- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Research Summary

It’s a common perception that writing a research summary is a quick and easy task. After all, how hard can jotting down 300 words be? But when you consider the weight those 300 words carry, writing a research summary as a part of your dissertation, essay or compelling draft for your paper instantly becomes daunting task.

A research summary requires you to synthesize a complex research paper into an informative, self-explanatory snapshot. It needs to portray what your article contains. Thus, writing it often comes at the end of the task list.

Regardless of when you’re planning to write, it is no less of a challenge, particularly if you’re doing it for the first time. This blog will take you through everything you need to know about research summary so that you have an easier time with it.

What is a Research Summary?

A research summary is the part of your research paper that describes its findings to the audience in a brief yet concise manner. A well-curated research summary represents you and your knowledge about the information written in the research paper.

While writing a quality research summary, you need to discover and identify the significant points in the research and condense it in a more straightforward form. A research summary is like a doorway that provides access to the structure of a research paper's sections.

Since the purpose of a summary is to give an overview of the topic, methodology, and conclusions employed in a paper, it requires an objective approach. No analysis or criticism.

Research summary or Abstract. What’s the Difference?

They’re both brief, concise, and give an overview of an aspect of the research paper. So, it’s easy to understand why many new researchers get the two confused. However, a research summary and abstract are two very different things with individual purpose. To start with, a research summary is written at the end while the abstract comes at the beginning of a research paper.

A research summary captures the essence of the paper at the end of your document. It focuses on your topic, methods, and findings. More like a TL;DR, if you will. An abstract, on the other hand, is a description of what your research paper is about. It tells your reader what your topic or hypothesis is, and sets a context around why you have embarked on your research.

Getting Started with a Research Summary

Before you start writing, you need to get insights into your research’s content, style, and organization. There are three fundamental areas of a research summary that you should focus on.

- While deciding the contents of your research summary, you must include a section on its importance as a whole, the techniques, and the tools that were used to formulate the conclusion. Additionally, there needs to be a short but thorough explanation of how the findings of the research paper have a significance.

- To keep the summary well-organized, try to cover the various sections of the research paper in separate paragraphs. Besides, how the idea of particular factual research came up first must be explained in a separate paragraph.

- As a general practice worldwide, research summaries are restricted to 300-400 words. However, if you have chosen a lengthy research paper, try not to exceed the word limit of 10% of the entire research paper.

How to Structure Your Research Summary

The research summary is nothing but a concise form of the entire research paper. Therefore, the structure of a summary stays the same as the paper. So, include all the section titles and write a little about them. The structural elements that a research summary must consist of are:

It represents the topic of the research. Try to phrase it so that it includes the key findings or conclusion of the task.

The abstract gives a context of the research paper. Unlike the abstract at the beginning of a paper, the abstract here, should be very short since you’ll be working with a limited word count.

Introduction

This is the most crucial section of a research summary as it helps readers get familiarized with the topic. You should include the definition of your topic, the current state of the investigation, and practical relevance in this part. Additionally, you should present the problem statement, investigative measures, and any hypothesis in this section.

Methodology

This section provides details about the methodology and the methods adopted to conduct the study. You should write a brief description of the surveys, sampling, type of experiments, statistical analysis, and the rationality behind choosing those particular methods.

Create a list of evidence obtained from the various experiments with a primary analysis, conclusions, and interpretations made upon that. In the paper research paper, you will find the results section as the most detailed and lengthy part. Therefore, you must pick up the key elements and wisely decide which elements are worth including and which are worth skipping.

This is where you present the interpretation of results in the context of their application. Discussion usually covers results, inferences, and theoretical models explaining the obtained values, key strengths, and limitations. All of these are vital elements that you must include in the summary.

Most research papers merge conclusion with discussions. However, depending upon the instructions, you may have to prepare this as a separate section in your research summary. Usually, conclusion revisits the hypothesis and provides the details about the validation or denial about the arguments made in the research paper, based upon how convincing the results were obtained.

The structure of a research summary closely resembles the anatomy of a scholarly article . Additionally, you should keep your research and references limited to authentic and scholarly sources only.

Tips for Writing a Research Summary

The core concept behind undertaking a research summary is to present a simple and clear understanding of your research paper to the reader. The biggest hurdle while doing that is the number of words you have at your disposal. So, follow the steps below to write a research summary that sticks.

1. Read the parent paper thoroughly

You should go through the research paper thoroughly multiple times to ensure that you have a complete understanding of its contents. A 3-stage reading process helps.

a. Scan: In the first read, go through it to get an understanding of its basic concept and methodologies.

b. Read: For the second step, read the article attentively by going through each section, highlighting the key elements, and subsequently listing the topics that you will include in your research summary.

c. Skim: Flip through the article a few more times to study the interpretation of various experimental results, statistical analysis, and application in different contexts.

