Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Grassroots Writing Research Journal - Issue 3.1 Unknown Binding

- Language English

- ISBN-10 1609041631

- ISBN-13 978-1609041632

- See all details

Product details

- Language : English

- ISBN-10 : 1609041631

- ISBN-13 : 978-1609041632

- Item Weight : 9.9 ounces

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Chapter 1: The Introduction

1.4 Resources to Use

Melanie Gagich

Using Face-to-Face Resources

The michael schwartz library.

The library is probably the most important and useful resource you have on campus. Entrance to it is located on the 1st floor of Rhodes Tower and it consists of eight floors. At the library, you will find many resources including the following:

- Access to electronic resources, including the web, at more than 100 PCs within the Library.

- On-demand access to over 29,000 journal titles available on Library PCs and from your home computer.

- An on-site collection including 975,000 print volumes and an additional 1,000,000 items, such as sound recordings, video recordings, DVDs, and microforms.

- Friendly staff ready to help you with your information needs.

- Evening and weekend hours .

- In-person and online borrowing privileges for books from 85 OhioLINK libraries .

- Access to the SCHOLAR Library catalog , the Web, and other electronic resources from your home computer.

- The latest research databases .

- Free interlibrary loan service , providing access to an almost unlimited number of library materials owned by other libraries world-wide, through a web-based interface putting you in control of your own borrowing activities. ( “Welcome to the Library” by the Director Glenda Thornton)

Research Guides are provided for ENG 100/101 and ENG 102 as well as links to help you cite sources , access course textbook reserves , and access eBooks . You can even get a library tour or access online library tutorials to help you succeed in not only your writing classes but all of your classes.

Be sure to visit the library and see how else it can help you succeed!

The Writing Center

The Writing Center is located on the 1st floor of the library in the back left corner. You can make an appointment through Starfish, by calling 687-6981, or in person at RT 124. The Writing Center is open Monday – Thursday from 9:30am – 7:00pm and on Fridays from 9:30am – 4:00pm.

The Writing Center is not an editing service. Rather, it is a place to go and get feedback about your writing, not only your grammar. In order to get the most out of your 30-minute session, we suggest the following:

- Bring a paper with instructor feedback;

- Write at least two questions on the paper about issues you want to address;

- Bring the assignment and/or rubric so that you can get help talking out organization;

- Be polite and be on time.

The Writing Center is an excellent place to get help for all of you classes and for all assignments including but not limited to; lab reports, research papers, group projects, writing assignments, and grammar.

The Digital Design Studio

The Digital Design Studio is located on the third floor of the Michael Schwartz Library and it provides CSU students with access to software and digital tools, and individualized project consultations. You can rent equipment such as digital cameras and camcorders and other photography and video equipment, microphones, maker equipment, VR headsets, and more. You can also set up a project consultation to help you navigate multimodal, multimedia, and/or digital projects. The Digital Design Studio also created a project guide that includes links to setting up consultations, getting started on your project as well as information about digital identity and privacy , copyright , and plagiarism .

The Tutoring and Academic Success Center (TASC)

The TASC office uses “research-based strategies and approaches for learning in order to help students achieve their academic goals and ultimately to graduate. We do this in an informal, student-centered environment that assists students to not only achieve academically but to also socially integrate into college life.” They offer Success C oaching, T utoring , Supplemental instruction (SI) for various courses, and provide Structured Learning Assistance (SLA) in our ENG 101 courses. You can contact them at 216-687-2012. They are located in Main Classroom room 233 and you can visit their website here .

Structured Learning Assistance (SLA)

Structured Learning Assistance (SLA) is an academic support program that is available to students enrolled in English 101 courses. The SLA leaders work as a part of the Tutoring and Academic Success Center (TASC). SLA features weekly study and practice “labs,” or “sessions,” built into the class time in which students master course content to develop and apply specific learning strategies for the course, as well as strengthen their study skills to improve performance in their current English 101 course. The SLA lab times are formally attached to the student’s class schedule and there is no additional charge to the student for this support. These mandatory sessions are facilitated by successful upper-level students, who, in collaboration with the professor, develop collaborative learning sessions to guide students as they learn how to write. The SLA facilitators clarify lecture points for the students and assist them in understanding the expectations of the professor, while additionally focusing on improved study skills. SLA activities frequently include study guides, collaborative learning/group activities, and study skills — such as discovering your preferred learning style, efficient note-taking, and time management.

The Center for International Services & Programs (CISP)

CISP “provides services to international students through International Orientation , International Student Services , as well as domestic and international students through Education Abroad and the National Student Exchange .” Students can visit their office in Main Classroom room 412 Monday – Thursday from 1 – 3pm. For more information pertaining to the services and opportunities CISP offers please visit their website here .

The CSU Counseling Center

CSU offers counseling services to students, faculty, and staff. If you feel that you could use support for personal, academic, or other stresses or challenges and would like to speak to a CSU counselor, you can contact the Counseling Center at 216-687-2277. They are located at UN 220 and are open Monday – Friday from 9 – 5pm, with sessions are available by appointment from 8 – 5pm on weekdays. They also have walk-in appointments from 1 – 3pm Monday – Friday. If you need to speak to a counselor outside of office hours, you can still dial the Counseling Center number and you will be able to speak to someone, 24 hours a day. For more information about the CSU Counseling Center, please visit their website here.

Using Digital Resources and Tools

Some of you might be familiar with course management systems from high school while for others this might be a very new. CSU’s management is system is Blackboard. An instructor may choose to use or not use Blackboard in his or her classroom; however, the FYW program recommends that instructors do so. Your instructor is urged to use Blackboard as a way to foster communication between students and their classmates and students and their instructors. When integrated into the classroom, students will mostly likely be able to access course documents, check their grades, and participate in online discussions.

Starfish is “an online program that makes it easier for undergraduate students to communicate and make appointments with support services and faculty on campus.” Again, your instructor is urged to use Starfish in his or her classroom as a way to increase communication between professors and students.

To access Starfish, students must login to CampusNet, choose the “Students” tab, and then click the “Starfish” link. Once students are logged in, they can use Starfish to

- Find your assigned advisor

- Look for communication from your support network about your academic progress

- Schedule an appointment to meet with an advisor or tutor

- Schedule a tutorial with the Writing Center

- Schedule Supplemental Instruction (for certain courses)

- Course Conferences (with participating faculty)

For more information pertaining to Starfish, please visit their website here .

Cleveland State University Computer Labs

In order to provide opportunities for in-class drafting and research sessions, many FYW instructors will reserve a computer lab. Below are the locations of the most commonly used computer labs:

Mobile Campus

Because of the limited amount of available computer labs, instructors might require students to bring and use laptop computers during class. Since not all students own or have access to a laptop, CSU offers a Mobile Campus, a 48-hour laptop loan service. Students can find Mobile Campus in the Student Center room 128A and at the circulation desk in the Michael Schwartz library. For more information, please visit Mobile Campus’s website here .

