How Coaches Can Be a Source of Mental Health Support for Student-Athletes

- Share article

Youth sports coaches can be—and frequently are—strong role models and mentors for kids. But too often, they are ill-equipped to handle sensitive issues, including mental health challenges.

There’s a growing movement to change that, experts said during a panel discussion at the SXSW EDU conference here. After all, nearly 30 million U.S. children and teens participate in some form of organized sports.

“Coaches are really well-suited to be able to check in with young people on a regular basis,” said Hannah Olson, the director of the Center for Leadership in Athletics at the University of Washington. "[They] see them every day at practice. [They can] understand what their baseline is, what they look like on an average day, and be able to know when something’s going on, for better or for worse.”

And students look up to their coaches, making these educators prime candidates to offer mental health support and resources.

“Sport is a context that matters really, really deeply to a lot of young people,” Olson said. “Perhaps what happens to them out on the field or on the court is more important to them than what happens in their math classroom, for example.”

Yet coaches rarely get training on how to meet the social-emotional or mental health needs of their student athletes.

A 2022 national survey , conducted by The Ohio State University, the Aspen Institute’s Project Play Initiative, the Susan Crown Exchange, and Nike, found that coaches are most confident at promoting good sportsmanship, making athletes feel welcome on the team, teaching basic sporting techniques and skills, and reporting child abuse and neglect.

The coaches were least confident when it came to helping athletes navigate the pressures of social media, linking athletes to mental health resources, referring athletes to supports for unmet basic needs, like food assistance, and identifying off-the-field stressors among student athletes.

Just under half of coaches said they were “moderately” or “extremely” prepared to address mental health concerns. Forty-two percent felt prepared to work with student-athletes who have experienced trauma, and 35 percent felt prepared to work with athletes who have eating disorders.

Coaches want more training

Two-thirds of the coaches surveyed said they’re interested in having more training on mental health. Only half of school-based coaches are teachers or educators—the rest are parents or other community members.

“Coaches are really undertrained, as a general rule—most coaches receive no training, and the training that they do receive is often not around positive youth development, social and emotional learning, [or] supporting positive mental health of athletes,” said Megan Bartlett, the founder of the national nonprofit Center for Healing and Justice Through Sport.

Said Doug Ute, the executive director of the Ohio High School Athletic Association and a former longtime superintendent: “We’re just so doggone happy that somebody wants to coach 8th grade track, we throw them the keys, and we move on.”

Last year, Ohio became the first state in the country to require that all high school coaches receive mental health training. The Ohio High School Athletic Association is working with policymakers to incorporate that training into already existing professional development, so coaches don’t feel overwhelmed, Ute said.

Ute, a former basketball coach, said he’s excited about what the new law will mean for coaches and students in the state.

“All of my PD as a coach was focused on X’s and O’s—not one bit of wellness for the athletes,” he said. “I wish I could go back and be that young 22-year-old again that was in a classroom and coaching, and focus a little bit more on that wellness of my athletes.”

After all, he added, “coaching is an extension of the school day.”

A similar bill in Maryland passed the state House but later died in committee last year.

And in Washington state, the Center for Leadership in Athletics is working with the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association to pass a policy that would require baseline training for coaches that includes foundational skills in youth development, Olson said.

What coaches can do to support students’ mental health

The head coach of the Boston Celtics tries to spend one minute with every player on the team at every practice to check in and see how they’re doing, said Vince Minjares, the project manager of the Sports & Society Program at the Aspen Institute, a Washington-based policy nonprofit. That kind of small, extra step can go a long way, he said.

After all, coaches don’t always know what happened during the school day or at home, Ute said. Getting to know students off the field can help bridge that gap: “Do you know your student-athletes beyond what their skill level is at dribbling or shooting a basketball?”

Coaches can also teach students how to regulate their emotions, Bartlett said. Sports can be a good stress-reliever, but most students need to first learn how to identify when they’re feeling out of control and how to reset themselves, she said.

“We have to understand that kids cannot leave it at the door,” Bartlett said. "[They] cannot turn [their] brain off and say, all of a sudden, ‘I’m just fine for basketball practice or to jump in the pool,’ unless we teach them skills that help them regulate those emotions, help them transition from where they’re at to the environment they need to be in.”

And coaches need to learn how to regulate their own emotions, too, she said. Otherwise, coaches’ actions can be harmful to students’ mental health, she and Olson said.

“Just try to imagine another setting where we can put a grown adult in front of a young person and let them scream in their face, and it’s fine for the outcome so they can win a game,” Olson said. “We don’t let that happen anywhere else, but that has been the norm in sports for a really long time—tolerating toxic behaviors, abusive behaviors.”

Bartlett said she hopes there’s a broader narrative shift about youth mental health that focuses more on prevention than intervention. Sports and coaches should be at the center of that conversation, she said.

“The sport environment is uniquely suited to help young people heal from overwhelming stress or trauma—and there are too many young people who are experiencing overwhelming stress and trauma,” she said. “And even if you aren’t, these practices, the idea of focusing on safe environments where young people can show up as themselves, focusing on the value of physical activity and moving your body, focusing on the experience of being able to be stressed and come back to a baseline ... those are the things that make us mentally well.”

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 22 October 2018

A qualitative investigation of the role of sport coaches in designing and delivering a complex community sport intervention for increasing physical activity and improving health

- Louise Mansfield ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4332-4366 1 ,

- Tess Kay 1 ,

- Nana Anokye 2 &

- Julia Fox-Rushby 3

BMC Public Health volume 18 , Article number: 1196 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

7252 Accesses

11 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Community sport can potentially help to increase levels of physical activity and improve public health. Sport coaches have a role to play in designing and implementing community sport for health. To equip the community sport workforce with the knowledge and skills to design and deliver sport and empower inactive participants to take part, this study delivered a bespoke training package on public health and recruiting inactive people to community sport for sport coaches. We examined the views of sport coach participants about the training and their role in designing and delivering a complex community sport intervention for increasing physical activity and improving health.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with paid full-time sport coaches ( n = 15) and community sport managers and commissioners ( n = 15) with expertise in sport coaching. Interviews were conducted by a skilled interviewer with in-depth understanding of community sport and sport coach training, transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis.

Three key themes were identified showing how the role of sport coaches can be maximised in designing and delivering community sport for physical activity and health outcomes, and in empowering participants to take part. The themes were: (1) training sport coaches in understanding public health, (2) public involvement in community sport for health, and (3) building collaborations between community sport and public health sectors.

Training for sport coaches is required to develop understandings of public health and skills in targeting, recruiting and retaining inactive people to community sport. Public involvement in designing community sport is significant in empowering inactive people to take part. Ongoing knowledge exchange activities between the community sport and public health sector are also required in ensuring community sport can increase physical activity and improve public health.

Peer Review reports

Regular physical activity is significant in the prevention and treatment of physical and mental health conditions including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, some cancers, anxiety and depression [ 1 ]. Worldwide, the prevalence of physical activity at recommended levels is low. Current estimates in the UK are that approximately 20 million adults (39%) are categorised as inactive because they fail to meet the recommended guidelines for physical activity of 150 min per week of moderate intensity physical activity and strength exercise on at least 2 days [ 2 ]. Increasing population levels of physical activity can potentially improve public health. In England, the Moving More, Living More cross Government group includes representation from national lead agencies, Sport England, the Department of Health and Public Health England and recognises the role that sport can play in helping people to become more active for improved health outcomes [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. This perspective reflects more recent debates about the potential of low intensity physical activity for improving health which challenge established physical activity for health guidelines emphasising moderate and vigorous intensity phyiscal activity [ 6 ].

