Curriculum Development Proposal

A curriculum development project creates a cohesive plan of instruction that addresses a curricular goal for the school or classroom. The curriculum plan should encompass classroom instruction in a given subject area for at least one semester or involve the entire school for at least one instructional unit. The curriculum should demonstrate a link between research findings, instruction, and student outcomes. Once created, the curriculum should be implemented and its effectiveness evaluated.

The curriculum development project proposal will be a five- to seven-page paper that communicates the goals and plans to achieve those goals to the advisor and committee members. The following outline may guide the proposal:

I. INTRODUCTION

- Identify the purpose of the project or the problem it seeks to address

- Give evidence of the problem or importance of the project

- State the project goal

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

- A reporting of the literature that frames the problem the curriculum is addressing, gives evidence of other attempts to address this educational issue, studies research on the effectiveness of such attempts, and describes educational theory or practice that serves as a rationale for the curriculum design and methods of instructions and assessment

III. DESIGN

- Describe the procedure for development of the project

- Describe how the curriculum will be implemented

- Outline an assessment or evaluation of the curriculum’s effectiveness

- Convey your plan for assessing the data you collect from the assessment plan

- Describe any limitations your study may have

IV. REFERENCES

V. APPENDICES

- Consumer Info

- Financial Aid

- Financial Services

- Fitness Center

- Organizations

- Print Services

- Master Calendar

- Photo Gallery

- Tech Support

Martin Luther College 1995 Luther Court New Ulm, MN 56073 1 (507) 354-8221

Need Help? Contact Us

Research and Curricula

- First Online: 13 September 2019

Cite this chapter

- Julie Sarama 4 &

- Douglas H. Clements 4

Part of the book series: Research in Mathematics Education ((RME))

1174 Accesses

1 Citations

Connecting curriculum development and research benefits both. Those designing curricula should ensure that their work is scientifically based and evaluated. Those studying existing curricula should understand the ways in which they were developed and validated (or not) and that a comprehensive evaluation program involves more than final outcomes. We use a curriculum research framework to draw implications for research in both development and evaluation projects. For each phase of the framework, we discuss how publishable research and curriculum development (R&D) might occur, as well as what opportunities there may be for evaluation research alone. In all cases, we briefly suggest methods.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

To us, the sine qua non of evaluation, but not the only approach; others include aesthetic (Eisner, 1998 ), narrative (Bruner, 1986 ), historical (Balfanz, 1999 ; Kilpatrick, 1992 ) and other perspectives.

Aguirre, J., Herbel-Eisenmann, B. A., Celedón-Pattichis, S., Civil, M., Wilkerson, T., Stephan, M., … Clements, D. H. (2017). Equity within mathematics education research as a political act: Moving from choice to intentional collective professional responsibility. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 48 (2), 124–147. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.48.2.0124

Article Google Scholar

Bailey, D. H., Duncan, G. J., Watts, T. W., Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2018). Risky business: Correlation and causation in longitudinal studies of skill development. American Psychologist, 73 (1), 81–94.

Balfanz, R. (1999). Why do we teach young children so little mathematics? Some historical considerations. In J. V. Copley (Ed.), Mathematics in the early years (pp. 3–10). Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Google Scholar

Baroody, A. J. (1987). Children’s mathematical thinking: A developmental framework for preschool, primary, and special education teachers . New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Baroody, A. J. (2016). Curricular approaches to introducing subtraction and fostering fluency with basic differences in grade 1. In R. Bracho (Ed.), The development of number sense: From theory to practice. Monograph of the Journal of Pensamiento Numérico y Algebraico (Numerical and Algebraic Thought) (Vol. 10, pp. 161–191). University of Granada. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1147345

Baroody, A. J., Cibulskis, M., Lai, M.-l., & Li, X. (2004). Comments on the use of learning trajectories in curriculum development and research. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 6 , 227–260.

Baroody, A. J., & Coslick, R. T. (1998). Fostering children’s mathematical power: An investigative approach to K-8 mathematics instruction . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Book Google Scholar

Baroody, A. J., & Purpura, D. J. (2017). Number and operations. In J. Cai (Ed.), Handbook for research in mathematics education (pp. 308–354). Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM).

Barrett, J. E., Cullen, C. J., Sarama, J., Clements, D. H., Klanderman, D., Miller, A. L., & Rumsey, C. (2011). Children’s unit concepts in measurement: A teaching experiment spanning grades 2 through 5. ZDM-The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 43 , 637. https://doi.org/10.1080/10986065.2012.625075

Battista, M. T., & Clements, D. H. (2000). Mathematics curriculum development as a scientific endeavor. In A. E. Kelly & R. A. Lesh (Eds.), Handbook of research design in mathematics and science education (pp. 737–760). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Blanton, M., Brizuela, B. M., Gardiner, A. M., Sawrey, K., & Newman-Owens, A. (2015). A learning trajectory in 6-year-olds’ thinking about generalizing functional relationships. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 46 (5), 511–558.

Brade, G. (2003). The effect of a computer activity on young children’s development of numerosity estimation skills . Buffalo, NY: University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

Brown, A. L., & Campione, J. C. (1996). Psychological theory and the design of innovative learning environments: On procedures, principles, and systems. In R. Glaser (Ed.), Innovations in learning: New environments for education (pp. 289–325). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burkhardt, H. (2006). From design research to large-scale impact: Engineering research in education. In J. V. d. Akker, K. P. E. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney, & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design research. London: Routledge (pp. 133–162). London: Routledge.

Cai, J. (Ed.). (2017). Compendium for research in mathematics education . Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Cai, J., Morris, A., Hohensee, C., Hwang, S., Robison, V., & Hiebert, J. (2017). Clarifying the impact of educational research on learning opportunities. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 48 (3), 230–236.

Casey, B. M., Dearing, E., Vasilyeva, M., Ganley, C. M., & Tine, M. (2011). Spatial and numerical predictors of measurement performance: The moderating effects of community income and gender. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103 (2), 296–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022516

Celedòn-Pattichis, S., Peters, S. A., Borden, L. L., Males, J. R., Pape, S. J., Chapman, O., … Leonard, J. (2018). Asset-based approaches to equitable mathematics education research and practice. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 49 (4), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.49.4.037

Cheng, Y.-L., & Mix, K. S. (2012). Spatial training improves children’s mathematics ability. Journal of Cognition and Development, 15 (1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2012.725186

Choppin, J., Roth McDuffie, A., Drake, C., & Davis, J. (2018). Curriculum ergonomics: Conceptualizing the interactions between curriculum design and use. International Journal of Educational Research, 92 , 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2018.09.015

Civil, M. (2002). Everyday mathematics, mathematicians’ mathematics, and school mathematics: Can we bring them together? In Everyday and academic mathematics in the classroom: Journal for Research in Mathematics Education Monograph Number 11 (pp. 40–62). Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Civil, M. (2016). STEM learning research through a funds of knowledge lens. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 11 (1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9648-2

Clarke, D. M., Cheeseman, J., Gervasoni, A., Gronn, D., Horne, M., McDonough, A., … Rowley, G. (2002). Early Numeracy Research Project final report . Department of Education, Employment and Training, the Catholic Education Office (Melbourne), and the Association of Independent Schools Victoria.

Clements, D. H. (2002). Linking research and curriculum development. In L. D. English (Ed.), Handbook of international research in mathematics education (pp. 599–636). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Clements, D. H. (2007). Curriculum research: Toward a framework for ‘research-based curricula. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 38 (1), 35–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/30034927

Clements, D. H. (2008). Design experiments and curriculum research. In A. E. Kelly, R. A. Lesh, & J. Y. Baek (Eds.), Handbook of innovative design research in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Education (pp. 761–776). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Clements, D. H., & Battista, M. T. (2000). Designing effective software. In A. E. Kelly & R. A. Lesh (Eds.), Handbook of research design in mathematics and science education (pp. 761–776). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2000/2018). Building Blocks fidelity of implementation . Buffalo, NY/Denver, CO: University of Buffalo, State University of New York/University of Denver.

Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2004). Learning trajectories in mathematics education. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 6 , 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327833mtl0602_1

Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2007a). Effects of a preschool mathematics curriculum: Summative research on the Building Blocks project. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 38 (2), 136–163.

Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2007b/2013). Building blocks (Vols. 1 and 2). Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Education.

Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2013). Rethinking early mathematics: What is research-based curriculum for young children? In L. D. English & J. T. Mulligan (Eds.), Reconceptuallizing early mathematics learning (pp. 121–147). Dordrecht, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6440-8_7

Chapter Google Scholar

Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2014a). Learning and teaching early math: The learning trajectories approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2014b). Learning trajectories: Foundations for effective, research-based education. In A. P. Maloney, J. Confrey, & K. H. Nguyen (Eds.), Learning over time: Learning trajectories in mathematics education (pp. 1–30). New York, NY: Information Age Publishing.

Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2016). Math, science, and technology in the early grades. The Future of Children, 26 (2), 75–94.

