Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 10, Issue 1

- A study of the nature and level of trust between patients and healthcare providers, its dimensions and determinants: a scoping review protocol

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3451-5024 Supathiratheavy Rasiah 1 ,

- Safurah Jaafar 1 ,

- Safiah Yusof 2 ,

- Gnanajothy Ponnudurai 3 ,

- Katrina Pooi Yin Chung 4 ,

- Sasikala Devi Amirthalingam 5

- 1 Community Medicine , International Medical University, Bukit Jalil , Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia

- 2 Nutrition and Dietetics , International Medical University, Bukit Jalil , Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia

- 3 Human Biology , International Medical University , Bukit Jalil , Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia

- 4 Pathology , International Medical University , Bukit Jalil , Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia

- 5 Family Medicine , International Medical University , Bukit Jalil , Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia

- Correspondence to Dr Supathiratheavy Rasiah; supathiratheavy{at}imu.edu.my

Introduction The aim of this scoping review is to systematically search the literature to identify the nature and or level of trust between the patient, the users of health services (eg, clients seeking health promotion and preventive healthcare services) and the individual healthcare providers (doctors, nurses and physiotherapists/ occupational therapists), across public and private healthcare sectors, at all levels of care from primary through secondary to tertiary care. It also aims to identify the factors that influence trust between patients, users of health services (clients) and providers of healthcare at all levels of care from primary care to tertiary care, and across all health sectors (public and private). The study will also identify the tools used to measure trust in the healthcare provider.

Methods and analysis The scoping review will be conducted based on the methodology developed by Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review methodology, and Levac et al ’s methodological enhancement. An experienced information specialist (HM) searched the following databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. The search terms were both keywords in the title and/or abstract and subject headings (eg, MeSH, EMTREE) as appropriate. Search results were downloaded, imported and stored into a ‘Refworks’ folder specifically created for reference management. The preliminary search was conducted between 7 December 2017 and 14 December 2017. Quantitative methods using content analysis will be used to categorise study findings on factors associated with trust between patients, clients and healthcare providers. The collection of studies will be also examined for heterogeneity. Qualitative analysis on peer reviewed articles of qualitative interviews and focus group discussion will be conducted; it allows clear identification of themes arising from the data, facilitating prioritisation, higher order abstraction and theory development. A consultation exercise with stakeholders may be incorporated as a knowledge translation component of the scoping study methodology.

Ethics and dissemination Ethical approval will be obtained for the research project from the Institutional Review Board. The International Medical University will use the findings of this scoping review research to improve the understanding of trust in healthcare, in its endeavour to improve health services delivery in its healthcare clinics and hospitals, and in its teaching and learning curriculum. The findings will also help faculty make evidence based decisions to focus resources and research as well as help to advance the science in this area. Dissemination of the results of the scoping review will be made through peer-reviewed publications, research reports and presentations at conferences and seminars.

- level of Trust in healthcare

- scoping review protocol

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028061

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study seeks to identify the level and nature of trust in healthcare between patients, users of health services and specific individual healthcare providers, for example, physicians, surgeons, nurses, community health workers, physiotherapists and occupational therapists, and pharmacists.

It will review the literature across all levels of care from primary care to tertiary care, and in the private and public sector.

It also seeks to identify the factors that influence trust and the tools used to measure trust in healthcare providers.

The study reviews articles published only in English and over a period of 10 years between January 2007 and December 2017.

The scoping review will not include trust in the provision of health services by dentists, allied health professionals such as phlebotomists, medical laboratory scientists, dietitians and social workers, and in the area of mental health, and trust at the macro level or health systems level, so as to be focused in the scope covered.

Introduction

Context of healthcare provision.

The provision of healthcare occurs in a setting characterised by uncertainty and an element of risk as to the competence and intentions of the healthcare providers. 1 Traditionally, it has been widely accepted that the users or consumers of the service (ie, the patients, and the clients who come for health promotion and preventive healthcare services) trust the judgement, knowledge and expertise of the health professional to provide a competent service. 2 The effective delivery of healthcare requires both the supply of healthcare as well as the acceptance and use of services by the patient and clients. Patient-provider interaction is at the heart of healthcare provision. 2 The nature and environment of healthcare provision occurs on a relational basis—relationships between the providers and users of the service which consequentially impact on health outcomes and wellness.

Trust and its importance in healthcare

Trust is a relational notion between people, people and organisations, and people and events. 3 Patient’s trust in the physician can be defined as a collection of expectations that the patients have from their doctor. 4 It can also be defined as a feeling of reassurance or confidence in the doctor. 5 It is an unwritten agreement between two or more parties for each party to perform a set of agreed upon activities without ‘fear of change from any party’. 6 This is especially true in relationships that result from a lack of choice or occur in a context of asymmetry, such as that between the healthcare provider and patient. Thus, trust is a set of expectations that the healthcare provider will do the best for the patient, and with good will, recognising the patient’s vulnerability. Trust facilitates cooperation between people (known to each other and/or strangers) that is catalysed, facilitated and sustained by trust. 7 Trust is fundamental to effective interpersonal relations and community living. 7 It forms a fundamental basis in the provision of healthcare.

Trust between the patient and the healthcare provider ( doctors, nurses, physiotherapists/occupational therapists ) is important in provider–patient interaction and rapport. It influences patient management outcomes, especially in the treatment of long term illness, as well as influences outcomes of health promotion and prevention initiatives. A trusting relationship between healthcare provider and patient can have a direct therapeutic effect. 8 Trust relations can be distinguished at the micro and macro levels. At the micro level, Trust can be interpersonal trust which is that trust between the individual patient or individual client and the individual clinician, or between two clinicians; organisational or institutional trust is that between the clinician and the manager of the organisation. Trust at the macro level includes trust between patients, the public and the organisation or institution. This study will focus on interpersonal trust between the patient or client and the individual healthcare provider.

Trust is typically associated with high quality communication and interaction, which facilitates disclosure by the patient, enables the practitioner to encourage necessary behaviour changes and may permit the patient greater autonomy in decision-making about treatment. 9

Understanding the issues that influence a person’s trust in the healthcare provider will assist in drawing up suitable operational policies in the delivery of healthcare, as well as influence healthcare practices and behaviours among providers. Transferring this knowledge to medical education will create an emerging practitioner who will be more aligned to the patients’ needs.

Erosion of trust in health care

Critical incidents and sentinel events have contributed to erosion of the patients’ trust in healthcare, the institutions and health systems. 10 The changing sociopolitical environment in healthcare, the impact of the era of information technology and the fact that patients have become increasingly empowered to make informed decisions, have influenced the nature of trust in the healthcare provider. 11

The aim of this scoping review is

To systematically search the literature to identify the nature and or level of trust between the patient, the users of health services and the individual healthcare providers, across public and private healthcare sectors, at all levels of care from primary through secondary to tertiary care.

To identify the factors that influence trust between patients and healthcare providers, at all levels of care from primary through to tertiary level of care, and across all sectors—public and private.

To identify the tools used to measure trust in healthcare between patients, clients and providers of healthcare.

Conceptual framework

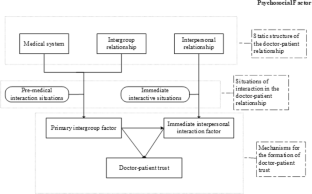

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework for trust in healthcare. The study will explore the nature and or the level of trust at the micro-level between patients and users of health services and the individual healthcare provider. The study will also explore the factors that influence trustbetween patients and healthcare providers.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Conceptual framework of trust in healthcare.