Successive Sport England strategies have focused on developing sporting opportunites tailored to the needs of diverse communities of local users. With devolvement of public health priorities to local authorities in April 2013, there is a heightened significance of locally based initiatives and the role of complex community interventions for public health outcomes; those that involve several interlocking components important to successful delivery [ 7 , 8 ]. Community-centred interventions can have a positive impact on health behaviours [ 9 , 10 ]. Successful community-based health interventions are associated with extensive formative research, participatory strategies and a theoretical and practical focus on changing social norms [ 11 ].

Sport coaches have a vital role to play in changing social norms around sports through individual and community engagement and empowering or enabling participants to take part in physical activity [ 12 ]. Empowerment theory provides a useful theoretical approach for understanding the complexities of raising physical activity levels through community sport. At the community level, empowerment theory investigates people’s capacity to influence organisations and institutions which impact on their lives [ 13 , 14 ]. The theory addresses the processes by which personal and social factors of life enable and constrain behaviours, and this provides the theoretical basis of this study.

There are 1,109, 000 sport coaches in the UK primarily working in sports clubs or extra-curricular school-based programmes, with much of their expertise focused on beginners and learners and sport enthusiasts [ 15 ]. Sports coaches represent community assets in the development of sport for health programmes for inactive adults who may be apprehensive rather than enthusiastic about taking part in sport [ 12 ], yet little is known about the occupational drivers, priorities and requirements of this workforce. There is potential for them to be a resource for identifying and assessing inactive people and providing physical activity education, promotion and support in local public health environments; a role more commonly associated with routine care in GP surgeries and health centres [ 16 , 17 ]. The potential of sports clubs as a health promotion setting has been recognised [ 18 , 19 ]. Key issues have been identified in developing successful approaches to health promotion in sports clubs including the need for clear health focused strategies, adapting sports activity, ensuring a health promoting environment, enabling learning opportunities about sport for health and workforce training in public health [ 20 ]. Knowledge and skill development in the sport coach workforce is imperative to equip it to design, deliver and evaluate community sport opportunities for public health outcomes [ 21 ]. Most recent models for such workforce development advocate partnership approaches between sport and leisure providers, public health professionals and the participants for whom community sport programmes are designed and delivered [ 22 ]. The aim of this paper is to explore the role of sport coaches in designing and delivering a complex community sport intervention for increasing physical activity and improving health.

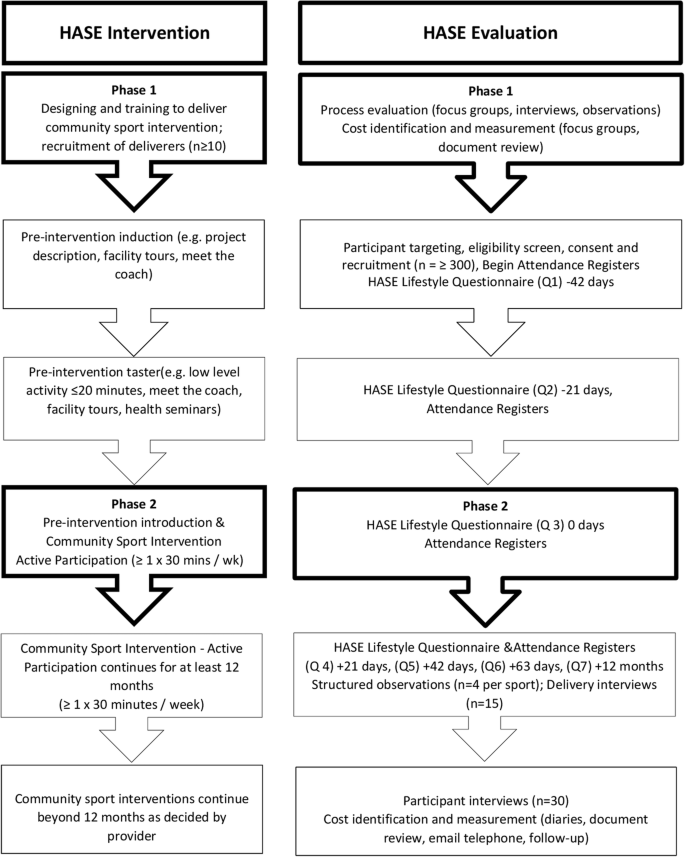

Background to the study – The health and sport engagement (HASE) project

Between March 2013 and July 2016, 32 sport coaches delivering and managing community sport in the London Borough of Hounslow were involved in a complex community sport intervention; the Health and Sport Engagement (HASE) project. The aim of the HASE project was to engage previously inactive people in sustained sporting activity for 1 × 30 min a week, examine the associated health and wellbeing outcomes of doing so, and produce information of value to those commissioning public health programmes that could potentially include sport. Full details of the HASE project are provided in the published protocol [ 23 ]. A summary of the HASE project intervention and evaluation phases is provided in Fig. 1 .

The Health and Sport Engagement (HASE) Study overview

Design and delivery of the HASE intervention involved a collaborative partnership between local community participants, sport coaches and community sport managers/ commissioners in the London Borough of Hounslow (LBH), and sport and public health researchers at Brunel University London. Coaches were key stakeholders in the project which employed a collaborative approach to stakeholder engagement, involving them in the initial project ideas development prior to the funding application, and in formative discussions about relevant training and the content and scheduling of training. Training served not only as a form of education and skill development but as a space for on-going involvement of coaches in the co-design [ 24 ] of the training programme, the precise nature of the sport activities and their delivery and evaluation approaches.

During a 12-month delivery phase, community sport coaches delivered 682 sport sessions to 550 people in the HASE project. Community sport coaches with expertise and experience in delivering and managing sport activities and with knowledge of diverse local communities were identified as central to the successful design and implementation of community sport for inactive people. A bespoke HASE training programme was included to identify existing expertise and additional skills and knowledge requirements of community sport coaches in designing and implementing community sport for health. The HASE training schedule for sport coaches consisted of two elements:

To develop understandings of public health for sport coaches, training included The Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) Level 2 Award in Understanding Health Improvement, and workshops on targeting, promoting and retaining inactive people to sport ( http://makesportfun.com/ ), and disability, inclusion and sport ( https://disabilitysportscoach.co.uk/training-workshops/ ).

To address the need for cross sector collaboration and partnership between local sport and public health groups, sports coaches and public health professionals attended a bespoke knowledge exchange workshop on getting to know and understand the roles and working practices of personnel in each sector ( http://makesportfun.com/ ).

Between March–September 2013, 32 community sport coaches were trained in the RSPH Level 2 Award in the first phase of the HASE project. Fifteen of those sport coaches were paid and full-time and they also engaged in training about targeting, recruiting and retaining inactive people in community sport and an on-line disability in sport course. Fourteen of those additionally attended knowledge exchange activities between sport coaches and public health professionals (1 coach was unavailable due to work commitments). Knowledge exchange activities included demonstrations of adapted sports activities, a ‘meet and greet’ event in which coaches and health professionals were paired to talk and exchange professional information, then paired with another expert at 5-min intervals, and a discussion forum about the strategy and mechanism of local authority public health referral scheme.

The HASE project included a mixed methods evaluation of the outcomes, processes and costs of the complex community sport intervention. Process evaluations are recommended in examining the efficacy of complex interventions and have value in multisite projects where the same interventions are tailored to the specific contexts and delivered and received in diverse ways [ 25 ]. Process evaluations using qualitative methods can complement research designs that assess effectiveness and efficiency quantitatively [ 26 ], by providing in-depth knowledge from those delivering and receiving the interventions. Evaluating the design, implementation, mechanisms of impact, and contextual factors that create different intervention effects can support the development of optimal complex community interventions and contribute to decision making about whether it is feasible to proceed to a larger scale trial [ 27 ]. This study presents findings from the interviews with sport coaches and community sport managers or commissioners with expertise in sport coaching which formed part of the process evaluation in the HASE project.

