- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Delimitations

Definition:

Delimitations refer to the specific boundaries or limitations that are set in a research study in order to narrow its scope and focus. Delimitations may be related to a variety of factors, including the population being studied, the geographical location, the time period, the research design , and the methods or tools being used to collect data .

The Importance of Delimitations in Research Studies

Here are some reasons why delimitations are important in research studies:

- Provide focus : Delimitations help researchers focus on a specific area of interest and avoid getting sidetracked by tangential topics. By setting clear boundaries, researchers can concentrate their efforts on the most relevant and significant aspects of the research question.

- Increase validity : Delimitations ensure that the research is more valid by defining the boundaries of the study. When researchers establish clear criteria for inclusion and exclusion, they can better control for extraneous variables that might otherwise confound the results.

- Improve generalizability : Delimitations help researchers determine the extent to which their findings can be generalized to other populations or contexts. By specifying the sample size, geographic region, time frame, or other relevant factors, researchers can provide more accurate estimates of the generalizability of their results.

- Enhance feasibility : Delimitations help researchers identify the resources and time required to complete the study. By setting realistic parameters, researchers can ensure that the study is feasible and can be completed within the available time and resources.

- Clarify scope: Delimitations help readers understand the scope of the research project. By explicitly stating what is included and excluded, researchers can avoid confusion and ensure that readers understand the boundaries of the study.

Types of Delimitations in Research

Here are some types of delimitations in research and their significance:

Time Delimitations

This type of delimitation refers to the time frame in which the research will be conducted. Time delimitations are important because they help to narrow down the scope of the study and ensure that the research is feasible within the given time constraints.

Geographical Delimitations

Geographical delimitations refer to the geographic boundaries within which the research will be conducted. These delimitations are significant because they help to ensure that the research is relevant to the intended population or location.

Population Delimitations

Population delimitations refer to the specific group of people that the research will focus on. These delimitations are important because they help to ensure that the research is targeted to a specific group, which can improve the accuracy of the results.

Data Delimitations

Data delimitations refer to the specific types of data that will be used in the research. These delimitations are important because they help to ensure that the data is relevant to the research question and that the research is conducted using reliable and valid data sources.

Scope Delimitations

Scope delimitations refer to the specific aspects or dimensions of the research that will be examined. These delimitations are important because they help to ensure that the research is focused and that the findings are relevant to the research question.

How to Write Delimitations

In order to write delimitations in research, you can follow these steps:

- Identify the scope of your study : Determine the extent of your research by defining its boundaries. This will help you to identify the areas that are within the scope of your research and those that are outside of it.

- Determine the time frame : Decide on the time period that your research will cover. This could be a specific period, such as a year, or it could be a general time frame, such as the last decade.

- I dentify the population : Determine the group of people or objects that your study will focus on. This could be a specific age group, gender, profession, or geographic location.

- Establish the sample size : Determine the number of participants that your study will involve. This will help you to establish the number of people you need to recruit for your study.

- Determine the variables: Identify the variables that will be measured in your study. This could include demographic information, attitudes, behaviors, or other factors.

- Explain the limitations : Clearly state the limitations of your study. This could include limitations related to time, resources, sample size, or other factors that may impact the validity of your research.

- Justify the limitations : Explain why these limitations are necessary for your research. This will help readers understand why certain factors were excluded from the study.

When to Write Delimitations in Research

Here are some situations when you may need to write delimitations in research:

- When defining the scope of the study: Delimitations help to define the boundaries of your research by specifying what is and what is not included in your study. For instance, you may delimit your study by focusing on a specific population, geographic region, time period, or research methodology.

- When addressing limitations: Delimitations can also be used to address the limitations of your research. For example, if your data is limited to a certain timeframe or geographic area, you can include this information in your delimitations to help readers understand the limitations of your findings.

- When justifying the relevance of the study : Delimitations can also help you to justify the relevance of your research. For instance, if you are conducting a study on a specific population or region, you can explain why this group or area is important and how your research will contribute to the understanding of this topic.

- When clarifying the research question or hypothesis : Delimitations can also be used to clarify your research question or hypothesis. By specifying the boundaries of your study, you can ensure that your research question or hypothesis is focused and specific.

- When establishing the context of the study : Finally, delimitations can help you to establish the context of your research. By providing information about the scope and limitations of your study, you can help readers to understand the context in which your research was conducted and the implications of your findings.

Examples of Delimitations in Research

Examples of Delimitations in Research are as follows:

Research Title : “Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Cybersecurity Threat Detection”

Delimitations :

- The study will focus solely on the use of artificial intelligence in detecting and mitigating cybersecurity threats.

- The study will only consider the impact of AI on threat detection and not on other aspects of cybersecurity such as prevention, response, or recovery.

- The research will be limited to a specific type of cybersecurity threats, such as malware or phishing attacks, rather than all types of cyber threats.

- The study will only consider the use of AI in a specific industry, such as finance or healthcare, rather than examining its impact across all industries.

- The research will only consider AI-based threat detection tools that are currently available and widely used, rather than including experimental or theoretical AI models.

Research Title: “The Effects of Social Media on Academic Performance: A Case Study of College Students”

Delimitations:

- The study will focus only on college students enrolled in a particular university.

- The study will only consider social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

- The study will only analyze the academic performance of students based on their GPA and course grades.

- The study will not consider the impact of other factors such as student demographics, socioeconomic status, or other factors that may affect academic performance.

- The study will only use self-reported data from students, rather than objective measures of their social media usage or academic performance.

Purpose of Delimitations

Some Purposes of Delimitations are as follows:

- Focusing the research : By defining the scope of the study, delimitations help researchers to narrow down their research questions and focus on specific aspects of the topic. This allows for a more targeted and meaningful study.

- Clarifying the research scope : Delimitations help to clarify the boundaries of the research, which helps readers to understand what is and is not included in the study.

- Avoiding scope creep : Delimitations help researchers to stay focused on their research objectives and avoid being sidetracked by tangential issues or data.

- Enhancing the validity of the study : By setting clear boundaries, delimitations help to ensure that the study is valid and reliable.

- Improving the feasibility of the study : Delimitations help researchers to ensure that their study is feasible and can be conducted within the time and resources available.

Applications of Delimitations

Here are some common applications of delimitations:

- Geographic delimitations : Researchers may limit their study to a specific geographic area, such as a particular city, state, or country. This helps to narrow the focus of the study and makes it more manageable.

- Time delimitations : Researchers may limit their study to a specific time period, such as a decade, a year, or a specific date range. This can be useful for studying trends over time or for comparing data from different time periods.

- Population delimitations : Researchers may limit their study to a specific population, such as a particular age group, gender, or ethnic group. This can help to ensure that the study is relevant to the population being studied.

- Data delimitations : Researchers may limit their study to specific types of data, such as survey responses, interviews, or archival records. This can help to ensure that the study is based on reliable and relevant data.

- Conceptual delimitations : Researchers may limit their study to specific concepts or variables, such as only studying the effects of a particular treatment on a specific outcome. This can help to ensure that the study is focused and clear.

Advantages of Delimitations

Some Advantages of Delimitations are as follows:

- Helps to focus the study: Delimitations help to narrow down the scope of the research and identify specific areas that need to be investigated. This helps to focus the study and ensures that the research is not too broad or too narrow.

