- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- Relationships

- Homelessness

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Ukraine aid and a potential TikTok ban: What’s in the House’s new $95 billion bill

The Supreme Court doesn’t seem eager to get involved with homelessness policy

Drake vs. everyone, explained

On Earth Day, Vox Releases Home Planet, A Project Highlighting the Personal Dimensions of Climate Change in our Daily Lives

Do you need to worry about “forever chemicals”?

Donald Trump already won the only Supreme Court fight that mattered

What We’ve Learned About So-Called ‘Lockdowns’ and the COVID-19 Pandemic

By Lori Robertson

Posted on March 8, 2022

SciCheck Digest

Plenty of peer-reviewed studies have found government restrictions early in the pandemic, such as business closures and physical distancing measures, reduced COVID-19 cases and/or mortality, compared with what would have happened without those measures. But conservative news outlets and commentators have seized on a much-criticized, unpublished working paper that concluded “lockdowns” had only a small impact on mortality as definitive evidence the restrictions don’t work.

Multiple lines of evidence back the use of face masks to protect against the coronavirus, although some uncertainty remains as to how effective mask interventions are in preventing spread in the community.

Lab tests, for example, show that certain masks and N95 respirators can partially block exhaled respiratory droplets or aerosols, which are thought to be the primary ways the virus spreads.

Observational studies, while limited, have generally found mask-wearing to be associated with a reduced risk of contracting the virus or fewer COVID-19 cases in a community.

A few randomized controlled trials have found that providing free masks and encouraging people to wear them results in a small to moderate reduction in transmission, although these results have not always been statistically significant.

Masks should not be viewed as foolproof, as no mask is thought to offer complete protection to the wearer or to others. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that people wear the most protective mask that fits well and can be worn consistently. Loosely woven cloth masks are the least protective. Layered, tightly woven cloth masks offer more protection, while well-fitting surgical masks and KN95 respirators provide even more protection and N95 respirators are the most protective.

Link to this

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, as the virus spread around the globe, many countries implemented restrictions on movement and social gatherings in an effort to flatten the curve — or reduce sharp spikes in caseloads to avoid overwhelming health care facilities. Without vaccines or evidence-based treatments, these non-pharmaceutical interventions, or NPIs, were the only public health measures available for months to combat the pandemic.

There have been a lot of studies assessing whether and to what extent so-called “lockdowns” and various NPIs have been effective, and plenty of research that has concluded these measures can limit transmission, or reduce cases and deaths. For instance, a study published in Nature in June 2020 found that “major non-pharmaceutical interventions—and lockdowns in particular—have had a large effect on reducing transmission” in 11 European countries. It estimated what would have happened if the transmission of the virus hadn’t been reduced, finding that 3.1 million deaths “have been averted owing to interventions since the beginning of the epidemic.” The estimate doesn’t account for behavior changes or the impact of overwhelmed health systems.

In May 2020, the same journal published a study that estimated the number of cases in mainland China would have been “67-fold higher” by the end of February 2020 without a combination of non-pharmaceutical interventions.

But one working paper posted online in January — and not peer-reviewed — has gotten a lot of attention in conservative circles for its conclusion that “lockdowns have had little to no effect on COVID-19 mortality.” The paper, which is an analysis of other studies, has been touted as a “Johns Hopkins University study,” but it’s not a product of the university’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, whose vice dean — among other public health experts — has criticized the paper.

“The working paper is not a peer-reviewed scientific study,” Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, vice dean of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said in a Feb. 8 statement sent to us in an email. “To reach their conclusion that ‘lockdowns’ had a small effect on mortality, the authors redefined the term ‘lockdown’ and disregarded many peer-reviewed studies. The working paper did not include new data, and serious questions have already been raised about its methodology.”

Sharfstein said that early on “when so little was known about COVID-19, stay-at-home policies kept the virus from infecting people and saved many lives. Thankfully, these policies are no longer needed, as a result of vaccines, masks, testing, and other tools that protect against life-threatening COVID-19 infections.”

The authors of the working paper are economists: Steve H. Hanke , a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute and founder and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise; Jonas Herby , a special adviser at the Center for Political Studies in Copenhagen, Denmark; and Lars Jonung , a professor emeritus at Sweden’s Lund University.

Fox News published a Feb. 4 story questioning why other mainstream media outlets hadn’t written stories about the working paper, saying there had been “a full-on media blackout,” and “Fox & Friends” co-host Brian Kilmeade asked in a Facebook post , “Will some people get an apology after this?” On Feb. 21, former Republican vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin posted a video to Facebook highlighting the working paper and asking if lockdowns were about “power,” not “safety.”

But the non-peer-reviewed paper isn’t the definitive or final word on lockdowns, and the attention it has received has, in turn, sparked criticism of the paper’s analysis.

Criticisms of the Working Paper

The working paper was a literature review and meta-analysis , meaning it searched the available scientific literature and identified studies that met certain criteria, and then combined similar studies statistically to reach a conclusion. It identified 24 papers, published or posted as of early July 2021, that met its criteria for the meta-analysis — 17 of which were peer-reviewed. Among the criticisms: The paper excluded many relevant studies, broadly defined “lockdown,” and overwhelmingly based one of its headline figures on a study whose conclusions it rejected. That study also didn’t estimate the delayed effect of government restrictions on death rates a few weeks later, according to experts we consulted. Instead, it only assessed the effect of current death rates on current policies.

Excluded research. One of the criticisms is that the working paper excluded a lot of relevant research. The paper said it considered “difference-in-difference” studies, which would compare outcomes in areas or populations that were subject to a restriction with those that were not, and limited its analysis to the impact on mortality. The paper excluded studies that use modeling on mortality, that compare before and after a “lockdown” and that consider the timing of restrictions. Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz , an epidemiologist working on his Ph.D. at the University of Wollongong in Australia, said in a long Twitter thread: “Many of the most robust papers on the impact of lockdowns are, by definition, excluded.”

He called the working paper “a very weak review that doesn’t really show much, if anything.” It excluded “modelled counterfactuals,” which would compare what happened with what would have happened without the intervention. “Because this is the most common method used in infectious disease assessments, this has the practical impact of excluding most epidemiological research from the review,” Meyerowitz-Katz said.

Hanke told us: “Models are fine if they are based on empirical observations,” meaning from experience, “rather than assumptions. In those circumstances, models are able to reliably forecast the real world. But the models used during the pandemic have been inaccurate, as they, for the most part, have not been based on empirical observations but assumptions,” he said in an email. “A prime example of modelers gone astray is the Imperial College London study of March 16, 2020.”

That March 2020 report , early in the pandemic, estimated that 2.2 million lives would be lost in the U.S. in “the (unlikely) absence of any control measures or spontaneous changes in individual behaviour.” As we’ve written before , it wasn’t intended to be a practical estimate, as doing absolutely nothing was, in the author’s words, “unlikely.”

