Top 50 Biochemistry Project Topics [Updated]

Biochemistry is the cornerstone of comprehending life’s basic chemical processes within living organisms. With its interdisciplinary nature, biochemistry encompasses a vast array of topics, each offering unique insights into the intricacies of biological systems. In this blog, we’ll embark on a journey through various biochemistry project topics, shedding light on their significance and potential impact.

How To Select Biochemistry Project Topics?

Table of Contents

Selecting a biochemistry project topic can be an exciting yet daunting task. Here are some steps to help you navigate the process and choose the right topic for your interests and goals:

- Assess Your Interests and Goals: Start by reflecting on your interests within the field of biochemistry. Are you fascinated by metabolic pathways, molecular biology, or environmental biochemistry? Consider your long-term goals, whether they involve pursuing a career in research, academia, or industry.

- Explore Current Trends and Research Areas: Stay updated on the latest advancements and trends in biochemistry by reading scientific journals, attending seminars, and following researchers in the field. Identify emerging areas of interest or unresolved questions that intrigue you.

- Consider Your Skills and Resources: Evaluate your skills, background knowledge, and available resources when selecting a project topic. Select a topic that matches your skills and resources, ensuring it’s manageable within your time frame, equipment availability, and mentorship access.

- Consult with Mentors or Advisors: Seek guidance from professors, mentors, or advisors who can provide insight and advice on selecting a project topic. They can offer valuable perspectives based on their expertise and experience in the field.

- Brainstorm Potential Topics: Brainstorm a list of potential project topics based on your interests, goals, and the input you’ve gathered from mentors and advisors. Consider both broad topics and specific research questions that intrigue you.

- Narrow Down Your Options: Evaluate each potential topic based on factors such as its relevance, novelty, feasibility, and potential impact. Narrow down your options to a few promising topics that you feel passionate about and that align with your goals.

- Research Each Topic: Conduct preliminary research on each selected topic to gain a deeper understanding of the existing literature, key concepts, and potential research directions. Identify gaps or areas where further investigation is needed.

- Consider Collaborative Opportunities: Explore opportunities for collaboration with other researchers, laboratories, or institutions that may offer resources, expertise, or access to specialized equipment needed for your project.

- Seek Feedback: Once you’ve narrowed down your options, seek feedback from mentors, peers, or other experts in the field. They can provide valuable insights and help you refine your project topic before moving forward.

- Make a Decision: Based on your research, reflections, and feedback, make a final decision on your biochemistry project topics. Choose a topic that inspires you, aligns with your interests and goals, and has the potential to contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

Top 50 Biochemistry Project Topics: Category Wise

General biochemistry.

- Elucidating the Mechanisms of Enzyme Catalysis

- Investigating Cellular Metabolic Pathways: From Glycolysis to Oxidative Phosphorylation

- Analysis of Biomolecular Structures: Proteins, Nucleic Acids, Lipids, and Carbohydrates

- Understanding the Role of Biochemical Signaling in Cellular Communication

- Biochemical Basis of Drug Action and Pharmacokinetics

Molecular Biology

- Regulation of Gene Expression: Transcriptional and Post-transcriptional Control Mechanisms

- Genome Editing Technologies: CRISPR-Cas9 and Beyond

- Molecular Mechanisms of DNA Replication and Repair

- Protein Synthesis and Folding: From Ribosome to Functional Protein

- Investigating RNA Biology: Structure, Function, and Regulation

Metabolic Biochemistry

- Regulation of Cellular Metabolism: Hormonal and Nutritional Control Mechanisms

- Biochemical Pathways in Disease: Metabolic Disorders and Dysregulation

- Lipid Metabolism: Biosynthesis, Breakdown, and Regulation

- Molecular Basis of Diabetes Mellitus: Insights into Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Strategies

- Metabolomics: Profiling Metabolic Changes in Health and Disease

Biochemical Techniques

- Chromatographic Techniques in Biochemistry: Principles and Applications

- Spectroscopic Methods for Biomolecular Analysis: UV-Vis, Fluorescence, and NMR Spectroscopy

- Mass Spectrometry in Proteomics: Advances in Analytical Methods and Data Interpretation

- Structural Biology Techniques: X-ray Crystallography, Cryo-EM, and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

- Applications of Bioinformatics in Biochemistry: Sequence Analysis, Protein Structure Prediction, and Systems Biology

Health and Medicine

- Biochemical Markers of Disease: Diagnostic and Prognostic Applications

- Pharmacogenomics: Personalized Medicine and Drug Response Prediction

- Cancer Biology: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets

- Neurochemistry: Understanding the Biochemical Basis of Brain Function and Dysfunction

- Immunology and Biochemistry: Intersections in Immune Cell Signaling and Regulation

Environmental Biochemistry Project Topics

- Bioremediation of Environmental Pollutants: Microbial and Enzymatic Approaches

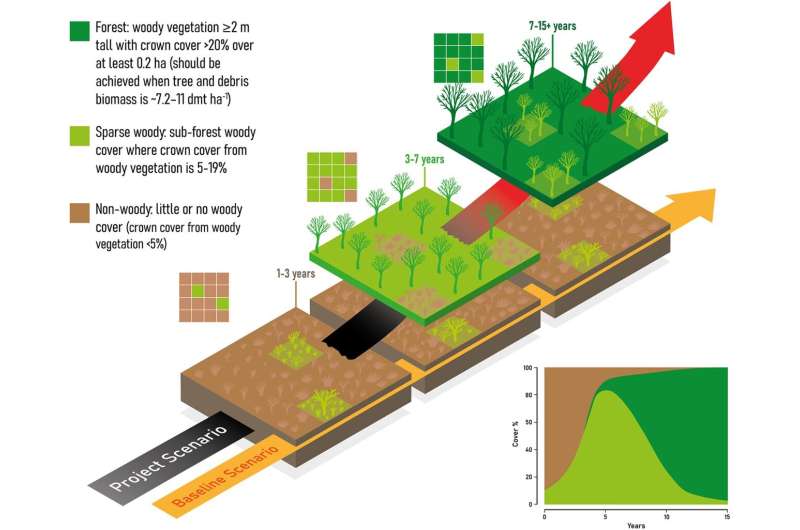

- Biogeochemical Cycling of Nutrients: Nitrogen, Carbon, and Phosphorus Cycling in Ecosystems

- Environmental Toxicology: Molecular Mechanisms of Toxicity and Detoxification

- Climate Change and Biochemistry: Impacts on Global Biogeochemical Cycles

- Biofuels and Renewable Energy: Harnessing Biomass for Sustainable Energy Production

Emerging Trends

- Systems Biology Approaches in Biochemistry: Integrating Omics Data for Holistic Understanding

- Synthetic Biology: Designing and Engineering Biological Systems for Novel Applications

- Nanotechnology in Biochemistry: Applications in Drug Delivery, Imaging, and Sensing

- Biochemical Engineering: Bioprocess Optimization and Bioreactor Design

- Bio-inspired Materials: Mimicking Nature for Innovative Biomaterials and Devices

Biotechnology and Industry

- Industrial Enzymes: Production, Optimization, and Applications in Biocatalysis

- Biopharmaceuticals: Development, Production, and Quality Control

- Bioreactor Design and Scale-up: Challenges and Solutions in Bioprocess Engineering

- Biosensors and Bioanalytical Techniques: Rapid Detection and Quantification of Biomolecules

- Bio-based Materials: Sustainable Alternatives for Packaging, Textiles, and Construction

Food and Nutrition

- Nutritional Biochemistry: Understanding the Biochemical Basis of Nutrient Requirements

- Food Processing and Biochemistry: Impact on Nutrient Composition and Bioavailability

- Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals: Bioactive Compounds and Health Benefits

- Nutrigenomics: Interactions between Diet, Genetics, and Health

- Food Allergies and Intolerances: Molecular Mechanisms and Diagnostic Tools

Agricultural Biochemistry

- Plant Biochemistry: Metabolic Pathways and Secondary Metabolites

- Biochemical Basis of Crop Improvement: Breeding for Stress Tolerance and Nutritional Quality

- Soil Biochemistry: Nutrient Cycling, Microbial Communities, and Soil Health

- Plant-Microbe Interactions: Signaling Pathways and Defense Mechanisms

- Biofortification : Enhancing Nutritional Quality of Crops through Genetic and Agronomic Approaches

Tips To Make Biochemistry Projects

- Choose an Engaging Topic: Select a biochemistry topic that interests you and aligns with your goals. Consider its relevance, novelty, and potential impact on the field.

