Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, the long goodbye.

Now streaming on:

Robert Altman ’s “The Long Goodbye” attempts to do a very interesting thing. It tries to be all genre and no story, and it almost works. It makes no serious effort to reproduce the Raymond Chandler detective novel it’s based on; instead, it just takes all the characters out of that novel and lets them stew together in something that feels like a private-eye movie.

The private eye is, I suppose, a fairly obsolete institution in our society. I’m not talking about the divorce case specialists and the missing persons guys; I’m thinking of the Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Ross MacDonald kind of hired eye whose occupation takes him into glamorous danger and who subscribes to a weary private credo. The private eye as a fiction device was essentially a way to open doors; the best novels of Chandler and the others are simply hooks for a cynical morality.

Altman seems to understand this. He knows we don’t care any more about the plot than he does; he agrees with Hitchcock that it doesn’t even matter what the plot is about (as long as it’s something). The important thing is the way the characters spar with each other. But Altman has added a twist: Instead of making his private eye into a cool, competent professional, he makes him into a 1950s anachronism. Philip Marlowe has been in a lot of movies, but never one in which he was more confused than he is in this one.

The story, or whatever you want to call it, involves a murder, a missing person, and an alcoholic writer with a bewitching blonde wife. There are also some gangsters and a cat. The writer and his wife are played with really fine style by Sterling Hayden and Nina van Pallandt -- who not only demonstrates that she can act, but also that a real woman is infinitely more interesting on the screen than some starlet beauty-school graduate who should be leading the pompon team.

The middle of this mess is inhabited by Elliott Gould , as the chain-smoking, mumbling, disorganized Marlowe. It’s a good performance, particularly the virtuoso ten-minute stretch at the beginning of the movie when he goes out to buy food for his cat. Gould has enough of the paranoid in his acting style to really put over Altman’s revised view of the private eye.

Altman doesn’t string his scenes together to tell a taut story, but he directs each scene as if he were. There’s an especially memorable scene involving Philip Marlowe and a gangster (played by Mark Rydell , who is usually a director). The gangster smacks his girlfriend with a pop bottle and then snarls at Marlowe: “Now that’s someone I love. Think what could happen to you.” The scene sounds rather grim in print, I know, but in the movie it has a kind of hard-boiled desperation to it. It feels like it belongs in a private eye’s life and so does the whole movie -- right up to the ending, which is really off the wall.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

Now playing

Dune: Part Two

Brian tallerico.

American Dreamer

Carla renata.

Io Capitano

On the Adamant

Peter sobczynski.

Asleep in My Palm

Tomris laffly.

The Animal Kingdom

Monica castillo, film credits.

The Long Goodbye (1973)

112 minutes

Directed by

- Robert Altman

- Leigh Brackett

Based on the novel by

- Raymond Chandler

Latest blog posts

The People’s Joker and Six Other Films That Were Stuck in Legal Limbo

Metrograph Highlights Remarkable Career of Lee Chang-dong

Female Filmmakers in Focus: Alice Rohrwacher on La Chimera

On Luca, Tenet, The Invisible Man and Other Films from the Early Pandemic Era that Deserve More Big-Screen Time

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Revisiting Altman's 'The Long Goodbye'

By Terrence Rafferty

- April 13, 2007

NEW YORK — Raymond Chandler, the creator of the tough-but-honorable Los Angeles private detective Philip Marlowe, once wrote in a letter to a friend: "The private eye is admittedly an exaggeration - a fantasy. But at least he's an exaggeration of the possible." When Robert Altman made a movie of the novel Chandler considered his best, "The Long Goodbye," Marlowe, played by Elliott Gould, seemed at first glance almost unrecognizable as the character audiences had seen embodied by, among others, Humphrey Bogart, in Howard Hawks's "Big Sleep" (1946). But although plenty had changed in the 20 years between the publication of the novel and the release of the movie in 1973, the new Marlowe was in most respects the same as ever: solitary, rumpled, nicotine-dependent, irreverent of power both legitimate (the cops) and illegitimate (the crooks), and weirdly, stubbornly gallant. The only difference - a big one - is that he no longer feels possible.

Altman's "Long Goodbye," a fresh print of which was to begin a weeklong run at Film Forum here on Friday, is neither a homage nor a deconstruction, though it contains elements of both. It's a film about transience, about the awful fragility of the things we want to think are built to last: friendships, marriages, faiths of all kinds - including the faith that pop culture can sometimes makes us feel in powerful fantasy figures like Marlowe and his jaunty, street-smart, superbly incorruptible ilk.

The lone-wolf private eye was in its time - from the heyday of pulp magazines in the 1920s and 1930s through the film noir era of the '40s and '50s - a pretty unbeatable archetype of modern masculine heroism: more independent than a policeman or a soldier, sexier than a Spencer Tracy priest, more virile than a screwball-comedy playboy and exponentially wittier than a cowboy. It was a myth for an urban society, and it didn't quite survive the great postwar migration to the suburbs, where the streets just didn't seem mean enough (then) to need a Marlowe to go down them.

Chandler, who was over 60 when he wrote "The Long Goodbye," clearly understood that the private eye's time was passing, along with too much else he cared about: his wife of 30 years was dying, not quickly. "I wrote it in agony, but I wrote it," he told friends later, and you can feel his agony throughout the book.

The novel is more contemplative, less eventful, less exuberant than early books and although the story supplies a few gangsters and annoying cops for Marlowe to crack wise at, the jokes don't have their old gleeful snap. That's probably deliberate to some extent. Chandler was keenly aware that his once-distinctive style had been so widely imitated that, as he put it, "you begin to look as if you were imitating your imitators"; but it's also plainly a reflection of his mournful mood.

You don't call a book "The Long Goodbye" unless you're feeling elegiac. And Altman's movie, in its eccentric way, keeps faith with Chandler's melancholy. The mystery, such as it is, has to do with whether the detective's friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) killed his wife. Marlowe, who has obligingly driven him to Mexico in the middle of the night, doesn't believe he did; the private eye dummies up when the police come calling and spends a couple of nights in jail rather than betray his murder-suspect friend. This gesture attracts the attention of a cool blonde named Eileen Wade (Nina Van Pallandt), a Malibu neighbor of the Lennoxes. She hires Marlowe to bring home her wayward husband, Roger (Sterling Hayden), an alcoholic novelist suffering from a spectacular creative block of unknown (perhaps guilty) origin. All the mysteries get resolved, mostly unhappily and mostly no thanks to the investigative acumen of Marlowe, who looks as if he were so far behind the curve of the truth that he'd actually been lapped a few times.

The idea that the beloved Marlowe could be portrayed as a baffled anachronism wasn't an especially startling notion in the early '70s. Movie private eyes hadn't looked very vigorous for a while, even when they were played by actors as charismatic as Paul Newman in "Harper" (1966) and James Garner in "Marlowe" (1969), an updated adaptation of Chandler's 1949 novel "The Little Sister." The stars did their jobs, but the '60s milieu they moved through in those pictures failed to cooperate; it appeared flattened out, drained of energy, and the private eyes seemed stranded and maybe a little bored, as if the world wasn't really worth the trouble to make sense of. The verbal style of hard-boiled fiction (Chandler's in particular) and the high-contrast visual style of film noir added up to an impressively coherent imaginative universe, in which the classic private eye could operate effectively and get to the bottom of things with nothing more than nerve, mother wit and local knowledge.

