JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Explore the Levels of Change Management

Empower and Drive Change Management in Higher Education

Written by Timothy Slottow

Published: March 22, 2024

Research consistently supports the need to align leadership approaches with the unique needs of faculty, staff and students to achieve success. But, according to the National Student Clearinghouse , universities and colleges face challenges on a much larger scale.

- Post-secondary enrollment is over a million students below pre-pandemic levels

- The number of students dropping out before completing a degree rose to over 40 million

- Only 3.6 million college and university students graduated last year, a four-year low

Leaders in higher education are now tasked with improving these poor outcomes while undergoing significant changes to keep pace in a transforming landscape—from incorporating remote learning opportunities to integrating new technologies. According to EDUCAUSE , a third of surveyed institutions increased their central IT operating expenditure by over 30% between 2022 and 2023.

In this context, it’s clear that the leaders in higher education need to expand their focus to embrace a systemic change management approach that allows for more.

What it Means to Be an Effective Leader in the Changing Higher Education Landscape

Leaders in higher education are as diverse and multifaceted as the institutions they represent. The context of their work is equally dynamic—institutional leaders navigate a landscape of entrenched traditions, cultural change, and the relentless tide of technological innovation.

Key academic leaders, such as university presidents, provosts, deans and department chairs, are the primary sponsors of change in higher education—not to mention key C-suite stakeholders across finance, human resources, IT and academic departments. These leaders authorize major transformations and also play a major role in helping their institution realize the desired benefits of a digital transformation or policy overhaul.

Specifically, these academic leaders help coordinate the change effort from a high level, engaging constantly with project and people leaders across academic and administrative departments.

It’s crucial to remember that key stakeholders—including students, faculty, administrative staff and well-funded academics—also play an important role during times of change. While these individuals may not be the initiators of change, some are critical influencers during change, and all of them need to adopt the change for it to be successful.

Unfortunately, there are many challenges facing both the primary sponsors and key change agents in academia as these institutions try to keep up with the changing education landscape .

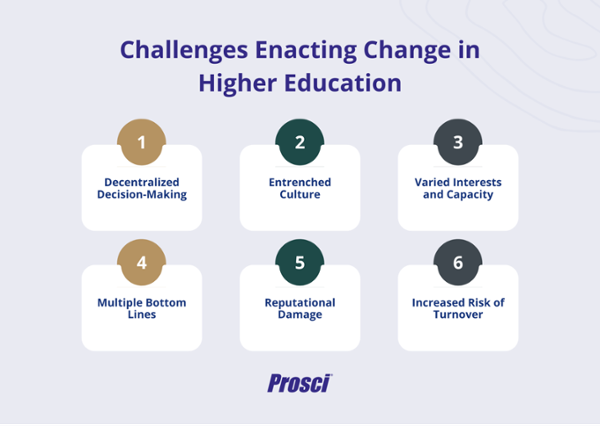

The Challenges of Leading Change in Academia

The unique culture of higher education makes the change process arduous. Unlike organizations in the business world, university and college leaders must contend with a range of unique attributes while trying to implement new policies, initiatives or infrastructure changes.

Those leading or sponsoring change initiatives in higher education often come up against many of the following issues:

Decentralized decision-making – Complex and layered governance can slow decision-making and dilute accountability. Faculty governance means deans and department chairs can have high power and autonomy.

Entrenched culture – Many leading academic institutions have been around for centuries, creating deeply rooted traditions and highly esteemed values. Furthermore, tenured faculty can often be more resistant to change than non-tenured counterparts.

Varied interests and capacity – There can be large disparities between departments regarding priorities, budgets and values. For instance, business, engineering and medical schools often have more financial resources and sway than other schools and institutes.

Multiple bottom lines – Return on Investment (ROI) is defined differently in the higher education context, especially with public funding. These institutions have the typical financial goals of large organizations but also prioritize non-financial outcomes like retention, graduation rates, growth in sponsored research, faculty recruitment/retention, faculty recognition and national rankings. The multiple stakeholders beyond students and faculty vying to influence leadership goals and decision-making can be overwhelming—e.g., alums, donors, city/state lawmakers, federal regulators, federal grant agencies, and accreditors.

Reputational damage – Many universities and colleges prioritize maintaining a strong reputation in academia and the public eye. Key stakeholders may resist significant change if they believe that failure to achieve outcomes will negatively impact that reputation.

Increased risk of losing talent – With higher education’s unique factors of tenured faculty, entrenched culture and extreme decentralization, poorly managed change efforts are more likely to lead to loss of valuable talent in key areas throughout the university.

These issues all contribute to the dismal state of change in higher education, where over 70% of large-scale initiatives fail to achieve desired outcomes. So, how can universities and colleges enact successful change in an environment where governance structures and cultures are so resistant to change?

Empowering Higher Education Leaders to Enact Change

The sheer variation in governance structures, leadership roles, and levels of autonomy interacting in academia precludes using a one-size-fits-all change management approach. It requires a structured, flexible approach to managing the change and a nuanced understanding of the institution's culture, the specific change and those impacted.

With 25 years of applied research in organizational change, Prosci has developed a framework that adapts and scales to the needs of these complex organizations and their leaders. In that time, our team has collected over two decades of longitudinal research on the dynamics of change within large institutions.

Here are three of the biggest findings observed over this time:

1. Active and visible sponsorship is the number one contributor to successful change management

Since 1998, one factor has led the way in Prosci benchmarking reports in terms of the biggest contributor to change management success— primary sponsorship .

These individuals ultimately sign off on investment in change and, while they may not lead the initiative directly, play an indispensable role in determining its outcome through active and visible promotion. Our research shows that primary sponsors who follow the ABCs of sponsorship—active and visible participation, building a coalition of sponsorship, and communicating support—strongly correlate with achieved outcomes.

2. The use of a structured change management approach is the second strongest predictor of successful change

Outside of effective primary sponsorship, there’s no more important contributor to successful organizational change than a structured change management approach.

Researchers, industry experts and consultants have developed methodologies, often based on change theory, that can be flexibly applied across different organizational contexts—even those as complex as higher education. Prominent examples include Kurt Lewin’s change model, Kotter’s 8-Step Change Process, and the Prosci ADKAR® Model.

Prosci research shows that organizations that apply effective change management are seven times more likely to meet or exceed objectives.

3. Middle management is the leading employee cohort in terms of resistance to change

Prosci research consistently points to middle managers as the most resistant to change within the organization. This resistance can culminate in technical system changes, an emotional reaction to a changing power structure, and other technical and human factors. Considering middle managers are the connective tissue between the upper level of a company and its front-line workers, overcoming this resistance is vital.

Over time, we’ve also discovered and tested a range of solutions for overcoming resistance to change within this central tier of the organization.

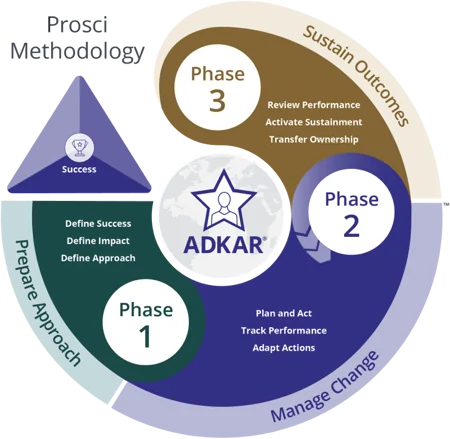

The Prosci Methodology

The Prosci Change Management Methodology stands at the forefront of enabling organizations, including higher education institutions, to navigate the complexities of change with a structured and practical approach. At the core of the Prosci Methodology and models is the understanding that successful change isn’t just about the technical solution being implemented but also about the people involved and being impacted.

