An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire: Development and Validation of a Questionnaire to Evaluate Students’ Stressors Related to the Coronavirus Pandemic Lockdown

Maria clelia zurlo.

1 Dynamic Psychology Laboratory, Department of Political Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

Maria Francesca Cattaneo Della Volta

2 Department of Humanities, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

Federica Vallone

Associated data.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Clinical observations suggest that during times of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown university students exhibit stress-related responses to fear of contagion and to limitations of personal and relational life. The study aims to describe the development and validation of the 7-item COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ), a measurement tool to assess COVID-19-related sources of stress among university students. The CSSQ was developed and validated with 514 Italian university students. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted with one split-half sub-sample to investigate the underlining dimensional structure, suggesting a three-component solution, which was confirmed by the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with the second one split-half sub-sample (CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.06). The CSSQ three subscales measure COVID-19 students’ stressors related to (1) Relationships and Academic Life (i.e., relationships with relatives, colleagues, professors, and academic studying); (2) Isolation (i.e., social isolation and couple’s relationship, intimacy and sexual life); (3) Fear of Contagion. A Global Stress score was also provided. The questionnaire revealed a satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.71; McDonald’s omega = 0.71). Evidence was also provided for convergent and discriminant validity. The study provided a brief, valid and reliable measure to assess perceived stress to be used for understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown among university students and for developing tailored interventions fostering their wellbeing.

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been defined as an extreme health, economic and social emergency and it was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 2020 ( World Health Organization, 2020 ), resulting in lockdown and life restrictions in Italy as worldwide in the attempt to prevent and slow the spread of the virus.

Comparable previous emergencies, such as the SARS outbreak, were strongly demonstrated as spreading stress and inducing psychological disease in terms of depression, anxiety but also panic attacks, and even psychotic symptoms, delirium, and increased rates of suicidal ( Xiang et al., 2020 ). These results have been recently confirmed with respect to the current COVID-19 pandemic ( Brooks et al., 2020 ; Zandifar and Badrfam, 2020 ), particularly in terms of high levels of psychological distress ( Qiu et al., 2020 ), depression ( Wang et al., 2020 ), anxiety ( Horesh and Brown, 2020 ; Lima et al., 2020 ; Rajkumar, 2020 ), fear and panic behaviors ( Shigemura et al., 2020 ).

In this perspective, a review conducted by Brooks et al. (2020) on the psychological impact of quarantine periods and outbreak confinements in last decades (e.g., the SARS outbreak, the 2009 and 2010 H1N1 influenza pandemic) identified specific common experiences such as fear of contagion, fear and frustration related to inadequate supplies (e.g., basic necessities and medical supplies), sense of confusion due to inadequate quality of information from public health authorities, sense of isolation, frustration and boredom due to loss of usual routine and to reduced social contacts ( Brooks et al., 2020 ).

Furthermore, the COVID-19-related containment measures imposed massive work and school closures, segregation and social distancing, deeply impacting on personal and relational life and exposing people to experience uncertainty, feelings of isolation, and sense of “losses” in terms of motivation, meaning, and self-worth ( Williams et al., 2020 ).

In view of that, research made several efforts to better explore the psychological impact of the ongoing Coronavirus global outbreak, developing and validating specific tools.

In particular, the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S; Ahorsu et al., 2020 ; Soraci et al., 2020 ) and the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS; Lee, 2020a ) were developed to assess, respectively, perceived COVID-related fear and anxiety. Moreover, the COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index (CPDI; Costantini and Mazzotti, 2020 ; Qiu et al., 2020 ) was developed to assess the frequency of anxiety, depression, specific phobias, cognitive change, avoidance and compulsive behavior, physical symptoms and loss of social functioning.

Finally, the COVID-19 Stress Scales (CSS; Taylor et al., 2020 ) was developed to measure the psychological impact of COVID-19 in terms of danger and contamination fears, fears about economic consequences, xenophobia, compulsive checking and reassurance seeking, and traumatic stress symptoms.

Overall, the instruments reported above specifically addressed the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak in terms of psychological outcomes, without addressing and identifying specific sources of stress related to relational and daily life changes induced by the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic-related experiences induced not only fears of contagion and social isolation but also significant modifications in several aspects of daily routine, mainly influencing (hindering or intensifying) all relationships, such as those with relatives, with the partner, with friends, with colleagues. Consequently, it emerged the need to develop instruments able to address not only the potential effects of isolation and fear of contagion but also of modifications of all significant relationships in daily life, so considering all potentially perceived sources of stress featuring the experience of pandemic lockdown.

Furthermore, in line with the transactional perspective ( Lazarus and Folkman, 1984 ), stress is considered a dynamic relational process, which depends on the constant interplay between individual factors (e.g., age, gender) and situational factors, so requiring to take into account specificities of target populations when defining tools to evaluate perceived sources of pressure.

From this perspective, the academic context was deeply affected by the lockdown restrictions worldwide. Indeed, due to the massive closure of colleges and universities ( United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2020 ), all the scheduled activities and events were postponed/annulled, campuses and students’ accommodations were forced to evacuations, all the formal and informal interactions were shifted to online platforms, leading to a substantial change in students’ customary life.

Different studies exploring factors associated to COVID-19 outbreak among university students highlighted high levels of anxiety and worries about academic delays and influence of the epidemic on daily life, due to the disruption in students’ daily routine, in terms of activities, objectives and social relationships ( Cao et al., 2020 ; Chen et al., 2020 ; Lee, 2020b ; Sahu, 2020 ). Indeed, the quarantine hindered the possibility to experience the university life, impacting on academic studying (i.e., uncertainties related to annulment/delays of activities, difficulties in employment of online platforms for the distance learning), but also impairing the possibility to benefit from the relationships that may represent anchor in students’ life, such as those with peers, colleagues, and professors ( Lee, 2020b ; Sahu, 2020 ). In addition, also considering the increasingly key role played by romantic relationships in the young population ( Anniko et al., 2019 ), research also outlined the potential changes in couple’ relationship, intimacy, and sexual life due to the COVID-19 pandemic ( Li et al., 2020 ; Rosenberg et al., 2020 ).

