- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Gender Confirmation Surgery (GCS)

What is Gender Confirmation Surgery?

- Transfeminine Tr

Transmasculine Transition

- Traveling Abroad

Choosing a Surgeon

Gender confirmation surgery (GCS), known clinically as genitoplasty, are procedures that surgically confirm a person's gender by altering the genitalia and other physical features to align with their desired physical characteristics. Gender confirmation surgeries are also called gender affirmation procedures. These are both respectful terms.

Gender dysphoria , an experience of misalignment between gender and sex, is becoming more widely diagnosed. People diagnosed with gender dysphoria are often referred to as "transgender," though one does not necessarily need to experience gender dysphoria to be a member of the transgender community. It is important to note there is controversy around the gender dysphoria diagnosis. Many disapprove of it, noting that the diagnosis suggests that being transgender is an illness.

Ellen Lindner / Verywell

Transfeminine Transition

Transfeminine is a term inclusive of trans women and non-binary trans people assigned male at birth.

Gender confirmation procedures that a transfeminine person may undergo include:

- Penectomy is the surgical removal of external male genitalia.

- Orchiectomy is the surgical removal of the testes.

- Vaginoplasty is the surgical creation of a vagina.

- Feminizing genitoplasty creates internal female genitalia.

- Breast implants create breasts.

- Gluteoplasty increases buttock volume.

- Chondrolaryngoplasty is a procedure on the throat that can minimize the appearance of Adam's apple .

Feminizing hormones are commonly used for at least 12 months prior to breast augmentation to maximize breast growth and achieve a better surgical outcome. They are also often used for approximately 12 months prior to feminizing genital surgeries.

Facial feminization surgery (FFS) is often done to soften the lines of the face. FFS can include softening the brow line, rhinoplasty (nose job), smoothing the jaw and forehead, and altering the cheekbones. Each person is unique and the procedures that are done are based on the individual's need and budget,

Transmasculine is a term inclusive of trans men and non-binary trans people assigned female at birth.

Gender confirmation procedures that a transmasculine person may undergo include:

- Masculinizing genitoplasty is the surgical creation of external genitalia. This procedure uses the tissue of the labia to create a penis.

- Phalloplasty is the surgical construction of a penis using a skin graft from the forearm, thigh, or upper back.

- Metoidioplasty is the creation of a penis from the hormonally enlarged clitoris.

- Scrotoplasty is the creation of a scrotum.

Procedures that change the genitalia are performed with other procedures, which may be extensive.

The change to a masculine appearance may also include hormone therapy with testosterone, a mastectomy (surgical removal of the breasts), hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus), and perhaps additional cosmetic procedures intended to masculinize the appearance.

Paying For Gender Confirmation Surgery

Medicare and some health insurance providers in the United States may cover a portion of the cost of gender confirmation surgery.

It is unlawful to discriminate or withhold healthcare based on sex or gender. However, many plans do have exclusions.

For most transgender individuals, the burden of financing the procedure(s) is the main difficulty in obtaining treatment. The cost of transitioning can often exceed $100,000 in the United States, depending upon the procedures needed.

A typical genitoplasty alone averages about $18,000. Rhinoplasty, or a nose job, averaged $5,409 in 2019.

Traveling Abroad for GCS

Some patients seek gender confirmation surgery overseas, as the procedures can be less expensive in some other countries. It is important to remember that traveling to a foreign country for surgery, also known as surgery tourism, can be very risky.

Regardless of where the surgery will be performed, it is essential that your surgeon is skilled in the procedure being performed and that your surgery will be performed in a reputable facility that offers high-quality care.

When choosing a surgeon , it is important to do your research, whether the surgery is performed in the U.S. or elsewhere. Talk to people who have already had the procedure and ask about their experience and their surgeon.

Before and after photos don't tell the whole story, and can easily be altered, so consider asking for a patient reference with whom you can speak.

It is important to remember that surgeons have specialties and to stick with your surgeon's specialty. For example, you may choose to have one surgeon perform a genitoplasty, but another to perform facial surgeries. This may result in more expenses, but it can result in a better outcome.

A Word From Verywell

Gender confirmation surgery is very complex, and the procedures that one person needs to achieve their desired result can be very different from what another person wants.

Each individual's goals for their appearance will be different. For example, one individual may feel strongly that breast implants are essential to having a desirable and feminine appearance, while a different person may not feel that breast size is a concern. A personalized approach is essential to satisfaction because personal appearance is so highly individualized.

Davy Z, Toze M. What is gender dysphoria? A critical systematic narrative review . Transgend Health . 2018;3(1):159-169. doi:10.1089/trgh.2018.0014

Morrison SD, Vyas KS, Motakef S, et al. Facial Feminization: Systematic Review of the Literature . Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(6):1759-70. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002171

Hadj-moussa M, Agarwal S, Ohl DA, Kuzon WM. Masculinizing Genital Gender Confirmation Surgery . Sex Med Rev . 2019;7(1):141-155. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.06.004

Dowshen NL, Christensen J, Gruschow SM. Health Insurance Coverage of Recommended Gender-Affirming Health Care Services for Transgender Youth: Shopping Online for Coverage Information . Transgend Health . 2019;4(1):131-135. doi:10.1089/trgh.2018.0055

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Rhinoplasty nose surgery .

Rights Group: More U.S. Companies Covering Cost of Gender Reassignment Surgery. CNS News. http://cnsnews.com/news/article/rights-group-more-us-companies-covering-cost-gender-reassignment-surgery

The Sex Change Capital of the US. CBS News. http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-3445_162-4423154.html

By Jennifer Whitlock, RN, MSN, FN Jennifer Whitlock, RN, MSN, FNP-C, is a board-certified family nurse practitioner. She has experience in primary care and hospital medicine.

- Search the site GO Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Mental Health

- Social and Public Health

What Is Gender Affirmation Surgery?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KP-Headshot-IMG_1661-0d48c6ea46f14ab19a91e7b121b49f59.jpg)

A gender affirmation surgery allows individuals, such as those who identify as transgender or nonbinary, to change one or more of their sex characteristics. This type of procedure offers a person the opportunity to have features that align with their gender identity.

For example, this type of surgery may be a transgender surgery like a male-to-female or female-to-male surgery. Read on to learn more about what masculinizing, feminizing, and gender-nullification surgeries may involve, including potential risks and complications.

Why Is Gender Affirmation Surgery Performed?

A person may have gender affirmation surgery for different reasons. They may choose to have the surgery so their physical features and functional ability align more closely with their gender identity.

For example, one study found that 48,019 people underwent gender affirmation surgeries between 2016 and 2020. Most procedures were breast- and chest-related, while the remaining procedures concerned genital reconstruction or facial and cosmetic procedures.

In some cases, surgery may be medically necessary to treat dysphoria. Dysphoria refers to the distress that transgender people may experience when their gender identity doesn't match their sex assigned at birth. One study found that people with gender dysphoria who had gender affirmation surgeries experienced:

- Decreased antidepressant use

- Decreased anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation

- Decreased alcohol and drug abuse

However, these surgeries are only performed if appropriate for a person's case. The appropriateness comes about as a result of consultations with mental health professionals and healthcare providers.

Transgender vs Nonbinary

Transgender and nonbinary people can get gender affirmation surgeries. However, there are some key ways that these gender identities differ.

Transgender is a term that refers to people who have gender identities that aren't the same as their assigned sex at birth. Identifying as nonbinary means that a person doesn't identify only as a man or a woman. A nonbinary individual may consider themselves to be:

- Both a man and a woman

- Neither a man nor a woman

- An identity between or beyond a man or a woman

Hormone Therapy

Gender-affirming hormone therapy uses sex hormones and hormone blockers to help align the person's physical appearance with their gender identity. For example, some people may take masculinizing hormones.

"They start growing hair, their voice deepens, they get more muscle mass," Heidi Wittenberg, MD , medical director of the Gender Institute at Saint Francis Memorial Hospital in San Francisco and director of MoZaic Care Inc., which specializes in gender-related genital, urinary, and pelvic surgeries, told Health .

Types of hormone therapy include:

- Masculinizing hormone therapy uses testosterone. This helps to suppress the menstrual cycle, grow facial and body hair, increase muscle mass, and promote other male secondary sex characteristics.

