- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

12 Myth Three: The Hydraulic Model

- Published: October 2008

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The idea that emotions are feelings lends itself to another passive image, that of a psychic fluid filling up the mind or the body. This is referred to as the “hydraulic model.” This chapter challenges this as a misleading metaphor. To say that it is a metaphor, however, is not in itself to condemn it. Good science is filled with metaphors, often provocative, pregnant, and insightful. But this particular metaphor points us in exactly the wrong direction if we are to understand our emotions. Even the illustrious Freud employed it, and it led him to some of his most-often disputed models of the mind.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Find Study Materials for

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

The way aggression is expressed is somewhat complex. After an argument, slamming the door can release pent-up anger, which is a form of aggression. The hydraulic model of instinctive behaviour in aggression links together Lorenz’s theory of aggression (consisting of innate releasing mechanisms and fixed action patterns in ethology), focusing on the motivation behind an action, behaviour, and external stimuli to explain how aggression is expressed in animals.

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

- The Hydraulic Model of Instinctive Behaviour

- Explanations

- StudySmarter AI

- Textbook Solutions

- Behaviour Modification

- Biological Explanations for Bullying

- Bullying Behaviour

- Cortisol Research

- Deindividuation

- Ethological Explanations of Aggression

- Evolution of Human Aggression

- Fixed Action Patterns

- Frustration Aggression Hypothesis

- Gender and Aggression

- Genetic Origins of Aggression

- Genetic Research on Serotonin

- Genetical Research On Testosterone

- Genetics of Aggression

- Innate Releasing Mechanisms

- Institutional Aggression in The Context of Prisons

- Limbic System

- Media Influences on Aggression

- Neural and Hormonal Mechanisms in Aggression

- Serotonin Research

- Social Psychological Explanation of Aggression

- Sykes Deprivation Model

- Testosterone Research

- The Importation Model

- Violent Video Games and Aggression

- Warrior Gene

- Approaches in Psychology

- Basic Psychology

- Biological Bases of Behavior

- Biopsychology

- Careers in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognition and Development

- Cognitive Psychology

- Data Handling and Analysis

- Developmental Psychology

- Eating Behaviour

- Emotion and Motivation

- Famous Psychologists

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Individual Differences Psychology

- Issues and Debates in Psychology

- Personality in Psychology

- Psychological Treatment

- Relationships

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Schizophrenia

- Scientific Foundations of Psychology

- Scientific Investigation

- Sensation and Perception

- Social Context of Behaviour

- Social Psychology

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Nie wieder prokastinieren mit unseren Lernerinnerungen.

The way aggression is expressed is somewhat complex. After an argument, slamming the door can release pent-up anger, which is a form of aggression. The hydraulic model of instinctive behaviour in aggression links together Lorenz’s theory of aggression (consisting of innate releasing mechanisms and fixed action patterns in ethology), focusing on the motivation behind an action, behaviour, and external stimuli to explain how aggression is expressed in animals.

- We will explore Lorenz's theory of aggression, specifically examining the hydraulic model of instinctive behaviour.

- First, we will briefly define innate releasing mechanisms in ethology for context's sake.

- Then, we will provide a hydraulic model of aggression definition, highlighting vacuum activity and spontaneous fixed action patterns .

- Throughout, we will link back to motivation in animal behaviour and how this affects aggression.

- Finally, we will briefly evaluate Lorenz's hydraulic model of instinctive behaviour.

Lorenz's Theory of Aggression

Lorenz stated aggression was a necessary, adaptive response in animals. By displaying aggressive behaviours, the animal in question has a higher chance of securing the means for its survival.

- These include food, territory, and the right to mate.

Lorenz believed aggression occurred due to a build-up of pressure released by a sign stimulus, resulting in specific behaviours common across the species (FAPs triggered by IRMs, as discussed above). Aggression is a means to secure survival, so it usually does not result in animals fighting to the death, interestingly enough.

It would not be productive for animals to regularly fight to the death for resources, as the species would eventually begin to suffer.

Lorenz famously stated, in how his models related to human behaviour:

I believe... present-day civilized man suffers from the insufficient discharge of his aggressive drive.²

Innate Releasing Mechanisms in Ethology

Innate releasing mechanisms (IRMs) in ethology are hardwired neural networks in the brain that recognise specific stimuli ( sign stimuli or releases ) to trigger fixed action patterns (FAPs) , i.e., a sequence of actions encoded in response to these specific stimuli.