Information Services and Technology (IS&T)

IS&T provides computer assistance to CSU students with student-owned PCs, Macs, and laptops. Services include system and disc clean-up, anti-spy and anti-virus software, software installation, virus removal, and printing help. To contact the IS&T help desk, call 687-5050, email [email protected], or visit RT 1106 between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. Monday through Friday.

Using Microsoft OneNote

See the Dr. Julie Townsend’s video below to help you use Microsoft OneNote:

Julie Townsend. “OneNote Walkthrough,” 4 August 2020, Youtube.

University Resources

Office of disability services (ods).

The following statement should appear in your syllabus: Note for Students with Disabilities: Educational access is the provision of classroom accommodations, auxiliary aids and services to ensure equal educational opportunities for all students regardless of their disability. Any student who feels he or she may need an accommodation based on the impact of a disability should contact the Office of Disability Services at (216) 687-2015. The Office is located in MC147. Accommodations need to be requested in advance and will not be granted retroactively.

For more information, please refer to the ODS web page at http://www.csuohio.edu/offices/disability/faculty/index.html .

The Community Assessment Response & Evaluation (CARE) Team

The CARE team “collaboratively […] support[s] the wellbeing and safety of students, faculty, staff, and to promote a culture on campus that encourages reporting of concerns.” The CARE Team can help students receive suicide prevention counseling, health and wellness resources, access CSU’s food pantry, and more. You can visit the CARE Team office in the Student Center room 319 or reach them by calling 216 -687-2048. For more information please visit https://www.csuohio.edu/care/csu-care-team and use the links on the righthand side to navigate the site.

A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing by Melanie Gagich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Feedback/Errata

Comments are closed.

ISU Writing Program

Current Issue

Grassroots writing research journal 14.2.

The Grassroots Writing Research Journal current issue is only available through Illinois State University bookstores, not through other vendors.

You can get a copy from ISU’s Redbird Spirit Shop at two locations: on North Street and in the Bone Student Center.

If one bookstore is sold out, contact the other bookstore to get a copy.

GWRJ Current Issue Preview

Preview GWRJ current issue

articles and authors

GWRJ Issues Online

GWRJ current issues will be available online in January (for Fall publications)

and May (for Spring publications)

at GWRJ Past Issues

9.1 Breaking the Whole into Its Parts

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify and explain ethos, logos, pathos, and kairos.

- Identify and analyze logical fallacies used in persuasion.

- Explain how rhetorical strategies are used in real-life situations.

Communicative situations nearly always contain rhetoric , the craft of persuading through writing or speaking. Think of your earliest instances of communication with parents or caregivers. Before you were proficient in language, you learned to navigate situations with your other senses, such as sight, sound, and touch. Consider people’s facial expressions and tones of voice. How did you know when they were pleased, displeased, or confused by your actions? The emphasis is on the word how , because the how is what starts you on the path of analyzing the forms, intent, and effectiveness of communication. The point is that even facial expressions and tones of voice serve communicative functions and contain a rhetoric that one can observe, process, and analyze.

Now, as an adult, you have learned to use rhetoric to be persuasive and to recognize when others are trying to persuade you. Imagine the following situation. A basic question arises among roommates: Where should we go for dinner? Your roommates want to go to Emiliano’s Pizza Pavilion again, and their reasoning seems sound. First, having tried all pizza places in town, they know Emiliano makes the tastiest pizza—just the right combination of spices, vegetables, and cheese, all perfectly baked in the right oven at the right temperature. Furthermore, the pizza is fairly cheap and probably will provide leftovers for tomorrow. And they add that you don’t really want to stay home all alone by yourself.

You, on the other hand, are less keen on the idea; maybe you’re tired of Emiliano’s pizza or of pizza in general. You seem resistant to their suggestion, so they continue their attempts at persuasion by trying different tactics. They tell you that “everyone” is going to Emiliano’s, not only because the food is good but because it’s the place to be on a Thursday evening, hoping that others’ decisions might convince you. Plus, Emiliano’s has “a million things on the menu,” so if you don’t want pizza, you can have “anything you want.” This evidence further strengthens their argument, or so they think.

Your roommates continue, playing on your personal experience, adding that the last time you didn’t join them, you went somewhere else and then got the flu, so you shouldn’t make the same mistake twice. They add details and try to entice you with images of the pizza—a delicious, jeweled circle of brilliant color that tastes like heaven, with bubbling cheese calling out to you to devour it. Finally, they try an extreme last-ditch accusation. They claim you could be hostile to immigrants such as Emiliano and his Haitian and Dominican staff, who are trying to succeed in the competitive pizza market, so your unwillingness to go will hurt their chances of making a living.

However, because you know something about rhetoric and how your roommates are using it to persuade, you can deconstruct their reasoning, some of which is flawed or even deceptive. Your decision is up to you, of course, and you will make it independent of (or dependent on) these rhetorical appeals and strategies.

Rhetorical Strategies

As part of becoming familiar with rhetorical strategies in real life, you will recognize three essential building blocks of rhetoric:

- Ethos is the presentation of a believable, authoritative voice that elicits an audience’s trust. In the case of the pizza example, the roommates have tried all other pizzerias in town and have a certain expertise.

- Pathos is the use of appeals to feelings and emotions shared by an audience. Emiliano’s pizza tastes good, so it brings pleasure. Plus, you don’t want to be all alone when others are enjoying themselves, nor do you want to feel responsible for the pizzeria’s economic decline.

- Logos is the use of credible information—facts, reasons, examples—that moves toward a sensible and acceptable conclusion. Emiliano’s is good value for the money and provides leftovers.

In addition to these strategies, the roommates in the example use more subtle ones, such as personification and sensory language. Personification is giving an inanimate object human traits or abilities (the cheese is calling out). Sensory language appeals to the five senses (a delicious, jeweled circle of brilliant color).

Logical Fallacies

Familiar with the three main rhetorical strategies and literary language, you also recognize the “sneakier” uses of flawed reasoning, also known as logical fallacies . Some of the roommates’ appeals are based on these fallacies:

- Bandwagon : argument that everyone is doing something, so you shouldn’t be left behind by not doing it too. “Everyone” goes to Emiliano’s, especially on Thursdays.

- Hyperbole : exaggeration. Emiliano’s has “a million things on the menu,” and you can get “anything you want.”

- Ad hominem : attacking the person, not the argument. Because you are hesitant about joining your roommates, you are accused of hostility toward immigrants.

