The Five Stages of Team Development: A Case Study

Team Building | By Gina Abudi | Read time minutes

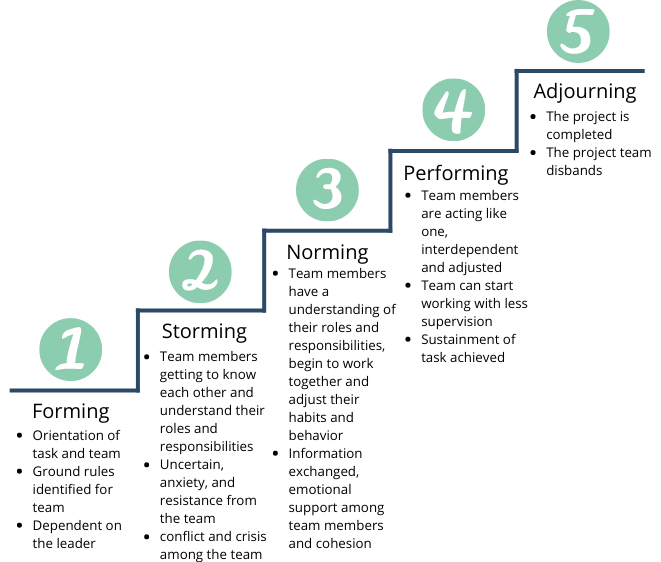

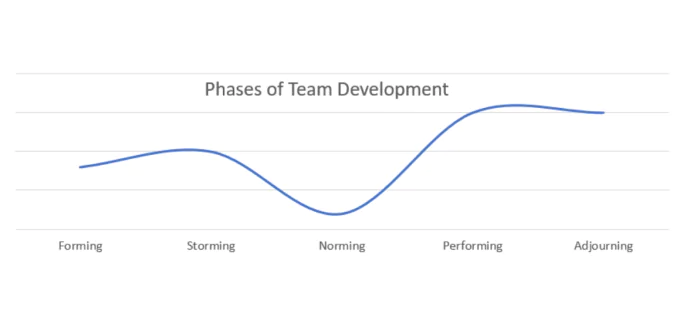

Every team goes through the five stages of team development. First, some background on team development. The first four stages of team growth were first developed by Bruce Wayne Tuckman and published in 1965.

His theory, called "Tuckman's Stages" was based on research he conducted on team dynamics. He believed (as is a common belief today) that these stages are inevitable in order for a team to grow to the point where they are functioning effectively together and delivering high quality results.

In 1977, Tuckman, jointly with Mary Ann Jensen, added a fifth stage to the 4 stages: "Adjourning." The adjourning stage is when the team is completing the current project. They will be joining other teams and moving on to other work in the near future. For a high performing team, the end of a project brings on feelings of sadness as the team members have effectively become as one and now are going their separate ways.

The five stages:

Stage 1: Forming

Stage 2: storming, stage 3: norming, stage 4: performing, stage 5: adjourning.

This article provides background on each stage and an example of a team going through all five stages.

The "forming" stage takes place when the team first meets each other. In this first meeting, team members are introduced to each. They share information about their backgrounds, interests and experience and form first impressions of each other. They learn about the project they will be working on, discuss the project's objectives/goals and start to think about what role they will play on the project team. They are not yet working on the project. They are, effectively, "feeling each other out" and finding their way around how they might work together.

During this initial stage of team growth, it is important for the team leader to be very clear about team goals and provide clear direction regarding the project. The team leader should ensure that all of the members are involved in determining team roles and responsibilities and should work with the team to help them establish how they will work together ("team norms"). The team is dependent on the team leader to guide them.

As the team begins to work together, they move into the "storming" stage. This stage is not avoidable; every team - most especially a new team who has never worked together before - goes through this part of developing as a team. In this stage, the team members compete with each other for status and for acceptance of their ideas. They have different opinions on what should be done and how it should be done - which causes conflict within the team. As they go progress through this stage, with the guidance of the team leader, they learn how to solve problems together, function both independently and together as a team, and settle into roles and responsibilities on the team. For team members who do not like conflict, this is a difficult stage to go through.

The team leader needs to be adept at facilitating the team through this stage - ensuring the team members learn to listen to each other and respect their differences and ideas. This includes not allowing any one team member to control all conversations and to facilitate contributions from all members of the team. The team leader will need to coach some team members to be more assertive and other team members on how to be more effective listeners.

This stage will come to a closure when the team becomes more accepting of each other and learns how to work together for the good of the project. At this point, the team leader should start transitioning some decision making to the team to allow them more independence, but still stay involved to resolve any conflicts as quickly as possible.

Some teams, however, do not move beyond this stage and the entire project is spent in conflict and low morale and motivation, making it difficult to get the project completed. Usually teams comprised of members who are professionally immature will have a difficult time getting past this stage.

When the team moves into the "norming" stage, they are beginning to work more effectively as a team. They are no longer focused on their individual goals, but rather are focused on developing a way of working together (processes and procedures). They respect each other's opinions and value their differences. They begin to see the value in those differences on the team. Working together as a team seems more natural. In this stage, the team has agreed on their team rules for working together, how they will share information and resolve team conflict, and what tools and processes they will use to get the job done. The team members begin to trust each other and actively seek each other out for assistance and input. Rather than compete against each other, they are now helping each other to work toward a common goal. The team members also start to make significant progress on the project as they begin working together more effectively.

In this stage, the team leader may not be as involved in decision making and problem solving since the team members are working better together and can take on more responsibility in these areas. The team has greater self-direction and is able to resolve issues and conflict as a group. On occasion, however, the team leader may step in to move things along if the team gets stuck. The team leader should always ensure that the team members are working collaboratively and may begin to function as a coach to the members of the team.

In the "performing" stage, teams are functioning at a very high level. The focus is on reaching the goal as a group. The team members have gotten to know each other, trust each other and rely on each other.

Not every team makes it to this level of team growth; some teams stop at Stage 3: Norming. The highly performing team functions without oversight and the members have become interdependent. The team is highly motivated to get the job done. They can make decisions and problem solve quickly and effectively. When they disagree, the team members can work through it and come to consensus without interrupting the project's progress. If there needs to be a change in team processes - the team will come to agreement on changing processes on their own without reliance on the team leader.

In this stage, the team leader is not involved in decision making, problem solving or other such activities involving the day-to-day work of the team. The team members work effectively as a group and do not need the oversight that is required at the other stages. The team leader will continue to monitor the progress of the team and celebrate milestone achievements with the team to continue to build team camaraderie. The team leader will also serve as the gateway when decisions need to be reached at a higher level within the organisation.

Even in this stage, there is a possibility that the team may revert back to another stage. For example, it is possible for the team to revert back to the "storming" stage if one of the members starts working independently. Or, the team could revert back to the "forming" stage if a new member joins the team. If there are significant changes that throw a wrench into the works, it is possible for the team to revert back to an earlier stage until they are able to manage through the change.

In the "adjourning" stage the project is coming to an end and the team members are moving off into different directions. This stage looks at the team from the perspective of the well-being of the team rather than from the perspective of managing a team through the original four stages of team growth.

