Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum communications.

(1914-2000)

Who Was Hedy Lamarr?

Hedy Lamarr was an actress during MGM's "Golden Age." She starred in such films as Tortilla Flat, Lady of the Tropics, Boom Town and Samson and Delilah , with the likes of Clark Gable and Spencer Tracey. Lamarr was also a scientist, co-inventing an early technique for spread spectrum communications — the key to many wireless communications of our present day. A recluse later in life, Lamarr died in her Florida home in 2000.

Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1914, in Vienna, Austria. Discovered by an Austrian film director as a teenager, she gained international notice in 1933, with her role in the sexually charged Czech film Ecstasy . After her unhappy marriage ended with Fritz Mandl, a wealthy Austrian munitions manufacturer who sold arms to the Nazis, she fled to the United States and signed a contract with the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio in Hollywood under the name Hedy Lamarr. Upon the release of her first American film, Algiers , co-starring Charles Boyer, Lamarr became an immediate box-office sensation.

'Secret Communications System'

In 1942, during the heyday of her career, Lamarr earned recognition in a field quite different from entertainment. She and her friend, the composer George Antheil, received a patent for an idea of a radio signaling device, or "Secret Communications System," which was a means of changing radio frequencies to keep enemies from decoding messages. Originally designed to defeat the German Nazis, the system became an important step in the development of technology to maintain the security of both military communications and cellular phones.

Lamarr wasn't instantly recognized for her communications invention since its wide-ranging impact wasn't understood until decades later. However, in 1997, Lamarr and Antheil were honored with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) Pioneer Award, and that same year Lamarr became the first female to receive the BULBIE™ Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award, considered the "Oscars" of inventing.

Later Career

Lamarr's film career began to decline in the 1950s; her last film was 1958's The Female Animal , with Jane Powell. In 1966, she published a steamy best-selling autobiography, Ecstasy and Me , but later sued the publisher for what she saw as errors and distortions perpetrated by the book's ghostwriter. She was arrested twice for shoplifting, once in 1966 and once in 1991, but neither arrest resulted in a conviction.

Personal Life, Death and Legacy

Lamarr was married six times. She adopted a son, James, in 1939, during her second marriage to Gene Markey. She went on to have two biological children, Denise (b. 1945) and Anthony (b. 1947), with her third husband, actor John Loder, who also adopted James.

In 1953, Lamarr completed the naturalization process and became a U.S. citizen.

In her later years, Lamarr lived a reclusive life in Casselberry, a community just north of Orlando, Florida, where she died on January 19, 2000, at the age of 85.

Documentary and Pop Culture

In 2017, director Alexandra Dean shined a light on the Hollywood starlet/unlikely inventor with a new documentary, Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story . Along with delving into her pioneering technological work, the documentary explores other examples in which Lamarr proved to be far more than just a pretty face, as well as her struggles with crippling drug addiction.

A dramatized version of Lamarr featured in a March 2018 episode of the TV series Timeless , which centered on her efforts to help the time-traveling team recover a stolen workprint of the 1941 classic Citizen Kane .

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Hedy Lamarr

- Birth Year: 1914

- Birth date: November 9, 1914

- Birth City: Vienna

- Birth Country: Austria

- Best Known For: Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum communications.

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Hedy Lamarr was arrested twice for shoplifting, in 1966 and 1991, though neither arrest resulted in a conviction.

- Death Year: 2000

- Death date: January 19, 2000

- Death State: Florida

- Death City: Casselberry

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Hedy Lamarr Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/actors/hedy-lamarr

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 19, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Famous Actors

Timothée Chalamet

Anya Taylor-Joy

Cillian Murphy

Olivia Munn

Cillian Murphy & Sterling K. Brown Oscars Grooming

Ryan Gosling’s Oscars Sunglasses

Ryan Gosling

Robert Downey Jr.

Get to Know Oscar Winner Da'Vine Joy Randolph

Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian-American actress and inventor who pioneered the technology that would one day form the basis for today’s WiFi, GPS, and Bluetooth communication systems. As a natural beauty seen widely on the big screen in films like Samson and Delilah and White Cargo , society has long ignored her inventive genius.

Lamarr was originally Hedwig Eva Kiesler, born in Vienna, Austria on November 9 th , 1914 into a well-to-do Jewish family. An only child, Lamarr received a great deal of attention from her father, a bank director and curious man, who inspired her to look at the world with open eyes. He would often take her for long walks where he would discuss the inner-workings of different machines, like the printing press or street cars. These conversations guided Lamarr’s thinking and at only 5 years of age, she could be found taking apart and reassembling her music box to understand how the machine operated. Meanwhile, Lamarr’s mother was a concert pianist and introduced her to the arts, placing her in both ballet and piano lessons from a young age.

Lamarr’s brilliant mind was ignored, and her beauty took center stage when she was discovered by director Max Reinhardt at age 16. She studied acting with Reinhardt in Berlin and was in her first small film role by 1930, in a German film called Geld auf der Stra βe (“Money on the Street”). However, it wasn’t until 1932 that Lamarr gained name recognition as an actress for her role in the controversial film, Ecstasy .

Austrian munitions dealer, Fritz Mandl, became one of Lamarr’s adoring fans when he saw her in the play Sissy . Lamarr and Mandl married in 1933 but it was short-lived. She once said, “I knew very soon that I could never be an actress while I was his wife … He was the absolute monarch in his marriage … I was like a doll. I was like a thing, some object of art which had to be guarded—and imprisoned—having no mind, no life of its own.” She was incredibly unhappy, as she was forced to play host and smile on demand amongst Mandl’s friends and scandalous business partners, some of whom were associated with the Nazi party. She escaped from Mandl’s grasp in 1937 by fleeing to London but took with her the knowledge gained from dinner-table conversation over wartime weaponry.

While in London, Lamarr’s luck took a turn when she was introduced to Louis B. Mayer, of the famed MGM Studios. With this meeting, she secured her ticket to Hollywood where she mystified American audiences with her grace, beauty, and accent. In Hollywood, Lamarr was introduced to a variety of quirky real-life characters, such as businessman and pilot Howard Hughes.

