Should Animals be Used in Research: Argumentative Essay

Should animals be used in research? This argumentative essay aims to answer the question. It focuses on pros and cons of animal testing for scientific and medical goals.

Introduction

- The Arguments

Works Cited

All over the world, animal activists and institutions have argued whether or not research should be used on animals or should be outlawed. Philosophers believe that experiments on animals are not morally justified because they cause pain or harm the animals. A group of these philosophers believe that other alternatives are available, thus they claim that because we have other alternatives, the use of animals in research should be outlawed.

Should Animals Be Used in Research? The Arguments

In my opinion, I support the line of argument that animals should not be used in research. Since the discovery of knowing through science (research), the use of animals in research has elicited mixed reactions among different scholars. Philosophers are against the idea citing the availability of other options for toxicological tests on animals and the harsh treatments the scientists have accorded these animals in the medical tests. Unless scientists discover other ways of testing medicines, I think tests on animals are unethical.

Scientists use these creatures to validate a theory and then revise or change their theories depending on the new facts or information gained from every test performed. Animal rights lobby groups believe that animals are used for no reasons in these experiments as the animals endure pain inflicted on them during these tests (Singer 2). They tend to overlook the fact that animals have moral existence, social and religious values. Thousands of animals on this planet contribute largely to the aesthetic appeal of the land.

On the other hand, scientists only see the positive contributions of animal tests to the medical field and ignore the side effects of the tests on the animals’ lives. They overlook the idea that animals are hurt and thus suffer tremendously.

To them the impact of the research on the lives of their families and friends by coming up with vaccines and drugs is the inspiration. Research on animals should be banned because it inflicts pain, harms the culprits and morally it is unjustified. Has man ever wondered whether or not animals feel similar pain that humans feel? (Singer 2).

Human beings know very well that they themselves feel pain. For example, you will know that a metal rod is hot by touching it with bare hands. It is believed that pain is mental; in other words it cannot be seen. We feel pain and we realize that other creatures also feel pain from observations like jerking away from an event or even yelling.

Since the reactions are the same as those of man, philosophers say that animals feel similar pain just like humans. Animal activists reaffirm that the major undoing of tests involving animals is the manner in which the animals are treated arguing that anesthesia for suppressing the pain is never used.

However, as many people are opposed to the use of animals in research, many lives have been saved every year due to their death. I think that instead of refuting that taking away the life of a rat is unethical, harms the animal; I believe it is a bold step in improving the welfare of millions of people for thousands of years to come. Tests on animals are the most common toxicological tests used by scientists; the findings help to better lives for hundreds of people across the universe (Fox 12).

Fox, Michael A. The Case for Animal Experimentation. California: University of California Press, 1986.

Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation. New York: Random House, 1975.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 30). Should Animals be Used in Research: Argumentative Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/should-animals-be-used-in-research/

"Should Animals be Used in Research: Argumentative Essay." IvyPanda , 30 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/should-animals-be-used-in-research/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Should Animals be Used in Research: Argumentative Essay'. 30 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Should Animals be Used in Research: Argumentative Essay." October 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/should-animals-be-used-in-research/.

1. IvyPanda . "Should Animals be Used in Research: Argumentative Essay." October 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/should-animals-be-used-in-research/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Should Animals be Used in Research: Argumentative Essay." October 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/should-animals-be-used-in-research/.

- Toxicological Issues at a Hazardous Waste Site

- Toxicological Applications: Occupational Safety and Health Professional

- OECD-GLP Guidelines: Toxicological Tests

- Banning Violent Video Games Argumentative Essay

- Argumentative Essay Writing

- Has the Internet Positively or Negatively Impacted Human Society? Argumentative Essay

- Pros and Cons of Abortion to the Society Argumentative Essay

- Aspects of the Writing an Argumentative Essay

- An Argumentative Essay: How to Write

- Writing Argumentative Essay With Computer Aided Formulation

- Ethical Problems of the Animal Abuse

- The Debate About Animal Rights

- Animal Cloning Benefits and Controversies

- Use of Animals in Research Testing: Ethical Justifications Involved

- Experimentation on Animals

Animals Should Be Used for Research

Introduction, controversy, thesis statement.

Since humans and animals have similar biology, animals are often used to provide experimental studies and understand how diseases impact them or how drugs can help, but ethics and legal issues cause public controversy.

Animal testing, also known as animal research, uses experiments to understand the factors that impact the behaviors in a biological system. Laboratory animals include mice, zebrafishes, primates, and many other species. The main goal of using animals in research is to improve the understanding of biology and create new treatments that would be safe for humans.

Animals are biologically similar to humans, which makes them a perfect object for studying the course of diseases and various treatment options. For example, vaccines, antibiotics, HIV treatment, and transplantation were developed based on animal research (Garner, 2016). The role of animals is vital since they serve as the models for drug creation and testing. Without animal research, it would be impossible to minimize such diseases as measles, poliomyelitis, and other infections. Today, animal research provides hope for people, who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and asthma.

On the one hand, those who want to prohibit animal research claim that animals’ rights are violated, they suffer, and it is better to use computers and technology. They also insist that human tissues should be used in clinical settings, but many diseases can only be explored in a living body (Meigs et al., 2018). On the other hand, animal testing significantly contributed to health improvement as people can successfully manage a variety of conditions and live longer. In addition, it ensures a high quality and safety of drugs, which means that many side effects are addressed to make treatment more effective.

Although animal research is considered unethical, painful, and harmful for the objects of experiments, animals should be used for research to understand diseases and develop effective drugs to improve public health.

Garner, R. (2016). Animal rights: The changing debate . Springer.

Meigs, L., Smirnova, L., Rovida, C., Leist, M., & Hartung, T. (2018). Animal testing and its alternatives: the most important omics is economics. Alternatives to Animal Experimentation: ALTEX , 35 (3), 275-305.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, June 28). Animals Should Be Used for Research. https://studycorgi.com/animals-should-be-used-for-research/

"Animals Should Be Used for Research." StudyCorgi , 28 June 2022, studycorgi.com/animals-should-be-used-for-research/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Animals Should Be Used for Research'. 28 June.