- Defines the study population: Delimitations can help to define the population that will be studied. This can include age range, gender, geographical location, or any other factors that are relevant to the research. This helps to ensure that the study is more specific and targeted.

- Provides clarity: Delimitations help to provide clarity about the research study. By identifying the boundaries and limitations of the research, it helps to avoid confusion and ensures that the research is more understandable.

- Improves validity: Delimitations can help to improve the validity of the research by ensuring that the study is more focused and specific. This can help to ensure that the research is more accurate and reliable.

- Reduces bias: Delimitations can help to reduce bias by limiting the scope of the research. This can help to ensure that the research is more objective and unbiased.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Practical Research Guidance

"The publications and resources helped me get a first-class degree." – Joanna Dunlop, MBA.

Defining the boundaries of your thesis research problem

A common issue faced by many research students when writing their proposal , or starting their thesis or dissertation, is how to define the scope of their research. If you describe your research problem clearly, you will have a distinct task to focus on. If you, however, express it poorly, you could end up with vague aims and objectives , complex research questions or ambiguous hypotheses. When you have a well-defined research problem statement , you explicitly situate your thesis within its disciplinary field; one that is delineated by clear-cut borders. So, define a boundary for your research!

To ensure your research is confined to its discrete disciplinary field is to spend some time, early on, exploring and examining where the boundary for your research should lie. This boundary marks the outline of a ‘container’. One that separates what is relevant to your research (that is, the interior of the receptacle), from what is less relevant, or irrelevant (that is, the exterior). It highlights the parts of an issue, problem or situation that are significant for the study, while simultaneously downplaying those elements that are less important, or immaterial.

We can learn about setting boundaries from the great innovative thinker, Edward de Bono. In his seminal book, Lateral Thinking , de Bono suggested five simple steps to help you to define your boundary clearly:

- Step one is to write down an initial statement of the problem, or issue, in plain English. For example, ‘In what ways might we help people to do X?’. It is recommended not to think too deeply about this, as some of the best initial statements are often the first phrases that pop into your mind.

- Step two is to underline the key words , especially the verbs and nouns, from the initial statement. For example, continuing with the previous example, the key word is ‘help’.

- Step three is to examine each key word for any potential hidden assumptions. A useful way to do this is to replace the word in the sentence with a synonym or near-synonym. For example, to substitute ‘help’ with words like assist, boost or improve. This could be done using an online tool like thesauraus.com .

- Step four is to explore the choice of words that affect the meaning of the statement. For example, consider if the word ‘encourage’ makes more sense than ‘help’.

- Step five is to redefine the statement , using these synonyms, in a more effective manner. For example, ‘How can we encourage managers to improve X?’

The two statements are similar (that is, ‘in what ways might we help people to do X’ versus ‘how can we encourage managers to improve X?’). The latter statement is more precise than the former. This has been achieved by revising the original key words in a structured and systemised way. For instance, ‘in what ways might’ has been replaced with ‘how can’; ‘help’ has been reworded to ‘encourage’; and ‘do’ to ‘improve’.

In many cases, you may be trying to make the boundary lines of your research problem even more detailed and specific. This usually involves making the sentence shorter and paraphrasing, but you can also add phrases. For instance, denoting what is signified by the word ‘X’ (such as, in A company, in the B sector, in C country, over X date to Y date).

If you feel your boundary has become too exact or tight, you may want to loosen the parameters or relax the criteria. Some useful ways to widen the scope and broaden your definition are by:

- Using brainstorming to generate lists of issues or problems that might expand the boundary. For example, ‘what are the best ways to encourage in general?’

- Not-ing, that is, converting each key word to its negative. For example, ‘how can we not encourage?’

- Employing antonyms. For example, ‘how can we discourage?’

In practice, you may need to repeat de Bono’s five steps several times before you come up with a research problem statement that you are happy with. Bear in mind, as you do so, the intention is not to simply alter the statement. It is to bend meaning, so that you understand more clearly how the wording of the problem, or issue, affects the assumed boundary.

Need assistance with defining the boundaries of your thesis or dissertation research problem? Sue and Mark , the Directors of Thesis Upgrade, can help. So, contact us now!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Scope and Delimitations in Research

Delimitations are the boundaries that the researcher sets in a research study, deciding what to include and what to exclude. They help to narrow down the study and make it more manageable and relevant to the research goal.

Updated on October 19, 2022

All scientific research has boundaries, whether or not the authors clearly explain them. Your study's scope and delimitations are the sections where you define the broader parameters and boundaries of your research.

The scope details what your study will explore, such as the target population, extent, or study duration. Delimitations are factors and variables not included in the study.

Scope and delimitations are not methodological shortcomings; they're always under your control. Discussing these is essential because doing so shows that your project is manageable and scientifically sound.

This article covers:

- What's meant by “scope” and “delimitations”

- Why these are integral components of every study

- How and where to actually write about scope and delimitations in your manuscript

- Examples of scope and delimitations from published studies

What is the scope in a research paper?

Simply put, the scope is the domain of your research. It describes the extent to which the research question will be explored in your study.

Articulating your study's scope early on helps you make your research question focused and realistic.

It also helps decide what data you need to collect (and, therefore, what data collection tools you need to design). Getting this right is vital for both academic articles and funding applications.

What are delimitations in a research paper?

Delimitations are those factors or aspects of the research area that you'll exclude from your research. The scope and delimitations of the study are intimately linked.

Essentially, delimitations form a more detailed and narrowed-down formulation of the scope in terms of exclusion. The delimitations explain what was (intentionally) not considered within the given piece of research.

Scope and delimitations examples

Use the following examples provided by our expert PhD editors as a reference when coming up with your own scope and delimitations.

Scope example

Your research question is, “What is the impact of bullying on the mental health of adolescents?” This topic, on its own, doesn't say much about what's being investigated.

The scope, for example, could encompass:

- Variables: “bullying” (dependent variable), “mental health” (independent variable), and ways of defining or measuring them

- Bullying type: Both face-to-face and cyberbullying

- Target population: Adolescents aged 12–17

- Geographical coverage: France or only one specific town in France

Delimitations example

Look back at the previous example.

Exploring the adverse effects of bullying on adolescents' mental health is a preliminary delimitation. This one was chosen from among many possible research questions (e.g., the impact of bullying on suicide rates, or children or adults).

Delimiting factors could include:

- Research design : Mixed-methods research, including thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews and statistical analysis of a survey

- Timeframe : Data collection to run for 3 months

- Population size : 100 survey participants; 15 interviewees

- Recruitment of participants : Quota sampling (aiming for specific portions of men, women, ethnic minority students etc.)

We can see that every choice you make in planning and conducting your research inevitably excludes other possible options.

What's the difference between limitations and delimitations?

Delimitations and limitations are entirely different, although they often get mixed up. These are the main differences:

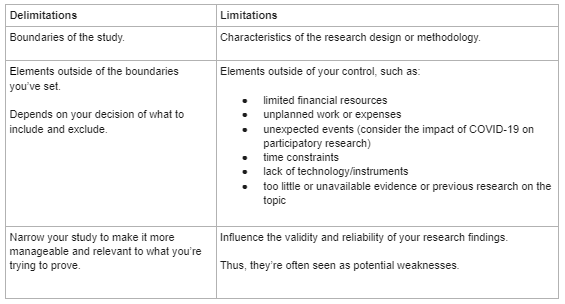

This chart explains the difference between delimitations and limitations. Delimitations are the boundaries of the study while the limitations are the characteristics of the research design or methodology.