Here are the structured, scalable and adaptable approaches Prosci takes to driving organizational change:

PCT Model – The Prosci Project Change Triangle (PCT) Model is a framework that highlights these four critical aspects of successful change efforts:

- Leadership/sponsorship

- Project management

- Change management

- A shared definition of success

This model underscores the importance of a shared definition of success across these areas. In higher education, leaders need to actively sponsor and support change initiatives, aligning them with the institution's strategic goals and managing the people side of change.

ADKAR Model – The Prosci ADKAR Model is a goal-oriented tool that guides individual and organizational change through five key outcomes:

- Awareness of the need for change

- Desire to participate and support the change

- Knowledge of how to change

- Ability to implement required skills and behaviors

- Reinforcement to sustain the change

This model is handy for leaders in higher education, as it helps them understand and address the individual change journey their faculty, staff, students and other stakeholders experience.

Prosci 3-Phase Process – The Prosci 3-Phase Process is a structured yet adaptable framework designed to guide organizations through successful change management. It divides the change process into three key phases:

- Phase 1 – Prepare Approach – This phase involves defining the change strategy, preparing the change management team and developing the sponsorship model.

- Phase 2 – Manage Change – During this phase, the team develops and implements plans for communication, sponsor activities, training, coaching and resistance management.

- Phase 3 – Sustain Outcomes – The final phase focuses on collecting and analyzing feedback, diagnosing gaps, managing resistance, and implementing corrective actions and recognition.

The PCT Model, ADKAR Model, and 3-Phase Process complement each other to create change. It's particularly relevant in higher education, where institutional challenges and governance structures greatly influence the success of change initiatives.

Prosci Drives Change at Leading Institutions

The Prosci Methodology has guided prestigious institutions like Texas A&M and the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) through significant change initiatives, demonstrating the power of adaptive leadership and strategic change management.

Texas A&M University (TAMU)

The Texas A&M University System needed to overhaul its 35-year-old legacy payroll system to a cloud-based version—a process that would impact 200,000 students, faculty and retirees across numerous organizations. In addition to the technical challenges this represented, the project leader faced long review cycles, a lack of alignment on the ideal solution and a decentralized process for determining finances. What appeared to be a technical process was a change that affected every level of the university ecosystem's operations.

The Prosci team stepped in to facilitate this transition, recognizing the need for a leadership approach that was directive, inclusive and repeatable. Using the Prosci 3-Phase Process and ADKAR Model to guide the process, Prosci helped TAMU’s Executive Director of Project Management with the following:

- Identification of the over 10,000 stakeholders most impacted by the project and an assessment of their leadership styles and training needs.

- Proactive management of likely areas of resistance, including repeated communication of upcoming changes and access to technical coaching.

- Strengthening ties between the A&M System sponsors and the Chief HR and Financial Officers from each university and agency through an Executive Advisory Committee (EAC).

- Application of the ADKAR Model to create training curriculum and eLearning modules for full-time employees, HR liaisons and managers.

- Facilitate collaboration between the EAC and key change agents in middle management to develop a communications plan that resonates with all impacted parties.

Read the full case study for a closer look at how TAMU’s $4.5-billion higher education network successfully navigated change in a complex, decentralized environment.

University of California, San Diego (UCSD)

UCSD, a top-15 research university worldwide, needed to change numerous processes and systems to create a more collaborative cross-discipline environment. This plan would impact all aspects of the campus. University leadership knew that a comprehensive change management plan was required to ensure that the tens of thousands affected by the transition would receive support throughout. This required a balance of leadership styles, blending democratic and transformational approaches to engage a diverse academic community.

UC San Diego partnered with Prosci to speed up the transition process and leverage our decades of experience enacting complex change. Working closely with the Staff Education and Development team, Prosci helped drive change in the following ways:

- Preparing UCSD change agents for the necessary large group training sessions through the Prosci Train-the-Trainer Program

- Facilitating award-winning development days that empowered 90% of the 500 attendees with new knowledge and tools

- Building off the success of development days by promoting and regularly hosting change management training and services on campus

- Augmenting change management training with smaller-scale webinars based on pressing issues like resistance to change and sponsor engagement

UCSD's initiative led to a more change-capable organization, where the principles of change management became embedded in the university's culture, paving the way for ongoing and future transformations.

Read the full case study to see how Prosci helped UC San Diego empower key leaders to embed change management materials throughout their campus and foster a pro-change environment.

Training and Supporting Key Change Agents in Higher Education

Prosci empowers leaders in various organizational contexts, including higher education, to drive and manage change effectively . Prosci has been applying research on best practices in change management for over 25 years, and we base our structured methodology and analytic tools on that research.

With decades of experience, Prosci offers comprehensive enterprise training and supportive advisory services tailored to meet the unique challenges and dynamics of leading institutions like Texas A&M and UCSD. These resources are invaluable for institutions seeking to foster transformational leadership and successfully navigate the complexities of change.

To explore how Prosci can assist your institution in harnessing effective leadership for change management, visit the Enterprise Training and Advisory Services pages for more information and guidance.

Timothy Slottow

Tim Slottow is a former C-suite executive with more than three decades of experience sponsoring enterprise-wide changes while driving organizational performance in a variety of industries. The former President of the University of Phoenix, and EVP and CFO for the University of Michigan, Tim has successfully guided teams through disruptive changes, including mergers and acquisitions, organizational restructurings, and cost reduction initiatives. Tim is an Aspen Institute Fellow and frequent lecturer who has served on multiple boards in the higher education, insurance and healthcare sectors.

See all posts from Timothy Slottow

You Might Also Like

Enterprise - 7 MINS

Supporting Project Results With eLearning

6 Notable Shifts in the Best Practices in Change Management

Subscribe here.

- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Staff portal (Inside the department)

- Student portal

- Key links for students

Other users

- Forgot password

Notifications

{{item.title}}, my essentials, ask for help, contact edconnect, directory a to z, how to guides, leading curriculum k–12, change management research tools.

Lead professional conversations about effective curriculum implementation practices and change management in your school or professional learning network.

Use these research snapshots, text-based protocols, and core thinking routines for leaders to prompt professional conversations. The research snapshots support school leadership teams on their journey through the ‘Phases of Curriculum Implementation ’.

About this resource

Purpose of resource.

This research snapshot is part of the ‘ Leading curriculum Implementation toolkit '. It supports leaders, and aspiring leaders, to explore and reflect on research about effective approaches to curriculum implementation.

Target audience

School leadership teams and aspiring leaders can use this resource to initiate professional dialogue and build collective understanding amongst colleagues.

When and how to use

School leadership teams and aspiring leaders might use the research snapshot to:

- reflect on their own practice to prepare for new curriculum implementation

- mentor new and aspiring leaders through the phases of curriculum implementation

- promote discussion in their leadership team on how best to support or contextualise curriculum reform in their school.

Text-based protocols and core thinking routines can be used alongside the research snapshot to foster discussion and build collective understanding of effective approaches to curriculum implementation.

