- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- How to Invest

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST FICTION 2023

- NEW Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Literary Fiction

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Make Your Own List

The Best Fiction Books » Literary Figures

The best george eliot books, recommended by philip davis.

The Transferred Life of George Eliot by Philip Davis

George Eliot is all but synonymous with Victorian realism; for D H Lawrence, she was the first novelist to start ‘putting all the action inside .’ Here, Philip Davis , author of The Transferred Life of George Eliot , selects the best books by or about one of the greatest novelists of all time: ‘If you want to read literature that sets out to create a holding ground for raw human material—for human struggles, difficulties, and celebrations—read George Eliot’

Interview by David Shackleton

Scenes of Clerical Life by George Eliot

Adam Bede by George Eliot

The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot

Middlemarch by George Eliot

George Eliot's Life, as Related in Her Letters and Journals by John Walter Cross

1 Scenes of Clerical Life by George Eliot

2 adam bede by george eliot, 3 the mill on the floss by george eliot, 4 middlemarch by george eliot, 5 george eliot's life, as related in her letters and journals by john walter cross.

Y ou have written about the continuing importance of reading Victorian fiction. Why read George Eliot ?

Initially, I think it’s a mistake to think that the most relevant literature is the most recent literature. Victorian realism is extraordinarily powerful, in ways that are not fully recognised, and George Eliot is the great representative of Victorian realism in ‘all ordinary human life’.

If you want to read literature that sets out to create a holding ground for raw human material—for human struggles, difficulties, and celebrations—then you should read George Eliot. The aim of the great Victorian novel was to include as richly as possible that diverse and difficult territory.

If you were to place her in a literary context, which other realist writers would you put her alongside?

Above all, Leo Tolstoy . But if we’re talking about the English context, then I suppose Elizabeth Gaskell, Anthony Trollope and Anne Brontë. But she is in a different league to them. The only person who can touch her as a novelist, in my estimation, is Tolstoy.

If we think about later literary movements, we might think of naturalism and modernism. What are the advantages of realism over these later movements?

I tend to be wary of these titles and periods, because I think of reading as a sort of time travel. But think, for example, of D H Lawrence reading as a young man in provincial Eastwood in Nottinghamshire. He said to Jessie Chambers—the girl with whom he was reading—that it was George Eliot who ‘started putting all the action inside ’.

“Victorian realism is extraordinarily powerful, in ways that are not fully recognised, and George Eliot is the great representative of Victorian realism in ‘all ordinary human life’”

Here, we have the sense that we’re getting away from the novel merely as a story or entertainment, and towards the novel as a great inward psychological investigation. Lawrence the modernist writer follows from the tradition of the great provincial writer George Eliot. The crucial method that she develops concerns psychology. It’s as if she understands human beings better than any novelist had ever done before.

Historically, George Eliot was also writing at a time when many people lost their faith in God. If such people no longer found orthodox religion credible, they nonetheless wanted something that would replace a sense of meaning and purpose in the world.

You might ask that if you haven’t got something magical to turn to, what is the purpose of what you’re doing? What would make life worth living? These are the questions that get embedded within ordinary lives in the work of George Eliot.

That’s an interesting connection between George Eliot and D H Lawrence. Although both were from the Midlands, didn’t they come from rather different classes? Lawrence’s father was a coal miner.

George Eliot was not working class in the way that Lawrence’s father was. Though if you remember, Lawrence’s mother came from a slightly higher class, and was very keen on education, so there was a tension in their marriage.

But in George Eliot’s case—or Mary Anne Evans as she was born—her father had worked his way up from being an artisan to eventually becoming the land manager of an estate for the local aristocracy. So, he was a craftsman from the higher working classes who was beginning to establish himself within a middle-class background.

But he always thought that he was under-educated, and he wanted his daughter to be properly educated. You can see some of that story in The Mill on the Floss , which is a transmuted autobiography of Marian Evans’s early life.

Why did you chose to recommend the story ‘Janet’s Repentance’ from Scenes of Clerical Life ?

I was thinking partly about its chronology—it comes from her first published work. But also it is short, and so is a good place to start from if you’re coming to George Eliot for the first time.

Let’s remember that it’s sort of a miracle that George Eliot became George Eliot, which she did at the age of 37 or 38. She had formed an unconventional relationship with George Henry Lewes, who was already married. This gave her the security to begin a second life, and to transform from Marian Evans into the novelist George Eliot.

Before becoming a novelist, she had been a formidable self-educated intellectual who had virtually run The Westminster Review in London. But she was not content with just being an intellectual, because she needed something that is contained in the power of feeling as well as in ideas.

‘Janet’s Repentance’ is the best story in Scenes of Clerical Life , her first work of fiction. It is about a woman, Janet, who is married to Dempster. He is a local lawyer and alcoholic who, in his increasing degeneration, abuses and beats his wife.

The first move that George Eliot makes as a realist novelist is this: of course, Janet is a victim of her husband. But this is not a simple category. Where normal people will have one thought, George Eliot will have many. Janet, though the victim, begins to collude in what has happened to her and begins to drink herself. That makes her life more complicated.

She also takes her husband’s side in the local religious politics. A new man comes to their small town—a man called Mr Tryan—who is an evangelical, and therefore of a different religious party from Dempster. She joins with her husband in wishing to do this man down.

However, when going to visit a poor old woman who is dying, Janet stops at the threshold of the door into the sickroom and Tryan—her husband’s enemy—is there talking to the woman. As he talks, Janet cannot see him but she can hear him. Her normal prejudices built around seeing are held in abeyance, and she listens to the tone in which he speaks to the sick woman.

Janet no longer thinks of this man as an enemy but suddenly, to her surprise, finds that he is an equal human being. Such a second thought is simple, but it’s also powerful. It’s a moment when conventionalities fall away and something real happens.

This is why we shouldn’t dismiss Victorian realism as conventional. It isn’t just interested in the day-to-day; it’s interested in what happens within the day-to-day, and in revelation: suddenly seeing somebody’s inside manifested in the outside world.

“Victorian realism isn’t just interested in the day-to-day; it’s interested in what happens within the day-to-day, and in revelation: suddenly seeing somebody’s inside manifested in the outside world”

Eventually, Janet is thrown out by Dempster. You’d have thought that this would have been a great relief to her because she hadn’t dared to walk out herself—but actually she feels devastated.

Again, you see the complication. It’s not that leaving Dempster is a solution to all her troubles: rather, she doesn’t know what to do, and suddenly finds the big question of what her purpose is opening up before her.

‘Sympathy’ is a word that is often associated with Eliot. What role does sympathy play in this story?

When Janet hears Tryan comforting the dying woman, she hears the pure tones of human sympathy. He asks the dying woman to pray for him too, as he fears death and admits that it is one of his worst weaknesses to shrink from bodily pain. As a result, Janet begins to feel some sympathetic relation to Tryan: she thinks that he too is a human being, who has troubles like her own.

So, sympathy here is to do with the sudden forming of a relation. It may not be completely certain, it may be across great distances, but there is some emotional and imaginative connection. ‘Sympathy’ is better than the word ‘empathy’, because it conveys the fact that although you can feel for someone, you are not the same as them and you know it.

All the struggles to feel for and with people are involved in that word ‘sympathy’. In George Eliot, although it looks like a soft word, it becomes complicated and deep. Without sympathy as a small version of love, human beings have very little to call upon.

Janet and Tryan go on to develop a close relationship.

George Eliot is unafraid, even in a post-religious age, of the idea that people need to be saved. Janet is saved by Tryan in a secular way by the fact that at some level he loves her and she loves him.

