Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

12.1 Creating a Rough Draft for a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Apply strategies for drafting an effective introduction and conclusion.

- Identify when and how to summarize, paraphrase, and directly quote information from research sources.

- Apply guidelines for citing sources within the body of the paper and the bibliography.

- Use primary and secondary research to support ideas.

- Identify the purposes for which writers use each type of research.

At last, you are ready to begin writing the rough draft of your research paper. Putting your thinking and research into words is exciting. It can also be challenging. In this section, you will learn strategies for handling the more challenging aspects of writing a research paper, such as integrating material from your sources, citing information correctly, and avoiding any misuse of your sources.

The Structure of a Research Paper

Research papers generally follow the same basic structure: an introduction that presents the writer’s thesis, a body section that develops the thesis with supporting points and evidence, and a conclusion that revisits the thesis and provides additional insights or suggestions for further research.

Your writing voice will come across most strongly in your introduction and conclusion, as you work to attract your readers’ interest and establish your thesis. These sections usually do not cite sources at length. They focus on the big picture, not specific details. In contrast, the body of your paper will cite sources extensively. As you present your ideas, you will support your points with details from your research.

Writing Your Introduction

There are several approaches to writing an introduction, each of which fulfills the same goals. The introduction should get readers’ attention, provide background information, and present the writer’s thesis. Many writers like to begin with one of the following catchy openers:

- A surprising fact

- A thought-provoking question

- An attention-getting quote

- A brief anecdote that illustrates a larger concept

- A connection between your topic and your readers’ experiences

The next few sentences place the opening in context by presenting background information. From there, the writer builds toward a thesis, which is traditionally placed at the end of the introduction. Think of your thesis as a signpost that lets readers know in what direction the paper is headed.

Jorge decided to begin his research paper by connecting his topic to readers’ daily experiences. Read the first draft of his introduction. The thesis is underlined. Note how Jorge progresses from the opening sentences to background information to his thesis.

Beyond the Hype: Evaluating Low-Carb Diets

I. Introduction

Over the past decade, increasing numbers of Americans have jumped on the low-carb bandwagon. Some studies estimate that approximately 40 million Americans, or about 20 percent of the population, are attempting to restrict their intake of food high in carbohydrates (Sanders and Katz, 2004; Hirsch, 2004). Proponents of low-carb diets say they are not only the most effective way to lose weight, but they also yield health benefits such as lower blood pressure and improved cholesterol levels. Meanwhile, some doctors claim that low-carb diets are overrated and caution that their long-term effects are unknown. Although following a low-carbohydrate diet can benefit some people, these diets are not necessarily the best option for everyone who wants to lose weight or improve their health.

Write the introductory paragraph of your research paper. Try using one of the techniques listed in this section to write an engaging introduction. Be sure to include background information about the topic that leads to your thesis.

Writers often work out of sequence when writing a research paper. If you find yourself struggling to write an engaging introduction, you may wish to write the body of your paper first. Writing the body sections first will help you clarify your main points. Writing the introduction should then be easier. You may have a better sense of how to introduce the paper after you have drafted some or all of the body.

Writing Your Conclusion

In your introduction, you tell readers where they are headed. In your conclusion, you recap where they have been. For this reason, some writers prefer to write their conclusions soon after they have written their introduction. However, this method may not work for all writers. Other writers prefer to write their conclusion at the end of the paper, after writing the body paragraphs. No process is absolutely right or absolutely wrong; find the one that best suits you.

No matter when you compose the conclusion, it should sum up your main ideas and revisit your thesis. The conclusion should not simply echo the introduction or rely on bland summary statements, such as “In this paper, I have demonstrated that.…” In fact, avoid repeating your thesis verbatim from the introduction. Restate it in different words that reflect the new perspective gained through your research. That helps keep your ideas fresh for your readers. An effective writer might conclude a paper by asking a new question the research inspired, revisiting an anecdote presented earlier, or reminding readers of how the topic relates to their lives.

Writing at Work

If your job involves writing or reading scientific papers, it helps to understand how professional researchers use the structure described in this section. A scientific paper begins with an abstract that briefly summarizes the entire paper. The introduction explains the purpose of the research, briefly summarizes previous research, and presents the researchers’ hypothesis. The body provides details about the study, such as who participated in it, what the researchers measured, and what results they recorded. The conclusion presents the researchers’ interpretation of the data, or what they learned.

Using Source Material in Your Paper

One of the challenges of writing a research paper is successfully integrating your ideas with material from your sources. Your paper must explain what you think, or it will read like a disconnected string of facts and quotations. However, you also need to support your ideas with research, or they will seem insubstantial. How do you strike the right balance?

You have already taken a step in the right direction by writing your introduction. The introduction and conclusion function like the frame around a picture. They define and limit your topic and place your research in context.

In the body paragraphs of your paper, you will need to integrate ideas carefully at the paragraph level and at the sentence level. You will use topic sentences in your paragraphs to make sure readers understand the significance of any facts, details, or quotations you cite. You will also include sentences that transition between ideas from your research, either within a paragraph or between paragraphs. At the sentence level, you will need to think carefully about how you introduce paraphrased and quoted material.

Earlier you learned about summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting when taking notes. In the next few sections, you will learn how to use these techniques in the body of your paper to weave in source material to support your ideas.

Summarizing Sources

When you summarize material from a source, you zero in on the main points and restate them concisely in your own words. This technique is appropriate when only the major ideas are relevant to your paper or when you need to simplify complex information into a few key points for your readers.

Be sure to review the source material as you summarize it. Identify the main idea and restate it as concisely as you can—preferably in one sentence. Depending on your purpose, you may also add another sentence or two condensing any important details or examples. Check your summary to make sure it is accurate and complete.

In his draft, Jorge summarized research materials that presented scientists’ findings about low-carbohydrate diets. Read the following passage from a trade magazine article and Jorge’s summary of the article.

Assessing the Efficacy of Low-Carbohydrate Diets

Adrienne Howell, Ph.D.

Over the past few years, a number of clinical studies have explored whether high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets are more effective for weight loss than other frequently recommended diet plans, such as diets that drastically curtail fat intake (Pritikin) or that emphasize consuming lean meats, grains, vegetables, and a moderate amount of unsaturated fats (the Mediterranean diet). A 2009 study found that obese teenagers who followed a low-carbohydrate diet lost an average of 15.6 kilograms over a six-month period, whereas teenagers following a low-fat diet or a Mediterranean diet lost an average of 11.1 kilograms and 9.3 kilograms respectively. Two 2010 studies that measured weight loss for obese adults following these same three diet plans found similar results. Over three months, subjects on the low-carbohydrate diet plan lost anywhere from four to six kilograms more than subjects who followed other diet plans.

In three recent studies, researchers compared outcomes for obese subjects who followed either a low-carbohydrate diet, a low-fat diet, or a Mediterranean diet and found that subjects following a low-carbohydrate diet lost more weight in the same time (Howell, 2010).

A summary restates ideas in your own words—but for specialized or clinical terms, you may need to use terms that appear in the original source. For instance, Jorge used the term obese in his summary because related words such as heavy or overweight have a different clinical meaning.

On a separate sheet of paper, practice summarizing by writing a one-sentence summary of the same passage that Jorge already summarized.

Paraphrasing Sources

When you paraphrase material from a source, restate the information from an entire sentence or passage in your own words, using your own original sentence structure. A paraphrased source differs from a summarized source in that you focus on restating the ideas, not condensing them.