But what Altman does in "The Long Goodbye" goes way beyond simply stating the idea that the private eye's day was over. Instead of trying to correct, or ignore, the creeping vagueness of the landscape in which his lonely hero is a figure, he actually emphasizes those qualities. The images captured by his cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond, are as un-noirish as they can be: sun-bleached, unstable, heat-shimmery as mirages.

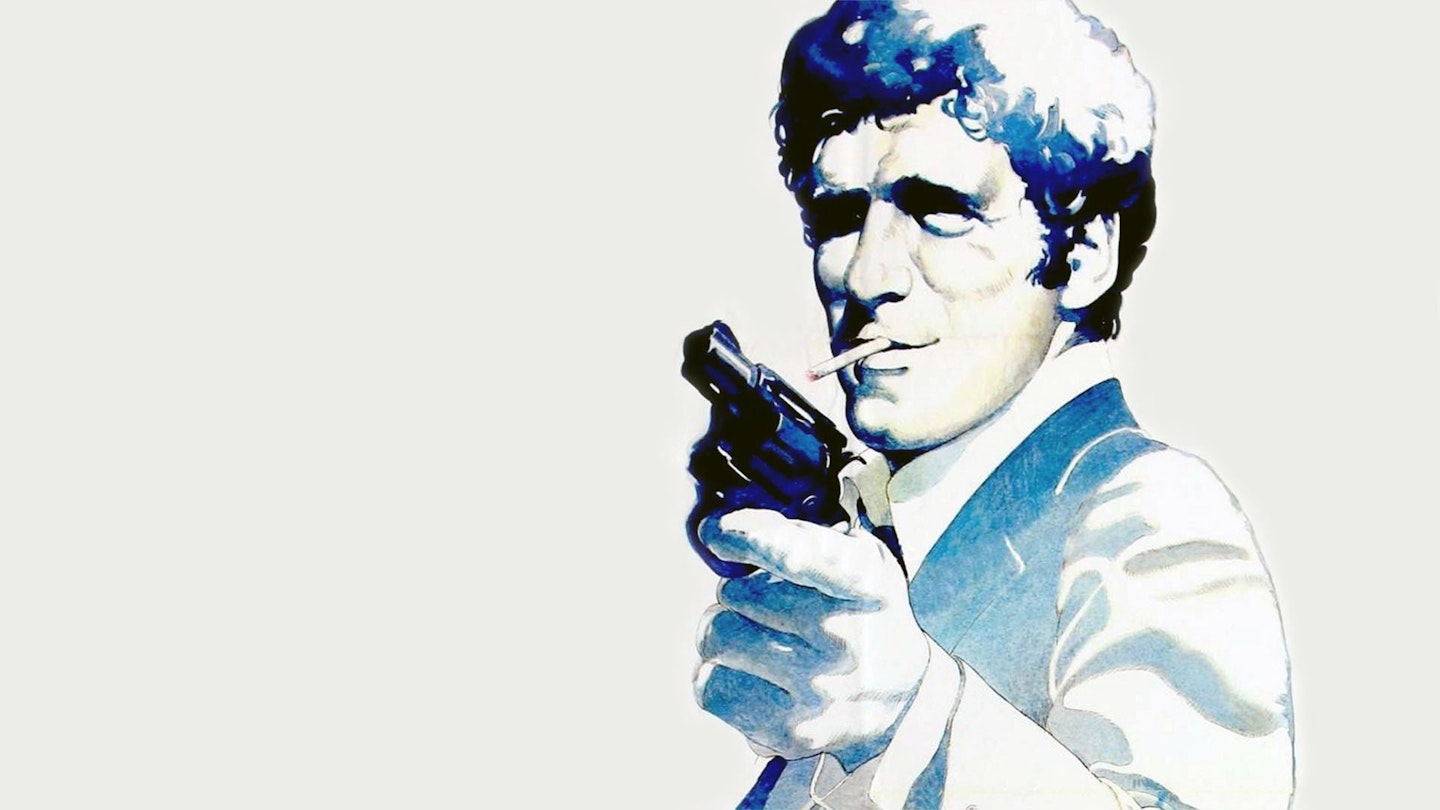

The movie manages to stylize an absence of style, the bland fluidity of early '70s Southern California, the very thing that makes Marlowe obsolete. He wears a black suit and a white shirt; he's a hard-edged line drawing in the middle of a runny watercolor, and he couldn't look more forlorn.

And Gould plays Marlowe as if the character knows that he is disappearing. This private eye is so private that he seems always to be talking to himself, mumbling a running commentary on the action in an attempt to convince himself, against the evidence of the world's near-total indifference to everything he says or does, that he really does exist. That is what it's like when pop culture archetypes start to fade in the imagination: They turn inward, they become bewildered and self-aware, and then they just get smaller and smaller, as Marlowe does in the long last shot of "The Long Goodbye," heading for the vanishing point.

The funny thing is, he's dancing a little as he recedes from view. He looks magically unburdened of his mythic responsibilities. The surprise of Altman's "Long Goodbye" isn't that it's elegiac - it has to be - but that it's such a blithe, rambunctious elegy.

Chandler, with a touch of defensiveness, said of his novel, "I wrote this as I wanted to because I can do that now," and Altman, in that spirit, made his movie as he wanted to, because he could do that in the early '70s, before the world of Hollywood filmmaking changed on him. Watching "The Long Goodbye" in 1973, you could feel Marlowe dancing on his own grave. Watching it now, you can see Altman dancing with him.

The Definitive Voice of Entertainment News

Subscribe for full access to The Hollywood Reporter

site categories

‘the long goodbye’: thr’s 1973 review.

On March 7, 1973, Robert Altman unveiled his two-hour, R-rated noir in theaters.

By Alan R. Howard

Alan R. Howard

- Share this article on Facebook

- Share this article on Twitter

- Share this article on Flipboard

- Share this article on Email

- Show additional share options

- Share this article on Linkedin

- Share this article on Pinit

- Share this article on Reddit

- Share this article on Tumblr

- Share this article on Whatsapp

- Share this article on Print

- Share this article on Comment

On March 7, 1973, Robert Altman unveiled his two-hour, R-rated noir adaptation of The Long Goodbye in theaters. The Hollywood Reporter’s original review of the United Artists film is below.

Robert Altman’s film of Raymond Chandler’s novel The Long Goodbye , produced by Jerry Bick from a screenplay by Leigh Brackett , is as witty as any movie ever made. Its scenes are so resourceful and so emotionally appealing that they nearly succeed in overcoming some careless plotting.

The eccentric casting of Elliott Gould is altogether successful and allows the filmmakers to embrace the detective genre affectionately, transforming it into a dreamlike excursion through modern Los Angeles.

Gould’s Philip Marlowe is no beat-’em-up tough guy; he’s a wistfully human and tolerantly benign anachronism. He isn’t, of course, Humphrey Bogart, but it would have been foolish to chase the achievements of The Big Sleep in 1973. Instead, The Long Goodbye charts its own perverse course, throwing much (perhaps too much) of Chandler’s novel out the window.

A friend (Jim Bouton ) asks Marlowe to drive him to Tijuana in the middle of the night. Upon his return, Marlowe is arrested because Bouton’s wife has been viciously murdered. He is released three days later when it is learned that Bouton has written a confession and supposedly committed suicide.

The beautiful wife (Nina van Palandt ) of a successful but alcoholic writer (Sterling Hayden) engages Marlowe to retrieve her husband from a sanitarium run by Henry Gibson. A gangster (Mark Rydell ) assumes that Marlowe can find a vast sum of money Bouton has stolen from him. The elements of the mystery ultimately converge into a series of denouements.