Delimitations encompass the elements outside of the boundaries you've set and depends on your decision of what yo include and exclude. On the flip side, limitations are the elements outside of your control, such as:

- limited financial resources

- unplanned work or expenses

- unexpected events (for example, the COVID-19 pandemic)

- time constraints

- lack of technology/instruments

- unavailable evidence or previous research on the topic

Delimitations involve narrowing your study to make it more manageable and relevant to what you're trying to prove. Limitations influence the validity and reliability of your research findings. Limitations are seen as potential weaknesses in your research.

Example of the differences

To clarify these differences, go back to the limitations of the earlier example.

Limitations could comprise:

- Sample size : Not large enough to provide generalizable conclusions.

- Sampling approach : Non-probability sampling has increased bias risk. For instance, the researchers might not manage to capture the experiences of ethnic minority students.

- Methodological pitfalls : Research participants from an urban area (Paris) are likely to be more advantaged than students in rural areas. A study exploring the latter's experiences will probably yield very different findings.

Where do you write the scope and delimitations, and why?

It can be surprisingly empowering to realize you're restricted when conducting scholarly research. But this realization also makes writing up your research easier to grasp and makes it easier to see its limits and the expectations placed on it. Properly revealing this information serves your field and the greater scientific community.

Openly (but briefly) acknowledge the scope and delimitations of your study early on. The Abstract and Introduction sections are good places to set the parameters of your paper.

Next, discuss the scope and delimitations in greater detail in the Methods section. You'll need to do this to justify your methodological approach and data collection instruments, as well as analyses

At this point, spell out why these delimitations were set. What alternative options did you consider? Why did you reject alternatives? What could your study not address?

Let's say you're gathering data that can be derived from different but related experiments. You must convince the reader that the one you selected best suits your research question.

Finally, a solid paper will return to the scope and delimitations in the Findings or Discussion section. Doing so helps readers contextualize and interpret findings because the study's scope and methods influence the results.

For instance, agricultural field experiments carried out under irrigated conditions yield different results from experiments carried out without irrigation.

Being transparent about the scope and any outstanding issues increases your research's credibility and objectivity. It helps other researchers replicate your study and advance scientific understanding of the same topic (e.g., by adopting a different approach).

How do you write the scope and delimitations?

Define the scope and delimitations of your study before collecting data. This is critical. This step should be part of your research project planning.

Answering the following questions will help you address your scope and delimitations clearly and convincingly.

- What are your study's aims and objectives?

- Why did you carry out the study?

- What was the exact topic under investigation?

- Which factors and variables were included? And state why specific variables were omitted from the research scope.

- Who or what did the study explore? What was the target population?

- What was the study's location (geographical area) or setting (e.g., laboratory)?

- What was the timeframe within which you collected your data ?

- Consider a study exploring the differences between identical twins who were raised together versus identical twins who weren't. The data collection might span 5, 10, or more years.

- A study exploring a new immigration policy will cover the period since the policy came into effect and the present moment.

- How was the research conducted (research design)?

- Experimental research, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods research, literature review, etc.

- What data collection tools and analysis techniques were used? e.g., If you chose quantitative methods, which statistical analysis techniques and software did you use?

- What did you find?

- What did you conclude?

Useful vocabulary for scope and delimitations

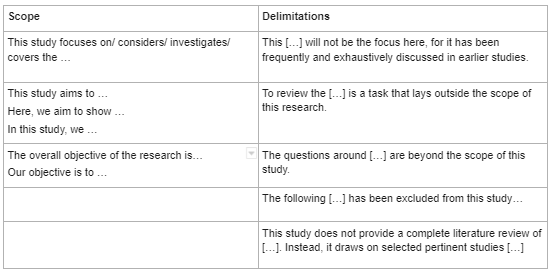

When explaining both the scope and delimitations, it's important to use the proper language to clearly state each.

For the scope , use the following language:

- This study focuses on/considers/investigates/covers the following:

- This study aims to . . . / Here, we aim to show . . . / In this study, we . . .

- The overall objective of the research is . . . / Our objective is to . . .

When stating the delimitations, use the following language:

- This [ . . . ] will not be the focus, for it has been frequently and exhaustively discusses in earlier studies.

- To review the [ . . . ] is a task that lies outside the scope of this study.

- The following [ . . . ] has been excluded from this study . . .

- This study does not provide a complete literature review of [ . . . ]. Instead, it draws on selected pertinent studies [ . . . ]

Analysis of a published scope

In one example, Simione and Gnagnarella (2020) compared the psychological and behavioral impact of COVID-19 on Italy's health workers and general population.

Here's a breakdown of the study's scope into smaller chunks and discussion of what works and why.

Also notable is that this study's delimitations include references to:

- Recruitment of participants: Convenience sampling

- Demographic characteristics of study participants: Age, sex, etc.

- Measurements methods: E.g., the death anxiety scale of the Existential Concerns Questionnaire (ECQ; van Bruggen et al., 2017) etc.

- Data analysis tool: The statistical software R

Analysis of published scope and delimitations

Scope of the study : Johnsson et al. (2019) explored the effect of in-hospital physiotherapy on postoperative physical capacity, physical activity, and lung function in patients who underwent lung cancer surgery.

The delimitations narrowed down the scope as follows:

Refine your scope, delimitations, and scientific English

English ability shouldn't limit how clear and impactful your research can be. Expert AJE editors are available to assess your science and polish your academic writing. See AJE services here .

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Stating the Obvious: Writing Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

During the process of writing your thesis or dissertation, you might suddenly realize that your research has inherent flaws. Don’t worry! Virtually all projects contain restrictions to your research. However, being able to recognize and accurately describe these problems is the difference between a true researcher and a grade-school kid with a science-fair project. Concerns with truthful responding, access to participants, and survey instruments are just a few of examples of restrictions on your research. In the following sections, the differences among delimitations, limitations, and assumptions of a dissertation will be clarified.

Delimitations

Delimitations are the definitions you set as the boundaries of your own thesis or dissertation, so delimitations are in your control. Delimitations are set so that your goals do not become impossibly large to complete. Examples of delimitations include objectives, research questions, variables, theoretical objectives that you have adopted, and populations chosen as targets to study. When you are stating your delimitations, clearly inform readers why you chose this course of study. The answer might simply be that you were curious about the topic and/or wanted to improve standards of a professional field by revealing certain findings. In any case, you should clearly list the other options available and the reasons why you did not choose these options immediately after you list your delimitations. You might have avoided these options for reasons of practicality, interest, or relativity to the study at hand. For example, you might have only studied Hispanic mothers because they have the highest rate of obese babies. Delimitations are often strongly related to your theory and research questions. If you were researching whether there are different parenting styles between unmarried Asian, Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic women, then a delimitation of your study would be the inclusion of only participants with those demographics and the exclusion of participants from other demographics such as men, married women, and all other ethnicities of single women (inclusion and exclusion criteria). A further delimitation might be that you only included closed-ended Likert scale responses in the survey, rather than including additional open-ended responses, which might make some people more willing to take and complete your survey. Remember that delimitations are not good or bad. They are simply a detailed description of the scope of interest for your study as it relates to the research design. Don’t forget to describe the philosophical framework you used throughout your study, which also delimits your study.