- Define Clear Objectives: Clearly define the objectives of your project, including the research questions you aim to answer and the hypotheses you plan to test.

- Conduct Thorough Literature Review: Familiarize yourself with the existing literature on your chosen topic. Identify gaps in knowledge, conflicting findings, and areas for further investigation.

- Design Experimental Protocols: Develop detailed experimental protocols outlining the procedures, materials, and equipment needed to conduct your research. Consider potential variables, controls, and replicates to ensure the validity of your results.

- Acquire Necessary Skills: Acquire the necessary laboratory skills and techniques required for your project. Seek guidance from mentors, attend workshops, and practice hands-on training to develop proficiency in biochemical methods.

- Adhere to Safety Guidelines: Prioritize safety in the laboratory by following standard operating procedures, wearing appropriate personal protective equipment, and handling hazardous materials with caution.

- Collect Data Systematically: Conduct experiments meticulously, recording data accurately and consistently. Keep detailed records of your observations, measurements, and experimental conditions for later analysis.

- Analyze Data Effectively: Use appropriate statistical methods and software tools to analyze your data effectively. Interpret your findings critically, identifying trends, correlations, and significant results.

- Communicate Your Findings: Present your research findings clearly and concisely through written reports, oral presentations, and visual aids such as posters or slides. Tailor your communication to your target audience, whether it’s fellow researchers, educators, or the general public.

- Seek Feedback and Collaboration: Solicit feedback from peers, mentors, and experts in the field to refine your project and address any challenges or limitations. Consider collaborating with other researchers or laboratories to leverage resources and expertise.

- Stay Organized and Manage Time: Stay organized throughout the project timeline, setting milestones, deadlines, and priorities. Break down large tasks into smaller manageable steps and allocate time effectively to meet project goals.

- Reflect and Iterate: Reflect on your project experience, including successes, setbacks, and lessons learned. Identify areas for improvement and consider how you can refine your approach in future projects.

In conclusion, biochemistry offers a diverse range of captivating topics, spanning molecular biology, metabolic pathways, and applications in various fields.

By following the outlined tips, researchers can navigate project selection, planning, and execution effectively. Embrace curiosity, collaboration, and continuous learning to make meaningful contributions to scientific understanding.

With dedication and passion, biochemistry projects have the potential to drive innovation and shape the future of healthcare, environmental sustainability, and beyond.

Related Posts

Step by Step Guide on The Best Way to Finance Car

The Best Way on How to Get Fund For Business to Grow it Efficiently

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Enjoy a completely custom, expertly-written dissertation. Choose from hundreds of writers, all of whom are career specialists in your subject.

Top 80 Biochemistry Research Topics

Biochemistry is simply the study of life. Enrolling in a biochemistry course requires you to extensively study the biological and chemical functions of living organisms, which equips you with the best biochemistry research topic ideas as you progress with your study. But again, all this is not a walk in the park.

Are you a student looking forward to writing a research paper that your examiners or teachers would be happy to read and award you an excellent score? We’ve shared the biochemistry research topics list across various subjects in this article to help you know what the best topics look like. Be sure to go through this piece in its entirety.

Biochemistry Research for Students (Preparation and Ideas)

In most universities, a senior biochemistry research project is a must before you complete your biochemistry coursework. But that’s not all. At various points of your study, whether studying pure biochemistry or related courses like molecular biology, examiners will require you to write a biochemistry research essay, term paper, or thesis.

To show you are focused on your studies and understand biochemistry better, come up with interesting biochemistry topics, and structure your work perfectly. A biochemistry research paper should capture the examiner’s interest and allow you to prove the content extensively. Ensure the topic is also manageable and compliant with your research environment.

With that, you will get things done in the nick of time without compromising on the quality of your work. No examiner will have a problem with a research essay, assignment, or dissertation that has sense and follows the academic rules. In fact, well-proposed biochemistry research ideas attract lots of funding, and you might be lucky to have a breakthrough in your early career.

Most of the biochemistry topics for research ideas revolve around:

- Structure and functioning of various body cells.

- Biochemical reactions in humans and plants.

- Heredity in living organisms.

- Pharmacology and pharmacognosy.

- DNA, RNA, and proteins in plants and animals.

- Molecular nature of all the bio-molecules.

- Micro-organisms.

- Enzymes, bioenergetics and thermodynamics.

Interesting Topics in Biochemistry

Many students struggle to think of interesting topics for their courses, and that’s not exceptional in biochemistry. You’ll notice that most of the topics’ interests depend on what a student is passionate about. Here are some interesting biochemistry topics to check out:

- Understanding the role of microbial itaconic acid production during fungi synthesis.

- Membrane biology and ion transport process in the innate immune response.

- Inhibition of sprouty2 in periodontal ligament cells and their extensive biological effects.

- Peptide and protein structure in membranes: what role do they play in cell membrane formation?

- Understanding the evolution of microbial infections and related effects in the existing surroundings.

- The role of B cell receptors in infections and vaccine production.

- Human health and bacteriophages of different kinds: How the two correlate.

- AN analysis of biofilm formation: From therapeutics to molecular mechanisms, and everything in between.

- Close comparison and analysis of nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) in mice and humans.

- Understanding the relationship between NDR1/2 and mob-based proteins in cell cycle damage signaling.

Biochemistry Topics for Presentation

If you have an incoming presentation, you must pick your topics carefully. Presentations can be a challenge at times. While some individuals in the audience might not have extensive knowledge of the subject, you must have a detailed understanding of your topic to score better. Here are some of the best biochemistry presentation topics:

- A stepwise understanding of the human immune system and the role played in cell regeneration during an infection.

- A deep analysis of different plant pathologies with a focus on phytochemicals present and their roles.

- A look at the biochemical process that leads to apoptosis in patients with stage IV breast cancer.

- Understanding the close relationship in terms of practice in biochemistry and pathological psychiatry.

- Understanding different types of polymorphism and how they affect the DNA of human beings.

- How hormone formation in children is dependent on the environment and child’s health condition.

- The role of human cloning in the production and consumption of various types of vaccines.

- The relationship between human molecular adaptation and diet: Does diet play a role?

- Understanding how biological processes are dependent on the functioning of the human central nervous system.

- Comparison of mice and human circulatory system: Functioning, susceptibility, capacity, and features.

Hot Topics in Biochemistry

Biochemistry has a vast range of hot topics to explore. Since you might not have the chance to write about everything concerning the course, our suggestions narrow your search efforts. Take a look at some of the hot topics in biochemistry below:

- How professional breast cancer detection and screening is changing the lives of university students.

- The revolution of tissue clearing techniques for optical microscopy as witnessed for the past five years.

- Clinical features of acute copper sulfate poisoning and role of biochemistry in management interventions.

- The role of malt in various beer quality and effects on beer stability: Industrial biochemistry of beer making.

- Solid and liquid-state fermentation in the production of biochemical supplements for human and animal consumption.

- Controlled mixed fermentation as witnessed in pharmaceutical product making over the years and the new normal.

- The roles of polyphosphate on the virulence of Erwina caratovora bacteria in a range of plants.

- An extensive comparison of the significant aspects of biochemical studies at the college and university level in the last half-century.

