- Subject Guides

Being critical: a practical guide

- Critical writing

- Being critical

- Critical thinking

- Evaluating information

- Reading academic articles

- Critical reading

This guide contains key resources to introduce you to the features of critical writing.

For more in-depth advice and guidance on critical writing , visit our specialist academic writing guides:

What is critical writing?

Academic writing requires criticality; it's not enough to just describe or summarise evidence, you also need to analyse and evaluate information and use it to build your own arguments. This is where you show your own thoughts based on the evidence available, so critical writing is really important for higher grades.

Explore the key features of critical writing and see it in practice in some examples:

Introduction to critical writing [Google Slides]

While we need criticality in our writing, it's definitely possible to go further than needed. We’re aiming for that Goldilocks ‘just right’ point between not critical enough and too critical. Find out more:

Forthcoming training sessions

Forthcoming sessions on :

CITY College

Please ensure you sign up at least one working day before the start of the session to be sure of receiving joining instructions.

If you're based at CITY College you can book onto the following sessions by sending an email with the session details to your Academic Liaison Librarian:

There's more training events at:

Quoting, paraphrasing and synthesising

Quoting, paraphrasing and synthesising are different ways that you can use evidence from sources in your writing. As you move from one method to the next, you integrate the evidence further into your argument, showing increasing critical analysis.

Here's a quick introduction to the three methods and how to use them:

Quoting, paraphrasing and synthesising: an introduction [YouTube video] | Quoting, paraphrasing and synthesising [Google Doc]

Want to know more? Check out these resources for more examples of paraphrasing and using notes to synthesise information:

Using evidence to build critical arguments

Academic writing integrates evidence from sources to create your own critical arguments.

We're not looking for a list of summaries of individual sources; ideally, the important evidence should be integrated into a cohesive whole. What does the evidence mean altogether? Of course, a critical argument also needs some critical analysis of this evidence. What does it all mean in terms of your argument?

These resources will help you explore ways to integrate evidence and build critical arguments:

Building a critical argument [YouTube] | Building a critical argument [Google Doc]

- << Previous: Critical reading

- Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 5:46 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/critical

Library Guides

Critical thinking and writing: critical writing.

- Critical Thinking

- Problem Solving

- Critical Reading

- Critical Writing

- Presenting your Sources

Common feedback from lecturers is that students' writing is too descriptive, not showing enough criticality: "too descriptive", "not supported by enough evidence", "unbalanced", "not enough critical analysis". This guide provides the foundations of critical writing along with some useful techniques to assist you in strengthening this skill.

Key features of critical writing

Key features in critical writing include:

- Presenting strong supporting evidence and a clear argument that leads to a reasonable conclusion.

- Presenting a balanced argument that indicates an unbiased view by evaluating both the evidence that supports your argument as well as the counter-arguments that may show an alternative perspective on the subject.

- Refusing to simply accept and agree with other writers - you should show criticality towards other's works and evaluate their arguments, questioning if their supporting evidence holds up, if they show any biases, whether they have considered alternative perspectives, and how their arguments fit into the wider dialogue/debate taking place in their field.

- Recognizing the limitations of your evidence, argument and conclusion and therefore indicating where further research is needed.

Structuring Your Writing to Express Criticality

In order to be considered critical, academic writing must go beyond being merely descriptive. Whilst you may have some descriptive writing in your assignments to clarify terms or provide background information, it is important for the majority of your assignment to provide analysis and evaluation.

Description :

Define clearly what you are talking about, introduce a topic.

Analysis literally means to break down an issue into small components to better understand the structure of the problem. However, there is much more to analysis: you may at times need to examine and explain how parts fit into a whole; give reasons; compare and contrast different elements; show your understanding of relationships. Analysis is to much extent context and subject specific.

Here are some possible analytical questions:

- What are the constituent elements of something?

- How do the elements interact?

- What can be grouped together? What does grouping reveal?

- How does this compare and contrast with something else?

- What are the causes (factors) of something?

- What are the implications of something?

- How is this influenced by different external areas, such as the economy, society etc (e.g. SWOT, PESTEL analysis)?

- Does it happen all the time? When? Where?

- What other factors play a role? What is absent/missing?

- What other perspectives should we consider?

- What if? What are the alternatives?

- With analysis you challenge the “received knowledge” and your own your assumptions.

Analysis is different within different disciplines:

- Data analysis (filter, cluster…)

- Compound analysis (chemistry)

- Financial statements analysis

- Market analysis (SWOT analysis)

- Program analysis (computer science) - the process of automatically analysing the behaviour of computer programs

- Policy Analysis (public policy) – The use of statistical data to predict the effects of policy decisions made by governments and agencies

- Content analysis (linguistics, literature)

- Psychoanalysis – study of the unconscious mind.

Evaluation :

- Identify strengths and weaknesses.

- Assess the evidence, methodology, argument etc. presented in a source.

- Judge the success or failure of something, its implications and/or value.

- Draw conclusions from your material, make judgments about it, and relate it to the question asked.

- Express "mini-arguments" on the issues your raise and analyse throughout your work. (See box Your Argument.)

- Express an overarching argument on the topic of your research. (See Your Argument .)

Tip: Try to include a bit of description, analysis and evaluation in every paragraph. Writing strong paragraphs can help, as it reminds you to conclude each paragraph drawing a conclusion. However, you may also intersperse the analysis with evaluation, within the development of the paragraph.

Your Argument

What is an argument?

Essentially, the aim of an essay (and other forms of academic writing, including dissertations) is to present and defend, with reasons and evidence, an argument relating to a given topic. In the academic context argument means something specific. It is the main claim/view/position/conclusion on a matter, which can be the answer to the essay (or research) question . The development of an argument is closely related to criticality , as in your academic writing you are not supposed to merely describe things; you also need to analyse and draw conclusions.

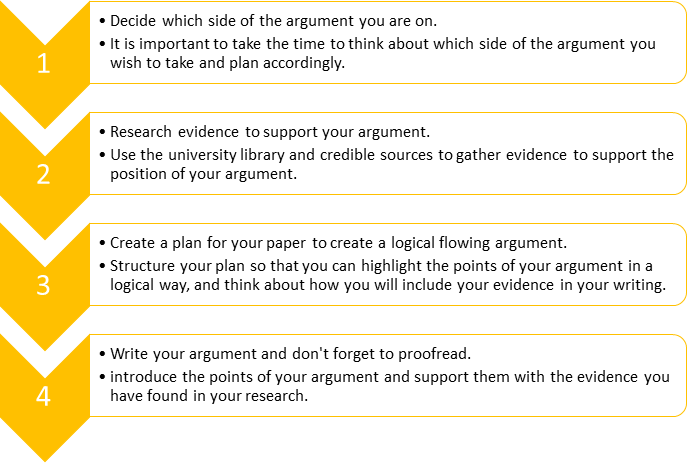

Tips on devising an argument

- Try to think of a clear statement. It may be as simple as trying to prove that a statement in the essay title is right or wrong.

- Identify rigorous evidence and logical reasons to back up your argument.

- Consider different perspectives and viewpoints, but show why your argument prevails.

- Structure your writing in light of your argument: the argument will shape the whole text, which will present a logical and well-structured account of background information, evidence, reasons and discussion to support your argument.

- Link and signpost to your argument throughout your work.

Argument or arguments?

Both! Ideally, in your essay you will have an overarching argument (claim) and several mini-arguments, which make points and take positions on the issues you discuss within the paragraphs.