Lamarr dated Hughes but was most notably interested with his desire for innovation. Her scientific mind had been bottled-up by Hollywood but Hughes helped to fuel the innovator in Lamarr, giving her a small set of equipment to use in her trailer on set. While she had an inventing table set up in her house, the small set allowed Lamarr to work on inventions between takes. Hughes took her to his airplane factories, showed her how the planes were built, and introduced her to the scientists behind process. Lamarr was inspired to innovate as Hughes wanted to create faster planes that could be sold to the US military. She bought a book of fish and a book of birds and looked at the fastest of each kind. She combined the fins of the fastest fish and the wings of the fastest bird to sketch a new wing design for Hughes’ planes. Upon showing the design to Hughes, he said to Lamarr, “You’re a genius.”

Lamarr was indeed a genius as the gears in her inventive mind continued to turn. She once said, “Improving things comes naturally to me.” She went on to create an upgraded stoplight and a tablet that dissolved in water to make a soda similar to Coca-Cola. However, her most significant invention was engineered as the United States geared up to enter World War II.

In 1940 Lamarr met George Antheil at a dinner party. Antheil was another quirky yet clever force to be reckoned with. Known for his writing, film scores, and experimental music compositions, he shared the same inventive spirit as Lamarr. She and Antheil talked about a variety of topics but of their greatest concerns was the looming war. Antheil recalled, “Hedy said that she did not feel very comfortable, sitting there in Hollywood and making lots of money when things were in such a state.” After her marriage to Mandl, she had knowledge on munitions and various weaponry that would prove beneficial. And so, Lamarr and Antheil began to tinker with ideas to combat the axis powers.

The two came up with an extraordinary new communication system used with the intention of guiding torpedoes to their targets in war. The system involved the use of “frequency hopping” amongst radio waves, with both transmitter and receiver hopping to new frequencies together. Doing so prevented the interception of the radio waves, thereby allowing the torpedo to find its intended target. After its creation, Lamarr and Antheil sought a patent and military support for the invention. While awarded U.S. Patent No. 2,292,387 in August of 1942, the Navy decided against the implementation of the new system. The rejection led Lamarr to instead support the war efforts with her celebrity by selling war bonds. Happy in her adopted country, she became an American citizen in April 1953.

Meanwhile, Lamarr’s patent expired before she ever saw a penny from it. While she continued to accumulate credits in films until 1958, her inventive genius was yet to be recognized by the public. It wasn’t until Lamarr’s later years that she received any awards for her invention. The Electronic Frontier Foundation jointly awarded Lamarr and Antheil with their Pioneer Award in 1997. Lamarr also became the first woman to receive the Invention Convention’s Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award. Although she died in 2000, Lamarr was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for the development of her frequency hopping technology in 2014. Such achievement has led Lamarr to be dubbed “the mother of Wi-Fi” and other wireless communications like GPS and Bluetooth.

Bedi, Joyce. “A Movie Star, Some Player Pianos, and Torpedoes.” Smithsonian National Museum of American History: Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, November 12, 2015.

Camhi, Leslie. “Hedy Lamarr’s Forgotten, Frustrated Career as a Wartime Inventor.” The New Yorker , December 3, 2017.

DeFore, John. “'Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story': Film Review | Tribeca 2017.” The Hollywood Reporter , April 25, 2017.

“Hedy Lamarr: Biography.” IMDb.com.

“Hedy Lamarr Biography.” Biography.com. April 2, 2014.

“'Most Beautiful Woman' By Day, Inventor By Night.” All Things Considered , NPR, November 22, 2011.

“Women in Science: How Hedy Lamarr Pioneered Modern Wi-Fi Technology.” TEDxUCLWomen. July 30, 2017.

Y.F.. “The incredible inventiveness of Hedy Lamarr.” The Economist, November 23, 2017.

APA: Cheslak, C. (2018, August 30). Hedy Lamarr. Retrieved from https://www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr

MLA: Cheslak, Colleen. “Hedy Lamarr.” Hedy Lamarr , National Women's History Museum, 30 Aug. 2018, www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr.

Chicago:Cheslak, Colleen. "Hedy Lamarr." Hedy Lamarr. August 30, 2018. https://www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr.

Rhodes, Richard. Hedy's Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World . New York: Doubleday, 2011.

Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story. Directed by Alexandra Dean. New York: Zeitgeist Films, November 24, 2017.

Related Biographies

Stacey Abrams

Abigail Smith Adams

Jane Addams

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Related background, mary church terrell , belva lockwood and the precedents she set for women’s rights, faith ringgold and her fabulous quilts, educational equality & title ix:.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Hollywood Star Hedy Lamarr Invented the Tech Behind WiFi

By: Dave Roos

Published: March 5, 2024

In the 1940s, few Hollywood actresses were more famous and more famously beautiful than Hedy Lamarr. Yet despite starring in dozens of films and gracing the cover of every Hollywood celebrity magazine, few people knew Hedy was also a gifted inventor. In fact, one of the technologies she co-invented laid a key foundation for future communication systems, including GPS, Bluetooth and WiFi.

“Hedy always felt that people didn't appreciate her for her intelligence—that her beauty got in the way,” says Richard Rhodes, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian who wrote a biography about Hedy.

After working 12- or 15-hour days at MGM Studios, Hedy would often skip the Hollywood parties or carousing with one of her many suitors and instead sit down at her “inventing table.”

“Hedy had a drafting table and a whole wall full of engineering books. It was a serious hobby,” says Rhodes, author of Hedy's Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World .

While not a trained engineer or mathematician, Hedy Lamarr was an ingenious problem-solver. Most of her inventions were practical solutions to everyday problems, like a tissue box attachment for depositing used tissues or a glow-in-the-dark dog collar.

It was during World War II , that she developed “frequency hopping,” an invention that’s now recognized as a fundamental technology for secure communications. She didn’t receive credit for the innovation until very late in life.

Hedy Lamarr's Childhood in Austria

Hedy Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Kiesler in Vienna, Austria in 1914. She was the only child of a wealthy secular Jewish family. From her father, a bank director, and her mother, a concert pianist, Hedy received a debutante’s education—ballet classes, piano lessons and equestrian training.

There were signs at a young age that Hedy had an engineer’s natural curiosity. On long walks through the bustling streets of Vienna, Hedy’s father would explain how the streetcars worked and how their electricity was generated at the power plant. At five years old, Hedy took apart a music box and reassembled it piece by piece.

“Hedy did not grow up with any technical education, but she did have this personal connection,” says Rhodes. “She loved her father dearly, so it’s easy to see how from that she might have developed an interest in the subject. And also it prepared her to be what she really was, a kind of amateur inventor.”