Their relationship is not sexually consummated, but there is something sexual about it. They develop a relationship in which he is her supporter, her counsellor, the person who is going to help her from the despair of her alcoholism, so that, when he dies, she is his work; she is in memory of him.

Their relationship is about having someone to love and be loved by. In the teeth of modern scepticism, George Eliot retains a belief in the strong positive needs that make people feel vulnerable, and about which they’re often ashamed or in denial.

When Janet gets locked out of her home by the furious Dempster in the middle of the night, Eliot writes that ‘she seemed to be looking into her own blank future’. Could you tell us about the story’s presentation of time?

Yes. Suddenly Janet is freed from a situation in her marriage that had seemed endless. The present becomes very abrupt, and separated from the past, but it also seems to have no future. The future appears ‘blank’, as George Eliot puts it.

George Eliot is very interested in those moments of transition, although they don’t always feel like transition. Notionally, you know that there was the past and that there will be a future. Yet you don’t feel that the present moment is going to lead to anything; you don’t know that there will necessarily be a story or a narrative; you could just be stuck between things.

She is brilliant at depicting such ‘in-between’ moments that are deeply uncomfortable and disorienting in time or in space. She can detect them, whereas we might not have understood or even noticed them.

It’s similar to when Dorothea marries Casaubon in Middlemarch , and on her honeymoon finds herself again in that blankness, not knowing what is happening or what it is leading to. It’s in such moments that people struggle with all their resources to see if they can evolve, whilst not knowing whether there will be any emergence. That sense of crisis and predicament where time is almost suspended is crucial for George Eliot.

You mentioned Eliot’s transformation into a novelist. Could you tell us about her relationship to John Blackwood, and how that had an impact on her fiction?

The relationship with Blackwood was almost wholly conducted through George Henry Lewes. Marian Evans was a clever but unattractive woman. She had a series of embarrassing and humiliating liaisons with older men, and was variously rejected. Eventually, although it was by no means ideal because she couldn’t marry him, she found her partner in George Henry Lewes.

It was George Henry Lewes who took over the business end of things. He was the one who provided her with the confidence to try again to be a writer. She’d had some initial goes at fiction but not many, and he encouraged her.

It was he who, on the basis of his literary contacts, made a connection with Blackwood. Initially, he said that George Eliot was a male, and sought to protect her because Blackwood could be critical.

Blackwood was very concerned about ‘Janet’s Repentance’, with its risky subject matter of alcoholism and the abuse of wives. He was a decent man but very conservative. It was up to George Henry Lewes to say to Blackwood that he must not criticize his friend George Eliot because, being very thin-skinned, he would not write any more. Indeed, Lewes had to protect George Eliot throughout her life from reviews and criticism because she was highly insecure.

Blackwood became a very loyal supporter. However, there was a difficult moment when, encouraged by George Henry Lewes, George Eliot decided to leave him because a rival publisher was offering her an enormous amount of money for Romola . She returned to Blackwood later, contrite that she had left the old firm, and achieved great success with works such as Middlemarch .

Is it significant that Lewes claimed that George Eliot was a man in his initial correspondence with Blackwood?

Yes. Marian Evans was contemptuous of many women novelists. If she was a proto-feminist, it wasn’t because she wanted to support women writers. She felt that some women, whether through their own fault or otherwise, were letting down the seriousness of being a woman. So, it seemed to her best to dissociate herself from frivolous lady novelists, in order that the novel should be taken seriously.

“She felt that some women, whether through their own fault or otherwise, were letting down the seriousness of being a woman. So, it seemed to her best to dissociate herself…”

Am I right to think that Eliot’s first full-length novel Adam Bede started life as one of the stories in Scenes of Clerical Life ?

It was originally planned as an extension of Scenes of Clerical Life . Already in ‘Janet’s Repentance’, she was clearly moving towards needing the full canvas of the novel. She then turned from ‘Janet’s Repentance’ to write Adam Bede , which includes a transmuted version of her own father as Adam Bede.

Can you tell us about that novel?

The novel can be thought of as a triangle, with characters for its points. There’s Adam Bede: tough, morally scrupulous and self-made, but with an edge to that toughness. So, he doesn’t like his fellow workers downing their tools at six o’clock just because it’s six o’clock. He likes them to finish the job. It’s that sort of artisan strictness. He’s thoroughly straight and decent.

There is also Hetty, a beautiful young woman with whom he falls in love. Hetty hasn’t even begun to think yet, and has no need to: she’s a fantasist. Adam Bede loves her and they are engaged, but—here lies the complication—there is another man.

That other man is Arthur Donnithorne, who is a Squire and becomes Adam Bede’s employer. It is Arthur who takes Hetty away from Adam without him knowing it. He seduces her and leaves for the army, not knowing that Hetty is pregnant.

Suddenly, this provincial novel goes wild. Hetty leaves her home and embarks on a journey to try to find Arthur while heavily pregnant. Her world turns into a nightmare, and she has to bear the most terrible thoughts. It’s as if a limited human being were thrown into a limitless situation.

You might have thought that George Eliot would have been critical of her character Hetty, given that she is beautiful but not very intelligent. But such considerations suddenly drop away (just as they had dropped for Janet in relation to Tryan) when she sets Hetty in this terrible predicament: pregnant, wandering around without direction, unable to find Arthur, not knowing what to do with the baby who is about to be born, and thinking of committing suicide.

At one point, she sits by the side of a pool in which she might drown herself. She had been a vain creature, but here her vanity is transformed. She begins to feel her own arms, and the pleasure of that feeling, the warmth and the roundness of the flesh, makes her think that she should live—that she shouldn’t commit suicide. What had been before silly and weak, is now something on the side of life. George Eliot loves those transitions.

Thinking back to the love-triangle, the relationship between Adam and Arthur comes to a head in the chapter called ‘Crisis’.

It was a chapter that George Henry Lewes had partly suggested: to bring the two men together to create a sort of implosion. But what is remarkable about it is not the anger and violence on Adam’s part, although that is there. Rather, what is interesting, in one of those switches of perspective that are so powerful in George Eliot, is the effect on Arthur.

When Arthur realises how damaged and hurt Adam is by his actions, he experiences something irrevocable. At that moment the feckless Arthur—who is not a bad man but is sexually besotted with Hetty—suddenly sees for the first time, looking at Adam’s face, that there are things that you cannot get away with.

“Suddenly, this provincial novel goes wild”

That reality principle—that there will be consequences—is the astounding depth of the ‘Crisis’ chapter. It’s not about the sensationalism of bringing the two men together in a potential fight. Instead, it explores ‘morality’ (which might otherwise seem a very dull Victorian concept) as an inner psychological process, in which Arthur realises the indelible consequences of his actions.

In those moments when Arthur realises the terrible damage that he’s done, you get an interior language—what Lawrence called ‘action’ on the ‘inside’—which is not spoken out loud. It is what we all silently say in our hearts or minds or brains, and sometimes don’t even want to know that we’re saying it.

Technically, this is called free indirect discourse. It’s not direct discourse in which a character says something out loud, or ‘thinks that…’. Rather, it’s an ambiguous discourse that follows Arthur’s train of thought, even though he himself may not know or want to know what he is thinking. That’s one of the important technical moves that George Eliot makes.

Thinking more about this psychological understanding, you have elsewhere drawn a parallel between Eliot as a realist novelist and psychological field theory. Could you explain that parallel?

Basically, it’s about getting into areas—often of secrecy—where suddenly that which will not be spoken out loud in society, nonetheless begins to find expression in a secret language of unconsummated confession.