- ACADEMIC ARGUMENTATION This help-sheet highlights the differences between everyday and academic argumentation

- Argument A useful guide developed by The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Useful resources

Learning Development, University of Plymouth (2010). Critical Thinking. University of Plymouth . Available from https://www.plymouth.ac.uk/uploads/production/document/path/1/1710/Critical_Thinking.pdf [Accessed 16 January 2020].

Student Learning Development, University of Leicester (no date). Questions to ask about your level of critical writing. University of Leicester . Available from https://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/ld/resources/writing/questions-to-ask/questions-to-ask-about-your-level-of-critical-writing [Accessed 16 January 2020].

Workshop recording

- Critical thinking and writing online workshop Recording of a 45-minute online workshop on critical thinking and writing, delivered by one of our Learning Advisers, Dr Laura Niada.

Workshop Slides

- Critical Thinking and Writing

- << Previous: Critical Reading

- Next: Presenting your Sources >>

- Last Updated: May 5, 2023 10:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/critical-thinking-and-writing

CONNECT WITH US

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 – Critical Writing

Critical writing depends on critical thinking. Your writing will involve reflection on written texts: that is, critical reading.

[Source: Lane, 2021, Critical Thinking for Critical Writing ]

Critical writing entails the skills of critical thinking and reading. At college, the three skills are interdependent, reflected in the kinds of assignments you have to do.

Now let’s look at some real university-level assignments across different majors. Pay attention to the highlighted words used in the assignment descriptions.

As you can tell, all the assignments have both critical reading and writing components. You have to read a lot (e.g., “Use at least 5 current Economics research articles,” “refer to 2 other documents,” and “Select 4-5 secondary sources”) and critically before you form your own opinions and then start to write. Sometimes reading is for ideas and evidence (i.e., reasons, examples, and information from sources), and other times reading is to provide an evaluation of information accuracy (e.g., research designs, statistics). Without critical thinking and reading, critical writing will have no ground. Critical thinking and reading are the prerequisites for critical writing. A clear definition of critical writing is provided below.

What is Critical Writing?

Critical writing is writing which analyses and evaluates information, usually from multiple sources, in order to develop an argument. A mistake many beginning writers make is to assume that everything they read is true and that they should agree with it, since it has been published in an academic text or journal. Being part of the academic community, however, means that you should be critical of (i.e. question) what you read, looking for reasons why it should be accepted or rejected, for example by comparing it with what other writers say about the topic, or evaluating the research methods to see if they are adequate or whether they could be improved.

[Source: Critical Writing ]

If you are used to accepting the ideas and opinions stated in a text, you have to relearn how to be critical in evaluating the reliability of the sources, particularly in the online space as a large amount of online information is not screened. In addition, critical writing is different from the types of writing (e.g., descriptive writing) you might have practiced in primary and secondary education.

The following table gives some examples to show the difference between descriptive and critical writing (adapted from the website ). Pay attention to the different verbs used in the Table for the comparisons.

You might feel familiar with the verbs used in the column describing critical writing. If you still remember, those words are also used to depict the characteristics of critical thinking and reading.

ACTIVITY #1:

Read the two writing samples, identify which one is descriptive writing and which one is critical writing, and explain your judgment.

Sample 1: Recently, President Jacob Zuma made the decision to reshuffle the parliamentary cabinet, including the firing of finance minister, Pravin Gordhan. This decision was not well received by many South Africans.

Sample 2: President Zuma’s firing of popular finance minister, Gordhan drastically impacted investor confidence. This led to a sharp decrease in the value of the Rand. Such devaluation means that all USD-based imports (including petrol) will rise in cost, thereby raising the cost of living for South Africans, and reducing disposable income. This puts both cost and price pressure on Organisation X as an importer of USD-based goods Y, requiring it to consider doing Z. Furthermore, political instability has the added impact of encouraging immigration, particularly amongst skilled workers whose expertise is valued abroad (brain drain).

[Source: Jansen, 2017, Analytical Writing vs Descriptive Writing ]

Further, to write critically, you also have to pay attention to the rhetorical and logical aspects of writing:

Writing critically involves:

- Providing appropriate and sufficient arguments and examples

- Choosing terms that are precise, appropriate, and persuasive

- Making clear the transitions from one thought to another to ensure the overall logic of the presentation

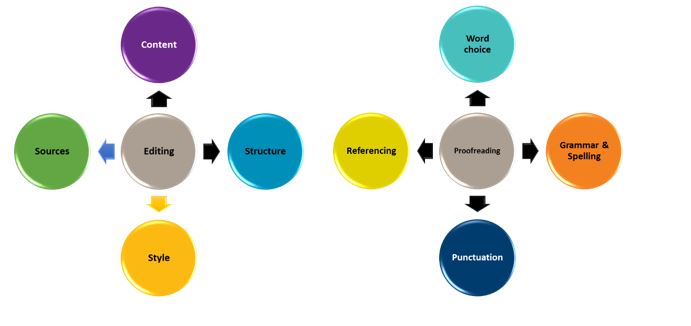

- Editing for content, structure, and language

An increased awareness of the impact of choices of content, language, and structure can help you as a writer to develop habits of rewriting and revision.

Regarding the content, when writing critically, you cannot just rely on your own ideas, experiences, and/or one source. You have to read a wide range of sources on the specific topic you are exploring to get a holistic picture of what others have discussed on the topic, from which you further make your own judgment. Through reading other sources, you not only form your own judgment and opinions but also collect evidence to support your arguments. Evidence is so important in critical writing. In addition to the collection of evidence, you also need to use different ways (e.g., quoting, paraphrasing, and synthesizing) to integrate the evidence into your writing to increase your critical analysis.

Using quotes is always an issue. Some students like to quote a lot and/or too long throughout their papers, and others do not know why they quote. Remember that when you use direct quotations, you are using others’ ideas, not yours. You should limit the use of quotes to the minimum because readers are always interested in your opinions. In other words, you need to use quotes critically.

When you quote directly from a source, use the quotation critically. This means that you should not substitute the quotation for your own articulation of a point. Rather, introduce the quotation by laying out the judgments you are making about it, and the reasons why you are using it. Often a quotation is followed by some further analysis.

[Source: Knott , n.d., Critical Reading Towards Critical Writing ]

Barna (2017) stated that “A good rule of thumb is that the evidence should only be about 5-10% of the piece.” Further, according to the EAP Foundation.org , you need to avoid doing a laundry list in critical writing:

You cannot just string quotes together (A says this, B says that, C says something else), without looking more deeply at the information and building on it to support your own argument.

This means you need to break down the information from other sources to determine how the parts relate to one another or to an overall structure or purpose [analysing], and then make judgements about it, identifying its strengths and weaknesses, and possibly ‘grey areas’ in between, which are neither strengths nor weaknesses [evaluating]. Critical reading skills will help you with this, as you consider whether the source is reliable, relevant, up-to-date, and accurate.

When and Why do you quote?

When should you use quotes?

Using quotations is the easiest way to include source material, but quotations should be used carefully and sparingly. While paraphrasing and summarizing provide the opportunity to show your understanding of the source material, quoting may only show your ability to type it.

Having said that, there are a few very good reasons that you might want to use a quote rather than a paraphrase or summary:

- Accuracy: You are unable to paraphrase or summarize the source material without changing the author’s intent.

- Authority: You may want to use a quote to lend expert authority for your assertion or to provide source material for analysis.

- Conciseness: Your attempts to paraphrase or summarize are awkward or much longer than the source material.

- Unforgettable language: You believe that the words of the author are memorable or remarkable because of their effectiveness or historical flavor. Additionally, the author may have used a unique phrase or sentence, and you want to comment on words or phrases themselves.