Data collection

Taking a pragmatic approach to evaluation to ensure timely, practice relevant yet rigorous research [ 28 ] the 15 sport coaches who had been trained in the RSPH Level 2 Award, attended the workshops and completed the on-line disability in sport course were invited for interview. All but one of those had also attended the knowledge exchange workshops with public health professionals. Fifteen community sport managers or commissioners with knowledge of sport coaching and involved in developing the HASE intervention and evaluation were also invited to interview. Thirty telephone interviews were conducted with paid full-time sport coaches ( n = 15) and community sport managers and commissioners ( n = 15) with expertise in sport coaching.

Semi structured interviews were conducted by one researcher (LM) for consistency of questioning. The aims of these interviews were twofold: (1) to examine the aspirations and logic underpinning design, delivery, promotion, and commissioning of sport for health projects, and (2) to examine the experiences and views of the HASE training. The interview guide can be found in Additional file 1 . The interview data helped to determine the role of the sports coach in designing and delivering a complex community sport intervention for increasing physical activity and improving health. In this paper direct quotes are included in the results and respondents referred to by gender, self-reported job and coaching role and years of experience (YE).

Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interview data were managed via NVivo 11 software and through the collation of tables and data matrices using Word 2010. The principles of thematic analysis were employed in this study. Thematic analysis allows the organisation, detailed description and scrutiny of patterns of meaning in qualitative data [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Analysis involved repeated reading, by two researchers (LM and TK), of interview transcripts, to determine the details of the data and to enable researchers to identify key themes and patterns in it. Themes were identified by theoretical approaches focused on our analytical interest in empowerment in community sport interventions, and by inductive (data-driven) approaches drawing directly from the data produced. Coding frameworks were devised by two researchers (LM and TK). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and the codes and themes verified by all researchers (LM, TK, NA, JF-R) in a process of identifying, refining and interpreting key themes [ 32 ]. Anonymised quotes from interviewees are provided as evidence form our study. Punctuation was added to unambiguous quotes and where necessary, words added in parentheses to clarify intended meaning.

Interviewees had been employed in the community sport sector for between 6 months and 25 years. Interviews lasted between 18 and 50 min and the mean interview length was 26 min. Three key themes were identified from the interview data that illustrate the significance and role of the sport coach in designing and delivering community sport for physical activity and health outcomes, and in empowering participants to take part: (1) training sport coaches in understanding public health, (2) public involvement in community sport for health, and (3) building collaborations between community sport and public health. We present the results in sections to reflect the identified themes although we are mindful that the themes overlap.

Training sport coaches in understanding public health

Phase 1 of the HASE project provided training for sport coaches and instructors to develop knowledge and understanding of public health and of targeting, recruiting and retaining inactive people to sport for health programmes. There was recognition amongst the HASE workforce of the potential for their work in community sport to support public health outcomes through the informal connections between health and their existing qualifications and experience:

we’ve always recognised that it’s (sport) physical activity and health going hand in hand…..Yes this is about sport…but… it’s about engagement, it’s about physical activity, it’s about meaningful activity for young people and adults to gain confidence and skills, but actually it’s linked into health and healthy lifestyles as well (M,Community Sport Manager and Sport Coach, 15YE).

The need for sports coaches to engage in training to develop their understanding of public health and their ability to deliver to health outcomes was also recognised. The training was delivered in two forms – an RSPH Level 2 award, and bespoke training workshops commissioned through the HASE project.

Royal Society for public health (RSPH) level 2 award in understanding health improvement

The RSPH level 2 Award provided HASE sports coaches with the time and space to think about the relationships between sport and health and consider the significance of public health for their work. Those who participated expressed great enthusiasm for the training and emphasised that it had provided them with new knowledge and approaches that were highly relevant to their role in enabling people to become more active. The training was very highly valued:

I’m really glad I took those courses…it changed how I did things…. especially the behaviour change parts …and the (health) things they encourage you to think about … with different groups… also the social and emotional aspect of that (physical activity and health)… it really helped …understand inactivity …and help people (M, Community Leader and Sport Coach, 5YE). It just gave me some space to think about health…and how what I do can link to public health issues (M, Community Sport Coach, 5YE).

A particularly important aspect of the delivery of the RSPH course was tailoring the information and subsequently the activities and their delivery to local population characteristics in Hounslow and to the requirements and priorities of the HASE workforce in supporting people to raise their physical activity levels:

the Hounslow portion of that training was amazing, that was brilliant, I really liked it. I thought that it was crazy that people that live in Chiswick lived four years, on average, four years longer than people that live you know in like other parts of Hounslow for example. I can now talk to kids about health ..through sport (M, Community Sport Coach, 4YE).

Bespoke training workshops: Targeting, recruiting and retaining inactive participants

The workshops focusing on targeting, recruiting and retaining inactive people to sport gave sport coaches the knowledge and time to effectively plan their programmes:

The workshops I thought were really good. I think when you’re actually discussing the practicalities, logistics, in reality how can we do this it’s definitely good to give you a chance to have discussions and actually properly sit down and plan. And I was able to go from one workshop, try something in the middle and then come back to the next one and talk about actually I did this and it worked. That sort of camaraderie in a way leaves you feeling motivated, ready to go. (F, Physical Activity Manager and Sport Coach Commissioner, 8YE).

The workshops also helped sports coaches develop knowledge about best practice in supporting and engaging inactive groups in community sport:

The qualification (RSPH) and those workshops are the right approach … they are about saying this is what we know now…this is the best way of doing it….it’s a forum where it brings people together where people meet on a course and then they’ve gone off and developed a programme together (M, Community Sport Commissioner, 15YE).

One of the key things was being in the mix with so many people from different sports... everyone had different stories to talk about, different experiences …knowledge …expertise to share (F, Community Coach Volunteer, 5YE).

Public involvement in community sport for health

Sport coaches identified the involvement of potential participants as important to the co-design and implementation of the community sports. Involving potential participants in designing their local sport offer was viewed as a way for sport coaches to identify both the physical activity and sporting needs of potential participants. It was also way for sport coaches to think about, understand and respond to practical barriers to participation but also the complex personal and social conditions, experiences and views that make taking part difficult; a key tenet of empowerment approaches:

outreach….you’ve got to invest some time in it…..speaking to a captive audience …encouraging them and actually I think there was a desire, they did want to be active but the barrier was the transport and their own physical ability. So knowing that ….and having that barrier taken away from them, it was then easy to attract them in (F, Community Sports Development Manager and Sport Coach, 20YE). you have to make a connection with them …..these people are unemployed, they’ve got housing problems, they’re not working, and also they’ve got addicted to something… you have to sit down with them….discuss with them. It’s someone they can listen to… (M, Community Leader and Sport Coach, 5YE).

Specifically, public involvement was identified as a way to enable sport coaches to recognise diversity and inequality and its impact on physical activity:

(Hounslow) is more diverse. Not everyone in a group goes to the local community centre for activity …not all Asian groups are the same. We need ways of understanding people a bit better …what are some of the conflicts they’re having…so we can offer solutions to (health) problems and not give them another thing they have to do (F, Community Sport Commissioner, 10YE)

Sport coaches supported the use of community focus groups, ‘meet the coach’ and taster sessions as effective forms of public involvement. These activities were important in facilitating active participation of potential participants and in helping community sport coachesto make the right decisions about the implementation of local community sport. Public involvement activities were viewed as a form of collective ownership of the community sport service:

in the past, it’s just been putting on activities and hoping that people turn up if it’s marketed. That’s not attracting the right (inactive) people. For our work …..to be embedded within the communities that you want to work within requires local people to get on board….we need to get out and meet them to reach the people that’s the hard to reach or most at need … we wanted to have more of a relationship with our participants…so we can decide and act together (F, Physical Activity Project Coordinator, 3YE).