The hydraulic model of instinctual behaviour brings these ideas together to illustrate how this is implemented in an animal, considering the animal’s motivation and aggressive displays.

The Hydraulic Model in Psychology

A hydraulic model in psychology is a physiological or psychological model that proposes that when pressure builds in a system (i.e. a human), the built-up energy will need to be released.

Hydraulic Model of Aggression Definition

The hydraulic model of aggression visualizes Lorenz's idea on how aggressive behaviours occur in animals, specifically in that aggression builds up in a reservoir over time, and a sign-stimulus or releasor unleashes the built-up aggression, resulting in aggressive behaviours. It involves a reservoir (drive), a release mechanism, a stimulus which "unplugs" the reservoir, and resulting behaviours upon release.

Overall, the hydraulic model visualises the pent-up aggression an animal may experience and how it is released, taking into account IRMs and FAPs and acknowledging motivation in animal behaviour.

Interestingly, Lorenz’s hydraulic model of instinctual behaviour goes back to the work of Freud . He believed that aggression was an inevitable outcome because, in his view, animals, especially males, are biologically programmed to fight for what they deem necessary for their survival (as we discussed above). Take a look at the diagram below:

Lorenz believed that aggression increases over time as the urge to be aggressive builds up in animals. Once the internal pressure to be aggressive builds up enough, a sign stimulus releases it, triggering aggression.

The reservoir is emptied in this case and is more sensitive the longer the time that has passed since the last release. Let's explore how the hydraulic model of instinctive behaviour links to motivation in animal behaviour, specifically, how fluid in the model builds up and drives the mechanism.

Motivation in Animal Behaviour

Motivation is the fluid that accumulates in the reservoir and becomes the drive to act in this mechanism.

Action-specific energy or pent-up aggression accumulates in the reservoir, and the sign stimulus serves as the trigger. In this case, the stimulus is the weight that clogs the reservoir.

A sign stimulus will ‘release’ the pent-up reservoir, resulting in FAPs, and FAPs can vary depending on how much the reservoir releases. The spouts indicate different behaviours, and different levels of release result in different behaviours.

Once this occurs, the animal’s aggression level drops (known as behavioural quiescence ) until the pent-up aggression builds back up, and the process repeats.

Motivation increases over time , so the reservoir builds up over time . Motivation in animal behaviour is specific to the behaviours it triggers (e.g., when a species needs to mate or secure food).

A male stickleback has increased motivation to mate with a female stickleback during the mating season. This motivation rises over time and accumulates in its ‘reservoir’.

When the male stickleback encounters another male stickleback, identifiable by its red underbelly (the sign stimulus or release), it releases this reservoir. It begins its FAP, aggressive behaviour to fend off competition.

Rhoad and Kalat (1975) observed the aggressive behaviour of male Siamese fighting fish ( Betta splendens ) in response to other male fish (recognised by their bright colours), a mirror image of the fish, a moving model, and a stationary model. They exposed the fish to each stimulus for one hour per day.

Typically, Siamese fighting fish inflate in response to the presence of another male by inflating their dorsal, ventral, and caudal fins, among others.

Rhoad and Kalat (1975) found that the fish would puff up in response to any stimulus, exhibiting similar behaviours. The mirror image elicited a response most effectively , followed by the moving and stationary models. However, another fish is still more effective than the mirror image, and its effectiveness does not depend on the stimuli’s order.

- After repeated exposure, the aggressive behaviours decreased rapidly .

- However, the fish were still alert to the stimuli, but they actively avoided them instead of being aggressive (habituation), which could signify how the ‘reservoir’ needs to replenish itself.

Vacuum Activity and Spontaneous FAPs

In Lorenz’s model, either the stimulus causes the release of pent-up aggression, leading to FAPs, or the pressure from the reservoir spontaneously discharges (usually due to a lack of sign stimulus' or releasors).

Known as vacuum activities , the pent-up aggression has built up to a point where it must be released and does so in the absence of external stimuli . It makes its way out and leads to a FAP.

Typically, animals in captivity display vacuum activities as there is a lack of external stimuli to help them release pent-up aggression.

Evaluation of Lorenz’s Hydraulic Model (1950)

Konrad Lorenz’s theories are essential for multiple reasons, namely through their contributions to understanding behaviour in animals, specifically aggression, and acting as a model for comparative aggression in humans.