Commissioning agency

This study is commissioned by the International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. The university has identified research on ‘Trust in Healthcare’ as one of its research thrust areas in its journey towards becoming the centre for research on trust in healthcare.

Study design

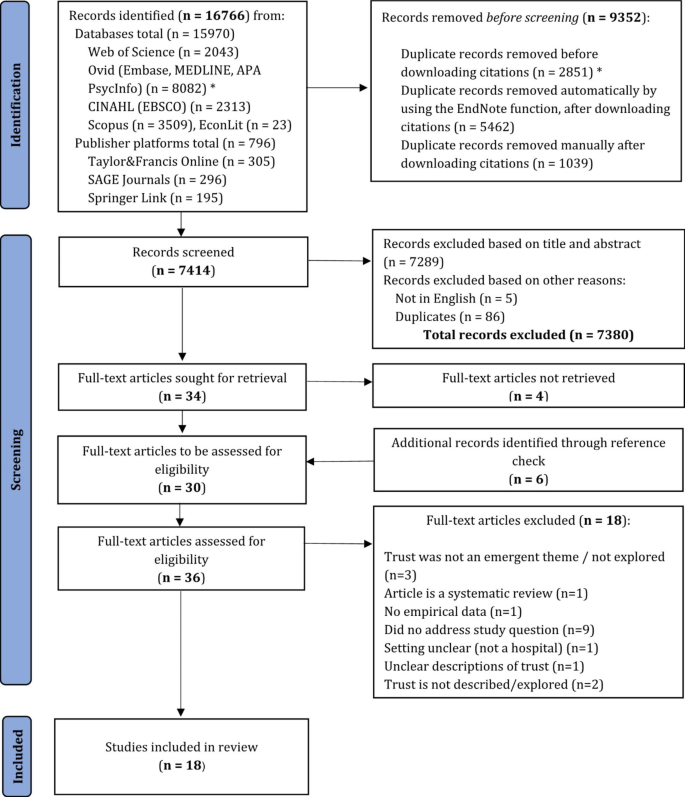

The scoping review will be conducted based on the methodology developed by Arksey and O’Malley’s 12 scoping review methodology, and Levac et al ’s 13 methodological enhancement. This framework identifies six stages in undertaking a scoping review: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist and the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram will be used as a checklist in designing, reviewing and reporting this scoping review.

Stage 1: identifying the research question

The research questions are:

What is the nature and or level of trust between the patient, the users of health services (clients) and the individual healthcare providers (interpersonal trust) across public and private healthcare sectors, at all levels of care from primary through secondary to tertiary care?

What are the factors that influence trust between patients, users of health services and providers of healthcare?

What are the tools used to measure trust in healthcare at the interpersonal level?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

The scoping review will be as comprehensive as possible in identifying primary studies and reviews answering the research questions. The research will be restricted to publications in English between the time period of January 2007 and December 2017 and adhere to the eligibility criteria. A preliminary search was conducted between 7 December 2017 and 14 December 2017.

Information sources and search strategy

An experienced information specialist (HM) searched the following databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. The search terms were both keywords in the title and or abstract and subject headings (eg, MeSH, EMTREE) as appropriate. Search results were downloaded and imported and stored into a ‘Refworks’ folder specifically created for reference management. The preliminary search was conducted between 7 December 2017 and 14 December 2017.

A variety of grey literature will also be searched through the websites of relevant agencies such as the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, to identify studies, reports and conference abstracts of relevance to the research questions of this review. We will also conduct a targeted search of the grey literature in local, provincial, national and international organisations’ websites and related health or scientific organisations. Supplementary articles may be obtained by contacting field experts and searching references of relevant articles.

Stage 3: study selection

Study selection process.

First step: Study selection will be initiated using screening procedures to pull together only potentially eligible studies for the scoping review. It involves two steps of screening. The first step will be to go through all the collected titles and abstracts by two independent reviewers. All retrieved citations are subjected to a set of minimum inclusion criteria. These criteria were tested a priori on a sample of abstracts to ensure that they are robust to capture articles that may relate to ‘Nature and Levels of Trust in Healthcare providers’. Any discrepancies will be resolved either through consensus or, if needed, involvement of a third reviewer. Finally, articles that are selected as deemed relevant by either or both of the reviewers will be included in the full-text review in the second step screening. The online or e-learning articles are not included in the study selection for inclusion .

In the second step, both the reviewers will be assigned to the same articles and assess them in full text. Any disagreement between the reviewers will be resolved through discussion with a third reviewer, and thus facilitating consensus for final inclusion. An inter-rater reliability calculation may be done if needed.

Eligibility criteria

Titles and abstracts of articles which directly matched the identified keywords from year 2007 to 2017 will be filtered for relevance to nature and level of trust between healthcare providers and patients or users of health services. We will include studies that fulfil the following criteria:

The study reported qualitative and or quantitative data on the nature of trust or levels of trust between healthcare providers and patients or users of health services.

The study took place in a healthcare setting.

The study was published or reported in the English language.

The study was published in journals, reports or in conference proceedings as literature.

The study measured interpersonal trust (eg, trust in the nurse, physician, healthcare provider) with a valid, reliable instrument and used an established trust questionnaire (ie, included a reference to a published article which used the respective trust questionnaire) or used a validated questionnaire.

The study looked at factors affecting trust in healthcare between patients, clients and the healthcare provider.

Studies using unvalidated instruments, single item questionnaires or those measuring trust in non-health related environment will be excluded.

Stage 4: data collection

Data items and data abstraction process.

A data extraction form will be created by the research team. This form will be reviewed and pretested by all reviewers before implementation to ensure that it captures the information accurately. All reviewers will be trained and be given an exercise using a random sample of articles to be included in the study. The data extraction form will also be piloted on a sample of five articles by the reviewers involved in the scoping study. The aim is to assess for completeness and ease of use. The percentage of agreement between reviewers will also be measured with a target of at least 80 percent agreement.

To ensure study relevance, the various study characteristics are listed below and, this includes but is not limited to the following:

Publication year.

Source origin/country of origin.

Aims/purpose of the study.

Research/study design.

Methodology.

Population characteristics (eg, number of participants, country, physician specialty).

Nature of Healthcare settings—hospital, clinic types, unit/department, primary care/secondary care/tertiary care, public or private sector.

Description of quality indicators including definition, numerator, dominator, psychometrics of the indicators (face validity, reliability, construct validity, risk adjustment).

Intervention characteristics (eg, concept, duration, engagement strategy, timing, required resources).

Tools used to measure level of trust, physician engagement, intervention results (eg, barriers, facilitators, outcomes).

Any factors reported to be associated with hospital physician engagement:

Demographics.

Characteristics of the work environment (eg, organisational support, quality of work-life and perceptions of safety).

Work attitudes (eg, physician work engagement, job satisfaction, commitment and empowerment).

Work outcomes (eg, patient experience, safety, quality of care, individual and organisational performance).

Key findings that relate to the review questions.

The information extracted will then be summarised and tabulated in an Excel file. Each article will be assigned to two reviewers. The reviewers will work independently to extract the data; the data extracted by the pair of reviewers will be compared, and any discrepancies will be further discussed to ensure consistency between the reviewers. Conflicts will be discussed between the reviewers and consensus obtained. If there is difficulty in reaching a consensus, a third reviewer’s opinion will be obtained. This process is undertaken so as to ensure accurate and reliable data collection.