For the sport coach workforce, working with participants was a form of community empowerment. It enabled potential participants to influence the development of community sport and physical activity programmes:

I don’t think there’s any point you just putting something on. Present it, get feedback, discuss it and make decisions together. if people are a bit more informed and actually really understand what the drive is behind it, then everything makes more sense you know… it empowers you a little bit to think…and understand…to take ownership of a project (F, School-Community PE Specialist, 25YE).

Building collaborations between community sport and public health

Collaborative working between researchers, local and national sport policy makers, community sport coaches, managers and commissioners, public health professionals and participants defined the design, delivery and evaluation of the HASE project overall. The London Borough of Hounslow had an established network of community sport and physical activity partners operating through a CSPAN (Community Sport and Physical Activity Network). This forum was important to the inception and implementation of the project:

I think the [HASE] approach suits Hounslow really well …six years ago, we were still working very much in siloes and everybody was doing their own thing. Since then we’ve had everybody working together on the community sports, this connectivity network …all our projects are about partnership work across the borough, across the range of services, and across a range of boroughs, that’s linking in and sharing expertise and resources (F, Community Sport Development Lead, 20YE).

Two aspects of collaborative working were identified by the interviewees: knowledge exchange, and partnership approaches.

Knowledge exchange

The opportunity for knowledge exchange between different sport coaches and public health professionals was central to successful partnerships and for sustained delivery of community sport for health outcomes:

The knowledge exchange was powerful for me because I could see there’s a lot of opportunity …for communities to bind themselves together by way of sport, and to give those people a healthy option in order to live a better life (M, Community Sport Coach, 10YE). that knowledge exchange workshop…it was the first time I came into contact with some of those people who did those various jobs. There was the health trainers…I didn’t even know they existed to be honest! So it was interesting to find out how they work with their clients and maybe if they’re looking to refer them to like organisations such as ourselves where they can do regular exercise then there’s maybe a partnership (M, Community Sport Coach, 5YE).

The challenges of promoting public health through community sport, and developing more systematic, collaborative and larger scale working relationships between community sport and local health agencies, were recognised:

Physical activity is a core area in public health. Sport - I think it’s very relevant …for me it’s a new role and the problem is that sports clubs can sometimes be a bit cliquey… you’ve got those added complexities…confidence…what to wear…not knowing anyone. But, having said that, you know, then sports clubs can have quite a nice social side, which gives another added dimension to people and makes them feel part of a community and to have something additional that they can engage with in a really positive way, but it’s just how that happens and how you get to that point (F, Community Sport Commissioner, 10YE).

However, the significance of HASE planning and training activities in enabling partnership working between public health professionals and community sport coaches for health outcomes dominated the views:

I was hesitant but I did learn a lot …I am going to work together with the Hounslow Homes project now (F, Community sport coach, 20YE). I’ve now got a relationship with Integrated Neurological Services and we’re working on developing and delivering a programme (F, Physical Activity Manager and Sport Coach Commissioner, 8YE). My coaches are understanding more about the health agenda and people within health are understanding more about the positivity of doing sport and physical activity as well…local connections worked really well (M, Senior Community Sport Manager and Sport Coach, 15YE).

Partnerships, pathways for recruitment and promoting sport for health

Partnership working in public health commonly involves strategies for bringing people together and enabling engagement, making pathways for recruitment and issues of promotion and communication key. A core ambition for commissioners, managers and sport coaches in this study was for the development of a referral system for community sport activities, based on existing referral approaches in public health that could develop a partnership between public health and community sport in working with inactive communities:

I think that going forward we’re trying to engage a large amount of inactive people, what would work well is referrals into a programme. Self-referrals or GPs or health trainers are a key to referring to community sport. And then also there’s that knowledge exchange from sports clubs, coaching professionals and volunteers, to understand how health professionals do their work ….and help them signpost to us (M, Director, Community Health Organisation, 8YE). I feel that there needs to be an agreed way forward in the whole Borough… for a referral process…recognising and going out to physical activity deliverers so if in public health you’re sitting there doing your individual target sheet with your client, they want to get fit, they have mobility issues, they’re over 60 or whatever, refer them to me, contact me (F, Physical Activity Project Coordinator, 3YE).

Sport coaches and those involved in commissioning community sport identified established public health strategies, theoretical approaches and pathways to recruitment as relevant to the work of sport coaches:

my starting point..for community sport …would be around NICE guidance that clearly states there’s an evidenced way of doing things…quite complex and requires a certain skill base ….but actually when people have done that work it’s a lot easier and we need sport delivery teams to know about giving advice and motivating people take part (F, Community Sport Commissioner, and Sports Coach 10YE). have sport coaches understand behaviour change …advising and motivating …is quite important (M, Commissioner, 15YE).

A more formalised role for sport coaches in engaging and supporting inactive people to become active through community sport was identified:

you could see a role for a physical activity activator or sport champion …giving support to inactive people to get active … understanding everything, .helping decisions, signposting to relevant services (M, Director, Community Health Organisation, 8YE).

The common theme in discussions about recruiting and signposting to community sport was the idea of moving beyond traditional health promotion messages associated with exercise prescription to a focus on knowledge and understanding about the role of sport for health and enabling people to take part:

(we have to) avoid very old health messages about exercise as something else they have to do. I think better ways of messaging are with some of the behaviour change ways …but through understanding people so it’s more for them (F, Community Sport Commissioner, 10YE)

Principal findings

This study recognised that engaging inactive people in sport lies outside sports coaches previous experience and aimed to equip them for this new role. All interviewees agreed that formal training via the RSPH Level 2 Award was a key ingredient for increasing sports coaches’ knowledge and understanding about public health. Bespoke workshops on targeting, recruiting and retaining inactive people to community sport allowed coaches to develop their skills and knowledge and maximise the potential for raising physical activity levels in their work. Public involvement was also unanimously viewed as essential to better understanding of the barriers and facilitators to sport for diverse community groups. Moreover, it was identified as a way to understand better and attempt to resolve the complex personal and social experiences that mitigate against taking part. Engaging potential participants in the design of community sports projects was found to be important in appropriately tailoring community sport programmes. Public involvement allowed a focus on collective ownership of the content and delivery of community sport and was considered central to successful participant engagement. On-going opportunities for knowledge exchange between sport coaches and public health professionals was recognised as a pathway to sharing best practice in identifying, supporting and empowering inactive people to become more active. A more formal role for sport coaches in delivering community sport to increase levels of physical activity was articulated as important by our interviewees.

Overall, the need for partnerships between local public health and community sport sectors was advocated for successful service delivery of community sport for inactive people. Yet, the significant challenges of promoting public health through community sport were identified. Overcoming the negative perceptions of sport and addressing the problems of ensuring more systematic, collaborative and larger scale working relationships between community sport and public health organisations were identified.