Again, it is important to check your paraphrase against the source material to make sure it is both accurate and original. Inexperienced writers sometimes use the thesaurus method of paraphrasing—that is, they simply rewrite the source material, replacing most of the words with synonyms. This constitutes a misuse of sources. A true paraphrase restates ideas using the writer’s own language and style.

In his draft, Jorge frequently paraphrased details from sources. At times, he needed to rewrite a sentence more than once to ensure he was paraphrasing ideas correctly. Read the passage from a website. Then read Jorge’s initial attempt at paraphrasing it, followed by the final version of his paraphrase.

Dieters nearly always get great results soon after they begin following a low-carbohydrate diet, but these results tend to taper off after the first few months, particularly because many dieters find it difficult to follow a low-carbohydrate diet plan consistently.

People usually see encouraging outcomes shortly after they go on a low-carbohydrate diet, but their progress slows down after a short while, especially because most discover that it is a challenge to adhere to the diet strictly (Heinz, 2009).

After reviewing the paraphrased sentence, Jorge realized he was following the original source too closely. He did not want to quote the full passage verbatim, so he again attempted to restate the idea in his own style.

Because it is hard for dieters to stick to a low-carbohydrate eating plan, the initial success of these diets is short-lived (Heinz, 2009).

On a separate sheet of paper, follow these steps to practice paraphrasing.

- Choose an important idea or detail from your notes.

- Without looking at the original source, restate the idea in your own words.

- Check your paraphrase against the original text in the source. Make sure both your language and your sentence structure are original.

- Revise your paraphrase if necessary.

Quoting Sources Directly

Most of the time, you will summarize or paraphrase source material instead of quoting directly. Doing so shows that you understand your research well enough to write about it confidently in your own words. However, direct quotes can be powerful when used sparingly and with purpose.

Quoting directly can sometimes help you make a point in a colorful way. If an author’s words are especially vivid, memorable, or well phrased, quoting them may help hold your reader’s interest. Direct quotations from an interviewee or an eyewitness may help you personalize an issue for readers. And when you analyze primary sources, such as a historical speech or a work of literature, quoting extensively is often necessary to illustrate your points. These are valid reasons to use quotations.

Less experienced writers, however, sometimes overuse direct quotations in a research paper because it seems easier than paraphrasing. At best, this reduces the effectiveness of the quotations. At worst, it results in a paper that seems haphazardly pasted together from outside sources. Use quotations sparingly for greater impact.

When you do choose to quote directly from a source, follow these guidelines:

- Make sure you have transcribed the original statement accurately.

- Represent the author’s ideas honestly. Quote enough of the original text to reflect the author’s point accurately.

- Never use a stand-alone quotation. Always integrate the quoted material into your own sentence.

- Use ellipses (…) if you need to omit a word or phrase. Use brackets [ ] if you need to replace a word or phrase.

- Make sure any omissions or changed words do not alter the meaning of the original text. Omit or replace words only when absolutely necessary to shorten the text or to make it grammatically correct within your sentence.

- Remember to include correctly formatted citations that follow the assigned style guide.

Jorge interviewed a dietician as part of his research, and he decided to quote her words in his paper. Read an excerpt from the interview and Jorge’s use of it, which follows.

Personally, I don’t really buy into all of the hype about low-carbohydrate miracle diets like Atkins and so on. Sure, for some people, they are great, but for most, any sensible eating and exercise plan would work just as well.

Registered dietician Dana Kwon (2010) admits, “Personally, I don’t really buy into all of the hype.…Sure, for some people, [low-carbohydrate diets] are great, but for most, any sensible eating and exercise plan would work just as well.”

Notice how Jorge smoothly integrated the quoted material by starting the sentence with an introductory phrase. His use of ellipses and brackets did not change the source’s meaning.

Documenting Source Material

Throughout the writing process, be scrupulous about documenting information taken from sources. The purpose of doing so is twofold:

- To give credit to other writers or researchers for their ideas

- To allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired

You will cite sources within the body of your paper and at the end of the paper in your bibliography. For this assignment, you will use the citation format used by the American Psychological Association (also known as APA style). For information on the format used by the Modern Language Association (MLA style), see Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” .

Citing Sources in the Body of Your Paper

In-text citations document your sources within the body of your paper. These include two vital pieces of information: the author’s name and the year the source material was published. When quoting a print source, also include in the citation the page number where the quoted material originally appears. The page number will follow the year in the in-text citation. Page numbers are necessary only when content has been directly quoted, not when it has been summarized or paraphrased.

Within a paragraph, this information may appear as part of your introduction to the material or as a parenthetical citation at the end of a sentence. Read the examples that follow. For more information about in-text citations for other source types, see Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” .

Leibowitz (2008) found that low-carbohydrate diets often helped subjects with Type II diabetes maintain a healthy weight and control blood-sugar levels.

The introduction to the source material includes the author’s name followed by the year of publication in parentheses.

Low-carbohydrate diets often help subjects with Type II diabetes maintain a healthy weight and control blood-sugar levels (Leibowitz, 2008).

The parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence includes the author’s name, a comma, and the year the source was published. The period at the end of the sentence comes after the parentheses.

Creating a List of References

Each of the sources you cite in the body text will appear in a references list at the end of your paper. While in-text citations provide the most basic information about the source, your references section will include additional publication details. In general, you will include the following information:

- The author’s last name followed by his or her first (and sometimes middle) initial

- The year the source was published

- The source title

- For articles in periodicals, the full name of the periodical, along with the volume and issue number and the pages where the article appeared

Additional information may be included for different types of sources, such as online sources. For a detailed guide to APA or MLA citations, see Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” . A sample reference list is provided with the final draft of Jorge’s paper later in this chapter.

Using Primary and Secondary Research

As you write your draft, be mindful of how you are using primary and secondary source material to support your points. Recall that primary sources present firsthand information. Secondary sources are one step removed from primary sources. They present a writer’s analysis or interpretation of primary source materials. How you balance primary and secondary source material in your paper will depend on the topic and assignment.

Using Primary Sources Effectively

Some types of research papers must use primary sources extensively to achieve their purpose. Any paper that analyzes a primary text or presents the writer’s own experimental research falls in this category. Here are a few examples:

- A paper for a literature course analyzing several poems by Emily Dickinson

- A paper for a political science course comparing televised speeches delivered by two presidential candidates

- A paper for a communications course discussing gender biases in television commercials

- A paper for a business administration course that discusses the results of a survey the writer conducted with local businesses to gather information about their work-from-home and flextime policies

- A paper for an elementary education course that discusses the results of an experiment the writer conducted to compare the effectiveness of two different methods of mathematics instruction

For these types of papers, primary research is the main focus. If you are writing about a work (including nonprint works, such as a movie or a painting), it is crucial to gather information and ideas from the original work, rather than relying solely on others’ interpretations. And, of course, if you take the time to design and conduct your own field research, such as a survey, a series of interviews, or an experiment, you will want to discuss it in detail. For example, the interviews may provide interesting responses that you want to share with your reader.

Using Secondary Sources Effectively

For some assignments, it makes sense to rely more on secondary sources than primary sources. If you are not analyzing a text or conducting your own field research, you will need to use secondary sources extensively.

As much as possible, use secondary sources that are closely linked to primary research, such as a journal article presenting the results of the authors’ scientific study or a book that cites interviews and case studies. These sources are more reliable and add more value to your paper than sources that are further removed from primary research. For instance, a popular magazine article on junk-food addiction might be several steps removed from the original scientific study on which it is loosely based. As a result, the article may distort, sensationalize, or misinterpret the scientists’ findings.