- Feminizing hormone therapy includes estrogens and testosterone blockers. These medications promote breast growth, slow the growth of body and facial hair, increase body fat, shrink the testicles, and decrease erectile function.

- Non-binary hormone therapy is typically tailored to the individual and may include female or male sex hormones and/or hormone blockers.

It can include oral or topical medications, injections, a patch you wear on your skin, or a drug implant. The therapy is also typically recommended before gender affirmation surgery unless hormone therapy is medically contraindicated or not desired by the individual.

Masculinizing Surgeries

Masculinizing surgeries can include top surgery, bottom surgery, or both. Common trans male surgeries include:

- Chest masculinization (breast tissue removal and areola and nipple repositioning/reshaping)

- Hysterectomy (uterus removal)

- Metoidioplasty (lengthening the clitoris and possibly extending the urethra)

- Oophorectomy (ovary removal)

- Phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis)

- Scrotoplasty (surgery to create a scrotum)

Top Surgery

Chest masculinization surgery, or top surgery, often involves removing breast tissue and reshaping the areola and nipple. There are two main types of chest masculinization surgeries:

- Double-incision approach : Used to remove moderate to large amounts of breast tissue, this surgery involves two horizontal incisions below the breast to remove breast tissue and accentuate the contours of pectoral muscles. The nipples and areolas are removed and, in many cases, resized, reshaped, and replaced.

- Short scar top surgery : For people with smaller breasts and firm skin, the procedure involves a small incision along the lower half of the areola to remove breast tissue. The nipple and areola may be resized before closing the incision.

Metoidioplasty

Some trans men elect to do metoidioplasty, also called a meta, which involves lengthening the clitoris to create a small penis. Both a penis and a clitoris are made of the same type of tissue and experience similar sensations.

Before metoidioplasty, testosterone therapy may be used to enlarge the clitoris. The procedure can be completed in one surgery, which may also include:

- Constructing a glans (head) to look more like a penis

- Extending the urethra (the tube urine passes through), which allows the person to urinate while standing

- Creating a scrotum (scrotoplasty) from labia majora tissue

Phalloplasty

Other trans men opt for phalloplasty to give them a phallic structure (penis) with sensation. Phalloplasty typically requires several procedures but results in a larger penis than metoidioplasty.

The first and most challenging step is to harvest tissue from another part of the body, often the forearm or back, along with an artery and vein or two, to create the phallus, Nicholas Kim, MD, assistant professor in the division of plastic and reconstructive surgery in the department of surgery at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, told Health .

Those structures are reconnected under an operative microscope using very fine sutures—"thinner than our hair," said Dr. Kim. That surgery alone can take six to eight hours, he added.

In a separate operation, called urethral reconstruction, the surgeons connect the urinary system to the new structure so that urine can pass through it, said Dr. Kim. Urethral reconstruction, however, has a high rate of complications, which include fistulas or strictures.

According to Dr. Kim, some trans men prefer to skip that step, especially if standing to urinate is not a priority. People who want to have penetrative sex will also need prosthesis implant surgery.

Hysterectomy and Oophorectomy

Masculinizing surgery often includes the removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) and ovaries (oophorectomy). People may want a hysterectomy to address their dysphoria, said Dr. Wittenberg, and it may be necessary if their gender-affirming surgery involves removing the vagina.

Many also opt for an oophorectomy to remove the ovaries, almond-shaped organs on either side of the uterus that contain eggs and produce female sex hormones. In this case, oocytes (eggs) can be extracted and stored for a future surrogate pregnancy, if desired. However, this is a highly personal decision, and some trans men choose to keep their uterus to preserve fertility.

Feminizing Surgeries

Surgeries are often used to feminize facial features, enhance breast size and shape, reduce the size of an Adam’s apple , and reconstruct genitals. Feminizing surgeries can include:

- Breast augmentation

- Facial feminization surgery

- Penis removal (penectomy)

- Scrotum removal (scrotectomy)

- Testicle removal (orchiectomy)

- Tracheal shave (chondrolaryngoplasty) to reduce an Adam's apple

- Vaginoplasty

- Voice feminization

Breast Augmentation

Top surgery, also known as breast augmentation or breast mammoplasty, is often used to increase breast size for a more feminine appearance. The procedure can involve placing breast implants, tissue expanders, or fat from other parts of the body under the chest tissue.

Breast augmentation can significantly improve gender dysphoria. Studies show most people who undergo top surgery are happier, more satisfied with their chest, and would undergo the surgery again.

Most surgeons recommend 12 months of feminizing hormone therapy before breast augmentation. Since hormone therapy itself can lead to breast tissue development, transgender women may or may not decide to have surgical breast augmentation.

Facial Feminization and Adam's Apple Removal

Facial feminization surgery (FFS) is a series of plastic surgery procedures that reshape the forehead, hairline, eyebrows, nose, cheeks, and jawline. Nonsurgical treatments like cosmetic fillers, botox, fat grafting, and liposuction may also be used to create a more feminine appearance.

Some trans women opt for chondrolaryngoplasty, also known as a tracheal shave. The procedure reduces the size of the Adam's apple, an area of cartilage around the larynx (voice box) that tends to be larger in people assigned male at birth.

Vulvoplasty and Vaginoplasty

As for bottom surgery, there are various feminizing procedures from which to choose. Vulvoplasty (to create external genitalia without a vagina) or vaginoplasty (to create a vulva and vaginal canal) are two of the most common procedures.

Dr. Wittenberg noted that people might undergo six to 12 months of electrolysis or laser hair removal before surgery to remove pubic hair from the skin that will be used for the vaginal lining.

Surgeons have different techniques for creating a vaginal canal. A common one is a penile inversion, where the masculine structures are emptied and inverted into a created cavity, explained Dr. Kim. Vaginoplasty may be done in one or two stages, said Dr. Wittenberg, and the initial recovery is three months—but it will be a full year until people see results.

Surgical removal of the penis or penectomy is sometimes used in feminization treatment. This can be performed along with an orchiectomy and scrotectomy.

However, a total penectomy is not commonly used in feminizing surgeries . Instead, many people opt for penile-inversion surgery, a technique that hollows out the penis and repurposes the tissue to create a vagina during vaginoplasty.

Orchiectomy and Scrotectomy

An orchiectomy is a surgery to remove the testicles —male reproductive organs that produce sperm. Scrotectomy is surgery to remove the scrotum, that sac just below the penis that holds the testicles.

However, some people opt to retain the scrotum. Scrotum skin can be used in vulvoplasty or vaginoplasty, surgeries to construct a vulva or vagina.

Other Surgical Options

Some gender non-conforming people opt for other types of surgeries. This can include:

- Gender nullification procedures

- Penile preservation vaginoplasty

- Vaginal preservation phalloplasty

Gender Nullification

People who are agender or asexual may opt for gender nullification, sometimes called nullo. This involves the removal of all sex organs. The external genitalia is removed, leaving an opening for urine to pass and creating a smooth transition from the abdomen to the groin.

Depending on the person's sex assigned at birth, nullification surgeries can include:

- Breast tissue removal

- Nipple and areola augmentation or removal

Penile Preservation Vaginoplasty

Some gender non-conforming people assigned male at birth want a vagina but also want to preserve their penis, said Dr. Wittenberg. Often, that involves taking skin from the lining of the abdomen to create a vagina with full depth.

Vaginal Preservation Phalloplasty

Alternatively, a patient assigned female at birth can undergo phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis) and retain the vaginal opening. Known as vaginal preservation phalloplasty, it is often used as a way to resolve gender dysphoria while retaining fertility.

The recovery time for a gender affirmation surgery will depend on the type of surgery performed. For example, healing for facial surgeries may last for weeks, while transmasculine bottom surgery healing may take months.

Your recovery process may also include additional treatments or therapies. Mental health support and pelvic floor physiotherapy are a few options that may be needed or desired during recovery.