One of the authors of that report has been critical of Hanke’s working paper. Neil Ferguson, director of the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, Jameel Institute, Imperial College London, said in a statement that the working paper “does not significantly advance our understanding of the relative effectiveness of the plethora of public health measures adopted by different countries to limit COVID-19 transmission.”

Ferguson said that NPIs “are intended to reduce contact rates between individuals in a population, so their primary impact, if effective, is on transmission rates. Impacts on hospitalisation and mortality are delayed, in some cases by several weeks. In addition, such measures were generally introduced (or intensified) during periods where governments saw rapidly growing hospitalisations and deaths. Hence mortality immediately following the introduction of lockdowns is generally substantially higher than before. Neither is lockdown a single event as some of the studies feeding into this meta-analysis assume; the duration of the intervention needs to be accounted for when assessing its impact.”

Ferguson said because NPIs affect transmission rates, “the appropriate outcome measures to consider are growth rates (of cases or deaths) over time, with appropriate time lags – not total cases or deaths.”

Definition of “lockdown.” The working paper also had a very broad definition of “lockdown”: “Lockdowns are defined as the imposition of at least one compulsory, non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI),” it said. “NPIs are any government mandate that directly restrict peoples’ possibilities, such as policies that limit internal movement, close schools and businesses, and ban international travel.”

The paper did not examine the impact of voluntary behavior or recommendations, as opposed to mandates. “Our definition does not include governmental recommendations, governmental information campaigns, access to mass testing, voluntary social distancing, etc., but do include mandated interventions such as closing schools or businesses, mandated face masks etc.”

The paper then divided the 24 studies it considered into three groups: studies using a stringency index for restrictions, studies on shelter-in-place orders and those looking at specific NPIs. The last category included 11 studies on various measures, including face mask policies and limits on gatherings.

Stringency index studies. The authors examined seven studies on the impact of more severe restrictions, calculating from those studies that, compared with a policy of recommendations, “lockdowns in Europe and the United States only reduced COVID-19 mortality by 0.2% on average” — the figure that conservatives have cited . But six of the seven studies concluded that lockdown policies helped reduce mortality, and the 0.2% figure is overwhelmingly based on one study that mistakenly estimated the wrong effect, according to economists we consulted.

The studies in this group used the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker , which looked at government responses worldwide to the pandemic and created a stringency index, measuring how strict the measures were over time. The index is from 0 to 100, with 100 being the most stringent restrictions. For instance, the OxCGRT heat map shows that many countries around the world had stringency levels above 70 in April 2020.

The working paper calculates mortality impact estimates for each of the seven studies aiming to show the effect of the average mandated restrictions in Europe and the United States early in the pandemic compared with a policy of only recommendations. The paper then calculates a weighted average, giving more weight to studies that said their findings were more precise. Nearly all of the weight — 91.8% — goes to one study, even though the working paper rejects the conclusions of that study.

That study — coauthored by Carolyn Chisadza , a senior lecturer in economics at the University of Pretoria, and published on March 10, 2021, in the journal Sustainability — looked at a sample of countries between March and September 2020 and concluded: “Less stringent interventions increase the number of deaths, whereas more severe responses to the pandemic can lower fatalities.”

The working paper claims the researchers’ conclusion is incorrect — but it uses the study’s estimates, saying the figures show an increase in mortality due to “lockdowns.”

Chisadza told us in an email that the study showed: “Stricter lockdowns will reduce the rate of deaths than would have occurred without lockdown or too lenient of restrictions.” But Hanke said the data from Chisadza and her colleagues only show that “stricter lockdowns will reduce mortality” relative to “the worst possible lockdown,” meaning a more lenient lockdown that, under the study, was associated with the highest rate of deaths.

We reached out to a third party about this disagreement. Victor Chernozhukov , a professor in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Economics and the Statistics and Data Science Center, along with Professor Hiroyuki Kasahara and Associate Professor Paul Schrimpf , both with the Vancouver School of Economics at the University of British Columbia — the authors of another study that was included in the working paper — looked at the Chisadza study and provided FactCheck.org with a peer review of it . They found the Chisadza study only measured the correlation between current death growth rates and current policies. It did not show the lagged effect of more stringent policies, implemented three weeks prior, on current death growth rates, which is what one would want to look at to evaluate the effectiveness of “lockdowns.”

In an email and in a phone interview, Chernozhukov told us the Chisadza study made an “honest mistake.” He said the working paper is “deeply flawed” partly because it relies heavily on a study that “estimates the wrong effect very precisely.”

In their review, Chernozhukov, Kasahara and Schrimpf write that the Chisadza et al. study “should be interpreted as saying that the countries currently experiencing high death rates (or death growth rates) are more likely to implement more stringent current policy. That is the only conclusion we can draw from [the study], because the current policy can not possibly influence the current deaths,” given the several weeks of delay between new infections and deaths.

The effect that should be examined for the meta-analysis is “the effect of the previous (e.g., 3 week lagged) policy stringency index on the current death growth rates.”

Chernozhukov, Kasahara and Schrimpf conducted a “quick reanalysis of similar data” to the Chisadza study, finding results that “suggest that more stringent policies in the past predict lower death growth rates.” Chernozhukov said much more analysis would be needed to further characterize this effect, but that it is “actually quite substantial.”

If the Chisadza study were removed from the working paper, according to one of the paper’s footnotes, the result would be a weighted average reduction in mortality of 3.5%, which Hanke said doesn’t change the “overall conclusions.” He said it “simply demonstrates the obvious fact that the conclusions contained in our meta-analysis are robust.”

But experts have pointed out other issues with the meta-analysis. Chernozhukov also said the paper “excluded a whole bunch of studies,” including synthetic control method studies, which evaluate treatment effects. He also questioned the utility of looking at a policy index that considers the U.S. as a whole, lumping all the states together. He said the meta-analysis is “not credible at all.”

Among the other six stringency index studies included in the meta-analysis, only one concluded that its findings suggested “lockdowns” had zero effect on mortality. In a review of 24 European countries’ weekly mortality rates for the first six months of 2017-2020, the study, published in CESifo Economic Studies , found “no clear association between lockdown policies and mortality development.” The author and Herby , one of the authors of the working paper, have written for the American Institute for Economic Research , which facilitated the controversial Great Barrington Declaration , an October 2020 statement advocating those at low risk of dying from COVID-19 “live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection,” while those at “highest risk” are protected.

The other studies found lockdown policies helped COVID-19 health outcomes. For instance, a CDC study published in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in January 2021, on the experience of 37 European countries from Jan. 23 to June 30, 2020, concluded that “countries that implemented more stringent mitigation policies earlier in their outbreak response tended to report fewer COVID-19 deaths through the end of June 2020. These countries might have saved several thousand lives relative to countries that implemented similar policies, but later.”