Sincerely go through different headings and subheadings as it will allow you to understand the underlying concept of each section. You can try reading the introduction and conclusion simultaneously to understand the motive of the task and how obtained results stay fit to the expected outcome.

2. Identify the key elements in different sections

While exploring different sections of an article, you can try finding answers to simple what, why, and how. Below are a few pointers to give you an idea:

- What is the research question and how is it addressed?

- Is there a hypothesis in the introductory part?

- What type of methods are being adopted?

- What is the sample size for data collection and how is it being analyzed?

- What are the most vital findings?

- Do the results support the hypothesis?

Discussion/Conclusion

- What is the final solution to the problem statement?

- What is the explanation for the obtained results?

- What is the drawn inference?

- What are the various limitations of the study?

3. Prepare the first draft

Now that you’ve listed the key points that the paper tries to demonstrate, you can start writing the summary following the standard structure of a research summary. Just make sure you’re not writing statements from the parent research paper verbatim.

Instead, try writing down each section in your own words. This will not only help in avoiding plagiarism but will also show your complete understanding of the subject. Alternatively, you can use a summarizing tool (AI-based summary generators) to shorten the content or summarize the content without disrupting the actual meaning of the article.

SciSpace Copilot is one such helpful feature! You can easily upload your research paper and ask Copilot to summarize it. You will get an AI-generated, condensed research summary. SciSpace Copilot also enables you to highlight text, clip math and tables, and ask any question relevant to the research paper; it will give you instant answers with deeper context of the article..

4. Include visuals

One of the best ways to summarize and consolidate a research paper is to provide visuals like graphs, charts, pie diagrams, etc.. Visuals make getting across the facts, the past trends, and the probabilistic figures around a concept much more engaging.

5. Double check for plagiarism

It can be very tempting to copy-paste a few statements or the entire paragraphs depending upon the clarity of those sections. But it’s best to stay away from the practice. Even paraphrasing should be done with utmost care and attention.

Also: QuillBot vs SciSpace: Choose the best AI-paraphrasing tool

6. Religiously follow the word count limit

You need to have strict control while writing different sections of a research summary. In many cases, it has been observed that the research summary and the parent research paper become the same length. If that happens, it can lead to discrediting of your efforts and research summary itself. Whatever the standard word limit has been imposed, you must observe that carefully.

7. Proofread your research summary multiple times

The process of writing the research summary can be exhausting and tiring. However, you shouldn’t allow this to become a reason to skip checking your academic writing several times for mistakes like misspellings, grammar, wordiness, and formatting issues. Proofread and edit until you think your research summary can stand out from the others, provided it is drafted perfectly on both technicality and comprehension parameters. You can also seek assistance from editing and proofreading services , and other free tools that help you keep these annoying grammatical errors at bay.

8. Watch while you write

Keep a keen observation of your writing style. You should use the words very precisely, and in any situation, it should not represent your personal opinions on the topic. You should write the entire research summary in utmost impersonal, precise, factually correct, and evidence-based writing.

9. Ask a friend/colleague to help

Once you are done with the final copy of your research summary, you must ask a friend or colleague to read it. You must test whether your friend or colleague could grasp everything without referring to the parent paper. This will help you in ensuring the clarity of the article.

Once you become familiar with the research paper summary concept and understand how to apply the tips discussed above in your current task, summarizing a research summary won’t be that challenging. While traversing the different stages of your academic career, you will face different scenarios where you may have to create several research summaries.

In such cases, you just need to look for answers to simple questions like “Why this study is necessary,” “what were the methods,” “who were the participants,” “what conclusions were drawn from the research,” and “how it is relevant to the wider world.” Once you find out the answers to these questions, you can easily create a good research summary following the standard structure and a precise writing style.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Surveys Academic Research

Research Summary: What is it & how to write one

The Research Summary is used to report facts about a study clearly. You will almost certainly be required to prepare a research summary during your academic research or while on a research project for your organization.

If it is the first time you have to write one, the writing requirements may confuse you. The instructors generally assign someone to write a summary of the research work. Research summaries require the writer to have a thorough understanding of the issue.

This article will discuss the definition of a research summary and how to write one.

What is a research summary?

A research summary is a piece of writing that summarizes your research on a specific topic. Its primary goal is to offer the reader a detailed overview of the study with the key findings. A research summary generally contains the article’s structure in which it is written.