1. StudyCorgi . "Animals Should Be Used for Research." June 28, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/animals-should-be-used-for-research/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Animals Should Be Used for Research." June 28, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/animals-should-be-used-for-research/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Animals Should Be Used for Research." June 28, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/animals-should-be-used-for-research/.

This paper, “Animals Should Be Used for Research”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: October 9, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Animal Testing — Should Animals Be Used for Research: an Argumentative Perspective

Should Animals Be Used for Research: an Argumentative Perspective

- Categories: Animal Testing Animals Research

About this sample

Words: 1002 |

Published: Dec 3, 2020

Words: 1002 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues Science Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1012 words

2 pages / 878 words

1 pages / 603 words

2 pages / 858 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Animal Testing

Animal testing is a controversial topic that has sparked heated debates among scientists, ethicists, and the general public. The ethical implications of using animals in scientific research are complex and multifaceted, with [...]

Animal testing has been a common practice in scientific research and testing for decades. The use of animals, however, remains a highly controversial issue. Animal Research: The Ethics of Animal Experimentation. [...]

From rabbits to dogs, animals are commonly used in research studies as test subjects to advance scientific knowledge and develop new drugs. However, the ethical implications of using animals in research cannot be ignored. While [...]

Animal testing, also known as animal experimentation, is the use of non-human animals for scientific research purposes. It involves subjecting animals to various procedures, such as surgical operations, injections, and exposure [...]

Balls, M., & Fabre, I. (2019). Alternatives to Animal Testing: A Review. European Pharmaceutical Review, 24(6), 29-33.Ekwall, B. (2000). The Multicentre Evaluation of In Vitro Cytotoxicity (MEIC) Programme: A Model for [...]

Introduction to the issue of animal testing in the cosmetic industry The ethical concerns surrounding animal testing Arguments in favor of animal testing, including potential medical advancements [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Ethical care for research animals

WHY ANIMAL RESEARCH?

The use of animals in some forms of biomedical research remains essential to the discovery of the causes, diagnoses, and treatment of disease and suffering in humans and in animals., stanford shares the public's concern for laboratory research animals..

Many people have questions about animal testing ethics and the animal testing debate. We take our responsibility for the ethical treatment of animals in medical research very seriously. At Stanford, we emphasize that the humane care of laboratory animals is essential, both ethically and scientifically. Poor animal care is not good science. If animals are not well-treated, the science and knowledge they produce is not trustworthy and cannot be replicated, an important hallmark of the scientific method .

There are several reasons why the use of animals is critical for biomedical research:

• Animals are biologically very similar to humans. In fact, mice share more than 98% DNA with us!

• Animals are susceptible to many of the same health problems as humans – cancer, diabetes, heart disease, etc.

• With a shorter life cycle than humans, animal models can be studied throughout their whole life span and across several generations, a critical element in understanding how a disease processes and how it interacts with a whole, living biological system.

The ethics of animal experimentation

Nothing so far has been discovered that can be a substitute for the complex functions of a living, breathing, whole-organ system with pulmonary and circulatory structures like those in humans. Until such a discovery, animals must continue to play a critical role in helping researchers test potential new drugs and medical treatments for effectiveness and safety, and in identifying any undesired or dangerous side effects, such as infertility, birth defects, liver damage, toxicity, or cancer-causing potential.

U.S. federal laws require that non-human animal research occur to show the safety and efficacy of new treatments before any human research will be allowed to be conducted. Not only do we humans benefit from this research and testing, but hundreds of drugs and treatments developed for human use are now routinely used in veterinary clinics as well, helping animals live longer, healthier lives.

It is important to stress that 95% of all animals necessary for biomedical research in the United States are rodents – rats and mice especially bred for laboratory use – and that animals are only one part of the larger process of biomedical research.

Our researchers are strong supporters of animal welfare and view their work with animals in biomedical research as a privilege.

Stanford researchers are obligated to ensure the well-being of all animals in their care..

Stanford researchers are obligated to ensure the well-being of animals in their care, in strict adherence to the highest standards, and in accordance with federal and state laws, regulatory guidelines, and humane principles. They are also obligated to continuously update their animal-care practices based on the newest information and findings in the fields of laboratory animal care and husbandry.

Researchers requesting use of animal models at Stanford must have their research proposals reviewed by a federally mandated committee that includes two independent community members. It is only with this committee’s approval that research can begin. We at Stanford are dedicated to refining, reducing, and replacing animals in research whenever possible, and to using alternative methods (cell and tissue cultures, computer simulations, etc.) instead of or before animal studies are ever conducted.

Organizations and Resources

There are many outreach and advocacy organizations in the field of biomedical research.

- Learn more about outreach and advocacy organizations

Stanford Discoveries

What are the benefits of using animals in research? Stanford researchers have made many important human and animal life-saving discoveries through their work.

- Learn more about research discoveries at Stanford

Research using animals: an overview

Around half the diseases in the world have no treatment. Understanding how the body works and how diseases progress, and finding cures, vaccines or treatments, can take many years of painstaking work using a wide range of research techniques. There is overwhelming scientific consensus worldwide that some research using animals is still essential for medical progress.

Animal research in the UK is strictly regulated. For more details on the regulations governing research using animals, go to the UK regulations page .

Why is animal research necessary?

There is overwhelming scientific consensus worldwide that some animals are still needed in order to make medical progress.

Where animals are used in research projects, they are used as part of a range of scientific techniques. These might include human trials, computer modelling, cell culture, statistical techniques, and others. Animals are only used for parts of research where no other techniques can deliver the answer.

A living body is an extraordinarily complex system. You cannot reproduce a beating heart in a test tube or a stroke on a computer. While we know a lot about how a living body works, there is an enormous amount we simply don’t know: the interaction between all the different parts of a living system, from molecules to cells to systems like respiration and circulation, is incredibly complex. Even if we knew how every element worked and interacted with every other element, which we are a long way from understanding, a computer hasn’t been invented that has the power to reproduce all of those complex interactions - while clearly you cannot reproduce them all in a test tube.

While humans are used extensively in Oxford research, there are some things which it is ethically unacceptable to use humans for. There are also variables which you can control in a mouse (like diet, housing, clean air, humidity, temperature, and genetic makeup) that you could not control in human subjects.

Is it morally right to use animals for research?