Stage 5: data summary and synthesis of results

Quantitative methods using content analysis will be used to categorise study findings on factors associated with trust between patients, clients and healthcare providers. The collection of studies will be also examined for heterogeneity. Qualitative analysis on peer reviewed articles of qualitative interviews and focus group discussion will be conducted; it allows clear identification of themes arising from the data, facilitating prioritisation, higher order abstraction and theory development. The findings will be analysed (including descriptive numerical summary analysis and qualitative thematic analysis), discussed and reported.

In reviewing the instruments used to measure trust, they will be evaluated for validity and reliability, as well as to understand the domains which are measured, and how the domains are measured.

Stage 6: consultation

A consultation exercise with stakeholders will be incorporated as a knowledge translation component of the scoping study methodology.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the development of this scoping review protocol.

Data management

All data will be kept confidential and a master index of all studies reviewed will be maintained.

Implications

The findings will be discussed as they relate to the study purpose and implications for future research, practice and policy. The International Medical University will use the findings of this scoping review research to improve the understanding of trust in healthcare, in its endeavour to improve health services delivery by its faculty in its healthcare clinics and hospitals, and in its teaching and learning curriculum. The findings will also help faculty make evidence-based decisions to focus resources and research as well as help to advance the science in this area.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval will be obtained for the research project from the Institutional Review Board of the International Medical University. Dissemination of the scoping review findings will be done through peer-reviewed publications, research reports and conference/seminar presentations.

Acknowledgments

The team would like to acknowledge the following: (1) Mohammad Hisyamuddin (Librarian, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia) who assisted in the initial search for the journal articles and developed the database of articles in the 'Ref works folder'. (2) Dr Teguh Haryo Sasongko Associate Professor Human Biology, School of Medicine International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia who assisted in the final review of the paper.

- Pellegrini CA

- Anderson LA ,

- Caterinicchio RP

- Mechanic D ,

- Chipidza FE ,

- Wallwork RS ,

- Corrigan JM ,

- Donaldson MS

- Blendon RJ ,

- Benson JM ,

- Colquhoun H ,

Contributors SR: main author, conceived the project, developed the conceptual framework for the study, analysed the preliminary data and wrote the manuscript, and also independent reviewer in the preliminary review. SJ: contributed in writing the manuscript and was one of the independent reviewers in the preliminary review. SY: contributed in performing the search working with the librarian to search for and compile the list of relevant journal articles and store in the specific 'Refworks' folder. GP: contributed in writing the manuscript. CPYK: contributed in writing the manuscript. SDA: contributed in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Advertisement

The Formation Mechanism of Trust in Patient from Healthcare Professional’s Perspective: A Conditional Process Model

- Published: 20 January 2022

- Volume 29 , pages 760–772, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Yao Wang 1 , 2 ,

- Qing Wu 1 ,

- Yanjiao Wang 1 &

- Pei Wang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6309-2366 1

853 Accesses

6 Citations

Explore all metrics

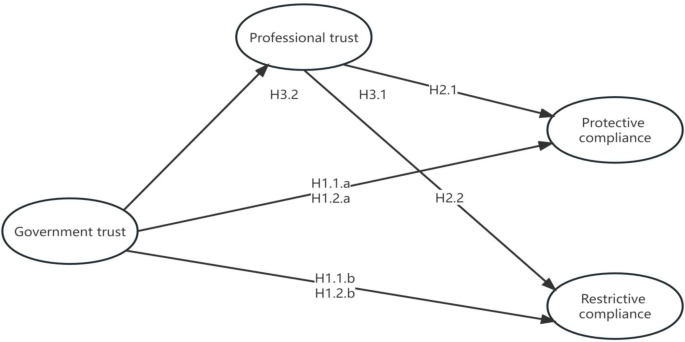

Based on an integrated model of doctor–patient psychological mechanisms, the formation mechanism of doctor-–patient trust was systematically demonstrated from the healthcare professional (HCP)’s perspective integrating intergroup relations (expectations), interpersonal relations (communication), and psychosocial (stereotypes). The results of a survey of 3000 doctors and nurses from 14 provinces in eastern, central, and western China support the rationality of an integrated model of doctor–patient psychological mechanisms. The establishment of doctor–patient trust is influenced by the direct role of primary intergroup factors, the indirect role of immediate interpersonal interactions, and the moderating role of social psychology. Specifically, (1) doctor–patient trust is directly predicted by HCP’s expectation and indirectly influenced by communication; (2) stereotypes regulate the relationship between HCP’s expectation, communication, and doctor–patient trust: the activation of positive stereotypes enhances the positive relationship among the three; Negative stereotypes only positively contribute to mediated pathway-communication behaviors and have a weaker facilitation effect compared to positive stereotypes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

We’re sorry, something doesn't seem to be working properly.

Please try refreshing the page. If that doesn't work, please contact support so we can address the problem.

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Social trust, interpersonal trust and self-rated health in china: a multi-level study.

Zhixin Feng, Athina Vlachantoni, … Kelvyn Jones

The Relationship Between the Physician-Patient Relationship, Physician Empathy Query ID="Q1" Text=" Please check if the captured title is correct." , and Patient Trust

Qing Wu, Zheyu Jin & Pei Wang

Trust and Its Role in the Medical Encounter

Stephen Holland & David Stocks

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Agliata, A. K., & Renk, K. (2009). College students’ affective distress: The role of expectation discrepancies and communication. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18 (4), 396.

Article Google Scholar

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64 (6p1), 359.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986(23–28)

Barber, B. (1983). The logic and limits of trust . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Baviskar, K. (2015). Doctor-patient relation a study of communication. Asian Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 5 (9), 1–8.

Birkhäuer, J., Gaab, J., & Calnan, M. (2017). Is having a trusting doctor-patient relationship better for patients’ health? European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare, 5 (1), 145–147.

Bostan, S., Acuner, T., & Yilmaz, G. (2007). Patient (customer) expectations in hospitals. Health Policy, 82 (1), 62–70.

Cegala, D. J., Coleman, M. T., & Turner, J. W. (1998). The development and partial assessment of the medical communication competence scale. Health Communication, 10 (3), 261–288.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Chai, M. Q., & Wang., J., (2016). An exploration of formation mechanism of doctor-patient trust crisis: From the perspective of intergroup relationship. Journal of Nanjing Normal University (Social Science Edition) , 02

Chang, P.-C., Wu, T., & Du, J. (2020). Psychological contract violation and patient’s antisocial behaviour. International Journal of Conflict Management, 31 (4), 647–664. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijcma-07-2019-0119

Chrisler, J. C., Barney, A., & Palatino, B. (2016). Ageism can be hazardous to women’s health: Ageism, sexism, and stereotypes of older women in the healthcare system. Journal of Social Issues, 72 (1), 86–104.

Cook, K. S., Kramer, R. M., Thom, D. H., Stepanikova, I., Mollborn, S. B., & Cooper, R. M. (2004). Trust and distrust in patient-physician relationships: Perceived determinants of high-and low-trust relationships in managed-care settings . Russell Sage Foundation.

Google Scholar

Crisp, R. J., & Turner, R. N. (2009). Can imagined interactions produce positive perceptions?: Reducing prejudice through simulated social contact. American Psychologist, 64 (4), 231–240.

Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92 (4), 631–648.

Dhingra, C., Anand, R., & Prasad, S. (2014). Reflection over doctor patient relationship: A promise of trust. Journal of Oral Health & Community Dentistry , 8 (2)

Dong, X. (2020). New interpretation of trust from the holistic perspective. Journal of China University of Mining & Technology(Social Sciences) , (1009–105X), 1–10.