Research base

The evidence base for this resource is:

- Dao L, (2021) ‘Challenges and enablers encountered by a curriculum leadership team in implementing the national curriculum in one Australian school’, Leading and Managing, 27 (1): 77-98.

Use the pdf link or follow these steps

- Use CESE accessing databases

- Select Informit (How do I log in)

- Insert the article name and search.

- Select the article and download the pdf.

- High Impact Professional Learning (HIPL) .

Email questions, comments, and feedback about this resource to [email protected] using the subject line ‘Leading Curriculum Implementation Research toolkit’.

Alignment to system priorities and/or needs – School Excellence Policy and School Excellence Procedure

Alignment to School Excellence Framework – ‘Instructional leadership’ and ‘High expectations culture’ elements in the Leading domain as well as the ‘Learning and development’ and ‘Collaborative practices and feedback’ elements of the Teaching domain.

Alignment with the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers – 6.2.4 and 6.3.4

Consulted with: Strategic Delivery representatives, Principal School Leadership representatives

Reviewed by: CEYPL Director and CSL Director

Managing curriculum change

Research article – Jones, C and Anderson M (2001) ‘ Managing curriculum change ’. Learning and Skills Development Agency, London, accessed 2 September 2022.

‘Change management involves many factors: quality, resources, staff, students, and funding, to name a few. But above all, it is about processes – how to get to where you want to be.’ (p.9)

This article explores strategies for change management in an international context. The language has been adapted for the New South Wales context.

Research overview

Giving high priority to curriculum change is the first step to creating an environment where effective change can take place.

- Ensure changes to the curriculum are explicit in Strategic Improvement Plans.

- Provide a clear picture of how the change will affect staff, students, and parents.

- Allocate school leaders and teachers responsibility for making change happen.

- Place curriculum change at the top of agendas for meetings.

- Provide adequate resources to make sure that the change happens.

Teaching staff are more likely to accept changes to the curriculum if they are given additional support during implementation phases.

- Divide big changes into manageable steps.

- Develop the coaching skills of middle leaders.

- Demonstrate commitment to change by being visible and available for staff.

As with anything, curriculum change is most effective when it is planned.

- Be realistic about the timescales and resources needed for effective change.

- Look for champions who can motivate others.

- Define what is non-negotiable and what is fixed.

- Include a plan for clear communication.

Effective leadership teams, who lead from the front by setting an example of hard work, flexibility, responsiveness, and commitment have greater success when implementing new curriculum.

- Explain what the change means in positive terms for staff, parents, and students.

- Seek opportunities to talk to staff and community about the change.

Teachers need to develop ownership of the change and the process for curriculum initiatives and quality to be effective.

- Ensure staff understand the ‘why’ for change.

- Give teaching staff an opportunity to share responsibility for shaping curriculum change.

Using the expertise of staff can have positive effects on instigating change and improve staff morale.

- Look for evidence of previous success in curriculum change.

- Build teams that include individuals with recognised expertise.

- Map people skills to specific elements of curriculum change at an early stage of planning.

It is vital that leaders have professional credibility in the eyes of teaching staff.

- Recognise that perceptions influence behaviour.

- Communicate with students about curriculum change and how this will impact them.

Staff need to be kept informed of curriculum change and take part in regular professional development activities. Invest in your teachers.

- Implement action plans.

- Provide staff with appropriate information to keep them fully informed.

- Ensure that staff have the necessary professional development to meet the changing needs of the curriculum.

Professional discussion and reflection prompts

- As a leader, which strategies for managing curriculum change are already in place in your context? Which strategies could be strengthened to effectively implement curriculum change?

- How might you modify your current systems and processes to incorporate new strategies for managing curriculum change in your context?

Challenges and enablers

Research article – Dao L, (2021) ‘Challenges and enablers encountered by a curriculum leadership team in implementing the national curriculum in one Australian school’, Leading and Managing, 27 (1): 77-98.

‘Change is non-linear, complex and multi-dimensional.’ (p 81)

This article explores the change process for implementation of large-scale mandated curriculum change. Internal and external factors can enable, or act as barriers, to successful implementation. Teacher belief, values and motivation also influence effective implementation of educational change. The author uses Sergiovanni’s (1995) change process model to explore the complexity and interaction of different factors when seeking to effectively implement change.

Sergiovanni suggests change is dependent on four interacting ‘units of change’:

- political system.

Challenges to effective curriculum implementation are the:

- need to provide practical support for teachers

- time to plan and develop programs, systems and processes

- availability of appropriate syllabus-aligned resources

- access to professional learning aligned to new syllabuses

- willingness and opportunities to collaborate with colleagues

- effective management of workload issues when implementing multiple syllabuses.

Enablers for effective curriculum implementation include:

- collaboration when planning for implementation

- additional release time to support implementation planning

- resources to support implementation, such as digital curriculum, work samples

- formal and informal (professional dialogue and reading) professional learning both in school and through networks

- As a leader, reflect on the four ‘units of change’. How might they interact to influence implementation of educational change in your context?

- What enablers can you identify in your context?

- What challenges could impact effective implementation of change in your context?

- As a leader, what resources do you have available to overcome these challenges and enable effective curriculum implementation?

- Teaching and learning

Business Unit:

- Curriculum and Reform

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Critical Steps in the Change Management Process

- 19 Mar 2020

Businesses must constantly evolve and adapt to meet a variety of challenges—from changes in technology, to the rise of new competitors, to a shift in laws, regulations, or underlying economic trends. Failure to do so could lead to stagnation or, worse, failure.

Approximately 50 percent of all organizational change initiatives are unsuccessful, highlighting why knowing how to plan for, coordinate, and carry out change is a valuable skill for managers and business leaders alike.

Have you been tasked with managing a significant change initiative for your organization? Would you like to demonstrate that you’re capable of spearheading such an initiative the next time one arises? Here’s an overview of what change management is, the key steps in the process, and actions you can take to develop your managerial skills and become more effective in your role.

Access your free e-book today.

What is Change Management?

Organizational change refers broadly to the actions a business takes to change or adjust a significant component of its organization. This may include company culture, internal processes, underlying technology or infrastructure, corporate hierarchy, or another critical aspect.

Organizational change can be either adaptive or transformational:

- Adaptive changes are small, gradual, iterative changes that an organization undertakes to evolve its products, processes, workflows, and strategies over time. Hiring a new team member to address increased demand or implementing a new work-from-home policy to attract more qualified job applicants are both examples of adaptive changes.

- Transformational changes are larger in scale and scope and often signify a dramatic and, occasionally sudden, departure from the status quo. Launching a new product or business division, or deciding to expand internationally, are examples of transformational change.

Change management is the process of guiding organizational change to fruition, from the earliest stages of conception and preparation, through implementation and, finally, to resolution.

As a leader, it’s essential to understand the change management process to ensure your entire organization can navigate transitions smoothly. Doing so can determine the potential impact of any organizational changes and prepare your teams accordingly. When your team is prepared, you can ensure everyone is on the same page, create a safe environment, and engage the entire team toward a common goal.

Change processes have a set of starting conditions (point A) and a functional endpoint (point B). The process in between is dynamic and unfolds in stages. Here’s a summary of the key steps in the change management process.

Check out our video on the change management process below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

5 Steps in the Change Management Process

1. prepare the organization for change.

For an organization to successfully pursue and implement change, it must be prepared both logistically and culturally. Before delving into logistics, cultural preparation must first take place to achieve the best business outcome.