When you decide to quote, be careful of relying too much upon one source or quoting too much of a source and make sure that your use of the quote demonstrates an understanding of the source material. Essentially, you want to avoid having a paper that is a string of quotes with occasional input from you.

[Source: Decide when to Quote, Paraphrase and Summarize ]

How do you quote?

- With a complete sentence

- With “according to”

- With a reporting verb

- With a “that” clause

- As part of your sentence

Citing the islands of Fiji as a case in point, Bordo notes that “until television was introduced in 1995, the islands had no reported cases of eating disorders. In 1998, three years after programs from the United States and Britain began broadcasting there, 62 percent of the girls surveyed reported dieting” (149-50). Bordo’s point is that the Western cult of dieting is spreading even to remote places across the globe.

[Source: Lane, 2020, Quoting: When and How to Use Quotations ]

The firm belief which has been widely advertised is that “international students should be given equal rights and respect while studying abroad” (Lane, 2020, p. 19).

Smith, an agent working at an international company, put forward the seriousness of economic recession brought by the COVID-19 pandemic: “our economy will soon collapse, followed by business failures, elevated unemployment, and social turbulence ” (2021, p. 87).

Dominguez (2002) suggested, “teachers should reflect on their teaching constantly and proactively” to avoid teacher burnout and attrition (pp. 76-79).

According to the IEP student manual, “To study in the IEP you must be 18 years old and your English level must be ‘high beginner’ or higher” (p. 6).

[Source: Five Ways to Introduce Quotations ]

Now move on to the language aspect of critical writing, you should pay attention to the analytical verbs used in critical writing.

Analytical verbs are verbs that indicate critical thinking. They’re used in essays to dissect a text and make interpretive points, helping you to form a strong argument and remain analytical. If you don’t use analytical verbs, you may find yourself simply repeating plot points, and describing a text, rather than evaluating and exploring core themes and ideas.

[Source: What are Analytical Verbs? ]

The use of analytical verbs is also important to show your precision and appropriateness in language use. For example, instead of using says and talks, replace those verbs with states, discusses, or claims. Not only does it enhance the formality of the language, but also it helps to create the tone of writing. This further means that you have to understand the specific meaning, purpose, and function of each verb in a specific context as shown in the table below.

[Source: Impressive Verbs to use in your Research Paper ]

The verbs listed under each category are NOT synonyms and are different based on context. Please ensure that the selected verb conveys your intended meaning.

It is recommended that you check out Academic Phrasebank for more advanced and critical language use.

The accuracy of language use that is important for critical writing is also reflected in the use of hedges .

Hedging is the use of linguistic devices to express hesitation or uncertainty as well as to demonstrate politeness and indirectness.

People use hedged language for several different purposes but perhaps the most fundamental are the following:

- to minimize the possibility of another academic opposing the claims that are being made

- to conform to the currently accepted style of academic writing

- to enable the author to devise a politeness strategy where they are able to acknowledge that there may be flaws in their claims

[Source: What Is Hedging in Academic Writing?]

There are different types of hedges used in writing to make your claim less certain but more convincing. For example, what is the difference between the two sentences as shown below?

No hedging: We already know all the animals in the world.

With hedging: It’s possible that we may already know most animals in the world.

[Source: Hedges and Boosters ]

Check this table for different types of hedges.

[Source: Features of academic writing]

Practice how to tone down the arguments.

ACTIVITY #2

Add hedges to the following arguments.

Except for the content and language aspects of critical writing, the last aspect is the organization, including both the overall structure and the paragraph level.

Here is one example of a critical writing outline.

One easy-to-follow outline format is alphanumeric, which means it uses letters of the alphabet and numbers to organize text.

For example:

- Hook: _____________________

- Transition to thesis: _____________________

- Thesis statement with three supporting points:_____________________

- Topic sentence: _____________________

- Evidence (data, facts, examples, logical reasoning): _____________________

- Connect evidence to thesis: _____________________

- Restate thesis: _____________________

- Summarize points: _____________________

- Closure (prediction, comment, call to action): _____________________

[Source: Academic Writing Tip: Making an Outline ]

1. Introduction

- Thesis statement

2. Topic one

- First piece of evidence

- Second piece of evidence

3. Topic two

4. Topic three

5. Conclusion

- Summary/synthesis

- Importance of topic

- Strong closing statement

[Source: Caulfield, 2021, How to Write an Essay Outline]

ACTIVITY #3:

The following essay was adapted from a student’s writing. Please identify the components of each paragraph.

Artificial Intelligence: An Irreplaceable Assistant in Policy-making

Do you understand artificial intelligence (AI)? Are you excited that humans can create these machines that think like us? Do you ever worry that they develop too advanced to replace humans? If you have thought about these questions, you are already in the debate of the century. AI is a term used to describe machine artifacts with digital algorithms that have the ability to perceive contexts for action and the capacity to associate contexts to actions (Bryson & Winfield, 2017). The 21st century has witnessed a great number of changes in AI. As AI shows its great abilities in decision-making, humans are relying more on AI to make policies. Despite some concerns about the overuse of AI, AI is no longer to be replaced in policy-making because it has the capabilities that humans cannot achieve, such as transparent decision-making and powerful data processing.

AI has the capacity to use algorithms or systems to make the decision-making process more transparent (Walport & Sedwill, 2016). Many decisions made by humans are based upon their intuition rather than the direct result of the deliberate collection and processing of information (Dane et al., 2012). Intuition is useful in business when considering the outcome of an investment or a new product. However, in politics, the public would often question whether the policy is biased, so a transparent decision-making process should be used instead of intuition. AI can make political decisions more transparent by visualizing digital records (Calo, 2017). AI can make decisions without any discrimination and can have the public better understand of the policies.

In addition, AI can process a large amount of information at a speed faster than the cognitive ability of the most intelligent human policymakers (Jarrahi, 2018). A qualified policy must be based on facts reflected by data, so researching data is an essential part of policy-making. There are two main challenges for the human decision-makers in this area: (1) The amount of data is too large and (2) the relationship between data is too complex. Handling these two problems is where AI is superior. The high computing power of AI makes it an effective tool for retrieving and analyzing large amounts of data, thus reducing the complexity of the logic between problems (Jarrahi, 2018). Without AI, the policymakers would be overwhelmed by tons of data in this modern information age. It is almost impossible for them to convert those data into useful information. For example, data provided to the politician who is responsible for health care is mostly from the electronic health record (HER). HER is just the digital record transported from paper-based forms (Bennett et al., 2012). AI can analyze the data to generate clinical assessments, symptoms, and patient behavior and then link that information with social factors such as education level and economic status. According to the information from AI, the policy maker can make policies for healthcare improvement (Bennett et al., 2012). With the assistance of AI, the government can not only collect data easier but also utilize those data as operable Information.

However, while AI shows its great abilities in policy-making, it also brings considerable risks to contemporary society, and the most significant one is privacy. The only source for AI systems to learn human behavior is data, so AI needs to collect enormous quantities of information about users in order to perform better. Some scholars claim that the main problem with AI data collection is the use of data for unintended purposes. The data is likely to be processed, used, or even sold without the users’ permission (Bartneck et al, 2021). The 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal showed how private data collected through Facebook can be used to manipulate elections (Bartneck et al, 2021). While privacy is a crucial problem, this is a handleable problem and we cannot deny the benefits brought by using AI. The most appropriate way to solve this problem is to establish a complete regulatory system. In fact, many policies have been made to protect user privacy in AI data collection. One of safeguard in this area is to restrict the centralized processing of data. Researchers are also conducting a lot of research in this area and have achieved some technological breakthroughs. For example, open-source code and open data formats will allow a more transparent distinction between private and transferable information, blockchain-based technologies will allow data to be reviewed and tracked, and “smart contracts” will provide transparent control over how data is used without the need for centralized authority (Yuste & Goering, 2017).