Dong, Z., & Chen, C. (2016). A preliminary study of validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Physician Trust in Patient Scale. Chinese Mental Health Journal , 30(7), 481–485.

Douglass, T., & Calnan, M. (2016). Trust matters for doctors? Towards an agenda for research. Social Theory & Health, 14 (4), 393–413.

Du, L., Xu, J., Chen, X., Zhu, X., Zhang, Y., Wu, R., Ji, H., & Zhou, L. (2020). Rebuild doctor–patient trust in medical service delivery in China. Scientific Reports, 10 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78921-y

Article CAS Google Scholar

Gabay, G. (2019). Patient self-worth and communication barriers to trust of Israeli patients in acute-care physicians at public general hospitals. Qualitative Health Research, 29 (13), 1954–1966.

Glasman, L. R., & Albarracín, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132 (5), 778.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Greene, J., & Ramos, C. (2021). A mixed methods examination of health care provider behaviors that build patients’ trust. Patient Education and Counseling, 104 (5), 1222–1228.

Grob, R., Darien, G., & Meyers, D. (2019). Why physicians should trust in patients. JAMA, 321 (14), 1347.

Guo, A., & Wang, P. (2020). The current state of doctors’ communication skills in Mainland China from the perspective of doctors’ self-evaluation and patients’ evaluation: A cross-sectional study. Patient Education and Counseling, 104 , 1–7.

Hao, J., Yang, J., Peng, Y., & Ma, X. (2016). Factor analysis of patients’ trust of township health centers in suburbs, Beijing. Medicine and Society, 29(4), 17–19.

Hauer, K. E., Fernandez, A., Teherani, A., Boscardin, C. K., & Saba, G. W. (2011). Assessment of medical students’ shared decision-making in standardized patient encounters. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26 (4), 367–372.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling . University of Kansas.

Higgins, E. T., Idson, L. C., Freitas, A. L., Spiegel, S., & Molden, D. C. (2003). Transfer of value from fit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84 (6), 1140.

Hillen, M., De Haes, H., Stalpers, L., Klinkenbijl, J., Eddes, E., Butow, P., van der Vloodt, J., van Laarhoven, H. W., & Smets, E. (2014). How can communication by oncologists enhance patients’ trust? An experimental study. Annals of Oncology, 25 (4), 896–901.

Koirala, N. (2019). Trust and communication in a doctor patient relationship. Birat Journal of Health Sciences, 4 (3), 770–770.

Kuzla, A. (2017). A review of acceptant responses to stereotype threat: Performance expectations and self-handicapping strategies. DTCF Dergisi, 57 (2), 1223–1248.

Li, Y., & Wang, P. (2018). The social psychological mechanism of the construction of doctor-patient trust. Chinese Social Psychological Review, 14 , 4–15.

Liu, J., Yu, C., Li, C., & Han, J. (2020). Cooperation or conflict in doctor-patient relationship? An analysis from the perspective of evolutionary game. IEEE Access, 8 , 42898–42908.

Luhmann, N. (2018). Trust and power . Wiley.

Makoul, G. (2001). The SEGUE framework for teaching and assessing communication skills. Patient Education and Counseling, 45 (1), 23–34.

Marx, D. M., & Stapel, D. A. (2006). Understanding stereotype lift: On the role of the social self. Social Cognition, 24 (6), 776–792.

Nie, J. B., Cheng, Y., Zou, X., Gong, N., Tucker, J. D., Wong, B., & Kleinman, A. (2018). The vicious circle of patient–physician mistrust in China: Health professionals’ perspectives, institutional conflict of interest, and building trust through medical professionalism. Developing World Bioethics, 18 (1), 26–36.

Oettingen, G., & Mayer, D. (2002). The motivating function of thinking about the future: Expectations versus fantasies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 (5), 1198.

Perna, G., Varriale, L., & Ferrara, M. (2019). The role of communication in stereotypes, prejudices and professional identity: The case of nurses. Organizing for digital innovation (pp. 79–95). Springer International Publishing.

Chapter Google Scholar

Petrocchi, S., Iannello, P., Lecciso, F., Levante, A., Antonietti, A., & Schulz, P. (2019a). Interpersonal trust in doctor-patient relation: Evidence from dyadic analysis and association with quality of dyadic communication. Social Science & Medicine, 235 , 112391.

Petrocchi, S., Iannello, P., Lecciso, F., Levante, A., Antonietti, A., & Schulz, P. J. (2019b). Interpersonal trust in doctor-patient relation: Evidence from dyadic analysis and association with quality of dyadic communication. Social Science & Medicine . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112391

Prizer, L. P., Gay, J. L., Perkins, M. M., Wilson, M. G., Emerson, K. G., Glass, A. P., & Miyasaki, J. M. (2017). Using social exchange theory to understand non-terminal palliative care referral practices for Parkinson’s disease patients. Palliative Medicine, 31 (9), 861–867.

Qu, X. P., & Ye, X. C. (2014). Development and evaluation research of measurement tools for stereotypes of doctor role perception. Chinese Hospital Management, 34 (2), 48–50.

Riva, S., & Pravettoni, G. (2014). How to define trust in medical consultation? A new perspective with the game theory approach. Global Journal for Research Analysis, 3 (8), 76–79.

Rosenthal, R. (2003). Covert communication in laboratories, classrooms, and the truly real world. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12 (5), 151–154.

Ruan, X., & Xiao, X. (2017). Correlation analysis on trusted patient assessment and occupational well-being of pediatricians in Wuhan City. Occup and Health, 33 (12), 1661–1664.

Ruscher, J. B. (1998). Prejudice and stereotyping in everyday communication. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30 , 241–307.

Scheid, T. L., & Smith, G. H. (2017). Is physician-patient concordance associated with greater trust for women of low socioeconomic status? Women & Health, 57 (6), 631–649.

Schneider, D. J. (2005). The psychology of stereotyping . Guilford Press.

Shah, R., & Ogden, J. (2006). ‘What’s in a face?’The role of doctor ethnicity, age and gender in the formation of patients’ judgements: An experimental study. Patient Education and Counseling, 60 (2), 136–141.

Sherlock, R. (1986). Reasonable men and sick human beings. The American Journal of Medicine, 80 (1), 2–4.

Shih, M., Ambady, N., Richeson, J. A., Fujita, K., & Gray, H. M. (2002). Stereotype performance boosts: The impact of self-relevance and the manner of stereotype activation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 (3), 638.

Skirbekk, H., Middelthon, A.-L., Hjortdahl, P., & Finset, A. (2011). Mandates of trust in the doctor–patient relationship. Qualitative Health Research, 21 (9), 1182–1190.

Street, R. L., Jr. (2002). Gender differences in health care provider–patient communication: Are they due to style, stereotypes, or accommodation? Patient Education and Counseling, 48 (3), 201–206.

Sun, L., & Wang, P. (2019a). Theoretical system of the harmonious doctor-patient relationship evaluation. Journal of Shanghai Normal University(Philosophy & Social Sciences Edition), 48 (05), 88–98.

Sun, L., & Wang, P. (2019b). Theory construction on the psychological mechanism of the harmonious doctor-patient relationship and its promoting technology. Advances in Psychological Science, 27 (6), 951–964.

