Home — Essay Samples — Entertainment — Alfred Hitchcock — The film ‘Psycho’ by Alfred Hitchcock

The Film ‘psycho’ by Alfred Hitchcock

- Categories: Alfred Hitchcock Film Analysis Horror

About this sample

Words: 905 |

Published: Jan 15, 2019

Words: 905 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Entertainment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1797 words

4.5 pages / 2006 words

6.5 pages / 2866 words

4 pages / 1710 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Alfred Hitchcock

Filmmakers use colours as instruments for storytelling, and visual minded directors create colour palettes almost as memorable as the films themselves. Hitchcock is not an exception. Few movies use colour palettes as brilliant [...]

Reflexivity is defined as the circular relationships between cause and effect, meaning that there is never a true cause or effect because they are interchangeable and cannot be defined. This theory of relationships is one of the [...]

History of cinema would not be comprehensive without the inclusion of Alfred Joseph Hitchcock; a director designated the name, Master of Suspense due to his significant filming career. Hitchcock worked with the German [...]

Paul Richards once remarked, "The purpose of appropriation is to see the past with fresh eyes." This statement captures the essence of how films can reshape and reinterpret historical narratives. One such example is the [...]

Alfred Hitchcock is one of those filmmakers that’s so good he has his own style and to be an element in an Alfred Hitchcock film, one would need to be: a platinum blonde bombshell, riveting plot twist, or an innocent man accused [...]

Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange is a novel pervaded by a multifaceted and intrinsic musical presence. Protagonist Alex’s fondness for classical music imbues his character with interesting dimensions, and resonates well [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Psycho

Introduction.

- Essays in Books

- Audience and Reception

- Fiftieth Anniversary Essays

- General Analysis

- Legal and Institutional Contexts

- Psycho and the Cold War

- Psychoanalytic Approaches

- Review Essays

- Sociological and Mass Communications Approaches

- The van Sant Remake

- Psycho ’s Music

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Alfred Hitchcock

- Art, Set, and Production Design

- Bernard Herrmann

- Psychoanalytic Film Theory

- Remakes, Sequels and Prequels

- Women and Film

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Dr. Strangelove

- Edward Yang

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Psycho by Robert Kolker LAST REVIEWED: 19 April 2023 LAST MODIFIED: 28 January 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0051

Psycho (1960) is an endlessly intriguing film. At the height of his powers and having made his greatest film, Vertigo , two years previously, Alfred Hitchcock tried his hand at a low-budget horror film that would be made in the manner of his popular television series. Shooting quickly, decisively, and in black and white, he wound up not with a simple horror film but with a work that reflected the darkest recesses of the 1950s and even earlier. Psycho is formally and thematically astonishing. Each scene of the first part of the film builds, in the mind of the viewer, a growing discomfort that is released in the shock of the shower murder. The rest of the film is a slow descent into the mind of a madman, into the darkness of unknowable, malevolent violence. Psycho is a shocking experience for the viewer because of its explicit (very explicit for its time) violence, and it constitutes a treasure trove for the film scholar because of its formal economy. Every camera setup and every sequence expresses the anxiety of discontent, the bubbling up of incipient and actual violence. In collaboration with graphic designer Saul Bass, Hitchcock developed an abstract grid of horizontal and vertical lines and of circles and diagonals that sets up a visual template that locks his images in place. Bernard Herrmann’s score helps push the images into the viewer’s consciousness (and unconsciousness). No wonder, then, that there is a wealth of commentary and analysis about the film, including psychoanalytic, gender, cultural, and musicological approaches, that has touched the critical nerve as much as it has the nerve of the culture at large.

Full-length studies of Hitchcock, all of which have chapters on Psycho , are not listed here. These are available in the Oxford Bibliographies article on Hitchcock . Instead, this section focuses on books devoted to the film. Anobile 1974 provides a transcription of the film, shot by shot, while Kolker 2004 collects a variety of essays about the film. Rebello 1990 is a complete history of the film’s production and reception. Thomson 2009 places the film in a cultural context, while Durgnat 2002 and Naremore 1973 provide close analysis of the film. Leigh and Nickens 1995 is a memoir of the actress’s work on the project, while Skerry 2009 provides summaries and analyses.

Anobile, Richard J., ed. Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. New York: Avon, 1974.

A complete transcription of the film with frame enlargements of every shot with accompanying dialogue.

Durgnat, Raymond. A Long Hard Look at Psycho. London: British Film Institute, 2002.

The book lives up to its title, and then some. Durgnat segments the film into its smallest narrative units. For each of these he provides frame enlargements with a summary of the action. These are in turn surrounded by a wide-ranging analysis that draws upon numerous methodologies and, even more important, on numerous other films. The result is that Psycho is put in its place in film history.

Kolker, Robert, ed. Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho : A Casebook . New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Collects a number of essays, including Brown 1994 (cited under Psycho ’s Music ), Williams 2000 (cited under Essays in Books ), and Toles 1984 (cited under General Analysis ), as well as reviews and an original essay by Kolker on the film’s visual design.

Leigh, Janet, and Christopher Nickens. Psycho: Behind the Scenes of the Classic Thriller . New York: Harmony Books, 1995.

A combination memoir and history of Leigh and the film. Her recollections of Hitchcock’s working methods and the making of the shower scene are interesting. There is also some gossip and trivia.

Naremore, James. Filmguide to Psycho. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973.

Though there have been more up-to-date histories and analyses of the film, this remains a useful, nicely written introduction to Hitchcock the auteur and Psycho as an intricate exercise in cinematic form and emotional fright.

Rebello, Stephen. Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho. New York: W. W. Norton, 1990.

A complete history of the film from inception to reception. Full of detail, well written, and definitive in terms of production history.

Skerry, Philip J. Psycho in the Shower: The History of Cinema’s Most Famous Scene . London: Continuum, 2009.

Skerry writes: “I vowed to myself that my book would be different—less jargony and abstruse. It would be about the shower scene, of course, but it would also be about me” (p. 7). Memoir, interviews with key and lesser figures in the making of the film, and an excellent visual analysis mix in a reasonable companion to the film.

Thomson, David. The Moment of Psycho: How Alfred Hitchcock Taught America to Love Murder . New York: Basic Books, 2009.

Argues that the film is an act of “insurrectionary defiance” against the film industry and audience that failed to sufficiently appreciate him. Thomson reads the film sequentially, analyzing in critical detail its actions and events. He believes that after the shower murder the film is a “concoction.” But when not trying to rewrite Psycho , this is an excellent analysis of the film and its cultural contexts.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Cinema and Media Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Accounting, Motion Picture

- Action Cinema

- Advertising and Promotion

- African American Cinema

- African American Stars

- African Cinema

- AIDS in Film and Television

- Akerman, Chantal

- Allen, Woody

- Almodóvar, Pedro

- Altman, Robert

- American Cinema, 1895-1915

- American Cinema, 1939-1975

- American Cinema, 1976 to Present

- American Independent Cinema

- American Independent Cinema, Producers

- American Public Broadcasting

- Anderson, Wes

- Animals in Film and Media

- Animation and the Animated Film

- Arbuckle, Roscoe

- Architecture and Cinema

- Argentine Cinema

- Aronofsky, Darren

- Arzner, Dorothy

- Asian American Cinema

- Asian Television

- Astaire, Fred and Rogers, Ginger

- Audiences and Moviegoing Cultures

- Australian Cinema

- Authorship, Television

- Avant-Garde and Experimental Film

- Bachchan, Amitabh

- Battle of Algiers, The

- Battleship Potemkin, The

- Bazin, André

- Bergman, Ingmar

- Bernstein, Elmer

- Bertolucci, Bernardo

- Bigelow, Kathryn

- Birth of a Nation, The

- Blade Runner

- Blockbusters

- Bong, Joon Ho

- Brakhage, Stan

- Brando, Marlon

- Brazilian Cinema

- Breaking Bad

- Bresson, Robert

- British Cinema

- Broadcasting, Australian

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer

- Burnett, Charles

- Buñuel, Luis

- Cameron, James

- Campion, Jane

- Canadian Cinema

- Capra, Frank

- Carpenter, John

- Cassavetes, John

- Cavell, Stanley

- Chahine, Youssef

- Chan, Jackie

- Chaplin, Charles

- Children in Film

- Chinese Cinema

- Cinecittà Studios

- Cinema and Media Industries, Creative Labor in

- Cinema and the Visual Arts

- Cinematography and Cinematographers

- Citizen Kane

- City in Film, The

- Cocteau, Jean

- Coen Brothers, The

- Colonial Educational Film

- Comedy, Film

- Comedy, Television

- Comics, Film, and Media

- Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI)