Moreover, whether, on the one hand, the abovementioned relationships with partner, friends, peers, colleagues, and professors were subject to a radical reduction and standstill, on the one other hand, in most of the cases, relationships with relatives were deeply intensified. Indeed, the majority of students were forced to return back home, also resulting from the campus dormitory evacuations, inducing an increased exclusivity of interaction with relatives, potentially exacerbating frustration and conflicts. This particularly when considering students living in already disadvantaged conditions and/or suffering from abusive home experiences ( Lee, 2020b ).

Overall, whether it’s clear that university students’ life was subject to broad modifications, up to date, there are no specific tools to understand, comprehensively identify and assess specific sources of stress featuring university students’ COVID-19-related experiences. This, however, could help in early recognize those students at higher risk for developing a significant psychological disease related to the pandemic lockdown, and, accordingly, provide timely and tailored interventions fostering their wellbeing.

Responding to this need, the present study aimed at proposing and validating a newly developed measurement tool to specifically assess sources of stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown among university students, namely the COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ).

Seven potential sources of stress have been hypothesized and operationalized. These sources have been defined as connected not only to fear of contagion and to experience of isolation but also to the potential abovementioned changes in students’ daily life and routine. In particular, it was hypothesized that induced changes in academic studying and relationships with friends, partner, university colleagues, professors and relatives could constitute significant perceived COVID-19 pandemic lockdown-related sources of stress among university students.

Hypotheses and research questions to rigorously check the validity and reliability of the COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ) are listed in Table 1 .

Research questions and hypotheses of the validation study.

Materials and Methods

Participants and sampling.

Online survey data were collected from 15 April to 15 May 2020 with students from the University of Naples Federico II. This period fully corresponded to the pandemic lockdown due to COVID-19 in Italy, and students were experiencing the consequences of university closures, with massive social restrictions. The participants were recruited through Microsoft Teams. Students were contacted and given all the information about the study, and they were asked their participation on a voluntary basis. All the participants were fully informed about the aims of the study and about the confidentiality of the data, and they were also assured that the data would be used only for the purpose of the research and refusal to participate would not affect their current and future course of study in any way. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Psychological Research of the University where the study took place (IRB:12/2020). Research was performed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from each student prior to participating in the study. Every precaution was taken to protect the privacy of research subjects and the confidentiality of their personal information. Overall, 514 university students voluntarily enrolled in the study and completed online Microsoft Teams forms.

The questionnaire included a section dealing with background information (i.e., Gender, Age, Degree Program, Year of study), the proposed 7-item COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire, and a measure for psychophysical health conditions.

COVID-19 Related Sources of Stress Among University Students

The COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ) was specifically developed to assess university students’ perceived stress during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. It consists of 7 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from zero (“Not at all stressful”) to four (“Extremely stressful”). For the purpose of instrument design, perceived stress was operationalized based on transactional models of stress ( Lazarus and Folkman, 1984 ). Each item was developed to cover different domains that could have been subject to variations due to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, and, therefore, that may be potentially perceived as sources of stress (i.e., risk of contagion; social isolation; relationship with relatives; relationship with colleagues; relationship with professors; academic studying; couple’s relationship, intimacy and sexual life). The scale provides a Global Stress score ranging from 0 to 28.

Psychophysical Health Conditions

The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1994 ; Prunas et al., 2010 ) was used to assess self-reported psychophysical health conditions. The scale comprises 90 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from zero (“Not at all”) to four (“Extremely”) and divided into nine subscales: Anxiety (10 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.84), Depression (13 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.87), Somatization (12 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.83), Interpersonal Sensitivity (9 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.83), Hostility (6 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.80), Obsessive-Compulsive (10 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.82), Phobic Anxiety (7 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.68), Psychoticism (10 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.77), and Paranoid Ideation (6 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.76). Participants were asked to indicate how much these problems have affected them during the past 4 weeks (e.g., Anxiety subscale: “Tense or keyed up”, “Fearful”; Depression subscale: “Hopeless about future”, “No interest in things”). The scale also provides a global index, namely the Global Severity Index (GSI). GSI is the sum of all responses divided by 90, and it indicates both the number of symptoms and the intensity of the disease (GSI Cronbach’s α = 0.97).

Data Analysis

For the validity testing of the CSSQ we used the European Federation of Psychologists’ Association’s (EFPA) standards and guidelines ( Evers et al., 2013 ), which describe the standard method for validity testing by the following levels of evidence: 1) Construct validity; 2) Criterion validity: (a) Post-dictive or retrospective validity; (b) Convergent validity; (c) Discriminant validity. In the present study, validity evidence was examined in relation to Construct validity, Convergent validity, and Discriminant validity.

Evidence Based on Construct Validity

Evidence based on construct validity was examined to answer research questions 1 and 2 and to test hypotheses 1 and 2 ( Table 1 ). To examine the validity of the COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ) we used a two-step analytic strategy. First, the entire study sample ( N = 514) was split using a computer-generated random seed. According to the rules of thumb for sample size in factor analysis, the sample size for each sub-sample ( n = 257) was considered adequate to explore the structure of the 7-item CSSQ ( Comrey and Lee, 1992 ; Costello and Osborne, 2005 ; DeVellis, 2017 ). Construct validity was analyzed using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA).