Even if your paper is largely based on primary sources, you may use secondary sources to develop your ideas. For instance, an analysis of Alfred Hitchcock’s films would focus on the films themselves as a primary source, but might also cite commentary from critics. A paper that presents an original experiment would include some discussion of similar prior research in the field.

Jorge knew he did not have the time, resources, or experience needed to conduct original experimental research for his paper. Because he was relying on secondary sources to support his ideas, he made a point of citing sources that were not far removed from primary research.

Some sources could be considered primary or secondary sources, depending on the writer’s purpose for using them. For instance, if a writer’s purpose is to inform readers about how the No Child Left Behind legislation has affected elementary education, a Time magazine article on the subject would be a secondary source. However, suppose the writer’s purpose is to analyze how the news media has portrayed the effects of the No Child Left Behind legislation. In that case, articles about the legislation in news magazines like Time , Newsweek , and US News & World Report would be primary sources. They provide firsthand examples of the media coverage the writer is analyzing.

Avoiding Plagiarism

Your research paper presents your thinking about a topic, supported and developed by other people’s ideas and information. It is crucial to always distinguish between the two—as you conduct research, as you plan your paper, and as you write. Failure to do so can lead to plagiarism.

Intentional and Accidental Plagiarism

Plagiarism is the act of misrepresenting someone else’s work as your own. Sometimes a writer plagiarizes work on purpose—for instance, by purchasing an essay from a website and submitting it as original course work. In other cases, a writer may commit accidental plagiarism due to carelessness, haste, or misunderstanding. To avoid unintentional plagiarism, follow these guidelines:

- Understand what types of information must be cited.

- Understand what constitutes fair use of a source.

- Keep source materials and notes carefully organized.

- Follow guidelines for summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting sources.

When to Cite

Any idea or fact taken from an outside source must be cited, in both the body of your paper and the references list. The only exceptions are facts or general statements that are common knowledge. Common-knowledge facts or general statements are commonly supported by and found in multiple sources. For example, a writer would not need to cite the statement that most breads, pastas, and cereals are high in carbohydrates; this is well known and well documented. However, if a writer explained in detail the differences among the chemical structures of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, a citation would be necessary. When in doubt, cite.

In recent years, issues related to the fair use of sources have been prevalent in popular culture. Recording artists, for example, may disagree about the extent to which one has the right to sample another’s music. For academic purposes, however, the guidelines for fair use are reasonably straightforward.

Writers may quote from or paraphrase material from previously published works without formally obtaining the copyright holder’s permission. Fair use means that the writer legitimately uses brief excerpts from source material to support and develop his or her own ideas. For instance, a columnist may excerpt a few sentences from a novel when writing a book review. However, quoting or paraphrasing another’s work at excessive length, to the extent that large sections of the writing are unoriginal, is not fair use.

As he worked on his draft, Jorge was careful to cite his sources correctly and not to rely excessively on any one source. Occasionally, however, he caught himself quoting a source at great length. In those instances, he highlighted the paragraph in question so that he could go back to it later and revise. Read the example, along with Jorge’s revision.

Heinz (2009) found that “subjects in the low-carbohydrate group (30% carbohydrates; 40% protein, 30% fat) had a mean weight loss of 10 kg (22 lbs) over a 4-month period.” These results were “noticeably better than results for subjects on a low-fat diet (45% carbohydrates, 35% protein, 20% fat)” whose average weight loss was only “7 kg (15.4 lbs) in the same period.” From this, it can be concluded that “low-carbohydrate diets obtain more rapid results.” Other researchers agree that “at least in the short term, patients following low-carbohydrate diets enjoy greater success” than those who follow alternative plans (Johnson & Crowe, 2010).

After reviewing the paragraph, Jorge realized that he had drifted into unoriginal writing. Most of the paragraph was taken verbatim from a single article. Although Jorge had enclosed the material in quotation marks, he knew it was not an appropriate way to use the research in his paper.

Low-carbohydrate diets may indeed be superior to other diet plans for short-term weight loss. In a study comparing low-carbohydrate diets and low-fat diets, Heinz (2009) found that subjects who followed a low-carbohydrate plan (30% of total calories) for 4 months lost, on average, about 3 kilograms more than subjects who followed a low-fat diet for the same time. Heinz concluded that these plans yield quick results, an idea supported by a similar study conducted by Johnson and Crowe (2010). What remains to be seen, however, is whether this initial success can be sustained for longer periods.

As Jorge revised the paragraph, he realized he did not need to quote these sources directly. Instead, he paraphrased their most important findings. He also made sure to include a topic sentence stating the main idea of the paragraph and a concluding sentence that transitioned to the next major topic in his essay.

Working with Sources Carefully

Disorganization and carelessness sometimes lead to plagiarism. For instance, a writer may be unable to provide a complete, accurate citation if he didn’t record bibliographical information. A writer may cut and paste a passage from a website into her paper and later forget where the material came from. A writer who procrastinates may rush through a draft, which easily leads to sloppy paraphrasing and inaccurate quotations. Any of these actions can create the appearance of plagiarism and lead to negative consequences.

Carefully organizing your time and notes is the best guard against these forms of plagiarism. Maintain a detailed working bibliography and thorough notes throughout the research process. Check original sources again to clear up any uncertainties. Allow plenty of time for writing your draft so there is no temptation to cut corners.

Citing other people’s work appropriately is just as important in the workplace as it is in school. If you need to consult outside sources to research a document you are creating, follow the general guidelines already discussed, as well as any industry-specific citation guidelines. For more extensive use of others’ work—for instance, requesting permission to link to another company’s website on your own corporate website—always follow your employer’s established procedures.

Academic Integrity

The concepts and strategies discussed in this section of Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” connect to a larger issue—academic integrity. You maintain your integrity as a member of an academic community by representing your work and others’ work honestly and by using other people’s work only in legitimately accepted ways. It is a point of honor taken seriously in every academic discipline and career field.

Academic integrity violations have serious educational and professional consequences. Even when cheating and plagiarism go undetected, they still result in a student’s failure to learn necessary research and writing skills. Students who are found guilty of academic integrity violations face consequences ranging from a failing grade to expulsion from the university. Employees may be fired for plagiarism and do irreparable damage to their professional reputation. In short, it is never worth the risk.

Key Takeaways

- An effective research paper focuses on the writer’s ideas. The introduction and conclusion present and revisit the writer’s thesis. The body of the paper develops the thesis and related points with information from research.

- Ideas and information taken from outside sources must be cited in the body of the paper and in the references section.

- Material taken from sources should be used to develop the writer’s ideas. Summarizing and paraphrasing are usually most effective for this purpose.

- A summary concisely restates the main ideas of a source in the writer’s own words.

- A paraphrase restates ideas from a source using the writer’s own words and sentence structures.

- Direct quotations should be used sparingly. Ellipses and brackets must be used to indicate words that were omitted or changed for conciseness or grammatical correctness.

- Always represent material from outside sources accurately.

- Plagiarism has serious academic and professional consequences. To avoid accidental plagiarism, keep research materials organized, understand guidelines for fair use and appropriate citation of sources, and review the paper to make sure these guidelines are followed.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter 12: synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods.

Joanne E McKenzie, Sue E Brennan

Key Points:

- Meta-analysis of effect estimates has many advantages, but other synthesis methods may need to be considered in the circumstance where there is incompletely reported data in the primary studies.

