An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Commun Integr Biol

- v.16(1); 2023

- PMC10461512

On power and its corrupting effects: the effects of power on human behavior and the limits of accountability systems

Tobore onojighofia tobore.

Independent Scholar, Yardley, PA, USA

Power is an all-pervasive, and fundamental force in human relationships and plays a valuable role in social, political, and economic interactions. Power differences are important in social groups in enhancing group functioning. Most people want to have power and there are many benefits to having power. However, power is a corrupting force and this has been a topic of interest for centuries to scholars from Plato to Lord Acton. Even with increased knowledge of power’s corrupting effect and safeguards put in place to counteract such tendencies, power abuse remains rampant in society suggesting that the full extent of this effect is not well understood. In this paper, an effort is made to improve understanding of power’s corrupting effects on human behavior through an integrated and comprehensive synthesis of the neurological, sociological, physiological, and psychological literature on power. The structural limits of justice systems’ capability to hold powerful people accountable are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Scholars across different disciplines have tried to define power [ 1 ]. It has been defined as having the potential to influence others or having asymmetric dominion over valuable resources in a social relationship [ 2 , 3 ]. It has also been defined as the capacity of people to summon means and resources to achieve ends [ 1 ]. In addition, it has been described as having the disposition and means to asymmetrically impose one’s will over others and entities [ 4 ]. Taken together, power can be defined as being able to influence others due to asymmetric dominion of resources, the capability to summon means to achieve ends, and being able to impose one’s will over others and entities. Power is an all-pervasive and fundamental force in human relationships and plays a valuable role in social, political, and economic interactions [ 4 ]. It plays an important role in many aspects of human life, from the workplace, and romantic relationships, to the family [ 5 , 6 ]. Power is dynamic, and it resides in the social context, and should the social context change, power relations tend to change as well [ 1 ]. There are different types of power and their effective utility lies within a limited range [ 7 ].

Power differences within groups enhance group functioning by promoting cooperation [ 8 ], creating and maintaining order, and facilitating coordination [ 9 ]. Most people want to have power and there are many benefits to having power. People desire power to be masters of their own lives and to have greater autonomy over their fate [ 10 , 11 ]. Position in the dominance hierarchy is correlated with both general and mental health [ 12 ] and associated with reproductive access, grooming from others as well as preferential food and spaces [ 13 ]. Elevated power promotes authentic self-expression [ 14 ], reduced anger, greater happiness, and positive emotions/mood [ 5 ]. In contrast, low power is associated with negative emotions (discomfort and fear) [ 15–17 ], increased stress, and alcohol abuse [ 18 ].

Evolutionarily, dominance and perceptions of power cues are associated with body size. Indeed, social status can be attained through two pathways: prestige or dominance [ 13 ]. Height is positively related to dominant status [ 19 ]. High-status prestigious and dominant individuals tend to be judged as taller, and taller individuals as higher in prestige and dominance [ 20 ]. Also, dominant high-status people tend to be judged as more well-built, and more well built individuals as dominant [ 20 ]. Power and status (i.e., respect and admiration) represent different dimensions of social hierarchy but are positively correlated [ 21 ]. Power is causally connected to status because power can lead to the possession of status and status can result in the acquisition of power [ 21 ]. Power from social status is a central and omnipresent feature of human life and they are both correlated in terms of control of institutions, political influence, material resources, and access to essential commodities [ 22 , 23 ]. From an evolutionary perspective, high status is sought because reproductively relevant resources, including territory, food, mating opportunities, etc. tend to flow to those high in status compared to those low in status [ 24 ].

Having power affects the human body physiologically, neurologically, and psychologically. Power is linked with neurological alterations in the brain. Indeed, power triggers the behavioral approach system [ 2 , 25 ] while powerlessness undermines executive functioning [ 17 ]. Low social power state compared to high or neutral power is associated with significantly reduced left-frontal cortical activity [ 26 ]. Animals research suggests that dominance status modulates activities in dopaminergic neural pathways linked with motivation [ 27 , 28 ] and the amygdala and dopaminergic neurons play a major in responding to social rank (an individual’s social place as either subordinate or dominant in a group), and hierarchy signals [ 29 ]. Brain recordings indicate that loss of social status induces negative reward prediction error which via the lateral hypothalamus triggers the lateral habenula (anti-reward center), inhibiting the medial prefrontal cortex [ 30 ]. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), observing a powerful individual differentially engaged the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, regions related to the amygdala (emotional processing), medial prefrontal cortex (social cognition) indicating a neural processing of social ranking and status in humans [ 31 , 32 ]. Furthermore, using fMRI, perceived social status was found to differentially modulate ventral striatal responses when processing social rank cues or status-related information [ 33 ]. Results from fMRI indicate that low social status is associated with diminished gray matter size in the perigenual area of the anterior cingulate cortex, which is associated with adaptive physiological, emotional, and behavioral reactions to psychosocial and environmental stressors [ 34 ]. Approach related motivation is linked to increased left-sided frontal activity in the brain, and the neural evidence of the relationship between approach related motivation and power was confirmed using EEG, which found that elevated power is connected with increased left-frontal activity in the brain compared to low power [ 35 ].

Also, power is linked with endocrinal and physiological changes. Testosterone increases dominance and other status-seeking behaviors [ 36 , 37 ] and this effect of testosterone on dominant behavior may be modulated by psychological stress and cortisol [ 38 ]. High testosterone has been identified as a factor that promotes the development of the socially destructive component of narcissism in powerholders [ 39 ], and power interacts with testosterone in predicting corruption [ 40 ]. Posing in high-power nonverbal displays causes physiological changes including increased feelings of power, a decrease in cortisol, increases in testosterone, and increased tolerance for risk compared to low-power posers [ 41 ]. Animal studies indicate that low social rank or subordination promotes stress activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and may modulate the brain’s dopaminergic function [ 42 ]. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that tryptophan enhances dominant behavior indicating that serotonin may promote dominance in humans [ 43 , 44 ]. Furthermore, results from experiments suggest that high social power elicits a benign cardiovascular response suggestive of a well-ordered cardiovascular pattern while low social power elicits a maladaptive cardiovascular response pattern which is suggestive of an inefficient cardiovascular pattern [ 45 ]. Power holders who may lose their privileged position displayed a maladaptive cardiovascular pattern, marked by low cardiac output (CO) and high total peripheral resistance which is suggestive of feeling threatened [ 46 ]. Evidence suggests that higher social status is associated with approach-type physiology compared to lower social status [ 47 ].

Power has a monumental effect on the behavior of the powerholder [ 2 , 48 ]. The corrupting effect of power is well known and has been a topic of interest for centuries to scholars. Plato advocated for the exclusion from office with consequential power, individuals who may misuse power for self-serving reasons, and only those with a well-developed sense of justice be allowed to wield power [ 49 ]. In recent decades, the corruption cases involving CEOs of large corporations, entrepreneurs, politicians, and autocrats/dictators have sparked both scholars’ and public interest in the corrupting effects of power [ 50–55 ] and this has triggered significant research into the effects of power on human behavior. Still, the full extent of power’s effect on behavior is not well understood. The monumental role that power plays in human interactions and life makes the need to better understand its effect on behavior both in powerholders and subordinates extremely important.

The objective of this paper is to elucidate the many corrupting effects of power or the need for power on human behavior as well as the structural limits of systems to hold powerholders accountable.

2. The corrupting effects of power or the need for power on human behavior

2.1. power is addictive.

There is evidence of addiction to the power derived from celebrity and fame [ 56 ]. The addictive effect on the powerholder promotes the need to engage in efforts to hold on to and accumulate power [ 57–59 ]. Aging, envy, and fear both conscious and unconscious of retaliation for previous acts may contribute to power’s addictiveness [ 58 ]. Efforts to hold on to power perpetually play a key in the practice of nepotism, factional struggle by powerful elites, cronyism, and dynastic succession [ 60–62 ].