In conclusion, although there may be some privacy-related issues with AI policies, the powerful data collection capabilities and transparent decision-making process of AI will bring many benefits to humans. In the future, AI is more likely to continue to serve as an assistant to humans when making policies under a complete and strict regulatory system.

Bartneck, Christoph. Lütge, Christoph. Wagner, Alan. Welsh, Sean. (2021). Privacy Issues of AI, pp.61-70. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-51110-4_8.

Bennett C, Doub T, Selove R (2012) EHRs Connect Research and Practice: Where Predictive Modeling, Artificial Intelligence, and Clinical Decision Support Intersect https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1204/1204.4927.pdf. Accessed 1 April 2021.

Bryson J and Winfield A (2017) Standardizing Ethical Design Considerations for Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems. http://www.cs.bath.ac.uk/~jjb/ftp/BrysonWinfield17-oa.pdf. Accessed 1 April 2021.

Calo, R (1993) Artificial Intelligence Policy: A Primer and Roadmap. https://lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/51/2/Symposium/51-2_Calo.pdf , Accessed 1 April 2021.

Dane, Erik., Rockmann, Kevin. W., & Pratt, Michael G. (2012). When should I trust my gut? Linking domain expertise to intuitive decision-making effectiveness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 119(2), 187—194.

Jarrahi, M. (2018). Artificial intelligence and the future of work: Human-AI symbiosis in organizational decision making, Business Horizons, Volume 61, Issue 4, Pages 577-586, ISSN 0007-6813, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.03.007.

Walport M, & Sedwill M. (2016). Artificial intelligence: opportunities and implications for the future of decision making. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attach ment_data/file/566075/gs-16-19-artificial-intelligence-ai-report.pdf, Accessed 1 April 2021.

Rafael, Y., & Sara, G. (2017). Four ethical priorities for neurotechnologies an AI https://www.nature.com/news/four-ethical-priorities-for-neurotechnologies-and-ai 1.22960. Accessed 1 April 2022.

Apart from the overall structure of critical writing, it is also important to pay attention to the paragraph-level structure. There are different paragraph models for critical writing.

Model 1: TED model for writing critical paragraphs

Paragraph model for critical writing

Often in assignments, you are expected to critically evaluate – this means to assess the relevance and significance of concepts relating to a specific topic or assignment question. Introduce your point. Give examples from reading. Is there support for your argument or can you identify weaknesses? Are there different perspectives to compare and contrast? Build your explanation and create your objective, reasoned argument (case or thesis) based on the evaluation from different perspectives. You will include your conclusion and point of view, communicating your stance, having made a judgment on research you have found and its significance in contributing to answering your assignment question.

Use the TED model to integrate critical thinking into your writing:

Each example of evidence in your writing should have a clear purpose or function. Be explicit and tell the reader what it contributes to your reasoning.

Professional practice is more complex than simply applying theory to practice, since it involves a professional juggling of situational demands, intuition, experiences and knowledge (Schön, 1991). Practitioners do not apply research findings in a simple deductive process; they need time to think, translate and relate the research findings to their particular setting. The extent to which a given piece of evidence is utilised by an individual in practice depends on their sense of the situation and this inevitably involves professional judgement.

Topic (in red); Evidence (in orange); Further explanation (in blue); Discussion (in green)

Model 2: WEED model for writing critical paragraphs

This is a model for writing critical paragraphs. It’s taken from Godwin’s book called ‘Planning your Essay’. Each paragraph should be on a single topic, making a single point. A paragraph is usually around a third of a page.

W is for What

You should begin your paragraph with the topic or point that you’re making so that it’s clear to your lecturer. Everything in the paragraph should fit in with this opening sentence.

E is for Evidence

The middle of your paragraph should be full of evidence – this is where all your references should be incorporated. Make sure that your evidence fits in with your topic.

E is for Examples

Sometimes it’s useful to expand on your evidence. If you’re talking about a case study, the example might be how your point relates to the particular scenario being discussed.

D is for Do

You should conclude your paragraph with the implications of your discussion. This gives you the opportunity to add your commentary, which is very important in assignments that require you to use critical analysis. So, in effect, each paragraph is like a mini-essay, with an introduction, main body, and conclusion.

Example: a good critical paragraph

Exposure to nature and green spaces has been found to increase health, happiness, and wellbeing. Whilst trees and greenery improve air quality by reducing air pollutants, green spaces facilitate physical activity, reduce stress, and provide opportunities for social interaction (Kaplan, 1995; Lachowycz,and Jones, 2011; Ward Thompson et al., 2012; Hartig et al., 2014; Anderson et al., 2016). Older adults have described increased feelings of wellbeing while spending time in green spaces and walking past street greenery (Finaly et al., 2015; Orr et al., 2016). They are more likely to walk on streets which are aesthetically pleasing (Lockett, Willis and Edwards, 2005) while greenery such as flowers and trees play an important role in improving the aesthetics of the environment (Day, 2008). Therefore, greater integration of urban green spaces and street greenery in cities may have the potential to increase physical activity and wellbeing in older adults.

What (in red), Evidence (in orange), Do (in blue).

[Source: Learning Hub, 2021 ]

Please identify the paragraph-level components in the following paragraphs. You can use different colors to indicate different components.

Social Media plays a key role in slowing the spread of vaccine misinformation. According to Nikos-Rose (2021) from the University of California, individuals’ attitudes towards vaccination can negatively be influenced by social media. They can simply post a piece of misleading information to the public, and the deceived ones will share it with their families and friends. The role of media can also help boost the public’s confidence in the vaccination. The media can provide valuable information for the public to know that the vaccine is safe. Almost everyone in the modern era lives with a cell phone now. People on social media can also share their experiences after getting vaccinated. Influences can help boost the public’s confidence. Just as voters would receive “I voted” after casting their ballots, vaccination distribution sites can provide “I got vaccinated” stickers. This can encourage individuals to post on the media that they have received the vaccine (Milkman, 2020). Furthermore, those who spread misleading information should be fined by the authorities. This punishment would be sufficient for them to learn their lesson. People who oversee data and information in social media should be concerned about the spread of misleading information on social media. After deleting the false information, they should put up a notice stating that is fake. This will help the public to understand which information should be trusted or not. Moreover, people who find misleading information online should report it to the administration. This could help prevent false info from circulating on the internet.

Recent studies showed that the contamination of land and water can also negatively affect the production of crops and the food systems as the safety of products can be compromised by the chemicals used by fracking. In addition, the amount of freshwater required for the mixture of the fracking fluids can generate a lack of water supply to the local agricultural industries. The fresh water is the 90-97 % of the fracking fluids, and the water deployed is not possible to recycle efficiently. In fact, the wastewater became a further challenge to the agricultural sector as it can make the soil dry and unusable for crops (Pothukuchi et al. 2018). The challenges faced by the agricultural sector are reflected in the farmlands and livestocks as well. For example, in Pennsylvania, the Dairy farming is one of the major agricultural sectors. This particular sector requires unpolluted water and pasturelands to enable the cows to produce milk. Since 1996 this sector began to fail, but the largest decrease in cows that produce milk took place between 2007 and 2011. It was the exact same period when the fracking industries reached their peak in this area (Pothukuchi et al. 2018). Another piece of evidence is related to the air pollution caused by fracking, specifically, the pollution of agricultural pollinators such as bees. The population of air caused by fracking has led to a huge degradation of that volatiles endangering the local and global food production. Those outcomes are closely related to the low level of planning abilities in rural areas, where fracking usually takes place. Particularly, the gap between fracking industry actors and local officials didn’t allow the development of a proper level of policies and regulations.