You must know the goal of your analysis before you launch a project. A research overview summarizes the detailed response and highlights particular issues raised in it. Writing it might be somewhat troublesome. To write a good overview, you want to start with a structure in mind. Read on for our guide.

Why is an analysis recap so important?

Your summary or analysis is going to tell readers everything about your research project. This is the critical piece that your stakeholders will read to identify your findings and valuable insights. Having a good and concise research summary that presents facts and comes with no research biases is the critical deliverable of any research project.

We’ve put together a cheat sheet to help you write a good research summary below.

Research Summary Guide

- Why was this research done? – You want to give a clear description of why this research study was done. What hypothesis was being tested?

- Who was surveyed? – The what and why or your research decides who you’re going to interview/survey. Your research summary has a detailed note on who participated in the study and why they were selected.

- What was the methodology? – Talk about the methodology. Did you do face-to-face interviews? Was it a short or long survey or a focus group setting? Your research methodology is key to the results you’re going to get.

- What were the key findings? – This can be the most critical part of the process. What did we find out after testing the hypothesis? This section, like all others, should be just facts, facts facts. You’re not sharing how you feel about the findings. Keep it bias-free.

- Conclusion – What are the conclusions that were drawn from the findings. A good example of a conclusion. Surprisingly, most people interviewed did not watch the lunar eclipse in 2022, which is unexpected given that 100% of those interviewed knew about it before it happened.

- Takeaways and action points – This is where you bring in your suggestion. Given the data you now have from the research, what are the takeaways and action points? If you’re a researcher running this research project for your company, you’ll use this part to shed light on your recommended action plans for the business.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

If you’re doing any research, you will write a summary, which will be the most viewed and more important part of the project. So keep a guideline in mind before you start. Focus on the content first and then worry about the length. Use the cheat sheet/checklist in this article to organize your summary, and that’s all you need to write a great research summary!

But once your summary is ready, where is it stored? Most teams have multiple documents in their google drives, and it’s a nightmare to find projects that were done in the past. Your research data should be democratized and easy to use.

We at QuestionPro launched a research repository for research teams, and our clients love it. All your data is in one place, and everything is searchable, including your research summaries!

Authors: Prachi, Anas

MORE LIKE THIS

Customer Communication Tool: Types, Methods, Uses, & Tools

Apr 23, 2024

Top 12 Sentiment Analysis Tools for Understanding Emotions

QuestionPro BI: From Research Data to Actionable Dashboards

Apr 22, 2024

21 Best Customer Experience Management Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Research Summary: What Is It & How To Write One

Introduction

A research summary is a requirement during academic research and sometimes you might need to prepare a research summary during a research project for an organization.

Most people find a research summary a daunting task as you are required to condense complex research material into an informative, easy-to-understand article most times with a minimum of 300-500 words.

In this post, we will guide you through all the steps required to make writing your research summary an easier task.

What is a Research Summary?

A research summary is a piece of writing that summarizes the research of a specific topic into bite-size easy-to-read and comprehend articles. The primary goal is to give the reader a detailed outline of the key findings of a research.

It is an unavoidable requirement in colleges and universities. To write a good research summary, you must understand the goal of your research, as this would help make the process easier.

A research summary preserves the structure and sections of the article it is derived from.

Research Summary or Abstract: What’s The Difference?

The Research Summary and Abstract are similar, especially as they are both brief, straight to the point, and provide an overview of the entire research paper. However, there are very clear differences.

To begin with, a Research summary is written at the end of a research activity, while the Abstract is written at the beginning of a research paper.

A Research Summary captures the main points of a study, with an emphasis on the topic, method , and discoveries, an Abstract is a description of what your research paper would talk about and the reason for your research or the hypothesis you are trying to validate.

Let us take a deeper look at the difference between both terms.

What is an Abstract?

An abstract is a short version of a research paper. It is written to convey the findings of the research to the reader. It provides the reader with information that would help them understand the research, by giving them a clear idea about the subject matter of a research paper. It is usually submitted before the presentation of a research paper.

What is a Summary?

A summary is a short form of an essay, a research paper, or a chapter in a book. A research summary is a narration of a research study, condensing the focal points of research to a shorter form, usually aligned with the same structure of the research study, from which the summary is derived.

What Is The Difference Between an Abstract and a Summary?

An abstract communicates the main points of a research paper, it includes the questions, major findings, the importance of the findings, etc.

An abstract reflects the perceptions of the author about a topic, while a research summary reflects the ideology of the research study that is being summarized.

