22 Cases and Articles to Help Bring Diversity Issues into Class Discussions

Explore more.

- Course Materials

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

T he recent civic unrest in the United States following the death of George Floyd has elevated the urgency to recognize and study issues of diversity and the needs of underrepresented groups in all aspects of public life.

Business schools—and educational institutions across the spectrum—are no exception. It’s vital that educators facilitate safe and productive dialogue with students about issues of inclusion and diversity. To help, we’ve gathered a collection of case studies (all with teaching notes) and articles that can encourage and support these critical discussions.

These materials are listed across three broad topic areas: leadership and inclusion, cases featuring protagonists from historically underrepresented groups, and women and leadership around the world. This list is hardly exhaustive, but we hope it provides ways to think creatively and constructively about how educators can integrate these important topics in their classes. HBP will continue to curate and share content that addresses these equity issues and that features diverse protagonists.

Editors’ note: To access the full text of these articles, cases, and accompanying teaching notes, you must be registered with HBP Education. We invite you to sign up for a free educator account here . Verification may take a day; in the meantime, you can read all of our Inspiring Minds content .

Leadership and Inclusion

John Rogers, Jr.—Ariel Investments Co.

—by Steven S. Rogers and Greg White

Gender and Free Speech at Google (A)

—by Nien-hê Hsieh, Martha J. Crawford, and Sarah Mehta

The Massport Model: Integrating Diversity and Inclusion into Public-Private Partnerships

—by Laura Winig and Robert Livingston

“Numbers Take Us Only So Far”

—by Maxine Williams

For Women and Minorities to Get Ahead, Managers Must Assign Work Fairly

—by Joan C. Williams and Marina Multhaup

How Organizations Are Failing Black Workers—and How to Do Better

—by Adia Harvey Wingfield

To Retain Employees, Focus on Inclusion—Not Just Diversity

—by Karen Brown

From HBR 's The Big Idea:

Toward a Racially Just Workplace: Diversity efforts are failing black employees. Here’s a better approach.

—by Laura Morgan Roberts and Anthony J. Mayo

Cases with Protagonists from Historically Underrepresented Groups

Arlan Hamilton and Backstage Capital

—by Laura Huang and Sarah Mehta

United Housing—Otis Gates

—by Steven Rogers and Mercer Cook

Eve Hall: The African American Investment Fund in Milwaukee

—by Steven Rogers and Alterrell Mills

Dylan Pierce at Peninsula Industries

—by Karthik Ramanna

Maggie Lena Walker and the Independent Order of St. Luke

—by Anthony J. Mayo and Shandi O. Smith

Multimedia Cases:

Enterprise Risk Management at Hydro One, Multimedia Case

—by Anette Mikes

Women and Leadership Around the World

Monique Leroux: Leading Change at Desjardins

—by Rosabeth Moss Kanter and Ai-Ling Jamila Malone

Kaweyan: Female Entrepreneurship and the Past and Future of Afghanistan

—by Geoffrey G. Jones and Gayle Tzemach Lemmon

Womenomics in Japan

—by Boris Groysberg, Mayuka Yamazaki, Nobuo Sato, and David Lane

Women MBAs at Harvard Business School: 1962-2012

—by Boris Groysberg, Kerry Herman, and Annelena Lobb

Beating the Odds

—by Laura Morgan Roberts, Anthony J. Mayo, Robin J. Ely, and David A. Thomas

Rethink What You “Know” About High-Achieving Women

—by Robin J. Ely, Pamela Stone, and Colleen Ammerman

“I Try to Spark New Ideas”

—by Christine Lagarde and Adi Ignatius

How Women Manage the Gendered Norms of Leadership

—by Wei Zheng, Ronit Kark, and Alyson Meister

Is this list helpful to you? What other topics or materials would you like to see featured in our next curated list? Let us know .

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Thesis vs. Topic

As you begin to formulate a thesis for your essay, think about the following distinction between topic and thesis. A topic is a general area of inquiry; derived from the Greek topos (place), "topic" designates the general subject of your essay. For instance, "Munro Leaf's The Story of Ferdinand (1936) and Dr. Seuss's And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937) both respond to the rise of fascism" would be a weak thesis but a good a topic for an essay. From a topic, many specific theses can be extracted and developed. A thesis is more specific and delimited; it exists "within" your topic. In your essay, you need to use an argumentative thesis.

In argumentative writing, the writer takes a stance and offers reasons in support of it. Crucial to any piece of argumentative writing is its thesis. The thesis arises from the topic, or subject, on which the writing focuses, and may be defined as follows:

A thesis is an idea, stated as an assertion, which represents a reasoned response to a question at issue and which will serve as the central idea of a unified composition.

If we've selected as a topic the notion that these books show the power of unions we need to ask, "So what?" Do both stories make exactly the same argument in exactly the same way? How do they differ? How are they similar? In each tale, what are the workers' demands? With what degree of sympathy are those demands presented? In sum, what does focusing on this theme tells about what the books might mean? One possible thesis is:

If Munro Leaf's The Story of Ferdinand (1936) and Dr. Seuss's And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937) both respond to the rise of fascism, neither clearly articulates a political position on the subject: Although Leaf's book offers more allusions to European fascism than Seuss's does, both can be read as critical of fascism, indifferent to it, or proposing another political strategy entirely.

