Poverty in Urban Areas Report

Introduction, drawbacks to urban poverty alleviation, solutions for urban poverty, works cited.

In developing countries, the alarming levels of urban poverty call for prompt action. Continuous development of urban areas and growth of urban population in these countries has led to a myriad of problems that has made urban poverty a cyclic phenomenon.

Today, urban population is facing poverty-related problems like lack of sanitation and clean water, poor drainage, inadequate management of waste, etc (Stephen, 2008, p. 1). Living in this kind of an environment which is also characterized with high unemployment rates and overpopulation, the poor are forced to engage in activities that sink them deeper in poverty and guarantee the poverty of their children.

This problem is magnified by the fact that government agencies have been unable to develop a sustainable solution through planning. This paper is a report addressing the problem of urban poverty and suggesting possible solutions to the problem for presentation to an aid agency (“Analyzing urban poverty”, 2006, pp. 1 – 12).

The main reason for escalation of the problem of poverty is urban areas is because the intricate problems of urban poverty are considered too small to attract big policies. However, their cumulative effect on urban life is tremendous. First of all, poverty in urban areas implies poor quality of urban neighbourhoods.

This is due to the fact that most of these areas have council housing that fails to meet minimal decency standards (Stephen, 2008, p. 1). Other urban areas are characterized with a high number of squatter settlements that have equally poor living conditions.

These settlements are also characterized with dense population, land scarcity and topological limitations that make it difficult for them to gain access to urban services like electricity, water and sometimes transport infrastructure. They, therefore act as a catalyst for aggressive and disruptive behaviour. Residents of these areas, therefore, engage in graffiti, rubbish dumping, vandalism and minor crime.

These are made hard to detect by the environment these people live in. On the contrary, well-kept environments are self regulatory with reference to unacceptable societal behaviour. Thus, these environments draw people to leisure spaces that create common purpose and security. As stated earlier, poverty in urban areas prompt for actions by the poor that make the poverty cyclical. For instance, in most urban areas, the poor are forced to use alternative energy like charcoal that lead to environmental degradation.

This leads to weather and climate problems that affect economies and thus plunges the poor into more poverty. They are also forced to indulge their children in child labour and therefore, the children miss education. This makes their children lead the poor lives their parents led (Perlman, Hopkins & Jonsson, 1998, pp. 1 – 13).

Good development programs

The efforts of government agencies in combating urban poverty have not achieved remarkable success in poverty stricken urban areas due to poor planning. Aid agencies should, therefore, intervene and conceive holistic improvement programs that take the key issues related to urban poverty into consideration.

These issues include housing, education, environmental degradation, crime, unemployment etc. Aid agencies and philanthropists need to gather dweller information such as religious icons, small meeting places, posted bills etc. This information may seem insignificant at a glance but it enables planners to avoid future problems that may derail poverty alleviation efforts (Ravallion, 2007, p. 1).

Combating environmental degradation

Urban poverty and environmental degradations are highly inter-related and they are regarded to stem from poor development plans. The interrelation is evidenced by the fact that environmental degradation leads to more poverty and the fact that the poor are regarded as the chief agents of environmental degradation.

Poverty alleviation plans should therefore incorporate environmental conservation plans in order to prevent negative effects of environmental degradation from affecting poverty alleviation efforts (Douglass, 1998, p. 1).

Dealing with Overpopulation

Overpopulation is one of the major contributors of urban poverty. Low-class urban settlements are characterized with congestion that has adverse effects on the economic welfare of the inhabitants of these areas. Poverty alleviation plans must therefore address the issue of overpopulations.

Strategies and plans should be devised to ease out congestion in these areas and reduce the negative effects of overpopulation such as pollution, crime, unemployment, environmental degradation etc. Therefore, aid agencies should develop proper plans for urban settlement management in their efforts to reduce urban poverty (Srinivas, 2010, p. 1).

Community involvement

To successfully implement the suggested solutions, there is need to involve the community in the development efforts. The community holds the potential to contribute to development plans and therefore, aid agencies should attract community initiative with innovative planning and management.

The community should also be consulted before implementation of development plans to make sure that the plans are in agreement with acceptable community standards. The communities are also characterized with valuable innovations that are instrumental to development plans and therefore their involvement will be very valuable (Douglass, 1998, p. 1).

Proper resource allocation

There is also the need to devolve significant budgetary allocation to bigger areas in order to impact the cities substantially. Thus, such strategies which increase the impact of urban poverty alleviation should be appropriately set out. There is also the need to harness resources that are prerequisite to development (Masika, 2010, p. 11). Examples of these resources include creativity and innovation, and energy.

Circular cities are also known to be better than linear cities in terms of utilization and recapturing of resources (“Urban poverty”, 2008, p. 1). Therefore, aid agencies should advocate for construction of circular cities if their poverty alleviation plans involve reconstruction.

Poverty has been a major challenge in the urban areas of developing countries, especially those that have problems of overpopulation. The effects of urban poverty have extensively affected urban life in these countries by acting as a catalyst for vices in the societies.

Government agencies in these countries have failed miserably in their efforts to combat this problem. It is, therefore, essential for aid agencies to implement the suggested strategic and precautionary measures before investing in the alleviation of the poverty in these areas.

This will ensure that their efforts are productive. However, the implementation of these strategies and plans may also be faced with problems. One of the problems facing implementation of strategies is the fact that the residents in these areas normally have benchmarks for infrastructure and other facilities from the neighbouring and well-off areas.

This problem is conspicuous in government development projects in which the residents of these areas expect equal treatment and thus expect construction of wide roads, construction of extravagant buildings etc (“Analyzing urban poverty”, 2006, p. 1). The aid agencies, therefore, need to address this problem adequately.

The inhabitants of these areas may also fear relocation by the planning agencies. With reference to the aforementioned challenges, aid agencies and philanthropists should devise proper plans to ensure that their alleviation efforts are appreciated and backed by the poor population (Perlman, Hopkins & Jonsson, 1998, pp. 13 – 17).