Power abuse disorder has been coined as a neuropsychiatry condition connected to the addictive behavior of the power wielder [ 63 ]. Arguments have been made on the relationship between power addiction and dopaminergic alterations [ 63 ]. Indeed, changes in the dopaminergic system have been implicated in drug addiction [ 64 ] and research on animals suggests that dominance status modulates activity in dopaminergic neural pathways linked with motivation [ 27 , 28 ]. Evidence suggests that areas of the brain linked with addiction including the amygdala and dopaminergic neurons play a major in responding to social rank, and hierarchy signals [ 29 ]. Multiple lines of evidence from animal studies indicate that dopamine D2/D3 receptor density and availability is higher in the basal ganglia, including the nucleus accumbens, of animals with great social dominance compared to their subordinates [ 28 , 65 , 66 ]. Animal studies suggest that following forced loss of social rank, there is a craving for the privileges of status, leading to depressive-like symptoms which are reversed when social status is reinstated [ 30 , 67 ].

2.2. Power promotes self-righteousness, moral exceptionalism, and hypocrisy

Research indicates that powerful people are more likely to moralize, judge, and enforce strict moral standards on others while engaging in hypocritical or less strict moral behavior themselves [ 68 ]. In other words, powerful people often act and speak like they are sitting on the right hand of God to others especially subordinates while engaging in even worse unethical behavior. Being in a position of power with the discretion to apply punishment or reward to others allows the powerholder the freedom to do as they like or act inconsistently in so far as it serves their interests. This means powerholders are in a position to not necessarily practice what they preach with little or no consequences. Furthermore, being in a position to judge or take punitive action against others for their perceived moral failings may promote a false sense of moral superiority. This self-righteousness can create a misguided sense of probity and messianic zeal which can lead to poor decisions and outcomes. One takeaway from the relationship between power, self-righteousness, and hypocrisy is that power inhibits self-reflection or introspection.

This moral exceptionalism and hypocrisy also exist at the national and international levels. Powerful Western nations typically moralize and lecture about the rule of law, ethics, and democracy to other nations while hypocritically violating the same rules when it suits them or supporting allies that flagrantly violate the same rules [ 69–72 ].

Furthermore, mob action whether virtual or not is usually triggered by perceived injustice, a violation of societal norms, and unfair practices in the criminal justice system that undermine public institutional trust and confidence [ 73–76 ]. Placing wrongdoing on someone puts them (the wrongdoer) in a weaker power position socially which makes them vulnerable. With the power dynamics or balance tilted in the mob’s favor, the perceived injustice or wrongdoing envelopes the mob in an umbrella of sanctimony empowering them to act with impunity, and vigilantism by engaging in moral denunciations, bullying, destruction of property, and even lynching and other forms of violence toward the wrongdoer [ 77–79 ].

2.3. Power decreases empathy and compassion

Power decreases empathic concern [ 80 ] and is associated with reduced interpersonal sensitivity [ 81 ]. Research indicates that powerholders may experience less distress and less compassion as well as exhibit greater autonomic emotion regulation when faced with the pain of others [ 82 ]. Evidence indicates that elevated power impedes accurate understanding of other people’s emotional expressions [ 9 , 83 ] and is linked with poorer accuracy in emotional prosody identification than low power [ 84 ]. Elevated power is associated with heightened interest in rewards while low power is associated with increased attention to the interest of others [ 2 , 48 , 85 ].

Using transcranial magnetic stimulation, motor resonance which is the activation of similar brain pathways when acting and when observing someone act, implemented partly by the human mirror system was decreased in high-power holders relative to low-power holders [ 81 ]. Evidence suggests a linear relationship between the motor resonance system and power in which increasing accumulation of power is connected to decreasing levels of resonance [ 81 ]. This change might be one of the neural mechanisms that underlie power-induced asymmetries in social interactions [ 81 ].

Also, higher socioeconomic status is associated with reduced neural responses to the pain of others [ 86 , 87 ]. In contrast, a lower socioeconomic level is associated with higher compassion, being more attuned to the distress of others [ 88 , 89 ] and more empathically correct in evaluating the emotions of other people [ 90 ] compared to upper-socioeconomic class. High status is associated with exhibiting less communal and prosocial behavior and decreased likelihood of endorsing more egalitarian life goals and values compared with those with low status [ 91 ]. In addition, higher-class people are more likely to endorse the theory that social class is steeped in genetically based (heritable) innate differences than lower-class people and display reduced support for restorative justice [ 92 ].

2.4. Power promotes disinhibited behavior and overconfidence

Elevated power is associated with disinhibited behavior, increased freedom, and heightened interest in rewards while low power is associated with inhibited social behavior [ 2 , 48 , 85 ]. Power is associated with optimism and riskier behavior [ 93 ] and it enhances self-regulation and performance [ 94 ]. It energizes, speech, thought, and action and magnifies confidence, and enhances self-expression [ 14 , 25 ]. Power elevates self-esteem and impacts how people evaluate and view themselves in comparison to others [ 25 , 95 ]. Elevated power particularly in narcissistic individuals results in significant overconfidence compared to individuals in a low state of power [ 96 ].

Power increases the illusion of control over outcomes that are outside the reach of the powerholder [ 97 ]. It distorts impressions of physical size with the powerful exaggerating their height and feeling taller than they actually are [ 98 ], underestimating the size of others, and the powerless overestimating the size of others [ 99 ].

2.5. Power promotes unethical behavior and entitlement

Power promotes feelings of entitlement [ 100 ] and powerholders are not often cognizant of their violation of basic fairness principles [ 25 ]. Evidence from experiments using fMRI indicates that power promotes greed by increasing aversion to receiving less than others and reducing aversion to receiving more than others [ 101 ]. Powerholders, particularly pro-self-individuals, displayed decreased response in the right and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, indicating a weaker restrain of self-interest when processing receiving more than others [ 101 ]. The need for power is significantly and positively correlated with narcissism [ 102 , 103 ]. Power amplifies the tendency of self-focused goals to result in self-interested behavior [ 104 ] and may cause people to act unethically in their self-interest [ 50–52 , 105 ]. Powerful people tend to move in the same circles, giving them access, and increased likelihood of having relationships with other powerful people and these relationships may foster unethical behaviors including quid pro quo, nepotism/favoritism, cronyism, mutual protection against threats, ignoring or bypassing of due process, conflict of interests and corruption.

Physical attractiveness influences people’s social evaluations of others and attractive people enjoy benefits in terms of perceived good health, power, economic advantage, confidence, trust, perceived intelligence, and popularity [ 106–112 ]. Research suggests that the power of perceived attractiveness is associated with increased self-interested behavior and psychological entitlement [ 113 ]. Furthermore, power gained from improved physical appearance/attractiveness, increased attention, improved self-image, and self-confidence following bariatric surgery weight loss is linked to increased separation/divorce [ 114–116 ]. This suggests that power from improved physical appearance and attention following bariatric surgery may promote entitlement, narcissism, and self-interested behavior.

Power makes powerholders feel special, invincible, and above the rules. Indeed, car cost predicts driver yielding to pedestrians with more expensive car drivers less likely to yield to pedestrians at a crosswalk [ 117 ]. While driving, individuals of higher-class are more likely to break the law compared to lower-class individuals and are more likely to cheat and lie and display unethical decision-making tendencies than lower-class individuals [ 118 ].

2.6. Power promotes aggressive and dehumanizing behavior

Power promotes dehumanization, which is the process of rejecting essential components of “humanness” in others and seeing them as animals or objects [ 119 , 120 ] while powerlessness leads to self-dehumanization [ 121 ]. Power promotes the objectification of others [ 122 ] and increases the tendency to disparage and engage in harmful behavior toward others including bullying, autocracy, and manipulation [ 123–125 ].

Also, elevated power is associated with manipulative and contemptuous behavior toward people with low power by devaluing their worth [ 126 ]. It is associated with demeaning, and dehumanizing behavior toward others with low power, with more power resulting in more demeaning behavior [ 127 , 128 ]. Notably, individuals in high power but lacking in status (e.g., prison guards, soldiers) display increased interpersonal conflict and demeaning behaviors [ 127 , 129 ]. Furthermore, research indicates that a powerholder’s threat assessment elicits escalation or confrontational behaviors toward subordinates and de-escalation or submissive behaviors toward higher-status or dominant superiors [ 130 ]. In defense of their ego, power coupled with feelings of incompetence can promote aggressive behavior [ 131 ].