- Copland, Aaron

- Coppola, Francis Ford

- Copyright and Piracy

- Corman, Roger

- Costume and Fashion

- Cronenberg, David

- Cuban Cinema

- Cult Cinema

- Dance and Film

- de Oliveira, Manoel

- Dean, James

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Denis, Claire

- Deren, Maya

- Design, Art, Set, and Production

- Detective Films

- Dietrich, Marlene

- Digital Media and Convergence Culture

- Disney, Walt

- Documentary Film

- Downton Abbey

- Dreyer, Carl Theodor

- Eastern European Television

- Eastwood, Clint

- Eisenstein, Sergei

- Elfman, Danny

- Ethnographic Film

- European Television

- Exhibition and Distribution

- Exploitation Film

- Fairbanks, Douglas

- Fan Studies

- Fellini, Federico

- Film Aesthetics

- Film and Literature

- Film Guilds and Unions

- Film, Historical

- Film Preservation and Restoration

- Film Theory and Criticism, Science Fiction

- Film Theory Before 1945

- Film Theory, Psychoanalytic

- Finance Film, The

- French Cinema

- Game of Thrones

- Gance, Abel

- Gangster Films

- Garbo, Greta

- Garland, Judy

- German Cinema

- Gilliam, Terry

- Global Television Industry

- Godard, Jean-Luc

- Godfather Trilogy, The

- Greek Cinema

- Griffith, D.W.

- Hammett, Dashiell

- Haneke, Michael

- Hawks, Howard

- Haynes, Todd

- Hepburn, Katharine

- Herrmann, Bernard

- Herzog, Werner

- Hindi Cinema, Popular

- Hitchcock, Alfred

- Hollywood Studios

- Holocaust Cinema

- Hong Kong Cinema

- Horror-Comedy

- Hsiao-Hsien, Hou

- Hungarian Cinema

- Icelandic Cinema

- Immigration and Cinema

- Indigenous Media

- Industrial, Educational, and Instructional Television and ...

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers

- Iranian Cinema

- Irish Cinema

- Israeli Cinema

- It Happened One Night

- Italian Americans in Cinema and Media

- Italian Cinema

- Japanese Cinema

- Jazz Singer, The

- Jews in American Cinema and Media

- Keaton, Buster

- Kitano, Takeshi

- Korean Cinema

- Kracauer, Siegfried

- Kubrick, Stanley

- Lang, Fritz

- Latin American Cinema

- Latina/o Americans in Film and Television

- Lee, Chang-dong

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Cin...

- Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The

- Los Angeles and Cinema

- Lubitsch, Ernst

- Lumet, Sidney

- Lupino, Ida

- Lynch, David

- Marker, Chris

- Martel, Lucrecia

- Masculinity in Film

- Media, Community

- Media Ecology

- Memory and the Flashback in Cinema

- Metz, Christian

- Mexican Film

- Micheaux, Oscar

- Ming-liang, Tsai

- Minnelli, Vincente

- Miyazaki, Hayao

- Méliès, Georges

- Modernism and Film

- Monroe, Marilyn

- Mészáros, Márta

- Music and Cinema, Classical Hollywood

- Music and Cinema, Global Practices

- Music, Television

- Music Video

- Musicals on Television

- Native Americans

- New Media Art

- New Media Policy

- New Media Theory

- New York City and Cinema

- New Zealand Cinema

- Opera and Film

- Ophuls, Max

- Orphan Films

- Oshima, Nagisa

- Ozu, Yasujiro

- Panh, Rithy

- Pasolini, Pier Paolo

- Passion of Joan of Arc, The

- Peckinpah, Sam

- Philosophy and Film

- Photography and Cinema

- Pickford, Mary

- Planet of the Apes

- Poems, Novels, and Plays About Film

- Poitier, Sidney

- Polanski, Roman

- Polish Cinema

- Politics, Hollywood and

- Pop, Blues, and Jazz in Film

- Pornography

- Postcolonial Theory in Film

- Potter, Sally

- Prime Time Drama

- Queer Television

- Queer Theory

- Race and Cinema

- Radio and Sound Studies

- Ray, Nicholas

- Ray, Satyajit

- Reality Television

- Reenactment in Cinema and Media

- Regulation, Television

- Religion and Film

- Renoir, Jean

- Resnais, Alain

- Romanian Cinema

- Romantic Comedy, American

- Rossellini, Roberto

- Russian Cinema

- Saturday Night Live

- Scandinavian Cinema

- Scorsese, Martin

- Scott, Ridley

- Searchers, The

- Sennett, Mack

- Sesame Street

- Shakespeare on Film

- Silent Film

- Simpsons, The

- Singin' in the Rain

- Sirk, Douglas

- Soap Operas

- Social Class

- Social Media

- Social Problem Films

- Soderbergh, Steven

- Sound Design, Film

- Sound, Film

- Spanish Cinema

- Spanish-Language Television

- Spielberg, Steven

- Sports and Media

- Sports in Film

- Stand-Up Comedians

- Stop-Motion Animation

- Streaming Television

- Sturges, Preston

- Surrealism and Film

- Taiwanese Cinema

- Tarantino, Quentin

- Tarkovsky, Andrei

- Television Audiences

- Television Celebrity

- Television, History of

- Television Industry, American

- Theater and Film

- Theory, Cognitive Film

- Theory, Critical Media

- Theory, Feminist Film

- Theory, Film

- Theory, Trauma

- Touch of Evil

- Transnational and Diasporic Cinema

- Trinh, T. Minh-ha

- Truffaut, François

- Turkish Cinema

- Twilight Zone, The

- Varda, Agnès

- Vertov, Dziga

- Video and Computer Games

- Video Installation

- Violence and Cinema

- Virtual Reality

- Visconti, Luchino

- Von Sternberg, Josef

- Von Stroheim, Erich

- von Trier, Lars

- Warhol, The Films of Andy

- Waters, John

- Wayne, John

- Weerasethakul, Apichatpong

- Weir, Peter

- Welles, Orson

- Whedon, Joss

- Wilder, Billy

- Williams, John

- Wiseman, Frederick

- Wizard of Oz, The

- Women and the Silent Screen

- Wong, Anna May

- Wong, Kar-wai

- Wood, Natalie

- Yimou, Zhang

- Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Cinema

- Zinnemann, Fred

- Zombies in Cinema and Media

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.41]