Getting Started with a Research Summary

Before commencing a research summary, there is a need to understand the style and organization of the content you plan to summarize. There are three fundamental areas of the research that should be the focal point:

- When deciding on the content include a section that speaks to the importance of the research, and the techniques and tools used to arrive at your conclusion.

- Keep the summary well organized, and use paragraphs to discuss the various sections of the research.

- Restrict your research to 300-400 words which is the standard practice for research summaries globally. However, if the research paper you want to summarize is a lengthy one, do not exceed 10% of the entire research material.

Once you have satisfied the requirements of the fundamentals for starting your research summary, you can now begin to write using the following format:

- Why was this research done? – A clear description of the reason the research was embarked on and the hypothesis being tested.

- Who was surveyed? – Your research study should have details of the source of your information. If it was via a survey, you should document who the participants of the survey were and the reason that they were selected.

- What was the methodology? – Discuss the methodology, in terms of what kind of survey method did you adopt. Was it a face-to-face interview, a phone interview, or a focus group setting?

- What were the key findings? – This is perhaps the most vital part of the process. What discoveries did you make after the testing? This part should be based on raw facts free from any personal bias.

- Conclusion – What conclusions did you draw from the findings?

- Takeaways and action points – This is where your views and perception can be reflected. Here, you can now share your recommendations or action points.

- Identify the focal point of the article – In other to get a grasp of the content covered in the research paper, you can skim the article first, in a bid to understand the most essential part of the research paper.

- Analyze and understand the topic and article – Writing a summary of a research paper involves being familiar with the topic – the current state of knowledge, key definitions, concepts, and models. This is often gleaned while reading the literature review. Please note that only a deep understanding ensures efficient and accurate summarization of the content.

- Make notes as you read – Highlight and summarize each paragraph as you read. Your notes are what you would further condense to create a draft that would form your research summary.

How to Structure Your Research Summary

- Title – This highlights the area of analysis, and can be formulated to briefly highlight key findings.

- Abstract – this is a very brief and comprehensive description of the study, required in every academic article, with a length of 100-500 words at most.

- Introduction – this is a vital part of any research summary, it provides the context and the literature review that gently introduces readers to the subject matter. The introduction usually covers definitions, questions, and hypotheses of the research study.

- Methodology –This section emphasizes the process and or data analysis methods used, in terms of experiments, surveys, sampling, or statistical analysis.

- Results section – this section lists in detail the results derived from the research with evidence obtained from all the experiments conducted.

- Discussion – these parts discuss the results within the context of current knowledge among subject matter experts. Interpretation of results and theoretical models explaining the observed results, the strengths of the study, and the limitations experienced are going to be a part of the discussion.

- Conclusion – In a conclusion, hypotheses are discussed and revalidated or denied, based on how convincing the evidence is.

- References – this section is for giving credit to those who work you studied to create your summary. You do this by providing appropriate citations as you write.

Research Summary Example 1

Below are some defining elements of a sample research summary.

Title – “The probability of an unexpected volcanic eruption in Greenwich”

Introduction – this section would list the catastrophic consequences that occurred in the country and the importance of analyzing this event.

Hypothesis – An eruption of the Greenwich supervolcano would be preceded by intense preliminary activity manifesting in advance, before the eruption.

Results – these could contain a report of statistical data from various volcanic eruptions happening globally while looking critically at the activity that occurred before these events.

Discussion and conclusion – Given that Greenwich is now consistently monitored by scientists and that signs of an eruption are usually detected before the volcanic eruption, this confirms the hypothesis. Hence creating an emergency plan outlining other intervention measures and ultimately evacuation is essential.

Research Summary Example 2

Below is another sample sketch.

Title – “The frequency of extreme weather events in the UK in 2000-2008 as compared to the ‘60s”

Introduction – Weather events bring intense material damage and cause pain to the victims affected.

Hypothesis – Extreme weather events are more frequent in recent times compared to the ‘50s

Results – The frequency of several categories of extreme events now and then are listed here, such as droughts, fires, massive rainfall/snowfalls, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, etc.

Discussion and conclusion – Several types of extreme events have become more commonplace in recent times, confirming the hypothesis. This rise in extreme weather events can be traced to rising CO2 levels and increasing temperatures and global warming explain the rising frequency of these disasters. Addressing the rising CO2 levels and paying attention to climate change is the only to combat this phenomenon.

A research summary is the short form of a research paper, analyzing the important aspect of the study. Everyone who reads a research summary has a full grasp of the main idea being discussed in the original research paper. Conducting any research means you will write a summary, which is an important part of your project and would be the most read part of your project.