Contribution to knowledge

The findings support the work that has identified sports coaches as potential community assets, helping local communities to address public health concerns around raising levels of physical activity [ 12 , 21 ]. In addition, the study adds to and develops further the conclusions of other studies which contend that sports coaches have a wider role than the teaching of sport skills to play in individual and community development of life skills [ 33 ], positive social behaviours [ 34 ], and supporting mental health [ 35 ]. While others have identified that sports coaches are not routinely trained in public health or the needs of inactive populations [ 21 ], this study shows that with the right training and partnership arrangements sports coaches have the potential to identify inactive people and engage and support them in tailored community sport programmes. They can, therefore, offer both a complementary and additional service in public health behaviour change broadly, one which is typically linked with the work of GPs or practice nurses [ 16 , 17 , 22 ]. The processes by which sports coaches in this study engaged and supported inactive people to take part in community sport reflects the significance of strategies reported in the wider literature which seek to develop understandings of complex and diverse personal and social experiences which make it difficult for people to participate including youth [ 36 ], age and ageing [ 37 ], disability [ 38 ], gender [ 39 ], sexual orientation [ 40 ], socio-economic status [ 41 ] and the environment [ 42 ] and crucially the intersections of such socio-cultural, environmental and individual issues. Pedagogical implications for coaches are revealed in this study. Supporting inactive people to become involved in community sport for health requires learning in practice and our findings indicate the salience of developing innovative health-related pedagogical skills and knowledge for the coaching workforce [ 43 ]. This also requires recognition of the complex reality of designing and delivering sport for inactive people and a more innovative approach to coaching; one that is not solely based on competencies but recognises the need to build, enhance and apply different skills and knowledge in reaching and engaging diverse groups of inactive people with a range of health and wellbeing needs in community sport [ 44 ]. This study illustrates the importance for researchers and practitioners, of developing theoretical and applied work that moves beyond established behaviour change approaches to physical activity to consider complex everyday relationships, and develop knowledge and understanding about the challenges of and best practice in empowering people to take part in community sport for health and wellbeing. It also illustrates the scope for drawing on work from the social sciences that provides deeper understandings of social diversity in sport and physical activity which can be applied in supporting those who find it most difficult to take part [ 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ]. These findings support those from studies that have argued for public involvement in community health projects to improve service quality, programme relevance, participant engagement and satisfaction, and health outcomes [ 49 ]. The present study also reinforces the potential in co-design approaches for ensuring that the needs of all stakeholders are addressed and that there is shared ownership and responsibility for project outcomes [ 50 , 51 ]. The findings support calls for workforce development, knowledge exchange and partnership approaches in the community sport sector to reflect public health concerns connected to raising physical activity levels [ 22 , 52 ]. It is emphasised that there remain challenges in overcoming negative perceptions of sport and in scaling up public health and community sport partnerships for population level change in physical activity.

Strengths and weaknesses

The study was part of a rigorous mixed methods study design for which there is a published protocol. The use of one interviewer provided some consistency in questioning and the sample included a diverse range of stakeholders centrally involved in community sport coaching or the management and commissioning of coaching. Interviews were conducted by the project lead who was involved in other aspects of the research providing some consistency and a systematic approach to data collection and analysis throughout the project.

The sample was self-selecting which can create some bias in the data. One coach did not attend the knowledge exchange workshop due to other work-related commitments and may have had an experience and views on that aspect of the training which could have affected the findings.

Implications for practice and research

Sport coaches have a role in designing and delivering complex community sport interventions for increasing physical activity and improving health. However, there is a need to understand how the knowledge and skill set of this workforce can be advanced for them to realise their potential as community resources in public health. This study has identified that it is possible to build capacity for delivering sport for health programmes by training sports coaches in public health, building locally specific knowledge about inactive communities through public involvement strategies, facilitating cross-sector knowledge exchange and encouraging partnership working between sport and public health sector experts. There is an increasing focus on community sport delivery for public health outcomes. Such delivery is complex and there is a need for research to focus on developing the evidence base on the processes involved in sport coach delivery and the impact of sport coaches on the successes, impacts and outcomes of interventions to support intervention design. It is equally important that findings of such research are disseminated in useful and useable ways, and in varied forms to different stakeholders and user groups so they can capitalise on and use the evidence in their policy and practice work.

Conclusions

Complex community sport interventions have the potential to engage inactive people to increase physical activity for health. Such interventions are likely to be delivered by sport coaches whose knowledge and expertise in public health and recruiting inactive people to sport is partial. This study has shown that with the right training, sport coaches can develop and apply their knowledge and understanding of public health and their skills in targeting, recruiting and retaining inactive people to community sport. The findings emphasise the importance of public involvement in supporting engagement of inactive people in community sport. In addition, the study has shown that through knowledge exchange between the community sport and public health sectors, there is potential for reciprocal partnership arrangements to develop that could further equip sport coaches with the knowledge and skills to design and implement community sport and potentially develop population level interventions for increasing physical activity, reducing inactivity and improving public health.

Abbreviations

Community Sport and Physical Activity Network

The Health and Sport Engagement Projects

London Borough of Hounslow

Royal Society for Public Health

Department of Health. Start active, stay active: a report on physical activity for health from the four home counties’ chief medical officers. London: Department of Health; 2011.

Google Scholar

British Heart Foundation (2017) Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behaviour Report. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/physical-inactivity-report-2017 . Available on line. Accessed 25th August 2018.

Sport England. Towards an active nation strategy 2016-2021. London: DCMS. p. 2016.

Department of Culture Media and Sport. Sporting Future: A new strategy for an active nation. London: Crown Copyright; 2015.

Sport England. The active lives survey survey. https://www.sportengland.org/research/about-our-research/active-lives-survey . (Accessed 8 Jul 2016).

Smith L, Ekelund U, Hamer M. The potential yield of non-exercise physical activity energy expenditure in public health. Sports Med. 2015;45(4):449–52.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, Emery J, Farmer A, Griffiths F, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. Br Med J. 2007;334(7591):455.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Medical Research Council. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. London: Medical Research Council; 2008.

O'Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, McDaid G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, Matosevic T, Harden A, Thomas J. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Res. 2013;1(4).

Article Google Scholar

South J. A guide to community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing. PHE/NHSE London: Crown Copyright; 2015.

Merzel C, D'afflitti J. Reconsidering community-based health promotion: promise, performance, and potential. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):557–74.

Griffiths M, Armour K. Volunteer sports coaches as community assets? A realist review of the research evidence. Int J Sport Pol Pol. 2014;6(3):307–26.

Lord J, Hutchison P. The process of empowerment: implications for theory and practice. Can J CommunMent Health. 1993;12:5–22.

Fawcett SB, Paine-Andrews A, Francisco VT, et al. Using empowerment theory in collaborative partnerships for community health and development. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:677–97.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Sports Coach UK. Sports Coachingin the UK III; a statistical analysis of coaching and coaches in the UK. Leeds: Sports Coach UK; 2011.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Physical activity: brief advice for adults in primary care. In: NICE Public Health Guid, vol. 44; 2013.

Beighton C, Victor C, Normansell R, Cook D, Kerry S, Iliffe S, Ussher M, Whincup P, Fox-Rushby J, Woodcock A, Harris T. “It’s not just about walking..... it’s the practice nurse that makes it work”: a qualitative exploration of the views of practice nurses delivering complex physical activity interventions in primary care. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1236.

Donaldson, A., & Finch, C. F. (2012). Sport as a setting for promoting health.

Kokko S, Green LW, Kannas L. A review of settings-based health promotion with applications to sports clubs. Health Promot Int. 2013;29(3):494–509.

Geidne S, Quennerstedt M, Eriksson C. The youth sports club as a health-promoting setting: an integrative review of research. Scandinavian J Public health. 2013;41(3):269–83.

Almand L, Almand M, Saunders L. Coaching sport for health: a review of literature. London: Sports Coach UK; 2013.