A working paper from Harvard University’s Center for International Development , which looked at 152 countries from the beginning of the pandemic until Dec. 31, 2020, found that “lockdowns tend to significantly reduce the spread of the virus and the number of related deaths.” But the effect fades over time, so lengthy (after four months) or second-phase “lockdowns” don’t have the same impact.

A study published in World Medical & Health Policy in November 2020 — that looked at whether 24 European countries responded quickly enough — found that the fluctuating containment measures, from country to country and over time, “prohibited a clear association with the mortality rate.” But it said “the implementation speed of these containment measures in response to the coronavirus had a strong effect on the successful mitigation of fatalities.”

Many studies found restrictions worked. Meyerowitz-Katz noted that the working paper authors disagreed with the conclusions of other studies included in the review, pointing to one included in the group of shelter-in-place orders. Meyerowitz-Katz said that study “found that significant restrictions were effective, but is included in this review as estimating a 13.1% INCREASE in fatalities.”

That study, by Yale School of Management researchers, published by The Review of Financial Studies in June 2021 , developed “a time-series database” on several types of restrictions for every U.S. county from March to December 2020. The authors concluded: “We find strong evidence consistent with the idea that employee mask policies, mask mandates for the general population, restaurant and bar closures, gym closures, and high-risk business closures reduce future fatality growth. Other business restrictions, such as second-round closures of low- to medium-risk businesses and personal care/spa services, did not generate consistent evidence of lowered fatality growth and may have been counterproductive.” The authors said the study’s “findings lie somewhere in the middle of the existing results on how NPIs influenced the spread of COVID-19.”

In terms of hard figures on fatality reductions, the study said the estimates suggest a county with a mandatory mask policy would see 15.3% fewer new deaths per 10,000 residents on average six weeks later, compared with a county without a mandatory mask policy. The impact for restaurant closures would be a decrease of 36.4%. But the estimates suggest other measures, including limits on gatherings of 100 people or more, appeared to increase deaths. The authors said one possible explanation of such effects could be that the public is substituting other activities that actually increase transmission of the virus — such as hosting weddings with 99 people in attendance, just under the 100-person limitation.

Another study in the shelter-in-place group is the study by Chernozhukov, Kasahara and Schrimpf, published in the Journal of Econometrics in January 2021 . It looked at the policies in U.S. states and found that “nationally mandating face masks for employees early in the pandemic … could have led to as much as 19 to 47 percent less deaths nationally by the end of May, which roughly translates into 19 to 47 thousand saved lives.” It found cases would have been 6% to 63% higher without stay-at-home orders and found “considerable uncertainty” over the impact of closing schools. It also found “substantial declines in growth rates are attributable to private behavioral response, but policies played an important role as well.”

The working paper considered 13 studies that evaluated stay-in-place orders, either alone or in combination with other NPIs. The estimated effect on total fatalities for each study calculated by the authors varied quite widely, from a decrease of 40.8% to an increase of 13.1% (the study above mentioned by Meyerowitz-Katz). The authors then combined the studies into a weighted average showing a 2.9% decrease in mortality from these studies on shelter-in-place orders.

Sizable impact from some NPIs. The working paper actually found a sizable decrease in deaths related to closing nonessential businesses: a 10.6% weighted average reduction in mortality. The authors said this “is likely to be related to the closure of bars.” It also calculated a 21.2% weighted average reduction in deaths due to mask requirements, but notes “this conclusion is based on only two studies.”

As with the shelter-in-place group, the calculated effects in the specific NPIs group varied widely – from a 50% reduction in mortality due to business closures to a 36% increase due to border closures. The paper said “differences in the choice of NPIs and in the number of NPIs make it challenging to create an overview of the results.”

“The review itself does refer to other papers that reported that the lockdowns had a significant impact in preventing deaths,” Dr. Lee Riley , chair of the Division of Infectious Disease and Vaccinology at the University of California, Berkeley School of Public Health, told us when we asked for his thoughts on the working paper. “The pandemic has now been occurring long enough that it’s not surprising to begin to see many more reports that now contradict each other. As we all know, the US and Europe went through several periods when they relaxed their lockdowns, which was followed by a resurgence of the cases.”

Riley said that “many of the studies that this review included may suffer from the classic ‘chicken-or-egg’ bias. Whenever there was an increase in cases of deaths, lockdowns got instituted so it’s not surprising that some of the studies showed no impact of the lockdowns. If there was no surge of cases or deaths, most places in the US did not impose restrictions.”

Meyerowitz-Katz noted on Twitter that “the impact of ‘lockdowns’ is very hard to assess, if for no other reason than we have no good definition of ‘lockdown’ in the first place. … In most cases, it seems the authors have taken estimates for stay-at-home orders as their practical definition of ‘lockdown’ (this is pretty common) And honestly, I’d agree that the evidence for marginal benefit from stay-at-home orders once you’ve already implemented dozens of restrictions is probably quite weak.”

But, “if we consider ‘lockdown’ to be any compulsory restriction at all, the reality is that virtually all research shows a (short-term) mortality benefit from at least some restrictions.”

Additional Studies

We’ve already mentioned two studies beyond those in the working paper: the Nature June 2020 study by Imperial College London researchers that estimated interventions in 11 countries in Europe in the first few months of the pandemic reduced transmission and averted 3.1 million deaths; and the Nature May 2020 study that estimated cases in mainland China would have been 67-fold greater without several NPIs by the end of February.

There are many more that aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of various mitigation strategies, not included in the working paper’s analysis.

- A 2020 unpublished observational study — cited in the working paper as the basis for the Oxford stringency index but not included in the analysis — found that more stringent restrictions implemented more quickly led to fewer deaths. “A lower degree of government stringency and slower response times were associated with more deaths from COVID-19. These findings highlight the importance of non-pharmaceutical responses to COVID-19 as more robust testing, treatment, and vaccination measures are developed.” In considering nine NPIs, the authors said the average daily growth rates in deaths were affected by each additional stringency index point and each day that a country delayed reaching an index of 40 on the stringency scale. “These daily differences in growth rates lead to large cumulative differences in total deaths. For example, a week delay in enacting policy measures to [a stringency index of 40] would lead to 1.7 times as many deaths overall,” they wrote.

- A more up-to-date study by many of the same authors, posted July 9, 2021, by the journal Plos One, looked at data for 186 countries from Jan. 1, 2020, to March 11, 2021, a period over which 10 countries experienced three waves of the pandemic. In the first wave in those countries, 10 additional points on the stringency index — in other words more stringent restrictions — “resulted in lower average daily deaths by 21 percentage points” and by 28 percentage points in the third wave. “Moreover, interaction effects show that government policies were effective in reducing deaths in all waves in all groups of countries,” the authors said.