These areas can be geographical or prompted by geography. For example, when Hetty leaves her home and goes into the country in search of Arthur, it’s not just that she’s in the wilderness but that she’s in a different psychological place prompted by that wilderness. Her thoughts almost seem outside her, as she looks at the pool as the place of suicide.

For other people, these fields go on inside . For example, there’s the dishonest banker Mr Bulstrode in Middlemarch who wants to forget his past, but eventually that past begins to be uncovered and he begins to feel terrible fear.

George Eliot said that it’s like trying to look out of the window during a dark night. When the lights are illuminated behind you in the room, you can’t see out of the window: what you see are reflections of yourself and the room behind you.

That is a wonderful image of creating a psychological field: you want to look out but suddenly with the reflection, you’re being turned back in, back to the past. You cannot get away from the zone—in this case, of guilt—that has been created around you. It’s a place that you now have to inhabit psychologically.

You mentioned that Eliot achieves psychological interiority through free indirect discourse. Jane Austen is also known for her adept use of free indirect discourse. What’s the relation between the two? Was Eliot inspired by Austen? Did she learn from her?

I think she did learn from her, though there’s no explicit record of this. It’s a deep and complicated question that you’re asking here, but I suppose that it’s different in George Eliot for this reason: she is utterly obsessed with secrets.

It’s true that Jane Austen is very committed to privacy within the public, and in that sense there’s a likeness in terms of hidden psychology and hidden forms of being. But it’s a lot more fraught in George Eliot than it is in Jane Austen, because often her characters either want those things to come out, or they are fearful that they will come out.

For George Eliot, psychology is doubly important because there isn’t anything else. That is to say, if you want to find purpose or meaning in life, you’re going to have to find it in this psychological holding ground. She does not subscribe to a firm theology; she is a big reader of philosophy but does not believe in a single philosophical system. In a world without answers, the great holding ground is within the human psyche, with all of its messiness.

You described The Mill on the Floss as a transmuted autobiography . How is that so?

In one sense, it’s simple. Maggie Tulliver is a portrait of Marian Evans as a young woman: she has powerful emotions and a strong desire to be educated, and wants a life that is not merely dull and normal.

She will look around a room and see a mother, a father, a brother, articles of furniture, and she thinks: what links them all together? What makes them more than bits and pieces? What’s the meaning of these things?

This is why in my book The Transferred Life of George Eliot I talk about George Eliot’s syntax, not simply in terms of the structure of her sentences, but in some deeper sense as a way of putting things together in your mind. And that’s what Maggie Tulliver is after: links to make some sort of meaning.

But, as Maggie moves from her romantic childhood to the dawn of sexuality, she encounters the difficulty of sexual relationships. This is what Marian Evans had herself struggled with the most.

Maggie meets an attractive man, Stephen Guest, who is already engaged to her cousin. Maggie is a decent person, and she doesn’t want to betray her cousin, but the power of Eros and her own emotional needs are very strong.

What does George Eliot do in The Mill on the Floss ? She creates a situation that’s not autobiographical in the sense that it actually happened, but it’s autobiographical in the sense that it’s the sort of thing that George Eliot and Marian Evans are most interested in. It’s a humiliating middle-ground. That’s to say, Maggie begins to elope with Stephen, but half-way through on board ship, she decides that she can’t go through with it. It is the worst of both worlds: she has lost her reputation but also given up her man.

Almost everyone scorns Maggie when she comes back, other than her mother. This is surprising, because her mother had been completely unimportant in her life, compared to the father whom she adored, just as Marian Evans adored her own father.

But in her great crisis, in her great humiliation, Maggie hears from her mother four words that Marian Evans never heard from her mother: ‘You’ve got a mother’. That’s the link, the love, that Marian Evans herself had never had.

A major focus of The Mill on the Floss is the relationship between Maggie and her brother Tom Tulliver, who is a version of Isaac, George Eliot’s brother in real life. But here for once, it is not the father or the brother who offers the love, but the mother—and Marian Evan’s mother is never really there for her, as we now say.

Can you tell us more about Tom Tulliver?

Tom Tulliver is a hard man. He’s harder than Adam Bede, who was softened by what happened to Hetty and her suffering. Tom is much more rigid. He is practical and Maggie admires him, yet she knows that she is different from him, and in some sense deeper.

Isaac Evans, the brother whom Marian Evans adored, was like this. When Marian Evans formed a relationship with George Henry Lewes, Isaac wouldn’t speak to her. He wouldn’t speak to her until very near the year of her death when, after Lewes died, she married officially for the first time. Then and only then would he make communication.

The hurt of losing the love of Isaac goes very powerfully into The Mill on the Floss . It’s a mixture of admiration for Tom, combined with the counter-judgement that he, in judging her, is wrong.

“For George Eliot, psychology is doubly important because there isn’t anything else – in a world without answers, the great holding ground is within the human psyche, with all of its messiness”

It’s a wonderful conflict between loving someone and having critical thoughts about them that you can’t say out loud, or if you do say them then you’ve forfeited the right for them, simply to be accepted because you’ve done something wrong as well. This is just the sort of messy relationship in which George Eliot was so interested.

In the novel, Maggie and Tom both drown in the great flood.

This is the culmination of the novel. They are in a sort of emotional climax. Maggie begins to voyage in the midst of the flood towards her brother Tom in order to rescue him from drowning. She doesn’t, and they both drown together.

Middlemarch is longer and more narratively complex than Adam Bede .

It’s like several novels in one. It began as two separate novels, one about the town of Middlemarch and its new doctor Lydgate, and another about Dorothea, a young woman who has great intelligence and even greater emotional needs and aspirations.

George Eliot started to join these separate novels together, and to bring in new elements, so that there are four or five things going on at the same time. The wonderful thing about that is the novel stops being linear. Suddenly you move from one character or partnership to another, across the novel rather than along. It is a web shape.

While you’re thinking about the relationship of Dorothea and her scholar husband Casaubon, you are suddenly taken back to the relationship between Lydgate and Rosamond, who (like Hetty in Adam Bede ) is a beautiful but selfish young woman.

It’s as if you are being taught to move from one life to another and you become, as a reader, a sort of novelist: somebody who can understand different people across different classes, ages and genders.

The idea is that, while you read successively, the events being narrated happen simultaneously. It makes you appreciate that there are so many lives interconnected and separated going on at the same time in this little world. It’s only a provincial town, but it’s an image of the whole world.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

That’s why George Eliot has the metaphor of the web—of things interconnecting across different stories. That is the complicated form of Middlemarch which, I would say, must be the greatest novel in the language.

That’s extremely high praise. Why is it the greatest novel in the language?

Because it’s a novel that you would go to in terms of ordinary troubles, troubles of vocation, or marriage, all sorts of purpose and loss and frustration. Here is Dorothea who, in an earlier age, might have been a great religious figure, but there’s no religion and there’s no role for women. So, what happens to that content in a person when they haven’t got form? Here’s Lydgate, a doctor with a strong sense of vocation but with certain weaknesses, particularly sexual weaknesses. Will he manage to do the great thing that he wants to do?

It’s not as if ordinary people simply begin ordinary and remain ordinary. There are extraordinary things that happen, and there are also great disappointments. It’s the hidden story of what doesn’t happen that constantly runs throughout the novel.

In terms of the relationship between Dorothea and Casaubon, Dorothea makes a bad choice in marrying him. She stupidly choses to marry an aged scholar who isn’t anything like the idol she had been looking for. And clearly, sexually, he’s as impotent as he is in his work which he never finally produces.

