Identity Art – Expressing Personal Authenticity Through Creativity

For centuries, creatives have used art as a tool for self-historicization and self-discovery that sheds light on the subjective experiences of individuals from diverse backgrounds in a way that communicates universal or specific cultural shared experiences. Seeking one’s true identity or finding a methodology to unpack one’s complete identity requires the artist to self-reflect, research, and create knowledge and versions of themselves through art that might seem self-serving at first, but inherently provides insight into the vast identities and human experiences shaped by the societies that we live in. In this article, we will delve into the history and definition of identity art, and even look at a few examples of identity artists who explore related themes in their professional practice. Keep reading to discover the different ways that identity has been explored in art!

Table of Contents

- 1.1 Defining Identity Art

- 1.2 Identity Politics in Art

- 2.1 Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) by Frida Kahlo

- 2.2 Dinner Party (1974 – 1979) by Judy Chicago

- 2.3 Self-Portrait (1977) by Samuel Fosso

- 2.4 Unveiling (Women of Allah series) (1993) by Shirin Neshat

- 2.5 One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana (1998 – 2002) by Deborah Luster

- 2.6 Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps (2005) by Kehinde Wiley

- 3.1 What Is Identity Art?

- 3.2 Which Three Famous Artists Address Identity Politics in Art?

- 3.3 Why Is Identity Art Significant?

Exploring Identity Through Art Practice

You must have come across an artist who uses themes of identity or identity politics in art. After all, how can one produce an artwork that does not reflect an aspect of one’s identity in any way, shape, or form? Art is a powerful tool that can be used to provide new perspectives about the human condition, with themes like identity and self-discovery being part of the human experience, which is prevalent in art history. Identity has been a consistent topic of interest for creatives since life often presents us with twists and turns that beg for us to self-reflect on the histories that influence, shape, and change us.

Defining Identity Art

Identity refers to who you are and sometimes encompasses an exploration of uncovering what aspects of the past have shaped your present state of existence. The beautiful part about identity is that it can be melded, broken apart, transformed, and exists as a continuous arrangement of internal and external stimuli that is always in a state of flux, and even resistance. While we cannot place a complete definition on identity, it boils down to who we think we are in the world and what informs our perception of such a conception.

In many ways, identity art is a creative form of actively philosophizing ourselves in the present, to record the versions of ourselves that emerge from the influences and desires of others and us.

Societally, identity is defined by perhaps the name and nationality on our identity or social security cards. Identity is often tied to a broadly recognized physical document and a form of proof or evidence of our existence that seeks validation from the world. Identity is often connected to what we can see, touch, and feel that communicates the unique or relatable parts of ourselves to each other. Fundamentally, identity is also tied to our species as humans, who seek additional forms of individuality for affirmation that our existence matters, such that we can be “identified”.

Identity Politics in Art

In art, the term “identity politics” appeared most prominently in the 1970s and 1980s American art scene and referred to art that addressed topics related to identity and what identity is societally understood as. These included topics of gender, race, and sexuality, which are all crucial aspects of each person’s individuality and identity. However, the term itself was also criticized for being essentialist toward the artist and was seen as a reductive term that tokenized artists as falling under one particular “identity”. An important discussion within the discourse of identity art is its complexity as a social construct and something that has been historically linked to artworks that reflect the experience of hetero-normative, white male gaze-centered expectations within the art world.

Another key development in identity art is the decolonization of how artworks produced by historically marginalized groups of artists are treated across galleries and museum spaces, and the importance attributed to identity art. Identity politics in this context refers to a means of cultural production that mirrors and pre-figures crucial conversation in art spaces. The term “identity politics” has been traced back to the 20 th century and describes the politics that revolve around identity, encompassing race, social background, religion, nationality, and other social phenomena that shape identity such as migration, nationalist agendas, or the exclusion of a group of people for example. A few prominent figures who discussed identity politics include the renowned Afro-Caribbean philosopher Franz Fanon and the British writer Mary Wollstonecraft.

Identity in art can thus encompass critical reflections on systems of oppression from the past and the current era, which largely impacts the development of identities, collective or individual, of a particular group of people or culture.

Examples of Identity in Art: Famous Identity Artists

One can easily find many examples of artists and writers incorporating identity and identity politics into their practice, whether the subjects revolve around historical exclusion, occupation, colonialism, the slave trade, or the impact of war. This can also include artists who hail from backgrounds where their culture has been exploited or disproportionately affected due to political actions by governments and disputes over geographic location. This brings us to the well-known statement that “the personal is political” to suggest that the identities of artists mirror the circumstances of their existence and offer insight into the broader socio-political state of the cumulative factors that shape their identity and worldview. Below, we will introduce you to a few identity artists who have shaped the genre of identity art by drawing attention to various important issues.

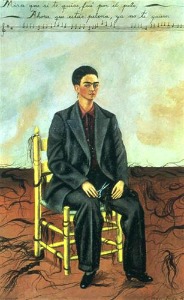

Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) by Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo is an artist who you might remember by her colorful and symbolic self-portraits that explore not only her identity through her experiences with pain, love, and Mexican culture but also her physical body and appearance. Kahlo’s paintings such as Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair feature the artist dressed in an oversized suit with a short hairstyle and pieces of her hair scattered all around the floor. The most striking part about the work is her outward gaze which penetrates the viewer’s own eyes and is as sharp as the scissors in her lap.

Kahlo alters her appearance to take on a more traditionally and societally masculine appearance, which is believed to be a reference to her alter ego, possible bisexuality, or perhaps a personal statement on beauty ideals.

The text at the top of the composition was taken from a Mexican song and states “Look, if I loved you, it was because of your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don’t love you anymore”. Kahlo’s representation of herself is a symbol of her autonomy that followed her divorce from Diego Rivera in 1939. Kahlo’s confrontation with the viewer is a reminder of the violence of separation on an emotional level that has the power to transform one’s physical identity and sense of self. Her personal liberation speaks of strength in the face of pain and even isolation since Kahlo once stated that she painted self-portraits due to her being alone quite often.

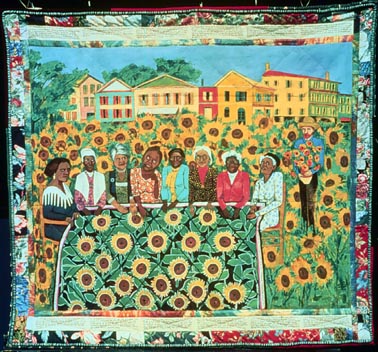

Dinner Party (1974 – 1979) by Judy Chicago

Seating 39 individuals, this famous installation by feminist artist Judy Chicago is a classic example of identity art that attempted to revise art history in terms of its representation of women in art, specifically representing some of the world’s most important women. This is one such example where identity, which is tied to gender, has been linked to the success and recognition of women in the art world. While Chicago’s work is recognized as Feminist art , her installation is also regarded as a form of identity art that engages with the politics of representation and exclusion of women.

The Dinner Party set up is also reminiscent of Da Vinci’s Last Supper , which is biblically and largely patriarchal, however, her installation honors the contributions of 999 women, whose names are inscribed on the floor of the installation, on 2,304 triangular tiles.

The installation took Chicago and her team of artists and volunteers around five years to complete and was first displayed in 1979. Today, the piece can be viewed at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in New York’s Brooklyn Museum. Chicago uses her art practice through the mediums of installation, embroidery, and ceramic art to explore women’s history. In the early 1970s, Chicago explored abstract iconographies to unpack her experiences as a woman, which led to her becoming a leading figure in the feminist movement.

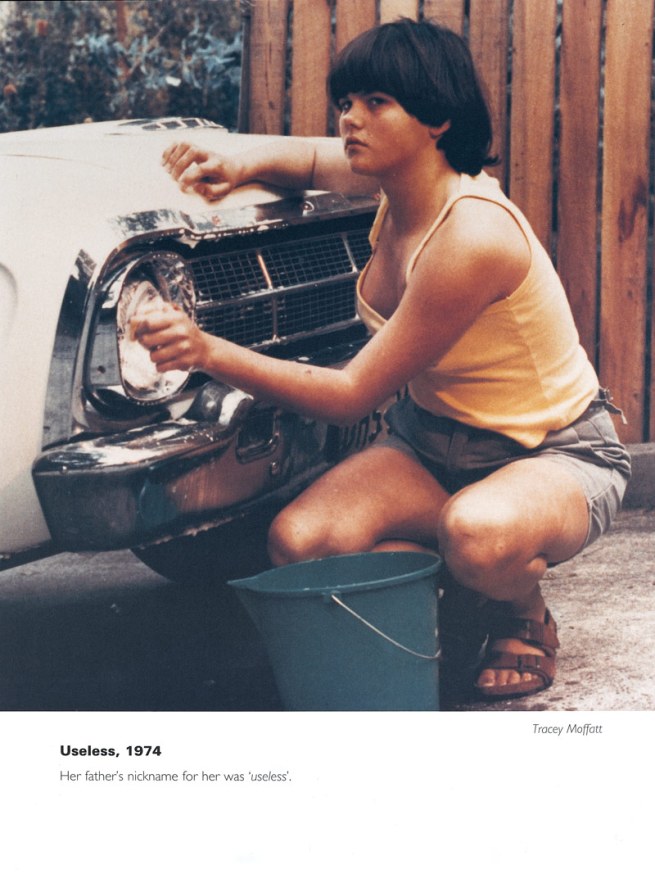

Self-Portrait (1977) by Samuel Fosso

Renowned Cameroonian photographer Samuel Fosso approaches the topic of identity in his photography practice through self-portraiture, as he dons different personas and looks. After fleeing from the hardships inflicted on his people during the Biafran War in 1967, Fosso became a refugee in Bangui at the age of 13, where he managed to open his own photography studio. His first experiments with photography were self-portraiture since he sent photos of himself to his grandmother in Nigeria. Fosso’s self-portraits imitated aspects of West African pop culture, from music to fashion as the young artist adopted multiple looks and characters in his project. His work also tackles self-representation, sexuality, and gender as one also spots his studio lights and performative elements in his 1977 Self-portrait , which is housed at the International Center of Photography in New York.