The team leader should ensure that there is time for the team to celebrate the success of the project and capture best practices for future use. (Or, if it was not a successful project - to evaluate what happened and capture lessons learned for future projects). This also provides the team the opportunity to say good-bye to each other and wish each other luck as they pursue their next endeavour. It is likely that any group that reached Stage 4: Performing will keep in touch with each other as they have become a very close knit group and there will be sadness at separating and moving on to other projects independently.

Is the Team Effective or Not?

There are various indicators of whether a team is working effectively together as a group. The characteristics of effective, successful teams include:

- Clear communication among all members

- Regular brainstorming session with all members participating

- Consensus among team members

- Problem solving done by the group

- Commitment to the project and the other team members

- Regular team meetings are effective and inclusive

- Timely hand off from team members to others to ensure the project keeps moving in the right direction

- Positive, supportive working relationships among all team members

Teams that are not working effectively together will display the characteristics listed below. The team leader will need to be actively involved with such teams. The sooner the team leader addresses issues and helps the team move to a more effective way of working together, the more likely the project is to end successfully.

- Lack of communication among team members

- No clear roles and responsibilities for team members

- Team members "throw work over the wall" to other team members, with lack of concern for timelines or work quality

- Team members work alone, rarely sharing information and offering assistance

- Team members blame others for what goes wrong, no one accepts responsibility

- Team members do not support others on the team

- Team members are frequently absent thereby causing slippage in the timeline and additional work for their team members

Example of a Team Moving Through the Five Stages

Background and team members.

A team has been pulled together from various parts of a large service organisation to work on a new process improvement project that is needed to improve how the company manages and supports its client base. The team lead on this project is Sandra from the Chicago office who has 15 years experience as a project manager/team lead managing process improvement projects.

The other members of the team include:

- Peter: 10 years experience on various types of projects, expertise in scheduling and budget control (office location: San Diego)

- Sarah: 5 years experience as an individual contributor on projects, strong programming background, some experience developing databases (office location: Chicago)

- Mohammed: 8 years experience working on various projects, expertise in earned value management, stakeholder analysis and problem solving (office location: New York)

- Donna: 2 years experience as an individual contributor on projects (office location: New York)

- Ameya: 7 years experience on process improvement projects, background in developing databases, expertise in earned value management (office location: San Diego)

Sandra has worked on projects with Sarah and Mohammed, but has never worked with the others. Donna has worked with Mohammed. No one else has worked with other members of this team. Sandra has been given a very tight deadline to get this project completed.

Sandra has decided that it would be best if the team met face-to-face initially, even though they will be working virtually for the project. She has arranged a meeting at the New York office (company headquarters) for the entire team. They will spend 2 days getting introduced to each other and learning about the project.

The Initial Meeting (Stage 1: Forming)

The day of the face-to-face meeting in New York has arrived. All team members are present. The agenda includes:

- Personal introductions

- Team building exercises

- Information about the process improvement project

- Discussion around team roles and responsibilities

- Discussion around team norms for working together

- Introduction on how to use the SharePoint site that will be used for this project to share ideas, brainstorm, store project documentation, etc

The team members are very excited to meet each other. Each of them has heard of one another, although they have not worked together as a team before. They believe they each bring value to this project. The team building exercises have gone well; everyone participated and seemed to enjoy the exercises. While there was some discussion around roles and responsibilities - with team members vying for "key" positions on the team - overall there was agreement on what needed to get done and who was responsible for particular components of the project.

The onsite meeting is going well. The team members are getting to know each other and have been discussing their personal lives outside of work - hobbies, family, etc. Sandra is thinking that this is a great sign that they will get along well - they are engaged with each other and genuinely seem to like each other!

The Project Work Begins (Stage 2: Storming)

The team members have gone back to their home offices and are beginning work on their project. They are interacting via the SharePoint site and the project is off to a good start. And then the arguments begin.

Peter has put up the project schedule based on conversations with only Mohammed and Ameya on the team. Donna and Sarah feel as if their input to the schedule was not considered. They believe because they are more junior on the team, Peter has completely disregarded their concerns about the timeline for the project. They challenged Peter's schedule, stating that it was impossible to achieve and was setting up the team for failure. At the same time, Sarah was arguing with Ameya over who should lead the database design and development effort for this project. While Sarah acknowledges that Ameya has a few years more experience than she does in database development, she only agreed to be on this project in order to take a lead role and develop her skills further so she could advance at the company. If she knew Ameya was going to be the lead she wouldn't have bothered joining this project team. Additionally, Mohammed appears to be off and running on his own, not keeping the others apprised of progress nor keeping his information up to date on the SharePoint site. No one really knows what he has been working on or how much progress is being made.

Sandra had initially taken a side role during these exchanges, hoping that the team would work it out for themselves. However, she understands from past experience managing many project teams that it is important for her to take control and guide the team through this difficult time. She convenes all of the team members for a virtual meeting to reiterate their roles and responsibilities (which were agreed to in the kick-off meeting) and to ensure that they understand the goals and objectives of the project. She made some decisions since the team couldn't come to agreement. She determined that Ameya would lead the database development design component of the project, working closely with Sarah so she can develop further experience in this area. She reviewed the schedule that Peter created with the team, making adjustments where necessary to address the concerns of Donna and Sarah. She reminded Mohammed that this is a team effort and he needs to work closely with the others on the team.

During the virtual meeting session, Sandra referred back to the ground rules the team set in their face-to-face meeting and worked with the team to ensure that there was a plan in place for how decisions are made on the team and who has responsibility for making decisions.

Over the next few weeks, Sandra noticed that arguments/disagreements were at a minimum and when they did occur, they were worked out quickly, by the team, without her involvement being necessary. Still, she monitored how things were going and held regular virtual meetings to ensure the team was moving in the right direction. On a monthly basis, Sandra brings the team together for a face-to-face meeting. As the working relationships of the team members started improving, Sandra started seeing significant progress on the project.

All is Going Smoothly (Stage 3: Norming)

The team has now been working together for nearly 3 months. There is definitely a sense of teamwork among the group. There are few arguments and disagreements that can't be resolved among the team. They support each other on the project - problem solving issues, making decisions as a team, sharing information and ensuring that the ground rules put in place for the team are followed.

Additionally, the team members are helping each other to grow and develop their skills. For example, Ameya has worked closely with Sarah to teach her many of the skills he has learned in database design and development and she has been able to take the lead on accomplishing some of the components of their aspect of the project.

Overall, the team members are becoming friends. They enjoy each other's company - both while working on the project and after hours via communicating on email, via instant messaging, on Twitter, or over the telephone.

Significant Progress is Made! (Stage 4: Performing)

The team is now considered a "high performing team." It wasn't easy getting to this stage but they made it! They are working effectively as a group - supporting each other and relying on the group as a whole to make decisions on the project. They can brainstorm effectively to solve problems and are highly motivated to reach the end goal as a group. When there is conflict on the team - such as a disagreement on how to go about accomplishing a task - the group is able to work it out on their own without relying on the team leader to intervene and make decisions for them. The more junior members - Donna and Sarah - have really developed their skills with the support and help of the others. They have taken on leadership roles for some components of the project.

Sandra checks in with the team - praising them for their hard work and their progress. The team celebrates the milestones reached along the way. When necessary, Sandra provides a link from the team to the executives for decisions that need to come from higher up or when additional support is needed.

The project is on time and within budget. Milestones are being met - some are even ahead of schedule. The team is pleased with how well the project is going along, as is Sandra and the executives of the organisation.