Unfortunately, the plot is not as interesting to Altman as it should be. Perhaps his recklessness with story mechanics is the cost of creating the parade of remarkable scenes, as good as any ever made in the genre (and that includes The Big Sleep ). But because the scenes don’t mesh into a whole, the drama never becomes as powerful as its elements.

Leigh Brackett’s screenplay provides dialogue as brittle and humorous as Mankiewicz’s in All About Eve. Brackett’s ear is inventive, oblique and frequently hilarious. Coupled with Altman’s flair for improvisation, Brackett’s work gives The Long Goodbye humanity and reality.

Altman’s style has the finesse and control of a true filmmaker; his movies look and feel like no one else’s. He stages his scenes with a fluid, probing camera that relentlessly, but affectionately, unmasks his characters as they try to maintain their shaky identities.

There isn’t a mediocre performance in the movie, and Altman turns The Long Goodbye over to his inspired performers. Gould has never been more relaxed or likeable ; his essential innocence is unusual for the Marlowe character but engages the audience and allows Altman to comment subtly on corruption.

Van Pallandt’s screen debut reveals her to be a ravishing, mature beauty with charm and elegance. She’s one of the villains, and what’s disturbing about the movie is that she is presented as a totally sympathetic, if inaccessible, character.

Hayden’s flamboyant performance is probably a great one; it has the ache of writer’s block and alcoholism to it. Rydell’s hoodlum czar is something new in movies — a nouveau riche gangster, a hilarious piece of social portraiture.

Gibson is sinister as a creepy doctor whose function in the story gets lost along the way. David Arkin , as a fledgling mobster, is extremely funny; Bouton is properly arrogant as Marlowe’s playboy friend. Warren Berlinger , Jo Ann Brody, Ken Sansom and Steve Coit are all excellent in smaller parts.

Technically, the movie is consistently remarkable; there isn’t a lazy shot in it. Vilmos Zsigmond’s rococo photography is hypnotic and less mannered than it has been in previous Altman movies. Lou Lombardo’s film editing is generous to the actors and builds scenes carefully for feeling and atmosphere.

There is no credit for production design; the selection of locations is unusually fresh. John V. Speak’s sound is excellent, particularly in light of the awkward (for recording) locations.

The title song by John Williams and Johnny Mercer is wonderfully Forties in feeling; it is used wittily several times throughout the movies in different styles. It’s a leitmotif reminder that The Long Goodbye is a gloriously inspired tribute to Hollywood that never loses sight of what Los Angeles has become. — Alan R. Howard, originally published on Feb. 28, 1973

Twitter: @THRArchives

Related Stories

'nashville': thr's 1975 review, thr newsletters.

Sign up for THR news straight to your inbox every day

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Hunter schafer faces horrors at german resort in neon’s ‘cuckoo’ trailer, minnie driver claims ‘hard rain’ producers denied her a wetsuit because “they wanted to see my nipples”, carla gugino says it was “physically totally impossible” that she played a mother in 2001’s ‘spy kids’, bambi goes on a rampage in first teaser for poohniverse movie ‘bambi: the reckoning’, ‘boiling point’ director philip barantini to helm dennis lehane adaptation ‘a bostonian’ (exclusive), ‘the first omen’ director arkasha stevenson says classic horror franchise has plenty of stories left.

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

The Long Goodbye

Private investigator Philip Marlowe helps a friend out of a jam, but in doing so gets implicated in his wife's murder. Private investigator Philip Marlowe helps a friend out of a jam, but in doing so gets implicated in his wife's murder. Private investigator Philip Marlowe helps a friend out of a jam, but in doing so gets implicated in his wife's murder.

- Robert Altman

- Leigh Brackett

- Raymond Chandler

- Elliott Gould

- Nina van Pallandt

- Sterling Hayden

- 219 User reviews

- 129 Critic reviews

- 87 Metascore

- 2 wins & 1 nomination

- Philip Marlowe

- Eileen Wade

- Marty Augustine

- Dr. Verringer

- Terry Lennox

- Jo Ann Eggenweiler

- Detective Farmer

- (as Steve Coit)

- (as Vince Palmieri)

- (as Pancho Cordoba)

- Rutanya Sweet

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia The location for Sterling Hayden 's home was actually Robert Altman 's home at the time.

- Goofs Marlowe's initial line following Dr. Verringer's demand of $4400 from Roger Wade (in the hospital) appears to be dubbed. Marlowe lights a cigarette and does not move his mouth as the line is heard.

Philip Marlowe : Nobody cares but me.

Terry Lennox : Well that's you, Marlowe. You'll never learn, you're a born loser.

Philip Marlowe : Yeah, I even lost my cat.

- Connections Edited into El adios largos (2013)

- Soundtracks The Long Goodbye by John Williams and Johnny Mercer Performed by The Dave Grusin Trio, Jack Sheldon , Clydie King , Jack Riley , Morgan Ames , Aluminum Band, The Tepoztlan Municipal Band

User reviews 219

- Lechuguilla

- Jun 11, 2006

- How long is The Long Goodbye? Powered by Alexa

- Why did Verringer have such an outsized influence over Wade? If his fee was not for providing an alibi, then was it just for treatment?

- March 8, 1973 (United States)

- United States

- Der Tod kennt keine Wiederkehr

- High Tower - High Tower Drive, North Hollywood, Los Angeles, California, USA

- Lion's Gate Films

- United Artists

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- $1,700,000 (estimated)

Technical specs

- Runtime 1 hour 52 minutes

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed

Accessibility Links

The Long Goodbye (1973) review — an ambitious and artful reinvention

Challenge yourself with today’s puzzles.

★★★★☆ Up there with The Big Sleep as the definitive screen Chandler, this hard-boiled noir from Robert Altman benefits from an inspired era shift. No more 1940s Los Angeles, this caper has been dragged into the 1970s, which makes its dark-suited chain-smoking protagonist Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) even more discomfited (he’s surrounded by hippies, hepcats and flower power girls).

The plot is fabulously generic, with a femme fatale (Nina van Pallandt), a mobster (Mark Rydell) and a missing case of cash. Sterling Hayden is typically intimidating as an alcoholic writer, and Arnold Schwarzenegger pops up in a wordless cameo as a mustachioed henchman. Some of the improvisational scenes don’t entirely work, but it’s an ambitious and artful reinvention. PG, 112min . Showing at the BFI

Related articles

review | The Long Goodbye

related reviews

Kaleidescape | Nashville

Amazon Prime | California Split

Kaleidescape | A Clockwork Orange

Kaleidescape | Chinatown

see more in Reviews

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to stay up to date on Cineluxe

Robert Altman’s sui generis noir looks suitably grubby in this Blu-ray-quality download

by Michael Gaughn April 14, 2021

Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye is one of the best films of the 1970s—maybe the best—and one of the most influential. That last part is ironic, in a way Altman would have appreciated, because there’s no way it can be in any legitimate sense true. Altman and Kubrick created films that came from such an intricate and hermetic personal aesthetic that it’s impossible for them to be built upon without the result being anything other than travesty. That doesn’t mean legions haven’t tried, but all have failed.

I asked Altman once what he thought of the fact that The Long Goodbye closed almost as soon as it opened but has become possibly his best-known work. He deflected, with a purpose, saying his Phillip Marlowe fell asleep in the early ‘50s—the era of Chandler’s source novel—only to wake up in the early ‘70s, finding his sense of chivalry was no longer in fashion and could only lead to disaster. Even Altman’s Marlowe would be completely lost in the sociopathic present.