Analyzing Urban Poverty. (2006). A Sustainable Approach to Problems in Urban Squatter Developments . Web.

Douglass, M. (1998). Britain’s Cities of Yesterday and Tomorrow . Web.

Masika, R. (2010). Urbanization and Urban Poverty: A Gender Analysis . Web.

Perlman. J, Hopkins, E & Jonsson, A. (1998). Urban Solutions at the Poverty/Environment Intersection. Web.

Ravallion, M. (2007). Urban Poverty . Web.

Srinivas, H. (2010). Urban Development and Urban Poverty . Web.

Stephen, D. (2008). Breaking the Cycle of Urban Poverty . Web.

Practical Action. (2008). Urban poverty . Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 8). Poverty in Urban Areas. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-in-urban-areas/

"Poverty in Urban Areas." IvyPanda , 8 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-in-urban-areas/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Poverty in Urban Areas'. 8 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Poverty in Urban Areas." January 8, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-in-urban-areas/.

1. IvyPanda . "Poverty in Urban Areas." January 8, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-in-urban-areas/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Poverty in Urban Areas." January 8, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-in-urban-areas/.

- Poverty Alleviation and Sustainable Development

- Private Sector’s Role in Poverty Alleviation in Asia

- Microcredit: A Tool for Poverty Alleviation

- Corporate Social Responsibility & Poverty Alleviation

- Pain Alleviation in Suffering Patients

- Great Barrier Reef: Flood Alleviation Solutions

- Music Performance Anxiety Alleviation

- U.S. Mortgage Crisis Significance and Alleviation

- Overpopulation Benefits

- The Problem of Overpopulation

- Deputy Sheriffs Collective Bargaining Issue

- Health Care – Operation & Management in Canada, England and USA

- Democracy in the Middle East

- Healthcare as a Basic Right of Americans

- Public Policy: Social, Economic, and Foreign

Has extreme poverty been urbanized?

Shohei nakamura, mark roberts, benjamin stewart.

As we highlighted last week in a companion blog , countries vary considerably in how they define urban areas, which makes comparison of urbanization patterns across countries difficult.

However, that’s not the only problem— the lack of standard urban definitions also throws up challenges for poverty measurement and analysis, such as the disaggregation of poverty statistics between urban and rural areas in a comparable manner. This becomes a critical hindrance, both to policy research (for example, to examine how urbanization facilitates poverty reduction) and design (for example, to determine how to allocate resources spatially).

To overcome this challenge, a recent policy research working paper integrates two recently developed approaches to the consistent delineation of urban areas—the Degree of Urbanization (DOU) and the Dartboard (DB) method —into the World Bank’s framework for international poverty comparisons. In this blog, we highlight some key findings from this working paper, based on a sample of 16 countries from Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

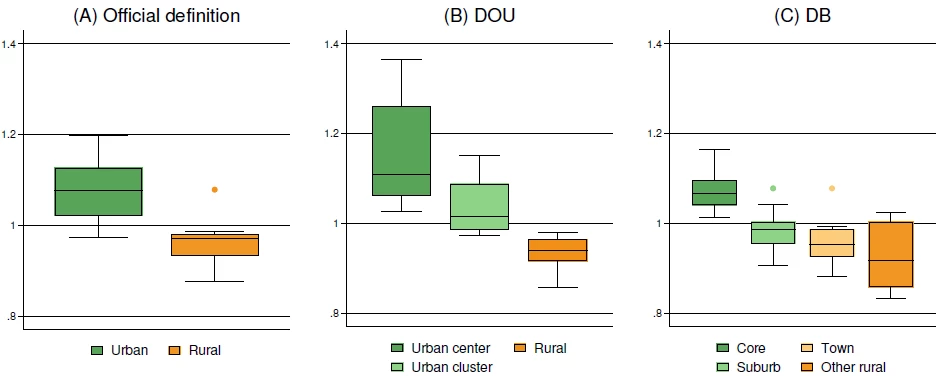

We find that the cost of living is higher in high-density urban areas.

It is not evident whether monetary poverty is always lower in more densely populated urban areas than in rural areas, even though the cost of urban living tends to be higher. Using household budget surveys, we measured the subnational-level cost of living for 16 SSA countries.

Using the DOU and DB approaches to define urban areas, we noticed a distinct gradient with the cost of living being higher in more densely populated urban areas than in less densely populated urban areas, which, in turn, have a higher cost-of-living than rural areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cost of living index across 16 SSA countries, circa 2015.

Source: Nakamura et al. (2023). Note: The boxplots show the range of 16 spatial deflator values for each geographic category. The spatial deflators indicate cost of living (normalized to 1 at the national level in each country) and are used to deflate household consumption expenditures for poverty measurement. Urban areas are defined by the official definitions (A), the Degree of Urbanization (B), and the Dartboard method (C).

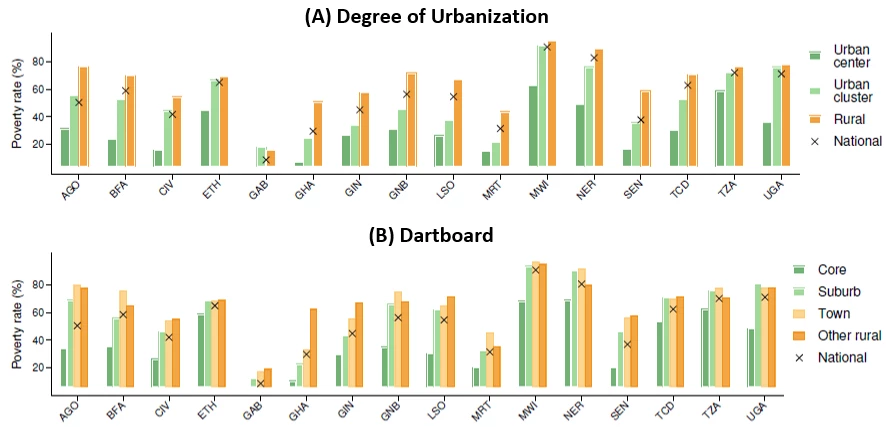

Poverty incidence is lower in higher-density urban areas..