Time to Wrap Up (Stage 5: Adjourning)

The project has ended. It was a huge success! The internal customer is pleased and there is definitely an improvement in how the company supports its clients. It has been a great 8 months working together…with some ups and downs of course. Each of the individuals on the project will be moving to other projects within the organisation, but no one is going to be on the same project. They will miss working with each other but have vowed to remain friends and keep in touch on a personal level - hopefully to work together again soon!

The team has gotten together in the New York office to discuss the project, including documenting best practices and discussing what worked effectively and what they would improve upon given the chance to do it again. Sandra has taken the team out to dinner. They are joined by the project sponsor and some other executives who are extremely pleased with the end result.

This is a simplistic view of a team working through the five stages of team development. I hope it provides some benefit to you.

Remember that at any time this team could revert back to a previous stage. Let's assume that another individual joins the team - the team will revert back to the "forming" stage as they learn how to work with the new team member; reestablishing team guidelines, finding their way again, and learning how to work cohesively as a team. Or, let's assume that Mohammed slips back into his old ways of keeping to himself and not sharing information with the team - this may cause the team to revert back to the "storming" stage.

It is important to remember that every team - regardless of what the team is working on - will follow these stages of team development. It is the job of the team leader to help see the team through these stages; to bring them to the point where they are working as effectively as possible toward a common goal.

- The Team Handbook, 3rd Edition (Scholtes, Joiner, Streibel), Publisher: Oriel

- Managing the Project Team (Vijay Verma), Publisher: PMI

Gina Abudi has over 15 years consulting experience in a variety of areas, including project management, process management, leadership development, succession planning, high potential programmes, talent optimisation and development of strategic learning and development programmes. She has been honoured by PMI as one of the Power 50 and has served as Chair of PMI's Global Corporate Council Leadership Team. She has presented at various conferences on topics ranging from general management and leadership topics to project management. Gina received her MBA from Simmons Graduate School of Management.

Copyright © 2009-2010 Gina Abudi. All rights reserved.

What's Next?

You may also be interested in, is your project proposal ready.

- The mnemonic READY is useful when creating a project proposal. It will help you produce a project proposal that's difficult to ignore.

8 Common Reasons Software Projects Fail and How to Succeed

- Unsatisfactory project results have become an IT industry norm. It's time to address the critical reasons software projects fail.

17 Must Ask Questions for Planning Successful Projects

- Why do some projects proceed without a hitch, yet others flounder? One reason may be the type and quality of the questions people ask at the very start.

Undertaking a Successful Project Audit

- A project audit provides an opportunity to uncover issues, concerns and challenges encountered during the project lifecycle.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Workplace Health Group: A Case Study of 20 Years of Multidisciplinary Research

Nicholas j. haynes.

Department of Psychology, University of Georgia

Robert J. Vandenberg

Department of Management, University of Georgia

David M. DeJoy

Department of Health Promotion & Behavior, University of Georgia

Mark G. Wilson

Heather m. padilla, heather s. zuercher, melissa m. robertson.

Owens Institute of Behavioral Research, University of Georgia

The Workplace Health Group (WHG) was established in 1998 to conduct research on worker health and safety and organizational effectiveness. This multidisciplinary team includes researchers with backgrounds in psychology, health promotion and behavior, and intervention design, implementation, and evaluation. The article begins with a brief history of the team, its guiding principles, and stages of team formation and development. This section provides examples of the roles team composition, structure, processes, cognition, leadership, and climate played in the various stages of team development, as well as how they influenced team effectiveness. The WHG formed with functional diversity—variety in knowledge, skills, and abilities—in mind and the impact of this diversity is discussed throughout the article. Illustrations of how the functional diversity of the WHG has led to real-world impact are provided. The article concludes with some lessons learned and recommendations for creating and sustaining multidisciplinary teams based on the WHG’s 20 years of experience and the team science literature.

Work plays a central role in most people’s lives—for the average individual, about half of all waking hours are spent at work. Work influences where we live, whom we associate with, our health, and our quality of life. However, the American workforce faces considerable challenges associated with poor health, safety concerns, and lack of productivity. For example, nearly 30% of American workers are obese ( Luckhaupt, Cohen, Li, & Calvert, 2014 ), incurring substantial indirect costs for organizations associated with absenteeism, reduced productivity at work, insurance claims, disability, and premature mortality ( Goettler, Gross, & Sonntag, 2017 ). From 2003–2010, over 42,000 U.S. workers were fatally injured at work, with associated costs exceeding $44 billion ( The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 2017 ). In 2016, 2.9 million workplace injuries and illnesses were reported by private employers, nearly one-third of which resulted in days away from work ( Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017 ).

These figures indicate a pressing need to address the health, safety, and effectiveness of the nation’s workforce. Yet, addressing these issues is extremely complicated due to physical, behavioral, psychological, social, technological, and sociopolitical factors—internal and external to an organization—that impact the nature and experience of work. The complexity of these issues requires multidisciplinary teams to understand and provide solutions to the real-world problems of worker health, safety, and effectiveness. The Workplace Health Group (WHG) was formed to address these real-world problems.

The WHG is a multidisciplinary research group that conducts research on workplace health, safety, and organizational effectiveness. The core of the group’s work revolves around the vision that healthy people and healthy workplaces are key ingredients of individual and organizational effectiveness and is reflected in the WHG value statement: healthy people + healthy places = healthy organizations. Through its research, the WHG works to understand the many complex links between work, safety, and health and how these impact employees’ quality of life and organizations’ overall effectiveness (financial as well as operational). As an academic group, the WHG’s goals reflect its institution’s mission to conduct impactful research, train students, and provide local and national outreach services. The WHG includes faculty, research staff, and graduate students from a number of disciplines including public health, psychology, management, sociology, human resources, nutrition, and exercise science. It is the intersection of these disciplines that provide the WHG the best opportunity to impact worker health, safety, and effectiveness. By leveraging each member’s expertise, understanding and valuing differences, and focusing on its mission, this multidisciplinary research team has been able to address real-world problems including employee obesity and chronic disease, workplace safety, and the cost effectiveness of employee health and safety initiatives.

A Brief History of the Workplace Health Group: From Forming to Performing

The WHG was founded in 1998; however, the effective team processes characterizing the WHG today did not occur immediately—or automatically—20 years ago when the members first began working together. Rather, it was an evolutionary process fraught with the dysfunctions that new groups commonly face as they go through the small group developmental stages of forming, storming, norming, and performing ( Tuckman & Jensen, 1977 ). Similarly, the group did not scan the extant literature of the day regarding teams and team effectiveness before forming. However, reviewing this literature now, the successes and missteps of the group align with what team science has uncovered. Thus, this article can be viewed as a case study of an effective, long-lasting multidisciplinary team, including recommendations based on the WHG’s 20 years of experience and the team science literature.

Forming The WHG

The forming stage involves the collection of team members as fairly independent agents who have come together to work on some agreed upon goals ( Tuckman & Jensen, 1977 ). The forming stage began in 1998 with the writing of a grant proposal by the second, third, and fourth authors. In terms of team processes, this marked the group’s first transition phase ( Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001 ). Transition phases are defined as, “periods of time when teams focus primarily on evaluation and/or planning activities to guide their accomplishment of a team goal or objective” ( Marks et al., 2001 , p. 360). During this phase, the WHG took part in mission formulation and planning, along with goal and role specification. However, the WHG did not truly begin to function as a team until the grant proposal was funded. This award meant that the group had to seriously consider team structure and processes to deliver on its promises.