- A Dec. 15, 2020, study in Science used data from 41 countries to model which NPIs were most effective at reducing transmission. “Limiting gatherings to fewer than 10 people, closing high-exposure businesses, and closing schools and universities were each more effective than stay-at-home orders, which were of modest effect in slowing transmission,” the authors said. “When these interventions were already in place, issuing a stay-at-home order had only a small additional effect. These results indicate that, by using effective interventions, some countries could control the epidemic while avoiding stay-at-home orders.” The study, like many others, looked at the impact on the reproduction number of SARS-CoV-2, or the average number of people each person with COVID-19 infects at a given time. It notes that a reduction in this number would affect COVID-19 mortality, and that the impact of NPIs can depend on other factors, including when and for how long they are implemented, and how much the public adhered to them.

- A study in Nature Human Behaviour on Nov. 16, 2020 , considered the impact on the reproduction number of COVID-19 by 6,068 NPIs in 79 territories, finding that a combination of less intrusive measures could be as effective as a national lockdown. “The most effective NPIs include curfews, lockdowns and closing and restricting places where people gather in smaller or large numbers for an extended period of time. This includes small gathering cancellations (closures of shops, restaurants, gatherings of 50 persons or fewer, mandatory home working and so on) and closure of educational institutions.” The authors said this doesn’t mean an early national lockdown isn’t effective in reducing transmission but that “a suitable combination (sequence and time of implementation) of a smaller package of such measures can substitute for a full lockdown in terms of effectiveness, while reducing adverse impacts on society, the economy, the humanitarian response system and the environment.” They found that “risk-communication strategies” were highly effective, meaning government education and communication efforts that would encourage voluntary behavior. “Surprisingly, communicating on the importance of social distancing has been only marginally less effective than imposing distancing measures by law.”

- Another study in Nature in June 2020 looked at 1,700 NPIs in six countries, including the United States. “We estimate that across these 6 countries, interventions prevented or delayed on the order of 61 million confirmed cases, corresponding to averting approximately 495 million total infections,” the authors concluded. “Without these policies employed, we would have lived through a very different April and May” in 2020, Solomon Hsiang, the lead researcher and director of the Global Policy Laboratory at the University of California at Berkeley, told reporters . The study didn’t estimate how many lives were saved, but Hsiang said the benefits of the lockdown are in a sense invisible because they reflect “infections that never occurred and deaths that did not happen.”

- A more recently published study in Nature Communications in October , by U.K. and European researchers, found that closures of businesses and educational institutions, as well as gathering bans, reduced transmission during the second wave of COVID-19 in Europe — but by less than in the first wave. “This difference is likely due to organisational safety measures and individual protective behaviours—such as distancing—which made various areas of public life safer and thereby reduced the effect of closing them,” the authors said. The 17 NPIs considered by the study led to median reductions in the reproduction number of 77% to 82% in the first wave and 66% in the second wave.

- A February 2021 study in Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science estimated large reductions in infections (by 72%) and deaths (by 76%) in New York City in 2020, based on numerical experiments in a model. “Among all the NPIs, social distancing for the entire population and protection for the elderly in public facilities is the most effective control measure in reducing severe infections and deceased cases. School closure policy may not work as effectively as one might expect in terms of reducing the number of deceased cases,” the authors said.

Near the end of his lengthy Twitter thread on the working paper, Meyerowitz-Katz said he agrees that “a lot of people originally underestimated the impact of voluntary behaviour change on COVID-19 death rates – it’s probably not wrong to argue that lockdowns weren’t as effective as we initially thought.” He pointed to the Nature Communications study mentioned above, showing less of an impact from NPIs in a second wave of COVID-19 and positing individual safety behaviors were playing more of a role in that second wave.

“HOWEVER, this runs both ways,” Meyerowitz-Katz said. “[I]t is also quite likely that lockdowns did not have the NEGATIVE impact most people propose, because some behaviour changes were voluntary!”

He and others examined whether lockdowns were more harmful than the pandemic itself in a 2021 commentary piece in BMJ Global Health . They concluded that “government interventions, even more restrictive ones such as stay-at-home orders, are beneficial in some circumstances and unlikely to be causing harms more extreme than the pandemic itself.” Analyzing excess mortality suggested that “ lockdowns are not associated with large numbers of deaths in places that avoided large COVID-19 epidemics,” such as Australia and New Zealand, they wrote.

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s COVID-19/Vaccination Project is made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over FactCheck.org’s editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation. The goal of the project is to increase exposure to accurate information about COVID-19 and vaccines, while decreasing the impact of misinformation.

Herby, Jonas et al. “ A Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Lockdowns on COVID-19 Mortality .” Studies in Applied Economics, Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise, Johns Hopkins University. posted Jan 2022.

World Health Organization. “ Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Herd immunity, lockdowns and COVID-19 .” 31 Dec 2020.

Flaxman, Seth et al. “ Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe .” Nature. 584 (2020).

Lai, Shengjie et al. “ Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China .” Nature. 585 (2020).

Sharfstein, Joshua, vice dean of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Statement emailed to FactCheck.org. 8 Feb 2022.

Best, Paul. “ Lockdowns only reduced COVID-19 death rate by .2%, study finds: ‘Lockdowns should be rejected out of hand .'” Fox News. 1 Feb 2022.

Meyerowitz-Katz, Gideon. @GidMK. “ This paper has been doing the rounds, claiming that lockdown was useless (the source of the 0.2% effect of lockdown claim). Dozens of people have asked my opinion of it, so here we go: In my opinion, it is a very weak review that doesn’t really show much, if anything 1/n .” Twitter.com. 4 Feb 2022.

Hanke, Steve H., founder and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise. Email interview with FactCheck.org. 18 Feb 2022.

Ferguson, Neil, director of the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, Jameel Institute, Imperial College London. Statement posted by Science Media Centre . 3 Feb 2022.

Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker . Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. https://covidtracker.bsg.ox.ac.uk/. website accessed 20 Feb 2022.

Chisadza, Carolyn, senior lecturer in economics at the University of Pretoria. Email interview with FactCheck.org. 15 Feb 2022.

Clance, Matthew, associate professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Pretoria. Email interview with FactCheck.org. 16 Feb 2022.

Our World in Data. Cumulative confirmed COVID-19 deaths . website accessed 22 Feb 2022.

Bjornskov, Christian. “ Did Lockdown Work? An Economist’s Cross-Country Comparison .” CESifo Economic Studies. 67.3 (2021).

Fuller, James A. et al. “ Mitigation Policies and COVID-19–Associated Mortality — 37 European Countries, January 23–June 30, 2020 .” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 70.2 (2021).

Goldstein, P. et al. “ Lockdown Fatigue: The Diminishing Effects of Quarantines on the Spread of COVID-19 .” Harvard University Center for International Development. 2021.

Stockenhuber, Reinhold. “ Did We Respond Quickly Enough? How Policy-Implementation Speed in Response to COVID-19 Affects the Number of Fatal Cases in Europe .” World Medical & Health Policy. 12.4 (2020).

