An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.48(6); 2019 Jun

A review of quality of life (QOL) assessments and indicators: Towards a “QOL-Climate” assessment framework

Ronald c. estoque.

1 Center for Social and Environmental Systems Research, National Institute for Environmental Studies, 16-2 Onogawa, Tsukuba City, Ibaraki 305-0053 Japan

Takuya Togawa

2 Fukushima Branch, National Institute for Environmental Studies, 10-2 Fukasaku, Miharu, Tamura District, Fukushima 963-7700 Japan

Makoto Ooba

Shogo nakamura, yasuaki hijioka, yasuko kameyama, associated data.

Quality of life (QOL), although a complex and amorphous concept, is a term that warrants attention, especially in discussions on issues that touch on the impacts of climate change and variability. Based on the principles of RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Synthesis, we present a systematic review aimed at gaining insights into the conceptualization and methodological construct of previous studies regarding QOL and QOL-related indexes. We find that (i) QOL assessments vary in terms of conceptual foundations, dimensions, indicators, and units of analysis, (ii) social indicators are consistently used across assessments, (iii) most assessments consider indicators that pertain to the livability of the environment, and (iv) QOL can be based on objective indicators and/or subjective well-being, and on a composite index or unaggregated dimensions and indicators. However, we also find that QOL assessments remain poorly connected with climate-related issues, an important research gap. Our proposed “QOL-Climate” assessment framework, designed to capture the social-ecological impacts of climate change and variability, can potentially help fill this gap.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13280-018-1090-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Quality of life (QOL) has been, and continues to be, an important research topic across various disciplines including medicine, health, psychology, economics, sociology, and environmental science. Accordingly, the literature regarding QOL is rich and continuously growing. However, owing to its multidimensionality and nebulousness, the meaning of QOL can vary from person to person across various contexts (Table 1 ). Numerous review articles concerning the various facets of QOL are available, including reviews that focus on its conceptual origin, foundation, and development (e.g., Massam 2002 ; Moons et al. 2006 ; Veenhoven 2007 ; Barcaccia et al. 2013 ). Reviews of various indexes related to QOL are also available (e.g., Hagerty et al. 2001 ; Pantisano et al. 2014 ). In addition, various frameworks and approaches for QOL assessment have been proposed, including those employing medicine and health-related questionnaire survey instruments (see Bakas et al. 2012 ; Theofilou 2013 ) as well as those transcending the scope of medicine and health-related fields (Veenhoven 2000 , 2007 ; Costanza et al. 2007 ; Fahy and Cinnéide 2008 ).

Table 1

Various definitions and descriptions of QOL

In recent years, various global initiatives built on the concept of sustainable development have been framed and propounded, including the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA 2005 ), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessments (IPCC 2014a ), the Future Earth initiative ( www.futureearth.org ), the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (UN 2000 ) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UN 2015 ), and the Paris Agreement on climate change (UNFCCC 2015 ). Embedded in these initiatives is the aim of promoting sustainability and improving QOL and human well-being by conserving the natural environment, promoting low carbon development, and adapting to global environmental change, especially climate change and variability.

By definition, climate change refers to “a change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer” (IPCC 2014a , p. 120). This includes changes in the patterns of essential climate variables such as precipitation and temperature (IPCC 2014a ). Climate variability refers to “variations in the mean state and other statistics (such as standard deviations, the occurrence of extremes, etc.) of the climate on all spatial and temporal scales beyond that of individual weather events” (IPCC 2014a , p. 121).

Climate change and variability affect QOL and human well-being in many ways, rendering it one of the most pressing and significant challenges of the present day. For instance, climate-related disasters and extreme events (such as droughts, floods, typhoons and landslides) can affect both the social and ecological components of a social-ecological system (Redman et al. 2004 ; Glaser et al. 2008 ; Ostrom 2009 ; Estoque and Murayama 2014a ), a coupled human–environment system (Turner et al. 2003 ), or a coupled human and natural system (Liu et al. 2007a , b ). Changes in precipitation and temperature patterns can also affect the supply and flow of various ecosystem services [provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural services (MEA 2005 ; TEEB 2010 )] (MEA 2005 ; IPCC 2014a ; Pecl et al. 2017 ; Runting et al. 2017 ). These ecosystem services are essential to human well-being because they are felt and experienced by people. Indeed, QOL and human well-being are important subjects in discourses on sustainability (Levett 1998 ; Fahy and Cinnéide 2008 ), ecosystem services (MEA 2005 ; Farley 2012 ), and climate impacts (Roberts 1976 ; IPCC 2001 ; Evans 2019 ).

Many scholars have demonstrated that a systematic review (Grant and Booth 2009 ; Haddaway et al. 2018 ) can help capture the state of knowledge and research trends, directions, and gaps in a particular discipline or subject (Englund et al. 2017 ; Jurgilevich et al. 2017 ; Runting et al. 2017 ). Owing to the rapid growth of information across disciplines and continuous improvements in scholars’ access to such information, the number and temporal occurrence of systematic reviews are expected to increase. In order to ensure that systematic reviews including reports are of high quality, attempts have been made to standardize the method used under the banner of RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Synthesis (ROSES) (Haddaway et al. 2017a , b , 2018 ; www.roses-reporting.com ). Central to ROSES is a set of detailed, state-of-the-art forms that authors (reviewers) are encouraged to use to ensure that their methods attain the highest possible standards. Although these forms have been specifically designed for environmental topics, they are applicable across disciplines ( www.roses-reporting.com ).

Systematic reviews of QOL assessments in medicine and health-related fields are available (Bakas et al. 2012 ; Ireson et al. 2018 ). In these fields, questionnaire survey instruments such as those by Wilson and Cleary, Ferrans et al., and the World Health Organization (WHO) (see Bakas et al. 2012 ; Theofilou 2013 ) play a key role in assessing QOL. However, there is a glaring absence of a systematic review of QOL assessments that are based on a more general context and that go beyond the use of medicine and health-related questionnaire survey instruments. Therefore, in this review of QOL assessments and indicators, we carried out the necessary to fill the information gap.

Our primary aim was to gain insights regarding the conceptualization and methodological construct of previous studies and assessments of QOL as well as of selected existing and emerging QOL-related indexes. The knowledge gained was used to develop a conceptual framework that may potentially connect QOL with issues of climate change and variability. We achieved this purpose by applying the principles of ROSES for a systematic review.

Materials and methods

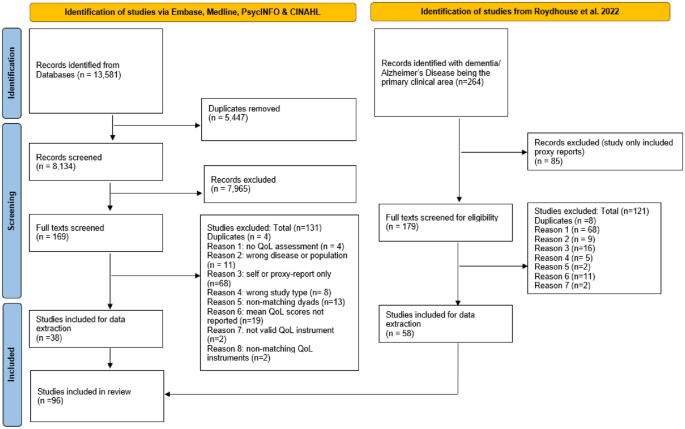

The three major steps under the ROSES principles for a systematic review are: (1) searching; (2) screening; and (3) appraisal and synthesis (Haddaway et al. 2017a , b , 2018 ). These steps are described below in the context of this current review (see also Fig. 1 ).