Fosso’s experimentation with different personas draws attention to the playful and perhaps performative ways that one can go about exploring one’s identity.

As an art practice, this adoption of culture reflects the popular tropes in fashion and music that play huge roles in shaping the identities of many people. The act of photographing and documenting these characters also speaks to the immortalization of identity, reminiscent of traditional portraiture, and the function of portraiture in helping people recognize themselves and others. Images thus communicate personal and perceived identities. Other famous artists who created identity artworks around the same time as Fosso include Cindy Sherman, Rosa Rolanda, George Passmore, and Gilbert Prousch among many more famous artists who work with identity as their medium.

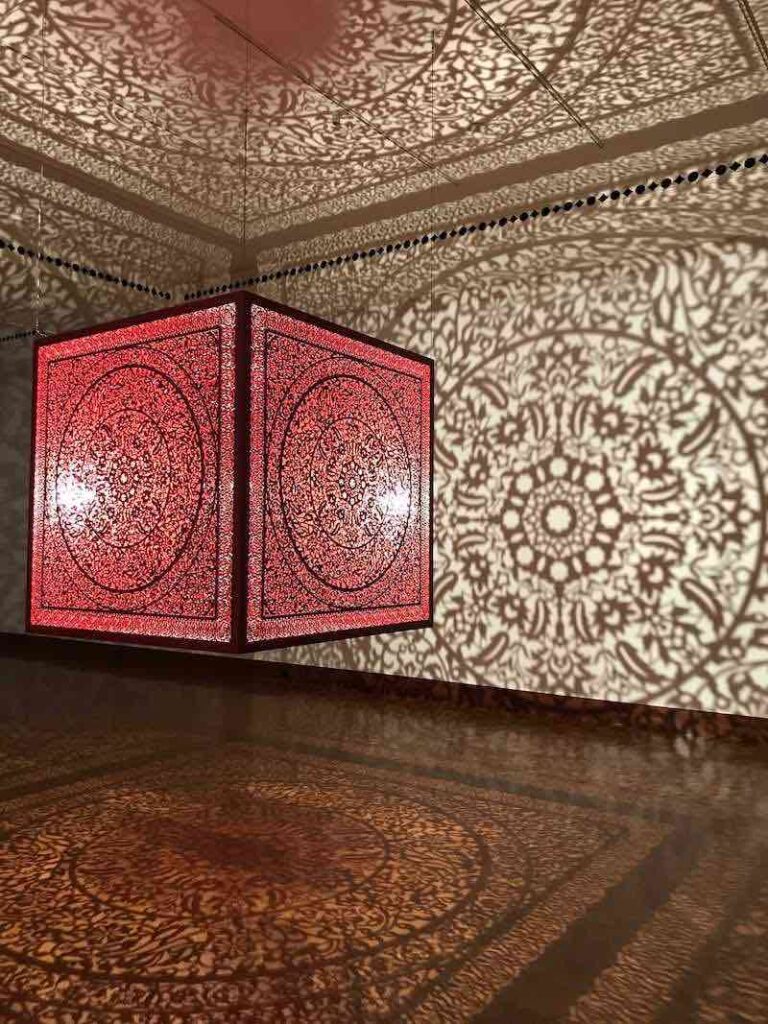

Unveiling (Women of Allah series) (1993) by Shirin Neshat

Touching on subjects such as femininity drawing from her own experience and the shared experiences of Islamic women in Iran, Shirin Neshat is among the most famous contemporary artists whose use of photography captures the identity politics of women in connection to Islamic fundamentalism and Iranian militancy. Her work Unveiling was part of her series titled Women of Allah , which explores the complex politics of Islamic women through sculpture, photography, and film.

Her works also use texts by Furugh Farrukzad, whose expression of female sensuality is known to be the most “radical”.

In a society where most Islamic women face stereotypically informed experiences from the Western gaze, Neshat exposes the critical notion of the veil that poses new questions about the identities of Islamic women, caught between politics and the culture of Islamic tradition that is often stereotyped as repressed. Neshat’s exploration of identity thus speaks to a wide audience of cultural and traditional belonging that shares such experiences of trying to navigate identity and femininity within Islamic culture, religion, and geographic law. While not all countries follow set laws for women to wear their veils and adhere to Islamic customs, many other countries face similar complex questions around the choices that women have to express their femininity and understanding that women in certain societies do maintain their choice to express their femininity in different ways, through the veil and the body.

One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana (1998 – 2002) by Deborah Luster

One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana is a powerful identity artwork featuring the portraits of inmates from several prisons across Louisiana, as well as images of those in the maximum-security penitentiary at Angola. How is this exploration of identity significant? Created by Deborah Luster in 1998, the project was born from the artist’s experience with losing her mother after she was murdered and the case remained unsolved. As a result, the artist threw herself into examining the impact of crime and violence on society and families, which speaks to larger societal issues across the world since violence manifests in different forms. Luster started her portrait project in Louisiana and Angola, where many people were serving a life sentence.

Luster captured the portraits of those who were faced with little to no choice of being imprisoned in a dehumanizing environment and system, such that their images were the only tokens of personalization.

Many inmates lined up to get their picture taken and some even performed for the artist. Luster photographed 249 inmates and printed the images on aluminum plates to evoke the visuals of the 19 th -century tintype images. Luster’s installation included a black metal cabinet, which functioned as a space for her archive. This archive is now symbolic of the lives that get put on hold within the systems that intend to punish violence and quietly reminds one of the homely items such as the cabinet, which acknowledges the families who are left behind due to crime. Luster’s identity art stems from a very brutal, personal, and psychologically tense place, which makes her project one that must have seemed almost daunting to someone who lost a mother to a violent crime. One can quickly identify the significance of artists partaking in sharing their personal histories since many of the influences that shape our lives can also resonate with the identity politics of others.