Having a guideline before you start helps, this would form your checklist which would guide your actions as you write your research summary. It is important to note that a Research Summary is different from an Abstract paper written at the beginning of a research paper, describing the idea behind a research paper.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- abstract in research papers

- abstract writing

- action research

- research summary

- research summary vs abstract

- research surveys

- Angela Kayode-Sanni

You may also like:

Action Research: What it is, Stages & Examples

Introduction Action research is an evidence-based approach that has been used for years in the field of education and social sciences....

The McNamara Fallacy: How Researchers Can Detect and to Avoid it.

Introduction The McNamara Fallacy is a common problem in research. It happens when researchers take a single piece of data as evidence...

Research Questions: Definitions, Types + [Examples]

A comprehensive guide on the definition of research questions, types, importance, good and bad research question examples

How to Write An Abstract For Research Papers: Tips & Examples

In this article, we will share some tips for writing an effective abstract, plus samples you can learn from.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

- IRB-SBS Home

- Contact IRB-SBS

- IRB SBS Staff Directory

- IRB SBS Board Members

- About the IRB-SBS

- CITI Training

- Education Events

- Virginia IRB Consortium

- IRB-SBS Learning Shots

- HRPP Education & Training

- Student Support

- Access iProtocol

- Getting Started

- iProtocol Question Guide

- iProtocol Management

- Protocol Review Process

- Certificate of Confidentiality

- Deception and/or Withholding Information from a Participant

- Ethnographic Research

- IRB-SBS 101

- IRB-SBS Glossary

- Participant Pools

- Paying Participants

- Research in an Educational Setting

- Research in an International Setting and/or Location

- Risk-Sensitive Populations

- Student Researchers and Faculty Sponsors

- Study Funding and the IRB

- Understanding Risk in Research

- Vulnerable Participants

- IRB-SBS PAM & Ed

- Federal Regulations

- Ethical Principals

- Partner Offices

- Determining Human Subjects Research

- Determining HSR or SBS

Participant Summary

The Participant Summary section assembles all of the created Participant Groups and combines the number of participants provided in each group into a grand total. In addition it provides an opportunity to highlight the experience of the principal investigator and the research team (where applicable), as well as describe the relationship that the principal investigator and any other individuals associated with the study have with the participants.

Researcher experience

Researcher experience is an important factor when the IRB-SBS weighs the risks of the study against its potential benefits. An experienced researcher who is familiar with a population and knows how to work sensitively with them is far more likely to yield generalizable results while understanding how to best protect a participant as compared with an undergraduate student embarking on his or her first study. That said, it doesn’t mean that the undergraduate’s researcher isn’t valuable but rather the researcher may need to design a study that has reduced risk and also needs to demonstrate that he or she has adequate supervision through their faculty sponsor. Providing a good description of the principal investigator’s experience as well as the rest of the research team (where applicable) can help the IRB-SBS have a better understanding of the overall experience level of the group and how prepared they are to work with their proposed participants.

Researcher relationships

Providing consent free of coercion is a central tenant of the ethical foundation for human subjects research. Even though a researcher may assure a participant that they can participate without pressure, simply being a subordinate of the researcher may make the participant feel compelled to participate. The IRB-SBS will want to know if anyone on the research team holds any authority over their participants or if there is any other type of relationship between participants and researchers. Being in a position of authority doesn’t necessarily preclude a researcher from including a participant, but the IRB-SBS may require specific steps be put in place to create layers of separation between the researcher and participant.

In addition, the final question asks about financial relationships. It is important for the IRB-SBS to understand any relevant financial relationships that may create a conflict of interest for researchers.

- The questions have been answered adequately.

- The researcher will take appropriate precautions to protect participants from coercion.

- The researcher’s experience is appropriate for the study.

- Funding and the IRB-SBS

Bulk Content Generator

Brand Voice

AI Text Editor

Research Summary Generator

Craft a detailed research synopsis utilizing the given data for an all-encompassing understanding.

Try Research Summary for free →

Research Summary

Learn how to provide the key points, main findings, and any other relevant information for the research you want to summarize

1 variation

What is a Research Summary?

Have you ever found yourself drowning in a sea of research articles, struggling to make sense of it all? Well, fear not! A research summary is here to save the day. But what exactly is a research summary, and how can it help you navigate the vast ocean of information?

A research summary is a concise and informative overview of a research article, report, or thesis. It aims to provide the reader with a clear understanding of the study's purpose, methods, results, and conclusions without having to read the entire document. Think of it as a mini-version of the original work that highlights its most important aspects.

Now that we know what a research summary is let's dive into why they're so beneficial.