- Analysis of molecular genetics and its close relationship with muscular dystrophy in men and women.

- Supporting evidence on children’s growth and development in countries using genetically modified organisms feeding products.

Project Topics for Biochemistry

Would you like to write a project topic on biochemistry that might change the world? Then you need to work on something that excites and allows you to develop a deep interest in your course. Project topics in biochemistry are not complicated, provided you are willing to challenge yourself and learn. Here are some of them for inspiration.

- Breast cancer and obesity in women of younger age; the clinical analysis from a biochemistry perspective.

- Understanding biochemistry of biomolecules and amino acids and their clinical application in drugs and supplement making.

- The future of artificial intelligence and its relevance to biochemistry: The gradual changes witnessed over the last four years.

- Understanding stability of 81 analytes in human blood, serum, and plasma during diagnosis in clinical biochemistry set up.

- History of clinical biochemistry and why it matters to modern human medicine.

- Transforming the liver function tests with new biochemistry diagnostic simple tools; how to make things result-oriented

- The role of clinical biochemistry in helping us understand the human immune system.

- Understanding and redefining the role of the human bones: How biochemistry transforms the narrative on human bones predisposition.

- A detailed clinical biochemistry analysis during pregnancy: tests associated with pregnancies and early child development.

- The rise of clinical biochemistry in the present times, from introductory chemistry of life to foundation on infections and disease interventions.

Biochemistry Research Topics for Undergraduates

Choosing an ideal biochemistry research topic as an undergraduate student taking biochemistry at the college or university level can be a complex process for you. We have ten topics that you can choose to base your research on. Let’s take a look at the best biochemistry research topics for undergraduates’ topics:

- Microbial food spoilage, resulting disorders, and the best biochemistry control approach to leverage.

- Comparative examination of serum calcium level among males using biochemistry testing techniques.

- Phytochemical analysis of specific tomato products available in the market for public health safety.

- The oxidative stress status of mice fed on oil bean seed meal and show the same applies to biochemical processes in humans.

- How biochemical production of top-quality bar soaps compares with most detergents you see in the market today.

- What are the health dangers associated with lead in water consumed in most universities?

- Critical analysis of Pterocarpus mildbreadii (oha) seed: A detailed phytochemical review.

- How to use biochemistry synthesis pathways to create a compound that prevents reactions from taking place.

- Evaluation of bacteria components produced using pure starter culture in a biochemistry culture laboratory setup.

- What’s the bacteriological quality of meat products in most butcheries in town?

MCAT Biochemistry Topics

You must always take your Medical College Admission Test seriously if you want to get a chance to join your favorite medical school. The test gives you a chance to show that you’re ready to handle the program and maintain an excellent performance throughout. Since you’re looking to get admission, here are the best MCAT biochemistry topics you might want to consider:

- Application of mathematical concepts and techniques in biochemistry and their role in general medicine.

- How catabolic and anabolic enzyme reactions contribute to cell functionality: Data-based enzymatic reasoning and graphical representations.

- Chemical and physical foundations of biological systems that help us appreciate human anatomy.

- How critical analysis and reasoning skills acquired in biochemistry play a significant role in medical schools.

- How multiple biosynthetic pathways like the citric acid cycle and glycolysis influence human health and functionality?

- A look at the psychological, social, and biological foundations of behaviors in relation to human biomolecules.

- Understanding the biochemical basis of human psychology.

- Critical analysis of biochemistry study areas and how they transform medicine.

- Understanding the relationship between Omega-3 fatty acids and blood glucose levels in adults.

- How fruits and vegetables regulate blood sugar in patients with diabetes: Biochemical pathways and mechanisms.

Popular Biochemistry Research Paper Topics

As a student pursuing biochemistry, you should be aware of some topics to expect during your program. Luckily, a lot is happening in the biochemistry field, giving you a chance to explore the subject even better. Take your time and go through these popular biochemistry research paper topics we have suggested below.

- How does chemical energy flow in human cells during metabolism?

- Understanding the primary chemical processes and their close relationship to the functionality of living organisms.

- How biotechnology and molecular biochemistry continues to transform genetics and botany in the modern world.

- How has the Coronavirus impacted the study and application of biochemistry for the last one year?

- How common bleaching agents react with human skin and biochemistry interventions that solve the matter once and for all.

- How do laboratory and medical-based practical experiments help undergraduate students understand biochemistry better?

- How can factories leverage biochemistry and help achieve the goal of clean energy in cities and congested towns?

- What biochemical activities are involved in drug production and testing? Pharmaceutical quality assurance and control

- Discussing and analyzing the chemical properties of carbohydrates in energy formulation.

- What factors necessitate fatty acids beta-oxidation? Fatty acids as super fuel in the human bodies functioning.

Current Biochemistry Topics

There’s no better way to show that you’re a sharp and informed student than knowing what’s happening in the biochemistry academic and practical world. Knowing current biochemistry topics is one way to showcase your awareness. We have compiled this list to help you create a top-quality research paper. Here we go!

- How do hydrocarbons in amino acids impact biochemical reactions when the human body gets subjected to medication?

- Why biochemistry research is promising when it comes to developing the best methods of initiating new medications to patients.

- Understanding the covid-19 vaccines chemical properties and reactions in adult men and women.

- Explaining various reactions to vaccines in the trial stage and how biochemistry has helped achieve the desired vaccines effectiveness.

- What are the roles of biochemically developed rotavirus vaccines in acute gastroenteritis among infants?

- How to best preserve plant extracts meant for experiments in biochemistry? Plant biochemistry and biotechnology research.

- The relationship between different types of brain cancer with radiation exposure and genetics.

- Understanding measles among infants and the most effective biochemistry based vaccine remedy

- The role of biochemistry in governing cell motility during various stages of development.

- The role of microscopy, scanning, and serum medical examinations in biochemistry.

Get Biochemistry Writing Help

Are you confused about the best biochemistry project topics to work on? The above topics are an ideal starting point. But completing your assignment with the huge workload that comes with biochemistry is a significant problem. Worry not because you can now get biochemistry writing help from us.

Whether it is on pharmacology, chemical biology, biotechnology, molecular genetics, molecular biology, microbiology, chemistry, or related disciplines of biochemistry, you can depend on us. Our biochemistry assignments help online assure top-quality biochemistry papers. Get in touch with us today and enjoy:

- Quality papers that attract the highest grades possible.

- Many years of writing biochemistry assignments online.

- Assignments that are professionally written.

- Quality work on any nature of the topic.

- On-time assignment delivery.

Ready to get biochemistry research assignment help and score better grades? Go ahead and initiate a conversation with our dissertation consultants today. We’re prepared for all biochemistry paper topics!

Frequently Asked Questions

Richard Ginger is a dissertation writer and freelance columnist with a wealth of knowledge and expertise in the writing industry. He handles every project he works on with precision while keeping attention to details and ensuring that every work he does is unique.

Succeed With A Perfect Dissertation

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

As Putin continues killing civilians, bombing kindergartens, and threatening WWIII, Ukraine fights for the world's peaceful future.

Ukraine Live Updates

- Write my thesis

- Thesis writers

- Buy thesis papers

- Bachelor thesis

- Master's thesis

- Thesis editing services

- Thesis proofreading services

- Buy a thesis online

- Write my dissertation

- Dissertation proposal help

- Pay for dissertation

- Custom dissertation

- Dissertation help online

- Buy dissertation online

- Cheap dissertation

- Dissertation editing services

- Write my research paper

- Buy research paper online

- Pay for research paper

- Research paper help

- Order research paper

- Custom research paper

- Cheap research paper

- Research papers for sale

- Thesis subjects

- How It Works

202 Interesting Biochemistry Research Topics For Any Taste

Science-related courses are not everyone’s favorite. The few passionate and enthusiastic minds that delve into this field can also attest to its technical nature. With the intensive research, one has to perform biochemistry; it is no secret that professional assistance is inevitable. We have collated a list of the crème de la crème biochemistry research paper topics for your inspiration. Keep reading this post to the end to identify them and use one of them in your project today!or buy thesis online

What Are Biochemistry Research Topics?