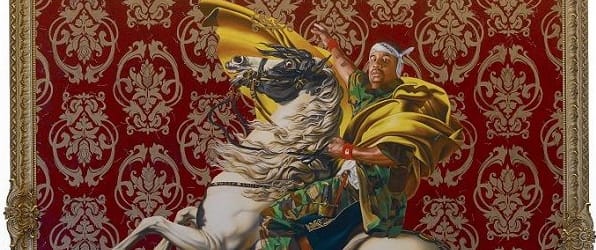

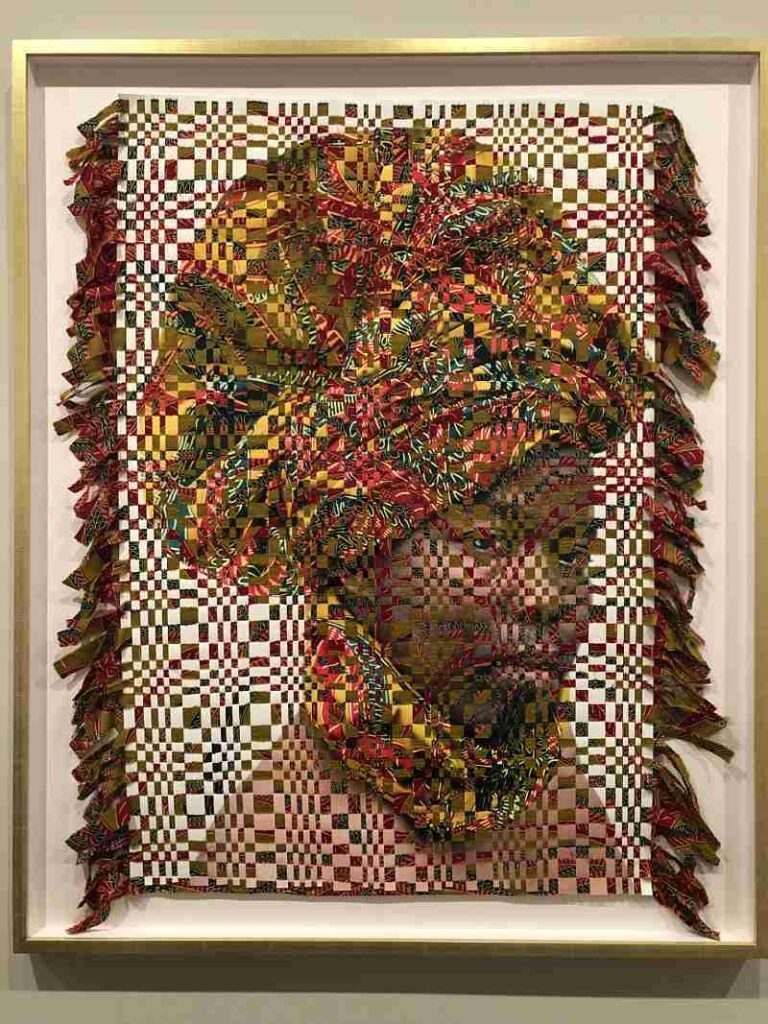

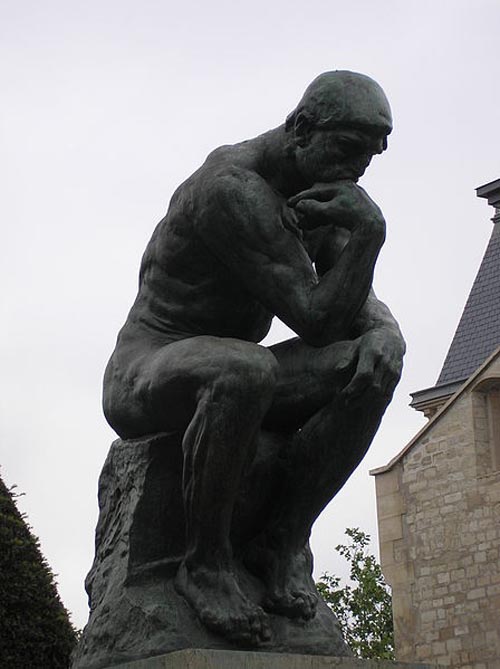

Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps (2005) by Kehinde Wiley

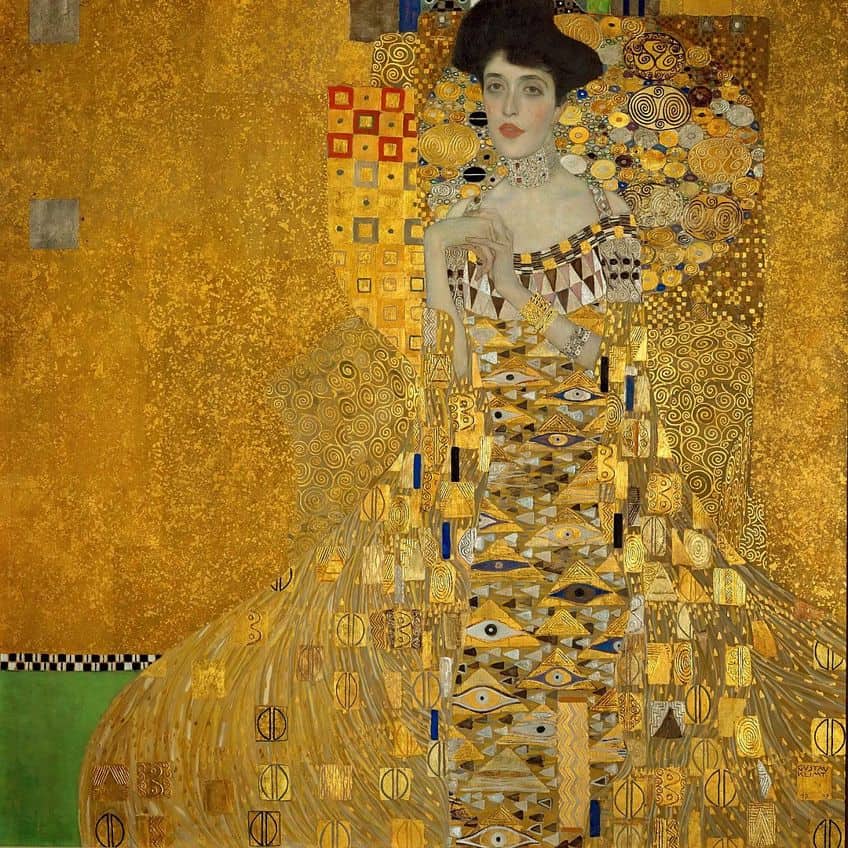

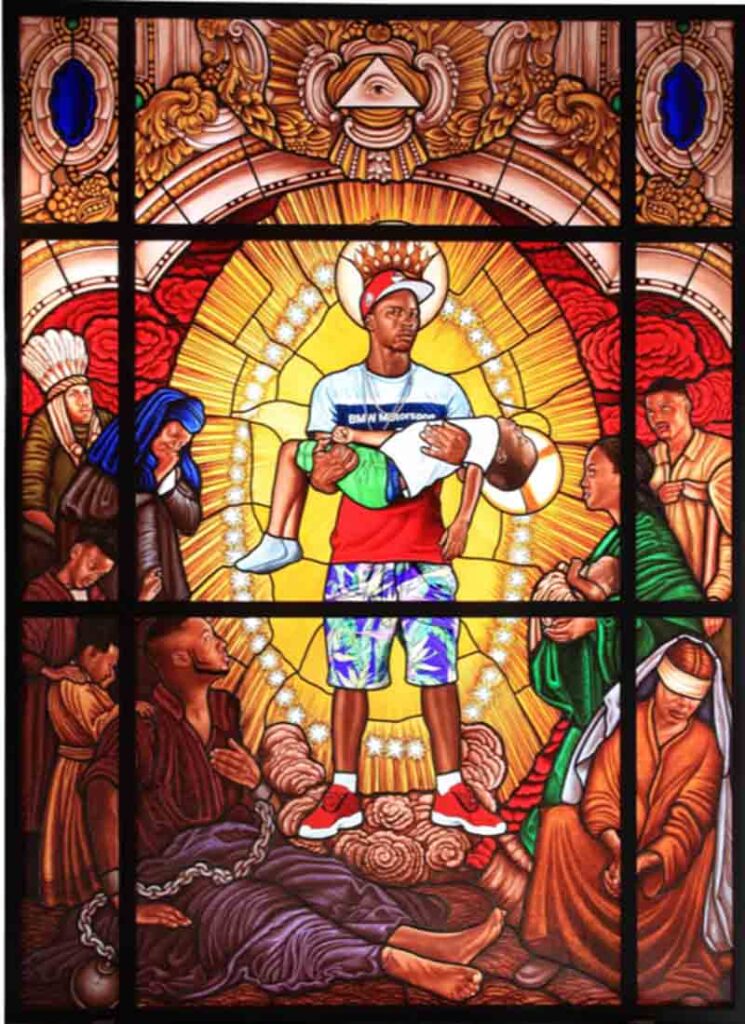

American contemporary painter Kehinde Wiley is among the most famous artists of our time working with identity through references to traditional paintings and art history. Wiley plays with the heroic rhetoric often depicted in art history through the lens of the white Western gaze, however, his paintings insert people of color in such portraits to provide a re-oriented version of history that sparks conversations on the lack of representation of Black people in art history and its impact on Black identities. In 2018, the artist became the first African-American artist to paint an official presidential portrait in the United States. The portrait depicted former president Barack Obama and was created for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Wiley then established the Black Rock Senegal artist-in-residence program, which engaged with global artists and invited them to produce works in Dakar, Senegal. Wiley’s works are collected by many and are housed in over 50 museums across the world.

In identity artworks like Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps , Wiley asks viewers to confront the art history canon and understand our role in enabling and disabling previous systems of exclusion and underrepresentation.

Through appropriation, Wiley strategically inserts key differences across the historical portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte and replaces his image with the figure of an African-American man whom he approached on the street while finding a model. The painting is also a subversion of the original 1801 painting by Jacques-Louis David , which was originally commissioned by King Charles IV of Spain to commemorate the victory against the Austrians. A few symbolic details one might spot in Wiley’s painting are the gold-encased sword and the royal blue coat, paired with modern attire such as Timberland work boots and the bandana, which is a reference to militarism. Through tiny details in the background such as the mini paintings of sperm, Wiley also draws attention to the very gendered traditions of portraiture in the West and its promotion of hypermasculinity. This also brings up critical questions about the impact of Western art history and its preferences, which ultimately shaped and influenced the identities of many non-Western nations.

Numerous artists across the globe are working with multiple aspects of identity, human nature, and identity politics in innovative and conceptually profound ways. From culture to race and larger societal systems of oppression, war, and personal struggles, artists always manage to capture the complexities of identity. It is also important to celebrate identity and simultaneously recognize the structures that impact the evolution of ourselves, whether that be politically, socially, or behaviorally.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is identity art.

It is crucial to understand that since identity is not fixed to a particular style or look, the definition of identity art is therefore not set to a specific set of characteristics. However, identity art prioritizes the artist’s own self-exploration through a variety of themes and topics about the human condition, race, sexuality, gender, and identity politics. These can expand into critical themes revolving around world history and the historic displacement of various cultures and groups of people. Identity art emerges from the subjective experience and can offer insight into the artist’s heritage, worldview, and social identity.