When you compose a thesis statement, think about how it satisfies the following tests:

1. Is it an idea? Does it state, in a complete sentence, an assertion? 2. Does it make a claim that is truly contestable and therefore engaging? (Yes, because one could also argue for a greater difference between these two tales, or that one or both more clearly advances a particular political ideology.) 3. Are the terms you are using precise and clear? (Key terms here seem to be: "fascism," "articulates," "political position," and "critical.") 4. Has the thesis developed out of a process of reasoning?

Once these questions have been satisfactorily answered, use the resulting thesis to organize your evidence and begin the actual writing. As you do so, bear in mind the following questions:

1. What is my purpose in writing? What do I want to prove? (Notice the explicit purpose in the thesis statement: it does not merely point out that both books show the power of organizing. Instead, the thesis takes a position on this topic, and then answers the question "So what?") 2. What question(s) does my writing answer? 3. Why do I think this question is important? Will other people think it equally important? 4. What are my specific reasons, my pieces of evidence? Does each piece of evidence support the claim I make in my thesis? 5. Where does my reasoning weaken or even stop? Am I merely offering opinions without reasoned evidence? 6. How can I best persuade my reader?

A hematoma is more than just a big bruise. Here's when they can be concerning.

Your body's circulatory system is a wondrous thing. It's made up of blood vessels that carry blood to and from your heart and also pumps blood to your lungs so you can breathe. It helps grow and repair cells and delivers nutrients, oxygen and hormones throughout your body. Critical organs like your brain , kidneys, liver and heart, plus all muscle tissue, are dependent on your circulatory system to function normally and survive.

But occasionally, issues within this system arise and certain diseases can affect how well things operate. Diabetes , for instance, can impact your circulatory system by causing fatty deposits to form inside blood vessels, limiting blood flow.

Another manifestation of a usually-mild problem that starts in the circulatory system is bruising. Matters can become more serious, however, when dealing with hematomas.

What is a hematoma?

A hematoma is a collection of blood related to a breakage of blood vessels . "This can occur due to injury or other trauma," says Dr. John Whyte, the Chief Medical Officer of WebMD and the author of "Take Control of Your Heart Disease Risk." He explains that as the blood pools in the surrounding tissues after blood vessels break, it can lead to "swelling and discoloration" – hallmark signs of a hematoma.

Hematomas are also sometimes caused by trauma associated with undergoing an operation .

While there are several instances where hematomas require medical intervention, "they generally can take one to four weeks to resolve on their own, though sometimes longer depending on their location and size," says Dr. Steven Maher, an emergency medicine physician at Mayo Clinic in Arizona.

To read next: Need to know how to lower your blood pressure? A cardiologist explains.

How is a hematoma different from a bruise?

Bruises and hematomas are similar in that both can occur as a result of a blow, bump, fall or other injury . But there are some distinctions as well:

- The first difference is related to size . "While both bruises and hematomas result from bleeding under the skin, a hematoma is usually more pronounced due to a larger accumulation of blood," says Dustin Portela, DO, a board-certified dermatologist and founder of Treasure Valley Dermatology in Boise, Idaho. Hematomas are also often larger because they frequently involve large blood vessels.

- Location is another factor. While bruises are usually visible just under the surface of the skin , hematomas can occur most anywhere in the body, "including under the skin, in muscles, in organs and spaces within the body," says Whyte.

- Another key difference is their swelling and firmness . "Hematomas often cause more noticeable swelling and can feel firm or lumpy due to the larger amount of clotted blood they contain," explains Whyte. Because of this swelling, "hematomas are often more painful than a bruise," says Portela.

- Duration is another distinctive factor. "Hematomas can last longer than bruises because the accumulated blood takes more time to be absorbed back into the body," says Whyte.

Good to know: Yes, exercise lowers blood pressure. This workout helps the most.

How serious is a hematoma?

Another key difference between bruising and hematomas is that hematomas can sometimes lead to serious medical complications. In cases where a hematoma is located near the brain, for instance, blood can collect between the covering of the brain (called the dura mater) and the surface of the brain. This occurrence is called a subdural hematoma and can become life-threatening if left untreated.

Abdominal hematomas are also serious and often manifest as blood in the urine or stool. A blood clot from a hematoma can also re-enter the bloodstream and block an artery – thereby cutting off circulation in part of the body.

While such occurrences are relatively rare and most hematomas aren't something to become overly concerned about, there are concerning elements one can look out for. "If a hematoma is large or continues to grow, it may indicate ongoing bleeding or a more serious injury that needs medical evaluation," says Whyte. It's also worth having a hematoma checked out if one occurs in one's head, around one's eyes, around one's stomach "or near any vital organs where they can press against tissues and impair function," says Portela.

There are accompanying symptoms that can also be helpful to look out for. "If a hematoma is accompanied by symptoms such as severe pain, numbness , weakness or if it affects the function of a limb or organ, it needs to be evaluated by a healthcare provider," says Whyte.

Get Started

Take the first step and invest in your future.

Online Programs

Offering flexibility & convenience in 51 online degrees & programs.

Prairie Stars

Featuring 15 intercollegiate NCAA Div II athletic teams.