- 185.80.151.41

- Read What TIME’s Original Review of <i>Psycho</i> Got Wrong

Read What TIME’s Original Review of Psycho Got Wrong

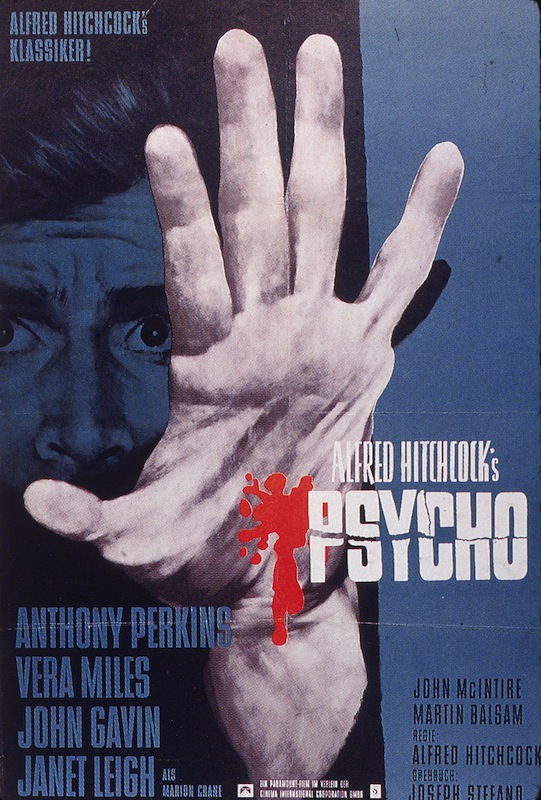

F ifty-five years after its June 16, 1960, premiere, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is firmly entrenched in the cinematic canon. It altered the suspense genre forever, it changed what can be shown on screen — in addition to the reams of blood, it was the first film to show a flushing toilet — and it set the bar for the lengths to which a filmmaker would go to avoid spoilers.

But at the time of its release, not every critic guessed at the film’s lasting influence. Among those reviewers was TIME’s, who found Psycho just a little too much:

…the experienced Hitchcock fan might reasonably expect the unreasonable—a great chase down Thomas Jefferson’s forehead, as in North by Northwest , or across the rooftops of Monaco, as in To Catch a Thief . What is offered instead is merely gruesome. The trail leads to a sagging, swamp-view motel and to one of the messiest, most nauseating murders ever filmed. At close range, the camera watches every twitch, gurgle, convulsion and hemorrhage in the process by which a living human becomes a corpse.

Though the plot (graciously unspoiled by the review) was acknowledged as “expertly gothic,” the critic warned that “the nausea never disappears.” The final result, the critic noted, is “a spectacle of stomach-churning horror”—not guessing that audiences would see that as a good thing.

Read the full review, here in the TIME Vault: Psycho

How Hitchcock Turned a Small Budget Into a Great Triumph

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at [email protected]

You May Also Like

How Hitchcock's 'Psycho' Changed Cinema and Society

A look back on the suspenseful masterpiece

50 years ago today, Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho debuted in midtown Manhattan. At its first showing, the suspenseful thriller enthralled the audience, and since then not a lot's changed. In honor of its 50th anniversary, critics are exploring how Psycho changed cinema. Read their remarks after the jump:

- It Shattered 1950s Conformity , writes Owen Gleiberman at Entertainment Weekly: "When the movie came out. It took place in an atmosphere of dark and stifling ’50s conformity, when an afternoon tryst had the musky, sinful air of secret depravity, and Marion Crane, stealing that $40,000, was like Doris Day taking a walk on the wild side. Norman Bates’ knife was the primal force that tore through the repressive ’50s blandness just as potently as Elvis had. Sure, Norman was a maniac serial killer dressed in his mother’s Victorian rags, but when he slashed that knife, he brought down a world of civilized propriety that needed to be brought down."

- Psycho Spawned the Slasher Flick, writes Adam Rosenberg at MTV: "On June 16, 1960, 'Psycho' premiered in New York City. On that night, the world saw the birth of the slasher genre and one of the earliest examples of graphic violence in film... There are many works of 'classic cinema' which, while important, seem unimpressive by today's standards. Hitchcock stands apart; his work endures and his influence is still felt whenever a movie pushes you to the edge of your seat with tension."

- Pioneered 'Quick Cutting,' writes Nate Jones at Time: "The shower scene in Psycho never actually shows most of things we think we see. (Except for two split-seconds, the knife never even touches flesh.) But through a series of quick edits -- over 90 cuts in a span of 45 seconds -- Hitchcock is able to suggest the illusion of graphic violence. Whenever an aging action star magically kicks butt in a series of quick shots, he should give thanks to Hitch."

- The Musical Score Changed Everything, writes Kevin Zimmerman at Splice: "That score’s most famous piece, the stabbing, shrieking violins that accompany the murders, has of course been an influence all its own, not least on John Williams’ Jaws theme (which the Beastie Boys memorably pointed out by juxtaposing the two on 'Egg Man'). An intriguing feature on the Psycho DVD allows you to play the shower sequence without the music; with on ly the sounds of the blade entering the flesh, it makes for a much blunter and disturbing effect."

- Rendered Previous Horror Films Obsolete, wrote Village Voice critic Andrew Sarris . The magazine republished his review from 1960: "Hitchcock is the most-daring avant-garde film-maker in America today. Besides making previous horror films look like variations of 'Pollyanna,' 'Psycho' is overlaid with a richly symbolic commentary on the modern world as a public swamp in which human feelings and passions are flushed down the drain. What once seemed like impurities in his patented cut-and-chase technique now give 'Psycho' and the rest of Hollywood Hitchcock a personal flavor and intellectual penetration which his British classics lack."

Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” Annotation Essay (Movie Review)

The plot of the movie, production and development, the shower scene, notable works, works cited.

Psycho is considered the earliest slasher movie as well as one of the best films ever created. Wood calls it “perhaps the most terrifying film ever made” (142), describing it as a movie that takes viewers into the darkness of themselves. Based on a 1959 novel by Robert Bloch, Psycho was made against the wishes of Paramount, which Hitchcock was working with at the time using his resources. As a result, the movie was shot on a low budget, using Hitchcock’s television show crew, and being filmed in black and white.

The film begins with Marion Crane, a secretary, stealing a significant sum of money and attempting to drive to her boyfriend’s house in a different state. On the way, she stops at a motel and is invited to dinner by the owner Norman Bates. She then overhears an argument between Bates and his mother about bringing Marion into the house to eat, which ends with Norman deciding to eat with her in the motel parlor. There, Norman tells Marion about his difficult life under his controlling and obsessive mother. After hearing the story, Marion has an epiphany and decides to go back and return the money the next morning.

Soon after, she is suddenly stabbed in the shower by an unknown assailant, with Bates discovering the body and hiding it along with the evidence. Marion’s relatives become alarmed at her disappearance and hire a private investigator, who is also murdered at the motel. Finally, Marion’s sister Lila and her boyfriend Sam arrive in the town themselves. There they learn that Norman’s mother, Mrs. Bates, has been dead for ten years. Deciding that Norman is the killer who wanted the money Marion was hiding, they head to the hotel.

While Sam distracts Norman, Lila manages to sneak into Bates’s house and discovers the mummified corpse of Mrs. Bates However, Norman discovers her soon after and tries to kill her, but Sam manages to subdue him. They give Norman over to the police to have him tried for his crimes. At court, a psychiatrist explains that Bates has developed dissociative identity disorder, with the violent and possessive “mother” personality completely taking charge of him. The “mother” personality protests to the viewer that Norman himself performed the murders.

Paramount disliked the idea of Hitchcock producing an experimental movie such as Psycho and refused to provide support for the filming. Hitchcock decided to fund the film with his resources, not using his usual filming crew and convincing the actors to work for less than their usual fee. The Paramount executives agreed to the proposal, as they would still be the distributors of the movie, even though Hitchcock secured a 60% stake in the earnings for himself, according to Smith (14).