EFA was performed in the first split-half (Sub-sample A, n = 257) to explore the latent dimensional structure (R1 and R2) and to identify significant and coherent factors (H1). Principal Components Analysis (PCA) with oblique promax rotation was used. The choice of non-orthogonal rotation was justified on the hypothesis that the factors would be correlated. The factorability of the correlation matrix of the scale was evaluated by Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Barlett test of sphericity. Criteria for extraction and interpretation of factors were as follows: eigenvalues > 1.0, Cattell’s scree test and inspection of scree plot, communality ≥ 0.30 for each item and factor loading > 0.32 for each item loading on each factor ( Costello and Osborne, 2005 ).

CFA was performed in the second split-half sub-sample (Sub-sample B, n = 257) to determine the goodness-of-fit of the extracted factor model (H2). Standard goodness-of-fit indices were selected a priori to assess the measurement models: χ 2 non-significant ( p > 0.05), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > 0.95), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < 0.08) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.95) ( Hu and Bentler, 1998 ).

Evidence Based on Convergent Validity

Evidence based on convergent validity was explored to test hypotheses 3 and 4 ( Table 1 ). Convergent validity was tested, first, by calculating standardized factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) of factors (H3). If the standardized factor loadings of a questionnaire are > 0.5 and statistically significant, and the values of CR and AVE of each factor are higher than 0.7 and 0.5, respectively, the questionnaire is considered as having a satisfactory convergent validity ( Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ; Hair et al., 2010 ). Moreover, convergent validity was assessed by correlational analyses (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) between the scales scores of the newly developed COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire and the standardized scales scores of the SCL-90-R (nine subscales and Global Severity Index) (H4). The effects size were interpreted following Cohen’s thresholds ( r < 0.30 represents a weak or small correlation; 0.30 < r < 0.50 represents a moderate or medium correlation; r > 0.50 represents a strong or large correlation) ( Cohen, 1988 ).

Evidence Based on Discriminant Validity

Evidence based on discriminant validity was explored to test hypotheses 5 and 6 ( Table 1 ). Discriminant validity was evaluated by comparing the square root of the average variance extracted (SQRT AVE) with the correlations between latent constructs (H5). When the SQRT AVE is above the correlations among factors, a questionnaire is considered as having an acceptable discriminant validity ( Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ). Furthermore, discriminant validity was also tested basing on the correlations between the CSSQ subscales and the Global Stress scores using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (H6).

Evidence Based on Internal Consistency

Evidence based on internal consistency was explored to test hypothesis 7 ( Table 1 ). Item means, standard deviations, and mean inter-item correlation (between 0.15 and 0.50) were evaluated ( Clark and Watson, 1995 ). Moreover, for the reliability test, Cronbach’s Alpha ( Cronbach, 1951 ) and McDonald’s Omega ( McDonald, 1999 ) were used to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire, considering α ≥ 0.70 ( Santos, 1999 ) and ω ≥ 0.70 ( McDonald, 1999 ) as indices of satisfactory internal consistency reliability (H7).

Finally, means, standard deviations, and ranges of the newly developed COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ) scales were calculated.

Characteristics of Participants

Characteristics of the total sample ( N = 514) as well as of each sub-sample (A and B) are shown in Table 2 . The total sample consisted of 372 women and 142 men, with a combined mean age of 19.92 ( SD = 1.50) years. The sample was composed of students enrolled in Philosophy ( n = 10, 1.9%), Modern Languages and Literature ( n = 44, 8.6%) and Psychology ( n = 460, 89.5%) degree programs; the majority of them were 1st year students (1st year n = 400, 77.8%; 2nd year n = 46, 8.9%; 3rd year n = 68, 13.3%).

Characteristics of study participants.

Construct Validity

Construct validity (research question 1) was examined by conducting EFA and CFA.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using Principal Components Analysis (PCA) with oblique promax rotation was carried out to investigate the underlining dimensional structure of the CSSQ. The assessment of factorability showed that the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure was 0.73 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ 2 = 332.26, df = 21, p < 0.001) indicating that the data were adequate for the factor analysis, supporting hypothesis 1. The examination of the scree plot produced a departure from linearity corresponding to a three-component result; the scree-test also confirmed that our data should be analyzed for three components, responding to research question two. The first three eigenvalues were 2.61, 1.20, and 1.00. The three-component solution explained a variance of 67.09% from a total of 7 items.

The first component (4 items, explained variance = 37.23%) was loaded by items referred to perceived stress related to relationships with relatives, relationships with colleagues, relationships with professors, and academic studying. We labeled this scale Relationships and Academic Life.

The second component (2 items, explained variance = 17.20%) was loaded by items referred to perceived stress related to social isolation and changes in couples’ relationship, intimacy and sexual life due to the social isolation. We labeled this scale Isolation.

The third component (1 item, explained variance = 12.66%) was loaded by a single item referred to perceived stress related to the risk of infection, hence it was labeled as Fear of Contagion ( Table 3 ).

COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ) exploratory factor analysis on first random split-half sample ( n = 257).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory Factors Analysis (CFA) was run to test hypothesis 2. The results supported the PCA findings ( Figure 1 ) by demonstrating that the three-factors model (χ 2 = 4.52, p = 0.79), comprising all the 7 items proposed, yielded good fit for all of indices (χ 2 /df ratio = 0.56; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.06).

Path diagram and estimates for the three-factor COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire on second random split-half sample ( n = 257).

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Concerning Convergent validity, the standardized factor loadings of CSSQ items were all > 0.5 (see Figure 1 ) and statistically significant ( p < 0.001). Moreover, the CR values were all > 0.7 (i.e., Relationships and Academic Life CR = 0.924; Isolation CR = 0.809; Fear of Contagion CR = 0.769). The values of AVE of all factors were > 0.5 (i.e., Relationships and Academic Life AVE = 0.637; Isolation AVE = 0.549; Fear of Contagion AVE = 0.649). Therefore, the standardized factor loadings, CR and AVE of factors were united to suggest that the CSSQ had strong convergent validity, confirming hypothesis 3.