Find your Fit

UIS has over 85 student and 10 greek life organizations, and many volunteer opportunities.

Arts & Culture

Celebrating the arts to create rich cultural experiences on campus.

Give Like a Star

Your generosity helps fuel fundraising for scholarships, programs and new initiatives.

Bragging Rights

UIS was listed No. 1 in Illinois and No. 3 in the Midwest in 2023 rankings.

- Quick links Applicants & Students Important Apps & Links Alumni Faculty and Staff Community Admissions How to Apply Cost & Aid Tuition Calculator Registrar Orientation Visit Campus Academics Register for Class Programs of Study Online Degrees & Programs Graduate Education International Student Services Study Away Student Support Bookstore UIS Life Dining Diversity & Inclusion Get Involved Health & Wellness COVID-19 United in Safety Residence Life Student Life Programs UIS Connection Important Apps UIS Mobile App Advise U Canvas myUIS i-card Balance Pay My Bill - UIS Bursar Self-Service Email Resources Bookstore Box Information Technology Services Library Orbit Policies Webtools Get Connected Area Information Calendar Campus Recreation Departments & Programs (A-Z) Parking UIS Newsroom Connect & Get Involved Update your Info Alumni Events Alumni Networks & Groups Volunteer Opportunities Alumni Board News & Publications Featured Alumni Alumni News UIS Alumni Magazine Resources Order your Transcripts Give Back Alumni Programs Career Development Services & Support Accessibility Services Campus Services Campus Police Facilities & Services Registrar Faculty & Staff Resources Website Project Request Web Services Training & Tools Academic Impressions Career Connect CSA Reporting Cybersecurity Training Faculty Research FERPA Training Website Login Campus Resources Newsroom Campus Calendar Campus Maps i-Card Human Resources Public Relations Webtools Arts & Events UIS Performing Arts Center Visual Arts Gallery Event Calendar Sangamon Experience Center for Lincoln Studies ECCE Speaker Series Community Engagement Center for State Policy and Leadership Illinois Innocence Project Innovate Springfield Central IL Nonprofit Resource Center NPR Illinois Community Resources Child Protection Training Academy Office of Electronic Media University Archives/IRAD Institute for Illinois Public Finance

Request Info

Thesis Statements

- Request Info Request info for.... Undergraduate/Graduate Online Study Away Continuing & Professional Education International Student Services General Inquiries

A strong component of academic writing that all writers must understand is the difference between subject, topic, and thesis. Knowing the difference between these three terms will help you create a strong argument for your paper. This handout is designed to help inform you about these three distinct introductory elements, and it will also help you transition from deciding on a subject you are writing about, to the essay’s topic, and finally to your overall thesis.

The subject of your paper is a broad idea that stands alone. At this point, there is no detailed information associated with it or any kind of argumentation. It serves, in essence, as a launching pad for you to form an idea, or argument, which will eventually become the purpose of your paper.

Example: Women

The topic of your paper is an evolved, narrower version of your subject. Here is where you add a detailed, more conclusive area of focus for your paper so that you can eradicate vagueness.

Example: Women in late 1990s television

The thesis acts as the final idea on which the entirety of your paper will focus. It is the central message that ties the whole paper together into one definitive purpose that prepares readers for what you are arguing.

Example : Although people may argue that television in the late 1990s helped portray women in a more honest and intrepid light, programs including Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Charmed , and Sex and the City failed to illustrate the depth and truth of womanhood, choosing to focus heavily on clichéd romantic entanglements, unbecoming pathetic quarrels, and thin temptresses adorned with fashionable costumes and bare midriffs.

Subject to Topic

The following are some suggestions to help you shift from a broad subject area to a narrow, focused topic.

Seek out narrow topics

Inappropriate.

Subject: Women

Topic: Women in history

Note: In this case, the topic is too large to create a complex thesis statement worthy of a paper. The broader the topic, the more difficulty you will have narrowing your argument enough to affect readers.

Appropriate

Topic: Famous women aviators of WWII

Note: Here the topic as narrowed down the subject by focusing on women belonging to a specific profession in a particular historical period. It is thorough enough to discover a thesis statement.

Choose arguable topics

Subject: Toni Morrison

Topic: Biography

Note: This idea does not allow for speculation or disagreement, which gives it an underdeveloped quality.

Topic: Literary merits of the novel Tar Baby

Note: This idea allows for speculation or disagreement, which gives it a strong, developed quality.

Choose topics within your comfort zone

Subject: Linguistics

Topic: OE Northumbrian dialects

Note: Unless you have studied OE Northumbrian dialects at length, it perhaps poses too high of a research challenge to pursue.

Subject: College Freshmen

Topic: The Freshman Fifteen

Note: This topic is narrow enough and familiar enough to most college students to purse as a topic.

Rules for Thesis Statements

- Needs to correspond to the assignment’s expectations

- Usually, but not always, one sentence

- Typically appears that the end of the introduction

- More often than not, it is explicitly stated

- Establishes an argument

- Establishes the criteria for scrutiny of the topic (previews the structure of the paper)

- Write for an audience. Your paper should be catchy enough to retain readers’ attention.