Flowchart of the review. This diagram is based on ROSES (Haddaway et al. 2017a , b , 2018 ; www.roses-reporting.com )

For this review, we used two sub-databases (SCI-EXPANDED and SSCI) within the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection. WoS is a large database of articles that include those in the social and environmental sciences (Landauer et al. 2015 ; Englund et al. 2017 ; Jurgilevich et al. 2017 ). In a recent scholarly work, it was demonstrated that WoS alone could be used as a source for a major systematic review (Runting et al. 2017 ). The potential limitations of this current review regarding database are discussed in “ Methodology-related discussion ” section.

In this review, we were especially interested in studies focusing on QOL assessment, evaluation, or measurement in the social-ecological context. Hence, we used terms that focus on the assessment, evaluation, and measurement of QOL (see Fig. 1 ). We performed our search on January 4, 2018, and included records published from 2000 to 2017. This period was chosen intentionally to capture recent trends in QOL research. The year 2000 essentially coincides with the Climate Change 2001—IPCC Third Assessment Report, a report that has been instrumental to the advancement of studies on climate impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability, all of which are important factors affecting QOL and human well-being (more details about this are provided in “ Linking QOL with climate change and variability issues ” section). In this review, we focused only on ‘articles’ published in the ‘English’ language.

Our search tracked 3251 articles (Fig. 1 ) that were dominated by medicine and health-related studies as indicated by the authors’ keywords and research areas as per the WoS classification (Fig. S1 ; Table S1 ). We further refined the search by focusing only on research areas that were deemed more relevant under the social-ecological system paradigm (Redman et al. 2004 ; Glaser et al. 2008 ; Ostrom 2009 ; Estoque and Murayama 2014a ): “social sciences other topics,” “sociology,” “science technology other topics,” “environmental sciences ecology,” “engineering,” “anthropology,” “social work,” “social issues,” “agriculture,” “public administration,” “geography,” “operations research management science,” “urban studies,” “physical geography,” and “remote sensing” (Table S1 ).

By narrowing the research areas, the searched articles decreased to 178 articles (Fig. 1 ). Having screened these articles based on title and abstract, 81 articles were identified and subjected to the next level of screening which focused on methods. The articles that were excluded were those that neither explicitly mentioned the method or approach used in QOL assessment, nor proceeded with QOL assessment, evaluation and measurement, as well as those that did not use any method other than medicine and health-related questionnaire survey instruments. On this basis, 19 articles were retained and subjected to a full-text review.

In addition, nine pre-screened existing and emerging QOL-related indexes were included in the review (Fig. 1 ). These included the Human Development Index (HDI) (UNDP 1990 ), Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) (Cobb et al. 1995 ), Happy Planet Index (HPI) (Marks 2006 ), Cities of Opportunity Quality of Life (COQOL) (PwC 2016 ), Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI) (UNDP 2010 ), Better Life Index (BLI) (OECD 2011 ), Human Sustainable Development Index (HSDI) (Togtokh 2011 ), Social Progress Index (SPI) (Porter et al. 2014 ), and Social-Ecological Status Index (SESI) (Estoque and Murayama 2014a , 2017 ). It was important to include these indexes because they are all related to QOL assessment to some extent, and thus provide complementary perspectives through their conceptualization and methodological construct of QOL-related indexes. There might have been some limitations in our selection of these indexes, and these are discussed in “ Methodology-related discussion ” section. Hereafter, these articles and indexes are collectively referred to as “reference(s).”

Appraisal and synthesis

In order to facilitate our analysis of the conceptualization and methodological construct of previous studies and assessments on QOL, as well as of some existing and emerging QOL-related indexes, we developed a questionnaire checklist (Table 2 ) for the systematic retrieval of relevant information from all of the references (Table S2 ). Prior to our analysis of the retrieved information, we examined the QOL publication trends and the network of keywords used in the searched articles (Fig. 1 ).

Table 2

Questionnaire checklist used to retrieve relevant information from the references reviewed

Publication trend and keywords network analysis

We used the two sets of searched articles (i.e., 3251 and 178) in our analysis of the temporal trends in QOL article publications, research areas, and occurrence and network of authors’ keywords. Our analysis of the occurrence and network of authors’ keywords was performed using the VOSviewer version 1.6.6, a software tool for analyzing bibliometric networks, creating maps based on network data, as well as visualizing and exploring these maps (van Eck and Waltman 2010 , 2017 ). The same software has been used in other previous bibliometric analyses (e.g., Gobster 2014 ; Rodrigues et al. 2014 ; Sweileh 2017 ).

Synthesis of the conceptualization and methodological construct for QOL assessment

Based on our pre-defined set of questions (Table 2 ), we summarized the following information in a table: year of publication or first release; purpose and scope; theoretical or conceptual foundation; dimensions and indicators; weighting and aggregation methods; value range and unit of final index; unit of analysis; and type of data used.

In our synthesis, we evaluated the references in relation to the triple bottom line. The triple bottom line has been, and continues to be, an important framework for sustainability assessment. It comprises three dimensions that are central to people’s quality of life and well-being: economic (profit), social (people), and environmental (planet) (Elkington 1994 , 1997 ). We classified the references based on the presence or absence of indicators (i.e., for an objective assessment) that fall under each of the three dimensions of the triple bottom line. To this end, the reference that included at least one indicator that falls within the scope of the dimension under consideration was marked by placing its number inside a circle. Otherwise, the reference was marked with a circle only, without its number. The references were also evaluated for whether subjective well-being (satisfaction, happiness, fulfillment, welfare, etc.) was considered in their respective assessments. Here, an objective assessment is defined as a type of evaluation or measurement that uses indicators that are based on statistics (e.g., census data) and other type of data (e.g., remote sensing and GIS data) independent of perceptions, while a subjective assessment is a type of evaluation or measurement that captures individual perceptions, preferences and evaluations (e.g., subjective well-being).

As part of our synthesis, we also evaluated and classified the references based on the four qualities of life plotted in four quadrants (Veenhoven 2000 , 2007 ). The four quadrants (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4) are the results of the intersections of two dichotomies, namely the outer and inner qualities of life, and the life chances and life results: (Q1) outer quality-life chances (livability of the environment); (Q2) inner qualities-life chances (life-ability of a person); (Q3) outer qualities-life results (utility of life); and (Q4) inner qualities-life results (enjoyment of life). According to Veenhoven ( 2000 , 2007 ), “outer quality” and “inner quality” are found in the environment and within the individual, respectively. Life chances refer to opportunities for a good life, while life results refer to outcomes. Livability of environment refers to the habitability of the environment, while the life-ability of a person refers to the capacity of individuals to cope with pressures or perturbations. Utility of life includes the external effects of life or the individual’s contributions to society and the environment, while enjoyment of life refers to the subjective appreciation of life, subjective well-being, life satisfaction, or happiness, including life expectancy (Veenhoven 2000 , 2007 ). Based on their respective indicators (i.e., either based on statistics, questionnaire surveys, or other types of data), we determined whether each of the references could have fulfilled each quadrant.

Synthesis of the linkage between QOL and climate change and variability issues

After the results of the bibliometric analysis and full-text review were summarized, we determined whether the issues of climate change and variability were considered in the references reviewed. Our finding (“ Methodological construct for QOL assessment ” and “ QOL and climate change and variability issues: their connections ” sections) revealed that QOL assessments were not [yet] well-connected with the issues of climate change and variability. To help advance this subfield of QOL research, we developed a conceptual framework that could potentially link QOL with issues relating to climate change and variability (“ Linking QOL with climate change and variability issues ” section).

Publication trends and keywords network

Of the total 3251 articles that resulted from our search, 38% were published during the first half of the analysis period (2000–2008), while 62% were published during the latter period (2009–2017) (Fig. 2 a). This means that the average number of articles published per year was higher during the 2009–2017 period (223) than during the 2000–2008 period (138). From 2000 to 2017, the average annual number of articles published was 181. Based on the 178 articles, i.e., those articles that were derived from the bibliometric search on the selected research areas (Fig. 1 , Table S1 ), a similar trend was observed; 31% and 69% of the articles were published during the earlier and latter periods, respectively (Fig. 2 b). The results also revealed some fluctuations in the annual publication of QOL research articles during the analysis period. Nevertheless, the results showed an overall significant increase in article publication of QOL assessments over the past 18 years for both sets of articles (Fig. 2 a, b).