Which Three Famous Artists Address Identity Politics in Art?

Among the numerous famous artists who create identity artworks, the three most famous figures include Adrian Piper (1948 – Present), Coco Fusco (1960 – Present), and Kehinde Wiley (1970 – Present).

Why Is Identity Art Significant?

There are many reasons as to why identity art is important. It offers viewers insight into the personal histories of artists and the factors in their lived realities that influence the development of identity. A major feature of identity art is identity politics since it promotes reflection on the systemic and historical imbalances of the past in terms of representing disadvantaged and marginalized groups of people. Identity art is complex and unique to each artist’s experience, however, when engaged in broader socio-political issues, it can resonate with a wider audience. Themes such as nationality, race, sexuality, gender, political views, living habits, fashion, heritage, and stereotypes all contribute to identity art.

Jordan Anthony is a film photographer, curator, and arts writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. Anthony schooled in Durban and graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts. During her studies, she explored additional electives in archaeology and psychology, while focusing on themes such as healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. She has since worked and collaborated with various professionals in the local art industry, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban (with Strauss & Co.), Turbine Art Fair (via overheard in the gallery), and the Wits Art Museum.

Anthony’s interests include subjects and themes related to philosophy, memory, and esotericism. Her personal photography archive traces her exploration of film through abstract manipulations of color, portraiture, candid photography, and urban landscapes. Her favorite art movements include Surrealism and Fluxus, as well as art produced by ancient civilizations. Anthony’s earliest encounters with art began in childhood with a book on Salvador Dalí and imagery from old recipe books, medical books, and religious literature. She also enjoys the allure of found objects, brown noise, and constellations.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Identity Art – Expressing Personal Authenticity Through Creativity.” Art in Context. January 9, 2024. URL: https://artincontext.org/identity-art/

Anthony, J. (2024, 9 January). Identity Art – Expressing Personal Authenticity Through Creativity. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/identity-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Identity Art – Expressing Personal Authenticity Through Creativity.” Art in Context , January 9, 2024. https://artincontext.org/identity-art/ .

Similar Posts

Classical Art – Understanding this Highly Influential Style

Lithography – Understanding the Art of Lithography Printmaking

Baroque Art – Exploring the Exuberance of Baroque Period Art

Vietnamese Art – Traditional Vietnamese Art Styles

Pre-Columbian Art – The History of Pre-Columbian Artifacts

Aboriginal Art – Preserving Indigenous Australian Culture in Art

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

Identity Art & Identity Politics

Summary of Identity Art & Identity Politics

The twentieth and twenty-first centuries have seen many artists use art as a way to present their authentic life experiences, interrogate social perception of their identity, and critique systemic issues that marginalize them in society. These include women artists, artists of color, LGBTQ+ artists, disabled artists, and indigenous artists. Their art as well as activism have transformed the curatorial practices of the art world and made a profound contribution to the social and political spheres related to the rights of minority groups. While the term "identity politics" gained traction in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s to designate art that deals with issues of identity (especially race, gender, and sexuality), it has fallen out of favor since then, with many critics asserting that it has had a reductive effect, turning artists into tokenized representatives of one particular identity and further contributing to a view of identity as innate and fixed rather than socially constructed. Aware of this potential pitfall, many contemporary artists working with identity issues have instead worked to highlight the complexity of identity as an evolving lens of social analysis.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- There is no one type or style of Identity Art, but the term can be a useful umbrella for understanding artistic practices that prioritize questions of artists' identities and the art world's reception of their works. Many artists have argued that the default expectations of the art market and curatorial establishment are rooted in white, male, and hetero-normative experience. Identity Art can be seen as an attempt to redress this imbalance, and to encourage reflection on operations of art history that have systematically disadvantaged those whose artworks did not conform to these expectations or address similar concerns.

- Despite an often poorly-framed debate around its importance, art engaging with identity has led to greater awareness and major changes in the way museums, galleries, and critics treat work by historically marginalized groups. Decolonization initiatives, diversity programs, and critically reflexive curation are all legacies of Identity Art and Identity Politics.

- A risk for artists engaged in Identity Art is the potential to have their work read only in relation to one issue or social struggle, so many artists today deal with issues of identity through the lens of "intersectionality," which views different facets of identity (such as race, sexuality, age, etc.) as intertwined. Relatedly, the concept of "performativity" (the theory of identity as fluid yet enforced by social conditioning) complements this view.

- Identity Politics is a concept which has far-reaching implications in both the art world and other mediums of cultural production. In the 21st century debates around its influence on the production of film, television, and video games have been robust, and in many cases mirror or pre-figure critical and curatorial controversies in museums, galleries, and the art market.

Key Artists

Overview of Identity Art & Identity Politics

African-American artist Kehinde Wiley stages encounters between the white past of art history with his present by inserting a black subject into his re-creations of Western masterpieces. The insertion invites reflection on history, exclusion, and marginalization of non-white peoples. The models for his paintings are usually everyday people he asked to pose for him; he calls it his "street-casting process." Here the neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David 's painting of a triumphant Napoleon ( Napoleon Crossing the Alps , oil on canvas, 1803) gets a remake with a black man taking place of the Emperor, his camouflage gear, Timberland boots, and bandana wrapped around his head bringing the work to the contemporary.

Artworks and Artists of Identity Art & Identity Politics

Dinner Party

Artist: Judy Chicago

This installation is comprised of a large triangular ceremonial banquet table set with 39 place settings, each of which commemorates a significant woman from history. Each of the three sides (or "wings") of the triangle represent a different period from history. Wing I includes women from Prehistory to the Roman Empire, such as Primordial Goddess, Fertile Goddess, Ishtar, Kali. Wing II includes women from the beginnings of Christianity to the Reformation (for example, Marcella, Saint Bridget, Theodora), and Wing III includes women from the American Revolution to more contemporary feminist thinkers, including Anne Hutchinson, Sacajawea, Caroline Herschel, Mary Wollstonecraft, Sojourner Truth, among others). Each place setting features elaborately embroidered runners, featuring a variety of needlework styles and techniques, gold chalices and flatware, napkin with gold edges, and hand-painted china porcelain plates that contain raised vulva and butterfly forms (each of which was created in a style that represents the individual woman the place setting was made for). Chicago completed this work over the course of five years with the assistance of over a hundred volunteers and artisans (male and female). It was first exhibited in 1979 and is now permanently located at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York. Chicago's goal with the work was to "end the ongoing cycle of omission in which women were written out of the historical record." She came up with the idea while attending a dinner party in 1974, at which, she recalls, "The men at the table were all professors, and the women all had doctorates but weren't professors. The women had all the talent, and they sat there silent while the men held forth. I started thinking that women have never had a Last Supper, but they have had dinner parties." Women were selected for inclusion based upon the following criteria: making a worthwhile contribution to society, striving to improve the situations of other women, making an impact on women's history, and serving as a role model for a "more egalitarian future". Dinner Party was a watershed moment for the centralization of female stories within an artworld context. It also provoked significant discussion around the correct way to represent women and their experiences. Although not universally praised by feminist critics (due to what some view as its essentialism), the piece asserted powerfully the necessity of engaging with female stories and brought into sharp relief the politics behind their previous exclusion. The work serves as an example of how women/feminist artists attempted to revise the (art) historical canon, calling attention to the historical accomplishments of women as a way to challenge the male-dominated nature of history writing. Such questioning provided a seed for other ways of dismantling assumptions around "talent" and artistic greatness that had been used to hinder the visibility of other minority groups in the art world, such as artists of color. Widely recognized as a classic of Feminist Art , Dinner Party can also be understood as an important precursor to Identity Art.

Ceramic, porcelain, and textile installation - Brooklyn Museum, New York

The Black Factory Archive

Artist: Pope.L

A traveling caravan, a community engagement initiative, a catalyst for conversation, Pope.L's The Black Factory Archive invites participation wherever his white truck stops with a deceptively simple proposition: Passers-by are asked to contribute an object that represents "blackness" to them. This process opens up space for reflection about which objects are associated with blackness (and why?) and what kind of history, social construction, and stereotyping are involved in the inscription of identity onto objects. Nearby, a gift shop is set up with everyday consumables and objects such as canned foods, bottled waters, t-shirts, and the ubiquitous yellow rubber duckies labeled The Black Factory. His truck always travels with a group of "staff"/performers, who "operate" the Factory, act out skits, and interact with the public. "The idea," the artist reflected, "is to maybe bring back some sense of a public square kind of atmosphere....You want people to feel that they can enter the discussion. At the same time, I don't want them to get the idea that the discussion is going to be easy." While racial identity is often seen as inherent based on biological markers such as skin color, historians and theorists have shown how the category of "race" itself was a social construct that only emerged from the eighteenth century onward, with the confluence of Enlightenment classification thinking and the white subjugation of peoples racialized as Other and therefore "savage" and inferior. The history - and continuing reverberations--of slavery in America is inextricably tied with this theory of race. Born in 1955, African-American Pope.L makes provocative works drawing on performance, public intervention, and other mediums that confront viewers with America's slavery past and the present experience of blackness today. By asking an open-ended question about identity, the Black Factory Archive demonstrates the multiple viewpoints that can be brought to bear on an identity. It also highlights how, in addition to individual and collective histories, material culture, too, plays a crucial role in the shaping of identity and vice versa.