Hitchcock decided to shoot the movie at the studios where he produced his television show, using the show’s crew. The movie’s budget was relatively small, but despite that, numerous locations were shot for reconstruction at the studio, and well-known, talented actors were hired (Kolker 48). There was a need to do retakes for some scenes, which is unusual for Hitchcock who is famous for only needing one attempt to film a shot successfully.

The actors were allowed to improvise freely, which accounts for some of the small details in the movie, such as Norman’s candy corn eating habit. There were rumors that Janet Leigh who played Marion was abused during the shower scene’s filming via the use of cold water to produce more realistic screams, but the actress has since publicly denied the statement. She did, however, only receive a quarter of her usual fee for her work, which was explained by a combination of Hitchcock’s reputation, her contract, and her agreement without reading the salary details.

The shower scene is the most well-known part of the movie, as it is masterfully shot and displays a level of violence that was unprecedented at the time of its shooting. According to Philippe, it consists of 78 camera set-ups and 52 edits in a three-minute sequence. Some of the angles are innovative for the time, such as the shot of the shower head spraying water onto the camera without blurring the lens. This effect was achieved through the blocking of the head’s inner ring of holes, which made the water spray around the camera without getting on the lens.

A significant part of the scene’s appeal is its meaning, which was unusual for the time and revolutionized the concept of storytelling in films. The perception that Marion is the protagonist increases the impact of the scene, as up to that point in time the viewer has been observing her actions and thoughts. However, she dies and is never relevant again, as the focus of the story shifts to the actual centerpiece, namely the unknown killer and the people who try to expose him. The approach has become standard for slasher movies, which tend to avoid showing the killer’s activity until the first murder occurs.

The scene’s use of matters that were previously considered unapproachable, such as displaying a flushing toilet, expanded the possibilities for future horror film creators, which they capitalized on. However, the scene still attempts to avoid on-screen displays of violence. While there is a shot of a knife stabbing Marion, it is so short that people often do not notice it without a freeze-frame analysis. The use of the music also serves to amplify the scene, despite Hitchcock’s original intention is not to have any.

The scene is said to contain numerous subtexts, some of which Hitchcock openly discussed after the movie’s release. The director compared Marion’s decision to shower to baptism, as she decided to confess her crime and face her punishment. Norman’s attack is also founded on deep sexual frustration, as his possessive “mother” personality refuses to let him express anything but hostility to women, and the knife Bates favors is a strongly phallic instrument.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook edited by Robert Kolker approaches the movie from different sides and viewpoints by gathering the opinions of numerous analysts, such as Robin Wood and Stephen Rebello. The topics of the book cover Psycho ’s production, reception, music, and other aspects. The book can be considered a collection of informed and influential opinions on the movie and its effect on the industry.

Robin Wood wrote an entire book on the famous director, which is named Hitchcock’s Films Revisited. The author describes his impressions of the various movies directed by Hitchcock as an individual and as a critic who has been strongly influenced by his works. The combination of objective insights and memories of how the works affected Wood when they were first displayed provides a valuable view of the intents and circumstances behind them.

For a detailed analysis of the movie’s plot from every aspect, Joseph W. Smith, III, offers a helpful guide. The book’s structure follows the movie’s progression, describing the events while noting matters that deserve attention, such as technical specifics or subtexts behind particular scenes. The book provides a detailed analysis of the motifs of the film and the ideas Hitchcock wanted to express with each scene as well as the whole story.

Alexandre O. Philippe devotes an entire feature-length documentary to analyzing the shower scene. 78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene makes a statement that there are still secrets hidden in the 78 camera shots that have not been discovered yet. The documentary describes the shocking, but also beautiful nature of the scene with its tragic and yet irresistibly attractive visuals. Philippe states that one could explore the shower scene for a lifetime and still not get to the bottom of its numerous subtexts.

David Thomson analyses Psycho as a work that has influenced the cinematographic industry for years and decades to come. His book The Moment of Psycho: How Alfred Hitchcock Taught America to Love Murder describes how the film plays with the viewers and how it breaks the norms and establishes new ones. The author covers both the individual qualities of the movie and the battle Hitchcock had fought behind the scenes to secure acceptance of his masterpiece.

Critics did not receive Psycho positively when it premiered, denouncing it for its violence and disturbing departure from the norms. Thomson describes how a similar movie Peeping Tom by another highly talented director Michael Powell had received a strong negative response three months before Psycho ’s opening and halted Powell’s career due to poor critical reception (156). Nevertheless, the film opened with great aplomb and attracted a large amount of attention from audiences despite the negative reviews.

Hitchcock’s move produced results when audiences greatly enjoyed Psycho and began spreading the fame of the picture by word of mouth. Faced with this unexpected reaction, critics were forced to watch the movie again and evaluate it with a fresh perspective. Once they did that, the tone of the reviews dramatically improved, and Psycho was hailed as a masterpiece, according to Kolker (167). A similar situation occurred in the other countries as the movie premiered there, leading to universal recognition and a theatrical re-release of the film in 1969.

The success of Psycho paved the way for other films that would previously be considered too dark or brutal. Lewis’s Blood Feast , released in 1963, became known as the first “splatter movie,” and numerous mystery thrillers took inspiration from Hitchcock’s film. After Hitchcock’s death, Universal Studios, who had acquired the rights to the franchise, began working on numerous related movies, including three sequels to Psycho. The film itself is preserved in the National Film Registry as significant.

Psycho is a brilliant film that challenged the norms of its times and emerged victoriously. It has established many standards and approaches that are being used even today. The combination of great direction, music, acting, and story creates a film that was revolutionary when it premiered but remains a highly recommended picture half a century later. With its outstanding list of achievements, Psycho is a strong contender for the title of the best movie ever filmed.

Kolker, Robert, editor. Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Lewis, Herschell Gordon, director. Blood Feast . Box Office Spectaculars, 1963.

Philippe , Alexandre O., director. 78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene. IFC Films, 2017.

Psycho . Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, performances by Anthony Perkins and Vera Miles, Paramount Pictures, 1960.

Smith, Joseph W., III. The Psycho File: A Comprehensive Guide to Hitchcock’s Classic Shocker. McFarland, 2009.

Thomson, David. The Moment of Psycho: How Alfred Hitchcock Taught America to Love Murder. Basic Books, 2009.

Wood, Robin. Hitchcock’s Films Revisited. Columbia University Press, 2002.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, June 15). Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" Annotation. https://ivypanda.com/essays/alfred-hitchcocks-psycho-film-annotation/

"Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" Annotation." IvyPanda , 15 June 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/alfred-hitchcocks-psycho-film-annotation/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" Annotation'. 15 June.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" Annotation." June 15, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/alfred-hitchcocks-psycho-film-annotation/.

1. IvyPanda . "Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" Annotation." June 15, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/alfred-hitchcocks-psycho-film-annotation/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" Annotation." June 15, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/alfred-hitchcocks-psycho-film-annotation/.

- Techniques in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho”

- Mise-En-Scene in the "Psycho" Film by Hitchcock

- Roles of Women in Hitchcock's Film

- The AutoCAD Software: Annotation and Tex

- Hitchcock and Spielberg: A Tale of Two Directors

- Fashionable Women in Alfred Hitchcock's Films

- Cinema Art: Alfred Hitchcock’s "Psycho" Suspense Film

- Philippe Starck as the Great Designer of the World

- "Rear Window" the Film by Alfred Hitchcock

- Edgar Allen Poe’s Influence on Hitchcock

- Female Character in Palma’s “Carrie” Horror Film

- “Braveheart” (1995) by Mel Gibson

- "The Greatest Showman" by Michael Gracey

- Scene Analysis from the "Deadpool" Film

- "Devdas" by Sanjay Leela Bhansali

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Greatness of “Psycho”

The cinematic man of the year, at least in prominence, is Alfred Hitchcock. Not only was his “Vertigo” named the best film of all time in the decennial Sight and Sound poll but he’s the subject of two bio-pics—“ The Girl ” (which ran on HBO last month), about the making of “The Birds” and “Marnie,” and now “ Hitchcock ” (opening this Friday), about the making of “Psycho.”