Clements, D. H., Sarama, J., & DiBiase, A.-M. (2004). Engaging young children in mathematics: Standards for early childhood mathematics education . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Clements, D. H., Sarama, J., Spitler, M. E., Lange, A. A., & Wolfe, C. B. (2011). Mathematics learned by young children in an intervention based on learning trajectories: A large-scale cluster randomized trial. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 42 (2), 127–166. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.42.2.0127

Clements, D. H., Sarama, J., Wolfe, C. B., & Spitler, M. E. (2015). Sustainability of a scale-up intervention in early mathematics: Longitudinal evaluation of implementation fidelity. Early Education and Development, 26 (3), 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2015.968242

Clements, D. H., Wilson, D. C., & Sarama, J. (2004). Young children’s composition of geometric figures: A learning trajectory. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 6 , 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327833mtl0602_1

Cobb, P. (2001). Supporting the improvement of learning and teaching in social and institutional context. In S. Carver & D. Klahr (Eds.), Cognition and instruction: Twenty-five years of progress (pp. 455–478). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cobb, P. (2007). Putting philosophy to work: Coping with multiple theoretical perspectives. In F. K. Lester Jr. (Ed.), Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (Vol. 1, pp. 3–38). New York, NY: Information Age Publishing.

Cobb, P., Confrey, J., diSessa, A., Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (2003). Design experiments in educational research. Educational Researcher, 32 (1), 9–13.

Cobb, P., & McClain, K. (2002). Supporting students’ learning of significant mathematical ideas. In G. Wells & G. Claxton (Eds.), Learning for life in the 21st century: Sociocultural perspectives on the future of education (pp. 154–166). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Confrey, J., & Lachance, A. (2000). Transformative teaching experiments through conjecture-driven research design. In A. E. Kelly & R. A. Lesh (Eds.), Handbook of research design in mathematics and science education (pp. 231–265). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Confrey, J., Maloney, A. P., Nguyen, K. H., & Rupp, A. A. (2014). Equipartitioning: A foundation for rational number reasoning. Elucidation of a learning trajectory. In A. P. Maloney, J. Confrey, & K. H. Nguyen (Eds.), Learning over time: Learning trajectories in mathematics education (pp. 61–96). New York, NY: Information Age Publishing.

Confrey, J., Rupp, A. A., Maloney, A. P., & Nguyen, K. H. (2012). Toward developing and representing a novel learning trajectory for equipartitioning: Literature review, diagnostic assessment design, and explanatory item response modeling .

Danesi, M. (2009, April 24). Puzzles and the brain . Retrieved October 11, 2018, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brain-workout/200904/puzzles-and-the-brain

Doabler, C. T., Clarke, B., Fien, H., Baker, S. K., Kosty, D. B., & Cary, M. S. (2014). The science behind curriculum development and evaluation: Taking a design science approach in the production of a tier 2 mathematics curriculum. Learning Disability Quarterly, 38 (2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731948713520555

Donegan-Ritter, M. M., & Zan, B. (2017). Designing and implementing inclusive STEM activities for early childhood. In C. Curran & A. J. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of research on classroom diversity and inclusive education practice (pp. 222–249). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2520-2.ch010

Drake, C., Land, T. J., & Tyminski, A. M. (2014). Using educative curriculum materials to support the development of prospective teachers’ knowledge. Educational Researcher, 43 (3), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14528039

Eisner, E. W. (1998). The primacy of experience and the politics of method. Educational Researcher, 17 (5), 15–20.

Ernest, P. (1995). The one and the many. In L. P. Steffe & J. Gale (Eds.), Constructivism in education (pp. 459–486). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Foster, M. E., Anthony, J. L., Clements, D. H., Sarama, J., & Williams, J. J. (2018). Hispanic dual language learning kindergarten students’ response to a numeracy intervention: A randomized control trial. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 43 , 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.01.009

Franke, M. L., Kazemi, E., & Battey, D. (2007). Mathematics teaching and classroom practice. In F. K. Lester Jr. (Ed.), Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (Vol. 1, pp. 225–256). New York, NY: Information Age Publishing.

Frye, D., Baroody, A. J., Burchinal, M. R., Carver, S., Jordan, N. C., & McDowell, J. (2013). Teaching math to young children: A practice guide . Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Fuson, K. C. (1992). Research on learning and teaching addition and subtraction of whole numbers. In G. Leinhardt, R. Putman, & R. A. Hattrup (Eds.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 53–187). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gravemeijer, K. P. E. (1994). Educational development and developmental research in mathematics education. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 25 , 443–471.

Greenwald, A. G., Pratkanis, A. R., Leippe, M. R., & Baumgardner, M. H. (1986). Under what conditions does theory obstruct research progress? Psychological Review, 93 , 216–229.

Heck, D. J., Chval, K. B., Weiss, I. R., & Ziebarth, S. W. (Eds.). (2012). Approaches to studying the enacted mathematics curriculum . Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Hiebert, J. C. (1999). Relationships between research and the NCTM standards. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 30 , 3–19.

Kilpatrick, J. (1992). A history of research in mathematics education. In D. A. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 3–38). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Kulik, J. A., & Fletcher, J. D. (2016). Effectiveness of intelligent tutoring systems: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 86 (1), 42–78. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315581420

Lagemann, E. C. (1997). Contested terrain: A history of education research in the United States, 1890–1990. Educational Researcher, 26 (9), 5–17.

Lamberg, T. D., & Middleton, J. A. (2009). Design research perspectives on transitioning from individual microgenetic interviews to a whole-class teaching experiment. Educational Researcher, 38 , 233–245. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09334206

Langhorst, P., Ehlert, A., & Fritz, A. (2012). Non-numerical and numerical understanding of the part-whole concept of children aged 4 to 8 in word problems. Journal für Mathematik-Didaktik, 33 (2), 233–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13138-012-0039-5

Larson, R. S., Dearing, J. W., & Backer, T. E. (2017). Strategies to scale up social programs: Pathways, partnerships and fidelity . Retrieved from The Wallace Foundation website: wallacefoundation.org .

Lesh, R. A., & Kelly, A. E. (2000). Multitiered teaching experiments. In A. E. Kelly & R. A. Lesh (Eds.), Handbook of research design in mathematics and science education (pp. 197–230). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Lester, F. K., Jr., & Wiliam, D. (2002). On the purpose of mathematics education research: Making productive contributions to policy and practice. In L. D. English (Ed.), Handbook of international research in mathematics education (pp. 489–506). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Lewis, C. C., & Tsuchida, I. (1998). A lesson is like a swiftly flowing river: How research lessons improve Japanese education. American Educator, 12 , 14–17; 50–52.

Lloyd, G. M., Cai, J., & Tarr, J. E. (2017). Issues in curriculum studies: Evidence-based insights and future directions. In J. Cai (Ed.), Compendium for research in mathematics education (pp. 824–852). Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

MacDonald, B. L. (2015). Ben’s perception of space and subitizing activity: A constructivist teaching experiment. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 27 (4), 563–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-015-0152-0

Maloney, A. P., Confrey, J., & Nguyen, K. H. (Eds.). (2014). Learning over time: Learning trajectories in mathematics education . New York, NY: Information Age Publishing.

May, H., Gray, A., Sirinides, P., Goldsworthy, H., Armijo, M., Sam, C., … Tognatta, N. (2015). Year one results from the multisite randomized evaluation of the i3 scale-up of reading recovery. American Educational Research Journal, 52 (3), 547–581. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214565788

McClain, K., Cobb, P., Gravemeijer, K. P. E., & Estes, B. (1999). Developing mathematical reasoning within the context of measurement. In L. V. Stiff & F. R. Curcio (Eds.), Developing mathematical reasoning in grades K-12 (pp. 93–106). Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice, 31 , 132–141.

Moyer-Packenham, P. S., Shumway, J. F., Bullock, E., Tucker, S. I., Anderson-Pence, K. L., Westenskow, A., … Jordan, K. (2015). Young children’s learning performance and efficiency when using virtual manipulative mathematics iPad apps. Journal of Computers in Mathematics and Science Teaching, 34 (1), 41–69.

Murata, A. (2004). Paths to learning ten-structured understanding of teen sums: Addition solution methods of Japanese Grade 1 students. Cognition and Instruction, 22 , 185–218.

National Research Council. (2004). On evaluating curricular effectiveness: Judging the quality of K-12 mathematics evaluations . Washington, DC: Mathematical Sciences Education Board, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. (2009). Mathematics learning in early childhood: Paths toward excellence and equity . Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12519

NGA/CCSSO. (2010). Common core state standards . Washington, DC: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers.

Nguyen, T., Watts, T. W., Duncan, G. J., Clements, D. H., Sarama, J., Wolfe, C. B., & Spitler, M. E. (2016). Which preschool mathematics competencies are most predictive of fifth grade achievement? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 36 , 550–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.02.003

Penuel, W. R., Confrey, J., Maloney, A. P., & Rupp, A. A. (2014). Design decisions in developing assessments of learning trajectories: A case study. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 23 (1), 47–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2013.866118

Penuel, W. R., & Shepard, L. A. (2016). Assessment and teaching. In D. H. Gitomer & C. A. Bell (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching (5th ed., pp. 787–850). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association. https://doi.org/10.3102/978-0-935302-48-6_12

Presmeg, N. C. (2007). The role of culture in teaching and learning mathematics. In F. K. Lester Jr. (Ed.), Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (Vol. 1, pp. 435–458). New York, NY: Information Age Publishing.

Presmeg, N. C., & Barrett, J. E. (2003). Lesson study characterized as a multi-tiered teaching experiment . Paper presented at the Twenty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, Hawai’i.