Riley, Lee, chair of the Division of Infectious Disease and Vaccinology at the University of California, Berkeley School of Public Health. Email interview with FactCheck.org. 14 Feb 2022.

Spiegel, Matthew and Heather Tookes. “ Business Restrictions and COVID-19 Fatalities .” The Review of Financial Studies. 34.11 (2021).

Chernozhukov, Victor et al. “ Causal impact of masks, policies, behavior on early covid-19 pandemic in the U.S. ” Journal of Econometrics. 220. 1 (2021).

Hale, Thomas et al. “ Global Assessment of the Relationship between Government Response Measures and COVID-19 Deaths .” medrxiv.org. 6 Jul 2020.

Hale, Thomas et al. “ Government responses and COVID-19 deaths: Global evidence across multiple pandemic waves .” Plos One. 9 Jul 2021.

Brauner, Jan M. et al. “ Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19 .” Science. 371.6531 (2020).

Haug, Mils et al. “ Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions .” Nature Human Behaviour. 4 (2020).

Sharma, Mrinank et al. “ Understanding the effectiveness of government interventions against the resurgence of COVID-19 in Europe .” Nature Communications. 12 (2021).

Yang, Jiannan et al. “ The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on the prevention and control of COVID-19 in New York City .” Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science. 31.2 (2021).

Achenbach, Joel and Laura Meckler. “ Shutdowns prevented 60 million coronavirus infections in the U.S., study finds .” Washington Post. 8 Jun 2020.

Hsiang, Solomon et al. “ The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic .” Nature. 584 (2020).

Chernozhukov, Victor et al. “ Comments on the ‘John Hopkins’ Meta Study (Herby et al., 2022) and Chisadza et al. (2021) .” Provided to FactCheck.org. 4 Mar 2022.

Chernozhukov, Victor, professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Economics and the Statistics and Data Science Center. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. 8 Mar 2022.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

How did the covid-19 lockdown affect children and adolescent's well-being: spanish parents, children, and adolescents respond.

- 1 ISGlobal, Hospital Clínic—Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 2 Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 3 Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, BarcelonaTech, Barcelona, Spain

- 4 B2SLab, Departament d'Enginyeria de Sistemes, Automàtica i Informàtica Industrial, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

- 5 Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça, Maputo, Mozambique

- 6 Networking Biomedical Research Centre in the Subject Area of Bioengineering, Biomaterials and Nanomedicine (CIBER-BBN), Madrid, Spain

- 7 Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain

- 8 Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 9 Consorcio de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Epidemiología y Salud Pública, Madrid, Spain

- 10 Department of Medicine, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

- 11 Molecular Microbiology Department, Hospital Sant Joan de Deu, Esplugues, Barcelona, Spain

- 12 BCNatal Fetal Medicine Research Center (Hospital Clínic and Hospital Sant Joan de Déu), University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 13 Institut d'Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer, Barcelona, Spain

- 14 Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology Department, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain

- 15 Pediatrics Department, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 16 ICREA, Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies, Barcelona, Spain

Background: During the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown strategies have been widely used to contain SARS-CoV-2 virus spread. Children and adolescents are especially vulnerable to suffering psychological effects as result of such measures. In Spain, children were enforced to a strict home lockdown for 42 days during the first wave. Here, we studied the effects of lockdown in children and adolescents through an online questionnaire.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in Spain using an open online survey from July (after the lockdown resulting from the first pandemic wave) to November 2020 (second wave). We included families with children under 16 years-old living in Spain. Parents answered a survey regarding the lockdown effects on their children and were instructed to invite their children from 7 to 16 years-old (mandatory scholar age in Spain) to respond a specific set of questions. Answers were collected through an application programming interface system, and data analysis was performed using R.

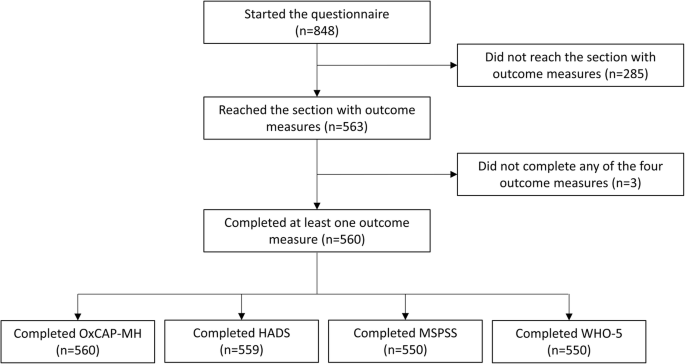

Results: We included 1,957 families who completed the questionnaires, covering a total of 3,347 children. The specific children's questionnaire was completed by 167 kids (7–11 years-old), and 100 adolescents (12–16 years-old). Children, in general, showed high resilience and capability to adapt to new situations. Sleeping problems were reported in more than half of the children (54%) and adolescents (59%), and these were strongly associated with less time doing sports and spending more than 5 h per day using electronic devices. Parents perceived their children to gain weight (41%), be more irritable and anxious (63%) and sadder (46%). Parents and children differed significantly when evaluating children's sleeping disturbances.

Conclusions: Enforced lockdown measures and isolation can have a negative impact on children and adolescent's mental health and well-being. In future waves of the current pandemic, or in the light of potential epidemics of new emerging infections, lockdown measures targeting children, and adolescents should be reconsidered taking into account their infectiousness potential and their age-specific needs, especially to facilitate physical activity and to limit time spent on electronic devices.

Nearly 80–90% of school-age youth could not physically attend school in more than 160 countries during the first wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic ( 1 , 2 ). In Spain, one of the first measures implemented when cases started increasing was to close all schools and impose a strict home confinement. During the first period of the lockdown (March 14th–April 27th of 2020), referred as “strict lockdown” hereinafter, only essential activities were allowed, and children were compelled to stay home except for emergency situations. From April 28th to June 21st, children were progressively allowed to leave the household in a very controlled manner and for a limited period (i.e., 1 h per day with no close interactions), during what became referred as the “relaxed lockdown.” Schools remained closed and pupils attended online lectures whenever possible. Children did not return to face-to-face learning until September 2020. Home confinement measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which were particularly stringent for children, may have had deleterious effects on the physical and mental health of this particularly vulnerable age group ( 3 , 4 ). Herein, we aimed to understand the perceived impact of lockdown measures on the mental health and well-being of minors, as reported by parents, but also adolescents and children themselves. We focused on risk perception and attitudes toward lockdown, perceptions of schooling, emotional responses, changes in biorhythms, psychical activity, sleep and eating attitudes, and screen time.