References:

Academic writing tip: Making an outline. (2020, December 8). The International Language Institute of Massachusetts. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://ili.edu/2020/12/08/academic-writing-tip-making-an-outline/

Caulfield, J. (2021, December 6). How to Write an Essay Outline | Guidelines & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/essay-outline/

Choudhary, A. (n.d.). Impressive Verbs to use in your Research Paper. Editage. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.editage.com/all-about-publication/research/impressive-Verbs-to-use-in-your-Research-Paper.html

Critical reading towards critical writing. (n.d.). University of Toronto. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/researching/critical-reading/

Critical writing. (n.d.). Teesside University. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://libguides.tees.ac.uk/ld.php?content_id=33286287

Critical writing. (n.d.-b). EAP FOUNDATION.COM. Https://www.eapfoundation.com/writing/critical/

Decide when to quote, paraphrase and summarize. (n.d.). University of Houston-Victoria. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.uhv.edu/curriculum-and-student-achievement/student-success/tutoring/student-resources/a-d/decide-when-to-quote-paraphrase-and-summarize/

Features of academic writing. (n.d.). UEFAP. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from http://www.uefap.com/writing/feature/hedge.htm

Five ways to introduce quotations. (n.d.). University of Georgia. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://dae.uga.edu/iep/handouts/Five-Ways-to-Introduce-Quotations.pdf

Jansen, D. (2017, April). Analytical writing vs descriptive writing. GRADCOACH. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://gradcoach.com/analytical-vs-descriptive-writing/

Hedges and Boosters. (n.d.). The Nature of Writing. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://natureofwriting.com/courses/introduction-to-rhetoric/lessons/hedges-and-boosters/topic/hedges-and-boosters

How to write critically. (n.d.). Teesside University. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://libguides.tees.ac.uk/ld.php?content_id=31275168

Lane, J. (2021, July 9). Critical thinking for critical writing. Simon Fraser University. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.lib.sfu.ca/about/branches-depts/slc/writing/argumentation/critical-thinking-writing

LibGuides: Critical Writing: Online study guide. (n.d.). Sheffield Hallam University. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://libguides.shu.ac.uk/criticalwriting

What are analytical verbs? (n.d.). Twinkl. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.twinkl.com/teaching-wiki/analytical-verbs

What is hedging in academic writing? (2022, May 3). Enago Academy. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.enago.com/academy/hedging-in-academic-writing/

Critical Reading, Writing, and Thinking Copyright © 2022 by Zhenjie Weng, Josh Burlile, Karen Macbeth is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academic Writing: Critical Thinking & Writing

- Academic Writing

- Planning your writing

- Structuring your assignment

- Critical Thinking & Writing

- Building an argument

- Reflective Writing

- Summarising, paraphrasing and quoting

Critical Thinking

One of the most important features of studying at university is the expectation that you will engage in thinking critically about your subject area.

Critical thinking involves asking meaningful questions concerning the information, ideas, beliefs, and arguments that you will encounter. It requires you to approach your studies with a curious, open mind, discard preconceptions, and interrogate received knowledge and established practices.

Critical thinking is key to successfully expressing your individuality as an independent learner and thinker in an academic context. It is also a valuable life skill.

Critical thinking enables you to:

- Evaluate information, its validity and significance in a particular context.

- Analyse and interpret evidence and data in response to a line of enquiry.

- Weigh-up alternative explanations and arguments.

- Develop your own evidence-based and well-reasoned arguments.

- Develop well-informed viewpoints.

- Formulate your own independent, justifiable ideas.

- Actively engage with the wider scholarship of your academic community.

Writing Critically

Being able to demonstrate and communicate critical thinking in your written assignments through critical writing is key to achieving academic success.

Critical writing can be distinguished from descriptive writing which is concerned with conveying information rather than interrogating information. Understanding the difference between these two styles of academic writing and when to use them is important.

The balance between descriptive writing and critical writing will vary depending on the nature of the assignment and the level of your studies. Some level of descriptive writing is generally necessary to support critical writing. More sophisticated criticality is generally required at higher levels of study with less descriptive content. You will continue to develop your critical writing skills as you progress through your course.

Descriptive Writing and Critical Writing

- Descriptive Writing

- Critical Writing

- Examples of Critical Writing

Descriptive writing demonstrates the knowledge you have of a subject, and your knowledge of what other people say about that subject. Descriptive writing often responds to questions framed as ‘what’ , ‘where’ , ‘who’ and ‘when’ .

Descriptive writing might include the following:

- Description of what something is or what it is about (an account, facts, observable features, details): a topic, problem, situation, or context of the subject under discussion.

- Description of where it takes place (setting and context), who is involved and when it occurs.

- Re-statement or summary of what others say about the topic.

- Background facts and information for a discussion.

Description usually comes before critical content so that the reader can understand the topic you are critically engaging with.

Critical writing requires you to apply interpretation, analysis, and evaluation to the descriptions you have provided. Critical writing often responds to questions framed as ‘how’ or ‘why’ . Often, critical writing will require you to build an argument which is supported by evidence.

Some indicators of critical writing are:

- Investigation of positive and negative perspectives on ideas

- Supporting ideas and arguments with evidence, which might include authoritative sources, data, statistics, research, theories, and quotations

- Balanced, unbiased appraisal of arguments and counterarguments/alternative viewpoints

- Honest recognition of the limitations of an argument and supporting evidence

- Plausible, rational, convincing, and well-reasoned conclusions

Critical writing might include the following:

- Applying an idea or theory to different situations or relate theory to practice. Does the idea work/not work in practice? Is there a factor that makes it work/not work? For example: 'Smith's (2008) theory on teamwork is effective in the workplace because it allows a diverse group of people with different skills to work effectively'.

- Justifying why a process or policy exists. For example: 'It was necessary for the nurse to check the patient's handover notes because...'

- Proposing an alternative approach to view and act on situations. For example: 'By adopting a Freirian approach, we could view the student as a collaborator in our teaching and learning'. Or: 'If we had followed the NMC guidelines we could have made the patient feel calm and relaxed during the consultation'.

- Discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of an idea/theory/policy. Why does this idea/theory/policy work? Or why does this idea not work? For example: 'Although Smith's (2008) theory on teamwork is useful for large teams, there are challenges in applying this theory to teams who work remotely'.

- Discussion of how the idea links to other ideas in the field (synthesis). For example: 'the user experience of parks can be greatly enhanced by examining Donnelly's (2009) customer service model used in retail’.

- Discussion of how the idea compares and contrasts with other ideas/theories. For example: ‘The approach advocated by the NMC differs in comparison because of factor A and factor C’.

- Discussion of the ‘’up-to-datedness” and relevance of an idea/theory/policy (its currency). For example: 'although this approach was successful in supporting the local community, Smith's model does not accommodate the needs of a modern global economy'.

- Evaluating an idea/theory/policy by providing evidence-informed judgment. For example: 'Therefore, May's delivery model should be discontinued as it has created significant issues for both customers and staff (Ransom, 2018)'.

- Creating new perspectives or arguments based on knowledge. For example: 'to create strong and efficient buildings, we will look to the designs provided by nature. The designs of the Sydney Opera House are based on the segments of an orange (Cook, 2019)'.