Performance and moving installation - Museum of Modern Art

Artifact Piece

Artist: James Luna

In this performance, Luna lay in an exhibition case in the section on the Kumeyaay Indians in San Diego's Museum of Man wearing only a leather loincloth. Around his body, he placed labels describing the origins of his various scars (for instance, "excessive fighting" and "drinking"), as well as several personal effects, including ritual objects used currently on the La Jolla reservation, where Luna lived. Also included were Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix records, shoes, political buttons, college diplomas, and divorce papers. Luna lay in the case for several days during the opening hours of the museum, occasionally surprising visitors by moving or opening his eyes to look at them. Luna (1950-2018) was a Payómkawichum, Ipi, and Mexican-American artist, born in Orange, California, who moved to the La Jolla Indian Reservation in California at the age of 25. The following year, he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at the University of California, Irvine, and seven years later a Master of Science degree in counselling from San Diego State University. His goal with this work was to bring attention to how cultural institutions tended to romanticize or present indigenous culture as extinct, lost, or pure and untouched by change. As art critic Jean Fisher writes, Luna was thus exposing "the necrophilous codes of the museum," that is, the way that cultural institutions make corpses out of living Indigenous peoples and cultures. Luna remarked: "I had long looked at representation of our peoples in museums and they all dwelled in the past. They were one-sided. We were simply objects among bones, bones among objects, and then signed and sealed with a date." By directly confronting museum-goers with his own living, breathing body, he forced them into a jarring moment in which they had to confront their own ethnographic assumptions and prejudices. He recalled that many of the visitors spoke about him as if he weren't there, even after they realized he was, in fact, alive. The array of ritual and secular objects with which he surrounded himself served to further emphasize the hybrid reality of contemporary indigenous life and culture. He said of the work, "In the United States, we Indians have been forced, by various means, to live up to the ideals of what 'Being an Indian' is to the general public: In art, it means the work 'Looked Indian', and that look was controlled by the market. If the market said that it (my work) did not look 'Indian,' then it did not sell. If it did not sell, then it wasn't Indian. I think somewhere in the mass, many Indian artists forgot who they were by doing work that had nothing to do with their tribe, by doing work that did not tell about their existence in the world today, and by doing work for others and not for themselves." Luna went on to explain that "It is my feeling that artwork in the medias of Performance and Installation offers an opportunity like no other for Indian people to express themselves in traditional art forms of ceremony, dance, oral, traditions and contemporary thought, without compromise. Within these (nontraditional) spaces, one can use a variety of media, such as found/made objects, sounds, video and slides so that there is no limit to how and what is expressed." In this way, he challenged the white gaze that objectifies others, such as Native Americans. As Fisher writes, Luna aimed to "disarm the voyeuristic gaze and deny it its structuring power," by placing himself in a position of power (as he was in control of when and to whom he chose to reveal his 'aliveness,' thereby implicating museum-goers in the performance without their previous knowledge or consent). This strategy has also been undertaken by other indigenous artists and artists of color, most notably Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Coco Fusco, and the performance group La Pocha Nostra.

Performance - San Diego Museum of Man

Rainbow Series # 14

Artist: Candice Breitz

This image uses collage to splice together images taken from postcard photographs produced in South Africa in the 1990s and Western pornography. A bizarre hybrid creature is thus created, comprised of a Black African topless female from the waist up, and a white naked female from the waist down, wearing knee-high red leather boots and thigh-high red fishnet stockings. The white female hand, with red painted fingernails, provocatively reaches around her buttocks to hold open her vagina to the viewer. South African artist Candice Breitz was born in Johannesburg in 1972, and currently lives and works in Berlin, Germany where she also works as a professor at the Braunschweig University of Art. In Rainbow Series , Breitz explored and critiqued the competing cultural representations of, and influences on, post-Apartheid South Africa. In the wake of Apartheid, South Africa sought to re-negotiate its identity as the "Rainbow nation" (a national slogan adopted for a time in the 1990s), that is, a country in which individuals and communities of various ethnic and cultural backgrounds co-existed peacefully. Part of this project involved the production of tourist postcards, many of which presented indigenous-looking Black Africans in rural settings. The images, however, were carefully constructed, and used models rather than "real" people. At the same time, South Africa was beginning to open its doors to foreign media, which led to the importation of a significant amount of Western pornography. Thus, during the 1990s, South Africans were flooded with highly sexualized images that almost exclusively featured white women. Breitz stated that the images in the Rainbow Series "were my response to the contagious post-Apartheid metaphor of a South African 'Rainbow Nation,' a metaphor which tends to elide significant cultural differences amongst South Africans in favour of the construction of a homogeneous and somehow cohesive national subject." The photomontage technique used by Breitz in this series is anything but polished, with her cuts between the images harsh and crude. For Breitz, this method served as a metaphor for the violence that continues to be carried out against women, as well as the ongoing, tumultuous process of identity negotiation in South Africa. As Brietz said, "It probably has something to do with my constant awareness of just how many women are getting cut up out there, literally or otherwise. [...] The Rainbow People are reconstituted as violently sutured exquisite corpses, fragmented and scarred by their multiple identities. They are far from the romanticised hybrid imagined by certain postmodern writers; or the seamless, slick, computer-generated images which some artists produce. Rather, at a time when porn is (at least for the moment) freely available in South Africa for the first time in decades, and when inner Johannesburg maintains the dubious distinction of having one of the highest rape and murder rates in the world, this series is, specifically, a perverse take on the composite subject making up the imaginary tribe which is said to populate the "New" South Africa." This use of photomontage is an example détournement, a Situationist strategy that re-uses preexisting media in a way that is critical of or oppositional to the original. With The Rainbow Series , Breitz calls attention to intersectionality, or the multiple, overlapping, inextricable aspects of identity that complicate one another, such as the way that gender identity is further complicated by racial identity. In a 1996 interview she reflected that "Although we're focusing our conversation on gender here, I think the discussion must be extended to other struggles around identity, for example race or class or ethnicity. A feminism that does not take these struggles into account is not going to have any real power. We all experience multiple forms of identification, and our identity position is never exclusively 'male' or 'female' or 'black' or 'white.'"

Cibachrome print

Stories of a Body

Artist: Mary Duffy

This performance begins in a pitch-black room, and as the darkness and silence begin to grow uncomfortable for the audience, Duffy emerges, naked and harshly spot-lit from the front. Audience members are confronted by Duffy's "severely disabled" body, which bears a considerable likeness to the Venus de Milo, raising the ironic observation that one of art history's most iconic representations of feminine beauty is, in fact, armless. Mary Duffy (born 1961) was one of the key figures in the development of Disability Arts in the UK. She is an Irish painter and performance artist who graduated from the National College of Art and Design in 1983 and went on to complete a Master's degree in Equality Studies from University College Dublin. In 2003, she was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Laws by the National University of Ireland in recognition of her contributions to the international Disability Arts movement. Duffy was born without arms as a result of thalidomide poisoning. Thalidomide was frequently prescribed in the 1950s and early 1960s for the treatment of nausea during pregnancy. It was later discovered that the use of thalidomide during pregnancy frequently resulted in severe birth defects. From a young age, Duffy became adept at using her feet and toes to perform many of the tasks typically performed with hands, including drawing and painting. Duffy recognized that the vast majority of representations of disability had not only been created by non-disabled individuals, but that they also had contributed to widespread and overwhelmingly deleterious attitudes toward understandings of disability. She writes, "In 1980, while at art college, I began to look at, and to question, my own fragile identity as someone who was very definitely different, disabled, and therefore, without any relevant cultural reference points. There were disability reference points all right, but they had been created by non-disabled people and regarded disabled people as tragic, pathetic, or brave. These images were so far removed from my own experience, I had to search for an image of disability I could be proud of, an image that did not reek of emotion or pity, an image that reflected disability as being a part of being human and all the richness and diversity that that entails." Duffy performed this work at numerous venues between 1990-2000. Writing about the motivations and intentions behind Stories of a Body , she states "...in doing this performance, by standing here, naked in front of you, I am trying to hold up a mirror for you, I am making you question the nature of your voyeurism." In this way, Duffy's performance sought to challenge the particular mode of looking, or rather "staring" that historically characterized, and continues to characterize, visual encounters between the able-bodied and the visibly disabled. Duffy thus challenged viewers to recognize identity, disability, and difference as constituted through processes of looking and staring. According to Critical Disability Studies scholar Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, "staring" is an "intense form of looking [that] constitutes disability identity by manifesting the power relations between the subject positions of disabled and able-bodied." Garland-Thomson notes that "Staring at disability choreographs a visual relation between a spectator and a spectacle [...] By intensely telescoping looking toward the physical signifier for disability, staring creates an awkward partnership that estranges and discomforts both viewer and viewed [...] Because staring at disability is considered illicit looking, the disabled body is at once the to-be-looked-at and not-to-be-looked-at, further dramatizing the staring encounter by making viewers furtive and the viewed defensive. Staring thus creates disability as a state of absolute difference rather than simply one more variation in human form."