- Alternative synthesis methods differ in the completeness of the data they require, the hypotheses they address, and the conclusions and recommendations that can be drawn from their findings.

- These methods provide more limited information for healthcare decision making than meta-analysis, but may be superior to a narrative description where some results are privileged above others without appropriate justification.

- Tabulation and visual display of the results should always be presented alongside any synthesis, and are especially important for transparent reporting in reviews without meta-analysis.

- Alternative synthesis and visual display methods should be planned and specified in the protocol. When writing the review, details of the synthesis methods should be described.

- Synthesis methods that involve vote counting based on statistical significance have serious limitations and are unacceptable.

Cite this chapter as: McKenzie JE, Brennan SE. Chapter 12: Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

12.1 Why a meta-analysis of effect estimates may not be possible

Meta-analysis of effect estimates has many potential advantages (see Chapter 10 and Chapter 11 ). However, there are circumstances where it may not be possible to undertake a meta-analysis and other statistical synthesis methods may be considered (McKenzie and Brennan 2014).

Some common reasons why it may not be possible to undertake a meta-analysis are outlined in Table 12.1.a . Legitimate reasons include limited evidence; incompletely reported outcome/effect estimates, or different effect measures used across studies; and bias in the evidence. Other commonly cited reasons for not using meta-analysis are because of too much clinical or methodological diversity, or statistical heterogeneity (Achana et al 2014). However, meta-analysis methods should be considered in these circumstances, as they may provide important insights if undertaken and interpreted appropriately.

Table 12.1.a Scenarios that may preclude meta-analysis, with possible solutions

12.2 Statistical synthesis when meta-analysis of effect estimates is not possible

A range of statistical synthesis methods are available, and these may be divided into three categories based on their preferability ( Table 12.2.a ). Preferable methods are the meta-analysis methods outlined in Chapter 10 and Chapter 11 , and are not discussed in detail here. This chapter focuses on methods that might be considered when a meta-analysis of effect estimates is not possible due to incompletely reported data in the primary studies. These methods divide into those that are ‘acceptable’ and ‘unacceptable’. The ‘acceptable’ methods differ in the data they require, the hypotheses they address, limitations around their use, and the conclusions and recommendations that can be drawn (see Section 12.2.1 ). The ‘unacceptable’ methods in common use are described (see Section 12.2.2 ), along with the reasons for why they are problematic.

Compared with meta-analysis methods, the ‘acceptable’ synthesis methods provide more limited information for healthcare decision making. However, these ‘acceptable’ methods may be superior to a narrative that describes results study by study, which comes with the risk that some studies or findings are privileged above others without appropriate justification. Further, in reviews with little or no synthesis, readers are left to make sense of the research themselves, which may result in the use of seemingly simple yet problematic synthesis methods such as vote counting based on statistical significance (see Section 12.2.2.1 ).

All methods first involve calculation of a ‘standardized metric’, followed by application of a synthesis method. In applying any of the following synthesis methods, it is important that only one outcome per study (or other independent unit, for example one comparison from a trial with multiple intervention groups) contributes to the synthesis. Chapter 9 outlines approaches for selecting an outcome when multiple have been measured. Similar to meta-analysis, sensitivity analyses can be undertaken to examine if the findings of the synthesis are robust to potentially influential decisions (see Chapter 10, Section 10.14 and Section 12.4 for examples).

Authors should report the specific methods used in lieu of meta-analysis (including approaches used for presentation and visual display), rather than stating that they have conducted a ‘narrative synthesis’ or ‘narrative summary’ without elaboration. The limitations of the chosen methods must be described, and conclusions worded with appropriate caution. The aim of reporting this detail is to make the synthesis process more transparent and reproducible, and help ensure use of appropriate methods and interpretation.

Table 12.2.a Summary of preferable and acceptable synthesis methods

12.2.1 Acceptable synthesis methods

12.2.1.1 summarizing effect estimates.

Description of method Summarizing effect estimates might be considered in the circumstance where estimates of intervention effect are available (or can be calculated), but the variances of the effects are not reported or are incorrect (and cannot be calculated from other statistics, or reasonably imputed) (Grimshaw et al 2003). Incorrect calculation of variances arises more commonly in non-standard study designs that involve clustering or matching ( Chapter 23 ). While missing variances may limit the possibility of meta-analysis, the (standardized) effects can be summarized using descriptive statistics such as the median, interquartile range, and the range. Calculating these statistics addresses the question ‘What is the range and distribution of observed effects?’

Reporting of methods and results The statistics that will be used to summarize the effects (e.g. median, interquartile range) should be reported. Box-and-whisker or bubble plots will complement reporting of the summary statistics by providing a visual display of the distribution of observed effects (Section 12.3.3 ). Tabulation of the available effect estimates will provide transparency for readers by linking the effects to the studies (Section 12.3.1 ). Limitations of the method should be acknowledged ( Table 12.2.a ).

12.2.1.2 Combining P values

Description of method Combining P values can be considered in the circumstance where there is no, or minimal, information reported beyond P values and the direction of effect; the types of outcomes and statistical tests differ across the studies; or results from non-parametric tests are reported (Borenstein et al 2009). Combining P values addresses the question ‘Is there evidence that there is an effect in at least one study?’ There are several methods available (Loughin 2004), with the method proposed by Fisher outlined here (Becker 1994).

Fisher’s method combines the P values from statistical tests across k studies using the formula:

One-sided P values are used, since these contain information about the direction of effect. However, these P values must reflect the same directional hypothesis (e.g. all testing if intervention A is more effective than intervention B). This is analogous to standardizing the direction of effects before undertaking a meta-analysis. Two-sided P values, which do not contain information about the direction, must first be converted to one-sided P values. If the effect is consistent with the directional hypothesis (e.g. intervention A is beneficial compared with B), then the one-sided P value is calculated as

In studies that do not report an exact P value but report a conventional level of significance (e.g. P<0.05), a conservative option is to use the threshold (e.g. 0.05). The P values must have been computed from statistical tests that appropriately account for the features of the design, such as clustering or matching, otherwise they will likely be incorrect.

Reporting of methods and results There are several methods for combining P values (Loughin 2004), so the chosen method should be reported, along with details of sensitivity analyses that examine if the results are sensitive to the choice of method. The results from the test should be reported alongside any available effect estimates (either individual results or meta-analysis results of a subset of studies) using text, tabulation and appropriate visual displays (Section 12.3 ). The albatross plot is likely to complement the analysis (Section 12.3.4 ). Limitations of the method should be acknowledged ( Table 12.2.a ).

12.2.1.3 Vote counting based on the direction of effect

Description of method Vote counting based on the direction of effect might be considered in the circumstance where the direction of effect is reported (with no further information), or there is no consistent effect measure or data reported across studies. The essence of vote counting is to compare the number of effects showing benefit to the number of effects showing harm for a particular outcome. However, there is wide variation in the implementation of the method due to differences in how ‘benefit’ and ‘harm’ are defined. Rules based on subjective decisions or statistical significance are problematic and should be avoided (see Section 12.2.2 ).