Remillard, J. T. (2005). Examining key concepts in research on teachers’ use of mathematics curricula. Review of Educational Research, 75 (2), 211–246.

Rittle-Johnson, B., Fyfe, E. R., & Zippert, E. (2018). The roles of patterning and spatial skills in early mathematics development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46 , 166–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.03.006

Russek, B. E., & Weinberg, S. L. (1993). Mixed methods in a study of implementation of technology-based materials in the elementary classroom. Evaluation and Program Planning, 16 , 131–142.

Sakakibara, T. (2014). Mathematics learning and teaching in Japanese preschool: Providing appropriate foundations for an elementary schooler’s mathematics learning. International Journal of Educational Studies in Mathematics, 1 (1), 16–26.

Sarama, J., & Clements, D. H. (2008). Linking research and software development. In G. W. Blume & M. K. Heid (Eds.), Research on technology and the teaching and learning of mathematics: Volume 2, cases and perspectives (Vol. 2, pp. 113–130). New York, NY: Information Age Publishing.

Sarama, J., & Clements, D. H. (2009). Early childhood mathematics education research: Learning trajectories for young children . New York, NY: Routledge.

Sarama, J., Clements, D. H., & Henry, J. J. (1998). Network of influences in an implementation of a mathematics curriculum innovation. International Journal of Computers for Mathematical Learning, 3 , 113–148.

Sarama, J., Clements, D. H., Starkey, P., Klein, A., & Wakeley, A. (2008). Scaling up the implementation of a pre-kindergarten mathematics curriculum: Teaching for understanding with trajectories and technologies. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 1 (1), 89–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345740801941332

Sarama, J., Clements, D. H., & Vukelic, E. B. (1996). The role of a computer manipulative in fostering specific psychological/mathematical processes. In E. Jakubowski, D. Watkins, & H. Biske (Eds.), Proceedings of the 18th annual meeting of the North America Chapter of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education (Vol. 2, pp. 567–572). Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse for Science, Mathematics, and Environmental Education.

Sarama, J., Clements, D. H., Wolfe, C. B., & Spitler, M. E. (2012). Longitudinal evaluation of a scale-up model for teaching mathematics with trajectories and technologies. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 5 (2), 105–135. doi:10.1080119345747.2011.627980.

Schmidt, W. H., & Houang, R. (2012). Curricular coherence and the common core state standards for mathematics. Educational Researcher, 41 (8), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12464517

Schoenfeld, A. H. (2002). Research methods in (mathematics) education. In L. D. English (Ed.), Handbook of international research in mathematics education (pp. 435–487). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (2016). 100 years of curriculum history, theory, and research. Educational Researcher, 45 (2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X16639025

Siegler, R. S. (2006). Microgenetic analyses of learning. In W. Damon, R. M. S. E. Lerner, D. Kuhn, & R. S. V. E. Siegler (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Volume 2: Cognition, perception, and language (6th ed., pp. 464–510). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Silver, E. A., & Herbst, P. G. (2007). Theory in mathematics education scholarship. In F. K. Lester Jr. (Ed.), Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (Vol. 1, pp. 39–67). New York, NY: Information Age Publishing.

Simon, M. A. (1995). Reconstructing mathematics pedagogy from a constructivist perspective. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 26 (2), 114–145. https://doi.org/10.2307/749205

Simon, M. A., Placa, N., & Avitzur, A. (2016). Participatory and anticipatory stages of mathematical concept learning: Further empirical and theoretical development. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 47 (1), 63–93.

Simon, M. A., Saldanha, L., McClintock, E., Akar, G. K., Watanabe, T., & Zembat, I. O. (2010). A developing approach to studying students’ learning through their mathematical activity. Cognition and Instruction, 28 (1), 70–112.

Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant observation . New York, NY: Holt, Rhinehart & Winston.

Steffe, L. P., Thompson, P. W., & Glasersfeld, E. v. (2000). Teaching experiment methodology: Underlying principles and essential elements. In A. E. Kelly & R. A. Lesh (Eds.), Handbook of research design in mathematics and science education (pp. 267–306). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Stein, M. K., & Kaufman, J. H. (2010). Selecting and supporting the use of mathematics curricula at scale. American Educational Research Journal, 47 (3), 663–693.

Stein, M. K., Remillard, J. T., & Smith, M. S. (2007). How curriculum influences student learning. In F. K. Lester Jr. (Ed.), Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (Vol. 1, pp. 319–369). New York, NY: Information Age Publishing.

Stephan, M., Cobb, P., Gravemeijer, K. P. E., & Estes, B. (2001). The role of tools in supporting students’ development of measuring conceptions. In A. Cuoco (Ed.), The roles of representation in school mathematics (pp. 63–76). Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Streefland, L. (Ed.). (1991). Realistic mathematics education in primary school . Utrecht, The Netherlands: Freudenthal Institute, Utrecht University.

Szilagyi, J., Sarama, J., & Clements, D. H. (2013). Young children’s understandings of length measurement: Evaluating a learning trajectory. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 44 , 581–620.

Sztajn, P., Confrey, J., Wilson, P. H., & Edgington, C. (2012). Learning trajectory based instruction: Toward a theory of teaching. Educational Researcher, 41 , 147–156. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12442801

Van den Brink, F. J. (1991). Realistic arithmetic education for young children. In L. Streefland (Ed.), Realistic mathematics education in primary school (pp. 77–92). Utrecht, The Netherlands: Freudenthal Institute, Utrecht University.

Van Dooren, W., De Bock, D., Hessels, A., Janssens, D., & Verschaffel, L. (2004). Remedying secondary school students’ illusion of linearity: A teaching experiment aiming at conceptual change. Learning and Instruction, 14 (5), 485–501.

Verdine, B. N., Golinkoff, R. M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Newcombe, N. S. (2017). Links between spatial and mathematical skills across the preschool years. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 82 (1, Serial No. 324). Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mono.v82.1/issuetoc . https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12280

Whitehurst, G. J. (2009). Don’t forget curriculum . Retrieved from Brown Center on Education Policy, The Brookings Institution website http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2009/1014_curriculum_whitehurst.aspx

Wilson, M. (2012). Responding to a challenge that learning progressions pose to measurement practice: Hypothesized links between dimensions of the outcome progression. In A. C. Alonzo & A. W. Gotwals (Eds.), Learning progressions in science (pp. 317–344). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Download references

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through grants R305K05157 and R305A110188, and also by the National Science Foundation, through grants ESI-9730804 and REC-0228440. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the IES or NSF. Although the research is concerned with the scale-up model, not particular curricula, a minor component of the intervention used in this research has been published by the authors, who thus could have a vested interest in the results. An external auditor oversaw the research design, data collection, and analysis, and other researchers independently confirmed findings and procedures. The authors wish to express appreciation to the school districts, teachers, and children who participated in this research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA

Julie Sarama & Douglas H. Clements

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Douglas H. Clements .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Mathematics Education, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA

Keith R. Leatham

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Sarama, J., Clements, D.H. (2019). Research and Curricula. In: Leatham, K.R. (eds) Designing, Conducting, and Publishing Quality Research in Mathematics Education. Research in Mathematics Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23505-5_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23505-5_5

Published : 13 September 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-23504-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-23505-5

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Curriculum proposals.

- Edmund C. Short Edmund C. Short The Pennsylvania State University and University of Central Florida

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1500

- Published online: 25 March 2021

Curriculum proposals are sets of visionary statements intended to project what some person or group believes schools or school systems should adopt and utilize in formulating their actual curriculum policies and programs. Curriculum proposals are presented when there is a perceived need for change from curriculum that is currently in place. The specific changes stated in a curriculum proposal can be either quite limited or very comprehensive. If a totally restructured curriculum is recommended, particular prescriptions are necessarily based on some overall conception of what curriculum is by definition and what its constituent elements are, and therefore what topics are to be addressed in a curriculum proposal. Attempts have been made to conceptualize curriculum holistically, as an entity clearly distinguished from all other phenomena, but no agreed upon conception has emerged.

To provide a new theoretical and practically useful framework for how curriculum may be conceived, a 10-component conceptualization of curriculum has been stipulated, elucidated, and illustrated for use in designing curriculum policy, programmatic curriculum plans, or formal curriculum proposals. In this conceptualization, curriculum is defined as having the following interrelated components: (a) focal idea and intended purpose(s), (b) unique objective(s), (c) underlying assumptions and value commitments, (d) program organization, (e) substantive features, (f) the character of the student’s educational situation/activity/process, (g) unique approaches/methods for use by the teacher/educator, (h) program evaluation, (i) supportive arrangements, and (j) justifications/rationale for the whole curriculum. Any proposal for total curriculum change should make prescriptions related to all these components.

Discussion of other aspects related to curriculum proposals include how to locate existing curriculum proposals, how to analyze them in relation to this new conceptualization of curriculum, how to choose suitable ones among them for possible adoption, and how to translate a curriculum proposal into actual curriculum policies or plans.

- curriculum proposals

- curriculum plans

- curriculum policies

- curriculum components

- curriculum theory

- pre-k to 12 curriculum

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 28 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Character limit 500 /500

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Fam Med Community Health

- v.7(2); 2019

Curriculum development: a how to primer

Jill schneiderhan.

Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

Timothy C Guetterman

Margaret l dobson.

Curriculum development is a topic everyone in the field of medical education will encounter. Due to the breadth of ages and types of care provided in Family Medicine, family medicine faculty in particular need to be facile in developing effective curricula for medical students, residents, fellows and for faculty development. In the area of medical education, changing and evolving learning environments, as well as changing requirements necessitate new and innovative curricula to address these evolving needs. The process of developing a medical education curriculum can seem daunting but when broken down into smaller components can become very straightforward and easy to accomplish. This paper focuses on the curriculum development process using a six-step approach: performing a needs assessment, determining content, writing goals and objectives, selecting the educational strategies, implementing the curriculum and, finally, evaluating the curriculum. This process may serve as a template for Family Medicine educators, and all medical educators looking to design (or redesign) their own medical education curriculum.

Introduction

Developing curricula is an important topic at all levels of medical education, from teaching medical students and residents to developing ongoing professional education. Despite its importance, it is easy to slip into a pattern of ad hoc curriculum development with little attention to desired outcomes. To maximise the potential of any medical education initiatives, we present a systematic approach to developing and evaluating curricula. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to describe the curriculum development process over six steps: performing a needs assessment, determining content, writing goals and objectives, selecting the educational strategies, implementing the curriculum and finally, evaluating the curriculum.

The word curriculum originated in classical Latin where the original meaning was ‘running’ or ‘race course’. Over time, it transitioned to meaning ‘a course of study’ or more specifically, ‘a course offered by an educational institution’. 1 Curriculum in medical education can vary widely in size and scope, encompassing individual topics such as learning to take vital signs in the first year of medical school, to very large areas with longitudinal scope such as a curriculum on decreasing errors in hospitalised patients through improved transitions of care. For the purposes of this paper, we will refer to any planned educational experience as an example of a curriculum.

The exact nature of a curriculum should be seen as the ‘what’ of the educational experience, such as the description of the intended learning outcomes or the document used to describe these. The development of this description or document in a systematic and concrete way is the focus of this paper, which should in turn drive implementation.

There are several underlying assumptions in approaching curriculum development that are well articulated by David Kern. 2

First, educational programs have aims or goals, whether or not they are clearly articulated. Second, medical educators have a professional and ethical obligation to meet the needs of their learners, patients and society. Third, medical educators should be held accountable for the outcomes of their interventions. And fourth, a logical, systematic approach to curriculum development will help achieve these ends. (page 5).

The development of educational curriculum is by nature driven by the discipline itself. There have been profound changes to the field of medical education over the last several decades with a shift from simply delivering knowledge to the learner to teaching skills such as clinical reasoning among others. As the process has shifted so has the need for developing appropriate curricula to teach these new skills become more important. Within family medicine, in particular, there has also been a shift to thinking about preventative and population health which along with huge changes in practice environments have driven need for more diverse educational strategies.

Medical education curriculum development has largely drawn from general education curriculum development with refinement over time into a framework that is largely accepted and taught throughout the field of medical education. 2 We will use this framework, combined with our own experiences and published examples of curriculum development, to lay out a format that can be widely applied to whatever educational topic is attempting to be taught.

The framework outlined in this paper is a combination of previously articulated curriculum development approaches by Patricia Thomas and David Kern, 2 as well as the framework used in the University of Michigan Faculty Development Institute’s Workshop on Curriculum Development.

The six steps are:

- Performing a needs assessment and writing a rationale statement.

- Determining and prioritising content.

- Writing goals and objectives.

- Selecting teaching/educational strategies.

- Implementation of the curriculum.

- Evaluation and application of lessons learnt.

The prompts for the development of a curriculum can be multifactorial. They can be external, coming from outside the group, such as the requirements of accrediting bodies or less well-defined ‘movements’ in delivery of care models. Internal motivations may arise as well, for example, from review of learner’s performance evaluations or needs specific to the community being served by the learners.

The following is an example from the experience of one of the authors (JS) of this paper that was initially prompted by learner’s performance. During the review of residents’ performance at a small residency programme, it was noted that there was a slow rate of acquisition of communication skill milestones by a substantial number of learners, making it clear that the issue was less about the individual learners and more systemic in nature. On further reflection, it became clear there was not a specific educational strategy to teach this topic. This led to the formation of a working group to develop a curriculum to teaching communication skills. The group met several times and followed a specific curriculum development process. The process began by discussing if there was broad agreement that this curriculum needed to be developed and on what data that decision was being based on (step 1: performing a needs assessment and writing a rationale statement).

The next step was to determine what exactly was going to be addressed, and a process was undertaken to review both the milestones for communication skills given by the outside accrediting body for our programme and a review of the state of education around teaching communication skills in family medicine residency education (step 2: determining and prioritising content). Once we determined the content we wanted to cover, we expanded to what that would look like to the learner at the end of the curriculum, and then developed a set of goals and objectives for our curriculum (step 3: writing goals and objectives).

Next, we involved an educational specialist from our larger Graduate Medical Education Committee to help us in the selection of educational strategies. As we were a small programme, we did not have a specialist in communication skills; therefore, we were strategic in matching our strategies to the skills of our faculty teachers. From there, we organised the strategies into a formal curriculum with details of what would be taught, by whom and when (step 4: selecting teaching/educational strategies).

The next year, the curriculum was rolled out to the family medicine residents in the form of lectures and workshops, precepting strategies and feedback tools (step 5: implementation of the curriculum). Throughout the course of that year and into the next, we evaluated the individual components and also the milestones pertinent to our curriculum, and then returned to the overall plan and adjusted for improvement (step 6: evaluation and application of lessons learnt). Overall, the process was a success, the new curriculum was in place and over the next several years slow improvement in the attainment of milestones relevant to this curriculum was seen.

In the above example, the steps outlined were followed in a stepwise fashion, but that is not necessary to the success of a curriculum. In the case that a curriculum is already in place, evaluation may lead to revision, which in turn may lead to the development of a new needs assessment, but not necessarily new goals or objectives. It may become unclear why effort is being put into a certain area and a formal needs assessment becomes important to justify an already successful educational strategy. Each of these steps can be important in and of itself and may come into play at different times. The table 1 provides a summary of steps with examples.

Curriculum development steps

Step 1. Needs assessment/statement

The needs assessment helps us answer ‘Why’? In the case of curriculum development, the answer may be quite broad and should point to the distinction between the current teaching strategy surrounding a learning need and what should be changed about it. 2 At the start, it is wise to consider whose needs are the priority. This may start with a learner’s needs (either attitudinal and knowledge-based needs, readiness to learn or timing), but likely extends to the patients and communities for whom the learner will be caring. When justifying time or funding, an articulation of how this curriculum might meet regulatory or board requirements can be useful.

The mechanics of a needs assessment includes readily available information and the collection of new information. 2 The acquisition of new information can be structured (survey or medical knowledge assessment), semi-structured (series of discussions or a call to action based on sentinel event), research/data driven (data on learners’ performance or clinical quality data) or based on regulatory requirements. 3–5

A very basic example (see table 1 ), 2 experienced by one of the authors was the identification of a gap in knowledge leading to the development of a newly structured educational activity.

Once the needs assessment is finalised, and the needs have been articulated, a rationale statement should be agreed on. 3–5 This rationale statement is 1–3 lines that articulates the fundamental findings from the needs assessment to guide the development of the curriculum. The rationale statement can then be used to keep the curriculum on task. It is intended to be modified only if there is a serious oversight in the development. In this way, the needs assessment and rationale statement can truly render a solid foundation for the curriculum in development.

Step 2. Determining and prioritising content

This is the first step in beginning to articulate what is going to be included, a general description of the content, along with a prioritisation of that content. In the example of the communication skills curriculum referenced above, the content was determined both by working backwards from the milestone goals and also from reviewing what experts in the field have identified. In some cases, there will not be expert knowledge or milestones to work from, and in these cases, original research might be needed, such as surveys of experts in the field, or analysis of conversation around a difficult topic needing to be addressed. An example of this last strategy can be seen in a recent publication on addressing the topic of racism in medical education (see table 1 ). 2 6

Step 3. Writing goals and objectives

Although goals and objectives are often thought of as similar, there is a nuanced difference to them that should be considered. A goal is a general statement of the knowledge, skill or attitude to be attained by the learner and is often a description of the important content as determined in your earlier steps. In contrast, an objective is a specific measurable skill or attitude that the learner will be able to demonstrate at the end of the educational activity. While goals are helpful in defining the overall strategy, the objectives are necessary in order to measure if your curriculum is successful.

While writing goals is relatively simple, as they are general statements of knowledge, the writing of an objective is more challenging and will be discussed in more detail. Objectives need to be understood by both learners and instructors, and to that end, need to be as specific and measurable as possible.

This statement asks us to simply consider the basic elements of an objective: ‘Who will do how much of what by when? (page 51)’. 2 Perhaps, the most important component of this is the verb, or the ‘will do’ piece, which should be open to as few interpretations as possible. Good verbs to use may include ‘list’, ‘define’, ‘execute’ and ‘differentiate’, as opposed to verbs that should be avoided such as ‘know’, ‘understand’ or ‘appreciate’, which are vague and difficult to measure. 7

Table 2 below provides examples of how an important content area is translated into a goal and an objective and some examples of both poor and well-written objectives.