Further Reading

- << Previous: Structuring your assignment

- Next: Building an argument >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 3:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uos.ac.uk/academic-writing

➔ About the Library

➔ Meet the Team

➔ Customer Service Charter

➔ Library Policies & Regulations

➔ Privacy & Data Protection

Essential Links

➔ A-Z of eResources

➔ Frequently Asked Questions

➔Discover the Library

➔Referencing Help

➔ Print & Copy Services

➔ Service Updates

Library & Learning Services, University of Suffolk, Library Building, Long Street, Ipswich, IP4 1QJ

✉ Email Us: [email protected]

✆ Call Us: +44 (0)1473 3 38700

- I nfographics

- Show AWL words

- Subscribe to newsletter

- What is academic writing?

- Academic Style

- What is the writing process?

- Understanding the title

- Brainstorming

- Researching

- First draft

- Proofreading

- Report writing

- Compare & contrast

- Cause & effect

- Problem-solution

- Classification

- Essay structure

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Book review

- Research proposal

- Thesis/dissertation

- What is cohesion?

- Cohesion vs coherence

- Transition signals

- What are references?

- In-text citations

- Reference sections

- Reporting verbs

- Band descriptors

Show AWL words on this page.

Levels 1-5: grey Levels 6-10: orange

Show sorted lists of these words.

Any words you don't know? Look them up in the website's built-in dictionary .

Choose a dictionary . Wordnet OPTED both

Critical writing Analyse and evaluate information to develop an argument

In academic writing you will develop an argument or point of view. This will be supported by concrete evidence, in other words reasons, examples, and information from sources. The writing you produce in this way will need to be 'critical writing'. This section looks at critical writing in detail, first by giving a definition of critical writing and considering how to write critically , then by contrasting critical writing with descriptive writing , with some examples . There is also a discussion of how critical writing relates to Bloom's taxonomy of thinking skills , as well as a checklist to help you check critical writing in your own work.

What is critical writing?

Critical writing is writing which analyses and evaluates information, usually from multiple sources, in order to develop an argument. A mistake many beginning writers make is to assume that everything they read is true and that they should agree with it, since it has been published in an academic text or journal. Being part of the academic community, however, means that you should be critical of (i.e. question) what you read, looking for reasons why it should be accepted or rejected, for example by comparing it with what other writers say about the topic, or evaluating the research methods to see if they are adequate or whether they could be improved.

How to write critically

In order to write critically, you need to use a range of sources to develop your argument. You cannot rely solely on your own ideas; you need to understand what others have written about the same topic. Additionally, it is not enough to use just a single source to support your argument, for example a source which agrees with your own view, since this could lead to a biased argument. You need to consider all sides of the issue.

Further, in developing your argument, you need to analyse and evaluate the information from other sources. You cannot just string quotes together (A says this, B says that, C says something else), without looking more deeply at the information and building on it to support your own argument. This means you need to break down the information from other sources to determine how the parts relate to one another or to an overall structure or purpose [ analysing ], and then make judgements about it, identifying its strengths and weaknesses, and possibly 'grey areas' in between, which are neither strengths nor weaknesses [ evaluating ]. Critical reading skills will help you with this, as you consider whether the source is reliable, relevant, up-to-date, and accurate. For example, you might examine the research methods used in an experiment [ analysing ] in order to assess why they were chosen or to determine whether they were appropriate [ evaluating ], or you might deconstruct (break down) a writer's line of reasoning [ analysing ] to see if it is valid or whether there are any gaps [ evaluating ].

As a result of analysis and evaluation, you will be able to give reasons why the conclusions of different writers should be accepted or treated with caution . This will help you to build a clear line of reasoning which will lead up to your own conclusions, and you will be writing critically.

What is descriptive writing?

Critical writing is often contrasted with descriptive writing . Descriptive writing simply describes what something is like. Although you need a critical voice, description is still necessary in your writing, for example to:

- give the background of your research;

- state the theory;

- explain the methods of your experiment;

- give the biography of an important person;

- provide facts and figures about a particular issue;

- outline the history of an event.

You should, however, keep the amount of description to a minimum. Most assignments will have a strict word limit, and you should aim to maximise the amount of critical writing, while minimising the number of words used for description. If your tutors often write comments such as 'Too descriptive' or 'Too much theory' or 'More analysis needed', you know you need to adjust the balance.

Examples of descriptive vs. critical writing

The following table gives some examples to show the difference between descriptive and critical writing. The verbs in bold are key verbs according to Bloom's taxonomy , considered next.

Relationship to Bloom's Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy was developed in 1956 by Benjamin Bloom, an educational psychologist working at the University of Chicago. It classifies the thinking behaviours that are believed to be important in the processes of learning. It was developed in three domains, with the cognitive domain, i.e. the knowledge based domain, consisting of six levels. The taxonomy was revised in 2001 by Anderson and Krathwohl, to reflect more recent understanding of educational processes. Their revised taxonomy also consists of six levels, arranged in order from lower order thinking skills to higher order thinking skills, namely: remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating, and creating.

Bloom's revised taxonomy is relevant since analysing and evaluating , which form the basis of critical writing, are two of the higher order thinking skills in the taxonomy. Descriptive writing, by contrast, is the product of remembering and understanding , the two lowest order thinking skills. The fact that critical writing uses higher order thinking skills is one of the main reasons this kind of writing is expected at university.

The table below gives more details about each of the levels, including a description and some keys verbs associated with each level. Although the verbs are intended for the design of learning outcomes, they are nonetheless representative of the kind of work involved at each level, and are therefore relevant to academic writing.

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. Enter your email to receive a free sample from Academic Writing Genres .

Below is a checklist for critical writing. Use it to check your own writing, or get a peer (another student) to help you.

Academic Phrasebank , The University of Manchester (2020) Being Critical . Available at: http://www.phrasebank.manchester.ac.uk/being-critical/ (Accessed: 11 September, 2020).

Churches, A. (n.d.) Bloom’s Digital Taxonomy . Available at: https://edorigami.edublogs.org/blooms-digital-taxonomy/ (Accessed: 1 September, 2020).

Colorado College (n.d.) Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy . Available at: https://www.coloradocollege.edu/other/assessment/how-to-assess-learning/learning-outcomes/blooms-revised-taxonomy.html (Accessed: 1 September, 2020).

Cottrell, S. (2013) The Study Skills Handbook (4th ed.) . Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan

Shabatura, J. (2013) Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to Write Effective Learning Objectives . Available at: https://tips.uark.edu/using-blooms-taxonomy/ (Accessed: 1 September, 2020).

Sheffield Halam University (2020) Critical Writing . Available at: https://libguides.shu.ac.uk/criticalwriting (Accessed: 1 September, 2020).

Teesside University (2020). Critical Writing: Help . Available at: https://libguides.tees.ac.uk/critical_writing (Accessed: 11 September, 2020).

University of Hull (2020) Critical writing: Descriptive vs critical . Available at: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/criticalwriting/descriptive-critical (Accessed: 11 September, 2020).

University of Leicester (2009) What is critical writing . Available at: http://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/ld/resources/writing/writing-resources/critical-writing (Access date: 8/12/14).

Wilson, L.O. (2020) Bloom’s Taxonomy Revised . Available at: https://thesecondprinciple.com/essential-teaching-skills/blooms-taxonomy-revised/ (Accessed: 1 September, 2020).

Yale University (2017) Bloom’s Taxonomy . Available at: https://poorvucenter.yale.edu/BloomsTaxonomy (Accessed: 1 September, 2020).

Next section

Find out about research skills in the next section.

- Research skills

Previous section

Go back to the previous section about writing objectively .

