intelligence ›

- A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial ... ›

- Ray Solomonoff and the Dartmouth Summer Research Project in ... ›

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Coined at Dartmouth | Dartmouth ›

Ukraine Is the First “Hackers’ War”

Esa satellites to test razor-sharp formation flying, enhance your tech and business skills during ieee education week, related stories, faster, more secure photonic chip boosts ai training, what if the biggest ai fear is ai fear itself, could ai disrupt peer review.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Data Science

- Hardware & Sensors

- Machine Learning

- Agriculture

- Defense & Cyber Security

- Healthcare & Sports

- Hospitality & Retail

- Logistics & Industrial

- Office & Household

- Write for Us

Unlocking the power and security of autonomous databases

Empowering automation: the revolution of automated charging for agv batteries, how to build a winning robotics competition team, designing combat robots: essential tips for success, questions every ceo should ask about cybersecurity, top open source malware analysis tools, best email forensics techniques and tools, 6 essential audiobooks for cybersecurity professionals, why businesses should invest in decentralized apps, a close watch: how uk businesses benefit from advanced cctv systems, empowering small businesses: the role of it support in growth and…, product marketing: leveraging photorealistic product rendering services, everything tech: how technology has evolved and how to keep up….

- Technologies

The historic Dartmouth Conference of 1956 – Setting the stage for AI

The year was 1956. The world was still recovering from World War II, but a new kind of intellectual battleground was emerging. This war of ideas, focused on pushing the boundaries of machine capabilities, unfolded not with bullets and bombs, but with lines of code and the whirring of nascent computers. At its center was a pivotal academic event: the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, now known as the Dartmouth Conference.

Held over the summer from June 18 to August 17, 1956, at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, the workshop brought together a select group of researchers in AI, computer science , and information theory. The conference took place in an informal setting with attendees gathering in a relaxed environment conducive to brainstorming and collaboration. These visionaries, including John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky, used the extended brainstorming session to exchange ideas and envision the possibilities of creating intelligent machines. Their goal: to explore the feasibility of machines that could think, learn, and solve problems like humans.

Birth of a Term “Artificial Intelligence”

It was at this conference that the term that would change the course of history was first coined: “Artificial Intelligence”, or “AI”. This wasn’t just a catchy phrase; it was a declaration of intent. These scientists believed machines could be more than glorified calculators, but rather partners that could augment human intelligence and propel us beyond our limitations.

The optimism in the room was palpable. Early computer programs were already showing promise, solving complex math problems, proving theorems, and even taking initial steps towards understanding human language. For many, this was a glimpse into a future filled with intelligent machines that could revolutionize every aspect of life.

The Legacy of Dartmouth

The Dartmouth Conference didn’t achieve specific breakthroughs in building intelligent machines – the computational power of the time simply wasn’t sufficient. However, its significance lies in setting the stage for the future of AI. Here are some key outcomes:

- Coining the Term “Artificial Intelligence” : The term “artificial intelligence” was coined during the Dartmouth Conference. John McCarthy, one of the attendees and a key figure in AI’s early development, proposed it as a unifying concept for the diverse research areas discussed at the conference.

- Conceptual Foundations : The workshop explored core concepts that continue to be relevant in AI research today, like neural networks, machine learning, and even artificial creativity.

- Marvin Minsky’s Proposal : Marvin Minsky, another influential figure in AI, proposed a summer research project at the conference. This proposal laid the foundation for the development of the first artificial intelligence program, the Logic Theorist, by Allen Newell, J.C. Shaw, and Herbert A. Simon.

- Sparking Enthusiasm : The gathering fueled excitement about the potential of AI, inspiring a new generation of researchers to pursue this field. Government agencies, particularly the US Department of Defense’s DARPA, saw the potential of AI for military applications. The Cold War loomed large, and the idea of machines that could outthink and outmaneuver the enemy was a powerful motivator. This connection to the military had a long history, stretching back to the code-breaking efforts at Bletchley Park during World War II.

- Initial Ambiguity and Skepticism : Despite its significance in retrospect, the Dartmouth Conference did not attract widespread attention at the time. Many attendees were uncertain about the feasibility of creating intelligent machines, and there was skepticism about the goals outlined during the conference. The conference had a relatively small number of attendees. Some scientists, like Herbert Simon, cautioned against setting expectations too high. They argued that building a truly intelligent machine was a far more complex challenge than anyone realized.

- Long-Term Impact : Despite its significance in retrospect, the Dartmouth Conference did not receive much publicity outside academic circles at the time. Despite its modest beginnings, the Dartmouth Conference had a profound and lasting impact on the development of AI as a field of study. Many of the ideas and research directions proposed at the conference continue to shape AI research and development to this day.

Less Well-Known Contributions and Events that Precede the Dartmouth Conference

While the Dartmouth Conference marked a significant turning point in AI research, it wasn’t born in a vacuum. Here are some lesser-known contributions and events that laid the groundwork for the 1956 gathering:

In October 1953, the Proceedings of the IRE published a special issue titled “The Computer Issue,” in collaboration with the PGEC, showcasing the remarkable progress in computer design and technology during the 1950s. Within its pages, luminaries like Claude Shannon discussed the potential of computers in emulating human capabilities, foreshadowing the transformative impact of emerging technologies such as transistors.