Examples of goals and objectives

Step 4. Selecting teaching/educational strategies

Selecting the teaching or educational strategies to deliver new curriculum helps predict its success. One early alignment to consider is the congruence between the topics (knowledge, affective or psychomotor) and teaching method. 2 Options for curriculum delivery are summarised in table 3 . When selecting a strategy, it is helpful to consider both the learner(s) and the teacher(s), as well as the material. If the relationship between teacher and learner is intended to be formative, or longitudinal, the strategy may favour the person teaching and likely incorporates some element of discussion. If the priority is garnering a basic level of skill/understanding of a stable topic and potentially assessing that knowledge, a web-based tool may be the right approach. When planning multiple sessions, it is helpful to consider overall structure to promote cohesiveness, but with variability between the sessions to meet the educational goals and objectives for that session. In Family Medicine, we are also especially attuned to consider the role of the team in implementation of new teaching, as team-based care is central to the practice of Family Medicine. This may push us to consider cross or interdisciplinary educational approaches. See tables 2 and 3 for examples.

Educational strategies

Step 5. Implementation

The implementation phase can be divided into several different steps starting with the identification of resources. Resources fall into four basic categories which include personnel, time, facilities and funding. 2 Personnel are the teaching faculty, administrative support, informational technology (if needed for computerised modules) and patients (if curriculum involves direct patient care). Time is often one of the most precious resources, given all that learners have to accomplish in the short time they are in school or residency, and includes didactic time as well as the time of all the personnel listed above. Facilities are the spaces such as classrooms or clinic sites where the learning will take place. Funding is all the direct financial costs or faculty compensation, along with any other hidden costs. Utilising existing resources (educational materials already developed, time already put aside in the curriculum, rooms already dedicated to teaching) can lower costs and increase the likelihood of success.

The next step is obtaining support internally from stakeholders to the curriculum, and at times externally, when funding or support for other resources is needed. Stakeholders are those most directly impacted by the curriculum and often include learners, the faculty doing the teaching and any administrative personnel needed. Having their support and enthusiasm is crucial to the success of any curriculum. External support becomes necessary when resources beyond what is available to the programme or school are needed, either financially or in terms of facilities. A great example of finding resources and support is seen in Noriea et al , where a curriculum to teach health disparities was developed which used nationally developed resources and partnered with local clinics for the offering of clinical experiences. 8

The next step is the design of the management plan, which details the actual step-by-step process of how the curriculum will be delivered. This should include the who, what, where and how for each component or teaching strategy. This is where anticipating any barriers that might arise during the role out of the curriculum may be anticipated in advance, with a plan to mitigate the barriers. A great example of this level of detailed plan is also seen in Noriea et al ’s study where they include a table that details out each didactic component of their curriculum, along with the assignments to the students and the teaching strategies being employed. 8

The last step in implementation is the actual role out. This is where all the work you have put in so far will pay off. It is important to pilot sections of the curriculum to enthusiastic stakeholders initially to both gain more support and also to identify and rectify any barriers to implementation so that the odds of success are increased. This pilot can be followed by a phasing-in, where new portions are added until the full curriculum is implemented.

Step 6. Evaluation

Evaluation is a process of determining the merit, value or worth of a programme. 9 Evaluation is often considered the final phase of curriculum development, but it should span the entire process and is often cyclical and iterative. Two major types of educational evaluation included here are formative and summative. 10 Formative evaluation is conducted early on, or at key points, during a programme in order to inform changes and identify opportunities for improvement. Summative evaluation, however, is an evaluation of outcomes that occurs in a more final phase of implementation. Summative evaluations are useful to make a judgement about whether a curriculum was successful, and for whom, in order to report back to stakeholders. A preparatory step is to consider early on whether to conduct either formative or summative evaluation, or both. Drawing from utilization-focused evaluation 11 and the steps in any research process, 10 the major steps of an evaluation are: (1) develop a clear plan to use evaluation results; (2) determine how to measure objectives; (3) collect data; (4) analyse data and (5) use evaluation results by applying lessons learnt.

Although it may seem counterintuitive, the first step of an evaluation is to consider who will use the evaluation results and how. Simply, an evaluation that is never used will not be worth the effort. A utilization plan should include and describe the dissemination plan (eg, a written report, presentations, discussion sections) and the specific audience for each. In addition, the utilization plan should detail what types of actions may be anticipated based on the results. For example, could the report lead to changing, ending or expanding the programme? The actual utilization occurs after the evaluation, but having a clear plan ahead of time can help to ensure the evaluation will actually influence the curriculum, with the goal of improving the learning itself, the experience of the learners and teachers and ultimately, patients and community members who will benefit from more skilled providers.

The next step is to determine how to measure learning objectives. This process is often called assessment and consists of operationalising objectives and determining how to collect data. Consider the learning objective: ‘The learner will be able to explain the difference in the pathophysiology of acute versus chronic pain’. Considerations include how to assess this objective, such as through tests, or other learner output. Of course, it must be more specific, such as whether the test is written or uses another form, the timing of the assessment, whether it will be repeated and what is considered proficiency. A norm-based assessment might compare student performance to other students to determine relative differences. A criterion-based assessment would have a particular cut-point that determines acceptable performance.

With planning efforts completed, the next steps are to collect and analyze data. Data collection might involve tests, interviews with students or instructors, performance assessments or other methods. 4 10 12 When using quantitative data, analysis occurs after all data have been collected. Analyzing pre-post differences can be particularly helpful in assessing whether learners may have changed. When using qualitative data, analysis begins as data are being collected and tends to be more iterative, with analysis informing subsequent data collection. 13

The final step is to use the evaluation results and apply lessons learnt to the curriculum. Guided by the utilization plan, this step consists of disseminating information to relevant stakeholders, and making use of the results to improve learning outcomes or the learning experience. This feedback and use of evaluation results is critical for continuing improvement of medical or professional education. Thus, the evaluation process often repeats as educators apply lessons learnt and then evaluate and iterate the improved curriculum.

Conclusions

Following a systematic approach to develop and evaluate curricula provides a structure to frame teaching and learning and in doing so makes this process accessible to all Family Medicine educators regardless of previous experience. The process may be applied to develop an entirely new curriculum or to modify an existing one. Curriculum development begins with conducting a needs assessment and developing a written rationale for the curriculum followed by determining and prioritising what content will be included in the curriculum. The third step is to clearly articulate the goals and write measurable objectives. Remaining goal oriented helps educators refrain from adding superfluous material. The fourth step is focused on how the curriculum will be delivered by selecting educational strategies. In the fifth step, educators determine what resources are needed on a practical level to implement the curriculum followed by the actual implementation. Finally, educators evaluate the curriculum and use those results to make changes.

The process we have presented encourages Family Medicine educators to systematically move through each step of curriculum development rather than take an ad hoc approach. By doing so, the educator becomes an expert in both their clinical subject and how best to educate learners in the topic. A structured approach helps ensure the work already being done can be shared widely through publication and presentation, if desired. Through the sharing of the curriculum development process, evaluation results or educational innovations with the broader scholarly community, Family Medicine educators and medical educators generally learn from one another’s experiences and the entire field is enriched.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Rania Ajilat and Lilly Pritula for their editorial assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conceptualisation, writing and review of this manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

- Undergraduate Admission

- Graduate Admission

- Tuition & Financial Aid

- Communications

- Health Sciences and Human Performance

- Humanities and Sciences

- Music, Theatre, and Dance

- IC Resources

- Office of the President

- Ithaca College at a Glance

- Awards and Accolades

- Five-Year Strategic Plan

- Public Health

- Directories

- Course Catalog

- Undergraduate

How to Develop Curriculum Proposals

The curriculum review and approval process has many layers and steps. If you are new to developing curriculum proposals, or if you haven't done it in a while, the H&S Curriculum Committee strongly urges you to review the following documents in advance of preparing proposals:

- HSCC Curriculum Guidelines - Detailed discussion of the proposal routing, review, and approval process, how to write an effective course/program rationale (excerpted below), procedure and policy on course types and internships

- How To ... Step-By-Step Guide for Proposers Preparing New and Revised PROGRAM Proposals - reviews required elements and offers a walk-through of the Program Proposal in CIM

How To ... Guide for Proposers Preparing New, Experimental, and Revised COURSE Proposals - the focus of this guide is how to make sure your proposal is addressing the kinds of questions asked by HSCC and APC in their review of course proposals, including course titles, course numbers, course SLOs, the rationale, and more.

For experimental, new, and revised course proposals, you may also want to consult:

- How to add attributes to courses in CIM

- How to write effective SLOs

- APC guidelines and policies on course prerequisites , course descriptions , and syllabi .

Please consult with the HSCC Chair and/or the Associate Dean if you need additional information or guidance.

Below, we excerpt the section from the HSCC Guidelines about how to craft a robust rationale in support of your curriculum proposals. The rationale in CIM is the section most carefully considered by HSCC and APC.

Writing the Rationale for Curriculum Proposals

The rationale is one of the most important elements of a proposal. This is where new curricular additions or modifications are explained and justified. The committees that review these proposals will rarely be in the same or even a related disciplinary area as the proposer, so clarity, accuracy, and concision are key qualities. We suggest you answer or adapt the statements below in your rationale for new or revised proposals.