Limitations

Limitations of a dissertation are potential weaknesses in your study that are mostly out of your control, given limited funding, choice of research design, statistical model constraints, or other factors. In addition, a limitation is a restriction on your study that cannot be reasonably dismissed and can affect your design and results. Do not worry about limitations because limitations affect virtually all research projects, as well as most things in life. Even when you are going to your favorite restaurant, you are limited by the menu choices. If you went to a restaurant that had a menu that you were craving, you might not receive the service, price, or location that makes you enjoy your favorite restaurant. If you studied participants’ responses to a survey, you might be limited in your abilities to gain the exact type or geographic scope of participants you wanted. The people whom you managed to get to take your survey may not truly be a random sample, which is also a limitation. If you used a common test for data findings, your results are limited by the reliability of the test. If your study was limited to a certain amount of time, your results are affected by the operations of society during that time period (e.g., economy, social trends). It is important for you to remember that limitations of a dissertation are often not something that can be solved by the researcher. Also, remember that whatever limits you also limits other researchers, whether they are the largest medical research companies or consumer habits corporations. Certain kinds of limitations are often associated with the analytical approach you take in your research, too. For example, some qualitative methods like heuristics or phenomenology do not lend themselves well to replicability. Also, most of the commonly used quantitative statistical models can only determine correlation, but not causation.

Assumptions

Assumptions are things that are accepted as true, or at least plausible, by researchers and peers who will read your dissertation or thesis. In other words, any scholar reading your paper will assume that certain aspects of your study is true given your population, statistical test, research design, or other delimitations. For example, if you tell your friend that your favorite restaurant is an Italian place, your friend will assume that you don’t go there for the sushi. It’s assumed that you go there to eat Italian food. Because most assumptions are not discussed in-text, assumptions that are discussed in-text are discussed in the context of the limitations of your study, which is typically in the discussion section. This is important, because both assumptions and limitations affect the inferences you can draw from your study. One of the more common assumptions made in survey research is the assumption of honesty and truthful responses. However, for certain sensitive questions this assumption may be more difficult to accept, in which case it would be described as a limitation of the study. For example, asking people to report their criminal behavior in a survey may not be as reliable as asking people to report their eating habits. It is important to remember that your limitations and assumptions should not contradict one another. For instance, if you state that generalizability is a limitation of your study given that your sample was limited to one city in the United States, then you should not claim generalizability to the United States population as an assumption of your study. Statistical models in quantitative research designs are accompanied with assumptions as well, some more strict than others. These assumptions generally refer to the characteristics of the data, such as distributions, correlational trends, and variable type, just to name a few. Violating these assumptions can lead to drastically invalid results, though this often depends on sample size and other considerations.

Click here to cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Copyright © 2024 PhDStudent.com. All rights reserved. Designed by Divergent Web Solutions, LLC .

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

11. Setting the Boundaries of a Study

CHAPTER 11 Setting the Boundaries of a Study Chapter outline Why Set Boundaries to a Study? 142 Implications of Boundary Setting 143 Specifying the Scope of Participation: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria 144 General Guidelines for Bounding Studies 146 Subjects, Respondents, Informants, Participants, Locations, Conceptual Boundaries, Virtual Boundaries 146 Summary 147 Key terms Adequacy Appropriateness Boundary setting External validity Inclusion and exclusion criteria Informants Participants locations, conceptual boundaries, virtual boundaries Respondents Subjects Assume that you have a research problem and an appropriate design that matches your research purpose and question or query. You are now ready to consider how individuals, concepts, or locations will be selected for your study and how particular phenomena will be defined and identified. Selecting research participants, whether they are human or not, and identifying concepts and phenomena represent one of the first action processes that set or establish the boundaries or limitations of a study. Setting boundaries is inextricably linked to important ethical considerations, such as how people are selected for study participation, how they are informed of study procedures, how the information they share is managed and treated confidentially, and to whom or what the study results are applied. Because of the significance of the ethical component of boundary setting , we examine this in depth in Chapter 12 . Why set boundaries to a study? Setting limits or boundaries as to what and who will be in a study is an action that occurs in every type of research design, whether in the experimental-type or the naturalistic tradition. A researcher sets boundaries that limit the scope of the investigation to a specified group of individuals, phenomena, geography, or set of conceptual dimensions. The following example helps show why it is important to set boundaries or limitations. Consider a study that uses a survey design to describe the health and social service needs of “parents of children with intellectual impairments.” It would be impossible to interview every person who falls into this category in the United States. As the researcher, you need to make some decisions as to who you should specifically interview and how. One consideration may be to limit the survey to one or more particular geographic locations. Another way to limit the study may be to consider only certain types of conditions that fall under the rubric of intellectual impairment. Limiting the number of parents of children with intellectual impairments who are selected for study participation is an example of setting a boundary by restricting the characteristics of the persons who will be studied. Studies are also necessarily limited or bounded by identifying particular data collection strategies and concepts that will be considered. Assume you are interested in the historical development of your profession. It would not be feasible to examine every historical detail or written document to understand the sociopolitical and health care context of professional growth. In this case, you need to determine criteria for selecting historical documents to examine and identify the key historical events in which professional activity emerged. Deciding which historical documents to examine is an example of limiting your study by specifying the boundaries of the concept and time period that will be explored. There are numerous ways to limit the scope of a study. As discussed in previous chapters on the thinking processes of research, an investigator actively bounds a study on the basis of five interrelated considerations ( Box 11-1 ). BOX 11-1 Considerations in setting study boundaries 1. Researcher’s philosophical framework 2. Study purpose 3. Research question/query 4. Research design 5. Access to the object(s) of inquiry (participants, locations), investigator’s time frame, and monetary limitations Your philosophical approach or the particular research tradition you are using to develop your study will set the backdrop from which all action decisions will be made. A deductive, experimental-type study tightly bounds the study to preidentified concepts and a highly specified population. The purpose of the study, the particular research question, and the design will also shape the extent to which concepts, phenomena, and populations are delimited. For example, an intervention study that tests the effectiveness of a particular home care service in producing a specified outcome must carefully match the intent of the intervention with specific characteristics of the subject group or individuals who will be targeted and recruited for the study. Thus, identifying highly specified criteria as to who is eligible and who is not eligible to participate is a required action process. These criteria are referred to as “inclusion and exclusion criteria,” as discussed later. On the other hand, a broad inquiry designed to investigate the experiences of persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) may set few restrictions except diagnostic condition as to who can participate in the study and thus cast a wide net for participant enrollment. An investigator might even delimit a study by virtual location such as a listserv or virtual chat room for persons with AIDS. Finally, your ability to access the population of interest or the phenomenon to be studied is another consideration as to how a study is bounded. Limited resources, such as monetary and time restrictions, will likely yield a study design that is tightly delimited or bounded. Thus, there are both practical and theoretical considerations in how researchers bound the context of either an experimental-type or a naturalistic form of inquiry. In practical terms, it would be impossible to observe every speech event, personal interaction, image, or activity in a particular natural setting. You must bound the study by making purposeful selections as to what will be observed and who will be interviewed. 1, 2 In experimental-type designs, boundary setting is a process that must occur before entering the field or beginning the study. Boundaries are set in three ways: (1) specifying the concepts that will be operationally defined, (2) establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria that define the population that will be studied, and (3) developing a sampling plan. This set of action processes in naturalistic designs differs from those in the experimental-type tradition. Naturalistic boundary setting may occur throughout the research endeavor depending on how the dynamic design unfolds. Initial boundaries are set by the investigator through defining the particular domain of interest and the point of access from which to enter that domain. This domain may be (1) geographic, as in the selection of an urban community in which to study health behaviors of low-income families; (2) a group of individuals, such as the selection of persons with a particular health condition (e.g., stroke, diabetes, traumatic brain injury), living in an identified community; or (3) a particular experience, such as trauma, dialysis, caregiving, pain, or chronic health problems.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- 2. Essentials of Research