Thom, D. H., & Campbell, B. (1997). foTlG INALRESEARCH patient-physician trust: An exploratory study. The Journal of Family Practice, 44 (2), 169.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Thom, D. H., Wong, S. T., Guzman, D., Wu, A., Penko, J., Miaskowski, C., & Kushel, M. (2011). Physician trust in the patient: Development and validation of a new measure. The Annals of Family Medicine, 9 (2), 148–154.

Thorne, S. E., & Robinson, C. A. (1988). Reciprocal trust in health care relationships. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 13 (6), 782–789.

Tyler, R., & Pugh, L. C. (2009). Application of the theory of unpleasant symptoms in bariatric surgery. Bariatric Nursing and Surgical Patient Care, 4 (4), 271–276.

Wang, P. (1999). A review of social cognitive research on stereotypes. Journal of Psychological Science, 22 (4), 342–345.

Wang, X. J., & Wang, C. (2016). Doctor-patient trust in contemporary China: Characteristics, current situation and research prospects. Journal of Nanjing Normal University (Social Science Edition), 2 , 102–109.

Wang, P., Yin, Z., Luo, X., Ye, X., & Bai, Y. (2018). The impact of doctor-patient communication frequency on the stereotype of the doctor. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 16 (1), 119.

Ward, P. (2018). Trust and communication in a doctor-patient relationship: A literature review. Arch Med, 3 (3), 36.

Xu, L. L., Sun, L. N., Li, J. Q., Zhao, H. H., & He, W. (2021). Metastereotypes impairing doctor–patient relations: The roles of intergroup anxiety and patient trust. PsyCh Journal, 10 (2), 275–282.

Yao, Q., Ma, H. W., & Yue, G. A. (2010). Success expectations and performance: Regulatory focus as a moderator. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 42 (06), 704.

Yoshihisa, K., & Victoria, W.-L.Y. (2010). Serial reproduction: An experimental simulation of cultural dynamics. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 42 (01), 56–71.

Zhang, B., Yuan, F., & Xu, L. (2014). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat: intervention strategies and future directions. Journal of Psychological Science, 37 (1), 197–204.

Zhang, N., & Zhao, J. (2014). Research on credibility crisis in doctor-patient relationship based on expectation disconfirmation theory. Chinese Medical Ethics, 27 (3), 391–393.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of our partner hospitals for their help in collecting data.

This research was supported by Major bidding projects for National Social Sciences Fund of China (17ZDA327).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, No. 3663 North Zhongshan Road, 200062

Yao Wang, Qing Wu, Yanjiao Wang & Pei Wang

College of Education, Lanzhou City University, Lanzhou, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

YW and QW contributed equally to this article. YW and QW: design of the work; analysis, interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. YW: proofreading manuscript. PW: validation, investigation, resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, and final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pei Wang .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

Yao Wang, Qing Wu, Yanjiao Wang, and Pei Wang declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the local ethics committee of Shanghai Normal University and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

Consent to Participate

All participants were informed before the investigation began. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Normal University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wang, Y., Wu, Q., Wang, Y. et al. The Formation Mechanism of Trust in Patient from Healthcare Professional’s Perspective: A Conditional Process Model. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 29 , 760–772 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-021-09834-9

Download citation

Accepted : 01 December 2021

Published : 20 January 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-021-09834-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Integrated model of doctor–patient psychological mechanisms

- Healthcare professional’s expectations

- Doctor–patient trust

- Communication

- Conditional process model

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Analyzing patient trust through the lens of hospitals managers—The other side of the coin

Contributed equally to this work with: Aviad Tur-Sinai, Royi Barnea

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Health Systems Management, The Max Stern Yezreel Valley College, Yezreel Valley, Israel, School of Nursing, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Assuta Health Services Research Institute, Tel Aviv, Israel

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Shamir Medical Center (Assaf Harofeh), Be’er Ya’akov, Israel, Israeli Center for Emerging Technologies (ICET), Tel Aviv, Israel, Department of Management, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel

- Aviad Tur-Sinai,

- Royi Barnea,

- Published: April 26, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250626

- Reader Comments

Trust is an essential element in patient-physician relationships, yet trust is perceived differently among providers and customers exist. During January-February 2020 we examined the standpoints of medical managers and administrative directors from the private and public health hospitals on patient-physician trust, using a structured questionnaire. Thirty-six managers in public and private hospitals (24 from the public sector and 12 from the private sector) responded to the survey. Managers in the private sector rated trust higher in comparison to managers in the public sector, including trust related to patient satisfaction, professionalism and accountability. Managers from public hospitals gave higher scores to the need for patient education and shared responsibility prior to medical procedures. Administrative directors gave higher scores to various dimensions of trust and autonomy while medical managers gave higher scores to economic considerations. Trust is a fundamental component of the healthcare system and may be used to improve the provision and quality of care by analyzing standpoints and comparable continuous monitoring. Differences in position, education and training influence the perception of trust among managers in the health system. This survey may allow policy makers and opinion leaders to continue building and maintaining trust between patients and care providers.

Citation: Tur-Sinai A, Barnea R, Tal O (2021) Analyzing patient trust through the lens of hospitals managers—The other side of the coin. PLoS ONE 16(4): e0250626. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250626

Editor: Anat Gesser-Edelsburg, University of Haifa, ISRAEL

Received: January 20, 2021; Accepted: April 10, 2021; Published: April 26, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Tur-Sinai et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data used in this study contains sensitive information about the study participants and they did not provide consent for public data sharing. The current approvals by the Ethical Committees of Assuta Medical Center and Shamir Medical Center (reference numbers 0108-19-ASF and 0034-19-ASMC) do not include data sharing. A minimal data set could be shared by request from a qualified academic investigator for the sole purpose of replicating the present study, provided the data transfer is in agreement with IL legislation on the general data protection regulation and approval by the Israeli Ethical Review Authority. Contact information: Mrs. Michal Yannay, Research Ethics Committee, Assuta Medical Center: [email protected] , Israel; Prof. Matityahu Berkovitch, Research Ethics Committee, Shamir Medical Center: [email protected] , Israel.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Patient trust is a fundamental cornerstone in patient-physician encounters [ 1 ], yielding improvement in health outcomes, continuity of care and satisfaction [ 2 , 3 ]. Although the definition of "trust" is still vague, it contains components of loyalty, personal care, consistent longitudinal care [ 4 ], regular good experiences, increasing knowledge [ 5 ], contentment [ 6 ], sometimes acknowledged as "personal doctoring" [ 7 ].

Although all partners involved in patient care; i physicians, patients and their families and medical managers, believe that trust has become one of the foundations of modern healthcare, these relationships are often unbalanced. Individuals who seek healthcare services may perceive the medical environment as precarious due to the risk of medical errors [ 8 ] Complete trust in the physician may be fragile, and requires to increase physicians’ awareness, compassion [ 9 ] and training [ 10 ]. Moreover, in the overloaded work environment of physicians, patient expectations are not always fully understood or accepted by the treating physician.

Within the medical world, surgical procedures emphasize the patient-physician relationship. The informed consent procedure prior to surgery is a unique opportunity to achieve patients’ trust by using medical knowledge in order to help patients overcome their fear [ 11 ], improve satisfaction and enhance patients’ experience.

Achieving patient trust in a hospital setting requires more than a simple person to person encounter. Patients’ experience is often associated with waiting times for hospital appointments, and threatening events such as a treatment or surgery. Sometimes the experience reflects the weakness of the individual patient by highlighting socioeconomic gaps in accessibility to care [ 12 ].