To undertake vote counting properly, each effect estimate is first categorized as showing benefit or harm based on the observed direction of effect alone, thereby creating a standardized binary metric. A count of the number of effects showing benefit is then compared with the number showing harm. Neither statistical significance nor the size of the effect are considered in the categorization. A sign test can be used to answer the question ‘is there any evidence of an effect?’ If there is no effect, the study effects will be distributed evenly around the null hypothesis of no difference. This is equivalent to testing if the true proportion of effects favouring the intervention (or comparator) is equal to 0.5 (Bushman and Wang 2009) (see Section 12.4.2.3 for guidance on implementing the sign test). An estimate of the proportion of effects favouring the intervention can be calculated ( p = u / n , where u = number of effects favouring the intervention, and n = number of studies) along with a confidence interval (e.g. using the Wilson or Jeffreys interval methods (Brown et al 2001)). Unless there are many studies contributing effects to the analysis, there will be large uncertainty in this estimated proportion.

Reporting of methods and results The vote counting method should be reported in the ‘Data synthesis’ section of the review. Failure to recognize vote counting as a synthesis method has led to it being applied informally (and perhaps unintentionally) to summarize results (e.g. through the use of wording such as ‘3 of 10 studies showed improvement in the outcome with intervention compared to control’; ‘most studies found’; ‘the majority of studies’; ‘few studies’ etc). In such instances, the method is rarely reported, and it may not be possible to determine whether an unacceptable (invalid) rule has been used to define benefit and harm (Section 12.2.2 ). The results from vote counting should be reported alongside any available effect estimates (either individual results or meta-analysis results of a subset of studies) using text, tabulation and appropriate visual displays (Section 12.3 ). The number of studies contributing to a synthesis based on vote counting may be larger than a meta-analysis, because only minimal statistical information (i.e. direction of effect) is required from each study to vote count. Vote counting results are used to derive the harvest and effect direction plots, although often using unacceptable methods of vote counting (see Section 12.3.5 ). Limitations of the method should be acknowledged ( Table 12.2.a ).

12.2.2 Unacceptable synthesis methods

12.2.2.1 vote counting based on statistical significance.

Conventional forms of vote counting use rules based on statistical significance and direction to categorize effects. For example, effects may be categorized into three groups: those that favour the intervention and are statistically significant (based on some predefined P value), those that favour the comparator and are statistically significant, and those that are statistically non-significant (Hedges and Vevea 1998). In a simpler formulation, effects may be categorized into two groups: those that favour the intervention and are statistically significant, and all others (Friedman 2001). Regardless of the specific formulation, when based on statistical significance, all have serious limitations and can lead to the wrong conclusion.

The conventional vote counting method fails because underpowered studies that do not rule out clinically important effects are counted as not showing benefit. Suppose, for example, the effect sizes estimated in two studies were identical. However, only one of the studies was adequately powered, and the effect in this study was statistically significant. Only this one effect (of the two identical effects) would be counted as showing ‘benefit’. Paradoxically, Hedges and Vevea showed that as the number of studies increases, the power of conventional vote counting tends to zero, except with large studies and at least moderate intervention effects (Hedges and Vevea 1998). Further, conventional vote counting suffers the same disadvantages as vote counting based on direction of effect, namely, that it does not provide information on the magnitude of effects and does not account for differences in the relative sizes of the studies.

12.2.2.2 Vote counting based on subjective rules

Subjective rules, involving a combination of direction, statistical significance and magnitude of effect, are sometimes used to categorize effects. For example, in a review examining the effectiveness of interventions for teaching quality improvement to clinicians, the authors categorized results as ‘beneficial effects’, ‘no effects’ or ‘detrimental effects’ (Boonyasai et al 2007). Categorization was based on direction of effect and statistical significance (using a predefined P value of 0.05) when available. If statistical significance was not reported, effects greater than 10% were categorized as ‘beneficial’ or ‘detrimental’, depending on their direction. These subjective rules often vary in the elements, cut-offs and algorithms used to categorize effects, and while detailed descriptions of the rules may provide a veneer of legitimacy, such rules have poor performance validity (Ioannidis et al 2008).

A further problem occurs when the rules are not described in sufficient detail for the results to be reproduced (e.g. ter Wee et al 2012, Thornicroft et al 2016). This lack of transparency does not allow determination of whether an acceptable or unacceptable vote counting method has been used (Valentine et al 2010).

12.3 Visual display and presentation of the data

Visual display and presentation of data is especially important for transparent reporting in reviews without meta-analysis, and should be considered irrespective of whether synthesis is undertaken (see Table 12.2.a for a summary of plots associated with each synthesis method). Tables and plots structure information to show patterns in the data and convey detailed information more efficiently than text. This aids interpretation and helps readers assess the veracity of the review findings.

12.3.1 Structured tabulation of results across studies

Ordering studies alphabetically by study ID is the simplest approach to tabulation; however, more information can be conveyed when studies are grouped in subpanels or ordered by a characteristic important for interpreting findings. The grouping of studies in tables should generally follow the structure of the synthesis presented in the text, which should closely reflect the review questions. This grouping should help readers identify the data on which findings are based and verify the review authors’ interpretation.

If the purpose of the table is comparative, grouping studies by any of following characteristics might be informative:

- comparisons considered in the review, or outcome domains (according to the structure of the synthesis);

- study characteristics that may reveal patterns in the data, for example potential effect modifiers including population subgroups, settings or intervention components.

If the purpose of the table is complete and transparent reporting of data, then ordering the studies to increase the prominence of the most relevant and trustworthy evidence should be considered. Possibilities include:

- certainty of the evidence (synthesized result or individual studies if no synthesis);

- risk of bias, study size or study design characteristics; and

- characteristics that determine how directly a study addresses the review question, for example relevance and validity of the outcome measures.

One disadvantage of grouping by study characteristics is that it can be harder to locate specific studies than when tables are ordered by study ID alone, for example when cross-referencing between the text and tables. Ordering by study ID within categories may partly address this.

The value of standardizing intervention and outcome labels is discussed in Chapter 3, Section 3.2.2 and Section 3.2.4 ), while the importance and methods for standardizing effect estimates is described in Chapter 6 . These practices can aid readers’ interpretation of tabulated data, especially when the purpose of a table is comparative.

12.3.2 Forest plots

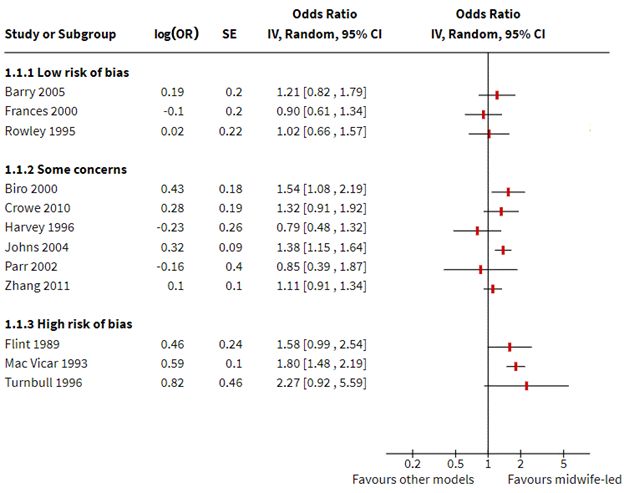

Forest plots and methods for preparing them are described elsewhere ( Chapter 10, Section 10.2 ). Some mention is warranted here of their importance for displaying study results when meta-analysis is not undertaken (i.e. without the summary diamond). Forest plots can aid interpretation of individual study results and convey overall patterns in the data, especially when studies are ordered by a characteristic important for interpreting results (e.g. dose and effect size, sample size). Similarly, grouping studies in subpanels based on characteristics thought to modify effects, such as population subgroups, variants of an intervention, or risk of bias, may help explore and explain differences across studies (Schriger et al 2010). These approaches to ordering provide important techniques for informally exploring heterogeneity in reviews without meta-analysis, and should be considered in preference to alphabetical ordering by study ID alone (Schriger et al 2010).