However, the model has a few problems, which we will address here:

Arms et al. (1979) measured spectators watching aggressive sports on scales of hostility. Male and female participants were exposed to stylised aggression (professional wrestling), realistic aggression (ice hockey), and competitive non-aggressive events (i.e., swimming).

They found aggression and hostility increased rather than decreased after viewing the events. However, this was not the case for the non-competitive events.

The Hydraulic Model of Instinctive Behaviour - Key takeaways

- Lorenz’s theory of aggression is linked to the hydraulic model of motivation, which focuses on the motivation behind an action, behaviour, and external stimuli to explain how aggression is expressed in animals.

- Overall, the hydraulic model visualises pent-up aggression that can be released in an animal, incorporating innate releasing mechanisms (IRMs) and fixed action patterns (FAPs) while acknowledging the animals’ motivation.

- The hydraulic model illustrates how action-specific energy or pent-up aggression accumulates in a reservoir, and a stimulus acts as a release. In this case, the stimulus is the weight that clogs the reservoir. Release triggers a FAP.

- Once the hydraulic model’s aggression buildup is relieved, the animal’s aggression level drops (known as behavioural quiescence) until the aggression buildup rebuilds, and the process repeats. Spontaneous acts of aggression (known as vacuum activities) may occur if the reservoir is not released due to absences in sign stimuli.

- The model fails to recognise the ability to learn and adapt FAPs and is overly simplistic without much structural evidence in the brain.

- Fig. 2 - Hydraulic model of motivation diagram by Shyamal, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Konrad Lorenz. (1966). On aggression. Translated by Marjorie Latzke. London, Methuen & Co.

Frequently Asked Questions about The Hydraulic Model of Instinctive Behaviour

--> what is the hydraulic model in psychology .

In psychology, specifically ethology, the hydraulic model is a concept Konrad Lorenz developed to demonstrate the release of pent-up aggression in animals (innate releasing mechanisms), specifically by showing a reservoir of motivation/aggression. A sign stimulus releases this reservoir to cause fixed action patterns to specific stimuli.

--> Who proposed the psychohydraulic model?

Konrad Lorenz proposed the psychohydraulic model (1950).

--> What was Konrad Lorenz’s theory?

Konrad Lorenz’s theory surrounded the concept of aggression and its release in animals, explicitly referencing innate releasing mechanisms and fixed action patterns.

--> Why is Konrad Lorenz’s theory important?

Konrad Lorenz’s theories are essential for multiple reasons, namely through their contributions to understanding behaviour in animals, specifically aggression, and acting as a model for comparative aggression in humans.

Test your knowledge with multiple choice flashcards

True or False: Motivation increases as time goes on.

True or False: The hydraulic model fails to acknowledge premeditated aggression.

True or False: The way aggression is expressed differs in animals.

Your score:

Join the StudySmarter App and learn efficiently with millions of flashcards and more!

Learn with 20 the hydraulic model of instinctive behaviour flashcards in the free studysmarter app.

Already have an account? Log in

What is the hydraulic model of instinctive behaviour?

The hydraulic model of instinctive behaviour is a concept Konrad Lorenz developed to demonstrate the release of pent-up aggression in animals (innate releasing mechanisms), specifically by showing a reservoir of motivation/aggression. A sign stimulus releases this reservoir to cause fixed action patterns to specific stimuli.

Who proposed the hydraulic model of instinctive behaviour?

Konrad Lorenz (1950).

How does the hydraulic model relate to innate releasing mechanisms and fixed action patterns?

It ties them together to show how aggression builds up and is released in an animal.

What does Lorenz’s hydraulic model derive from?

Freud’s work.

What did Konrad Lorenz believe about aggression?

He believed it was inevitable, particularly for males, as they are biologically programmed to fight for survival.

What components exist in the hydraulic model?

The components are:

- The drive/motivation (liquid) building up in the reservoir (pent-up aggression).

- The weight and sign stimulus clogging the reservoir and releasing to initiate behaviours.

- The spouts indicating different levels of behaviours.

of the users don't pass the The Hydraulic Model of Instinctive Behaviour quiz! Will you pass the quiz?

How would you like to learn this content?

Free psychology cheat sheet!

Everything you need to know on . A perfect summary so you can easily remember everything.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

This is still free to read, it's not a paywall.