During the same period, the United States and Europe witnessed the burgeoning development of electronic computers, propelled by both governmental and industrial support. IBM’s introduction of the Type 701 computer marked a significant milestone, setting the stage for the advent of second-generation computers. Nathaniel Rochester, a researcher at IBM, played a pivotal role in the logical organization of the Type 701, laying the groundwork for subsequent advancements.

The early 1950s witnessed pioneering experiments in machine learning and logic, spearheaded by figures like Arthur Samuel and Claude Shannon. Samuel’s implementation of the first learning checkers program on an IBM 704 computer in 1954 heralded a new era in machine learning research. Meanwhile, luminaries like Newell and Simon delved into computer chess strategies and logic theorem proving, paving the way for future developments in AI.

In March 1955, the PGEC sponsored a landmark Symposium on “The design of machines to simulate the behavior of the human brain,” offering invaluable insights into the quest for intelligent machines. Distinguished panel members, including McCulloch, Oettinger, and Rochester, deliberated on the challenges and methodologies of simulating human brain functions. This symposium laid the foundation for the canonical distinction between engineering-based and theoretically oriented approaches in machine intelligence.

As the 1950s progressed, the intersection of Operations Research (OR) and AI became increasingly apparent. The Symposium on “The impact of computers on science and society” in March 1956 showcased the burgeoning synergy between computational techniques and complex decision-making processes. Figures like John Mauchly and David Sayre discussed the nascent field of “artificial intelligence,” foreshadowing its transformative potential in diverse domains.

A Lasting Legacy

Despite the reservations, the spirit of the Dartmouth Conference was infectious. It marked a turning point in the history of AI, ushering in an era of rapid growth and exploration. The seeds sown in 1956 would blossom into a field that would transform the world, for better or worse. The journey would be filled with triumphs and failures, with periods of great hope followed by inevitable disillusionment. Yet, the spark ignited at Dartmouth continues to burn brightly, a testament to the enduring human fascination with creating intelligent machines in our own image.

This group photo depicts seven men, all participants in the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence in 1956. The photo was taken on the lawn with Dartmouth Hall visible in the background.

Here’s a description of the people in the photo:

Back row (from left to right): Oliver Selfridge, Nathaniel Rochester, Marvin Minsky, and John McCarthy Front row (left): Ray Solomonoff Front row (right): Claude Shannon

The identity of the person sitting between Solomonoff and Shannon was a mystery for a while. Initially, some people thought it was Trenchard More, another AI expert present at the workshop. However, an investigation revealed the person to be Peter Milner, a neuropsychologist from McGill University.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Top programming languages for building ai, history of programming languages – timeline, thinking machines – a history of ai in chess, leveraging global talent and ai in the cpg industry – interview with drew cesario, 25 national artificial intelligence research institutes in the us, at-risk emerging technologies: balancing innovation and security, will ai replace video editors, breaking language barriers: a conversation with samy zachary on alorica’s revolt ai-linguistic platform, unveiling the dark secrets behind google’s new ai model, ‘gemini’.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Visual Essays

- Print Subscription

A Look Back on the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence

At this convention that took place on campus in the summer of 1956, the term “artificial intelligence” was coined by scientists..

For six weeks in the summer of 1956, a group of scientists convened on Dartmouth’s campus for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. It was at this meeting that the term “artificial intelligence,” was coined. Decades later, artificial intelligence has made significant advancements. While the recent onset of programs like ChatGPT are changing the artificial intelligence landscape once again, The Dartmouth investigates the history of artificial intelligence on campus.

That initial conference in 1956 paved the way for the future of artificial intelligence in academia, according to Cade Metz, author of the book “Genius Makers: the Mavericks who Brought AI to Google, Facebook and the World.”

“It set the goals for this field,” Metz said. “The way we think about the technology is because of the way it was framed at that conference.”

However, the connection between Dartmouth and the birth of AI is not very well-known, according to some students. DALI Lab outreach chair and developer Jason Pak ’24 said that he had heard of the conference, but that he didn’t think it was widely discussed in the computer science department.

“In general, a lot of CS students don’t know a lot about the history of AI at Dartmouth,” Pak said. “When I’m taking CS classes, it is not something that I’m actively thinking about.”

Even though the connection between Dartmouth and the birth of artificial intelligence is not widely known on campus today, the conference’s influence on academic research in AI was far-reaching, Metz said. In fact, four of the conference participants built three of the largest and most influential AI labs at other universities across the country, shifting the nexus of AI research away from Dartmouth.

Conference participants John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky would establish AI labs at Stanford and MIT, respectively, while two other participants, Alan Newell and Hebert Simon, built an AI lab at Carnegie Mellon. Taken together, the labs at MIT, Stanford and Carnegie Mellon drove AI research for decades, Metz said.

Although the conference participants were optimistic, in the following decades, they would not achieve many of the achievements they believed would be possible with AI. Some participants in the conference, for example, believed that a computer would be able to beat any human in chess within just a decade.