Sporta CG. Supporting positive health outcomes through leisure and culture trusts. Perspect Public Health. 2016;136(5):262.

Mansfield L, Anokye N, Fox-Rushby J, Kay T. The Health and Sport Engagement (HASE) Intervention and Evaluation Project: protocol for the design, outcome, process and economic evaluation of a complex community sport intervention to increase levels of physical activity. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e009276.

Sanders, E.B.N., Singh, S. and Braun, E., 2018. Co-designing with communities.

Oakley A, Strange V, Bonell C, et al. Process evaluation inrandomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ. 2006;332:413.

Wall M, Hayes R, Moore D, et al. Evaluation of community level interventions to address social and structural determinants of health: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:207.

Datta J, Pettigrew M. Challenges to evaluating complex interventions: a content analysis of published papers. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:568. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-568 .

Scott RE. 'Pragmatic Evaluation': a conceptual framework for designing a systematic approach to evaluation of eHealth interventions. Int J E-Health Med Comm. 2010;1(2):1–11.

CAS Google Scholar

Clarke V, Braun V. Teaching thematic analysis: overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist. 2013;26(2):120–3.

Miles MB, Huberman MA. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. London: Sage; 1994.

Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2014;9.

Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res. 2001;1(3):385–405.

Super S, Verkooijen K, Koelen M. The role of community sports coaches in creating optimal social conditions for life skill development and transferability–a salutogenic perspective. Sport Educ Soc. 2018;23(2):173–85.

Santos F, Corte-Real N, Regueiras L, Dias C, Fonseca A. Coaches' perceptions on the role played by football on positive development of underserved youth: what reality? Cuad Psicol Deporte. 2018;18(2):214–27.

Ferguson HL, Swann C, Liddle SK, Vella SA. Investigating youth sports Coaches' perceptions of their role in adolescent mental health. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2018:1–18.

Rees, R., Kavanagh, J., Harden, A., Shepherd, J., Brunton, G., Oliver, S. and Oakley, A., 2001. Young people and physical activity: a systematic review of research on barriers and facilitators.

Baert V, Gorus E, Mets T, Geerts C, Bautmans I. Motivators and barriers for physical activity in the oldest old: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):464–74.

Shields N, Synnot AJ, Barr M. Perceived barriers and facilitators to physical activity for children with disability: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(14):989–97.

Biddle SJ, Whitehead SH, O’Donovan TM, Nevill ME. Correlates of participation in physical activity for adolescent girls: a systematic review of recent literature. J Phys Act Health. 2005;2(4):423–34.

Mansfield, Kay, Meads & Caudwell, Rapid Topic Overview: Physical Activity Among LGB&T Communities in England, Brunel Centre for Sport, Health & Wellbeing, 2014.

Stalsberg R, Pedersen AV. Effects of socioeconomic status on the physical activity in adolescents: a systematic review of the evidence. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(3):368–83.

McCormack GR, Shiell A. In search of causality: a systematic review of the relationship between the built environment and physical activity among adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):125.

Armour K. What is ‘sport pedagogy’and why study it? In: Sport Pedagogy; 2013. p. 29–41. Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Morgan K, Jones RL, Gilbourne D, Llewellyn D. Innovative approaches in coach education pedagogy. Nuances. 2013;24(1):218–34.

Long, J., Hylton, K., Spracklen, K., Ratna, A. and Bailey, S., 2009. Systematic review of the literature on black and minority ethnic communities in sport and physical recreation.

Lawson HA. Empowering people, facilitating community development, and contributing to sustainable development: the social work of sport, exercise, and physical education programs. Sport Educ Soc. 2005;10(1):135–60.

Spaaij R, Oxford S, Jeanes R. Transforming communities through sport? Critical pedagogy and sport for development. Sport Educ Soc. 2016;21(4):570–87.

Phoenix C, Bell SL. Beyond “move more”: feeling the rhythms of physical activity in mid and later-life. Soc Sci Med. 2018.

Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C, Weaver T, Bhui K, Fulop N, Tyrer P. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ. 2002;325(7375):1263.

Bovaird T. Beyond engagement and participation: user and community coproduction of public services. Public Adm Rev. 2007;67(5):846–60.

Hampson M, Baeck P, Langford K. By us, for us: the power of Co-Design and Co-Delivery. In: People Powered Health. London: Nesta; 2013.

Mansfield L. Resourcefulness, reciprocity and reflexivity: the three Rs of partnership in sport for public health research. Int J Sport Policy Politics. 2016;8(4):713–29.

Download references

The study was funded through Sport England’s Get Healthy Get Active Award URN 2012021352.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Life Sciences, Brunel University London, Kingston Lane, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB8 3PH, UK

Louise Mansfield & Tess Kay

Department of Clinical Sciences, Brunel University London, Kingston Lane, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB8 3PH, UK

Nana Anokye

Department of Primary Care and Public Health Sciences, King’s College London, Addison House, Guy’s, London, SE1 1UL, UK

Julia Fox-Rushby

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LM, TK, AN, JF-R made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data in the Health and Sport Engagmeent Project. LM, TK, AN and JF-R have been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. LM, TK, AN and JF-R have given final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Louise Mansfield .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval for the interviews was granted through the ethics award for the HASE project overall. Participants received detailed written participant information and gave written consent to participate. Consent was clarified verbally at the start of the interviews. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time, without penalty and to their right to anonymity and confidentiality. This study was approved by Brunel University Research Ethics Committee, Division of Sport, Health and Exercise Sciences (reference RE33–12).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

LM and TK are members of Sport England’s Evidence Review Advisory Panel. LM is a member of UEFA’s Grow Project Advisory Panel. NA and JF-R have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Agenda of interview questions ( and prompts) . (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mansfield, L., Kay, T., Anokye, N. et al. A qualitative investigation of the role of sport coaches in designing and delivering a complex community sport intervention for increasing physical activity and improving health. BMC Public Health 18 , 1196 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6089-y

Download citation

Received : 14 July 2018

Accepted : 04 October 2018

Published : 22 October 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6089-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Community sport

- Complex community intervention

- Sport coaches

- Public health

- Physical activity

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Risk and Protective Factors for Bullying in Sport: A Scoping Review

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 28 March 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lisa Kalina 1 ,

- Brendan T. O’Keeffe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4590-3460 2 ,

- Siobhán O’Reilly 3 &

- Louis Moustakas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3388-4407 4

66 Accesses

10 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The aim of the current study was to examine risk and protective factors related to bullying in sport. Adopting the methodological approach outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1):19–32, 2005 ), 37 articles met the inclusion criteria. A consistent definition of bullying could not be identified in the publications examined, and several articles ( n = 8) did not explicitly define bullying. The most frequent risk factor identified was an individual’s social background ( n = 9). Negative influence of coaches ( n = 5), level of competition ( n = 5), lack of supportive club culture ( n = 5) and issues in locker rooms ( n = 4) were among the most commonly cited risk factors for bullying in sport settings. Preventative policies were cited as the most common method to reduce the incidence of bullying ( n = 13). Contextually tailored intervention programmes ( n = 5) were also noted as a key protective factor, particularly for marginalised groups, including athletes with disabilities or members of the LGBTQ+ community. The need for sport-specific bullying prevention education was highlighted by 10 of the articles reviewed. In summary, the current review accentuates the range of risk and protective factors associated with sport participation. Furthermore, the need for educational training programmes to support coaches in addressing and preventing bullying within sport settings is emphasised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Winning at all costs: a review of risk-taking behaviour and sporting injury from an occupational safety and health perspective

Yanbing Chen, Conor Buggy & Seamus Kelly

Psychological Safety for Mental Health in Elite Sport: A Theoretically Informed Model

Courtney C. Walton, Rosemary Purcell, … Simon M. Rice

How do representatives from sporting organisations understand primary prevention of violence against women?