Moreover, correlations with measures of psychophysical disease (SCL-90-R subscales and GSI) were carried out to further test convergent validity, showing that COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire scales and Global Stress scores revealed moderate to strong correlations with the SCL-90-R scales scores in the expected directions, and confirming hypothesis 4 ( Table 4 ).

Correlations of the COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ) scales with SCL-90-R scales.

Concerning Discriminant validity, the square root of AVE values were compared with the correlations among factors. All the square root of AVE values (i.e., Relationships and Academic Life, SQRT AVE = 0.798; Isolation SQRT AVE = 0.741; Fear of Contagion SQRT AVE = 0.805) were above the correlation values (i.e., correlation between Relationships and Academic Life and Isolation, r = 0.645; correlation between Relationships and Academic Life and Fear of Contagion, r = 0.621; correlation between Isolation and Fear of Contagion, r = 0.660; see Figure 1 ), indicating suitable discriminant validity, and supporting hypothesis 5.

Furthermore, still concerning discriminant validity, intercorrelations between the three COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire scales and the Global Stress scores were also calculated. Intercorrelations ranged from 0.30 to 0.42, showing medium levels of correlation, while correlations of all COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire scales with Global Stress scores were high in size and significant, indicating that the questionnaire assessed different but related dimensions, and confirming hypothesis 6 ( Table 5 ).

Intercorrelations between the COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ) scales.

Item Analysis and Reliability

Mean scores for the single items varied from a maximum score of 2.01 (Item 2: “How do you perceive the condition of social isolation imposed during this period of COVID-19 pandemic?”) to a minimum of 0.44 (Item 4: “How do you perceive the relationships with your university colleagues during this period of COVID-19 pandemic?”). SDs for the single items varied from 1.36 (Item 7: “How do you perceive the changes in your sexual life due to the social isolation during this period of COVID-19 pandemic?”) to 0.75 (Item 4: “How do you perceive the relationships with your university colleagues during this period of COVID-19 pandemic?”). The mean inter-item correlation was 0.26, therefore it was satisfactory. Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale was 0.71, while McDonald’s omega coefficient was 0.71, confirming that the CSSQ had satisfactory internal consistency (hypothesis 7).

All the items of the CSSQ were presented in Table 6 .

The COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire.

Table 7 displays items, means, standard deviations, and ranges of the CSSQ scales (Relationships and Academic Life, Isolation, Fear of Contagion) and the total score (Global Stress). Considering that high levels of COVID-19-related stress can be indicated by scores that are 1 SD above the mean (e.g., the 84th percentile) and low levels of stress can be indicated by scores that are 1 SD below the mean (e.g., the 16th percentile) of the distribution of the CSSQ scores, we can affirm that scores of 6 or below indicate low levels of perceived COVID-19-related Global stress, scores of 7–15 indicate average levels of perceived COVID-19-related Global stress, and scores of 16 or more indicate high levels of perceived COVID-19-related Global stress among university students.

Items, mean, SD and range scores of the COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire scales.

The aim of the present study was to develop, validate and evaluate the psychometric properties of the 7-item COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ), a brief measure to assess sources of stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown among university students. Indeed, addressing specific sources of stress tailored to target populations foster efficacy in preventive efforts and interventions ( Zurlo et al., 2013 , 2017 ; Anniko et al., 2019 ).

Accordingly, responding to the widespread need for developing specific tools to understand the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic among students ( Cao et al., 2020 ; Lee, 2020b ; Sahu, 2020 ), it was hoped this instrument could foster a timely identification of those students at higher risk for developing a significant disease related to the ongoing unique situation, and to deliver evidence-based and tailored interventions to promote their adjustment and wellbeing.

Findings highlighted that the proposed CSSQ possessed adequate factor validity, tapping three meaningful factors.

The first factor, labeled Relationships and Academic Life, comprised four items covering perceived stress related to relationships with relatives, relationships with colleagues, relationships with professors, and academic studying. Indeed, considering that students’ daily routine have been subject to specific changes ( Cao et al., 2020 ; Chen et al., 2020 ; Lee, 2020b ), this first factor fostered a greater understanding of the dimensions characterizing these modifications among university students in terms of relationships and academic life.

From this perspective, the relationships with relatives should be carefully focused, considering the forced full-time cohabitation, with almost exclusive sharing time and spaces throughout all days. This also as a consequence of the closures of the campus and students accommodations, which forced several students to return back home, but also considering the great number of students already living with their parents, however under completely changed conditions.

In the same direction, since restrictions drastically impaired the possibilities to benefit from living the university life, university students may report growing disease connected to changes in relationships with colleagues and professors (that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, are only allowed through online platforms), but also increased suffering related to the academic studying (e.g., fear of delays, difficulties in finding appropriate spaces to concentrate) ( Cao et al., 2020 ; Lee, 2020b ; Sahu, 2020 ).

The second factor, labeled Isolation, comprised two items exploring perceived stress related to social isolation and changes in sexual life due to the containment measures. From this perspective, in line with research emphasizing the strong weight of containment measures such as quarantine and social distancing on individuals’ psychological health and wellbeing ( Brooks et al., 2020 ; Horesh and Brown, 2020 ; Lee, 2020a ; Williams et al., 2020 ), the second factor also captured the perceived disease and sense of loneliness derived from living this condition, often far from the loved ones ( Sahu, 2020 ; Zhai and Du, 2020 ).