- Causal fallacy : claiming or implying that an event that follows another event is the result of it. Because you ate elsewhere, you got the flu.

- Slippery slope : argument that a single action could lead to disastrous consequences. If Emiliano’s misses your business, they may go bankrupt.

In a matter of minutes, your roommates use all these strategies to try to persuade you to act or to agree with their thinking. Identifying and understanding such strategies, and others, is a key element of critical thinking. You can learn more about logical fallacies at the Purdue University Online Writing Lab .

As a whole, rhetoric also depends on another Greek rhetorical strategy, kairos . Kairos is the idea that timing is important in trying to persuade an audience. An appeal may succeed or fail depending on when it is made. The moment must be right, and an effective communicator needs to be aware of their audience in terms of kairos. Going back to the roommates and pizza example, kairos might be an influence in your decision; if you were tired of pizza, had to save money, or wanted to study alone, your roommates would have less chance of persuasion. As a more serious example, if a recent series of car accidents has caused serious injuries on the freeway, an audience might be more receptive to a proposal to reassess speed limits and road signage. Awareness of rhetorical strategies in everyday situations such as this will help you recognize and evaluate them in matters ultimately more significant than pizza.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/9-1-breaking-the-whole-into-its-parts

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Multicultural Text, Intercultural Performance: The Performance Ecology of Contemporary Toronto

Cite this chapter.

- Ric Knowles

Part of the book series: Performance Interventions ((PIPI))

147 Accesses

2 Citations

In its promotional material the city of Toronto regularly makes two significant claims: to be the world’s most multicultural city, and to be the third most active theatre center in the English-speaking world. This chapter looks at the relationships between these claims, and positions theatrical activity within the city in relation to Canada’s official multicultural policy. It articulates multicultural texts — the policies, documents, and official discourses of Canadian multiculturalism — against intercultural performance — the complex ecology of grassroots interculturalism that plays itself out among the many intercultural theatre companies within the city who attempt to construct culturally alternative communities and solidarities across difference.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Works cited

Abu-Laban, Yasmeen, and Christina Gabriel. Selling Diversity: Immigration, Multiculturalism, Employment Equity, and Globalization . Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2002.

Google Scholar

Aquino, Nina Lee. Personal Interview. Distillery District, Toronto. 22 October 2006.

Bannerji, Himani. The Dark Side of the Nation: Essays on Multicutluralism, Nationalism, and Gender . Toronto: Canadian Scholars, 2000.

Berdichewsky, Bernardo. Racism, Ethnicity and Multiculturalism . Vancouver: Future, 1994.

Bharucha, Rustom. Theatre and the World: Performance and the Politics of Culture . London: Routledge, 1993.

—. The Politics of Cultural Practice: Thinking Through Theatre in an Age of Globalization . Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2000.

Bibby, Reginald W. Mosaic Madness: The Poverty and Potential Life in Canada . Toronto: Stoddart, 1990.

Bissoondath, Neil. Selling Illusions: The Cult of Multiculturalism in Canada . Toronto: Penguin, 1994.

Breton, Raymond. ‘Multiculturalism and Canadian Nation Building.’ The Politics of Gender, Ethnicity and Language in Canada . Ed. Alan Cairns and Cynthia Williams. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986: 27–66.

Carter, Jill. ‘Writing, Righting, “Riting” — The Scrubbing Project : Re-Members a New “Nation” and Reconfigures Ancient Ties.’ alt.theatre: cultural diversity and the stage 4.4 (2006): 13–17.

Carter, Tom, Marc Vachon, John Biles, Erin Tolley, and Jim Zamprelli. Introduction. Our Diverse Cities: Challenges and Opportunities . Special issue, Canadian Journal of Urban Research 15.2 Supplement (2006): i–viii.

Certeau, Michel de. The Practice of Everyday Life . Trans. Stephen Randall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Eliot, T. S. ‘The Wasteland.’ The Complete Plays and Poems1909–1950 . New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1971: 37–55.

Esses, Victoria M., and R. C. Gardner. ‘Multiculturalism in Canada: Context and Current Status.’ Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science 28.3 (1996): 145–60.

Article Google Scholar

Foster, Cecil. Where Race Does Not Matter . Toronto: Penguin, 2005.

Foucault, Michel. ‘Of Other Spaces.’ Diacritics 16.1 (1986): 22–7.

Gómez, Mayte [María Theresa]. ‘“Coming Together” in Lift Off’93: Intercultural Theatre in Toronto and Canadian Multiculturalism.’ Essays in Theatre/Études théâtrales 13.1 (1991): 45–60.

Gwyn, Richard. Nationalism Without Walls: The Unbearable Lightness of Being Canadian . Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995.

Gunew, Sneja. Haunted Nations: The Colonial Dimensions of Multiculturalisms . London: Routledge, 2004.

Hetherington, Kevin. The Badlands of Modernity: Heterotopia and Social Ordering . London: Routledge, 1997.

Book Google Scholar

Kamboureli, Smaro. Introduction. Making a Difference: Canadian Multicultural Literature . Ed. Smaro Kamboureli. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1996. 1–16.

—. Scandalous Bodies: Diasporic Literature in English Canada . Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Kershaw. Baz. ‘Oh for Unruly Audiences! Or, Patterns of Participation in Twentieth-Century Theatre.’ Modern Drama 42.2 (1998): 133–54.

—. ‘The Theatrical Bisophere and Ecologies of Performance.’ New Theatre Quarterly 16.2 (2000): 122–30.

Li, Peter. ‘A World Apart: The Multicultural World of Visible Minorities and the Art World of Canada.’ Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 31.4 (1994): 365–91.

Majumdar, Anita. Personal Interview. Epicure Café, Toronto. 7 March 2007.

McClintock, Anne, Aamir Mufti, and Ella Shohot, ed. Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation, and Postcolonial Perspectives . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Modern Times Stage Company. bloom . By Guillermo Verdecchia, directed by Soheil Parsa. Program. 24 February – 19 March 2006.

Moss, Laura. Is Canada Postcolonial: Unsettling Canadian Literature . Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2003.

Multiculturalism and Citizenship Canada. The Canadian Multiculturalism Act: A Guide for Canadians . Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1991.

Native Earth Performing Arts. Honouring Theatre . Program. Fall 2006.

Nolan, Yvette. ‘Death of a Chief: An Interview with Yvette Nolan.’ Interview with Sorouja Moll. Native Earth Performing Arts Office, Distillery District, Toronto. 12 March 2006. 7 July 2006: < http://www.canadianshakespeares.ca /i_ynolan2.cfm>.

—. Personal Interview. Native Earth Performing Arts Office, Distillery District, Toronto. 29 June 2006.