How to find biochemistry paper topics, easy biochemistry research topics list, interesting biochemistry topics, cool biochemistry topics for quality grades, popular ideas for biochemistry research projects, actual topics in biochemical research, good biochemistry science fair projects, hot topics in biochemistry, remarkable biochemistry project topics, topics that deal with various fields of biochemistry, current topics in biochemical research.

- Get Biochemistry Paper Writing Help Today

Biochemistry is a science-related field with roots in chemistry and biology – deals with the organic chemistry of compounds and processes occurring in organisms. This field seeks to understand biology within the context of chemistry.

Therefore when we talk about biochemistry research topics, we are dealing with all the relevant aspects of biochemistry. Such issues tend to identify problems in this field and try to bring out working solutions or recommendations in the end. Like any other research topic, these also seek to explore researched and least researched areas of biochemistry and add knowledge to the field.

Although most college and university students perceive this to be a daunting task, it is the reverse of it all. Biochemistry is something that we apply in our everyday life, and thus we can easily find such topics. Nonetheless, here are some concrete places you can begin your search from:

The biochemistry books on your library shelf Reputable online sites that major in biochemistry Articles, journals, conference papers, and orations on biochemistry Latest news headlines Previous theses and research papers on biochemistry

With all these sources, you are as prepared as a soldier for battle. Nothing can stop you from writing biochemistry topics that will yield top grades. For those who wish to have something to start them off, here are 202 of the best biochemistry project topics!

- How chemical processes related to living organisms

- Discuss the process of information flow through biochemical signaling

- How does chemical energy flow through metabolism?

- The role of biochemical processes in giving rise to the complexity of life

- How biochemistry transformed botany and genetics in the 20 th century

- Various health dangers of sodium chloride in food

- The role of laboratory technicians in advancing research in biochemistry

- How developing nations are making strides in the field of biochemistry

- The impact of coronavirus on the study and application of biochemistry

- The efficacy of catalysts and enzymes in biological reactions

- Phytochemical analysis of the various dyes sold in the market today

- How bleaching agents interact with the human skin

- Effects of technological advances on the study of biochemistry in universities

- The rate of employment among biochemistry graduates in the United States

- Discuss the chemical compositions of potassium permanganate

- An evaluation of the chemical processes involved in the extraction of oxygen from the air

- Effects of methanol on the human lungs and liver

- Factors that necessitate the oxidation of various metals

- How factories can contribute to the Standard Development Goals on clean energy

- Chemical activities involved in the rusting of metals

- Why does steel remain stainless as compared to other metals?

- The role of practical experiments in understanding biochemistry

- How to detect Mycobacterium Ulcerans on the human skin

- Discuss the environmental reservoirs of most biological enzymes and catalysts

- Risks associated with researching in a biochemistry lab

- The effect of ecological conditions on extracts used in the lab

- Evaluate the alkaloidal isolates of a plant

- Analyze the various anti-inflammatory medicinal plants found in the tropical regions

- Investigate the process of producing pro-inflammatory eicosanoids

- What is the therapeutic action of anti-inflammatory medicinal plants?

- The impact of herbal preparations on treating skin diseases

- How to destabilize Lysozyme activity

- The impact of various temperature ranges on enzyme activity

- What is the role of alpha crystalline in a concentration?

- Factors that necessitate insulin resistance in human bodies

- Biochemistry experiments that have helped in treating cardiovascular diseases

- What is the relationship between T2DM and a high level of hepcidin?

- Factors that necessitate the regulation of iron homeostasis

- Evaluate the pathogenesis of diabetes and its complications

- The impact of maternal serum on pregnant women

- How to determine the amount of protein in the urine

- Discuss the release of placental toxic factors and their impact on blood circulation

- Evaluate the toxicological effects of Desmodium Adscendens in rats

- The impact of high doses of the freeze-dried extracts on biochemical reactions

- How to preserve plant extracts for biochemical experiments

- Discuss the various pathogenic risks associated with breast cancer

- An analysis of the multi-factorial diseases among women in the United States

- Biological factors that necessitate promoting tumor growth

- Evaluate the role of immunoglobulin G receptors in the study of clinical malaria

- How to determine the antigen-binding capabilities of the receptors

- A biochemical perspective of the gene encoding process for receptors

- Molecular methods of investigating variations in genes: A case study of PCR

- Biological processes that cause the inflammation of the intestinal mucosa

- The role of Rotaviruses in causing Acute gastroenteritis (AGE) among children

- How iron Chelators affect the various bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma Brunei

- Discuss how clinicians determine the effectiveness of a particular drug

- Evaluate the emergence of drug resistance among pregnant mothers

- Alternative forms of therapy to drug toxicity in humans

- How iron Chelators deferoxamine exhibits itself in Trypanosoma Brunei

- Factors that inhibit cell growth and interfere with the activity of iron-dependent enzymes

- Discuss the vitro effects of phenolic acids

- The impact of variant frequencies in biochemical reactions

- Biochemical processes that may lead to severe coronary malfunctions

- Genetic factors associated with variability in individuals

- How do different people respond to various vaccines during the clinical trials stage

- The method of initiating a new drug in a patient

- Evaluate the biochemical properties of the coronavirus

- The role of sewage sources and disposal points in contributing to the survival of pathogens

- How to determine relative molecular weights in the lab

- The susceptibility of bacteria to antibiotics

- Compare and contrast herbal preparations and scientific research processes

- How to isolate pathogens from various food sources

- Discuss the efficacy of using the indicator bacteria strains

- How electron microscopy helps in isolating viruses and bacteria

- The interrelationship between cellular and molecular biology

- Discuss the genetic models for understanding regulatory mechanisms for homeostasis

- What are the tools that regulate the cell population?

- How to deal with pathologic disorders: A case study of Osteoporosis

- Biochemical inferences to metastatic bone disease

- How to discover embryonic malformations in pregnant women

- Factors that disrupt signaling pathways and transcription factor networks

- Evaluate various bone tissue from humans and animals

- A technological analysis of genetic and proteomic processes

- Discuss the various strides made in vivo molecular imaging

- The role of scanning and electron microscopy in biochemistry

- Effects of high-resolution micro-computed tomography in determining the accuracy of biochemical experiments

- How to detect defects in cell biology: A case of soft tissue sarcoma

- Investigate the advancements made in cell growth regulation

- Discuss the epigenetic and genetic regulation of oncogenes

- Analyze the factors that regulate the cell cycle

- How to control the segregation of chromosomes

- Why scientists need to govern cell motility

- Discuss the relationship between nuclear structure and chromatin structure

- Explore how the nucleus organizes nucleic acid metabolism architecturally

- How to determine the atomic matrix of an RNA

- What causes the nuclear lamina to have interconnected structures?

- Discuss the process of DNA replication in a laboratory

- What makes the RNA transcription process a complex one?

- How to package DNA into active or silenced chromatin

- How changes in the RNA and DNA cause diseases such as cancer

- Discuss the kinetic characterization of the homeostasis process

- How to determine the structure of new clotting factors

- Effects of platelets in the identification of genetic risk markers

- Why enzymes are necessary for almost every aspect of biochemistry

- Discuss the process of recognizing a substrate by an enzyme

- Evaluate the quantitative and structural approach to the study of enzymes

- How to determine if selenium contains enzymes

- Analyze the co-factors and enzymes involved in the coagulation cascade

- Why structural biology should be a core research discipline in colleges

- Analyze the X-ray structures of iron-binding in proteins

- Factors that lead to the clotting of blood in humans

- What are the DNA-protein complexes that are necessary for replication?