- 4. Framing the Problem

- 3. Philosophical Foundations

- 13. Boundary Setting in Experimental-Type Designs

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

How to Write the Scope of the Study

- By DiscoverPhDs

- August 26, 2020

What is the Scope of the Study?

The scope of the study refers to the boundaries within which your research project will be performed; this is sometimes also called the scope of research. To define the scope of the study is to define all aspects that will be considered in your research project. It is also just as important to make clear what aspects will not be covered; i.e. what is outside of the scope of the study.

Why is the Scope of the Study Important?

The scope of the study is always considered and agreed upon in the early stages of the project, before any data collection or experimental work has started. This is important because it focuses the work of the proposed study down to what is practically achievable within a given timeframe.

A well-defined research or study scope enables a researcher to give clarity to the study outcomes that are to be investigated. It makes clear why specific data points have been collected whilst others have been excluded.

Without this, it is difficult to define an end point for a research project since no limits have been defined on the work that could take place. Similarly, it can also make the approach to answering a research question too open ended.

How do you Write the Scope of the Study?

In order to write the scope of the study that you plan to perform, you must be clear on the research parameters that you will and won’t consider. These parameters usually consist of the sample size, the duration, inclusion and exclusion criteria, the methodology and any geographical or monetary constraints.

Each of these parameters will have limits placed on them so that the study can practically be performed, and the results interpreted relative to the limitations that have been defined. These parameters will also help to shape the direction of each research question you consider.

The term limitations’ is often used together with the scope of the study to describe the constraints of any parameters that are considered and also to clarify which parameters have not been considered at all. Make sure you get the balance right here between not making the scope too broad and unachievable, and it not being too restrictive, resulting in a lack of useful data.

The sample size is a commonly used parameter in the definition of the research scope. For example, a research project involving human participants may define at the start of the study that 100 participants will be recruited. This number will be determined based on an understanding of the difficulty in recruiting participants to studies and an agreement of an acceptable period of time in which to recruit this number.

Any results that are obtained by the research group can then be interpreted by others with the knowledge that the study was capped to 100 participants and an acceptance of this as a limitation of the study. In other words, it is acknowledged that recruiting 100 rather than 1,000 participants has limited the amount of data that could be collected, however this is an acceptable limitation due to the known difficulties in recruiting so many participants (e.g. the significant period of time it would take and the costs associated with this).

Example of a Scope of the Study

The follow is a (hypothetical) example of the definition of the scope of the study, with the research question investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health.

Whilst the immediate negative health problems related to the COVID-19 pandemic have been well documented, the impact of the virus on the mental health (MH) of young adults (age 18-24 years) is poorly understood. The aim of this study is to report on MH changes in population group due to the pandemic.

The scope of the study is limited to recruiting 100 volunteers between the ages of 18 and 24 who will be contacted using their university email accounts. This recruitment period will last for a maximum of 2 months and will end when either 100 volunteers have been recruited or 2 months have passed. Each volunteer to the study will be asked to complete a short questionnaire in order to evaluate any changes in their MH.

From this example we can immediately see that the scope of the study has placed a constraint on the sample size to be used and/or the time frame for recruitment of volunteers. It has also introduced a limitation by only opening recruitment to people that have university emails; i.e. anyone that does not attend university will be excluded from this study.

This may be an important factor when interpreting the results of this study; the comparison of MH during the pandemic between those that do and do not attend university, is therefore outside the scope of the study here. We are also told that the methodology used to assess any changes in MH are via a questionnaire. This is a clear definition of how the outcome measure will be investigated and any other methods are not within the scope of research and their exclusion may be a limitation of the study.

The scope of the study is important to define as it enables a researcher to focus their research to within achievable parameters.

This post explains the difference between the journal paper status of In Review and Under Review.

The scope of the study is defined at the start of the study. It is used by researchers to set the boundaries and limitations within which the research study will be performed.

If you’re about to sit your PhD viva, make sure you don’t miss out on these 5 great tips to help you prepare.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

Scientific misconduct can be described as a deviation from the accepted standards of scientific research, study and publication ethics.

Akshay is in the final year of his PhD researching how well models can predict Indian monsoon low-pressure systems. The results of his research will help improve disaster preparedness and long-term planning.

Ryan is in the final write up stages of his PhD at the University of Southampton. His research is on understanding narrative structure, media specificity and genre in transmedia storytelling.

Join Thousands of Students

Setting Limits and Focusing Your Study: Exploring scope and delimitation

As a researcher, it can be easy to get lost in the vast expanse of information and data available. Thus, when starting a research project, one of the most important things to consider is the scope and delimitation of the study. Setting limits and focusing your study is essential to ensure that the research project is manageable, relevant, and able to produce useful results. In this article, we will explore the importance of setting limits and focusing your study through an in-depth analysis of scope and delimitation.

Company Name 123

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, cu usu cibo vituperata, id ius probo maiestatis inciderint, sit eu vide volutpat.

Sign Up for More Insights

Table of Contents

Scope and Delimitation – Definition and difference

Scope refers to the range of the research project and the study limitations set in place to define the boundaries of the project and delimitation refers to the specific aspects of the research project that the study will focus on.

In simpler words, scope is the breadth of your study, while delimitation is the depth of your study.

Scope and delimitation are both essential components of a research project, and they are often confused with one another. The scope defines the parameters of the study, while delimitation sets the boundaries within those parameters. The scope and delimitation of a study are usually established early on in the research process and guide the rest of the project.