The award launched the WHG into their first action phase, or period of completing tasks that contribute directly to goal accomplishment ( Marks et al., 2001 ). These first transition and action phases were characterized by the typical forming stage ( Tuckman & Jensen, 1977 ). Specifically, it was an exciting time during which the WHG began to understand and accept respective roles, hired a grant director, and offered assistantships to PhD students. The WHG emerged structurally as a team during this period; however, the members within it acted more as independent agents than team members.

The WHG was formed with diversity in expertise in mind. Functional diversity refers to team members differing in knowledge, skills, ability, educational background, and the roles they play within the team ( Milliken, Bartel, & Kurtzberg, 2003 ). One of the predominant means to addressing the effects of functional diversity on team performance is the information and decision-making perspective ( van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007 ; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998 ). According to this perspective, the variety in group composition has a direct, positive impact on group performance ( Williams & O’Reilly, 1998 ). Functional diversity gives the team a rich pool of resources to draw upon that facilitates the accomplishment of tasks toward team goals ( van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007 ). In short, the positive impact on team performance is due to the team providing a range of knowledge to solving problems. Meta-analytic evidence provides support for this perspective, concluding that functional diversity is positively related to team performance ( Bell et al., 2011 ).

Despite the positive effects functional diversity can have on team performance, the WHG soon discovered why functional diversity can be a double-edged sword ( Bunderson & Sutcliffe, 2002 ). Challenges include differences in perspectives from diverse backgrounds in training and methodology ( National Research Council [NRC], 2015 ; Slatin, Galizzi, Melillo, & Mawn, 2004 ), knowledge integration ( Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009 ; NRC, 2015 ), social integration ( Harrison, Price, Gavin, & Florey, 2002 ), high task interdependence ( Mannix & Neale, 2005 ; NRC, 2015 ), role conflict ( Johnson, Nguyen, Groth, & White, 2018 ), task conflict ( Jehn, Northcraft, & Neale, 1999 ), and relationship conflict ( Mohammed & Angell, 2004 ). These challenges pushed the WHG into the next stage of small group development: storming.

Storming The WHG

The storming stage entails team members learning each other’s strengths and weaknesses. As such, interactions in this stage are commonly fraught with conflict due to personality and other individual differences, differences in how individuals approach tasks, negotiating what tasks are completed by whom, and power differences.

For the WHG, the most contentious interactions occurred around topics of what constituted sound scientific practices according to the members’ individual training and experience. Although the second and third authors completed PhD degrees emphasizing social psychology, they were quite dissimilar with respect to their approaches to data analysis. The second author’s research focus on business management was aligned with the I-O psychology tradition of proposing a set of conceptually-driven hypotheses and undertaking analyses to test only those hypotheses (i.e., a priori analyses). The third author’s research focused largely on factors in the workplace that either improved or impeded workplace safety. As such, his approach to data analysis was discovery. The fourth author, on the other hand, was much more qualitatively trained. Needless to say, there were many instances when these viewpoints clashed during meetings or when the analyses requested appeared unreasonable to one or more members. This has been shown to be a common obstacle for multidisciplinary teams ( NRC, 2015 ).

In addition to this primary difference, there were also differences in work styles, approaches to conducting meetings, and approaches to undertaking the tasks. Reflecting back on these early stages of the group, there were several attitudes and processes that exacerbated rather than ameliorated the severity of the storming stage. One challenging attitude during this stage was rigidity in the members’ functional perspectives. For example, the second author recalls that in the early years, he thought nothing of conducting analyses, drawing conclusions from them on his own, and then telling the other members about the outcomes.

The same was true of the other primary members when presenting through their specialized functional lenses. Moreover, there were team processes during this stage that detracted from team effectiveness and the transition into the next stage of group development. Examples of these ineffective processes include irrelevant tangents during meetings, disrespecting boundaries by going around members rather than through them, and bringing on non-core members who were necessary for the task, but did not share the team’s mission and values. That final ineffective process taught the WHG the importance of team member selection on multidisciplinary teams ( NRC, 2015 ). However, membership on academic, multidisciplinary teams is typically voluntary, so frustrated or dissatisfied members often simply withdraw from the team. This begs the question: What kept the WHG together?

Surviving the storm.

The fact that the group was funded to conduct the research and had externally-assigned deadlines provided a practical reason to move through the storming stage. Even if there was disagreement on a decision, the group made a commitment to follow through with the funded project. While practical, the “funding” strategy on its own would not work for 20 years of multidisciplinary research. In addition to this motivation, there were several aspects of team composition, structure, and processes that helped the WHG get through the storming stage.

Regarding the WHG team composition, deep-level composition variables consisting of psychological characteristics, such as personality, values, and attitudes of team members were beneficial during this stage. Each team member at that time had a moderate to high level of agreeableness, which is positively related to team performance ( Bell, 2007 ). The group recalls that, for the most part, everyone was willing to discuss issues objectively and professionally without letting egos get in the way (e.g., avoiding a “this is my idea; I have to defend it” attitude). Additionally, each member had a high level of openness to experience, which Bell’s (2007) meta-analysis also revealed as a strong predictor of team performance. Multidisciplinary teams likely have a relatively high level of openness to experience because joining a multidisciplinary team indicates an openness to other perspectives to solve a common problem.

While the general personality of the group and its members was helpful in surviving the storming stage, the ability to make it through this stage was driven most by the WHG’s shared mission, vision, and values. Harrison et al. (2002) discovered that functional diversity had a significant, negative influence on social integration. However, they also found that outcome importance was the only actual (vs. perceived) deep-level diversity variable that had a significant effect on social integration, which then influenced team performance. In other words, differences in how important the goal was to team members appeared to have the greatest impact on their inability to socially integrate. The WHG members had not only agreed on their mission and its potential value, they all placed a high level of importance on fulfilling that mission, which facilitated social integration.

The group collectively believed (and still believes) that work and health have a complex relationship and that understanding and improving this relationship through research is important. Furthermore, the group believed (and still believes) that conducting real-world, multi-site intervention research requires a multidisciplinary team approach—no single researcher has the time or set of skills necessary to execute a project with total control and independence. Consequently, the shared mission and vision of members of the WHG was a key factor in the group’s social integration and survival of the storming stage. Dose and Klimoski (1999) corroborate these views, proposing that work values affect team formation early on in the process, and similarity in these values leads to cohesiveness, trust, norm development, and effective communication. Finally, these shared values and mission brought satisfaction to the group members. Despite the moments of contention (i.e., storming), the members enjoyed working together; they valued their functional diversity.

Team structure was also important for buffering conflict during this stage. Each member played a specific role, so it was easy to delegate tasks to certain people. This reduced the potential for conflict because it enabled members to focus on their tasks. However, there is an important distinction to be made here between taskwork and teamwork. Taskwork processes are what teams are doing, whereas teamwork processes are how they are doing it with each other. The WHG learned during the storming phase that it is not only taskwork that matters, but how processes and tasks are completed is critical to team effectiveness.