From this perspective, considering the specificity of the target population, it’s not surprising that the confinement in itself and sexual life belonged to the same factor. Indeed, since students were more likely to still live with their families or they returned back home due to the pandemic, it’s more probable that their couple’ relationship, intimacy and sexual life were subject to significant restrictions due to the lockdown. However, these findings may be also due to the specific European context, considering that the average age of young people leaving the parental house is 25.9 ( Eurostat, 2020 ), while in several other countries students use to leave home around 18 years for starting the college ( Aassve et al., 2002 ; Crocetti and Meeus, 2014 ).

The third factor, labeled Fear of Contagion, comprised one item assessing perceived stress related to the risk of infection. The relevance of the latter dimension is, indeed, in line with previous studies on the key role played by the fear to be infected, the fear for others (e.g., relatives, friends) to become ill, as well as the fear to be a source of contagion for the others ( Ahorsu et al., 2020 ; Brooks et al., 2020 ; Taylor et al., 2020 ).

Concerning convergent validity, the standardized factor loadings, and the values of AVE and CR were well above the threshold suggested by Hair et al. (2010) , indicating that the variances were more explained by each factor and all of the items of each factor were consistent for measuring the same latent construct.

Furthermore, data revealed significant associations of all CSSQ scales scores with all the SCL-90-R standardized scales scores as well as with the Global Severity Index. This revealed how the specific sources of stress we have identified, covering changes in Relationships and Academic Life, perceived Isolation and Fear of Contagion, could have significant negative effects on perceived psychophysical health conditions among students. These results suggested the meaningfulness to adopt the proposed instrument also to foster the development of early interventions supporting students’ adjustment and promoting their psychophysical health during and after the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

Concerning discriminant validity, the square root of AVE values were greater than the correlations coefficients between the factors, indicating that the three factors could extract more variance than the sharing among factors, so revealing a satisfactory discriminant validity. Moreover, intercorrelations between COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire scales (moderate in size) and correlations between the three scales and the Global Stress score (high in size) confirmed that the CSSQ assessed different but connected dimensions, so giving further support about the validity of the proposed tool to evaluate both perceived Global Stress and different sources of stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, both perceived levels of Global Stress and specific stressors should be carefully considered when defining interventions fostering students’ wellbeing during the current COVID-19 crisis.

Finally, the evaluation of mean inter-item correlation, Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega confirmed that the CSSQ had satisfactory internal consistency.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire is a 7-item multidimensional scale with satisfactory psychometric properties. Moreover, it is a good instrument to be used in assessing and allaying perceived COVID-19-related stress among university students.

Implications for Clinical Practice

The study sought to address the growing concerns arising from the challenges that students around the world are facing due to the COVID-19 pandemic and from its potential negative effects on their psychophysical health conditions, by providing a brief, valid and meaningful tool, namely the COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ).

The CSSQ presented here is a brief multidimensional tool, conceived to be helpfully used by members from different areas within universities (e.g., human resources, health units, student affairs) to promote a deeper understanding of the nature of COVID-19-related stressors perceived by students, in order to define tailored policies and support interventions.

In line with this, the CSSQ could be useful to early identify those students in need of psychological support. Indeed, due to the perceived risk of contagion, the consequent modifications of all significant relationships in daily life may induce, among university students, loss of contact with formal and informal support networks and growing risk of isolation. Therefore, it becomes pivotal to make all the possible efforts to assure careful monitoring of their perceived levels of stress and psychological wellbeing.

Finally, the adoption of the CSSQ in the clinical practice can significantly help social and health practitioners, serving as a monitoring and evaluation tool to define more tailored evidence-based counseling interventions. Indeed, since tapping different stressors that could have been experienced due to the COVID-19 outbreak (i.e., stressors related to Relationships and Academic Life, Isolation, and Fear of Contagion), the adoption of this tool can help to underline those areas requiring more attention within counseling interventions and to assess the effectiveness of the interventions by evaluating potential changes over time.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite these strengthens, some limitations need to be underlined. Firstly, the administering of the questionnaire was online, potentially limiting the enrollment in the study of those without Internet access. However, since the target population of Italian university students (taking into account both the age and the provision of distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic), we consider this limitation could have influenced our results to a little extent. Secondly, the participant pool comprised a self-selected sample of students enrolled only in one university (i.e., students enrolled in Philosophy, Modern Languages and Literature, and Psychology degree courses) with a majority being female (and therefore, tests for gender differences were not possible). Further investigation on bigger and more representative samples is needed to confirm the results provided by the present study (e.g., a nationally representative sample with more male participants). Thirdly, the study relies on participants’ self-reports, and, therefore, findings could be affected by the risk of social desirability bias. Future research could, hence, include a broader range of sources of data. Furthermore, future studies could also consider the meaningfulness to adopt newly developed COVID-19-related instruments (e.g., FCV-19S) to test concurrent validity. Indeed, at the time of study design and data collection, the Italian versions of these specific measurement tools were not available yet. Another limitation is the lack of available data for a more robust examination of reliability beyond internal consistency, such as test-retest. Consequently, future studies could be designed with the aim to also conduct test-retest analysis. Finally, cultural and social variables may have potentially influenced the construct of the questionnaire as well as it’s convergent and discriminant validity. Consequently, further applications of this instrument in other countries are needed to allow gaining further information about sources of stress influencing students’ wellbeing according to different countries worldwide.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provided researchers and practitioners with a brief, easily administered, valid and reliable measure to assess perceived stress among university students, so supporting efforts to understand the impact of this unique global crisis and develop tailored interventions fostering students’ wellbeing.