In the preparation phase, the manager is focused on helping employees recognize and understand the need for change. They raise awareness of the various challenges or problems facing the organization that are acting as forces of change and generating dissatisfaction with the status quo. Gaining this initial buy-in from employees who will help implement the change can remove friction and resistance later on.

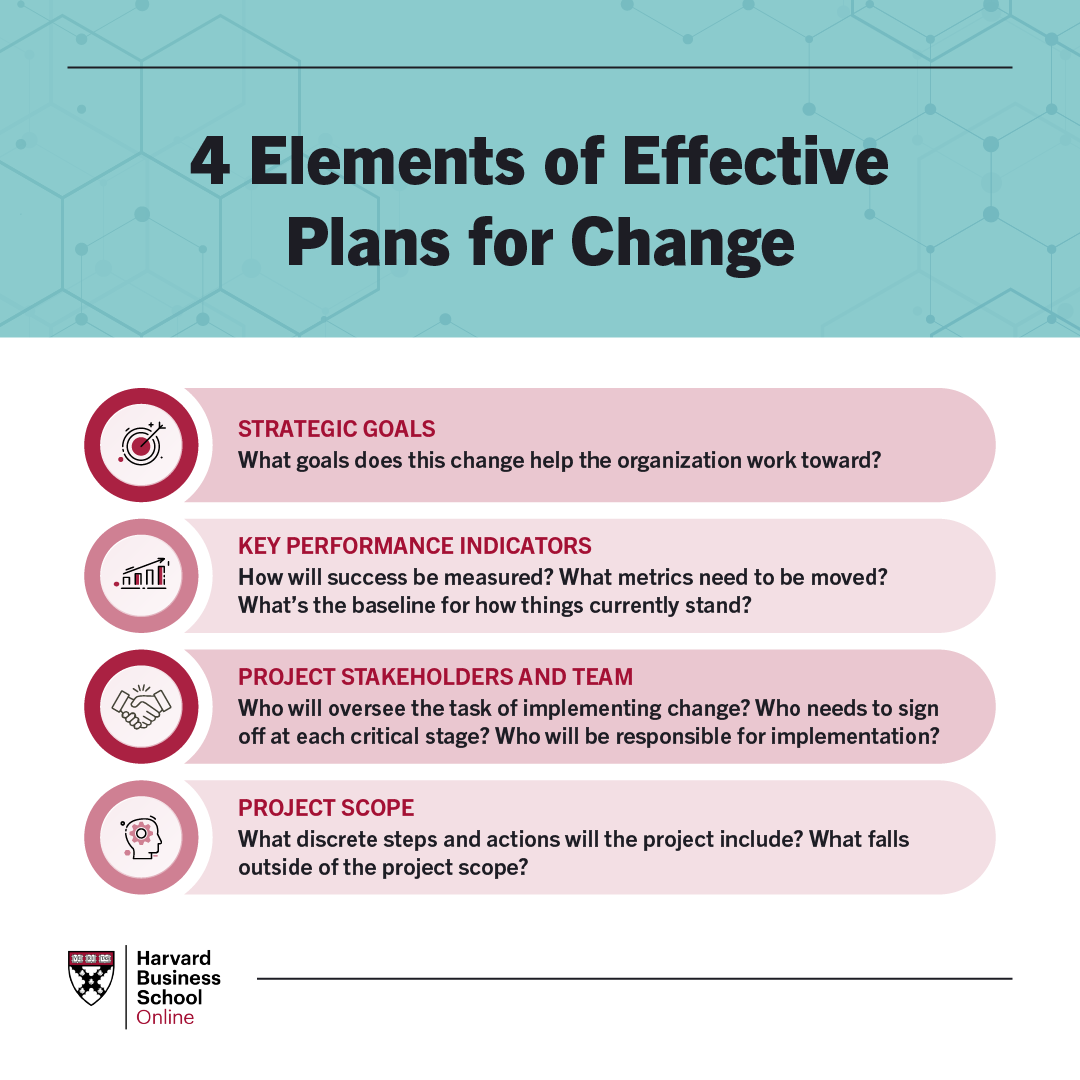

2. Craft a Vision and Plan for Change

Once the organization is ready to embrace change, managers must develop a thorough, realistic, and strategic plan for bringing it about.

The plan should detail:

- Strategic goals: What goals does this change help the organization work toward?

- Key performance indicators: How will success be measured? What metrics need to be moved? What’s the baseline for how things currently stand?

- Project stakeholders and team: Who will oversee the task of implementing change? Who needs to sign off at each critical stage? Who will be responsible for implementation?

- Project scope: What discrete steps and actions will the project include? What falls outside of the project scope?

While it’s important to have a structured approach, the plan should also account for any unknowns or roadblocks that could arise during the implementation process and would require agility and flexibility to overcome.

3. Implement the Changes

After the plan has been created, all that remains is to follow the steps outlined within it to implement the required change. Whether that involves changes to the company’s structure, strategy, systems, processes, employee behaviors, or other aspects will depend on the specifics of the initiative.

During the implementation process, change managers must be focused on empowering their employees to take the necessary steps to achieve the goals of the initiative and celebrate any short-term wins. They should also do their best to anticipate roadblocks and prevent, remove, or mitigate them once identified. Repeated communication of the organization’s vision is critical throughout the implementation process to remind team members why change is being pursued.

4. Embed Changes Within Company Culture and Practices

Once the change initiative has been completed, change managers must prevent a reversion to the prior state or status quo. This is particularly important for organizational change related to business processes such as workflows, culture, and strategy formulation. Without an adequate plan, employees may backslide into the “old way” of doing things, particularly during the transitory period.

By embedding changes within the company’s culture and practices, it becomes more difficult for backsliding to occur. New organizational structures, controls, and reward systems should all be considered as tools to help change stick.

5. Review Progress and Analyze Results

Just because a change initiative is complete doesn’t mean it was successful. Conducting analysis and review, or a “project post mortem,” can help business leaders understand whether a change initiative was a success, failure, or mixed result. It can also offer valuable insights and lessons that can be leveraged in future change efforts.

Ask yourself questions like: Were project goals met? If yes, can this success be replicated elsewhere? If not, what went wrong?

The Key to Successful Change for Managers

While no two change initiatives are the same, they typically follow a similar process. To effectively manage change, managers and business leaders must thoroughly understand the steps involved.

Some other tips for managing organizational change include asking yourself questions like:

- Do you understand the forces making change necessary? Without this understanding, it can be difficult to effectively address the underlying causes that have necessitated change, hampering your ability to succeed.

- Do you have a plan? Without a detailed plan and defined strategy, it can be difficult to usher a change initiative through to completion.

- How will you communicate? Successful change management requires effective communication with both your team members and key stakeholders. Designing a communication strategy that acknowledges this reality is critical.

- Have you identified potential roadblocks? While it’s impossible to predict everything that might potentially go wrong with a project, taking the time to anticipate potential barriers and devise mitigation strategies before you get started is generally a good idea.

How to Lead Change Management Successfully

If you’ve been asked to lead a change initiative within your organization, or you’d like to position yourself to oversee such projects in the future, it’s critical to begin laying the groundwork for success by developing the skills that can equip you to do the job.

Completing an online management course can be an effective way of developing those skills and lead to several other benefits . When evaluating your options for training, seek a program that aligns with your personal and professional goals; for example, one that emphasizes organizational change.