Study Design

We performed a cross-sectional study using convenience sampling through an online survey, launched in July 2020 and available until November 2020. The study was promoted via social media and the landing page of the Kids Corona Project. The questionnaire (see Supplementary Material ) was created by a team of pediatricians at Hospital Sant Joan de Déu of Barcelona, Spain, and was available in Spanish or Catalan (the two official languages in Catalonia). Questions specifically referred to the strict lockdown but also enquired about feelings/perceptions at the moment of survey completion (which was after the lockdown). To avoid collecting disturbances present before lockdown, we asked about “new problems detected during lockdown.” Most questions had yes/no as possible answers, but some asked respondents to choose between few closed answers or grade a perception on a scale from 0 (minimum) to 10 (maximum). Families living in Spain with children under 16 years of age were invited to participate and to answer questions regarding COVID-19 and the physical, mental health and wellbeing of children during lockdown. Parents answered the survey regarding their children (0–16 years). Those children old enough to read and answer the questionnaire themselves, and who were in the age group for which there is mandatory schooling (>6–<16 years of age), were invited to answer the survey. Children aged 7–11 years were instructed to do it with caregivers' support, and adolescents over 11 years old were instructed to do it on their own.

Data Collection

The answers to these surveys were collected through an API system using a custom code written in Python ( 5 ). Selection criteria for household enrollment were (i) accepted informed consent, (ii) respondent aged 18 years old or more, (iii) one or more children under 16 years old, and (iv) declared a valid Spanish postal code. Additionally, children and adolescents' answers were considered if both parents and the participating minor provided assent.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis was performed using R language ( 6 ). The significance level for the statistical tests was α = 0.05; Bonferroni correction was applied when using multiple tests. Chi-squared test was applied to tabulated counts of categorical data ( p -values are estimated using Monte Carlo method in the case of small cell counts). Mann–Whitney test is applied to numerical answers; the reported p -value results from the corresponding one-sided test.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol and the Declaration of Helsinki (current version Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013), and following the relevant legal requirements (Law 14/2007 of July 3, 2007, on Biomedical Research). The study protocol, informed consent forms and data collection tools were approved by the Ethics Committee for clinical research of the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain (C.I. PIC-123-20), prior to study initiation.

Demographics

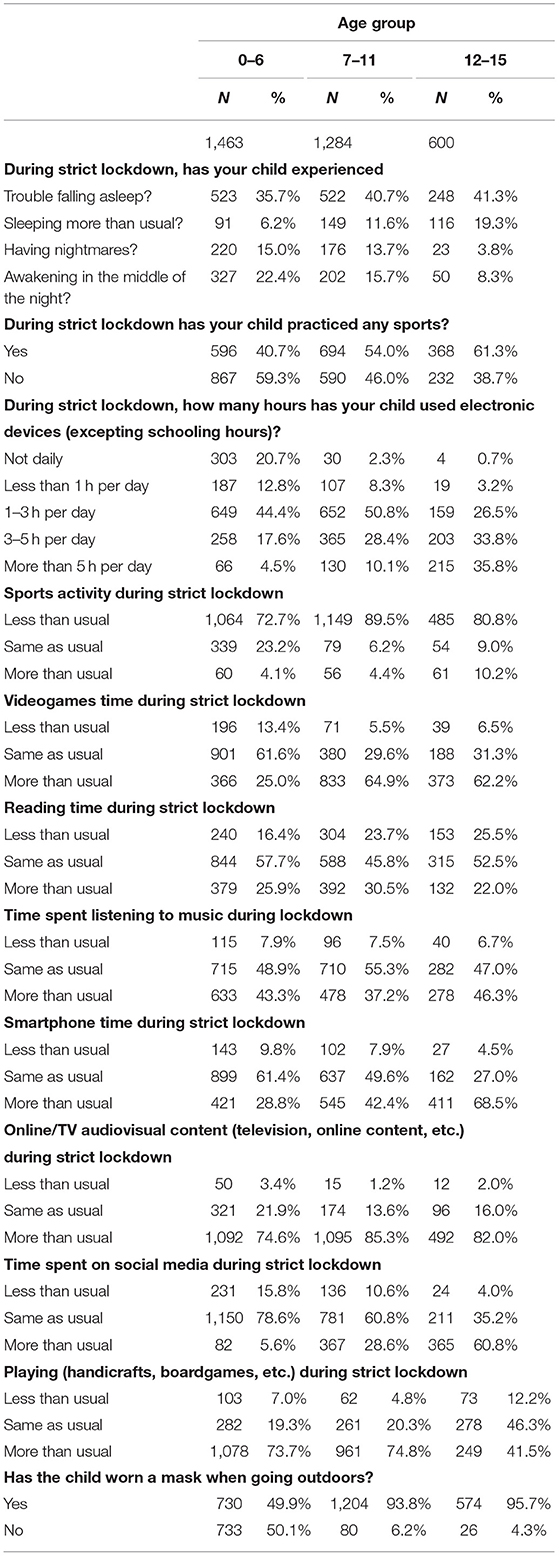

A total of 2,054 families answered the survey, of which 1,957 met the study inclusion criteria. The included surveys covered a total of 3,347 children: 1,463 aged 0–6 years, 1,284 aged 7–11 years, and 600 adolescents aged 12–15 years. All parents answered a questionnaire, one for each daughter or son, independently. Additionally, 13% of the older children (167 answers) and 17% of the adolescents (100 answers) completed the questionnaire specifically addressed to their respective age group. In 57% of the households there was at least 1 adult working in a highly COVID-19 exposed environment (e.g., health centers, hospitals, or old people's retirement homes). The main participants sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Characteristics of the 1,957 families included in the study.

Risk Perception and Transmission Knowledge

At the time of survey completion, 6% of the households reported at least one family member having been affected or currently infected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (microbiologically confirmed infection), and 12% reported at least one suspected case. The majority (84%) of families knew someone infected and 20% knew someone close who had died of COVID-19. Among families with either a suspected or microbiologically confirmed infection, 47% considered a 5–15 year-old child to have been the index case, 22% a 0–4 year-old, 12% a >16 year-old, and 19% reported a simultaneous infection among more than one household member (of varying ages). Median time to subsequent secondary cases was 6.5 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 3–10). When a case was confirmed or suspected at home, measures adopted varied widely between families: 42% followed a strict lockdown of the family, 21% a strict lockdown of the affected person, 16% used a facemask at home, 19% ensured an exclusive use of the sleeping room and bathroom, 19% restricted the use of common spaces, and 39% did not follow any of the aforementioned measures. Regarding parents' opinion about children's role in the pandemic, 42% perceived them to be at high risk of getting infected by SARS-CoV-2, 50% thought strict lockdown measures for children were necessary, 60% considered that children should have had permission to go outside in a controlled way since the first day, and 65% found re-opening of schools was appropriate (98% of them suggested to do it with safety measures in place). During strict lockdown, 88% of children never set foot on the street, while during relaxed lockdown the majority (54%) spent time outdoors at least 3–6 days a week for <1 h/day. Masks were worn by 95% of older children and adolescents and by almost half of the children below 6 years of age, even if this was not mandatory in Spain.