The Long Goodbye both is and isn’t a detective movie; is an unforgiving evisceration of Chandler’s work and a very heartfelt tribute. It’s so cynical it verges on nihilism while openly trying to figure out which values, if any, still have meaning. And because it lives both in and outside genre, it gets to feed from both worlds, very much like early Godard. There are very few films that feel this much like a movie .

Altman, of course, makes none of it easy, constantly toying with the audience like a sly, somewhat sadistic, cat. He and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond did everything they could to make the film gritty, flashing the footage, flattening the palette, pumping up the grain. The result eschews superficial prettiness, which tends to be fleeting, to tap into something far more sublime.

This is John Williams’ best score (no, I’m not being facetious) exactly because it’s so awful. Williams isn’t known for having a sense of humor so I have to wonder if he didn’t just write a bunch of straight cues, not fully aware of how Altman was planning to deploy them.

And then there’s Elliot Gould’s almost non-existent range as an actor, which Altman turns to the film’s advantage by making his Marlowe continually spout lame, often improvised, wisecracks. Altman has everything around Gould do the acting for him, which results in Marlowe coming across as smug but ultimately lost.

To add irony to all the other irony, The Long Goodbye probably holds up as well as it does both because it’s Altman’s most genre-driven movie and because enough of what’s best of Chandler’s work manages to survive the merciless beating it receives here to permeate the film and give it a resonance unique to Altman’s canon.

And if all of that is just a little too high-brow for you, watch this movie just to revel in the secondary casting. Sterling Hayden is still astonishing as the washed-up writer on a fatal binge. Just as nobody seeing him as Dix Handley in The Asphalt Jungle could have anticipated his performance as General Ripper in Dr. Strangelove , nobody seeing those two earlier films could have ever seen his Roger Wade coming. And yet there’s something at Hayden’s core that creates a through-line that joins those characters in a way that goes well beyond their having been played by the same performer.

And nobody seeing Henry Gibson on The Dick Van Dyke Show or Laugh-In could have anticipated his Dr. Veringer in a million years. Gibson and Altman conspired to pull off a tremendous practical joke that’s simultaneously, when seen from just the right angle, chilling. It’s that he’s the least likely villain ever that makes him so apt.

As for the presentation: How do you judge the image quality of a film that went out of its way to not look very good? To reference my earlier thought, there’s that beauty that comes from aping the styles of the present, which rarely ages well, and then there’s the beauty that comes from staying true to the demands of the material, even if it takes you to deeply unpleasant places. The Long Goodbye is gorgeous exactly because it’s lurid, and because it’s as lurid in the heart of the Malibu Colony as it is in a decrepit city jail. While there’s plenty of Southern California sunshine in evidence, it’s always accurately shown as monotonous or piercing, never pleasant.

This Blu-ray-quality download does a pretty good job of honoring what Altman and Zsigmond wrought, and you can’t help but recoil in horror at the thought of some culturally myopic tech team scrubbing it free of grain and trying to expand its dynamic range. Still, matching its original resolution would likely yield huge improvements, and a deft touch with an appreciation for grunge could conjure up something amazing.

In a similar vein, should an upgrade some day come, someone should post a sign reading “Hands Off the Soundtrack” on the mixing-room door. This film would not benefit from a surround mix—stereo suits it just fine.

The Long Goodbye is the kind of art that appears when you just don’t care at all but can’t help but care a lot. It feeds from a wellspring of paradox and, while it wraps things up, it never really resolves a thing. There are no reliable guideposts. Nothing triumphs; nothing is vanquished. That constant troubling creates an energy that keeps Altman’s film vital and relevant, and impossible to dismiss as simply smart-ass. The result is nothing but a mess, but a strangely elegant one that somehow rings very true.

Michael Gaughn —The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable , marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | This Blu-ray-quality download does a pretty good job of honoring what Robert Altman and Vilmos Zsigmond wrought. Still, matching its original resolution would likely yield huge improvements, and a deft touch with an appreciation for grunge could conjure up something amazing.

SOUND | Should an upgrade some day come, someone should post a sign reading “Hands Off the Soundtrack” on the mixing-room door. This film would not benefit from a surround mix—stereo suits it just fine.

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC

sign up for our newsletter

receive a monthly recap of everything that’s new on Cineluxe

The Long Goodbye – Review by Pauline Kael

- July 16, 2021

Movieland—The bums’ Paradise

by Pauline Kael

Edmund Wilson summed up Raymond Chandler convincingly in a 1945 when he said of Farewell, My Lovely, “It is not simply a question here of a puzzle which has been put together but of a malaise conveyed to the reader, the horror of a hidden conspiracy which is continually turning up in the most varied and unlikely forms. . . . It is only when I get to the end that I feel my old crime-story depression descending upon me again — because here again, as is so often the case, the explanation of the mysteries, when it comes, is neither interesting nor plausible enough. It fails to justify the excitement produced by the picturesque and sinister happenings, and I cannot help feeling cheated.” Locked in the conventions of pulp writing, Raymond Chandler never found a way of dealing with that malaise. But Robert Altman does, in The Long Goodbye, based on Chandler’s 1953 Los Angeles-set novel. The movie is set in the same city twenty years later; this isn’t just a matter of the private-detective hero’s prices going from twenty-five dollars a day to fifty — it’s a matter of rethinking the book and the genre. Altman, who probably works closer to his unconscious than any other American director, tells a detective story, all right, but he does it through a spree — a high-flying rap on Chandler and the movies and that Los Angeles sickness. The movie isn’t just Altman’s private-eye movie — it’s his Hollywood movie, set in the mixed-up world of movie-influenced life that is L.A.

In Los Angeles, you can live any way you want (except the urban way); it’s the fantasy-brothel, where you can live the fantasy of your choice. You can also live well without being rich, which is the basic and best reason people swarm there. In that city — the pop amusement park of the shifty and the uprooted, the city famed as the place where you go to sell out — Raymond Chandler situated his incorruptible knight Philip Marlowe, the private detective firmly grounded in high principles. Answering a letter in 1951, Chandler wrote, “If being in revolt against a corrupt society constitutes being immature, then Philip Marlowe is extremely immature. If seeing dirt where there is dirt constitutes an inadequate social adjustment, then Philip Marlowe has inadequate social adjustment. Of course Marlowe is a failure, and he knows it. He is a failure because he hasn’t any money. . . . A lot of very good men have been failures because their particular talents did not suit their time and place.” And he cautioned, “But you must remember that Marlowe is not a real person. He is a creature of fantasy. He is in a false position because I put him there. In real life, a man of his type would no more be a private detective than he would be a university don.” Six months later, when his rough draft of The Long Goodbye was criticized by his agent, Chandler wrote back, “I didn’t care whether the mystery was fairly obvious, but I cared about the people, about this strange corrupt world we live in, and how any man who tried to be honest looks in the end either sentimental or plain foolish.”

Chandler’s sentimental foolishness is the taking-off place for Altman’s film. Marlowe (Elliott Gould) is a wryly forlorn knight, just slogging along. Chauffeur, punching bag, errand boy, he’s used, lied to, double-crossed. He’s the gallant fool in a corrupt world — the innocent eye. He isn’t stupid and he’s immensely likable, but the pulp pretense that his chivalrous code was armor has collapsed, and the romantic machismo of Bogart’s Marlowe in The Big Sleep has evaporated. The one-lone-idealist-in-the-city-crawling-with-rats becomes a schlemiel who thinks he’s tough and wise. (He’s still driving a 1948 Lincoln Continental and trying to behave like Bogart.) He doesn’t know the facts of life that everybody else knows; even the police know more about the case he’s involved in than he does. Yet he’s the only one who cares. That’s his true innocence, and it’s his slack-jawed crazy sweetness that keeps the movie from being harsh or scabrous.