Ruth Liston, Gemma Hamilton & Sarah McCook

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Bullying is a complex and multi-layered issue that crosses from childhood to adulthood and is a continuing challenge in education, workplace and recreation settings (Fisher & Dzikus, 2017 ). Although there remains considerable debate regarding the definition of the concept, Olweus’ ( 1993 ) definition has retained some support (Jewett et al., 2020 ). Olweus ( 1993 , p. 8) defines bullying as an ‘intentional, negative action which inflicts injury and discomfort on another’. According to Olweus ( 1993 ), bullying is characterised by an imbalance of power between victim and perpetrator as well as by repeated bullying behaviours. The phenomenon of bullying in education and workplace settings has received extensive scholarly attention (Campbell & Bauman, 2018 ; Jimerson et al., 2009 ; Zapf et al., 2020 ). However, research on bullying outside school and workplace settings is relatively scarce (Evans et al., 2016 ). One such context is sport settings, and researchers have suggested bullying in such contexts may present its own unique features (Kerr et al., 2016 ). Kerr et al. ( 2016 ) suggest that bullying can occur due to teasing behaviours carried out for ‘entertainment purposes’, which may not carry a clear intent to harm, such as ‘banter’ or ‘locker room talk’. Recent high-profile cases of bullying in elite sport (see CNN, 2022 , 2023 ) have demonstrated that, even at an elite level, sporting organisations are not prepared to cope with issues such as marginalisation and exclusion that may be considered both precursors and sources of bullying. Indeed, bullying on sports teams may have particular implications for participants, given the importance of interconnectedness and interdependence of team members for a sense of cohesion and performance outcomes (Kleinert et al., 2012 ). Bullying research and the widespread adoption of practical approaches are scarce (Newman et al., 2022 ). Fekkes et al. ( 2005 ) reported that almost one-third of bullying experiences occur beyond school and workplace settings, indicating a need to broaden the scope of research and consider bullying in recreation and sport contexts.

Sports, particularly team sports, often involve competition and aggressive interaction and some research has highlighted higher levels of bullying within the team sport context (MacPherson, 2018 ; Marracho et al., 2021 ; Vveinhardt & Fominiene, 2020 ). At times, in the heat of competition, it can be challenging for participants to distinguish between deliberately hurtful actions and those inherent to the competitive nature of the game (Nery et al., 2019 ). As a consequence, bullying in terms of hurtful behaviours, both physical and verbal, can end up becoming an accepted and expected norm that is intrinsic to particular sports, and such behaviour is often informed by coaches (Vveinhardt et al., 2019 ). Furthermore, the source of bullying behaviour is not always restricted to participants in an opposing team. Emerging evidence indicates that the source is often from participants on the same team or even a coach (Evans et al., 2016 ). As such, coaches in particular play a crucial role in reducing or addressing bullying. Sport coaches are not only expected to support sport development, but also to provide a fun, positive and safe team environment while also actively fostering personal (life skill) development (Čujko et al., 2020 ; Gilbert & Trudel, 2004 ). Nonetheless, despite the growing awareness of bullying in sport and recreation settings, there remains limited programmes for coaches aimed at heightening sensitivity about bullying, preventing and identifying bullying situations and intervening effectively (Shannon, 2013 ; Stefaniuk & Bridel, 2018 ).

The prevalence of bullying appears to differ significantly across countries (Modecki et al., 2014 ), and estimates regarding its prevalence vary greatly depending on the context and the measurement tool used to gather the data (Evans et al., 2016 ). For instance, data from the USA indicate that about one out of every four school children has experienced bullying (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022 ). In a European context, Craig et al. ( 2009 ) reported differences in prevalence ranged from lows of 8.6% and 4.8% in Sweden to highs of 45.2% and 35.8% in Lithuania, among boys and girls, respectively. However, the assessment of this phenomenon among participants in different contexts and countries, using measurement tools that lack validity and reliability, emphasises the need for caution when making such comparisons (Vveinhardt et al., 2019 ). As noted by Bachand ( 2017 ), many researchers have used one-item measures of bullying, which may be insufficient given the intricacy of bullying-related behaviours. Despite concerns regarding the accuracy of tools to measure prevalence, it is abundantly clear that bullying is commonplace in sporting contexts, with a range of adverse health and psychosocial consequences going far beyond the context within which the sport occurs (Shannon, 2013 ). Via a sample of 1440 Lithuanian sport participants between 16 and 29 years old, the prevalence of bullying within different types of sports was measured by Vveinhardt and Fominiene ( 2020 ) in individual sports (9.8%), combat sports (8.5%) and team sports (7.3%). In their analysis, athletes experienced most bullying actions in combat sports (20%) while almost half less in team sports (10.8%) as well as in individual sports (10.1%). Notwithstanding challenges with measurement and contextual factors, the disparity in rates between countries indicates that contrasting cultural and social norms, and varying approaches in the implementation of bullying-related policies or programmes, may significantly influence the prevalence of bullying behaviour (Fisher & Dzikus, 2017 ). For instance, higher conformity to hegemonic masculinity norms may enhance the perceived acceptability of bullying (Steinfeldt et al., 2012 ).

Little attention has been given to the social, environmental and situational factors in sport contexts that may influence bullying behaviour (Vveinhardt et al., 2019 ). Therefore, risk factors or protective factors associated with both the perpetrator and victim are not well established. Some authors, such as Shannon ( 2013 ), reported that the culture of a sport organisation, as exemplified through the values, attitudes, beliefs and practices of administrators and staff, might serve as an important buffer to bullying. Other studies likewise highlight the potential role of contextual factors or individual relationships (e.g. Evans et al., 2016 ; Newman et al., 2022 ). Beyond these first attempts, however, there still remains a need to more systematically identify risk and protective factors, which in turn can directly help tailor and inform the development of awareness or education programmes targeted at sport coaches.

As such, the following scoping review aimed to examine how bullying is defined and measured in sport-related literature and to establish commonalities in both risk and protective factors associated with bullying. This could serve to inform sporting organisations to foster more inclusive environments and limit the negative consequences of bullying. In addition, a specific focus of this review was to examine the role coaches play in preventing or facilitating bullying.

The following scoping review took place against the backdrop of the BEFORE project. A four-partner, pan-European action, this project aims to review current policies and practices to develop educational training programmes to support coaches in addressing and preventing bullying within sport settings, funded by Erasmus+ (2021-1-IE01-KA220-VET-000034749). To effectively grasp current understandings and experiences around bullying in sport, and develop evidence-based educational programmes, a scoping review was undertaken to map out crucial information related to the subject. Indeed, scoping reviews can be valuable in identifying evidence around a given topic, documenting trends and clarifying concepts (Munn et al., 2018 ).

For the following, we adopt the methodological approach outlined by Arksey and O’Malley ( 2005 ), which is a widely accepted approach for scoping reviews and has been adopted by numerous reviews in the areas of bullying and sport-related social issues more generally (e.g. Clarke et al., 2021 ; Quinlan et al., 2014 ). Our scoping review began in March 2022 and took approximately 11 months. The review followed six steps, namely, (1) identifying the research questions; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. A sixth step, consultation with relevant stakeholders, was also implemented to add rigour and validate findings. In the following sub-sections, we document each of these steps individually.