Determine a "Research Question"

Determining a research question is a crucial aspect of your writing. In order to stay focused on the assignment, you must form a clear and concise argument. Choose one major idea you want to concentrate on, and expand from there.

When your instructor assigns a paper, try and find some angle that makes you inspired to fulfill the assignment to the best of your abilities. For example, if your history professor assigns you to write about a historical figure who changed the world for the better, write about an individual whose work you can relate to. If you are interested in the supernatural, you could write about Joan of Arc, who became a crusader because of the visions she claimed to have had from God.

Next, ask yourself a series of questions to help form your research question. Try to avoid questions you can answer with “yes” or “no” because these will not allow you to explore your topic as thoroughly or as easily as questions that begin with “who,” “what,” “why,” or “how.”

- When did Joan rise to prominence?

- Did she develop a strong following that her enemies felt threatened by?

- How did her gender play a part in her tragic demise?

- What does Joan’s execution say about female leaders of the 15th century?

Once you have developed a series of questions, consider which questions allow you to form an argument that is not too broad that you cannot write a sufficient paper, but not too narrow that it prevents you from crafting an interesting and compelling piece of writing. Decide which question represents this criteria, then you can start researching. In this case, from the above examples, you may select “How did Joan’s gender play a part in her tragic demise?” This question will allow you to develop a complex thesis with argumentative points to pose to readers. Below is a way to develop a thesis statement from the simply worded question that was just brainstormed.

The answer to your research question can become the core of your thesis statement.

Research Question:

How did Joan of Arc’s gender play a part in her tragic demise?

Thesis Statement:

Joan of Arc’s gender played a significant role in her tragic demise because of the laws and social customs concerning women during France’s 15th century, which included social ideals that perceived women as secular citizens; political standards that favored men to hold positions of power over women; as well as religious ideals that perceived Joan’s alleged clairvoyant gifts as a natural trait of witchcraft, a crime of heresy also associated with women.

Note: Beginning writers are taught to write theses that list and outline the main points of the paper. As college students, professors might expect more descriptive theses. Doing this will illustrate two points: 1) Readers will be able to isolate your argument, which will keep them more inclined to focus on your points and whether or not they agree with you. They may find themselves questioning their own thoughts about your case. 2) A descriptive thesis serves as a way to show your understanding of the topic by providing a substantial claim.

Troubleshooting your Thesis Statement

The following are some suggestions to help you scrutinize your working draft of your thesis statement to develop it through further revisions.

Specify your details

Example: In today’s society, beauty advertisements are not mere pictures that promote vanity in the public, but instead, they inspire people to make changes so that they can lead better lifestyles.

- Uses cliché phrases like “In today’s society.”

- What kind of beauty advertisements are you referring to? All of them? Or specific kinds?

Note: Who is this targeting? Women? Men? Adolescents? Being more specific with the targeted audience is going to strengthen your paper.

Example: Makeup, clothing, and dieting advertisements endorse American ideals of female beauty and show the public that women should possess full ownership of their bodies and fight the stigma of physical and sexual repression which has been placed upon them.

- Identifies specific forms of beauty advertisements for the sake of clearly expressing a strong argument.

- Uses descriptive language.

Note: By signifying that women’s beauty is the main topic being argued in the paper, this author clearly identifies their main, targeted audience.

Make arguable claims

Undeveloped.

Example: Social media is not conducive to people’s personal growth because of the distractions, self-doubt, and social anxiety it can cause to its users.

- “Social media” and “personal growth” both encompass a large span of topics and so they leave the reader confused about the particular focus of this paper.

Note: The thesis is too broad to form a well-constructed argument. It lacks details and specificity about the paper’s points.

Example: Although Facebook allows people to network personally and professionally, the procrastination and distraction from one’s demanding responsibilities can lead people to invest more time in narcissistic trivialities, resulting in severe cases of anxiety and low self-esteem.

- It alludes to some kind of counterargument in the opening dependent clause.

- The thesis specifies several points that makes a thesis credible. The argument connects all the points (distractions, self-doubt, and social anxiety) together into one linear train of thought, relating the ideas to one another.

Note: The thesis is more focused. It concentrates on the idea that social media plays up on a person’s self-worth.

Preview the paper’s structure

Example: College is a crucial stage in one’s life that will help them become more sophisticated individuals upon entering the harsh world as an adult.

Note: Not only does this statement lack specificity and excitement, but it fails to present an idea of what the paper will look like, and how the argument is set up. As readers, we know this writer believes college is an imperative part of one’s life, but we have no idea how they are going to go about arguing that claim.

Example: College is a crucial stage in a young adult’s life because it is the time in which they begin to transition from childhood to adulthood, learn to live away from their parents, budget their own finances, and take responsibility for their successes and failures, which will force them to make more responsible decisions about their lives.

Note: The thesis points to different aspects of college life that help students ease into adulthood, which shows the reader the points the writer will explore throughout the body of the paper.

- transition from childhood to adulthood

- learn to live away from their parents

- budget their own finances

- take responsibility for their successes and failures

Final Thoughts

When you are asked to write a paper in college, there may not be as many detailed descriptions telling you what subject or argument to write about. Remember, the best way to pick your subject is to write about something that interests you. That way, the assignment will be more promising and passionate for you and may help you feel more in control of your writing.