Hedy's Movie Debut as Teen

Even if Hedy had wanted to be a professional engineer or scientist, that career path wasn’t available to Viennese girls in the 1930s. Instead, teenage Hedy set her sights on the movie industry.

“At 16,” says Rhodes, “Hedy forged a note to her teachers in Vienna saying, ‘My daughter won’t be able to come to school today,’ so she could go down to the biggest movie studio in Europe and walk in the door and say, ‘Hi, I want to be a movie star.’”

Hedy started as a script girl, but quickly earned some walk-on parts. The Austrian director Max Reinhardt took Hedy to Berlin when she starred in a few forgettable films before landing a role at age 18 in a racy film called Ecstasy by the Czech director Gustav Machatý. The film was denounced by Pope Pious XI, banned from Germany and blocked by US Customs authorities for being “dangerously indecent.”

Reinhardt called Hedy “the most beautiful woman in Europe,” and even before Ecstasy , Hedy was turning heads in theater productions across Europe. It was during the Viennese run of a popular play called Sissy that Hedy caught the eye of a wealthy Austrian munitions baron named Fritz Mandl. Hedy and Mandl married in 1933, but the union was stifling from the start. Mandl forced his wife to accompany him as he struck deals with customers, including officials from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, including Mussolini himself.

“She would sit at dinner bored out of her mind with discussions of bombs and torpedoes, and yet she was also absorbing it,” says Rhodes. “Of course, nobody asked her any questions. She was supposed to be beautiful and silent. But I think it was through that experience that she developed her considerable knowledge about how torpedo guidance worked.”

In 1937, Hedy fled her unhappy marriage (Mandl was deeply paranoid that Hedy was cheating on him) and also fled Austria, a country aligned with Adolf Hitler’s anti-Jewish policies.

A New Country and a New Name

Hedy landed in London, where Louis B. Mayer of MGM Studios was actively buying up the contracts of Jewish actors who could no longer work safely in Europe. Hedy met with Mayer, but refused his lowball offer of $125 a week for an exclusive MGM contract. In a savvy move, Hedy booked passage to the United States on the luxury liner SS Normandie , the same ship on which Mayer was traveling home.

“She made a point of being seen on deck looking beautiful and playing tennis with some of the handsome guys on board,” says Rhodes. “By the time they got to New York, Hedy had cut a much better deal with Mayer”—$500 a week—“with the proviso that she’d learn how to speak English in six months.”

Mayer had another demand—she had to change her name. Hedwig Kiesler was too German-sounding. Mayer’s wife was a fan of 1920s actress Barbara La Marr (who died tragically at 29 years old), so Mayer decided that his new MGM actor would now be known as Hedy Lamarr.

Actress by Day, Inventor by Night

It didn’t take long for Hedy to emerge as a bright new star in Hollywood. Her breakout role was alongside Charles Boyer (another European transplant) in Algiers (1938). From there, the MGM machine put Hedy to work cranking out multiple feature films a year throughout the 1940s.

“Any girl can be glamorous,” Hedy once quipped. “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.”

As much as Hedy enjoyed her Hollywood stardom, her first love was still tinkering and problem-solving. She found a kindred spirit in Howard Hughes, the film producer and aeronautical engineer. When Hedy shared an idea for a dissolvable tablet that could turn a soldier’s canteen into a soft drink, Hughes lent her a few of his chemists.

But most of Hedy’s work was done at home at her engineering table where she’d sketch designs for creative solutions to practical problems. In addition to the tissue box attachment and the light-up dog collar, Hedy devised a special shower seat for the elderly that swiveled safely out of a bathtub.

“She was an inventor,” says Rhodes. “If you’ve ever been around real inventors, they’re often not people with a particularly deep education. They’re people who think about the world in a certain way. When they find something that doesn’t work right, instead of just swearing or whatever the rest of us do, they figure out how to fix it.”

Lamarr Takes on German U-Boats

In 1940, Hedy was distraught by the news coming out of Europe, where the Nazi war machine was steadily gaining territory and German U-boat submarines were wreaking havoc in the Atlantic. This was a far more difficult problem to fix, but Hedy was determined to do her part in the war effort.

The turning point came when Hedy met a man at a dinner party. George Antheil was an avante-garde music composer who lost his brother in the earliest days of the war. Antheil and Hedy were kindred spirits—two brilliant, if unconventional minds dead set on finding a way to defeat Hitler. But how?

That’s when Rhodes thinks Hedy leaned on the knowledge she picked up years earlier during those boring client dinners with her first husband in Vienna.

“She knew about torpedoes,” says Rhodes. “She knew there was a problem aiming torpedoes. If the British could take out German submarines with torpedoes launched from surface ships or airplanes, they might be able to prevent all of this slaughter that was going on.”

The answer was clearly some type of radio-controlled torpedo, but how would they stop the Germans from simply jamming the radio signal? Hedy and Antheil’s creative solution was inspired, Rhodes believes, by their mutual love of the piano.

Lamarr, Antheil Harness Music to Inspire Invention

During their late-night brainstorming sessions, Hedy and Antheil played a musical game. They’d sit down at the piano together, one person would start playing a popular song and the other would see how quickly they could recognize it and start playing along.

It was here, Rhodes thinks, that Hedy and Antheil first happened upon the idea of frequency hopping. If two musicians are playing the same music, they can hop around the keyboard together in perfect sync. However, if someone listening doesn’t know the song, they have no idea what keys will be pressed next. The “signal,” in other words, was hidden in the constantly changing frequencies.

How did this apply to radio-controlled torpedoes? The Germans could easily jam a single radio frequency, but not a constantly changing “symphony” of frequencies.

In his experimental musical compositions, Antheil had written songs for multiple synchronized player pianos. The pianos played in sync because they were fed the same piano rolls—a type of primitive, cut-out paper program—that controlled which keys were played and when. What if he and Hedy could invent a similar method for synchronizing communications between a torpedo and its controller on a nearby ship?

“All you need are two synchronized clocks that start a tape going at the same moment on the ship and inside the torpedo,” says Rhodes. “The signal between the ship and the torpedo would be continuous, even though it was traveling across a new frequency every split second. The effect for anyone trying to jam the signal is that they wouldn’t know where it was from one moment to the next, because it would ‘hopping’ all over the radio.”

It was Hedy who named their clever system “frequency hopping.”