Do you want to become a more effective leader and manager? Explore Leadership Principles , Management Essentials , and Organizational Leadership —three of our online leadership and management courses —to learn how you can take charge of your professional development and accelerate your career. Not sure which course is the right fit? Download our free flowchart .

This post was updated on August 8, 2023. It was originally published on March 19, 2020.

About the Author

Change Management: From Theory to Practice

- Original Paper

- Published: 09 September 2022

- Volume 67 , pages 189–197, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Jeffrey Phillips ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0708-6460 1 &

- James D. Klein 2

40k Accesses

17 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article presents a set of change management strategies found across several models and frameworks and identifies how frequently change management practitioners implement these strategies in practice. We searched the literature to identify 15 common strategies found in 16 different change management models and frameworks. We also created a questionnaire based on the literature and distributed it to change management practitioners. Findings suggest that strategies related to communication, stakeholder involvement, encouragement, organizational culture, vision, and mission should be used when implementing organizational change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reactions towards organizational change: a systematic literature review

Khai Wah Khaw, Alhamzah Alnoor, … Nadia A. Atshan

Characteristics of successful changes in health care organizations: an interview study with physicians, registered nurses and assistant nurses

Per Nilsen, Ida Seing, … Kristina Schildmeijer

Exploring the gap between research and practice in human resource management (HRM): a scoping review and agenda for future research

Philip Negt & Axel Haunschild

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Organizations must change to survive. There are many approaches to influence change; these differences require change managers to consider various strategies that increase acceptance and reduce barriers. A change manager is responsible for planning, developing, leading, evaluating, assessing, supporting, and sustaining a change implementation. Change management consists of models and strategies to help employees accept new organizational developments.

Change management practitioners and academic researchers view organizational change differently (Hughes, 2007 ; Pollack & Pollack, 2015 ). Saka ( 2003 ) states, “there is a gap between what the rational-linear change management approach prescribes and what change agents do” (p. 483). This disconnect may make it difficult to determine the suitability and appropriateness of using different techniques to promote change (Pollack & Pollack, 2015 ). Hughes ( 2007 ) thinks that practitioners and academics may have trouble communicating because they use different terms. Whereas academics use the terms, models, theories, and concepts, practitioners use tools and techniques. A tool is a stand-alone application, and a technique is an integrated approach (Dale & McQuater, 1998 ). Hughes ( 2007 ) expresses that classifying change management tools and techniques can help academics identify what practitioners do in the field and evaluate the effectiveness of practitioners’ implementations.

There is little empirical evidence that supports a preferred change management model (Hallencreutz & Turner, 2011 ). However, there are many similar strategies found across change management models (Raineri, 2011 ). Bamford and Forrester’s ( 2003 ) case study showed that “[change] managers in a company generally ignored the popular change literature” (p. 560). The authors followed Pettigrew’s ( 1987 ) suggestions that change managers should not use abstract theories; instead, they should relate change theories to the context of the change. Neves’ ( 2009 ) exploratory factor analysis of employees experiencing the implementation of a new performance appraisal system at a public university suggested that (a) change appropriateness (if the employee felt the change was beneficial to the organization) was positively related with affective commitment (how much the employee liked their job), and (b) affective commitment mediated the relationship between change appropriateness and individual change (how much the employee shifted to the new system). It is unlikely that there is a universal change management approach that works in all settings (Saka, 2003 ). Because change is chaotic, one specific model or framework may not be useful in multiple contexts (Buchanan & Boddy, 1992 ; Pettigrew & Whipp, 1991 ). This requires change managers to consider various approaches for different implementations (Pettigrew, 1987 ). Change managers may face uncertainties that cannot be addressed by a planned sequence of steps (Carnall, 2007 ; Pettigrew & Whipp, 1991 ). Different stakeholders within an organization may complete steps at different times (Pollack & Pollack, 2015 ). Although there may not be one perspective change management approach, many models and frameworks consist of similar change management strategies.

Anderson and Ackerman Anderson ( 2001 ) discuss the differences between change frameworks and change process models. They state that a change framework identifies topics that are relevant to the change and explains the procedures that organizations should acknowledge during the change. However, the framework does not provide details about how to accomplish the steps of the change or the sequence in which the change manager should perform the steps. Additionally, Anderson and Ackerman Anderson ( 2001 ) explain that change process models describe what actions are necessary to accomplish the change and the order in which to facilitate the actions. Whereas frameworks may identify variables or theories required to promote change, models focus on the specific processes that lead to change. Based on the literature, we define a change strategy as a process or action from a model or framework. Multiple models and frameworks contain similar strategies. Change managers use models and frameworks contextually; some change management strategies may be used across numerous models and frameworks.

The purpose of this article is to present a common set of change management strategies found across numerous models and frameworks and identify how frequently change management practitioners implement these common strategies in practice. We also compare current practice with models and frameworks from the literature. Some change management models and frameworks have been around for decades and others are more recent. This comparison may assist practitioners and theorists to consider different strategies that fall outside a specific model.

Common Strategies in the Change Management Literature

We examined highly-cited publications ( n > 1000 citations) from the last 20 years, business websites, and university websites to select organizational change management models and frameworks. First, we searched two indexes—Google Scholar and Web of Science’s Social Science Citation Index. We used the following keywords in both indexes: “change management” OR “organizational change” OR “organizational development” AND (models or frameworks). Additionally, we used the same search terms in a Google search to identify models mentioned on university and business websites. This helped us identify change management models that had less presence in popular research. We only included models and frameworks from our search results that were mentioned on multiple websites. We reached saturation when multiple publications stopped identifying new models and frameworks.

After we identified the models and frameworks, we analyzed the original publications by the authors to identify observable strategies included in the models and frameworks. We coded the strategies by comparing new strategies with our previously coded strategies, and we combined similar strategies or created a new strategy. Our list of strategies was not exhaustive, but we included the most common strategies found in the publications. Finally, we omitted publications that did not provide details about the change management strategies. Although many of these publications were highly cited and identified change implementation processes or phases, the authors did not identify a specific strategy.

Table 1 shows the 16 models and frameworks that we analyzed and the 15 common strategies that we identified from this analysis. Ackerman-Anderson and Anderson ( 2001 ) believe that it is important for process models to consider organizational imperatives as well as human dynamics and needs. Therefore, the list of strategies considers organizational imperatives such as create a vision for the change that aligns with the organization’s mission and strategies regarding human dynamics and needs such as listen to employees’ concerns about the change. We have presented the strategies in order of how frequently the strategies appear in the models and frameworks. Table 1 only includes strategies found in at least six of the models or frameworks.

Strategies Used by Change Managers

We developed an online questionnaire to determine how frequently change managers used the strategies identified in our review of the literature. The Qualtrics-hosted survey consisted of 28 questions including sliding-scale, multiple-choice, and Likert-type items. Demographic questions focused on (a) how long the participant had been involved in the practice of change management, (b) how many change projects the participant had led, (c) the types of industries in which the participant led change implementations, (d) what percentage of job responsibilities involved working as a change manager and a project manager, and (e) where the participant learned to conduct change management. Twenty-one Likert-type items asked how often the participant used the strategies identified by our review of common change management models and frameworks. Participants could select never, sometimes, most of the time, and always. The Cronbach’s Alpha of the Likert-scale questions was 0.86.