Risks and Complications

The risk and complications of gender affirmation surgeries will vary depending on which surgeries you have. Common risks across procedures could include:

- Anesthesia risks

- Hematoma, which is bad bruising

- Poor incision healing

Complications from these procedures may be:

- Acute kidney injury

- Blood transfusion

- Deep vein thrombosis, which is blood clot formation

- Pulmonary embolism, blood vessel blockage for vessels going to the lung

- Rectovaginal fistula, which is a connection between two body parts—in this case, the rectum and vagina

- Surgical site infection

- Urethral stricture or stenosis, which is when the urethra narrows

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Wound disruption

What To Consider

It's important to note that an individual does not need surgery to transition. If the person has surgery, it is usually only one part of the transition process.

There's also psychotherapy . People may find it helpful to work through the negative mental health effects of dysphoria. Typically, people seeking gender affirmation surgery must be evaluated by a qualified mental health professional to obtain a referral.

Some people may find that living in their preferred gender is all that's needed to ease their dysphoria. Doing so for one full year prior is a prerequisite for many surgeries.

All in all, the entire transition process—living as your identified gender, obtaining mental health referrals, getting insurance approvals, taking hormones, going through hair removal, and having various surgeries—can take years, healthcare providers explained.

A Quick Review

Whether you're in the process of transitioning or supporting someone who is, it's important to be informed about gender affirmation surgeries. Gender affirmation procedures often involve multiple surgeries, which can be masculinizing, feminizing, or gender-nullifying in nature.

It is a highly personalized process that looks different for each person and can often take several months or years. The procedures also vary regarding risks and complications, so consultations with healthcare providers and mental health professionals are essential before having these procedures.

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Gender affirmation surgeries .

Wright JD, Chen L, Suzuki Y, Matsuo K, Hershman DL. National estimates of gender-affirming surgery in the US . JAMA Netw Open . 2023;6(8):e2330348-e2330348. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30348

Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8 . Int J Transgend Health . 2022;23(S1):S1-S260. doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

Chou J, Kilmer LH, Campbell CA, DeGeorge BR, Stranix JY. Gender-affirming surgery improves mental health outcomes and decreases anti-depressant use in patients with gender dysphoria . Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open . 2023;11(6 Suppl):1. doi:10.1097/01.GOX.0000944280.62632.8c

Human Rights Campaign. Get the facts on gender-affirming care .

Human Rights Campaign. Transgender and non-binary people FAQ .

Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients . Transl Androl Urol . 2016;5(6):877–84. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04

Richards JE, Hawley RS. Chapter 8: Sex Determination: How Genes Determine a Developmental Choice . In: Richards JE, Hawley RS, eds. The Human Genome . 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2011: 273-298.

Randolph JF Jr. Gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender females . Clin Obstet Gynecol . 2018;61(4):705-721. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000396

Cocchetti C, Ristori J, Romani A, Maggi M, Fisher AD. Hormonal treatment strategies tailored to non-binary transgender individuals . J Clin Med . 2020;9(6):1609. doi:10.3390/jcm9061609

Van Boerum MS, Salibian AA, Bluebond-Langner R, Agarwal C. Chest and facial surgery for the transgender patient . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):219-227. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.18

Djordjevic ML, Stojanovic B, Bizic M. Metoidioplasty: techniques and outcomes . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):248–53. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.12

Bordas N, Stojanovic B, Bizic M, Szanto A, Djordjevic ML. Metoidioplasty: surgical options and outcomes in 813 cases . Front Endocrinol . 2021;12:760284. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.760284

Al-Tamimi M, Pigot GL, van der Sluis WB, et al. The surgical techniques and outcomes of secondary phalloplasty after metoidioplasty in transgender men: an international, multi-center case series . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2019;16(11):1849-1859. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.07.027

Waterschoot M, Hoebeke P, Verla W, et al. Urethral complications after metoidioplasty for genital gender affirming surgery . J Sex Med . 2021;18(7):1271–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.023

Nikolavsky D, Hughes M, Zhao LC. Urologic complications after phalloplasty or metoidioplasty . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):425–35. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.013

Nota NM, den Heijer M, Gooren LJ. Evaluation and treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender incongruent adults . In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext . MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

Carbonnel M, Karpel L, Cordier B, Pirtea P, Ayoubi JM. The uterus in transgender men . Fertil Steril . 2021;116(4):931–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.07.005

Miller TJ, Wilson SC, Massie JP, Morrison SD, Satterwhite T. Breast augmentation in male-to-female transgender patients: Technical considerations and outcomes . JPRAS Open . 2019;21:63-74. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2019.03.003

Claes KEY, D'Arpa S, Monstrey SJ. Chest surgery for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):369–80. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.010

De Boulle K, Furuyama N, Heydenrych I, et al. Considerations for the use of minimally invasive aesthetic procedures for facial remodeling in transgender individuals . Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol . 2021;14:513-525. doi:10.2147/CCID.S304032

Asokan A, Sudheendran MK. Gender affirming body contouring and physical transformation in transgender individuals . Indian J Plast Surg . 2022;55(2):179-187. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1749099

Sturm A, Chaiet SR. Chondrolaryngoplasty-thyroid cartilage reduction . Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am . 2019;27(2):267–72. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.005

Chen ML, Reyblat P, Poh MM, Chi AC. Overview of surgical techniques in gender-affirming genital surgery . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):191-208. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.19

Wangjiraniran B, Selvaggi G, Chokrungvaranont P, Jindarak S, Khobunsongserm S, Tiewtranon P. Male-to-female vaginoplasty: Preecha's surgical technique . J Plast Surg Hand Surg . 2015;49(3):153-9. doi:10.3109/2000656X.2014.967253

Okoye E, Saikali SW. Orchiectomy . In: StatPearls [Internet] . Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Salgado CJ, Yu K, Lalama MJ. Vaginal and reproductive organ preservation in trans men undergoing gender-affirming phalloplasty: technical considerations . J Surg Case Rep . 2021;2021(12):rjab553. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjab553

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after facial feminization surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after transmasculine bottom surgery?

de Brouwer IJ, Elaut E, Becker-Hebly I, et al. Aftercare needs following gender-affirming surgeries: findings from the ENIGI multicenter European follow-up study . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2021;18(11):1921-1932. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.08.005

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transfeminine bottom surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transmasculine top surgery?

Khusid E, Sturgis MR, Dorafshar AH, et al. Association between mental health conditions and postoperative complications after gender-affirming surgery . JAMA Surg . 2022;157(12):1159-1162. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.3917

Related Articles

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Feminizing surgery

Feminizing surgery, also called gender-affirming surgery or gender-confirmation surgery, involves procedures that help better align the body with a person's gender identity. Feminizing surgery includes several options, such as top surgery to increase the size of the breasts. That procedure also is called breast augmentation. Bottom surgery can involve removal of the testicles, or removal of the testicles and penis and the creation of a vagina, labia and clitoris. Facial procedures or body-contouring procedures can be used as well.

Not everybody chooses to have feminizing surgery. These surgeries can be expensive, carry risks and complications, and involve follow-up medical care and procedures. Certain surgeries change fertility and sexual sensations. They also may change how you feel about your body.

Your health care team can talk with you about your options and help you weigh the risks and benefits.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Available Sexual Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

Many people seek feminizing surgery as a step in the process of treating discomfort or distress because their gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. The medical term for this is gender dysphoria.

For some people, having feminizing surgery feels like a natural step. It's important to their sense of self. Others choose not to have surgery. All people relate to their bodies differently and should make individual choices that best suit their needs.

Feminizing surgery may include:

- Removal of the testicles alone. This is called orchiectomy.

- Removal of the penis, called penectomy.

- Removal of the testicles.

- Creation of a vagina, called vaginoplasty.

- Creation of a clitoris, called clitoroplasty.

- Creation of labia, called labioplasty.

- Breast surgery. Surgery to increase breast size is called top surgery or breast augmentation. It can be done through implants, the placement of tissue expanders under breast tissue, or the transplantation of fat from other parts of the body into the breast.

- Plastic surgery on the face. This is called facial feminization surgery. It involves plastic surgery techniques in which the jaw, chin, cheeks, forehead, nose, and areas surrounding the eyes, ears or lips are changed to create a more feminine appearance.

- Tummy tuck, called abdominoplasty.

- Buttock lift, called gluteal augmentation.

- Liposuction, a surgical procedure that uses a suction technique to remove fat from specific areas of the body.

- Voice feminizing therapy and surgery. These are techniques used to raise voice pitch.