“The goal was to build a machine that could do what the human brain could do,” Metz said. “Generally speaking, they didn’t think [the development of AI] would take that long.”

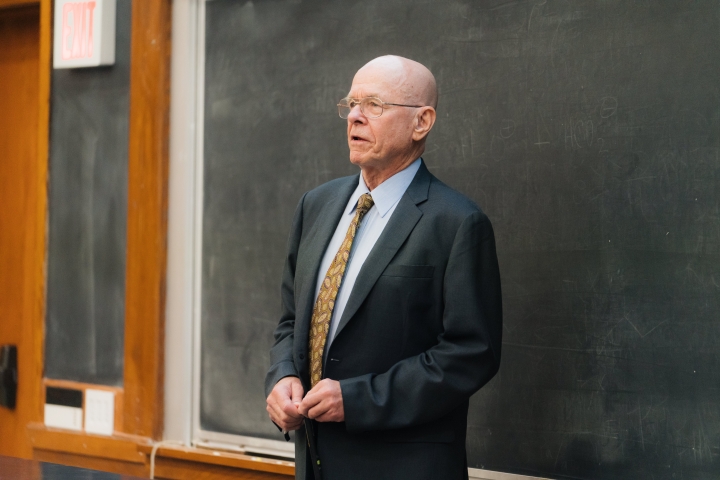

The conference mostly consisted of brainstorming ideas about how AI should work. However, “there was very little written record” of the conference, according to computer science professor emeritus Thomas Kurtz, in an interview that is part of the Rauner Special Collections archives.

The conference represented all kinds of disciplines coming together, Metz said. At that point, AI was a field at the intersection of computer science and psychology and it had overlaps with other emerging disciplines, such as neuroscience, he added.

Metz said that after the conference, two camps of AI research emerged. One camp believed in what is called neural networks, mathematical systems that learn skills by analyzing data. The idea of neural networks was based on the concept that machines can learn like the human brain, creating new connections and growing over time by responding to real-world input data.

Some of the conference participants would go on to argue that it wasn’t possible for machines to learn on their own. Instead, they believed in what is called “symbolic AI.”

“They felt like you had to build AI rule-by-rule,” Metz said. “You had to define intelligence yourself; you had to — rule-by-rule, line-by-line — define how intelligence would work.”

Notably, conference participant Marvin Minsky would go on to cast doubt on the neural network idea, particularly after the 1969 publication of “Perceptrons,” co-authored by Minsky and mathematician Seymour Paper, which Metz said led to a decline in neural network research.

Over the decades, Minsky adapted his ideas about neural networks, according to Joseph Rosen, a surgery professor at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center. Rosen first met Minsky in 1989 and remained a close friend of his until Minsky’s death in 2016.

Minsky’s views on neural networks were complex, Rosen said, but his interest in studying AI was driven by a desire to understand human intelligence and how it worked.

“Marvin was most interested in how computers and AI could help us better understand ourselves,” Rosen said.

In about 2010, however, the neural network idea “was proven to be the way forward,” Metz said. Neural networks allow artificial intelligence programs to learn tasks on their own, which has driven a current boom in AI research, he added.

Given the boom in research activity around neural networks, some Dartmouth students feel like there is an opportunity for growth in AI-related courses and research opportunities. According to Pak, currently, the computer science department mostly focuses on research areas other than AI. Of the 64 general computer science courses offered every year, only two are related to AI, according to the computer science department website.

“A lot of our interests are shaped by the classes we take,” Pak said. “There is definitely room for more growth in AI-related courses.”

There is a high demand for classes related to AI, according to Pak. Despite being a computer science and music double major, he said he could not get into a course called MUS 14.05: “Music and Artificial Intelligence” because of the demand.

DALI Lab developer and former development lead Samiha Datta ’23 said that she is doing her senior thesis on neural language processing, a subfield of AI and machine learning. Datta said that the conference is pretty well-referenced, but she believes that many students do not know much about the specifics.

She added she thinks the department is aware of and trying to improve the lack of courses taught directly related to AI, and that it is “more possible” to do AI research at Dartmouth now than it would have been a few years ago, due to the recent onboarding of four new professors who do AI research.

“I feel lucky to be doing research on AI at the same place where the term was coined,” Datta said.

Dartmouth’s Extreme Athletes: Students’ Feats of Endurance

Residential Roadblocks: Investigating the Impact of Hanover’s Zoning Laws

Struggling Abroad: Students’ Honest Experiences

Students react to roger federer being named 2024 commencement speaker, tennis icon roger federer to speak at 2024 commencement ceremony, dartmouth offers admission to 1,685 applicants for the class of 2028, sphinx building vandalized, college removes student flags in recent policy enforcement.

The Dartmouth

Cookie policy

The 1956 Dartmouth Workshop: The Birthplace of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Table of Contents

In the summer of 1956, a small gathering of researchers and scientists at Dartmouth College, a small yet prestigious Ivy League school in Hanover, New Hampshire, ignited a spark that would forever change the course of human history. This historic event, known as the Dartmouth Workshop, is widely regarded as the birthplace of artificial intelligence (AI) and marked the inception of a new field of study that has since started revolutionizing countless aspects of our lives.