Most people believe that in order to achieve medical progress that will save and improve lives, perhaps millions of lives, limited and very strictly regulated animal use is justified. That belief is reflected in the law, which allows for animal research only under specific circumstances, and which sets out strict regulations on the use and care of animals. It is right that this continues to be something society discusses and debates, but there has to be an understanding that without animals we can only make very limited progress against diseases like cancer, heart attack, stroke, diabetes, and HIV.

It’s worth noting that animal research benefits animals too: more than half the drugs used by vets were developed originally for human medicine.

Aren’t animals too different from humans to tell us anything useful?

No. Just by being very complex living, moving organisms they share a huge amount of similarities with humans. Humans and other animals have much more in common than they have differences. Mice share over 90% of their genes with humans. A mouse has the same organs as a human, in the same places, doing the same things. Most of their basic chemistry, cell structure and bodily organisation are the same as ours. Fish and tadpoles share enough characteristics with humans to make them very useful in research. Even flies and worms are used in research extensively and have led to research breakthroughs (though these species are not regulated by the Home Office and are not in the Biomedical Sciences Building).

What does research using animals actually involve?

The sorts of procedures research animals undergo vary, depending on the research. Breeding a genetically modified mouse counts as a procedure and this represents a large proportion of all procedures carried out. So does having an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan, something which is painless and which humans undergo for health checks. In some circumstances, being trained to go through a maze or being trained at a computer game also counts as a procedure. Taking blood or receiving medication are minor procedures that many species of animal can be trained to do voluntarily for a food reward. Surgery accounts for only a small minority of procedures. All of these are examples of procedures that go on in Oxford's Biomedical Sciences Building.

How many animals are used?

Figures for 2023 show numbers of animals that completed procedures, as declared to the Home Office using their five categories for the severity of the procedure.

# NHPs - Non Human Primates

Oxford also maintains breeding colonies to provide animals for use in experiments, reducing the need for unnecessary transportation of animals.

Figures for 2017 show numbers of animals bred for procedures that were killed or died without being used in procedures:

Why must primates be used?

Primates account for under half of one per cent (0.5%) of all animals housed in the Biomedical Sciences Building. They are only used where no other species can deliver the research answer, and we continually seek ways to replace primates with lower orders of animal, to reduce numbers used, and to refine their housing conditions and research procedures to maximise welfare.

However, there are elements of research that can only be carried out using primates because their brains are closer to human brains than mice or rats. They are used at Oxford in vital research into brain diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Some are used in studies to develop vaccines for HIV and other major infections.

What is done to primates?

The primates at Oxford spend most of their time in their housing. They are housed in groups with access to play areas where they can groom, forage for food, climb and swing.

Primates at Oxford involved in neuroscience studies would typically spend a couple of hours a day doing behavioural work. This is sitting in front of a computer screen doing learning and memory games for food rewards. No suffering is involved and indeed many of the primates appear to find the games stimulating. They come into the transport cage that takes them to the computer room entirely voluntarily.

After some time (a period of months) demonstrating normal learning and memory through the games, a primate would have surgery to remove a very small amount of brain tissue under anaesthetic. A full course of painkillers is given under veterinary guidance in the same way as any human surgical procedure, and the animals are up and about again within hours, and back with their group within a day. The brain damage is minor and unnoticeable in normal behaviour: the animal interacts normally with its group and exhibits the usual natural behaviours. In order to find out about how a disease affects the brain it is not necessary to induce the equivalent of full-blown disease. Indeed, the more specific and minor the brain area affected, the more focussed and valuable the research findings are.

The primate goes back to behavioural testing with the computers and differences in performance, which become apparent through these carefully designed games, are monitored.

At the end of its life the animal is humanely killed and its brain is studied and compared directly with the brains of deceased human patients.

Primates at Oxford involved in vaccine studies would simply have a vaccination and then have monthly blood samples taken.

How many primates does Oxford hold?

* From 2014 the Home Office changed the way in which animals/ procedures were counted. Figures up to and including 2013 were recorded when procedures began. Figures from 2014 are recorded when procedures end.

What’s the difference between ‘total held’ and ‘on procedure’?

Primates (macaques) at Oxford would typically spend a couple of hours a day doing behavioural work, sitting in front of a computer screen doing learning and memory games for food rewards. This is non-invasive and done voluntarily for food rewards and does not count as a procedure. After some time (a period of months) demonstrating normal learning and memory through the games, a primate would have surgery under anaesthetic to remove a very small amount of brain tissue. The primate quickly returns to behavioural testing with the computers, and differences in performance, which become apparent through these carefully designed puzzles, are monitored. A primate which has had this surgery is counted as ‘on procedure’. Both stages are essential for research into understanding brain function which is necessary to develop treatments for conditions including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and schizophrenia.

Why has the overall number held gone down?

Numbers vary year on year depending on the research that is currently undertaken. In general, the University is committed to reducing, replacing and refining animal research.

You say primates account for under 0.5% of animals, so that means you have at least 16,000 animals in the Biomedical Sciences Building in total - is that right?

Numbers change daily so we cannot give a fixed figure, but it is in that order.

Aren’t there alternative research methods?

There are very many non-animal research methods, all of which are used at the University of Oxford and many of which were pioneered here. These include research using humans; computer models and simulations; cell cultures and other in vitro work; statistical modelling; and large-scale epidemiology. Every research project which uses animals will also use other research methods in addition. Wherever possible non-animal research methods are used. For many projects, of course, this will mean no animals are needed at all. For others, there will be an element of the research which is essential for medical progress and for which there is no alternative means of getting the relevant information.

How have humans benefited from research using animals?

As the Department of Health states, research on animals has contributed to almost every medical advance of the last century.

Without animal research, medicine as we know it today wouldn't exist. It has enabled us to find treatments for cancer, antibiotics for infections (which were developed in Oxford laboratories), vaccines to prevent some of the most deadly and debilitating viruses, and surgery for injuries, illnesses and deformities.

Life expectancy in this country has increased, on average, by almost three months for every year of the past century. Within the living memory of many people diseases such as polio, tuberculosis, leukaemia and diphtheria killed or crippled thousands every year. But now, doctors are able to prevent or treat many more diseases or carry out life-saving operations - all thanks to research which at some stage involved animals.