Navy Rejects Invention

Hedy and Antheil developed their idea with the help of a wartime agency called the National Inventors’ Council , tasked with applying civilian inventions to the war effort. The Council connected Hedy and Antheil with a physicist from the California Institute of Technology who figured out the complex electronics to make it all work.

When their frequency hopping patent was finalized in 1942, Antheil pitched the idea to the U.S. Navy, which was less than receptive.

“What do you want to do, put a player piano in a torpedo? Get out of here!” is how Rhodes describes the Navy’s knee-jerk rejection. It was never given a chance.

Hedy and Antheil’s patent was locked in a safe and labeled “top secret” for the remainder of the war. The two entertainers went back to their day jobs, thinking that was the end of their inventing days. Little did they know that their patent would have a second life.

Frequency Hopping Tech Takes Off

In the 1950s, the electrical manufacturer Sylvania employed frequency hopping to build a secure system for communicating with submarines. And in the early 1960s, the technology was deployed on U.S. warships to prevent Soviet signal jamming during the Cuban Missile Crisis .

Antheil died in 1959, but Hedy lived on, unaware that her ingenious idea was about to take off in a big way.

When car phones first became popular in the 1970s, carriers used frequency hopping to enable hundreds of callers to share a limited spectrum of radio frequencies. The same technology was rolled out for the earliest cell phone networks.

By the 1990s, frequency hopping was so ubiquitous that it became the technology standard required by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for secure radio communications. That’s why Bluetooth, WiFi and other essential technologies are based, at their core, on an idea dreamed up by Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil.

“It’s a really deep and fundamental idea,” says Rhodes. “It has broad applications all over the place.”

Over time, Hedy’s Hollywood star fizzled and she retired to Florida, where she continued to tinker with new inventions, including a more “driver-friendly” type of traffic light. It wasn’t until Hedy was in her 80s that a group of engineers realized that the “Hedwig Kiesler Mackay” listed on the frequency hopping patent was none other than the Hollywood legend, Hedy Lamarr.

“Hedy didn’t want money, but she did want recognition,” says Rhodes, “and it really angered her that nobody gave her credit for this important invention. In the 1990s, she finally got an award for her contribution. And Hedy being Hedy, what did she say? ‘Well, it’s about time.’”

HISTORY Vault: Women's History

Stream acclaimed women's history documentaries in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Hedy Lamarr

- Born November 9 , 1914 · Vienna, Austria-Hungary [now Austria]

- Died January 19 , 2000 · Casselberry, Florida, USA (natural causes)

- Birth name Hedwig Maria Vera Kiesler

- Hollywood's Loveliest Legendary Lady

- Queen of Glamour

- Height 5′ 7″ (1.70 m)

- Hedy Lamarr, the woman many critics and fans alike regard as the most beautiful ever to appear in films, was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria. She was the daughter of Gertrud (Lichtwitz), from Budapest, and Emil Kiesler, a banker from Lemberg (now known as Lviv). Her parents were both from Jewish families. Hedwig had a calm childhood, but it was cinema that fascinated her. By the time she was a teenager, she decided to drop out of school and seek fame as an actress, and was a student of theater director Max Reinhardt in Berlin. Her first role was a bit part in the German film Geld auf der Straße (1930) (aka "Money on the Street") in 1930. She was attractive and talented enough to be in three more German productions in 1931, but it would be her fifth film that catapulted her to worldwide fame. In 1932 she appeared in a Czech film called Ekstase (US title: "Ecstasy") and had made the gutsy move to appear nude. It's the story of a young girl who is married to a gentleman much older than she, but she winds up falling in love with a young soldier. The film's nude scenes created a sensation all over the world. The scenes, very tame by today's standards, caused the film to be banned by the U.S. government at the time. Hedy soon married Fritz Mandl, a munitions manufacturer and a prominent Austrofascist. He attempted to buy up all the prints of "Ecstasy" he could lay his hands on (Italy's dictator, Benito Mussolini , had a copy but refused to sell it to Mandl), but to no avail (there are prints floating around the world today). The notoriety of the film brought Hollywood to her door. She was brought to the attention of MGM mogul Louis B. Mayer , who signed her to a contract (a notorious prude when it came to his studio's films, Mayer signed her against his better judgment, but the money he knew her notoriety would bring in to the studio overrode any moral concerns he may have had). However, he insisted she change her name and make good, wholesome films. Hedy starred in a series of exotic adventure epics. She made her American film debut as Gaby in Algiers (1938) . This was followed a year later by Lady of the Tropics (1939) . In 1942, she played the plum role of Tondelayo in the classic White Cargo (1942) . After World War II, her career began to decline, and MGM decided it would be in the interest of all concerned if her contract were not renewed. Unfortunately for Hedy, she turned down the leads in both Gaslight (1940) and Casablanca (1942) , both of which would have cemented her standing in the minds of the American public. In 1949, she starred as Delilah opposite Victor Mature 's Samson in Cecil B. DeMille 's epic Samson and Delilah (1949) . This proved to be Paramount Pictures' then most profitable movie to date, bringing in $12 million in rental from theaters. The film's success led to more parts, but it was not enough to ease her financial crunch. She made only six more films between 1949 and 1957, the last being The Female Animal (1958) . Hedy retired to Florida. She died there, in the city of Casselberry, on January 19, 2000. - IMDb Mini Biography By: Volker Boehm and BlueGreen

- Spouses Lewis William Boies Jr. (March 4, 1963 - June 21, 1965) (divorced) Willam Howard Lee (December 22, 1953 - April 22, 1960) (divorced) Teddy Stauffer (June 11, 1951 - March 18, 1952) (divorced) John Loder (May 27, 1943 - July 17, 1947) (divorced, 2 children) Gene Markey (March 4, 1939 - October 3, 1940) (divorced, 1 child) Fritz Mandl (August 10, 1933 - 1937) (divorced)

- Children James Lamarr Markey Denise Loder Anthony Loder

- Parents Emil Kiesler Gertrud Kiesler

- Natural brunette hair

- Fair skin and blue eyes

- Shapely figure

- Seductive deep voice

- Often portrayed femme fatales renowned for their beauty

- Inspired by an early Philco wireless radio remote and player piano rolls, she worked with composer George Antheil (who created a symphony played by eight synchronized player pianos) she invented a frequency-hopping system for remotely controlling torpedoes during World War II. (The frequency hopping concept appeared as early as 1903 in a U.S. Patent by Nikola Tesla). The invention was examined superficially and filed away. At the time, Allied torpedoes, as well as those of the Axis powers, were unguided. Input for depth, speed, and direction were made moments before launch but once leaving the submarine the torpedo received no further input. In 1959 it was developed for controlling drones that would later be used in Viet Nam. Frequency hopping radio became a Navy standard by 1960. Due to the expiration of the patent and Lamarr's unawareness of time limits for filing claims, she was never compensated. Her invention is used today for WiFi, Bluetooth, and even top secret military defense satellites. While the current estimate of the value of the invention is approximately $30 billion, during her final years she was getting by on SAG and social security checks totaling only $300 a month.

