- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Education programmes, discover unicef's work worldwide..

← Back to Education

UNICEF works day in and day out, in some of the world’s toughest places, to protect children’s rights and safeguard their futures. On the ground in over 190 countries and territories, we reach more children and young people than any other international organization. Explore our education programmes, initiatives and partnerships.

Inclusive education

Girls' education

Education in emergencies

Early childhood education

Primary education

Adolescent education and skills

Digital Education

Strengthening education systems and innovation

Global partnerships and initiatives, reimagine education.

In a world facing a learning crisis, digital learning should be an essential service. UNICEF aims to have every child and young person – some 3.5 billion by 2030 – connected to world-class digital solutions that offer personalized learning.

Learning Passport

A TIME Best Invention of 2021, the Learning Passport enables high-quality, flexible learning for children anywhere, to close the learning poverty gap.

Generation Unlimited

If the largest generation of young people in history is prepared for the transition to work, the potential for global progress is unlimited. We enable young people to become productive and engaged members of society.

The Giga Initiative was launched to connect every school to the internet and every young person to information, opportunity and choice.

Education Cannot Wait

Education Cannot Wait is the United Nations global fund for education in emergencies and protracted crises. We support and protect holistic learning outcomes so no one is left behind.

EdTech Hub is a global research partnership that empowers people by giving them the evidence they need to make decisions about technology in education.

Global Partnership for Education

GPE is the world’s only partnership and fund focused on providing quality education to children in lower-income countries.

Global Education Cluster

The Global Education Cluster works towards a predictable, equitable and well-coordinated response addressing education concerns of crisis-affected populations.

United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

Through evidence building, coordinated advocacy and collective action, the UNGEI partnership works to close the gender gap in education.

All in School

In collaboration with the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, this initiative provides governments with actionable data to identify barriers that lead to exclusion and develop policies and programmes that put more children on track to complete their education.

Teachers wanted

Empowering teachers at the forefront of the learning crisis

Climate action for a climate-smart world

UNICEF and partners are monitoring, innovating and collaborating to tackle the climate crisis

The inspiring journey of Steward Francis

How education transformed the life of a South Sudanese child refugee

Youth voices at the forefront of climate conservation

Engagement platform provides space for youth climate activists

Straight from the experts

Breaking news and analysis from UNICEF's Education team.

The Project Approach to Teaching and Learning

What is the Project Approach?

The Project Approach offers teachers a way to develop in-depth thinking while engaging the hearts and minds of young children. Teachers take a strong guidance role in the process while children study topics with purpose and flexibility. Project work presents many opportunities for young children’s ideas to be valued, their creativity to be encouraged, their interests to be nurtured, and for their learning needs to be met.

In early childhood, projects can be defined as open ended studies of everyday topics which are worthy of being included in an educational program. Projects emerge from the questions children raise and develop according to their particular interests. Rather than offering immediate answers to the questions children ask, teachers provide experiences through which children can discover the answers themselves through inquiry at field sites and interviewing experts. For example, if the children wonder what shoes are made of or how are they made, the teacher may arrange a field visit where the answer to these questions can be provided by an expert, in this case a shoe factory, the shoe repair man’s shop, or a shoe store. Children also consult secondary sources of information such as books and the internet in the classroom and with their parents at home.

Project investigations promote in-depth understanding and cover a wide range of relevant subtopics. For this reason projects usually take several weeks to complete—and sometimes much longer, depending on the age and interests of the children.

The Project Approach, then, is the method of teaching children through project investigations. Because project work follows an unpredictable path based on the interests of particular children, a flexible framework to support teachers has been developed. This framework makes the inquiry more manageable: it shapes the development of the area of investigation. Teachers guide children through a three phase process from the beginning of a project to its conclusion. You may find the Project Planning Journal helpful in understanding and implementing project work. It’s from the book Young Investigators: The Project Approach in the Early Years by Judy Harris Helm and Lilian G. Katz.

What is the Structure of the Project Approach?

Phase 1: In the beginning of a project, the teacher builds interest in the topic through encouraging the children to share relevant personal stories of experience. As the children represent their current understanding of the topic; the river, cars, or dogs, for example, the teacher assesses the children’s vocabulary, their individual interests, misconceptions or gaps in current knowledge, and helps them formulate questions which they can investigate.

Phase 2: As the inquiry begins in earnest, teachers enable the children go on field visits, interview adults who are experts, such as waiters, farmers, or nurses, for example, according to the topic of study. Children also look at books, internet sites, videos, and so on. As they learn more about the topic they use many forms of representation to illustrate what they have learned and to share new knowledge with their classmates.

Phase 3: Finally, the teacher guides the conclusion of the study and helps the children review their achievements. The children share their work with parents, another class, or members of the local community who have helped them in the process of the investigation. This final phase of the work includes the assessment by teachers of what the children have learned through the project. All children will have learned basic facts about the topic. Some children will have learned more about certain aspects of the topic such as the role of the adults, or the steps or materials used in the manufacture of an important item. There will be times when one child may have achieved individual learning goals such as developing confidence in a particular personal strength or learning to collaborate effectively with other classmates.

Sharing what they have learned with others helps the children to review their achievements.

What are the advantages of the Project Approach?

When teachers encourage children’s curiosity and help them to ask questions, the study of local everyday topics becomes interesting and relevant to them. Young children’s learning is energized as they become part of a community of investigators and share the findings of their inquiry. Children apply skills and knowledge in their study of buses, shoes, trees, or grocery stores. They learn about the value of reading, writing, and numbers in the life of the adults around them. In the context of the project the children become apprentices in the pursuit of knowledge alongside their teachers. Teachers take a responsive role in developing the project. They coordinate different interests and support small group and individual inquiries as these emerge. Teachers who use the project approach report that students show great interest and actively participate. They ask questions and follow up their own curiosity with investigations.

Along with the motivation it provides, project work also integrates all areas of learning and aspects of child development. It offers many chances to practice problem solving and critical thinking—skills that build language, math and scientific understanding. In fact, it helps children gain confidence in themselves and their abilities and develops in them the disposition to strive for understanding.

How does the Project Approach align with curriculum requirements and standards?

This type of learning differs considerably from the preplanned lessons of a published curriculum. While project work supports the curriculum standards identified for testing, teachers do not teach to the test through project work. The emphasis is on the context in which learning is intrinsically motivated and engaging to young children.

Through careful observation and skillful planning on the part of the teacher, curriculum goals can be integrated into project work. The teacher anticipates where a project may go, and includes elements of the required curriculum in her plans. For example, the curriculum goal of data collection and analysis can be incorporated into a project on cars, if children decide to count and record the kinds of cars they see. The teacher records her plan and project documentation provides evidence of learning.

In addition to the aspects of the curriculum which relate directly to the acquisition of skills and knowledge, project work offers interesting opportunities for children to apply and practice what they have learned in other parts of their daily program in school. Intrinsic motivation enables children to learn through projects in personally meaningful ways. Children who excel in certain academic areas learn to offer leadership to their peers. Children who experience difficulty in some areas frequently learn from skilled or knowledgeable peers more easily than from adults.

In classrooms where the Project Approach is well implemented, teachers and parents report that children show increased achievement and confidence in talking about what they know and can do.