Each year, millions of people in the UK benefit from treatments that have been developed and tested on animals. Animals have been used for the development of blood transfusions, insulin for diabetes, anaesthetics, anticoagulants, antibiotics, heart and lung machines for open heart surgery, hip replacement surgery, transplantation, high blood pressure medication, replacement heart valves, chemotherapy for leukaemia and life support systems for premature babies. More than 50 million prescriptions are written annually for antibiotics.

We may have used animals in the past to develop medical treatments, but are they really needed in the 21st century?

Yes. While we are committed to reducing, replacing and refining animal research as new techniques make it possible to reduce the number of animals needed, there is overwhelming scientific consensus worldwide that some research using animals is still essential for medical progress. It only forms one element of a whole research programme which will use a range of other techniques to find out whatever possible without animals. Animals would be used for a specific element of the research that cannot be conducted in any alternative way.

How will humans benefit in future?

The development of drugs and medical technologies that help to reduce suffering among humans and animals depends on the carefully regulated use of animals for research. In the 21st century scientists are continuing to work on treatments for cancer, stroke, heart disease, HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson’s, and very many more diseases that cause suffering and death. Genetically modified mice play a crucial role in future medical progress as understanding of how genes are involved in illness is constantly increasing.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.8(6); 2007 Jun

The ethics of animal research. Talking Point on the use of animals in scientific research

Simon festing.

1 Simon Festing is Executive Director and Robin Wilkinson is Science Communications Officer at the Research Defence Society in London, UK. ku.gro.ten-sdr@gnitsefs

Robin Wilkinson

Animal research has had a vital role in many scientific and medical advances of the past century and continues to aid our understanding of various diseases. Throughout the world, people enjoy a better quality of life because of these advances, and the subsequent development of new medicines and treatments—all made possible by animal research. However, the use of animals in scientific and medical research has been a subject of heated debate for many years in the UK. Opponents to any kind of animal research—including both animal-rights extremists and anti-vivisectionist groups—believe that animal experimentation is cruel and unnecessary, regardless of its purpose or benefit. There is no middle ground for these groups; they want the immediate and total abolition of all animal research. If they succeed, it would have enormous and severe consequences for scientific research.

No responsible scientist wants to use animals or cause them unnecessary suffering if it can be avoided, and therefore scientists accept controls on the use of animals in research. More generally, the bioscience community accepts that animals should be used for research only within an ethical framework.

The UK has gone further than any other country to write such an ethical framework into law by implementing the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. It exceeds the requirements in the European Union's Directive 86/609/EEC on the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes, which is now undergoing revision ( Matthiessen et al , 2003 ). The Act requires that proposals for research involving the use of animals must be fully assessed in terms of any harm to the animals. This involves detailed examination of the particular procedures and experiments, and the numbers and types of animal used. These are then weighed against the potential benefits of the project. This cost–benefit analysis is almost unique to UK animal research legislation; only German law has a similar requirement.

The UK has gone further than any other country to write such an ethical framework into law by implementing the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986

In addition, the UK government introduced in 1998 further ‘local' controls—that is, an Ethical Review Process at research institutions—which promote good animal welfare and humane science by ensuring that the use of animals at the designated establishment is justified. The aims of this additional review process are: to provide independent ethical advice, particularly with respect to applications for project licences, and standards of animal care and welfare; to provide support to licensees regarding animal welfare and ethical issues; and to promote ethical analysis to increase awareness of animal welfare issues and to develop initiatives for the widest possible application of the 3Rs—replacement, reduction and refinement of the use of animals in research ( Russell & Burch, 1959 ). In practice, there has been concern that the Ethical Review Process adds a level of bureaucracy that is not in proportion to its contribution to improving animal welfare or furthering the 3Rs.

Thanks to some extensive opinion polls by MORI (1999a , 2002 , 2005 ), and subsequent polls by YouGov (2006) and ICM (2006) , we now have a good understanding of the public's attitudes towards animal research. Although society views animal research as an ethical dilemma, polls show that a high proportion—84% in 1999, 90% in 2002 and 89% in 2005—is ready to accept the use of animals in medical research if the research is for serious medical purposes, suffering is minimized and/or alternatives are fully considered. When asked which factors should be taken into account in the regulatory system, people chose those that—unknown to them—are already part of the UK legislation. In general, they feel that animal welfare should be weighed against health benefits, that cosmetic-testing should not be allowed, that there should be supervision to ensure high standards of welfare, that animals should be used only if there is no alternative, and that spot-checks should be carried out. It is clear that the UK public would widely support the existing regulatory system if they knew more about it.

It is clear that the UK public would widely support the existing regulatory system if they knew more about it

GP Net also asked whether GPs agreed that “medical research data can be misleading”; 93% agreed. This result puts into context the results from another poll of GPs in 2004. Europeans for Medical Progress (EMP; London, UK), an anti-vivisection group, found that 82% had a “concern […] that animal data can be misleading when applied to humans” ( EMP, 2004) . In fact, it seems that most GPs think that medical research in general can be misleading; it is good scientific practice to maintain a healthy degree of scepticism and avoid over-reliance on any one set of data or research method.

Another law, which enables people to get more information, might also help to influence public attitudes towards animal research. The UK Freedom of Information (FOI) Act came into full force on 1 January 2005. Under the Act, anybody can request information from a public body in England, Wales or Northern Ireland. Public bodies include government departments, universities and some funding bodies such as the research councils. The FOI Act is intended to promote openness and accountability, and to facilitate better public understanding of how public authorities carry out their duties, why and how they make decisions, and how they spend public money. There are two ways in which information can be made available to the public: some information will be automatically published and some will be released in response to individual requests. The FOI Act is retrospective so it applies to all information, regardless of when it was created.

In response to the FOI Act, the Home Office now publishes overviews of all new animal research projects, in the form of anonymous project licence summaries, on a dedicated website. This means that the UK now provides more public information about animal research than any other country. The Research Defence Society (RDS; London, UK), an organization representing doctors and scientists in the debate on the use of animals in research and testing, welcomes the greater openness that the FOI Act brings to discussions about animal research. With more and reliable information about how and why animals are used, people should be in a better position to debate the issues. However, there are concerns that extremist groups will try to obtain personal details and information that can identify researchers, and use it to target individuals.