- Objectivity

Author: Sheldon Smith ‖ Last modified: 06 January 2022.

Sheldon Smith is the founder and editor of EAPFoundation.com. He has been teaching English for Academic Purposes since 2004. Find out more about him in the about section and connect with him on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn .

Compare & contrast essays examine the similarities of two or more objects, and the differences.

Cause & effect essays consider the reasons (or causes) for something, then discuss the results (or effects).

Discussion essays require you to examine both sides of a situation and to conclude by saying which side you favour.

Problem-solution essays are a sub-type of SPSE essays (Situation, Problem, Solution, Evaluation).

Transition signals are useful in achieving good cohesion and coherence in your writing.

Reporting verbs are used to link your in-text citations to the information cited.

Critical writing: What is critical writing?

- Managing your reading

- Source reliability

- Critical reading

- Descriptive vs critical

- Deciding your position

- The overall argument

- Individual arguments

- Signposting

- Alternative viewpoints

- Critical thinking videos

Jump to content on this page:

“If we are uncritical we shall always find what we want: we shall look for, and find confirmations” Karl Popper, cited in: Critical Thinking (Tom Chatfield)

Critical writing needs critical thinking. While most of this guide focuses on critical writing, it is first important to consider what we mean by criticality at university. This is because critical writing is primarily a process of evidencing and articulating your critical thinking. As such, it is really important to get the 'thinking bit' of your studies right! If you are able to demonstrate criticality in your thinking, it will make critical writing easier.

Williams’ (2009:viii) introduces criticality at university as:

“being thoughtful, asking questions, not taking things you read (or hear) at face value. It means finding information and understanding different approaches and using them in your writing.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking requires you to carefully evaluate not just sources of information, but also the ideas within them and the arguments they develop. This is an essential part of being a student at university. You cannot simply believe everything you read or are told. For some people, this can feel uncomfortable as this requires you to critique published authors and notable academics. While this may feel inappropriate, it is one of the foundations of academic debate. Indeed, for any given topic or issue, there are many equally valid academic positions. To be effective in your critical thinking, you need to use both scepticism and objectivity :

Scepticism requires you to bring doubt and a questioning attitude to your academic work. In essence, you must ensure you do not automatically accept everything you hear, read or see as true (Chatfield, 2018). This requires you to question everything you hear, read or see . This is the first step towards developing a critical approach.

Objectivity

Objectivity requires you to approach your work with a more neutral perspective . While it is not possible to take yourself out of your work, when you are engaging in critical thinking you need to acknowledge anything that influences your perspective. This is very important as without this level of self-awareness you can focus more on your opinion than developing a reasoned argument.

Remember, you CAN criticise the experts - the University of Sussex make this point well here: Critical Thinking: Criticising the experts .

A short introduction to critical writing

Making your thinking more critical with questions

This page has so far demonstrated the importance of asking questions in all of your academic work and learning. Questions are the root of criticality. Questions engage you in active thought, requiring you to process what you are hearing, reading, seeing or experiencing against what you already know. All questions, however, are not as equally probing. Questions like 'what', 'when' and 'who' tend to be more descriptive in contrast to questions like 'how' or 'so what' which are much more critical .

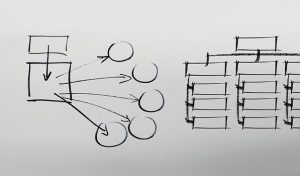

When engaging in critical thinking, you need to use a range of questions to fully consider the topic or issue you are trying to understand. Descriptive questions are great for developing your initial understanding, but you also need to consider more analytical and evaluatory questions to fully engage in critical thinking . The diagram below introduces some of the core critical questions:

Based on: University of Plymouth

Critical questions when reading

Most of your critical thinking should be directed towards your reading of the literature. This is because the literature forms the basis of all academic writing, serving as the evidence for whatever point(s) you are trying to make. Our Reading at University SkillsGuide contains some useful sections which apply criticality to determining source reliability and identifying an argument. Direct links to these can be found below:

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Managing your reading >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 10:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/criticalwriting

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

Dec. 5, 2019

Better writing assignments start with critical reading praxis.

Laying the Foundation: Graduate Student Projects in Teaching & Learning

In this blog feature, we present the work of Rice graduate students completing coursework in our Certificate in Teaching and Learning .

Today, we’re featuring the project of Mallory Pladus, a PhD Candidate in English at Rice. As part of her coursework in UNIV 501 “Research on Teaching and Learning,” Mallory pursued the research question “What types of reading and writing assignments promote critical literacy?” Based on her findings she compiled an annotated bibliography, wrote a synthesis of the research, and developed a research poster. We asked Mallory to share her findings and analysis through this blog post.

In the spring I conducted a research project with the CTE that began as an effort to learn more about writing assignments in undergraduate courses, specifically for English and writing-focused courses, but with an interest in assignments across disciplines as well. I approached the project from the vantage point of an instructor at a loss, remembering having puzzled over the question of what kind of writing work to assign when I had the chance to experiment with curriculum design as a first-time grad student instructor.

In that teaching experience, I wanted to take seriously the question of how my course could be evidence of a pedagogical cornerstone: to help student writers feel more confident in how their thinking comes through on the page. I thought a lot about the standard essay form, its strengths and weaknesses: it combines lessons on argumentation, literary evidence, and form; it’s (rotely?) institutionalized across disciplines. In the research I did last term, I was still less interested in deposing the essay, and more interested in researching answers to these two questions: What types of assignments help students arrive at a point where they can claim, with a feeling of authenticity, in this paper, I argue that… ? And what are the major principles in composition pedagogy that might help me and other instructors create more interesting and more effective assignments for students?

The findings were elucidating toward those ends. The field of composition pedagogy shows the positive influence of genre studies, which encourages instructors to make explicit the social function , the rhetorical situation , and the discourse community of the genres they’ve assigned.[1] Instructors who opt to not buck the traditional essay assignment, for example, should unpack with students who the essay is for, what conventions readers expect from it, and why the genre exists at all. I especially like the call to encourage students to write to a real or imagined community beyond the instructor. I remember valuing a version of this advice I received as an undergrad writer - to keep front and center the questions of who (is this for?) and why (write this at all?).

Above all, though, the standout lesson from the field - discussed as repetitiously as the content of the advice itself - is that student writers benefit most from writing early and often, through assignments that are sequenced, frequent, and recursive. I think most instructors know this, but could stand to be reminded. Effective assignments encompass opportunities for reflection, metacognition, and revision. They might call for post-script writing, for example; they might sequence an essay in staged parts; they might compel students to submit revisions after dialoguing with peers. In an article from The Chronicle of Higher Education by Doug Hesse, he summarily states the logic subtending all of these principles: “Students learn to write by writing.”[2]

For me, these conventional precepts - though helpful - omit one key term. Don’t students also learn to write by reading? One of my favorite things about teaching English is that part of the disciplinary groundwork is to attend carefully to language - to interpret texts as a series of decisions to a set of ends. For writing instruction, this helps. We impart to students the significance of these decisions, and we get to establish close engagement with language as a course norm. Hesse does acknowledge this aspect of successful writing classrooms too, as he notes that student writing benefits when students feel equipped to read texts as deep examples - not just of how to turn a phrase (though that too), but of carefully plotted rhetorical moves.