You need to register to keep reading, create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Entdecke Lernmaterial in der StudySmarter-App

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Developing a Hypothesis

Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis, it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition (1965) [1] . He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observations before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [2] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

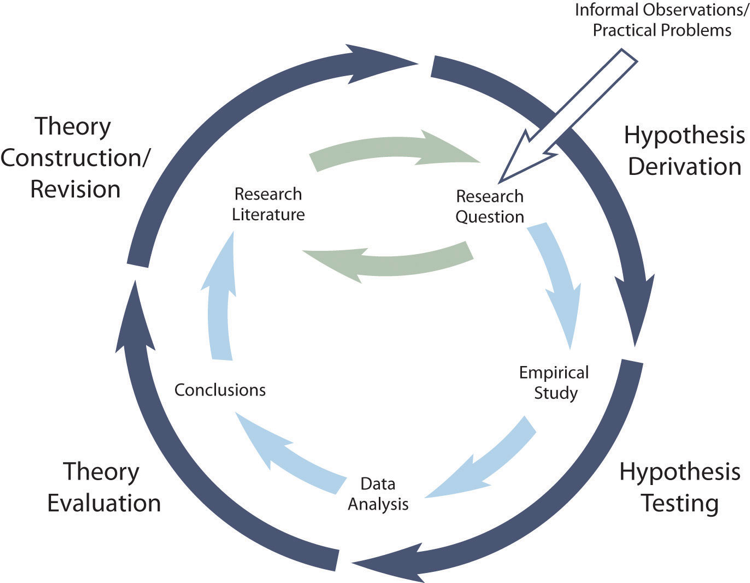

Theory Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret them or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.3 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [3] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans [Zajonc & Sales, 1966] [4] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that it really does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149 , 269–274 ↵

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

A coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena.

A specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate.

A cyclical process of theory development, starting with an observed phenomenon, then developing or using a theory to make a specific prediction of what should happen if that theory is correct, testing that prediction, refining the theory in light of the findings, and using that refined theory to develop new hypotheses, and so on.

The ability to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and the possibility to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false.

Developing a Hypothesis Copyright © 2022 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Stress and coping theory across the adult lifespan.

- Agus Surachman Agus Surachman Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University

- and David M. Almeida David M. Almeida Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.341

- Published online: 30 July 2018

Stress is a broad and complex phenomenon characterized by environmental demands, internal psychological processes, and physical outcomes. The study of stress is multifaceted and commonly divided into three theoretical perspectives: social, psychological, and biological. The social stress perspective emphasizes how stressful life experiences are embedded into social structures and hierarchies. The psychological stress perspective highlights internal processes that occur during stressful situations, such as individual appraisals of the threat and harm of the stressors and of the ways of coping with such stressors. Finally, the biological stress perspective focuses on the acute and long-term physiological changes that result from stressors and their associated psychological appraisals. Stress and coping are inherently intertwined with adult development.

- social stress

- psychological stress

- biological stress

- life events

- chronic stressors

- daily stressors

What Is Stress?

While stress is difficult to define (Contrada, 2011 ), stress researchers tend to share a common interest in a process by which external, environmental, or psychosocial demands surpass an individual’s adaptive capacity and result in biological and psychological changes that have the potential to jeopardize one’s health and well-being (Cohen, Kessler, & Gordon, 1997 ; Contrada, 2011 ). Stress can thus be viewed as a process delineated by three components (Almeida, Piazza, Stawski, & Klein, 2011 ; Cohen et al., 1997 ; Wheaton, 1994 ; Wheaton & Montazer, 2010 ): stressors (external or environmental demands), stress appraisals (the perceived severity of stressors), and distress (affective, behavioral, or biological responses to stressors).

Each of these components is emphasized in one of three theoretical stress perspectives: social, psychological, and biological (Cohen et al., 1997 ). The social stress perspective highlights the way that environmental or external demands precipitate individuals’ stress and how such demands are contingent upon contextual factors or social circumstances (Wheaton & Montazer, 2010 ). The psychological stress perspective focuses on individuals’ appraisals of stressors and the availability of coping resources to manage the overwhelming demands of such stressors (Cohen & Janicki-Deverts, 2012 ; Lazarus, 1999 ). Finally, the biological stress perspective highlights how and when physiological systems become activated by stress processes that may risk individuals’ physical health (Cohen et al., 1997 ). The purpose of this article is to describe each of these theoretical perspectives and their relevance to aging research.