Curriculum goals, such as data collection and analysis, can be naturally integrated into project work.

How does the Project Approach fit with other teaching strategies?

Project work can be incorporated into learning centers, as well as into a typical daily schedule. For example, circle time can be used to discuss a current investigation or books on the subject can be placed in the literacy area.

However, with all its advantages, most early childhood professionals would agree that project work alone does not cover all the learning experiences that should be included in the curriculum. Children learn through many different experiences in school. For young children these experiences include sensory exploration, various kinds of play activity, observation, and practice. They learn some things through direct instruction, some through small group work, some through repeated trials and persistence, and some through collaboration and lively discussion with their classmates.

The Project Approach offers children the flexibility to develop interests, to work hard at their strengths, to share expertise and make personal contributions to the work of the classroom. The use of open-ended learning centers in a classroom can make for easier differentiation by teachers in their instruction as they help children to self-assess and challenge themselves appropriately in the classroom context.

Open-ended learning centers complement project work by allowing children to reconstruct their experiences.

What are the challenges of implementing the Project Approach?

The principle challenge for teachers is to know the children well and to be able to guide them effectively in their inquiry. It requires dedication and creativity to take full advantage of individual strengths and interests, engage parental expertise (for interviews, access to field sites, etc.), and seek out resources. The key to a successful project is the teacher’s daily classroom assessment; it guides the work towards optimal learning opportunities in responsive environments for all children. These challenges demand that the teacher’s own creativity be engaged in crafting with the children the stories of their learning through projects.

As with any teaching approach or method, positive results are only evident when the teaching is done well. It is easier to set up learning centers with activities, worksheets, and boxes of props which are the same each year. It is easier to read the same fantasy literature and have the children play the parts of the characters in dramatic play year after year. In project work, teachers depend on rich communication with the children to determine their interests and prior levels of understanding. A project on ‘pets’ for instance, may focus on different subtopics from one year to the next as different groups of children and their parents show interests, expertise, or gaps in knowledge. One year the direction might be how to care for pets’ everyday needs, another year the focus might be around pet health and the work of the veterinarian, while yet another might be the work that animals can do for human beings, such as service dogs, leisure pursuits and exercise, or work with the elderly or young people with autism or other challenges. Teacher’s responsiveness to children challenges them always to bring fresh thinking to project work.

Another challenge for teachers is to plan the work so that there is a unity and cohesiveness to each project which all the children can appreciate. As various interests are developed teachers have to keep the communication focused on the value of each group’s contribution to the knowledge and understanding of the topic by all the children in their classes.

Yet, teachers wishing to help students develop a life-long love of learning and understand the interconnected relationship of all things will find there are unique advantages to project learning.

Beghetto, RA & Kaufman, JC (2013). Fundamentals of Creativity. Educational Leadership , Vol. 70, No. 5, pp. 10-15.

Chard, SC (2009) The Project Approach: Six Practical Guides for Teachers. These guides are available as .pdf files at the following web site: www.projectapproach.org

Katz LG & Chard, SC (2000) Engaging Children’s Minds: The Project Approach , Greenwood.

is Professor Emerita of Early Childhood Education at the University of Alberta, Canada. She has worked at the University since 1989; for seven years as director of the elementary education laboratory school. Dr. Chard has taught at various levels from preschool through high school in England, and completed her M.Ed. and Ph.D. at the University of Illinois. Dr. Chard has written extensively about the Project Approach, including the book Engaging Children's Minds: The Project Approach , which she co-authored with Lilian G. Katz. Dr. Chard maintains a website and blog The Project Approach and lectures around the world.

Let's Stay in Touch

Request a Free Catalog:

Sign up for our weekly blog

THE PROJECT APPROACH

Managed by the Educators Institute at Duke School

ENGAGING CHILDREN'S MINDS

Building on natural curiosity to engage, problem-solve, and connect

Authentic Discovery

Problem-Solving

Extending beyond the classroom to each student's community

Shaping the next generation of problem-solvers

Natural Curiosity

Building on natural curiosity to enable interaction and connection

The Project Approach

Children have a strong disposition to explore and discover. The Project Approach builds on natural curiosity, enabling children to interact, question, connect, problem-solve, communicate, reflect, and more. This kind of authentic learning extends beyond the classroom to each student’s home, community, nation, and world. It essentially makes learning the stuff of real life and children active participants in and shapers of their worlds.

The Project Approach Study Guide

The study guide offers educators an overview of the Project Approach and guides them through the process of developing and implementing a project in the classroom. Readings provide both practical knowledge and a theoretical framework, while assignments offer a flexible, step-by-step approach that allows teachers to learn in the process of trying out their first (or second or third) project in the classroom.

The Guide is an adaptation of the online course as taught by Project Approach founder, Sylvia Chard. It is still a little like a course but designed for a teacher to study for him or herself.

Journal prompts with each of the seven sections offer opportunities for teachers to reflect on and refine their strategies, ideas, and practices. Establishing a regular journal writing routine is a fundamental part of project-based teaching as this is a process that evolves with reflection and experience.

- Complete My Donation

- Why Save the Children?

- Charity Ratings

- Leadership and Trustees

- Strategic Partners

- Media, Reports & Resources

- Financial Information

- Where We Work

- Hunger and Famine

- Ukraine Conflict

- Climate Crisis

Poverty in America

- Policy and Advocacy

- Emergency Response

- Ways to Give

- Fundraise for Kids

- Donor-Advised Funds

- Plan Your Legacy

- Advocate for Children

- Popular Gifts

- By Category

- Join Team Tomorrow

Every child deserves the opportunity to learn.

Save the Children works in the United States and around the world to reach those children who are missing out most on learning and education.

We help children get ready for kindergarten and learn to read by third grade — a major indicator of future success. We’re especially focused on reaching vulnerable children in rural America where early learning resources are scarce. Globally, we ensure that no child’s learning stops because they are caught up in crisis .

Your donation today supports our work to keep children healthy, educated and safe .

DONATE TODAY

Millions of children risk losing out on their education.

Hamza* has already had his access to education disrupted multiple times because of the conflict in Syria. Once his school closed due to COVID-19, he began trying to keep up learning at home.

Save the Children is a global leader in child education.

• In 2022, we helped 2.7 million children experiencing inequality and discrimination to access education through integrated measures such as cash programming, child protection case management and behavior change.

• We have delivered quality education to over 273 million children in the last decade — more than any other global development organization.

• We helped reduce the number of out-of-school children by one-third since 2000, resulting in 180 million more children getting the education they deserve.

• In rural America, we help more children get ready for kindergarten than any other nonprofit organization.

• We are working to make sure kids can learn during this crisis, with more than 300K kids served since the start of the pandemic.

Learn more about our child education programs

Global Education

U.S. Education

Learn more about our work to ensure every child has access to a quality education and is protected.

Child Protection

Girl's Education

We understand the importance of education for girl children. With your help, we can educate girls who may not otherwise have the chance to learn — changing the course of their lives, their children’s lives and the future of their communities.

Across the U.S., the poorest children tend to have the fewest learning materials at home. And millions, especially in rural areas, lack high-speed internet and the digital devices necessary for distance learning.

FIND OUT MORE

Read More News and Featured Stories

International Day of Education 2024

International Day of Education: Explore its roots, impact, and upcoming 2024 initiatives. Get involved and make a difference in education worldwide.