- Tracheal shave. This surgery reduces the thyroid cartilage, also called the Adam's apple.

- Scalp hair transplant. This procedure removes hair follicles from the back and side of the head and transplants them to balding areas.

- Hair removal. A laser can be used to remove unwanted hair. Another option is electrolysis, a procedure that involves inserting a tiny needle into each hair follicle. The needle emits a pulse of electric current that damages and eventually destroys the follicle.

Your health care provider might advise against these surgeries if you have:

- Significant medical conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Behavioral health conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Any condition that limits your ability to give your informed consent.

Like any other type of major surgery, many types of feminizing surgery pose a risk of bleeding, infection and a reaction to anesthesia. Other complications might include:

- Delayed wound healing

- Fluid buildup beneath the skin, called seroma

- Bruising, also called hematoma

- Changes in skin sensation such as pain that doesn't go away, tingling, reduced sensation or numbness

- Damaged or dead body tissue — a condition known as tissue necrosis — such as in the vagina or labia

- A blood clot in a deep vein, called deep vein thrombosis, or a blood clot in the lung, called pulmonary embolism

- Development of an irregular connection between two body parts, called a fistula, such as between the bladder or bowel into the vagina

- Urinary problems, such as incontinence

- Pelvic floor problems

- Permanent scarring

- Loss of sexual pleasure or function

- Worsening of a behavioral health problem

Certain types of feminizing surgery may limit or end fertility. If you want to have biological children and you're having surgery that involves your reproductive organs, talk to your health care provider before surgery. You may be able to freeze sperm with a technique called sperm cryopreservation.

How you prepare

Before surgery, you meet with your surgeon. Work with a surgeon who is board certified and experienced in the procedures you want. Your surgeon talks with you about your options and the potential results. The surgeon also may provide information on details such as the type of anesthesia that will be used during surgery and the kind of follow-up care that you may need.

Follow your health care team's directions on preparing for your procedures. This may include guidelines on eating and drinking. You may need to make changes in the medicine you take and stop using nicotine, including vaping, smoking and chewing tobacco.

Because feminizing surgery might cause physical changes that cannot be reversed, you must give informed consent after thoroughly discussing:

- Risks and benefits

- Alternatives to surgery

- Expectations and goals

- Social and legal implications

- Potential complications

- Impact on sexual function and fertility

Evaluation for surgery

Before surgery, a health care provider evaluates your health to address any medical conditions that might prevent you from having surgery or that could affect the procedure. This evaluation may be done by a provider with expertise in transgender medicine. The evaluation might include:

- A review of your personal and family medical history

- A physical exam

- A review of your vaccinations

- Screening tests for some conditions and diseases

- Identification and management, if needed, of tobacco use, drug use, alcohol use disorder, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections

- Discussion about birth control, fertility and sexual function

You also may have a behavioral health evaluation by a health care provider with expertise in transgender health. That evaluation might assess:

- Gender identity

- Gender dysphoria

- Mental health concerns

- Sexual health concerns

- The impact of gender identity at work, at school, at home and in social settings

- The role of social transitioning and hormone therapy before surgery

- Risky behaviors, such as substance use or use of unapproved hormone therapy or supplements

- Support from family, friends and caregivers

- Your goals and expectations of treatment

- Care planning and follow-up after surgery

Other considerations

Health insurance coverage for feminizing surgery varies widely. Before you have surgery, check with your insurance provider to see what will be covered.

Before surgery, you might consider talking to others who have had feminizing surgery. If you don't know someone, ask your health care provider about support groups in your area or online resources you can trust. People who have gone through the process may be able to help you set your expectations and offer a point of comparison for your own goals of the surgery.

What you can expect

Facial feminization surgery.

Facial feminization surgery may involve a range of procedures to change facial features, including:

- Moving the hairline to create a smaller forehead

- Enlarging the lips and cheekbones with implants

- Reshaping the jaw and chin

- Undergoing skin-tightening surgery after bone reduction

These surgeries are typically done on an outpatient basis, requiring no hospital stay. Recovery time for most of them is several weeks. Recovering from jaw procedures takes longer.

Tracheal shave

A tracheal shave minimizes the thyroid cartilage, also called the Adam's apple. During this procedure, a small cut is made under the chin, in the shadow of the neck or in a skin fold to conceal the scar. The surgeon then reduces and reshapes the cartilage. This is typically an outpatient procedure, requiring no hospital stay.

Top surgery

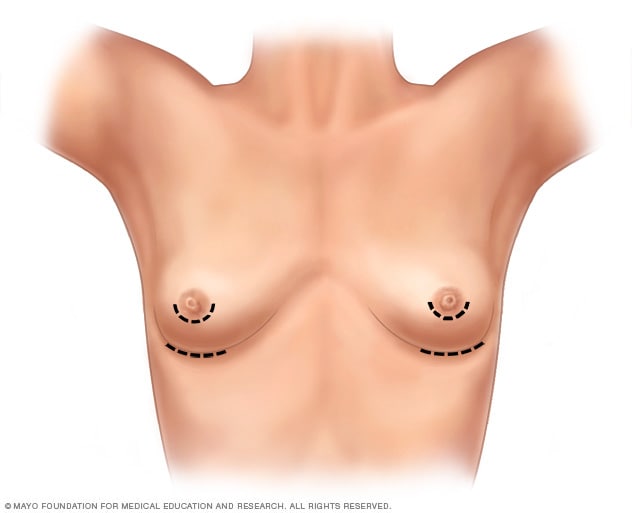

- Breast augmentation incisions

As part of top surgery, the surgeon makes cuts around the areola, near the armpit or in the crease under the breast.

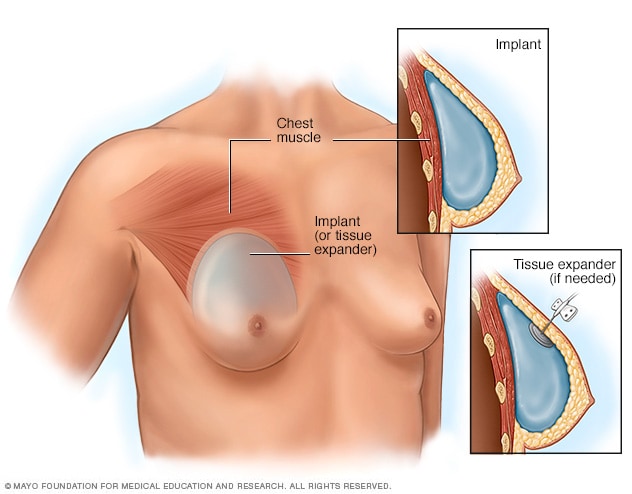

- Placement of breast implants or tissue expanders

During top surgery, the surgeon places the implants under the breast tissue. If feminizing hormones haven't made the breasts large enough, an initial surgery might be needed to have devices called tissue expanders placed in front of the chest muscles.

Hormone therapy with estrogen stimulates breast growth, but many people aren't satisfied with that growth alone. Top surgery is a surgical procedure to increase breast size that may involve implants, fat grafting or both.

During this surgery, a surgeon makes cuts around the areola, near the armpit or in the crease under the breast. Next, silicone or saline implants are placed under the breast tissue. Another option is to transplant fat, muscles or tissue from other parts of the body into the breasts.

If feminizing hormones haven't made the breasts large enough for top surgery, an initial surgery may be needed to place devices called tissue expanders in front of the chest muscles. After that surgery, visits to a health care provider are needed every few weeks to have a small amount of saline injected into the tissue expanders. This slowly stretches the chest skin and other tissues to make room for the implants. When the skin has been stretched enough, another surgery is done to remove the expanders and place the implants.