Performance - International Touring from 1990

Becoming an Image

Artist: Cassils

In this performance originally carried out at the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives in Los Angeles, a 1500-lb block of clay sat in the center of a pitch-black room. Canadian, gender non-conforming and transmasculine artist Cassils proceeded to physically modify the block using the force of their own body, kicking and punching the clay in order to alter its form for 24 minutes. Photographs of the performance, which went on to be shown in other exhibitions of Cassils' work (alongside the modified blocks of clay), present the artist in the throes of this strenuous activity, grimacing and dripping sweat. Audio of the performance was also recorded and presented at subsequent exhibitions, with the sound of Cassils' physical exertion presented as an integral part of the work. Cassils trained with a professional Muay Thai boxer to prepare for the performance in which they physically attacked the block of clay. Through the intense effort it required to physically re-shape the clay, Cassils offered a commentary on the amount of work it takes to develop and maintain one's body, and simultaneously, one's identity. The violence of their activity also alludes to the violence experienced by trans individuals around the world. Indeed, Cassils understands the modified block of clay as a monument to trans people's perseverance and fortitude. The performance was carefully constructed to withhold full visibility from the viewer. Sporadic camera flashes from collaborator Manuel Vason illuminated Cassils for only brief moments, providing viewers with mere glimpses of the intense performance. This setting may be understood as a metaphor for the difficulty of seeing the work and endurance of trans people for cisgender individuals.

Performance - ONE Archives, LA / International Touring

Beginnings of Identity Art

While many artistic traditions and practices can be understood as an expression of identity, whether individual or collective, Identity Art in the twentieth century had its starting point in the questioning of the art world's gate-keeping that had excluded non-dominant groups from participation. In the 1960s, both second-wave feminism and the civil rights movement exposed how discrimination and prejudices based on gender and race worked in upholding the dominance of white, male, heterosexual artists, curators, and arts patrons. Although operating rather like parallel tracks at first, both movements created ripple effects that would converge in later decades.

Second-Wave of Feminism

The first wave of feminism, in the first half of the twentieth century, focused largely on legal issues such as women's right to vote. Building on this social activism, second-wave feminists in the 1960s and 70s drew attention to the broader relegation of women to the domestic sphere, and the way that Western society perpetuates stereotypes about "essential" female qualities and the "proper" role of women: a patriarchal hierarchy in which women are seen as inferior and subservient to men. Feminist artists during this period also aimed to draw attention to these issues in their work. Some sought to revise the art historical canon, as well as historical reflection more broadly, both of which had tended to exclude the accomplishments of women and focus only on the achievements of great men. Linda Nochlin 's 1971 essay "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" was a foundational text in the call to address the imbalance within the art historical canon. Others sought to question stereotypes and the idea of gender essentialism, or the notion that gender (although the theory can also be extended to sexuality, race, ethnicity, etc.) is fixed, static, and unchanging, defined by innate/inherent traits. An essentialist view of gender states that women are inherently bad at math and science, for example, and this view has historically been used as justification for limiting educational and employment opportunities for women in these fields, further perpetuating the stereotype.

In 1975, British film theorist Laura Mulvey published an essay titled "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," in which she argued that narrative film (as well as other popular media formats) generally presents women as the object of a male scopophilic gaze, and, moreover, that female viewers participate in narcissistic identification, meaning that they receive pleasure from being objectified in this way. Mulvey's arguments echoed those of English art critic John Berger, who critiqued men's visual dominance in his 1972 TV series Ways of Seeing , stating that "Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. " Many female artists around this time sought to challenge this hegemonic norm in their art.

Civil Rights Movement and Push for Racial Equality

Concurrent with the second wave of feminism was the Civil Rights movement, during which African-Americans fought not only to gain equal legal rights, but also to combat racist stereotypes and to define their own identity and culture. This latter aim had its beginning in several arts scenes in the early twentieth century, particularly the New Negro movement and the Harlem Renaissance. By the middle of the century, African-Americans, as well as other racial minority groups (such as Native Americans and Latinx communities) were creating art with the aim of calling attention to ongoing prejudice and injustices against their communities, and with the intent of calling into question the supposed superiority of art made by white artists. Key thinkers who contributed to this critique include Frantz Fanon (a psychiatrist, writer, and philosopher from the French colony of Martinique), who wrote about the experience of being an oppressed black person living in a white-dominated society; Edward Said (a Palestinian-American professor of literature), who developed the field of postcolonial studies and is best known for his book Orientalism (1978) in which he critiqued the Western world's cultural representations of the "Orient" (historically meaning what is now northern Africa and the Middle East); and Homi K. Bhabha (an Indian critical theorist) who further developed Said's theories pertaining to postcolonialism. The Civil Rights movement and critical theories of race, ethnicity, and postcolonialism all have greatly informed artists working on various aspects of identity to the present day.

“Primitivism” at MoMA, “The Decade Show,” and the 1993 Whitney Biennial

In 1984, the Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted an exhibition titled "'Primitivism' in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern," in which masterpieces of modern Western art were shown alongside "artifacts" from non-Western (mainly African and East Asian) cultures. Many critics of the show (and of the concept Primitivist Art) argued that the exhibition presented non-Western works as inferior to those of European and American artists rather than examining critical and historical dialogue between them. In response, curators from The New Museum of Contemporary Art, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and The Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, organized an exhibition in 1990, "The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s", which featured over 200 works by 94 artists from various countries and cultures who wanted to highlight and challenge the systemic exclusion of non-White, non-Western artists in major art institutions. Lisa Phillips, current director of the New Museum, said of "The Decade Show": "It took up homosexuality, gay sensibility, gender issues, and issues of race and identity. These were firsts in the museum world."

"The Decade Show" prompted many other institutions to address their treatment of non-white artists. One of the most significant outcomes of this shift was the organization of the 1993 Biennial exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which took as its main theme "the construction of identity." Then-director of the Whitney, David Ross, explained that contemporary artists "insist[ed] on reinscribing the personal, political, and social back into the practice and history of art." Ever since, artists like Kehinde Wiley , Renée Green, Byron Kim, Glenn Ligon , Pepón Osorio, and Lorna Simpson have continued to create art that provides a counter-narrative to the whiteness of Western art institutions.

Intersex, Queer, and Trans Rights Movements

Queer theory, first discussed by scholar Teresa de Laurentis in 1991, as well as the gay-, queer-, and transgender-rights movements (which gained momentum throughout the twentieth century), has been accompanied by many artists who have worked to foreground pressing issues within the queer community, such as HIV/AIDS (particularly in the 1980s), as well as ongoing struggles against violence and stigmatization. Here, "queer" is used to reclaim the formerly pejorative term which has been used to designate non-normative (non-heterosexual) sexual identities. This usage derives from the work of de Lauretis, and has been further developed in recent decades by later queer theorists. Overall, queer theorists and artists work to question and critique essentialist notions of sexuality, the widespread view in culture-at-large of sexual identities as fixed and biologically determined, as well as the heteronormative ideals of family life and forms of kinship that are historically and culturally conditioned yet often seen as "natural."

An important theoretical underpinning of queer theory is Judith Butler's concept of performativity. First theorized in 1988 in her work on gender, performativity dictates that gender is tenuously constituted in time through stylized repetition of acts. These acts constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self, rather than a stable identity from which various acts proceed. Gender is thus distinct from sex, which corresponds to the biological or medical differentiations between men and women (although the instability of this binary sexual division is now also widely acknowledged by medical and scientific professionals). Queer theory has prompted revisionist accounts of art history and re-readings of major artworks through a queer lens. In turn, artworks by queer artists such as Andy Warhol have provided a productive testing ground for new ideas in queer theory, such as in the writing of art historian and queer theorist Douglas Crimp.

Disability Arts

Canadian disability researcher Jihan Abbas writes that, "The emergence of disability culture, and the importance of art forms and representations in this culture, must be seen as a natural extension of the disability rights movement, as the disability arts movement is essentially about the growing political power of disabled people over their images and narratives." Artists working within Disability Arts create and disseminate representations of their lived experiences of disability, challenging the problematic ways in which the vast majority of representations of disability have been constructed in popular culture. An artist or work may be classified as being a part of Disability Arts based on the artists' personal identification, their medical diagnosis, the experiences they encounter in their day-to-day life, the subject matter of their artwork, or any combination of the above. As disabled writer Allan Sutherland notes, "The movement that we describe as 'disability arts' has developed [since the 1980s] as disabled people have rejected negative assumptions about their lives, defined their own identities, expressed pride in a common disabled identity and worked together to create work that reflects the individual and collective experience of being disabled." Many proponents of Disability Arts firmly oppose conflating Disability Arts with art therapy, as they view art therapy as a biomedical tool that focuses on healing and repairing "broken" bodies. In the confusion between the two, the agency, identity, and the aesthetic value of disabled artist's works are diminished.

Identity Art & Identity Politics: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Identity politics.