General principle : while it may be the case that a specific course reflects a faculty member’s particular scholarly expertise, our expectation is that courses being added to the curriculum are supported by the whole department and play a role in the overall curriculum. Therefore, rationales are better phrased in terms of “we” or “the department” rather than “I,” and the justification should be about the role of the course in the curriculum, not the expertise of the faculty colleague. We assume our colleagues are prepared and qualified to teach the courses they offer!

A. New course proposal rationale

The rationale should address the following questions:

- What does the course add to the department’s major and/or minor programs or concentrations in terms of content, skills, or a combination?

- If the course is targeted to a general education audience, what does this add to the broader educational experience of Ithaca College students?

- How are the learning outcomes for the course (which must be specified) aligned with program learning outcomes and consistent with the level of the course?

- If the course is being added in response to program review or SLO assessment – what specifically did the department learn and how would this course address that need?

Remember that the rationale is also the place to explain how the prerequisites or restrictions support students to be successful in the course, and why the course is placed at the level that it is. If the course will be taught with an alternative type of pedagogy to a standard lecture, seminar, studio, or lab course, the rationale is also the place to characterize that, and explain why this pedagogy is appropriate to the course.

If the course was previously an experimental course : The rationale can include information about the success of the course when it was offered, but popularity of a course is not a curricular justification, and so should not be the primary rationale provided. Further, the rationale does not need to address how the course has changed or is changing since it was offered experimentally, but rather should treat the course as a new proposal with the particulars (in terms of course description, prereq, syllabus, etc.) provided.

B. Course revision proposal rationale

For existing courses, it is not necessary to include a detailed history of how the course has been taught in the past. The key task in the revised course rationale is to describe the changes and justify them. In this case, changes may be:

- due to modifications in departmental curricular priorities,

- in response to new developments in professional or academic practice,

- following from program or SLO assessment.

Questions to address include:

- What is being added to or removed from a course?

- Are the learning outcomes changing, and if so, how and why? How does the change to this course impact the major, minor, or general education program?

C. New and revised program (major and minor) proposals rationales

New major and minor programs need to be created before a curriculum proposal can be submitted. The New Program Authorization Proposal, available through CIM, provides the opportunity to propose the creation of a new program. This proposal will be reviewed and approved by the Dean and the Provost before the curriculum proposal can be created in CIM. If you are planning to create a new program, please consult with the Associate Dean before getting started. Once the program has been authorized, you can then prepare the curriculum proposal.

See the How to…. Step-By-Step Guide for Proposers Preparing New and Revised Program Proposals (located in the Curriculum Guides for Faculty folder) for detailed guidance on preparing program proposals in CIM.

New program curriculum rationale

This should include:

- General description of the overall structure of the requirements, and an explanation of how this structure reflects or addresses the goals of the program in terms of learning outcomes, content, and skills.

- Specific discussion of each component of the program requirements, that explains the role each requirement plays — whether a course or set of courses, a set of restricted electives, or a required experience — in supporting students to achieve the learning outcomes expected.

- If using attributes, a discussion of the criteria to be used to determine whether a course meets the intended outcomes associated with the attribute is also expected.

Revised program curriculum rationale

As with revised course proposals, these rationales should describe the changes being made and an explanation for each of them. Program changes may be:

- in response to new developments in professional or academic practice,

- following from program or SLO assessment, or

- in response to School or College-wide guidance.

Questions to address include:

- What is being added to or removed from a program?

- (How) are the program learning outcomes changing?

- How does this change affect the school or college?

- How does the proposed revision respond to School or College-wide guidance while maintaining curricular coherence and disciplinary expectations?

Additional questions for all program proposals include:

- how does the new or revised program contribute to the overall curriculum of H&S and to Ithaca College?

- how does the new or revised program reflect current academic standards, including types of courses offered, sequencing of courses, and assessment procedures?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5 Curriculum Design, Development and Models: Planning for Student Learning

“. . . there is always a need for newly formulated curriculum models that address contemporary circumstance and valued educational aspirations.” –Edmond Short