Coping With Confinement

The overall rate of good coping with confinement (rated on a 0–10 scale) was generally very positive. Parents scored their children an 8 [IQR: 6–9] both during strict and relaxed lockdown. Older children scored themselves a 7 [IQR: 5–10] and an 8 [IQR: 6–10], and adolescents scored themselves a 7 [IQR: 6–9] and an 8.5 [IQR: 7–10], during strict and relaxed lockdown, respectively ( Figure 1 ). When asking if they would accept another strict lockdown if necessary due to a hypothetical worsening of the pandemic, 73% of parents, 81% of older children, and 83% of adolescents would accept it. Of note, we found no differences in these answers between children living with a confirmed/suspected case of SARS-CoV-2 and those living without it. One in every five families had an episode of a child needing healthcare attention during strict lockdown (58% febrile episodes, 4% acute mental health problems).

Figure 1 . Overall coping with strict and relaxed lockdown according to parents and to children and adolescents.

Biorhythms (Physical Activity, Alimentary Patterns, and Sleeping Disturbances)

According to parents' perception, during strict lockdown 90% of older children and 81% of adolescents practiced less sports than usual ( Figure 2 ), and 64% of older children and 39% adolescents did not do any kind of sports. On the other hand, during relaxed lockdown, 65% of children and adolescents used the allowed time outdoors to do some kind of sport. When asking parents about weight and eating disturbances, 10% perceived in their children to lose weight and 41% to gain weight. Additionally, 17% reported new eating problems not present before lockdown such as eating less, more and/or in different periodicity than usual, being picky with food, and eating due to anxiety or boredom.

Figure 2 . Time spent doing sports according to parents and to children and adolescents. According to parents' perception, during strict lockdown 90% of older children and 81% of adolescents practiced less sports than usual, similarly as children themselves reported when asked.

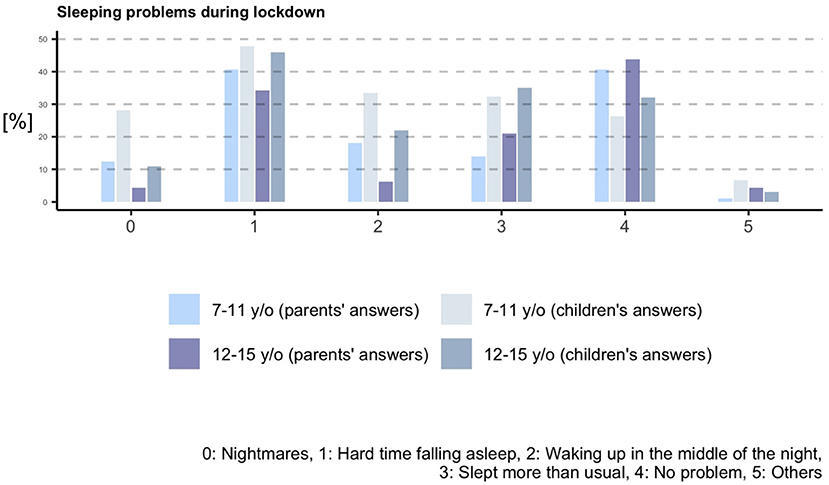

Parents reported sleeping problems during the strict lockdown in 54% of young children, 57% of older children and 59% of adolescents. The most common problem among all age groups was hard time falling asleep. Interestingly, when children and adolescents answered, they reported more sleeping disturbances than their parents ( p = 0.000004 and p = 0.009). In older children, higher self-perception was observed for awakening in the middle of the night (Parents Answering [PA]: 18%, Children Answering [CA]: 33%), sleeping more than usual (PA: 14%, CA: 32%), having a hard time falling asleep (PA: 40%, CA: 48%), and having nightmares (PA: 12%, CA: 28%). Similarly, increased self-perception in adolescents was observed for awakening in the middle of the night (PA: 6%, CA: 22%), sleeping more than usual (PA: 21%, CA: 35%), having a hard time falling asleep (PA: 34%, CA: 46%), and having nightmares (PA: 4%, CA: 11%; Figure 3 ).

Figure 3 . Sleeping problems during lockdown according to parents and to children and adolescents.

Emotional Distress

When we asked parents about emotional distress signs observed in their children, 63% reported to have witnessed them to be more anxious than usual, 63% to be more irritable, 46% to be sadder, and 34% to have other emotional alterations. More than half of older children reported themselves to be more anxious (62%), irritable (55%), and sadder (52%), with median intensities from 4 to 5 out of 10 during strict lockdown. In adolescents, these feelings were reported in 49, 46, and 41% individuals, respectively, with median intensities from 3 to 5 out of 10 during strict lockdown.

Electronic Devices and Social Media

Parents reported that at least one type of electronic device (i.e., smartphone, television or online audiovisual content, videogames, or social media) was used more than usual during strict lockdown in 77% of younger children, 93% of older children, and 95% of adolescents. The most widely used device was television together with online audiovisual content, with 75% of younger children, 85% of older children, and 82% of adolescents using it more often than before the lockdown. Playing videogames also increased in 65% of older children and 62% of adolescents. In addition, adolescents also increased use of their smartphone (68%) and social media (61%). The use time of electronic devices increased with age, being 1–3 h/day the predominant option among all children and 3–5 h/day the predominant option among adolescents. Higher use of social media increased during lockdown in comparison with the usual utilization before lockdown, and was self-reported by 28% of older children and 52% of adolescents. These results are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2 . Answers about sleeping troubles, sports, and electronic devices use reported by parents for each child, distributed by age groups.

Parents scored satisfaction with remote schooling in a 0–10 scale, with a median of 6 [IQR: 4–9] for younger children, and with a median of 7 [IQR: 5–8] for older children. Children themselves scored it with a median of 7 [IQR: 5–8]. The most common score was 10 among the three groups. Both parents of adolescents and teenagers themselves scored schooling satisfaction with a median of 7 [IQR: 5–9], but in this group the mode score was 10 for parents and 8 for the students. When children were asked if they were satisfied with school activities, 26% of children and 35% of adolescents were not. Importantly, 81% of children reported to feel comfortable with schools re-opening compared to a 65% of adolescents, and 52% of the latter thought it was necessary.

Comparisons and Inference

In all age groups, we found higher number of reported sleeping problems (either by parents or by children) among those knowing someone who died of COVID-19 compared to those who did not. Older children who reported to have felt fear or anxiety about going out reported a higher incidence of sleeping disturbances than the ones who did not feel that way (56 vs. 39.3%, p = 0.047). In general, sleeping problems were less likely to happen among children who did sport during lockdown vs. the ones who did not (49.15 vs. 41.67%), especially regarding having trouble falling asleep and sleeping more than usual. Doing sport activities as usual seems to be mildly protective against sleeping problems when compared to spending less time than usual ( p = 0.04). Spending more than 5 h per day looking at screens was a risk factor for some of the sleeping disturbances in teenagers, when compared to 1–3 h of daily use ( p = 0.00087).