You feel for Dorothea because Casaubon is unattractive and he’s horrible to her. Yet, George Eliot also manages to make you feel for Casaubon. It’s an almost impossible feat.

This is how your mind is going to be expanded by reading the novel: you feel for Dorothea, you feel for Casaubon, and you feel for both of them almost simultaneously, in the space between them all at the same time.

You’ve talked about George Eliot’s ability to create remarkable switches of perspective. Can you explain how she does that with Casaubon in this novel?

She begins a chapter by simply asking: ‘but why always Dorothea?’ All the neighbours think that Casaubon is dull and unattractive: Dorothea’s sister objects to his blinking eyes and white moles.

But then George Eliot intervenes, and says suppose we turn from outside estimates to wonder what is actually going on within Casaubon. Suddenly you see, for example, that his unkindness to Dorothea when she offers to help him with his work does not constitute a simple rejection. It comes out of his fear that she knows that he’s never going to be able to finish this work. She doesn’t think that—it is his own fear, projected.

So, they are people who should be within inches of each other within their marriage, but are separated across a vast gulf of misunderstanding because her love seems to him like criticism, and his criticism of her seems to be hatred rather than something pitiful.

Dorothea, in the midst of her victimisation, chooses to help him. This is not female submissiveness. She doesn’t love him, she only pities him, but she realises that she is the greater body.

“It’s as if you are being taught to move from one life to another and you become, as a reader, a sort of novelist: somebody who can understand different people across different classes, ages and genders”

Casaubon is going to die, and Dorothea wishes to be ‘the mercy’ for his sorrows. She doesn’t say ‘merciful towards’. She thinks she should be ‘the mercy’, as if there were a thing called mercy that can exist in the world, and should be embodied. So, she thinks that whatever has happened to her, she will be the mercy for Casaubon, as George Eliot often is for her characters.

I like your idea of the reader of Middlemarch learning to appreciate life as a sort of interconnected web. Thinking back to Adam Bede , is that exactly the sort of ability that Hetty lacks?

Yes. Hetty would read novels, if she read at all, to have the fantasy of running off with Arthur. When you read Middlemarch —this novel for grown-ups, as Virginia Woolf says—you get the sense of a complicated human geometry: you move around different angles, perspectives and dimensions.

Beneath the conscious behaviour, or the words that are spoken, lies the depth of the unconscious, the small things that happen in transition. So, suddenly, you’ve got the most powerful working model in fiction of what human life is like. It’s as if somehow George Eliot has found the building blocks—the DNA—of existence. She can see all of that framework, all the underlying stuff, all the different connections, as well as producing the individuality of feeling within each separate person.

This amounts to an almost superhuman activity: to be able to feel with people, but to criticise them; to be able to imagine radically different people, while seeing how radically different they are; to be able to put them together in a marriage and feel for them both at the same time. It’s constantly creating a content that bursts through simple containers and makes you have to think more difficult things than are quite comfortable.

To give just one example, in the marriage between Lydgate and Rosamond, the doctor knows they’re in financial difficulties and asks his wife to economise. Rosamond doesn’t want to do that and she takes no notice. Lydgate desperately wants to keep their marriage together although he knows that it is falling apart.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount .

We read that ‘his marriage would be a mere piece of bitter irony if they could not go on loving each other’. And then comes this devastating sentence: ‘In marriage, the certainty, “She will never love me much”, is easier to bear than the fear, “I shall love her no more”’.

He daren’t think to himself that he will love her no more. He daren’t even think the sentences that George Eliot’s syntax is producing, though they are there in his own consciousness.

Your last recommendation is J W Cross’s George Eliot’s Life . Who was Johnny Cross and what was his relationship to George Eliot?

Johnny Cross was a young friend to George Henry Lewes and George Eliot—or Marian Lewes, as she was known then—and almost had the status of a nephew. When Lewes died, she spent more time with Johnny Cross who comforted her. They read Dante together and Tennyson’s ‘In Memoriam’, as part of a process of mourning and seclusion.

She had waited so long to find someone and then she lost Lewes. She always needed someone to lean on. Although Johnny Cross was decades younger than her, she turned to him and married him.

It was the first formal legal marriage she had. That’s when Isaac Evans wrote to congratulate her, twenty years too late.

There was a terrible incident in Venice on their honeymoon when Cross, who was a depressive, threw himself out of the window. Some people think—we can never know for sure—that he didn’t want to sexually consummate the marriage. If that were true—and I hope it isn’t—then that must have been a terrible experience for George Eliot. She had gone full circle—still ugly, as she had always feared she was.

Whatever the truth of that particularly story, Johnny Cross later wrote the life of George Eliot. The great achievement of this work is that there is very little written by Cross himself. He tried to create a surrogate autobiography, by compiling three volumes of letters and diary entries in chronological order, from Marian Evans through to George Eliot.

“We write biographies as if they could take the place of novels, yet they can’t: novels offer more truths than biographies ever can”

In George Eliot’s Life , you begin to read between the lines. It’s as if you’ve got the original text, and you have to guess; he doesn’t fill in the gaps. You begin to see the suffering of Marian Evans. There are some details, such as sexual details, that he omits, but nonetheless you get the general feel of the struggle that she had in those first 37 or 38 years to grow up, to find a life, and to be somebody.

George Eliot always said she didn’t want a biography, and that she wouldn’t write an autobiography. The only reason for ever having either, she said, would be if it showed an equivalent person that despite and because of all of their struggles, they could make something of themselves. Well, that’s what you can feel, particularly in the first of the three volumes.

Cross’s approach has served as a model for me, as a biographer. I think biographies are often bad fiction. We fill in the gaps and offer explanations and get all chummy. We write biographies as if they could take the place of novels , yet they can’t: novels offer more truths than biographies ever can.

Like Cross, I try in my own book to use as many of George Eliot’s words as possible. But I reuse the words not only from her diaries and letters, but also from the literature itself, because the deepest biography is always going to be that which gets into the heartfelt mentality of the author.

I like to think that there could be a George Eliot part of us that looks out from within our lives, in lieu of God, trying to do passionately informed thinking in relation to oneself and others. That’s what the novelist does, and I would like the novelist to be taken seriously as a producer of the deepest form of human thinking that there is.

November 6, 2017

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Philip Davis

Philip Davis is the author of The Transferred Life of George Eliot , The Victorians 1830-1880 , and a companion volume on Why Victorian Literature Still Matters . He has written on Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson, the literary uses of memory from Wordsworth to Lawrence, and various books on reading. His previous literary biography was a life of Bernard Malamud. He is general editor of the Literary Agenda paperback series from OUP, on the future of literary studies, for which he wrote R eading and the Reader. He is also editor of The Reader magazine, the written voice of the outreach organisation The Reader .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

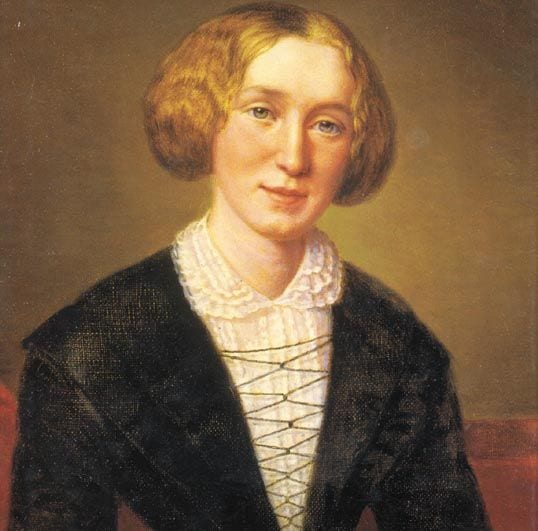

Biography of George Eliot, English Novelist

The pen name of Mary Ann Evans, author of Middlemarch

Library of Congress / public domain

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ThoughtCo_Amanda_Prahl_webOG-48e27b9254914b25a6c16c65da71a460.jpg)

- M.F.A, Dramatic Writing, Arizona State University

- B.A., English Literature, Arizona State University

- B.A., Political Science, Arizona State University

Born Mary Ann Evans, George Eliot (November 22, 1819 – December 22, 1880) was an English novelist during the Victorian era . Although female authors did not always use pen names in her era, she chose to do so for reasons both personal and professional. Her novels were her best-known works, including Middlemarch , which is often considered among the greatest novels in the English language.