However, even after purchasing power is discounted for the higher cost of living, urban poverty incidence is found to be lower than rural poverty incidence in the 16 Sub-Saharan African countries (Figure 2). Poverty incidence is particularly low in higher-density urban areas (that is, urban centers in the case of the DOU and urban cores in the case of the DB approach).

However, it is important to not automatically conclude from this that cities support people to escape poverty, as it is also possible that poverty rates in urban areas are lower because of selective migration of relatively wealthy people from rural areas.

Figure 2. Poverty incidence across 16 SSA countries, circa 2015.

Source: Nakamura et al. (2023). Note: Poverty is measured with the extreme poverty line ($2.15 in 2017 PPP terms). Urban areas are defined by the Degree of Urbanization (A) and the Dartboard method (B).

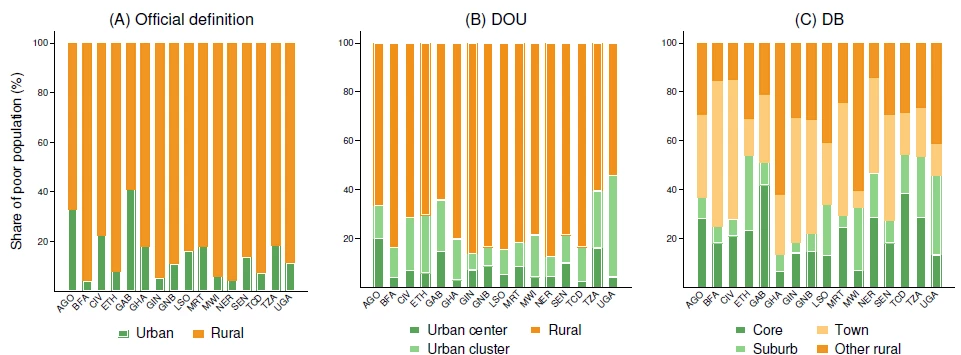

More poor people live in urban areas than previously thought..

Despite the low poverty incidence, urban areas account for a larger share of the poor population than previously thought. When the official urban definitions are used, 80 percent of poor populations live in rural areas in most countries. When we apply the DOU classification, most countries' urban share of poor populations––represented by the green bars in the figures ––increases while the median urban share of the poor in the 16 SSA countries increases from 13 to 21 percent. Urban shares reach nearly 40 percent in Angola and Gabon and in a few other countries, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Uganda. Urban shares of the poor population are even higher when the DB approach is used to define urban areas––high-density urban cores accommodate a large share of poor populations in many countries.

Figure 3. The geographic composition of the poor population across 16 SSA countries, circa 2015.

Source: Nakamura et al. (2023). Note: Poverty is measured with the extreme poverty line ($2.15 in 2017 PPP terms). Urban areas are defined by the official definitions (A), the Degree of Urbanization (B), and the Dartboard method (C).

How many of the world’s poor live in urban areas.

As the above results demonstrate, moving from the use of official definitions of urban areas, which vary widely across countries, to definitions that are consistent across countries and, therefore, allow for apples-to-apples comparisons, can have profound implications for our understanding of the distribution of poverty across urban and rural areas.

The next step is to expand our analysis to additional countries and gradually move toward a full global analysis of the distribution of poverty across urban and rural areas. This will allow us to answer the fundamental, but currently unanswered, question: how many of the world’s poor live in urban areas?

Economist in the Poverty and Equity Global Practice

Lead Urban Economist, World Bank

Geographer, Geospatial Operational Support Team, World Bank

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Tackling the legacy of persistent urban inequality and concentrated poverty

Subscribe to the economic studies bulletin, stuart m. butler and stuart m. butler senior fellow - economic studies @stuartmbutler jonathan grabinsky jonathan grabinsky consultant - world bank.

November 16, 2020

The death of George Floyd and other Black Americans and the uneven impact of COVID-19 have highlighted deep-rooted concerns about racial and urban inequality and segregation in America and the consequences of inequality for families living in persistent poverty.

Over the past several years, the research literature pointing to the relationship between racial segregation, enduring concentrated poverty, and long-term socioeconomic inequalities in the United States has been rapidly growing. Work by such scholars as Patrick Sharkey , Robert Sampson , and others, and novel experimental evidence produced by Raj Chetty has greatly increased our understanding of the detrimental – and multigenerational – consequences of being born and raised in an under-resourced neighborhood.

Long-Term Damage

Over the past forty years, the country has experienced sharp increases in urban poverty. The number of metropolitan neighborhoods in which 30 percent or more of residents live in poverty doubled between 1980 and 2010 . Moreover, almost two-thirds of the high-poverty neighborhoods in 1980 were still very poor almost forty years later.

Being born and raised in grinding, persistent poverty damages children’s long-term outcomes . Moreover, when families live for long periods in such conditions it is not only deleterious to the family, but the impact on the family differs significantly by race. As Sharkey notes, Black Americans are far more likely than whites to be “ stuck in place .” He found that two-thirds of Black Americans brought up in the poorest neighborhoods remain in the poorest quarter of neighborhoods after a generation; meanwhile only 40 percent of whites brought up in the poorest neighborhoods remain there. The long-term effects of being born and raised in a high-poverty neighborhood are thus far more persistent and damaging for Blacks than for whites.

The proportion of Blacks encountering that pattern is also greater than for other groups. Today, one in four Black Americans are stuck in high-poverty neighborhoods, compared with one in six Hispanics and just one in thirteen white Americans, according to a report by Paul A. Jargowsky for the New Century Foundation. Adding to the generational barriers facing young Black Americans, a 2018 study by Chetty finds that, after controlling for parental income, Black boys have lower incomes in adulthood than white boys in 99 percent of census tracts.