- Discuss the regulation mechanisms of the transcriptional process

- The role of synthetase – tRNA complexes

- Discuss the assembling and regulation procedures of the DNA replication fork

- How a synthetase distinguishes among dozens of tRNA species

- The process of repairing DNA double-strand breaks

- What goes on in the RNA transcription process?

- The necessity of recombination in predicting the stability of genomes

- Discuss the molecular processes involved in carcinogenesis

- How to design new anti-tumor agents

- Experimental approaches to determining the instability of genomes

- Discuss site-directed mutagenesis of protein components

- Biochemical analysis of DNA synthesis

- Evaluate the properties of eukaryotic RNA polymerases

- The role of transcription factors in biochemistry

- What goes on in ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling?

- Discuss the various structural proteins that comprise the chromatin

- How to regulate transcription initiation and elongation

- Factors that affect post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression

- How to determine the active sweet components of artificial sweeteners

- A comparative analysis of serum calcium levels in geriatric men

- How to extract nutrients from plants

- Evaluate the nutritional profile of vegetables: A case of spinach

- How to produce starch from cassava

- Evaluate the phytochemical properties of soap

- Factors that lead to microbial food spoilers

- How to determine biochemical parameters in the laboratory

- A critical examination of Escherichia Coli in fecal pollution

- Discuss the chemical compositions of water near a lead industry

- Physic-chemical properties of yams and arrowroots

- The impact of supplementing the body with vitamins

- Effects of having fluorides in drinking water on the teeth

- The implication of acid rain to surrounding building structures

- Discuss the process of methanol leaf extraction

- The role of high-fat diets in causing obesity and heart diseases

- Concepts of analytical biochemistry

- Biotechnology and applied biochemistry

- How to produce deodorants using pawpaw leaves

- What causes the spontaneous flow of active polar gels?

- Discuss gene encoding in sorghum and cassava

- What causes destabilization in lysosomes?

- Evaluate some of the physicochemical processes that occur in living organisms

- Discuss the conditions that necessitate antibacterial activity of Thymus Vulgaris

- What are the optimum conditions for aqueous and ethanol extracts?

- How Cadmium affects humans and the surrounding environment

- Evaluate the fungal pathogens associated with tomatoes spoilage

- The role of taxonomic groupings in biochemistry

- How to produce protease using Aspergillus Flavus

- The process of extracting medicinal components of plants

- Effects of ethanol in causing corrosion

- The role of watermelon in fighting viral activities

- Plant science and medicine

- Structure of molecules

- Chemicals responsible for the immune system

- Cells accountable for body defense

- Why are pathogens dangerous?

- Energy release from bonds

- Structure of organelles

- How coordination occurs in various components of cells

- How the conversion of glucose occurs

- Process of heat generation

- Chemical effects of diseases

- Functions of bio elements

- The study of respiration

- How to extract energy from food

- Compounds necessary for body growth and development

- How to diagnose diseases using various biochemical procedures

- Why plant sugars are necessary for the process of photosynthesis

- How carbon dioxide enters the leaves through stomata

- The role of mitochondria, nucleus, Golgi bodies, and endoplasmic reticulum in the study of cell biology

- Discuss the functioning of various molecules of life

- Discuss the role of food additives in changing the way bacteria grows and develops

- How to determine mutation in the structure of the DNA of bacteria

- Discuss the process of deciding on a pregnancy test through urine samples

- How to detect potential genetic defects in the fetus

- Discuss the chromosomal abnormalities that lead to Down syndrome

- How the absence of enzymes in the body leads to metabolic disorders

- How biochemists insert the gene for human insulin into bacteria during genetic engineering

- The process of creating genetically identical organisms through cloning

- Evaluate the procedure of replacing a disease-causing gene through gene therapy

- Analyze the various properties and reactions of compounds in animals

- How to utilize compounds for body growth and development

- The study of plant biochemistry: A case study of respiration and Glycolysis

- How the structure of molecules affect metabolic reactions

- Describe the process of speeding up reactions by enzymes

- Discuss how catabolism and anabolism lead to the breaking down of larger molecules

- What are the various mechanisms of reactions that cause pollution?

- What are some of the emerging ethical and legal trends in biochemistry?

- How the study of biochemistry supports our understanding of diseases and health

- Discuss the contribution of biochemistry to innovative information and technological revolution

- The role of biochemistry in determining policies and legal standards: A case study of coronavirus

Get Biochemistry Paper Writing Help Today!

From the writing ideas above, you can note that topics in biochemistry are like the neighbor next door. They exist in almost every activity of our lives, from waking up to sleeping.

Are you still stuck with your biochemistry assignment and approaching the deadline? We offer affordable homework help in all fields of biochemistry. Let our expert biochemists help you score that A+ with ease.

Our trusted online assistance is all you need to unlock your potential. Give it a try today!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Thesis Helpers

Find the best tips and advice to improve your writing. Or, have a top expert write your paper.

171 Original Biochemistry Research Topics

Are you a student searching for original and captivating biochemistry research topics? Look no further! In this article, we present you with a comprehensive list of 171 free, unique, and thought-provoking biochemistry research topics. Whether you’re working on a thesis, dissertation, or class assignment, this list offers a wide range of interesting ideas to explore.

Additionally, we provide a short guide on how to do research for a biochemistry paper quickly, equipping you with valuable tips and strategies to streamline your writing process. This guide will help you navigate the complexities of biochemistry writing, allowing you to produce a high-quality paper in no time. Get ready to embark on an exciting journey of scientific exploration and academic success!

What Is Biochemistry?

Biochemistry is the scientific discipline that explores the chemical processes and molecules that occur within living organisms. It focuses on the study of biological macromolecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and lipids, and their roles in cellular functions, metabolism and the overall functioning of living systems.

How To Write An Excellent Biochemistry Paper

Before we get to the biochemistry research topics, we want to make sure you know how to conduct effective research for your paper. Make sure you follow these tips and tricks:

- Define your research question: Clearly state the main objective or question you want to address in your biochemistry paper.

- Conduct a literature review: Review relevant scientific literature to understand existing knowledge and identify research gaps.

- Utilize reputable sources: Gather information from trustworthy academic databases, peer-reviewed journals and reliable scientific websites.

- Take organized notes: Record important findings, references and evidence while reading, organizing them by subtopics or themes.

- Develop a research plan: Create a timeline and outline tasks, such as experiments or data collection, to stay organized.

- Analyze and interpret data: Carefully examine collected data and draw meaningful conclusions that support your research question.

The Latest Biochemistry Research Topics

Stay up-to-date with cutting-edge advancements in biochemistry research with these engaging and thought-provoking topics. Check out our latest biochemistry research topics:

- CRISPR-Cas9 for precise genome editing in biochemistry

- Epigenetics in cancer development and progression

- Protein misfolding and neurodegenerative diseases

- Nanotechnology in targeted drug delivery systems

- Gut Microbiome and human health

- Biochemical pathways in ageing and longevity

- Environmental pollutants and human metabolism

- Non-coding RNAs in gene regulation and disease

- Stem cells in regenerative medicine

- Metabolic pathways and personalized medicine

- Plant responses to environmental stress and climate change

- Mitochondrial bioenergetics and metabolic diseases

- CRISPR-based gene therapies for inherited disorders

Amazing Biochemistry Thesis Topic Ideas

Dive into the fascinating world of biochemistry with these captivating thesis topics that will captivate readers and showcase your knowledge. Here are our amazing biochemistry thesis topic ideas:

- The role of biochemistry in personalized nutrition

- Exploring the biochemical basis of addiction: Neurotransmitters and reward pathways