Altman’s goodbye to the private-eye hero is comic and melancholy and full of regrets. It’s like cleaning house and throwing out things that you know you’re going to miss — there comes a time when junk dreams get in your way. The Long Goodbye reaches a satirical dead end that kisses off the private-eye form as gracefully as Beat the Devil finished off the cycle of the international-intrigue thriller. Altman does variations on Chandler’s theme the way the John Williams score does variations on the title song, which is a tender ballad in one scene, a funeral dirge in another. Williams’ music is a parody of the movies’ frequent overuse of a theme, and a demonstration of how adaptable a theme can be. This picture, less accidental than Beat the Devil, is just about as funny, though quicker-witted, and dreamier, in soft, mellow color and volatile images — a reverie on the lies of old movies. It’s a knockout of a movie that has taken eight months to arrive in New York because after opening in Los Angeles last March and being badly received (perfect irony) it folded out of town. It’s probably the best American movie ever made that almost didn’t open in New York. Audiences may have felt they’d already had it with Elliott Gould; the young men who looked like him in 1971 have got cleaned up and barbered and turned into Mark Spitz. But it actually adds poignancy to the film that Gould himself is already an anachronism.

Thinner and more lithe than in his brief fling as a superstar (his success in Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice and M*A*S*H led to such speedy exploitation of his box-office value that he appeared in seven films between 1969 and 1971), Gould comes back with his best performance yet. It’s his movie. The rubber-legged slouch, the sheepish, bony-faced angularity have their grace; drooping-eyed, squinting, with more blue stubble on his face than any other hero on record, he’s a loose and woolly, jazzy Job. There’s a skip and bounce in his shamble. Chandler’s arch, spiky dialogue — so hardboiled it can make a reader’s teeth grate—gives way to this Marlowe’s muttered, befuddled throwaways, his self-sendups. Gould’s Marlowe is a man who is had by everybody — a male pushover, reminiscent of Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity. He’s Marlowe as Miss Lonely- hearts. Yet this softhearted honest loser is so logical a modernization, so right, that when you think about Marlowe afterward you can t imagine any other way of playing him now that wouldn’t be just fatuous. (Think of Mark Spitz as Marlowe if you want fatuity pure.) The good-guys-finish-last conception was implicit in Chandler s L.A. all along, and Marlowe was only one step from being a clown, but Chandler pulped his own surrogate and made Marlowe, the Victorian relic, a winner. Chandler has a basic phoniness that it would have been a cinch to exploit. He wears his conscience right up front; the con trick is that it’s not a writer’s conscience. Offered the chance to break free of the straitjacket of the detective novel, Chandler declined. He clung to the limiting stereotypes of pop writing and blamed “an age whose dominant note is an efficient vulgarity, an unscrupulous scramble for the dollar.” Style, he said, “can exist in a savage and dirty age, but it cannot exist in the Coca-Cola age . . . the Book of the Month, and the Hearst Press.” It was Marlowe, the independent man, dedicated to autonomy — his needs never rising above that twenty-five dollars a day— who actually lived like an artist. Change Marlowe’s few possessions, “a coat, a hat, and a gun,” to “a coat, a hat, and a typewriter,” and the cracks in Chandler’s myth of the hero become a hopeless split.

Robert Altman is all of a piece, but he’s complicated. You can’t predict what’s coming next in the movie; his plenitude comes from somewhere beyond reason. An Altman picture doesn’t have to be great to be richly pleasurable. He tosses in more than we can keep track of, maybe more than he bothers to keep track of; he nips us in surprising ways. In The Long Goodbye, as in M*A*S*H, there are cli- maxes, but you don’t have the sense of waiting for them, because what’s in between is so satisfying. He underplays the plot and concentrates on the people, so it’s almost all of equal interest, and you feel as if it could go on indefinitely and you’d be absorbed in it. Altman may have the most glancing touch since Lubitsch, and his ear for comedy is better than anybody else’s. In this period of movies, it isn’t necessary (or shouldn’t be) to punch the nuances home; he just glides over them casually, in the freest possible way. Gould doesn’t propel the action as Bogart did; the story unravels around the private eye — the corrupt milieu wins. Maybe the reason some people have difficulty getting onto Altman’s wavelength is that he’s just about incapable of overdramatizing. He’s not a pusher. Even in this film, he doesn’t push decadence. He doesn’t heat up angst the way it was heated in Midnight Cowboy and They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

Pop culture takes some nourishment from the “high” arts, but it feeds mainly on itself. The Long Goodbye had not been filmed before, because the hook carne out too late, after the private-eye-movie cycle had peaked. Marlowe had already become Bogart, and you could see him in it when you read the hook. You weren’t likely to have kept the other Marlowes of the forties (Dick Powell, Robert Montgomery, George Montgomery) in your mind, and you had to see somebody in it. The novel reads almost like a parody of pungent writing — like a semi- literate’s idea of great writing. The detective-novel genre always verged on self-parody, because it gave you nothing under the surface. Hemingway didn’t need to state what his characters felt, because his external descriptions implied all that, but the pulp writers who imitated Hemingway followed the hardboiled-detective pattern that Hammett had in- vented; they externalized everything and implied nothing. Their gaudy terseness demonstrates how the novel and the comic strip can merge. They described actions and behavior from the outside, as if they were writing a script that would be given some inner life by the actors and the director; the most famous practitioners of the genre were, in fact, moonlighting screenwriters. The Long Goodbye may have good descriptions of a jail or a police lineup, but the prose is alternately taut and lumpy with lessons in corruption, and most of the great observations you’re supposed to get from it are just existentialism with oil slick. With its classy dames, a Marlowe influenced by Marlowe, the obligatory tension between Marlowe and the cops, and the sentimental bar scenes, The Long Goodbye was a product of the private-eye films of the decade before. Chandler’s corrupt milieu — what Auden called “The Great Wrong Place” — was the new-style capital of sin, the city that made the movies and was made by them.

In Chandler’s period (he died in 1959), movies and novels interacted; they still do, but now the key interaction may be between movies and movies — and between movies and us. We can no longer view ourselves — the way Nathanael West did — as different from the Middle Westerners in L.A. lost in their movie-fed daydreams, and the L.A. world founded on pop is no longer the world out there, as it was for Edmund Wilson. Altman’s The Long Goodbye (like Paul Mazursky’s Blume in Love ) is about people who live in L.A. because they like the style of life, which Comes from the movies. It’s not about people who work in movies but about people whose lives have been shaped by them; it’s set in the modern L.A. of the stoned sensibility, where people have given in to the beauty that always looks unreal. The inhabitants are an updated gallery of California freaks, with one character who links this world to Nathanael West’s — the Malibu Colony gatekeeper (Ken Sansom), who does ludicrous, pitiful impressions of Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity (which was Chandler’s first screenwriting job), and of James Stewart, Walter Brennan, and Cary Grant (the actor Chandler said he had in mind for Marlowe). In a sense, Altman here has already made Day of the Locust. (To do it as West intended it, and to have it make contemporary sense, it would now have to be set in Las Vegas.) Altman’s references to movies don’t stick out — they’re just part of the texture, as they are in L.A. — but there are enough so that a movie pedant could do his own weirdo version of A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake.