Example: Washington, D.C. and COVID-19

Washington, D.C. is a case study of how race and poverty closely overlap and how damaging racial segregation and poverty persists even in the nation’s capital. In a previous blog , we showed how the District of Columbia remained mostly segregated along east-west lines between 1990 and 2010. Moreover this “two cities” segregation was reflected in significant inequalities in urban poverty: some 94 percent of D.C. neighborhoods with a majority white population had less than 10 percent of their families living below the poverty line, while that was true of just 22 percent of majority Black neighborhoods.

This segregation in D.C. and other cities is linked not only to economic outcomes. It also shows up in susceptibility to many illnesses, such as COVID-19. The COVID-19 vulnerability index , released by the nonprofit Social Progress Imperative, harmonized a broad range of datasets to create a Census-tract-level, weighted-index of vulnerability of contracting COVID. The index is built out of sixteen indicators that map onto the following three themes: population demographics, underlying population health issues, and health infrastructure [1] .

Mapping the vulnerability index to D.C. underscores the east-west divide (Figure 2) and closely mirrors the sharp racial Black-white split in the city (Figure 1). The mapped vulnerability index indicates that Black Americans are at greater risk of infection, underscoring the pernicious effects of urban segregation and poverty. This is particularly worrying, given the rapid spread of the virus across the nation’s capital. Moreover, Black Americans are also more likely to face severe housing cost burdens and housing insecurity related to COVID-19.

Figure 1. White-Black racial divisions in Washington, D.C.

Figure 2. COVID-19 vulnerability index in Washington, DC

Taking Steps to Reduce Persistent Neighborhood Poverty

In addition to addressing structural racism and segregation in America, there needs to be a two-pronged strategy to tackle the problem of people stuck in persistently poor neighborhoods.

Strengthening communities . The first prong is to take steps to address the factors that make it likely that poverty and segregation will persist in neighborhoods by strengthening the economic and social fabric of the community. This means community-led strategies to spur economic improvement . Crucial for that objective are such actions as improving public schools and transportation, reducing crime, providing better health care, increasing access to healthy food options, and encouraging local entrepreneurship .

To be sure, that strategy poses a dilemma. Making a neighborhood more attractive as a place to live, work, and do business will lead to the benefits of more diversity and opportunity; but it also could lead to higher housing costs and the potential displacement of some existing lower-income residents. That pattern – a feature of “gentrification” – is seen in many Washington, D.C. neighborhoods as well as many other U.S. cities. Thus, tackling the roots of persistent poverty must be combined with actions to help make sure existing residents and local business owners can remain and share in an improving neighborhood . This requires government actions such as rental assistance for families, inclusionary zoning, and encouragements for developers to construct affordable multi-family housing. In addition, local governments need to promote employment training, apprenticeship programs, incentives for local hiring, and other steps to make it more likely that long-time residents can acquire new jobs in an improving community. And governments need to help build a foundation of homeowners among modest-income renters, such as through versions of Washington D.C.’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) program. This program enables groups renters to purchase their building as a co-op, but it prevents the new owners from selling their shares at market rates, thereby helping to retain a continued supply of affordable units for purchase.

Moving out . While strengthening the assets and opportunities within a persistently poor neighborhood is the preferred approach, in some neighborhoods that is extremely difficult. Thus a second important prong is to also to make it easier for families to move to areas with more resources and employment opportunities. In a 2015 study, Chetty examined a dataset of over five million families who moved across counties in the United States. He found that every additional year of childhood spent in a better environment significantly improves a child’s long-term outcomes. Strikingly, the study found that at least 50 percent of the variation in intergenerational economic mobility across the nation can be linked to the causal effects of neighborhood exposure during childhood. (Intergenerational mobility is a measure of the change in economic circumstances from one generation to the next.)

For some time, the research community was uncertain about the impact on earnings and educational success from encouraging families to move to better neighborhoods. To explore this, Chetty examined the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) program – a 1990s social experiment that examined the consequences of enabling low-income families with children in high-poverty neighborhoods to move to other communities. Chetty found that the positive effects on low-income households are strongest for pre-adolescent children, especially younger children (i.e. the group most harmed by living in persistent poverty). Moreover, the most noticeable impacts show up when these children reach college and working age , including increased college attendance and earnings, and reduced rates of single-parenthood.

Chetty concluded that policy should make it easier for low-income families to move from persistently poor neighborhoods to areas of greater opportunity through such policies as expanding housing vouchers and other rental assistance programs. To expand the supply of reasonably affordable housing available to such families in other neighborhoods, rental assistance needs to be combined with steps to increase the supply of affordable housing in more upscale communities through inclusionary zoning and other land-use reforms. And to make affordable housing more available to lower-income families moving to neighborhoods with more resources, this is the time to strengthen fair housing requirements. It is not the time to undermine them, as the Trump administration sought to do with its July 2020 rule change, which gives communities greater latitude to weaken the requirements .

An emphasis on access to opportunities. In parallel with these two approaches is the need to increase access to opportunities by better integrating cities. Promoting regional initiatives aimed at increasing the connectivity and mobility of urban residents, and connecting communities to regional assets and opportunities, making it easier for people in different communities to interact. This typically requires the expansion of an affordable transportation infrastructure. It also means attention to the heavy burden that urban sprawl and traffic congestion imposes on the poor, by encouraging greater urban density and building affordable housing closer to the city centers – creating greater proximity to jobs and services.

Mounting research underscores the damaging long-term effects for families of living in a segregated, under-resourced neighborhood. The research also indicates the benefits of enabling such families to move to areas of greater opportunity, especially for younger children; it also shows the importance of increasing diversity and resources within persistently poor communities. Growing evidence points to a series of public policy tools which can help obtain these results. What is needed now is a much greater determination to use them.

The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. They are currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article. The views presented here are those of the authors and do not represent the views of The World Bank or The Members of the Executive Board of Directors.

Shapefiles and geographic boundaries for graphs obtained from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry/ Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program.