The procedures for the questionnaire followed the steps suggested by Gall et al. ( 2003 ). The first steps were to define the research objectives, select the sample, and design the questionnaire format. The fourth step was to pretest the questionnaire. We conducted cognitive laboratory interviews by sending the questionnaire and interview questions to one person who was in the field of change management, one person who was in the field of performance improvement, and one person who was in the field of survey development (Fowler, 2014 ). We met with the reviewers through Zoom to evaluate the questionnaire by asking them to read the directions and each item for clarity. Then, reviewers were directed to point out mistakes or areas of confusion. Having multiple people review the survey instruments improved the reliability of the responses (Fowler, 2014 ).

We used purposeful sampling to distribute the online questionnaire throughout the following organizations: the Association for Talent Development (ATD), Change Management Institute (CMI), and the International Society for Performance Improvement (ISPI). We also launched a call for participation to department chairs of United States universities who had Instructional Systems Design graduate programs with a focus on Performance Improvement. We used snowball sampling to gain participants by requesting that the department chairs forward the questionnaire to practitioners who had led at least one organizational change.

Table 2 provides a summary of the characteristics of the 49 participants who completed the questionnaire. Most had over ten years of experience practicing change management ( n = 37) and had completed over ten change projects ( n = 32). The participants learned how to conduct change management on-the-job ( n = 47), through books ( n = 31), through academic journal articles ( n = 22), and from college or university courses ( n = 20). The participants had worked in 13 different industries.

Table 3 shows how frequently participants indicated that they used the change management strategies included on the questionnaire. Forty or more participants said they used the following strategies most often or always: (1) Asked members of senior leadership to support the change; (2) Listened to managers’ concerns about the change; (3) Aligned an intended change with an organization’s mission; (4) Listened to employees’ concerns about the change; (5) Aligned an intended change with an organization’s vision; (6) Created measurable short-term goals; (7) Asked managers for feedback to improve the change, and (8) Focused on organizational culture.

Table 4 identifies how frequently the strategies appeared in the models and frameworks and the rate at which practitioners indicated they used the strategies most often or always. The strategies found in the top 25% of both ( n > 36 for practitioner use and n > 11 in models and frameworks) focused on communication, including senior leadership and the employees in change decisions, aligning the change with the vision and mission of the organization, and focusing on organizational culture. Practitioners used several strategies more commonly than the literature suggested, especially concerning the topic of middle management. Practitioners focused on listening to middle managers’ concerns about the change, asking managers for feedback to improve the change, and ensuring that managers were trained to promote the change. Meanwhile, practitioners did not engage in the following strategies as often as the models and frameworks suggested that they should: provide all members of the organization with clear communication about the change, distinguish the differences between leadership and management, reward new behavior, and include employees in change decisions.

Common Strategies Used by Practitioners and Found in the Literature

The purpose of this article was to present a common set of change management strategies found across numerous models and frameworks and to identify how frequently change management practitioners implement these common strategies in practice. The five common change management strategies were the following: communicate about the change, involve stakeholders at all levels of the organization, focus on organizational culture, consider the organization’s mission and vision, and provide encouragement and incentives to change. Below we discuss our findings with an eye toward presenting a few key recommendations for change management.

Communicate About the Change

Communication is an umbrella term that can include messaging, networking, and negotiating (Buchanan & Boddy, 1992 ). Our findings revealed that communication is essential for change management. All the models and frameworks we examined suggested that change managers should provide members of the organization with clear communication about the change. It is interesting that approximately 33% of questionnaire respondents indicated that they sometimes, rather than always or most of the time, notified all members of the organization about the change. This may be the result of change managers communicating through organizational leaders. Instead of communicating directly with everyone in the organization, some participants may have used senior leadership, middle management, or subgroups to communicate the change. Messages sent to employees from leaders can effectively promote change. Regardless of who is responsible for communication, someone in the organization should explain why the change is happening (Connor et al., 2003 ; Doyle & Brady, 2018 ; Hiatt, 2006 ; Kotter, 2012 ) and provide clear communication throughout the entire change implementation (McKinsey & Company, 2008 ; Mento et al., 2002 ).

Involve Stakeholders at All Levels of the Organization

Our results indicate that change managers should involve senior leaders, managers, as well as employees during a change initiative. The items on the questionnaire were based on a review of common change management models and frameworks and many related to some form of stakeholder involvement. Of these strategies, over half were used often by 50% or more respondents. They focused on actions like gaining support from leaders, listening to and getting feedback from managers and employees, and adjusting strategies based on stakeholder input.

Whereas the models and frameworks often identified strategies regarding senior leadership and employees, it is interesting that questionnaire respondents indicated that they often implemented strategies involving middle management in a change implementation. This aligns with Bamford and Forrester’s ( 2003 ) research describing how middle managers are important communicators of change and provide an organization with the direction for the change. However, the participants did not develop managers into leaders as often as the literature proposed. Burnes and By ( 2012 ) expressed that leadership is essential to promote change and mention how the change management field has failed to focus on leadership as much as it should.

Focus on Organizational Culture

All but one of the models and frameworks we analyzed indicated that change managers should focus on changing the culture of an organization and more than 75% of questionnaire respondents revealed that they implemented this strategy always or most of the time. Organizational culture affects the acceptance of change. Changing the organizational culture can prevent employees from returning to the previous status quo (Bullock & Batten, 1985 ; Kotter, 2012 ; Mento et al., 2002 ). Some authors have different views on how to change an organization’s culture. For example, Burnes ( 2000 ) thinks that change managers should focus on employees who were resistant to the change while Hiatt ( 2006 ) suggests that change managers should replicate what strategies they used in the past to change the culture. Change managers require open support and commitment from managers to lead a culture change (Phillips, 2021 ).

In addition, Pless and Maak ( 2004 ) describe the importance of creating a culture of inclusion where diverse viewpoints help an organization reach its organizational objectives. Yet less than half of the participants indicated that they often focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Change managers should consider diverse viewpoints when implementing change, especially for organizations whose vision promotes a diverse and inclusive workforce.

Consider the Organization’s Mission and Vision

Several of the models and frameworks we examined mentioned that change managers should consider the mission and vision of the organization (Cummings & Worley, 1993 ; Hiatt, 2006 ; Kotter, 2012 ; Polk, 2011 ). Furthermore, aligning the change with the organization’s mission and vision were among the strategies most often implemented by participants. This was the second most common strategy both used by participants and found in the models and frameworks. A mission of an organization may include its beliefs, values, priorities, strengths, and desired public image (Cummings & Worley, 1993 ). Leaders are expected to adhere to a company’s values and mission (Strebel, 1996 ).

Provide Encouragement and Incentives to Change

Most of the change management models and frameworks suggested that organizations should reward new behavior, yet most respondents said they did not provide incentives to change. About 75% of participants did indicate that they frequently gave encouragement to employees about the change. The questionnaire may have confused participants by suggesting that they provide incentives before the change occurs. Additionally, respondents may have associated incentives with monetary compensation. Employee training can be considered an incentive, and many participants confirmed that they provided employees and managers with training. More information is needed to determine why the participants did not provide incentives and what the participants defined as rewards.