Genital surgery

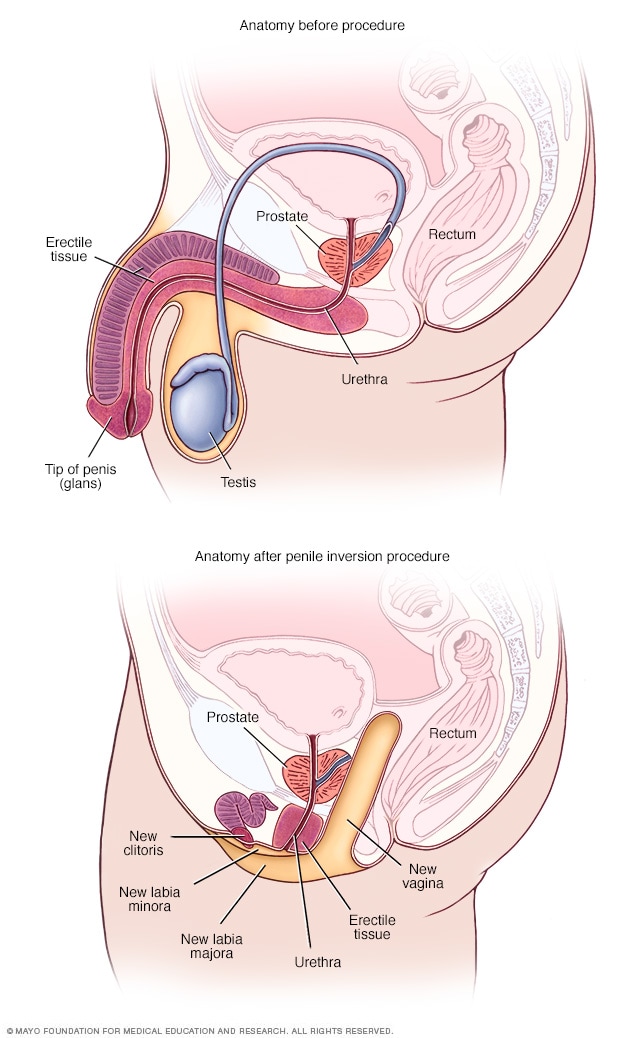

- Anatomy before and after penile inversion

During penile inversion, the surgeon makes a cut in the area between the rectum and the urethra and prostate. This forms a tunnel that becomes the new vagina. The surgeon lines the inside of the tunnel with skin from the scrotum, the penis or both. If there's not enough penile or scrotal skin, the surgeon might take skin from another area of the body and use it for the new vagina as well.

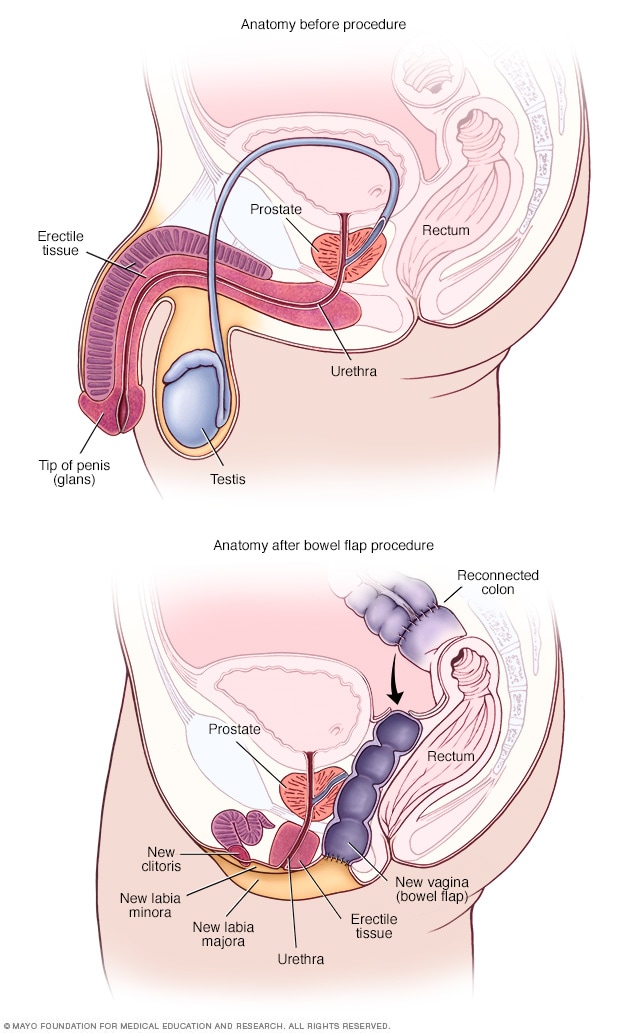

- Anatomy before and after bowel flap procedure

A bowel flap procedure might be done if there's not enough tissue or skin in the penis or scrotum. The surgeon moves a segment of the colon or small bowel to form a new vagina. That segment is called a bowel flap or conduit. The surgeon reconnects the remaining parts of the colon.

Orchiectomy

Orchiectomy is a surgery to remove the testicles. Because testicles produce sperm and the hormone testosterone, an orchiectomy might eliminate the need to use testosterone blockers. It also may lower the amount of estrogen needed to achieve and maintain the appearance you want.

This type of surgery is typically done on an outpatient basis. A local anesthetic may be used, so only the testicular area is numbed. Or the surgery may be done using general anesthesia. This means you are in a sleep-like state during the procedure.

To remove the testicles, a surgeon makes a cut in the scrotum and removes the testicles through the opening. Orchiectomy is typically done as part of the surgery for vaginoplasty. But some people prefer to have it done alone without other genital surgery.

Vaginoplasty

Vaginoplasty is the surgical creation of a vagina. During vaginoplasty, skin from the shaft of the penis and the scrotum is used to create a vaginal canal. This surgical approach is called penile inversion. In some techniques, the skin also is used to create the labia. That procedure is called labiaplasty. To surgically create a clitoris, the tip of the penis and the nerves that supply it are used. This procedure is called a clitoroplasty. In some cases, skin can be taken from another area of the body or tissue from the colon may be used to create the vagina. This approach is called a bowel flap procedure. During vaginoplasty, the testicles are removed if that has not been done previously.

Some surgeons use a technique that requires laser hair removal in the area of the penis and scrotum to provide hair-free tissue for the procedure. That process can take several months. Other techniques don't require hair removal prior to surgery because the hair follicles are destroyed during the procedure.

After vaginoplasty, a tube called a catheter is placed in the urethra to collect urine for several days. You need to be closely watched for about a week after surgery. Recovery can take up to two months. Your health care provider gives you instructions about when you may begin sexual activity with your new vagina.

After surgery, you're given a set of vaginal dilators of increasing sizes. You insert the dilators in your vagina to maintain, lengthen and stretch it. Follow your health care provider's directions on how often to use the dilators. To keep the vagina open, dilation needs to continue long term.

Because the prostate gland isn't removed during surgery, you need to follow age-appropriate recommendations for prostate cancer screening. Following surgery, it is possible to develop urinary symptoms from enlargement of the prostate.

Dilation after gender-affirming surgery

This material is for your education and information only. This content does not replace medical advice, diagnosis and treatment. If you have questions about a medical condition, always talk with your health care provider.

Narrator: Vaginal dilation is important to your recovery and ongoing care. You have to dilate to maintain the size and shape of your vaginal canal and to keep it open.

Jessi: I think for many trans women, including myself, but especially myself, I looked forward to one day having surgery for a long time. So that meant looking up on the internet what the routines would be, what the surgery entailed. So I knew going into it that dilation was going to be a very big part of my routine post-op, but just going forward, permanently.

Narrator: Vaginal dilation is part of your self-care. You will need to do vaginal dilation for the rest of your life.

Alissa (nurse): If you do not do dilation, your vagina may shrink or close. If that happens, these changes might not be able to be reversed.

Narrator: For the first year after surgery, you will dilate many times a day. After the first year, you may only need to dilate once a week. Most people dilate for the rest of their life.

Jessi: The dilation became easier mostly because I healed the scars, the stitches held up a little bit better, and I knew how to do it better. Each transgender woman's vagina is going to be a little bit different based on anatomy, and I grew to learn mine. I understand, you know, what position I needed to put the dilator in, how much force I needed to use, and once I learned how far I needed to put it in and I didn't force it and I didn't worry so much on oh, did I put it in too far, am I not putting it in far enough, and I have all these worries and then I stress out and then my body tenses up. Once I stopped having those thoughts, I relaxed more and it was a lot easier.

Narrator: You will have dilators of different sizes. Your health care provider will determine which sizes are best for you. Dilation will most likely be painful at first. It's important to dilate even if you have pain.

Alissa (nurse): Learning how to relax the muscles and breathe as you dilate will help. If you wish, you can take the pain medication recommended by your health care team before you dilate.