- Was the inspiration for the DC Comics antiheroine and Batman's love interest, Catwoman.

- The mansion used in The Sound of Music (1965) belonged to her at the time.

- Sued Mel Brooks for mocking her name in his film Blazing Saddles (1974) by naming a character "Hedley Lamarr". They settled out of court.

- Was co-inventor (with composer George Antheil ) of the earliest known form of the telecommunications method known as "frequency hopping", which used a piano roll to change between 88 frequencies and was intended to make radio-guided torpedoes harder for enemies to detect or to jam. The method received U.S. patent number 2,292,387 on August 11, 1942, under the name "Secret Communications System". The earliest U.S. Patent that alluded to frequency hopping was by Nikola Tesla in 1903 (US patent 725,605). Frequency hopping is now widely used in cellular phones and other modern technology. However, neither she nor Antheil profited from this fact, because their patents were allowed to expire decades before the modern wireless boom. In fact, at the time the patent was filed, the intended purpose (guidance of torpedoes) was of little no value as neither Allied or Axis torpedoes had any form of active guidance. All torpedoes of the era were fire-and-forget. It would not be until after 1959 that the USN would have torpedoes capable of using freq-hopping (ie torpedoes with radio control). She received an award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation in 1997 for her pioneering work in spread-spectrum technology.

- I must quit marrying men who feel inferior to me. Somewhere, there must be a man who could be my husband and not feel inferior. I need a superior inferior man.

- My problem is, I'm a hell of a nice dame, The most horrible whores are famous. I did what I did for love. The others did it for money.

- If you use your imagination, you can look at any actress and see her nude, I hope to make you use your imagination

- Any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.

- [1960s] It would be wrong of me to say so, but in this country [USA] money is more important than love. Most people here betray you and that's why there is so much chaos. I want to get away from here. I am homesick for Vienna . . . because my home is Vienna and Austria, not America... never!

- A Lady Without Passport (1950) - $90,000

- Copper Canyon (1950) - $108,000

- Samson and Delilah (1950) - $100,000

- Her Highness and the Bellboy (1945) - $7,500 /week

- Geld auf der Straße (1930) - $5 /day

Contribute to this page

- Learn more about contributing

More from this person

- View agent, publicist, legal and company contact details on IMDbPro

More to explore

Recently viewed

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

- Newsletters

The Beautiful Brilliance of Hedy Lamarr

By Hadley Hall Meares

All featured products are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, Vanity Fair may earn an affiliate commission.

“I’ve never been satisfied. I’ve no sooner done one thing than I am seething inside me to do another thing,” Golden Age screen siren Hedy Lamarr once said .

And do things Lamarr did. The stunning star of classics including Algiers and Samson and Delilah was much more than the label she was given, “the most beautiful woman in the world.” Married six times, she was an actress, pioneering female producer, ski-resort impresario , painter, art collector, and groundbreaking inventor, whose important innovations are meticulously cataloged in Pulitzer Prize winner Richard Rhodes ’s 2012 book, Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World .

However, it was another book that would alter the course of Lamarr’s life. Ecstasy and Me: My Life as a Woman , ghostwritten by Cy Rice and Leo Guild (who was also ghostwriter of the notorious Barbara Payton tell-all I Am Not Ashamed ), was released in 1966 and immediately became a best seller.

Based on 50 hours of taped conversations with the eccentric, vulnerable Lamarr, Ecstasy and Me is a grotesquely fascinating chronicle of the way women have been sexualized, minimized, and trivialized throughout history. Though it’s classified as an autobiography, the book starts with a male psychologist proclaiming that the sex-positive Lamarr is “blissfully unaffected by moral standards that our contemporary culture declares acceptable,” and goes on nauseatingly from there.

Lurid, amorous encounters right out of a Roger Corman sexploitation film and sexual trauma disguised as titillation are the main foci of this supposed autobiography, though sometimes it breaks, bizarrely, for transcripts of conversations Lamarr recorded with a psychiatrist. Sprinkled in are standard Hollywood gossip—sometimes catty, occasionally kind portraits of everyone from Judy Garland and Clark Gable to Ingrid Bergman—and inane pronouncements such as “Why Americans suspect bidets, I’ll never know. They are the last word in cleanliness.”

In 2010’s definitive Beautiful: The Life of Hedy Lamarr , biographer Stephen Michael Shearer writes that those close to Lamarr believed some of the nonsexual stories in Ecstasy and Me were accurate, with Lamarr’s own voice occasionally breaking through the sensationalist muddle. But they also felt the outlandish sexual stories were complete lies. The reader gets the sense that while Lamarr may have said the things she’s quoted as saying, statements made while she might have been high shouldn’t have been taken at face value. It’s no wonder Lamarr would sue unsuccessfully in an attempt to stop the publication of Ecstasy and Me , which she labeled “fictional, false, vulgar, scandalous, libelous, and obscene.” As she told Merv Griffin in 1969, “That’s not my book.”

Lamarr was born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna, Austria, in 1914, to an assimilated Jewish family . In Hedy’s Folly , Rhodes paints a captivating picture of the artistic, intellectual Vienna of Lamarr’s youth, exploring the forces that would shape her (and making the reader wish they could step back in time). While Lamarr’s cultured mother worried that her extraordinarily beautiful, bright, and headstrong only child would grow spoiled, her father, Emil, a prominent banker, coddled and cultivated his precious daughter. “He made me understand that I must make my own decisions, mold my own character, think my own thoughts,” Lamarr later recalled, per Rhodes.