“The Girl,” directed by Julian Jarrold, has a hectic pulp briskness that’s apt to its subject (mainly, Hitchcock’s intense attraction to Tippi Hedren and the way he used his power to pursue her and, when she spurned him, to punish her), but “Hitchcock,” directed by Sacha Gervasi, is the better movie—first, thanks to Anthony Hopkins’s performance. Toby Jones, playing Hitchcock in Jarrold’s film, gets the slyness and the pain, the sophistication and the frustration, but Hopkins has the timing down better and also gives off a wilder creative drive, blending fierce energy with a loftily ironic perspective; his Hitchcock sees more and sees more clearly—and has the will to do something about it. In part, the directors’ differing approaches to the stories is responsible for the differing performances; Gervasi treats “Psycho” as the greater achievement, and he does a much better job with Hitchcock’s artistry, which he unfolds in its practical details and also—clumsily but cleverly and movingly—pursues in its inner recesses.

“Hitchcock” isn’t a great film, but it tells a great story and caps it with a couple of very fine and memorable moments—and the story it tells is one that rises from deep in the heart of the movie business and remains central to the industry today. A couple of months ago, the talk here turned to the studios—whether their emphasis on franchise films is causing a decline in the artistic quality of Hollywood movies. I don’t think so, and wrote then that the rise of independent productions gives directors a freer hand to pursue even more distinctive work (whether “Moonrise Kingdom” or “Magic Mike,” “Hugo” or “Tree of Life,” “Black Swan” or “Somewhere”). This has always been the case, as in the late forties and nineteen-fifties, when the wave of wildly original films by such directors as Nicholas Ray, Otto Preminger, Sam Fuller, and Ida Lupino were made largely by independent producers who gained sudden influence in the wake of antitrust suits.

The story of “Hitchcock” is simple: looking to strike out in a new direction after making “North by Northwest” (which, by the way, I’ve always considered one of Hitchcock’s weaker and stodgier films), he chose (on the recommendation by his longtime assistant, Peggy Robertson—played, in Gervasi’s film, by Toni Collette) Robert Bloch’s novel “Psycho.” But his studio, Paramount, refused to finance it—so Hitchcock made the movie with his own money, even mortgaging his house to do so. As it turns out (and as “Hitchcock” shows), “Psycho” made him a fortune; it was also, however, a flop with critics. In the Times , Bosley Crowther damned it with faint praise, writing that “Hitchcock, an old hand at frightening people, comes at you with a club in this frankly intended bloodcurdler”; he found it “slowly paced” and referring to its “old-fashioned melodramatics, however effective and sure.” In The New Yorker , John McCarten wrote , “Hitchcock does several spooky scenes with his usual éclat, and works diligently to make things as horrible as possible, but it’s all rather heavy-handed and not in any way comparable to the fine jobs he’s done in the not so distant past.” Pauline Kael didn’t review it (even when it ran in revival) but, in 1978, complained about it as “a borderline case of immorality… which, because of the director’s cheerful complicity with the killer, had a sadistic glee that I couldn’t quite deal with,” and she condescended to the shower scene as “a good dirty joke.”

Its great rave came from Andrew Sarris, who, in his first piece for the Village Voice , called Hitchcock “the most daring avant-garde film-maker in America today” and added:

“Psycho” should be seen at least three times by any discerning film-goer, the first time for the sheer terror of the experience, and on this occasion I fully agree with Hitchcock that only a congenital spoilsport would reveal the plot; the second time for the macabre comedy inherent in the conception of the film; and the third for all the hidden meanings and symbols lurking beneath the surface of the first American movie since “Touch of Evil” to stand in the same creative rank as the great European films. In a 2001 interview with Richard Schickel, Sarris said that this review proved controversial:

The Voice had all these readers—little old ladies who lived on the West Side, guys who had fought in the Spanish Civil War—and this seemed so regressive, to them, to say that Hitchcock was a great artist.

It’s not so controversial anymore, because the times have long since caught up with his obsessions—and with the notion of the popular as art. If anything, now inflation has set in regarding the praise of popular films as art (as with raves for “Lincoln,” “Silver Linings Playbook,” and “Anna Karenina”); critics are all too ready to extol any mass-market movie with the merest glimmer of personal concern, stylistic idiosyncrasy, or intellectual substance and to crown their directors as auteurs. One of the great changes in critical perception in the past fifty years—and perhaps in society at large—is the view of insidership; as the boundaries between pop and high culture have (rightly) fallen, a sort of populist or demagogic reversal has occurred—the desire and the ability to reach broad audiences has become a virtue in itself rather than an incidental and inconsequential artistic epiphenomenon. It doesn’t matter whether “Psycho” was a bigger hit than “North by Northwest” or whether “The Wrong Man” and “Marnie” were flops, although, of course, it mattered to the director. One of the noteworthy things about “Hitchcock” is that it illustrates how Hitchcock’s decision to work in a pulp vein was, above all, a change in artistic gears—as well as one that he thought through to its very release in order to make his investment good and turn the movie into a hit.

“Psycho” remains a demanding and disturbing movie; it conveys the thrill felt by a murderer as well as his torment, and it shows the proximity of sex—and of restrictive sexual morality—to violence. It’s ultimately an existential conundrum that blames nature itself as the source of deadly madness, and even the scene that Kael called “arguably—Hitchcock’s worst scene,” the psychiatrist’s explanation at the end—has a profound place in the schema: the doctor can diagnose and explain a phenomenon that he’s seemingly powerless to foresee or cure. There’s no redemptive ending, no love story that conquers all, no promise that such ills won’t be repeated.

Yet, for all its philosophically revelatory drama and symbolism, “Psycho” remains a movie made with Hitchcock’s own money—but not a movie about himself. The modernistic version of “Psycho” would be Hitchcock’s own story of mortgaging his house to make “Psycho”—and making clear the personal significance of the story of “Psycho.” That’s where Gervasi goes out on a shaky but bold artistic limb, presenting a strangely enticing set of scenes in which Hitchcock imagines, or is visited in dreams by, the serial killer Ed Gein, whose crimes were the basis for Bloch’s novel. Gervasi rightly suggests that Hitchcock is no mere puppet master who seeks to provoke effects in his viewers; he’s converting the world as he sees it, in its practical details and obsessively ugly corners, into his art, and he’s doing so precisely because those are the aspects of life that haunt his imagination. Gervasi had the audacity to consider the filmmaker’s realized visions to be reflections of an inner life that documented behavior hardly conveys. For Hitchcock, bloody evil and the danger of sex are a sort of music that forces itself to the fore unbidden from the depths of his being. A few others—such as his characters and their real-life models—are even more deeply in the grip of such obsessions and in less control of their behavior; millions of others, when confronted with the evidence, find the secret stirrings deep within themselves, too; it’s the difference, of course, between psychopaths and viewers, as well as the connection.

Whether something is a commercial success or not is irrelevant to its artistic merit; but, nonetheless, things succeed for reasons, and Hitchcock’s success arose from his lucid understanding that, in these obsessions, he’s far from alone. Despite critical and even medical outcries at the time of the film’s release (as in a 1960 letter to the Times from a doctor who wished that Hitchcock had self-censored), it was clear that Hitchcock tapped into ugly elements of the unconscious at a time when lots of people were ready to become conscious of them. In Gervasi’s conceit, Hitchcock is both terrified and amused by the play of his own mind (which makes sense—so are viewers). I have no idea whether Hitchcock gave very much thought to Gein, but it doesn’t matter; if it wasn’t Gein that obsessed him, it was surely much that was Gein-like.

