- Open access

- Published: 28 March 2024

Medical student wellbeing during COVID-19: a qualitative study of challenges, coping strategies, and sources of support

- Helen M West ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8712-5890 1 ,

- Luke Flain ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7296-6304 2 ,

- Rowan M Davies 3 , 4 ,

- Benjamin Shelley 3 , 5 &

- Oscar T Edginton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5298-9402 3 , 6

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 179 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

25 Accesses

Metrics details

Medical students face challenges to their mental wellbeing and have a high prevalence of mental health problems. During training, they are expected to develop strategies for dealing with stress. This study investigated factors medical students perceived as draining and replenishing during COVID-19, using the ‘coping reservoir’ model of wellbeing.

In synchronous interactive pre-recorded webinars, 78 fourth-year medical students in the UK responded to reflective prompts. Participants wrote open-text comments on a Padlet site. Responses were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Analysis identified five themes. COVID-19 exacerbated academic pressures, while reducing the strategies available to cope with stress. Relational connections with family and friends were affected by the pandemic, leading to isolation and reliance on housemates for informal support. Relationships with patients were adversely affected by masks and telephone consultations, however attending placement was protective for some students’ wellbeing. Experiences of formal support were generally positive, but some students experienced attitudinal and practical barriers.

Conclusions

This study used a novel methodology to elicit medical students’ reflections on their mental wellbeing during COVID-19. Our findings reinforce and extend the ‘coping reservoir’ model, increasing our understanding of factors that contribute to resilience or burnout. Many stressors that medical students typically face were exacerbated during COVID-19, and their access to coping strategies and support were restricted. The changes to relationships with family, friends, patients, and staff resulted in reduced support and isolation. Recognising the importance of relational connections upon medical students’ mental wellbeing can inform future support.

Peer Review reports

Medical students are known to experience high levels of stress, anxiety, depression and burnout due to the nature, intensity and length of their course [ 1 ]. Medical students are apprehensive about seeking support for their mental wellbeing due to perceived stigma and concerns about facing fitness to practice proceedings [ 2 ], increasing their vulnerability to poor mental health.

Research has identified that the stressors medical students experience include a demanding workload, maintaining work–life balance, relationships, personal life events, pressure to succeed, finances, administrative issues, career uncertainty, pressure around assessments, ethical concerns, and exposure to patient death [ 3 , 4 ]. In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional stressors into medical students’ lives. These included sudden alterations to clinical placements, the delivery of online teaching, uncertainty around exams and progression, ambiguity regarding adequate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), fear of infection, and increased exposure to death and dying [ 5 , 6 ]. Systematic reviews have reported elevated levels of anxiety, depression and stress among medical students during COVID-19 [ 7 ] and that the prevalence of depression and anxiety during COVID-19 was higher among medical students than in the general population or healthcare workers [ 8 ].

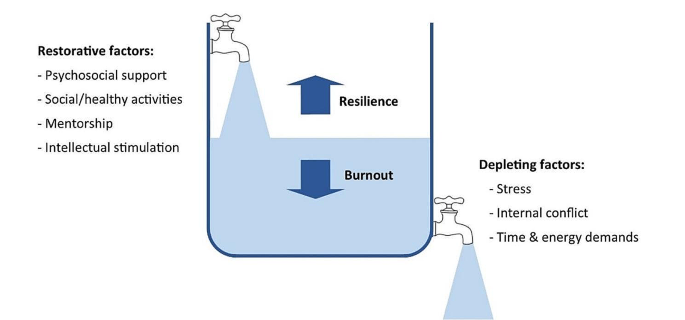

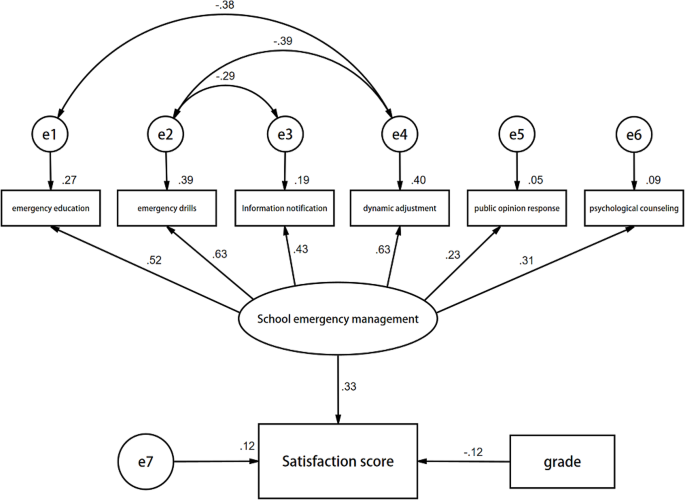

While training, medical students are expected to develop awareness of personal mental wellbeing and learn healthy coping strategies for dealing with stress [ 9 ]. Developing adaptive methods of self-care and stress reduction is beneficial both while studying medicine, and in a doctor’s future career. Protecting and promoting psychological wellbeing has the potential to improve medical students’ academic attainment, as well as their physical and mental wellbeing [ 10 ], and it is therefore important for medical educators to consider how mental wellbeing is fostered. Feeling emotionally supported while at medical school reduces the risk of psychological distress and burnout, and is related to whether students contemplate dropping out of medical training [ 11 ]. In their systematic narrative review of support systems for medical students during COVID-19, Ardekani et al. [ 12 ] propose a framework incorporating four levels: policies that promote a supportive culture and environment, active support for students at higher risk of mental health problems, screening for support needs, and provision for students wishing to access support. This emphasis on preventative strategies aligns with discussions of trauma-informed approaches to medical education, which aim to support student learning and prevent harm to mental wellbeing [ 13 ]. Dunn et al. [ 14 ] proposed a ‘coping reservoir’ model to conceptualise the factors that deplete and restore medical students’ mental wellbeing (Fig. 1 ). This reservoir is drained and filled repeatedly, as a student faces demands for their time, energy, and cognitive and emotional resources. This dynamic process leads to positive or negative outcomes such as resilience or burnout.

Coping reservoir model– adapted from Dunn et al. [ 14 ], with permission from the authors and Springer Nature

At present we have limited evidence to indicate why medical students’ mental wellbeing was so profoundly affected by COVID-19 and whether students developed coping strategies that enhanced their resilience, as suggested by Kelly et al. [ 15 ]. This study therefore sought to conceptualise the challenges medical students experienced during COVID-19, the coping strategies they developed in response to these stressors, and the supportive measures they valued. The ‘coping reservoir’ model [ 14 ] was chosen as the conceptual framework for this study because it includes both restorative and depleting influences. Understanding the factors that mediate medical students’ mental wellbeing will enable the development of interventions and support that are effective during crises such as the pandemic and more generally.

Methodology

This research study is based on a critical realist paradigm, recognising that our experience of reality is socially located [ 16 ]. Participant responses were understood to represent a shared understanding of that reality, acknowledging the social constructivist position that subjective meanings are formed through social norms and interactions with others, including while participating in this study. It also draws on hermeneutic phenomenology in aiming to interpret everyday experienced meanings for medical students during COVID-19 [ 17 ]. The use of an e-learning environment demonstrates an application of connectivism [ 18 ], a learning theory in which students participate in technological enabled networks. We recognise that meaning is co-constructed by the webinar content, prompts, ‘coping reservoir’ framework and through the process of analysis.

The multidisciplinary research team included a psychologist working in medical education, two medical students, and two Foundation level doctors. The team’s direct experience of the phenomenon studied was an important resource throughout the research process, and the researchers regularly reflected on how their subjective experiences and beliefs informed their interpretation of the data. Reflexive thematic analysis was chosen because it provides access to a socially contextualised reality, encompasses both deductive and inductive orientations so that analysis could be informed by the ‘coping reservoir’ while also generating unanticipated insights, and enables actionable outcomes to be produced [ 19 ].

Ethical approval

Approval was granted by the University of Liverpool Institute of Population Health Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 8365).

Participants

Fourth-year medical students at the University of Liverpool were invited to participate in the study during an online webinar in their Palliative Medicine placement. During six webinars between November 2020 and June 2021, 78 out of 113 eligible students participated, giving a response rate of 69%. This was a convenience sample of medical students who had a timetabled session on mental wellbeing. At the time, these medical students were attending clinical placements, however COVID-19 measures in the United Kingdom meant that academic teaching and support was conducted online, travel was limited, and contact with family and friends was restricted.

Students were informed about the study prior to the synchronous interactive pre-recorded webinar and had an opportunity to ask questions. Those who consented to participate accessed a Padlet ( www.padlet.com ) site during the webinar that provided teaching on mental wellbeing, self-care and resilience in the context of palliative medicine. Padlet is a collaborative online platform that hosts customisable virtual bulletin boards. During this recording, participants were asked to write anonymous open-text responses to reflective prompts developed from reviewing the literature (Appendix 1 ), and post these on Padlet. The Padlet board contained an Introduction to the webinar, sections for each prompt, links to references, and signposting to relevant support services. Data files were downloaded to Excel and stored securely, in line with the University of Liverpool Research Data Management Policy.

The research team used the six steps of reflexive thematic analysis to analyse the dataset. This process is described in Table 1 , and the four criteria for trustworthiness in qualitative research proposed by Lincoln and Guba [ 20 ] are outlined in Table 2 . We have used the purposeful approach to reporting thematic analysis recommended by Nowell et al. [ 21 ] and SRQR reporting standards [ 22 ] (Appendix 2 ).

Five themes were identified from the analysis:

COVID-19 exacerbated academic pressures.

COVID-19 affected students’ lifestyles and reduced their ability to cope with stress.

COVID-19 changed relationships with family and friends, which affected mental wellbeing.

COVID-19 changed interactions with patients, with positive and negative effects.

Formal support was valued but seeking it was perceived as more difficult during COVID-19.

COVID-19 exacerbated academic pressures

‘Every day feels the same, it’s hard to find motivation to do anything.’

Many participants reported feeling under chronic academic pressure due to studying medicine. Specific stressors reported were exams, revision, deadlines, workload, specific course requirements, timetables, online learning, placement, and communication from University. Some participants also reported negative effects on their mental wellbeing from feelings of comparison and competition, feeling unproductive, and overthinking.

Massive amounts of work load that feels unachievable.

COVID-19 exacerbated these academic stresses, with online learning and monotony identified as particularly draining. However, other students found online learning beneficial, due to reduced travelling.

I miss being able to see people face to face and zoom is becoming exhausting. My mental wellbeing hasn’t been great recently and I think the effects of the pandemic are slowly beginning to affect me.

I also prefer zoom as it is less tiring than travelling to campus/placement.

Clinical placements provided routine and social interaction. However, with few social interactions outside placement, this became monotonous. A reduction in other commitments helped some students to focus on their academic requirements.

Most social activity only taking place on placement has made every day feel the same.

Some students placed high value on continuing to be productive and achieve academically despite the disruption of a pandemic, potentially to the detriment of their mental wellbeing. Time that felt unproductive was frustrating and draining.

Having a productive day i.e. going for a run and a good amount of work completed in the day.

Unproductive days of revision or on placement.

COVID-19 affected students’ lifestyles and reduced their ability to cope with stress

‘Everyone’s mental well-being decreased as things they used for mental health were no longer available’.

Students often found it difficult to sustain motivation for academic work without the respite of their usual restorative activities challenging.

Not being able to balance work and social life to the same extent makes you resent work and placement more.

The competing demands medical students encounter for their time and energy were repeatedly reported by participants.

Sometimes having to go to placement + travel + study + look after myself is really tough to juggle!

However, removing some of the boundaries around academic contact and structure of extracurricular activities heightened the impact of stressors. Many participants focused on organising and managing their time to cope with this. Students were aware that setting time aside for relaxation, enjoyment, creativity, and entertainment would be beneficial for their wellbeing.

Taking time off on the weekends to watch movies.

However, they found it difficult to prioritise these without feeling guilty or believing they needed to ‘earn’ them, and academic commitments were prioritised over mental wellbeing.

Try to stop feeling guilty for doing something that isn’t medicine. Would like to say I’d do more to increase my mental wellbeing but finals are approaching and that will probably have to take priority for the next few months.

Medical students were generally aware that multiple factors such as physical activity, time with loved ones, spiritual care, nourishment and hobbies had a positive impact on their mental wellbeing. During COVID-19, many of the coping strategies that students had previously found helpful were unavailable.

Initially it improved my mental well-being as I found time to care for myself, but with time I think everyone’s mental well-being decreased as things they used for mental health were no longer available e.g. gym, counselling, seeing friends.

Participants adapted to use coping strategies that remained available during the pandemic. These included walks and time spent outdoors, exercise, journaling, reflection, nutrition, and sleep.

'Running’. ‘Yoga’. ‘Fresh air and walks'.

A few students also reported that they tried to avoid unhelpful coping strategies, such as social media and alcohol.

Not reading the news, not using social media.

Avoiding alcohol as it leads to poor sleep and time wasted.

Many participants commented on increased loneliness, anxiety, low mood, frustration, and somatic symptoms.

Everyone is worn out and demotivated. Feel that as I am feeling low I don’t want to bring others down. ‘Feel a lot more anxious than is normal and also easily annoyed and irritable.’

However, not all students reported that COVID-19 had a negative effect on wellbeing. A small minority responded that their wellbeing had improved in some way.

I think covid-19 has actually helped me become more self reliant in terms of well-being.

COVID-19 changed relationships with family and friends, which affected mental wellbeing

‘Family are a huge support for me and I miss seeing them and the lack of human contact.’

Feeling emotionally supported by family and friends was important for medical students to maintain good mental wellbeing. However, COVID-19 predominantly had a negative impact on these relationships. Restrictions, such as being unable to socialise or travel during lockdowns, led to isolation and poor mental wellbeing.

Not being able to see friends or travel back home to see friends/family there.

Participants frequently reported that spending too much time with people, feeling socially isolated, being unable to see people, or having negative social experiences had an adverse effect on their mental wellbeing. Relationships with housemates were a key source of support for some students. However, the increased intensity in housemate relationships caused tension in some cases, which had a particularly negative effect.

Much more difficult to have relationships with peers and began feeling very isolated. Talk about some of the experiences I’ve had on placement with my housemates. Added strain on my housemates to be the only ones to support me.

Knowing that their peers were experiencing similar stressors helped to normalise common difficulties. The awareness that personal contacts were also struggling sometimes curtailed seeking informal support to avoid being a burden.

Actually discussing difficulties with friends has been most helpful, as it can sometimes feel like you’re the only one struggling, when actually most people are finding this year really difficult. Family and friends, but also don’t want to burden them as I know I can feel overwhelmed if people are always coming to me for negative conversations.

COVID-19 changed interactions with patients, with positive and negative effects

‘With patients there has been limited contact and I miss speaking to patients.’

Some students reported positive effects on relationships with patients, and feeling a sense of purpose in talking to patients when their families were not allowed to visit. Medical students felt a moral responsibility to protect patients and other vulnerable people from infection, which contributed to a reduction in socialising even when not constrained by lockdown.

Talking to patients who can’t get visitors has actually made me feel more useful. Anxiety over giving COVID-19 to patients or elderly relatives.

Students occasionally reported that wearing PPE made interactions with patients more challenging. Students’ contact with patients changed on some placements due to COVID-19, for example replacing in-person appointments with telephone consultations, and they found this challenging and disappointing.

Masks are an impediment to meaningful connections with new people. GP block when I saw no patients due to it all being on the telephone.

Formal support was valued but seeking it was perceived as more difficult during COVID-19

‘Feel a burden on academic and clinical staff/in the way/annoying so tend to just keep to myself.’

Many participants emphasised the primary importance of support from family and friends, and their responses indicated that most had not sought formal support. While staff remained available and created opportunities for students to seek support, factors such as online learning and increased clinical workloads meant that some students found it harder to build supportive relationships with academic and placement staff and felt disconnected from them, which was detrimental for wellbeing and engagement.

Staff have been really helpful on placement but it was clear that in some cases, staff were overwhelmed with the workload created by COVID. Even though academic staff are available having to arrange meetings over zoom rather than face to face to discuss any problem is off putting.

A few students described difficulty knowing what support was available, and identifying when they needed it.

It’s difficult to access support when you’re not sure what is available. Also you may feel your problems aren’t as serious as other people’s so hold off on seeking support.

Formal support provided within the University included meetings with Academic Advisors, the School of Medicine wellbeing team, and University counselling service and mental health advisory team. It was also available from NHS services, such as GPs and psychological therapies. Those who had accessed formal support mostly described positive experiences with services. However, barriers to seeking formal support, such as perceived stigma, practicalities, waiting times for certain services, and concern that it may impact their future career were reported by some participants.

It is good that some services offer appointments that are after 5pm- this makes it more accessible to healthcare students. Had good experience with GPs about mental health personally. Admitting you need help or asking for help would make you look weak. Reassurance should be provided to medical students that accessing the wellbeing team is not detrimental to their degree. If anything it should be marketed as a professional and responsible thing to do.

Some students preferred the convenience of remote access, others found phone or video impersonal and preferred in-person contact.

Students expressed that it was helpful when wellbeing support was integrated with academic systems, for example Academic Advisors or placement supervisors.

My CCT [primary-care led small group teaching] makes sure to ask how we are getting on and how our placements are going, so I think small groups of people with more contact with someone are more useful then large groups over zoom. Someone to speak to on palliative care placement, individual time with supervisor to check how we are doing (wellbeing, mental health) - would be a nice quick checkup.

Participants typically felt able to share openly in an anonymous forum. Reading peers’ comments helped them to see that other students were having similar experiences and challenged unhealthy comparisons.

I definitely shared more than I would have done on a zoom call. I loved this session as it makes you feel like you’re not alone. Reassuring to know that there are others going through similar things as you.

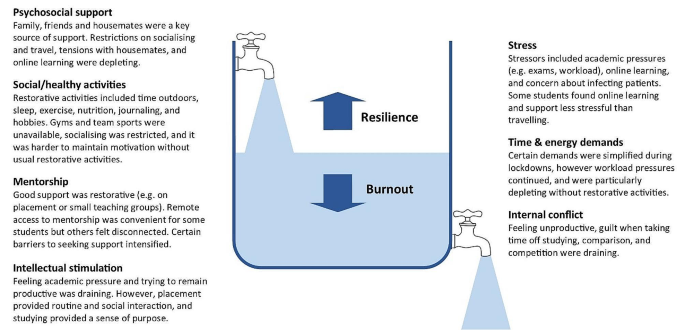

Our findings demonstrate that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the stressors medical students experience, and removed some rewarding elements of learning, while reducing access to pre-existing coping strategies. The results support many aspects of the ‘coping reservoir’ framework [ 14 ]. Findings corroborate the restorative effects of psychosocial support and social/healthy activities such as sleep and physical activity, and the depletion of wellbeing due to time and energy demands, stress, and disruptions relating to the pandemic such as online teaching and limited social interaction. Feeling a sense of purpose, from continuing studying or interactions with patients for example, was restorative for wellbeing. Mentorship and intellectual stimulation were present in the responses, but received less attention than psychosocial support and social/healthy activities. Internal conflict is primarily characterised by Dunn et al. [ 14 ] as ambivalence about pursuing a career in medicine, which was not expressed by participants during the study. However, participants identified that their wellbeing was reduced by feeling unproductive and lacking purpose, feeling guilty about taking time for self-care, competing priorities, and comparison with peers, all of which could be described as forms of internal conflict. Different restorative and draining factors appeared to not be equally weighted by the participants responding to the prompts: some appear to be valued more highly, or rely on other needs being met. Possible explanations are that students may be less likely to find intellectual stimulation and mentorship beneficial if they are experiencing reduced social support or having difficulty sleeping, and internal conflict about pursuing a career in medicine might be overshadowed by more immediate concerns, for example about the pandemic. This prioritisation resembles the relationship between physiological and psychological needs being met and academic success [ 23 ], based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [ 24 ]. A revised ‘coping reservoir’ model is shown in Fig. 2 .

Coping reservoir model - the effects of COVID-19 on restorative and depleting factors for medical students, adapted from Dunn et al. [ 14 ], with permission from the authors and Springer Nature

Relational connections with family, friends, patients, and staff were protective factors for mental wellbeing. Feeling emotionally supported by family and friends is considered especially important for medical students to maintain good mental wellbeing [ 11 ]. These relationships usually mitigate the challenges of medical education [ 25 ], however they were fundamentally affected by the pandemic. Restrictions affecting support from family and friends, and changes to contact with patients on placement, had a negative effect on many participants’ mental wellbeing. Wellbeing support changed during the pandemic, with in-person support temporarily replaced by online consultations due to Government guidelines. Barriers to seeking formal support, such as perceived stigma, practicalities, and concern that it may impact their future career were reported by participants, reflecting previous research [ 26 ]. Despite initiatives to increase and publicise formal support, some students perceived that this was less available and accessible during COVID-19, due to online learning and awareness of the increased workload of clinicians, as described by Rich et al. [ 27 ]. These findings provide further support for the job demand-resources theory [ 28 , 29 ] where key relationships and support provide a protective buffer against the negative effects of challenging work.

In line with previous research, many participants reported feeling under chronic academic pressure while studying medicine [ 3 ]. Our findings indicate that medical students often continued to focus on achievement, productivity and competitiveness, despite the additional pressures of the pandemic. Remaining productive in their studies might have protected some students’ mental wellbeing by providing structure and purpose, however students’ responses primarily reflected the adverse effect this mindset had upon their wellbeing. Some students felt guilty taking time away from studying to relax, which contributes to burnout [ 30 ] , and explicitly prioritised academic achievement over their mental wellbeing.

Students were aware of the factors that have a positive impact on their mental wellbeing, such as physical activity, time with loved ones, spiritual care, nourishment and hobbies [ 31 ]. However, COVID-19 restrictions affected many replenishing factors, such as socialising, team sports, and gyms, and intensified draining factors, such as academic stressors. Students found ways to adapt to the removal of most coping strategies, for example doing home workouts instead of going to the gym, showing how they developed coping strategies that enhanced their resilience [ 15 ]. However, they found it more difficult to mitigate the effect of restrictions on relational connections with peers, patients and staff, and this appears to have had a particularly negative impact on mental wellbeing. While clinical placements provided helpful routine, social interaction and a sense of purpose, some students reported that having few social interactions outside placement became monotonous.

Our findings show that medical students often felt disconnected from peers and academic staff, and reported loneliness, isolation and decreased wellbeing during COVID-19. This corresponds with evidence that many medical students felt isolated [ 32 ], and students in general were at higher risk of loneliness than the general population during COVID-19 lockdowns [ 33 ]. Just as ‘belongingness’ mediates subjective wellbeing among University students [ 34 ], feeling connected and supported acts as a protective buffer for medical students’ psychological wellbeing [ 25 ].

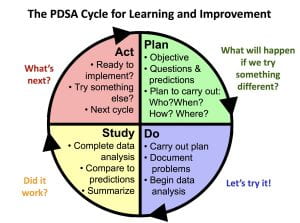

Translation into practice

Based on the themes identified in this study, specific interventions can be recommended to support medical students’ mental wellbeing, summarised in Table 3 . This study provides evidence to support the development of interventions that increase relational connections between medical students, as a method of promoting mental wellbeing and preventing burnout. Our findings highlight the importance of interpersonal relationships and informal support mechanisms, and indicate that medical student wellbeing could be improved by strengthening these. Possible ways to do this include encouraging collaboration over competition, providing sufficient time off to visit family, having a peer mentor network, events that encourage students to meet each other, and wellbeing sessions that combine socialising with learning relaxation and mindfulness techniques. Students could be supported in their interactions with patients and peers by embedding reflective practice such as placement debrief sessions, Schwartz rounds [ 35 ] or Balint groups [ 36 ], and simulated communication workshops for difficult situations.

Experiencing guilt [ 30 ] and competition [ 4 ] while studying medicine are consistently recognised as contributing to distress and burnout, so interventions targeting these could improve mental wellbeing. Based on the responses from students, curriculum-based measures to protect mental wellbeing include manageable workloads, supportive learning environments, cultivating students’ sense of purpose, and encouraging taking breaks from studying without guilt. Normalising sharing of difficulties and regularly including content within the curriculum on self-care and stress reduction would improve mental wellbeing.

In aiming to reduce psychological distress among medical students, it is important that promotion of individual self-care is accompanied by reducing institutional stressors [ 11 , 29 ]. While the exploration of individual factors is important, such as promoting healthy lifestyle habits, reflection, time management, and mindset changes, this should not detract from addressing factors within the culture, learning and work environment that diminish mental wellbeing [ 37 ]. Heath et al. [ 38 ] propose a pro-active, multi-faceted approach, incorporating preventative strategies, organisational justice, individual strategies and organisational strategies to support resilience in healthcare workers. Similarly, trauma-informed medical education practices [ 13 ] involve individual and institutional strategies to promote student wellbeing.

Students favoured formal support that was responsive, individualised, and accessible. For example, integrating conversations about wellbeing into routine academic systems, and accommodating in-person and remote access to support. There has been increased awareness of the wellbeing needs of medical students in recent years, especially since the start of the pandemic, which has led to improvements in many of these areas, as reported in reviews by Ardekani et al. [ 12 ] and Klein and McCarthy [ 39 ]. Continuing to address stigma around mental health difficulties and embedding discussions around wellbeing in the curriculum are crucial for medical students to be able to seek appropriate support.

Strengths & limitations

By using qualitative open-text responses, rather than enforcing preconceived categories, this study captured students’ lived experience and priorities [ 4 , 31 ]. This increased the salience and depth of responses and generated categories of responses beyond the existing evidence, which is particularly important given the unprecedented experiences of COVID-19. Several strategies were used to establish rigour and trustworthiness, based on the four criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba [ 20 ] (Table 2 ). These included the active involvement of medical students and recent medical graduates in data analysis and the development of themes, increasing the credibility of the research findings.

Potential limitations of the study are that participants may have been primed to think about certain aspects of wellbeing due to data being collected during a webinar delivered by medical educators including the lead author at the start of their palliative medicine placement, and the choice of prompts. Data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore represents fourth year medical students’ views in specific and unusual circumstances. Information on this context is provided to enable the reader to evaluate whether the findings have transferability to their setting. Responses were visible to others in the group, so participants may have influenced each other to give socially acceptable responses. This process of forming subjective meanings through social interactions is recognised as part of the construction of a shared understanding of reality, and we therefore view it as an inherent feature of this methodology rather than a hindrance. Feedback on the webinar indicated that students benefitted from this process of collective meaning-making. Similarly, researcher subjectivity is viewed as a contextual resource for knowledge generation in reflexive thematic analysis, rather than a limitation to be managed [ 19 ]. The study design meant that different demographic groups could not be compared.

Padlet provided a novel and acceptable method of data collection, offering researchers and educators the potential benefits of an anonymous forum in which students can see their peers’ responses. The use of an interactive webinar demonstrated a potential application of connectivist pedagogical principles [ 18 ]. Researchers are increasingly using content from online forums for qualitative research [ 40 ], and Padlet has been extensively used as an educational tool. However, to the authors’ knowledge, Padlet has not previously been used as a data collection platform for qualitative research. Allowing anonymity carried the risk of students posting comments that were inappropriate or unprofessional. However, with appropriate guidance it appeared to engender honesty and reflection, provided a safe and collaborative learning environment, and student feedback was overwhelmingly positive. It would be useful to evaluate the effects of this reflective webinar on medical students’ mental wellbeing, given that it acted as an intervention in addition to a teaching session and research study.

Students were prompted to plan what they would do following the webinar to improve their mental wellbeing. A longitudinal study to determine how students enacted these plans would allow a more detailed investigation of students’ self-care behaviour.

While we hope that the stressors of COVID-19 will not be repeated, this study provides valuable insight into medical students’ mental wellbeing, which can inform support beyond this exceptional time. The lasting impact of the pandemic upon medical education and mental wellbeing remains to be seen. Nevertheless, our findings reinforce and extend the coping reservoir model proposed by Dunn et al. [ 14 ], adding to our understanding of the factors that contribute to resilience or burnout. In particular, it provides evidence for the development of interventions that increase experiences of relational connectedness and belonging, which are likely to act as a buffer against emotional distress among medical students.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Awad F, Awad M, Mattick K, Dieppe P. Mental health in medical students: time to act. Clin Teach. 2019;16(4):312–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(12):1613–22.

Hill MR, Goicochea S, Merlo LJ. In their own words: stressors facing medical students in the millennial generation. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1530558.

Papapanou M, Routsi E, Tsamakis K, Fotis L, Marinos G, Lidoriki I, et al. Medical education challenges and innovations during COVID-19 pandemic. Postgrad Med J. 2021;0:1–7.

Google Scholar

De Andres Crespo M, Claireaux H, Handa AI. Medical students and COVID-19: lessons learnt from the 2020 pandemic. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1146):209–10.

Paz DC, Bains MS, Zueger ML, Bandi VR, Kuo VY, Cook K et al. COVID-19 and mental health: a systematic review of international medical student surveys. Front Psychol. 2022;(November):1–13.

Jia Q, Qu Y, Sun H, Huo H, Yin H, You D. Mental health among medical students during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13:846789.

General Medical Council. Outcomes for Graduates. London; 2020 https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/standards-and-outcomes/outcomes-for-graduates [accessed 13 Feb 2024].

Shiralkar MT, Harris TB, Eddins-Folensbee FF, Coverdale JH. A systematic review of stress-management programs for medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):158–64.

McLuckie A, Matheson KM, Landers AL, Landine J, Novick J, Barrett T, et al. The relationship between psychological distress and perception of emotional support in medical students and residents and implications for educational institutions. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(1):41–7.

Ardekani A, Hosseini SA, Tabari P, Rahimian Z, Feili A, Amini M. Student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:352.

Brown T, Berman S, McDaniel K, Radford C, Mehta P, Potter J, et al. Trauma-informed medical education (TIME): advancing curricular content and educational context. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):661–7.

Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier C. Promoting resilience and preventing burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):44–53.

Kelly EL, Casola AR, Smith K, Kelly S, Syl M, Cruz D, De. A qualitative analysis of third-year medical students ’ reflection essays regarding the impact of COVID-19 on their education. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(481).

Pilgrim D. Some implications of critical realism for mental health research. Soc Theory Heal. 2014;12:1–21.

Article Google Scholar

Henriksson C, Friesen N. Introduction. In: Friesen N, Henriksson C, Saevi T, editors. Hermeneutic phenomenology in education. Sense; 2012. pp. 1–17.

Goldie JGS, Connectivism. A knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Med Teach. 2016;38(10):1064–9.

Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2021.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, California: SAGE; 1985.

Book Google Scholar

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving tomeet thetrustworthiness criteria. 2017;16:1–13.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51.

PubMed Google Scholar

Freitas FA, Leonard LJ. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and student academic success. Teach Learn Nurs. 2011;6(1):9–13.

Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. 3rd ed. New York: Longman; 1954.

MacArthur KR, Sikorski J. A qualitative analysis of the coping reservoir model of pre-clinical medical student well-being: human connection as making it worth it. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Simpson V, Halpin L, Chalmers K, Joynes V. Exploring well-being: medical students and staff. Clin Teach. 2019;16(4):356–61.

Rich A, Viney R, Silkens M, Griffin A, Medisauskaite A. UK medical students ’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e070528.

Bakker AAB, Demerouti E. Job demands-resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22(3):273–85.

Riley R, Kokab F, Buszewicz M, Gopfert A, Van Hove M, Taylor AK et al. Protective factors and sources of support in the workplace as experienced by UK foundation and junior doctors: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6).

Greenmyer JR, Montgomery M, Hosford C, Burd M, Miller V, Storandt MH, et al. Guilt and burnout in medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2021;34(1):69–77.

Ayala EE, Omorodion AM, Nmecha D, Winseman JS, Mason HRC. What do medical students do for self-care? A student-centered approach to well-being. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(3):237–46.

Wurth S, Sader J, Cerutti B, Broers B, Bajwa MN, Carballo S, et al. Medical students’ perceptions and coping strategies during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: studies, clinical implication, and professional identity. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):620.

Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health. 2020;186:31–4.

Arslan G, Loneliness C, Belongingness. Subjective vitality, and psychological adjustment during coronavirus pandemic: development of the college belongingness questionnaire. J Posit Sch Psychol. 2021;5(1):17–31.

Maben J, Taylor C, Dawson J, Leamy M, McCarthy I, Reynolds E et al. A realist informed mixed-methods evaluation of Schwartz center rounds in England. Heal Serv Deliv Res. 2018;6(37).

Monk A, Hind D, Crimlisk H. Balint groups in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. Psychoanal Psychother. 2018;8734:1–26.

Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132–49.

Heath C, Sommerfield A, Von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(10):1364–71.

Klein HJ, McCarthy SM. Student wellness trends and interventions in medical education: a narrative review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022;9(92).

Smedley RM, Coulson NS. A practical guide to analysing online support forums. Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(1):76–103.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr P Byrne for providing guidance, Mrs A Threlfall and Professor VCT Goddard-Fuller for commenting on drafts, and the medical students who participated in the webinars.

This study was unfunded.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, University of Liverpool, Eleanor Rathbone Building, Bedford Street South, Liverpool, L69 7ZA, UK

Helen M West

Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK

School of Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

Rowan M Davies, Benjamin Shelley & Oscar T Edginton

Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, UK

Rowan M Davies

Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS Foundation Trust, West Yorkshire, UK

Benjamin Shelley

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Leeds, UK

Oscar T Edginton

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HMW conceptualised the study and collected the data. HMW, LF, RMD, BS and OTE conducted data analysis. HMW, LF, RMD and OTE wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Helen M West .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

Approval was granted by the University of Liverpool Institute of Population Health Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 8365). Students were fully informed about the study prior to the workshop and had an opportunity to ask questions. Participants provided informed consent, completing an electronic consent form before responding to prompts. The study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the University of Liverpool Research Ethics and Research Data Management Policies, and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

West, H.M., Flain, L., Davies, R.M. et al. Medical student wellbeing during COVID-19: a qualitative study of challenges, coping strategies, and sources of support. BMC Psychol 12 , 179 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01618-8

Download citation

Received : 12 December 2023

Accepted : 22 February 2024

Published : 28 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01618-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Mental wellbeing

- Medical student

- Student doctor

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2022

Student wellness trends and interventions in medical education: a narrative review

- Harrison J. Klein 1 &

- Sarah M. McCarthy 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 92 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

16 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

Medical education is a time wrought with personal and professional stressors, posing serious challenges to maintaining student wellness. Extensive research has thus been conducted to identify these stressors and develop practical solutions to alleviate their harmful effects. This narrative review of quantitative and qualitative literature summarizes trends in student wellness and examines interventions deployed by medical schools to ameliorate student distress. Current trends indicate that mental illness, substance use, and burnout are more prevalent in medical students compared to the general population due to excessive academic, personal, and societal stressors. Pass/fail grading systems and longitudinal, collaborative learning approaches with peer support appear to be protective for student wellness. Additionally, maintaining enjoyable hobbies, cultivating social support networks, and developing resiliency decrease distress in medical students on an individual level. Faculty and administrator development is also a necessary component to ensuring student wellness. The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unique challenges to the medical education system and has stimulated unprecedented innovation in educational technology and adaptability. Particularly, the discontinuation of the clinical skill evaluation components for both osteopathic and allopathic students should be a focus of medical student wellness research in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on pediatric subspecialists’ well-being and perception of workplace value

Jeanie L. Gribben, Samuel M. Kase, … Andrea S. Weintraub

Academic burnout among master and doctoral students during the COVID-19 pandemic

Diego Andrade, Icaro J. S. Ribeiro & Orsolya Máté

Online education and the mental health of faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan

Yosuke Kita, Shoko Yasuda & Claudia Gherghel

Defining student wellness

Defining student wellness has challenged stakeholders throughout the medical education system. The term “wellness” first appeared in literature following World War II, though the concept extends back to Christian ethics of the 19th century that linked physical well-being to moral character (Kirkland, 2014 ). Implicit within these origins of wellness is a responsibility of the individual to contribute to their own well-being. This is reflected in Kirkland’s premise that “each individual can and should strive to achieve a state of optimal functioning” ( 2014 ). Contemporary researchers characterize wellness similarly to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of human health. In the preamble to the WHO’s constitution, health is defined as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease” (Grad, 2002 ). Wellness can therefore be succinctly defined as self-aware, intentional prevention of distress and promotion of well-being (Kirkland, 2014 ).

Human wellness’s inherent multidimensionality often poses a challenge to quantitative research methods. Most studies thus ultimately measure some combination of indicators for distress and well-being. Addiction, mental disorders, suicidal ideation, and burnout are common indicators of distress assessed through various screening methods (Jackson et al., 2016 ; Moir et al., 2018 ; Dyrbye and Shanafelt, 2016 ). On the contrary, Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index Composite Score examines well-being across several domains of life, including: life evaluation, emotional health, physical health, healthy behavior, work environment, and basic access. The Well-Being Composite Score thus emphasizes the presence of health rather than absence of disease (Kirkland, 2014 ). Though methodologies and definitions vary across studies and reviews, the fundamental characteristics of wellness appear constant: absence of disease and presence of health. Investigations using this paradigm have identified professional education, particularly medical education, as a time of increased distress and diminished wellness (Dyrbye et al., 2014 ). We have thus undertaken a review of contemporary literature to identify trends in student wellness, as well as the interventions deployed to address such trends. This narrative review outlines the prevalence and contributing factors to mental illness, addiction, and burnout in the medical student population. We then describe several intervention strategies used by medical schools to address student wellness deficits, including: wellness committees, pass-fail (P/F) grading, mindfulness training, curricular alterations, and developing more wellness-aware faculty/administration. In compiling this review, we hope to provide a snapshot of contemporary student wellness that may be used to guide medical schools seeking to improve the student experience during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath.

Mental well-being

As previously mentioned, directly measuring wellness is a challenge in educational research. Therefore, most studies assess wellness of student populations by examining rates of mental illness or distress (Kirkland, 2014 ). Numerous studies have revealed that mental health issues are virtually ubiquitous in the medical education system. Dyrbye and colleagues report that medical school appears to be a peak time for distress in a physician’s training ( 2014 ). Localization of distress to the training process is evidenced by higher rates of depression, fatigue, and suicidal ideation in medical students as compared to age-matched controls from the general population, with these symptoms declining to the same levels as control populations within 5 years after completing post-graduate education (Dyrbye et al., 2014 ). Further, Jackson et al determined that a majority of medical students exhibited either burnout, depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, alcohol abuse/dependence, or a combination of these factors at the time of survey ( 2016 ). A meta-analysis conducted by Rosenstein and colleagues revealed that 27% of medical students met criteria specifically for depression or depressive symptoms ( 2016 ). This increased prevalence of mental illness is not restricted to medical education. A survey of law students revealed that 17% screened positively for depression, 37% screened positively for anxiety, and 27% screened positively for an eating disorder. These statistics indicate increasing trends of mental illness across graduate education as a whole, rather than medical education alone (Organ et al., 2016 ).

This prolific mental distress can substantially impact medical students’ ability to meet academic demands (Dyrbye et al., 2014 ). As such, substantial research has been conducted investigating factors that contribute to mental illness in an academic setting. Surprisingly, students begin medical school with mental health better than similarly aged peers. However, these roles quickly reverse, with medical student mental health ultimately becoming worse than control populations (Dyrbye and Shanafelt, 2016 ). It seems that medical education may actually select for individuals prone to developing psychological distress (Bergmann et al., 2019 ). Moir et al. report that the majority of medical students are considered Type A individuals, displaying high levels of ambition and competition. Though these qualities facilitate academic success, they also lead to hostility and frustration with challenging situations (Moir et al., 2018 ). Medical students were also found to have high levels of conscientiousness (Moir et al., 2018 ). Conscientiousness is a component of the Big 5 Personality model, which uses the qualities of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness as the most basic descriptors of an individual’s personality (Shi et al., 2018 ). Conscientiousness is characterized by diligence and careful attention to detail, thus predicting high levels of academic success. However, increased conscientiousness may also exacerbate the likelihood of mental and physical distress due to inordinate demands placed on one’s self (Bergmann et al., 2019 ). Student age was also found to correlate with mental well-being. Younger students were found to approach their studies with dualistic orientations, seeking an explicit, incontrovertible knowledge of medicine. Diagnostic challenges and knowledge gaps ubiquitous in clinical medicine can thus be frustrating to younger students (Lonka et al., 2008 ). It is worth noting that, despite the importance of addressing mental health issues, some authors feel categorizing symptoms of depression and burnout leads to over-medicalization of human suffering and is not useful (Moir et al., 2018 ).

The aforementioned qualities of medical students facilitate development of both maladaptive perfectionism and imposter syndrome, heightening mental wellness concerns in this population (Bubenius and Harendza, 2019 ; Hu et al., 2019 ; Henning et al., 1998 ; Seeliger and Harendza, 2017 ; Thomas and Bigatti, 2020 ). The prevalence of imposter syndrome has been estimated between 22.5–46.6% in medical students, however, the prevalence of perfectionism has proven much more difficult to measure (Thomas and Bigatti, 2020 ). Maladaptive perfectionism is a multifactorial entity encompassing inordinate self-expectations, negative reactions to failure, and a persistent lack of satisfaction in performance (Bubenius and Harendza, 2019 ; Thomas and Bigatti, 2020 ). This emphasis on perfection prevents students from appreciating their vulnerability and thus delays self-recognition of mental distress (Seeliger and Harendza, 2017 ). Not surprisingly, maladaptive perfectionism has thus demonstrated an association with anxiety, depression, bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and chronic fatigue syndrome (Thomas and Bigatti, 2020 ). The strength of these associations was further demonstrated by Bubenius and Harendza’s use of maladaptive perfectionism as a predictor of depressive symptoms in German medical school applicants ( 2019 ). Imposter syndrome is a phenomenon often associated with maladaptive perfectionism and is characterized by anxiety, lack of self-confidence, depression, and frustration with one’s performance (Clance and Imes, 1978 ). While imposter syndrome bears an uncanny resemblance to perfectionism, the difference lies in imposter syndrome’s characteristic fear of being discovered as undeserving of a place in medical school, regardless of actual accomplishments (Clance and Imes, 1978 ). Imposter syndrome has been associated with a lack of resilience and this, similar to perfectionism, can increase psychological distress (Levant et al., 2020 ). The combined effects of imposter syndrome and maladaptive perfectionism predispose students to mental health issues and thus deserve special attention in studies geared toward well-being interventions. Of note, preliminary work by Chand and colleagues has demonstrated that cognitive behavioral therapy may be especially effective in ameliorating the deleterious effects of maladaptive perfectionism (Chand et al., 2018 ). Treatment for imposter syndrome, however, appears to be a significant gap in wellness literature (Bravata et al., 2020 ).

Deeply intertwined with imposterism and perfectionism is the medical student’s experience of shame. Shame is characterized as a negative emotional response to life events. These life events can take many forms, though personal mistakes within a hostile environment are a common instigator of shame (Bynum et al., 2019 ). Perfectionism and imposter syndrome thus provide a fertile soil of negative self-evaluation in which shame can flourish (Bynum et al., 2020 ). Feelings of shame are further exacerbated by factors within the medical school environment. Mistreatment by colleagues or preceptors, receiving low test scores, underrepresentation within classes, institutional expectations, and social comparison were reported as contributors to shame by medical students in a hermeneutic analysis (Bynum et al., 2021 ). Regardless of origin, shame has been recognized as a “destabilizing emotion,” leading to student isolation, psychological distress, and difficulty with identity formation (Bynum et al., 2021 ). Explorations of shame as a contributor to medical student distress are limited in the current literature. Thus, wellness researchers must dedicate studies to characterizing and preventing this significant, but potentially modifiable, contributor to student distress (Bynum et al., 2019 ).

Medical students’ educational environment can also have a profound impact on mental health, particularly during the early days of training. The transition between college and professional school is marked by anxiety, stress, and financial upheaval. Thus, students may feel more vulnerable than ever as they begin their professional education in a new environment in which they are unaware of available mental health resources, leading to isolation and unnecessary suffering (Organ et al., 2016 ). Even for those aware of these resources, significant stigma still surrounds mental illness in professional education. This is emphasized in Organ et al’s finding that only 50% of law students with mental health issues actually receive professional counseling. Their findings suggest that this reluctance largely stems from fear of professional repercussions if administrators discover a student’s mental health diagnosis (Organ et al., 2016 ). While this study was conducted in law students, Hankir et al found similar trends in both medical students and physicians by examining autobiographical narratives published to combat the stigma against help-seeking behavior (Hankir et al., 2014 ). Hankir and colleagues have elucidated several phenomena that contribute to medical students delaying or even avoiding treatment for mental distress. Self-stigma operates as a powerful deterrent to help-seeking and seems to stem from internalization of society’s expectation that medical students are mentally and physically invincible. This leads to feelings of decreased self-esteem and self-efficacy, as well as fear of stigmatization from the general public (Hankir et al., 2014 ; Fischbein and Bonfine, 2019 ). Rahael Gupta, now a psychiatry resident, brought this stigma to public light as she shared her personal experience with depression during medical school in her short film project entitled “Physicians Connected.” The film, conveyed line-by-line through Gupta’s colleagues at the University of Michigan, highlights the unspoken rule that mental distress is a black mark on a future physician’s career (Gupta, 2018 ). Gupta’s efforts, and those similar, underscore a growing call for public discourse, rather than concealment, of mental well-being within the medical profession. This call is echoed with Robyn Symon’s film “Do No Harm: Exposing the Hippocratic Hoax,” which further explores the toxic culture of medical education that drives physicians and medical students to commit suicide. Both Gupta and Symon highlight the taboo of mental distress within the medical field, which instead prioritizes efficiency and academic success over student and physician well-being. Both films characterize this lack of help-seeking behavior as products of the healthcare system’s toxic structure, rather than individual student distress interacting with a demanding work life (Gupta, 2018 ; Symon 2020 ).

Substance use

In addition to impaired academic performance, mental illness also increases risk for development of substance use disorder in medical students (McLellan, 2017 ). Thus, the pervasiveness of mental illness during medical education warrants careful analysis of substance use patterns in the student population. Alcohol abuse or dependence has already been well documented in the professional education system (Dyrbye and Shanafelt, 2016 ; Organ et al., 2016 ; Jackson et al., 2016 ). Alarmingly, despite 43% of law students reporting a recent occurrence of binge drinking, only 4% had sought professional assistance for alcohol or drug misuse. This trend again highlights significant mental health and addiction stigma throughout the graduate education system (Organ et al., 2016 ). Medical students, and all those in the medical field, may be uniquely affected by this prevalence of substance use. For example, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention produced a documentary entitled “Struggling in Silence: Physician Depression and Suicide,” which highlights the powerful role that substance use plays in medical student and physician suicide specifically. With a greater knowledge of and access to potentially lethal substances, those in the medical field are at heightened risk for suicide completion, especially with the inhibition-lowering effects of some drugs (AFSP, 2002 ).

Alcohol dependence is of particular concern in medical education due to implications in hindering student career progression and compromised patient safety. Despite this concern, alcohol use is prevalent among medical students. A survey of 855 medical students across 49 schools in the United States revealed that 33.8% of students reported consuming 5 or more drinks in one sitting within the past two weeks, meeting the criteria for binge drinking (Ayala et al., 2017 ). Further, survey responses from 4402 medical students in the U.S. demonstrated that 32.4% met criteria for alcohol abuse/dependence, compared to 15.6% in a control sample of similarly aged but non-medical student counterparts (Jackson et al., 2016 ). The substantial academic stress of a professional education is a clear driving force behind this trend, though several compounding risk factors have been identified. Young males were identified as at an increased risk for alcohol dependence compared to their female colleagues (Jackson et al., 2016 ; Organ et al., 2016 ). Jackson and colleagues further identified that students who were unmarried, diagnosed with a mood disorder, low-income, or burdened with educational debt from professional and undergraduate studies were at increased risk for alcohol dependence ( 2016 ). While ethnicity’s relationship to alcohol use was not explored in medical students, a survey of over 11,000 law students from 15 law schools in 2016 determined that ethnic minorities were more likely to report an increase in drinking whereas Caucasian students were more likely to demonstrate a positive CAGE screening (Organ et al., 2016 ). The CAGE screen is a 4-item questionnaire developed by John Ewing in 1984 to identify drinking problems. The CAGE screen has a 93% sensitivity and 76% specificity for identifying problem drinking whereas alcoholism identification has a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 77% (Williams, 2014 ). This increased alcohol use in both Caucasian and ethnic minority students demonstrates a need for culturally tailored and inclusive prevention programs.

Though alcohol is the most commonly abused drug amongst medical students, illicit drug use has also been reported at concerning levels. A survey of 36 United States medical schools revealed that approximately one-third of students had used illicit drugs within the past 12 months (Shah et al., 2009 ). Papazisis and colleagues similarly examined illicit drug use in undergraduate medical students in Greece, finding a lifetime substance use rate of ~25% ( 2017 ). Marijuana was the most common illicit drug used in both studies (Shah et al., 2009 ; Papazisis et al., 2017 ). Use of prescription medications without a prescription was also found amongst law students, particularly stimulants such as Ritalin, Adderall, and Concerta (Organ et al., 2016 ). These findings suggest that the competitive culture of graduate education may drive students to engage in recreational drug use, particularly those struggling to meet academic demands or suffering from mental distress.

Student burnout

Burnout was canonically defined by Freudenberger in 1974 as a state of physical and mental exhaustion caused by or related to work activities, often manifesting when heightened professional stress conflicts with personal ideals or expectations (Freudenberger, 1974 ; Rodrigues et al., 2018 ; Baro Vila et al., 2022 ). Though originally a descriptive disorder, burnout is now recognized in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, under code Z73.0 (Lacy and Chan, 2018 ). Burnout is traditionally diagnosed with the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a 22-item questionnaire that characterizes each of the three burnout domains: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment (Dyrbye and Shanafelt, 2016 ). Emotional exhaustion is associated with feelings of being overworked and a subsequent loss of compassion. Depersonalization is characterized by a sense of detachment from colleagues/patients and, when combined with emotional exhaustion, can result in unprofessional behavior. The personal accomplishment domain mainly describes an individual’s feelings of competence and professional satisfaction (Lacy and Chan, 2018 ). In addition to each domain’s unique consequences, burnout domains interact to cause an extinction of motivation when efforts no longer produce desired results (Vidhukumar and Hamza, 2020 ). Approximately 50% of fourth year medical students were found to have burnout when surveyed with the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Dyrbye and Shanafelt, 2016 ). This value holds true internationally according to a survey of medical students conducted in India (Vidhukumar and Hamza, 2020 ). Additionally, burnout increases as training progresses, particularly the depersonalization component (Dyrbye and Shanafelt, 2016 ). Burnout thus increases feelings of callousness towards patients, leading to unprofessional and potentially dangerous conduct. Burnout in medical school also appears to affect specialty choice; burned out individuals were more likely to choose specialties with more controllable lifestyles and higher pay (Dyrbye and Shanafelt, 2016 ). Investigating causes of burnout is thus of utmost importance to understand potential influences on medical student career trajectory and ensuring patient safety.

Identified causes of burnout appear to differ between the years of medical training. Preclinical years are characterized by dissatisfaction with the learning environment and lack of faculty support. Clinical years are characterized by dissatisfaction with the learning environment, clerkship disorganization, and working with cynical or abusive residents and/or attending physicians (Dyrbye and Shanafelt, 2016 ). Reed and colleagues found a positive correlation between the time spent in exams and burnout whereas a negative correlation was observed with increased patient interaction ( 2011 ). Several correlates of burnout outside of medical schools’ learning environments and curricula have also been described, including: female gender, dissatisfaction with career options, non-ethnic minority status, high educational debt, residency competition, expanding knowledge-base, workforce shortage, and stressful events in one’s personal life (Dyrbyre and Shanafelt, 2016 ; Vidhukumar and Hamza, 2020 ). Erosion of social ties during medical education also contributes to the burnout spiral, as socialization is protective against burnout symptoms (Bergmann et al., 2019 ; Busireddy et al., 2017 ). No associations between contact days, time in didactic learning or clinical experiences, and any measure of student well-being and burnout prevalence were found (Reed et al., 2011 ).

Interventions to improve well-being

Medical schools have implemented several interventions to reduce student distress and enhance wellness. Though interventional approaches are varied, researchers have identified salient features common to most successful wellness interventions. For example, Dyrbye and colleagues underline the importance of well-being committees that can liaise between administration, faculty, and students, lessening fear of admonishment for seeking help or acknowledging distress ( 2019 ). Additionally, Moir et al reports that student buy-in is absolutely essential, as disengaged wellness lectures offer little, if any, benefit ( 2016 ). Interventions appear most effective when they are designed to reduce student burdens, rather than adding to the already overwhelming schedule and content of medical school (Busireddy et al., 2017 ). Finally, administrations often pose an obstacle to wellness initiatives, especially those who believe that well-being is of minor importance. This obstacle is reflected by the low prevalence of medical schools with official wellness competencies built into the curriculum (Dyrbye et al., 2019 ). We will now explore some of the specific interventions medical schools have employed to improve student wellness.

Transitioning to a Pass/Fail (P/F) grading scheme is a wellness initiative that has received substantial attention in the United States, especially in light of findings that grade evaluation systems are a larger determinant of student well-being compared to content of educational contact hours (Reed et al., 2011 ; Spring et al., 2011 ). The Mayo Medical School examined the feasibility and effects of P/F grading by introducing the system to first-year medical students in 2006. Rohe and colleagues found that these first-year medical students reported less stress, better overall mood, and greater group cohesion compared to their graded peers. These characteristics persisted into the second year of medical school, even when grading reverted to a traditional 5-level schema (Rohe et al., 2006 ). While critics of P/F grading argue that students will be less motivated to excel academically, evidence suggests that first-year residents from P/F schools performed similarly to residents from graded schools (Rohe et al., 2006 ). Additionally, a P/F system reduces extrinsic motivation and intense competition while increasing cohesion and peer cooperation (Moir et al., 2018 ; Rohe et al., 2006 ). These qualities are essential in the increasingly team-based healthcare landscape. Though transitioning to a P/F system reduced medical student distress during the preclinical years, it is important to note that the transition did not decrease test anxiety for the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 1 (Williams et al., 2015 ; Rohe et al., 2006 ). Determining test anxiety for USMLE Step 1 will be an active area of research in the face of a new P/F grading for the licensure exam.

Allopathic and osteopathic medical programs are infamous for their academic rigors and intense curricular designs. These curricula are often described as competitive, leisure and socialization-deficient, and requiring exclusive dedication. These characteristics predispose medical students to decreased quality of life (Bergmann et al., 2019 ). As such, altering the curricula of these programs has been investigated as a means to prevent, rather than react to, student distress through a person-in-context perspective (Dyrbye et al., 2005 ; Slavin et al., 2012 ; Slavin et al., 2014 ). It has long been documented that the undergraduate medical curriculum is overflowing with information (D’Eon and Crawford, 2005 ). Rather than identifying salient features for inclusion in courses, medical school faculty often address this surplus of information by cramming unrealistic amounts of information into lectures (D’Eon and Crawford, 2005 ; Dyrbye et al., 2005 ). As mentioned earlier, wellness initiatives are often more effective when they reduce student burdens, rather than adding additional requirements (Busireddy et al., 2017 ). Though this may lead one to believe that shortening curricular hours is an intuitive wellness initiative, this measure only led to workload compression and feelings of being unprepared for clinical practice when used as a unifocal intervention (Dyrbye and Shanafelt 2016 ; Busireddy et al., 2017 ; Dyrbye et al., 2019 ). This continually expanding mass of information thus poses two challenges to wellness initiatives. First, medical students’ schedules are often too consumed by curricular hours to engage in additional wellness programming, especially without an external motivator. Second, the amount of information itself imposes feelings of distress on students, exacerbating the already-stressful nature of medical school and predisposition to mental health issues. Beyond the quantity of curricular hours, delivery and content of those hours is also important to student wellness. Lonka and colleagues found that a collaborative approach to learning increased satisfaction and decreased the perceived workload ( 2008 ). The collaborative environment of problem-based learning may thus offer some improvement to curriculum-induced stress, though current evidence is weak (Camp et al., 1994 ). Incorporating self-care workshops into the curriculum also appears to ameliorate the depersonalization component of burnout (Busireddy et al., 2017 ). In light of these promising results, it follows that the most powerful approach to improving student wellness through curricular restructuring is a multifactorial one. This multifactorial approach is best appreciated in the wellness initiatives within the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and the Saint Louis University School of Medicine (Drolet and Rodgers, 2010 ; Slavin et al., 2014 ).