Narrator: Dilation requires time and privacy. Plan ahead so you have a private area at home or at work. Be sure to have your dilators, a mirror, water-based lubricant and towels available. Wash your hands and the dilators with warm soapy water, rinse well and dry on a clean towel. Use a water-based lubricant to moisten the rounded end of the dilators. Water-based lubricants are available over-the-counter. Do not use oil-based lubricants, such as petroleum jelly or baby oil. These can irritate the vagina. Find a comfortable position in bed or elsewhere. Use pillows to support your back and thighs as you lean back to a 45-degree angle. Start your dilation session with the smallest dilator. Hold a mirror in one hand. Use the other hand to find the opening of your vagina. Separate the skin. Relax through your hips, abdomen and pelvic floor. Take slow, deep breaths. Position the rounded end of the dilator with the lubricant at the opening to your vaginal canal. The rounded end should point toward your back. Insert the dilator. Go slowly and gently. Think of its path as a gentle curving swoop. The dilator doesn't go straight in. It follows the natural curve of the vaginal canal. Keep gentle down and inward pressure on the dilator as you insert it. Stop when the dilator's rounded end reaches the end of your vaginal canal. The dilators have dots or markers that measure depth. Hold the dilator in place in your vaginal canal. Use gentle but constant inward pressure for the correct amount of time at the right depth for you. If you're feeling pain, breathe and relax the muscles. When time is up, slowly remove the dilator, then repeat with the other dilators you need to use. Wash the dilators and your hands. If you have increased discharge following dilation, you may want to wear a pad to protect your clothing.

Jessi: I mean, it's such a strange, unfamiliar feeling to dilate and to have a dilator, you know to insert a dilator into your own vagina. Because it's not a pleasurable experience, and it's quite painful at first when you start to dilate. It feels much like a foreign body entering and it doesn't feel familiar and your body kind of wants to get it out of there. It's really tough at the beginning, but if you can get through the first month, couple months, it's going to be a lot easier and it's not going to be so much of an emotional and uncomfortable experience.

Narrator: You need to stay on schedule even when traveling. Bring your dilators with you. If your schedule at work creates challenges, ask your health care team if some of your dilation sessions can be done overnight.

Alissa (nurse): You can't skip days now and do more dilation later. You must do dilation on schedule to keep vaginal depth and width. It is important to dilate even if you have pain. Dilation should cause less pain over time.

Jessi: I hear that from a lot of other women that it's an overwhelming experience. There's lots of emotions that are coming through all at once. But at the end of the day for me, it was a very happy experience. I was glad to have the opportunity because that meant that while I have a vagina now, at the end of the day I had a vagina. Yes, it hurts, and it's not pleasant to dilate, but I have the vagina and it's worth it. It's a long process and it's not going to be easy. But you can do it.

Narrator: If you feel dilation may not be working or you have any questions about dilation, please talk with a member of your health care team.

Research has found that that gender-affirming surgery can have a positive impact on well-being and sexual function. It's important to follow your health care provider's advice for long-term care and follow-up after surgery. Continued care after surgery is associated with good outcomes for long-term health.

Before you have surgery, talk to members of your health care team about what to expect after surgery and the ongoing care you may need.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

Feminizing surgery care at Mayo Clinic

- Tangpricha V, et al. Transgender women: Evaluation and management. https://www.uptodate.com/ contents/search. Accessed Aug. 16, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Surgical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Coleman E, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2022; doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

- AskMayoExpert. Gender-affirming procedures (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- Nahabedian, M. Implant-based breast reconstruction and augmentation. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Medical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Ferrando C, et al. Gender-affirming surgery: Male to female. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Doctors & Departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

- +31 75 647 63 72

- [email protected]

- Forgot your password?

- Forgot your username?

- Sexual Health Q&A

What is gender reassignment surgery?

Reviewed by the medical professionals of the ISSM’s Communication Committee

Gender reassignment surgery, sometimes called sex reassignment surgery, is performed to transition individuals with gender dysphoria to their desired gender.

People with gender dysphoria often feel that they were born in the wrong gender. A biological male may identify more as a female and vice versa.

- Surgery is typically the last step in the physical transition process, but it is not a decision to be made lightly.

- Many healthcare providers require patients to be formally diagnosed with gender dysphoria and undergo counseling to determine if they are truly ready to surgically transition.

- Patients usually undergo hormone therapy first. Hormones can suppress the secondary sex characteristics of the biological gender and make them appear more like their desired sex. For instance, women take androgens and start developing facial hair. Men take estrogens and anti-androgens to look more feminine.

- Surgeons may also require that patients live as their desired gender for at least one year. A man might dress as a woman traditionally does in the culture. Many men change their names and refer to themselves with female pronouns. Women transitioning to men would do the reverse.

Surgical transition may include several procedures.

- Males transitioning to females have their testicles and penis removed. The prostate gland may or may not be removed as well. Tissue from the penis is used to construct a vagina and clitoris. Labia – the “lips” surrounding the vagina – can be made from scrotal skin. The urethra (the tube from which urine leaves the body) is shortened.

- Many biological men also have facial feminization surgery to change the appearance of their lips, eyes, nose, or Adam’s apple.

- After surgery, patients use vaginal dilators to keep the new vagina open and flexible.

- Surgery for females transitioning to males is more complicated and expensive. The breasts, ovaries, and uterus are removed and the vagina is closed. A penis and scrotum may be made from other tissue. In some cases, a penile implant is used. The urethra is extended so that the patient can urinate while standing.

Continued psychotherapy is recommended for most patients as they adjust to their new bodies and lifestyles.

Not all people with gender dysphoria have surgery. Some feel comfortable living as the opposite gender without medical intervention. Others find that hormone therapy is sufficient for their personal needs.

- Sexual Orientation & LGBTQIA+ Health

- Transgender Health

- Gender-Affirming Surgery

- Transgender Psychological Counseling

Popular Sexual Orientation & LGBTQIA+ Health Questions

What is the difference between transsexual and transgender, can transgender women have orgasms after gender-reassignment surgery.

Is it common for transgender people to regret gender-affirmation surgery?

- Sexual Health Topics

- Find a provider

- ISSM journals

- Upcoming Meetings

Members Only

Issm update.

- For providers

- ISSM Answers your Questions

- ISSM SEXTalks

- Find a Provider

- Affiliated Societies

- Past Presidents

- Executive Office

- Vision and Mission

- ISSM Advisory Council

- Bylaws Committee

- Communication Committee

- Consultation and Guidelines Committee

- Developing Countries Committee

- Education Committee

- Ethics Committee

- Finance & Audit Committee

- Grants & Prizes Committee

- History Committee

- Membership Committee

- Nominating Committee

- Publication Committee

- Scientific Committee

- Young Researchers Committee

- Young Trainees Committee

- ISSM Q&A Videos

What is Sex Change Surgery: Overview, Benefits, and Expected Results

The new product is a great addition to our lineup.

Our latest product is an exciting addition to our already impressive lineup! With its innovative features and sleek design, it's sure to be a hit with customers. Don't miss out on this amazing opportunity to upgrade your life!

- February 3, 2022

- Diseases Procedures

What is Sex Change Surgery? Overview, Benefits, and Expected Results

Overview of sex change surgery, benefits of sex change surgery.

- Improved self-acceptance and self-confidence

- Higher quality of life

- Healthier transformation of gender identity

- Increased self-expression and liberation

Practical Tips for Undergoing Sex Change Surgery

Expected results of sex change surgery.

- Altered physical characteristics, including genital surgical procedures (such as vaginoplasty, clitoroplasty, phalloplasty, and metoidioplasty), changes to reproductive anatomy, and breast augmentation or reduction

- Potential infertility related to changing or removing reproductive anatomy

- Facial feminization, voice deepening, or facial masculinization

- Potential changes to or widening of the hips and/or waist

- Piriformis muscle reconstruction

- Gender-affirming mammoplasty

Recovery Process of Sex Change Surgery

Important considerations for gender-affirmation surgery, definition & overview.