Data Availability Statement

Ethics statement.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical Committee of Psychological Research of the University of Naples Federico II. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MCZ: study conception and design, interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, critical revision. MFCDV: analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of manuscript. FV: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- Aassve A., Arpino B., Billari F. C. (2002). Age norms on leaving home: multilevel evidence from the European Social Survey. Environ. Plan A 45 383–401. 10.1068/a4563 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ahorsu D. K., Lin C. Y., Imani V., Saffari M., Griffiths M. D., Pakpour A. H. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8 [Epub ahead of print]. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anniko M. K., Boersma K., Tillfors M. (2019). Sources of stress and worry in the development of stress-related mental health problems: a longitudinal investigation from early-to mid-adolescence. Anxiety Stress Coping 32 155–167. 10.1080/10615806.2018.1549657 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brooks S. K., Webster R. K., Smith L. E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395 912–920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cao W., Fang Z., Hou G., Han M., Xu X., Dong J., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 287 : 112934 . 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen B., Sun J., Feng Y. (2020). How have COVID-19 isolation policies affected young people’s mental health? - Evidence from Chinese college students. Front. Psychol. 11 : 1529 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01529 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark L. A., Watson D. (1995). Constructing Validity: basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol. Assess. 7 309–319. 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences , 2nd Edn Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Comrey A. L., Lee H. B. (1992). A First Course in Factor Analysis , 2nd Edn Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Costantini A., Mazzotti E. (2020). Italian validation of CoViD-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index and preliminary data in a sample of general population. Riv. Psichiatr. 55 145–151. 10.1708/3382.33570 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Costello A. B., Osborne J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 10 1–9. 10.7275/jyj1-4868 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crocetti E., Meeus W. (2014). Family comes first!” Relationships with family and friends in Italian emerging adults. J. Adolesc. 37 1463–1473. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.012 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cronbach L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16 297–334. 10.1007/BF02310555 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Derogatis L. R. (1994). SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems. [ Google Scholar ]

- DeVellis R. F. (2017). Scale Development: Theory and Applications , 4th Edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eurostat (2020). Estimated Average Age of Young People Leaving the Parental Household by Sex. Available online at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=yth_demo_030&lang=en (accessed September 1, 2020). [ Google Scholar ]

- Evers A., Muñiz J., Hagemeister C., Høstmaelingen A., Lindley P., Sjöberg A., et al. (2013). Assessing the quality of tests: revision of the EFPA review model. Psicothema 25 283–291. 10.7334/psicothema2013.97 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fornell C., Larcker D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18 39–50. 10.2307/3151312 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hair J. F., Black W. C., Babin B. J., Anderson R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [ Google Scholar ]

- Horesh D., Brown A. D. (2020). Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: a call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychol. Trauma 12 331–335. 10.1037/tra0000592 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hu L., Bentler P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 3 424–453. 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lazarus R. S., Folkman S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York, NY: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee J. (2020b). Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 4 : 421 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee S. A. (2020a). Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: a brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud. 44 393–401. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li W., Li G., Xin C., Wang Y., Yang S. (2020). Changes in sexual behaviors of young women and men during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: a convenience sample from the epidemic area. J. Sex Med. 17 1225–1228. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.04.380 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lima C. K. T., Carvalho P. M. M., Lima I. A. A. S., Nunes J. V. A. O., Saraiva J. S., de Souza R. I., et al. (2020). The emotional impact of Coronavirus 2019- nCoV (new coronavirus disease). Psychiatry Res. 287 112915 . 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112915 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McDonald R. P. (1999). Test Theory: A Unified Treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Prunas A., Sarno I., Preti E., Madeddu F. (2010). SCL-90-R. Symptom Checklist 90-R. Florence: Giunti. [ Google Scholar ]

- Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Xu Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatr. 33 : e100213 . 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rajkumar R. P. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatr. 52 : 102066 . 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosenberg M., Luetke M., Hensel D., Kianersi S., Herbenick D. (2020). Depression and loneliness during COVID-19 restrictions in the United States, and their associations with frequency of social and sexual connections. medRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.05.18.20101840 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sahu P. (2020). Closure of Universities Due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic Staff. Cureus 12 : e7541 . 10.7759/cureus.7541 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Santos J. R. A. (1999). Cronbach’s alpha: a tool for assessing the reliability of scales. J. Ext. 37 1–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shigemura J., Ursano R. J., Morganstein J. C., Kurosawa M., Benedek D. M. (2020). Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 74 281–282. 10.1111/pcn.12988 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Soraci P., Ferrari A., Abbiati F. A., Del Fante E., De Pace R., Urso A., et al. (2020). Validation and psychometric evaluation of the Italian version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 10.1007/s11469-020-00277-1 [Epub ahead of print]. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Taylor S., Landry C., Paluszek M., Fergus T. A., McKay D., Asmundson G. J. (2020). Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. J. Anxiety Disord. 72 : 102232 . 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2020). Education: From Disruption to Recovery. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed September 1, 2020). [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. (2020). Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 323 1061–1069. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams S. N., Armitage C. J., Tampe T., Dienes K. (2020). Public perceptions and experiences of social distancing and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a UK-based focus group study. medRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.04.10.20061267 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization (2020). WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 -11 March 2020. Available online at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020 (accessed September 1, 2020). [ Google Scholar ]

- Xiang Y. T., Yang Y., Li W., Zhang L., Zhang Q., Cheung T., et al. (2020). Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 7 228–229. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zandifar A., Badrfam R. (2020). Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51 : 101990 . 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101990 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhai Y., Du X. (2020). Mental health care for international Chinese students affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 7 : e22 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30089-4 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zurlo M. C., Cattaneo Della, Volta M. F., Vallone F. (2017). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Fertility Problem Inventory–Short Form. Health Psychol. Open 4 : 2055102917738657 . 10.1177/2055102917738657 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zurlo M. C., Pes D., Capasso R. (2013). Teacher stress questionnaire: validity and reliability study in Italy. Psychol. Rep. 113 490–517. 10.2466/03.16.PR0.113x23z9 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

How is COVID-19 affecting student learning?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, initial findings from fall 2020, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld senior research scientist - nwea @megankuhfeld jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea @jsoland beth tarasawa , bt beth tarasawa executive vice president of research - nwea @bethtarasawa angela johnson , aj angela johnson research scientist - nwea erik ruzek , and er erik ruzek research assistant professor, curry school of education - university of virginia karyn lewis karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea @karynlew.