Philip, Marlene NourbeSe. ‘Signifying: Why the Media Have Fawned Over Bissoondath’s Selling Illusions.’ Border/Lines 36 (1995): 4–11.

Qadeer, Mohammed, and Sandeep Kumar. ‘Ethnic Enclaves and Social Cohesion.’ Our Diverse Cities: Challenges and Opportunities . Special issue, Canadian Journal of Urban Research . 15.2 Supplement (2006): 1–17.

Reitz, J. G., and Raymond Breton. The Illusion of Difference: Realities of Ethnicity in Canada and the United States . Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute, 1994.

Sears, Djanet. Harlem Duet . Winnipeg: Scirocco, 1997.

Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media . London: Routledge, 1994.

Slemon, Stephen. ‘Resistance Theory for the Second World.’ Postcolonial Studies Reader . Ed. Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. London: Routledge, 1995: 104–10.

Spencer, Rhoma. Interview with Andy Barry. ‘Metro Morning.’ CBC Radio, Toronto. 23 May 2006.

Turtle Gals Performance Ensemble. Information Sheet. Turtle Gals Performance Ensemble office files.

—. The Scrubbing Project . Unpublished playscript, 2005.

Weimann, Robert. Author’s Pen and Actor’s Voice: Playing and Writing in Shakespeare’s Theatre . Ed. Helen Higbee and William West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Chapter Google Scholar

Worthen, W. B. Shakespeare and the Force of Modern Performance . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

San Diego State University, USA

D. J. Hopkins ( Assistant Professor, Head of Theatre Studies, and Director of the MA Program in Theatre ) & Shelley Orr ( teaches script analysis, dramaturgy, theatre history, and performance theory in the School of Theatre, Television, and Film ) ( Assistant Professor, Head of Theatre Studies, and Director of the MA Program in Theatre ) & ( teaches script analysis, dramaturgy, theatre history, and performance theory in the School of Theatre, Television, and Film )

University of Western Ontario, Canada

Kim Solga ( Assistant Professor of English ) ( Assistant Professor of English )

Copyright information

© 2009 Ric Knowles

About this chapter

Knowles, R. (2009). Multicultural Text, Intercultural Performance: The Performance Ecology of Contemporary Toronto. In: Hopkins, D.J., Orr, S., Solga, K. (eds) Performance and the City. Performance Interventions. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-30521-2_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-30521-2_5

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-0-230-30049-1

Online ISBN : 978-0-230-30521-2

eBook Packages : Palgrave Social & Cultural Studies Collection Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

13.1.3: Social Movements

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 120306

Social movements are purposeful, organized groups that strive to work toward a common social goal. While most of us learned about social movements in history classes, we tend to take for granted the fundamental changes they caused —and we may be completely unfamiliar with the trend toward global social movements. But from the antitobacco movement that has worked to outlaw smoking in public buildings and raise the cost of cigarettes, to political uprisings throughout the Arab world, movements are creating social change on a global scale.

Levels of Social Movements

Movements happen in our towns, in our nation, and around the world. Let’s take a look at examples of social movements, from local to global. No doubt you can think of others on all of these levels, especially since modern technology has allowed us a near-constant stream of information about the quest for social change around the world.

Chicago is a city of highs and lows, from corrupt politicians and failing schools to innovative education programs and a thriving arts scene. Not surprisingly, it has been home to a number of social movements over time. Currently, AREA Chicago is a social movement focused on “building a socially just city” (AREA Chicago 2011). The organization seeks to “create relationships and sustain community through art, research, education, and activism” (AREA Chicago 2011). The movement offers online tools like the Radicalendar––a calendar for getting radical and connected––and events such as an alternative to the traditional Independence Day picnic. Through its offerings, AREA Chicago gives local residents a chance to engage in a movement to help build a socially just city.

Texas Secede! is an organization which would like Texas to secede from the United States. (Photo courtesy of Tim Pearce/flickr)

At the other end of the political spectrum from AREA Chicago is the Texas Secede! social movement in Texas. This statewide organization promotes the idea that Texas can and should secede from the United States to become an independent republic. The organization, which as of 2014 has over 6,000 “likes” on Facebook, references both Texas and national history in promoting secession. The movement encourages Texans to return to their rugged and individualistic roots, and to stand up to what proponents believe is the theft of their rights and property by the U.S. government (Texas Secede! 2009).

A polarizing national issue that has helped spawn many activist groups is gay marriage. While the legal battle is being played out state by state, the issue is a national one.

The Human Rights Campaign, a nationwide organization that advocates for LGBT civil rights, has been active for over thirty years and claims more than a million members. One focus of the organization is its Americans for Marriage Equality campaign. Using public celebrities such as athletes, musicians, and political figures, it seeks to engage the public in the issue of equal rights under the law. The campaign raises awareness of the over 1,100 different rights, benefits, and protections provided on the basis of marital status under federal law and seeks to educate the public about why these protections should be available to all committed couples regardless of gender (Human Rights Campaign 2014).

A movement on the opposite end is the National Organization for Marriage, an organization that funds campaigns to stop same-sex marriage (National Organization for Marriage 2014). Both these organizations work on the national stage and seek to engage people through grassroots efforts to push their message. In February 2011, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder released a statement saying President Barack Obama had concluded that “due to a number of factors, including a documented history of discrimination, classification based on sexual orientation should be subject to a more heightened standard of scrutiny.” The statement said, “Section 3 of DOMA [the Defense of Marriage Act of 1993], as applied to legally married same-sex couples, fails to meet that standard and is therefore unconstitutional.” With that the Department was instructed not to defend the statute in such cases (Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs 2011; AP/Huffington Post 2011).

At the time of this writing, more than thirty states and the District of Columbia allow marriage for same-sex couples. State constitutional bans are more difficult to overturn than mere state bans because of the higher threshold of votes required to change a constitution. Now that the Supreme Court has stricken a key part of the Defense of Marriage Act, same-sex couples married in states that allow it are now entitled to federal benefits afforded to heterosexual couples (CNN 2014). (Photo courtesy of Jose Antonio Navas/flickr).

Social organizations worldwide take stands on such general areas of concern as poverty, sex trafficking, and the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in food. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are sometimes formed to support such movements, such as the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movement (FOAM). Global efforts to reduce poverty are represented by the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief (OXFAM), among others. The Fair Trade movement exists to protect and support food producers in developing countries. Occupy Wall Street, although initially a local movement, also went global throughout Europe and, as the chapter’s introductory photo shows, the Middle East.