Temporal trends in article publications regarding QOL (2000–2017). a Based on the 3521 articles resulting from all research areas; and b Based on the 178 articles resulting from the selected research areas. Table S1 lists all the research areas and those selected

Table S1 provides the complete list of research areas that the 3251 searched QOL articles fell into as per the WoS classification. With a few exceptions, most of the research areas are directly related to the medicine and health-related fields. Among these research areas, “health care sciences services,” “public environmental occupational health,” “oncology,” “surgery,” and “neurosciences neurology” topped the list. Those areas that are not directly related to the medicine and health-related fields include “sociology,” “environmental sciences ecology,” “engineering,” “agriculture,” “geography,” and “urban studies.”

Figure 3 presents the occurrence and network of authors’ keywords based on the 178 articles obtained after further screening, while the network map of the 3251 articles is presented in Fig. S1 . In both figures, the size of the circles indicates occurrences, while the thickness of the lines indicates link strength between keywords. The color and position of the circles indicate the clustering pattern. For the 178 articles (Fig. 3 ), the keyword “quality of life” had the highest occurrence (86) and total link strength (48). This was followed by the keyword “well-being” with an occurrence of 9 and a total link strength of 8. The keyword “well-being” also had the strongest connection with “quality of life,” followed by “assessment,” and “life satisfaction.”

Total occurrence and network of authors’ keywords based on the 178 articles (2000–2017). Fractional counting was used, which means that the weight of a link was fractionalized. For example, if a keyword co-occurs with five other keywords, each of the five keywords has a weight of 0.2 (1/5). For these 178 articles, a threshold of 2 was applied (i.e., the minimum number of occurrences for each keyword), resulting in a total of 50 keywords. The result for the 3251 articles is presented in Fig. S1

Conceptualization of QOL

The articles reviewed were structured on more specific concepts or variants of QOL, including quality of life as a function of objective socioeconomic and environmental variables, urban quality of life, transport quality of life, tourism-related community quality of life, and sustainable tourism development (Table S2 ). On the other hand, the QOL-related indexes reviewed were designed based on general concepts, including human development, sustainability or sustainable development, better life, social progress, and social-ecological status.

A wide range of QOL dimensions was identified from the references reviewed, and each of these dimensions included at least one indicator (Table S2 ). Selection of these dimensions and indicators was largely based on the references’ conceptualization of QOL as mentioned above, as well as on their respective purposes (see Table S2 ). For indicators, we found that 71% of the references considered indicators that could fulfill all the three dimensions of the the triple bottom line (economic, social and environmental) and 39% explicitly considered subjective well-being in their respective assessments (Fig. 4 ; see also Table S3 ). All of the references considered indicators that were related to the social dimension. However, some of the references did not consider indicators that directly fall under the economic (18%) and environmental (14%) dimensions (Fig. 4 ).

Classification of the references reviewed (19 articles [1–19] and 9 indexes [20–28]) based on their respective indicators plotted according to the triple bottom line (fulfillers of human needs). The figure also shows the articles and indexes that explicitly considered subjective well-being (satisfaction, happiness, fulfillment, welfare, etc.) in their respective frameworks and assessments. The numbers correspond to the numbers under the column heading “No.” in Tables 3 , S2 and S3 , and those in Fig. Fig.5 5

Figure 5 presents the categorization of the references reviewed in terms of their respective indicators in relation to the four qualities of life. Q1 (livability of the environment) included any indicator that is related to the quality of the social and physical environment, such as housing conditions, as well as the quantity and quality of urban facilities, water, air, and green spaces. Q2 (life-ability of a person) was associated with human and personal attributes, such as those related to health and education. Q3 (utility of life) included any indicator that is related to one’s (or the community’s) contribution to society and the environment, such as civic involvement, ecological footprint, sustainability-related programs, and efforts toward environmental conservation and art and culture preservation. Q4 (enjoyment of life) comprised indicators or dimensions such as subjective well-being, life satisfaction, happiness, and life expectancy. Of the total references reviewed, 39% were present in all four quadrants, which means that these references included at least one indicator under each of the four qualities of life. Among the four quadrants, Q3 had the highest percentage of references that lacked any indicator with 36%, followed by Q2 and Q4 with 25% each. In Q1, all but one of the references had at least one indicator.

Classification of the references reviewed (19 articles [1–19] and 9 indexes [20–28]), plotted across the four quadrants of QOL based on their respective indicators. The numbers correspond to the numbers in Fig. 4 and to the numbers under the column heading “No.” in Tables 3 , S2 and S3

Methodological construct for QOL assessment

Unit of analysis.

The results revealed that QOL assessments varied greatly in terms of context or unit of analysis. With the exception of González et al. ( 2011a ), the studies (articles) reviewed were conducted at the level of either census tract or neighborhood (C T /N), municipality or city (M/C), district or province (D/P), region or state (R/S), or country (C) (Table 3 ). In González et al. ( 2011a ), QOL assessment was conducted at three different administrative levels: M/C, D/P, and R/S. Of the nine indexes reviewed, eight were designed for country-level assessments, of which some could also be applied to sub-national level assessments (e.g., GPI and SESI; see also description in Table Table3). 3 ). Of all the indexes, GPI appeared to be the most flexible as it could also be applied at the M/C, D/P, and R/S levels, in addition to the country level. Of the studies (articles) reviewed, 47% assessed QOL in an urban area or city, two of which focused on transport systems (Table S2 ; see also description in Table Table3). 3 ). Eight of the nine indexes were designed for general assessment without targeting any particular sector, like urban areas or cities. COQOL is designed for QOL assessment in cities.

Table 3

Summary table highlighting some of the salient features of the references reviewed (articles [1–19] and indexes [20–28]). The table also indicates whether a particular reference used unequal weights (UW) during aggregation (dimension level) and whether it derived an overall composite index (OCI). The column called “No.,” which stands for number, corresponds to the column called “No.” in Tables S2 and S3 , and to the numbers in Figs. 4 and and5. 5 . C T /N—census tract/neighborhood; M/C—municipality or city; D/P—district or province; R/S—region or state; and C—country. Indexes: HDI (UNDP 1990 , 2010 , 2013 ); GPI (Cobb et al. 1995 ; Talberth and Weisdorf 2017 ); HPI (Marks 2006 ; NEF 2016 ); COQOL (PwC 2016 ); IHDI (UNDP 2010 , 2013 ); BLI (OECD 2011 , 2017 ); HSDI (Togtokh 2011 ); SPI (Porter et al. 2014 ; Stern et al. 2017 ); and SESI (Estoque and Murayama 2014a , 2017 )

a This reference presents a rule-based expert system for evaluating QOL. The intended unit of analysis was not explicitly mentioned. The testing of its prototype was performed in two universities. b HDI and IHDI are mainly used at the country level, though they are also used at the province or state level in some countries. c The BLI has no final index, but its web application allows users to assign weights to its dimensions. d The SESI can be applied across the units of analysis mentioned provided the required data are available. In this table, Reference Nos. (articles) 2–4, 8–9, 12, and 15–17 assessed QOL in an urban area or city, two of which focused on the transport system (4 and 8). Except for Reference Nos. 19 (article) and 23 (index), which respectively focused on tourism and urban/city, the rest of the references (articles and indexes) were designed for general assessments. More details can be found in Table S2

Methodological framework

The methodological framework employed by the references reviewed generally follows the principles of hierarchical aggregation (Fig. 6 ). This means that indicators are aggregated first, followed by the aggregation of the dimensions to produce a composite index. Of the references reviewed, 86% derived an overall composite index (OCI) (Table 3 ). The other 14% either did not aggregate at all (e.g., Carse 2011 ), or had their aggregation stopped at the dimension level (e.g., COQOL, PwC 2016 ). Of those that derived an OCI, 58% used unequal weights (UW) for their dimensions (Table 3 ), while the rest either explicitly used equal weights, simply derived the arithmetic or geometric mean, or had their own models for aggregation (Table S2 ). The BLI (OECD 2011 , 2017 ) does not have an OCI, but its web application allows users to assign weights to its dimensions.