Take Your Child to the Library Day 2024

Discover the joy of learning and reading on International Day of Education with Take Your Child to the Library Day 2024. Learn more here.

Women Creating Change in Ethiopia, One Business at a Time

During my recent travels to the Sidama and Oromia regions of Ethiopia, I had the privilege of speaking with graduates of Save the Children’s Young Women’s Leadership and Economic E...

Sign Up & Stay Connected

Thank you for signing up! Now, you’ll be among the first to know how Save the Children is responding to the most urgent needs of children, every day and in times of crisis—and how your support can make a difference. You may opt-out at any time by clicking "unsubscribe" at the bottom of any email.

By providing my mobile phone number, I agree to receive recurring text messages from Save the Children (48188) and phone calls with opportunities to donate and ways to engage in our mission to support children around the world. Text STOP to opt-out, HELP for info. Message & data rates may apply. View our Privacy Policy at savethechildren.org/privacy.

Advertisement

Reflections on Project Work in Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Published: 03 February 2022

- Volume 51 , pages 407–418, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Mary Donegan-Ritter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3351-1590 1 ,

- Betty Zan 1 &

- Allison Pattee 1

755 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Project approach allows early childhood teachers to use both child-initiated and teacher-facilitated instructional methods. This article describes what we learned from a study focused on project approach professional development for early childhood teachers who later served as mentor teachers during a field experience for an introductory methods course. The mentor teachers saw their role as guides and supports for early childhood preservice teachers who were placed in teams in their classrooms to implement project approach. Interviews with mentor teachers and document reviews of preservice teacher reflection papers reveal that preservice teachers gained understanding about how child engagement can be fostered through project work and the importance of working as a team. Mentor teachers wanted university faculty to take a more active role in supporting team communication, make visits to the classroom and situate project work in a field experience with enough hours to get to know the children and fully develop each phase of the project. Implications for early childhood teacher educators seeking to incorporate project work in preservice field experiences are shared.

Similar content being viewed by others

Professional Experience and Project-Based Learning as Service Learning

Teachers’ Role in Students’ Learning at a Project-Based STEM High School: Implications for Teacher Education

Judith Morrison, Janet Frost, … Brian French

Teaching Beyond the Classroom: A Project-Based Innovation in a Language Education Course

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since 1987, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) has led the field of early childhood education in the U.S. in defining what it means for early childhood educators to teach in ways that respect the unique developmental, individual, cultural, and linguistic needs of young children through position statements on developmentally appropriate practice (Bredekamp, 1987 ). Revisions issued roughly every decade (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997 ; Copple & Bredekamp, 2009 ; NAEYC, 2020 ) reflect the most up-to-date knowledge, understanding, and research. One of the guidelines in the most recent position statement is “Teaching to Enhance Each Child’s Development and Learning.” Included under this guideline is the statement that teachers need to create experiences for young children “that are cognitively and creatively stimulating, invite exploration and investigation, and engage children’s active, sustained involvement.” (NAEYC, 2020 , n.p.). NAEYC has also created a position statement concerning the professional preparation of early childhood (EC) teachers (NAEYC, 2019 ). Teacher education programs are guided to prepare early childhood teachers to use both child-initiated and teacher-facilitated experiences that are developmentally appropriate, meaningful, and challenging for young children, including those with special needs and cultural and linguistic diversities.

We are two full time early childhood (EC) education faculty members and one part-time faculty member who also serves as the director of a campus-based childcare center at a regional comprehensive university. For many years, we have been engaged in an ongoing process of preparing preservice teachers to support children’s inquiry. Several years ago, we identified project-based learning as exemplified by Helm and Katz ( 2016 ) as another way to guide our efforts to support EC preservice teachers in learning how to create and implement authentic, play-based, inquiry-focused learning experiences for young children. When we began to plan how to accomplish this in our students’ field experiences, we quickly realized that we would need cooperating teachers who shared our vision for engaging young children in project-based learning. We thought that field experiences in classrooms in which teachers engage young children in project work might offer a promising avenue for introducing preservice teachers to inquiry-based curriculum and interest-based learning, and that those teachers could provide us with a valuable perspective.

Our purpose in writing this paper is to describe our process and share the lessons we gained. We examined the following questions: (1) What are the experiences of mentor teachers in using project approach in their classrooms? (2) What is the role of the mentor teachers as preservice teachers implement project work in their classrooms? (3) What are benefits and challenges for preservice teachers using project work in early childhood classrooms?

We begin by briefly reviewing the project approach (Helm & Katz, 2016 ) and its use in inclusive early childhood settings and review the literature examining project work in early childhood teacher education. We review the central role of high-quality field experiences and the need to partner with cooperating teachers, followed by a review of research on the use of project work in EC teacher education. We then report on our efforts with five cooperating or mentor teachers who agreed to explore with us the incorporation of project approach in a field experience connected to an introductory methods course (for the purposes of this paper, we refer to these teachers as mentor teachers). We describe the professional development provided to mentor teachers, the changes that we made to an early childhood methods course, and how we redesigned our field experiences in order to incorporate project work. We share the reflections of the mentor teachers and the EC students they mentored. We conclude with what we learned that we hope may inform and guide EC teacher educators seeking to incorporate project work into field experiences. We use the terms project-based learning , project work , and the project approach interchangeably in this paper to refer to the approach in which teachers support young children to investigate topics in depth and over extended periods of time.

The Project Approach in Early Childhood Education

Internationally, there are a broad range of settings in which early childhood education and preparation take place (Hoot et al., 2016). Diverse curriculum approaches from abroad have inspired and influenced US early childhood education leaders to study how emergent project-based curriculum can be adapted for US programs. Although we draw heavily on the work that Helm and Katz ( 2016 ) have done in this country, we recognize that project-based learning has a long history. Advocated by John Dewey and William H. Kilpatrick in the progressive education movement, it was prominent in progressive schools in the 1950s and in the Open Education movement in the late 1960s (Spodek & Saracho, 2003 ) and was seen as a way to integrate content across disciplinary domains. Project work is similar to the curriculum model developed at Bank Street College of Education in New York City (Zimiles, 1997 ) and the model made famous by early childhood programs in Reggio Emilia, Italy (Edwards et al., 1993 ).

Project-based learning enables children to learn in authentic and meaningful ways through extended, in-depth investigations of topics that are based on child interests and worth learning more about (Helm & Katz, 2016 ; Katz & Chard, 2000 ). In project work, children’s questions and findings determine the direction and outcomes of the project. Teachers promote higher order thinking skills (i.e., reasoning, creating, problem solving and analysis) and concept development which are associated with higher quality instructional teacher–child interactions in early childhood classrooms (Curby et al., 2009 ). Project work promotes children's intellectual development by actively engaging them in observation and investigation of topics within their experience and environment (Katz & Chard, 2000 ). As children conduct field work and collect information on topics of interest to them, the teacher takes on the role of a facilitator, planning experiences to meaningfully integrate literacy and mathematics as tools to support each phase of the investigation.