Marks et al. (2001) developed a helpful framework for understanding team processes—validated through meta-analysis ( LePine, Piccolo, Jackson, Mathieu, & Saul, 2008 ). While the transition and action processes were mentioned previously, Marks and colleagues also describe a third type of process: interpersonal processes. Interpersonal processes are processes that are used to manage interpersonal relationships that occur during both transition and action phases. Reflecting on this stage in the WHG’s history, the group can identify processes in each of these three categories that were beneficial to moving the group past the storming stage.

During transition phases, the way in which the group conducted mission analysis, formulation, and planning was helpful for social integration. This process was conducted in an open and participatory manner, where decisions were made collectively, and all members openly shared their opinions. While this process could be viewed as a hindrance to team performance because of its inefficiency, the positive influence it had on social integration far outweighed its potential negative influence, especially during this time of storming. This process allowed all team members to remain informed and involved.

Regarding mission planning, Fisher (2014) distinguishes between taskwork planning and teamwork planning, where taskwork planning includes task-relevant discussion, the development of alternative courses of action for task completion, and goal specification. Teamwork planning encompasses the clarification of roles as well as the identification of member strengths and weaknesses and who knows what necessary information. The teamwork planning that occurred during the forming stage helped with interpersonal processes during the storming stage ( Fisher, 2014 ). These processes assisted the WHG in the beginning stages of team mental model and transactive memory system formation (see below). During the action phase, the action process of monitoring progress toward goals had a positive influence on team accountability during the storming stage. The group set specific deadlines for tasks and were (fairly) good about holding each other accountable to them.

Two interpersonal processes outlined by Marks et al. (2001) were beneficial to the survival of the storming stage: (a) motivation and confidence building, and (b) interpersonal conflict management. Team motivational states include team efficacy and team empowerment ( Chen & Kanfer, 2006 ). During the storming stage, team efficacy and empowerment grew out of continued success in obtaining funding. As the group continued to work together, the members’ confidence in each other’s expertise grew, which increased the team’s efficacy as a whole, and provided motivation to continue despite conflicting individual differences.

In addition to this motivation and confidence building, the team’s interpersonal conflict management strategies were essential for successful transition out of the storming stage. Given that conflict is going to happen in teams, how a team manages that conflict becomes important. DeChurch, Mesmer-Magnus, and Doty (2013) state that, “the truth about team conflict: Conflict processes, that is, how teams interact regarding their differences, are at least as important as conflict states, that is, the source and intensity of their perceived incompatibilities” (p. 559).

Overall, the effective interpersonal conflict management strategies used by the WHG during this time were characteristic of collectivistic team conflict processes (e.g., processes emphasizing openness and collaboration when approaching conflict). Consistent with meta-analytic evidence ( DeChurch et al., 2013 ), the WHG’s experience was that these collectivistic team conflict processes had positive effects on the group’s affect and performance. Most importantly, members’ respect and trust for each other and their expertise was the foundation underlying these effective processes. The WHG had (and still has) a shared respect among group members, which allowed for an attitude of “agree to disagree” on certain points and the ability to set those issues aside and work together as a team ( de Wit, Greer, & Jehn, 2012 ).

The storming stage can be a make-or-break period for multidisciplinary, functionally diverse teams. Success at this stage involves recognizing and opening up to the fact that conflict will occur as interactions deepen and become more frequent over time. Success is also determined, in part, by how the team approaches and manages the imminent conflict. As illustrated by the examples in this section, aspects of team composition, structure, and processes can either help or hurt the team’s ability to survive the storm. Readers are encouraged to examine Table 1 for recommendations for getting through the storming stage—and all other stages—based on the WHG’s experiences and the team science literature.

Recommendations for Each Stage of Small Group Development

Norming The WHG

The norming stage is characterized by acceptance of the differences among team members and focus on accomplishing the team goals ( Tuckman & Jensen, 1977 ). For the WHG, the key factor in ushering in the norming stage was the realization that the group was going to be a long-term entity. After successfully obtaining funding for additional projects over the years, the WHG took on a sense of permanency, which was an important psychological milestone because prior to this period, members sensed that the WHG would end with the completion of the next project. With continual funding came stability and a confidence that the values and goals of the WHG were resonating well with the funding sources.

Important to the norming of the WHG was solidifying the team leadership structure. The WHG leadership is an example of shared or collective leadership. Shared leadership can be defined as a “dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals or both” ( Pearce & Conger, 2002 , p. 1). The WHG leadership structure at the beginning of this stage did incorporate a bit of hierarchy. For example, while everyone was encouraged to share their opinions on a topic, if a consensus could not be reached, the ultimate decision would be deferred to the member with expertise on that topic. The effectiveness of this deferment was rooted in the shared trust and respect discussed above. While the leadership style was and continues to be one of shared leadership, the addition of multiple, often overlapping, research grants and projects necessitated the expansion of the WHG team as well as an adjustment of the leadership structure.

With the expansion of team members and projects, it was no longer efficient to have all members of the WHG meet simultaneously, because projects would often have different principal investigators (PIs) and team members. To account for this change, the WHG formed sub-teams that were project specific and were led by the PI for that project. The expansion and the overlapping nature of the funded projects also led to the need to hire a research director. The research director position was instrumental in creating long-term standardized sets of operating procedures and processes across the projects. Standardizing the processes removed much ambiguity and provided a consistent set of norms under which all members would operate, in addition to further solidifying team member roles.

In terms of team processes, the research director role took the lead on most of the action processes described by Marks et al. (2001) ; namely, monitoring progress toward goals, systems monitoring, and coordination. In terms of the leadership and roles literature, the research director led most of the task leadership functions ( Morgeson, DeRue, & Karam, 2010 ). Specifically, the research director performed the leadership functions of structuring and planning, or coordinating when work should be done (e.g., timing, scheduling, work flow). The WHG leadership structure became necessarily more hierarchical over time with the formation of sub-teams; however, open sharing and collective decision-making characterized each sub-team along with the core team. Advantages of this leadership structure include creating a sense of value within the group and giving everyone a voice, while also taking advantage of the efficiency of sub-teams. Indeed, Carson, Tesluk, and Marrone (2007) found that a shared purpose, social support, and voice were positively related to shared leadership. However, some disadvantages of this type of structure can include creating an opportunity for team members to avoid ownership, and some confusion among new team members regarding who is the “boss” (see Table 2 for WHG role descriptions).

Descriptions of the Workplace Health Group Roles and Responsibilities

Another important process that occurred during the norming stage was the further development of team cognition (e.g., shared mental models and transactive memory systems). Shared mental models represent knowledge that is common among team members, whereas transactive memory systems represent knowledge that is distributed among team members ( DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010 ). As stated earlier, the WHG’s team cognition began to form in the first transition phase, during which the team explored strengths and weaknesses of each member. However, the team cognition at the forming stage was in its infancy and was very limited in scope. During the norming stage, the shared mental models and transactive memory systems expanded, which has been shown to have strong, positive relationships with team behavioral processes, motivational states, and team performance ( DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010 ).

How did the WHG develop their team cognition? In the words of one team member, “meetings…lots of meetings.” However, meetings alone do not guarantee the effective development of team cognition. Rather, what happened during the WHG meetings is what drove the team cognition development process. Specifically, in order to develop team cognition, team members had to share and integrate information (i.e., information sharing and elaboration, respectively). Although evidence suggests that functionally diverse teams are the least likely to share their unique information with each other ( Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009 ), the mutual respect and trust established in the storming stage was key to facilitating information sharing for the WHG by creating a team psychological safety climate.