A generalized and simplified flowchart for deriving an overall composite index based on hierarchical aggregation. Of the references reviewed, 86% derived an overall composite index, and 58% of these used unequal weights in the aggregation of their dimensions (see Tables Tables3 3 and S2 ). The dotted line between the dimension boxes and the overall composite index box indicates that not all of the references reviewed derived an overall composite index. Here, dimensions also refer to domains, components or their equivalent. In some cases, sub-indicators, called variables in the figure, were also used (e.g., Royuela et al. 2003 )

QOL and climate change and variability issues: their connections

The results revealed that climate-related keywords such as climate change, vulnerability, adaptive capacity, sensitivity, exposure, hazard, and risk were not [yet] popular among QOL scholars (Figs. 3 , S1). Nevertheless, we recognize that some of the references reviewed included some essential climate variables like temperature and rainfall (Royuela et al. 2003 ; Li and Weng 2007 ; Rao et al. 2012 ; Morais and Camanho 2011 ), as well as indicators like exposure and sensitivity to climate hazards (Estoque and Murayama 2014a , 2017 ), and thermal comfort and natural disaster exposure and preparedness (PwC 2016 ) (see also Table S2 ).

Research trend and potential gaps in QOL research

The bibliometric analysis revealed an overall significant increase in article publications concerning QOL assessment over the past 18 years, indicating that this field of study is receiving attention from the research and academic communities. In general, bibliometric analysis supports the evaluation of research trends in a particular field of study (Englund et al. 2017 ; Jurgilevich et al. 2017 ; Runting et al. 2017 ; Sweileh 2017 ). Besides providing guidance, it can encourage and challenge researchers to conduct further studies. In addition to the temporal data from article publications, the resulting research topics or keywords from this review (including their occurrences and networks) can be used to identify research trends and potential gaps in QOL research. We acknowledge that our approach for refining the research areas to be included in the second stage of the bibliometric analysis of QOL assessments that are more general in context was rather subjective. Nonetheless, the approach proved to be useful as it resulted in a more diverse set of keywords, favorable to the purpose of this review.

For instance, in our bibliometric analysis, the inclusion of keywords that go beyond the realms of medicine and health-related fields (e.g., “urban quality of life,” “environment,” “informal settlement,” “social indicators,” “municipalities,” “poverty,” and “remote sensing”) (Fig. 3 ) indicates that QOL assessments based on a more general perspective are becoming increasingly common. However, we observed that the aforementioned keywords still had low occurrences and weak connections with QOL (Fig. 3 ), indicating a need for further studies in their respective contexts. For example, although the keyword “environment” has been used by some scholars in their respective QOL assessments, its occurrence and connection with the keywords “quality of life” or “well-being” remained low and weak (Fig. 3 ). This could be due to the focus of the assessment, which might not be directly related to the environment, and/or the decision of the authors regarding their choice of keywords. Another plausible reason is that “environment” might have been perceived as having little importance in the context of the QOL assessment being performed, or not related to QOL at all. In fact, four of the references reviewed did not include any indicator of environment in their respective assessments or index development (UNDP 1990 , 2010 , 2013 ; Rinner 2007 ; Narayana 2009 ) (Fig. 4 ; Table S2 ). Furthermore, the observed low occurrence of the keyword “environment” and its weak connection with QOL could also signify a research gap, indicating that more studies are required to reveal the importance of natural capital to people’s QOL and well-being, as well as the human impact on the environment.

The results additionally revealed that some of the key environment-related concepts today were not popular among QOL authors in their choice of keywords, such as sustainable development (or sustainability), natural capital, and ecosystem services (Figs. 3 , S1). In fact, the relationship between QOL and sustainable development has continued to constitute an important topic among scholars (e.g., Boersema 1995 ; Mackay and Probert 1995 ; Levett 1998 ; Porio 2015 ; Gazzola and Querci 2017 ). We noted that within the references reviewed, some authors either mentioned or related their QOL assessments to the concept of sustainable development (Doi et al. 2008 ; Carse 2011 ; Atanasova and Karashtranova 2016 ; Yu et al. 2016 ). However, given that the sustainable development (or sustainability) concept was not captured in the analysis (Fig. 3 ), this indicates that more studies are needed to shed light on its connection with QOL and its importance in the actual assessment of human well-being in general. This is especially pertinent because sustainability is not a well-defined concept (Beckerman 1994 ; Wu 2013 ).

It is possible that one way of illustrating the connection between QOL and the concept of sustainable development is through the use of bridging concepts, such as the natural capital and ecosystem services concepts. Natural capital includes environments that generate and provide valuable ecosystem services to people (Costanza and Daly 1992 ; MEA 2005 ). The fresh air we breathe, the clean water we drink, the wood and medicinal plants we harvest, the coastal protective role that mangroves play, and the shade that trees provide (to name a few) are all considered ecosystem services. These services impact the quality of living and well-being of the populace because they are felt and experienced directly by people, and not “sustainable development” per se. However, in order to ensure the sustainability of these services, the concept of sustainable development must be observed and put into practice. The quantity and quality of these services today and in the future are contingent on human actions, i.e., what was done in the past and what is being done today. The United Nations recognizes that sustainable development is crucial to the QOL (UN 2015 ) and hence, the sustainability concept has been incorporated in most of the indexes reviewed (Fig. (Fig.4 4 and Table S2 ).

Conceptualization and methodological construct for QOL assessment

Among the studies (articles) reviewed, differences in the interpretation and operationalization of the QOL concept were observed. These studies have addressed and used the QOL concept in the context of their respective assessments. For instance, in their attempt to develop an integrated evaluation method for accessibility, quality of life, and social interaction, Doi et al. ( 2008 ) anchored their interpretation of the QOL concept on the livability of the environment, both physical and social. In their assessment of general QOL, González et al. ( 2011a , b ) interpreted and operationalized the QOL concept based on social welfare. Rao et al. ( 2012 ) viewed the QOL concept as a function of objective socioeconomic and environmental variables, while other scholars have considered more specific variants of QOL, such as urban quality of life (Li and Weng 2007 ; Rinner 2007 ; Morais and Camanho 2011 ; Brambilla et al. 2013 ), transport quality of life (Carse 2011 ), and tourism-related community quality of life (Yu et al. 2016 ) (see Table S2 ).

Conversely, the indexes reviewed are built on more general concepts and are designed for much broader types of QOL-related assessments. Among these conceptual foundations are sustainable development (or sustainability), human development, social progress, better life, global cities, resilience, and the social-ecological system paradigm. In general, these varied conceptual foundations are indicative of the multidimensionality and flexibility, but also the amorphous nature, of the QOL concept. In line with the references reviewed, we contend that there is a constant need to be explicit and specific, theoretically and conceptually, when attempting to perform a QOL assessment. In fact, in previous reviews, a theoretical/conceptual foundation has been deemed among the most important criteria for evaluating QOL indicators and assessments (Hagerty et al. 2001 ; Pantisano et al. 2014 ). Clarification at the outset of an assessment can help elucidate the overall context, and facilitate the identification and selection of the relevant dimensions and indicators to be included.