[1] The full set of factors that were included in the analysis are included here: http://us-covid19-risk.socialprogress.org/

Related Content

Stuart M. Butler, Timothy Higashi, Nehath Sheriff

October 5, 2020

Stuart M. Butler

July 7, 2020

Economic Studies

Lauren Bauer, Bradley Hardy, Olivia Howard

April 17, 2024

Robert Greenstein

Harry J. Holzer

April 16, 2024

Advertisement

Understanding trends and drivers of urban poverty in American cities

- Published: 14 January 2022

- Volume 63 , pages 1663–1705, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Francesco Andreoli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0751-5520 1 , 2 ,

- Arnaud Mertens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2148-1427 2 ,

- Mauro Mussini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0770-8450 3 &

- Vincenzo Prete ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3990-0105 1

508 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Urban poverty arises from the uneven distribution of poor populations across neighborhoods of a city. We study the trend and drivers of urban poverty across American cities over the last 40 years. To do so, we resort to a family of urban poverty indices that account for features of incidence, distribution, and segregation of poverty across census tracts. Compared to the universally-adopted concentrated poverty index, these measures have a solid normative background. We use tract-level data to assess the extent to which demographics, housing, education, employment, and income distribution affect levels and changes in urban poverty. A decomposition study allows to single out the effect of changes in the distribution of these variables across cities from changes in their correlation with urban poverty. We find that demographics and income distribution have a substantial role in explaining urban poverty patterns, whereas the same effects remarkably differ when using the concentrated poverty indices.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A typology of U.S. metropolises by rent burden and its major drivers

Mikhail Samarin & Madhuri Sharma

Social Inequality and Spatial Segregation in Cape Town

Rural–nonrural divide in car access and unmet travel need in the United States

Weijing Wang, Sierra Espeland, … Dana Rowangould

Income segregation refers to the extent at which different income groups (poor, middle class, rich, for instance) are under- or over-represented in some neighborhoods compared to the city as whole. Measures of income segregation are conceptually different from concentrated poverty measures.

There are various criteria to establish whether two spatial units are close or not; among them, a main distinction can be made between the contiguity-based criteria (e.g., two spatial units are close if they share a common border) and the distance-based ones (e.g., two spatial units are close if the distance between their centroids is less than or equal to a chosen distance).

The relative weight of the difference in poverty incidence for the pair of tracts i and j in t , \(N_{i}^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t}}N_{j}^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t}}/\left( N^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t}}\right) ^{2}\) , may differ from that in \(t+1\) , \(N_{i}^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t+1}}N_{j}^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t+1}}/\left( N^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t+1}}\right) ^{2}\) , for effect of changes in the relative distribution of population across census tracts.

The interpretation of D is consistent with the approach suggested by O’Neill and Van Kerm ( 2008 ) to examine income convergence across countries. O’Neill and Van Kerm ( 2008 ) broke down the change in the Gini index, obtaining a two-term decomposition where a component assesses to what extent the incomes of poorer countries, initially at the bottom of the distribution, have grown proportionally more than those of richer countries at the top of the initial distribution. Such a component is therefore considered as a measure of \(\beta \) -convergence in income across countries O’Neill and Van Kerm ( 2008 ).

The overall poverty incidence, P / N , changes also when all tract poverty incidences vary in the same proportion, while both D and R are equal to 0 in that case.

c being the relative variation in overall poverty incidence, C is equal to \(1/\left( 1+c\right) \) and ranges between 0 and \(+\infty \) .

Both Census 1990 and 2000 and ACS determine a family poverty threshold by multiplying the base-year poverty thresholds (1982) by the average of the monthly inflation factors for the 12 months preceding the data collection. The poverty thresholds in 1982, by size of family and number of related children under 18 years can be found on the Census Bureau web-site: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html . For a four persons household with two underage children, the 1982 threshold is $9,783. Using the inflation factor of 2.35795 gives a poverty threshold for this family in 2013 of $23,067. If the disposable household income is below this threshold, then all four members of the household are recorded as poor in the census tract of residence, and included in the 2014 wave of ACS.

\(\beta \) here indicates the type of convergence and should not be confused with parameter \(\beta \) in Eq. 1 .

For a detailed description of the variables used to construct our indicators, see Chetty et al. ( 2017 ) and Tables 6 and 10 at https://opportunityinsights.org/data/ .

The unevenness dimension is captured by the dissimilarity index, measuring the proportion of poor individuals that should move to restore proportionality across the MSA tracts (about 30% on average across all MSAs), see Andreoli and Zoli ( 2014 ).

See Christafore and Leguizamon ( 2019 ) for alternative definitions of gentrification.

A spatial weights matrix representing the spatial relationships between census tracts in a MSA is needed to obtain the spatial decomposition. We specify a binary spatial weights matrix, the ij -th element of which equals 1 if tracts i and j are neighboring and 0 otherwise. A distance-based criterion is used to establish whether two tracts are neighboring Andreoli et al. ( 2021 ). More specifically, two tracts are considered close if the distance between their centroids is less than or equal to a cut-off distance, which is set equal to the minimum distance for which every tract in a MSA has at least one neighbor.

We do not report the fixed effects, which explains why the reported overall difference due to coefficients is not entirely explained by the variables shown in Table 9 .