Fast Facts: George Eliot

- Full Name: Mary Ann Evans

- Also Known As: George Eliot, Marian Evans, Mary Ann Evans Lewes

- Known For: English writer

- Born: November 22, 1819 in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England

- Died: December 22, 1880 in London, England

- Parents: Robert Evans and Christiana Evans ( née Pearson)

- Partners: George Henry Lewes (1854-1878), John Cross (m. 1880)

- Education: Mrs. Wallington's, Misses Franklin's, Bedford College

- Published Works: The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), Romola (1862–1863), Middlemarch (1871–72), Daniel Deronda (1876)

- Notable Quote: “It is never too late to be what you might have been.”

Eliot was born Mary Ann Evans (sometimes written as Marian) in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England, in 1819. Her father, Robert Evans, was an estate manager for a nearby baronet, and her mother, Christiana, was the daughter of the local mill owner. Robert had been married previously, with two children (a son, also named Robert, and a daughter, Fanny), and Eliot had four full-blooded siblings as well: an older sister, Christiana (known as Chrissey), an older brother, Isaac, and twin younger brothers who died in infancy.

Unusually for a girl of her era and social station, Eliot received a relatively robust education in her early life. She wasn’t considered beautiful, but she did have a strong appetite for learning, and those two things combined led her father to believe that her best chances in life would lie in education, not marriage. From ages five to sixteen, Eliot attended a series of boarding schools for girls, predominantly schools with strong religious overtones (although the specifics of those religious teachings varied). Despite this schooling, her learning was largely self-taught, in great part thanks to her father’s estate management role allowing her access to the estate’s great library. As a result, her writing developed heavy influences from classical literature, as well as from her own observations of socioeconomic stratification .

When Eliot was sixteen, her mother Christiana died, so Eliot returned home to take over the housekeeping role in her family, leaving her education behind except for continued correspondence with one of her teachers, Maria Lewis. For the next five years, she remained largely at home caring for her family, until 1841, when her brother Isaac married, and he and his wife took over the family home. At that point, she and her father moved Foleshill, a town near the city of Coventry.

Joining New Society

The move to Coventry opened new doors for Eliot, both socially and academically. She came into contact with a much more liberal, less religious social circle, including such luminaries as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Harriet Martineau , thanks to her friends, Charles and Cara Bray. Known as the “Rosehill Circle,” named after the Brays’ home, this group of creatives and thinkers espoused rather radical, often agnostic ideas, which opened Eliot’s eyes to new ways of thinking that her highly religious education had not touched on. Her questioning of her faith led to a minor rift between her and her father, who threatened to throw her out of the house, but she quietly carried out superficial religious duties while continuing her new education.

Eliot did return once more to formal education, becoming one of the first graduates of Bedford College, but otherwise largely stuck to keeping house for her father. He died in 1849, when Eliot was thirty. She traveled to Switzerland with the Brays, then stayed there alone for a time, reading and spending time in the countryside. Eventually, she returned to London in 1850, where she was determined to make a career as a writer.

This period in Eliot’s life was also marked by some turmoil in her personal life. She dealt with unrequited feelings for some of her male colleagues, including publisher John Chapman (who was married, in an open relationship, and lived with both his wife and his mistress) and philosopher Herbert Spencer. In 1851, Eliot met George Henry Lewes, a philosopher and literary critic, who became the love of her life. Although he was married, his marriage was an open one (his wife, Agnes Jervis, had an open affair and four children with newspaper editor Thomas Leigh Hunt), and by 1854, he and Eliot had decided to live together. They traveled together to Germany, and, upon their return, considered themselves married in spirit, if not in law; Eliot even began to refer to Lewes as her husband and even legally changed her name to Mary Ann Eliot Lewes after his death. Although affairs were commonplace, the openness of Eliot and Lewes’s relationship caused much moral criticism.

Editorial Work (1850-1856)

- The Westminster Review (1850-1856)

- The Essence of Christianity (1854, translation)

- Ethics (translation completed 1856; published posthumously)

After returning to England from Switzerland in 1850, Eliot began pursuing a writing career in earnest. During her time with the Rosehill Circle, she had met Chapman, and by 1850, he had purchased The Westminster Review . He had published Eliot’s first formal work – a translation of German thinker David Strauss's The Life of Jesus – and he hired her onto the journal’s staff almost immediately after she returned to England.

At first, Eliot was just a writer at the journal, penning articles that were critical of Victorian society and thought. In many of her articles, she advocated for the lower classes and criticized organized religion (in a bit of a turnabout from her early religious education). In 1851, after being at the publication for just one year, she was promoted to assistant editor, but continued writing as well. Although she had plenty of company with female writers, she was an anomaly as a female editor.

Between January 1852 and mid-1854, Eliot essentially served as the de facto editor of the journal. She wrote articles in support of the wave of revolutions that swept Europe in 1848 and advocating for similar but more gradual reforms in England. For the most part, she did the majority of the work of running the publication, from its physical appearance to its content to its business dealings. During this time, she also continued pursuing her interest in theological texts, working on translations of Ludwig Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity and of Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics ; the latter was not published until after her death.

Early Forays into Fiction (1856-1859)

- Scenes of Clerical Life (1857-1858)

- The Lifted Veil (1859)

- Adam Bede (1859)

During her time editing the Westminster Review , Eliot developed a desire to move into writing novels . One of her last essays for the journal, titled “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” laid out her perspective on novels of the time. She criticized the banality of contemporary novels written by women, comparing them unfavorably to the wave of realism sweeping through the continental literary community, which would eventually inspire her own novels.

As she prepared to take the plunge into writing fiction, she chose a masculine pen name : George Eliot, taking Lewes’s first name along with a surname she chose based on its simplicity and appeal to her. She published her first story, “The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton," in 1857 in Blackwood’s Magazine . It would be the first of a trio of stories that eventually were published in 1858 as the two-volume book Scenes of Clerical Life .

Eliot’s identity remained a mystery for the first few years of her career. Scenes of Clerical Life was believed to have been written by a country parson or a wife of a parson. In 1859, she published her first complete novel, Adam Bede . The novel became so popular that even Queen Victoria was a fan, commissioning an artist, Edward Henry Corbould, to paint scenes from the book for her.

Because of the novel’s success, public interest in Eliot’s identity spiked. At one point, a man named Joseph Liggins claimed that he was the real George Eliot. In order to head off more of these imposters and satisfy public curiosity, Eliot revealed herself soon after. Her slightly scandalous private life surprised many, but fortunately, it did not affect the popularity of her work. Lewes supported her financially as well as emotionally, but it would be nearly 20 years before they would be accepted into formal society as a couple.