There’s a great line from Norman Mailer to the effect that the one kind of character no novelist can conceive is a greater novelist than himself. Gervasi’s visions fall far short of Hitchcock’s phantasmagoria—but they at least suggest that the inner mysteries are there, and that Hitchcock’s art arose from much that the doughy and sybaritic ironist’s observable behavior may not, and need not, put in evidence. Hitchcock’s meticulous attention to practical details served his radical subjectivism; he didn’t hesitate to fill his films with plenty (from inner voices to dream sequences) that assert of characters what can’t be seen from fly-on-the-wall observation. Gervasi—albeit in a narrower range and slighter realization of artistic imagination—does the same, and this already puts him ahead of many.

As an object of adulation, “Vertigo” is also an object of nostalgia, an allegory for the very cinematic manipulations of the grand studio era, of which Hitchcock was a master (albeit a master in thrall). Voting it the best film of all time was also voting for classic Hollywood. “Psycho,” in its dark and sordid extravagance, remains utterly contemporary, in its subject as well as in its production.

P.S. In his biography of Rossini, Stendhal makes clear that, in the early nineteenth century, opera spectators were in the habit of wandering noisily in and out of the theatre while the production was going on. So it was with movies, as I recall from my childhood in the sixties—people went to the movies casually, not hesitating to take a seat in the midst of the movie and then staying through to the beginning of the next show to see what they missed. That now-obsolete habit gives rise to scenes in “Hitchcock” that reveal the skill of Hitchcock the showman—and make clear his deep understanding of the essential experience of cinema. He insisted that “Psycho” be watched from the start, and that no viewers be allowed into the theatre once the lights went down—and theatres screening it had to enforce these rules. There’s documentary footage, as an extra on the DVD release of “Psycho,” showing the effect of these rules: the invention of a ticket-holder’s line, separate from the line at the box-office, where viewers waited to enter the theatre at the start of the show. Next time you wait in one, remember that this, too, was Hitchcock’s doing.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Richard Brody

47 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Chapters 1-4

Chapters 5-9

Chapters 10-12

Chapters 13-15

Chapters 16-17

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Psycho (1959) is a horror novel by Robert Bloch and the inspiration for filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock’s film of the same name, which came out one year later. While Hitchcock’s adaptation has largely eclipsed Bloch’s original in the public eye, fans of the film will recognize the basic plot and the major twists in Bloch’s novel. However, Bloch’s Norman Bates is (physically) unrecognizable from the version Anthony Perkins played on screen. Psycho is a slasher thriller that evolves into a work of psychological horror as the revelations about Norman Bates’s relationship with his mother, criminal acts, and mental health condition come to light. It is important to note, however, that Psycho is a product of its time and relies on disproven approaches to mental health that are out of favor among mental health professionals and experts. Specifically, Psycho tends to correlate mental health conditions with criminal behavior, particularly violent crime, while in fact, people with mental health conditions are far more likely to experience violent crime than to perpetrate it.

This guide references the Overlook Press paperback edition, published in 2010.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,350+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,950+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Content Warning: This guide describes and analyzes the source text’s treatment of trauma, abuse, and mental health. The novel contains stigmatizing depictions of cross-dressing and an individual with a mental health condition, which relies on outdated and offensive tropes that connect mental health conditions with violence.

Plot Summary

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

Norman Bates is a timid, middle-aged man running the Bates Motel on the rural outskirts of a small town called Fairvale. Norman’s mother, Norma, is a domineering and puritanical woman who still governs Norman’s life, even though he is 40. Norman blames his mother for not selling the motel before the state built a new highway, leaving the motel starving for business. On a stormy night, Norman argues with Norma, who berates him for being spineless and taking no initiative in life. Feeling deflated, Norman puts his mother to bed and turns on the motel’s sign to attract passing travelers.

Lost after taking a wrong turn off the highway, Mary Crane stumbles upon the Bates motel. Mary is on the run after stealing $40,000 from her boss, Mr. Lowry. Mary spent her young adulthood caring for her ailing mother, while her sister, Lila, went to college. After their mother’s death, the sisters moved in together, and Mary went on a cruise. On the ship, Mary met Sam Loomis , and the two fell in love and became engaged. However, Sam will not marry Mary until he pays off the debts he inherited from his father, which should take two more years. In the meantime, they live far apart. Mary plans to use the stolen money to pay off Sam’s debts so they can start their life together. As Mary drives, her resolve begins to waver and she decides to take a room at the Bates Motel to think things over.

Norman is awkward, yet friendly. He does not seem threatening, so Mary accepts his invitation to dinner at his house, which is behind the motel. Mary is astonished by the house’s interior, which looks frozen in time from the previous century. Norman describes his difficult relationship with his mother, and when Mary suggests he take control of his life and get his mother psychiatric help, Norman loses his temper. He insists his mother is sane, blaming himself for ruining her mother’s life and feeling indebted to her. Norman apologizes for his outburst, and Mary excuses herself back to her room, which is next to the office. While Norman watches her through a peephole in the office, Mary resolves to return the stolen money. With this weight off her conscience, she takes a shower. An old woman enters the bathroom, but Mary doesn’t see her until it is too late. The intruder kills and decapitates Mary with a knife.

Norman’s conversation with Mary leaves him shaken. In the hotel office, he gets drunk, recalling how his mother threatened to kill Mary when he put her to bed that night. Norman passes out from the whiskey. When he wakes up, he discovers Mary’s body. He contemplates turning Norma in to the police but decides against it. Norman puts Mary’s body in her car and submerges it in a nearby swamp. He cleans the crime scene as thoroughly as he can. He finds one of Mary’s earrings but not its mate and assumes the other is still in Mary’s ear.

Sam Loomis sits in the office at his hardware store in Fairvale, calculating sales and thinking about Mary. A visitor knocks at the door, and Sam kisses her, mistaking her for Mary. He realizes his error: The visitor is Lila Crane , Mary’s sister. Lila explains that she has not heard from Mary since she left home without warning a week ago. The conversation is interrupted by the arrival of Milton Arbogast, a private investigator that Mr. Lowry’s firm hired to investigate the missing $40,000. Arbogast grills Sam and Lila until he is convinced they are not accomplices to the theft. Lila wants to report Mary missing, but Arbogast asks for 24 hours to follow up on final leads. Lila and Sam spend an anxious day waiting for Arbogast to call, wondering how well they really know Mary. Arbogast calls, saying he followed Mary’s trail to the Bates Motel. He plans to question the old woman he saw in the house’s window. They do not hear from him again.

Norman shaves, thinking of his relationship with his mother. Sometimes he feels like two people, reduced to a child when confronted by Norma. Norman has had to act as an adult to keep them both safe. He spends an uneventful afternoon in the motel office until Arbogast arrives. The detective questions Norman, tricking him into admitting he had dinner with Mary. Arbogast declares that he saw Mrs. Bates in the window and pressures Norman to allow him to question her about Mary. Reluctantly, Norman goes to the house to warn his mother. Suspiciously calm, Norma prepares to meet Arbogast. After she lets him inside, she kills him with Norman’s razor. Norman cleans up his mother’s mess, waiting until dark to roll Arbogast in a rug and dispose of him the same way he did Mary, rolling his Buick into the swamp. Norman locks Norma in the fruit cellar for her own protection and concocts a story to cover for Arbogast’s absence.