Team psychological safety climate is defined as a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking, and is characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect, which creates an environment where team members are comfortable being themselves ( Edmondson, 1999 ). Mannix and Neale (2005) observed that diverse teams must create an environment where members are comfortable sharing information to be effective and fully utilize the diversity of the team. During the storming stage, the WHG sought to create an environment of psychological safety where different views could be presented without fear of ridicule or retribution. Through this psychological safety climate, WHG team members were able to take full advantage of information sharing and its positive impact on team performance.

The regularly scheduled WHG meetings were (and are) characterized by relatively high levels of open and unique information sharing, high cooperation, and ample opportunities for each team member to share his or her opinion. These characteristics have all been shown to facilitate team cohesion and satisfaction ( Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009 ). However, to develop team cognition, information does not simply need to be shared, it must also be integrated. Information elaboration involves exchanging information and perspectives (i.e., information sharing), providing feedback to the group, and a discussion and integration of the shared information ( van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004 ). This information elaboration process enables functionally diverse teams to transform and fully utilize their knowledge, skills, and resources into actionable solutions to complex problems ( Resick, Murase, Randall, & DeChurch, 2014 ; van Knippenberg et al., 2004 ). The WHG has found these processes to be beneficial not only to team cognition, but also to team effectiveness.

Performing The WHG

The performing stage is characterized by a high degree of success along several different metrics, driven largely by a participative team culture ( Tuckman & Jensen, 1977 ). The WHG is currently in the performing stage in which its multidisciplinary composition is effectively utilized to not only solve problems on current projects, but also to develop innovative ideas for new grant opportunities. Since 1998, the WHG has achieved continuous external funding (approximately $13 million) from many sources, including NIH, CDC, NIOSH, and FEMA. The WHG successes are also apparent in its 66 peer-reviewed publications, 14 book chapters, and 74 presentations. Regarding application of the WHG’s research to real-world problems, the group has worked with large employers such as Home Depot, Union Pacific Railroad, and Dow Chemical, as well as with governmental employers, including city-country governments, state agencies, and municipal public safety departments in both urban and rural settings.

The diverse composition of the team in terms of function and personality allowed members to bring a collective group of strengths together. For example, one PI is very task-oriented, which helps keep the projects and proposals progressing. Another PI is more conceptual and thoughtful, which is very important in the proposal or project development and troubleshooting phases. Additionally, the WHG continues to improve team processes. The following example illustrates how the WHG currently solves problems and makes decisions through information sharing and elaboration and collective decision-making.

During a recent meeting devoted to the quantitative analyses of aims and hypotheses of the WHG’s current grant, the data analysis sub-team needed to determine whether any primary analyses would be biased by the presence of nesting issues. There were conceptual reasons not to expect the interdependency, but the sub-team wanted to present statistical evidence that this was the case. Most illustrative of the performing stage is the fact that the data analysis sub-team did not want to make this decision on its own. Rather, it wanted to present the conceptual and statistical evidence to all WHG members to get their feedback on the issue.

This differs dramatically from the example given in the storming stage of simply telling others what had been done and expect that the they accept it. Now the data analysis sub-team solicits input by communicating the conceptual and statistical evidence to members in a manner they understand ( Williams & O’Reilly, 1998 ). Therefore, while the sub-team leader couched the general problem to other members in a non-technical manner, most importantly, the PhD student organized and presented the statistical results in a manner such that the less statistically-oriented members could be part of the conversation and the decisions made. The WHG meetings have been conducted in this manner for many years now, regardless of the issues being addressed or decisions being made. While this meeting process makes it difficult to submit numerous proposals quickly, it allows for a fuller integration and extension of the disciplines involved.

A final area that has led to the WHG’s effectiveness is the strengthening of its psychological safety climate. Two points are worth noting about this increase in climate strength: the climate is now both easily recognizable and quickly beneficial to new team members. At the start of 2018, when writing and submitting a new grant proposal, in addition to the primary WHG members, there were two subject matter experts (SMEs) with their own functional knowledge added to the group for purposes of the grant. Both individuals sensed immediately the climate of the WHG and adjusted their conversations in a manner that fit within this climate. After the proposal was submitted, one of those individuals commented that it was the best grant writing experience he has had in over 20 years as a faculty member.

In addition to high satisfaction, the WHG team climate provides a sense of value, belonging, and support to new team members. For example, recently, the WHG had several full-time staff members serving as health coaches on a funded project. Throughout the project, the PIs and research director met with the coaches on a weekly basis to discuss progress and problems. These meetings were designed to facilitate group learning and problem-solving while also creating a supportive environment for the health coaches.

Although the WHG is in the performing stage, continued successful performance requires consistent and sustained effort on the part of all team members. Moreover, the WHG team must continue to actively manage changes in personnel (including changes in the experience and position of personnel) to maintain effectiveness (NRC, 2015). For example, the former research director (the fifth author) recently graduated with her PhD and joined the university as a faculty member; this required team members to adjust their views of her as a staff member who managed the day-to-day details to a co-investigator. Additionally, as PhD students enter, grow in competence, and exit the group, the team needs to adjust its expectations regarding the level of autonomy versus oversight. Ongoing performance is actively facilitated by a flexible and open-minded approach to changes in the various team members and their competencies.

Illustrations of Functional Diversity and Real-World Impact

The diverse knowledge, skills, abilities, educational and experiential backgrounds of the WHG members provide opportunities for each person’s unique experience and expertise to enhance the group’s projects. The group’s basic approach has involved a conscious merger of theories and principles from the behavioral sciences, predominately psychology, with strategies adapted from public health research and practice. Specifically, the WHG blends the methodological and measurement sophistication of the behavioral sciences with the field-based tactics of public health. The WHG has conducted research in several areas, including physical activity in the workplace (e.g., Dishman, DeJoy, Wilson, & Vandenberg, 2009 ), organizational health promotion (e.g., DeJoy & Wilson, 2003 ), firefighter safety (e.g., Smith, Eldridge, & DeJoy, 2016 ), and many others. However, the group’s innovation is perhaps most evident in three of the WHG’s areas of research: healthy work organizations, environmental approaches to weight management, and research translation.

Healthy Work Organization Research

The WHG’s focus on healthy work organization (HWO) coincided with the emergence of integrated programming (e.g., “Total Worker Health” [TWH]). TWH seeks to merge health protection and promotion into a single integrated endeavor to maximize the health, safety, and well-being of workers. In one of the first interventions to focus on changing work organization factors (e.g., work schedules) to improve worker health, safety, and effectiveness, the WHG collaborated with a large, national retailer to test a model of HWO. To successfully design, implement, and evaluate this HWO intervention required expertise in four areas: 1) how work organizations operate, 2) intervention design and implementation, 3) behavioral theory, and 4) advanced methods and statistics.