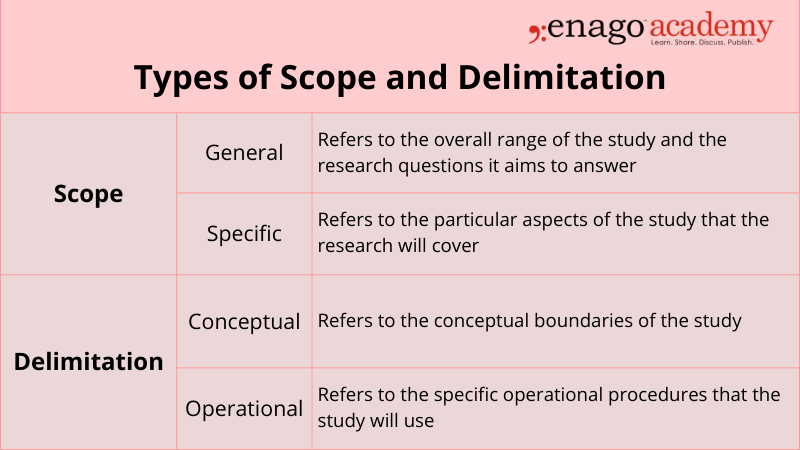

Types of Scope and Delimitation

Significance of Scope and Delimitation

Setting limits and focusing your study through scope and delimitation is crucial for the following reasons:

- It allows researchers to define the research project’s boundaries, enabling them to focus on specific aspects of the project. This focus makes it easier to gather relevant data and avoid unnecessary information that might complicate the study’s results.

- Setting limits and focusing your study through scope and delimitation enables the researcher to stay within the parameters of the project’s resources.

- A well-defined scope and delimitation ensure that the research project can be completed within the available resources, such as time and budget, while still achieving the project’s objectives.

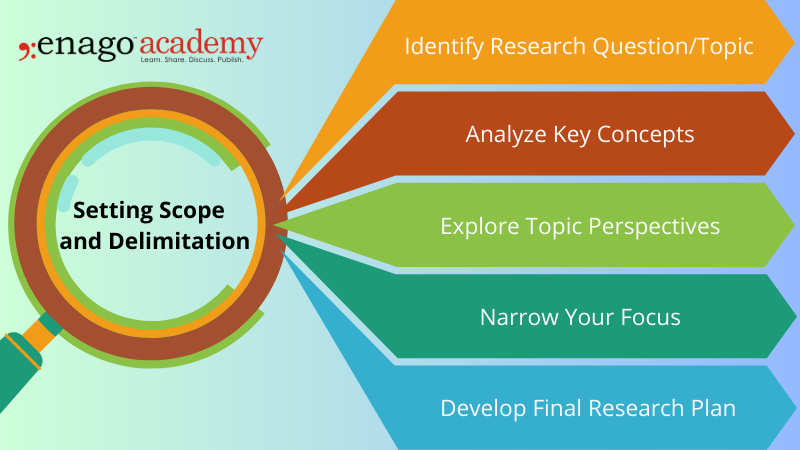

5 Steps to Setting Limits and Defining the Scope and Delimitation of Your Study

There are a few steps that you can take to set limits and focus your study.

1. Identify your research question or topic

The first step is to identify what you are interested in learning about. The research question should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). Once you have a research question or topic, you can start to narrow your focus.

2. Consider the key terms or concepts related to your topic

What are the important terms or concepts that you need to understand in order to answer your research question? Consider all available resources, such as time, budget, and data availability, when setting scope and delimitation.

The scope and delimitation should be established within the parameters of the available resources. Once you have identified the key terms or concepts, you can start to develop a glossary or list of definitions.

3. Consider the different perspectives on your topic

There are often different perspectives on any given topic. Get feedback on the proposed scope and delimitation. Advisors can provide guidance on the feasibility of the study and offer suggestions for improvement.

It is important to consider all of the different perspectives in order to get a well-rounded understanding of your topic.

4. Narrow your focus

Be specific and concise when setting scope and delimitation. The parameters of the study should be clearly defined to avoid ambiguity and ensure that the study is focused on relevant aspects of the research question.

This means deciding which aspects of your topic you will focus on and which aspects you will eliminate.

5. Develop the final research plan

Revisit and revise the scope and delimitation as needed. As the research project progresses, the scope and delimitation may need to be adjusted to ensure that the study remains focused on the research question and can produce useful results. This plan should include your research goals, methods, and timeline.

Examples of Scope and Delimitation

To better understand scope and delimitation, let us consider two examples of research questions and how scope and delimitation would apply to them.

Research question: What are the effects of social media on mental health?

Scope: The scope of the study will focus on the impact of social media on the mental health of young adults aged 18-24 in the United States.

Delimitation: The study will specifically examine the following aspects of social media: frequency of use, types of social media platforms used, and the impact of social media on self-esteem and body image.

Research question: What are the factors that influence employee job satisfaction in the healthcare industry?

Scope: The scope of the study will focus on employee job satisfaction in the healthcare industry in the United States.

Delimitation: The study will specifically examine the following factors that influence employee job satisfaction: salary, work-life balance, job security, and opportunities for career growth.

Setting limits and defining the scope and delimitation of a research study is essential to conducting effective research. By doing so, researchers can ensure that their study is focused, manageable, and feasible within the given time frame and resources. It can also help to identify areas that require further study, providing a foundation for future research.

So, the next time you embark on a research project, don’t forget to set clear limits and define the scope and delimitation of your study. It may seem like a tedious task, but it can ultimately lead to more meaningful and impactful research. And if you still can’t find a solution, reach out to Enago Academy using #AskEnago and tag @EnagoAcademy on Twitter , Facebook , and Quora .

Frequently Asked Questions

The scope in research refers to the boundaries and extent of a study, defining its specific objectives, target population, variables, methods, and limitations, which helps researchers focus and provide a clear understanding of what will be investigated.

Delimitation in research defines the specific boundaries and limitations of a study, such as geographical, temporal, or conceptual constraints, outlining what will be excluded or not within the scope of investigation, providing clarity and ensuring the study remains focused and manageable.

To write a scope; 1. Clearly define research objectives. 2. Identify specific research questions. 3. Determine the target population for the study. 4. Outline the variables to be investigated. 5. Establish limitations and constraints. 6. Set boundaries and extent of the investigation. 7. Ensure focus, clarity, and manageability. 8. Provide context for the research project.

To write delimitations; 1. Identify geographical boundaries or constraints. 2. Define the specific time period or timeframe of the study. 3. Specify the sample size or selection criteria. 4. Clarify any demographic limitations (e.g., age, gender, occupation). 5. Address any limitations related to data collection methods. 6. Consider limitations regarding the availability of resources or data. 7. Exclude specific variables or factors from the scope of the study. 8. Clearly state any conceptual boundaries or theoretical frameworks. 9. Acknowledge any potential biases or constraints in the research design. 10. Ensure that the delimitations provide a clear focus and scope for the study.

What is an example of delimitation of the study?

Thank you 💕

Thank You very simplified🩷

Thanks, I find this article very helpful

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Science under Surveillance: Journals adopt advanced AI to uncover image manipulation

Journals are increasingly turning to cutting-edge AI tools to uncover deceitful images published in manuscripts.…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A Guide to Setting Better Boundaries

When we define what we need to feel secure, we can do wonders for our well-beings.

Boundaries are limits we identify for ourselves, and apply through action or communication. When we define what we need to feel secure and healthy, when we need it, and create tools to protect those parts of ourselves, we can do wonders for our well-being at work and at home — which, in turn, allows us to bring our best selves to both places. Here’s how to boundaries in healthy ways:

- First, figure out your “hard” and “soft” boundaries. Hard boundaries are your non-negotiables. Soft boundaries are goals that you want to reach but are flexible around. Knowing the difference will allow you to make choices that are aligned with your deepest needs and manage your energy as you work towards the rest.