Project work in early childhood classrooms does not replace existing curriculum approaches; instead, it offers teachers an opportunity to provide more child-initiated investigations of science and social studies content than is currently found in narrow skills-based curricula. Project work can address the increasing diversity of early childhood programs and promote inclusion. In projects, children with and without disabilities engage in learning experiences at their own level to meet their physical, social, and academic goals (Harris & Gleim, 2008 ; Harte, 2010 ). Projects allow teachers to create an equitable space that encourages social interactions and participation in culturally relevant and flexible activities, promoting the effective inclusion of children with disabilities into early childhood classrooms. Meaningful experiences with rich vocabulary benefit children, especially children from low-income families and dual-language learners (Hirsch & Moats, 2001 ). Teachers report that children with special needs have benefitted from participating in project work due to the hands-on nature of activities, selection of topics based on children’s interests, use of real objects, and everyday experiences (Beneke & Ostrosky, 2009 ).

Research has found that practicing early childhood teachers can engage struggling learners and address grade-level standards through project work. (Blank et al., 2014 ; Mitchell et al., 2009 ). In a study with three early childhood teachers enrolled in a graduate course on project work, Blank et al., ( 2014 ) identified that teachers needed administrative support as well as a personal willingness to embrace uncertainty and approach project work with a spirt of inquiry. Mitchell et al. ( 2009 ) conducted a case study of a first-grade teacher who collaboratively negotiated the project focus and implementation of a project with her students while integrating standards and following children’s interests. The teacher used visual webs to facilitate decision making about how to divide teaching responsibilities between the children and the teacher.

Alfonso ( 2017 ), a teacher in an inclusive preschool in New York City, conducted a self-study of her efforts to implement child-centered inquiry through the project approach within a school culture of structured, teacher-directed learning. She reported that the children were highly motivated to engage in their own investigations and that she felt empowered by the experience. However, she also reported that the experience of moving from teacher-derived curriculum to emergent curriculum was challenging without the support of a mentor teacher to guide her through her questions and concerns.

The Role of Field Experiences and Mentor Teachers in Early Childhood Teacher Education

Advocacy for high-quality field-based experiences has dominated the conversation about improving K-12 teacher professional preparation over the last 20 years, with calls coming from the New America Foundation (Bornfreund, 2010), the Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education Programs (formerly the National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE, 2008 ), the National Research Council (NRC, 2010 ), and the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE, 2018 ). The report of AACTE’s Clinical Practice Commission (AACTE, 2018 ) states that:

Clinical practice serves as the central framework through which all teacher preparation programming is conceptualized and designed. . . . course work complements and aligns with field experiences that grow in complexity and sophistication over time and enable candidates to develop the skills necessary to teach all learners (p. 22).

The report goes on to state that clinical partnerships between P-12 schools and teacher preparation programs are “the vehicle by which the vision of renewing teacher preparation through clinical practice becomes operational” (p. 22), and that “clinical practice intentionally connects course work and field work so that teacher candidates can experience, with support, the interplay between the two” (p. 35).

The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC, 2019 ) joins these P-12 professional organizations in calling for field-based experiences in early childhood. However, providing preservice EC teachers with high-quality field experiences in EC is beset by a host of challenges. As Frances O’Connell Rust writes in the forward to the Handbook of Early Childhood Teacher Education (Couse & Recchia, 2016 ), early childhood teacher education is complex, spanning infancy, toddlerhood, preschool, and the early primary grades. The wide variety of settings, the diversity of education and credentialing of the teachers in these settings, the difficulty in identifying high-quality placements, and the limited university resources for supervision are barriers to high quality field experiences (La Paro, 2016 ).

Little research has been conducted on field-based experiences specifically in EC teacher education (Baum & Korth, 2013 ; La Paro, 2016 ). Baum and Korth ( 2013 ) addressed the issue of the skill levels of EC cooperating teachers by conducting a survey of 62 EC teacher preparation programs across the U.S. They report that although almost all (95%) of the programs that responded rated training and support of cooperating teachers extremely important or very important and none rated it unimportant , only 28% reported that they provided cooperating teachers with any sort of training. Reported barriers to providing cooperating teachers with training on how to mentor preservice teachers included lack of funding, logistics, lack of control over professional development efforts, and selection of cooperating teachers.

Maynard et al. ( 2014 ) conducted a study of how early childhood preservice teachers describe their field-based experiences following a 12 week, 72 hour placement in an early childhood classroom enrolling infants, toddlers, preschool or kindergarten age children, which was part of methods courses. A qualitative inquiry of 34 students using interviews, journal writing and open-ended questions was conducted. Results indicate that communication in the form of questions, feedback, and advice contributed to preservice teachers feeling valued. Preservice teachers benefitted from receiving both support and freedom to focus on children and connect to course content.

Project Work and Early Childhood Teacher Education

Although not widespread, project work has been used as a vehicle for inquiry in EC teacher education. Moran ( 2007 ) conducted a study in which project work was used with 24 preservice teachers in an early childhood methods class. The preservice teachers worked in teaching teams consisting of three to four students to implement a project with a small group of preschoolers over the course of 6 weeks. The collaborative projects allowed the preservice teachers and children to socially construct knowledge within the shared experience of project work. Case studies of two of the teaching teams showed changes in the preservice teachers’ orientation to inquiry-based teaching, including increased awareness of the value of collaboration and shared responsibility in making curricular decisions, early efforts at reflection-in-action, and use of documentation to demonstrate and make visible children’s learning.

Eckhoff (2017) conducted a study of 42 EC preservice teachers who were engaged in project work around a life-science project over 6 weeks as part of their 11-week EC science methods class. The preservice teachers worked with two classrooms of kindergarten children and two mentor teachers in a university professional development school. Eckhoff found significant gains in the preservice teachers’ understanding of inquiry-based science and science teaching efficacy.

Although mentor teachers play an important role in early childhood preservice teachers implementing project work in field experiences, they are largely missing from the limited research on project work in EC teacher education. Wastin, an early childhood preservice teacher and Han (a teacher educator) conducted an action research study (Wastin & Han, 2014 ) as the preservice teacher implemented a project on rain and the water cycle in a kindergarten classroom. Reflecting on the experience, the authors concluded that the success of the action research project and the experience for the preservice teacher were influenced positively by the mentor teacher’s flexibility, encouragement, and willingness to give the preservice teacher freedom to lead discussions and activities.

Young children benefit when early childhood teachers plan learning experiences and interact to promote executive functions, encourage reasoning and problem solving, and create emotionally positive, structured and stimulating classroom environments (Vandenbroucke et al., 2018 ). Classrooms that provide these high quality field experiences for preservice teachers can be difficult to locate across all early childhood age groups (NAEYC, 2009). In part, this may be due to the current mismatch between the context of today’s increasingly standards-driven schools and educator preparation programs striving to prepare preservice teachers to develop inquiry-based approaches that embrace uncertainty or dilemma (Blank et al., 2014 ). The past two decades have shown an increasing investment in publicly funded prekindergarten with accountability tied to standards that specify what children should know and be able to do (Graue et al., 2017 ). The use of packaged curriculum materials and scripted curricula creates a tension between early childhood teacher education programs that promote a child-centered focus on interest-based learning and field experience classrooms that are more teacher-led, due in large part to academic escalation (Brown & Feger, 2010 ; Graue, 2008 ; Hatch, 2002 ). Preservice teachers are aware of the challenges to using inquiry-based approaches in contemporary classrooms (Eckhoff, 2017 ). Brown and Feger ( 2010 ) conducted a case study of three early childhood preservice teachers to explore how high stakes reforms affected their conceptions of themselves as teachers. The preservice teachers reported wanting to make learning meaningful, avoid teaching to the test, and minimize the impact of reform in their teaching.