Types of Social Movements

We know that social movements can occur on the local, national, or even global stage. Are there other patterns or classifications that can help us understand them? Sociologist David Aberle (1966) addresses this question by developing categories that distinguish among social movements based on what they want to change and how much change they want. Reform movementsseek to change something specific about the social structure. Examples include antinuclear groups, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), the Dreamers movement for immigration reform, and the Human Rights Campaign’s advocacy for Marriage Equality. Revolutionary movements seek to completely change every aspect of society. These include the 1960s counterculture movement, including the revolutionary group The Weather Underground, as well as anarchist collectives. Texas Secede! is a revolutionary movement. Religious/Redemptive movements are “meaning seeking,” and their goal is to provoke inner change or spiritual growth in individuals. Organizations pushing these movements include Heaven’s Gate or the Branch Davidians. The latter is still in existence despite government involvement that led to the deaths of numerous Branch Davidian members in 1993.Alternative movements are focused on self-improvement and limited, specific changes to individual beliefs and behavior. These include trends like transcendental meditation or a macrobiotic diet. Resistance movements seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure. The Ku Klux Klan, the Minutemen, and pro-life movements fall into this category.

Stages of Social Movements

Later sociologists studied the lifecycle of social movements—how they emerge, grow, and in some cases, die out. Blumer (1969) and Tilly (1978) outline a four-stage process. In the preliminary stage , people become aware of an issue, and leaders emerge. This is followed by the coalescence stage when people join together and organize in order to publicize the issue and raise awareness. In the institutionalization stage , the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism: it is an established organization, typically with a paid staff. When people fall away and adopt a new movement, the movement successfully brings about the change it sought, or when people no longer take the issue seriously, the movement falls into the decline stage . Each social movement discussed earlier belongs in one of these four stages. Where would you put them on the list?

SOCIAL MEDIA AND SOCIAL CHANGE: A MATCH MADE IN HEAVEN

In 2008, Obama’s campaign used social media to tweet, like, and friend its way to victory. (Photo courtesy of bradleyolin/flickr)

Chances are you have been asked to tweet, friend, like, or donate online for a cause. Maybe you were one of the many people who, in 2010, helped raise over $3 million in relief efforts for Haiti through cell phone text donations. Or maybe you follow presidential candidates on Twitter and retweet their messages to your followers. Perhaps you have “liked” a local nonprofit on Facebook, prompted by one of your neighbors or friends liking it too. Nowadays, social movements are woven throughout our social media activities. After all, social movements start by activating people.

Referring to the ideal type stages discussed above, you can see that social media has the potential to dramatically transform how people get involved. Look at stage one, the preliminary stage : people become aware of an issue, and leaders emerge. Imagine how social media speeds up this step. Suddenly, a shrewd user of Twitter can alert his thousands of followers about an emerging cause or an issue on his mind. Issue awareness can spread at the speed of a click, with thousands of people across the globe becoming informed at the same time. In a similar vein, those who are savvy and engaged with social media emerge as leaders. Suddenly, you don’t need to be a powerful public speaker. You don’t even need to leave your house. You can build an audience through social media without ever meeting the people you are inspiring.

At the next stage, the coalescence stage , social media also is transformative. Coalescence is the point when people join together to publicize the issue and get organized. President Obama’s 2008 campaign was a case study in organizing through social media. Using Twitter and other online tools, the campaign engaged volunteers who had typically not bothered with politics and empowered those who were more active to generate still more activity. It is no coincidence that Obama’s earlier work experience included grassroots community organizing. What is the difference between his campaign and the work he did in Chicago neighborhoods decades earlier? The ability to organize without regard to geographical boundaries by using social media. In 2009, when student protests erupted in Tehran, social media was considered so important to the organizing effort that the U.S. State Department actually asked Twitter to suspend scheduled maintenance so that a vital tool would not be disabled during the demonstrations.

So what is the real impact of this technology on the world? Did Twitter bring down Mubarak in Egypt? Author Malcolm Gladwell (2010) doesn’t think so. In an article in New Yorker magazine, Gladwell tackles what he considers the myth that social media gets people more engaged. He points out that most of the tweets relating to the Iran protests were in English and sent from Western accounts (instead of people on the ground). Rather than increasing engagement, he contends that social media only increases participation; after all, the cost of participation is so much lower than the cost of engagement. Instead of risking being arrested, shot with rubber bullets, or sprayed with fire hoses, social media activists can click “like” or retweet a message from the comfort and safety of their desk (Gladwell 2010).

There are, though, good cases to be made for the power of social media in propelling social movements. In the article, “Parrhesia and Democracy: Truth-telling, WikiLeaks and the Arab Spring,” Theresa Sauter and Gavin Kendall (2011) describe the importance of social media in the Arab Spring uprisings. Parrhesia means “the practice of truth-telling,” which describes the protestors’ use of social media to make up for the lack of coverage and even misrepresentation of events by state-controlled media. The Tunisian blogger Lina Ben Mhenni posted photographs and videos on Facebook and Twitter of events exposing the violence committed by the government. In Egypt the journalist Asmaa Mahfouz used Facebook to gather large numbers of people in Tahrir Square in the capital city of Cairo. Sauter and Kendall maintain that it was the use of Web 2.0 technologies that allowed activists not only to share events with the world but also to organize the actions.

When the Egyptian government shut down the Internet to stop the use of social media, the group Anonymous, a hacking organization noted for online acts of civil disobedience initiated "Operation Egypt" and sent thousands of faxes to keep the public informed of their government's activities (CBS Interactive Inc. 2014) as well as attacking the government's web site (Wagensiel 2011). In its Facebook press release the group stated the following: "Anonymous wants you to offer free access to uncensored media in your entire country. When you ignore this message, not only will we attack your government websites, Anonymous will also make sure that the international media sees the horrid reality you impose upon your people."

Sociologists have identified high-risk activism, such as the civil rights movement, as a “strong-tie” phenomenon, meaning that people are far more likely to stay engaged and not run home to safety if they have close friends who are also engaged. The people who dropped out of the movement––who went home after the danger got too great––did not display any less ideological commitment. But they lacked the strong-tie connection to other people who were staying. Social media, by its very makeup, is “weak-tie” (McAdam and Paulsen 1993). People follow or friend people they have never met. But while these online acquaintances are a source of information and inspiration, the lack of engaged personal contact limits the level of risk we’ll take on their behalf.

After a devastating earthquake in 2010, Twitter and the Red Cross raised millions for Haiti relief efforts through phone donations alone. (Photo courtesy of Cambodia4KidsOrg/flickr)

Theoretical Perspectives on Social Movements

Most theories of social movements are called collective action theories, indicating the purposeful nature of this form of collective behavior. The following three theories are but a few of the many classic and modern theories developed by social scientists.