Alvarado SE, Cooperstock A (2021) Context in continuity: the enduring legacy of neighborhood disadvantage across generations. Res Soc Stratif Mobil 74:100620

Google Scholar

Andreoli F, Mussini M, Prete V, Zoli C (2021) Urban poverty: measurement theory and evidence from American cities. J Econ Inequal (forthcoming)

Andreoli F, Peluso E (2018) So close yet so unequal: neighborhood inequality in American cities. ECINEQ Working paper p. 477

Andreoli F, Zoli C (2014) Measuring dissimilarity. Working Papers Series, Department of Economics, Univeristy of Verona, WP23

Ard K, Smiley K (2021) Examining the relationship between racialized poverty segregation and hazardous industrial facilities in the u.s. over time. Am Behav Sci 00027642211013417

Barro RJ, Sala-i-Martin X (1992) Convergence. J Polit Econ 100(2):223–251

Article Google Scholar

Baum-Snow N, Marion J (2009) The effects of low income housing tax credit developments on neighborhoods. J Public Econ 93(5):654–666

Bischoff K, Reardon SF (2014) Residential segregation by income, 1970–2009. Divers Dispar Am Enters New Century 43

Blinder AS (1973) Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. J Hum Resour 8(4):436–455

Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, Jackson JS (2001) Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav 151–165

Chetty R, Friedman JN, Saez E, Turner N, Yagan D (2017) Mobility report cards: the role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. Working Paper 23618, National Bureau of Economic Research

Chetty R, Hendren N (2018) The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: childhood exposure effects. Q J Econ 133(3):1107–1162

Chetty R, Hendren N, Katz LF (2016) The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: new evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. Am Econ Rev 106(4):855–902

Christafore D, Leguizamon S (2019) Neighbourhood inequality spillover effects of gentrification. Pap Reg Sci 98(3):1469–1484

Conley TG, Topa G (2002) Socio-economic distance and spatial patterns in unemployment. J Appl Econom 17(4):303–327

Dwyer RE (2012) Contained dispersal: the deconcentration of poverty in us metropolitan areas in the 1990s. City Commun 11(3):309–331

Huang Y, South S, Spring A, Crowder K (2021) Life-course exposure to neighborhood poverty and migration between poor and non-poor neighborhoods. Popul Res Policy Rev 40(3):401–429

Iceland J, Hernandez E (2017) Understanding trends in concentrated poverty: 1980–2014. Soc Sci Res 62:75–95

Jann B (2008) The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. Stata J 8(4):453–479

Jargowsky P (2015) The architecture of segregation. Century Found 7

Jargowsky PA (1997) Poverty and place: ghettos, barrios, and the American city. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Jargowsky PA (2013) Concentration of poverty in the new millennium. Century Found Rutgers Cent Urban Res Educ

Jargowsky PA, Bane MJ (1991) Ghetto pverty in the United States, 1970–1980. In: Washington DC (ed) The urban underclass. The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, pp 235–273

Jenkins SP, Brandolini A, Micklewright J, Nolan B (2013) The Great Recession and the distribution of household income. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Jenkins SP, Van Kerm P (2016) Assessing individual income growth. Economica 83(332):679–703

Kneebone E (2014) The growth and spread of concentrated poverty, 2000 to 2008–2012. Brook

Kneebone E, Nadeau C, Berube A (2011) The re-emergence of concentrated poverty. Brook Inst Metrop Oppor Ser

Lei M-K, Beach SR, Simons RL (2018) Biological embedding of neighborhood disadvantage and collective efficacy: influences on chronic illness via accelerated cardiometabolic age. Dev Psychopathol 30(5):1797–1815

Logan JR, Xu Z, Stults BJ (2014) Interpolating U.S. decennial census tract data from as early as 1970 to 2010: a longitudinal tract database. Prof Geogr 66(3):412–420 ( PMID: 25140068 )

Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Sanbonmatsu L (2012) Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science 337(6101):1505–1510

Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Sanbonmatsu L (2013) Long-term neighborhood effects on low-income families: evidence from moving to opportunity. Am Econ Rev 103(3):226–31

Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, Adam E, Duncan GJ, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Lindau ST, Whitaker RC, McDade TW (2011) Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes - a andomized social experiment. N Engl J Med 365(16):1509–1519 ( PMID: 22010917 )

Massey D, Denton NA (1993) American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Massey DS, Gross AB, Eggers ML (1991) Segregation, the concentration of poverty, and the life chances of individuals. Soc Sci Res 20(4):397–420

Massey DS, Gross AB, Shibuya K (1994) Migration, segregation, and the geographic concentration of poverty. Am Sociol Rev 425–445

Nandi A, Glass TA, Cole SR, Chu H, Galea S, Celentano DD, Kirk GD, Vlahov D, Latimer WW, Mehta SH (2010) Neighborhood poverty and injection cessation in a sample of injection drug users. Am J Epidemiol 171(4):391–398

Oaxaca R (1973) Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int Econ Rev 14(3):693–709

O’Neill D, Van Kerm P (2008) An integrated framework for analysing income convergence. Manch Sch 76(1):1–20

Pearman F (2019) The effect of neighborhood poverty on math achievement: evidence from a value-added design. Educ Urban Soc 51(2):289–307

Quillian L (2012) Segregation and poverty concentration: the role of three segregations. Am Sociol Rev 77:354–379

Rey SJ, Smith RJ (2013) A spatial decomposition of the Gini coefficient. Lett Spat Resour Sci 6:55–70

Sampson RJ, Sharkey P, Raudenbush SW (2008) Durable effects of concentrated disadvantage on verbal ability among african-american children. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105(3):845–852

Sharkey P, Elwert F (2011) The legacy of disadvantage: multigenerational neighborhood effects on cognitive ability. Am J Sociol 116(6):1934–81

Smith JA, Zhao W, Wang X, Ratliff SM, Mukherjee B, Kardia SL, Liu Y, Roux AVD, Needham BL (2017) Neighborhood characteristics influence dna methylation of genes involved in stress response and inflammation: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Epigenetics 12(8):662–673

Thiede B, Kim H, Valasik M (2018) The spatial concentration of america’s rural poor population: a postrecession update. Rural Sociol 83(1):109–144

Thierry A (2020) Association between telomere length and neighborhood characteristics by race and region in us midlife and older adults. Health Place 62:102272

Thompson JP, Smeeding TM (2013) Inequality and poverty in the United States: the aftermath of the Great Recession. FEDS Working Paper No. 2013-51

Vinopal K, Morrissey TW (2020) Neighborhood disadvantage and children’s cognitive skill trajectories. Child Youth Serv Rev 116:105231