December 3, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced uncertainty into major aspects of national and global society, including for schools. For example, there is uncertainty about how school closures last spring impacted student achievement, as well as how the rapid conversion of most instruction to an online platform this academic year will continue to affect achievement. Without data on how the virus impacts student learning, making informed decisions about whether and when to return to in-person instruction remains difficult. Even now, education leaders must grapple with seemingly impossible choices that balance health risks associated with in-person learning against the educational needs of children, which may be better served when kids are in their physical schools.

Amidst all this uncertainty, there is growing consensus that school closures in spring 2020 likely had negative effects on student learning. For example, in an earlier post for this blog , we presented our research forecasting the possible impact of school closures on achievement. Based on historical learning trends and prior research on how out-of-school-time affects learning, we estimated that students would potentially begin fall 2020 with roughly 70% of the learning gains in reading relative to a typical school year. In mathematics, students were predicted to show even smaller learning gains from the previous year, returning with less than 50% of typical gains. While these and other similar forecasts presented a grim portrait of the challenges facing students and educators this fall, they were nonetheless projections. The question remained: What would learning trends in actual data from the 2020-21 school year really look like?

With fall 2020 data now in hand , we can move beyond forecasting and begin to describe what did happen. While the closures last spring left most schools without assessment data from that time, thousands of schools began testing this fall, making it possible to compare learning gains in a typical, pre-COVID-19 year to those same gains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using data from nearly 4.4 million students in grades 3-8 who took MAP ® Growth™ reading and math assessments in fall 2020, we examined two primary research questions:

- How did students perform in fall 2020 relative to a typical school year (specifically, fall 2019)?

- Have students made learning gains since schools physically closed in March 2020?

To answer these questions, we compared students’ academic achievement and growth during the COVID-19 pandemic to the achievement and growth patterns observed in 2019. We report student achievement as a percentile rank, which is a normative measure of a student’s achievement in a given grade/subject relative to the MAP Growth national norms (reflecting pre-COVID-19 achievement levels).

To make sure the students who took the tests before and after COVID-19 school closures were demographically similar, all analyses were limited to a sample of 8,000 schools that tested students in both fall 2019 and fall 2020. Compared to all public schools in the nation, schools in the sample had slightly larger total enrollment, a lower percentage of low-income students, and a higher percentage of white students. Since our sample includes both in-person and remote testers in fall 2020, we conducted an initial comparability study of remote and in-person testing in fall 2020. We found consistent psychometric characteristics and trends in test scores for remote and in-person tests for students in grades 3-8, but caution that remote testing conditions may be qualitatively different for K-2 students. For more details on the sample and methodology, please see the technical report accompanying this study.

In some cases, our results tell a more optimistic story than what we feared. In others, the results are as deeply concerning as we expected based on our projections.

Question 1: How did students perform in fall 2020 relative to a typical school year?

When comparing students’ median percentile rank for fall 2020 to those for fall 2019, there is good news to share: Students in grades 3-8 performed similarly in reading to same-grade students in fall 2019. While the reason for the stability of these achievement results cannot be easily pinned down, possible explanations are that students read more on their own, and parents are better equipped to support learning in reading compared to other subjects that require more formal instruction.

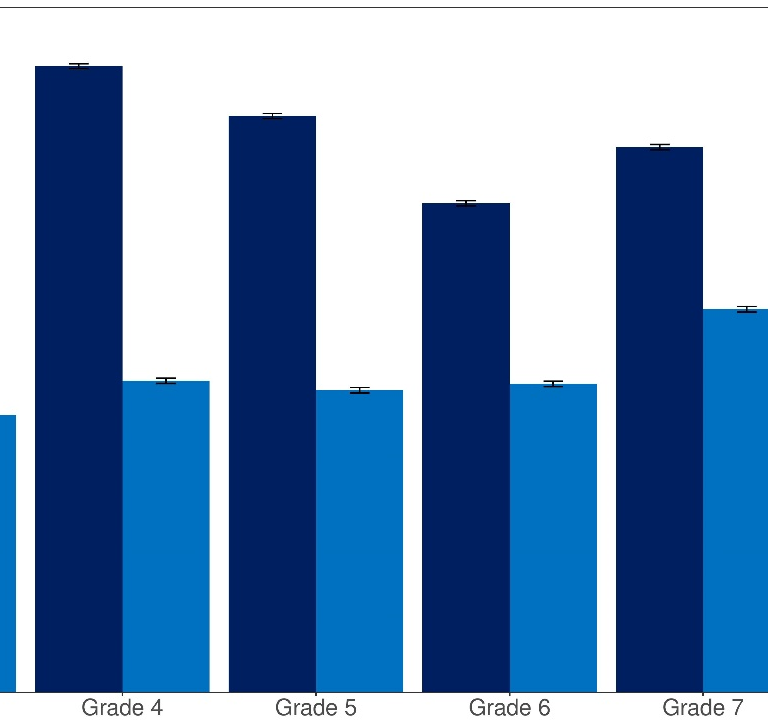

The news in math, however, is more worrying. The figure below shows the median percentile rank in math by grade level in fall 2019 and fall 2020. As the figure indicates, the math achievement of students in 2020 was about 5 to 10 percentile points lower compared to same-grade students the prior year.