Our early childhood teacher education program is part of a comprehensive regional university located in the United States in a small mid-western metropolitan area of approximately 100,000 people. The unified early childhood teacher education program prepares undergraduate students for state licensure to teach young children from birth to third grade, with an emphasis on teaching all children in inclusive settings. EC majors complete at least 100 hours of field experience with infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and primary-grade children in diverse programs prior to student teaching. Although we had strong relationships with local schools for field experiences, limited opportunities were available for preservice teachers to observe or participate in early childhood classrooms in which children were engaged in project work because few mentor teachers possessed the skills and confidence to do project work.

To address this need, the lead author applied for and received a university Summer Enhancement Fellowship for a project, Professional Development Partnership to Support the Implementation of the Project Approach in Preschool Classrooms . Sixteen local early childhood teachers were recruited from two area school districts, a campus childcare center, and a private preschool in which we placed students for field experiences. The grant covered the cost of planning and teaching the course and providing follow up classroom-based coaching in the fall. All teachers volunteered for the professional development (PD), and received low-cost licensing renewal credit for participating. (See Table 1 for Project Timeline.)

During the summer, a teaching team of two early childhood faculty and two doctoral students planned and conducted a one-week workshop on incorporating project work into early childhood classrooms. In the weeks before and following the workshop the participants were assigned to read the book Young Investigators (Helm & Katz, 2016 ) and engage in online discussions facilitated by the lead instructor. Follow-up PD carried over into the fall when participants implemented their first project in their own classroom. The university teaching team supported each teacher through on-site coaching meetings. In November, a showcase took place on campus in which participants gathered to present the documentation on their projects to each other and early childhood faculty.

Two EC teacher educators (the second and third authors) made changes to the introductory methods course, Early Childhood Curriculum Development and Organization, in order to include a project-based component. The existing course emphasized integrated curriculum and the value of play, and included a 15-hour field experience. Although project work was addressed through assigned readings, videos, and lectures about the nature of project work, students were not able to actually implement a project due to having other curriculum related assignments in their field experience; instead, they designed a hypothetical project. The instructors revised the course to put more emphasis on project work in both the university classroom and the 15-hour field experience and integrated curriculum areas into the project.

For the 15-hour field experience, the preservice teachers were grouped into teams of 3–4 students and assigned to one of the mentor teachers who participated in the PD the previous summer. The intent of the teams was to collaborate and build a team approach to implementing a project in their classroom and to create a presence of multiple days a week focusing on the project. Bi-weekly summary reports were expected to be shared with the university faculty, mentor teacher, and group members. Each student attended their field experience one day/week for 10 weeks, meaning that each team would have a presence in the classroom 3–4 days a week implementing discussions, activities and experiences that centered on topic selection and project implementation.

Preservice teachers spent the first 2–3 weeks in the classroom interacting with children during center time to develop relationships. Phase 1 of the project was identifying children’s interests that would be possible project topics. After a possible topic was selected and discussed with faculty, a plan was outlined and discussed to explore the topic as a viable interest. Students were expected during this time period to explore interests by conversing with the children about what they knew about the topic and might want to investigate as well as bringing in books and other materials related to the topic. Preservice teachers were then instructed about anticipatory webbing as a group of teachers and webbing with children to help identify children’s questions and narrow down a focus for the project. During this phase of topic selection, the preservice teachers were expected to engage in discussions, observe closely, and listen deeply to children’s ideas.

Phase 2, implementing the project, required that students communicate with each other and arrange to bring in an expert or plan a field site visit, bring in resources, plan for ways to integrate project across curriculum areas, making connections and completing course assignments on art and literacy.

Phase 3, the culmination, involved preparing for how they might summarize the project work that the students completed during their 10 weeks. Culminating the project could take the form of a slide show, documentation board, or classroom book to help preservice teachers plan ways for sharing the project work with the classroom, parent, and school community.

In the following section we describe how we conducted a study with mentor teachers who used project work in their classrooms, seeking their experiences with project work and their perspectives about their role facilitating project work with preservice teachers. We describe how the mentor teachers supported preservice teachers, the challenges both the mentor and preservice teachers faced, and their recommendations to our EC teacher education program to enhance the field experiences. The perspectives of preservice teachers about what they learned from their field experience using project work are shared. Our guiding questions were: (1) What are the experiences of mentor teachers in using project approach in their classrooms? (2) What is the role of the mentor teachers as preservice teachers implement project work in their classrooms? (3) What are benefits and challenges for preservice teachers using project work in early childhood classrooms?

Methodology

Participants.

Five participants in the summer Project Approach PD agreed to serve as mentor teachers for 15 undergraduate preservice teachers enrolled in the early childhood methods course described above. The teachers taught in three different preschool programs: two programs based in public schools and one campus-based childcare program. The teachers were White, female, and had between 7 and 25 years of teaching experience with young children. All possessed master’s degrees in early childhood education or early childhood special education. Two of the teachers worked for a school district that was engaged in PD on project-based learning to teachers in the elementary and upper grades. Two teachers worked in a pre-k through grade 5 building in which a kindergarten classroom was involved in a pilot study implementing project-like investigations. One teacher worked for the campus childcare center in which the director (the second author) had advanced training in project work and encouraged her staff to use projects in their classroom curriculum.

Data Sources

There were two primary sources of data for this study: interviews with each of the mentor teachers and student reflections.

Teachers who participated in the PD on project work and who had served as mentor teachers were contacted via email by the first author requesting their participation in the interviews. The first author interviewed each teacher after school for 30–45 minutes using a semi-structured interview protocol. The interviews were audio-recorded and immediately transcribed for content analysis. A semi-structured interview protocol was developed for the teacher interviews and can be found in Table 2 .