As you venture closer to crafting your thesis, make sure your subject is narrowed down to a specific enough topic so that you can stay focused on the task. If your topic is specific enough, you will be able to create an argument that is concentrated enough for you to provide sufficient argumentative points and commentary.

Comparsion of the Differences between the 1950’s and Today

This essay about Contrasts Between the 1950s and Modern Times examines the stark differences between these two periods across technology, culture, and societal values. It highlights how the 1950s were characterized by post-war optimism and traditional family values, while modern times are marked by technological advancement, social progress, and economic disparities. Despite the nostalgia for the past, the essay emphasizes the importance of recognizing and addressing the challenges and opportunities of the present era in shaping a more equitable future.

How it works

Journey back to the 1950s, an era colored by post-war optimism and the echoes of a simpler time. In contrast, fast forward to the present day, where technology reigns supreme and societal norms have undergone profound shifts. This essay delves into the striking differences between these two periods, spanning technology, culture, and societal values.

The 1950s were characterized by a sense of innocence and wonder, with technology still in its infancy. Television was a novelty, bringing families together around the flickering glow of the screen, while computers were behemoths hidden away in research labs.

In stark contrast, the modern era is defined by the omnipresence of technology, from the palm-sized smartphones that connect us to the world, to the marvels of artificial intelligence and virtual reality that shape our daily lives.

Societal attitudes have also evolved dramatically since the 1950s. Back then, conformity and traditional family values were paramount, with gender roles firmly entrenched and diversity often overlooked. Today, however, society embraces a more inclusive and progressive mindset, championing diversity, equality, and individuality. Concepts like gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, and cultural diversity are central to contemporary discourse, reflecting a broader shift towards social justice and acceptance.

Economically, the 1950s were a time of unparalleled prosperity for many, driven by a booming manufacturing sector and the rise of the middle class. However, this prosperity was not shared equally, as marginalized groups faced systemic discrimination and limited opportunities. In contrast, the modern economy is characterized by globalization, technological innovation, and income inequality. While technological advancements have created new opportunities for wealth and growth, they have also widened the gap between the haves and the have-nots, leading to greater economic insecurity for many.

In conclusion, the differences between the 1950s and modern times are stark and profound, reflecting the ever-changing nature of human society. While the 1950s may evoke a sense of nostalgia for a simpler time, it is important to recognize the progress that has been made since then, as well as the challenges that lie ahead in our quest for a more just and equitable future.

Cite this page

Comparsion Of The Differences Between The 1950's And Today. (2024, Apr 22). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/comparsion-of-the-differences-between-the-1950s-and-today/

"Comparsion Of The Differences Between The 1950's And Today." PapersOwl.com , 22 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/comparsion-of-the-differences-between-the-1950s-and-today/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Comparsion Of The Differences Between The 1950's And Today . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/comparsion-of-the-differences-between-the-1950s-and-today/ [Accessed: 25 Apr. 2024]

"Comparsion Of The Differences Between The 1950's And Today." PapersOwl.com, Apr 22, 2024. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/comparsion-of-the-differences-between-the-1950s-and-today/

"Comparsion Of The Differences Between The 1950's And Today," PapersOwl.com , 22-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/comparsion-of-the-differences-between-the-1950s-and-today/. [Accessed: 25-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Comparsion Of The Differences Between The 1950's And Today . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/comparsion-of-the-differences-between-the-1950s-and-today/ [Accessed: 25-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Visit Guide

- Visit Information

- Interactive Campus Map

- Maps and Directions

- Parking and Accessibility

Tools & Resources

- Academic and Other College Calendars

Resources For

- Prospective Undergraduates

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Parents and Families

Faculty/Staff and Department Directories

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Search Student Directory (BiONiC)

Interviewing Chinese Adoptees for Senior Thesis

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

IIa. Topic Sentence 1: Introduce the first claim of your three-part thesis (one complete sentence) -One reason we know Odysseus to be hero is because he acts in accordance with the epic hero characteristics. A. Support Detail/example/data/explanation - Explain how an event led to an adventure or quest. Detail/example/data/explanation - Provide a quote about the Trojan War and his adventure home afterwards. Detail/example/data/explanation - Explain how his decision to partake in the war brought about his struggle to return to Ithaca.

Explanation:

Support Detail/example/data/explanation - Explain how an event led to an adventure or quest.

Related Questions

Help guys I cant fail this again I just want a correct answer so if u are not sure please dont answer and please put an explanation with it.

it seems to make the most sense AND it fits both definitions of 'balm'

before During his last visit with Dr. Lanyon, Utterson noticed Dr. Lanyon looked thin he died. O but content O and frightened O and happy O and sad

B. and frightened.

The question concerns the novella Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

The novella is about Dr. Jekyll, who invented a potion that created his personality split, Mr. Hyde.

Dr. Lanyon was a long-time friend of Dr. Jekyll, who disagreed with his experiments.

When Utterson, the lawyer, and friend of both Dr. Lanyon and Dr. Jekyll, pay a visit to Dr. Lanyon on his last bed, he noticed that he has grown thin and there was a frightened look in his eye.

So, the correct answer is option B.