Ecstasy and Me describes Lamarr’s adolescence as a tumultuous time, filled with the trauma of attempted rape, lurid sexual exploits at boarding school, and an affair with her friend’s father that produced “uncountable” orgasms. It fails to mention, though, that when she was a teenager, she was already learning mechanics, and had become a fearless self-promoter and a protégé of theatrical impresario Max Reinhardt.

Buy Ecstasy and Me on Amazon .

At the age of 17, Lamarr was cast in the film that catapulted her to international stardom and infamy: Ecstasy , the project that gave her purported autobiography its title. The movie includes a scene in which Lamarr (who was unaccompanied by her parents during shooting) swimming nude and simulating an orgasm—a first in film history. Some of the only affecting passages in Ecstasy and Me come when Lamarr describes the exploitation she suffered at the hands of powerful men while making films like these.

By Eve Batey

By Lawrence Grobel

By Julie Miller

Most disturbing are her allegations that Ecstasy director Gustav Machatý resorted to cruel methods to get the teenager’s reactive face during her love scene with costar Aribert Mog:

Aribert took over me, and the scene began again. Aribert slipped down out of range on one side. From down out of range on the other side, the director jabbed that pin into my buttocks “a little” and I reacted…. I remember one shot when the close-up camera caught my face in a distortion of real agony…and the director yelled happily “Ya, goot!”

In 1933, Lamarr married munitions manufacturer Fritz Mandl. “He had the most amazing brain…. There was nothing he did not know…. Ask him a formula in chemistry and he would give it to you,” she said, per Rhodes.

The union was an unhappy one, though Ecstasy and Me conveniently leaves out crucial details about her relationship to make Lamarr appear blameless. That book describes her marriage as a perverse fairy tale. The much older Mandl did not allow her to act; Lamarr soon found that life with him was little more than a prison, a “gilded cage.”

All of Lamarr’s biographers agree that Mandl was insanely controlling and jealous of his wife’s beauty and infamy. Incensed and embarrassed by Lamarr’s nudity in Ecstasy , he spent a large sum of money in an attempt to buy up all existing copies of the film (he failed).

But Lamarr was not entirely as hopeless as she is portrayed in Ecstasy and Me . Shearer writes in Beautiful that while married, Lamarr had an affair with her husband’s best friend, Prince Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg. And according to Rhodes, she was far from the stereotypical trophy wife. Lamarr listened carefully to talk of the German military’s technological innovations as she presided over grand dinners in Starhemberg’s home. One of the most intriguing aspects of Hedy’s Folly is the detailed insight it gives into the big-business world of munitions and armaments, and how it may have influenced Lamarr’s future inventions.

If both Ecstasy and Me and Hedy’s Folly sometimes read more like spy thrillers than nonfiction, it is because what came next for Lamarr was incontestably dramatic. Always a fabulist, Lamarr would tell numerous stories of her attempts to flee Mandl. In Ecstasy and Me, the chosen version is particularly outrageous: that Lamarr hired a maid who looked like her so that she could steal the maid’s identity and sneak out of the house using the servants’ entrance. Lamarr’s son would corroborate this unbelievable story in the excellent, nuanced 2017 documentary Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story .

Whatever the truth, though, she did escape—first to Paris, then to London. By 1937, Lamarr was headed to Hollywood, with a contract from MGM’s Louis B. Mayer. Ecstasy and Me paints the exec as a phony, lecherous ham whom Lamarr constantly outsmarts. One can only hope that is true.

By 1940, the newly christened Hedy Lamarr was a bona fide movie star. Disdainful of the Hollywood social whirl, she preferred painting or swimming with her good friend Ann Sothern. “Any girl can be glamorous,” she later said . “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.”

Ecstasy and Me presents these years as times of endless lovemaking and rehashes tired tropes about movie making. But according to Rhodes, Lamarr’s real passions were her inventions. She spent countless nights tinkering in a corner of her Benedict Canyon mansion, which contained drafting boards and gadgets galore. “My mother was very bright minded,” her son Anthony Loder later told the L.A. Times . “She always had solutions. Anytime someone complained about anything, boom, her mind came up with a solution.”

According to that same paper, while dating Howard Hughes, Lamarr worked on plans to streamline his airplanes. She also invented a bouillon cube that produced cola when dropped in plain water. But her real contribution to science arose out of a chance meeting with the flamboyant avant-garde composer and amateur inventor George Antheil (who is heavily profiled in Hedy’s Folly —so much that it makes the reader wish Rhodes would just get back to Lamarr’s story) at the home of movie star Janet Gaynor.

Antheil would later say that Lamarr was initially interested in his claim that he could make her breasts bigger (bosoms are a preoccupation in Ecstasy and Me as well). But the two soon turned their focus to helping the war effort, and began work on an invention based on Lamarr’s theory of “frequency hopping,” which could stop radio systems from being jammed by the enemy, aiding in torpedo launches. In August 1942, the government issued its “secret communication system,” U.S. patent No. 2,292,387. This system would later be used by the U.S. Navy and would be highly influential.

If Hedy’s Folly is sometimes bogged down by scientific and mechanical details, it is at least an overdue overcorrection. Books like Rhodes’s are a necessary revaluation of historical women’s roles as thinkers and game changers, contrasting the narrative that their lives were guided only by romance, physical appearance, and children. It is almost impossible to believe that in 50 hours of interviews, Lamarr never mentioned inventing—but in Ecstasy and Me , her passion is not mentioned once.

So why did this curious, ingenious woman agree to participate in Ecstasy and Me in the first place? By the mid-1960s, Lamarr’s movie stardom and six tumultuous marriages were firmly in the past. She claimed to be broke, and according to the documentary Bombshell, was addicted to methamphetamines ( she was a patient of Max Jacobson, the notorious “ Dr. Feelgood ”). In 1966, Lamarr was arrested at the May Company department store in Los Angeles for allegedly stealing items including two strings of beads, a lipstick brush, and an eye makeup brush. She was later acquitted .

According to Beautiful: The Life of Hedy Lamarr , Lamarr received a total of $80,000 for Ecstasy and Me . She signed off on the manuscript without reading it, legally paving the way for its publication.

It was a grave error. The book’s torrid passages are written like classic pornography; they include tales of orgies on sets with starlets and assistant directors, sadomasochism, and a strange story of one lover who had sex with a doll that he had made to look like Lamarr while she watched in horror.