Social Stress Perspective

The social stress perspective primarily focuses on the origins of stressful life experiences (Aneshensel, 1992 ; Pearlin, 2009 ). According to the social stress perspective, the experience of stressors is structurally constrained (Wheaton, 1999 ; Pearlin, 2009 ). Exposure to external demands is not random, but rather embedded in an individual’s position in society, social structure, social organizations, roles, and other social constructs (Aneshensel, 1992 ; Wheaton, 1999 ). Two central themes have emerged from the social stress perspective: (a) the differentiation of categories of stressor types and (b) the ways that social structures link to individuals’ experiences of stressors.

Categories of Stressors

Stressors are commonly divided into five categories: life events, chronic stressors, daily stressors, trauma, and nonevents (Wheaton, 1994 , 1999 ; Wheaton & Montazer, 2010 ).

Life Events

Life events , also known as life change events or event stressors , are discrete, observable stressor events that have a clear onset and offset (Wheaton & Montazer, 2010 ). Some examples of life event stressors are the death of a spouse, divorce, and job loss. The modern study of social stress started with the analysis of life events, partly because the easily verifiable nature of these events make it possible to operationalize the concept of stress itself (Wheaton, 1994 ; Wheaton & Montazer, 2010 ). One challenge of this research is identifying a pool of all possible life events that an individual might experience (Aneshensel, 1992 ). For example, items in the stressful life event scales often mix life events with traumas and daily stressors (Aldwin & Yancura, 2011 ).

Life event representation is an important issue for aging researchers. For example, an early study found an inverse association between age and exposure to life events, with older individuals showing fewer life events than their younger counterparts (Rabkin & Struening, 1976 ). Such a result runs counter to the general assumption that late life is associated with higher stressors due to the development of chronic illnesses and higher levels of bereavement (Aldwin & Yancura, 2011 ). However, further analysis showed that the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (Holmes & Rahe, 1967 ) that was used by Rabkin and Struening in their study consisted of items that included life events pertaining to younger individuals, such as marriage, birth, divorce, graduation, and job loss (Aldwin & Yancura, 2011 ). Analysis of life events using items designed for older individuals showed that there was no association between age and exposure to life events (Aldwin, 1990 ). Another study of life events showed that different sociohistorical experiences (e.g., wars, terrorist attacks, and economic downturn) influenced different levels of reported life events, indicating significant period effects (Chukwourji, Nwoke, & Ebere, 2017 ; Elder & Shananhan, 2006 ; Pruchno, Heid, & Wilson-Genderson, 2017 ). More longitudinal studies are needed to disentangle the influence of age and sociohistorical experiences on the reporting of stressful life events.

Chronic Stressors

The concept of chronic stressors , from a social stress perspective, originated from a study of chronic role strain by Pearlin and Schooler ( 1978 ) that articulated the importance of chronic disruptions in important social roles (e.g., marriage, work, and parenting) for health and well-being. Additional work by Wheaton and Montazer ( 2010 ) refined these ideas by providing three defining characteristics of chronic stressors that set them apart from event stressors:

Chronic stressors develop slowly and insidiously as continuous problems related to social roles and the social environment. In addition, chronic stressors may or may not start out as events.

The duration of the stressors from onset to offset is usually longer than the duration of life events.

Chronic stressors include both regular problems and issues related to daily roles and more specific problems, making them less self-limiting than life events.

Although chronic stressors are often tied to social roles, they also can include ambient stressors , which are not role bound, such as time pressure, financial problems, or living in a noisy place (Kershaw et al., 2015 ; Henderson, Child, Moore, Moore, & Kaczynski, 2016 ; Wheaton & Montazer, 2010 ). Table 1 provides a description of seven types of problems that are considered chronic stressors (Wheaton, 1997 ).

Most studies of stress involving older adults focused on chronic stressors (Aldwin & Yancura, 2011 ; Grzywacz, Almeida, Neupert, & Ettner, 2004 ). However, more research is needed to investigate age differences across adulthood in the prevalence and duration of chronic stressors (Aldwin & Yancura, 2011 ). Different age groups might have different sources of chronic stressors, which might lead to a similar rate of prevalence and duration of chronic stress (e.g., chronic diseases among older adults, as opposed to economic hardships among younger individuals).

Table 1. Problems Considered as Chronic Stressors

Daily stressors.