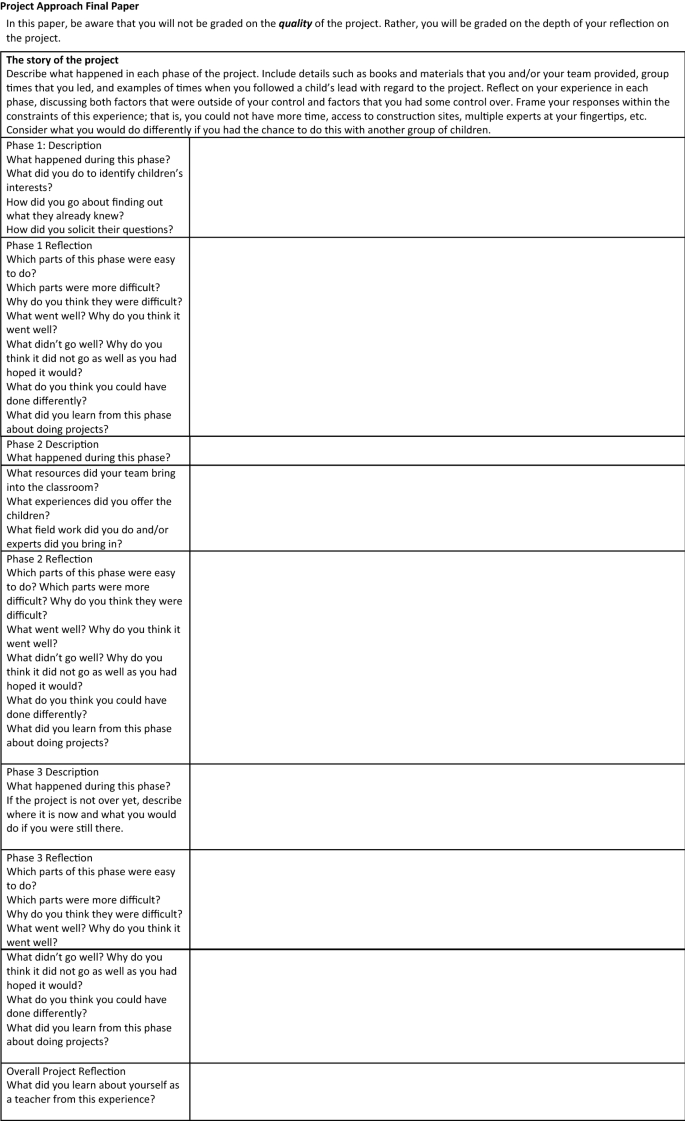

Student Reflections

The preservice teachers were assigned to work with one of the five teachers, working in groups of approximately 3–4 students, to complete their field experience. All the preservice teachers were White, female, third-year students majoring in early childhood education and only one had prior experience with project work. The instructors assigned each preservice teacher a Project Approach Final Paper in which they described what took place and reflected on their experience during each phase of the project. The final paper questions (see Fig. 1 ) required each student to describe what happened in each phase of the project, and to reflect deeply on their experience in each phase, discussing both factors that were outside of their control and factors that they had some control over. In the final paper, they were asked to write a response to “What did you learn about yourself as a teacher from this experience?”.

Project approach final assignment

Following each interview, the interviews were transcribed and the lead author read and re-read the transcripts, coding the transcripts according to our guiding question and identifying themes that emerged across the interview data. An exploratory content analysis was conducted in which an initial set of themes was generated (Creswell, 2007 ). Each interview was content analyzed by the first and second author through an iterative process in which similar codes were collapsed and emerging themes were identified. The third author read the transcripts and reviewed the themes serving the role of peer de-briefer to confirm, clarify, and question the themes (Lincoln & Guba, 1985 ). In the final stage of our study, the students’ written responses were de-identified and content analyzed by the first and second author to identify and verify the extent and the ways in which the preservice teachers perceived the role of the mentor teachers.

Our analysis of the interviews and student reflections revealed both benefits and challenges of using project work. Our discussion is centered around our three guiding questions: (1) What are the experiences of mentor teachers in using project approach in their classrooms? (2) What is the role of the mentor teachers as preservice teachers implement project work in their classrooms? and (3) What are benefits and challenges for preservice teachers using project work in early childhood classrooms? We share quotes that exemplify themes we heard from several participants.

How Mentor Teachers Used Project Work

Four of the five mentor teachers used project work in their classrooms following the PD, and they reported that this was due to their principals recently setting an expectation that the preschool teachers do projects once or twice a year. Topics that the teachers identified for projects included farms, bees, veterinarians, worms, snow, and water movement. They found the projects were useful in assessing child learning, particularly in the areas of literacy, science, social skills, and persistence. The main benefit they identified was that following child interest resulted in a deeper level of engagement. Echoing the reflections of Alfonso ( 2017 ) about how motivated and engaged her students were when implementing project work, one teacher explained:

I really feel the best thing is the kids are so engaged and so involved. I've seen kids who would never go to the art center but (during a project) made 10 observational drawings in one day of a snow blower and take those drawings and pictures and construct a snow blower. So just really using their interests and what they're interested in, to have them want to do things that they don't typically want to do…. And to them it's fun. I just think the engagement piece is the biggest thing.

Challenges identified by the mentor teachers were consistent with the findings of Blank et al. ( 2014 ). Teachers described not being able to plan ahead and the project going in unexpected directions, which resulted in them having to gather materials on short notice. Limited funding for transportation resulted in two teachers having to forego field work and instead locate experts to come into the classroom. One teacher did not do any project work on her own after the workshop, preferring to continue to use theme-based planning. She cited the stress and challenge of planning emergent curriculum, extra effort needed to get resources, and need for more training.

Roles of Mentor Teachers During Preservice Teacher Projects

The most frequently identified role that mentor teachers took was guiding preservice teachers in selecting topics that were worthwhile and appropriate for project work. Their knowledge of the children and their experience doing project work was invaluable to the preservice teachers who were still getting to know the children and had limited time in the classroom. Some of the mentor teachers shared their resources such as books, construction materials, and ideas for experts with the preservice teachers. Other mentor teachers limited their support to topic selection and left the rest to the students. Similar to findings of Maynard and colleagues ( 2014 ), we learned that support and freedom are both essential to early field experiences. In this study, encouragement and supportive feedback and willingness to answer questions were frequently cited by both the mentor teachers and preservice teachers. As Wastin and Han ( 2014 ) describe the implementation of project work during a field experience, “the importance of having a mentor teacher who is in support of this endeavor” (p. 10) is key. One mentor teacher described her support this way:

After choosing a project topic I gave them ways they could implement it into many different areas of the room and tie it in with our objectives. I have offered books, games and observational drawing, manipulatives and suggested field work locations, expert visitors and ideas for activities.

The preservice teachers confirmed that mentor teachers taking an active role in keeping the project going and giving ideas for curriculum integration were helpful to their project success.

We used our mentor teacher as a resource. She was able to tell us whether or not our ideas would be something these students would be able to participate in. I learned that using people with more knowledge and experience is important.

Mentor teachers expressed uncertainty about their role and how much support or direction to give the students. The mentor teachers realized that many of the preservice teachers’ schedules were busy and the field experience time in classroom was limited. Some of the preservice teachers had not developed a mode of communication that worked for all group members on the team. Because the mentor teachers were the constant in the classroom, they expressed a desire for more communication with the teacher educators and among the preservice teachers assigned to their classroom. The mentor teachers served a critical role in team communication and project continuity.

Benefits for Preservice Teachers

The most frequently cited benefit for the preservice teachers from doing project work was gaining experience communicating and collaborating with other adults including the mentor teacher and group members. As one preservice teacher wrote:

I learned that communication is KEY. Whether it is communication with other group members, teachers, or students it is important to always communicate your thoughts.

And another explained,

Another thing that I learned about teaching is that it is helpful to work on a ‘team.’ Many teachers today, within the same grades, work together each week on planning the curriculum. It was beneficial to me to collaborate with others to have multiple ideas and support from one another while working on the project approach. This showed me a glimpse of what teaching will be like for me.

Recognizing time constraints and identifying possible options for communicating via email, text, or a notebook is needed to promote ongoing communication between preservice EC teachers and mentor teachers in field experiences (Maynard et al., 2014 ).