Sex change surgery, also known as gender reassignment or genital reconstruction surgery, is a surgical procedure that changes a person’s sexual structure, in terms of both appearance and function, from that of a man to a woman, or vice versa. It is also medically known as feminizing or masculinizing, genitoplasty, penectomy or vaginoplasty, orchiectomy, metoidioplasty, or phalloplasty, depending on the original and intended gender. It is taken advantage by transgender individuals to shift from their biological gender to their identified sex as a treatment for a condition known as gender dysphoria.

Who Should Undergo & Expected Results

Sex change surgery is performed on people who are identified as transgenders, which are referred to as transsexuals after the surgery. The surgery should only be performed on people who are mentally healthy, a state that will be determined by a mental health evaluation that is conducted prior to the surgery. It is also reserved for patients who are proven to have gender dysphoria, a medical condition that is formerly known as gender identity disorder. People with this condition feel that they should be of the opposite gender, and this feeling causes distress in their lives.

A sex change surgery is expected to reduce a person’s feelings of distress due to having a gender he or she does not identify or feel comfortable with. In some people, hormone therapy alone can achieve this, whereas in some people, minor gender-related surgeries suffice . If less major treatments do not relieve a person’s feelings of displacement due to gender, then sex reassignment surgery is considered.

How Does the Procedure Work?

The road to getting a sex change surgery begins with an evaluation of the patient’s mental health. This is conducted by a psychologist or a mental health specialist who has experience in dealing with gender issues. This medical professional will be the one to determine whether the person needs to be treated for gender dysphoria.

Also, prior to undergoing the actual procedure, the patient will be required to undergo hormone therapy. This is important because the gender of a person is not only determined by the appearance of his or her sexual structure. In fact, several factors that characterize a person based on his or her gender are controlled by hormones; these include the size of the breasts, hair growth in various parts of the body, and total muscle mass. Thus, before a person can change genders, the entire body has to be brought through a complete transition process that takes into consideration all the sexual characteristics of a person.

Women who wish to transition to becoming men need to take supplements of the male hormone, also called androgens. These hormones can gradually make their bodies look more masculine by enhancing muscle mass (and therefore strength), encouraging more hair growth in the body and also on the face, and deepening the voice. Androgen supplements can also cause an enlargement of the clitoris. On the other hand, supplementation of the female hormone will make a male patient more feminine by decreasing total muscle mass and strength, increasing breast size, slowing down the growth of facial and body hair, and altering the distribution of body fat. Changes brought about by hormone therapy usually begin to show after a month, but full effects can only be expected after 5 years.

The reason why hormone therapy has to be done prior to a sex change surgery is that, in some cases, it is usually adequate to ease a person’s feelings of gender confusion and thus relieve the distressing symptoms caused by gender dysphoria. Due to this, studies show that up to 75% of people suffering from gender dysphoria choose not to pursue the surgery itself as the hormone therapy has made them feel more balanced and less distressed regarding their gender.

Surgery, however, is the only remaining option if hormone therapy is deemed ineffective. Once all preparatory procedures such as mental health evaluation and hormone therapy are completed, the procedure is done by using the penis and the scrotum to reconstruct a vagina and vulva, or forming a new penis.

Possible Complications and Risks

A sex reassignment surgery is a major procedure that comes with significant risks. All patients are informed of these risks prior to the surgery. Apart from medical risks, the surgery also has some limitations, which should also be explained in detail to the patient before he or she provides consent for the surgery and all preceding treatments involved.

Some of the risks of the sex change procedure are due to the hormone therapy itself. These include:

- High blood pressure

- Sleep apnea

- Heart disease

- Tumors affecting the pituitary gland

- Infertility

- Uncontrolled weight gain

- High levels of liver enzymes

- Blood clots

- Feelings of uncertainty and confusion

Thus, people undergoing hormone therapy need to be constantly supervised by a medical professional, especially during the first months of the process, so that the effects of the hormones can be properly monitored.

Also, patients undergoing either hormone therapy or sex change surgery will benefit from ongoing counseling or continuous visits to their endocrinologist, a medical specialist focusing on the body’s hormones.

Also, it is important for patients to understand that the decision to pursue sex change surgery is a major and, in many cases, irreversible, so it should not be made lightly. The decision of the patient should be backed by the surgeon or psychologist handling his or her case. This is the reason why patients are required to undergo at least 12 months of hormone therapy before they are allowed to undergo a sex change surgery.

The surgery itself comes with the following risks, which depend on whether the patient is a male transitioning to female, or vice versa. For men who are changing into women, the risks involve:

- Death of the tissue that is used to create the vagina and vulva; this tissue is usually taken from the scrotum and penis

- Fistulas , which are abnormal connections between the vagina and the bladder or the bowels

- Narrowing of the urethra, which, in severe cases, can obstruct urine flow and increase a person’s risk of kidney damage

On the other hand, women transitioning into men are exposed to the following risks:

- Narrowing of the urinary tract with the same increased risk to the kidneys

- Death of the tissue in the newly formed penis

The risks are heightened in the case of women changing into men by having a new penis reconstructed. The increased risk is due to the many different stages of the surgery as well as the high rate of technical difficulties encountered so far in such surgeries. Due to this, some women only opt for the removal of their uterus and ovaries, and choose to forego phalloplasty.

Complications and risks can also be avoided by choosing minor sex change procedures, such as mastectomies for women who want to get rid of their breasts or breast augmentation for men who want to increase their breast size. Most patients feel that these procedures are enough and thus don’t feel the need to have their sexual genitals reconstructed. This is because breast augmentations and mastectomies can be reversed in case they change their mind after the procedures are done. References :

- Jamison Green, Ph.D., president, World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

- Sherman Leis, DO, surgeon, Philadelphia Center for Transgender Surgery.

- WPATH Standards of Care (SOC) for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender- Nonconforming People, Volume 7.

/trp_language]

One comment

Great article! Great info for anyone considering Sex Change Surgery

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Add Comment *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Posts

What is Acupuncture: Overview, Benefits, and Expected Results

- February 4, 2022

What is Application of Uniplane/Multiplane External Fixation System: Overview, Benefits, and Expected Results

What is 3d conformal radiotherapy: overview, benefits, and expected results, popular articles.

Gender reassignment surgery: an overview

Affiliation.

- 1 Gender Surgery Unit, Charing Cross Hospital, Imperial College NHS Trust, 179-183 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 8QZ, UK.

- PMID: 21487386

- DOI: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.46

Gender reassignment (which includes psychotherapy, hormonal therapy and surgery) has been demonstrated as the most effective treatment for patients affected by gender dysphoria (or gender identity disorder), in which patients do not recognize their gender (sexual identity) as matching their genetic and sexual characteristics. Gender reassignment surgery is a series of complex surgical procedures (genital and nongenital) performed for the treatment of gender dysphoria. Genital procedures performed for gender dysphoria, such as vaginoplasty, clitorolabioplasty, penectomy and orchidectomy in male-to-female transsexuals, and penile and scrotal reconstruction in female-to-male transsexuals, are the core procedures in gender reassignment surgery. Nongenital procedures, such as breast enlargement, mastectomy, facial feminization surgery, voice surgery, and other masculinization and feminization procedures complete the surgical treatment available. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health currently publishes and reviews guidelines and standards of care for patients affected by gender dysphoria, such as eligibility criteria for surgery. This article presents an overview of the genital and nongenital procedures available for both male-to-female and female-to-male gender reassignment.

Publication types

- Plastic Surgery Procedures / methods*

- Plastic Surgery Procedures / psychology

- Postoperative Complications / prevention & control

- Postoperative Complications / psychology

- Sex Reassignment Surgery / methods*

- Sex Reassignment Surgery / psychology

- Transsexualism / diagnosis

- Transsexualism / psychology

- Transsexualism / surgery*

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J R Soc Med

- v.110(4); 2017 Apr

Gender identity and the management of the transgender patient: a guide for non-specialists

Albert joseph.

1 Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Imperial College London, London W6 8RP, UK

Charlotte Cliffe

Miriam hillyard.