Introduction

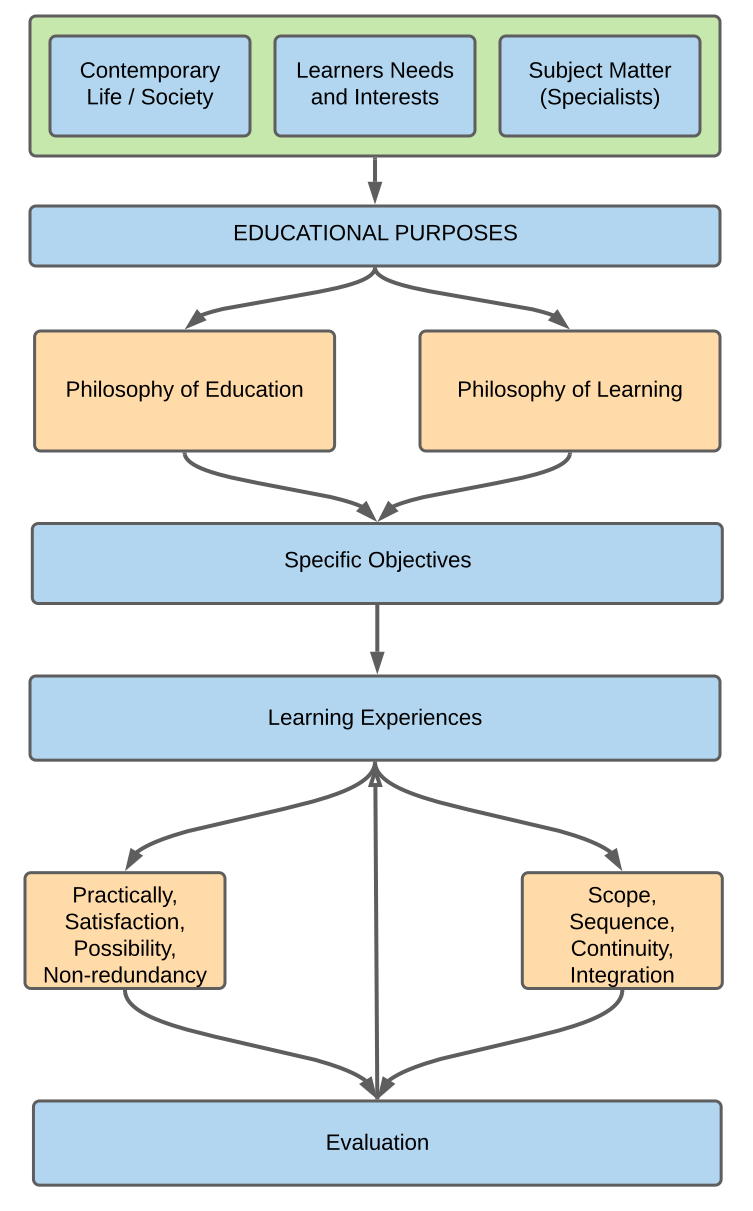

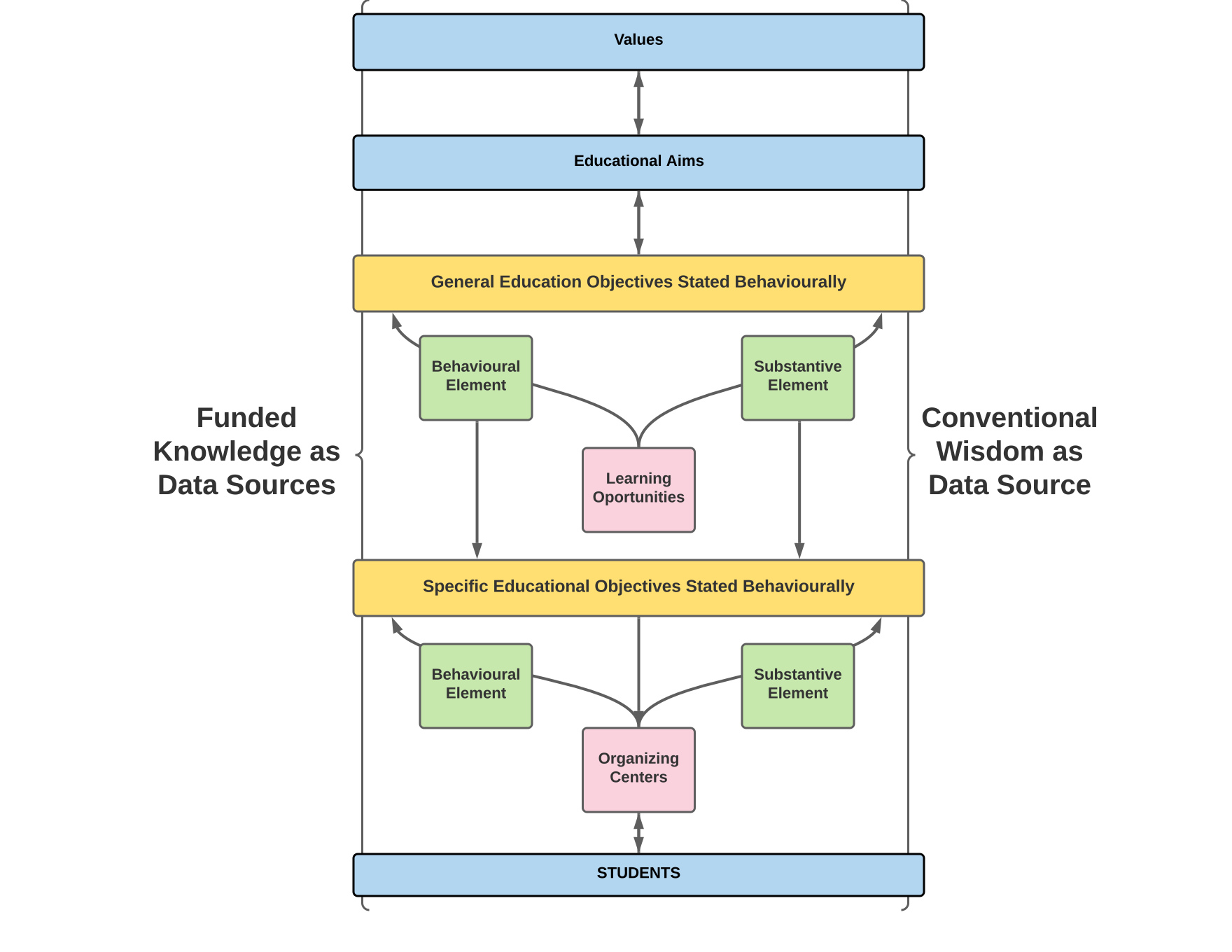

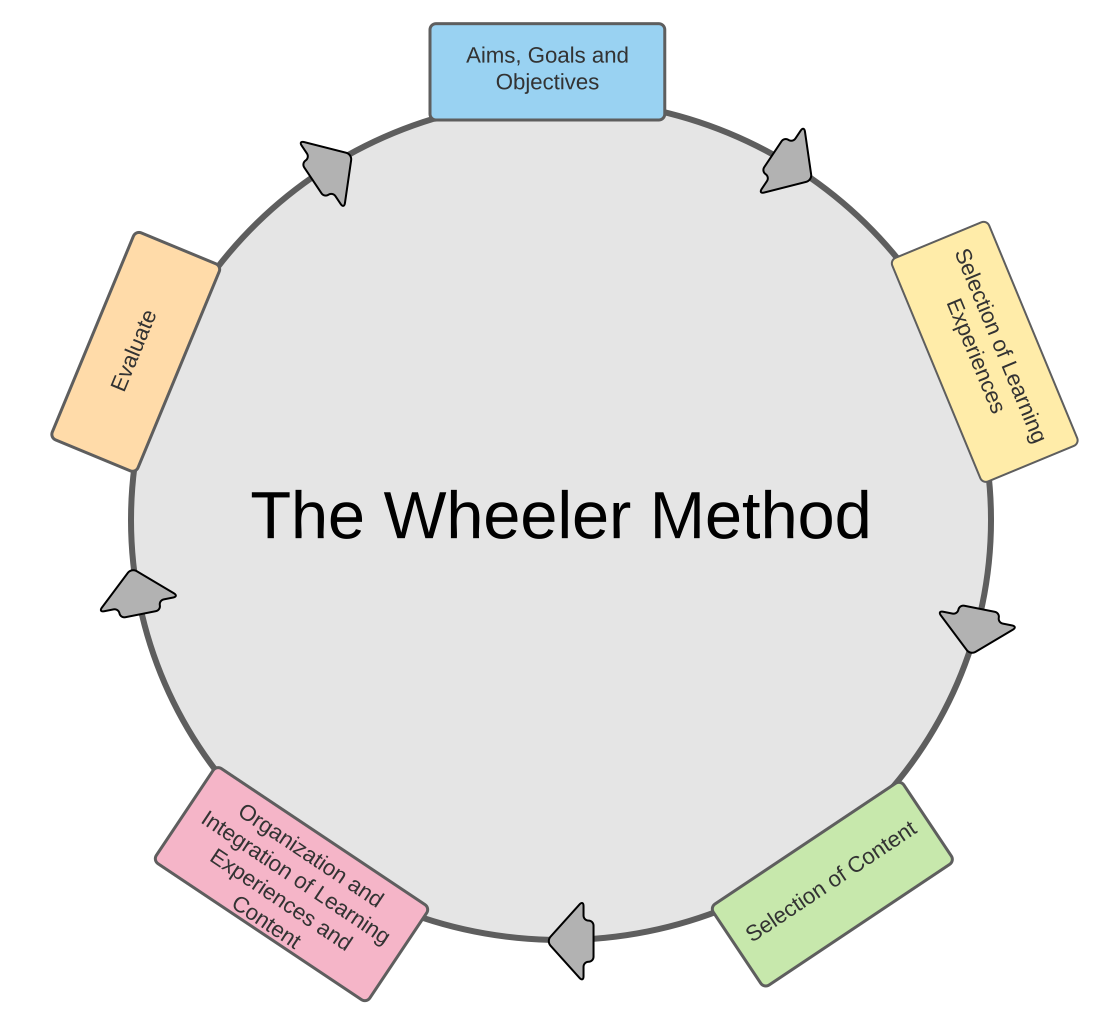

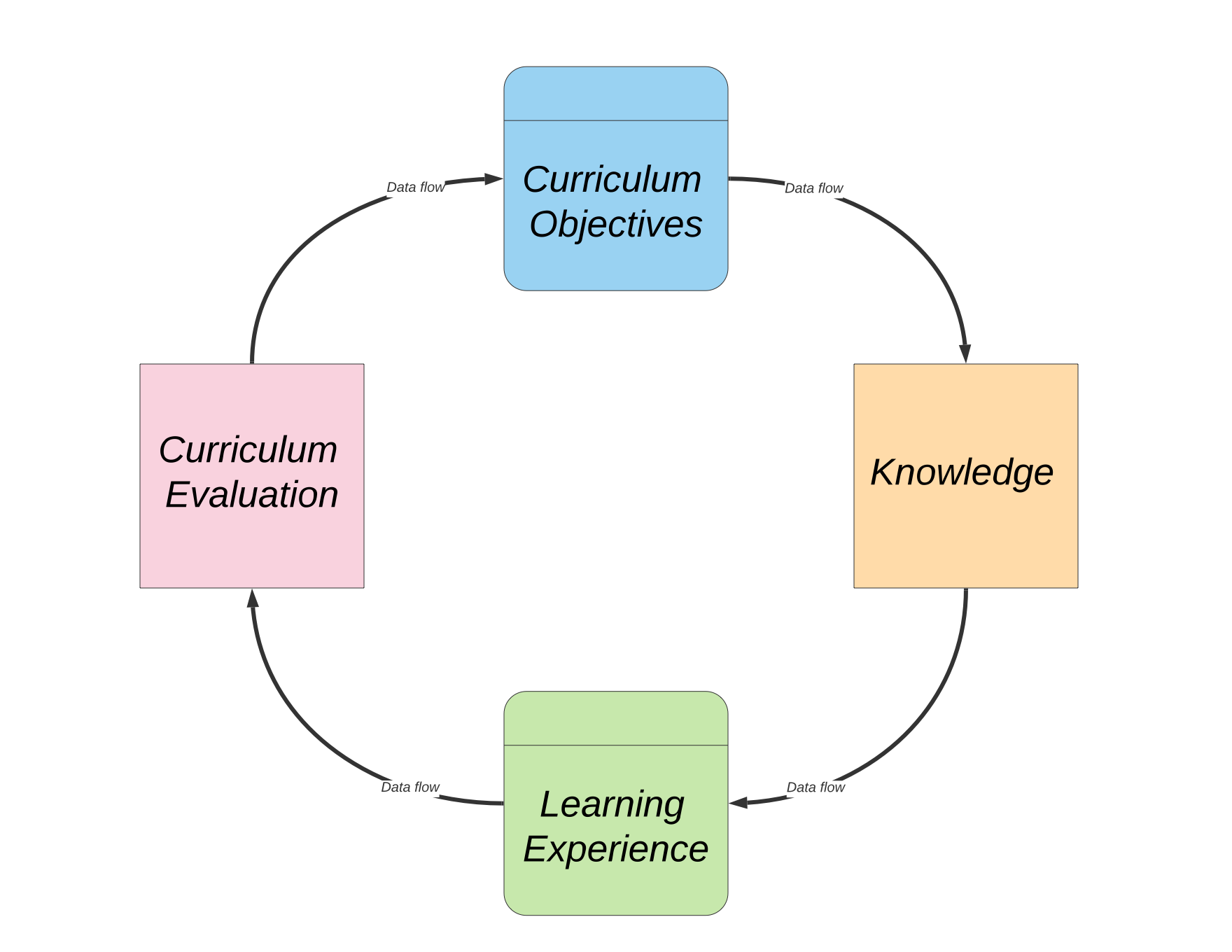

Curriculum design refers to the structure or organization of the curriculum, and curriculum development includes the planning, implementation, and evaluation processes of the curriculum. Curriculum models guide these processes.

Essential Questions

- What is curriculum design?

- What questions did Tyler pose for guiding the curriculum design process?

- What are the major curriculum design models?

- What unique element did Goodlad add to his model?