One key reason for the emergence of this demeaning and dehumanizing behavior of powerful people is their false sense of superiority over individuals with low power. This is reinforced by the excessive praise and groveling of subordinates and the fact they are they have the authority to impose negative consequences on others, and few are bold enough to challenge them out of fear of retaliation. This feeling or sense of superiority is particularly more pronounced in an environment where there is little to no oversight over their behavior, and it can gradually divorce them from reality. Jokes that were once considered mundane or innocuous before they acquired power or accumulated more power are suddenly perceived as insults. Anyone who dares to argue for a different position, especially one that suggests incompetence, is perceived as a threat that needs to be eliminated.

Moreover, experimental evidence indicates that asymmetric power differences can promote extortionary [ 132 ] and exploitative behaviors [ 133 ]. The power asymmetry between human traffickers and the young, vulnerable people they exploit explains the sense of entrapment of survivors, why the traffickers can engage in dehumanizing and demeaning behavior, violence, and forced labor with impunity, without any sense of guilt, remorse, or regard for the welfare of the trafficked individuals [ 134–136 ]. The power asymmetry between police officers and vulnerable people in their community (e.g., sex workers, the homeless, marginalized people, and minorities) explains to some extent the increased likelihood of police abuse toward members of those communities [ 137–139 ]. There are many stories of seemingly normal people enslaving and using violence against their maids [ 140 , 141 ]. Usually, people who become trapped in these situations are foreigners with no legal documentation or with legal papers connected to their work for that employer. The significant asymmetric power difference between the employer and the maid makes the maid vulnerable to abuse. Anyone in the position of employer can easily become abusive toward the vulnerable maid in an environment where negative consequences for their actions are nonexistent.

This same power asymmetry which may lead to bullying, intimidation, and exploitation can be observed between nation-states. Just like individuals, as disparities in economic and military power widen between countries, the larger and more powerful states may engage in bullying neighboring states through trade and other means including threats of war if they act outside of ways the more powerful nations prefer.

2.7. Power sexualizes social interactions

Power is linked with sex [ 142 ]. It elicits romantic desire from individuals of the opposite sex [ 143 ] and may play an important role in sexual objectification [ 144 , 145 ]. Evidence suggests that subordinates view their leaders as significantly more physically attractive [ 146 ] and power increases expectations of sexual interest from subordinates biasing social judgment and sexualizing social interactions which might lead to sexual harassment [ 147 ].

Power is positively associated with sexual infidelity because of its disinhibiting effects on behavior and increased self-confidence to attract partners [ 148 , 149 ]. Its disinhibiting effect also amplifies the appetite for both normative or counter-normative forms of sexuality and makes powerful men seem more desirable and attractive which may increase their access to potential sexual opportunities [ 148 ]. Power asymmetry between educators and students increases the potential for sexual misconduct and abuse [ 150–153 ].

Boundary setting, vigilance, and regular training for teachers and organizational supervisors on the sexualizing effect of power on social interactions should be put in place to reduce the incidence of sexual harassment and inappropriate relationships.

2.8. Power hinders perspective taking and cooperation

Low power is associated with increased cooperation [ 154 ] while elevated power may hinder perspective-taking [ 83 ] and increase the preference for the preservation of psychological distance from people with low power [ 126 , 155 ]. An fMRI study showed that powerholders display reduced neural activation in regions associated with cognitive control and perspective-taking (frontal eye field and precuneus) [ 101 ]. Results from electroencephalogram (EEG) suggest that power taints balanced cooperation by reducing the power holder’s motivation to cooperate with subordinates [ 156 ]. Also, power reduces conformity to the opinion of others [ 9 , 157 ] and is associated with discounting advice, due to overconfidence [ 158–160 ] as well as being less trusting [ 161 ] and this can hamper cooperation.

2.9. Power, judgment bias, and selective information processing

Power promotes the need for less diagnostic information about others and increases vulnerability to using preconscious processing and stereotypical information about others [ 162–165 ]. It increases implicit prejudice (racial bias) and implicit stereotyping [ 166 , 167 ]. Evidence suggests that elevated power is associated with automatic information processing, while low power is associated with restrictive information processing [ 2 , 48 , 85 ]. Power modulates basic cognition by promoting selective attention to information and suppressing peripheral information [ 168 ]. Results from an experiment found that neural activity in the left inferior frontal gyrus, an area linked with cognitive interference, was diminished for individuals with elevated power relative to those with low power suggesting that elevated power may reduce cognitive interference [ 169 ].

Elevated power promotes social attentional bias toward low-power holders [ 170 ]. It also promotes self-anchoring attitudes, traits, and emotions which is the use of the self as the gold standard or reference point for evaluating or judging others [ 171 ]. In other words, for powerful people good or bad traits and attitudes are viewed using themselves as a reference without regard for the individuality of others. Power modulates the process of making tough decisions [ 172 ] and it is associated with excessive confidence in judgment which may turn out to be less accurate [ 158–160 ].

2.10. Power confers credibility

Credibility carries power and power confers credibility relative to those with less power [ 173 , 174 ]. The claims or assertions of a person with power or high status are typically treated with respect. In contrast, the claims of individuals at the lower end of the power structure are often doubted until investigated, and that is if anyone even bothers to investigate thoroughly and fairly. Consider the Filipino maid working in Kuala Lumpur, the Ethiopian or Indian lady working as a maid somewhere in the Middle East, or the young girl from Calabar working as a maid for a rich family in Lagos. Typically, maids depend on their employers not just for housing and food, but for their immigration status as well. Who will believe her if she accuses her boss of sexual assault or if her boss falsely accuses her of stealing? Similarly, if a police officer, particularly one with an unblemished record, plants drugs on an ex-convict, who is going to believe the ex-convict? The more he protests, the guiltier he appears.

In the workplace, the significant power asymmetry between an employee and their supervisor gives their supervisor significant credibility. A report from a supervisor, whether true or false, carries considerable weight because of the credibility they automatically have relative to their employee.Disturbingly, the supervisor’s powers do not end within the four walls of the organization; employers at other organizations may depend on the assessment and opinion of the supervisor to pass judgment on a person without any regard for the possibility of their prejudice.

2.11. Power and victimhood

Not all victims are after power but being a victim can come with significant power [ 175–179 ]. Victims are seen as socially and morally superior and deserving of social deference [ 180 , 181 ]. Victimhood proffers psychological and social benefits and allows one to achieve greater social or political status [ 181 , 182 ]. This makes victimhood attractive.

The need for power significantly predicts competitive victimhood, which is a tendency to see one’s group as having dealt with more adversity relative to an outgroup [ 177–179 ]. Victims, especially those who appear weak or who are lower in the power structure, are seen as needing protection. In contrast, the accused are seen as aggressive and dangerous. The power derived from victimhood can be misused, and many people employ it for retribution. Being a victim or feeling wronged may result in a sense of entitlement and selfish behavior [ 182 ].

While it is important to protect victims in all cases, care must be taken to ensure that negative consequences are not applied reactionarily to the accused. Negative actions taken against the accused before a fair and thorough investigation is conducted make the exploitation of victimhood attractive. Even if the allegations are proven to be false, public outrage and adverse opinion can lead to irreparable reputational damage and financial loss. The noble pursuit of an equal and fair society must never blind us to the dangers posed by the exploitation of the power of victimhood to elicit outrage and pursue retribution.

2.12. Power and gossip

Gossip tends to be negative, and people engage in it for many reasons including for socializing, to gain influence and power, due to perceptions of unfairness, feelings of envy, jealousy, and resentment, to get moral information, creation and maintenance of in-groups and out-groups, indirect aggression, and social control [ 183–186 ]. Gossip has self-evaluative and emotional consequences [ 187 ].