Read the excerpt from Hamlet, Act I, Scene ii. Hamlet: O! that this too too solid flesh would melt, Thaw and resolve itself into a dew; Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d His canon ’gainst self-slaughter! O God! O God! How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable Seem to me all the uses of this world. Fie on ’t! O fie! ’tis an unweeded garden, That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature Possess it merely. That it should come to this! By evaluating the dramatic conventions in the excerpt, the reader can conclude that Hamlet will face both conflict and tragedy but will keep a sense of humor. be involved in conflict but the story will have a happy ending. become a tragic hero and the story will have an unhappy ending. face tragedy but will pull through and resolve his conflicts.

become a tragic hero and the story will have an unhappy ending.

I remember most of the story

3. How does the "vision softly creeping" demonstrate personification? O through dramatic irony O by giving a tone of calm O by giving the effect of suspense O by allowing vision humanlike abilities

O by allowing vision humanlike abilities

Personification is a literary device that attributes human qualities to abstract characters. Creeping is a word commonly used to describe the human attribute of sneaking in to go unnoticed.

In this phrase, 'vision' is an abstract entity that has been assigned this human character of sneaking in. The writer thus uses personification to describe a gradual movement or change in vision that could be positive or negative.

Can someone summarize this for me

The son and the mom are just not having a great time and they are out I

In "Rules of the Game," why does Waverly feel unhappy about shopping with her mother?

The leadership clumsy school is selling cupcake with the goal to raise over$ 400 for a local charity. The inequality for their goal is shown below where c is the. Number of cupcake sold

Find complete question in the comment section :

Kindly check explanation

Given that :

Number of cupcakes, c is represented by the inequality :

3c > 400

We can obtain the value of c

Divide both sides by 3

3c/3 > 400/3

c > 133.33

Hence, the correct set will be one in which all its values are greater than 133.33

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

A closer look at Republicans who favor legal abortion and Democrats who oppose it

The Republican Party platform states that “the unborn child has a fundamental right to life which cannot be infringed,” while the Democratic equivalent supports access to “safe and legal abortion.” But support for these positions is far from universal among Americans who identify with or lean toward each party, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey .

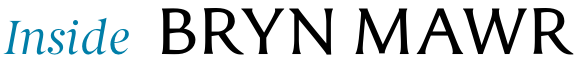

That raises the question: Who are the Republicans who support legal abortion and the Democrats who oppose it, and how else do they differ from their fellow partisans? One major difference involves religion. Republicans who favor legal abortion are far less religious than abortion opponents in the GOP, while Democrats who say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases are much more religious than Democrats who say it should be legal.

Instead of looking at the percentage of U.S. adults who support or oppose legal abortion, this analysis takes the opposite approach, examining the composition of supporters and opponents of legal abortion, including within each party. For instance, among Republicans who support legal abortion, what percentage are evangelicals, women or young people?

Pew Research Center conducted this study to take a closer look at views about abortion in the United States. This analysis takes a different approach than usual: Instead of looking at the share of adults who say abortion should be legal or illegal, it looks at the demographic and religious composition of people who support or oppose legal abortion. Results should be interpreted cautiously. For example, just because most Democrats who oppose legal abortion are not White does not mean that most Black, Hispanic or Asian Democrats oppose legal abortion. Our previously published report, “ America’s Abortion Quandary ,” includes data on many subgroups’ views toward abortion.

For this analysis, we surveyed 10,441 U.S. adults from March 7-13, 2022. Everyone who took part in the survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses, which gives nearly all U.S. adults a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology . Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology .

Among Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party who say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases, a large majority (78%) identify as conservative. But that is not the case among Republicans who support legal abortion, 53% of whom describe their political ideology as moderate or liberal. Republicans who say abortion generally should be legal also are less likely to live in the South and more likely to live in the Northeast and West – parts of the country with higher levels of support for legal abortion in general.

The religious divide on abortion is strongly apparent within the GOP. Among Republicans who generally oppose legal abortion, 62% are Protestants, including around four-in-ten (39%) who are White evangelical Protestants. And about four-in-ten Republicans who generally oppose legal abortion (39%) are highly religious, according to a scale of religious commitment based on attendance at religious services, frequency of prayer and the importance of religion in respondents’ lives. By contrast, among Republicans who say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, just 35% are Protestants and a roughly equal share are religiously unaffiliated (34%); only 6% are highly religious.

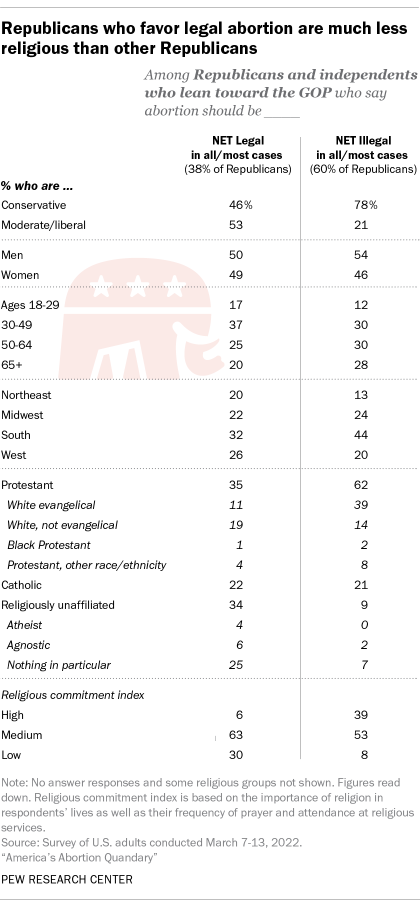

There is a similar split within the Democratic Party when it comes to abortion and political ideology. Half of Democrats and Democratic leaners who say abortion should be legal in all or most cases identify as liberal, compared with 22% among Democrats who generally oppose legal abortion.