Future Conversations Between Practitioners and Researchers

Table 4 identified five strategies that practitioners used more often than the models and frameworks suggested and four strategies that were suggested more often by the models and frameworks than used by practitioners. One strategy that showed the largest difference was provided employees with incentives to implement the change. Although 81% of the selected models and frameworks suggested that practitioners should provide employees with incentives, only 25% of the practitioners identified that they provided incentives always and most of the time. Conversations between theorists and practitioners could determine if these differences occur because each group uses different terms (Hughes, 2007 ) or if practitioners just implement change differently than theorists suggest (Saka, 2003 ).

Additionally, conversations between theorists and practitioners may help promote improvements in the field of change management. For example, practitioners were split on how often they promoted DEI, and the selected models and frameworks did not focus on DEI in change implementations. Conversations between the two groups would help theorists understand what practitioners are doing to advance the field of change management. These conversations may encourage theorists to modify their models and frameworks to include modern approaches to change.

Limitations

The models and frameworks included in this systematic review were found through academic research and websites on the topic of change management. We did not include strategies contained on websites from change management organizations. Therefore, the identified strategies could skew towards approaches favored by theorists instead of practitioners. Additionally, we used specific publications to identify the strategies found in the models and frameworks. Any amendments to the cited models or frameworks found in future publications could not be included in this research.

We distributed this questionnaire in August 2020. Several participants mentioned that they were not currently conducting change management implementations because of global lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Because it can take years to complete a change management implementation (Phillips, 2021 ), this research does not describe how COVID-19 altered the strategies used by the participants. Furthermore, participants were not provided with definitions of the strategies. Their interpretations of the strategies may differ from the definitions found in the academic literature.

Future Research

Future research should expand upon what strategies the practitioners use to determine (a) how the practitioners use the strategies, and (b) the reasons why practitioners use certain strategies. Participants identified several strategies that they did not use as often as the literature suggested (e.g., provide employees with incentives and adjust the change implementation because of reactions from employees). Future research should investigate why practitioners are not implementing these strategies often.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic may have changed how practitioners implemented change management strategies. Future research should investigate if practitioners have added new strategies or changed the frequency in which they identified using the strategies found in this research.

Our aim was to identify a common set of change management strategies found across several models and frameworks and to identify how frequently change management practitioners implement these strategies in practice. While our findings relate to specific models, frameworks, and strategies, we caution readers to consider the environment and situation where the change will occur. Therefore, strategies should not be selected for implementation based on their inclusion in highly cited models and frameworks. Our study identified strategies found in the literature and used by change managers, but it does not predict that specific strategies are more likely to promote a successful organizational change. Although we have presented several strategies, we do not suggest combining these strategies to create a new framework. Instead, these strategies should be used to promote conversation between practitioners and theorists. Additionally, we do not suggest that one model or framework is superior to others because it contains more strategies currently used by practitioners. Evaluating the effectiveness of a model or framework by how many common strategies it contains gives an advantage to models and frameworks that contain the most strategies. Instead, this research identifies what practitioners are doing in the field to steer change management literature towards the strategies that are most used to promote change.

Ackerman-Anderson, L. S., & Anderson, D. (2001). The change leader’s roadmap: How to navigate your organization’s transformation . Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Anderson, D., & Ackerman Anderson, L. S. (2001). Beyond change management: Advanced strategies for today’s transformational leaders . Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Bakari, H., Hunjra, A. I., & Niazi, G. S. K. (2017). How does authentic leadership influence planned organizational change? The role of employees’ perceptions: Integration of theory of planned behavior and Lewin’s three step model. Journal of Change Management, 17 (2), 155–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2017.1299370

Article Google Scholar

Bamford, D. R., & Forrester, P. L. (2003). Managing planned and emergent change within an operations management environment. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 23 (5), 546–564. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570310471857

Beckhard, R., & Harris, R. T. (1987). Organizational transitions: Managing complex change (2 nd ed.). Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Bridges, W. (1991). Managing transitions: Making the most of change . Perseus Books.

Buchanan, D. A., & Boddy, D. (1992). The expertise of the change agent . Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Bullock, R. J., & Batten, D. (1985). It's just a phase we're going through: A review and synthesis of OD phase analysis. Group & Organization Studies, 10 (4), 383–412.

Burnes, B. (2000). Managing change: A strategic approach to organisational dynamics (3 rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

Burnes, B., & By, R. T. (2012). Leadership and change: The case for greater ethical clarity. Journal of Business Ethics, 108 (2), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1088-2

Carnall, C. A. (2007). Managing change in organizations (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Connor, P. E., Lake, L. K., & Stackman, R. W. (2003). Managing organizational change (3 rd ed.). Praeger Publishers.

Cox, A. M., Pinfield, S., & Rutter, S. (2019). Extending McKinsey’s 7S model to understand strategic alignment in academic libraries. Library Management, 40 (5), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-06-2018-0052

Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (1993). Organizational development and change (5 th ed.). West Publishing Company.

Dale, B. & McQuater, R. (1998) Managing business improvement and quality: Implementing key tools and techniques . Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Doyle, T., & Brady, M. (2018). Reframing the university as an emergent organisation: Implications for strategic management and leadership in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 40 (4), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1478608

Fowler, F. J., Jr. (2014). Survey research methods: Applied social research methods (5 th ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

French, W. L., & Bell, C. H. Jr. (1999). Organizational development: Behavioral science interventions for organizational improvement (6 th ed.). Prentice-Hall Inc.

Gall, M., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2003). Educational research: An introduction (7 th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Hallencreutz, J., & Turner, D.-M. (2011). Exploring organizational change best practice: Are there any clear-cut models and definitions? International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences , 3 (1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566691111115081

Hiatt, J. M. (2006). ADKAR: A model for change in business, government, and our community . Prosci Learning Publications.

Hughes, M. (2007). The tools and techniques of change management. Journal of Change Management, 7 (1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010701309435

Kanter, R. M., Stein, B. A., & Jick, T. D. (1992). The challenge of organizational change . The Free Press.

Kotter, J. P. (2012). Leading change . Harvard Business Review Press.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers . Harper & Brothers Publishers.

Luecke, R. (2003). Managing change and transition . Harvard Business School Press.

McKinsey & Company. (2008). Creating organizational transformations: McKinsey global survey results . McKinsey Quarterly. Retrieved August 5, 2020, from http://gsme.sharif.edu/~change/McKinsey%20Global%20Survey%20Results.pdf

Mento, A. J., Jones, R. M., & Dirndorfer, W. (2002). A change management process: Grounded in both theory and practice. Journal of Change Management, 3 (1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/714042520

Nadler, D. A., & Tushman, M. L. (1997). Competing by design: The power of organizational architecture . Oxford University Press.

Neri, R. A., Mason, C. E., & Demko, L. A. (2008). Application of Six Sigma/CAP methodology: Controlling blood-product utilization and costs. Journal of Healthcare Management, 53 (3), 183–196.

Neves, P. (2009). Readiness for change: Contributions for employee’s level of individual change and turnover intentions. Journal of Change Management, 9 (2), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010902879178

Pettigrew, A. M. (1987). Theoretical, methodological, and empirical issues in studying change: A response to Starkey. Journal of Management Studies, 24 , 420–426.

Pettigrew, A., & Whipp, R. (1991). Managing change for competitive success . Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Phillips, J. B. (2021). Change happens: Practitioner use of change management strategies (Publication No. 28769879) [Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Pless, N., & Maak, T. (2004). Building an inclusive diversity culture: Principles, processes and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 54 (2), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-004-9465-8

Polk, J. D. (2011). Lean Six Sigma, innovation, and the Change Acceleration Process can work together. Physician Executive, 37 (1), 38̫–42.

Pollack, J., & Pollack, R. (2015). Using Kotter’s eight stage process to manage an organizational change program: Presentation and practice. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 28 , 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-014-9317-0

Raineri, A. B. (2011). Change management practices: Impact on perceived change results. Journal of Business Research, 64 (3), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.11.011

Saka, A. (2003). Internal change agents’ view of the management of change problem. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16 (5), 480–496. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810310494892

Strebel, P. (1996). Why do employees resist change? Harvard Business Review, 74 (3), 86–92.

Waterman, R. H., Jr, Peters, T. J., & Phillips, J. R. (1980). Structure is not organization. Business Horizons, 23 (3), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(80)90027-0

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University Libraries, Florida State University, 116 Honors Way, Tallahassee, FL, 32306, USA

Jeffrey Phillips

Department of Educational Psychology & Learning Systems, College of Education, Florida State University, Stone Building-3205F, Tallahassee, FL, 32306-4453, USA

James D. Klein

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jeffrey Phillips .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests.

This research does not represent conflicting interests or competing interests. The research was not funded by an outside agency and does not represent the interests of an outside party.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Phillips, J., Klein, J.D. Change Management: From Theory to Practice. TechTrends 67 , 189–197 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-022-00775-0

Download citation

Accepted : 02 September 2022

Published : 09 September 2022

Issue Date : January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-022-00775-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Change management

- Organizational development

- Performance improvement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Harvard ManageMentor: Change Management

By: Harvard Business Publishing

In this course, students will learn that by having a clear vision and a sound plan, they can learn to manage change - instead of change managing them. They will come away with an eight-stage change…

- Length: 2 hours, 38 minutes

- Publication Date: Aug 27, 2019

- Discipline: Organizational Behavior

- Product #: 7100-HTM-ENG

What's included:

- Facilitator Guide

- Supplements

$10.00 per student

degree granting course

$25.00 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

Harvard ManageMentor helps students develop the skills they need to thrive in the workforce. These online courses combine the latest in business thinking from management experts with interactive assignments to empower students with the skills employers seek.

In this course, students will learn that by having a clear vision and a sound plan, they can learn to manage change - instead of change managing them. They will come away with an eight-stage change process that can dramatically improve the chances of change leading to success. They will have the opportunity to learn strategies and best practices from business leaders, authors, and coaches like Scott Anthony, Amy Edmondson, Thomas-Wedell-Wedellsborg, and Susan David.

Students have the option to view the content in English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Chinese. This online course has been designed and developed with the intention of complying with WCAG 2.0 AA standards. Explore all Harvard ManageMentor courses at https://hbsp.harvard.edu/harvard-manage-mentor/

Learning Objectives

Maintain a high level of change readiness

Initiate and lead a change effort

Implement change efforts

Overcome resistance to change in an organization

Aug 27, 2019 (Revised: Apr 28, 2020)

Discipline:

Organizational Behavior

Harvard Business Publishing

7100-HTM-ENG

2 hours, 38 minutes

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Change management.

Jennifer M. Barrow ; Pavan Annamaraju ; Tammy J. Toney-Butler .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 18, 2022 .

- Definition/Introduction

Change is inevitable in health care. A significant problem specific to health care is that almost two-thirds of all change projects fail for many reasons, such as poor planning, unmotivated staff, deficient communication, or excessively frequent changes [1] . All healthcare providers, at the bedside to the boardroom, have a role in ensuring effective change. Using best practices derived from change theories can help improve the odds of success and subsequent practice improvement.

Suppose a health care provider works in a hospital department that has experienced a 3-month increase in unwitnessed patient falls during the hours surrounding shift change. Evidence-based changes in the current shift change process would likely decrease patient falls; however, departmental leadership has attempted unsuccessfully to fix this problem twice in the past 3 months. Staff continues to revert to previous shift change protocols to save time, which leaves patients unmonitored for extended periods. What can departmental leadership and staff do differently to create sustained, positive change to serve the department’s patients and employees?

The answer may lie within the work of several change leaders and theorists. Although theories may seem abstract and impractical for direct healthcare practice, they can be quite helpful for solving common healthcare problems. Lewin was an early change scholar who proposed a three-step process for ensuring successful change [2] . Other theorists like Lippitt, Kotter, and Rogers have added to the collective change knowledge to expand upon Lewin’s original Planned Change Theory. Although each change theory is different with unique strengths and weaknesses, the theories’ commonalities can provide best practices for sustaining positive change.

Lewin’s Theory of Planned Change includes the following change stages [2] :

- Unfreezing (understanding change is needed)

- Moving (the process of initiating change)

- Refreezing (establishing a new status quo).

Lippitt, building on Lewin’s original theory, created the Phases of Change Theory that encompass the following change phases [3] :

- Becoming more aware of the need for change

- Develop a relationship between the system and change agent

- Define a change problem

- Set change goals and action plan for achievement

- Implement the change

- Staff accept the change; stabilization

- Redefine the relationship of the change agent with the system.

Kotter’s Eight-Step Change Model, created in 1995, include the following change management steps [3] :

- Create a sense of urgency for change

- Form a guiding change team

- Create a vision and plan for change

- Communicate the change vision and plan with stakeholders

- Remove change barriers

- Provide short-term wins

- Build on the change

- Make the change stick in the culture.

Finally, Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory introduced these five change phases [4] :

- Knowledge (education and communication to expose staff to the change)

- Persuasion (use of change champions to pique staff interest; peers persuading peers)

- Decision (staff decide whether to accept or reject the change)

- Implementation (putting new processes into practice)

- Confirmation (staff recognize the value and benefits of the change and continue to use changed processes).

- Issues of Concern

All change initiatives, no matter how big or small, unfold in three major stages: pre-change, change, and post-change. Within those stages, healthcare providers working as change agents or change champions should select actions that match change theories. One of the most critical aspects of pre-change planning is involving key stakeholders in problem identification, goal setting, and action planning [5] . Involving stakeholders in change planning increases staff buy-in. These stakeholders should include staff from all shifts, including nights and weekends, to create peer change champions for all shifts [5] .

One particular portion of Rogers’ change theory identifies the various rates with which staff members accept changes through the process of innovation diffusion. During pre-change planning, change agents should assess their departmental staff to determine which staff belong to each category. Rogers described the different categories of staff as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards [4] . He further qualified those change acceptance categories with the following descriptions:

- Innovator: passionate about change and technology; frequently suggest new ideas for departmental change

- Early adopter: high levels of opinion leadership in the department; well-respected by peers

- Early majority: Prefer the status quo; willing to follow early adopters when notified of upcoming changes

- Late majority: Skeptical of change but will eventually accept the change once the majority has accepted; susceptible to increased departmental social pressure

- Laggard: High levels of skepticism; openly resist change [4] .

Most departmental staff will likely belong to the early or late majority. Change agents should focus their initial education efforts on Innovator and Early Adopter staff. Early adopters are often the most pivotal change champions that persuade early and late majority staff to embrace change efforts [4] .

One final critical assessment change leaders should incorporate a force field analysis, which is a significant component of Lewin’s early change theory. A force field analysis involves a review of change facilitators and barriers at work in the department. Change leaders should work to reduce change barriers through open communication and education while also aiming to strengthen change facilitators through staff recognition and various incentives.