Lack of resources and poor leadership may impact the health system, described as "key factors leading to providers’ inadequate trust, contributed to poor quality services, driving a perverse cycle of negative patient–provider relations" [ 13 ]. A factor analysis of patient perception of trust showed that the contribution of empathy and assurance was relatively low and explained 8% and 5.6% of trust respectively, in comparison to comfortable facilities and appearance (21%), confidentiality (18.7%) and staff responsiveness (16%) [ 14 ]. The type of provider (public/private), hospital experience, the format of insurance coverage, freedom of choice also affect trust and distrust, alongside the configuration of the healthcare system [ 15 ].

A cross-sectional analysis in 23 countries [ 16 ] revealed that trust in physicians differs among health systems and may correlate to health strategy and policy, and to the nature of the health system itself. Trust in physicians was significantly higher in decommodified countries that highlight health as a basic human right (e.g., the United Kingdom, Japan, Norway and the Netherlands) than in commodified countries such as United States (3.8 vs. 3.4; P = 0.0035). The net support of family members, representing high "social trust" [ 17 ], can play a role in the physician-patient-family trust triangle.

The Israeli healthcare system is publicly funded, relying on governmental accountability. Provision of care is available through four health maintenance organizations (HMOs) to any citizen needing medical attention regardless of the ability to pay. Three tiers of coverage are provided: Tier 1 is universal coverage under the National Health Insurance Law (1995) to all residents in accordance with a standard positive list (“basket”) including surgery, acute and rehabilitative inpatient care, medications, and community care. For medications, tests, and treatments in the community, however, copays are charged. Tier 2 comprises supplemental insurance arrangements delivered by the HMOs, including a list of treatments, services, and medications, but only a few palliative medications, and no life-saving ones. Furthermore, the HMOs’ supplemental policies differ in terms, types and extent of oncological coverage. Tier 3 contains various private health insurance policies (personal and group). People who lack private coverage are, of course, susceptible to pay for care not included in the basic basket.

Due to dwindling resources in the Israeli public healthcare system [ 18 ], surgical waiting times may be prolonged, causing many patients to seek treatment in private healthcare. Although the proportion of surgical positions in private hospitals is only 11% of all surgery positions in Israel, approximately a quarter of all surgeries are conducted in the private healthcare system [ 19 ], where patients use their private (commercial) insurance or HMO’s supplementary insurance. Notably, only elective procedures are performed in private hospitals [ 20 ].

The researchers decided to regard patient-physician trust from two opposite directions: a "top-down" approach centered on the patient and excellency in care, and a "bottom-up" approach that involves medium-level managers, medical executives and heads of clinical departments in patient-physician dialogues. Although trust is currently well-established in patient-physician interactions, its vague definition may lead to differences in perceptions, standpoints and behavior among various stakeholders–service providers as well as customers/patients. To understand and improve the patient-physician dialogue, this study was aimed to understand health managers’ perceptions of trust. Specifically, (1) to examine the standpoints of the medical leadership (comprising leading clinical experts who stance as medical managers and administrative executives) on patient-physician trust; and (2) to identify trends and compare similarities and gaps between the private and public health sectors.

This cross-sectional study was conducted during January-February 2020 among physicians in managerial positions (clinical and department managers and hospital medical executives) and administrative managers working in general hospitals in the public and private sectors in Israel. Altogether the 24 public and the 4 private general hospitals in the country were approached, thus reflecting leaders from the entire healthcare system.

Sampling technique

37 managers were approached and 36 agreed to participate: 24 in public and 12 in the private hospitals in Israel. Potential participants were chosen by their involvement in policy decision-making discussion groups and relevance to the study’s aim. The proportion of participants from each sector was determined by the ratio of private to public general hospitals in Israel (5:11). All participants were approached personally with a request to participate in the study and all of them agreed to participate. None of the managers refused to participate in the survey.

Prior to administering the questionnaire, the purpose and procedure of the survey were explained in a telephone call.

Ethical issues

The study was formally approved by the Ethical Committees of Assuta Medical Center and Shamir Medical Center. Each medical center’s Helsinki committees approved the study ethics, the procedure, and the survey questionnaire (reference numbers 0108-19-ASF and 0034-19-ASMC). The participants were informed in writing that their answers would be kept secret for the purposes of the study and they were required to declare their consent to this. All the participants were provided with information regarding the research purpose, confidentiality of information, and right to revoke the participation without prior justification.

Questionnaire and data collection

A structured questionnaire was used to collect opinions via personal interviews. The questionnaire included 61 items in 4 parts, based on a grounded theory [ 21 ], with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.9172: (A) Components of trust in caregivers and providers (3 questions), values and ideological principles, such as autonomy, satisfaction, accountability freedom of choice and economic implication of care utilization (8 questions); (B) Potential implications of surveys as tools to assess patients as customers (8 questions), personal values of the participating manager (4 questions); (C) Perceived understanding and trust of patients in ten selected operative procedures (30 questions), the effect of low patient trust on caregivers (one question); (D) participant demographics (7 questions). The participants rated each item on a scale of 1 (fully disagree) to 10 (fully agree).

The operative procedures discussed in Section C of the questionnaire were chosen by an expert committee to represent highly prevalent procedures (with significant activity in private and public hospitals) in a variety of clinical fields and populations. These included: adenoidectomy, appendectomy, cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, mastectomy, repair of inguinal hernia, repair of undiscerning testicle, rhinoplasty, total hip replacement and total knee replacement.

Statistical analysis

For each of the questionnaire items, means and Standard Deviations were calculated in accordance with the various reference groups—type of provider (public sector or private) and position of manager/director (director or administrative). The mean and the S.D. of each of the various dimensions were calculated the same way, including, as stated, references to several questions for each.

To check statistical variance among the reference groups in regard to each the dimension and research question, an independent t-test was performed. Also, a 95% CI was calculated in order to examine the difference in the mean for each of the dimensions, in accordance with the various reference groups, as well as the Cohen’s d effect size.

A total of 36 managers participated in the study: 24 participants (17 men and 9 women) from 5 public hospitals, and 12 participants (9 men and 3 women) from 4 private hospitals. Nineteen participants were physicians in clinical managerial positions and 17 were clinicians in executive managerial positions that also had medical management training.

Service provider (private vs. public)

Managers working in the private sector (PRsM) rated core variables related to patient satisfaction and aspects of trust in physicians, the hospital and the healthcare system as a whole, higher compared to the average rating of managers working in the public sector (PBsM) (8.61 vs. 7.89, p = 0.04). They also rated variables related to autonomy and economic considerations higher than PBsM (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (7.43 vs. 6.85, p = 0.40 and 7.59 vs. 6.38, p = 0.23, respectively) ( Table 1 ). PRsM also gave higher ratings, compared to PBsM, to variables relating to professionalism and accountability, such as physician accountability for best practice (9.17 vs. 6.96, p = 0.01), the hospital’s accountability to supply good care (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (8.42 vs. 7.50, p = 0.21), the freedom to choose a specific surgeon (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (8.36 vs. 7.75, p = 0.48), and payment as a factor in care provision from the perspective of the caregiver and the hospital (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (7.89 vs. 6.25, p = 0.17; 7.30 vs. 5.89, p = 0.49, respectively) ( S1 Appendix ). PRsM also gave higher scores to the opportunity to use surveys as potential tools for assessing the patient as a customer. In contrast, PBsM gave higher ratings to two perceived beneficial implications of such a survey: being a tool for strategic planning (7.29 vs 6.69, p = 0.04), and the need to educate medical students to listen to their patients, and to integrate patients values and wishes in a shared decision making approach (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (9.28 vs 8.92 p = 0.23). PRsM gave higher scores to patients’ preliminary knowledge regarding the procedures (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (7.34 vs. 7.05, p = 0.49). On the other hand, PBsM gave higher scores to the need for patient’s education prior to medical procedures (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (7.95 vs. 7.49 p = 0.26) as well as to shared responsibility in decision making (8.70 vs. 7.28 p<0.01) ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250626.t001