Figure 1: MAP Growth Percentiles in Math by Grade Level in Fall 2019 and Fall 2020

Source: Author calculations with MAP Growth data. Notes: Each bar represents the median percentile rank in a given grade/term.

Question 2: Have students made learning gains since schools physically closed, and how do these gains compare to gains in a more typical year?

To answer this question, we examined learning gains/losses between winter 2020 (January through early March) and fall 2020 relative to those same gains in a pre-COVID-19 period (between winter 2019 and fall 2019). We did not examine spring-to-fall changes because so few students tested in spring 2020 (after the pandemic began). In almost all grades, the majority of students made some learning gains in both reading and math since the COVID-19 pandemic started, though gains were smaller in math in 2020 relative to the gains students in the same grades made in the winter 2019-fall 2019 period.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of change in reading scores by grade for the winter 2020 to fall 2020 period (light blue) as compared to same-grade students in the pre-pandemic span of winter 2019 to fall 2019 (dark blue). The 2019 and 2020 distributions largely overlapped, suggesting similar amounts of within-student change from one grade to the next.

Figure 2: Distribution of Within-student Change from Winter 2019-Fall 2019 vs Winter 2020-Fall 2020 in Reading

Source: Author calculations with MAP Growth data. Notes: The dashed line represents zero growth (e.g., winter and fall test scores were equivalent). A positive value indicates that a student scored higher in the fall than their prior winter score; a negative value indicates a student scored lower in the fall than their prior winter score.

Meanwhile, Figure 3 shows the distribution of change for students in different grade levels for the winter 2020 to fall 2020 period in math. In contrast to reading, these results show a downward shift: A smaller proportion of students demonstrated positive math growth in the 2020 period than in the 2019 period for all grades. For example, 79% of students switching from 3 rd to 4 th grade made academic gains between winter 2019 and fall 2019, relative to 57% of students in the same grade range in 2020.

Figure 3: Distribution of Within-student Change from Winter 2019-Fall 2019 vs. Winter 2020-Fall 2020 in Math

It was widely speculated that the COVID-19 pandemic would lead to very unequal opportunities for learning depending on whether students had access to technology and parental support during the school closures, which would result in greater heterogeneity in terms of learning gains/losses in 2020. Notably, however, we do not see evidence that within-student change is more spread out this year relative to the pre-pandemic 2019 distribution.

The long-term effects of COVID-19 are still unknown

In some ways, our findings show an optimistic picture: In reading, on average, the achievement percentiles of students in fall 2020 were similar to those of same-grade students in fall 2019, and in almost all grades, most students made some learning gains since the COVID-19 pandemic started. In math, however, the results tell a less rosy story: Student achievement was lower than the pre-COVID-19 performance by same-grade students in fall 2019, and students showed lower growth in math across grades 3 to 8 relative to peers in the previous, more typical year. Schools will need clear local data to understand if these national trends are reflective of their students. Additional resources and supports should be deployed in math specifically to get students back on track.

In this study, we limited our analyses to a consistent set of schools between fall 2019 and fall 2020. However, approximately one in four students who tested within these schools in fall 2019 are no longer in our sample in fall 2020. This is a sizeable increase from the 15% attrition from fall 2018 to fall 2019. One possible explanation is that some students lacked reliable technology. A second is that they disengaged from school due to economic, health, or other factors. More coordinated efforts are required to establish communication with students who are not attending school or disengaging from instruction to get them back on track, especially our most vulnerable students.

Finally, we are only scratching the surface in quantifying the short-term and long-term academic and non-academic impacts of COVID-19. While more students are back in schools now and educators have more experience with remote instruction than when the pandemic forced schools to close in spring 2020, the collective shock we are experiencing is ongoing. We will continue to examine students’ academic progress throughout the 2020-21 school year to understand how recovery and growth unfold amid an ongoing pandemic.

Thankfully, we know much more about the impact the pandemic has had on student learning than we did even a few months ago. However, that knowledge makes clear that there is work to be done to help many students get back on track in math, and that the long-term ramifications of COVID-19 for student learning—especially among underserved communities—remain unknown.

Related Content

Jim Soland, Megan Kuhfeld, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, Jing Liu

May 27, 2020

Amie Rapaport, Anna Saavedra, Dan Silver, Morgan Polikoff

November 18, 2020

Education Access & Equity K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Darcy Hutchins, Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nora, Carolina Campos, Adelaida Gómez Vergara, Nancy G. Gordon, Esmeralda Macana, Karen Robertson

March 28, 2024

Jennifer B. Ayscue, Kfir Mordechay, David Mickey-Pabello

March 26, 2024

Anna Saavedra, Morgan Polikoff, Dan Silver

IMAGES

COMMENTS

the world (with the COVID-19 pandemic, and without) from each student, we can directly analyze how each student believes COVID-19 has impacted their current and future outcomes.2 For example, by asking students about their current GPA in a post-COVID-19 world and their expected GPA in the absence of

Our findings on academic outcomes indicate that COVID-19 has led to a large number of students delaying graduation (13%), withdrawing from classes (11%), and intending to change majors (12%). Moreover, approximately 50% of our sample separately reported a decrease in study hours and in their academic performance.

In particular, it was hypothesized that induced changes in academic studying and relationships with friends, partner, university colleagues, professors and relatives could constitute significant perceived COVID-19 pandemic lockdown-related sources of stress among university students. Hypotheses and research questions to rigorously check the ...

As we outline in our new research study released in January, the cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic achievement has been large. We tracked changes in math and ...

In math, however, the results tell a less rosy story: Student achievement was lower than the pre-COVID-19 performance by same-grade students in fall 2019, and students showed lower growth in math ...