- Biochemical mechanisms underlying the benefits of exercise on mental health

- The impact of gut microbiota on brain function

- Biochemical processes in the treatment of autoimmune diseases

- Investigating the biochemical basis of food allergies

- The biochemistry of taste: Understanding the molecular basis of flavors

- Unraveling the biochemical mechanisms of memory formation

- Biochemical approaches to combating antibiotic resistance in bacteria

- Understanding the effects of environmental toxins on humans

- Investigating the biochemistry of sleep

- Biochemical processes underlying the aging of the skin

- The role of biochemistry in developing sustainable solutions for food production

Easy Biochemistry Topics

Simplify complex biochemistry concepts with these accessible topics that make learning and presenting information a breeze. Choose one of our easy biochemistry topics:

- Enzyme kinetics: Understanding the rate of biochemical reactions

- Protein structure and function: Exploring the building blocks of life

- Metabolism: Unraveling the chemical processes that sustain living organisms

- DNA replication: Investigating the mechanisms of genetic information duplication

- Cellular respiration: Examining how cells produce energy from nutrients

- Lipid metabolism: Understanding the breakdown and synthesis of fats

- Carbohydrate metabolism: Exploring the processing of sugars in living organisms

- Enzyme regulation: Studying how enzymes are controlled and regulated in cells

- Hormones and signaling: Investigating chemical messengers in biological communication

- Biochemical basis of diseases: Exploring the molecular mechanisms of illnesses

- Vitamins and minerals: Understanding the roles of essential nutrients in the body

- Biochemical analysis techniques: Examining methods used to study biological molecules

- Drug metabolism: Investigating how the body processes and eliminates medications

- Molecular genetics: Exploring the relationship between genes and biochemical processes

- Biochemical pathways: Mapping out the interconnected reactions that occur in cells

Awesome Topics In Biochemistry

Explore the wonders of biochemistry through these awesome topics in biochemistry that showcase the remarkable discoveries and breakthroughs in the field:

- Unraveling protein folding: Understanding three-dimensional structure formation

- Personalized medicine: Tailoring treatments based on individual profiles

- Decoding neurodegenerative diseases: Molecular mechanisms in Alzheimer’s

- CRISPR-Cas9 revolution: Gene editing’s impact on biochemistry

- Exploring plant defense biochemistry: Strategies against pathogens

- Combating antibiotic resistance: Innovative biochemistry approaches

- Gut-brain axis: Linking microbiota and brain function

- Synthetic biology’s potential: Novel biochemical design

- Cellular signaling: Decoding intracellular communication pathways

- Metabolic disorders: Unraveling molecular causes of diabetes

- Nanotechnology in biochemistry: Advancements in biomedical applications

- Photosynthesis biochemistry: Sunlight to plant energy conversion

- Protein-protein interactions: Analyzing dynamic protein connections

Advanced Biochemistry Topics

Challenge yourself with these sophisticated topics that delve into complex biochemistry theories and advancements. Check out our unique advanced biochemistry topics:

- Exploring the biochemical intricacies of gene regulation and epigenetics

- Biochemical mechanisms of cellular signal transduction

- Uncovering the role of biochemistry in stem cell biology

- Investigating the biochemical basis of neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s

- Biochemical processes underlying the progression of cancer

- The role of biochemistry in understanding metabolic disorders

- Probing the biochemical basis of pharmacokinetics

- Investigating the molecular mechanisms of protein folding diseases

- Understanding the biochemistry of lipid metabolism

- Exploring the biochemical basis of plant-microbe symbiosis

- Investigating the role of biochemistry in DNA repair mechanisms

- Unraveling the biochemistry of environmental pollutants

- Exploring the biochemical processes involved in cellular senescence

Biochemistry Science Topics

Stand out at your science fair with these innovative biochemistry science fair project ideas that combine biochemistry principles with hands-on experimentation:

- pH’s effect on enzyme activity

- Temperature’s impact on protein denaturation

- Sugar concentration and yeast fermentation

- Antioxidant properties of natural compounds

- Nutrient effects on plant growth

- Preservatives preventing food spoilage

- Light wavelengths and photosynthesis

- Vitamin C content in fruits and vegetables

- Antibiotics’ impact on bacterial growth

- Enzymatic browning in fruits and vegetables

- Soil types and nutrient availability for plants

- Pollutant effects on aquatic biomarkers

- Properties of natural and synthetic sweeteners

- Detergents breaking down grease and oil

Cool Topics In Biochemistry

Discover the coolest and most intriguing aspects of biochemistry with these topics that will impress and engage your audience. Pick one of our cool topics in biochemistry:

- CRISPR-Cas9: Targeted gene editing in biochemistry

- Biochemistry of Psychedelics and brain effects

- Biochemistry in extreme environments and life potential

- Extracellular vesicles: Intercellular communication mechanisms

- Venomous animals’ biochemistry and therapeutic potential

- Taste perception biochemistry and food preferences

- Biochemical basis of circadian rhythms and regulation

- Biochemistry’s role in understanding life origins

- Plant defense biochemistry against pathogens and pests

- Natural products’ biochemistry for drug development

- Human microbiome biochemistry and health influence

- Drug metabolism: Biochemical mechanisms and interactions

- Neurotransmitters’ biochemistry and brain function

Good Biochemistry Topics For Research

Embark on a research journey with these high-quality topics that offer ample opportunities for exploration and discovery in the field of biochemistry. These good biochemistry topics for research are original or you can delegate your work and use medical thesis writing services :

- Investigating the role of oxidative stress in age-related diseases

- Exploring the biochemistry of cancer metabolism

- Analyzing the biochemistry of drug delivery systems for improved efficacy

- Studying the role of epigenetics in gene expression and disease development

- Investigating the biochemical mechanisms of protein misfolding

- Understanding the biochemistry of cellular signaling pathways

- Exploring the biochemistry of lipid metabolism in metabolic disorders

- Investigating the biochemistry of DNA repair mechanisms and genome stability

- Analyzing the role of biochemistry in understanding the gut microbiome

- Studying the biochemical basis of neurotransmitter imbalances in psychiatric disorders

- Investigating the biochemistry of viral-host interactions

- Exploring the biochemical mechanisms underlying antibiotic resistance

- Analyzing the biochemistry of plant secondary metabolites

Interesting Biochemistry Topics

Capture attention and spark curiosity with these thought-provoking topics that explore fascinating aspects of biochemistry. All our interesting biochemistry topics are free to use:

- DNA nanotechnology: Building structures on a molecular scale

- Enzyme engineering: Designing catalysts for specific applications

- Metabolic profiling: Analyzing biochemical fingerprints for disease diagnosis

- Nanozymes: Harnessing nanomaterials with enzyme-like properties

- Biomolecular simulations: Modeling dynamic molecular behaviors using a computer

- Bioinformatics: Using computational tools to analyze biological data

- Synthetic biology: Designing and creating novel biological systems

- Lipidomics: Investigating the diverse roles of lipids in cellular processes

- RNA interference: Silencing gene expression for targeted therapies

- Glycobiology: Studying the function of carbohydrates in biological systems

- Chemical biology: Bridging Chemistry and biology for innovative research

- Metabolomics: Profiling small molecules to understand cellular metabolism

Biochemistry Research Topics For Undergraduates

Delve into research as an undergraduate student with these accessible and meaningful biochemistry research topics for undergraduates that align with your academic level:

- Analyzing the effects of antioxidants on oxidative stress in cellular models.

- Investigating the role of specific enzymes in metabolic pathways.

- Studying the biochemical basis of drug interactions and their impact on therapeutic outcomes.

- Examining the effects of environmental pollutants on cellular health and function.

- Investigating the biochemistry of plant compounds with potential antimicrobial properties.

- Exploring the biochemical mechanisms underlying the development of antibiotic resistance.

- Analyzing the effects of pH and temperature on enzyme activity.

- Investigating the biochemistry of DNA damage and repair mechanisms.

- Studying the role of specific proteins in cellular signaling pathways.

- Analyzing the biochemical properties of lipids and their role in cellular processes.