Resource Mobilization

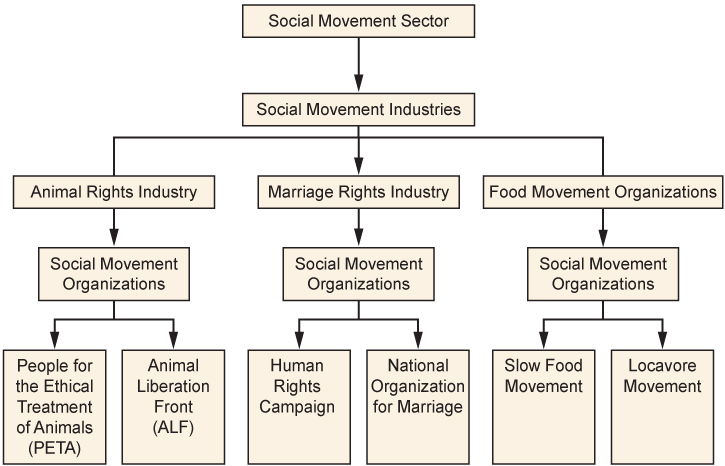

McCarthy and Zald (1977) conceptualize resource mobilization theory as a way to explain movement success in terms of the ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals. Resources are primarily time and money, and the more of both, the greater the power of organized movements. Numbers of social movement organizations (SMOs), which are single social movement groups, with the same goals constitute a social movement industry (SMI). Together they create what McCarthy and Zald (1977) refer to as "the sum of all social movements in a society."

Resource Mobilization and the Civil Rights Movement

An example of resource mobilization theory is activity of the civil rights movement in the decade between the mid 1950s and the mid 1960s. Social movements had existed before, notably the Women's Suffrage Movement and a long line of labor movements, thus constituting an existing social movement sector, which is the multiple social movement industries in a society, even if they have widely varying constituents and goals. The civil rights movement had also existed well before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white man. Less known is that Parks was a member of the NAACP and trained in leadership (A&E Television Networks, LLC. 2014). But her action that day was spontaneous and unplanned (Schmitz 2014). Her arrest triggered a public outcry that led to the famous Montgomery bus boycott, turning the movement into what we now think of as the "civil rights movement" (Schmitz 2014).

Mobilization had to begin immediately. Boycotting the bus made other means of transportation necessary, which was provided through car pools. Churches and their ministers joined the struggle, and the protest organization In Friendship was formed as well as The Friendly Club and the Club From Nowhere. A social movement industry, which is the collection of the social movement organizations that are striving toward similar goals, was growing.

Martin Luther King Jr. emerged during these events to become the charismatic leader of the movement, gained respect from elites in the federal government, and aided by even more emerging SMOs such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), among others. Several still exist today. Although the movement in that period was an overall success, and laws were changed (even if not attitudes), the "movement" continues. So do struggles to keep the gains that were made, even as the U.S. Supreme Court has recently weakened the Voter Rights Act of 1965, once again making it more difficult for black Americans and other minorities to vote.

Multiple social movement organizations concerned about the same issue form a social movement industry. A society’s many social movement industries comprise its social movement sector. With so many options, to whom will you give your time and money?

Framing/Frame Analysis

Over the past several decades, sociologists have developed the concept of frames to explain how individuals identify and understand social events and which norms they should follow in any given situation (Goffman 1974; Snow et al. 1986; Benford and Snow 2000). Imagine entering a restaurant. Your “frame” immediately provides you with a behavior template. It probably does not occur to you to wear pajamas to a fine-dining establishment, throw food at other patrons, or spit your drink onto the table. However, eating food at a sleepover pizza party provides you with an entirely different behavior template. It might be perfectly acceptable to eat in your pajamas and maybe even throw popcorn at others or guzzle drinks from cans.

Successful social movements use three kinds of frames (Snow and Benford 1988) to further their goals. The first type,diagnostic framing, states the problem in a clear, easily understood way. When applying diagnostic frames, there are no shades of gray: instead, there is the belief that what “they” do is wrong and this is how “we” will fix it. The anti-gay marriage movement is an example of diagnostic framing with its uncompromising insistence that marriage is only between a man and a woman. Prognostic framing, the second type, offers a solution and states how it will be implemented. Some examples of this frame, when looking at the issue of marriage equality as framed by the anti-gay marriage movement, include the plan to restrict marriage to “one man/one woman” or to allow only “civil unions” instead of marriages. As you can see, there may be many competing prognostic frames even within social movements adhering to similar diagnostic frames. Finally, motivational framingis the call to action: what should you do once you agree with the diagnostic frame and believe in the prognostic frame? These frames are action-oriented. In the gay marriage movement, a call to action might encourage you to vote “no” on Proposition 8 in California (a move to limit marriage to male-female couples), or conversely, to contact your local congressperson to express your viewpoint that marriage should be restricted to male-female couples.

With so many similar diagnostic frames, some groups find it best to join together to maximize their impact. When social movements link their goals to the goals of other social movements and merge into a single group, a frame alignment process(Snow et al. 1986) occurs—an ongoing and intentional means of recruiting participants to the movement.

This frame alignment process has four aspects: bridging, amplification, extension, and transformation. Bridging describes a “bridge” that connects uninvolved individuals and unorganized or ineffective groups with social movements that, though structurally unconnected, nonetheless share similar interests or goals. These organizations join together to create a new, stronger social movement organization. Can you think of examples of different organizations with a similar goal that have banded together?

In the amplification model, organizations seek to expand their core ideas to gain a wider, more universal appeal. By expanding their ideas to include a broader range, they can mobilize more people for their cause. For example, the Slow Food movement extends its arguments in support of local food to encompass reduced energy consumption, pollution, obesity from eating more healthfully, and more.

In extension , social movements agree to mutually promote each other, even when the two social movement organization’s goals don’t necessarily relate to each other’s immediate goals. This often occurs when organizations are sympathetic to each others’ causes, even if they are not directly aligned, such as women’s equal rights and the civil rights movement.

Extension occurs when social movements have sympathetic causes. Women’s rights, racial equality, and LGBT advocacy are all human rights issues. (Photos (a) and (b) courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; Photo (c) courtesy of Charlie Nguyen/flickr)

Transformation means a complete revision of goals. Once a movement has succeeded, it risks losing relevance. If it wants to remain active, the movement has to change with the transformation or risk becoming obsolete. For instance, when the women’s suffrage movement gained women the right to vote, members turned their attention to advocating equal rights and campaigning to elect women to office. In short, transformation is an evolution in the existing diagnostic or prognostic frames that generally achieves a total conversion of the movement.