Facilitating child-initiated learning was identified by a few preservice teachers as a benefit to learning to do project work. These preservice teachers realized that developing the ability to follow child interests requires flexibility and perspective taking. One mentor teacher pointed out that the rich and engaging learning that took place during the project served as a management tool. Later in their program the preservice teachers would revisit the ideas that the best guidance is a good curriculum. Their experience with deeply engaging children in project work illustrated this common wisdom.

Challenges for Preservice Teachers

Two teams of preservice teachers struggled with an assignment to use visual webbing with children to help plan their possible topic as well as learn more about the children’s questions. Webbing during phase 1 of project work requires considerable prompting (Wastin & Han, 2014 ) including asking open-ended questions, listening deeply, and summarizing main ideas, all of which were new skills for these preservice teachers. In their reflections, some described that the children were not focused on their questions, and it was the mentor teacher who helped them realize that the difficulty was likely due to them trying to web with children during a time in which the children were more interested in playing. How arrangement of the physical environment contributes to engagement was made clear to them when the mentor teacher recommended that they consider taking a small group of children to a quiet area to minimize distractions.

I thought webbing was the most difficult part of this phase. It was very hard to get questions out of the children. I did this during center time, so the children were very distracted and didn’t really care to talk to me. It was like pulling teeth trying to get some of them to focus on me and what I was asking of them. …This became very frustrating. I think webbing was difficult because the children didn’t care to talk because they were so interested in the brand-new center that was just set up. For the most part I think they just had too many distractions to focus on me or what I was asking.

Other preservice teachers who saw evidence of webbing by the mentor teachers in the classrooms for previous projects found it useful for planning with the other team members to consider possible directions the project might go, assessing children’s prior knowledge, identifying misconceptions, and documenting new knowledge and understandings.

I learned that (anticipatory) webbing as a teacher and webbing with the students is really beneficial and gives you a starting point of what to focus on and what to do with the children to make the project, or any lesson, successful and tied in to the project that you are focusing on throughout. I think that I will definitely use this through my teaching career in learning about things to do with the children.

The preservice teachers faced a time crunch to implement all the phases of a project during their field experience. Most of the preservice teachers identified not having enough time to implement phase three, culmination of the project. In response, the teacher educators adapted the assignment to include written reflections on what they would have done if they had had enough time. Interestingly, two of the mentor teachers extended the preservice teachers’ projects and planned a culminating experience.

In this reflection on our practice of incorporating project work into an early childhood methods course, we focused on the experiences of the mentor teachers in facilitating project work with preservice teachers and children in early childhood classrooms. We viewed the mentor teachers as the infrastructure that was needed to redesign the field experience in which project work was part of the methods course. Here we reflect on the lessons we learned and what we see as implications for early childhood teacher educators who want to use project work as a way to promote inquiry learning with their preservice teachers.

Lessons Learned

The change to using project work, a child-initiated inquiry approach, during field experience led to uncertainty among the mentor teachers concerning their role. The mentor teachers were accustomed in the past to taking more of a hands-off role with the preservice teachers from this particular methods class. The mentor teachers recommended greater clarity about what they were expected to do. They also reported that they wanted a better sense of what the preservice teachers were learning in the university course, along with a timeline of when different aspects of the Project Approach were being addressed. Project work, like other inquiry approaches, requires support and communication between teacher educators and mentor teachers. We realized that the mentor teachers need support, both as teachers and learners (Whitebook & Bellm, 2013 ). A few mentor teachers wanted the teacher educators to visit the preschool classroom and observe the project work in action. These findings suggest that early childhood teacher educators who want to introduce authentic experiences with project work must be prepared to devote more time to communication and consultation with the mentor teachers.

The preservice teacher teams struggled with finding ways to communicate with each other and the mentor teacher on a regular basis. Some relied on the mentor teacher to find out what took place while they were not in the classroom. Although it was expected that the preservice teachers would inform the teacher and their teammates about what took place and next steps, frequent breakdowns in communication occurred. One mentor teacher recommended the teams set up a google doc to manage their communication and project directions and findings. The consistent finding that preservice teachers struggle with communication in field experiences (Maynard et al., 2014 ) suggests that teacher educators be intentional and deliberate about their expectations concerning ongoing communication with mentor teachers and among team members.

Implications for Early Childhood Teacher Educators

The preservice teachers’ discomfort with leading discussions with children and constructing webs suggests that teacher educators provide a variety of experiences to support child-initiated learning throughout the teacher education program. These might take the form of university classroom activities in which preservice teachers engage in role plays of leading discussions and then debrief about what they learned, observing mentor teachers using webbing during group discussions with children, or watching a video of an experienced teacher interacting with children and identifying contributing factors like questions asked, environmental arrangement, and other strategies for digging deeper into children’s thinking (Helm, 2015 ).

Those early childhood teachers who take on the role of mentor teachers do so out of a sense of professional obligation and desire for growth, and those who do not cite a lack of confidence as a barrier (Walkington, 2005 ). Our experience with incorporating project work into preservice field experience reminded us that mentor teachers require support and ongoing communication from us on what is expected from them and from the preservice teachers. Strengthening connections to the university classroom can take a variety of forms including in-person classroom visits from teacher educators, web-based tools for team communication, and debriefing meetings between mentor teachers and preservice teachers and teacher educators using video conferencing tools.

Reflection Leads to Change

The question in our minds evolved over time from not whether project work could be used to prepare future teachers for facilitating child-initiated learning but at what point in the preservice experience would it be most feasible and effective. Interestingly, one of the mentor teachers asked if we considered moving project approach into the second early childhood methods course that preceded student teaching. In our preservice program we have two field experience opportunities prior to student teaching: the introductory methods course with a 15-hour field experience over 10 weeks and a pre-student teaching experience that is 40 hours over 10 weeks. Due to the frequently cited lack of time to complete all three phases of the project, we followed the mentor teacher’s suggestion and began incorporating project work into the 40-hour field experience that accompanies the more advanced early childhood methods course. This change made it possible for project work to be addressed throughout our teacher education program. The 40-hour field experience allows time preservice teachers to determine children’s interests and prior knowledge, more fully develop all three phases, and engage in authentic assessment tied to learning standards.

We found that project work enhanced our early childhood teacher education program. However, it required teacher educators to communicate more frequently and work in collaboration with both the mentor teachers who provided ongoing support and the preservice teachers, to ensure continuity across the phases of project work. La Paro ( 2016 ) used Bronfenbrenner’s expanded system theory to consider how preservice teachers are influenced by the interactions they have with early childhood coursework, learning opportunities in the field experiences, and the expertise of mentor teachers.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study has limitations because it was conducted with a small group of White teachers in an early childhood program leading to unified teacher licensure which may contribute to a lack of generalizability across EC teacher education programs. Our sample size was small and our participating mentor teachers worked in schools lacking in the richness of cultural and linguistic diversity.

Future steps for research are to examine the extent to which project work in an early childhood teacher education program carries over to preservice teacher’s future classrooms, ways to enhance the inclusion experience preservice teachers plan for children with diverse abilities during project work, and whether preservice teachers working alone, in pairs, or a small group impact the benefits of implementing project work. Identifying how higher education faculty can provide training for mentor teachers in order to enhance their professional development and strengthen partnerships to support the growth of preservice teachers are needed.