12.3.3 Box-and-whisker plots and bubble plots

Box-and-whisker plots (see Figure 12.4.a , Panel A) provide a visual display of the distribution of effect estimates (Section 12.2.1.1 ). The plot conventionally depicts five values. The upper and lower limits (or ‘hinges’) of the box, represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The line within the box represents the 50th percentile (median), and the whiskers represent the extreme values (McGill et al 1978). Multiple box plots can be juxtaposed, providing a visual comparison of the distributions of effect estimates (Schriger et al 2006). For example, in a review examining the effects of audit and feedback on professional practice, the format of the feedback (verbal, written, both verbal and written) was hypothesized to be an effect modifier (Ivers et al 2012). Box-and-whisker plots of the risk differences were presented separately by the format of feedback, to allow visual comparison of the impact of format on the distribution of effects. When presenting multiple box-and-whisker plots, the width of the box can be varied to indicate the number of studies contributing to each. The plot’s common usage facilitates rapid and correct interpretation by readers (Schriger et al 2010). The individual studies contributing to the plot are not identified (as in a forest plot), however, and the plot is not appropriate when there are few studies (Schriger et al 2006).

A bubble plot (see Figure 12.4.a , Panel B) can also be used to provide a visual display of the distribution of effects, and is more suited than the box-and-whisker plot when there are few studies (Schriger et al 2006). The plot is a scatter plot that can display multiple dimensions through the location, size and colour of the bubbles. In a review examining the effects of educational outreach visits on professional practice, a bubble plot was used to examine visually whether the distribution of effects was modified by the targeted behaviour (O’Brien et al 2007). Each bubble represented the effect size (y-axis) and whether the study targeted a prescribing or other behaviour (x-axis). The size of the bubbles reflected the number of study participants. However, different formulations of the bubble plot can display other characteristics of the data (e.g. precision, risk-of-bias assessments).

12.3.4 Albatross plot

The albatross plot (see Figure 12.4.a , Panel C) allows approximate examination of the underlying intervention effect sizes where there is minimal reporting of results within studies (Harrison et al 2017). The plot only requires a two-sided P value, sample size and direction of effect (or equivalently, a one-sided P value and a sample size) for each result. The plot is a scatter plot of the study sample sizes against two-sided P values, where the results are separated by the direction of effect. Superimposed on the plot are ‘effect size contours’ (inspiring the plot’s name). These contours are specific to the type of data (e.g. continuous, binary) and statistical methods used to calculate the P values. The contours allow interpretation of the approximate effect sizes of the studies, which would otherwise not be possible due to the limited reporting of the results. Characteristics of studies (e.g. type of study design) can be identified using different colours or symbols, allowing informal comparison of subgroups.

The plot is likely to be more inclusive of the available studies than meta-analysis, because of its minimal data requirements. However, the plot should complement the results from a statistical synthesis, ideally a meta-analysis of available effects.

12.3.5 Harvest and effect direction plots

Harvest plots (see Figure 12.4.a , Panel D) provide a visual extension of vote counting results (Ogilvie et al 2008). In the plot, studies based on the categorization of their effects (e.g. ‘beneficial effects’, ‘no effects’ or ‘detrimental effects’) are grouped together. Each study is represented by a bar positioned according to its categorization. The bars can be ‘visually weighted’ (by height or width) and annotated to highlight study and outcome characteristics (e.g. risk-of-bias domains, proximal or distal outcomes, study design, sample size) (Ogilvie et al 2008, Crowther et al 2011). Annotation can also be used to identify the studies. A series of plots may be combined in a matrix that displays, for example, the vote counting results from different interventions or outcome domains.

The methods papers describing harvest plots have employed vote counting based on statistical significance (Ogilvie et al 2008, Crowther et al 2011). For the reasons outlined in Section 12.2.2.1 , this can be misleading. However, an acceptable approach would be to display the results based on direction of effect.

The effect direction plot is similar in concept to the harvest plot in the sense that both display information on the direction of effects (Thomson and Thomas 2013). In the first version of the effect direction plot, the direction of effects for each outcome within a single study are displayed, while the second version displays the direction of the effects for outcome domains across studies . In this second version, an algorithm is first applied to ‘synthesize’ the directions of effect for all outcomes within a domain (e.g. outcomes ‘sleep disturbed by wheeze’, ‘wheeze limits speech’, ‘wheeze during exercise’ in the outcome domain ‘respiratory’). This algorithm is based on the proportion of effects that are in a consistent direction and statistical significance. Arrows are used to indicate the reported direction of effect (for either outcomes or outcome domains). Features such as statistical significance, study design and sample size are denoted using size and colour. While this version of the plot conveys a large amount of information, it requires further development before its use can be recommended since the algorithm underlying the plot is likely to have poor performance validity.

12.4 Worked example

The example that follows uses four scenarios to illustrate methods for presentation and synthesis when meta-analysis is not possible. The first scenario contrasts a common approach to tabulation with alternative presentations that may enhance the transparency of reporting and interpretation of findings. Subsequent scenarios show the application of the synthesis approaches outlined in preceding sections of the chapter. Box 12.4.a summarizes the review comparisons and outcomes, and decisions taken by the review authors in planning their synthesis. While the example is loosely based on an actual review, the review description, scenarios and data are fabricated for illustration.

Box 12.4.a The review

12.4.1 Scenario 1: structured reporting of effects

We first address a scenario in which review authors have decided that the tools used to measure satisfaction measured concepts that were too dissimilar across studies for synthesis to be appropriate. Setting aside three of the 15 studies that reported on the birth partner’s satisfaction with care, a structured summary of effects is sought of the remaining 12 studies. To keep the example table short, only one outcome is shown per study for each of the measurement periods (antenatal, intrapartum or postpartum).

Table 12.4.a depicts a common yet suboptimal approach to presenting results. Note two features.

- Studies are ordered by study ID, rather than grouped by characteristics that might enhance interpretation (e.g. risk of bias, study size, validity of the measures, certainty of the evidence (GRADE)).

- Data reported are as extracted from each study; effect estimates were not calculated by the review authors and, where reported, were not standardized across studies (although data were available to do both).

Table 12.4.b shows an improved presentation of the same results. In line with best practice, here effect estimates have been calculated by the review authors for all outcomes, and a common metric computed to aid interpretation (in this case an odds ratio; see Chapter 6 for guidance on conversion of statistics to the desired format). Redundant information has been removed (‘statistical test’ and ‘P value’ columns). The studies have been re-ordered, first to group outcomes by period of care (intrapartum outcomes are shown here), and then by risk of bias. This re-ordering serves two purposes. Grouping by period of care aligns with the plan to consider outcomes for each period separately and ensures the table structure matches the order in which results are described in the text. Re-ordering by risk of bias increases the prominence of studies at lowest risk of bias, focusing attention on the results that should most influence conclusions. Had the review authors determined that a synthesis would be informative, then ordering to facilitate comparison across studies would be appropriate; for example, ordering by the type of satisfaction outcome (as pre-defined in the protocol, starting with global measures of satisfaction), or the comparisons made in the studies.