As a House of Lords Select Committee report in July 2002 stated, “The availability to the public of regularly updated, good quality information on what animal experiments are done and why, is vital to create an atmosphere in which the issue of animal experimentation can be discussed productively” ( House of Lords, 2002 ). Indeed, according to a report on public attitudes to the biological sciences and their oversight, “Having information and perceived honesty and openness are the two key considerations for the public in order for them to have trust in a system of controls and regulations about biological developments” ( MORI, 1999b ).

In the past five years, there have been four major UK independent inquiries into the use of animals in biomedical research: a Select Committee in the House of Lords (2002) ; the Animal Procedures Committee (2003) ; the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2005) ; and the Weatherall Committee ( Weatherall et al , 2006 ), which specifically examined the use of non-human primates in scientific and medical research. All committees included non-scientists and examined evidence from both sides of the debate. These rigorous independent inquiries all accepted the rationale for the use of animals in research for the benefit of human health, and concluded that animal research can be scientifically validated on a case-by-case basis. The Nuffield Council backed the 3Rs and the need for clear information to support a constructive debate, and further stated that violence and intimidation against researchers or their allies is morally wrong.

Animal research has obviously become a smaller proportion of overall bioscience and medical R&D spending in the UK

In addition, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA; London, UK) has investigated and ruled on 38 complaints made since 1992 about published literature—leaflets and brochures—regarding claims about the validity or otherwise of animal research and the scope of alternative methods. In 34 out of 38 cases, they found against the anti-vivisectionist groups, either supporting complaints about anti-vivisectionist literature, or rejecting the complaints by anti-vivisectionists about the literature from medical organizations. Only four complaints against scientific/medical research literature have been upheld, not because the science was flawed but as a result of either semantics or the ASA judging that the advertisement fell outside the UK remit.

Animal-rights groups also disagree with the 3Rs, since these principles still allow for the use of animals in research; they are only interested in replacement

However, seemingly respectable mainstream groups still peddle dangerously misleading and inaccurate information about the use of animals in research. As previously mentioned, EMP commissioned a survey of GPs that showed that the “majority of GPs now question the scientific worth of animal tests” ( EMP, 2004 ). The raw data is available on the website of EMP's sister group Americans For Medical Advancement (AFMA; Los Angeles, CA, USA; AFMA, 2004 ), but their analysis is so far-fetched that the polling company, TNS Healthcare (London, UK), distanced itself from the conclusions. In a statement to the Coalition for Medical Progress (London, UK)—a group of organizations that support animal research—TNS Healthcare wrote, “The conclusions drawn from this research by AFMA are wholly unsupported by TNS and any research findings or comment published by AFMA is not TNS approved. TNS did not provide any interpretation of the data to the client. TNS did not give permission to the client to publish our data. The data does not support the interpretation made by the client (which in our opinion exaggerates anything that may be found from the data)” ( TNS Healthcare, 2004 ). Nonetheless, EMP has used its analysis to lobby government ministers and misinform the public.

Approximately 2.7 million regulated animal procedures were conducted in 2003 in the UK—half the number performed 30 years ago. The tight controls governing animal experimentation and the widespread implementation of the 3Rs by the scientific community is largely responsible for this downward trend, as recognized recently by then Home Office Minister, Caroline Flint: “…new technologies in developing drugs [have led] to sustained and incremental decreases in some types of animal use over recent years, whilst novel medicines have continued to be produced. This is an achievement of which the scientific community can be rightly proud” ( Flint, 2005 ).

After a period of significant reduction, the number of regulated animal procedures stabilized from 1995 until 2002. Between 2002 and 2005, the use of genetically modified animals—predominantly mice—led to a 1–2% annual increase in the number of animals used ( Home Office, 2005 ). However, between 1995 and 2005, the growth in UK biomedical research far outstripped this incremental increase: combined industry and government research and development (R&D) spending rose by 73% from £2,080 million to £3,605 million ( ABPI, 2007 ; DTI, 2005 ). Animal research has obviously become a smaller proportion of overall bioscience and medical R&D spending in the UK. This shows the commitment of the scientific community to the development and use of replacement and reduction techniques, such as computer modelling and human cell lines. Nevertheless, animal research remains a small, but vital, part of biomedical research—experts estimate it at about 10% of total biomedical R&D spending.

The principles of replacing, reducing and refining the use of animals in scientific research are central to UK regulation. In fact, the government established the National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs; London, UK) in May 2004 to promote and develop high-quality research that takes the 3Rs into account. In support of this, then Science Minister Lord Sainsbury announced in 2005 that the Centre would receive an additional £1.5 million in funding over the next three years.

The ultimate aim of the NC3Rs is to substitute a significant proportion of animal research by investigating the development of alternative techniques, such as human studies, and in vitro and in silico studies. RDS supports this aim, but believes that it is unrealistic to expect this to be possible in every area of scientific research in the immediate future. After all, if the technology to develop these alternatives is not available or does not yet exist, progress is likely to be slow. The main obstacle is still the difficulty of accurately mimicking the complex physiological systems of whole living organisms—a challenge that will be hard to meet. There has been some progress recently imitating single organs such as the liver, but these need further refinement to make them suitable models for an entire organ and, even if validated, they cannot represent a whole-body system. New and promising techniques such as microdosing also have the potential to reduce the number of animals used in research, but again cannot replace them entirely.

Anti-vivisectionist groups do not accept this reality and are campaigning vigorously for the adoption of other methods without reference to validation or acceptance of their limitations, or the consequences for human health. Animal-rights groups also disagree with the 3Rs, since these principles still allow for the use of animals in research; they are only interested in replacement. Such an approach would ignore the recommendations of the House of Lords Select Committee report, and would not deal with public concerns about animal welfare. Notwithstanding this, the development of alternatives—which invariably come from the scientific community, rather than anti-vivisection groups—will necessitate the continued use of animals during the research, development and validation stages.