It also includes a few interesting passages discussing her role as a groundbreaking film producer, and defensive yet amusing retellings of her bizarre behavior during her divorce from millionare Texas oilman W. Howard Lee (she sent her stand-in to testify for her in court). But the sex is was what stuck.

Once Lamarr actually bothered to read Ecstasy and Me , she knew her career was done. “I was there when she read Ecstasy and Me for the first time,” TCM’s Robert Osborne recalls in Beautiful . “She was shocked by it. But that was the foolish side of her. She wanted money. They simply made up passages in that book and she allowed them to…. It was part of her capriciousness, giving away parts of her life for a book and not worrying about the consequences.”

Although presiding judge Ralph H. Nutter believed Ecstasy and Me was “filthy, nauseating, and revolting,” he ruled against Lamarr, and the book was published anyway. “The damage it did to Hedy’s career and reputation was irreversible,” Shearer writes in Beautiful . Reading it, one instantly understands why. The cool Austrian film goddess had been knocked off her pedestal, presenting herself (intentionally or not) as a self-professed “nymphomaniac” and an irrational, self-obsessed has-been who bemoans the curse of her great beauty one too many times.

Lamarr eventually moved to Florida. Unable to cope with aging, she became a recluse, obsessed with plastic surgery and pushing her doctors to innovate new techniques in the field. “Hedy retreated from the gazes of those who didn’t look deeper. She…filled her days with activities (and lawsuits) and, with the humor still intact, tolerated the rest of us,” Osborne writes in the forward to Beautiful .

Lamarr rarely saw her children or friends, but instead talked to them on the telephone for hours every day. She also claimed she was writing her autobiography, seemingly trying to erase the pain and embarrassment of Ecstasy and Me from her memory.

As Lamarr hid away, her wartime work in frequency hopping was becoming extremely important. It paved the way for Wi-Fi, cellular technology, and modern satellite systems. Lamarr was aware of these uses, and bitter that her work had not been recognized—nor had she received a cent for her contributions. “I can’t understand why there’s no acknowledgment when it’s used all over the world,” she said in an influential 1990 Forbes interview , which slowly began to wake the world up to her accomplishments.

In 1997, three years before her death, Lamarr was finally honored with the prestigious Pioneer Award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. When she heard of the award, she said to her son simply this: “It’s about time.”

Perhaps it is fitting that it has been so hard to tell Lamarr’s entire story until recently; an extraordinarily beautiful, troubled, brilliant, sexually liberated woman has long been too much for patriarchal society to handle. This is something Lamarr seemed to understand. In a 1969 interview, she explained it to a befuddled Merv Griffin: “I’m a very simple, complicated person.”

All products featured on Vanity Fair are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

— “Who the Fuck Cares About Adam McKay?” (We Do, and With Good Reason) — The 10 Best Movies of 2021 — The Goldbergs Actor Jeff Garlin Responds to Talk of Misbehavior on Set — We Still Love 30 Rock , but Its Foundation Is Shaky — Our TV Critic’s Favorite Shows of the Year — Mel Brooks Went Too Far —But Only Once — Lady Gaga’s House of Gucci Character Is Even Wilder in Real Life — From the Archive: Inside the Crazy Ride of Producing The Producers — Sign up for the “HWD Daily” newsletter for must-read industry and awards coverage—plus a special weekly edition of “Awards Insider.”

Hadley Hall Meares

By Rosemary Counter

By Joy Press

By Richard Lawson

By Kase Wickman

By Hillary Busis

By David Canfield

Hedy Lamarr

The Official Website of Hedy Lamarr

The Most Beautiful Woman in Film

Often called “The Most Beautiful Woman in Film,” Hedy Lamarr’s beauty and screen presence made her one of the most popular actresses of her day.

She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1914 in Vienna, Austria. At 17 years old, Hedy starred in her first film, a German project called Geld auf der Strase . Hedy continued her film career by working on both German and Czechoslavakian productions. The 1932 German film Exstase brought her to the attention of Hollywood producers, and she soon signed a contract with MGM.

Once in Hollywood, she officially changed her name to Hedy Lamarr and starred in her first Hollywood film, Algiers (1938), opposite Charles Boyer. She continued to land parts opposite the most popular and talented actors of the day, including Spencer Tracy, Clark Gable, and Jimmy Stewart. Some of her films include an adaptation of John Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat (1942), White Cargo (1942), Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949), and The Female Animal (1957).

Beyond the Glitz & Glamour of Hollywood

As if being a beautiful, talented actress was not enough, Hedy was also a gifted mathematician, scientist, and innovator. Alongside the famed composer George Antheil, Lamarr patented the "Secret Communication System" during World War II. Her idea - now referred to as "frequency hopping" - pertained to a way for radio guidance transmitters and torpedo's receivers to jump simultaneously from frequency to frequency. The Hollywood star's invention sought to put an end to enemies' interception of classified military strategies, signals, and messages. While the technology of the time prevented the feasibility of "frequency hopping" at first, the advent of the transistor and its later downsizing propelled Lamarr's idea far in both the military and the cell phone industry.

Overall, the Hollywood actress introduced the technology that would serve as the foundation of modern-day WiFi, GPS, and Bluetooth communication systems. Her creation of "frequency hopping," which holds an estimated worth of $30 billion, led her to receive the Pioneer Award of the Electronic Frontier Foundation as well as the Invention Convention's Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award.

Lamarr's impressive technological achievement combined with her acting talent and star quality makes "The Most Beautiful Woman in Film" one of the most accomplished and intelligent women in not only Hollywood but also STEM.

Site Navigation

Hedy Lamarr: Golden Age Film Star—and Important Inventor

Actor Hedy Lamarr (1914–2000) had a fascinating life, including her scandalous debut in the Czech film Ecstasy, discovery (and renaming) by Louis B. Mayer, persona as the most glamorous woman of Hollywood's Golden Age, and relative obscurity in her later years.

But far beyond the Hollywood image, Lamarr was an inventor.

She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria. Her father was the director of a bank and her Hungarian mother was a concert pianist.

During a small dinner party in 1940, Lamarr met a kindred inventive spirit in George Antheil. The Trenton, New Jersey, native was known for his writing, his film scores—especially his avant-garde music compositions—but he was also an inventor.

Lamarr wanted to aid the Allied forces during World War II. She explored potential military applications for radio technology. She theorized that varying radio frequencies at irregular intervals would prevent interception or jamming of transmissions, thereby creating an innovative communication system.