The Benefits of Research Summaries

Research summaries offer several advantages for both readers and writers:

Time-saving : Reading a well-written research summary can save you hours of sifting through dense academic papers. It allows you to quickly grasp the key points and decide if you want to explore the full document further.

Improved comprehension : By breaking down complex ideas into digestible chunks, research summaries make it easier for readers to understand the material. This is particularly helpful for those who are new to a topic or have limited knowledge in the field.

Enhanced communication : Research summaries enable researchers to share their findings with a wider audience, including non-experts and industry professionals. This can lead to increased collaboration and knowledge exchange across disciplines.

Better decision-making : For professionals who rely on evidence-based practices, research summaries provide an accessible way to stay informed about the latest developments in their field. This enables them to make better decisions based on up-to-date information.

With these benefits in mind, let's explore some tips for writing an effective research summary.

Tips for Writing a Great Research Summary

Creating an engaging and informative research summary doesn't have to be a daunting task. Here are some tips to help you craft the perfect summary:

Know your audience : Consider who will be reading your summary and tailor your language and content accordingly. If you're writing for a general audience, avoid jargon and technical terms. If your readers are experts in the field, focus on the most relevant and novel aspects of the research.

Be concise : A research summary should be brief yet informative. Aim to capture the essence of the study without getting bogged down in unnecessary details.

Use clear language : Write in simple, straightforward sentences that are easy to understand. Avoid flowery language or complex sentence structures that may confuse readers.

Highlight key points : Focus on the main elements of the study, such as its purpose, methods, results, and conclusions. Make sure these points stand out by using headings, bullet points, or bold text.

Stay objective : Present the information in a neutral tone and avoid expressing personal opinions or biases. Stick to the facts and let your readers draw their own conclusions.

Proofread : Before submitting your research summary, take the time to proofread it carefully for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. A polished summary will make a better impression on your readers.

Generate the Perfect Research Summary with Our Research Summary Generator

Now that we've covered what a research summary is, its benefits, and tips for writing one – wouldn't it be great if there was a tool that could generate a perfect research summary every single time? Well, guess what? There is!

With our Research Summary Generator, you can create an engaging and informative summary in just a few clicks. Say goodbye to hours spent poring over dense academic papers and hello to quick, easy-to-understand summaries tailored to your needs.

Give it a try today and see how our Research Summary Generator can revolutionize your research process!

Example outputs

This Research Summary Generator saves you time and effort by summarizing your research findings in a clear and concise manner, allowing you to easily communicate your results to others.

The Effects of Exercise on Mental Health

A study was conducted to investigate the effects of exercise on mental health. Participants were randomly assigned to either an exercise group or a control group. The exercise group engaged in moderate-intensity aerobic exercise for 30 minutes, three times per week for eight weeks. The results showed that the exercise group had significantly lower levels of depression and anxiety compared to the control group.

Keywords: exercise, mental health, depression, anxiety

The impact of social media on body image.

This study aimed to examine the impact of social media on body image. A sample of young adults completed surveys assessing their use of social media and their perceptions of their own body image. Results indicated that individuals who spent more time on social media reported greater dissatisfaction with their bodies. Additionally, exposure to images of thin and fit individuals on social media was associated with increased body dissatisfaction.

Keywords: social media, body image, young adults, body dissatisfaction

The benefits of meditation for stress reduction.

This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of meditation for stress reduction. A total of 18 randomized controlled trials were included in the analysis. Results showed that meditation was effective in reducing perceived stress, with larger effect sizes observed for mindfulness-based interventions. Furthermore, the benefits of meditation appeared to be maintained over time.

Keywords: meditation, stress reduction, mindfulness, meta-analysis

What other amazing things can this template help you create.

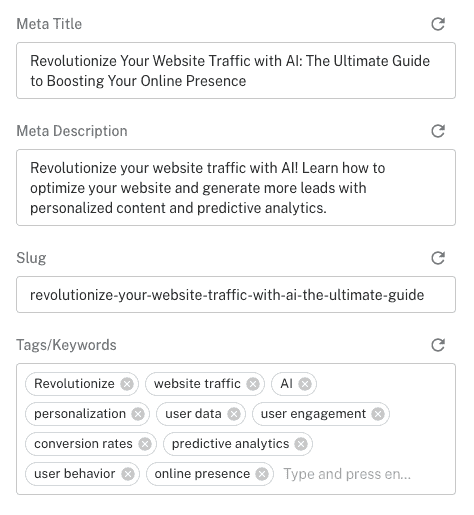

✔ Meta Title

✔ Meta Description

✔ Extract keywords

✔ Feature Image

✔ Soon Internal Linking

Who needs Research Summary Generator?