- Try this exercise: Imagine that your life, as it is right now, is no longer possible. Say you get laid off, you can’t live in the town you live in, or you’re forced to change careers. What would do next? Would you miss? What would you not miss? Your answers will reveal your high-level priorities.

- Practice setting one hard boundary to protect your high-level priorities by limiting interactions or activities that are not the best use of your time. For example, if your high-level priority is to be less drained after work, cut back on a few energy-draining tasks.

- Next, think about your aspirations. Are there soft boundaries you can set to feel more productive, creative, and rested at work and at home? Test them out.

- Pay attention to how these behavioral changes make you feel. What boundaries do you want to stick with? What do you need to adjust? As you experiment, remember that the process is fluid, and may change over time.

Where your work meets your life. See more from Ascend here .

Like exercise, meditation, or budgeting, most of us know that having boundaries around our work and our home lives is something we should probably do. Even so, finding the time to change unhealthy behaviors, learn, and build new habits is easier said than done.

- JS Joe Sanok is the host of the popular The Practice of the Practice podcast which is recognized as one of the Top 50 Podcasts worldwide with over 100,000 downloads each month. Bestselling authors, experts and scholars, and business leaders and innovators are featured and interviewed in the 550 plus podcasts he has done over the last six years. He is originally from Traverse City, MI. You can learn more about his work and find additional resources by visiting his website here .

Partner Center

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE Open Nurs

- v.5; Jan-Dec 2019

Problematizing Boundaries of Care Responsibility in Caring Relationships

Margareth kristoffersen.

1 Department of Care and Ethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Stavanger, Norway

Introduction

Nursing care takes place within nurse–patient relationships that can be demanding. In exceptional circumstances, the relationship may be destructive, and when this happens, significant onerous demands, appeals, or challenges can arise from patients and be placed upon nurses.

The aim is to explore what can be termed boundaries of care responsibility when relationships with patients place significant destructive demands on nurses.

Based on a hermeneutical approach, this study introduces aspects of phenomenological philosophy as described by the Danish theologian and philosopher Knud E. Løgstrup and provides examples of nurses’ experiences in everyday nursing practice drawn from a Norwegian empirical study focusing on remaining in everyday nursing practice. Data in that original study consisted of qualitative interviews and qualitative follow-up interviews with 13 nurses working in somatic and psychiatric health service.

The exploration of empirical examples demonstrates that nurses consider confronting demands from patients which manifest themselves as onerous and that they have to set limits to safeguard themselves. When the nurses had to manage acting out or actions from patients by opposing what was said and done, they experienced the situation as more than very unpleasant or connected to a perversion. Significant destructive caring relationships cannot be without boundaries, and explicating boundaries are of relevance to protect nurses from onerous demands. Protecting them implies reducing a hazard, that is, that nurses carry on even when this may be unhealthy for them.

Consistently pinpointing boundaries between demands is assumed to be essential in caring relationships, as onerous or destructive demands are strongly connected to a content where boundlessness is involved. To protect both nurses and patients as valued human beings, thus raising and preserving the status of the nurse and the patient, the nature and possible detrimental effects of destructive caring relationships should be considered and examined.

Patients can place significant and onerous demands upon nurses ( Franz, Zeh, Schablon, Kuhnert, & Nienhaus, 2010 ; Kristoffersen, 2013 ; Kristoffersen & Friberg, 2017 ). Research has documented that these demands which can be understood as destructive demands, appeals, or challenges manifest in caring relationships worldwide ( Spector, Zhou, & Che, 2014 ) and are most obvious or substantive when patients are very ill or cognitively impaired ( Gjerberg, Hem, Førde, & Pedersen, 2013 ; Ünsal Atan et al., 2013 ). At such times, strong emotions can sway, dominate, or steer their behavior ( Hem, Nortvedt, & Heggen, 2008 ). Demands may further be heightened when patients who are dependent on nursing care react negatively against or resist what nurses suggest they should do or consider ( Gacki-Smith et al., 2009 ; Gjerberg et al., 2013 ; Pich, Hazelton, Sundin, & Kable, 2010 ). In extreme situations, patients behaved aggressively and menacingly or direct abusive actions outwards at nurses ( Blair, 1991 ; Carlsson, Dahlberg, & Drew, 2000 ; Finnema, Dassen, & Halfsens, 1994 ; Jackson, Hutchinson, Luck, & Wilkes, 2013 ; Lovell & Skellern, 2013 ) or inwards at themselves ( Baker, Wright, & Hansen, 2013 ; Wilstrand, Lindgren, Gilje, & Olafsson, 2007 ). There is little agreement about what violence or aggression involves or includes and excludes in relation to nursing care ( Child & Mentes, 2010 ; Luck, Jackson, & Usher, 2008 ). However, verbal abuse is proposed to be a common form of violence directed at nurses ( Gacki-Smith et al., 2009 ; Stone, McMillan, Hazelton, & Clayton, 2011 ).

Research has further documented that nurses are aware of and acknowledge threats to their physical and psychological safety ( Carlsson et al., 2000 ) and recognize that unpleasant and occasionally dangerous relationships with patients may be a part of nursing ( Franz et al., 2010 ; Kristoffersen, 2013 ; Kristoffersen & Friberg, 2017 ; Kristoffersen, Friberg, & Brinchmann, 2016 ). Psychiatric nurses in particular work in and through relationally challenging situations, and violence or the threat of violence is frequently present ( Yang, Stone, Petrini, & Morris, 2018 ). In response to violence or its threat, coercive behavior on the part of nurses is sometimes required and can be different kinds of restrictive measures, for example, physical restraints as belts ( Hem, Gjerberg, Lossius Husum, & Pedersen, 2018 ; Sheehan & Burns, 2011 ). However, de-escalation and other alternatives to coercion are preferred ( Gjerberg et al., 2013 ). This involves nurses purposefully seeking to build therapeutic relationships with patients through the use of strategically directed talk and touch ( Baker et al., 2013 ; Finnema et al., 1994 ). Nurses also respond to patient needs in creative ways that allow or attempt to permit nurse–patient encounters that fully recognize the personality and humanity of patients ( Carlsson et al., 2000 ; Solvoll & Lindseth, 2016 ; Wilstrand et al., 2007 ). In these encounters, it is often the small things that make the biggest difference ( Skorpen, Rehnsfeldt, & Arstad Thorsen, 2015 ). Small things may include spending time with the patients or human finesses such as removing identification tags when patients and nurses are out of the hospital ( Skorpen et al., 2015 ).

Research has nevertheless documented that nurses have persistent and real concerns about the burden that demanding relationship work places upon them ( Baker et al., 2013 ; Ünsal Atan et al., 2013 ; Wilstrand et al., 2007 ). The capability of nurses to endure has been questioned, and when overwhelming loads are placed on nurses, they can fail to adequately care for themselves and also lose their principal focus on patient care ( Kristoffersen & Friberg, 2017 ; Molin, Hällgren Graneheim, Ringnér, & Lindgren, 2016 ). In such circumstances, it might be prudent for nurses experiencing moral distress ( Jameton, 1984 ) to set aside intentions to fully care for patients ( Varcoe, Pauly, Storch, Newton, & Makaroff, 2012 ). Demanding forms of relations may also be exacerbated when, from the patient’s perspective, nurses deliberately confront or cross patient beliefs in a manner that undermines patient understandings of their personal worth ( Hem, 2008 ).