An elaboration of the dimensions and a one-by-one examination of the ten specific operative procedures included in the survey revealed a consistent trend of higher average trust scores by PBsM compared to PRsM in eight of the ten operative procedures: appendectomy (9.00 vs. 6.55 respectively, p<0.01), gallbladder removal (8.63 vs, 7.18, p = 0.02), inguinal hernia (8.92 vs. 7.67, p = 0.01), hysterectomy (8.71 vs. 7.42, p = 0.01), mastectomy (9.08 vs. 8.36, p = 0.08) (an observed difference with proximity to p = 0.05 limit), rhinoplasty (8.38 vs. 7.42, p = 0.06) (an observed difference with proximity to p = 0.05 limit), undescended testicle repair (8.58 vs. 7.10, p = 0.04) and tonsillectomy (8.83 vs. 7.58, p = 0.01) ( S2 Appendix ).

Comparative scoring of the consequence of knowledge transfer from physicians to patients revealed dissimilarities among the participants; for example, PBsM rated the importance of providing knowledge or the added value of explanation/education significantly higher in hysterectomy (8.17 vs.7.00, p = 0.03) and tonsillectomy (8.50 vs 7.58 respectively, p = 0.06) (an observed difference with proximity to p = 0.05 limit) compared with PRsM ( S2 Appendix ). In other cases the opposite picture was revealed: PRsM rated the importance of providing knowledge on knee replacement and inguinal hernia significantly higher compared to PBsM (8.08 vs. 6.42, p = 0.01 and 9.00 vs. 7.46 p<0.01, respectively).

The role and position of the participating managers (Medical Managers vs. Administrative Directors)

Administrative Directors (AD) had rated dimensions of trust and autonomy higher than medical managers (MM) (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (8.65 vs. 7.67, p<0.01 and 7.29 vs. 6.82, p = 0.47, respectively). AD also rated patients’ preliminary knowledge regarding the procedures and the need for patient education prior to medical procedures higher than MM (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (7.98 vs. 7.63, p = 0.36 and 7.29 vs. 7.01 p = 0.48, respectively). MM rated economic considerations and sharing responsibility regarding treatment decisions higher than AD (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (7.11 vs. 6.34, p = 0.42, and 8.41 vs. 8.02 p = 0.42, respectively) ( Table 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250626.t002

Dimensions related to the perception of patient surveys as a managerial or planning tool or as a barometer to partnership in care showed even smaller difference between MM and AD (while despite having observed a difference, it is not possible to draw a statistically supported conclusion) (7.12 vs 7.08, p = 0.96 and 9.19 vs 9.12, p = 0.79, respectively).

MM rated trust within the scope of particular operative procedures consistently higher than AD, as demonstrated for appendectomy (8.79 vs. 7.56 respectively, p = 0.06) (an observed difference with proximity to p = 0.05 limit). In contrast, AD rated the importance of knowledge transfer to the patient or the added value of explanation/education significantly higher than MM in procedures such as mastectomy (8.19 vs. 7.26, p = 0.05), knee replacement (8.24 vs. 7.16, p = 0.02) and hip replacement (8.06 vs. 7.11, p = 0.04) ( S2 Appendix ).

A qualitative analysis of free text remarks added to the questionnaire revealed PRsM mentioned that the major forces leading to patient-physician trust are cohesiveness within the multidisciplinary team members, while PBsM emphasized professionalism as a leading vector. PRsM refere to economic incentives as obstacles to the perception of full trust; such as fair pricing, charges or mode of payment. In comparison, PBsM mentioned socioeconomic gaps or disparities in accessibility to care as barriers to full trust.

"Trust" is a complex entity, composed of sharing of knowledge, responsibility and satisfaction, and increases safety behavior and perception [ 22 ] when both sides rely on each other and have an incentive to join forces to keep a "contract". Traditionally surveys refer to either the patient’s standpoint or less frequently to physicians values, yet rarely introduce the perspective of the medical leadership. Our unique contribution focuses on the standpoints on medical managers, presenting differences according to their expertise, position and provider sector. The analysis revealed several trends, however we primarily focus on the most significant finding., The importance of trust as a general value was ranked higher by administrative managers compared to clinical managers and by managers in the private sector compared to managers in the public sector. On the contrary the value of patient- doctor partnership or "shared responsibility" was ranked higher by public sector managers in comparison with private sector managers, while position (medical vs administrative) showed no significant differences. A profound observation reveals administrative managers deeply appreciate trust among all stakeholders- the general practitioner, the surgeon and the entire healthcare. They also emphasized the caregiver’s responsibility as a key professional principle. Analysis by the type of provider showed private sector managers unsurprisingly highlighted the responsibility of the physician regarding the patient-doctor equation, moreover they suggest such surveys may be used as managerial tool for further planning and improvement.

Other topics investigated in our questionnaire revealed no significant differences among the groups of participants, although clues to trends were traced; for example PBsM gave ranked higher freedom of choice and considering patients’ preferences, alongside the added value of residents’ education and the opportunity of data sharing.

The same trend exists across almost all types of operative procedures examined, PRsM attributed greater importance of professionalism and accountability, probably due to the frequent attention drawn to these elements by their board of directors. This may be explained by the characteristics of the targeted encounter between the patient and the physician in the public health sector, shortly before the surgical procedure. In contrast, in the private healthcare system the patient-physician relationship starts in a consultation meeting prior to the surgery, and the patient has several opportunities to create trust with the care provider and to consider options for care before the operative procedure take place.

Our findings, which indicate higher trust levels among managers in the private health sector compared to the public setting are in line with Niv-Yagoda’s work, which showed an association between low levels of trust in the public healthcare system and the public’s perception regarding the importance of patient’s autonomy (e.g., selecting a surgeon) [ 23 ].

We believe that the executive managers rated trust higher than their counterparts due to their experience and holistic approach emphasizing the current focus on patient empowerment and the MoH strategic guidance to implement patient-centered policy. Interestingly, clinical professional experts highlighted economic issues, which are considered a barrier to consumption of health services, in particular, elective surgeries. Clinical managers may also consider the economic burden as a bigger threat to avoid maximal beneficial treatment to socially deprived populations.

The qualitative analysis of participants’ remarks added to the questionnaire, revealed differences in the major themes about factors influencing trust as well a spectrum of positive and negative sentiments: PRsM regard effective multidisciplinary teamwork as a leading force to trust, while economic barriers may reduce trust. PBsM believe professionalism is the foremost vector to gain trust, while socioeconomic gaps decrease trust.

As every Israeli resident is entitled by law to receive surgery in the public healthcare system, regardless of his/her financial resources, it is possible that PBsM expressed pointed to the importance of equity while PRsM highlighted economic incentives.

The sentiment in both sectors was positive "Trust exists and is a crucial element is healthcare, an essential need". Surprisingly PRsM described trust as a comprehensive, ongoing encounter, while PBsM referred to it as an acute episode or a "snapshot", explained by the episode of informed consent prior to surgery.