Identification of the Research Questions

In line with the educational objectives of the BEFORE project, the authors and project members developed a set of research questions to guide our search strategy. Following recommendations, we ensured that our questions were not so narrow as to limit the analytical process and broad enough to capture all relevant literature. As such, in accordance with the aims of our project, we developed three research questions to direct our review: (1) how is bullying defined in sport-related literature; (2) what risk or protective factors are identified concerning bullying and (3) what role do coaches play in preventing or facilitating bullying?

Determination of Relevant Studies

A search strategy was developed and reviewed by the authors and all project members, including during the project launch meeting in March 2022. As a result, we selected several multi-disciplinary and thematically relevant databases to conduct our search and agreed on relevant search terms and related inclusion criteria.

A final search string was chosen (TS = (“sport*” AND “bully*”)) to balance the extent and relevance of results as well as overall feasibility. Given the more niche nature of the topic, we opted for a simple combination of two broad search terms to obtain a wide range of potentially relevant results. Furthermore, as part of our research question concerned specifically the definition of bullying, we opted to exclude potentially connected terminology such as peer victimisation or harassment. As such, only the two mentioned terms have been included to ensure a feasible number of articles were retrieved from our search for review. Numerous databases, including the Web of Science Core Collection, KCI-Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE ® , Russian Science Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index, SportDISCUS, Sociology Source Ultimate and PsyIndex, were used. Via in-built online filters, searches were limited to peer-reviewed journal publications published in English between 2000 and 2022. All searches were conducted on April 12, 2022. Tables 1 and 2 present the search strategy and inclusion criteria, respectively.

Study Selection

Covidence software was used to manage and streamline the process of abstract and full-text screening. Covidence allows researchers to upload search results, automatically scans for duplicates and coordinates multi-user screening of articles, thus facilitating our work as a multi-national, decentralised research team. Two project members reviewed each abstract and subsequent full text independently. A unanimous decision was required for texts to progress to full-text screening and, later, to full-text inclusion. In situations of conflicting decisions, the authorship group met to discuss and resolve those conflicts. Two key factors drove full-text inclusion.

Firstly, texts were required to make explicit reference to the term bullying. Related concepts, such as violence, maltreatment or abuse, were excluded. Though admittedly connected, including these concepts would have inflated the review and included behaviours and perspectives that, arguably, go beyond what is typically associated with bullying. Secondly, only texts concerning the prevalence, experience or prevention of bullying in the club, community or extracurricular sport context were included. Though we recognise that bullying and sport frequently occur within educational contexts, most coaches targeted by the BEFORE project work within community or club contexts. Those contexts likely face different dynamics than formal educational settings (Kerr et al., 2016 ), and it was necessary for the project that those contexts be adequately and fully reflected in our results.

Charting the Data

The next stage of the process involved charting and data extraction from the included studies. Each project partner was responsible for charting a segment of the included studies, and the authorship group reviewed the final data table. We used Google Sheets and charted bibliographic, methodological and bullying-specific information for the included studies. Regarding bibliographic and methodological information, we collated titles, author(s), year, journal name, country of study, study design, sample descriptions, data collection methods and theories employed. As it relates to bullying, we documented the definition employed within the article, the setting in which the bullying took place, the bullying relationship (i.e. athlete-athlete, coach-athlete) and the risk and protective factors documented in the study.

Collating and Reporting Results

Both frequency analysis and deductive coding were used to collate and report the results. The variables extracted for the frequency analysis included publication year, data origin (country), journal, methodology, study population and sport. Deductive coding allowed us to identify and summarise the relationships and protective and risk factors highlighted by the texts. Based on the coding results, we then conducted a frequency analysis to document the occurrence of these relationships and factors.

Consultation

Though consultation is presented here as the final step, consultation took place throughout this research. The entire project consortium, which includes an anti-bullying NGO, a pan-European organisation and two universities, was engaged in the review’s design, implementation and analysis. Multiple members from each project partner contributed to designing, reviewing and implementing the proposed search strategy and inclusion criteria. Following the collation and writing of the results, these partners reviewed the extracted data and critically appraised the overall analysis in this text.

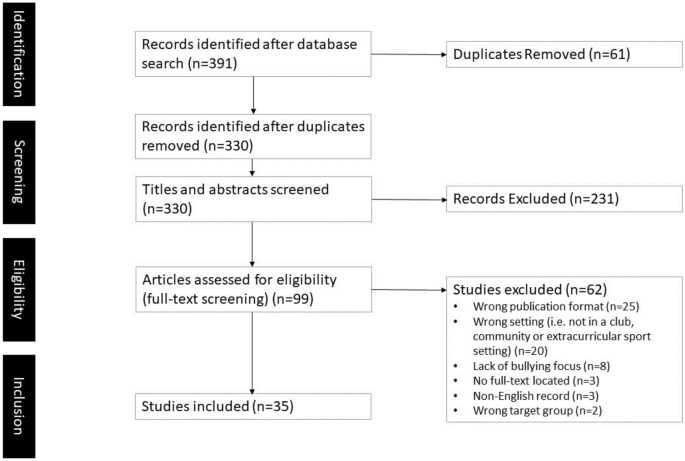

In total, 391 studies were identified, 61 duplicates were removed, and 330 studies were screened. After screening, 231 studies were excluded, with 99 studies being assessed for eligibility. Of these 99, 62 studies were excluded for the reasons noted in Fig. 1 , including wrong publication format ( n = 25), wrong setting ( n = 20) and lack of bullying focus ( n = 8). After our inclusion criteria were applied, 37 articles examining bullying in sport met all criteria for inclusion in this study. An overview of the retained articles is provided in Table 3 .

Flow chart for bullying in sport scoping review

Publication Year

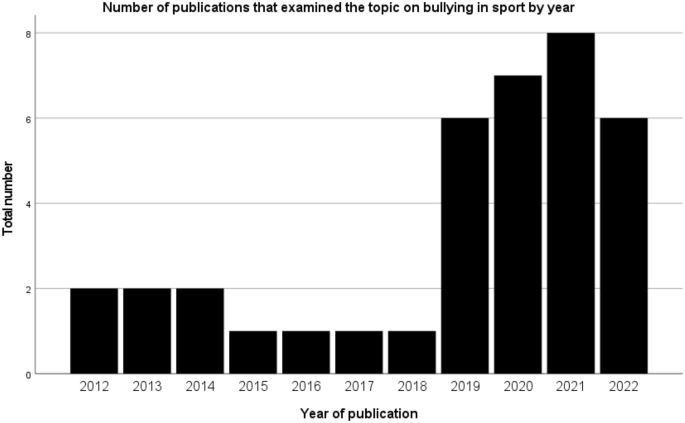

Though our search parameters extended back to 2000, no texts were included before 2012. As evidenced in Fig. 2 , articles on bullying in sports have increased since 2019, with 26 out of 37 publications published from 2019 to 2022.

Number of publications that examined bullying in sport, by year

In total, 31 different journals were included in the scoping review. Three publications were included in the journals Frontiers in Psychology , and a further two publications each were included in the journals Motricidade , International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology and Journal of Human Sport & Exercise as well as the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health .

Research Locations

Research data comes mostly ( n = 35) from countries in the so-called West or ‘Global North’, characterised as Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand. The other two studies come from Iran and Japan. Lithuania appears more frequently than the other Western countries ( n = 8), followed by the USA ( n = 6), Canada, Portugal, Spain and the UK ( n = 4).

In terms of the different sports analysed, most studies focused on multiple sports ( n = 21), including team sports (football/soccer, basketball, rugby) as well as individual sports (swimming, acrobatics, gymnastics or badminton). A total of 11 articles analysed one particular sport, with football/soccer being the most frequent ( n = 6).

Definition of Bullying in Sport