Origins of the Dartmouth Workshop

The idea for the Dartmouth Workshop was conceived by John McCarthy , Marvin Minsky , Nathaniel Rochester , and Claude Shannon . These visionary individuals recognized the potential of computers to simulate human intelligence and sought to bring together like-minded individuals to explore this tantalizing possibility.

In the summer of 1956, they proposed a project titled “Artificial Intelligence” for a workshop that was to be held at Dartmouth. The original, historic proposal is available on Stanford’s website [PDF] . In their proposal, they defined artificial intelligence as “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines.” They also claimed that “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.” It was the first time the term “Artificial Intelligence” was used, marking a new era in technological advancement. The workshop was also influenced by the ideas and theories of John von Neumann and Alan Turing , who had proposed the concept of a universal computing machine and had laid the groundwork for the theoretical underpinnings of AI.

Objectives and Participants

The primary objective of the Dartmouth Workshop was to explore the concept of “thinking machines” and to investigate whether computers could be programmed to exhibit intelligent behavior. The participants, a small group of mathematicians, computer scientists, a psychiatrist, a neurophysiologist, a physicist and others. It included luminaries such as John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Allen Newell, Herbert Simon, Arthur Samuel, Oliver Selfridge, and Ray Solomonoff, among others. Their collective expertise spanned a wide range of disciplines, which set the stage for rich interdisciplinary discussions and collaborations.

Key Themes and Discussions

The workshop began in June and ran through August. During the two-month-long event, participants delved into several key themes that would shape the future of AI research. These discussions, brainstorming sessions, and presentations focused on topics such as problem-solving, language processing, learning, perception, and the relationship between human intelligence and machine intelligence. The aim was to construct machines that could mimic the human mind in learning, problem-solving, and the ability to improve themselves. Discussions also considered how far-reaching the implications of artificial intelligence might be, not only for the development of technology but for society as a whole. The participants were acutely aware of the ambitious nature of their goals and aimed to create a unified framework for understanding and developing artificial intelligence.

The event was hugely influential, inspiring many of its attendees to continue their research into artificial intelligence, thus seeding the growth of the AI community.

The Birth of AI as a Field of Study

The Dartmouth Workshop is widely regarded as the moment when AI emerged as a distinct field of study. It marked the first time that researchers from various disciplines came together explicitly to discuss the concept of machine intelligence. The term “artificial intelligence” itself was coined during the workshop, with John McCarthy suggesting it to describe the field’s objectives and aspirations.

Despite the event’s visionary goals and enthusiasm, it is important to note that the participants’ expectations sometimes exceeded the technological capabilities of the time. They anticipated that significant progress could be made within a couple of summers, but the complexity and challenges involved in achieving human-level AI were far greater than initially envisioned. Instead, it ignited a spark that fueled subsequent research and development in the field of AI, setting the stage for what we know as AI today.

Contributions and Legacy

The Dartmouth Workshop laid the groundwork for significant advancements in AI research and development. Many of the ideas and concepts discussed during the conference served as a foundation for subsequent breakthroughs in the field. Several attendees went on to make seminal contributions to AI, such as John McCarthy’s development of the programming language LISP and the concept of time-sharing systems, and Marvin Minsky’s work on perception and the development of early neural networks and establishment of MIT Media, which has been a pioneering institution in AI and related fields.

Furthermore, the workshop established a tradition of collaboration and knowledge sharing that continues to this day. It sparked the establishment of AI research institutions and AI labs at MIT, Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, and other universities; as well as the formation of a community that thrives on interdisciplinary cooperation and the exchange of ideas. The Dartmouth Workshop fostered an environment that encouraged researchers to explore the boundaries of what AI could achieve and helped establish it as a legitimate scientific pursuit.

This shift in focus also spurred the emergence of numerous tech companies that centered their business models on AI research and development.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

While the Dartmouth Workshop set the stage for remarkable progress in AI research, it also raised several challenges and ethical considerations. As the field advanced, questions surrounding the societal impact of AI, privacy, algorithmic bias, and the potential displacement of human labor became increasingly pertinent. The discussions held during the workshop provided a starting point for addressing these challenges. However, it is important to acknowledge that the field of AI has evolved significantly since 1956, and new ethical dilemmas have emerged.

The workshop participants recognized the importance of considering the implications of AI beyond the realm of academia. They discussed the potential societal impact of intelligent machines and envisioned AI systems that could assist in fields such as healthcare, education, and transportation. However, the realization of these aspirations required not only technical advancements but also careful consideration of the ethical implications associated with AI deployment.

As AI technology has progressed, concerns about privacy and data protection have become prominent. The Dartmouth Workshop did not explicitly delve into these issues, but it laid the foundation for discussions around the responsible use of AI and the need for ethical guidelines. Today, the ethical considerations surrounding AI include questions of transparency, accountability, fairness, and the potential for unintended consequences.

One notable aspect of the Dartmouth Workshop was the optimism among participants regarding the timeframe for achieving human-level AI. They believed that significant progress could be made within a couple of summers. However, as the complexities of AI research unfolded, it became evident that achieving artificial general intelligence (AGI) is an exceedingly challenging task. The conference’s vision and enthusiasm inspired subsequent generations of researchers, but it also underscored the importance of managing expectations and understanding the long-term nature of AI development.