Thus, given that the references reviewed have their own conceptualization of QOL or QOL-related indexes according to their respective purposes, their respective sets of dimensions and indicators also varied (Table S2 ). Nevertheless, all of the indicators used can be related to the triple bottom line of sustainability (Fig. 4 ). While we found that HDI and IHDI did not include indicators related to the environment (UNDP 2013 ), two of the articles reviewed also did not include any indicator that could generally be classified under the environmental dimension (Rinner 2007 ; Narayana 2009 ) (Fig. 4 ). In terms of the social dimension, all the references considered at least one indicator, but in terms of the economic dimension, three of the articles (Narayana 2009 ; Brambilla et al. 2013 ; Kapuria 2014 ) and two of the indexes, viz. HPI (Marks 2006 ; NEF 2016 ) and SPI (Porter et al. 2014 ; Stern et al. 2017 ), did not consider any economic indicator. SPI is designed to measure social progress directly based on social and environmental outcomes, independent of economic development (Porter et al. 2014 ; Stern et al. 2017 ). On the other hand, HPI is designed to be a measure of sustainable well-being based on how efficiently residents in different countries use natural resources to achieve long lives and high levels of well-being (Marks 2006 ; NEF 2016 ).

The results also revealed that many of the references considered subjective well-being in their respective assessments (Fig. 4 ; Table S3 ). Overall, while the results (i.e., varying conceptual foundations, dimensions, indicators, and units of analysis) were somewhat expected due to the nature of the QOL concept, they were indicative of the diversity of dimensions and indicators that could be linked to the QOL concept. The extensive list of research areas identified in this review (Table S1 ) is another indication of the wide-ranging scope of the QOL concept. QOL assessments can also be performed across multiple spatial scales or administrative levels, although we recognize that most of the indexes reviewed are designed for country-level assessments (Table 3 ).

The four quadrants in Fig. 5 depict the four qualities of life according to Veenhoven ( 2000 , 2007 ). The results revealed that only 39% of the references reviewed considered at least one indicator under each QOL. Six of the nine indexes (67%) and five of the 19 articles (26%) reviewed considered at least one indicator under each QOL. This indicates that the indexes reviewed are, to some extent, relatively more holistic in their respective approaches to QOL-related assessments, i.e., as per the four qualities of life (Veenhoven 2000 , 2007 ). The four quadrants in Fig. 5 essentially capture the general dimensions of the triple bottom line and people’s subjective well-being (Fig. 4 ). In fact, by considering one’s contribution to society and the environment (Veenhoven 2000 , 2007 ), Q3 is also explicit in taking “leakage effects” into account, or the external environmental impact of development (Estoque and Murayama 2014b ).

In the methodological construct of QOL assessment and QOL-related index development, we need to consider important factors such as the purpose of the assessment or index, the multidimensionality of the QOL concept, the time and unit of analysis, and data availability in the selection of dimensions, indicators, and their corresponding variables (Rinner 2007 ; Grasso and Canova 2008 ; Narayana 2009 ; González et al. 2011a , b ; Morais and Camanho 2011 ; Li and Wang 2013 ; Kapuria 2014 ; Soleimani et al. 2014 ). Data availability is also critical to the testing and further development of various QOL-related indexes, e.g., BLI (OECD 2011 , 2017 ), COQOL (PwC 2016 ), GPI (Talberth and Weisdorf 2017 ), HPI (NEF 2016 ), SESI (Estoque and Murayama 2014a , 2017 ), and SPI (Porter et al. 2014 ; Stern et al. 2017 ). Data can be based on surveys (respondents’ perceptions) and/or census statistics and other sources such as geospatial (remote sensing and GIS) datasets.

In generating an overall composite index, weighting and aggregation methods also varied across studies and indexes (Table S2 ). While this indicates that a common approach to this purpose is unavailable, it is also indicative of the richness of the potential approaches that can be applied, explored, and further developed. In fact, it has been noted that the strengths and weaknesses of composite indicators largely depend on the stages of index development, including the weighting and aggregation methods used (OECD 2008 ). Some scholars prefer to use equal weights based on the literature (Royuela et al. 2003 ; Narayana 2009 ) or owing to the absence of empirical evidence or scientific basis (Estoque and Murayama 2014a , 2017 ). The subject of weighting is discussed in detail in other publications (Hagerty and Land 2007 ; OECD 2008 ; Hsieh 2014 ; Hsieh and Kenagy 2014 ).

Some scholars also prefer not to aggregate (Carse 2011 ; Lin 2013 ; PwC 2016 ; Yu et al. 2016 ). There are two sides to the argument regarding aggregation. On the one hand, composite indicators have the ability to reveal the results of an integrated analytical framework, capture the bigger picture, and provide summary statistics that can communicate system status and trends to a wide range of audiences (Baptista 2014 ; Estoque and Murayama 2017 ). They are also “suitable tools whenever the primary information of an object is too complex to be handled without aggregations” (Müller et al. 2000 , p. 13). Conversely, “composite indicators are also criticized for their tendencies to [lose information (Carse 2011 )], ignore or omit important dimensions that are difficult to measure, disguise weaknesses in some components, overlook the interconnectedness of indicators, and misrepresent the observed condition or process due to oversimplification…, [thus] have the potential to misguide policy and practice” (Estoque and Murayama 2017 , p. 613). Furthermore, there is always doubt whether the aggregation of QOL dimensions or indicators can actually reflect the quality of people’s lives (Schneider 1976 ; Lin 2013 ). Therefore, it is necessary for one to pay attention to these issues when using a composite index. Estoque and Murayama ( 2017 , p. 613) have argued that “specific indicators should be given more attention at the planning and policy levels, rather than focusing only on the summary statistic provided by the composite indicator.” Here, the hierarchical structure of a QOL assessment (Fig. 6 ) serves as a diagnostic tool to reveal which of the dimensions and indicators (or their variables, if available) are most responsible for high or low overall composite index values.

Linking QOL with climate change and variability issues

It is indisputable that the IPCC’s assessment reports (AR1–AR5) have helped raise people’s awareness (at least those in the environmental science field) of the social-ecological impacts of climate change and variability, as well as possible mitigation and adaptation measures. In fact, ‘quality of life’ has been explicitly mentioned in these reports (e.g., AR3, IPCC 2001 ). However, the results of this review provide very little evidence regarding the relationship between QOL and issues of climate change and variability as far as the references reviewed are concerned (Figs. 3 , S1 ; Table S2 ). Hence, overall, we believe that there remains a need to expand the scope of QOL research to include climate-related issues more explicitly.

We recognize that this attempt to explicitly connect QOL with climate-related issues is not new. For instance, in the mid-1970s, Hoch and Drake ( 1974 ) examined the relationship between wage rates and climatic variables (precipitation, temperature, and wind velocity) hypothesizing that higher wages compensated for lower quality of life. In their study, they found evidence in support of this hypothesis, the applications of which included estimating changes in real income given specified climate changes. Furthermore, Roberts ( 1976 ) highlighted the impacts of climate change and variability on the quality and character of life for millions of the Earth’s people. In particular, he emphasized impending world food shortages due to population growth, the demands of the affluent on available food supplies, and climate variability.

In a more recent case study, also in the context of QOL, Albouy et al. ( 2014 ) developed a hedonic framework to estimate US households’ preferences regarding local climates. They found that Americans would pay more on the margin to avoid excess heat than cold. In their review, Adger et al. ( 2013 ) highlighted the importance and role of cultural factors or services in climate change adaptation. They postulated that while place attachment contributes to QOL, this cultural value might be lost if people were forced to relocate as part of the strategy to adapt to climate change. Moreover, in a recent review of the behavioral impacts of global climate change, Evans ( 2019 , p. 6.1) posited that “droughts, floods, and severe storms diminish quality of life, elevate stress, produce psychological distress, and may elevate interpersonal and intergroup conflict… [and that] recreational opportunities are compromised by extreme weather, and children may suffer delayed cognitive development.”