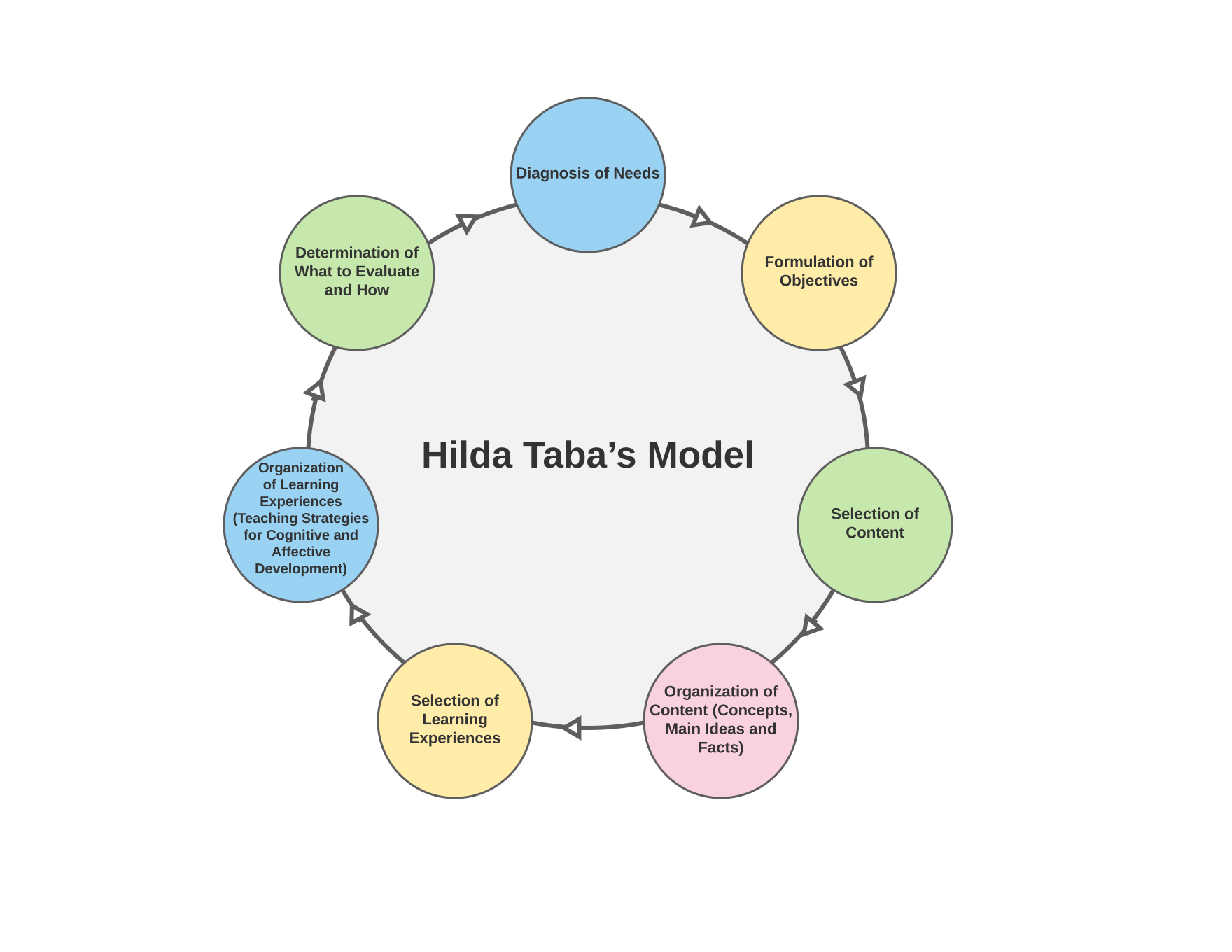

- In addition to the needs of the learner, what did Hilda Taba add to her model?

Meaning of Curriculum Design

From Curriculum Studies, pp. 65-68

Curriculum design is largely concerned with issues such as what to include in the curriculum and how to present it in such a way that the curriculum can be implemented with understanding and success (Barlow et al., 1984). Therefore, curriculum design refers to how the components of the curriculum have been arranged in order to facilitate learning (Shiundu & Omulando, 1992).

Curriculum design is concerned with issues of choosing what the organizational basis or structural framework of the curriculum is. The choice of a design often implies a value position.

As with other curriculum-related concepts, curriculum design has a variety of definitions, depending on the scholars involved. For example, Doll (1992) says that curriculum design is a way of organizing that permits curriculum ideas to function. She also adds that curriculum design refers to the structure or pattern of the organization of the curriculum.

The curriculum design process results in a curriculum document that contains the following:

- a statement of purpose(s),

- an instructional guide that displays behavioral objectives and content organization in harmony with school organization,

- a set of guidelines (or rules) governing the use of the curriculum, and

- an evaluation plan.

Thus, curriculum is designed to fit the organizational pattern of the school/institution for which it is intended.

How a curriculum is conceptualized, organized, developed, and implemented depends on a particular state’s or district’s educational objectives. Whatever design is adopted depends also on the philosophy of education.

There are several ways of designing school curriculum. These include subject-centered, learner-centered, integrated, or broad fields (which combines two or more related subjects into one field of study; e.g., language arts combine the separate but related subjects of reading, writing, speaking, listening, comprehension, and spelling into a core curriculum).

Subject-Centered Curriculum Design

This curriculum design refers to the organization of curriculum in terms of separate subjects, e.g., geography, math, and history, etc. This has been the oldest school curriculum design and the most common in the world. It was even practiced by the ancient Greek educators. The subject-centered design was adapted by many European and African countries as well as states and districts in the United States. An examination of the subject-centered curriculum design shows that it is used mainly in the upper elementary and secondary schools and colleges. Frequently, laypeople, educators, and other professionals who support this design received their schooling or professional training in this type of system. Teachers, for instance, are trained and specialized to teach one or two subjects at the secondary and sometimes the elementary school levels.

There are advantages and disadvantages of this approach to curriculum organization. There are reasons why some educators advocate for it while others criticize this approach.

Advantages of Subject-Centered Curriculum Design

It is possible and desirable to determine in advance what all children will learn in various subjects and grade levels. For instance, curricula for schools in centralized systems of education are generally developed and approved centrally by a governing body in the education body for a given district or state. In the U.S., the state government often oversees this process which is guided by standards.

- It is usually required to set minimum standards of performance and achievement for the knowledge specified in the subject area.

- Almost all textbooks and support materials on the educational market are organized by subject, although the alignment of the text contents and the standards are often open for debate.

- Tradition seems to give this design greater support. People have become familiar and more comfortable with the subject-centered curriculum and view it as part of the system of the school and education as a whole.

- The subject-centered curriculum is better understood by teachers because their training was based on this method, i.e., specialization.

- Advocates of the subject-centered design have argued that the intellectual powers of individual learners can develop through this approach.

- Curriculum planning is easier and simpler in the subject-centered curriculum design.

Disadvantages of Subject-Centered Curriculum Design

Critics of subject-centered curriculum design have strongly advocated a shift from it. These criticisms are based on the following arguments:

- Subject-centered curriculum tends to bring about a high degree of fragmentation of knowledge.

- Subject-centered curriculum lacks integration of content. Learning in most cases tends to be compartmentalized. Subjects or knowledge are broken down into smaller seemingly unrelated bits of information to be learned.

- This design stresses content and tends to neglect the needs, interests, and experiences of the students.

- There has always been an assumption that information learned through the subject-matter curriculum will be transferred for use in everyday life situations. This claim has been questioned by many scholars who argue that the automatic transfer of the information already learned does not always occur.

Given the arguments for and against subject-centered curriculum design, let us consider the learner-centered or personalized curriculum design.

Learner-Centered/Personalized Curriculum Design

Learner-centered curriculum design may take various forms such as individualized or personalized learning. In this design, the curriculum is organized around the needs, interests, abilities, and aspirations of students.

Advocates of the design emphasize that attention is paid to what is known about human growth, development, and learning. Planning this type of curriculum is done along with the students after identifying their varied concerns, interests, and priorities and then developing appropriate topics as per the issues raised.

This type of design requires a lot of resources and manpower to meet a variety of needs. Hence, the design is more commonly used in the U.S. and other western countries, while in the developing world the use is more limited.

To support this approach, Hilda Taba (1962) stated, “Children like best those things that are attached to solving actual problems that help them in meeting real needs or that connect with some active interest. Learning in its true sense is an active transaction.”

Advantages of the Learner-Centered Curriculum Design

- The needs and interests of students are considered in the selection and organization of content.

- Because the needs and interests of students are considered in the planning of students’ work, the resulting curriculum is relevant to the student’s world.

- The design allows students to be active and acquire skills and procedures that apply to the outside world.

Disadvantages of the Learner-Centered Curriculum Design

- The needs and interests of students may not be valid or long lasting. They are often short-lived.

- The interests and needs of students may not reflect specific areas of knowledge that could be essential for successful functioning in society. Quite often, the needs and interests of students have been emphasized and not those that are important for society in general.

- The nature of the education systems and society in many countries may not permit learner-centered curriculum design to be implemented effectively.

- As pointed out earlier, the design is expensive in regard to resources, both human and fiscal, that are needed to satisfy the needs and interests of individual students.