The second author provided expertise in individual worker adjustment to outline organizational antecedents, mediators, and outcomes associated with the intervention. Moreover, his expertise in high involvement work processes ( Vandenberg, Richardson, & Eastman, 1999 ) as a psychological climate variable provided a primary theoretical framework for the intervention. The third author added to this knowledge with his expertise in occupational health and safety, allowing him to theorize health and safety outcomes and antecedents, such as a safety climate (e.g., DeJoy, Schaffer, Wilson, Vandenberg, & Butts, 2004 ). His expertise in behavioral theories also enabled him to spearhead the application of psychological theories to the design of the intervention. The fourth author, with his expertise in public health intervention creation, implementation, and evaluation, was able to integrate this knowledge together into a cohesive program designed to modify underlying behaviors and environmental conditions, ultimately mitigating the outcomes. Finally, the WHG utilized the second author’s expertise of longitudinal data analysis (e.g., Lance, Vandenberg, & Self, 2000 ) and structural equation modeling (e.g., Williams, Vandenberg, & Edwards, 2009 ) to properly analyze the effectiveness of the intervention. Together, the PIs were able to develop and implement a workplace intervention program that had positive effects on worker health, safety, and effectiveness.

Specifically, this research investigated the effects of the HWO intervention on employee health, financial performance, and organizational climate. The HWO intervention was a team-based, data-driven, problem-solving approach that expanded upon the process proposed by DeJoy and Wilson (2003) . Employee teams that included representatives from all departments and employee levels used work organization data specific to their worksite to create a plan to improve safety and health conditions within their worksite. Compared to control sites, worksites receiving the intervention fared better in terms of organizational climate, psychological work adjustment, perceived health and safety, employee turnover, and sales per hour ( DeJoy, Wilson, Vandenberg, McGrath, & Griffin-Blake, 2010 ).

Environmental Approaches to Weight Management Research

One project focusing on environmental approaches to weight management was conducted with the cooperation of the Dow Chemical Company, Cornell University, and National Business Group on Health ( Goetzel et al., 2010 ). Using the psychological principles of goal setting, reinforcement theory, and self-regulation, this multi-site randomized trial approached weight management by focusing on modifications to work and organizational environments rather than focusing exclusively on individual behavior change strategies. Two levels of environmental modifications were tested: straightforward environmental changes (e.g., altering onsite food and snack options, installing walking paths and/or other features supportive of physical activity, establishing an employee recognition program), and an additional set of interventions directed at building management and organizational support for healthy eating and physical activity. This was one of the first intervention studies to attempt to modify obesity in an entire work population by focusing on the work environment itself. Adding to contributions made by the PIs (similar to the example above), the fifth author provided her expertise as a registered dietitian nutritionist to include nutrition strategies to this and other intervention projects.

This project aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of implementing environmental interventions for obesity prevention in worksites and test whether environmental interventions, relative to individual interventions, reduced the prevalence of obesity, decreased healthcare utilization, and improved employee productivity. This intervention trial also featured a detailed process evaluation component to assess intervention fidelity and the development of two new assessment tools: the Environmental Assessment Tool (EAT) and the Leading by Example Questionnaire (LBE; DeJoy et al., 2012 ; DeJoy et al., 2008 ; Della, DeJoy, Goetzel, Ozminkowski, & Wilson, 2008 ). The EAT is an audit tool for assessing workplace physical and social environmental supports for weight management. The LBE is a brief scale for assessing management support for positive health behaviors. Management support is considered a crucial component of successful workplace health promotion initiatives, but prior to this project, it had seldom been objectively assessed. Intervention sites showed consistent improvements in environmental supports for weight management and positive shifts in perceived health climate. However, intervention fidelity was less robust for the intensive treatment condition, revealing some of the challenges involved in sustaining leadership engagement. Overall, the environmental interventions were effective in preventing weight gain, but did not demonstrate effects on healthcare costs and employee productivity ( Goetzel et al., 2010 ).

Translation Research

A third area of research for the WHG has involved research translation. The WHG’s translation projects primarily represent what Schulte et al. (2017) referred to as Stage 2 (Testing) among the four stages of translation, where programs shown to be effective in clinical and other non-work setting are adapted for implementation in work settings. Thus far, the WHG has conducted three translation projects. The first project began in 2007 at which time there was little guidance on the process of research translation and few translation studies in worksites to draw upon. This required the WHG to rely on the team’s experience to inform the translation process.

The WHG’s first project on translation assessed whether the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) was feasible and effective for weight loss in a worksite setting. DPP was translated into a simple, low cost intervention that could be used in a variety of work settings, including those with limited health and wellness resources. The intervention used a combination of occupational health nurses and peer health coaches to implement the translated DPP. Compared to control worksites, participants in the intervention sites maintained their weight ( Wilson, DeJoy, Vandenberg, Padilla, & Davis, 2016 ). Data from this project suggested that peer health coaches were underutilized, and employees were not comfortable talking with their peers about personal health issues.

Building on these findings, the WHG tested a second translation of DPP that included intensive health coaching facilitated by trained WHG staff. Worksites were randomized into one of three conditions: a) telephone health coaching, b) small groups facilitated by a health coach, and c) self-study (comparison condition). The phone condition lost significantly more weight than either the group condition or self-study condition ( Wilson et al., 2016 ). Translation and intervention implementation in worksites requires consideration of implementation costs, cost-effectiveness, and return-on-investment. To capture economic aspects of translation and implementation of programs in the worksite, the group recruited an SME with expertise in economic evaluation. A detailed costs analysis found that the phone condition was costlier than the group and self-study condition ( Ingels et al., 2016 ). Additionally, group coaching was not cost-effective relative to the self-study condition (Corso et al., 2018). In a more recent translation project, the WHG worked with the original developers of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) at Stanford University. The research team created a workplace version of the program “wCDSMP” and preliminary findings (project is ongoing) show positive results for a number of relevant outcomes (fatigue, physical activity, etc.) compared to the traditional CDSMP ( Smith et al., 2018 ).

As others have reported, one of the largest challenges in translating programs from clinic and community settings to worksites is balancing program fidelity and adaptation ( Backer, 2001 ). Modifications to key intervention components (i.e., local adaptations) must be possible, but not so extensive as to dilute or destroy intervention efficacy ( Wilson, Brady, & Lesesne, 2011 ). The WHG has improved in this area over time. Whereas earlier projects weighted the fidelity-adaptation balance perhaps too far toward adaptation, the more recent translation efforts have increased the fidelity of the translation process. This change has resulted in more effective interventions in terms of expected outcomes ( Blakely et al., 1987 ).

These research translation projects have relied on the intervention expertise of the fourth author, the behavior theory expertise of the third author, the methodological expertise of the second author, the experience in coordination and intervention implementation of the fifth and sixth authors, data management and analysis by the first and last authors, and the contribution of SMEs. These projects would not be possible without the unique contributions of the entire team.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Multidisciplinary Teams

A number of lessons have been learned over the last 20 years. Unlike Table 1 , what follows are general recommendations that are not necessarily specific to any stage, but provide guidance to those starting up multidisciplinary, functionally diverse labs or workgroups.

- Develop a primary vision, mission, and goal. Key to the success of any multidisciplinary team is collective identification through a shared mission, vision, and goal ( Van Der Vegt & Bunderson, 2005 ). The vision for the WHG has always been promoting better health and safety in the workplace. Practically, all decisions within the group return to asking, “how well is what we are deciding facilitating completing our vision?” For example, the WHG ignores calls for grant proposals that do not have a clear link to promoting better health, safety, and effectiveness in the workplace. Not only will a clear vision, mission, and goal provide a helpful decision-making anchor for the group, as outlined in the storming stage section, this common mission can help unite the team and buffer the negative effects of functional diversity on social integration and performance.