New Social Movement Theory

New social movement theory, a development of European social scientists in the 1950s and 1960s, attempts to explain the proliferation of postindustrial and postmodern movements that are difficult to analyze using traditional social movement theories. Rather than being one specific theory, it is more of a perspective that revolves around understanding movements as they relate to politics, identity, culture, and social change. Some of these more complex interrelated movements include ecofeminism, which focuses on the patriarchal society as the source of environmental problems, and the transgender rights movement. Sociologist Steven Buechler (2000) suggests that we should be looking at the bigger picture in which these movements arise—shifting to a macro-level, global analysis of social movements.

The Movement to Legalize Marijuana

The early history of marijuana in the United States includes its use as an over-the-counter medicine as well as various industrial applications. Its recreational use eventually became a focus of regulatory concern. Public opinion, swayed by a powerful propaganda campaign by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics in the 1930s, remained firmly opposed to the use of marijuana for decades. In the 1936 church-financed propaganda film "Reefer Madness," marijuana was portrayed as a dangerous drug that caused insanity and violent behavior.

One reason for the recent shift in public attitudes about marijuana, and the social movement pushing for its decriminalization, is a more-informed understanding of its effects that largely contradict its earlier characterization. The public has also become aware that penalties for possession have been significantly disproportionate along racial lines. U.S. Census and FBI data reveal that blacks in the United States are between two to eight times more likely than whites to be arrested for possession of marijuana (Urbina 2013; Matthews 2013). Further, the resulting incarceration costs and prison overcrowding are causing states to look closely at decriminalization and legalization.

In 2012, marijuana was legalized for recreational purposes in Washington and Colorado through ballot initiatives approved by voters. While it remains a Schedule One controlled substance under federal law, the federal government has indicated that it will not intervene in state decisions to ease marijuana laws.

Social movements are purposeful, organized groups, either with the goal of pushing toward change, giving political voice to those without it, or gathering for some other common purpose. Social movements intersect with environmental changes, technological innovations, and other external factors to create social change. There are a myriad of catalysts that create social movements, and the reasons that people join are as varied as the participants themselves. Sociologists look at both the macro- and microanalytical reasons that social movements occur, take root, and ultimately succeed or fail.

Section Quiz

If we divide social movements according to their positions among all social movements in a society, we are using the __________ theory to understand social movements.

- new social movement

- resource mobilization

- value-added

While PETA is a social movement organization, taken together, the animal rights social movement organizations PETA, ALF, and Greenpeace are a __________.

- social movement industry

- social movement sector

- social movement party

- social industry

Social movements are:

- disruptive and chaotic challenges to the government

- ineffective mass movements

- the collective action of individuals working together in an attempt to establish new norms beliefs, or values

- the singular activities of a collection of groups working to challenge the status quo

When the League of Women Voters successfully achieved its goal of women being allowed to vote, they had to undergo frame __________, a means of completely changing their goals to ensure continuing relevance.

- amplification

- transformation

If a movement claims that the best way to reverse climate change is to reduce carbon emissions by outlawing privately owned cars, “outlawing cars” is the ________.

- prognostic framing

- diagnostic framing

- motivational framing

- frame transformation

Short Answer

Think about a social movement industry dealing with a cause that is important to you. How do the different social movement organizations of this industry seek to engage you? Which techniques do you respond to? Why?

Do you think social media is an important tool in creating social change? Why, or why not? Defend your opinion.

Describe a social movement in the decline stage. What is its issue? Why has it reached this stage?

A&E Television Networks, LLC. 2014. "Civil Rights Movement." Retrieved December 17, 2014 ( http://www.history.com/topics/black-...ights-movement ).

Aberle, David. 1966. The Peyote Religion among the Navaho . Chicago: Aldine.

AP/The Huffington Post. 2014. "Obama: DOMA Unconstitutional, DOJ Should Stop Defending in Court." The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 17, 2014. (www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/0..._n_827134.html).

Area Chicago. 2011. “About Area Chicago.” Retrieved December 28, 2011 ( http://www.areachicago.org ).

Benford, Robert, and David Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26:611–639.

Blumer, Herbert. 1969. “Collective Behavior.” Pp. 67–121 in Principles of Sociology , edited by A.M. Lee. New York: Barnes and Noble.

Buechler, Steven. 2000. Social Movement in Advanced Capitalism: The Political Economy and Social Construction of Social Activism . New York: Oxford University Press.

CNN U.S. 2014. "Same-Sex Marriage in the United States." Retrieved December 17, 2014 ( http://www.cnn.com/interactive/us/ma...-sex-marriage/ ).

CBS Interactive Inc. 2014. "Anonymous' Most Memorable Hacks." Retrieved December 17, 2014 ( http://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/anon...rable-hacks/9/ ).

Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. 2011. "Letter from the Attorney General to Congress on Litigation Involving the Defense of Marriage Act." Retrieved December 17, 2014 ( http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/letter...e-marriage-act ).

Gladwell, Malcolm. 2010. “Small Change: Why the Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted.” The New Yorker , October 4. Retrieved December 23, 2011 ( http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2...urrentPage=all ).

Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Human Rights Campaign. 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2011 ( http://www.hrc.org ).

McAdam, Doug, and Ronnelle Paulsen. 1993. “Specifying the Relationship between Social Ties and Activism.” American Journal of Sociology 99:640–667.

McCarthy, John D., and Mayer N. Zald. 1977. “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 82:1212–1241.

National Organization for Marriage. 2014. “About NOM.” Retrieved January 28, 2012 ( http://www.nationformarriage.org ).

Sauter, Theresa, and Gavin Kendall. 2011. "Parrhesia and Democracy: Truthtelling, WikiLeaks and the Arab Spring." Social Alternatives 30, no.3: 10–14.

Schmitz, Paul. 2014. "How Change Happens: The Real Story of Mrs. Rosa Parks & the Montgomery Bus Boycott." Huffington Post. Retrieved December 17, 2014 (www.huffingtonpost.com/paul-s...b_6237544.html).

Slow Food. 2011. “Slow Food International: Good, Clean, and Fair Food.” Retrieved December 28, 2011 ( http://www.slowfood.com ).

Snow, David, E. Burke Rochford, Jr., Steven , and Robert Benford. 1986. “Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation.” American Sociological Review 51:464–481.

Snow, David A., and Robert D. Benford 1988. “Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization.” International Social Movement Research 1:197–217.

Technopedia. 2014. "Anonymous." Retrieved December 17, 2014 ( http://www.techopedia.com/definition...nymous-hacking ).

Texas Secede! 2009. “Texas Secession Facts.” Retrieved December 28, 2011 ( http://www.texassecede.com ).

Tilly, Charles. 1978. From Mobilization to Revolution . New York: Mcgraw-Hill College.