Researchers

Graduate students

Business professionals

Frequently asked questions

- How does the Research Summary Generator work? Simply input your research findings into the generator, and it will automatically summarize them in a clear and concise manner.

- Can I customize the generated summary? Yes, you can edit the summary as needed to ensure it accurately reflects your research findings.

- Is the Research Summary Generator free to use? Yes, the generator is completely free to use with no limitations.

This site uses session cookies and persistent cookies to improve the content and structure of the site.

By clicking “ Accept All Cookies ”, you agree to the storing of cookies on this device to enhance site navigation and content, analyse site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

By clicking ' See cookie policy ' you can review and change your cookie preferences and enable the ones you agree to.

By dismissing this banner , you are rejecting all cookies and therefore we will not store any cookies on this device.

Communicating study findings to participants: guidance

This guidance is about communicating study findings (results) to participants. As well as making study findings public , findings should be shared directly to those who participated in the study. Communicating study findings is different to communicating individual health-related findings. Study findings refer to interim or overall results of a study, whereas individual health-related findings refer to results specific to a participant. We have separate guidance for communicating individual health-related findings to participants.

This guidance is for researchers, chief investigators, funders, and sponsors who are responsible for sharing findings to participants. All types of research studies should consider communicating study findings to participants. The UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research states that study findings should be published as well as being summarised and shared with those who took part.. This guidance will help you to plan the best way to do this.

This guidance covers:

- why it’s important to communicate findings to participants

- why it’s important to plan it early on

- what to consider when communicating findings to participants

- useful resources to help you

Why it’s important to communicate findings

Research participants have a right to know the findings of the research study they took part in. Sharing research findings should go beyond publishing results in registries or academic journals, where technical or academic language is used that participants may not understand. Sharing findings directly with participants helps to build trust, show respect, and helps participants to feel valued.

Why it’s important to plan it early on

How you’ll share findings with your participants should form part of the study plan. You may need to factor it into your funding application. You’ll also need to include information about your proposed approach in your application for approvals and participant information sheets . When planning, you’ll need to consider the following:

a) Public Involvement

You should involve relevant people early in the design of your study. This may mean involving patients, service users, carers, other advocates or members of the public. Engaging with relevant people early on will help you to decide how to share findings with participants. Our public involvement webpages have lots of information and guidance to help you.

Sharing findings with participants may require additional funding and resources. You may need to include these in grant or fund applications. You may prefer to consider low cost options, such as sharing information electronically. Discuss this with your public involvement group.

c) Including information in your participant information sheets and approval application

Though the material used for sharing study findings does not need to be submitted for regulatory review, your research application should include an outline about how you plan to share findings to participants.

You should set out your plans to communicate findings to participants in the participant information . Make participants aware of the likely timing of communication about findings so that they know when and how to expect this information.

It is important that you comply with UK GDPR and data protection legislation. To meet the transparency principle, you should explain to participants how you will collect, store and use their contact details, and how and when you will communicate findings.

Participants should not be surprised by receiving study findings or how they have been sent to them. To comply with the legislation, you should make sure you minimise the amount of personal data you use. That means you should only use another organisation to manage communication if other methods are not feasible. If you are using another organisation to manage communication to participants, you should make sure that this is explained to participants. This should include clear information about how and why the other organisation will use their data, and what controls are in place.

You should also make participants aware of their right to object to the processing of their personal data for the communication of research findings.

Participants should have a choice as to whether they receive findings and should be allowed to record if they change their mind during the study.

If you later change your plan for communicating findings to participants, or if you didn’t include details in your initial application but later decide to, then you’ll need to submit an amendment. The amendment should include:

- details of how and when you plan to communicate findings,

- a process to record participants’ choice about receiving findings or not,

- if the study is still recruiting, then you will also need to update the general consent form and participant information.

What to consider when communicating findings to participants

The following information outlines the different aspects to consider when planning your communication of findings. Discuss these aspects with your public involvement contributors at the planning and design stage of your study.

a) who will receive the findings

You should offer a summary of study findings directly to participants. This is in addition to any findings made publicly available.

In some instances, it may be expected that participants could die or lose capacity during the study. In these cases, it may be appropriate to share findings with participants’ relatives or carers. Give immediate family members/carers the choice. Plan early for this to ensure you receive the appropriate consent for storing contact details for this purpose or have put other appropriate mechanisms in place to allow you to share results with participants.