The one startlingly violent action in the movie is performed by a syndicate boss who is as rapt in the glory of his success as a movie mogul. Prefigured in Chandler’s description of movie producers in his famous essay “Writers in Hollywood,” Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell) is the next step up in paranoid self-congratulation from the Harry Cohn- like figure that Rod Steiger played in The Big Knife-, he’s freaked out on success, L.A.-Las Vegas style. His big brown eyes with their big brown bags preside over the decaying pretty-boy face of an Eddie Fisher, and when he flashes his ingenuous Paul Anka smile he’s so appalling he’s comic. His violent act is outrageously gratuitous (he smashes a Coke bottle in the fresh young face of his unoffending mistress), yet his very next line of dialogue is so comic-tough that we can’t help laughing while we’re still gasping, horrified — much as we did when Cagney shoved that half grapefruit in Mae Clarke’s nagging kisser. This little Jewish gangster-boss is a mod imp — offspring of the movies, as much a creature of show business as Joel Grey’s m.c. in Cabaret. Marty Augustine’s bumbling goon squad (ethnically balanced) are the illegitimate sons of Warner Brothers. In the Chandler milieu, what could be better casting than the aristocratic Nina van Pallandt as the rich dish — the duplicitous blonde, Mrs. Wade? And, as her husband, the blocked famous writer Roger Wade, Sterling Hayden, bearded like Neptune, and as full of the old mach as the progenitor of tough-guy writing himself. The most movieish bit of dialogue is from the hook: when the police come to question Marlowe about his friend Terry Lennox, Marlowe says, “This is where I say, ‘What’s this all about?’ and you say, ‘We ask the questions.’ ” But the resolution of Marlowe’s friendship with Terry isn’t from Chandler, and its logic is probably too brutally sound for Bogart- lovers to stomach. Terry Lennox (smiling Jim Bouton, the baseball player turned broadcaster) becomes the Harry Lime in Marlowe’s fife, and the final sequence is a variation on The Third Man, with the very last shot a riff on the leave-taking scenes of the movies’ most famous clown.

The movie achieves a self-mocking fairy-tale poetry. The slippery shifts within the frames of Vilmos Zsigmond’s imagery are part of it, and so are the offbeat casting (Henry Gibson as the sinister quack Dr. Ver- ringer; Jack Riley, of the Bob Newhart show, as the piano player) and the dialogue. (The script is officially credited to the venerable pulp author Leigh Brackett ; she also worked on The Big Sleep and many other good movies, but when you hear the improvised dialogue you can’t take this credit literally.) There are some conceits that are fairly precarious (the invisible-man stunt in the hospital sequence) and others that are waywardly funny (Marlowe trying to lie to his cat) or suggestive and beautiful (the Wades’ Doberman coming out of the Pacific with his dead master’s cane in his teeth). When Nina van Pallandt thrashes in the ocean at night, her pale-orange butterfly sleeves rising above the surf, the movie becomes a rhapsody on romance and death. What separates Altman from other directors is that time after time he can attain crowning visual effects like this and they’re so elusive they’re never precious. They’re like ribbons tying up the whole history of movies. It seems unbelievable that people who looked at this picture could have given it the reviews they did.

The out-of-town failure of The Long Goodbye and the anger of many of the reviewers, who reacted as if Robert Altman were a destroyer, suggest that the picture may be on to something bigger than is at first apparent. Some speculations may be in order. Marlowe was always a bit of a joke, but did people take him that way? His cynical exterior may have made it possible for them to accept him in Chandler’s romantic terms, and really — below the joke level — believe in him. We’ve all read Chandler on his hero: “But down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.” He goes, apparently, in our stead. And as long as he’s there — the walking conscience of the world — we’re safe. We could easily reject sticky saviors, but a cynical saviour satisfies the Holden Caulfield in us. It’s an adolescent’s dream of heroism — someone to look after you, a protector like Billy Jack. And people cleave to the fantasies they form while watching movies.

After reading The Maltese Falcon, Edmund Wilson said of Dashiell Hammett that he “lacked the ability to bring the story to imaginative life.” Wilson was right, of course, but this may be the basis of Hammett’s appeal; when Wilson said of the detective story that “as a department of imaginative writing, it looks to me completely dead,” he was (probably intentionally) putting it in the wrong department. It’s precisely the fact that the detective novel is engrossing but does not impinge on its readers’ lives or thoughts that enables it to give a pleasure to some which is distinct from the pleasures of literature. It has no afterlife when they have closed the covers; it’s completely digested, like a game of casino. It’s a structured time killer that gives you the illusion of being speedy; The Long Goodbye isn’t a fast read, like Hammett, but when I finished it I had no idea whether I’d read it before. Essentially, we’ve all read it before.

But when these same stories were transferred to the screen, the mechanisms of suspense could strike fear in the viewer, and the tensions could grow almost unbearable. The detective story on the screen be- came a thriller in a much fuller sense than it had been on the page, and the ending of the movie wasn’t like shutting a hook. The physical sensations that were stirred up weren’t settled; even if we felt cheated, we were still turned on. We left the theater in a state of mixed exhilaration and excitement, and the fear and guilt went with us. In our dreams, we were menaced, and perhaps became furtive murderers. It is said that in periods of rampant horrors readers and moviegoers like to experience imaginary horrors, which can be resolved and neatly put away. I think it’s more likely that in the current craze for horror films like Night of the Living Dead and Sisters the audience wants an intensive dose of the fear sickness — not to confront fear and have it conquered but to feel that crazy, inexplicable delight that children get out of terrifying stories that give them bad dreams. A flesh-crawler that affects as many senses as a horror movie can doesn’t end with the neat fake solution. We are always aware that the solution will not really explain the terror we’ve felt; the forces of madness are never laid to rest.

Suppose that through the medium of the movies pulp, with its fìve-and-dime myths, can take a stronger hold on people’s imaginations than art, because it doesn’t affect the conscious imagination, the way a great novel does, but the private, hidden imagination, the primitive fantasy life — and with an immediacy that leaves no room for thought. I have had more mail from adolescents (and post- adolescents) who were badly upset because of a passing derogatory remark I made about Rosemary’s Baby than I would ever get if I mocked Tolstoy. Those adolescents think Rosemary’s Baby is great because it upsets them. And I suspect that people are reluctant to say goodbye to the old sweet bull of the Bogart Marlowe because it satisfies a deep need. They’ve been accepting the I-look-out-for-No. 1 tough guys of recent films, but maybe they’re scared to laugh at Gould’s out-of-it Marlowe because that would lose them their Bogart icon. At the moment, the shared pop culture of the audience may be all that people feel they have left. The negative reviews kept insisting that Altman’s movie had nothing to do with Chandler’s novel and that Elliott Gould wasn’t Marlowe. People still want to believe that Galahad is alive and well in Los Angeles — biding his time, per- haps, until movies are once again “like they used to be.

The jacked-up romanticism of movies like those featuring Shaft, the black Marlowe, may be so exciting it makes what we’ve always considered the imaginative artists seem dull and boring. Yet there is another process at work, too: the executive producers and their hacks are still trying to find ways to make the old formulas work, but the gifted filmmakers are driven to go beyond pulp and to bring into movies the qualities of imagination that have gone into the other arts. Sometimes, like Robert Altman, they do it even when they’re working on pulp material. Altman’s isn’t a pulp sensibility. Chandler’s, for all his talent, was.

The New Yorker , October 22, 1973

- More: Movie reviews , Pauline Kael , Robert Altman , The Long Goodbye (film)

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

From Blancanieves to Robot Dreams: Why Pablo Berger’s Animation is a Must-See

Review: Robot Dreams skips dialogue for a beautiful story of a dog and robot’s bond. A heartwarming & unforgettable film.