In summary, these publications have considered wage rates (Hoch and Drake 1974 ), food (Roberts 1976 ), place attachment (Adger et al. 2013 ), the impacts of exposure to climate on comfort, activity, and health, including time use and mortality risk (Albouy et al. 2014 ), and behavioral impacts (Evans 2019 ) as indicators to bridge QOL and issues of climate change and variability. However, overall, QOL assessments in the context of climate-related issues remain limited. We believe that in order to help advance the “QOL-Climate” subfield of QOL research, a framework identifying and establishing the connection between QOL and climate-related issues is needed. Thus, drawing on the above insights regarding (i) the impacts of climate change and variability, (ii) QOL-Climate connection, and (iii) the results of this review on general QOL assessment, we present a general framework that could potentially link QOL and issues of climate change and variability.

On the right-hand side of Fig. 7 is a general structure for QOL assessment built upon the dimensions of the triple bottom line (economic, social, environmental) and subjective well-being (satisfaction, happiness, fulfillment, welfare, etc.) as summarized from the references reviewed. While the integrative definition of QOL suggests that it is the extent to which objective human needs are fulfilled in relation to personal or group perceptions of subjective well-being that defines QOL (Costanza et al. 2007 ; Table 1 ), this review finds that QOL can be based on objective indicators and/or subjective well-being (Fig. (Fig.4). 4 ). However, it should be noted that although this is a generalized structure (Fig. 7 —right side), some studies did not have a well-defined set of dimensions (Li and Weng 2007 ; Narayana 2009 ; Rao et al. 2012 ) (Table S2 ) and did not generate an overall composite index (Carse 2011 ; PwC 2016 ; Yu et al. 2016 ) (Table 3 ). As discussed above, some of the references also did not include subjective well-being in their respective assessments (Fig. 4 ).

The “QOL-Climate” assessment framework: a general framework for assessing quality of life, considering the social-ecological impacts of climate change and variability. Key references used in the development of this framework include IPCC’s AR5 on climate-related issues, Ostrom ( 2009 ) on the social-ecological system paradigm, Costanza et al. ( 2007 ) on the integrative definition of QOL, Elkington ( 1994 , 1997 ) on the triple bottom line, www.forumforthefuture.org on the five capitals, and www.pik-potsdam.de on impact chain analysis. Also included are references reviewed for some examples of indicators, and the syntheses in this review for the overall structure of the diagram

On the left-hand side of the diagram (Fig. 7 ) is a structure that illustrates the connection between climate change and variability and the components of a social-ecological system (i.e., essentially the ecosystems and sectors of society that produce the five capitals). Here, climate-related impacts across ecosystems and sectors of society are clarified through a climate impact chain analysis (in short: impact chain). An impact chain is “a general representation of how a given climate stimulus propagates through a system of interest via the direct and indirect impacts it entails” ( www.pik-potsdam.de ). For instance, a climate stimulus such as sea level rise can result in land loss, which then can trigger havoc to agricultural production and rural and urban areas, as well as necessitate migration ( www.pik-potsdam.de ). This analysis is important because it can help reveal the impacts of climate change and variability on the five capitals (human, social, natural, financial, and manufactured; www.forumforthefuture.org ) that provide goods and services to people.

In the center of the diagram are indicators (Fig. 7 ), their status being dependent on the condition of the capitals that produce them. The hypothesis is that the resulting QOL, through these indicators, depends on the status of the five capitals, which is also contingent on the extent of climate-related impacts at a given point in time. A feedback loop is drawn from the QOL and its dimensions to the social-ecological system components, indicating that the resulting level of QOL can be used as a driving force for policy intervention and adaptive planning (Fig. 7 ).

Such planning and policy interventions should be able to limit the exposure of the social-ecological system components and their sub-components to climate hazards and reduce their vulnerability to climate change and variability. The latter might be achieved by improving their adaptive capacities and reducing their sensitivities or susceptibilities to harm (IPCC 2014a , b ). In the context of adaptive planning and policy intervention, the hierarchical structure of a QOL assessment (Figs. 6 , ,7—right 7 —right side) can help diagnose which of the outcome indicators (or their variables, if available) need to be prioritized. This cyclic process of the framework is similar to those of other frameworks used in health, development, and environment-related monitoring and evaluation, such as the pressure-state-response (PSR) framework (OECD 1993 ) and the driving force-pressure-state-effect-action (DPSEA) framework (Kjellström and Corvalán 1995 ).

However, the lack of data regarding direct experience with climate change and variability (Evans 2019 ) can represent a major challenge in the operationalization of this proposed “QOL-Climate” assessment framework. We also recognize that all of these insights may not be easy to put into actual practice because every ecosystem and every sector of society may need its own set of interventions. Such interventions are among the hot issues today in the context of climate change adaptation, not only among scholars but also among planners and policy-makers. In a broader context, nature-based solutions or NbS is currently being considered as a potential approach to addressing global societal challenges, including those related to water security, food security, human health, disaster risk reduction, and climate change and variability (Cohen-Shacham et al. 2016 ). Among the ecosystem-based approaches within the NbS family are ecosystem restoration approaches (e.g., ecological restoration, ecological engineering, and forest landscape restoration), issue-specific ecosystem-related approaches (e.g., ecosystem-based approaches, ecosystem-based mitigation, climate adaptation services, and ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction), and green infrastructure and natural infrastructure approaches (for details, see Cohen-Shacham et al. 2016 ).

Methodology-related discussion

We recognize that the findings presented above are limited by the methods applied, and they should be interpreted with those caveats in mind. This is especially true of the search terms used, which focused on quality of life assessment, evaluation, or measurement, without the inclusion of other QOL-related terms like happiness, subjective well-being, and life satisfaction, or climate-related terms such as climate change, climate impacts, vulnerability, and adaptation. Nevertheless, we believe that the search terms used have provided equal opportunity for all research articles in the database to be selected, regardless of their focus (happiness, climate impacts, etc.) for as long as the terms (Fig. 1 ) were explicitly mentioned in their respective titles.

The selection of the scientific database(s) to be used is a very important consideration at the initial stage of any systematic review that adopts the ROSES principles and protocols. The selection of database(s) and the rationale behind their use often depend on their accessibility to users (reviewers), who are themselves reliant on their personal or their institutions’ subscriptions. Our case is no different. Had we included additional scientific databases, more research articles might have been captured. Nevertheless, as we mentioned in “ Searching ” section, it has been shown that WoS (the database we used) can be used on its own as a source for a major systematic review work (Runting et al. 2017 ). That being said, we support any future attempt to replicate this review involving a greater number of scientific databases.

Our selection of the nine QOL-related indexes was also rather subjective. Our intention was to include some relatively old indexes that are still in use (e.g., HDI, GPI), and others that are emerging (e.g., SPI, BLI), as well as peer-reviewed (e.g., SESI and GPI) indexes. As we mentioned in “ Introduction ” section, there exists a number of reviews that can be consulted for a more extensive list and a focused review of QOL-related indexes (e.g., Hagerty et al. 2001 ; Pantisano et al. 2014 ).

Summary and concluding remarks

Based on the principles of ROSES, we have presented a systematic review aimed at gaining insights regarding the conceptualization and methodological construct of previous studies and assessments of QOL and of selected existing and emerging QOL-related indexes. The knowledge gained was used to develop a framework that might link QOL with climate-related issues. Our review revealed that (i) QOL assessments varied in terms of conceptual foundations, dimensions, indicators, and units of analysis, (ii) compared with economic and environmental indicators, social indicators were consistently used across assessments; (iii) most assessments considered indicators that were related to the life-ability of a person, enjoyment of life, utility of life, and especially the livability of the environment, and (iv) QOL could be based on objective indicators and/or subjective well-being, and on a composite index or unaggregated dimensions and indicators. Our review also revealed that QOL assessments remain poorly connected with climate-related issues. We consider this as an important gap in QOL research, which needs to be filled by expanding the scope of such research. Our proposed “QOL-Climate” assessment framework, which is designed to capture the social-ecological impacts of climate change and variability, can potentially help in this regard.