2 North West Thames Foundation School, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London W2 1NY, UK

Azeem Majeed

In this review, we introduce the topic of transgender medicine, aimed at the non-specialist clinician working in the UK. Appropriate terminology is provided alongside practical advice on how to appropriately care for transgender people. We offer a brief theoretical discussion on transgenderism and consider how it relates to broader understandings of both gender and disease. In respect to epidemiology, while it is difficult to assess the exact size of the transgender population in the UK, population surveys suggest a prevalence of between 0.2 and 0.6% in adults, with rates of referrals to gender identity clinics in the UK increasing yearly. We outline the legal framework that protects the rights of transgender people, showing that is not legal for physicians to deny transgender people access to services based on their personal beliefs. Being transgender is often, although not always, associated with gender dysphoria, a potentially disabling condition in which the discordance between a person’s natal sex (that assigned to them at birth) and gender identity results in distress, with high associated rates of self-harm, suicidality and functional impairment. We show that gender reassignment can be a safe and effective treatment for gender dysphoria with counselling, exogenous hormones and surgery being the mainstay of treatment. The role of the general practitioner in the management of transgender patients is discussed and we consider whether hormone therapy should be initiated in primary care in the absence of specialist advice, as is suggested by recent General Medical Council guidance.

Introduction

Transgender people, whose gender identities, expressions or behaviours differ from those predicted by their sex assigned at birth, are receiving increased attention both in the media and in the scientific press. Recent guidelines in the UK have proposed placing much of the responsibility of care for transgender patients on primary care physicians and their teams. 1 With waiting lists for most gender identity clinics extending beyond 12 months and increasing numbers of patients coming forward for treatment, hospital doctors are also likely to encounter transgender patients in their clinical practice.

Research in the area of transgender health is limited, but the emerging consensus is that many people identify as transgender, and that some of these individuals will suffer from an often distressing associated condition, gender dysphoria. 2 Appropriate treatment can lead to profound improvements in well-being. 2 Treatment is also largely safe and well tolerated but has some risks. 2 Transgender individuals may have unique health needs and expectations that health professionals need to be aware of to provide optimal care. In this essay, we introduce and outline this emerging field for physicians, not specialised in this area, aiming largely at a British audience but with relevance to non-specialists outside the UK.

This was a non-systematic review, utilising Google Scholar and PubMed searches to locate publications deemed to be relevant to the aims of this review, namely to provide a practical introduction to the field of transgender health for the non-specialist clinician. Both our literature search and decisions regarding what was included in the final manuscript were guided by discussions with general practitioners with experience managing transgender patients, gender identity specialists, public health professionals, academics working in the field of transgender studies and transgender patients with experience being treated in the NHS.

Terminology

It is important to know the accepted terminology when discussing gender identity and also to be aware that terms have changed throughout time and will continue to do so. A recent study of 166 medical students in the UK demonstrated a significant positive correlation between familiarity with relevant terminology and positive attitudes towards Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Queer patients. 3 Further studies demonstrate improvement in attitudes towards transgender individuals amongst healthcare professionals after education, suggesting that familiarity with terminology might help overcome negative preconceptions. 4 We provide a list of terms derived from the National Centre for Transgender Equality, split based on whether they are preferred at time of writing (Box 1). 5

There is an important distinction between transgender and the Disorders of Sex Development a (alternatively known as ‘intersex’), which is a term from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5. a Intersex encompasses a range of conditions where individuals are born with sexual anatomy and/or chromosomal or hormonal patterns not fitting stereotypical definitions of ‘male’ or ‘female’. In general, transgender individuals should be referred to by the pronoun of their current identified gender rather than their assigned gender at birth. If there is any confusion, it is sensible to clarify with a simple question such as ‘which pronouns do you use?’ 2 The answer may include gender-neutral pronouns such as ‘they’ or ‘ze’ rather than ‘she’ or ‘he’.

What is transgender?

Although frequently conflated, the terms sex and gender have different meanings. Sex is defined as the anatomical, genetic or gonadal dimorphism that typically allows individuals to be placed in one of two categories, ‘male’ or ‘female’. Gender, in contrast, relates to a person’s internal experience of ‘being masculine, feminine or androgynous. Rather than a binary concept, gender identity includes gradations of masculinity to femininity ... as well as identification as neither essentially male nor female’. 6 Although related, a person’s sex and gender are distinct from their sexual orientation – whether they are sexually attracted to men, women, both, neither and so on. In the majority of cases, a newborn is assigned as ‘male’ or ‘female’ at birth and a congruent gender identity and gender role of ‘boy’ or ‘girl’ usually forms, respectively. Gender roles are a set of often-stereotyped social and behavioural norms considered appropriate for persons of a specific sex, though these vary widely between and within cultures. Debate continues on the extent to which these gender roles are socially constructed – do typical men and women actually have inbuilt genetic or physiological differences leading to dimorphic sets of behaviours and personalities, or does differing socialisation usually lead to children internalising and ‘performing’ the correct gender roles?

Terms used in the field of transgender health.

Individuals whose gender identity and expression differs from their circumscribed categories of ‘male’ and ‘female’ have clearly existed throughout temporal and sociocultural contexts, and within the field of Western medicine, the term ‘transsexual’ or ‘transvestite’ was historically used to describe such individuals. ‘Transgender’ as a noun and later an adjective first gained prominence in the early 1990s, with the rise of transgender studies, which attempted to critically analyse and give a voice to the experiences of a coherent movement of individuals struggling to overcome marginalisation and political injustice. 7 In recent years, various theories of gender identity development have been advanced, ranging from ideas about an innate ‘brain sex’ (e.g. the brain of a trans woman might show more homology with that of a natally assigned woman than a natally assigned man) 8 to proposals that for at least some transgender people, the desire to become the ‘other’ gender results from a sense of erotic gratification. 9 Notions of binary, ‘biological’ sex may also be seen as social constructions. 6 What is clear is that gender identity arises from a complex interaction of biological, social and cultural factors and its aetiology is highly contentious area.

Transgender as a ‘disorder’

Complexities in understanding transgender are reflected in the difficulties labelling and classifying it. At present Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 and International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 include ‘gender dysphoria’ and ‘gender identity disorder’, respectively, under mental health conditions. However, it is likely International Classification of Diseases-11 will reclassify gender identity disorder as a sexual disorder. 10 This represents a profound shift in perspective: the transgender person no longer suffers because of pathological mental processes leading to a desire for an altered physical or social identity. The suffering occurs because non-pathological mental processes occur in the context of the ‘wrong’ physical body and a pathological social response to that body.

Gender dysphoria is, by definition, distressing, causing social and occupational dysfunction, is associated with a significant risk of suicide and self-harm 11 and can often be treated either medically or surgically. It is for these reasons that it is labelled as a disorder. But for those calling for the ‘depsychopathologisation’ of transgender, gender variance is viewed as a normal dimension of human experience with much of the suffering experienced by transgender people originating from social perspectives. 12 For the non-specialist clinician it is worthwhile bearing in mind that it is an area where numerous perspectives are likely to be encountered. As always sensitivity, empathy and respect when dealing with transgender patients is paramount.

Epidemiology

There are only limited data on the prevalence of transgender people. There are also challenges in defining the transgender community. Legally, the transition from one gender to another is formally enshrined through completion of a gender recognition certificate and as of 2014 only 3877 of these certificates had been issued in the UK. 13 It is likely however that gender recognition certificate figures grossly underestimate the size of the transgender community in the UK. By the year 2009 it was estimated that between 5000 and 6200 people had undergone gender reassignment surgery in the UK. 14 In the past decade, numbers of gender recognition certificate applications have fallen (likely due to cost and a complex administrative process), yet referrals to gender identity clinics have soared 15 ( Figure 1 ). In population surveys, estimates of prevalence of transgender in Western populations are higher than might be expected. A survey by Reed et al. 14 estimated that 0.2% of the British population in the over-16 age group identify as transgender, although these data did not undergo peer review before publication. In a recent large telephone survey carried out in the Unites States of America, 151,456 respondents were asked ‘do you consider yourself to be transgender?’ A total of 0.53% reported identifying as transgender and, through statistical extrapolation, the authors estimated a population prevalence of 0.6% in the United States (16).

Epidemiological trends: (a) Bar chart demonstrating increased referral to gender identity clinics across the UK, 2010–2016. The data were compiled as a part of a Guardian special report; data obtained from all gender identity clinics in UK except for Aberdeen under the Freedom of Information Act (15) and (b) government statistics demonstrate an increasing proportion of female to male vs female to male requests for gender recognition certificates between years 2005 and 2014. 13