Wang Q, Phillips NE, Small ML, Sampson RJ (2018) Urban mobility and neighborhood isolation in america’s 50 largest cities. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115(30):7735–7740

Wilson W (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclasses and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Wolf S, Magnuson KA, Kimbro RT (2017) Family poverty and neighborhood poverty: links with children’s school readiness before and after the great recession. Child Youth Serv Rev 79:368–384

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers and to conference participants at RES 2018 meeting (Sussex), LAGV 2018 (Aix en Provence) and ECINEQ 2019 (Paris) for commenting on an earlier draft of the paper. The usual disclaimer applies. Replication code for this article is accessible from the authors’ web-pages. This work was supported by the Luxembourg Fonds National de la Recherche (IMCHILD grant INTER/NORFACE/16/11333934/IMCHILD and PREFER-ME CORE grant C17/SC/11715898) and by the University of Verona (Ricerca di Base grants MOBILIFE-2017-RBVR17KFHX and PREOPP-2019-RBVR19FSFA).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, University of Verona, Via Cantarane 24, 37129, Verona, Italy

Francesco Andreoli & Vincenzo Prete

Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER), MSH, 11 Porte des Sciences, L-4366, Esch-sur-Alzette/Belval Campus, Luxembourg

Francesco Andreoli & Arnaud Mertens

Department of Economics, Management and Statistics, University of Milan-Bicocca, Piazza dell’Ateneo Nuovo 1, 20126, Milan, Italy

Mauro Mussini

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Francesco Andreoli .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Andreoli, F., Mertens, A., Mussini, M. et al. Understanding trends and drivers of urban poverty in American cities. Empir Econ 63 , 1663–1705 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02174-5

Download citation

Received : 11 April 2021

Accepted : 17 November 2021

Published : 14 January 2022

Issue Date : September 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02174-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Concentrated poverty

- Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition

- American Community Survey

- Spatial inequality

Mathematics Subject Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Urban Poverty

Introduction, definition of urban poverty.

- Individual Responsibility-Agency Theories and Culture of Dependency Approach

- The Structural Approach

- The Social Exclusion Approach

- Urban Poverty and the Neighborhood: The Neighborhood Effect

- The Effects of Poverty Concentration on Life Chances

- The Neighborhood as an Actor and as a Space for Resistance, Community-Building, and Social Innovation to Combat Urban Poverty

- Methodological Aspects of Urban Poverty Measurement

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- David Harvey

- Homelessness in the United States

- Rural-Urban Migration

- Social Movements in Cities

- Squatter Settlements

- Street Vendors

- Urban Anthropology

- Urban Sociology

- Urban Underclass

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Critical Urban Studies

- Hostile Design

- Urban Resilience

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Urban Poverty by Ana Belén Cano-Hila LAST REVIEWED: 15 October 2020 LAST MODIFIED: 15 October 2020 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780190922481-0037

Eradicating poverty in all its forms remains one of the greatest challenges facing humanity. For this reason, it was the primary sustainable development goal set for the United Nations Development Programme. While the number of people living in extreme poverty dropped by more than half between 1990 and 2015, too many are still struggling to meet the most basic human needs, and in particular 10 percent of the world’s population lives in extreme poverty; one person in every ten is extremely poor. As of 2015, about 736 million people still lived on less than US $1.90 a day; many lack food, clean drinking water, and proper sanitation. Rapid growth in countries such as China and India have lifted millions out of poverty, but progress has been uneven. Women are more likely to be poor than men as they have less paid work and education and own less property. Consequently, child poverty also is significant high; half of all people living in poverty are under eighteen. In fact, child poverty is one of the most important concerns and priorities for national and international organizations. Progress has also been limited in other regions, such as South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, which account for 80 percent of those living in extreme poverty. New threats brought on by climate change, conflict, and food insecurity mean that even more work is needed to lift people out of poverty. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a bold commitment to finish what we have started and end poverty in all its forms and dimensions by 2030. This involves targeting the most vulnerable, increasing basic resources and services, and supporting communities affected by conflict and climate-related disasters. In fact, urban poverty in megalopolises in the Global South is a relevant issue in international research on poverty. However, this entry is focused on urban poverty, understood as a set of economic and social difficulties that are found in advanced industrial cities. Sociology has always shown an interest in poverty, for example in the early Chicago school’s studies on urbanization, industrialization, immigration, and neighborhoods. While classic figures of sociology such as Max Weber, Émile Durkheim, Talcott Parsons, Georg Simmel, and Auguste Comte did not write a great deal about poverty, a strong concern with it exists in the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In recent decades, there has been growing interest in unifying the sociologies of poverty and paying more attention to poverty in the developing world, where the overwhelming majority of poor people live. Hence, this bibliography attempts to address the twofold goals of reviewing the main literature in the field as it exists today and seeking to identify frontier directions for emerging research.