- Prepare for conflict via teamwork training and development. Conflict will arise on any team. However, as has been illustrated in the WHG experience and the teams research literature, multidisciplinary teams increase the probability of interpersonal conflict. A helpful way to prepare for conflict and challenges is through teamwork building and training. There are several types of effective team building and training interventions available and the choice depends on the team’s goal for the training. Two types of team building activities the authors would recommend to all new multidisciplinary teams are discipline-specific information sharing (e.g., foundational concepts, typical methodologies) and interpersonal conflict management training. The information sharing should be done on a consistent and systematic basis over time (see Slatin et al., 2004 ). Interpersonal conflict management is important in all teams, but particularly so in multidisciplinary teams (e.g., Johnson et al., 2018 ). Readers are encouraged to refer to Lacerenza, Marlow, Tannenbaum, and Salas (2018) and NRC (2015) for excellent resources on specific types of evidence-based team building and training.

- Embrace the power of multidisciplinary, functional diversity. Multidisciplinary, functionally diverse teams are essential to solve many complex, real-world problems. Supporting this statement, Uzzi, Mukherjee, Stringer, and Jones (2013) discovered that journal articles which combined the highly conventional (i.e., based on prior research) with the infusion of unusual combinations of disciplines have the highest impact. As such, the WHG recommends avoiding hiring or inviting someone to the team who duplicates the knowledge, skills, and abilities of another member—this includes staff, students, and SMEs. While some overlap is expected, the individual should bring an expertise to the team that is needed or required. As noted previously, one source of conflict for the WHG was differing views of what constituted “science” from members’ functional lenses. Part of embracing the power of multidisciplinary, functional diversity includes confronting this issue, perhaps through training mentioned in Recommendation #2. Moreover, these issues should be directly addressed with PhD students, who are in the process of being socialized to their respective fields and may come in to the multidisciplinary team with strong beliefs about “good science” that are inherited from faculty in their home departments.

- Invest in graduate students. Adding graduate students to the research team is a mutually beneficial experience for the student and the team. Graduate students—typically from I-O psychology—have always been an important part of the WHG. Graduate students provide up-to-date knowledge of their discipline’s research literature and contemporary research methods and statistical analyses, which allows the group to answer different questions in different ways than it would be able to without that perspective. From the student’s perspective, working with the WHG lets them participate first-hand in multidisciplinary research and gain competence in a number of statistical techniques and research designs—experiences that help prepare them for co-investigator roles on grant submissions. In addition to I-O psychology students, the WHG has worked with and trained students from other areas, including business management, health promotion and behavior, and epidemiology. All these students brought their own experiences and expertise and received valuable training from multiple disciplines.

- Plan for the long-term. Along with hiring “good” people (e.g., who share the team’s mission, enhance functional diversity, and are open-minded toward other perspectives), a successful multidisciplinary team should include and mentor junior faculty and research staff with a succession plan in mind. While still involved in nearly all of the projects, the third author is officially retired, and the second and fourth authors are likely within a few years of retiring. It would be disappointing to see the WHG “retire” with them. Successors should ideally join the multidisciplinary team prior to retirements, or other forms of team attrition, to form an institutional memory of the team’s history and an understanding of what it will take to adapt the team to changing circumstances and new opportunities. The WHG has incorporated a training model into its project director, research coordinator, and research director roles, where staff hired in one role were often promoted to project director or research director after gaining experience.

Conclusions

The WHG’s existence for 20 years has been due admittedly in part to good luck—meaning, the group did not form with an understanding of multidisciplinary team effectiveness or a long-term plan in mind. However, the group’s success is also largely due to addressing meaningful questions, informed by psychological principles, careful intervention designs, and rigorous quasi-experimental field methodology. The WHG’s commitment to addressing meaningful questions about health, safety, and effectiveness has guided the WHG through the inevitable conflicts and challenges over a 20-year period. While the WHG did not form with multidisciplinary team effectiveness knowledge, it did form with functional diversity as a core component. Reflecting on the group’s 20 years of existence, it is clear that the experiences and lessons learned by the WHG are consistent with the team science literature. It is the authors’ hope that this article proves to be a beneficial case study of an effective and long-lasting multidisciplinary team, providing an inside look at the triumphs, missteps, and lessons learned of the WHG, while also connecting these experiences to the scientific literature.

Contributor Information

Nicholas J. Haynes, Department of Psychology, University of Georgia.

Robert J. Vandenberg, Department of Management, University of Georgia.

David M. DeJoy, Department of Health Promotion & Behavior, University of Georgia.

Mark G. Wilson, Department of Health Promotion & Behavior, University of Georgia.

Heather M. Padilla, Department of Health Promotion & Behavior, University of Georgia.

Heather S. Zuercher, Department of Health Promotion & Behavior, University of Georgia.

Melissa M. Robertson, Owens Institute of Behavioral Research, University of Georgia.

- Backer TE (2001). Finding the balance: Program fidelity and adaptation in substance abuse prevention: A state-of-the-art review Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bell ST (2007). Deep-level composition variables as predictors of team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology , 92 ( 3 ), 595–615. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bell ST, Villado AJ, Lukasik MA, Belau L, & Briggs AL (2011). Getting specific about demographic diversity variable and team performance relationships: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management , 37 ( 3 ), 709–743. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blakely CH, Mayer JP, Gottschalk RG, Schmitt N, Davidson WS, Roitman DB, & Emshoff JG (1987). The fidelity-adaptation debate: Implications for the implementation of public sector social programs. American Journal of Community Psychology , 15 , 253–268. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bunderson JS, & Sutcliffe KM (2002). Comparing alternative conceptualizations of functional diversity in management teams: Process and performance effects. Academy of Management Journal , 45 ( 5 ), 875–893. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2017). Employer-reported workplace injuries and illnesses – 2016 Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/osh_11092017.pdf

- Carson JB, Tesluk PE, & Marrone JA (2007). Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. Academy of Management Journal , 50 ( 5 ), 1217–1234. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen G, & Kanfer R (2006). Toward a systems theory of motivated behavior in work teams. Research in Organizational Behavior , 27 , 223–267. [ Google Scholar ]

- de Wit FR, Greer LL, & Jehn KA (2012). The paradox of intragroup conflict: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology , 97 ( 2 ), 360–390. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DeChurch LA, & Mesmer-Magnus JR (2010). The cognitive underpinnings of effective teamwork: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology , 95 ( 1 ), 32–53. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DeChurch LA, Mesmer-Magnus JR, & Doty D (2013). Moving beyond relationship and task conflict: Toward a process-state perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology , 98 ( 4 ), 559–578. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Della LJ, DeJoy DM, Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ, & Wilson MG (2008). Assessing management support for worksite health promotion: Psychometric analysis of the Leading by Example instrument. American Journal of Health Promotion , 22 , 359–367. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DeJoy DM, Schaffer BS, Wilson MG, Vandenberg RJ, & Butts MM (2004). Creating safer workplaces: assessing the determinants and role of safety climate. Journal of Safety Research , 35 ( 1 ), 81–90. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DeJoy DM, & Wilson MG (2003). Organizational health promotion: Broadening the horizon of workplace health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion , 17 ( 5 ), 337–341. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DeJoy DM, Wilson MG, Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S, Baker KM, … Tully KJ (2008). Development of the environmental assessment tool (EAT) to measure organizational physical and social support for worksite obesity prevention programs. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine , 50 , 126–137. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]