Society should push authorities to quickly adopt successfully validated techniques, while realizing that pushing for adoption without full validation could endanger human health

The scientific community, with particular commitment shown by the pharmaceutical industry, has responded by investing a large amount of money and effort in developing the science and technology to replace animals wherever possible. However, the development of direct replacement technologies for animals is a slow and difficult process. Even in regulatory toxicology, which might seem to be a relatively straightforward task, about 20 different tests are required to assess the risk of any new substance. In addition, introducing a non-animal replacement technique involves not only development of the method, but also its validation by national and international regulatory authorities. These authorities tend to be conservative and can take many years to write a new technique into their guidelines. Even then, some countries might insist that animal tests are carried out if they have not been explicitly written out of the guidelines. Society should push authorities to quickly adopt successfully validated techniques, while realizing that pushing for adoption without full validation could endanger human health.

Despite the inherent limitations of some non-animal tests, they are still useful for pre-screening compounds before the animal-testing stage, which would therefore reduce rather than replace the number of animals used. An example of this is the Ames test, which uses strains of the bacterium Salmonella typhimurium to determine whether chemicals cause mutations in cellular DNA. This and other tests are already widely used as pre-screens to partly replace rodent testing for cancer-causing compounds. Unfortunately, the in vitro tests can produce false results, and tend to be used more to understand the processes of mutagenicity and carcinogenicity than to replace animal assays. However, there are moves to replace the standard mouse carcinogenicity assay with other animal-based tests that cause less suffering because they use fewer animals and do not take as long. This has already been achieved in tests for acute oral toxicity, where the LD50—the median lethal dose of a substance—has largely been replaced by the Fixed Dose Procedure, which was developed, validated and promoted between 1984 and 1989 by a worldwide collaboration, headed by scientists at the British Toxicological Society (Macclesfield, UK).

Although animals cannot yet be completely replaced, it is important that researchers maximize refinement and reduction

Furthermore, cell-culture based tests have considerably reduced the use of rodents in the initial screening of potential new medicines, while speeding up the process so that 10–20 times the number of compounds can be screened in the same period. A leading cancer charity, Yorkshire Cancer Research (Harrogate, UK), funded research into the use of cell cultures to understand better the cellular mechanisms of prostate cancer—allowing researchers to investigate potential therapies using fewer animals.

Microdosing is an exciting new technique for measuring how very small doses of a compound move around the body. In principle, it should be possible to use this method in humans and therefore to reduce the number of animals needed to study new compounds; however, it too has limitations. By its very nature, it cannot predict toxicity or side effects that occur at higher therapeutic doses. It is an unrealistic hope—and a false claim—that microdosing can completely replace the use of animals in scientific research; “animal studies will still be required,” confirmed the Fund for the Replacement of Animals in Medical Experiments (FRAME; Nottingham, UK; FRAME, 2005 ).

However, as with many other advances in non-animal research, this was never classified as ‘alternatives research'. In general, there is no separate field in biomedical research known as ‘alternatives research'; it is one of the highly desirable outcomes of good scientific research. The claim by anti-vivisection campaigners that research into replacements is neglected merely reflects their ignorance.

Good science and good experimental design also help to reduce the number of animals used in research as they allow scientists to gather data using the minimum number of animals required. However, good science also means that a sufficient number must be used to enable precise statistical analysis and to generate significant results to prevent the repetition of experiments and the consequent need to use more animals. In 1998, FRAME formed a Reduction Committee, in part to publicize effective reduction techniques. The data collected by the Committee so far provides information about the overall reduction in animal usage that has been brought about by the efforts of researchers worldwide ( FRAME Reduction Committee, 2005 ).

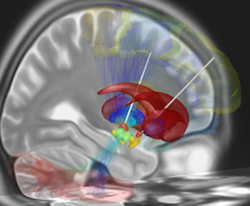

For example, screening potential anti-cancer drugs uses the so-called hollow-fibre system, in which tumour cells are grown in a tube-like polymer matrix that is implanted into mice. Drugs are then administered, the tubes removed and the number of cells determined. This system has increased the amount of data that can be obtained per animal in some studies and has therefore reduced the number of mice used ( Double, 2004 ). In neuroscience, techniques such as cooling regions of the brain instead of removing subsections, and magnetic resonance imaging, have both helped to reduce the number of laboratory animals used ( Royal Society, 2004 ).

The benefits of animal research have been enormous and it would have severe consequences for public health and medical research if it were abandoned

Matching the number of animals generated from breeding programmes to the number of animals required for research has also helped to reduce the number of surplus animals. For example, the cryopreservation of sperm and oocytes has reduced the number of genetically modified mice required for breeding programmes ( Robinson et al , 2003 ); mice lines do not have to be continuously bred if they can be regenerated from frozen cells when required.

Although animals cannot yet be completely replaced, it is important that researchers maximize reduction and refinement. Sometimes this is achieved relatively easily by improving animal husbandry and housing, for example, by enriching their environment. These simple measures within the laboratory aim to satisfy the physiological and behavioural needs of the animals and therefore maintain their well-being.

Another important factor is refining the experimental procedures themselves, and refining the management of pain. An assessment of the method of administration, the effects of the substance on the animal, and the amount of handling and restraint required should all be considered. Furthermore, careful handling of the animals, and administration of appropriate anaesthetics and analgesics during the experiment, can help to reduce any pain experienced by the animals. This culture of care is achieved not only through strict regulations but also by ensuring that animal technicians and other workers understand and adopt such regulations. Therefore, adequate training is an important aspect of the refinement of animal research, and should continually be reviewed and improved.

In conclusion, RDS considers that the use of animals in research can be ethically and morally justified. The benefits of animal research have been enormous and it would have severe consequences for public health and medical research if it were abandoned. Nevertheless, the use of the 3Rs is crucial to continuously reduce the number and suffering of animals in research. Furthermore, a good regulatory regime—as found in the UK—can help to reduce further the number of animals used. Therefore, we support a healthy and continued debate on the use of animals in research. We recognize that those who oppose animal experimentation should be free to voice their opinions democratically, and we look forward to constructive discussion in the future with organizations that share the middle ground with us.