Despite the challenges, the Dartmouth Workshop left a lasting legacy. It brought together brilliant minds and set in motion a wave of research and innovation that continues to reshape our world. The ideas and concepts discussed during the conference paved the way for the development of key AI technologies, such as expert systems, machine learning algorithms, natural language processing, and computer vision.

Moreover, the Dartmouth Workshop sparked the establishment of AI research institutions and academic programs, which have propelled the field forward. It created a community of researchers who, to this day, collaborate, share knowledge, and work towards advancing the frontiers of AI. The event’s influence on subsequent generations of AI pioneers cannot be overstated.

Reflections on the Dartmouth Workshop

Looking back on the Dartmouth Workshop from our vantage point in the 21st century, it is striking to see how far the field of artificial intelligence has progressed. One might marvel at the audacity and vision of the founding fathers of AI. In a time when computing was in its infancy, and even the most rudimentary tasks required vast amounts of computational resources, the idea of creating a machine that could simulate human intelligence must have seemed extraordinarily ambitious, if not entirely outlandish. Yet, these pioneers believed in the potential of their idea and pursued it with unwavering dedication. They could hardly have imagined the impact their discussions would have on the world.

Today, AI technologies have become deeply integrated into our daily lives. AI has become ubiquitous. It has transformed industries ranging from healthcare and finance to transportation and entertainment. The rapid development of AI has brought about significant advancements in machine learning, deep learning, robotics, and natural language processing, among other fields.

However, as AI continues to advance and its capabilities expand, it is essential to remain mindful of the ethical implications. The concerns that emerged from the early discussions at Dartmouth, such as privacy, bias, and the potential displacement of jobs, remain relevant today. The responsible development and deployment of AI systems require ongoing ethical reflection and proactive measures to mitigate potential risks.

The Dartmouth Workshop also reminds us of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration. The participants brought together their expertise from diverse fields, including mathematics, computer science, cognitive psychology, and philosophy. This interdisciplinary approach laid the foundation for the success of the conference and the subsequent development of AI as a multidisciplinary field. Further than AI, this lesson holds true today, as we face increasingly complex global challenges that necessitate a multidisciplinary approach.

As we look to the future, the challenges and opportunities in AI research and development are immense. Achieving human-level artificial general intelligence remains a complex and open-ended goal. Researchers continue to explore new avenues for advancing AI, such as explainable AI, trustworthy AI, and AI systems that can autonomously learn from limited data.

The Dartmouth Workshop showed us that the journey towards creating intelligent machines is a long and iterative one. It taught us that setbacks and unmet expectations are part of the process. The field of AI has matured significantly since 1956, but there is still much to learn and discover.

Lastly, the Dartmouth Workshop instills a sense of humility and awe for the complexity of human intelligence. Despite the impressive strides made in AI over the decades, truly replicating the human mind remains an elusive goal. This serves as a reminder of the incredible intricacy of human cognition and the challenges inherent in understanding and emulating it.

The Dartmouth Workshop of 1956 sparked the flames of curiosity and exploration that have propelled artificial intelligence to its current state. As we stand on the cusp of an AI-driven future, it is important to acknowledge the potential and the responsibility that comes with it. The future of AI holds immense promise, but it also raises ethical, social, and economic questions that require careful consideration.

While the conference’s participants may not have achieved their ambitious goals within the anticipated timeframe, their discussions and ideas paved the way for remarkable advancements in AI research and development. From advancements in machine learning and natural language processing to the integration of AI with robotics and autonomous systems, the potential for innovation and transformation is vast. AI will continue to reshape industries, improve healthcare outcomes, enhance productivity, and contribute to addressing global challenges such as climate change.

As AI continues to advance, the ethical considerations raised during the Dartmouth Conference remain relevant. The responsible development and deployment of AI systems require ongoing discussions around transparency, accountability, fairness, and the potential societal impact. Safeguards must be put in place to protect privacy, mitigate bias, and ensure transparency and accountability in AI systems. Continued research into AI ethics, policy frameworks, and regulations will be crucial to guide the responsible development and deployment of AI technologies.

Furthermore, as AI systems become more powerful and autonomous, the question of human-AI interaction and the impact on the workforce arises. It is important to foster a societal transition that ensures the equitable distribution of benefits and provides opportunities for reskilling and upskilling (Which is why we wrote The Future of Leadership in the Age of AI).

In the years to come, as AI continues to unfold its vast potential, let us remember the lessons from the Dartmouth Conference and approach the future with open minds, critical thinking, and a commitment to the well-being of all.

Author’s Note: The following section offers a speculative glimpse into the future of AI based on current trends and potential developments.

The Future of AI: A Glimpse Ahead

As we look ahead to the future of artificial intelligence, it is both exciting and challenging to envision the possibilities that lie before us. AI has already transformed numerous industries and aspects of our lives, but its potential is far from exhausted. Here, we present a speculative glimpse into the future of AI, based on current trends and potential developments.