The next morning, Sam and Lila go to Sheriff Chambers, who listens to their story and guesses that Arbogast had found another clue about Mary and left town. He calls Norman, who tells him that Mary indicated she was heading to Chicago and that Arbogast left upon learning this. Further, Arbogast must have been lying about seeing Norman’s mother, who has been dead for 20 years, since she and her new husband, Joe Considine, died by suicide together. Norman was so traumatized that he spent several months hospitalized in a mental health facility. Lila discovers that Arbogast checked out of his hotel and intended to return for his bags but never did. She and Sam return to the sheriff to request a formal inquest. Chambers goes to the Bates Motel, and Norman allows him to inspect the property, but the sheriff finds nothing amiss. Unsatisfied, Lila wants to go to the motel herself. She suspects that the woman Arbogast saw in the window might have been Mary, held hostage in Norman’s house.

Sam and Lila check in to the motel under phony names as a married couple. Norman, drinking again, sees through this façade but makes no objections, even allowing them to rent the room where Mary died. Norman watches through the peephole as Lila finds Mary’s missing earring behind the shower stall, along with what Sam thinks is dried blood. Sam convinces Lila to go to the sheriff while he keeps Norman busy.

In the lobby, Norman offers Sam a drink while they talk. Sam tries to keep calm as Norman’s conversation becomes increasingly disturbing. He claims that Norma is still alive; he exhumed her body, which was in a state of suspended animation, and revived it with something akin to magic. Norman reveals that he saw Lila park the car up the road and walk to the house. Before Sam can react, Norman bashes his head with the whiskey bottle. Lila searches for Mary in Norman’s house, which is like an antique time capsule, eventually discovering the door to the fruit cellar. Inside, she finds Norma’s mummified body. Lila screams. Norman, dressed in his mother’s clothes, with makeup on his face, attacks her with a knife. Sam arrives just in time to wrest the knife from Norman’s hands.

Sam visits the psychiatric hospital sometime later for an interview with Norman’s psychiatrist and relays the information he gleaned to Lila, admitting he does not fully understand it. Norman has dissociative identity disorder, Sam reports, which splits his psyche between his child and adult selves and his mother. He adopted his mother’s persona after he murdered her and Joe Considine. “Norma” surfaced whenever Norman felt threatened. This seems to give Lila closure; she believes that Norman has suffered more than any of them. Later, in Norman’s cell, Norma’s personality assimilates into Norman’s other personalities. Norma sits perfectly still to show she is harmless; she blames Norman for the murders. She lets a fly crawl on her. Norma would not even hurt a fly.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Featured Collections

View Collection

Good & Evil

Jewish American Literature

Related Topics

- Entertainment

- Popular Culture

- American Culture

- Indian Culture

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton

- Organizational Culture

The film Psycho Essay (1292 words)

Academic anxiety?

Get original paper in 3 hours and nail the task

124 experts online

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, is a film of many genres it may be categorised as a thriller, a romance or a horror. Psycho focuses on the themes of secrets, lies, deceit, theft and above all duality. The film shows us the two sides of the characters, perhaps the most obvious to us as an audience is the character of Norman Bates. However, through the use of metaphors: mirrors and shadows, we also see the theme of duality in Marion Crane

The title credits of the film are very long, and because they are it leaves us wanting to watch the film as we are anxious. While watching the title credits we can anticipate many things wondering what the film is going to be about. For example the high pitch music warns us something terrible is going to happen, and the typography moving from side to side leaves us with a feeling of entrapment. The fact that the title credits are in black and white makes the audience believe that the plot is going to be simple because black and white are two basic and simple colours, however the plot is cunningly twisted and is not very simple.

The opening scene shows us Marion and her secret lover Sam in a hotel room, immediately the audience is exposed to a secret. In this scene Marion is wearing white underwear, white skirt and white blouse. The colour of white symbolizes purity and all that it good in a person. It can also portray that a person, in this case Marion is na�ve. This is because the person could be inexperienced in evil, wearing white also shows innocence.

However, a few scenes later, after Marion has stolen the money, we see her in black underwear. This is a complete contrast from her image in the opening scene, as her underwear colour has changed. When we think of the colour black, immediately symbols of evil and darkness enter us. So when Marion is wearing black the audience realise this change and understand she has done something wrong. It is at this point in the film that we see the first sign of duality. Marion has transformed from an innocent and na�ve woman to someone who has committed an evil deed, by stealing from her work. Hitchcock has portrayed this first theme of duality by using colour symbolism in costume, from white to black.

In the office scene Marion is wearing a white dress symbolising her innocence and loyalty towards her employer. However, this scene provides Marion an opportunity to steal the money. It is in this scene that we are introduced to the characters Cassidy and Mr Lowery. The second time we see Marion with these two characters she is on her way to the Bates Motel, but she is no longer a loyal employer but disloyal and a thief because she has stolen the $40,000. Marion is now wearing all black, again Hitchcock has used colour symbolism to portray duality. Duality is shown here because Marion was loyal but is now disloyal. Also in this scene when Marion is driving we can see through the back window of the car, as an audience we can tell that Marion is leaving her world behind her although at this point she is still a part of that world and has not yet left it.

The theme of duality is portrayed by Hitchcock by the use of shadows. This is shown in the bedroom scene, it is here where Marion decides to leave her home and begin her journey. In the bedroom scene we see Marion’s shadow enter before we see the character herself. This portrays the theme of duality because the shadow is almost representing a character within a character, as it is in the shape of a human but not in the form of a human. Like duality it is two sides to a person presented as one. In this scene there is a close up of the money, which is a white envelope, this contrasts with Marion’s dress which is black. Again Hitchcock has used colour symbolism as well as the use of shadows to portray duality. Throughout the parlour scene Norman is sitting on a small stool, making him seem bigger than his actual size. By sitting on a small stool we see a larger shadow of Norman.

Hitchcock also portrays the theme of duality by use of weather. When Marion is leaving her home the weather is bright and sunny, but before she arrives at the Bates Motel the weather becomes dull, dark and rainy. This shows duality because when she leaves Phoenix she probably has an intention of returning but when she arrives at the Bates Motel she realises that she can not return. This is because she has bought a car and knows that she will never be able to repay the money. Also while she is driving, she hears many

Voice-overs of her boss, Cassidy and her work colleague all worried about her. Marion can not return because she has done a bad deed and feels guilty that people are worried about her. The reason that duality is shown here is that Marion has now made the transaction between the two worlds, the good moral world she left behind and she has joined a world of deceit, secrecy and theft. The first time that the audience see Marion admitting to her duality is when she arrives at the Bates Motel and is signing in. This is shown by her using a false name, indicating that she is ashamed of her true self and wants to be someone else. By giving Marion two names, Hitchcock has allowed her to have two sides therefore making Marion see that what she has done is wrong. Not only does Marion give false name, but address as well. She is creating an entirely new character for herself. In this scene Hitchcock uses identity to portray the theme of duality.

When Marion enters the Bates Motel we are introduced to a new character, whose duality is a lot more obvious towards the end, however we do not find out until the penultimate scene of the film. This new character is Norman Bates. On the outside Norman seems like an ordinary, shy and well mannered man but on the inside he is eaten up by his mother’s death, evil and cunning. Not only is Norman a host, as owner of the Bates Motel, but a killer. He is a son but also a mother, by re-enacting his mother’s thoughts and words. Norman is also a man, by his natural state, and a woman, when he pretends to be his mother. Hitchcock uses a variety of ways to portray Norman Bates’ duality. On such way is in the parlour scene.