- ABPI (2007) Facts & Statistics from the Pharmaceutical Industry . London, UK: Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. http://www.abpi.org.uk/statistics/section.asp?sect=3 [ Google Scholar ]

- AFMA (2004) New Survey Among Doctors Suggests Shift in Attitude Regarding Scientific Worth of Animal Testing . Listed as EFMA Survey of 500 General Practitioners. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Americans For Medical Advancement. www.curedisease.com [ Google Scholar ]

- Animal Procedures Committee (2003) Review of Cost–Benefit Assessment in the Use of Animals in Research . London, UK: Animal Procedures Committee. www.apc.gov.uk [ Google Scholar ]

- Double JA (2004) A pharmacological approach for the selection of potential anticancer agents . Altern Lab Anim 32 : 41–48 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DTI (2005) Science Funding SET Statistics . London, UK: Department of Trade and Industry. www.dti.gov.uk [ Google Scholar ]

- EMP (2004) Doctors Fear Animal Experiments Endanger Patients . Press release. London, UK: Europeans for Medical Progress. www.curedisease.net [ Google Scholar ]

- Flint C (2005) Report by the Animal Procedures Committee—Review of Cost Benefit Assessment in the Use of Animals in Research: Ministerial Response . London, UK: Home Office [ Google Scholar ]

- FRAME (2005) Human microdosing reduces the number of animals required for pre-clinical pharmaceutical research . Altern Lab Anim 33 : 439 [ Google Scholar ]

- FRAME Reduction Committee (2005) Bibliography of Training Materials on Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis . Nottingham, UK: Fund for the Replacement of Animals in Medical Experiments. www.frame.org.uk/reductioncommittee/bibliointro.htm [ Google Scholar ]

- Home Office (2005) Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain 2004 . London, UK: Home Office [ Google Scholar ]

- House of Lords (2002) Select Committee on Animals in Scientific Procedures, Volume I—Report . London, UK: The Stationery Office [ Google Scholar ]

- ICM (2006) Vivisection survey, conducted on behalf of BBC Newsnight. London, UK: ICM Research. www.icmresearch.co.uk

- Matthiessen L, Lucaroni B, Sachez E (2003) Towards responsible animal research . EMBO Rep 4 : 104–107 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MORI (1999a) Animals in Medicine and Science. Research Study Conducted for the Medical Research Council . London, UK: MORI. www.ipsos-mori.com [ Google Scholar ]

- MORI (1999b) The Public Consultation on Developments in the Biosciences. Executive Summary . London, UK: MORI. www.ipsos-mori.com [ Google Scholar ]

- MORI (2002) The Use of Animals in Medical Research. Research Study Conducted for the Coalition for Medical Progress . London, UK: MORI. www.ipsos-mori.com [ Google Scholar ]

- MORI (2005) Use of Animals in Medical Research. Research Study Conducted for Coalition for Medical Progress . London, UK: MORI. www.ipsos-mori.com [ Google Scholar ]

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2005) The Ethics of Research Involving Animals . London, UK: Nuffield Council on Bioethics [ Google Scholar ]

- RDS News (2006) GPs Back Animal Research . London, UK: Research Defence Society [ Google Scholar ]

- Robinson V et al. (2003) Refinement and reduction in production of genetically modified mice: Sixth report of BVAAWF/FRAME/RSPCA/UFAW Joint Working Group on Refinement . Lab Anim 37 : 1–51 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Royal Society (2004) The Use of Non-Human Animals in Research: A Guide for Scientists . London, UK: The Royal Society [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell WMS, Burch RL (1959) The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique . London, UK: Methuen [ Google Scholar ]

- TNS Healthcare (2004) Statement to the Director of Coalition for Medical Progress . London, UK: TNS Healthcare [ Google Scholar ]

- Weatherall D, Goodfellow P, Harris J, Hinde R, Johnson L, Morris R, Ross N, Skehel J, Tickell C (2006) The Use of Non-Human Primates in Research . London, UK: The Royal Society [ Google Scholar ]

- YouGov (2006) Animal Testing . Daily Telegraph Survey Results. London, UK: YouGov. www.yougov.com [ Google Scholar ]

- News/Events

- Arts and Sciences

- Design and the Arts

- Engineering

- Global Futures

- Health Solutions

- Nursing and Health Innovation

- Public Service and Community Solutions

- University College

- Thunderbird School of Global Management

- Polytechnic

- Downtown Phoenix

- Online and Extended

- Lake Havasu

- Research Park

- Washington D.C.

- Biology Bits

- Bird Finder

- Coloring Pages

- Experiments and Activities

- Games and Simulations

- Quizzes in Other Languages

- Virtual Reality (VR)

- World of Biology

- Meet Our Biologists

- Listen and Watch

- PLOSable Biology

- All About Autism

- Xs and Ys: How Our Sex Is Decided

- When Blood Types Shouldn’t Mix: Rh and Pregnancy

- What Is the Menstrual Cycle?

- Understanding Intersex

- The Mysterious Case of the Missing Periods

- Summarizing Sex Traits

- Shedding Light on Endometriosis

- Periods: What Should You Expect?

- Menstruation Matters

- Investigating In Vitro Fertilization

- Introducing the IUD

- How Fast Do Embryos Grow?

- Helpful Sex Hormones

- Getting to Know the Germ Layers

- Gender versus Biological Sex: What’s the Difference?

- Gender Identities and Expression

- Focusing on Female Infertility

- Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Pregnancy

- Ectopic Pregnancy: An Unexpected Path

- Creating Chimeras

- Confronting Human Chimerism

- Cells, Frozen in Time

- EvMed Edits

- Stories in Other Languages

- Virtual Reality

- Zoom Gallery

- Ugly Bug Galleries

- Ask a Question

- Top Questions

- Question Guidelines

- Permissions

- Information Collected

- Author and Artist Notes

- Share Ask A Biologist

- Articles & News

- Our Volunteers

- Teacher Toolbox

show/hide words to know

Computer model: a computer program designed to predict what might happen based off of collected data.

Ethical: relating to a person's moral principles.

Morals: a person's beliefs concerning what is right and wrong.

Zoologist: a person who studies animals.

Scientists learn a lot about snakes and other animals through basic research. Image by the Virginia State Park staff.

“Don’t worry, they aren’t dangerous” you hear the zoologist say as she leads you and a group of others toward an area with a number of different snakes. She removes a long snake from a larger glass enclosure and asks who would like to hold it. You take a step back, certain that holding a snake is the last thing you’d like to do.