Popular Novelist and Political Ideas (1860-1876)

- The Mill on the Floss (1860)

- Silas Marner (1861)

- Romola (1863)

- Brother Jacob (1864)

- "The Influence of Rationalism" (1865)

- In a London Drawingroom (1865)

- Two Lovers (1866)

- Felix Holt, the Radical (1866)

- The Choir Invisible (1867)

- The Spanish Gypsy (1868)

- Agatha (1869)

- Brother and Sister (1869)

- Armgart (1871)

- Middlemarch (1871–1872)

- The Legend of Jubal (1874)

- I Grant You Ample Leave (1874)

- Arion (1874)

- A Minor Prophet (1874)

- Daniel Deronda (1876)

- Impressions of Theophrastus Such (1879)

As Eliot’s popularity grew, she continued working on novels, eventually writing a total of seven. The Mill on the Floss was her next work, published in 1860 and dedicated to Lewes. Over the next few years, she produced more novels: Silas Marner (1861), Romola (1863), and Felix Holt, the Radical (1866). In general, her novels were consistently popular and sold well. She made several attempts at poetry, which were less popular.

Eliot also wrote and spoke openly about political and social issues. Unlike many of her compatriots, she vocally supported the Union cause in the American Civil War , as well as the growing movement for Irish home rule . She was also heavily influenced by the writings of John Stuart Mill , particularly with regards to his support of women’s suffrage and rights. In several letters and other writings, she advocated for equal education and professional opportunities and argued against the idea that women were somehow naturally inferior.

Eliot’s most famous and acclaimed book was written towards the later part of her career. Middlemarch was published in 1871. Covering a wide range of issues, including British electoral reform, the role of women in society, and the class system, it was received with middling reviews in Eliot’s day but today is considered one of the greatest novels in the English language. In 1876, she published her final novel, Daniel Deronda . After that, she retired to Surrey with Lewes. He died two years later, in 1878, and she spent two years editing his final work, Life and Mind . Eliot’s last published work was the semi-fictionalized essay collection Impressions of Theophrastus Such , published in 1879.

Literary Style and Themes

Like many authors, Eliot drew from her own life and observations in her writing. Many of her works depicted rural society, both the positives and the negatives. On the one hand, she believed in the literary worth of even the smallest, most mundane details of ordinary country life, which shows up in the settings of many of her novels, including Middlemarch . She wrote in the realist school of fiction, attempting to depict her subjects as naturally as possible and avoid flowery artifice; she specifically reacted against the feather-light, ornamental, and trite writing style preferred by some of her contemporaries , especially by fellow female authors.

Eliot’s depictions of country life were not all positive, though. Several of her novels, such as Adam Bede and The Mill on the Floss , examine what happens to outsiders in the close-knit rural communities that were so easily admired or even idealized. Her sympathy for the persecuted and marginalized bled into her more overtly political prose, such as Felix Holt, the Radical and Middlemarch , which dealt with the influence of politics on “normal” life and characters.

Because of her Rosehill-era interest in translation, Eliot was gradually influenced by German philosophers. This manifested itself in her novels in a largely humanistic approach to social and religious topics. Her own sense of social alienation due to religious reasons (her dislike of organized religion and her affair with Lewes scandalized the devout in her communities) made its way into her novels as well. Although she retained some of her religiously based ideas (such as the concept of atoning for sin through penance and suffering), her novels reflected her own worldview that was more spiritual or agnostic than traditionally religious.

Lewes’s death devastated Eliot, but she found companionship with John Walter Cross, a Scottish commission agent. He was 20 years younger than her, which led to some scandal when they married in May 1880. Cross was not mentally well, however, and jumped from their hotel balcony into the Grand Canal while they were on their honeymoon in Venice . He survived and returned with Eliot to England.

She had been suffering from kidney disease for several years, and that, combined with a throat infection she contracted in late 1880, proved too much for her health. George Eliot died on December 21, 1880; she was 61 years old. Despite her status, she was not buried alongside other literary luminaries at Westminster Abbey because of her vocal opinions against organized religion and her long-term, adulterous affair with Lewes. Instead, she was buried in an area of Highgate Cemetery reserved for the more controversial members of society, next to Lewes. On the 100 th anniversary of her death, a stone was placed in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey in her honor.

In the years immediately following her death, Eliot’s legacy was more complicated. The scandal of her long-term relationship with Lewes had not entirely faded (as demonstrated by her exclusion from the Abbey), and yet on the other hand, critics including Nietzsche , criticized her remaining religious beliefs and how they impacted her moral stances in her writing. Soon after her death, Cross wrote a poorly received biography of Eliot that portrayed her as nearly saintly. This obviously fawning (and false) portrayal contributed to a decline in sales and interest in Eliot’s books and life.

In later years, however, Eliot returned to prominence thanks to the interest of a number of scholars and writers, including Virginia Woolf . Middlemarch , in particular, regained prominence and eventually became widely acknowledged as one of the greatest works of English literature. Eliot’s work is widely read and studied, and her works have been adapted for film, television, and theater on numerous occasions.

- Ashton, Rosemary. George Eliot: A Life . London: Penguin, 1997.

- Haight, Gordon S. George Eliot: A Biography. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Henry, Nancy, The Life of George Eliot: A Critical Biography , Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- 42 Must-Read Feminist Female Authors

- Biography of Anne Brontë, English Novelist

- Biography of Emily Brontë, English Novelist

- "A Simple Heart" by Gustave Flaubert Study Guide

- Virginia Woolf Biography

- Biography of Mary Somerville, Mathematician, Scientist, and Writer

- Biography of Frances Willard, Temperance Leader and Educator

- Biography of Charlotte Brontë

- Biography of Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Ednah Dow Cheney

- Top 100 Women of History

- Biography of Lydia Maria Child, Activist and Author

- Mary Wollstonecraft: A Life

- Selma Lagerlöf (1858 - 1940)

- Women of the Harlem Renaissance

- Biography of Mary Todd Lincoln, Troubled First Lady

Quick Facts

George Eliot Best Books 📚

Mary Ann Evans who writes with the pen name George Eliot is a famous English novelist who wrote many novels that make up part of Victorian literature and influence British culture. In pop culture, she is a stellar example of a female writer that used a masculine pseudonym to have an objective appreciation of her novels.

Written by Onyekachi Osuji

B.A. in Public Administration and certified in Creative Writing (Fiction and Non-Fiction)

George Eliot is a nom de plume that is well known for realistic novels in the Victorian era. The name is inscribed as the author on the cover of seven novels and a collection of short stories. Mary Ann Evans, the woman behind the pen name George Eliot, has gifted the world poems, reviews, and novels so rich in themes that they remain relevant even after tens of decades. Let’s take a look at some of the most famous novels by George Eliot.

Eliot’s very first novel gave her an encouraging debut. Adam Bede is about a twenty-six-year-old carpenter, loved and admired by many. Adam begins to court a beautiful but shallow girl called Hetty but Hetty secretly has an affair with a dashing soldier from the gentry named Arthur Donnithorne. The love triangle results in complications that would lead to a crime, exile, death, and heartbreak.

Mill on the Floss

Mill on the Floss is George Eliot’s second novel published in 1860. It was preceded by Adam Bede the first of the George Eliot novels. Mill on the Floss narrates the story of Maggie Tulliver and the challenges of balancing her familial ties with her romantic relationships. The heart of the story lies in her love-hate relationship with her brother Tom Tulliver whose composition of character is entirely different from Maggie’s.

The story is set in the fictional village of St Ogg’s as nine-year-old Maggie relishes her childhood in her family mill Dolcote Mill which is located at a junction between the River Floss and River Ripple. The dynamics of their relationship get complicated as they face several family crises such as bankruptcy, the loss of the Dolcote Mill, and the death of their father.