Norman is surrounded by sharp and square edges and dim lighting, which is the opposite to Marion, who is surrounded by soft lighting and round picture frames. The shape of a square is cornered and has a specific stop and start point, showing the cut off from one edge to the next. This is a mirror of Norman’s life, because he can cut from person to person, from a host to a killer, from himself to his mother. However Marion is surrounded by circular objects, which are curved and do not have a specific stop or start point. Hitchcock uses the circle to portray Marion because her character has developed signs of duality, such as giving a false name, to cover her tracks. She is confused about where her original moral self starts and finishes and where her new deceitful side begins and ends. In the parlour scene Hitchcock has used shapes to portray the theme of duality.

This essay was written by a fellow student. You may use it as a guide or sample for writing your own paper, but remember to cite it correctly . Don’t submit it as your own as it will be considered plagiarism.

Need custom essay sample written special for your assignment?

Choose skilled expert on your subject and get original paper with free plagiarism report

The film Psycho Essay (1292 words). (2018, Jan 25). Retrieved from https://artscolumbia.org/the-film-psycho-42055/

More related essays

A Thematic Analysis Of Alfred Hitchcocks Psycho Essay

Survivor’s Guilt in Speaking of Courage by Tim O’Brien

Pycho by alfred hitcock Essay (1978 words)

Harvey Norman Intangible Assets Essay

Psycho, The Movie Essay (2303 words)

The film progresses Essay (1449 words)

Deconstructing Scenes From Psycho Film Essay

Marion Barry Essay (2387 words)

Horror and suspense Essay (1245 words)

Hi, my name is Amy 👋

In case you can't find a relevant example, our professional writers are ready to help you write a unique paper. Just talk to our smart assistant Amy and she'll connect you with the best match.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

He filmed in black and white. Long passages contained no dialogue. His budget, $800,000, was cheap even by 1960 standards; the Bates Motel and mansion were built on the back lot at Universal. In its visceral feel, "Psycho" has more in common with noir quickies like "Detour" than with elegant Hitchcock thrillers like "Rear Window" or " Vertigo ."

January 22, 2020. "Psycho," the 1960 horror film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, was considered to be both a classic and first modern horror film opening the viewers of cinema to the "slasher" genre. The "slasher" or "psycho" is Norman Bates, and he takes on a complex role in the film, seen in the duality between him and Marion ...

Published: Jan 15, 2019. The film "Psycho" was produced in the 1960's by Alfred Hitchcock. It was called the "mother of the modern horror movie". Hitchcock wanted to manipulate his audience into fear and loathing, this was achieved by choosing to make the film in black and white rather than using colour to make the audience more ...

Collects a number of essays, including Brown 1994 (cited under Psycho's Music), Williams 2000 (cited under Essays in Books), and Toles 1984 (cited under General Analysis), as well as reviews and an original essay by Kolker on the film's visual design. Leigh, Janet, and Christopher Nickens. Psycho: Behind the Scenes of the Classic Thriller ...

By Lily Rothman. June 16, 2015 10:00 AM EDT. F ifty-five years after its June 16, 1960, premiere, Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho is firmly entrenched in the cinematic canon. It altered the suspense ...

Psycho was Hitchcock's first horror film and from then on he's been known as the master of suspense. He was the creator of the MacGuffin, something that drives the story, he used sharp violins to create suspense, while the audience let their own minds create the rest. In this essay I plan to deconstruct two scenes from the film, looking at ...

Rendered Previous Horror Films Obsolete, wrote Village Voice critic Andrew Sarris.The magazine republished his review from 1960: "Hitchcock is the most-daring avant-garde film-maker in America today.

Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" Annotation Essay (Movie Review) Psycho is considered the earliest slasher movie as well as one of the best films ever created. Wood calls it "perhaps the most terrifying film ever made" (142), describing it as a movie that takes viewers into the darkness of themselves. Based on a 1959 novel by Robert Bloch ...

The Greatness of "Psycho". November 18, 2012. The cinematic man of the year, at least in prominence, is Alfred Hitchcock. Not only was his "Vertigo" named the best film of all time in the ...

Fundamentally, the balance he manages to pioneer results in superb, enticing thriller movies such as "Psycho" (1960). Psycho is a prime example of Hitchcock's unparalleled knowledge and know-how of psychological thrillers. In the following essay, I will attempt to evaluate and analyse the visual techniques and sounds effects he uses to ...

The imminent, brutal turn of the plot in Cabin One's bathroom is the film's most celebrated fillip, but this quiet, subtly ominous dialogue between Leigh and Perkins enriches the film's texture and raises its emotional stakes. Once Marion's plans to return to Phoenix and make amends are ironically snuffed out, Psycho becomes Norman's ...

Plot Summary. Although it might now be more familiar as a 1960 film by Alfred Hitchcock, featuring Janet Leigh's fateful shower, Psycho began as a 1959 novel by Robert Bloch. The thriller, to which Bloch also wrote two sequels, tells the tale of Norman Bates and his troubled and troubling relationship with his mother at the rundown motel he ...

The main concept of this essay is to point out how psychoanalytic theory could be used as a method of understanding and analyzing cultural products. The most valid approach for this is to observe how the cinema integrates psychoanalytical theories into specific film concepts. For this reason a Hitchcock film is used as an example, for it a ...

Psycho is a 1960 American horror film produced and directed by Alfred Hitchcock.The screenplay, written by Joseph Stefano, was based on the 1959 novel of the same name by Robert Bloch.The film stars Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles, John Gavin and Martin Balsam.The plot centers on an encounter between on-the-run embezzler Marion Crane (Leigh) and shy motel proprietor Norman Bates ...

Profit and hubris are the only logical explanations for Gus Van Sant's shot-for-shot retread of Psycho, a rigorous exercise in homage that suffocates under the weight of its source of inspiration.Van Sant attempts to add his signature to "The Master's" canvas, injecting subliminal stock footage and contemporizing sexual mores, but his supplements are nothing more than extraneous hokum ...

Film Review : ' Psycho '. When looking at the first film chosen Psycho (1960) Hitchcock used detailed visual and aural compositions to express his characters feelings of paranoia and claustrophobia, along with his experienced editing skills to create suspense. With a fine-tuned sense of irony, Hitchcock examined the abnormal perversions and ...

In 1960 horror film changed for the better because of a movie directed by Alfred Hitchcock called "Psycho". Critics and moviegoers couldn't except change's, with his style of filming, and using relatable concepts it overcame it's boundaries and became the most epic advancements in horror films.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/ChrisStuckmannChris Stuckmann reviews Psycho, starring Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles, John Gavin, Martin Balsam. ...

Alfred Hitchcock thriller, Psycho [Alfred Hitchcock, 1960, USA] practices exquisite cinematography techniques to construct suspense and tremor to the spectators from his use of framing, lighting, camera movement, editing as well as sound. Film critic Roger Ebert states that a prevalent element among Hitchcock's films, is the guilt of the ...

Title of film: Psycho Review #1 Critic: Roger Elbert Title of Critique: Great Movie : Psycho Provide a basic outline of the critic's article. Critic reason circularly how the membrane is set up and where they tape-recorded it Informs the readers on how the bear wanted it to seem Discusses the elements the grow used to force this film fortunate

Period 1. Psycho Movie Review The film Psycho by Alfred Hitchcock is a horror film made in 1960. The film Psycho caused a huge amount of commotion in 1960 when it was released, it was a movie unlike any other that had ever been made, people were outraged and mindblown by this movie for many reasons. In the movie Psycho a young female takes a ...

Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho, is a film of many genres it may be categorised as a thriller, a romance or a horror. Psycho focuses on the themes of secrets, lies, deceit, theft and above all duality. The film shows us the two sides of the characters, perhaps the most obvious to us as an audience is the character of Norman Bates.