- Advancements in Machine Learning: Machine learning, the core technology behind many AI applications, will continue to evolve. We can expect further improvements in deep learning algorithms, enabling machines to process and interpret increasingly complex and diverse datasets. Reinforcement learning, a technique that allows AI systems to learn through trial and error, will enable machines to acquire new skills and adapt to dynamic environments with greater agility.

- Human-Machine Collaboration: The future of AI will likely revolve around human-machine collaboration, where intelligent machines work alongside humans as partners, augmenting our abilities and enhancing our productivity. We can anticipate the rise of “explainable AI,” where AI systems are capable of providing transparent and interpretable explanations for their decisions, enabling humans to better understand and trust their outputs.

- Contextual Understanding and Natural Language Processing: Natural language processing (NLP) will continue to advance, allowing machines to comprehend and generate human language with greater fluency and context sensitivity. Conversational AI, already evident in virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa, will become more sophisticated and capable of engaging in complex and nuanced conversations. Language models, such as the one you are interacting with now, will continue to improve, providing increasingly accurate and context-aware responses.

- Ethical and Responsible AI: As AI becomes more pervasive in society, there will be an increased focus on ensuring its ethical and responsible use. Regulations and guidelines will be established to govern AI development and deployment, addressing concerns such as bias, privacy, and accountability. Efforts to address algorithmic fairness and transparency will be at the forefront, promoting AI systems that are unbiased, explainable, and respectful of privacy rights.

- AI in Healthcare and Medicine: AI will play an increasingly vital role in healthcare and medicine. From diagnosing diseases and predicting patient outcomes to assisting in drug discovery and personalized treatments, AI-powered systems will revolutionize healthcare delivery. Intelligent robots may also be deployed in surgical procedures, performing complex tasks with precision and reducing the risk of human error.

- Autonomous Systems and Robotics: The integration of AI with robotics will lead to the rise of autonomous systems in various domains. Self-driving cars will become more commonplace, revolutionizing transportation and reducing accidents. Robots will find applications in industries like manufacturing, agriculture, and logistics, performing tasks that are repetitive, dangerous, or require high precision. Collaborative robots, or cobots, will work alongside humans in shared workspaces, enhancing productivity and safety.

- AI and Sustainability: AI will also contribute significantly to sustainability efforts. From optimizing energy consumption in buildings and improving renewable energy systems to managing and minimizing waste, AI will play a vital role in addressing environmental challenges. Intelligent systems will help in monitoring and conserving natural resources, enabling more efficient and sustainable practices across industries.

- AI in Defence: AI will be increasingly incorporated into defence systems around the world, transforming the way military operations are conducted. This will include everything from autonomous vehicles and drones that can perform reconnaissance missions without risking human lives, to advanced algorithms capable of processing vast amounts of data to predict potential threats. Cybersecurity will also greatly benefited from AI, with machine learning algorithms able to detect, analyze, and respond to cyber threats more quickly and accurately than human operators. However, the use of AI in defence will carry massive challenges and risks (and this is the reason for me starting Defence.AI ). One of the primary concerns will be the ethical implication of delegating life-or-death decisions to machines, such as in the case of autonomous weapons. If these systems fail or are hacked, the consequences could be disastrous. There are also worries about an AI arms race, where nations compete to develop increasingly sophisticated AI-powered weapons, potentially leading to destabilization and conflict. Furthermore, there’s the risk of bias in AI systems. If the data used to train these systems is biased, the resulting decisions could be skewed and potentially harmful. And many others.

Marin Ivezic

Related Articles

The Quantum Computing Threat and 5G Security

Innovation Zones in Canada for Launching AI and 5G in Tandem

“Magical” Emergent Behaviours in AI: A Security Perspective

AI Oasis: AI’s Role in Saudi Vision 2030

A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence

The proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was, so far as I know, the first use of phrase Artificial Intelligence. If you are interested in the exact typography, you will have to consult a paper copy.

Download the article in PDF .

Books and Reviews

Notes on AI

What is AI?

Dartmouth Milestones

Read stories about dartmouth’s unique character, indelible spirit, and rich history. .

The award celebrates the field of “click chemistry,” a name Sharpless coined.

Read the story

Beilock is the first woman elected to the position in Dartmouth’s more than 250-year history.

Renamed the Frank J. Guarini School of Graduate and Advanced Studies in 2018 in acknowledgment of an investment by the Honorable Frank J. Guarini ’46, Guarini supports more than 1,000 graduate students, doctoral candidates, and postdoctoral scholars.

The residence hall welcomes the LGBTQIA community and allied students who share a passion for social justice issues.

Dartmouth renamed its medical school, founded in 1797, in honor of Audrey and Theodor Geisel, Class of 1925.

(Photo by Jay Davis ’90)

The First Year Student Enrichment Program empowers first-generation students to thrive academically.

Alumna Andrea Hayes-Jordan ’87, MED ’91 became the nation’s first Black female pediatric surgeon.

(Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

Sharpless credited a Dartmouth professor for helping set the course of his life’s work. He won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Each year the farm grows more than 2000 pounds of diverse, fresh, tasty, organic produce.