It may be useful to differentiate between Identity Art as a broad category of art that explores issues of identity, on the one hand, and Identity Politics, which was a more historically specific term that became common in the art world (and public discourse) in the 1970s-1980s. Identity Politics was used to designate art that addressed race, gender, and sexuality, especially in the US context. Amidst the rise of Reaganism and right-wing politics in the 1980s, Identity Politics became a derogatory term used by critics as a way to dismiss the artistic contributions and boundary-pushing artists of color and queer artists (by framing them as "merely" about identity, and thus not fitting in with the skewed standards of the white-dominated art world). On the other hand, such dismissals furthered the argument of supporters of Identity Politics in showing the headwinds faced by minority artists who wished to make art by drawing on their life experiences.

Since then, there has been more acceptance of identity-focused art, even as "identity" can become both an entry-point and a limiting condition. Curators Anders Kreuger and Nav Haq point out that "Artists are allowed access to the art system on the condition that they have to act, or be framed, as socio-cultural representatives of the place/people they 'are from.'" The rise of Identity Politics in the art world, they argue, resulted in a transition "from marginalization (on the outside) to ghettoization (on the inside)."

Many contemporary artists are fully aware of the pitfalls of engaging with identity. Some would argue, however, that they don't have a choice but to address it: As the contemporary African-American artist Tschabalala Self noted, "All artists create identity-based work, but only some artists are asked about their identity [...] If some artists seem to make work that is ostensibly unconcerned with these realities, it's because they are not made to feel marginalized by them." So long as systemic marginalization and violence against groups based on perceived identity remain, questions of identity will continue to be part of many artists' reality. The terms of the debates may shift, just as our understanding of identity has evolved, but until parity and equal access to opportunity in the art world is truly achieved (not only for artists but also among museum professionals and staff), the critical reckoning of the art world's system of critical and monetary valuation will continue to be urgent for many.

Identity and Politics through Art: Interventions

While identity-related concerns were slow to be taken up by many Western art galleries and museums, a great deal of progress occurred outside the confines of institutions. Artists have often taken their work outside of traditional gallery spaces, or used the space of the gallery itself in ways that "intervene" in their usual function. Artists may create work that is unable to be viewed in a conventional manner, or situate their work within a more politically or socially charged context. They may even intervene in everyday life, inserting their art and politics into normal conversations or social interactions.

Feminist Performance artists, in particular, have been taking to the streets for decades, such as Austrian artist Valie Export , who between 1968-1971 enacted a public performance titled Tap and Touch Cinema in ten European cities. For this performance, the artist wore a miniature "movie theatre" around her naked upper body, covered by a curtain at the front, so that passers-by could not see her, but were invited to reach in and touch. Her aim with this work was to confront the public, in a tactile manner, with a living, breathing female body, attached to a face which responds and looks back, rather than a simple (yet highly constructed) passive visual image on a page or screen, to which they were more accustomed.

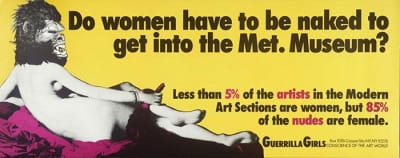

A later example is intersectional feminist group Guerrilla Girls, who have taken to the streets, putting up stickers, posters, and street projects in cities all over the world since 1985. The Guerrilla Girls' street interventions aim to highlight issues of injustice and inequality (both on the basis of gender and race) in the art world. For instance, in 1989, the group rented advertising spaces on buses in New York City, in which they inserted posters they had made calling attention to the fact that at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female."

Indeed, Street Art in its myriad forms has proven to be an ideal medium for artists who seek to address Identity Politics in their work, as it allows for uncensored expression in public locations with large numbers of potential viewers. For instance, Montreal-based MissMe, who works primarily in wheat paste posters, installs street art that challenges outdated patriarchal attitudes and empowers women. In a 2018 street installation, she called into question the male-centred Christian origin story (in which the first women grew from the first man) while simultaneously reminding viewers of the pain and sacrifice demanded of women as bearers of new life, asserting that "I didn't come from your rib, you came from my vagina."

Even when not literally on the street, artists engaged in Identity Art still "intervene" in the expected viewer/artist relationship. Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta's 1973 multi-media installation and performance Untitled (Rape Scene) , for example, was a feminist piece created to foreground the high incidence of rapes and murders of women that were occurring on the University of Iowa campus while she was in attendance there. Audience members arrived via an elevator to be immediately confronted with the scene within the confines of a regular apartment, forcing them to contemplate a realistic scene of rape outside the distancing and "safe" space of a gallery. It was also possible that members of the campus community who were not aware of the performance could enter and think it the aftermath of a real assault, blurring the line between art and real experience. The work highlighted the urgency of the issue and the reality of being a woman at the time.

Public intervention has proved to be a highly effective strategy for artists of color seeking to create art that reflects the struggles of their communities, particularly in the context of living in predominantly white areas, states, and countries. American artist Adrian Piper , for example, who is African-American but could pass as white due to her light skin tone, carried out a performance in 1989-1990 titled My Calling Card #1 , in which she passed out a small card in various social situations to individuals around her who made racist remarks in her presence. The card informed readers that Piper is in fact black, although they may not have been aware of that, and that the racist comment they had just "made/laughed at/agreed with" was in fact discomforting to her. The performance was one that played out within everyday life, with only the documentation (in the form of the calling cards themselves) available for display as a record of the intervention.

Disabled artists have also made regular interventions into the relationship between art and audience. An important early work of the Disability Arts movement is English artist Tony Heaton's 1989 sculptural intervention titled Wheelchair Entrance . The work was composed of a wooden board labelled "wheelchair entrance" which was hung across a gallery doorway at a height that blocked ambulatory visitors but permitted entrance beneath it to anyone in a wheelchair. The work acted as a simple but effective means by which to make gallery visitors aware of architectural barriers to mobility. Moreover, it encouraged an embodied engagement with disability by forcing ambulatory visitors to confront a moment of physical limitation without attempting to explain or analyze the encounter, simply allowing it to create meaning through the perspective of the body. This piece reflects the social model of disability now prevalent in civic and political discourse - the idea that it is not someone's body which disables them, but the society around them. A person is prevented from entering a building not because they use a wheelchair, for example, but because there is no ramp. Heaton's intervention in the space reflects this, with the space "othering" ambulatory visitors and preventing their easy access.

Identity and Politics through Art: Critique on the Gallery Wall

Issues and politics of identity are not only played out in non-conventional spaces or in ways that are unfamiliar to art audiences. Many artists create work fully able to be displayed and evaluated as more conventional painting, installation, or sculpture, whilst still maintaining a strong political message about identity. This critique from within the gallery system often intersects with Institutional Critique , the questioning of the gallery system itself.

Frida Kahlo's work frequently depicted her experience of disability in her self-portraits (namely, the numerous broken bones and fractures she experienced as a result of a bus accident when she was a teenager, as well as her inability to carry a pregnancy to term, also a result of the accident). Her work highlights the intersectional position of her identity as both a woman and an artist with a disability, foregrounding, when considered in detail, the relative lack of both in museum and gallery collections. Historically, few artists dealing directly with issues of disability in their work are represented in museum collections or the international art market, but Kahlo has achieved a high level of renown, particularly in the twenty-first century.

Other artists have drawn on their sexual identity explicitly in their work, with the rise of the gay rights movement (and related movements, such as the transgender rights movement) after the Stonewall riots in 1969 in particular encouraging LGBTTQQIAAP (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, queer, questioning, intersex, asexual, ally, and pansexual, henceforth referred to simply as "queer") artists to create works that take up issues prevalent in their communities, such as HIV/AIDS, violence, abuse, stigma, and acceptance. One notable example - of what is sometimes called Queer Art - is David Wojnarowicz , who dealt with pressing issues within the queer community in his work. Wojnarowicz was a target of the "culture wars" of the 1980s and 1990s in the United States, wherein artists dealing with sensitive (often identity-based) content and imagery in their works were attacked by various organizations (including the American Family Association and the Catholic League) on the basis of creating and disseminating what were claimed to be vulgar, immoral, or gratuitous images that were unworthy of the gallery. Other artists who fell victim to the "culture wars" (by being denied funding, as well as receiving harsh disparagement) include Robert Mapplethorpe , Andres Serrano , Karen Finley, Tim Miller, John Fleck, and Holly Hughes.

Despite this political oppression, Wojnarowicz's work has now achieved significant curatorial interest, culminating in his 2018 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Like Kahlo's work, it draws attention explicitly to an injustice on the basis of identity and highlights the absence of explicit acknowledgement of minority positions in curatorial agendas. The success of Identity Art is in part encapsulated by the reassessment and incorporation of ideas previously on the fringes into a mainstream process of art world acknowledgement.

Later Developments - After Identity Art & Identity Politics

Today many contemporary artists use art as a tool in the (re-)negotiation of multiple aspects of identity that operate together - or intersectionally - rather than separately. The term intersectionality was first coined in 1989 by race and gender law scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, who argued that an individual cannot be defined by a single identity, such as gender, but that different aspects of a person's identity work together to determine their social standing, privileges and/or disadvantages. These include (but are not limited to) gender, race/ethnicity/diaspora, sexuality, and disability, as well as class, body type, and age.