Just like many key concepts such as sustainability, freedom, justice, and democracy (Daly 1995 ; Wu 2013 ) that have emerged in this contemporary geological epoch, the Anthropocene (the age of man) (Crutzen 2002 ), QOL represents a complex and dialectically vague concept (Massam 2002 ; Moons et al. 2006 ; Barcaccia et al. 2013 ). However, although all of these concepts possess elements of ambiguity, they convey fundamental principles that guide our actions and shape our visions for the future (see also Wu 2013 ). Consequently, we argue that, like the aforementioned concepts, QOL is considered a term of great importance to humankind. We are today faced with various pressing issues, including the social-ecological impacts of climate change and variability. Scholars from various fields are encouraged to work together so that this subfield of QOL research, which we have labeled “QOL-Climate,” will advance for the benefit of all.

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Environment, Japan, through Research Grants S2-1708 and S15. The conclusions and recommendations presented in this article are of the authors and do not, in any way, represent the views of the funder.

Biographies

is a Research Associate at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. His research interests include quality of life assessment, sustainability assessment, climate change vulnerability, impact and adaptation assessment, and the applications of geospatial technologies (remote sensing and geographic information systems) for social-ecological studies, including the monitoring and assessment of land-use/land-cover changes and ecosystem services.

is a Researcher at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. His research interests include quality of life indicators, sustainability indicators, applied mathematical optimization, and regional and urban environment design theory.

is a Section Head at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. His research interests include quality of life assessment, ecosystem services assessment, climate change vulnerability, impact and adaptation assessment, environmental ethics, and information science.

is a Senior Researcher at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. His research interests include integrated modeling, regional sciences, demography, and climate change mitigation and adaptation scenarios.

is a Researcher at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. His research interests include rural planning, social capital, sustainability, rural resource management, and community environmental management.

is a Section Head at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. His research interests include the analysis of environmental issues related to climate change, and the development of an integrated assessment model to assess climate change impacts and adaptation measures, as well as policy options for stabilizing global climate.

is a Deputy Director at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. Her research interests include international and institutional negotiations concerning climate change based on theories and methodologies of international relations, and policies towards a sustainable society, including its assessment.

Contributor Information

Ronald C. Estoque, Email: [email protected] , Email: ku.oc.oohay@k2snor .

Takuya Togawa, Email: [email protected] .

Makoto Ooba, Email: [email protected] .

Kei Gomi, Email: [email protected] .

Shogo Nakamura, Email: [email protected] .

Yasuaki Hijioka, Email: pj.og.sein@akoijih .

Yasuko Kameyama, Email: pj.og.sein@emaky .

- Adger WN, Barnett J, Brown K, Marshall N, O’brien K. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nature Climate Change. 2013; 3 :112–117. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1666. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Albouy D, Graf W, Kellogg R, Wolff H. Climate amenities, climate change, and american quality of life. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists. 2014; 3 :205–246. doi: 10.1086/684573. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Atanasova I, Karashtranova E. A novel approach for quality of life evaluation: Rule-based expert system. Social Indicators Research. 2016; 128 :709–722. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1052-0. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, Buelow JM, Otte JL, Hanna KM, Ellett ML, Hadler KA, et al. Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012; 10 (1):12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-134. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baptista SR. Design and Use of Composite Indices in Assessment of Climate Change Vulnerability and Resilience. CIESIN: The Earth Institute, Columbia University; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barcaccia B, Esposito G, Matarese M, Bertolaso M, Elvira M, De Marinis MG. Defining quality of life: A wild-goose chase? Europe’s Journal of Psychology. 2013; 9 :185–203. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v9i1.484. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beckerman W. Sustainable development: Is it a useful concept? Environmental Values. 1994; 3 :191–209. doi: 10.3197/096327194776679700. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhatti SS, Tripathi NK, Nagai M, Nitivattananon V. Spatial interrelationships of quality of life with land use/land cover, demography and urbanization. Social Indicators Research. 2017; 132 :1193–1216. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1336-z. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boersema JJ. Environmental quality and the quality of our way of life. Environmental Values. 1995; 4 :97–108. doi: 10.3197/096327195776679547. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brambilla M, Michelangeli A, Peluso E. Equity in the city: On measuring urban (ine)quality of life. Urban Studies. 2013; 50 :3205–3224. doi: 10.1177/0042098013484539. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carse A. Assessment of transport quality of life as an alternative transport appraisal technique. Journal of Transport Geography. 2011; 19 :1037–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.10.009. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cobb C, Halstead T, Rowe J. If the GDP is up, why is America down? Atlantic-Boston. 1995; 276 :59–79. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen-Shacham E, Walters G, Janzen C, Maginnis S, editors. Nature-based Solutions to address global societal challenges. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Costanza R, Daly HE. Natural capital and sustainable development. Conservation Biology. 1992; 6 :37–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1992.610037.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Costanza R, Fisher B, Ali S, Beer C, Bond L, Boumans R, Danigelis NL, Dickinson J, et al. Quality of life: An approach integrating opportunities, human needs, and subjective well-being. Ecological Economics. 2007; 61 :267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.02.023. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crutzen PJ. Geology of mankind. Nature. 2002; 415 :23. doi: 10.1038/415023a. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cutter SL. Rating Places: A Geographer’s View on Quality of Life. Washington DC: Association of American Geographers; 1985. [ Google Scholar ]

- Daly HE. On wilfred beckerman’s critique of sustainable development. Environmental Values. 1995; 4 :49–55. doi: 10.3197/096327195776679583. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dasgupta P, Weale M. On measuring the quality of life. World Development. 1992; 20 :119–131. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(92)90141-H. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Doi K, Kii M, Nakanishi H. An integrated evaluation method of accessibility, quality of life, and social interaction. Environment and Planning B. 2008; 35 :1098–1116. doi: 10.1068/b3315t. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elkington J. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California Management Review. 1994; 36 :90–100. doi: 10.2307/41165746. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elkington J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of the 21st Century Business. Oxford: Capstone; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Englund O, Berndes G, Cederberg C. How to analyse ecosystem services in landscapes—A systematic review. Ecological Indicators. 2017; 73 :492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.10.009. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Estoque RC, Murayama Y. Social-ecological status index: A preliminary study of its structural composition and application. Ecological Indicators. 2014; 43 :183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.02.031. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Estoque RC, Murayama Y. Measuring sustainability based upon various perspectives: A case study of a hill station in Southeast Asia. Ambio. 2014; 43 :943–956. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0498-7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Estoque RC, Murayama Y. A worldwide country-based assessment of social-ecological status (c. 2010) using the social-ecological status index. Ecological Indicators. 2017; 72 :605–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.08.047. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Evans GW. Projected behavioral impacts of global climate change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2019; 70 :6.1–6.26. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103023. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fahy F, Cinnéide MÓ. Developing and testing an operational framework for assessing quality of life. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 2008; 28 :366–379. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2007.10.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Farley J. Ecosystem services: The economics debate. Ecosystem Services. 2012; 1 :40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2012.07.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Felce D, Perry J. Quality of life: Its definition and measurement. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1995; 16 :51–74. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(94)00028-8. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gazzola P, Querci E. The connection between the quality of life and sustainable ecological development. European Scientific Journal. 2017; 13 :361–375. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glaser M, Krause G, Ratter B, Welp M. Human/nature interaction in the anthropocene. Gaia. 2008; 17 :77–80. doi: 10.14512/gaia.17.1.18. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gobster PH. (Text) Mining the LANDscape: Themes and trends over 40 years of landscape and urban planning. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2014; 126 :21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.02.025. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- González E, Cárcaba A, Ventura J. The importance of the geographic level of analysis in the assessment of the quality of life: The case of Spain. Social Indicators Research. 2011; 102 :209–228. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9674-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- González E, Cárcaba A, Ventura J, Garcia J. Measuring quality of life in Spanish municipalities. Local Government Studies. 2011; 37 :171–197. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2011.554826. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2009; 26 :91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grasso M, Canova L. An assessment of the quality of life in the European union based on the social indicators approach. Social Indicators Research. 2008; 87 :1–25. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9158-7. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hacker ED. Technology and quality of life outcomes. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2010; 26 :47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.11.007. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haddaway, N., B. Macura, P. Whaley, A. Pullin. 2017a. ROSES for Systematic Review Reports. Version 1.0. 10.6084/m9.figshare.5897272.