There also are differences among Democrats by race. A majority of Democrats who favor legal abortion (56%) are White, compared with 37% among Democrats who say abortion should be mostly or entirely illegal. About half of Democrats who say abortion should be mostly or entirely illegal are either Black (23%) or Hispanic (30%). (It is worth noting, however, that most Democrats in all racial/ethnic categories say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, including 86% of White Democrats, 75% of Black Democrats, 70% of Hispanic Democrats and 81% of Asian Democrats.)

Black and Hispanic Democrats tend to be more religious than White Democrats, and indeed, Democrats who oppose legal abortion are much more likely than those who support it to be highly religious and to identify as Christian (both Catholic and Protestant). Meanwhile, 43% of Democrats who favor legal abortion are religiously unaffiliated.

Among both Republicans and Democrats, people who support legal abortion skew somewhat younger than those who oppose it.

Examining the broader composition of legal abortion supporters, opponents in the U.S.

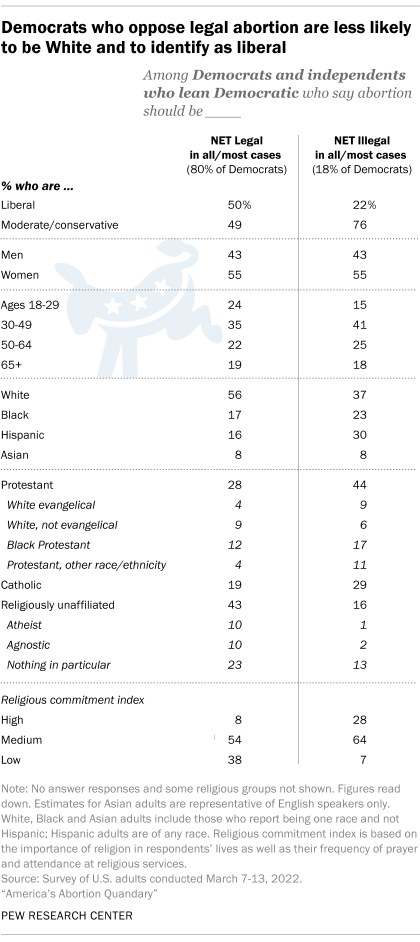

Overall, Democrats account for about two-thirds (68%) of U.S. adults who say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. That figure almost perfectly mirrors the Republican share of abortion opponents – 69% of those who say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases identify with or lean toward the Republican Party. At the same time, about one-in-four in each group buck this partisan pattern: 26% of those who favor legal abortion are Republicans, while 25% of abortion opponents are Democrats.

Those who say abortion should be legal in all cases, without exception, are considerably more likely to be Democrats than those who say it should be legal in most cases (81% vs. 62%). However, those who say abortion should be illegal in all cases are no more likely to be Republicans than those who say it should be illegal in most cases (67% vs. 69%).

A slim majority (57%) of those who say abortion should always be legal are women. At the other end of the spectrum, however, 55% of adults who say abortion should be illegal in all cases, with no exceptions, also are women.

Most supporters of legal abortion – including about two-thirds of those who say abortion should always be legal, with no exceptions – are under the age of 50. By comparison, Americans who say abortion should be mostly or entirely illegal are older, with 54% ages 50 or older.

A large majority of people who say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases are Christian, including 57% who are Protestant, 23% who are Catholic and 3% who are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, also known as Mormons. And on a scale designed to measure religious commitment based on attendance at religious services, prayer frequency and the importance of religion in one’s life, the vast majority in this group have either “high” (36%) or “medium” (56%) religious commitment; just 8% are “low” on the scale. And looking only at those who say abortion should be illegal in all cases with no exceptions, a clear majority (57%) are highly religious by this measure.

Meanwhile, nearly half of Americans who say abortion should be legal in all cases (47%) are low on the religious commitment scale, while just 4% are highly religious. About half of people at this end of the spectrum (52%) are religiously unaffiliated, including 14% who identify as atheist and 12% who are agnostic. Still, nearly four-in-ten in this group identify as Christian.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology .

Michael Lipka is an associate director focusing on news and information research at Pew Research Center

Most Popular

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.2: Identifying Thesis Statements and Topic Sentences

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 25748

Being able to identify the purpose and thesis of a text, as you’re reading it, takes practice. This section will offer you that practice.