The results may also be presented in a forest plot, as shown in Figure 12.4.b . In both the table and figure, studies are grouped by risk of bias to focus attention on the most trustworthy evidence. The pattern of effects across studies is immediately apparent in Figure 12.4.b and can be described efficiently without having to interpret each estimate (e.g. difference between studies at low and high risk of bias emerge), although these results should be interpreted with caution in the absence of a formal test for subgroup differences (see Chapter 10, Section 10.11 ). Only outcomes measured during the intrapartum period are displayed, although outcomes from other periods could be added, maximizing the information conveyed.

An example description of the results from Scenario 1 is provided in Box 12.4.b . It shows that describing results study by study becomes unwieldy with more than a few studies, highlighting the importance of tables and plots. It also brings into focus the risk of presenting results without any synthesis, since it seems likely that the reader will try to make sense of the results by drawing inferences across studies. Since a synthesis was considered inappropriate, GRADE was applied to individual studies and then used to prioritize the reporting of results, focusing attention on the most relevant and trustworthy evidence. An alternative might be to report results at low risk of bias, an approach analogous to limiting a meta-analysis to studies at low risk of bias. Where possible, these and other approaches to prioritizing (or ordering) results from individual studies in text and tables should be pre-specified at the protocol stage.

Table 12.4.a Scenario 1: table ordered by study ID, data as reported by study authors

* All scales operate in the same direction; higher scores indicate greater satisfaction. CI = confidence interval; MD = mean difference; OR = odds ratio; POR = proportional odds ratio; RD = risk difference; RR = risk ratio.

Table 12.4.b Scenario 1: intrapartum outcome table ordered by risk of bias, standardized effect estimates calculated for all studies

* Outcomes operate in the same direction. A higher score, or an event, indicates greater satisfaction. ** Mean difference calculated for studies reporting continuous outcomes. † For binary outcomes, odds ratios were calculated from the reported summary statistics or were directly extracted from the study. For continuous outcomes, standardized mean differences were calculated and converted to odds ratios (see Chapter 6 ). CI = confidence interval; POR = proportional odds ratio.

Figure 12.4.b Forest plot depicting standardized effect estimates (odds ratios) for satisfaction

Box 12.4.b How to describe the results from this structured summary

12.4.2 Overview of scenarios 2–4: synthesis approaches

We now address three scenarios in which review authors have decided that the outcomes reported in the 15 studies all broadly reflect satisfaction with care. While the measures were quite diverse, a synthesis is sought to help decision makers understand whether women and their birth partners were generally more satisfied with the care received in midwife-led continuity models compared with other models. The three scenarios differ according to the data available (see Table 12.4.c ), with each reflecting progressively less complete reporting of the effect estimates. The data available determine the synthesis method that can be applied.

- Scenario 2: effect estimates available without measures of precision (illustrating synthesis of summary statistics).

- Scenario 3: P values available (illustrating synthesis of P values).

- Scenario 4: directions of effect available (illustrating synthesis using vote-counting based on direction of effect).

For studies that reported multiple satisfaction outcomes, one result is selected for synthesis using the decision rules in Box 12.4.a (point 2).

Table 12.4.c Scenarios 2, 3 and 4: available data for the selected outcome from each study

* All scales operate in the same direction. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction. ** For a particular scenario, the ‘available data’ column indicates the data that were directly reported, or were calculated from the reported statistics, in terms of: effect estimate, direction of effect, confidence interval, precise P value, or statement regarding statistical significance (either statistically significant, or not). CI = confidence interval; direction = direction of effect reported or can be calculated; MD = mean difference; NS = not statistically significant; OR = odds ratio; RD = risk difference; RoB = risk of bias; RR = risk ratio; sig. = statistically significant; SMD = standardized mean difference; Stand. = standardized.

12.4.2.1 Scenario 2: summarizing effect estimates

In Scenario 2, effect estimates are available for all outcomes. However, for most studies, a measure of variance is not reported, or cannot be calculated from the available data. We illustrate how the effect estimates may be summarized using descriptive statistics. In this scenario, it is possible to calculate odds ratios for all studies. For the continuous outcomes, this involves first calculating a standardized mean difference, and then converting this to an odds ratio ( Chapter 10, Section 10.6 ). The median odds ratio is 1.32 with an interquartile range of 1.02 to 1.53 (15 studies). Box-and-whisker plots may be used to display these results and examine informally whether the distribution of effects differs by the overall risk-of-bias assessment ( Figure 12.4.a , Panel A). However, because there are relatively few effects, a reasonable alternative would be to present bubble plots ( Figure 12.4.a , Panel B).

An example description of the results from the synthesis is provided in Box 12.4.c .

Box 12.4.c How to describe the results from this synthesis

12.4.2.2 Scenario 3: combining P values

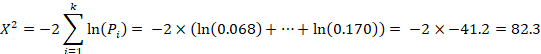

In Scenario 3, there is minimal reporting of the data, and the type of data and statistical methods and tests vary. However, 11 of the 15 studies provide a precise P value and direction of effect, and a further two report a P value less than a threshold (<0.001) and direction. We use this scenario to illustrate a synthesis of P values. Since the reported P values are two-sided ( Table 12.4.c , column 6), they must first be converted to one-sided P values, which incorporate the direction of effect ( Table 12.4.c , column 7).

Fisher’s method for combining P values involved calculating the following statistic:

The combination of P values suggests there is strong evidence of benefit of midwife-led models of care in at least one study (P < 0.001 from a Chi 2 test, 13 studies). Restricting this analysis to those studies judged to be at an overall low risk of bias (sensitivity analysis), there is no longer evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no benefit of midwife-led model of care in any studies (P = 0.314, 3 studies). For the five studies reporting continuous satisfaction outcomes, sufficient data (precise P value, direction, total sample size) are reported to construct an albatross plot ( Figure 12.4.a , Panel C). The location of the points relative to the standardized mean difference contours indicate that the likely effects of the intervention in these studies are small.

An example description of the results from the synthesis is provided in Box 12.4.d .

Box 12.4.d How to describe the results from this synthesis

12.4.2.3 Scenario 4: vote counting based on direction of effect

In Scenario 4, there is minimal reporting of the data, and the type of effect measure (when used) varies across the studies (e.g. mean difference, proportional odds ratio). Of the 15 results, only five report data suitable for meta-analysis (effect estimate and measure of precision; Table 12.4.c , column 8), and no studies reported precise P values. We use this scenario to illustrate vote counting based on direction of effect. For each study, the effect is categorized as beneficial or harmful based on the direction of effect (indicated as a binary metric; Table 12.4.c , column 9).

Of the 15 studies, we exclude three because they do not provide information on the direction of effect, leaving 12 studies to contribute to the synthesis. Of these 12, 10 effects favour midwife-led models of care (83%). The probability of observing this result if midwife-led models of care are truly ineffective is 0.039 (from a binomial probability test, or equivalently, the sign test). The 95% confidence interval for the percentage of effects favouring midwife-led care is wide (55% to 95%).

The binomial test can be implemented using standard computer spreadsheet or statistical packages. For example, the two-sided P value from the binomial probability test presented can be obtained from Microsoft Excel by typing =2*BINOM.DIST(2, 12, 0.5, TRUE) into any cell in the spreadsheet. The syntax requires the smaller of the ‘number of effects favouring the intervention’ or ‘the number of effects favouring the control’ (here, the smaller of these counts is 2), the number of effects (here 12), and the null value (true proportion of effects favouring the intervention = 0.5). In Stata, the bitest command could be used (e.g. bitesti 12 10 0.5 ).