Daily stressors , or daily hassles , are often mistaken as chronic stressors (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981 ). The defining characteristics of daily stressors, which separate them from chronic stressors, are their duration and magnitude of severity. DeLongis, Folkman, and Lazarus ( 1988 ) characterized a daily stressor or daily hassle as a short-duration experience of a stressor, such as having an argument with a partner or getting caught in a traffic jam. In addition, Almeida ( 2005 ) defined daily stressors as relatively minor events experienced in day-to-day living. Table 2 provides example questions from the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE), used by researchers to ascertain information about the frequency of people’s daily stressors.

Compared to life events, daily stressors tend to have a more proximal effect on well-being (Almeida, 2005 ; Almeida et al., 2011 ). Daily stressors produce spikes in psychological distress during a particular day, while life events create prolonged bouts of distress (Almeida, 2005 ; Almeida et al., 2011 ). Daily stress also may have prolonged health effects when piled up across days, which in turn creates persistent irritations, frustrations, and overloads, including chronic physical and psychological distress, chronic conditions and functional impairment, and mortality (Chiang, Turiano, Mroczek, & Miller, 2018 ; Lazarus, 1999 ; Leger, Charles, Ayanian, & Almeida, 2015 ; Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981 ; Piazza, Charles, Sliwinski, Mogle, & Almeida, 2013 ; Zautra, 2003 ).

Such a pileup of stressors (i.e., accumulation of stressor exposure or total number of stressors that an individual experiences) is more problematic if the stressors experienced are less diverse (i.e., low evenness of the type of daily stressors that an individual experiences). Higher levels of stressor exposure that are accompanied by lower levels of stressor diversity indicate a depletion of specific types of resources and may indicate the chronicity of the stressors (see Koffer, Ram, Conroy, Pincus, & Almeida, 2016 , for an extensive discussion of stressor diversity).

The experience of daily stress differs across adulthood. Based on Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) data, a national longitudinal study of health and well-being ( http://midus.wisc.edu ), adults in the United States report at least one stressor on 40% of study days, and multiple stressors on 10% of study days (Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002 ). In general, studies show that the type and frequency of daily stressors differ by age (Aldwin, Sutton, Chiara, & Spiro, 1996 ; Almeida & Horn, 2004 ; Chiriboga, 1997 ). Mroczek and Almeida ( 2004 ) found that older adults reported fewer daily stressors, measured using DISE (see Table 2 ), and less stressor-related daily negative affect than younger individuals; however, older participants reported a higher level of severity in the reported stressors. Finally, Stawski, Sliwinski, Almeida, and Smyth ( 2008 ) found that there were no age differences in daily stressor-related negative affect.

Stressors sometimes can be categorized as traumatic. Trauma is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition) as “events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others . . . the person’s response [to the events] involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror” (APA, 1994 , pp. 427–428). However, according to Wheaton and Montazer ( 2010 ), not all traumas happen as events. Physical abuse that happens one time during childhood might fit the definition of a traumatic event. On the other hand, repeated and regular experiences of physical abuse might be better categorized as a chronic traumatic experience. Another important defining characteristic of trauma is its greater severity compared to other types of stressors. As a consequence, traumas might have a greater impact on long-term health and well-being.

Table 2. Questions From the DISE

Note : A “Yes” answer to each stem question is followed up with questions, including (a) a series of open-ended “probe” questions that ascertain a description of the stressful event, (b) a question regarding the perceived severity of the stressor, and (c) a list of structured primary appraisal questions inquiring about goals and values that were “at risk” because of the event (Almeida et al., 2002 ).

Source : Almeida et al. ( 2002 )

According to Ozer, Best, Lipsey, and Weiss ( 2003 ), most people experience at least one violent or life-threatening situation during their lives. Among older adults, car accidents are the most common source of trauma (Weintraub & Ruskin, 1999 ). In addition, a study by Wheaton, Roszell, and Hall ( 1997 ) indicated that being sent away from home in childhood is the least common trauma (prevalence rate = 3.5%) and the death of a spouse, child, or other loved one is the most common traumatic experience (prevalence rate = 50%). Using the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ) shown in Table 3 , Ogle, Rubin, Berntsen, and Siegler ( 2013 ) found that nondisclosed childhood physical abuse is the least common trauma, and unexpected death, illness, or accident involving a loved one is the most common trauma.