Study limitations

Although we approached managers from various medical centers in the public and the private sector, the convenience sampling method may have limited our ability to generalize our findings, and the small sample may have influenced the statistical strength. Additionally, as the managers were approached personally, a social desirability may have affected their answers. Further research may clarify trends that are emerging yet non significantly, we suggest a to compare our findings with another health system.

Conclusions

Trust is an essential component of healthcare systems and as such should be further nourished and maintained by both patients and care providers. By focusing on manager perspectives, we were able to provide a complementary view to that of patients, yet far from completion. This survey may allow policy makers and opinion leaders to continue building and maintaining trust between patients and care providers. Moreover, it would be interesting to explore whether the Covid-19 breakout that appeared after our survey was already completed, would have an influence on this fragile patient-physician relationship.

Supporting information

S1 appendix. overall perception of trust by service provider or type of expertise (mean)..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250626.s001

S2 Appendix. Perceived understanding and trust of patients in selected operative procedures (mean).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250626.s002

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- Open access

- Published: 20 July 2023

Indicators of the dimensions of trust (and mistrust) in early primary care practice: a qualitative study

- Allen F. Shaughnessy 1 ,

- Andrea Vicini, SJ 2 ,

- Mary Zgurzynski 4 ,

- Monica O’Reilly-Jacob 3 &

- Ashley P. Duggan 1 , 5

BMC Primary Care volume 24 , Article number: 150 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1524 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Trust occurs when persons feel they can be vulnerable to others because of the sincerity, benevolence, truthfulness and sometimes the competence they perceive. This project examines the various types of trust expressed in written reflections of developing healthcare clinicians. Our goal is to understand the roles trust plays in residents’ self-examination and to offer insight from relationship science to inform the teaching and clinical work for better trust in healthcare.

We analyzed 767 reflective writings of 33 residents submitted anonymously, to identify explicit or implicit indicators attention to trust or relationship development. Two authors independently coded the entries based on inductively identified dimensions. Three authors developed a final coding structure that was checked against the entries. These codes were sorted into final dimensions.

We identified 114 written reflections that contained one or more indicators of trust. These codes were compiled into five code categories: Trust of self/trust as the basis for confidence in decision making ; Trust of others in the medical community ; Trust of the patient and its effect on clinician ; Assessment of the trust of them exhibited by the patient ; and Assessment of the effect of the patient’s trust on the patient’s behavior .

Broadly, trust is both relationship-centered and institutionally situated. Trust is a process, built on reciprocity. There is tacit acknowledgement of the interplay among what the residents do is good for the patient, good for themselves, and good for the medical institution. An exclusive focus on moments in which trust is experienced or missed, as well as only on selected types of trust, misses this complexity.

A greater awareness of how trust is present or absent could lead to a greater understanding and healthcare education for beneficial effects on clinicians’ performance, personal and professional satisfaction, and improved quality in patients’ interactions.

Peer Review reports

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

-- From The Rock , T.S. Eliot

In healthcare, the yearning to be seen as an individual is particularly poignant because the relationship between clinician and patient is in many ways so intimate—and, at the same time, the learning and practice of relationships in clinical care can feel so distant. The vulnerability of sharing, with the resulting generation of wisdom, can get lost in biomedical measures, in knowledge, and information. In this project, we explore written reflections from developing healthcare clinicians to offer insight into the teaching and clinical practice of trust. Our project and data offer practical insight for teaching and improving trust in healthcare, including intrapersonal trust (trusting oneself) and interpersonal/relational trust (trusting colleagues and patients) and organizational trust (trusting healthcare systems and structures). We address implications of trust from relationship science and human communication research as well as practical implications of trust.

Across disciplines, trust is conceptualized as entailing some level of risk, uncertainty, or willingness to be vulnerable, and trust creates an expectancy about future behavior since a person must assume that a person, group, or organization will behave in a particular way [ 1 ]. Trust, at its core, is when a person feels they can be vulnerable to others because of the sincerity, benevolence, truthfulness and sometimes the competence they perceive of others [ 2 ]. People may extend trust to individuals, organizations, or societal structures that could act to further our interests or protect what we see as vulnerable. Trust often involves a transfer of power to a person or to a system [ 3 ]. Trust in organizations involves not only competence, but also openness and honesty, concern for stakeholders, reliability, and a sense of attachment or values that are aligned with our desires [ 4 ]. Healthcare professionals and patients know well when they experience trust in a healthcare interaction and system; they can rely on their healthcare team to be at their service and committed to promoting well-being [ 5 ].

Trust is usually bidirectional and relationship-based, built over time and across a series of interactions. Patients who experience high trust are less likely to second guess what healthcare professionals suggest as diagnostic follow-up, therapy, or lifestyle advice; an additional expert opinion might still be needed, but even that is an expression of a trust-based relationship [ 6 ]. Trust is usually vigilant and includes critical discernment, not implying dependence or surrendering independence [ 2 ]. Clinicians who feel they can trust and are trusted by patients feel recognized and appreciated for their clinical knowledge and competence and are confirmed in their ability to promote health, well-being, and flourishing in patients and within society [ 7 ]. Trust is a commodity that cannot be presupposed, but can be examined and promoted [ 8 ]. Trust also involves systemic and structural dimensions such that increasing trust in healthcare contexts can be beneficial in multiple ways—subjective and objective, relational and social, financial and organizational [ 9 ].Trust is a value in itself, and trust facilitates deeper relational interactions, continuity of care, quality of services provided, and facilitates opportunities for containing healthcare costs; on the other hand, when trust is lacking, dissatisfaction, disappointments, and frustrations appear to dominate and compromise healthcare experiences [ 2 ].

The effect of trust on the provision and receipt of healthcare is well documented. Better trust of physicians by patients lowers their perception of risk of treatment [ 10 ]. Patients with diabetes who trust their physician are more likely to follow suggested self-care guidelines [ 11 ]. Trust is also both a critical ingredient to and result of effective shared decision-making [ 12 , 13 ]. Patients who do not trust their physicians are more inclined to make their own decisions rather than using a shared decision approach [ 14 ].

This article focuses on trust in an inductive way by examining various types and dimensions of trust identified in reflective writings from developing healthcare clinicians attending to their experiences interacting with patients, colleagues, and staff. Written reflections offer insights into their understanding of trust and how trust impacted them. Our goal is to understand the various roles trust play in residents’ self-examination and to offer implications for teaching and improving trust in healthcare.

This project began as an effort to introduce reflective writing and to improve reflective writing skills of family medicine residents in a single residency in the United States. The 33 residents were given regularly scheduled time to write these reflections into an internet-based database. They were not required to write the reflection at this time but could access the database at any time. They were not given a prompt but were asked to give each entry a title and link to clinical topic where appropriate. The reflections were not graded or evaluated in any way and were available only to the resident. Most (94%) of the residents participating in this project were women and were at all levels of residency education. This percentage is consistent with 94% of the Family Medicine residents being women. A total of 767 reflections were written over 18 months and were collected for this project.

IRB approval and ethical protections for participants

We obtained Institutional Review Board approval from two institutions where the researchers are affiliated. First, the project was approved as exempt and with waiver of written informed consent by the Cambridge Health Alliance Institutional Review Board (first author’s affiliation) and then by Boston College (other authors’ affiliation) under the classification of education research. All methods were carried out in accordance with regulations that apply to exempted research. Reflection entries were de-identified by a researcher not involved with participants (AD) before the analysis, other than being categorized by year of training. This analysis was performed after all participants graduated from the training program. In addition, examples from the reflections in this paper are aggregated or paraphrased in a way to disguise identification with a specific residency or medical resident.