In September 1972, one hundred seventy-seven women matriculated as freshmen, along with 74 female transfer students.

(Photo by Robert Gill)

Today the program involves over 90 percent of the freshman class.

He won the Thayer Prize in Mathematics and the Kramer Fellowship at Dartmouth. He went on to win the Nobel Prize in Physics.

The Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was a seminal event for artificial intelligence as a field.

On Dec. 15, 1956, Polly Case straddled a small disk attached to a cable—a “poma lift”—and rode to the top of Holt’s Ledge in Lyme, N.H.

The lodge was constructed to serve some of the nation’s earliest competitive skiing.

Sanborn Library offers a tea service each weekday afternoon at 4 o’clock.

The library was designed by college architect Jens Frederick Larson, modeled after Independence Hall in Philadelphia.

Ready the story

A group of Dartmouth students gathered together with the goal of restoring a rowing team to the College.

Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood, a talented linguist, created the Russian program at the College.

The Amos Tuck School of Business Administration and Finance was the first institution in the world to offer a master’s degree in business administration. Edward Tuck, class of 1862, donated an initial grant of $300,000 to found the school in 1899, naming it in memory of his father Amos Tuck, class of 1835.

The medical x-ray, like many inventions, is the result of different people working simultaneously on the same idea.

During Dartmouth Night and Homecoming, alumni return to join students in a revelatory celebration that includes a colorful parade and blazing bonfire.

Sylvanus Thayer, Class of 1807, established the engineering school at his alma mater.

American-born and raised in Liberia, Samuel Ford McGill—Class of 1839—was the first black graduate of a U.S. medical school.

A landmark ruling in the development of U.S. constitutional and corporate law, Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward held that the College would remain a private institution and not become a state university.

Dartmouth’s “Medical Department” was established when founder Nathan Smith delivered his first lecture on Nov. 22.

See more medical school history

The Society of Social Friends “Socials” maintained a student-funded and managed library, circulating holdings to its members only.

Teaching & Learning

Harold j. berman, 1918-2007, a scholar of great social account.

Professor Emeritus Harold J. Berman, an expert on comparative, international and Russian law as well as legal history and philosophy and the intersection of law and religion, died Nov. 13. He was 89.

Known for his energetic and outgoing personality, Berman recently celebrated his 60th anniversary as a law professor. He joined the Harvard Law School faculty in 1949 and held the Story Professorship of Law and later the Ames Professorship of Law. A prolific scholar, Berman wrote 25 books and more than 400 scholarly articles, including his magnum opus, “Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition.”

“Harold was a scholar of boundless and lofty ambition,” said HLS Professor Emeritus Henry Steiner ’55. “His projects reached deeply not only into comparative analysis and history, but also religion and jurisprudence. This is a record that any distinguished scholar would take pride in.”

Born in 1918 in Hartford, Conn., Berman received a bachelor’s from Dartmouth College in 1938 and a master’s in history from Yale University in 1942. After a year at Yale Law School, he was drafted by the Army and served as a cryptographer in Europe, earning a Bronze Star. He returned to New Haven and finished his degree in 1947.

Berman’s interest in the Soviet legal system began during his law school years, when he studied Russian and taught himself Soviet law. He argued his first case in Moscow in 1958, representing the estate of Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes. Seeking to obtain royalties from the Soviet state on the millions of Conan Doyle books sold in the Soviet Union, Berman won the case in a Moscow city court. He later lost on appeal to a higher Russian Federation court.

Berman was a frequent visitor to Russia as a guest scholar and lecturer. As a result of his firsthand knowledge of the Soviet Union—rare for an American in the Cold War era—he became a leading consultant to Russian officials in the mid-1980s during glasnost and perestroika.

HLS Professor Emeritus Detlev Vagts ’51 was part of a group of academics Berman brought together to teach what they referred to as “capitalist law” in the Soviet Union during that time. Vagts recalled the challenges of their task:

“The young Muscovites had been trained to think of the act of two persons getting together to buy goods low and sell them high as a conspiracy to profiteer—which would get you five years of re-education in Siberia. Now they had to adjust to the idea that it was a legitimate partnership,” he said. “The first Russian law on corporations was drafted by lawyers who could not bear to use the term ‘capital’ for the account in the lower right corner of the balance sheet; they called it ‘the social account’ instead.”

In 1985, faced with the prospect of mandatory retirement, Berman left HLS for Emory Law School. At Emory, he held the Robert W. Woodruff Professorship of Law—the highest honor Emory bestows on a faculty member—for more than 20 years. He was the principal founder of the American Law Center in Moscow, a joint venture of Emory and the Law Academy of the Russian Ministry of Justice. He was also co-chairman of Emory’s World Law Institute, an organization that sponsors educational programs around the world.

Reflecting another of his long-term interests, Berman helped to develop Emory’s Center for the Study of Law and Religion. In 2003, he published “Law and Revolution, II: The Impact of the Protestant Reformations on the Western Legal Tradition.”

Modal Gallery

Gallery block modal gallery.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was a 1956 summer workshop widely considered [1] [2] [3] to be the founding event of artificial intelligence as a field. The project lasted approximately six to eight weeks and was essentially an extended brainstorming session. Eleven mathematicians and scientists originally ...

The Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was a seminal event for artificial intelligence as a field. In 1956, a small group of scientists gathered for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, which was the birth of this field of research. To celebrate the anniversary, more than 100 researchers ...

4 min read. 09_30_2021. Held in the summer of 1956, the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence brought together some of the brightest minds in computing and cognitive science — and is considered to have founded artificial intelligence (AI) as a field. In the early 1950s, the field of "thinking machines" was given an ...

The Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, held from 18 June through 17 August of 1956, is widely considered the event that kicked off AI as a research discipline. Organized ...

At its center was a pivotal academic event: the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, now known as the Dartmouth Conference. Held over the summer from June 18 to August 17, 1956, at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, the workshop brought together a select group of researchers in AI, computer science, and ...

From hosting the seminal Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence in 1956 to leading multidisciplinary research on large language models today, Dartmouth has always been at the forefront of AI. See what's happening around campus and learn about Dartmouth experts in the field.

Published May 19, 2023. For six weeks in the summer of 1956, a group of scientists convened on Dartmouth's campus for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. It was at this meeting that the term "artificial intelligence," was coined. Decades later, artificial intelligence has made significant advancements.

In the summer of 1956, a small gathering of researchers and scientists at Dartmouth College, a small yet prestigious Ivy League school in Hanover, New Hampshire, ignited a spark that would forever change the course of human history. This historic event, known as the Dartmouth Workshop, is widely regarded as the birthplace of artificial intelligence (AI) and marked the inception of a new field ...

It's considered by many to be the first artificial intelligence program and was presented at the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (DSRPAI) hosted by John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky in 1956. In this historic conference, McCarthy, imagining a great collaborative effort, brought together top researchers from various ...

The 1956 Dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence was initiated by this August 31, 1955 proposal, authored by John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon. The original typescript consisted of 17 pages plus a title page. Copies of the typescript are housed in the archives at Dartmouth College and Stanford University.

August 31, 1955. We propose that a 2 month, 10 man study of artificial intelligence be carried out during the summer of 1956 at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. The study is to proceed on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a ...

Text of the original 1955 Dartmouth Proposal. The proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was, so far as I know, the first use of phrase Artificial Intelligence. If you are interested in the exact typography, you will have to consult a paper copy. Download the article in PDF. Professor John McCarthy's page.

The 1956 Dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence was initiated by this August 31, 1955 proposal, authored by John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon.

The 1956 Dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence was initiated by this August 31, 1955 proposal, authored by John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon, along with the short autobiographical statements of the proposers. The 1956 Dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence was initiated by this August 31, 1955 proposal, authored ...

The 1956 Dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence was initiated by this August 31, 1955 proposal, authored by John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon. The original typescript consisted of 17 pages plus a title page. Copies of the typescript are housed in the archives at Dartmouth College and ...

The Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was a seminal event for artificial intelligence as a field. ... (Photo by D. Cutter '73, courtesy of the Dartmouth Library) 1956. Dartmouth Skiway opens. On Dec. 15, 1956, Polly Case straddled a small disk attached to a cable—a "poma lift"—and rode to the top of Holt's ...

C. E. Shannon, Bell Telephone Laboratories. August 3 1, 1955. A Proposal for the. DARTMOUTH SUMMER RESEARCH PROJECT ON ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE. We propose that a 2 month. 10 man study of artificial intelligence be. carried out during the summe r of 1956 at Dartmouth College in Hanover. New. Hampshire.

The 1956 Dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence was initiated by this August 31, 1955 proposal, authored by John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon. The original typescript consisted of 17 pages plus a title page. Copies of the typescript are housed in the archives at Dartmouth College and ...

This is a record that any distinguished scholar would take pride in.". Born in 1918 in Hartford, Conn., Berman received a bachelor's from Dartmouth College in 1938 and a master's in history from Yale University in 1942. After a year at Yale Law School, he was drafted by the Army and served as a cryptographer in Europe, earning a Bronze Star.

The mean intensity of the urban 'heat island' in Moscow (i.e. averaged in time difference between the air temperature in the city centre and outside the city) was nearly of 1.0-1.2 °C at the end of the 19th century, 1.2-1.4 °C one century ago and 1.6-1.8 °C both in the middle, and at the end of the 20th century.

Moscow City Teachers' Training University is founded by the resolution of the Moscow Government, Victor Ryabov appointed as its First Rector. Lyubov Kezina, Head of the Department of Education, and Vladimir Shadrikov, Deputy Minister of Education, are appointed as its co-founders. In 1995 MCU welcomes 1,300 students to be enrolled in 17 ...

The 1956 Dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence was initiated by this August 31, 1955 proposal, authored by John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon. The original typescript consisted of 17 pages plus a title page. Copies of the typescript are housed in the archives at Dartmouth College and

1. Introduction. The urban heat island phenomenon in the ground air layer has been well-known since 1820. It may be observed in any city and even in any small village almost all over the world (Kratzer, 1956, Böer, 1964, Landsberg, 1981, Oke, 1978, etc.).Investigation of this phenomenon is important because of the growth of cities everywhere.