Até que a Música Pare (Until the Music is Over, 2023) | Review

Cristiane Oliveira’s ‘Até que a Música Pare’ blends loss, love, and cultural heritage into a narrative that captivates and heals.

The Teachers’ Lounge: A Haunting Look at Modern Education | Review

“The Teachers’ Lounge” is a thriller where an idealistic teacher clashes with suspicion & discrimination in a German school.

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire | Review of Adam Wingard’s Film

The film is the fifth feature in the MonsterVerse, bringing the two most iconic titans of cinema back to the big screen

Weekly Magazine

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Long Goodbye

By Pauline Kael

Raymond Chandler’s sentimental foolishness is the taking-off place for Robert Altman’s heady, whirling sideshow of a movie, set in the early-seventies L.A. of the stoned sensibility. Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) is a wryly forlorn knight, just slogging along; still driving a 1948 Lincoln Continental and trying to behave like Bogart, he’s the gallant fool in a corrupt world—the innocent eye. Even the police know more about the case he’s involved in than he does. Yet he’s the only one who cares . Altman tells a detective story all right, but he does it through a spree—a highflying rap on Chandler and L.A. and the movies. Altman gracefully kisses off the private-eye form in soft, mellow color and volatile images; the cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond is responsible for the offhand visual pyrotechnics (the imagery has great vitality). Gould gives a loose and woolly, strikingly original performance. Nina Van Pallandt, Sterling Hayden, Mark Rydell, and Jim Bouton co-star; the script is credited to Leigh Brackett, but when you hear the Altman-style improvisatory dialogue you know you can’t take that too literally. Released in 1973. (Museum of the Moving Image; April 23)

Flickering Myth

Geek Culture | Movies, TV, Comic Books & Video Games

Movie Review – The Long Goodbye (1973)

April 27, 2015 by Simon Columb

The Long Goodbye , 1973.

Directed by Robert Altman. Starring Elliott Gould, Nina van Pallandt and Sterling Hayden.

Private investigator Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) is asked by his old pal Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) for a ride to Mexico. He obliges, and when he returns to Los Angeles is questioned by police about the death of Terry’s wife…

The cat. A feature of many memorable moments in cinema. Alien and Inside Llewyn Davis immediately come to mind. The tabby-cat seen in The Long Goodbye joins the ranks of unforgettable feline friends. Our introduction to Elliot Gould’s mumbling, loner Private Investigator Philip Marlowe is, as he’s woken at 3am, by his meowing, hungry, cat. Interestingly, in the source novel, Marlowe has no pets. Roger Ebert explains that this disposable sequence “establishes Marlowe as a man who is more loyal to his cat than anyone is to him”. Clearly, The Long Goodbye is an unusual, innovative take on the detective drama.

Based on Raymond Chandler’s novel of the same name, The Long Goodbye relocates Marlowe from 1953 to 1973. He may drive the same car, but he’s past his sell-by date. He mumbles and stumbles his way into frame. He struggles to make a sentence. He has barely any friends. In fact, the one buddy he does have, Lennox (Jim Bouton), needs to escape town – and Marlowe dutifully helps. Upon his return, things have changed. For one, his cat is missing. The cops are swiftly on his case, and their questioning presents a resentment that dates much further back. His new case, involving a missing drunken, abusive writer Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden) and his flowing-dress wearing, young-wife Eileen (Nina van Pallandt) reveals that his Mexico-escapin’ mate may have left a few stones unturned on his departure. Finally, enter Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell), a gangster with Arnie Schwarzenegger (literally in an uncredited cameo) as a hench man, who wants money stolen by Lennox, back. This is more than a P.I. investigation, and as his neighbours blissfully (and nakedly) meditate their way through life, Philip Marlowe wants justice – and he wants Lennox cleared for the crime of murder.

But the plot is secondary. Akin to Tarantino’s Jackie Brown or Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice , it’s nice to leisurely hang out with Marlowe. Everyone else has a purpose, but Marlowe has to change and adapt as the story unfolds. The Wade’s are first merely clients, then they are connected to Lennox’s disappearance and Marty’s racket too. He’ll reluctantly change and adapt (as Altman adapted the story by twenty years) but Marlowe resents the world he lives within. It’s dirty and unkempt, much like Elliot Gould’s portrayal and Marlowe’s apartment.

The Long Goodbye asks the titular question as to whose goodbye it is. Terry Lennox? He leaves for Tijuana, and creates this storm in L.A’s teacup. Or perhaps it is the victim of suicide midway through, whose demons have haunted him for too long. Or, of course, it could be Marlowe. Seemingly tired of this life and simply attempting to bid adieu properly, to the slippery friend he transported to Mexico. It is not a film whereby you’ll connect all the dots. Maybe you will the next time. It’s a film that’s as beguiling as The Third Man (with a clear homage in the final moments), but as cool as the beach-bathed LA natives. Going back to Ebert’s review, it is worth noting that initially he graded the film a mediocre 3/5, and promoted it to 5/5 when including it in his ‘Great Movies’ series. This is not a criticism of Roger at all, but a warning to new viewers. The first watch may be tricky to grab a firm hold of. But afterwards, it’ll linger and stick and drag you back. And that’s “alright with me”.

The Long Goodbye was screened at the BFI as the BFI Members pick. You can vote for the months ahead by clicking here and can book tickets for films at the BFI Southbank by clicking here .

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Simon Columb – Follow me on Twitter

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

Wednesday Season 2: What to Expect as Jenna Ortega Promises More Explosive New Season

Action movies blessed with stunning cinematography, ten essential korean cinema gems, the most shocking movies of the 1970s.

Philip K. Dick & Hollywood: The Essential Movie Adaptations

The Gruesome Brilliance of 1980s Italian Horror

Seven Famous Cursed Movie Productions

Lawmen: Bass Reeves: What the TV Show Doesn’t Say About the Real Bass Reeves

10 Essential Films From 1994

The Best 90s and 00s Horror Movies That Rotten Tomatoes Hates!

- Comic Books

- Video Games

- Toys & Collectibles

- Articles and Opinions

- About Flickering Myth

- Write for Flickering Myth

- Advertise on Flickering Myth

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

The Long Goodbye Review

12 Oct 1973

110 minutes

Long Goodbye, The

Robert Altman's languid, free-form version of Raymond Chandler's novel subtly critiques the values of Philip Marlowe, played by an unshaven, chain-smoking Elliott Gould as an all-time loser, introduced in a brilliant sequence that has him try to pass off inferior pet food on his supercilious cat. Shambling through the remains of Chandler's plot, Gould tries to help an alcoholic writer (Sterling Hayden) and clear his only friend of a murder rap.

Many individual sequences are astonishing: violent gangster Mark Rydell smashing a bottle in his mistress' face ("That's someone I love, you I don't even like"), Hayden's stumbling suicide, and an invigoratingly cynical punch line that turns Marlowe into some sort of winner after all. This release is letterboxed; a major bonus since Altman as usual makes sure a lot of the action is happening almost unnoticed in the corners of the frame.

- If this is your first visit, be sure to check out the FAQ by clicking the link above. You may have to register before you can post: click the register link above to proceed. To start viewing messages, select the forum that you want to visit from the selection below.

Announcement

The long goodbye (kino lorber) blu-ray review.