Urban poverty refers to the set of economic and social difficulties that are found in industrialized cities and that are the result of a combination of processes such as: the establishment of comfortable living standards, the increase of individualism, processes of social fragmentation, and the dualization of the labor market, which translates into social dualization. Urban poverty is seen as a type of poverty with the primary characteristic that it occurs in industrialized societies, according to Rowntree 1901 , but also in the Global South, in accordance with Mitlin and Satterthwaite 2012 . Social researchers and scientists have traditionally addressed the definition of poverty using two concepts: absolute poverty and relative poverty. The concept of absolute poverty is based on the notion of subsistence, i.e., the basic conditions that need to be met for a person to live a healthy life from the physical point of view. The concept of relative poverty is based on the idea that the criteria of human subsistence are the same for everyone, in any context and under any circumstances. Therefore, it is understood that people below this established universal threshold are in a situation of poverty, regardless of their country’s level of human, technological, and economic development or its culture. Townsend 1979 understands that poverty is less about shortage of income and more about the inability of people on low incomes to participate actively in society. His thesis was criticized on the grounds that his measures of participation related to matters of choice rather than to need in which consumerism abounds and identity is often defined in terms of specific form of consumption. Among these critics, it is important to highlight Sen 1993 and Sen 2002 . Sen defines poverty as a deprivation of basic capabilities, particularly well-being/welfare and freedom. For him, poverty is a redistributive justice problem, which includes absolute and relative conditions of poverty. From the capabilities approach, Sen focuses the poverty analyses on purposes—understood as a necessary freedom for people to be who they want to be—not just only focused on income or the satisfaction of basic needs. More recent works on urban poverty like Mingione 1996 , Saraceno 2002 , Murie 2004 , and Cano 2019 suggest that in order to understand this situation today it is important to widen the focus of analysis, not merely paying attention to chronic poverty areas, but analyzing the living conditions of groups in disadvantaged contexts and placing special emphasis on the dynamics of impoverishment (unemployment, eviction, dependency on social aid, lack of social networks, stigma effect, and so on). Therefore, poverty not only means having insufficient resources for physical survival, but is also the set of circumstances that prevent full integration into a community, bearing in mind its living standards, as Marshall 1950 observes. New analyses of urban poverty need to understand it as a long-term, heterogeneous, and multidimensional phenomenon, and to focus attention on the processes that generate urban poverty.

Cano, Ana Belén. “Urban Poverty.” In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies . Edited by A. M. Orum, 1–7. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2019.

DOI: 10.1002/9781118568446.eurs0388

The author analyzes the conceptual and methodological framework of the concept of urban poverty, understanding it as a set of economic and social difficulties that are found in industrialized cities and that are the result of a combination of processes such as: the establishment of comfortable living standards, the rise of individualism, processes of social fragmentation, and the dualization of the labor market, which translates into social dualization.

Marshall, T. H. Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1950.

The author develops the concept of social citizenship, understood as the set of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights and duties of a member of a community. He argues that the notion of citizenship cannot be independent of the social and economic dimensions, since they decisively affect the capacities for political deliberation and social cohesion.

Mingione, Enzo. Urban Poverty and the Underclass . Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

DOI: 10.1002/9780470712900

This book brings together the main debates on poverty and the responses, analyzing the transformations in the various welfare systems and sociopolitical systems. It points out how the weakening of welfare programs reinforces the role of the community and the family as providers of welfare and social stability, which limits the mechanisms of social mobility.

Mitlin, Diana, and David Satterthwaite. Urban Poverty in the Global South: Scale and Nature . London: Routledge, 2012.

DOI: 10.4324/9780203104316

This book presents a much-needed systematic overview about the state of urban poverty in the Global South, from a historical and contemporary perspective.

Murie, Alan. “The Dynamics of Social Exclusion and Neighborhood Decline: Welfare Regimes, Decommodification, Housing, and Urban Inequality.” In Cities of Europe: Changing Contexts, Local Arrangements, and the Challenge to Urban Cohesion . Edited by Yuri Kazepov, 151–169. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004.

DOI: 10.1002/9780470694046.ch7

This book develops a comparison between European cities, focusing on the interrelationship between social exclusion, segregation, and governance.

Rowntree, B. Seebohm. Poverty: A Study of Town Life London: Macmillan, 1901.

This work is one of the main classics and reference works in the study of urban poverty. One of his main contributions was to understand poverty as a consequence of certain social processes, and not as a cause of them. Coherently with this, he contributed proposals toward new policies and social aid programs.

Saraceno, Chiara. Social Assistance Dynamics in Europe: International and Local Poverty Regimes . Bristol, UK: Policy Press, 2002.

This book analyzes different models of social assistance in various European countries. It focuses its analysis on the interaction between personal biographies and political contexts.

Sen, Amartya K. “Capacidad y bienestar.” In Calidad de Vida Edited by Martha C. Nussbaum and Amartya Sen, 54–83. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1993.

This book is made up of a set of multidisciplinary essays on different visions of the concept of quality of life. It provides an interesting rethinking of the concept, with the intention of designing new methods of analysis, developing alternative approaches and establishing some useful proposals regarding this topic of growing interest in the academic community.

Sen, Amartya K. Rationality and Freedom Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002.

Amartya Sen brings clarity and insight to three difficult issues: rationality, freedom, and justice. This capability approach is utilized to illuminate the demands of rationality in individual choice (decisions under uncertainty) as well as social choice (cost benefit analysis and environmental assessment).

Townsend, Peter. Poverty in the United Kingdom. A Survey of Household Resources and Standards of Living . London: Penguin, 1979.

This author studied how relative deprivation includes both material and social aspects. One of his main contributions is to relate income levels, poverty and participation.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Urban Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Agglomeration

- Airports and Urban Development

- Anthropology, Urban

- Austerity Urbanism

- Border Cities

- Business Improvement Districts

- Chicago School of Urban Sociology, The

- Cities, Social Movements in

- City Beautiful Movement

- Climate Change and Cities

- Clusters, Regional

- Commons, Urban

- Company Towns in the United States

- Creative Class

- Early American Republic, Cities in the

- Economics, Urban

- Harvey, David

- Infrastructure, Urban

- Innovation Systems, Urban

- Irregular Migration and the City

- Lefebvre, Henri

- Los Angeles

- Megaprojects

- Metabolism, Urban

- Mexico City

- Morphology, Urban

- Natural Disasters and their Impact on Cities

- Ottoman Empire, Cities of the

- Peri-Urban Development

- Poverty, Urban

- Religion, Urban

- Retail Districts

- San Francisco

- Sanctuary Cities

- Sexualities, Urban

- Smart Growth

- Sociology, Urban

- Soundscapes, Urban

- Suburbs, Black

- Suburbs in the United States, Asian and Asian American

- Tiebout, Charles

- Underclass, Urban

- Urban Heat Islands

- Urban History, American

- Urbanism, Postcolonial

- Urbanisms, Precolonial

- Urbanization, African

- Urbanization, Arab Middle Eastern

- Urbanization, Indian

- Warfare, Urban

- Washington, DC

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences