Documents and Debates: Reconstructing the South

South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union when a convention in Charleston approved an Ordinance of Secession in December of 1860. Few Americans, during that tumultuous secession winter, foresaw a lengthy civil war. Few Americans predicted the war would bring horrific casualty rates, the devastation of the South, or the emancipation of four million African-American enslaved persons. As bitter as the armed struggle was, the political battle to reunite the Union was only beginning when the war staggered to a close in the spring of 1865. In hindsight, the political debate confronting the nation at the war’s conclusion seems equaled only by the logistical challenge of winning it.

Two main problems faced the nation at the end of the Civil War: how to rebuild the political connections between North and South, and how to protect the rights of the freedmen. Answering the first question depended on how one understood the South’s status. Had the seceding southern states left the Union? Should they be treated as a conquered nation, or had they remained in the Union with the constitutional right to reclaim their place in it? To ask the question another way: were the defeated confederates traitors to the nation? What proofs of loyalty did they need to offer before regaining their rights as citizens?

The second problem was closely related to the first. What assistance should the federal government render the freedmen and women justly demanding the full rights of citizenship, including suffrage? Would the former Confederates respect the rights of those formerly enslaved?

We recently introduced a newly organized resource on the Teaching American History website, designed to engage students in the debates of earlier generations. Teaching American History developed its two-volume Documents and Debates collection to help teachers present the issues at stake in some of the most crucial moments in American history. Each chapter in the collection presents a variety of viewpoints on one political or social question, along with an introduction giving context, study questions, and helpful notes. We are now adding a new tool : audio recordings of each chapter’s primary sources.

Two weeks ago we highlighted Chapter One: Early Contact from Documents and Debates, Volume 1: 1493 – 1865. Today we are highlighting the first chapter of Volume 2: Reconstructing the South . Below is a list of documents in this chapter.

- President Abraham Lincoln to Nathaniel Banks, August 5, 1863

- President Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865

- Representative Thaddeus Stevens, “Reconstruction,” September 6, 1865

- Frederick Douglass, “Reconstruction,” December 1866

- Jubilee Singers, “Many Thousand Gone,” 1872

- Senator Benjamin R. Tillman, Speech in the Senate, March 23, 1900

These documents in Reconstructing the South present the stark challenge of Reconstruction. Abraham Lincoln’s letter to Nathaniel Banks and his Second Inaugural Address convey the generous restoration of the Union he envisioned. Captured most poignantly in the Second Inaugural’s famous line “With malice toward none: with charity for all,” Lincoln’s plan was more lenient than that of his fellow Republican, Thaddeus Stevens. Stevens believed creating a “true republic” in the South required that “The whole fabric of Southern Society … be changed.” Stevens called for punishing rebel leaders, confederate soldiers, and large plantation owners.

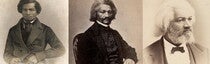

An even sharper contrast separates the speeches of Frederick Douglass and Benjamin Tillman. Douglass calls for “negro suffrage” as the freedman’s best defense against white southerners’ deeply ingrained attitudes about “manners, morals, and religion…” – creating “conditions, not out of which slavery will again grow, but under which it is impossible for the Federal government to wholly destroy it.” After the collapse of Reconstruction closed the small window of equality opened during the era, men like Benjamin Tillman unapologetically insisted on white supremacy. “We took the government away in 1876,” declared Tillman. “We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern the white men, and we never will. We have never believed him to be equal to the white man, and we will not submit to his gratifying lust on our wives and daughters without lynching him.”

For Lincoln, Stevens, and Douglass, Reconstruction promised a chance to rebuild the nation with citizens of all races having “learned to venerate the Declaration of Independence.” Yet perhaps all three, to differing extents, underestimated the difficulty re-educating the South in this way. Careful readers of the primary sources in Reconstructing the South may wonder if the promise of Reconstruction ever stood a chance of succeeding.

Access Reconstructing the South Here

Until this day: juneteenth and the end of slavery in the united states, eisenhower and the origins of the “military-industrial complex”, join your fellow teachers in exploring america’s history..

Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation and Freedom

- Explore the Collection

- Collections in Context

- Teaching the Collection

- Advanced Collection Research

Reconstruction, 1865-1877

Donald Brown, Harvard University, G6, English PhD Candidate

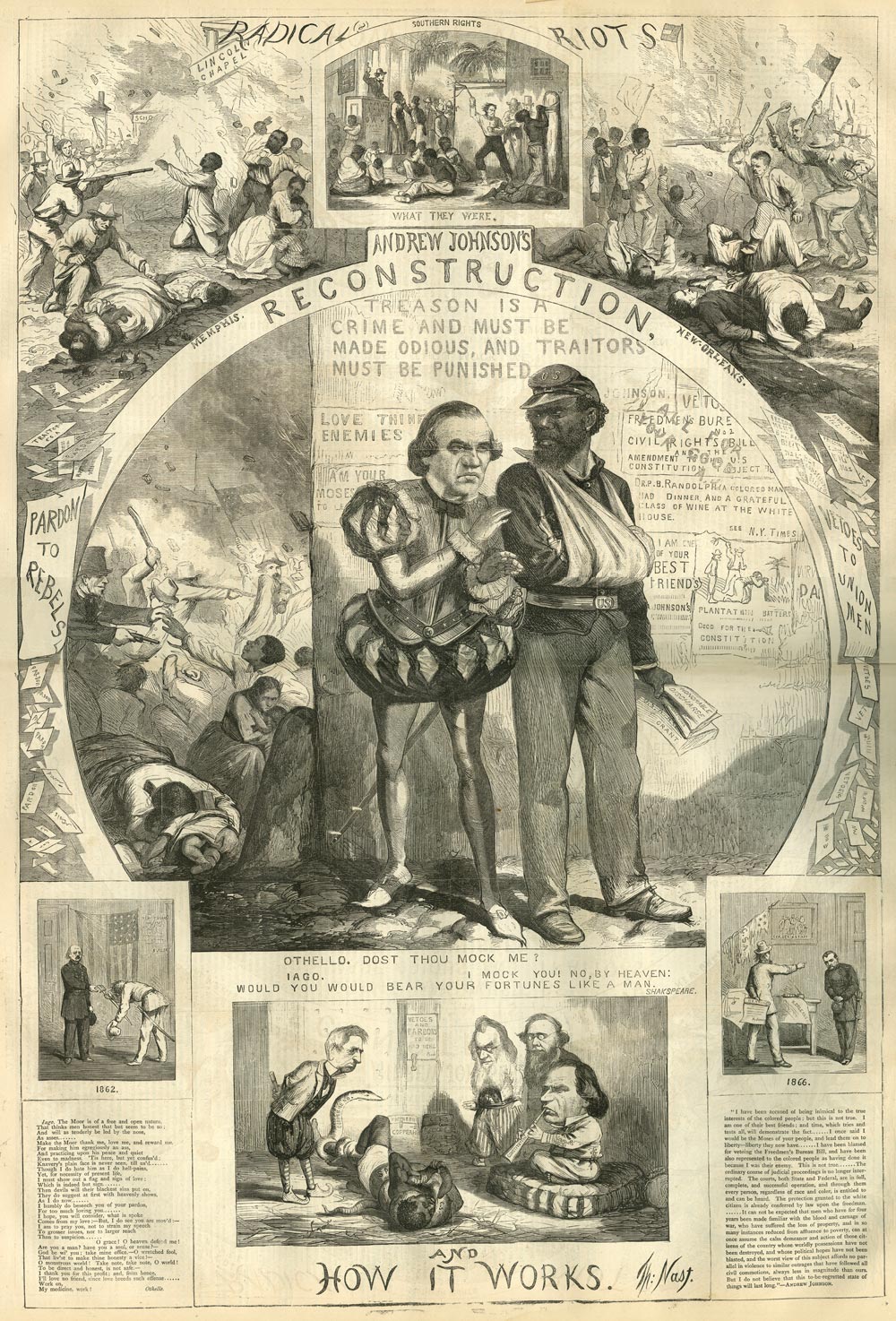

No period in American history has had more wide-reaching implications than Reconstruction. However, white supremacist mythologies about those contentious years from 1865-1877 reigned supreme both inside and outside the academy until the 1960s. Columbia University’s now-infamous Dunning School (1900-1930) epitomizes the dominant narrative regarding Reconstruction for over half of the twentieth century. From their point of view, Reconstruction was a tragic period of American history in which vengeful White Northern radicals took over the South. In order to punish the White Southerners they had just defeated in the Civil War, these Radical Republicans gave ignorant freedmen the right to vote. This resulted in at least 2,000 elected Black officeholders, including two United States senators and 21 representatives. In order to discredit the sweeping changes taking place across the American South, conservative historians argued this period was full of corruption and disorder and proved that Black Americans were not fit to leadership or citizenship.

Thanks to the work of a number of Black and leftist historians—most notably John Roy Lynch, W.E.B. Du Bois, Willie Lee Rose, and Eric Foner—that negative depiction of Reconstruction is being overturned. As Du Bois famously wrote in Black Reconstruction in America (1935), this was a time in which “the slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; and then moved back again toward slavery.” During that short time in the sun, underfunded biracial state governments taxed big planters to pay for education, healthcare, and roads that benefited everyone. There is still much more to be unpacked from this rich period of American history, and Houghton Library contains a wealth of material to further buttress new narratives of that era.

Reconstructing Reconstruction

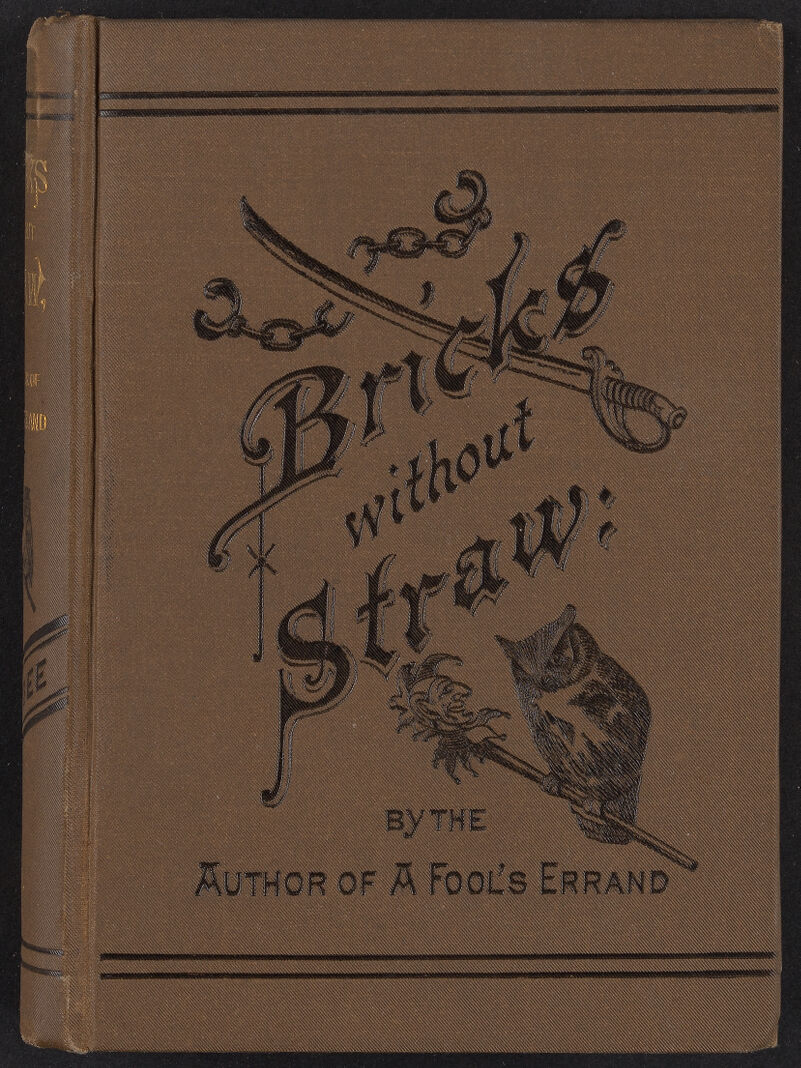

While some academics, like those of the Dunning School, interpreted Reconstruction as doomed to failure, in the years immediately following the Civil War there were many Americans, Black and White, who saw the radical reforms as being sabotaged from the outset. Writer and civil rights activist Albion W. Tourgée published his best selling novel Bricks Without Straw in 1880. Unlike most White authors at the time, Tourgée centered Black characters in his novel, showing how the recently emancipated were faced with violence and political oppression in spite of their attempts to be equal citizens.

In this period, two of the most iconic amendments were implemented. The Fourteenth Amendment ratified several crucial civil rights clauses. The natural born citizenship clause overturned the 1857 supreme court case, Dred Scott v. Sandford , which stated that descendants of African slaves could not be citizens of the United States. The equal protection clause ensured formerly enslaved persons crucial legal rights and validated the equality provisions contained in the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Even though many of these clauses were cleverly disregarded by numerous states once Reconstruction ended, particularly in the Deep South, the equal protection clause was the basis of the NAACP’s victory in the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed another important civil right: the right to vote. No longer could any state discriminate on the basis of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. At Houghton, we have proof of the exhilarating response Black Americans had to the momentous progress they worked so hard to bring about: Nashvillians organized a Fifteenth Amendment Celebration on May 4, 1870. And once again, during the classical period of the Civil Rights Movement, leaders appealed to this amendment to make their case for what became the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Reign of Kings Alpha and Abadon

Lorenzo D. Blackson's fantastical allegory novel, The Rise and Progress of the Kingdoms of Light & Darkness ; Reign of Kings Alpha and Abadon (1867), is one of the most ambitious creative efforts of Black authors during Reconstruction. A Protestant religious allegory in the lineage of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress , Blackson's novel follows his vision of a holy war between good and evil, showing slavery and racial oppression on the side of evil King Abadon and Protestant abolitionists and freemen on the side of good King Alpha. The combination of fantasy holy war, religious pedagogy, and Reconstruction era optimism provide a unique insight to one contemporary Black perspective on the time.

It is important to emphasize that these radical policy initiatives were set by Black Americans themselves. It was, in fact, from formerly enslaved persons, not those who formerly enslaved them, that the most robust notions of freedom were imagined and enacted. With the help of the nation’s first civil rights president, Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877), and Radical Republicans, such as Benjamin Franklin Wade and Thaddeus Stevens, substantial strides in racial advancement were made in those short twelve years. Houghton Library is home to a wide array of examples of said advancement, such as a letter written in 1855 by Frederick Douglass to Charles Sumner, the nation’s leading abolitionist. In it, he argues that Black Americans, not White abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, founded the antislavery movement. That being said, Douglass was appreciative of allies, such as President Grant, of whom he said: “in him the Negro found a protector, the Indian a friend, a vanquished foe a brother, an imperiled nation a savior.” Houghton Library also houses an extraordinary letter dated December 1, 1876 from Sojourner Truth , famous abolitionist and women’s rights activist, who could neither read nor write. She had someone help steady her hand so she could provide a signed letter to a fan, and promised to also send her supporter an autobiography, Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Bondswoman of Olden Time, Emancipated by the New York Legislature in the Early Part of the Present Century: with a History of Her Labors and Correspondence.

In this hopeful time, Black Americans, primarily located in the South, were determined to use their demographic power to demand their right to a portion of the wealth and property their labor had created. In states like South Carolina and Mississippi, which were majority Black at the time, and Louisiana , Alabama, and Georgia , with Black Americans consisting of nearly half of the population, the United States elected its first Black U.S. congressmen. Now that Black Southern men had the power to vote, they eagerly elected Black men to represent their best interests. Jefferson Franklin Long (U.S. congressman from Georgia), Joseph Hayne Rainey (U.S. congressman from South Carolina), and Hiram Rhodes Revels (Mississippi U.S. Senator) all took office in the 41st Congress (1869-1871). These elected officials were memorialized in a lithograph by popular firm Currier and Ives. Other federal agencies, such as the Freedmen’s Bureau , also assisted Black Americans build businesses, churches, and schools; own land and cultivate crops; and more generally establish cultural and economic autonomy. As Frederick Douglass wrote in 1870, “at last, at last the black man has a future.”

Black Americans quickly took full advantage of their newfound freedom in a myriad of ways. Alfred Islay Walden’s story is a particularly remarkable example of this. Born a slave in Randolph County, North Carolina, he only gained freedom after Emancipation. He traveled by foot to Washington, D.C. and made a living selling poems and giving lectures across the Northeast. He also attended school at Howard University on scholarship, graduating in 1876, and used that formal education to establish a mission school and become one of the first Black graduates of New Brunswick Theological Seminary. Walden’s Miscellaneous Poems, Which The Author Desires to Dedicate to The Cause of Education and Humanity (1872) celebrates the “Impeachment of President Johnson,” one of the most racist presidents in American history; “The Election of Mayor Bowen,” a Radical Republican mayor of Washington, D.C. (Sayles Jenks Bowen); and Walden’s own religious convictions, such as in “Jesus my Friend;” among other topics.

Black newspapers quickly emerged during Reconstruction as well, such as the Colored Representative , a Black newspaper based in Lexington, KY in the 1870s. As editor George B. Thomas wrote in an “Extra,” dated May 25, 1871 : “We want all the arts and fashions of the North, East and Western states, for the benefit of the colored people. They cannot know what is going on, unless they read our paper.... Now, we want everything that is a benefit to our colored people. Speeches, debates, and sermons will be published.”

Reconstruction proves that Black people, when not impeded by structural barriers, are enthusiastic civic participants. Houghton houses rich archival material on Black Americans advocating for civil rights in Vicksburg, Mississippi , Little Rock, Arkansas , and Atlanta, Georgia , among other states, in the forms of state Colored Conventions and powerful political speeches . For anyone interested in the long history of the Civil Rights Movement, these holdings are a treasure trove waiting to be mined. Though the moment in the sun was brief, the heat exuded during Reconstruction left a deep impact on progressive Americans and will continue to provide an exemplary political model for generations to come.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Reconstruction

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 24, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

Reconstruction (1865-1877), the turbulent era following the Civil War, was the effort to reintegrate Southern states from the Confederacy and 4 million newly-freed people into the United States. Under the administration of President Andrew Johnson in 1865 and 1866, new southern state legislatures passed restrictive “ Black Codes ” to control the labor and behavior of former enslaved people and other African Americans.

Outrage in the North over these codes eroded support for the approach known as Presidential Reconstruction and led to the triumph of the more radical wing of the Republican Party. During Radical Reconstruction, which began with the passage of the Reconstruction Act of 1867, newly enfranchised Black people gained a voice in government for the first time in American history, winning election to southern state legislatures and even to the U.S. Congress. In less than a decade, however, reactionary forces—including the Ku Klux Klan —would reverse the changes wrought by Radical Reconstruction in a violent backlash that restored white supremacy in the South.

Emancipation and Reconstruction

At the outset of the Civil War , to the dismay of the more radical abolitionists in the North, President Abraham Lincoln did not make abolition of slavery a goal of the Union war effort. To do so, he feared, would drive the border slave states still loyal to the Union into the Confederacy and anger more conservative northerners. By the summer of 1862, however, enslaved people, themselves had pushed the issue, heading by the thousands to the Union lines as Lincoln’s troops marched through the South.

Their actions debunked one of the strongest myths underlying Southern devotion to the “peculiar institution”—that many enslaved people were truly content in bondage—and convinced Lincoln that emancipation had become a political and military necessity. In response to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation , which freed more than 3 million enslaved people in the Confederate states by January 1, 1863, Black people enlisted in the Union Army in large numbers, reaching some 180,000 by war’s end.

Did you know? During Reconstruction, the Republican Party in the South represented a coalition of Black people (who made up the overwhelming majority of Republican voters in the region) along with "carpetbaggers" and "scalawags," as white Republicans from the North and South, respectively, were known.

Emancipation changed the stakes of the Civil War, ensuring that a Union victory would mean large-scale social revolution in the South. It was still very unclear, however, what form this revolution would take. Over the next several years, Lincoln considered ideas about how to welcome the devastated South back into the Union, but as the war drew to a close in early 1865, he still had no clear plan.

In a speech delivered on April 11, while referring to plans for Reconstruction in Louisiana, Lincoln proposed that some Black people–including free Black people and those who had enlisted in the military –deserved the right to vote. He was assassinated three days later, however, and it would fall to his successor to put plans for Reconstruction in place.

Andrew Johnson and Presidential Reconstruction

At the end of May 1865, President Andrew Johnson announced his plans for Reconstruction, which reflected both his staunch Unionism and his firm belief in states’ rights. In Johnson’s view, the southern states had never given up their right to govern themselves, and the federal government had no right to determine voting requirements or other questions at the state level.

Under Johnson’s Presidential Reconstruction, all land that had been confiscated by the Union Army and distributed to the formerly enslaved people by the army or the Freedmen’s Bureau (established by Congress in 1865) reverted to its prewar owners. Apart from being required to uphold the abolition of slavery (in compliance with the 13th Amendment to the Constitution ), swear loyalty to the Union and pay off war debt, southern state governments were given free rein to rebuild themselves.

As a result of Johnson’s leniency, many southern states in 1865 and 1866 successfully enacted a series of laws known as the “ black codes ,” which were designed to restrict freed Black peoples’ activity and ensure their availability as a labor force. These repressive codes enraged many in the North, including numerous members of Congress, which refused to seat congressmen and senators elected from the southern states.

In early 1866, Congress passed the Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil Rights Bills and sent them to Johnson for his signature. The first bill extended the life of the bureau, originally established as a temporary organization charged with assisting refugees and formerly enslaved people, while the second defined all persons born in the United States as national citizens who were to enjoy equality before the law. After Johnson vetoed the bills—causing a permanent rupture in his relationship with Congress that would culminate in his impeachment in 1868—the Civil Rights Act became the first major bill to become law over presidential veto.

Radical Reconstruction

After northern voters rejected Johnson’s policies in the congressional elections in late 1866, Radical Republicans in Congress took firm hold of Reconstruction in the South. The following March, again over Johnson’s veto, Congress passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which temporarily divided the South into five military districts and outlined how governments based on universal (male) suffrage were to be organized. The law also required southern states to ratify the 14th Amendment , which broadened the definition of citizenship, granting “equal protection” of the Constitution to formerly enslaved people, before they could rejoin the Union. In February 1869, Congress approved the 15th Amendment (adopted in 1870), which guaranteed that a citizen’s right to vote would not be denied “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

By 1870, all of the former Confederate states had been admitted to the Union, and the state constitutions during the years of Radical Reconstruction were the most progressive in the region’s history. The participation of African Americans in southern public life after 1867 would be by far the most radical development of Reconstruction, which was essentially a large-scale experiment in interracial democracy unlike that of any other society following the abolition of slavery.

Southern Black people won election to southern state governments and even to the U.S. Congress during this period. Among the other achievements of Reconstruction were the South’s first state-funded public school systems, more equitable taxation legislation, laws against racial discrimination in public transport and accommodations and ambitious economic development programs (including aid to railroads and other enterprises).

Reconstruction Comes to an End

After 1867, an increasing number of southern whites turned to violence in response to the revolutionary changes of Radical Reconstruction. The Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations targeted local Republican leaders, white and Black, and other African Americans who challenged white authority. Though federal legislation passed during the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant in 1871 took aim at the Klan and others who attempted to interfere with Black suffrage and other political rights, white supremacy gradually reasserted its hold on the South after the early 1870s as support for Reconstruction waned.

Racism was still a potent force in both South and North, and Republicans became more conservative and less egalitarian as the decade continued. In 1874—after an economic depression plunged much of the South into poverty—the Democratic Party won control of the House of Representatives for the first time since the Civil War.

When Democrats waged a campaign of violence to take control of Mississippi in 1875, Grant refused to send federal troops, marking the end of federal support for Reconstruction-era state governments in the South. By 1876, only Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina were still in Republican hands. In the contested presidential election that year, Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes reached a compromise with Democrats in Congress: In exchange for certification of his election, he acknowledged Democratic control of the entire South.

The Compromise of 1876 marked the end of Reconstruction as a distinct period, but the struggle to deal with the revolution ushered in by slavery’s eradication would continue in the South and elsewhere long after that date.

A century later, the legacy of Reconstruction would be revived during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, as African Americans fought for the political, economic and social equality that had long been denied them.

HISTORY Vault: The Secret History of the Civil War

The American Civil War is one of the most studied and dissected events in our history—but what you don't know may surprise you.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Reconstruction in the South

Fitzhugh brundage.

The study of the Reconstruction era in the South may appear free of the vexing problems of definition and chronology that beset many historical topics. On its face, Reconstruction was the discrete historical process of reintegrating the former Confederacy into the American nation. This process began as soon as the Union captured territory in the Confederacy (circa late 1861) and concluded with the compromise after the disputed election of 1876, which marked the restoration of home rule by southern whites. This chronology was conventional before Woodrow Wilson employed it in his History of the American People (1902); and even during the 1960s and 1970s, an especially fertile period for scholarship on Reconstruction, historians betrayed few reservations about either this definition or chronology of Reconstruction.

Like many keywords, with a nod to Raymond Williams, “Reconstruction” is a word (and concept) with a complicated history and layer upon layer of latent meanings. Some Democrats and white southerners, admittedly, preferred the term “Restoration,” which conveyed a comforting image of an ordered and gentle process of sectional reincorporation. Many other contemporaries used “Reconstruction” to describe the process of reunification, but they seldom used it as a label for the epoch in which they lived. Thus, unlike many labels that subsequently were attached to historical periods—the antebellum era, for instance—Reconstruction was not an anachronism imposed by succeeding generations. However, the word now is routinely applied not only to the postbellum process of national restoration but also to the entire 1862–77 period.

This usage was consonant with the conventions of the teaching of American history, which until recently broke the nation’s narrative up into tidy, bite-sized units. The nineteenth century was conveniently segmented into a series of roughly two-decade-long eras: the Early Republic, Jacksonian America, antebellum America, Civil War and Reconstruction, Gilded Age. Given the emphasis on political history and the prevalence of temporally discrete (rather than thematic) college history courses, these divisions were both reasonable and convenient. This periodization now is receding in the rear view of history, or so it seems, if present-day undergraduate course titles and academic job listings are valid indicators. Job ads now more commonly solicit applications from nineteenth-century specialists than, say, historians of the Jacksonian or Gilded Age United States.

As scholars shift their interests to the longue durée of the nineteenth century, Reconstruction necessarily loses much of its utility as a descriptor for the subjects and questions that scholars are interested in. For one, the temporal boundaries of “Reconstruction” almost certainly will be much more permeable in the future than they were during the twentieth century. The issues associated with the penetration of Union forces into the Confederacy, beginning in the fall of 1861, will remain central to any treatment of the destruction of slavery, restoration of federal authority, and the economic reintegration of the South. But the “rehearsal for Reconstruction,” with due respect for Willie Lee Rose’s enduring classic work, antedated the events in, for instance, the Sea Islands of South Carolina in late 1861 or eastern North Carolina in 1862. [1] Although admittedly marked by contradictions, experimentation, and confusion, the programs adopted and policies applied as early as November 1861 mark the early implementation of the reconstruction of the South.

The conceptual rehearsals for reconstruction antedated the Civil War itself. Even so-called moderate plans for southern reconstruction, such as that of President Lincoln, were audacious visions of social engineering. They presumed profound, far-reaching, and enduring transformations in southern institutions, culture, and behavior on a scale that borders on utopian. From whence did visionaries of a remade South derive their ideas of societal transformation and their optimism about the capacity of the South to be remade? What historical analogies did they draw between their vision for the South and previous or contemporary events? Which societal transformations did they deem feasible? Which transformations infeasible?

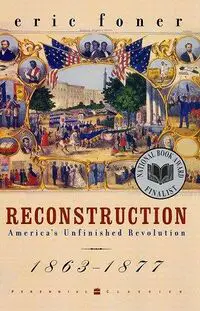

We can cobble together a partial answer to these questions from existing scholarship, including important works by Eric Foner, Susan-Mary Grant, James Oakes, and Heather Cox Richardson . [2] But we await a comprehensive history of the ideas of social transformation that circulated in the mid-nineteenth-century United States and informed ideas about reforming the South. Such a history will reveal the various combinations of religious millennialism, “free labor” capitalism, sentimental moralism, political ideology, historical analogies, and old fashioned American hubris that informed plans for a new South.

The task at hand is not just locating the intellectual resources that provided the conceptual architecture for visions of a remade South but also tracing the evolution of those ideas across time. For example, the efforts of Illinois Republicans to “reconstruct” “Egypt” in southern Illinois during the late 1850s was a test of the capacity of expanding public education, market penetration (made possible by railroads), and political mobilization to reform a regional culture that was deeply pro-southern, anti-black, and Democratic. The attempted re-creation of Egypt was a dry run of methods that the Republicans envisioned applying to the South when their party gained the White House. Their plans, however, failed to transform the inhabitants of the region or to pry them away from the Democratic Party. Given the failure of the prewar and wartime efforts to reconstruct Egypt, we might wonder how Republicans were so sanguine that the purportedly inherent virtues of their program would appeal to white southerners. [3]

While the “reconstruction” of antebellum southern Illinois provides some insights into how Republicans imagined the reconstruction of the Slave South before the war dramatically altered the possibilities for intervention in southern affairs, the response to national and international events after the Civil War underscores the breadth of influences that contributed to the recalibration of possibilities of reconstruction. Growing fervor among American workers for the eight-hour workday and the tumult of the Paris Commune, for example, provoked anxiety among some northern champions of “reconstruction,” such as E. L. Godkin of the Nation , that private property and individual liberty were increasingly threatened by the poor demanding cooperative economic action and redistribution of wealth. For skeptics of government activism, the folly of Reconstruction was an American counterpart to the Paris Commune—a dangerous threat to the foundations of civilization itself. Property rights, the natural ordering of society on the basis of innate talent and abilities, and the respect for order had all been subverted in the cause of naïve social and racial uplift. In response, these erstwhile reformers began their “retreat from Reconstruction” well before President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration began its own retreat. [4]

If there are ample grounds to expand the discussion of “reconstruction” to the antebellum era, there are even more compelling reasons to reconsider the conventional temporal conclusion of Reconstruction. First, it exaggerates the significance of the election of 1876 and the so-called Compromise of 1877. C. Vann Woodward offered the most enduring argument about the importance of the informal agreement between Democrats and Republicans that traded Democratic acquiescence to the election of Rutherford B. Hayes in return for the removal of the federal troops from the South, support for a southern transcontinental railroad, and investment in the South. [5] But the purported compromise arguably only signaled the inevitable end of federal “occupation” of the few remaining areas in the South where troops were garrisoned. The deep processes of political, economic, and social transformation under way in the South proceeded apace after 1877. It is not clear that the “compromise” marked the moment when the Republican Party abandoned the freedpeople in the South to their fate at the hands of white southerners. A more compelling case for the abandonment of southern blacks by the party of Lincoln can be made for 1890 when Republicans failed to secure passage of the Federal Elections Bill (aka Lodge Force Bill), which would have established strict(er) standards for federal elections, thereby expanding and protecting black voting in the South. In the wake of the defeat of the Lodge Bill, white Democrats in Mississippi and elsewhere expanded their legal and constitutional machinations to deprive blacks of the vote. The “reconstruction” of the southern electorate, consequently, remained at issue for more than a decade after the purported end of Reconstruction in 1877. [6]

Second, the “reconstruction” of political partisanship in the South was by no means complete in 1877. Between 1865 and the end of the century politics in the South was marked by striking political pluralism. Not only did the Republican Party remain electorally viable in many states, but also insurgent parties, ranging from the Greenback and Readjuster Parties to the People’s Party (aka Populists), won followers in the region. The issues that fueled and the ideological communities that sustained this heightened partisan environment in the region were remarkably consistent across the period from 1865 to 1900. The Readjuster Party in Virginia, for example, was a biracial political vehicle founded after 1877 that rallied white and black voters who sought to revise (“readjust”) Virginia’s inherited and onerous debt. The party admittedly was sui generis in important regards, but the fiscal issues it addressed, the political coalitions it forged, and the social and racial challenges it confronted were extensions of the politics of postbellum readjustment. The Democrats in Virginia did not finally drive the last of the major Readjuster politicos from office until 1889. [7] Moreover, two important recent studies of the postbellum era have stressed the continuity in southern public life from the Civil War era into the early decades of the twentieth century. Greg Downs describes a half-century period during which hard-pressed southerners fashioned a form of patron-client politics that recast dependency into the foundation of regional politics. [8] Steve Hahn has traced the formation of black political networks and consciousness during slavery and its subsequent influence through the late nineteenth century and to the 1920s. [9]

Third, the economic “reconstruction” of southern society in the wake of the Civil War and abolition of slavery does not mesh with the conventional periodization of Reconstruction. Peter Coclanis makes a compelling case that deep structural transformations, especially global commodity markets and finance, were underway in the mid-nineteenth-century American economy that were largely independent of the Civil War and the fate of plantation slavery. [10] The expansion of American capitalism and changes in international commodity demand contributed to the extraordinary economic uncertainty that prevailed in the region across the late nineteenth century. Scholars have long recognized that transition from slave to free labor was jarring and contested, but there was a common assumption that by the 1870s sharecropping had emerged as a practical solution to matching labor, land, and capital in the region. Recent scholarship suggests that a wide variety of complex labor relations prevailed for decades after the end of the Civil War and that the southern economy continued to be roiled by change and innovation. Similarly, it took decades for the reconstructed southern legal system to provide sufficient legal guarantees to elicit sustained capital investments from outside the region. The political tumult in the region directly contributed to a perception of the South as a region filled with risk and uncertainty. [11]

Finally, southern society remained deeply fragmented after 1876. As important scholarship during the past quarter century has demonstrated, the “reconstruction” of gender roles and politics was by no means completed in 1876, let alone 1890. Conventional periodization of Reconstruction can mask the extent and persistence of this ongoing transformation in the southern polity and social relations. The essential and enduring role of women in civic activism, commemoration, household management, and the regional labor market is now clear. [12] It is also telling that the forms of violence that were endemic in the region—personal, political, and extralegal violence—persisted at high levels for decades after the end of Reconstruction. At best only a superficial semblance of peace and order returned there during the late 1870s and 1880s. [13] A final illustration of important trends that persisted uninterrupted across the Reconstruction era and late nineteenth century is the seeming inexorable movement of white and black southerners to new agricultural frontiers in the region and from the countryside to mill towns and cities.

Embracing a more capacious and flexible periodization of reconstruction is not intended to dismiss long-emphasized themes or “turning points” in the scholarship, such as the Emancipation Proclamation, Presidential Reconstruction, Radical Reconstruction, the so-called Reconstruction constitutional amendments, or the retreat from Reconstruction. To the contrary, these events will remain central to the interpretation of the longue durée of reconstruction. But attention to the longue durée allows us to better recognize the asynchronous pattern and speed of change in the region. And it will enable scholars to more completely (re)present the experiences of southerners after the Civil War. To take one poignant example, the impact of the postwar impoverishment of the region bore down on southerners for the remainder of their lives. A recent study of the biostatistics of cadets at The Citadel reveals that the cadets during the late nineteenth century were smaller in stature and weight than their antebellum predecessors. The bodies of the postwar cadets were living testaments to the legacy of war and reconstruction. [14]

FITZHUGH BRUNDAGE is William B. Umstead Distinguished Professor of history and department chair at the University of North Carolina. He is the author or editor of numerous articles and books, including, most recently, Beyond Blackface: African Americans and the Creation of American Popular Culture, 1890-1930 (UNC Press, 2011). His book, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (Harvard University Press, 2005), won the 2006 Charles S. Sydnor Award from the Southern Historical Association.

[1] Willie Lee Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment (New York: Vintage, 1964). [2] Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970); Susan-Mary Grant, North over South: Northern Nationalism and American Identity in the Antebellum Era (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000); James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865 (New York: Norton, 2013); Heather Cox Richardson, The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post–Civil War North, 1865–1901 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001). [3] Eric Michael Burke, “Egyptian Darkness: Antebellum Reconstruction and Southern Illinois in the Republican Imagination, 1854–1861” (MA thesis, University of North Carolina, 2016); also Richard H. Abbott, The Republican Party and the South, 1855–1877: The First Southern Strategy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986); and Grant, North over South. [4] Nancy Cohen, The Reconstruction of American Liberalism, 1865–1914 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); William Gillette, Retreat from Reconstruction, 1869–1879 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979.) [5] C. Vann Woodward, Reunion and Reaction; The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction (New York: Little, Brown, 1951). [6] Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2000); Vanessa Holloway, In Search of Federal Enforcement: The Moral Authority of the Fifteenth Amendment and the Integrity of the Black Ballot, 1870–1965 (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 2015). [7] Jane Elizabeth Dailey, Before Jim Crow: The Politics of Race in Postemancipation Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.). [8] Gregory P. Downs, Declarations of Dependence: The Long Reconstruction of Popular Politics in the South, 1861–1908 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011). [9] Steven Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South, from Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003). [10] Peter Coclanis, “The American Civil War and Its Aftermath,” in Cambridge World History of Slavery, vol. 4 of 4, A.D. 1804–A.D. 2016 , eds. Stanley L. Engerman, David Eltis, and David Richardson (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017). [11] Downs, “The Mexicanization of American Politics: The United States’ Transnational Path from Civil War to Stabilization,” American Historical Review 117, no. 2 (2012): 387–409. [12] Elsa Barkley Brown, “Uncle Ned’s Children: Negotiating Community and Freedom in Postemancipation Richmond, Virginia” (PhD diss., Kent State University, 1994); Laura F. Edwards, Gendered Strife and Confusion: The Political Culture of Reconstruction (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997); Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996); Joan Marie Johnson, Southern Ladies, New Women: Race, Region, and Clubwomen in South Carolina, 1890–1930 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004); Caroline E. Janney, Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies’ Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008); LeeAnn Whites, Gender Matters: Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Making of the New South (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005). [13] Hannah Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009); Kidada E. Williams, They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I (New York: New York University Press, 2012); and George C Wright, Racial Violence in Kentucky, 1865–1940: Lynchings, Mob Rule, and “Legal Lynchings” (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990). [14] Peter A. Coclanis and John Komlos, “The Stature of Citadel Cadets, 1880–1940: An Anthropometric View of the New South,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 98, no. 2 (1997): 153–76.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

One Reply to “Reconstruction in the South”

Thank you for this very deep article about the South reconstruction after the Civil War ! Very interesting !

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Recent Muster Posts

- How the Federal Government Came to Control Immigration Policy and Why it Matters

- Previewing the March 2024 JCWE

- Beyond the Book Review: A Conversation with Chad Pearson

- Author Interview: Hidetaka Hirota

- Author Interview: Tian Xu

Read the Journal Online at Project Muse

Follow us on Twitter

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

Examining Reconstruction Fall 2019

Past Issues

69 | The Reception and Impact of the Declaration of Independence, 1776-1826 | Winter 2023

68 | The Role of Spain in the American Revolution | Fall 2023

67 | The Influence of the Declaration of Independence on the Civil War and Reconstruction Era | Summer 2023

66 | Hispanic Heroes in American History | Spring 2023

65 | Asian American Immigration and US Policy | Winter 2022

64 | New Light on the Declaration and Its Signers | Fall 2022

63 | The Declaration of Independence and the Long Struggle for Equality in America | Summer 2022

62 | The Honored Dead: African American Cemeteries, Graveyards, and Burial Grounds | Spring 2022

61 | The Declaration of Independence and the Origins of Self-Determination in the Modern World | Fall 2021

60 | Black Lives in the Founding Era | Summer 2021

59 | American Indians in Leadership | Winter 2021

58 | Resilience, Recovery, and Resurgence in the Wake of Disasters | Fall 2020

57 | Black Voices in American Historiography | Summer 2020

56 | The Nineteenth Amendment and Beyond | Spring 2020

55 | Examining Reconstruction | Fall 2019

54 | African American Women in Leadership | Summer 2019

53 | The Hispanic Legacy in American History | Winter 2019

52 | The History of US Immigration Laws | Fall 2018

51 | The Evolution of Voting Rights | Summer 2018

50 | Frederick Douglass at 200 | Winter 2018

49 | Excavating American History | Fall 2017

48 | Jazz, the Blues, and American Identity | Summer 2017

47 | American Women in Leadership | Winter 2017

46 | African American Soldiers | Fall 2016

45 | American History in Visual Art | Summer 2016

44 | Alexander Hamilton in the American Imagination | Winter 2016

43 | Wartime Memoirs and Letters from the American Revolution to Vietnam | Fall 2015

42 | The Role of China in US History | Spring 2015

41 | The Civil Rights Act of 1964: Legislating Equality | Winter 2015

40 | Disasters in Modern American History | Fall 2014

39 | American Poets, American History | Spring 2014

38 | The Joining of the Rails: The Transcontinental Railroad | Winter 2014

37 | Gettysburg: Insights and Perspectives | Fall 2013

36 | Great Inaugural Addresses | Summer 2013

35 | America’s First Ladies | Spring 2013

34 | The Revolutionary Age | Winter 2012

33 | Electing a President | Fall 2012

32 | The Music and History of Our Times | Summer 2012

31 | Perspectives on America’s Wars | Spring 2012

30 | American Reform Movements | Winter 2012

29 | Religion in the Colonial World | Fall 2011

28 | American Indians | Summer 2011

27 | The Cold War | Spring 2011

26 | New Interpretations of the Civil War | Winter 2010

25 | Three Worlds Meet | Fall 2010

24 | Shaping the American Economy | Summer 2010

23 | Turning Points in American Sports | Spring 2010

22 | Andrew Jackson and His World | Winter 2009

21 | The American Revolution | Fall 2009

20 | High Crimes and Misdemeanors | Summer 2009

19 | The Great Depression | Spring 2009

18 | Abraham Lincoln in His Time and Ours | Winter 2008

17 | Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Era | Fall 2008

16 | Books That Changed History | Summer 2008

15 | The Supreme Court | Spring 2008

14 | World War II | Winter 2007

13 | The Constitution | Fall 2007

12 | The Age Of Exploration | Summer 2007

11 | American Cities | Spring 2007

10 | Nineteenth Century Technology | Winter 2006

9 | The American West | Fall 2006

8 | The Civil Rights Movement | Summer 2006

7 | Women's Suffrage | Spring 2006

6 | Lincoln | Winter 2005

5 | Abolition | Fall 2005

4 | American National Holidays | Summer 2005

3 | Immigration | Spring 2005

2 | Primary Sources on Slavery | Winter 2004

1 | Elections | Fall 2004

Citizenship in the Reconstruction South

By susanna lee.

Slaveholders created a system of race, gender, and class inequality in the pre-Civil War South. They justified slavery by arguing that enslaved people could not take care of themselves and needed masters to look after them. White southern proslavery advocates compared slavery to marriage: masters supported their slaves, just as men supported their wives. Most white men excluded black men, black women, and white women from public affairs. Even non-elite white men—like non-slaveholders and other poor and middle-class southerners—found themselves in lesser positions. Elite slaveholding white men considered themselves best able to lead, and they dominated political offices. To differing extents, black men, black women, white women, and non-elite white men in the pre-Civil War South were subordinate members of the nation. The upheavals of the Civil War and Reconstruction brought opportunities to transform citizenship in the United States, determining who belonged to the nation, and what rights and privileges that membership conferred.

Black southerners, once considered least capable of acting as good citizens before the Civil War, transformed the idea and practice of citizenship during Reconstruction. Before the Civil War, most white people thought that black people, because of their supposed racial inferiority or because of the degradation of slavery, could not govern themselves as free people, let alone others as voters or officeholders. During the Civil War, black people proved the opposite, offering their support for the Union cause by the thousands. Black men made one of the greatest sacrifices for their nation—fighting and dying on the battlefield—even before that nation officially recognized them as citizens.

Under Presidential Reconstruction, former slaveholders tried to reassert their control over their former slaves in many ways: by terrorizing and assaulting them, forcing them into involuntary labor, restricting their freedom of movement, and limiting their economic independence. Black southerners refused to accept the freedom-in-name-only offered by their former masters and mistresses. They petitioned, protested, and fought for the dignities, rights, and privileges of citizenship in the nation. At a freedmen’s convention in Virginia in August 1865, leaders of the African American community criticized Presidential Reconstruction:

We, the undersigned members of a Convention of colored citizens of the State of Virginia, would respectfully represent that, although we have been held as slaves, and denied all recognition as a constituent of your nationality for almost the entire period of the duration of your Government, and that by your permission we have been denied either home or country, and deprived of the dearest rights of human nature: yet when you and our immediate oppressors met in deadly conflict upon the field of battle—the one to destroy and the other to save your Government and nationality, we , with scarce an exception, in our inmost souls espoused your cause, and watched, and prayed, and waited, and labored for your success. . . . When the contest waxed long, and the result hung doubtfully, you appealed to us for help, and how well we answered is written in the rosters of the two hundred thousand colored troops now enrolled in your service; and as to our undying devotion to your cause, let the uniform acclamation of escaped prisoners, “whenever we saw a black face we felt sure of a friend,” answer. Well, the war is over, the rebellion is “put down,” and we are declared free! Four fifths of our enemies are paroled or amnestied, and the other fifth are being pardoned, and the President has, in his efforts at the reconstruction of the civil government of the States, late in rebellion, left us entirely at the mercy of these subjugated but unconverted rebels, in everything save the privilege of bringing us, our wives and little ones, to the auction block. . . . We know these men—know them well —and we assure you that, with the majority of them, loyalty is only “lip deep,” and that their professions of loyalty are used as a cover to the cherished design of getting restored to their former relations with the Federal Government, and then, by all sorts of “unfriendly legislation,” to render the freedom you have given us more intolerable than the slavery they intended for us. [3]

Black southerners had served their nation during the Civil War, and they called on the federal government to protect them during Reconstruction.

Black people’s efforts to fight the re-imposition of white supremacy by former slaveholders and to publicize attacks on black and white Unionists prompted congressional Republicans to take steps to protect freedoms in the South during a period called Congressional Reconstruction. They provided for a new process, one very different from Presidential Reconstruction, in which black and white men who had been loyal to the Union during the Civil War formed new state governments in the South. Congressional Republicans considered stripping former Confederates of their citizenship, but settled for prohibiting them from participating in forming the new state governments. During Congressional Reconstruction, the United States officially granted citizenship and rights to black people. The Fourteenth Amendment, passed in 1866 and ratified in 1868, established birthright citizenship and prohibited states from abridging the privileges and immunities of citizenship. The Fifteenth Amendment, passed in 1869 and ratified in 1870, prohibited states from denying citizens the right to vote on account of race, but not sex. The establishment of birthright citizenship—that people born in the United States, regardless of race, possessed the rights and privileges of citizenship—corrected what many Republicans saw as the unjust decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), that black people could not claim citizenship and that they had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The Reconstruction Amendments and other Reconstruction measures were powerful and unprecedented efforts by the federal government to define and protect citizens, especially those newly freed from slavery.

During Congressional Reconstruction, black southerners allied with white southerners, especially those who had previously held little political or economic power. Through the Republican Party, black and white southerners acted as citizens in an unprecedented interracial alliance that brought democratic reforms to the South, especially greater rights and protections to everyday folk, those whose humble standing or racial status had previously marked them for discrimination. New state constitutions drafted during Congressional Reconstruction established state-funded systems of public education and other government institutions for common people, abolished property-holding qualifications for office-holding and jury service, prohibited imprisonment for debt, and exempted homesteads and other personal property from seizure by creditors.

White women outside the South, drawing on Congressional Reconstruction’s egalitarian promise, called for the expansion of women’s rights as citizens, especially their political and economic rights. White women in the South did not form a comparable women’s rights movement. Regardless, efforts to enfranchise women in the Reconstruction Amendments failed. In addition, none of the new state constitutions written under Congressional Reconstruction provided for female suffrage. Constitutional conventions in Texas, North Carolina, and Arkansas considered but ultimately rejected women’s suffrage. [4] Women’s rights activists did succeed in securing some economic rights. Most wives had no legal identity separate from their husbands, which prevented them from owning property or controlling their own wages. State legislators passed laws after the Civil War that allowed married women to hold their own property. However, southern legislators passed these married women’s property acts primarily as a way to shield the husbands’ property from creditors, not as a women’s rights reform. [5] The failure of women’s suffrage and the conservative nature of married women’s property acts in the South suggest the larger opposition of many white southerners to the transformations of Congressional Reconstruction.

Many former Confederates, especially former slaveholders, organized themselves into the Conservative or Democratic Party and opposed Congressional Reconstruction, often violently. They embraced terrorism in the form of groups like the Ku Klux Klan who intimidated and murdered black and white Republicans. Federal officials withdrew support for Congressional Reconstruction, distracted by other concerns. The end of Congressional Reconstruction limited the ways that many black and white southerners could act out their citizenship in the South. However, the Reconstruction Amendments—incorporated into the Constitution in part through black activism in the South—remained. New generations of black and white southerners would draw on Congressional Reconstruction for inspiration and the Reconstruction Amendments for constitutional authority in their struggles to claim full citizenship in the nation.

[1] Dan T. Carter, When the War Was Over: The Failure of Self-Reconstruction in the South, 1865−1867 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1985), 29−30.

[2] Andrew Johnson, Annual message to Congress, December 1867, quoted in Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863−1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 179−181.

[3] “An Address, To the Loyal Citizens and Congress of the United States of America,” printed in Liberty, and Equality before the Law. Proceedings of the Convention of the Colored People of VA., Held in the City of Alexandria, Aug. 2, 3, 4, 5, 1865 (Alexandria, VA: Cowing & Gillis, 1865), p. 21; “The Late Convention of Colored Men,” New York Times , August 13, 1865.

[4] Elna C. Green, Southern Strategies: Southern Women and the Woman Suffrage Question (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 6–7.

[5] Suzanne Lebsock, “Radical Reconstruction and the Property Rights of Southern Women,” Journal of Southern History 43, no. 2 (May 1977): 195–216.

Susanna Lee teaches the history of the American Civil War and Reconstruction at North Carolina State University. She earned her BA in history at the University of California, San Diego, and her MA and PhD in history from the University of Virginia. Her book, Claiming the Union (Cambridge University Press, 2014), focuses on southern citizenship after the Civil War. She is currently working on a book about the US–Dakota War.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- Recent changes

- Random page

- View source

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Create account

Understanding Reconstruction - A Historiography

As the United States entered the 20th century, Reconstruction slowly receded into popular memory. Historians began to debate its results. William Dunning and John W. Burgess led the first group to offer a coherent and structured argument. Along with their students at Columbia University, Dunning, Burgess, and their retinue created a historical school of thought known as the Dunning School. This interpretation of Reconstruction placed it firmly in the category of historical blunder.

Why did the Dunning School blame Radical Republicans and Freedmen for Reconstruction's failure?

According to the Dunning School, the defeated South accepted its fate and wished to rejoin the national culture. Thus, white Southerners sincerely hoped to offer the emancipated freedmen rights and protection along with equal opportunity. However, the bullying efforts of the Radical Republicans in Congress (inspired by their inherent disgust for the South) forced black suffrage, corruption, and economic dependence on the South. Carpetbaggers, scalawags, and uneducated freedmen plunged the South into depression and confusion until the white South banded together to reclaim southern culture and heritage.

While the Radical Republicans were the apparent villains, Dunning and his followers ascribed blame to President Johnson as well, saddling him with responsibility for Reconstruction’s failure. Freedmen were portrayed as animalistic or easily manipulated, therefore, lacking the kind of agency they indeed exhibited. While certainly influenced by the day's racial bias, the Dunning School at least formulated a coherent argument (although an incredibly inaccurate and distasteful one) that refused to fragment. This model of unity did prove somewhat valuable to historians following Dunning, even if their historical research opposed the Dunning School’s argument, “For all their faults, it is ironic that the best Dunning studies did, at least, attempt to synthesize the social, political, and economic aspects of the period.” In contrast, the Progressive historians that followed the Dunning School disagreed with some of its interpretations. President Johnson was not to blame, but rather, the Northern Radical Republicans were at fault. They cynically used freedmen's civil rights as a means to force capitalism and economic dependence on the South.

Why was W.E.B. Du Bois's reassessment of Reconstruction so important?

However, one work stands out from this period as a harbinger of what was to come. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote Black Reconstruction in America in 1935. Du Bois chastised historians for ignoring the central figures of Reconstruction, the freedmen. Moreover, Du Bois pointedly remarked on the prevailing racial bias of the historical inquiry up to that moment, “One fact and one alone explains the attitude of most recent writers toward Reconstruction; they cannot conceive of Negroes as men.” Du Bois’s indictment served as a precursor for the explosion of revisionist history of the 1960s, which would latch onto the argument of Du Bois and refocus the debate concerning Reconstruction to include the central figures of the freedmen.

The revisionists of the 1960s viewed Reconstruction's heroes to be the Southern freedmen and the Radical Republicans. Instead of going too far, Reconstruction failed to be radical enough. According to revisionists, Reconstruction was tragic not because it went too far and handcuffed white southerners; it was tragic because it was unable to securely secure the rights of freedmen and failed to restructure Southern society through land reform and similar measures. Following on the heels of the Revisionist School were the Post-Revisionists who viewed Reconstruction as overly conservative. This conservatism failed to achieve any lasting influence; thus, once Reconstruction ended, the South returned to its old social and economic structures.

What is the Modern Interpretation of Reconstruction?

So, where has that left historians today? How do more recent historians interpret Reconstruction? Several leading historians (James McPherson, Eric Foner, Emory Thomas) have labeled either the Civil War or Reconstruction as a second American revolution. Eric Foner’s work Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution openly claims Reconstruction to be a break from traditional systems (social, political, economic) prevailing in the South.

In contrast, Emory Thomas’s The Confederacy as a Revolutionary Experience argues the South first underwent a “conservative revolution” in breaking away from the Union since it broke from the North not to redefine itself but to maintain the status quo of the South. Ironically, according to Thomas, this first “external” revolution was subsumed by a more radical “internal” revolution during the Civil War as the South attempted to urbanize, industrialize and modernize to compete with the North. Thus, whether consciously or not, the Confederacy's leaders looked to recreate the South in a way that mirrored the North in several ways. However, this brief example illustrates the differences among historians and the current scholarship on the Civil War and Reconstruction. Perhaps, the best place to start might be with conditions between the North and South before the outbreak of war in 1861.

James McPherson provides a convincing account of the growing differences between the North and South on the eve of the war. McPherson, author of Battle Cry for Freedom (considered in some circles as the preeminent account of the Civil War), is frequently acknowledged as a leading if not the leading historian in Civil War studies today. In an essay for Major Problems in the Civil War and Reconstruction entitled, “The Differences between the Antebellum North and South,” McPherson argues that the South had not changed, but the North had. According to McPherson, the Southern states had remained loyal to the Jeffersonian interpretation of republicanism. Instead of investing in manufacturing and industry, they reinvested in agrarian pursuits. Southern culture emphasized traditional values, patronage, and ties of kinship.

Moreover, low Southern literacy rates and its labor-intensive economy were not unique. Thus, the “folk culture” of the South valued tradition and stability. Education was available to only the upper classes, who often sent children to elite schools. Simultaneously, political dissent was not popular since the political system rested on the foundation of patronage. In contrast, the North modernized through industrialization. Manufacturing and industry overtook the agrarian pursuits of Northern farmers. Education, unlike in the South, occupied a high position in society. Many Northerners saw education as a means of social mobility. More importantly, the North reinterpreted its ideas concerning republicanism. Accordingly, Northerners increasingly claimed to identify with egalitarian, free-market capitalism, which could only be maintained through a strong central government.

Northern republicanism was opposed to the Southern belief in republicanism emphasizing limited government and property rights, not to mention Southern anti-manufacturing sensibilities. Additionally, the more capital intensive economy of the North relied on wage labor and immigration. Two economic and social variables absent from the South. The rise of wage labor placed wager earners in the North in opposition to the system of slavery in the South, and the rising population of the North (from immigration) increased tensions between the two regions. Along with these differences, the West of America was growing rapidly in the image of the North. Resulting from the influence and growth of railroads, trade relations were no longer centered on the North/South relationship but East to West.

Emory Thomas’s work, The Confederacy as a Revolutionary Experience , supports much of McPherson’s argument. Like McPherson, Thomas acknowledges the South’s political structure resting on the ideology of states’ rights, agrarianism, and slavery. Politically, the south valued stability over reform. Thus, dissent was not a valuable political commodity.

Moreover, the political system held a foundation based on the patronage of the planter class. According to Thomas, the South’s initial break from the Union was inspired by the hope that the South might preserve its traditions and institutions. Led by radical “fire-eaters,” Southern politicians incited animosity between the North and South, “They made a ‘conservative revolution’ to preserve the antebellum status quo, but they made a revolution just the same. The ‘fire-eaters’ employed classic revolutionary tactics in their agitation for secession. And the Confederates were no fewer rebels than their grandfathers had been in 1776”.

However, this initial ‘conservative revolution’ inspired by radicals was overtaken by the moderates of the political south who recognized the need for change. If the Confederacy were to survive economically, politically, and socially, they would mount their internal revolution. Peter Kolchin’s work American Slavery 1619-1877 upholds much of McPherson’s and Thomas’ arguments concerning the South’s increasingly entrenched society. Kolchin’s work attempts to synthesize the prevailing studies of the day concerning slavery in America. Divided into three sections (colonial America and the American Revolution, antebellum South, and Civil War and Reconstruction)

Kolchin weaves historians' arguments past and present into a coherent work that examines several aspects of slavery. Concerning politics and reform, Kolchin notes, “The ‘perfectionist spirit’ that undergirded so much of the Northern reform effort in antebellum years, the drive continues to improve both social organization and the very human character itself, was largely absent in the South."

Moreover, politically, Kolchin remarks on the non-democratic nature of the South, “antebellum Southern sociopolitical thought harbored profoundly anti-democratic currents … More common than outright attacks on democracy were denunciations of fanatical reformism and appealed to conservatism, order, and tradition.” Also, the access to education among Southerners was limited at best, “Advocates of public education, for example, made little headway in their drive to persuade Southern state legislatures to emulate their northern counterparts and establish statewide public schooling … it was only after the Civil War that public education became widely available in the South.”

How did the Civil War Change the South's Social Structure?

In general, Thomas points out three areas of change political, economic, and social. The economic reform was extreme. As the Civil War commenced, the south had neither a large industrial complex nor many large urban areas (New Orleans stands as the lone exception). Jefferson Davis and others saw the need for increased industry and urbanization, “A nation of farmers knew the frustration of going hungry, but Southern industry made great strides. And Southern cities swelled in size and importance. Cotton, once king, became a pawn in the Confederate South. The emphasis on manufacturing and urbanization came too little, too late. But compared to the antebellum South, the Confederate South underwent nothing short of an economic revolution.”

Charles Dew’s work, Bond of Iron supports this viewpoint. Dew’s work documents both slave and master's experience at an industrial metalworking forge in Virginia known as Buffalo Forge. Repeatedly, throughout the work, the southern industry is portrayed as anemic at best. When the Civil War unfolds, Buffalo Forge becomes a few industrial sources of iron within the South. To obtain maximum profit, William Weaver, the forges’ owner, used this scarcity to increase the iron prices. Ironically though, Dew’s work points out the difficulties in industrializing through slave labor. Slavery failed to encourage innovation. Rather stability was seen as the optimum end.

Thus, once Weaver had assembled some 70 slaves, he no longer looked to improve industrial efficiency or examine technological advancements. “After he acquired and trained a group of skilled slave artisans in the 1820s and 1830s and had his ironworks functioning successfully, Weaver displayed little interest in trying to improve the technology of ironmaking at Buffalo Forge … The emphasis was on stability, not innovation. Slavery, in short, seems to have exerted a profoundly conservative influence on the manufacturing process at Buffalo Forge, and one suspects that similar circumstances prevailed at industrial establishments throughout the slave South.” Thus, Dew’s assertion would render the Confederacy’s attempt to industrialize increasingly tricky since the Southern labor system was not conducive to optimum industrial efficiency. Additionally, the Confederacy’s attempt to industrialize, urbanize, and in general, command the Southern economy contrasts sharply with its belief in states’ rights federal authority. Through such management of the economy, the Confederate leaders were contradicting themselves, yet the war called for such measures.

According to Thomas, such reorganization did not limit itself to the economic field. Southern women were no longer confined to the home, “Southern women climbed down from their pedestals and became refugees, went to work in factories, or assumed the responsibility for managing farms.” This hardly seems to be a radical premise since this cycle repeats itself nationally during both World Wars of the 20th century.

Besides, class consciousness began to form in the minds of the “proletariat” “Under the strain of wartime some “un Southern” rents appeared in the fabric of Southern society. The very process of renting what had been harmonious—mass meetings, riots, resistance to Confederate law and order—was the most visible manifestation of the social unsettlement within the Confederate South. Whether caused by heightened class awareness, disaffection with the “cause,” or frustration with physical privation, domestic tumults bore witness to the social ferment which replaced antebellum stability.” Of course, Thomas is careful to couch this class consciousness with limits, “This is not to imply that the Confederate south seethed with labor unrest; it is rather to say that working men in the Confederacy asserted themselves to a degree unknown in the antebellum period.”

Regarding social mobility, the South was forced to embrace meritocracy, at least in the area of military matters. No doubt, at the war’s beginning, the planter class dominated the military. However, as Thomas points out, “Before the war entered its second year, martial merit had challenged planter pedigree in the Confederate command structure. And combat provided ample opportunity for Southerners of all backgrounds to earn, confirm, or forfeit their spurs.” Again, Thomas limits his language, noting that martial merit “challenged” the aristocratic system rather than replacing it. The planter class still held a powerful position, “Still, the Confederate army was at the same time an agency of both democracy and aristocracy. Members of the planter class often won the elections to company commands.” Thus, the reader is left wondering what is meant by revolution since Thomas seems to be saying that the South revolutionizes during the war but then retreats from its revolution once the war comes to its conclusion.