- Published: 02-08-2022, 09:32 AM

article_tags

- album review (218)

- album reviews (274)

- arrow video (271)

- blu-ray (3225)

- blu-ray review (4144)

- comic books (1392)

- comic reviews (872)

- comics (988)

- dark horse comics (484)

- dvd and blu-ray reviews a-f (1969)

- DVD And Blu-ray Reviews G-M (1711)

- DVD And Blu-ray Reviews N-S (1757)

- DVD And Blu-ray Reviews T-Z (878)

- dvd review (2512)

- idw publishing (216)

- image comics (207)

- kino lorber (385)

- movie news (260)

- review (318)

- scream factory (279)

- severin films (296)

- shout! factory (537)

- twilight time (269)

- twilight time releasing (231)

- vinegar syndrome (497)

Latest Articles

- Channel: Movies

Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Trivia & Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

Movies / TV

No results found.

- What's the Tomatometer®?

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening this week

- Top box office

- Coming soon to theaters

- Certified fresh movies

Movies at home

- Netflix streaming

- Prime Video

- Most popular streaming movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- Love Lies Bleeding Link to Love Lies Bleeding

- Problemista Link to Problemista

- Late Night with the Devil Link to Late Night with the Devil

New TV Tonight

- Mary & George: Season 1

- Star Trek: Discovery: Season 5

- Sugar: Season 1

- American Horror Story: Season 12

- Loot: Season 2

- Parish: Season 1

- Ripley: Season 1

- Lopez vs Lopez: Season 2

- The Magic Prank Show With Justin Willman: Season 1

Most Popular TV on RT

- 3 Body Problem: Season 1

- A Gentleman in Moscow: Season 1

- Shōgun: Season 1

- We Were the Lucky Ones: Season 1

- The Gentlemen: Season 1

- Palm Royale: Season 1

- Manhunt: Season 1

- X-Men '97: Season 1

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

- TV & Streaming News

Certified fresh pick

- We Were the Lucky Ones Link to We Were the Lucky Ones

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

Pedro Pascal Movies and Series Ranked by Tomatometer

Dwayne Johnson Movies Ranked by Tomatometer

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Awards Tour

Free Movies Online: 100 Fresh Movies to Watch Online For Free

TV Premiere Dates 2024

- Trending on RT

- Godzilla X Kong: The New Empire

- Play Movie Trivia

Long Goodbye Reviews

No All Critics reviews for Long Goodbye.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

A film noir adaptation of Raymond Chandler's novel, directed by Robert Altman and starring Elliott Gould as Philip Marlowe, a private eye who investigates a murder mystery involving a rich playboy, a writer, and a gangster. The reviewer praises the film's whimsy, spontaneity, and narrative perversity, and criticizes its changes from the original novel.

Movie Info. Private detective Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) is asked by his old buddy Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) for a ride to Mexico. He obliges, and when he gets back to Los Angeles is ...

Powered by JustWatch. Robert Altman 's "The Long Goodbye" attempts to do a very interesting thing. It tries to be all genre and no story, and it almost works. It makes no serious effort to reproduce the Raymond Chandler detective novel it's based on; instead, it just takes all the characters out of that novel and lets them stew together ...

The Long Goodbye is not just classic Altman, classic neo-Noir, and classic satire, it's one of the best and most underrated films of the 1970s. Full Review | Original Score: A | Dec 21, 2021. The ...

When Robert Altman made a movie of the novel Chandler considered his best, "The Long Goodbye," Marlowe, played by Elliott Gould, seemed at first glance almost unrecognizable as the character ...

On March 7, 1973, Robert Altman unveiled his two-hour, R-rated noir adaptation of The Long Goodbye in theaters. The Hollywood Reporter's original review of the United Artists film is below.

The Long Goodbye is a fine transition in style to Altmans later films like "Nashville" and "A Wedding" Elliot Gould does an outstanding job portraying the outre detective Phillip Marlowe, using his mumbling, bumbling, smart ass speaking style, as a technique to keep the film under the illusion that everything is in motion, like the ocean waves ...

The Long Goodbye: Directed by Robert Altman. With Elliott Gould, Nina van Pallandt, Sterling Hayden, Mark Rydell. Private investigator Philip Marlowe helps a friend out of a jam, but in doing so gets implicated in his wife's murder.

The Long Goodbye is a 1973 American satirical neo-noir film directed by Robert Altman and written by Leigh Brackett, based on Raymond Chandler's 1953 novel.The film stars Elliott Gould as Philip Marlowe and features Sterling Hayden, Nina Van Pallandt, Jim Bouton, Mark Rydell, and an early, uncredited appearance by Arnold Schwarzenegger.. The story's setting was moved from the 1940s to 1970s ...

Sterling Hayden is typically intimidating as an alcoholic writer, and Arnold Schwarzenegger pops up in a wordless cameo as a mustachioed henchman. Some of the improvisational scenes don't ...

1 h 52 m. Summary Private investigator Philip Marlowe helps a friend out of a jam then gets implicated in his wife's murder. Comedy. Crime. Drama. Mystery. Thriller. Directed By: Robert Altman. Written By: Leigh Brackett, Raymond Chandler.

Robert Altman's cult classic 70s adaptation of arguably author Raymond Chandler's best novel, The Long Goodbye, is an underrated and oftentimes underappreciated work of art from the late, great auteur. Altman suffered heavy criticism for his updating of the classic Marlowe tale to a modern day setting, regardless of the fact that, in spite of ...

April 14, 2021. Robert Altman's The Long Goodbye is one of the best films of the 1970s—maybe the best—and one of the most influential. That last part is ironic, in a way Altman would have appreciated, because there's no way it can be in any legitimate sense true. Altman and Kubrick created films that came from such an intricate and ...

The Long Goodbye (1973) Reviewed by Michael Thomson. Updated 8 January 2001. When "The Long Goodbye" was first released, Raymond Chandler fans dropped their jaws at what they perceived as an utter ...

Locked in the conventions of pulp writing, Raymond Chandler never found a way of dealing with that malaise. But Robert Altman does, in The Long Goodbye, based on Chandler's 1953 Los Angeles-set novel. The movie is set in the same city twenty years later; this isn't just a matter of the private-detective hero's prices going from twenty ...

The Long Goodbye Raymond Chandler's sentimental foolishness is the taking-off place for Robert Altman's heady, whirling sideshow of a movie, set in the early-seventies L.A. of the stoned ...

The Long Goodbye, 1973. Directed by Robert Altman. Starring Elliott Gould, Nina van Pallandt and Sterling Hayden. SYNOPSIS: Private investigator Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) is asked by his old ...

After his release, he's asked to help a glamorous blonde wife find her husband, but Marlowe becomes more and more warey as he realises the blonde may have a connection to Lennox and his dead wife ...

Reviewing arguably the pioneer of neo-noir! and another 70s Altman film!Link to Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/join/themisfitpond?🎬 Welcome to The Misfit ...

The Long Goodbye - Movie Review: Based on the novel of the same name and directed by Robert Altman in 1973, The Long Goodbye opens in the Los Angeles apartment of private investigator Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould). Woken up in the middle of the night by his cat, Marlowe is soon paid a visit by his friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) who is ...

Tarzan the Ape Man (1981) November 28, 2018. Frozen (2013)

Gray & Special Guests give a Movie Review of THE LONG GOODBYE (1973). Directed by Robert Altman and based on Raymond Chandler's 1953 novel. The screenplay wa...

The Long Goodbye is a 1973 American neo-noir satirical mystery crime thriller film directed by Robert Altman and based on Raymond Chandler's 1953 novel. The ...

Rotten Tomatoes, home of the Tomatometer, is the most trusted measurement of quality for Movies & TV. The definitive site for Reviews, Trailers, Showtimes, and Tickets