To summarize, a considerable body of nursing research highlights the ways in which nursing practice can be experienced as unpleasant and dangerous. Nurses regularly expose themselves to relationships with patients who occasionally embody demands that may be perceived as destructive to the personal worth or integrity of the nurse. However, few studies have sought to explore the boundaries or limits of nurse–patient relations where those relations negatively and significantly impact upon nurses. This problem clearly raises difficult moral and professional issues. It is nonetheless important to discuss where boundaries are laying in nurse–patient relations.

The aim was to explore what can be termed boundaries of care responsibility when the caring relationship places significant destructive demands on nurses.

The Danish theologian and philosopher Knud E. Løgstrup (1997) describes a “demand” as an appeal or a challenge. A demand incorporates that we are the object of an appeal or a challenge, an appeal from another person or a challenge implicit in the situation itself ( Løgstrup, 1997 , p. 148). Although demands can be unspoken and cannot always be equated with a person’s expressed wish or request, they are nonetheless connected to situations in which we are involved. We are the object because something is demanded of us. Demands arise from the fact that human beings are seen as intertwined. According to Løgstrup (1997 ), demands rest on relationality or the assumption that we are mutually dependent of one another and know what is in the other person’s best interests and must thus take care of whatever in the other person’s life depends upon us. This means that demands are radical and one sided. Løgstrup (1997) states that demands receive this radicality from the understanding that we can never demand something in return for what we do (p. 123). Løgstrup (1997) points out that demands can be described either as an ethical demand or a destructive demand.

Boundaries Between Demands

There is no absolute demarcation line between an ethical demand and a destructive demand. Løgstrup (1997) argues that boundaries between ethical and destructive demands are fluid because our ability to determine another person’s fate as well as our inability to determine how that other person will react to his or her fate are unsolidified. It is nonetheless possible to indicate some boundaries by relating to the content of demands.

One basic boundary between ethical and destructive demands can be perceived as a content where caring responsibility for another person’s life implies excluding all reciprocity. The most obvious reason for indicating this is Løgstrup’s (1997) emphasis on the aspect of reciprocity. He connects reciprocity to relationality, which implies a reciprocal demand that we care for the other’s life. The demand rests on reciprocity as we are delivered over to one other. This means that reciprocity regulates our mutual life and we cannot necessarily exclude reciprocity to the point where we are solely oriented to the other person. Løgstrup (1997) states that excluding a claim of reciprocity does not mean that care for the other’s life consists in words or deeds which prevent his or her discovering that he or she has received his or her life as a gift (p. 117). The point is that the one placed under the demand should also receive from life. When we care for others, it is not only that person’s life which succeeds, but our own as well (1997, p. 124). Løgstrup (1997) explicates that this is implied in the demands own understanding, otherwise, there would be no difference between goodness and wickedness (pp. 117–118).

Løgstrup (1997) clarifies that a demand is destructive when the other person is not able to live at all except by the sacrifice the person under the demand makes, and the care of the other person’s life requires my self-destruction and self-annihilation (p. 137). For Løgstrup, such a radical one-sided content makes a demand destructive, as it requires the person placed under it to be willing to give up his or her life altogether. In the struggle between expectations of life and the care of the other person’s life, this means that expectations must give way. It involves self-destruction and self-annihilation having been an independent goal. However, Løgstrup (1997) underlines that such an extreme situation may mean that my own life cannot succeed through my having taken care of it and then the other person cannot belong to my own world as a vital part of it (pp. 137–138).

Boundlessness

A more definite boundary between ethical and destructive demands relates to boundlessness. Løgstrup (1997) describes boundlessness as being robbed of independence, and he forbids that we ever attempt, even for his or her own sake, to rob him or her of his or her independence. Responsibility for the other person never consists in our assuming the responsibility which is his or hers (p. 28).

By underlining that boundlessness involves assuming responsibility for what is beyond one’s power to control, Løgstrup (1997) explicates that it includes taking responsibility to the point of having no limits and, in the worst case, leads to encroachment. The human being is then subject to exploitation by another person in an unlimited way. This means that when our taking care of the other person is not coupled with what Løgstrup (1997) describes as a willingness to let him or her remain sovereign in his or her own world, it excludes a wish that our life will be successful and fulfilled. Thus, the result instead is that we experience disappointed expectations of life.

More concretely, Løgstrup (1997) connects boundlessness to perversions which can occur related to what we say and what we do in human relationships, implying we are caught in a conflict between regard and disregard for the other person. He terms one such form of boundlessness as a passing mood. This form is characterized by indulgence, compliance, and flattering regard, where the final result is that the other person is not cared for. Løgstrup (1997) terms another form of boundlessness as our wanting to change the other. He characterizes this as an interest in our own outlook, which can turn into arrogance and possibly encroachment upon others.

Material and Method

Aspects of Løgstrup’s (1997) work, the linking of destructive demands and their refutation, were used as analytical tools to explore empirical examples describing how nurses expressed their experiences of demands placed upon them by patients. The empirical examples and the philosophical texts were read several times, the analytical exploration being carried out using a back and forth reading approach with an open attitude to get an understanding of the examples in relation to the philosophy. A more in-depth understanding of the empirical examples emerged, resulting in the description of two themes. This implies that the study’s exploration was based on a hermeneutical approach ( Taylor, 1999 ).

The findings of a larger Norwegian study focusing on remaining in everyday nursing practice ( Kristoffersen, 2013 ) inspired exploration of what can be termed boundaries of care responsibility, and the empirical examples used in this study were considered relevant in interpreting such boundaries. The participants were 13 nurses, aged from 26 to 62 years, with a minimum of 2 years’ nursing experience in full or almost full-time work within primary and secondary somatic and psychiatric health-care services. Data included qualitative interviews and follow-up interviews (27 in total). Follow-up interviews were used to deepen and broaden information regarding perceptions of everyday experience ( Kvale & Brinkman, 2009 ; Silverman, 2006 ). The phenomenological hermeneutic analysis took the form of narrative reading, the composition of alternative thematic readings, and a comprehensive understanding ( Lindseth & Norberg, 2004 ).

Ethical Considerations

The empirical examples are drawn from the larger empirical study which was approved by the Norwegian Center for Research Data (NSD; Kristoffersen, 2013 ). The participants were given written information about the study, and their consent was obtained before data collection occurred. Permission to proceed using anonymized data was given by NSD, so the participants were not contacted about this again.

Exploring Boundaries of Care Responsibility in Relation to Empirical Examples of Demands in Everyday Nursing Practice

The examples demonstrated that nurses consider confronting demands from patients which manifest themselves as more or less onerous and that they have to set limits.

Considering Confronting Onerous Demands

Boundaries between demands can go unheeded, meaning that a line is crossed between ethical demands and destructive demands. Demands from patients can then manifest themselves in everyday nursing practice as more or less onerous. One psychiatric nurse said:

A patient jumped up at a colleague and attacked her; he was in “full steam” and in that same second, I jumped up and restrained the patient.