Other scholars have proposed using the term "post-identity (politics)", which is related to the concept of posthumanism. Post-identity thinking has its basis in the theories of Nietzsche, Foucault, and Deleuze and Guattari, and argues for an understanding of identity as a process of becoming, characterized by flux, change, impermanence, incoherence, and unpredictability. Many of today's identity-focused artists are incorporating ideas of post-identity into their works, such as the participants in a 2014 exhibition As We Were Saying: Art and Identity in the Age of "Post" at the EFA Project Space in New York. One sculpture in the show, In Spirit of (a Major in Women's Studies) by A. K. Burns and Katherine Hubbard, consisted of a wastebasket filled with various objects, including a studded leather belt, an electrical power strip, confetti, plastic snakes, and a rose made of feathers. These objects do not easily correspond to any one recognizable "identity," but invite multiple associations, even as they are found, after all, in a wastebasket evoking a sense of irrelevance or a lack of value. The work thus insists upon identity as incoherent and imperceptible rather than fixed and knowable.

With multiple facets of identity explored through art and with many artists moving beyond "identity" as such, Identity Art today may be understood less as a fixed category or style, but as an awareness that many artists bring to their artmaking processes (even so as to critique or complicate it). It can also be a critical and historical lens through which we can approach artworks, including those that were not made with "identity" in mind.

Useful Resources on Identity Art & Identity Politics

- Through The Flower: My Struggle as A Woman Artist By Judy Chicago

- Cindy Sherman By Eva Respini and Johanna Burton

- Meet Cindy Sherman: Artist, Photographer, Chameleon By Sandra Jordan and Jan Greenberg

- Women Photographers: From Julia Margaret Cameron to Cindy Sherman By Boris Friedewalde

- Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions By Glenn Ligon, Francesco Manacorda, Alex Farquharson, Gregg Bordowitz

- Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic By Eugenie Tsai

- Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s History and Impact By Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard

- Art and Feminism Our Pick By Helena Reckitt

- Disability Aesthetics By Tobin Siebers

- Re-Presenting Disability: Activism and Agency in the Museum By Richard Sandell, Jocelyn Dodd, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson

- Cindy Sherman: The Complete Untitled Film Stills Our Pick By Peter Galassi

- Race-ing Art History: Critical Readings in Race and Art History Our Pick By Kymberly N. Pinder

- How To See A Work of Art in Total Darkness By Darby English

- Art and Queer Culture By Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer

- Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility By Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton

- Judy Chicago, the Godmother Our Pick By Sasha Weiss / The New York Times Style Magazine / Feb. 7, 2018

- The Topic Is Race; the Art Is Fearless Our Pick By Holland Cotter / The New York Times / March 30, 2008

- How Identity Politics Conquered the Art World: An Oral History Our Pick By Jerry Saltz and Rachel Corbett / Vulture / April 18, 2016

- At the Whitney, A Biennial with a Social Conscience By Roberta Smith / The New York Times / March 5, 1993

- Don't You Know Who I Am? Art After Identity Politics Our Pick Exhibition catalogue / Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp / June 13, 2014

- Becoming an Image: Heather Cassils

Similar Art

Can Fire in the Park (1946)

Cut Piece (1964)

Jim and Tom, Sausalito (1977)

Related artists, related movements & topics.

Content compiled and written by Alexandra Duncan

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Paisid Aramphongphan

Brill | Nijhoff

Brill | Wageningen Academic

Brill Germany / Austria

Böhlau

Brill | Fink

Brill | mentis

Brill | Schöningh

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

V&R unipress

Open Access

Open Access for Authors

Open Access and Research Funding

Open Access for Librarians

Open Access for Academic Societies

Discover Brill’s Open Access Content

Organization

Stay updated

Corporate Social Responsiblity

Investor Relations

Policies, rights & permissions

Review a Brill Book

Author Portal

How to publish with Brill: Files & Guides

Fonts, Scripts and Unicode

Publication Ethics & COPE Compliance

Data Sharing Policy

Brill MyBook

Ordering from Brill

Author Newsletter

Piracy Reporting Form

Sales Managers and Sales Contacts

Ordering From Brill

Titles No Longer Published by Brill

Catalogs, Flyers and Price Lists

E-Book Collections Title Lists and MARC Records

How to Manage your Online Holdings

LibLynx Access Management

Discovery Services

KBART Files

MARC Records

Online User and Order Help

Rights and Permissions

Latest Key Figures

Latest Financial Press Releases and Reports

Annual General Meeting of Shareholders

Share Information

Specialty Products

Press and Reviews

Art and Identity

Essays on the aesthetic creation of mind, series: consciousness, literature and the arts , volume: 32.

Prices from (excl. shipping):

- Paperback: €70.00

- E-Book (PDF): €70.00

- View PDF Flyer

Biographical Note

Review quotes, table of contents, share link with colleague or librarian, product details.

- Literature, Arts & Science

- Aesthetics & Cultural Theory

- Cultural Studies

Collection Information

- Literature and Cultural Studies E-Books Online, Collection 2013

Related Content

Reference Works

Primary source collections

COVID-19 Collection

How to publish with Brill

Open Access Content

Contact & Info

Sales contacts

Publishing contacts

Stay Updated

Newsletters

Social Media Overview

Terms and Conditions

Privacy Statement

Cookie Settings

Accessibility

Legal Notice

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Statement | Cookie Settings | Accessibility | Legal Notice | Copyright © 2016-2024

Copyright © 2016-2024

- [66.249.64.20|185.39.149.46]

- 185.39.149.46

Character limit 500 /500

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Introduction - Art and Identity: Essays on the Aesthetic Creation of Mind

2013, Brill

Related Papers

PORTO ARTE: Revista de Artes Visuais

Luciano Simão

Rob Luzecky

Alessandro Bertinetto , Jerrold Levinson , Gerard Vilar , Matilde Carrasco Barranco

The articles in this issue of CoSMo explore possible ways to understand the specific qualities of aesthetics, its areas of application, its relationship with the practices of artistic production, aesthetic enjoyment, and critical interpretation. They also discuss the complex relationship between the reflection on aesthetic experience and its quality and, on the one hand, the problems raised by contemporary art (which often seems to require a kind of non-aesthetic experience of understanding and appreciation) and, secondly, the emergence of new potential areas of aesthetic enjoyment (like cooking and food appreciation).

The Journal of Aesthetic Education

Richard Shusterman

Paul Crowther

This discussion is the basis of Chapter 1 of my book The Aesthetics of Self-Becoming: How Art Forms Empower, Routledge, 2019. The book develops all the ideas presented below, in much greater detail. If aesthetics is to re-establish its philosophical importance a change is needed. Instead of engaging with art mainly through the crude notion of expressive qualities, or making it speak through the voice of ‘authorities’, we need a Copernican turn. This means a re-orientation of aesthetics towards i) those experiential needs which give rise to art, ii) the way they are articulated through artistic creation, and iii) a clarification of the unique effects consequent upon this creation. In the present discussion I offer an approach to all these issues. My starting point is the origin of art. This question is usually approached from an ontogenetic or phylogenetic viewpoint. However, my approach is different – centring on why human beings need to create art in the first place. This has ontogenetic and phylogenetic implications, but as expressions of a greater experiential whole - where the need for art can be seen to emerge from factors conceptually basic to self-consciousness as such. Part One, accordingly, outlines the horizonal basis of our experience of time and space, and then four key cognitive competences which are necessary to this experience. Emphasis is given to the importance of the aesthetic in its narrative form, as a further necessary feature emergent from these competences. Part Two outlines how literature, music, and pictorial art engage with this narrative feature in unique ways on the basis of their distinctive individual ontologies. They transform the aesthetic narrative of experience by embodying it in a more enduring and lucid form than can be attained at the purely experiential level. In this way, art embodies self-becoming, i.e. the developing of one’s own individuality in relation to others, and symbolic compensation for things otherwise lost in the passage of time. (This is a much extended and revised version of a paper on The Need for Art, and the Aesthetics of Self-Consciousness done a s a keynote address at the European Society of Aesthetics annual conference, Dublin Institute of Technology, 11th June, 2015)

The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

Alan H . Goldman

Mónica Uribe-Flores

The present paper discusses the possibility that aesthetic perception and interpretation reveal themselves as mutually inclusive within the same aesthetic experience of art in a non-trivial way. It will take its point of departure from Hans-Georg Gadamer and Nöel Carroll. Although they belong to different traditions, both philosophers nonetheless coincide in their indication that the experience of art overflows the region of perception and enjoyment of the aesthetic qualities of works of art. Yet while Gadamer subordinates aesthetic perception and maintains that the experience of art is necessarily hermeneutical, Carroll proposes that the aesthetic and the hermeneutical are two equally genuine responses to art. My claim is that perceptual elements in a work of art are decisive for interpretation, and that this should be properly considered when examining the aesthetic experience of art.

Journal of Aesthetic Education

Ciaran Benson

Alfredo Vernazzani