Wagenseil, Paul. 2011. "Anonymous 'hacktivists' attack Egyptian websites." NBC News. Retrieved December 17, 2014 ( http://www.nbcnews.com/id/41280813/n.../#.VJHmuivF-Sq ).

Ruhi Book 13 Unit 1

Sale price Price $3.00 Regular price

The study of this book is currently associated with a regional learning process. If you wish to tutor this course of the institute or are intending to participate in its study, please get in touch with your regional institute board.

North Island Regional Institute Board: [email protected]

South Island Regional Institute Board: [email protected]

Book 13 _ Engaging in Social Action _ Unit 1 _ Stirrings at the Grassroots

The first unit of this course examines instances of social action that are relatively simple and emerge naturally as the community-building process in a locality, cluster, or region advances. Within this context, participants gain insights into:

- how the institute process creates conditions, at the level of the individual and at the level of culture, that are conducive to engagement in social action;

- how social action emerges from natural stirrings at the grassroots;

- how some of the initiatives that arise remain simple and last for just a short period, while others become more complex as they are sustained over time;

- how acting within a shared conceptual framework allows the community to achieve coherence in its efforts;

- how the institution of the Local Spiritual Assembly promotes and supports social action and assists the friends to avoid certain pitfalls;

- and how the capacity to read social reality must consistently grow.

- Share Share on Facebook

- Tweet Tweet on Twitter

- Pin it Pin on Pinterest

Recently Viewed Items

Shopping Cart

Your cart is currently empty.

Enable cookies to use the shopping cart

You're saving $0.00

Tax included and shipping calculated at checkout

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Read the Grassroots Writing Research Journal issue 13.1 for Fall 2022 here. Read the Grassroots Writing Research Journal issue 13.1 for Fall 2022 here. top of page. ISU Writing Program ... analyze past works, and even keep a journal. Writing helps with everything from discussing other artists' work to starting the creative process of making a ...

All Grassroots Writing Research Journal past issues pages share the full issue and individual GWRJ pieces as separate files. You can find author, title, and abstracts on each GWRJ issue page. Find an article using specific ISU Writing Program terms and concepts, or focusing on a specific topic or subject matter.

The Grassroots Writing Research Journal is produced twice each year by the Writing Program at Illinois State University. The print issue of each journal is used as a primary text in two of ISU's undergraduate general education writing courses. Digital versions of previous issues are available (free) online. The title of the journal reflects ...

The ISU Writing Program supports the work of English 101 and English 145 courses, which are designed to serve different populations of students and the needs of different colleges and programs throughout the university. We adhere to the goals of the ISU general education curriculum and our own program Learning Outcomes, while promoting a focus ...

cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com

Introduction; 3.1 Identity and Expression; 3.2 Literacy Narrative Trailblazer: Tara Westover; 3.3 Glance at Genre: The Literacy Narrative; 3.4 Annotated Sample Reading: from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass; 3.5 Writing Process: Tracing the Beginnings of Literacy; 3.6 Editing Focus: Sentence Structure; 3.7 Evaluation: Self-Evaluating; 3.8 Spotlight on …

Grassroots Writing Research Journal - Issue 3.1 Unknown Binding . by Dept of English - Illinois State University (Author) Previous page. ISBN-10. 1609041631. ISBN-13. 978-1609041632. See all details. Next page. The Amazon Book Review Book recommendations, author interviews, editors' picks, and more.

Rifenburg, Michael J. "The Literate Practices of a Division II Men's Basketball Team." Grassroots Writing Research Journal (2016): 55-64. Rifenburg in his article studies how a Division II basketball team uses different literacy practices throughout the team along with how it affects the team and their performance.

This special issue on decolonizing is a convergence of critical scholarship, theoretical inquiry, and empirical research committed to questioning and redressing inequality in Africa and African Studies. It signals one of many steps 1 in a collective effort to examine how knowledge and power have been defined and denied through academic practice.

The Writing Center is located on the 1st floor of the library in the back left corner. You can make an appointment through Starfish, by calling 687-6981, or in person at RT 124. The Writing Center is open Monday - Thursday from 9:30am - 7:00pm and on Fridays from 9:30am - 4:00pm. The Writing Center is not an editing service.

address of the author/ s and the date. The report's title should be no longer than 12- 15 words and in a larger font size (e.g. 16-20 point) than the rest of the text on the cover page. Make ...

Grassroots Writing Research Journal 14.2. The Grassroots Writing Research Journal current issue is only available through Illinois State University bookstores, not through other vendors. You can get a copy from ISU's Redbird Spirit Shop at two locations: on North Street and in the Bone Student Center. If one bookstore is sold out, contact the ...

Abstract. GrassBase and GrassWorld are the largest structured descriptive datasets in plants, publishing descriptions of 11,290 species in the DELTA format. Twenty nine years of data compilation ...

Abstract This paper explores grassroots historiographical writing from Congo in the context of globalization. The authors are both sub-elite writers, producing text for First-World readers, and ...

Our mission is to improve educational access and learning for everyone. OpenStax is part of Rice University, which is a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit. Give today and help us reach more students. Help. OpenStax. This free textbook is an OpenStax resource written to increase student access to high-quality, peer-reviewed learning materials.

Special issue, Canadian Journal of Urban Research 15.2 Supplement (2006): i-viii. Google Scholar Certeau, Michel de. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Stephen Randall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988. Google Scholar Eliot, T. S. 'The Wasteland.' The Complete Plays and Poems1909-1950. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World ...

writing. Major Experiment #3: The Grassroots Writing Research Experience - In our final unit students will be tasked with formulating, planning, executing and documenting their own writing research experiments. Quizzes - 12 quizzes will be administered, of which your top ten scores will count towards 25% of your final grade.

In this paper, the authors propose a Four C model of creativity that expands this dichotomy. Specifically, the authors add the idea of "mini-c," creativity inherent in the learning process, and ...

The organization seeks to "create relationships and sustain community through art, research, education, and activism" (AREA Chicago 2011). ... At the time of this writing, more than thirty states and the District of Columbia allow marriage for same-sex couples. ... American Journal of Sociology 99:640-667. McCarthy, John D., and Mayer N ...

PDF | On Jan 15, 2021, Debra A. Castillo and others published Chapter 13 "I Heard You Help People" Grassroots Advocacy for Latina/os in Need | Find, read and cite all the research you need on ...

Book 13 _ Engaging in Social Action _ Unit 1 _ Stirrings at the Grassroots. The first unit of this course examines instances of social action that are relatively simple and emerge naturally as the community-building process in a locality, cluster, or region advances. Within this context, participants gain insights into:

AUTHORS. Chapter - 13 Writing Research Report Page. 503. Basic Guidelines for Research SMS Kabir. . The author's name is centered below the title along with the name of the university or ...