Some of the complications arise as Maggie comes of age and begins to form romantic relationships. First, Maggie forms a friendship with Philip Wakem and this bond gives her an avenue to escape the austerity of her own life, but eventually, Tom who despises Philip finds out about the friendship and forces Maggie to renounce Philip. Tom and Maggie’s relationship takes a turn for the worse when Maggie elopes with her cousin’s suitor Steven Guest, although Maggie refuses to marry Steven after the elopement, Tom refuses to forgive her upon her return and harshly sends her away.

In the end, Maggie and Tom reconcile as they both drown to their death in a flood.

The novel has themes of gender discrimination and family relationships. Critics suggest the author, Mary Ann Evans might have been projecting her relationship with her brother Isaac Evans in The Mill on the Floss.

Silas Marner

Silas Marner is a melancholic story but with a happy ending. It is George Eliot’s third novel published in 1861. The novel is centered on the protagonist Silas Marner, who losses faith in humanity and in God due to a betrayal and an unjust treatment that leaves him heartbroken and in despair, and how fate smiles on him with time and restores his lost faith.

Silas Marner is a linen weaver and a member of a Calvinist congregation in a fictional town called Lantern Yard. He is accused of stealing the church money while watching over their ill deacon. Silas pleads his innocence but is implicated in the case by his pocket knife which was found at the scene of the theft and the discovery of the empty bags that once contained the money in Silas Marner’s house.

Silas maintains his innocent plea and suspects his best friend, William Dane has framed him up because William had borrowed Silas’ pocket knife shortly before the discovery of the theft. The congregation agree to cast a lot to determine whether Silas would be proven innocent and Silas agrees to this, hoping that God would vindicate him and direct the lot to result in his favor. But the lot turns out against Silas’ innocence. Silas Marner’s fiancee breaks off their engagement and marries William Dane instead.

Betrayed and shattered, Silas Marner moves to the Midland village of Raveloe where he begins a new life, continuing in his craft as a linen weaver but isolating himself from the villagers. The villagers of Raveloe see Silas as a miserly recluse while Silas finds comfort in the gold coins he accumulates.

On a foggy night, Dunstan Cass, the son of a wealthy landowner in Raveloe, steals all of Silas’ gold coins but falls into a stone quarry as he makes away with the money. Silas is heartbroken again when he discovers that his gold coins have been stolen. The villagers help him search for it but it yields no success. Duncan Cass disappears around the same time but no one makes a connection between the two incidents because Dunstan is a prodigal son that is known to disappear on occasion.

Meanwhile, Godfrey Cass, the older brother to Dunstan hides a big secret. He is married to Molly, an opium addict from another town. Godfrey hopes no one discovers this secret as he intends to marry Nancy Lammeter a respectable girl from a middle-class family. Molly comes to Raveloe with her little daughter, intent on revealing Godfrey’s secret to his family but falls unconscious in the snow while her toddler daughter strays off to Silas’ hut.

Silas finds the little girl in his hut and at first mistakes her gold curls for his lost gold. When he realizes she is a little girl, he follows her trail and it takes him to where Molly is lying dead. He reports the incident and Godfrey on recognizing Molly thinks it is convenient for his secret and does not identify her. In the absence of any claim on the little girl, Silas adopts her and names her Eppie.

Silas begins to care for Eppie and grows to love her. Dolly Winthrop, Silas’ neighbor helps him in taking care of Eppie while Godfrey Cass occasionally supports him with money.

Sixteen years go by and Eppie blossoms into the belle of Raveloe while Godfrey Cass, who had succeeded in marrying Nancy Lammeter, remains childless in the marriage. Construction commences at the stone quarry and Dunstan Cass’ skeleton along with Silas bags of Gold coins are found in the stone quarry. The bags of gold are returned to Silas but shortly after, Godfrey Cass confesses to being Eppie’s biological father and begs Eppie to return to him. This makes Silas Marner’s gold lose value to him because he cannot imagine a happy life without Eppie as his daughter. Eppie refuses to leave Silas and it makes him overjoyed.

Silas revisits Lantern Yard but finds none of the milestones or people he once knew. The town has been taken over by a factory. Therefore, he never gets to know the fate of all those that had treated him unjustly.

Eppie marries Aaron Winthrop and they all live together happily in Raveloe.

The most important theme in this novel is the value of love among humans over material wealth and it is one of the most enjoyable reads from George Eliot.

Middlemarch , A Study of Provincial Life

Middlemarch, A Study of Provincial Life is one of the most acclaimed novels by George Eliot. It was published between 1871 and 1872 in eight volumes. The story is set in a fictional English village called Middlemarch between 1829-1832.

The plot centers around Dorothea Brooke, an idealistic, intelligent nineteen-year-old who marries a much older man with hopes of joining in his research and getting intellectual mentorship from him; Tertius Lydgate, a medical doctor whose career is threatened by his idealism and progressive ideas; Fred Vincy and his sister Rosamund, children of the mayor who languish in the hope of finding fortune in inheritance or marriage; Mary Garth a plain but kind young lady whom Fred Vincy is in love with; and Nicholas Bulstrode, a wealthy banker who is hypocritic in his religiosity and hides an unsavory past.

The novel follows their lives as it explores the themes of idealism, religion, and social stratification among others.

Daniel Deronda

Published in 1876, it is the last of George Eliot’s novels. The plot of Daniel Deronda intertwines the stories of two characters–the eponymous character Daniel Deronda and Gwendolyn Harleth. The story is set across various countries in Europe including Germany, England, and Italy in the years 1865 and 1866.

The novel begins in 1866 with Daniel observing Gwendolyn as she loses all her money in a game. The next day, Daniel redeems Gwendolyn’s necklace which she pawned for money and sends someone to return the necklace to her. Gwendolyn is grateful to Daniel as she needs the money to return home to her family.

From there, the story splits into flashbacks to 1865 detailing Gwendolyn’s family struggles and Daniel Deronda’s ambiguous family history.

Daniel Deronda gets introduced to the Jewish community through Mirah Lapidoth who he rescues from a suicide attempt. While helping Mirah trace her lost family members, Daniel meets Mordecai, a Jewish visionary passionate about the Jewish people and their identity. Mordecai tries to make Daniel join in his vision and cause but Daniel has reservations about joining a cause he believes he has no connection with.

Eventually, Daniel traces his ancestry and discovers he is Jewish and that motivates him to follow Mordecai’s cause fully.

George Eliot addresses her recurring theme of family, gender, and social stratification then a novel theme of Semitism in Daniel Deronda.

What is George Eliot’s real name?

George Eliot’s real name is Mary Ann Evans. George Eliot is a pen name she used in publishing her novels. She was fluid in the use of her name as she signed off her birth name in many variations in her lifetime. Her father Robert Evans registered her name as Mary Anne Evans in her baptismal records, but she and other members of her family began spelling her name as Mary Ann Evans as she grew up and it was in this way that she signed her name for most of her life. Later she changed to Marian Evans in 1852 but reverted back to Mary Ann in 1880. She also adopted the surname of her lover George Lewes, signing off as Mary Ann Evans Lewes, then as Mary Ann Cross when she got married in 1880. Her memorial stone is written Mary Ann Cross (George Eliot)

What is George Eliot’s most famous work?

George Eliot’s most famous work is her first novel Adam Bede which was so well received that even Queen Victoria read and commended it in her journal. The novel was published in the year 1859 by Blackwood and Sons Publishers and it went through eight printings within the space of one year. It also had radio and television adaptations that starred some of Britain’s most popular actors.