As we learned in this study of our practice, the role of the mentor teacher in facilitating the development of each phase of the project is essential. With collaborative support from teacher educators, mentor teachers are an important influence for preservice teachers who are developing skills in being part of a team and using projects as a curriculum approach for child-initiated learning.

Alfonso, S. (2017). Implementing the project approach in an inclusive classroom: A teacher’s first attempt with project-based learning. Young Children, 72 (1). Retrieved from http://www.naeyc.org/publications/vop/implementing-inclusive-classroom

American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education. (2018). A pivot toward clinical practice, its lexicon, and the renewal of educator preparation. Retrieved from https://aacte.org/resources/research-reports-and-briefs/clinical-practice-commission-report/

Baum, A. C., & Korth, B. B. (2013). Preparing classroom teachers to be cooperating teachers: A report of current efforts, beliefs, challenges, and associated recommendations. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 34 (2), 171–190.

Article Google Scholar

Beneke, S. & Ostrosky, M. M. (2009). Teachers' views of the efficacy of incorporating the Project Approach into classroom practice with diverse learners. Early Childhood Research & Practice , 11 https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ848843.pdf

Blank, J., Damjanovic, V., DaSilva, A. P. P., & Weber, S. (2014). Authenticity and “standing out”: Situating the Project Approach in contemporary early schooling. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42 , 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0549-2

Bredekamp, S. (Ed.) (1987). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8 . National Association for Education of Young Children.

Bredekamp, S., & Copple, C. (1997). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs (Revised Edition). National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Brown, C. P., & Feger, B. S. (2010). Examining the challenges early childhood teacher candidates face figuring their roles as early educators. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 31 , 286–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2010.523774

Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8 . National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Couse, L. J. & Recchia, S. L. (Eds.) (2016). Handbook of early childhood teacher education. Routledge.

Creswell, J. (2007). Data analysis and representation. In J. Creswell (Ed.), Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed., pp. 179–212). Sage.

Curby, T. W., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Konold, T. R., Pianta, R. C., Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Bryant, D., Clifford, R., Early, D., & Barbarin, O. (2009). The relations of observed pre-k classroom quality profiles to children’s achievement and social competence. Early Education and Development, 20 (2), 346–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280802581284

Eckhoff, A. (2017). Partners in inquiry: A collaborative life science investigation with preservice teaches and kindergarten students. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45 , 219–227.

Edwards, C., Gandini, L., & Forman, G. (1993). The hundred languages of children . Ablex Publishing.

Google Scholar

Graue, E. (2008). Teaching and learning in a post-DAP world. Early Education and Development, 19 (3), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280802065411

Graue, M. E., Ryan, S., Nocera, A., Northey, K., & Wilinski, B. (2017). Pulling preK into a K-12 orbit: The evolution of preK in the age of standards. Early Years, 37 (1), 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2016.1220925

Harris, K. I., & Gleim, L. (2008). The light fantastic: Making learning visible for all children through the Project Approach. Young Exceptional Children, 11 (3), 27–40.

Harte, H. A. (2010). The project approach: A strategy for inclusive classrooms. Young Exceptional Children, 13 (3), 15–27.

Hatch, J. A. (2002). Accountability shovedown: Resisting the standards movement in early childhood education. Phi Delta Kappan, 83 (6), 457–462.

Helm, J. K. (2015). Becoming young thinkers: Deep project work in the classroom. Teachers College Press.

Helm, J. H. & Katz, L. (2016). Young investigators: The project approach in the early years. (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Hirsch, E. D., & Moats, L. (2001). Overcoming the language gap. American Educator, 25 (2), 4–9.

Katz, L. & Chard, S. (2000). Engaging children's minds: The project approach (2nd ed.). Ablex.

La Paro, K. M. (2016). Field experiences in the preparation of early childhood teachers. In L. J. Couse & S. L. Recchia (Eds.), Handbook of early childhood teacher education (pp. 209–223). Routledge.

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Maynard, C., La Paro, K. M., & Johnson, A. V. (2014). Before student teaching: How undergraduate students in early childhood teacher preparation programs describe their early classroom-based experience. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 35 (3), 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2014.936070

Mitchell, S., Foulger, T. S., Wetzel, K., & Rathkey, C. (2009). The negotiated project approach: Project-based learning without learning the standards behind. Early Childhood Education Journal, 36 , 339–346.

Moran, M. J. (2007). Collaborative action research and project work: Promising practices for developing collaborative inquiry among early childhood preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23 , 418–431.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2019). Professional standards and competencies for early childhood educators: A position statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Author.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2020). Developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) position statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Author.

National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). (2008). Professional standards for the accreditation of teacher preparation institutions . NCATE.

National Research Council (NRC). (2010). Preparing teachers: Building evidence for sound policy . Author.

Spodek, B., & Saracho, O.N. (2003). On the shoulders of giants: Exploring the traditions of early childhood education. Early Childhood Education Journal, 31 , 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025176516780

Vandenbroucke, L., Spilt, J., Verschueren, K., Piccinin, C., & Baeyens, D. (2018). The classroom as a developmental context for cognitive development: A meta-analysis on the importance of teacher-student interactions for children’s executive functions. Review of Education Research, 88 (1), 126–164.

Walkington, J. (2005). Mentoring preservice teachers in the preschool setting: Perceptions of the role. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 30 (1), 28–32.

Wastin, E., & Han, H. S. (2014). Action research and project approach: The journey of an early childhood preservice teacher and a teacher educator. Networks, 16 (2), 1–12.

Whitebook, M. & Bellm, D. (2013). Supporting teachers as learners: A guide for mentors and coaches in early care and education. American Federation of Teachers.

Zimiles, H. (1997). Viewing education through a psychological lens: The contributions of Barbara Bilber. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 28 (1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025141018392

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Curriculum & Instruction, Schindler Education Center, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, IA, 50614, USA

Mary Donegan-Ritter, Betty Zan & Allison Pattee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mary Donegan-Ritter .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Donegan-Ritter, M., Zan, B. & Pattee, A. Reflections on Project Work in Early Childhood Teacher Education. Early Childhood Educ J 51 , 407–418 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01307-4

Download citation

Accepted : 12 January 2022

Published : 03 February 2022

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01307-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Field experience

- Early childhood education

- Preservice teachers

- Project approach

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Spanish – español

Project Approach Basics

Table of Contents

How to Learn More About the Project Approach

A project is an in-depth investigation of a topic worth learning more about, usually undertaken by a group of children within a classroom. The Project Approach can be a useful addition to the curriculum because it capitalizes on children’s natural interest and motivation and the satisfaction that comes from being an expert on a topic. Unlike many teacher-initiated components of the curriculum, the goal of a project is for children to learn more about a high-interest topic, rather than to find right answers to questions posed by a teacher. A typical project lasts about six to eight weeks.

Project work provides the children in the class with a common focus, which supports the inclusion of diverse learners and the development of class community. It supports children in using their strengths to make contributions that benefit others and provides teachers with opportunities to differentiate instruction to support children’s full participation.

Every group of children is unique, and therefore every project is unique. However, there are certain events and strategies that are typically present in a project. For example, it is useful to think about projects as having three phases.

In Phase 1, the teacher identifies a project topic, learns what the children already know about it, and determines whether there is sufficient interest to support a long-term investigation.