- Investigating the biochemistry of protein synthesis and post-translational modifications.

- Studying the effects of nutritional factors on gene expression and metabolism.

- Analyzing the biochemistry of neurotransmitters and their role in neuronal communication.

Hot Biochemistry Topics

Explore the trending and emerging topics in biochemistry that are shaping the future of the field. Select one of our hot biochemistry topics and start writing your paper in minutes:

- Precision medicine: Personalized treatments based on biochemical profiles

- Immunotherapy: Harnessing the immune system to combat diseases

- Epigenetics: Exploring the impact of gene expression regulation on health

- Metabolomics: Uncovering the metabolic signatures associated with various conditions

- Single-cell analysis: Examining the biochemistry of individual cells

- Proteomics: Studying the complete set of proteins in a cell or organism

- Bioinformatics: Integrating computational methods to analyze complex biological data

- Synthetic biology: Designing novel biological systems with engineered functions

- Drug discovery and development: Exploring innovative approaches

- Structural biology: Investigating the three-dimensional structures of biomolecules

- Cancer metabolism: Understanding the metabolic alterations in cancer cells

- Bioengineered organs: Advancements in creating functional and transplantable organs

- Metagenomics: Exploring the genetic potential and functional diversity of microbial communities

Popular Ideas For A Biochemistry Paper

Stand out among your peers with these popular and widely-discussed popular ideas for a biochemistry paper that offer ample research material for a compelling essay:

- Antioxidants and oxidative stress-related diseases

- Drug resistance in cancer cells: Biochemical mechanisms

- Nutrition, gene expression, and metabolic health

- Biochemistry of neurodegenerative disorders and therapies

- Protein structure’s role in drug design and development

- Biochemistry of aging and anti-aging strategies

- Biochemical pathways and cellular apoptosis in diseases

- The link between biochemistry and mental health

- DNA repair mechanisms and genomic stability

- Biochemistry of microbial biodegradation for environmental cleanup

- Plant defense mechanisms against pathogens: Biochemical insights

- Environmental toxins and human health: Biochemical perspectives

- Biochemical approaches to combat antibiotic resistance

Current Biochemistry Research Topics

Stay current and informed with our current biochemistry research topics. They reflect the latest breakthroughs and ongoing research in the dynamic field of biochemistry:

- Single-cell omics: Unraveling cellular heterogeneity at the molecular level.

- RNA modifications: Investigating their role in gene expression regulation.

- Metabolic reprogramming in cancer: Understanding the therapeutic implications.

- Protein engineering and design: Creating novel biomolecules with enhanced functions.

- Artificial intelligence in biochemistry: Utilizing machine learning for prediction.

- Structural biology: Unveiling the 3D structures of complex biomolecules for drug discovery.

- Biochemical profiling of the human microbiome and its impact on health and disease.

- Nanomedicine: Designing and optimizing nanoscale drug delivery systems for targeted therapies.

- Immunometabolism: Studying the intricate relationship between metabolism and immune response.

- Epitranscriptomics: Investigating the role of RNA modifications in cellular processes.

- Metabolomics-driven precision medicine: Applying metabolic profiling for personalized treatments.

- Biochemical mechanisms of aging: Exploring molecular pathways and interventions for healthy aging.

- Exploring the biochemistry of plant-based biofuels for sustainable energy production.

Get Help With Your Biochemistry Paper

When it comes to academic writing assistance, our company is your top choice. Our team of experienced writers specializes in a wide range of disciplines, including providing services like “do my dissertation” and “ master thesis help ” writing. As a leading thesis writing service, we take pride in delivering interesting and well-researched papers of the highest quality.

Our dedicated writers are committed to meeting your specific requirements and deadlines, ensuring fast and efficient service. We understand the unique needs of students in college and strive to provide custom solutions that cater to every class and assignment. With our online platform, you can easily access our services from anywhere, making academic support convenient and accessible.

Trust our best in class writers to deliver high quality, well researched papers tailored to your academic needs. Get in touch with our experts today and take advantage of our latest offers and dsicounts!

How do I choose a topic for my biochemistry paper?

Start by exploring current research trends, identifying areas of interest, and brainstorming potential topics. Consult with your instructor or supervisor to ensure your chosen topic aligns with the scope of your assignment.

How can I ensure the accuracy and reliability of my research in a biochemistry paper?

To maintain high-quality standards, conduct thorough literature reviews, use reputable sources, perform rigorous experiments or analyses, and ensure proper controls are in place. Consult with experts or your supervisor for guidance if needed.

How do I balance technical details and clarity in my biochemistry paper?

Aim to present technical information in a concise and understandable manner. Define any specialized terms, provide necessary background information, and use illustrative examples to make complex concepts more accessible to your readers.

How can I make my biochemistry paper more engaging and readable?

Use clear and concise language, provide relevant examples or case studies, incorporate visuals like figures or tables to illustrate data, and consider using subheadings to enhance the organization and flow of your paper.

Make PhD experience your own

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- How It Works

- PhD thesis writing

- Master thesis writing

- Bachelor thesis writing

- Dissertation writing service

- Dissertation abstract writing

- Thesis proposal writing

- Thesis editing service

- Thesis proofreading service

- Thesis formatting service

- Coursework writing service

- Research paper writing service

- Architecture thesis writing

- Computer science thesis writing

- Engineering thesis writing

- History thesis writing

- MBA thesis writing

- Nursing dissertation writing

- Psychology dissertation writing

- Sociology thesis writing

- Statistics dissertation writing

- Buy dissertation online

- Write my dissertation

- Cheap thesis

- Cheap dissertation

- Custom dissertation

- Dissertation help

- Pay for thesis

- Pay for dissertation

- Senior thesis

- Write my thesis

210 Biochemistry Research Topics For Your Class

Biochemistry research topics demand practical experiments with samples and specimens that yield the desired results. Before approval, a title in this field must start with a proposal representing the typology that the study will eventually produce. Project coordinators or supervisors must screen the topics that students choose without exceptions. Therefore, topic ideas must arise from careful cross-examination of sample specimens and experiments that researchers have watched for some time.

What is Biochemistry?

As the name suggests, biochemistry is the fusion of chemistry and biology in living organisms. Nobody can overstate the essence of biochemistry because it explains the causes of illnesses in animals and humans. Also, biochemistry continues to help researchers and scientists determine how molecules like proteins and vitamins function within the body.

Writing excellent papers in the fields of biochemistry requires admirable knowledge and a good understanding of this scientific branch. Luckily, the internet has many resources with materials that students can research their topics. But students should select their topics carefully and structure their papers properly to impress educators to award them top grades.

Biochemistry Paper Outline

A good biochemistry paper comprises several sections that enable the audience to understand the topic and its information. Here’s is an outline of a quality biochemistry paper.

Title page : The title page comes first in a research paper, providing an overview of the study. This page should include the running head, paper title, student’s name and affiliations, and page number. Students should format this page depending on their writing style, whether MLA, APA, or Chicago. Intro : The introduction is the second section of a biochemistry research paper. And this part should have an abstract and an introduction. Nevertheless, this part places the work into context for the audience. It also tells the readers why the study is relevant. Literature review : In this section, the student examines the materials they consulted during research. A good paper comprises a comprehensive assessment to show that the author read several published works on the issue. It also shows why the current study is essential and different. Methodology : Here, the writer explains their methods to gather and analyze the information they convey to the audience. This section is essential because it enables the audience to evaluate the validity of the research. Researchers can use experiments, observation, case studies, and documentary methods in their research. Analysis and discussion : In this section, the writer conveys the results of their research work. They also expound on their methodology. This part can include tables and figures that are easy-to-understand and precise. Conclusion : This part of a biochemistry paper summarizes the research while suggesting further studies on the topic. Reference : This section lists the materials that the writer consulted during the research. Including a bibliography makes the work authentic.