Spreading gossip can be an effort to exercise power [ 188 ]. Lateral gossip or gossip between peers of similar power can help people get information and support from others. However, upward gossip which is gossip with people in higher power who have formal control over resources and the means to take action may be used by those in lower power to inform and thereby gain or exert influence [ 189 ]. Reputation and gossip are intertwined, and gossip can be used for status enhancement and wielded as a weapon against others [ 190 ].

The need for power may cause people to engage in gossiping and a person with a listening and believing audience of one has the power to destroy another person’s reputation and adversely affect their life.

2.13. Power and ambition

Ambition, defined as the persistent or relentless striving for success, attainment, and accomplishment or a yearning desire for success that is committedly pursued [ 191 ], is crucial to success in diverse social contexts. Ambition is positively associated with educational attainment, high income, occupation prestige, and greater satisfaction with life [ 192 , 193 ]. Power and ambition are inextricably linked because people with power and those who aspire for power are typically very ambitious. Ambition is critical in acquiring, accumulating, and retaining power.

Ambition, while critical to being successful [ 193 , 194 ] and an immensely powerful motivator, can also be a potent self-destructive tool and a vice that may cause people to inflict suffering on others in the pursuit of personal glory and gains [ 191 ]. Overreaching ambition breeds greed and can quickly slip into dishonesty [ 195 , 196 ]. Ambition and greed encourage both destructive competition and acquisitiveness as a way to affirm superiority over others [ 197 ]. Excessive ambition can be a curse as it can lead to extremism due to obsessive passion [ 198 ] and make people feel dissatisfied even with their accomplishments because their desires are insatiable or can never be fully achieved [ 191 , 199 ]. Ambition can make a person falsely believe that they are special, destined for greatness, or cut from a different cloth. While this feeling can be helpful in the pursuit of seemingly challenging goals, it can lead to unethical behavior [ 195 , 200 ].

In efforts to retain power and status, ambition can make people abuse power and for those trying to acquire power, it can make them go to extra lengths without regard for the negative consequences. Indeed, excessive ambition in powerful people or excessive ambition for power, fame, and prestige can blur the lines of acceptable behavior, and when those lines are crossed, it can result in actions that are fraudulent, illegal, and catastrophic [ 53 , 201–204 ]. Ambition can cause a person to act recklessly by exaggerating both reality and possibilities, as well as by downplaying important risks that may prove fatal. When people begin to see the end goal as the only thing that matters, they cut corners, and lose sight of ethics and the monumental danger their actions pose to others. In line with the dangers of ambition, Machiavelli argued that ambition and greed are the causes of chaos and war [ 197 ].

3. Power, and the structural limits of accountability systems

In most social systems, people who are lower in the power structure can only get misconduct addressed by a third party that has some power to punish, hold accountable, or overturn the judgment imposed by the powerholder. For example, an employee with allegations of wrongdoing by their manager, who is the CEO or President of the organization may not be able to hold them accountable within the organization. Their case may be best addressed by the court system, a third party with the authority to hold the organization accountable. Seeking fair redress or accountability within the organization can be difficult or even impossible because those in power are not motivated to change their behavior. So, unless the employee is willing to take their case to court (or another authority with a similar power to hold the employer accountable, like the press), there may not be a way for them to seek redress. Unfortunately, a third party is often not present, and even if one exists, it may not be impartial or easily accessed by people lower in the power structure.

Furthermore, there is a limit to the number of third parties or higher authorities in any social system for seeking redress. At some point, there must be a supreme authority whose ruling is final and irreversible. In a nation-state, the final authority may be the apex or Supreme Court. In sports, a ruling body makes final decisions. In the global arena, international courts have the final say against individuals or nations that violate relevant laws. Importantly, if the judgment of the top authority is incorrect or unjust, the only option is to accept the ruling until the issue is revisited. Also, the higher you must go in efforts to seek redress for wrongdoing, the less accessible it is for people who are lower in the power structure, and the fewer cases that are worthy of being taken on. These obstacles mean that many cases of power abuse go unchecked, unfair judgments are often passed, and miscarriages of justice occur at all levels. In addition, falsehoods about people and events sanctioned or protected by the powerful are carried as truth into posterity.

So, the means for holding accountable or checking the actions of the powerful by those with low power are limited not just by corruption and problems of access but by the structural limits of accountability/justice systems.

4. Discussion

The role of power in our lives is all-pervasive, and complex, and its effects extend to both intentional and unintentional acts of the powerholder [ 4 ]. The current review is different from previous works and contributes significantly to our understanding of power because of its extensiveness and broad synthesis of the literature on power from a wide range of disciplines including biology, neuroscience, psychology, behavioral sciences, sociology, and anthropology. One key lesson from this work is that the effects of power extend beyond the behavioral changes that are visible as power interacts with the neurological, neuroendocrine, psychological, and physiological processes of the power holder.

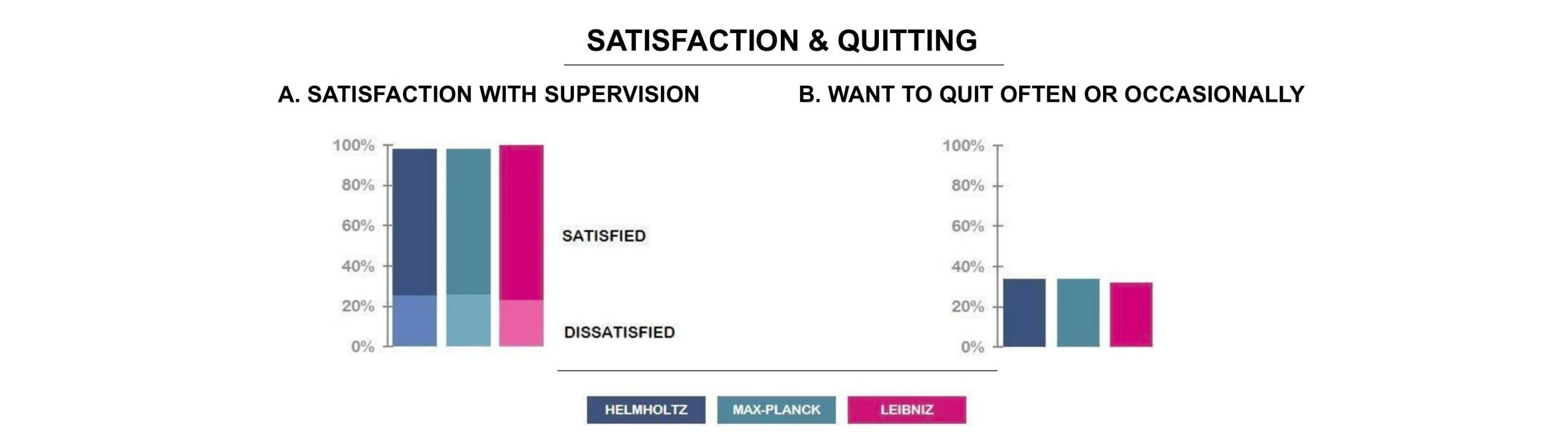

As noted in Figure 1 , power can dramatically change ordinary people’s behavior causing them to abuse it thereby making cumulative small mistakes that reach a dangerous threshold or a single significant mistake that ultimately leads to their loss of power. The narcissist personality model described in Figure 2 is different from the classical Model (Non-narcissist). The grandiose narcissist is assertive and extraverted and distinguished by their sense of entitlement, overconfidence, high self-esteem, feelings of personal superiority, self-serving exploitative behavior, impulsivity, a need for admiration and dominance, and aggressive and hostile behavior when threatened or challenged [ 205–208 ]. Grandiose narcissists are more likely to seek and achieve positions of power in organizations [ 209–213 ], but they are more likely to abuse their power, pursue their interests at the expense of the organization [ 207 , 214–217 ], disregard expert advice causing them to make poor decisions [ 205 ].

Classical process of power corrupting behavior leading to power loss.

Narcissist model of power corrupting behavior leading to power loss.