Who was George Eliot’s lover?

George Eliot aka Mary Ann Evans’ lover was George Henry Lewes. They lived as a couple for twenty-four years but could not get married as George was already married in the eyes of the law and could not get legally divorced from his wife although separated from her. George Henry Lewes died in 1878 and in 1880, Mary Ann Evans married John Walter Cross.

Why did George Eliot change her name?

George Eliot’s birth name was Mary Ann Evans but she changed to George Eliot as a pen name for her novels to have her novels critiqued independently from her person and to protect her private life from public scrutiny. Also, gender played a role in her adoption of a pen name because female writers were frowned upon by some members of the society, and books from female writers were often not critiqued objectively, therefore, she adopted George Eliot who is a masculine pen name.

About Onyekachi Osuji

Onyekachi was already an adult when she discovered the rich artistry in the storytelling craft of her people—the native Igbo tribe of Africa. This connection to her roots has inspired her to become a Literature enthusiast with an interest in the stories of Igbo origin and books from writers of diverse backgrounds. She writes stories of her own and works on Literary Analysis in various genres.

Cite This Page

Osuji, Onyekachi " George Eliot Best Books 📚 " Book Analysis , https://bookanalysis.com/george-eliot/best-books/ . Accessed 18 March 2024.

It'll change your perspective on books forever.

Discover 5 Secrets to the Greatest Literature

George Eliot: A Biography

George eliot 1819-1880.

George Eliot was the pen name of Mary Ann Evans, a novelist who produced some of the major classic novels of the Victorian era, including The Mill on the Floss , Adam Bede , Silas Marner , Romola , Felix Holt , Daniel Deronda and her masterpiece, Middlemarch .

It is impossible to overestimate the significance of Eliot’s novels in the English culture: they went right to the heart of the small-town politics that made up the fabric of English society. Her novels were essentially political: Middlemarch is set in a small town just as the Reform Bill of 1832 was about to be introduced. She goes right into the minutia of the town’s people’s several concerns, creating numerous immortal characters whose interactions reveal Eliot’s deep insight into human psychology.

During the twentieth century there were numerous films and television plays and serials of her novels, placing her in a category with Shakespeare and Dickens. The distinguished literary critic, Harold Bloom, wrote that she was one of the greatest Western writers of all time.

George Eliot portrait

George Eliot lived with her father until his death in 1849. He was something of a bully and while in his house she lived a life of conformity, even regularly attending church. She was thirty when he died and it was at that point that her life took off. She travelled in Europe and on her return, with the intention of writing, she was offered the editorship of the journal, The Westminster Review . She met many influential men and began an affair with the married George Lewes. They lived together openly, something that wasn’t done at the time, and, when she became famous after the publication of her first novel , Adam Bede , when she was forty, using the name George Eliot, their domestic arrangements scandalised Victorian society.

Lewes’ health failed and after his death she married John Cross, a literary agent twenty years her junior. After Adam Bede more novels followed swiftly on its heels.

She died in 1880, aged sixty-one, and is buried in Highgate Cemetery beside George Lewes.

Read more about England’s top writers >> Read biographies of the 30 greatest writers ever >>

Interested in George Eliot? If so you can get some additional free information by visiting our friends over at PoemAnalysis to read their analysis of Eliot’s poetic works .

- Pinterest 0

Leave a Reply

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- World Biography

George Eliot Biography

Born: November 22, 1819 Warwickshire, England Died: December 22, 1880 London, England English author and novelist

George Eliot was the pen name (a writing name) used by the English novelist Mary Ann Evans, one of the most important writers of European fiction. Her masterpiece, Middlemarch, is not only a major social record but also one of the greatest novels in the history of fiction.

Mary Ann's youth and early career

Mary Ann Evans was born November 22, 1819, in Warwickshire, England, to Robert Evans, an estate agent, or manager, and Christiana Pearson. She lived in a comfortable home, the youngest of three children. When she was five years old, she and her sister were sent to boarding school at Attleborough, Warwickshire, and when she was nine she was transferred to a boarding school at Nuneaton. It was during these years that Mary discovered her passion for reading. At thirteen years of age, Mary went to school at Coventry. Her education was conservative (one that held with the traditions of the day), dominated by Christian teachings.

Mary Ann completed her schooling when she was sixteen years old. In her twenties she came into contact with a circle of people whose thinking did not coincide with the opinions of most people and underwent an extreme change of her beliefs. Influenced by the so-called Higher Criticism—a largely German school that studied the Bible and that attempted to treat sacred writings as human and historical documents—she devoted herself to translating these works from the German language to English for the English public. She published her translation of David Strauss's Life of Jesus in 1846 and her translation of Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach's Essence of Christianity in 1854.

In 1851 Evans became an editor of the Westminster Review, a sensible and open-minded journal. Here, she came into contact with a group known as the positivists. They were followers of the doctrines of the French philosopher (a seeker of knowledge) Auguste Comte (1798–1857), who were interested in applying scientific knowledge to the problems of society. One of these men was George Henry Lewes (1817–1878), a brilliant philosopher, psychologist (one who is educated in the science of the mind), and literary critic, with whom she formed a lasting relationship. As he was separated from his wife but unable to obtain a divorce, their relationship was a scandal in those times. Nevertheless, the obvious devotion and long length of their union came to be respected.

Becomes George Eliot

In the same period Evans turned her powerful mind from scholarly and critical writing to creative work. In 1857 she published a short story, "Amos Barton," and took the pen name "George Eliot" in order to prevent the discrimination (unfair treatment because of gender or race) that women of her era faced. After collecting her short stories in Scenes of Clerical Life (2 vols., 1858), Eliot published her first novel, Adam Bede (1859). The plot was drawn from a memory of Eliot's aunt, a Methodist preacher, whom she used as a model for a character in the novel.

Eliot's next novel, The Mill on the Floss (1860), shows even stronger traces of her childhood and youth in small-town and rural England. The final pages of the novel show the heroine reaching toward a "religion of humanity" (the belief in human beings and their individual moral and intellectual abilities to work toward a better society), which was Eliot's aim to instill in her readers.

In 1861 Eliot published a short novel, Silas Marner, which through use as a school textbook is her best-known work. This work is about a man who has been alone for a long time and who has lost his faith in his fellow man. He learns to trust others again by learning to love a child who he meets through chance, but whom he eventually adopts as his own.

In 1860 and 1861 Eliot lived abroad in Florence, Italy, and studied Renaissance (a movement that began in fourteenth-century Italy, that spread throughout Europe until the seventeenth century, with an emphasis in arts and literature) history and culture. She wrote a historical novel, Romola (published 1862–1863), set in Renaissance Florence. This work has never won a place among the author's major achievements, yet it stands as a major example of historical fiction.

Middlemarch

Eliot did not publish any novels for some years after Felix Holt, and it might have appeared that her creative thread was gone. After traveling in Spain in 1867, she produced a dramatic poem, The Spanish Gipsy, in the following year, but neither this poem nor the other poems of the period are as good as her nonpoetic writing.

Then in 1871 and 1872 Eliot published her masterpiece, Middlemarch, a broad understanding of human life. The main strand of its complex plot is the familiar Eliot tale of a girl's understanding of life. It tells of her awakening to the many complications involved in a person's life and that she has not used the true religion of God as a guide for how she should live her life. The social setting makes Middlemarch a major account of society at that time as well as a work of art. The title—drawn from the name of the fictional town in which most of the action occurs—and the subtitle, A Study of Provincial Life, suggest that the art of fiction here develops a grasp of the life of human communities, as well as that of individuals.