Regarding the reported feelings by children and adolescents, the score on irritability was significantly lower among kids (5 [IQR: 2–7] vs. 6 [IQR: 3–8], p = 0.0062) and adolescents (4 [IQR: 1–6] vs. 6 [IQR: 3–7], p = 0.015) who did sport as compared to those who did not. In addition, less physical activity than usual was also found to be associated with an increased feeling of sadness in adolescents, as compared to spending more time than usual doing sport ( p = 0.01). The increased use of social networks above usual levels was found to be associated with increased anxiety levels in teenager reported answers ( p = 0.0077). Among adolescents, being unsatisfied with academic training during lockdown was found to be associated with anxiety ( p = 0.04), and fear of going out in the street was associated with increased perceived sadness ( p = 0.00017).

Here, we described how COVID-19 lockdown has affected children and adolescents' well-being using a set of online questionnaires targeting families in Catalonia and Spain, which reported the status of 3,347 children.

We found that, at the onset of the pandemic, parental perception of children's risk of infection and transmission were generally high, probably supported by the containment measures applied in many countries, which included schools' closure. In other studies, the greatest risk perception has been found in women with lower education who have children in their care ( 7 ). However, recent research suggests that children are less ( 8 ) or equally ( 9 ) likely to become infected than adults when exposed to a case and, when infected, children's symptoms are usually milder ( 9 , 10 ). Interestingly, despite the high-risk initial perception, the majority of parents would have preferred their children to be allowed to spend time outdoors during the entire lockdown period and strongly supported the re-opening of schools with prevention measures in place. It has been recently demonstrated that children's role in SARS-CoV-2 transmission is likely to be weaker than for other age groups during school re-opening due to the prevention tools adopted and children compliance with them ( 11 ).

Parents reported children to cope with confinement reasonably well, according to a previous study where parents reported a more engagement than disengagement-oriented coping strategy in Spanish children during lockdown ( 12 ). Parents, but especially children and adolescents, reported to cope better during the relaxed lockdown compared to the strict lockdown. The change in lockdown measures was positively rated and the allowed time outdoors was mostly used for sports activities. Actually, it has been shown that children missed outdoor exercise during strict lockdown ( 13 ), and that having an outdoor exit in the house (e.g., garden, terrace) contributed to lower levels of psychological and behavioral symptomatology ( 14 ). Indeed, we showed physical and sports activities were highly decreased during lockdown in most children and adolescents as previously reported ( 13 – 16 ), and 39% of children and adolescent did not do sport at all. In addition, 41% of parents reported their children to have suffered weight increases, probably as a result of the reduced physical activity and the reduction of fruit and vegetable consumption ( 15 ).

We found sleeping disturbances during lockdown were reported for the majority of children and adolescents, in accordance with previous studies ( 14 – 17 ). Importantly, we observed that children and adolescents self-reported more sleeping disturbances than what was reported by their parents. Given many of these disturbances are probably not easily observed by caregivers (i.e., nightmares, awakening in the night) unless children are directly asked, interviewing children and adolescents about their well-being should be included in this type of studies, and children's participation in surveys should be further promoted. Despite clear instructions to parents to encourage their children and adolescents to respond a questionnaire, we obtained low participation of children and adolescents in our survey. Eventhough, we still reached a total of 267, allowing making valuable conclusions about their self-reported well-being.

On the other hand, knowing someone who died from COVID-19 was associated with sleeping disturbances, as well as the statement “being afraid or anxious about going outside.” Accordingly, it has been shown that children who knew someone who had suffered from COVID-19 at home or whose parent was directly involved in the pandemic, presented higher anxiety scores ( 18 ). Of note, anxiety and irritability were reported for the majority of children and adolescents, being the youngest the most affected. Similar results have been recently described ( 14 , 17 , 19 , 20 ) and underline the need to consider how we communicate information to children and help them manage this information. Furthermore, it has been shown that anxiety and depressive symptoms and other negative outcomes were more likely in children whose parents reported higher levels of stress, depression or were unemployed ( 18 , 20 – 23 ), and that those were often more important among the youngest ones ( 20 ). Thus, supporting parents' mental health and providing them with accurate information, strategies and support to cope with lockdown is essential to protect their children's mental health ( 24 , 25 ).

We also found that sleeping disturbances were associated with doing less sports than usual, which supports allowing outdoor activity and sports during lockdown periods to protect children's mental health and well-being. Actually, it has been shown a significantly different sleeping time between strict and relaxed confinement ( 15 ). Of note, children who could go outside during COVID-19 restrictions, as well as children whose parents were less stressed, were more likely to meet the physical activity suggested by WHO guidelines ( 24 ), which in turn resulted in reduced psychosocial difficulties ( 16 ). The increase in anxiety, irritability, sadness and changes in biorhythms are adaptive symptoms to stressful situations, and although the expectation is that they will slowly improve when the pandemic restrictions are eased, it is possible that a number of these children and adolescents develop a more serious mental health problem.

In accordance with recent studies, we also found a dramatic increase in electronic devices' usage in all age groups ( 14 , 15 , 23 , 26 ), which has been shown to pose a risk on mental health regardless of the pandemic. The use of Internet has undoubtedly facilitated to some extent the continuity of social and schooling activity during lockdown, especially during strict lockdown. However, deprivation of sports and outdoors activities in favor of screen time consumption might be a damaging trade-off. We found an association between spending more time in electronic devices (>5 h per day) and sleeping disturbances, as well as with reported irritability, sadness and anxiety. In line with our findings, frequent social media exposure has been shown to be positively associated with anxiety ( 26 ). Interestingly, lower screen exposure was observed for the relaxed lockdown period ( 15 ).

Interestingly, and despite having endured the strictest lockdown, most children and adolescents reported acceptance to go back to a strict lockdown if this was required due to the epidemiological situation, reflecting their high resilience and capability to adapt to new situations. The reported acceptance of prevention measures was very high, and even though the use of facemask was not among the most popular measures according to parents, older children and adolescents reported to wear it when spending time outdoors. Of note, the use of facemask is not mandatory in Spain under 6 years of age; however, its use was reported for half of this young children's age group. Despite the possible social desirability bias, the use of facemasks is certainly extended among children. Indeed, a recent study in Spain found that risk perception and age groups with the highest self-perceived risk of disease (51–64 years of age) were also those who went most often outside their homes ( 27 , 28 ). This differs markedly from our results among children, who scrupulously followed the rules and would do so again. Furthermore, children whose parents were more resilient and adopted prevention and safety measures presented fewer negative responses during lockdown ( 12 ), pointing to the impact of adults adhering to prevention measures not only in terms of viral spread, but also in children's safety perception and emotional well-being.