Another key takeaway from this paper is that no human being is completely immune to the corrupting effects of power. Results from a lab experiment suggest that power amplifies people’s dispositions in which powerful people with a firm moral identity are less likely to act in self-interest relative to those with a shaky moral identity [ 105 ]. One argument against the conclusions of this experiment is that power roles in lab experiments typically do not involve consequential outcomes or real decisions [ 4 ] and may not translate to power experiences in the real world [ 5 ]. Furthermore, the effects of power may change when it involves genuine interpersonal interactions compared to the arbitrary assignment into power groups, hypothetical scenarios, or anticipated interactions, as in a lab [ 5 ]. Another argument against this conclusion is the evidence that the virtue of honesty may not protect powerful people from the corruptive effect of power (Bendahan et al., 2015), Even with a strong moral identity, exposure to cash can provoke unethical intentions and behavior [ 218 ]. Even with a strong moral identity, it is still possible that in the presence of a threat to ego or power, seemingly good people with power can abuse power by acting aggressively [ 104 , 131 , 219 ]. Evidence suggests that in efforts to avoid a status or power loss powerful people may be willing to use coercion and go extra lengths even at others ‘expense [ 104 , 219 , 220 ]. Also, appetitive aggression, the nature of lust for violence, is an innate part of human behavior [ 221 ] and humans by nature have a high propensity for proactive aggression, a trait possessed in common with chimpanzees [ 222 ]. Indeed, human hands are evolved for improved manual dexterity and to be used as a club during fighting [ 223 ]. The neurobiology of human aggressive behavior has been extensively studied and includes alterations in brain regional volumes, metabolism, and connectivity in certain neural networks. Subregions of the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, insula, hippocampus, and basal ganglia play a critical role within these circuits and are linked to the biology of aggression [ 224 ]. So, while there are individual differences in propensity to abuse power including the use of violence and aggression [ 225 ], the monumentally corrupting effects of power can ensnare anyone. Taken together, when it comes to power, there are no good or bad people, there are only people.

Organizational social hierarchies play an important role in power abuse. Power hierarchies and pyramidal forms of leadership are integral aspects of social organizations to help create stability and order, but they attract narcissistic individuals [ 226 ] and can be harmful [ 227 ]. In many cases, these hierarchical structures can perpetuate power differences, creating bureaucratic conditions where there are strictly defined roles, with their distinction and importance overstressed. Being an individual with low power in such an environment can be challenging because of powerlessness and powerlessness can lead to self-dehumanization and feelings of worthlessness [ 121 ]. Such an environment can also stymie creativity, particularly for people with low power. Indeed, several lines of evidence indicate that power increases creativity [ 155 , 157 , 228 , 229 ]. However, when the power hierarchy is not fixed, people with low power display a flexible processing style and greater creativity [ 230 ]. So, organizations need to use a mixed model of classical hierarchy that incorporates flat hierarchy as much as possible to ensure that all members feel empowered and have a strong sense of belonging. Notably, an environment where people with low power feel empowered may result in decreased temporal discounting and increased lifetime savings [ 231 ]

It is important to note that there are some valid explanations for some of the behavior that powerholders display. Indeed, powerful people may pay less attention and be more vulnerable to stereotyping because they are attentionally overloaded leading to scarce cognitive resources [ 4 , 163 ]. Power is associated with a greater feeling of responsibility, and this may explain to some extent why it is associated with reduced social distance [ 5 ] Also, there are conflicting reports in the literature regarding the corrupting effect of power on behavior. Power used corruptly may play a vital role in maintaining cooperation in human society [ 8 , 232 ]. Power may not promote intransigence instead it can create internal conflict and dissonance leading to a change in attitude [ 157 ]. Instead of creating social distance, elevated power has been found to be associated with attentiveness in interacting with other people and greater feelings of being close to them relative to low power [ 5 ]. Experimental evidence suggests that high power is associated with more interpersonal sensitivity than low power [ 233 ]. Furthermore, high-status individuals have been found to display more prosocial behavior and to be more generous, trusting, and trustworthy compared to low-social-status individuals [ 234 ]. Power has been found to have no effects on attraction to rewards, which runs counter to the approach/inhibition theory that suggests that power enhances individuals’ interest in rewards [ 235 ]. Also, experimental evidence indicates that power under certain circumstances can result in less risky or more conservative behavior [ 236 ]. These findings indicate that more studies are needed to better understand the effects of power using better experiment designs with larger samples and more real-world studies. It also indicates that power abuse mitigating factors can play a critical role in curbing the corrupting effects of power.

The keys to maintaining and being effective with legitimate power are understanding its corrupting effects, continued relatability, collaboration, respect for peers and subordinates, and humility, which is predictive of positive outcomes [ 237 ]. The corrupting effect of power makes the need for checks and balances important to ensure the proper functioning and success of all individuals of a social group. One of the ways of mitigating power abuse is the consideration of predispositions, proper vetting to select ethical candidates, and training to increase social responsibility in people appointed to positions of power [ 25 ]. Organizational culture can play an important role in mitigating power abuse as it can shape and nurture power holders through values and culture that link power with being responsible [ 238 ]. Appropriate negative consequences must be put in place to deter the abuse of power. More must be done in the selection and training of individuals with power over highly vulnerable people with low power from abuse e.g., children, the institutionalized, etc. Physicians have power over patients in many respects [ 239 , 240 ] and the trend toward shared decision-making [ 241 ] must be strengthened using medical education training of physicians in the appropriate use of power and enactment of patient-centered therapeutic communications [ 242 ]. Boundary setting, vigilance, and regular training for teachers and organizational supervisors on the sexualizing effect of power on social interactions should be put in place to reduce the incidence of sexual harassment and inappropriate relationships. To mitigate the negative effects of the structural limits of accountability systems, allegations of wrongdoing by the powerful should be treated seriously and everyone particularly those in the lower power structure should be guaranteed access and resources to a fair and impartial higher authority for addressing wrongdoing without fear of retaliation. The allowance and development of a robust civil society that can leverage the power of peaceful protests to bring about change are crucial to pushing back on the excesses of power. The continued promotion of universal human rights and the creation of international institutions that hold powerful people accountable for blatant abuse of power is another important tool to deter and reduce the incidence of blatant abuses of power. In the international arena, laws and governing bodies must protect smaller nations from bullying, intimidation, and threats from larger and more powerful nations.

Finally, while intoxicating, power is fleeting, and it goes around. A person with immense power today may be lacking in power tomorrow. In the same vein, a person with little relevance today could ascend to a position of great power tomorrow. This should serve as a warning to everyone with power: always treat others with dignity, respect, and compassion, regardless of their current place in the power structure. As they say, the future is pregnant, and no one knows exactly what it will deliver.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Advertisement

Bullying and the Abuse of Power

- Original Article

- Published: 19 April 2023

- Volume 5 , pages 261–270, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Naomi C. Z. Andrews 1 ,

- Antonius H. N. Cillessen 2 ,

- Wendy Craig 3 ,

- Andrew V. Dane 4 &

- Anthony A. Volk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4475-8134 1

4925 Accesses

2 Citations

19 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Dan Olweus pioneered research on school bullying and identified the importance of, and risk factors associated with, bullying and victimization. In this paper, we conduct a narrative review of the critical notion of power within bullying. Specifically, we discuss Olweus’s definition of bullying and the role of a power imbalance in distinguishing bullying behavior from other forms of aggression. Next, we discuss the changing nature of research on aggression (and the adaptiveness of aggression) throughout the years, the important role of power in these changes, and how the concept of power in relationships has helped elucidate the developmental origins of bullying. We discuss bullying interventions and the potential opportunities for interventions to reduce bullying by making conditions for bullying less favorable and beneficial. Finally, we discuss bullying and the abuse of power that extends beyond the school context and emerges within families, workplaces, and governments. By recognizing and defining school bullying as an abuse of power and a violation of human rights, Olweus has laid the foundation and created the impetus for researching and addressing bullying. This review highlights the importance of examining abuses of power not only in school relationships, but across human relationships and society in general.

Similar content being viewed by others

Theoretical Perspectives and Two Explanatory Models of School Bullying

Adolescent susceptibility to deviant peer pressure: does gender matter.