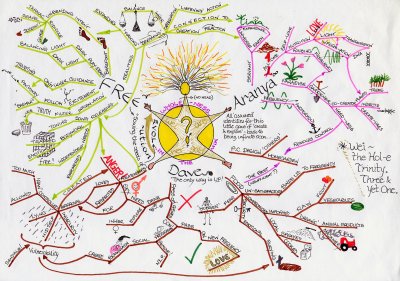

One fun strategy for developing a deeper understanding the material you’re reading is to make a visual “map” of the ideas. Mind maps, whether hand-drawn or done through computer programs, can be fun to make, and help put all the ideas of an essay you’re reading in one easy-to-read format.

Your understanding of what the “central” element of the mind map is might change as you read and re-read. Developing the central idea of your mind map is a great way to help you determine the reading’s thesis.

Figure 2.5. 1

- Hand-drawn Mind Map

Locating Explicit and Implicit Thesis Statements

In academic writing, the thesis is often explicit : it is included as a sentence as part of the text. It might be near the beginning of the work, but not always–some types of academic writing leave the thesis until the conclusion.

Journalism and reporting also rely on explicit thesis statements that appear very early in the piece–the first paragraph or even the first sentence.

Works of literature, on the other hand, usually do not contain a specific sentence that sums up the core concept of the writing. However, readers should finish the piece with a good understanding of what the work was trying to convey. This is what’s called an implicit thesis statement: the primary point of the reading is conveyed indirectly, in multiple locations throughout the work. (In literature, this is also referred to as the theme of the work.)

Academic writing sometimes relies on implicit thesis statements, as well.

This video offers excellent guidance in identifying the thesis statement of a work, no matter if it’s explicit or implicit.

Topic Sentences

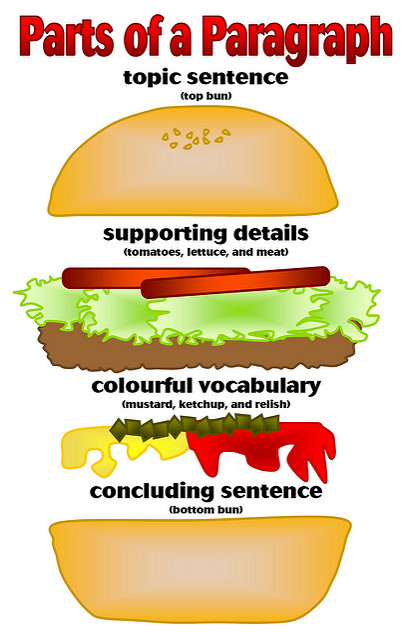

We’ve learned that a thesis statement conveys the primary message of an entire piece of text. Now, let’s look at the next level of important sentences in a piece of text: topic sentences in each paragraph.

A useful metaphor would be to think of the thesis statement of a text as a general: it controls all the major decisions of the writing. There is only one thesis statement in a text. Topic sentences, in this relationship, serve as captains: they organize and sub-divide the overall goals of a writing into individual components. Each paragraph will have a topic sentence.

Figure 2.5. 2

It might be helpful to think of a topic sentence as working in two directions simultaneously. It relates the paragraph to the essay’s thesis, and thereby acts as a signpost for the argument of the paper as a whole, but it also defines the scope of the paragraph itself. For example, consider the following topic sentence:

Many characters in Lorraine Hansberry’s play A Raisin in the Sun have one particular dream in which they are following, though the character Walter pursues his most aggressively.

If this sentence controls the paragraph that follows, then all sentences in the paragraph must relate in some way to Walter and the pursuit of his dream.

Topic sentences often act like tiny thesis statements. Like a thesis statement, a topic sentence makes a claim of some sort. As the thesis statement is the unifying force in the essay, so the topic sentence must be the unifying force in the paragraph. Further, as is the case with the thesis statement, when the topic sentence makes a claim, the paragraph which follows must expand, describe, or prove it in some way. Topic sentences make a point and give reasons or examples to support it.

The following diagram illustrates how a topic sentence can provide more focus to the general topic at hand.

Placement of Topic Sentences

What if I told you that the topic sentence doesn’t necessarily need to be at the beginning? This might be contrary to what you’ve learned in previous English or writing classes, and that’s okay. Certainly, when authors announce a topic clearly and early on in a paragraph, their readers are likely to grasp their idea and to make the connections that they want them to make.

However, when authors are writing for a more sophisticated academic audience—that is an audience of college-educated readers—they will often use more sophisticated organizational strategies to build and reveal ideas in their writing. One way to think about a topic sentence, is that it presents the broadest view of what authors want their readers to understand. This is to say that they’re providing a broad statement that either announces or brings into focus the purpose or the meaning for the details of the paragraph. If the topic sentence is seen as the broadest view, then every supporting detail will bring a narrower—or more specific—view of the same topic.

With this in mind, take some time to contemplate the diagrams in the figure below. The widest point of each diagram (the bases of the triangles) represents the topic sentence of the paragraph. As details are presented, the topic becomes narrower and more focused. The topic can precede the details, it can follow them, it can both precede and follow them, or the details can surround the topic. There are surely more alternatives than those that are presented here, but this gives you an idea of some of the possible paragraph structures and possible placements for the topic sentence of a paragraph.

Consider some of the following examples of different topic sentence placements in a paragraph from a review essay of the beloved children’s book, The Cat in the Hat , by Dr. Seuss. Paragraph structures are labeled according to the diagrams presented above, and topic sentences are identified by red text.

Topic Sentence-Details-Topic Sentence