"But how do you know they aren’t dangerous?” you ask. The zoologist looks up and smiles. She explains that scientists have studied this type of snake, and so we actually know quite a bit about it. This type of snake rarely bites and does not produce venom, so it isn’t dangerous to people. You nod along as she talks about the snakes, their natural habitats, and other details like what they eat.

Animals in the Research Process

How do we know so much about snakes or other animals? Animals are all unique, and scientists study them to learn more about them. For example, by studying snakes we have learned that they stick their tongues out because they are trying to pick up odors around them. This helps them sense food, predators, and other things that may be nearby. When research is performed to expand our understanding of something, like an animal, we call it basic research .

Scientists study animals for other reasons too. What we learn about animals can actually help us find solutions to other problems or to help people. For example, studying snakes helps us understand which ones are venomous so that humans know what kinds of snakes they shouldn't touch. Scientists also study animals to find new treatments to diseases and other ailments that affect both people and animals. If we learn what is in snake venom, we can create a medicine to give to people that have been bitten as a treatment to help them feel better. Using what we know about an animal or thing to help us solve problems or treat disease is called applied research .

Scientists use many other tools, such as computer models, in addition to animals to study different topics. Image by Andreas Horn.

No matter what type of research is being performed, scientists must consider many things when they study animals.

Do Scientists Need to Study Animals?

Of course we can learn a lot from using animals for research, but are there alternative options? Sometimes there are. For example, scientists could use some other method, like cells or computer models, to study a particular topic instead of using animals. However, for a number of reasons , scientists have found that using animals is sometimes the best way to study certain topics.

What If Scientists Harm Animals for Research?

Some research using animals only requires scientists to watch behavior or to take a few samples (like blood or saliva) from the animal. These activities may cause the animals some stress, but they are unlikely to harm the animals in any long-term way. Studies of the behavior or physiology of an animal in its natural environment is an example of such research.

In other cases, scientists may need to harm or kill an animal in order to answer a research question. For example, a study could involve removing a brain to study it more closely or giving an animal a treatment without knowing what effects it may have. While the intention is never to purposely harm animals, harm can be necessary to answer a research question.

How Do Scientists Decide When It’s OK to Study Animals?

Many animals are used in research. But there is still debate on whether they should be used for this purpose. Image by the United States Department of Agriculture.

There are many guidelines for when it’s ok to use animals in research. Scientists must write a detailed plan of why and how they plan to use animals for a research project. This information is then reviewed by other scientists and members of the public to make sure that the research animals will be used for has an important purpose. Whatever the animals are used for, the scientists also make sure to take care of animal research subjects as best as they can.

Even with rules in place about using animals for research, many people (both scientists and non-scientists) continue to debate whether animals should be used in research. This is an ethical question, or one that depends on a person's morals. Because the way each person feels about both research and animals may be different, there is a range of views on this matter.

- Some people argue that it doesn’t matter that there are rules in place to protect animals. Animals should never be used for research at all, for any reason.

- Others say we should be able to use animals for any kind of research because moving science forward is more important than the rights or well-being of animals.

- Lastly, there are people whose opinions sit somewhere in the middle. They might argue that it’s ok to use animals for research, but only in some cases. For example, if the results of the research are very likely to help treat something that affects people, then it may be okay to use animals.

Along with this debate, there are many advantages and disadvantages of doing animal research . Scientists must weigh these options when performing their research.

Additional Images via Wikimedia Commons. White rat image by Alexandroff Pogrebnoj.

Read more about: Using Animals in Research

View citation, bibliographic details:.

- Article: Using Animals in Research

- Author(s): Patrick McGurrin and Christian Ross

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: December 4, 2016

- Date accessed: March 24, 2024

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/Animal-use-in-Research

Patrick McGurrin and Christian Ross. (2016, December 04). Using Animals in Research. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved March 24, 2024 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/Animal-use-in-Research

Chicago Manual of Style

Patrick McGurrin and Christian Ross. "Using Animals in Research". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 04 December, 2016. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/Animal-use-in-Research

MLA 2017 Style

Patrick McGurrin and Christian Ross. "Using Animals in Research". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 04 Dec 2016. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 24 Mar 2024. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/Animal-use-in-Research

Animals are an important part of research. But many argue about whether it's ethical to use animals to help advance scientific progress.

Using Animals in Research

Be part of ask a biologist.

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.

Share to Google Classroom

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Introduction. All over the world, animal activists and institutions have argued whether or not research should be used on animals or should be outlawed. Philosophers believe that experiments on animals are not morally justified because they cause pain or harm the animals. A group of these philosophers believe that other alternatives are ...

Thesis Statement. Although animal research is considered unethical, painful, and harmful for the objects of experiments, animals should be used for research to understand diseases and develop effective drugs to improve public health. References. Garner, R. (2016). Animal rights: The changing debate. Springer.

This ensures that the research study design is optimised to reduce the number of animals used and reduce the trauma caused to an animal via appropriate usage of painkillers, and anaesthetics. Laboratories are expected to ensure that the animals receive proper nutrition, healthcare and treatment in support of the animal's physical and ...

This is a free essay sample available for all students. If you are looking where buy pre written papers on the topic “Should Animals Be Used For Research”, browse our private essay samples. This has been a centuries-old never-ending debate between animal rights activists and biomedical research experts with valid arguments from both sides.

There are several reasons why the use of animals is critical for biomedical research: • Animals are biologically very similar to humans. In fact, mice share more than 98% DNA with us! • Animals are susceptible to many of the same health problems as humans – cancer, diabetes, heart disease, etc. • With a shorter life cycle than humans ...

There is overwhelming scientific consensus worldwide that some animals are still needed in order to make medical progress. Where animals are used in research projects, they are used as part of a range of scientific techniques. These might include human trials, computer modelling, cell culture, statistical techniques, and others.

Almost nine out of ten GPs (88%) agreed that new medicines should be tested on animals before undergoing human trials. GP Net also asked whether GPs agreed that “medical research data can be misleading”; 93% agreed. This result puts into context the results from another poll of GPs in 2004.

Whatever the animals are used for, the scientists also make sure to take care of animal research subjects as best as they can. Even with rules in place about using animals for research, many people (both scientists and non-scientists) continue to debate whether animals should be used in research.