- Haddaway, N., B. Macura, P. Whaley, A. Pullin. 2017b. ROSES flow diagram for systematic reviews. Version 1.0. 10.6084/m9.figshare.5897389.

- Haddaway NR, Macura B, Whaley P, Pullin AS. ROSES RepOrting standards for systematic evidence syntheses: Pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environmental Evidence. 2018; 7 :1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13750-017-0113-z. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagerty MR, Cummins R, Ferriss AL, Land K, Michalos AC, Peterson M, Sharpe A, Sirgy J, et al. Quality of life indexes for National Policy: Review and agenda for research. Social Indicators Research. 2001; 55 :1–96. doi: 10.1023/A:1010811312332. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagerty MR, Land KC. Constructing summary indices of quality of life: A model for the effect of heterogenous importance weights. Sociol Methods and Research. 2007; 35 :455–496. doi: 10.1177/0049124106292354. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoch I, Drake J. Wages, climate, and the quality of life. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 1974; 1 :268–295. doi: 10.1016/S0095-0696(74)80002-1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hsieh CM. Throwing the baby out with the bathwater: Evaluation of domain importance weighting in quality of life measurements. Social Indicators Research. 2014; 119 :483–493. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0500-y. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hsieh CM, Kenagy GP. Measuring quality of life: A case for re-examining the assessment of domain importance weighting. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2014; 9 :63–77. doi: 10.1007/s11482-013-9215-0. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- IPCC . Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- IPCC. 2014a. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, ed. R.K. Pachauri, and L.A. Meyer]. 151 pp. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

- IPCC. 2014b. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change C.B. Field , ed. V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, 1–32 pp. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press.

- Ireson J, Jones G, Winter MC, Radley SC, Hancock BW, Tidy JA. Systematic review of health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcome measures in gestational trophoblastic disease: A parallel synthesis approach. The Lancet Oncology. 2018; 19 :e56–e64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30686-1. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jurgilevich A, Räsänen A, Groundstroem F, Juhola S. A systematic review of dynamics in climate risk and vulnerability assessments. Environmental Research Letters. 2017; 12 :13002. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa5508. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kapuria P. Quality of life in the city of Delhi: An assessment based on access to basic services. Social Indicators Research. 2014; 117 :459–487. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0355-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kjellström T, Corvalán C. Framework for the development of environmental health indicators. World Health Statistics Quarterly. 1995; 48 :144–154. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Landauer M, Juhola S, Söderholm M. Inter-relationships between adaptation and mitigation: A systematic literature review. Climatic Change. 2015; 131 :505–517. doi: 10.1007/s10584-015-1395-1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levett R. Sustainability indicators - integrating quality of life and environmental protection. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1998; 161 :291–302. doi: 10.1111/1467-985X.00109. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li G, Weng Q. Measuring the quality of life in city of Indianapolis by integration of remote sensing and census data. International Journal of Remote Sensing. 2007; 28 :249–267. doi: 10.1080/01431160600735624. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li Z, Wang P. Comprehensive evaluation of the objective quality of life of Chinese residents: 2006 to 2009. Social Indicators Research. 2013; 113 :1075–1090. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0128-3. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin K. A methodological exploration of social quality research: A comparative evaluation of the quality of life and social quality approaches. International Sociology. 2013; 28 :316–334. doi: 10.1177/0268580913484776. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu BC. Variations in social quality of life indicators in medium metropolitan areas. American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 1978; 37 :241–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1536-7150.1978.tb01227.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu J, Dietz T, Carpenter SR, Folke C, Alberti M, Redman CL, Schneider SH, Ostrom E, et al. Coupled human and natural systems. Ambio. 2007; 36 :639–649. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[639:CHANS]2.0.CO;2. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu J, Dietz T, Carpenter SR, Alberti M, Folke C, Moran E, Pell AN, Deadman P, et al. Complexity of coupled human and natural systems. Science. 2007; 317 :1513–1516. doi: 10.1126/science.1144004. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mackay RM, Probert SD. National policies for achieving energy thrift, environmental protection, improved quality of life, and sustainability. Applied Energy. 1995; 51 :293–367. doi: 10.1016/0306-2619(95)00010-P. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marks, N. 2006. The (un)Happy Planet Index: An Index of Human Well-Being and Environmental Impact . New Economics Foundation (NEF).

- Massam BH. Quality of life: Public planning and private living. Progress in Planning. 2002; 58 :141–227. doi: 10.1016/S0305-9006(02)00023-5. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MEA . Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moons P, Budts W, De Geest S. Critique on the conceptualisation of quality of life: A review and evaluation of different conceptual approaches. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006; 43 :891–901. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.03.015. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morais P, Camanho AS. Evaluation of performance of European cities with the aim to promote quality of life improvements. Omega. 2011; 39 :398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.omega.2010.09.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morais P, Miguéis VL, Camanho AS. Quality of life experienced by human capital: An assessment of European cities. Social Indicators Research. 2013; 110 :187–206. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9923-5. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Müller F, Hoffmann-Kroll R, Wiggering H. Indicating ecosystem integrity—theoretical concepts and environmental requirements. Ecological Modelling. 2000; 130 :13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3800(00)00210-6. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Narayana MR. Education, human development and quality of life: Measurement issues and implications for India. Social Indicators Research. 2009; 90 :279–293. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9258-z. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- NEF. 2016. Happy Planet Index 2016: Methods Paper . New Economic Foundation.

- OECD. 1993. OECD Core Set of Indicators for Environmental Performance Reviews: A Synthesis Report by the Group on the State of the Enviroment. OECD Environmental Monograph No. 83. OECD, Paris, France.

- OECD . How’s Life? Measuring Well-Being. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- OECD. 2017. Better Life Index—Edition 2017 . OECD. https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=BLI .

- OECD . Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ostrom E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science. 2009; 325 :419–422. doi: 10.1126/science.1172133. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pacione M. Urban environmental quality and human wellbeing—a social geographical perspective. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2003; 65 :19–30. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00234-7. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pantisano, F., M. Craglia, C. Rosales-Sanchez. 2014. New Indicators of Quality of Life: A Review of the Literature, Projects, and Applications. Citizen Science Observatory of New Indicators of Urban Sustainability (Project 1076). European Commisison.

- Pecl GT, Araújo MB, Bell JD, Blanchard J, Bonebrake TC, Chen IC, Clark TD, Colwell RK, et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science. 2017; 355 :eaai9214. doi: 10.1126/science.aai9214. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Porio E. Sustainable development goals and quality of life targets: Insights from Metro Manila. Current Sociology. 2015; 63 :244–260. doi: 10.1177/0011392114556586. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Porter ME, Stern S, Green M. Social Progress Index 2014. USA: Social Progress Imperative; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- PwC . Cities of Opportunity 7. London, UK: PwC; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rao KRM, Kant Y, Gahlaut N, Roy PS. Assessment of quality of life in Uttarakhand, India using geospatial techniques. Geocarto International. 2012; 27 :315–328. doi: 10.1080/10106049.2011.627470. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Redman CL, Grove JM, Kuby LH. Integrating social science into the long-term ecological research (LTER) network: social dimensions of ecological change and ecological dimensions of social change. Ecosystems. 2004; 7 :161–171. doi: 10.1007/s10021-003-0215-z. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]