College and university learners must pick interesting topics to enjoy working on their research projects. Without exciting topic ideas, learners can struggle to work on their papers from the beginning to the end. That’s why this article lists some of the best and popular topics in this scientific field. However, you should remember there is always a possibility to custom dissertation from our professional helpers team.

Remarkable Biochemistry Research Paper Topics

Maybe you’re looking for a topic that will leave the educator no option but to award you the best grade in your class. If so, consider the following ideas for your research paper.

- Can watermelon help in the fight against viral activities?

- Explain how ethanol causes corrosion

- How scientists extract the medicinal components of a plant

- Taxonomic groupings’ role in biochemistry

- Investigating the fungal pathogens that science associates with tomato spoilage

- The impact of Cadmium on humans and the environment

- The optimum conditions for ethanol and aqueous extracts

- How drinking water fluorides affect your teeth

- How acid rain impacts building structures

- The methanol leaf extraction process

- How high-fat diets cause heart diseases and obesity

- The analytical biochemistry concepts

- Applied biochemistry and biotechnology- What’s the correlation?

- How to use pawpaw leaves to produce deodorants

- The active polar gels spontaneous flow and the causes

- Analyzing gene encoding in cassava and sorghum

- Destabilization’s causes in lysosomes

- Evaluating physicochemical processes in living organisms

- Investigating conditions that facilitate Thymus Vulgaris’ antibacterial activity

These are great topics that will impress your professor to award you a good grade. Nevertheless, prepare yourself to research any of these ideas extensively before writing.

Interesting Biochemistry Topics

When choosing a topic in this field, a vital consideration is ensuring that it’s exciting to hold the reader’s attention. Also, the learner should pick a topic they are interested in to write a winning piece. Here are exciting ideas to consider in biochemistry.

- Comprehensive analysis of infectious diseases’ evolutionary biology

- Photosynthesis and its functions

- Reviewing plant disease management using modern technology

- How oxytocin affects psychopathic disease treatment

- Analyzing the factors causing genetic mutation

- How addictive substances affect the human genes

- Living organisms and their cell structures

- The development of cellular technology

- Gestation period and its function in mammals

- Cellular biology functions in recognizing and identifying genetics

- Studying chemical reactions in the body using hormones

- Alzheimer’s disease and therapeutic advances in treating it

- The regulation mechanisms of stem cell biology

- Cancerous cells and their biology

- Genetic mapping and linkage analysis

- The nucleic acid structure

- Coronavirus and epidemiology

- Cellular membranes’ functions and their essence in life forms

- Analyzing the capabilities of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells

- Studying the apoptosis significance in faulty cells’ growth

- Understanding the role of microbial itaconic acid and the production of fungi synthesis

- Analyzing MOBs and NDR1/2 relationship in signaling a defective cell cycle

- Documenting and mapping morphogen signaling pathways and regulation of biological responses

- Vaccines and diseases- Understanding B cell receptors targeting

- Bacteriophages and human health

- Microbial biofilm formation- Molecular mechanisms therapeutics

- Comparing protein folding and design between humans and mice

- Investigating the evolution of microbial diseases

- The role of structural determinants of protein in human health

- Analyzing ion transport and membrane biology in innate immune response

- How protein-membrane structure and function affect drug distribution

- Why is protein-membrane design so important?

- Cellular basis and mapping biochemical glucose transport of the insulin action and resistance

- Comprehending the role of peptide and protein structure in membranes

- The essence of platelet function and dysfunction on injuries

- Understanding Sprouty 2 inhibition impacts on periodontal ligament cells

- How placental toxic factors’ release affects blood circulation

- Determining the protein amount in urine

- How maternal serum affects pregnant women

- Evaluating diabetes’ pathogenesis and its impact

- What necessitates iron homeostasis regulation?

- The relationship between high hepcidin level and T2DM

- How biochemistry experiments have facilitated cardiovascular illnesses treatment

- Factors necessitating insulin resistance in the body

- Ways to identify mycobacterium Ulcerans on the skin

- Environmental reservoirs of biological catalysts and enzymes

- The risks of biochemistry lab research

- Ecological conditions’ impact on lab extracts

- Evaluating alkaloidal isolates in plants

- Analyzing anti-inflammatory medical plants in tropical regions

- Investigating pro-inflammatory eicosanoids’ production

- Anti-inflammatory medicinal plants- Understanding their therapeutic action

- How herbal preparations affect skin disease treatment

- Destabilizing the Lysozyme activity

- How temperature ranges affect enzyme activity

- Alpha crystalline role in a concentration

These are exciting topics to consider for a biochemistry paper. However, they require an extensive investigation to draft a winning essay.

Current Topics in Biochemical Research

Maybe you want to write about something latest. In that case, consider these current topic ideas.

- Investigating the role of peptide and protein function in membranes

- Analyzing the biological impact of periodontal ligament cells

- Critical analysis of microbial diseases’ evolution

- Understand the regulatory mechanisms in genetics

- B cells receptors role in vaccines and diseases

- The biology and pathology of cancer

- What regulates the population of cells?

- Factors that scientists associate with new drug initiation to a patient

- Phenolic acids and their vitro effects

- Evaluating the effects of maternal serum on women during pregnancy and children

- Alkaloidal isolates effects of plants

- Chemical composition effects of potassium permanganate

- Preliminary investigation on Citrus Sinensis Seed and Coat screening

- Metalloenzymes and metalloproteins- The contrast

- Aspirin chemical quantity analysis

- Exploring Polyphosphate role on Erwinia Caratovora Virulence

- Reviewing the human genome mapping and its impact on disease prevention

- Why information matters in predicting the protein dihedral angles

- Central dogma exceptions

- Investigating the functions and structure of amino acids

- Why protein Kinase matters in cancer and drug resistance

- Malignancies biology and skeletal complications

- Studying cellular structure and function

- Biology and cancer pathology

- Biology and coagulation disease

- Understanding physical biochemistry

- Intestinal microbes- What is their role in human health and diseases

- Developing and characterizing chemical compounds targeting colon, pancreatic, and lung cancers

- Using microarray technology in describing P623 and P73 regulated genes in cancer

- The genetics of cancer molecules: Understanding the genomics-based method for gene expression and association studies

- Lipid metabolism in mitochondrial and metabolic diseases

- Genetic regulatory and epigenetic mechanisms

- Functional nucleic acid and protein interactions

- Structural biology and enzymology

- Understanding measles in infants and biochemistry-based vaccination

- Biochemistry’s role in controlling cell motility in different developmental stages

- Why scanning serum medical examinations and microscopy matter in biochemistry

- How various brain cancers relate to genetics and radiation exposure

- How to preserve plant extracts for biochemistry experiments

- Biochemical-based rotavirus vaccines’ role in acute gastroenteritis in children

- Explain trial stages vaccine reactions and the role of biochemistry in achieving the desired results

- How amino acids hydrocarbons affect biochemical reactions after subjecting the human body to medication

- The essence of biochemistry research in developing ways to initiate new treatments in patients

- Understanding the chemical properties of the COVID-19 vaccines and reactions in males and females

Biochemistry research projects on these topics can help learners unearth the latest information in their study field. What’s more, students can use them to showcase their awareness and impress educators.

Cool Biochemistry Topics

Selecting a topic that you’re comfortable working with will simplify your project completion. Here are excellent biochemistry paper topics to consider for comfortable research and writing experience.

- Immunoglobulin G Receptors and their role in a clinical malaria study

- The effects and process of destabilizing Lysozyme activity

- The flow of chemical energy through metabolism

- Phosphates structure as the necessary synthesis from alcohol

- Bacteria membranes and their dynamics

- DNA synthesis complexities in the definition

- Assessing the chemical quality in Aspirin production

- A comprehensive investigation of hepatitis B prevalence

- A review of Amyloid diseases