Table 3. The TLEQ and Its Prevalence Among Adults in the United States

Note: n = 3,208.

Sources: Kubany et al. ( 2000 ); Ogle et al. ( 2013 ).

The last category of stressors are nonevents , defined as anticipated events or experiences that do not happen in reality (Gersten, Langer, Eisenberg, & Orzeck, 1974 ; Neugarten, Moore, & Lowe, 1965 ). Normative expectations play an important role in the stressfulness of nonevents such as not getting married by a certain age or not getting an anticipated promotion at a certain career stage (Frost & LeBlanc, 2014 ). Schuth, Posselt, and Breckwoldt ( 1992 ) studied miscarriage in the first trimester as a nonevent stressor. According to Wheaton and Montazer ( 2010 ), nonevents that have no tie to normative timing are more similar to chronic stressors, such as expecting a loan for low-income housing, but not receiving one.

Social Stress and Health: Exposure Versus Vulnerability

There are two hypotheses that researchers draw on to explain how social structures link to stressors and health outcomes: the exposure hypothesis and the vulnerability hypothesis (Aneshensel, 1992 ; Turner, Wheaton, & Lloyd, 1995 ). These competing hypotheses focus on disentangling whether exposure or vulnerability to stressors leads to disease risk. Stressor exposure is the likelihood that a person will be exposed to stressors given her or his social location, such as socioeconomic status (SES) or gender, and individual characteristics, such as personality (Almeida et al., 2011 ). On the other hand, vulnerability to stressors relates to the concept of reactivity , which is the likelihood that one will show physical or psychological reactions to experienced environmental demands or stressors (Almeida, 2005 ; Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995 ; Cacioppo, 1998 ).

There is considerable evidence supporting the idea of differentiated exposure to stressors based on sociodemographic, psychosocial, and situational characteristics as an explanation of why some people are healthier than others. For example, researchers have found that SES (Evans & Kim, 2010 ; Turner et al., 1995 ; Turner & Avison, 2003 ), age (Aldwin, 1990 ; Almeida & Horn, 2004 ; Hamarat et al., 2001 ), personality (Bouchard, 2003 ; Ebstrup, Eplov, Pisinger, & Jørgensen, 2011 ; Penley & Tomaka, 2002 ), and social support (Brewin, MacCarthy, & Frunham, 1989 ; Felsten, 1991 ; Huang, Costeines, Kaufman, & Ayala, 2014 ; Kwag, Martin, Russell, Franke, & Kohut, 2011 ) play critical roles in differentiating individuals’ experiences of stressor exposure.

However, there is also substantial evidence to support the vulnerability hypothesis. For example, a recent analysis of exposure and vulnerability to daily stressors showed that SES was not associated with exposure to daily stressors. However, individuals with lower SES were more reactive to the daily stressors that they experienced (Almeida, Neupert, Banks, & Serido, 2005 ; Grzywacz et al., 2004 ; Surachman, Wardecker, Chow, & Almeida, 2018 ). There are at least four speculated reasons for this (Grzywacz et al., 2004 ; Surachman et al., 2018 ), including (a) the experience of chronic stressors may desensitize individuals with lower SES in their reactions to minor day-to-day stressors; (b) the possibility of gender and racial differences that obscure the systematic variation in exposure to daily stressors; (c) individuals with lower SES may be less reflective and articulate when reporting their daily stressors; and (d) individuals from lower SES may encounter similar types of daily stressors, indicating a low number of daily stressors encountered and lower levels of daily stressor diversity.

Psychological Stress Perspective

The psychological stress perspective focuses on an individual’s perception and evaluation of the potential damage caused by external environmental demands (Cohen et al., 1997 ). The two concepts that are fundamental to the psychological stress perspective are appraisal and coping (Krohne, 2002 ). The stress appraisal model, developed by Lazarus & Folkman ( 1984 ) is the most influential psychological stress model. According to this perspective, the way that we evaluate external events (i.e., stressors) determines our degree of stress. Specifically, Lazarus and Folkman ( 1984 , p. 19) define psychological stress as “a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being.”

Psychological Stress and Appraisal

Arnold ( 1960 ) was the first theorist to use the term appraisal in the context of emotion and personality. Appraisal became the central concept of Lazarus’s psychological stress theory. The term appraisal refers to the continuous evaluation by individuals of their relationship with the external environment with respect to their implications for well-being (Lazarus, 1999 ).