Associations between Adolescents’ Interpersonal Relationships, School Well-being, and Academic Achievement during Educational Transitions

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Dan Olweus was a pioneer in identifying school bullying as a form of aggressive behavior that was important to research. Contrary to public opinion, Olweus argued that being bullied at school was a harmful behavior as opposed to an acceptable right of passage (Olweus, 1978 , 2013 ). Furthermore, he identified being victimized by bullying as a significant risk factor for child and youth development (Olweus, 1978 ). A recent (October, 2021) search of Google Scholar using the term “school bullying” returned almost one million results, indicating the paradigm-shifting importance of Olweus’s classification of school bullying behavior. Bullying is not a transitory phenomenon, but rather represents a fundamental aspect of human behavior (Volk et al., 2012 ) that had been largely overlooked prior to Olweus’s work (deliberately or not; see REF this issue). In this paper, we conduct a narrative review of relevant theory and evidence to argue that Olweus’s formulation of school bullying laid the foundation for developing critical methodological tools for assessing the aggressive abuse of power, and provided a framework for studying the function of bullying for perpetrators, anti-bullying interventions, and bullying beyond schools in broader societal contexts. We begin by examining the theoretical and historical contexts underlying Olweus’ emphasis on power in bullying. We then discuss how power influences anti-bullying interventions, followed by bullying and power beyond the school context. We end with a general conclusion and suggestions for future research.

Olweus’s Definition of School Bullying

Olweus did not just recognize bullying as a problem; he delineated what remains the most widely used definition of bullying (Olweus, 1993 ). According to one of his last papers on the topic, school bullying requires three criteria: repetitiveness, intentional harm-doing, and a power imbalance favoring the perpetrator (Olweus, 2013 ). These three criteria, however, are not equally important in defining bullying. With respect to repetitiveness, Olweus ( 2013 ) said that he “never thought of this as an absolutely necessary criterion” (p.757), as its inclusion was only to help differentiate bullying from trivial, unharmful incidents. Research has shown that repetitiveness is indeed linked to a greater degree of harm (Kaufman et al., 2020 ; Ybarra et al., 2014 ). But there are also unfortunate examples of single incidents of bullying that are quite harmful (e.g., hurtful or humiliating posts online), having in extreme cases resulted in the death of the victim (Andersson, 2000 ). Thus, repetition may function as a moderator of harm caused by bullying rather than being a primary definitional component (Volk et al., 2014 ).

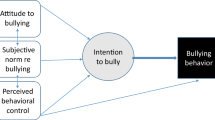

Olweus ( 1993 ) identified intentionality as a critical component of bullying. Intentionality was included in the definition to distinguish between incidents that could cause harm or discomfort (e.g., one child painfully, but accidentally, knocks down another child in a game), but were not intended to be harmful (Olweus, 2013 ). Furthermore, intentionality suggests that youths who engage in bullying actively seek out their target. This definitional component imbues bullying with hostile intent, consistent with the defining criterion of aggression in general. As intent is challenging to measure, recent research has increasingly focused on studying goals instead of intent, given that goals are the tools with which people consciously or unconsciously engage in willful behavior (Dijksterhuis & Aarts, 2010 ). Research has identified several goals associated with bullying (Runions et al., 2018 ; Volk et al., 2022b ). A prominent goal is the accrual of dominance and power (Farrell & Dane, 2020 ; Kaufman et al., 2020 ; Malamut et al., 2020 ; Pouwels et al., 2018a , b ; Pronk et al., 2017 ).

A power imbalance is perhaps the most critical aspect of Olweus’s definition of bullying ( 2013 ) and the aspect he most emphasized in differentiating bullying from other forms of aggression ( 2010 ). Olweus argued that the bully has more power than the person being victimized, which makes it difficult for victims to defend themselves (Olweus, 1993 ). In contrast, bullying is not an aggressive encounter between two individuals of relatively equal power. If the targeted individual can mount an effective defense against the aggressor, this would be considered general aggression rather than bullying (Olweus, 1993 ). Multiple aspects of the power imbalance that defines bullying can be subjective, including the size/degree, nature/type, context, and expression of the power imbalance (Olweus, 2013 ). Furthermore, these can change over time, further complicating the relational nature of power (Pepler et al., 2006 ). The power imbalance can also vary across different bullying interactions and can be related to physical power, popularity, mental acuity, number of allies, and/or localized or broader social dynamics such as classroom norms (Cheng et al., 2011 ; Olweus, 1997 ; Pepler et al., 2006 ; Vaillancourt et al., 2003 ). In cases of cyberbullying, there are even more variables that can potentially influence power imbalances (e.g., technical skills; anonymity; Kowalski et al., 2014 ). It is worth nothing that Olweus viewed cyberbullying as a subcategory of bullying that required greater attention to details such as how power was captured online (Olweus, 2012 ) in order to overcome some of the ambiguities associated with the concept (Olweus & Limber, 2018 ). Heterogeneity in forms of power makes assessing the power imbalance a challenge for researchers, yet its centrality to Olweus’s conception of bullying ( 2013 ) makes it necessary to incorporate. Some researchers have suggested that this imbalance of power reflects changes in the likelihood of costs (e.g., retaliation) and benefits (e.g., status gains) associated with bullying in comparison to other forms of aggression (Garandeau et al., 2014 ; van den Berg et al., 2019 ; Volk et al., 2014 , 2022a , b ).

Why Is Power so Important?

Humans are a deeply social species who evolved large brains to both compete and cooperate with other large-brained individuals to acquire and maintain power (Maestripieri, 2012 ). Similar to many other species, humans have evolved dominance hierarchies that allow for the navigation of power in relationships (Johnson et al., 2012 ). Power plays a pivotal role not only in peer relationships at school, but also across human relationships and society in general (Keltner, 2016 ). In this light, Olweus’s emphasis on the abuse of power captures behavior that is important beyond the school context. Abuses of power lie at the heart of the human experience. Abuses of power characterize, allow for, and can even encourage sibling bullying (Wolke et al., 2015 ), workplace bullying (Vredenburgh & Brender, 1998 ), and intimate partner abuse (Wincentak et al., 2017 ). The evidence is clear that the aggressive abuse of power (i.e., bullying) creates stress that is as toxic to child and adolescent health (Lambe et al., 2019 ) as it is to adult health (Xu et al., 2019 ). Thus, bullying goes beyond Olweus’s assertion of it being a violation of children’s human rights (Assembly, 1989 ; Olweus & Breivik, 2014 ) to being a violation of general human rights, as it also applies to broader levels of social, political, and economic bullying behavior. Illuminating and countering the deliberate abuse of power is the core focus of important recent societal movements, including #MeToo (Kende et al., 2020 ) and BlackLivesMatter (Clayton, 2018 ), as well as movements related to civil rights (Clayton, 2018 ), economic monopolies (Massoc, 2020 ), climate change (Pettenger, 2007 ), the COVID-19 pandemic (Smith & Judd, 2020 ), and growing wealth inequality (Adam Cobb, 2016 ; Kalleberg et al., 1981 ). In all these cases, the difficulty of acknowledging sometimes subjective power imbalances lies at the heart of significant injustices that can take years, if not decades, to recognize and address (Clayton, 2018 ).

The importance of understanding the abuse of power in these domains makes Olweus’s ground-breaking work on schoolyard bullying even more salient in today’s world than it was decades ago. The need to understand the developmental origins of power and its exploitation goes beyond the schoolyard and is central to solving critical social, legal, political, economic, and environmental problems today. Bullying lies at the intersection of these issues, as diverse abuses of power negatively affect the lives of people around the world in many different ways (Elgar et al., 2019 ). The recognition of a power imbalance being central for bullying was not only critical for the definition of bullying (Olweus, 1993 ); it also allowed researchers studying the development of aggression to consider the possibility that aggression is not simply maladaptive (Asarnow & Callan, 1985 ), but rather bullying aggression could potentially be adaptive under certain contexts (Olweus, 1993 ; Volk et al., 2012 , 2022b ). Thus, we next explore the historical and theoretical importance of Olweus’s conceptions of bullying and power for the field of child and youth school aggression and how these conceptions aligned with a shifting view of the adaptiveness of aggression.