Lamarr shared her concept for using “frequency hopping” with the U.S. Navy and codeveloped a patent with Antheil 1941. Today, her innovation helped make possible a wide range of wireless communications technologies, including Wi-Fi, GPS, and Bluetooth.

This image is in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Read more about Lamarr’s story and inventions in this blog post by Joyce Bedi for the museum’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation.

An image of Lamarr’s patent can be viewed online at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Collections

- Open Access

A Strong and Lasting Bond

Hedy Lamarr

Celebrated as “the most beautiful woman in the world” during her Hollywood heyday in the 1940s, film star Hedy Lamarr (1914–2000) ultimately proved that her brain was even more extraordinary than her beauty. Eager to aid Allied forces during World War II, she explored potential military applications for radio technology. She theorized that varying radio frequencies at irregular intervals would prevent interception or jamming of transmissions, thereby creating an innovative communication system. Lamarr shared her concept for utilizing “frequency hopping” with the U.S. Navy and codeveloped a patent in 1941. Today, Lamarr’s innovation makes possible a wide range of wireless communications technologies, including Wi-Fi, GPS, and Bluetooth.

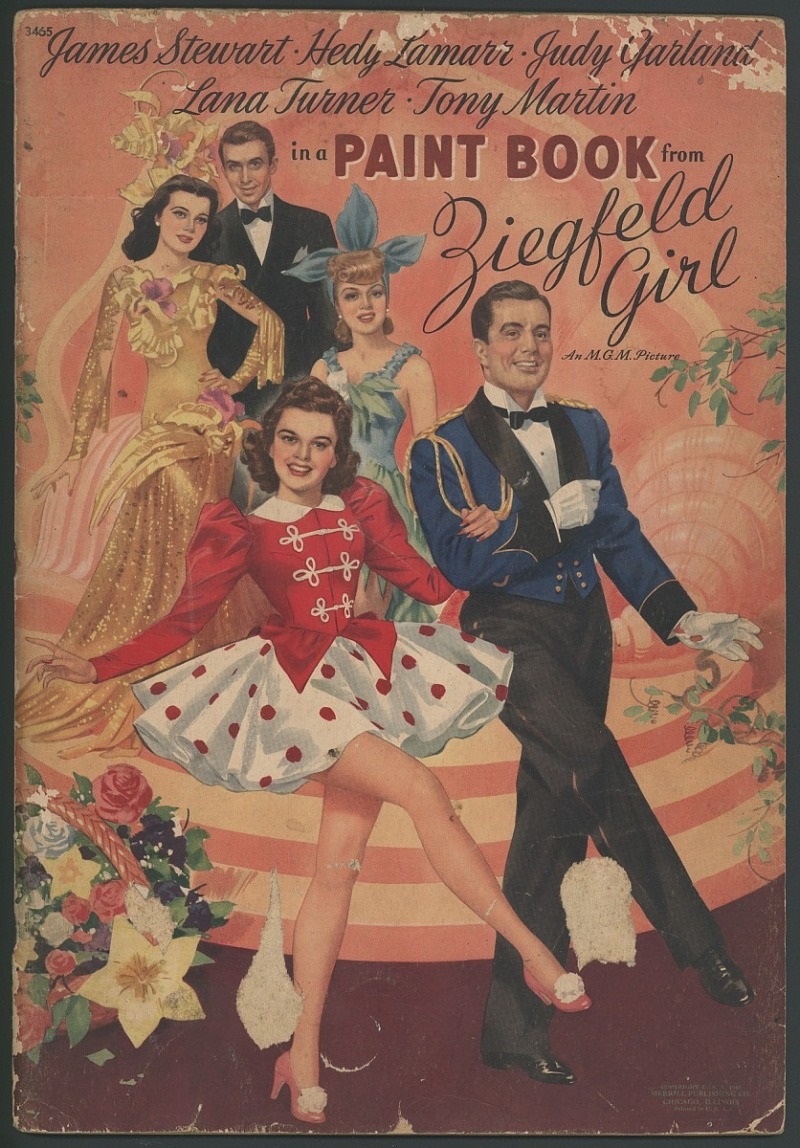

James Stewart, Hedy Lamarr, Judy Garland, Lana Turner, and Tony Martin in a Paint Book from Ziegfeld Girl

Object details.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Hedy Lamarr ( / ˈhɛdi /; born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler; November 9, 1914 [a] – January 19, 2000) was an Austrian-born American actress and inventor. After a brief early film career in Czechoslovakia, including the controversial erotic romantic drama Ecstasy (1933), she fled from her first husband, Friedrich Mandl, and secretly moved to Paris.

Famous Actors. Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum...

Hedy Lamarr, Austrian-born American film star who was often typecast as a provocative femme fatale. Years after her screen career ended, she achieved recognition as a noted inventor of a radio communications device. Learn more about Lamarr’s life and career.

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian-American actress and inventor who pioneered the technology that would one day form the basis for today’s WiFi, GPS, and Bluetooth communication systems. As a natural beauty seen widely on the big screen in films like Samson and Delilah and White Cargo, society has long ignored her inventive genius.

Hedy Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Kiesler in Vienna, Austria in 1914. She was the only child of a wealthy secular Jewish family. From her father, a bank director, and her mother, a concert...

Hedy Lamarr. Actress: Samson and Delilah. Hedy Lamarr, the woman many critics and fans alike regard as the most beautiful ever to appear in films, was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria. She was the daughter of Gertrud (Lichtwitz), from Budapest, and Emil Kiesler, a banker from Lemberg (now known as Lviv).

Married six times, she was an actress, pioneering female producer, ski-resort impresario, painter, art collector, and groundbreaking inventor, whose important innovations are meticulously cataloged...

Often called “The Most Beautiful Woman in Film,” Hedy Lamarr’s beauty and screen presence made her one of the most popular actresses of her day. She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1914 in Vienna, Austria. At 17 years old, Hedy starred in her first film, a German project called Geld auf der Strase.

She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria. Her father was the director of a bank and her Hungarian mother was a concert pianist. During a small dinner party in 1940, Lamarr met a kindred inventive spirit in George Antheil.

Explore. Collections. Hedy Lamarr. Brain power. Celebrated as “the most beautiful woman in the world” during her Hollywood heyday in the 1940s, film star Hedy Lamarr (1914–2000) ultimately proved that her brain was even more extraordinary than her beauty.