From experience, as a graduate fellow at Rice’s CAPC, I’m often reminded that my job to help a student improve a piece of writing comes down to making sure the student has really understood the assigned reading. When I think of common areas for improvement - an essay repeats key claims, doesn’t engage thoughtfully or confidently with source materials, lacks overall heft - they all tend to signal that a student’s first act in revision should be to return to the text. Through this work consulting on student essays, I’ve also learned that students frequently collapse the terms “critical” and “criticize”; when asked to “critique” an author’s argument, for example, students proceed to expose its flaws. These two observations suggest a need for and one potential barrier to implementing critical reading as part of our writing instruction. The pedagogy scholars, Robert Diyanni and Anton Borst, whose work I describe more below, define critical reading well: it is the capacity to “analyze a text, understand its logic, evaluate its evidence, interpret it creatively, and ask searching questions of it” (3).

Toward my first research question, about how to help students write with a greater feeling of authenticity, critical reading offers one answer. Before students can fill in the blanks that follow the template “ In this paper, I argue that …” they need to form a considered response to a source text, and this work begins with meaningful comprehension. Further, the language that Diyanni and Borst use to define critical reading resonates with this goal of authentic argumentation. As they highlight the abilities to “interpret [a text] creatively” and to “ask searching questions of it,” they describe the act of reading from a specific subject position. Course writing assignments (“ I will argue”) then allow students to develop ideas that began with reading.

My second research question pertained to the field of composition studies. In the research I conducted on writing assignments, I was surprised to not find more content on the relationship between critical reading and critical writing. There are, however, two notable exceptions to this point - one old, one new. In a study from 1990, Reading-to-Write: Exploring a Cognitive and Social Process , Linda Flower, et. al. explain that according to research in cognitive learning, the mind distinguishes between reading to do something and reading to learn something (6). When a person reads a set of instructions, for instance, they scan for usable content to extract. Conversely, the act of reading with a bent toward writing, “is guided by the need to produce a text of one’s own” (7).

In Critical Reading Across the Curriculum , DiYanni and Borst make a case for the significance of critical reading, with greater implications for pedagogy. They explain that CR entails two primary parts: to read responsibly (to accurately attend to a text) and to read responsively (to talk back to a text via marginalia and annotation). The contributor Pat C. Hoy argues that “We would do well to clarify for our students this entwining relationship, reminding them...that the most persuasive writing is predicated on acts of clear-headed critical reading” (25). Hoy offers the practical example of one such reading assignment as a precursor to writing: guide students to distill an essay; have them write one cogent sentence in the margin to capture the meaning of each paragraph.

Both Reading to Write and Critical Reading Across the Curriculum stress the importance of meeting a text on its own terms - of understanding its major moves and claims (as opposed to quickly mining it, and before beginning the work of critiquing it). Both provoke the need for instructors to prompt students to read better, with an eye toward writing. In addition to the example Hoy provides of the distillation assignment, instructors could experiment with reading journals, dialectical notebooks (that stage a conversation between the reader and the source text), and descriptive outlining (in which students unpack both what a text says and how it says it).[3] These examples attest to the overlaps between reading and writing assignments. Similarly, as we emphasize the importance of drafting, editing, and revising in the writing classroom, we can also emphasize active reading and active reading assignments as the first stage of the writing work we already know to teach as a process.

[1] From Dan Melzer’s Assignments Across the Curriculum: A National Study of College Writing (2014). For more on genre theory, see Mary Soliday’s Everyday Genres: Writing Assignments Across the Disciplines (2011).

[2] “We Know What Works in Teaching Composition” (2017).

[3] See Susan M. Leist, Writing to Teach; Writing to Learn in Higher Education (University Press of America, 2006), for a more detailed description of these and other assignments.

Posted on December 5, 2019 by Ania Kowalik

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Teachers: Creating Writing Assignments

This page contains four specific areas:

Creating Effective Assignments

Checking the assignment, sequencing writing assignments, selecting an effective writing assignment format.

Research has shown that the more detailed a writing assignment is, the better the student papers are in response to that assignment. Instructors can often help students write more effective papers by giving students written instructions about that assignment. Explicit descriptions of assignments on the syllabus or on an “assignment sheet” tend to produce the best results. These instructions might make explicit the process or steps necessary to complete the assignment. Assignment sheets should detail:

- the kind of writing expected

- the scope of acceptable subject matter

- the length requirements

- formatting requirements

- documentation format

- the amount and type of research expected (if any)

- the writer’s role

- deadlines for the first draft and its revision

Providing questions or needed data in the assignment helps students get started. For instance, some questions can suggest a mode of organization to the students. Other questions might suggest a procedure to follow. The questions posed should require that students assert a thesis.

The following areas should help you create effective writing assignments.

Examining your goals for the assignment

- How exactly does this assignment fit with the objectives of your course?

- Should this assignment relate only to the class and the texts for the class, or should it also relate to the world beyond the classroom?

- What do you want the students to learn or experience from this writing assignment?

- Should this assignment be an individual or a collaborative effort?

- What do you want students to show you in this assignment? To demonstrate mastery of concepts or texts? To demonstrate logical and critical thinking? To develop an original idea? To learn and demonstrate the procedures, practices, and tools of your field of study?

Defining the writing task

- Is the assignment sequenced so that students: (1) write a draft, (2) receive feedback (from you, fellow students, or staff members at the Writing and Communication Center), and (3) then revise it? Such a procedure has been proven to accomplish at least two goals: it improves the student’s writing and it discourages plagiarism.

- Does the assignment include so many sub-questions that students will be confused about the major issue they should examine? Can you give more guidance about what the paper’s main focus should be? Can you reduce the number of sub-questions?

- What is the purpose of the assignment (e.g., review knowledge already learned, find additional information, synthesize research, examine a new hypothesis)? Making the purpose(s) of the assignment explicit helps students write the kind of paper you want.

- What is the required form (e.g., expository essay, lab report, memo, business report)?

- What mode is required for the assignment (e.g., description, narration, analysis, persuasion, a combination of two or more of these)?

Defining the audience for the paper

- Can you define a hypothetical audience to help students determine which concepts to define and explain? When students write only to the instructor, they may assume that little, if anything, requires explanation. Defining the whole class as the intended audience will clarify this issue for students.

- What is the probable attitude of the intended readers toward the topic itself? Toward the student writer’s thesis? Toward the student writer?

- What is the probable educational and economic background of the intended readers?

Defining the writer’s role

- Can you make explicit what persona you wish the students to assume? For example, a very effective role for student writers is that of a “professional in training” who uses the assumptions, the perspective, and the conceptual tools of the discipline.

Defining your evaluative criteria

1. If possible, explain the relative weight in grading assigned to the quality of writing and the assignment’s content:

- depth of coverage

- organization

- critical thinking

- original thinking

- use of research

- logical demonstration

- appropriate mode of structure and analysis (e.g., comparison, argument)

- correct use of sources

- grammar and mechanics

- professional tone

- correct use of course-specific concepts and terms.

Here’s a checklist for writing assignments:

- Have you used explicit command words in your instructions (e.g., “compare and contrast” and “explain” are more explicit than “explore” or “consider”)? The more explicit the command words, the better chance the students will write the type of paper you wish.

- Does the assignment suggest a topic, thesis, and format? Should it?

- Have you told students the kind of audience they are addressing — the level of knowledge they can assume the readers have and your particular preferences (e.g., “avoid slang, use the first-person sparingly”)?

- If the assignment has several stages of completion, have you made the various deadlines clear? Is your policy on due dates clear?

- Have you presented the assignment in a manageable form? For instance, a 5-page assignment sheet for a 1-page paper may overwhelm students. Similarly, a 1-sentence assignment for a 25-page paper may offer insufficient guidance.

There are several benefits of sequencing writing assignments:

- Sequencing provides a sense of coherence for the course.

- This approach helps students see progress and purpose in their work rather than seeing the writing assignments as separate exercises.