The Development of School Bullying and Its Study

An important factor in the increase of research on child and adolescent peer relationships in the 1980s was concerns about the occurrence of aggression and antisocial behavior among youth (including conduct disorder and crime) and the fact that this behavior is almost never conducted by youths alone, but in interactions with peers. In these years, aggression was seen as the primary determinant of peer rejection (dislike), and thus associated with poor social skills and negative repercussions in the peer group (see, e.g., Asarnow et al., 1985 ; Asher & Coie, 1990 ). In the context of this work, distinctions were made between various forms and functions of aggression, most notably physical versus relational aggression and proactive versus reactive aggression (e.g., Little et al., 2003 ). Bullying was seen as a form of proactive aggression (Dodge & Coie, 1987 ) and a major cause for peer rejection, dislike, and maladjustment in various domains (Newcomb et al., 1993 ), most markedly, low social status. Olweus ( 1993 ) notably disagreed with what was then the dominant perception of bullies as insecure and socially unskilled. In contrast, he argued that their behavior was power-seeking, reward-driven (i.e., potentially adaptive), and sustained by average or high self-esteem as well as anxiety.

Not long after these arguments, the general picture of aggression in the study of child and adolescent peer relationships dramatically changed towards Olweus’s conceptions when researchers became interested in popularity (LaFontana & Cillessen, 1998 ; Parkhurst & Hopmeyer, 1998 ). Originally, in the assessment of peer relations, researchers focused on sociometrically assessing who youth “like the most” and “like the least” in their classroom or grade (Coie et al., 1982 ). In this era of peer relations research, high status referred to peer acceptance and low status to peer rejection. Indeed, all forms and functions of aggression correlated negatively with acceptance and positively with rejection. However, when peer relations researchers began to also ask youths who they thought were “most popular” and “least popular,” the picture of the role of aggression in the peer group quickly became more nuanced. Rodkin et al. ( 2000 ) identified two types of high-status peers: those who are well-liked and prosocial (“models”) and those who are seen as cool and aggressive (“toughs”). There is clear evidence that peer acceptance and popularity are not identical (see, for a meta-analysis, van den Berg et al., 2020 ), and a robust finding is the reversal of the correlation of measures of aggression and antisocial behavior with peer acceptance versus popularity.

As predicted by Olweus ( 1993 ), this includes measures of bullying. The consistently positive correlation between popularity and bullying at school suggests that bullying offers a degree of adaptiveness. Consistent with both sociometric findings and Olweus’s early assertions ( 1993 ), Sutton and colleagues ( 1999 ) argued against the “social skills deficit” perspective of bullying and instead suggested that bullying is associated with social cognitive skills and theory of mind (Shakoor et al., 2012 ) that are required to manipulate and organize others, as well as to inflict harm in subtle ways while avoiding detection. This perspective has led to a more nuanced picture of bullying (particularly as practiced by “pure” bullies versus bully-victims; Volk et al., 2014 ) as a complex behavior that includes social skills and is associated with high status and rewards in the peer group (Berger, 2007 ; Pouwels et al., 2018a , b ; Reijntjes et al., 2013 ). These same behaviors and traits often characterize cyberbullies (Kowalski et al., 2014 ; Olweus, 2012 ) and appear to persist across cultures (Smith et al., 2016 ). These findings are consistent with Olweus’s ( 1993 ) conceptualization of bullies as ringleaders who are capable of using social power to influence the social roles played by those around them, particularly those who would assist them (O’Connell et al., 1999 ; Salmivalli, 2010 ; Stellwagen & Kerig, 2013 ). This role-oriented approach to bullying has been validated by a separate body of peer relations research that has emphasized the importance of bullying power imbalances in promoting not only different roles among peers (e.g., reinforcing versus defending), but also in the adaptiveness of those ancillary bullying roles (Garandeau et al., 2014 ; Lambe et al., 2017 ; Spadafora et al., 2020 ).

One question that has intrigued researchers is whether the association between bullying and social power emerges for the first time in adolescence or already exists at earlier ages. On the one hand, there is evidence that the associations of peer acceptance and popularity with bullying and its underlying motives change from middle childhood to early adolescence (Caravita & Cillessen, 2012 ). On the other hand, researchers with an evolutionary perspective have argued that the association between aggression and power has long been observed among animals, and that it is not limited to adolescence, but exists in peer groups from a very early age on, including preschool groups (Hawley, 2002 , 2003 ; Kolbert & Crothers, 2003 ; Pellegrini, 2001 ). Indeed, among preschoolers, bullying perpetration is associated with fewer social costs than general aggressive behavior (Ostrov et al., 2019 ). Hence, bullying should be placed in a life-span developmental perspective, not only looking backward from adolescence into its earlier developmental roots, but also forward. The persistence of bullying into adulthood (i.e., a failure to “grow out” of the behavior) highlights the contribution of Olweus’s focus on bullying and power and the need for interventions to reduce bullying by increasing the costs and diminishing the benefits for perpetrators of bullying (Olweus & Limber, 2010 ).

Power and Bullying Interventions

In drawing attention to bullying as a particular type of aggression characterized by an imbalance of power, Olweus identified a challenging behavior for researchers and practitioners to address through interventions. As noted earlier, the costs of bullying are lower than other types of aggression, as bullying is done selectively under favorable circumstances in which the victim is unlikely to retaliate, be defended by bystanders, or evoke sympathy from peers (Veenstra et al., 2010 ; Volk et al., 2014 ). Furthermore, although bullies are disliked by some peers and at risk for a range of antisocial behaviors, developmental research has supported Olweus’s view that bullying is goal-directed aggression that can be beneficial for some individuals in some circumstances (Olweus, 1993 ), especially as a means to signal attractive or intimidating attributes to bystanders. This is evidenced by positive associations with popularity, number of dating and sexual partners, dominance, and access to resources (e.g., Dane et al., 2017 ; Reijntjes et al., 2013 , 2018 ; Volk et al., 2022b ). Reducing a behavior that affords a favorable cost–benefit ratio is, at least in the short term, a daunting task.

Nevertheless, Olweus took on this challenge by developing the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program, a comprehensive whole-school approach that addressed bullying in schools with school-wide, classroom, individual, and community components (Limber et al., 2018 ). The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP) was designed to take a social ecological approach to bullying, by restructuring the school environment to shift power imbalances by reducing opportunities and rewards for bullying. The goal was to build a sense of community based on values of equity and inclusion among students and adults in the school environment (Olweus, 1993 ). These principles are then translated into specific interventions to promote the prosocial use of power at the individual, classroom, school, and community levels and to create a climate in which all children feel safe and included (Olweus & Limber, 2010 ). Specifically, teachers and other adults were encouraged to set limits on bullying, model and reinforce appropriate behavior, and provide appropriate consequences for bullying and rule violations, especially by supervising settings where bullying was likely to occur (Limber et al., 2018 ). The OBPP thus has a broad range of components that highlight the importance of operating at different ecological levels (Bronfenbrenner, 1979 ). It is worth noting that while bullying is ubiquitous across cultures, there are cross-cultural differences in the rates of bullying, its forms, and its correlates (Smith et al., 2016 ). These differences demonstrate how bullying can, and does, respond to different culturally mediated costs and rewards (Volk et al., 2022b ). Evaluations of OBPP have demonstrated that changing environments and addressing power imbalances among students, peer groups, and in classrooms have been associated with reductions of bullying behavior (Limber et al., 2018 ).

Recent meta-analytic evidence confirms that the most promising means to reduce bullying has been when interventions were able to make conditions for bullying less favorable through changes in multiple ecological contexts (Gaffney et al., 2021 ). Specifically, interventions that provide all members of a school community, including peers and parents, with informal opportunities to reduce the benefits that may be achieved through the exploitation of a power imbalance, had larger effects on reducing bullying and victimization than programs in which these aspects were absent (Gaffney et al., 2021 ). Conversely, anti-bullying programs that focused on improving individual youths’ deficits in socio-emotional skills such as empathy, problem-solving skills, and self-control were less effective in reducing bullying perpetration and victimization, possibly because these programs ignored the ecological contexts that support the utility of power in bullying. These results may reflect Olweus’s view of bullying as a predatory exploitation of an advantage in power ( 1993 ), which suggests that a lack of social skills may not be a contributing factor. These findings also highlight that bullying is a problem that transcends individual relationships, which Olweus noted ( 2014 ) and has been implemented in other successful socio-ecological interventions (e.g., KiVa; Gaffney et al., 2019a , b ).