A harvest plot can be used to display the results ( Figure 12.4.a , Panel D), with characteristics of the studies represented using different heights and shading. A sensitivity analysis might be considered, restricting the analysis to those studies judged to be at an overall low risk of bias. However, only four studies were judged to be at a low risk of bias (of which, three favoured midwife-led models of care), precluding reasonable interpretation of the count.

An example description of the results from the synthesis is provided in Box 12.4.e .

Box 12.4.e How to describe the results from this synthesis

Figure 12.4.a Possible graphical displays of different types of data. (A) Box-and-whisker plots of odds ratios for all outcomes and separately by overall risk of bias. (B) Bubble plot of odds ratios for all outcomes and separately by the model of care. The colours of the bubbles represent the overall risk of bias judgement (green = low risk of bias; yellow = some concerns; red = high risk of bias). (C) Albatross plot of the study sample size against P values (for the five continuous outcomes in Table 12.4.c , column 6). The effect contours represent standardized mean differences. (D) Harvest plot (height depicts overall risk of bias judgement (tall = low risk of bias; medium = some concerns; short = high risk of bias), shading depicts model of care (light grey = caseload; dark grey = team), alphabet characters represent the studies)

12.5 Chapter information

Authors: Joanne E McKenzie, Sue E Brennan

Acknowledgements: Sections of this chapter build on chapter 9 of version 5.1 of the Handbook , with editors Jonathan J Deeks, Julian PT Higgins and Douglas G Altman.

We are grateful to the following for commenting helpfully on earlier drafts: Miranda Cumpston, Jamie Hartmann-Boyce, Tianjing Li, Rebecca Ryan and Hilary Thomson.

Funding: JEM is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Career Development Fellowship (1143429). SEB’s position is supported by the NHMRC Cochrane Collaboration Funding Program.

12.6 References

Achana F, Hubbard S, Sutton A, Kendrick D, Cooper N. An exploration of synthesis methods in public health evaluations of interventions concludes that the use of modern statistical methods would be beneficial. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2014; 67 : 376–390.

Becker BJ. Combining significance levels. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. A handbook of research synthesis . New York (NY): Russell Sage; 1994. p. 215–235.

Boonyasai RT, Windish DM, Chakraborti C, Feldman LS, Rubin HR, Bass EB. Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians: a systematic review. JAMA 2007; 298 : 1023–1037.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Meta-Analysis methods based on direction and p-values. Introduction to Meta-Analysis . Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. pp. 325–330.

Brown LD, Cai TT, DasGupta A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Statistical Science 2001; 16 : 101–117.

Bushman BJ, Wang MC. Vote-counting procedures in meta-analysis. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis . 2nd ed. New York (NY): Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. p. 207–220.

Crowther M, Avenell A, MacLennan G, Mowatt G. A further use for the Harvest plot: a novel method for the presentation of data synthesis. Research Synthesis Methods 2011; 2 : 79–83.

Friedman L. Why vote-count reviews don’t count. Biological Psychiatry 2001; 49 : 161–162.

Grimshaw J, McAuley LM, Bero LA, Grilli R, Oxman AD, Ramsay C, Vale L, Zwarenstein M. Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies and programmes. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2003; 12 : 298–303.

Harrison S, Jones HE, Martin RM, Lewis SJ, Higgins JPT. The albatross plot: a novel graphical tool for presenting results of diversely reported studies in a systematic review. Research Synthesis Methods 2017; 8 : 281–289.

Hedges L, Vevea J. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods 1998; 3 : 486–504.

Ioannidis JP, Patsopoulos NA, Rothstein HR. Reasons or excuses for avoiding meta-analysis in forest plots. BMJ 2008; 336 : 1413–1415.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, O’Brien MA, Johansen M, Grimshaw J, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012; 6 : CD000259.

Jones DR. Meta-analysis: weighing the evidence. Statistics in Medicine 1995; 14 : 137–149.

Loughin TM. A systematic comparison of methods for combining p-values from independent tests. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 2004; 47 : 467–485.

McGill R, Tukey JW, Larsen WA. Variations of box plots. The American Statistician 1978; 32 : 12–16.

McKenzie JE, Brennan SE. Complex reviews: methods and considerations for summarising and synthesising results in systematic reviews with complexity. Report to the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. 2014.

O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, Forsetlund L, Bainbridge D, Freemantle N, Davis DA, Haynes RB, Harvey EL. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007; 4 : CD000409.

Ogilvie D, Fayter D, Petticrew M, Sowden A, Thomas S, Whitehead M, Worthy G. The harvest plot: a method for synthesising evidence about the differential effects of interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2008; 8 : 8.

Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ 2011; 342 : d549.

Schriger DL, Sinha R, Schroter S, Liu PY, Altman DG. From submission to publication: a retrospective review of the tables and figures in a cohort of randomized controlled trials submitted to the British Medical Journal. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2006; 48 : 750–756, 756 e751–721.

Schriger DL, Altman DG, Vetter JA, Heafner T, Moher D. Forest plots in reports of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study reviewing current practice. International Journal of Epidemiology 2010; 39 : 421–429.

ter Wee MM, Lems WF, Usan H, Gulpen A, Boonen A. The effect of biological agents on work participation in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2012; 71 : 161–171.

Thomson HJ, Thomas S. The effect direction plot: visual display of non-standardised effects across multiple outcome domains. Research Synthesis Methods 2013; 4 : 95–101.

Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, Evans-Lacko S, Doherty M, Rose D, Koschorke M, Shidhaye R, O’Reilly C, Henderson C. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet 2016; 387 : 1123–1132.

Valentine JC, Pigott TD, Rothstein HR. How many studies do you need?: a primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 2010; 35 : 215–247.

For permission to re-use material from the Handbook (either academic or commercial), please see here for full details.

12.1 Describing Single Variables

Learning objectives.

- Use frequency tables and histograms to display and interpret the distribution of a variable.

- Compute and interpret the mean, median, and mode of a distribution and identify situations in which the mean, median, or mode is the most appropriate measure of central tendency.

- Compute and interpret the range and standard deviation of a distribution.

- Compute and interpret percentile ranks and z scores.

Descriptive statistics refers to a set of techniques for summarizing and displaying data. Let us assume here that the data are quantitative and consist of scores on one or more variables for each of several study participants. Although in most cases the primary research question will be about one or more statistical relationships between variables, it is also important to describe each variable individually. For this reason, we begin by looking at some of the most common techniques for describing single variables.

The Distribution of a Variable

Every variable has a distribution , which is the way the scores are distributed across the levels of that variable. For example, in a sample of 100 university students, the distribution of the variable “number of siblings” might be such that 10 of them have no siblings, 30 have one sibling, 40 have two siblings, and so on. In the same sample, the distribution of the variable “sex” might be such that 44 have a score of “male” and 56 have a score of “female.”

Frequency Tables

One way to display the distribution of a variable is in a frequency table . Table 12.1, for example, is a frequency table showing a hypothetical distribution of scores on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale for a sample of 40 college students. The first column lists the values of the variable—the possible scores on the Rosenberg scale—and the second column lists the frequency of each score. This table shows that there were three students who had self-esteem scores of 24, five who had self-esteem scores of 23, and so on. From a frequency table like this, one can quickly see several important aspects of a distribution, including the range of scores (from 15 to 24), the most and least common scores (22 and 17, respectively), and any extreme scores that stand out from the rest.