Although interventions that focus on changing contexts to make the results of bullying less favorable have had some success, research has revealed several challenges and limitations. Despite being beneficial overall, anti-bullying interventions have only been modestly effective, on average, reducing perpetration by 19–20% and victimization by 15–16% (Gaffney et al., 2019a , b ), and some have proven to be ineffective or iatrogenic (Merrell et al., 2008 ). Anti-bullying interventions are generally less effective with adolescents, who may value some of the social benefits of bullying more than children, such as attracting dating partners and gaining popularity (e.g., Yeager et al., 2015 ). These programs have also been less effective with popular youth (Garandeau et al., 2014 ), who may be unwilling to forego the benefits they can receive by exploiting a power advantage derived from high status. In addition, interventions that encourage bystanders to defend victims from bullies are less effective in reducing victimization than programs in which this is absent (Gaffney et al., 2021 ), which may demonstrate the challenge of confronting powerful perpetrators. Furthermore, anti-bullying interventions for cyberbullying, though effective, produce even more modest reductions in bullying perpetration (10–15%) and victimization (14%) than programs targeting traditional bullying (Gaffney et al., 2019a , b ). The results with cyberbullying interventions identify a new challenge—adapting anti-bullying approaches inspired by Olweus’s work to bullying in a cyber context in which anonymity, disinhibition due to a lack of face-to-face interactions, and obstacles to parental monitoring limit opportunities to make online conditions for bullying less favorable (Kowalski et al., 2014 ).

In addition, a failure to acknowledge the power imbalance inherent in bullying can facilitate the common harmful recommendation by adults and clinical practitioners: victims should fight back (see, for further discussion, Lochman et al., 2012 ). This lack of awareness about the role of power may also explain why it is the most common strategy reported by children and an approach they believe will be successful (Black et al., 2010 ). Unfortunately, while direct retaliation might protect an individual, it does not remove the bully’s option of finding another potentially weaker victim who lacks protection or the strength to defend themselves (Veenstra et al., 2010 ), or of retaliating when the power is once again back in the bully’s favor (e.g., when the victim’s friends are gone; Spadafora et al., 2020 ). Moreover, it is not always a feasible option for a victim to fight back or contact an adult or other appropriate authority figure. In fact, research demonstrates that fighting back can make the problem worse, as it may motivate the bully to avoid losing face or protect their power (Craig & Pepler, 1997 ; Sulkowski et al., 2014 ; Volk et al., 2014 ) and thus retaliation can become iatrogenic. Among adults, a failure to recognize power imbalances can lead to blaming victims for not helping themselves (Gupta et al., 2020 ; Lutgen-Sandvik, 2006 ). Finally, a belief that fighting back is all that is required to eliminate it reinforces the idea of bullying as a harmless right of passage—the very antithesis of Olweus’s message ( 1993 ).

Recent innovations in anti-bullying intervention research have sought to address the challenges that limit effectiveness by not only focusing on preventing bullying, but on fostering prosocial behavior (Ellis et al., 2016 ), in line with Olweus’s emphasis on modeling and reinforcing appropriate behavior in the OBPP anti-bullying intervention (Limber et al., 2018 ). Rather than discouraging bullies from pursuing valued benefits (e.g., popularity, romantic partners), this intervention acknowledges the goal-directed nature of bullying and provides structured opportunities for youth to experience using prosocial behavior as an equally effective means to obtain desired goals (Ellis et al., 2016 ). When combined with existing intervention components that are known to be effective (see above), such innovations offer a roadmap for diverting students’ behavior away from exploiting power through bullying to achieve personal gains and instead encouraging prosocial conduct that can yield similar but mutual benefits to those who cooperate with one another. Thus, Olweus’s discussion of bullying and power has had important implications for the way that bullying has not only been studied, but in how bullying interventions have been designed. Critically though, we view Olweus’s ideas about bullying and power as having an important impact above and beyond schools.

Bullying and Power Beyond the School

School bullying thus remains a serious issue, but it is likely to remain an unsolvable issue if children continue to see successful examples of bullying modeled in homes, relationships, workplaces, and governments. Bullying is a developmental phenomenon that extends beyond the school years. As individuals age, other forms of developmentally relevant aggressive behaviors emerge (dating violence, sexual harassment, workplace bullying) and are implemented to exert power, harm, and influence (Farrel & Vaillancourt, 2021 ; Pepler et al., 2006 ). A developmental perspective shows that bullying behavior, and the rewards associated with it, do not stop in adolescence but persist into the social contexts of adults. Furthermore, the social ecological perspective highlights the importance of external ecological impacts, such as parents, communities, and governments, and how bullying and the abuse of power are an issue that deeply involves, but also transcends, the school setting. For example, when consistent efforts towards altering the power structure were abandoned at higher ecological levels (e.g., government and community support), the Norwegian OBPP failed to have significant effects and bullying returned to pre-intervention levels (Roland, 2011 ). These multiple layers of factors that can influence and promote imbalances of power and bullying beyond schools and into many other aspects of child and adult life reveal an important reason why bullying has proven so challenging to eliminate.

It is thus no mistake that Olweus called on adults to actively participate in bullying interventions (Olweus & Limber, 2010 ). Bullying behaviors modeled by persons in positions of leadership show how school bullying is a complex ecological issue that also involves adults’ behavior. We take his message that school bullying is harmful and use it to encourage school bullying researchers to take steps towards a broader understanding of the abuse of power not only among children, but in diverse settings and individuals across the lifespan. For example, in a longitudinal study of a purple (mixed Republican and Democrat) state before and after Trump’s election, Huang and Cornell ( 2019 ) found an increase in students’ reports of being bullied, as well as teasing about racial ethnicity in schools, following Trump’s victory in 2016. Interestingly, this increase was found only in parts of the state with a Republican (Trump) voter preference in the 2016 election, presumably due to youths emulating their locally popular President. The societal rewards of bullying continue across the lifespan, including financial, business, and political power for adults (e.g., our previous list of modern injustices).

The nursing profession, for example, has perhaps been more active than any other in identifying internal and external issues of professional bullying (Wilson, 2016 ). Using Olweus’s conceptualization of bullying, researchers have identified how nurses face serious mental, physical, and financial risks from bullying by fellow nurses, doctors, and even patients (Wilson, 2016 ). Bullying is found in many other workplaces, leading to the creation of anti-bullying interventions that aim to reduce it. These adult interventions are often modeled on principles discovered in school bullying research, suggesting that work done with children can also apply to adults, and vice versa (Gupta et al., 2020 ). As noted earlier, there has been a growing outcry against abuses of power in the adult world that parallel the calls for action against bullying in schools, albeit with less broad support (Klein, 2014 ). The resistance to change in the adult abuse of power in many ways mirrors the stubborn resistance to decreasing school bullying through intervention efforts (Gaffney et al., 2019a , b , 2021 ). It is likely that some of the resistance among adults is similar to that among children—groups and individuals who have power are often loath to share it because of the benefits it affords. That selfish lack of support by those with power is perhaps one of the reasons that adults have failed to address their own abuses of power, alongside a lack of determination to vigorously fight against school bullying (Roland, 2011 ).

On the other hand, evidence is now clear how bullying research, as inspired by Olweus’s work, has been received by the broader public. As noted, a Google Scholar search of “bullying” returned one million results, but a general Google search of “bullying” returned 4.75 billion results (October, 2021). Bullying has clearly captured the attention of both academics and the general public. We argue that the reason for this attention to bullying is that, although humans can show a capacity for bullying and the abuse of power (Pellegrini, 2001 ), they can also show a deeply egalitarian, negative response to the abuse of power imbalances (Klein, 2014 ).