If your participants are children you should also consider how you’ll adapt your communication to ensure it is accessible for them and their family members/carers.

b) how you’ll communicate the findings

There are various ways to share findings with participants. It’s valuable to discuss the options with your public involvement group. Commonly used methods are:

- end of study information sheet or newsletter

- verbal information provided at study visits

- study websites

- study social media accounts

The way you communicate will depend on the type of study and your audience. For example, digital options may not be accessible for everyone – some participants may not be computer literate or may not want to use technology to access findings. Where using a digital option, it may be beneficial for participants if this is also supplemented with hard copy information.

You should consider who your audience is so that you can tailor your communication to be effective. To ensure the findings will be understood by your audience, consider using different versions for different audiences, such as children or adults lacking capacity. You might want to adjust how much detail you provide on your findings depending on the audience.

Where your research study does not collect contact details of participants, it may not be possible to share findings directly to participants. You may wish to include details in the participant information sheet about where findings will be published, so participants can choose to read the findings if they want to. For other types of studies, it may be appropriate to collect email addresses and provide updates that way. Alternatively, you may, with appropriate consent, arrange for a third party to hold contact details solely for the purpose of communicating study updates and findings. For in-person studies, you may decide to share updates and findings during study visits.

Regardless of the type of study and your audience, write your findings in lay language. We provide further guidance on how to write a plain language summary of your research findings .

c) giving participants a choice

While most participants/their relatives or carers will want to receive study findings, some may not. Those who might not wish to receive findings or updates should be given a choice at the start of the study and again during it. You should plan for how people can indicate their choice during the study.

Your participant-facing information should include details about how and when you’ll share study findings. Use the consent form to record the choice participants/their relatives or carers make about receiving findings. You’ll need to take this into consideration when deciding your method for communicating findings.

You need to take three different aspects into account when thinking about how participants or their relatives or carers can make choices about receiving study findings.

- Common law duty of confidentiality – people’s contact details are part of their health and care data when used alongside information about their health or care. That means that you need to get their consent to use these details for sending information about study findings.

- UK GDPR and other legislation – you do not need to obtain GDPR-compliant consent, because your organisation can rely on public task or legitimate interests to send out research findings. That means that the consent for sending study findings can be kept simple and does not need to meet all the legal requirements for consent under GDPR. Communicating findings to individuals about research they have been involved in is not direct marketing if such an activity falls within your organisation’s task or function. Therefore, you don’t need to comply with the direct marketing consent requirement or other rules under the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations ( PECR ).

- Ethics – it’s important that people feel that they can make choices, and that they can change their mind at any time.

The choices about receiving study findings should be separate from the choices about participating in the study. You should consider whether to offer people choices about how they will be contacted, for example by text, email or post as appropriate.

Participants might change their minds as the study progresses. It’s important that you plan to give participants another opportunity to either receive study findings or not. You should make it clear how people can change their choices about receiving study findings, and you should make sure that you can add or remove people from your communication system in accordance with their wishes. Consider also what you’ll do if a participant withdraws during your study. They may decide that they no longer want to receive study findings.

d) responsibility for communicating findings

This will depend on the way you’re sharing the findings. If sharing findings in-person during a study visit, the site team or usual care team may need to take responsibility for this process. If sharing findings via email or post, we recommend that the central study team takes responsibility. When planning your study, decide who is taking responsibility for sharing findings and how this will be funded and resourced. Where you will rely on local teams to provide findings to participants, you should discuss the logistics with representative parties. You can formalise arrangements in study site agreements and contracts.

Your public involvement group may have a preference about who is best placed to communicate study findings. Some findings could be upsetting to participants, for example if they find out that the intervention had no effect, or that study findings were negative or inconclusive. You should still offer to share these findings to participants, explaining that their contribution was important and worthwhile. If you’re communicating findings that may distress or upset participants, consider communicating more individually, such as through a discussion with a research nurse or doctor. When you communicate findings, make sure to include the details of someone that participants can get in touch with if they have any questions or want to discuss the findings in more detail. That person should also be able to point people directly to the sponsor’s Data Protection Officer, or the latter’s details should be provided at the bottom of each communication (along with a reminder of how to withdraw consent from receiving future communications of the same type).

e) exceptions

There may be occasions where it isn’t possible to share study findings directly to participants. For example, a study using anonymised tissue samples or a study using patient identifiable data without consent (approved by the Confidentiality Advice Group under section 251 of the NHS Act 2006) may not be able to share findings to participants. Where you cannot provide findings to participants directly, you should make this clear in your participant-facing information or patient notification materials . Where it’s not possible to share findings directly to participants, you should still publish findings. It may be possible to provide a website link to where the findings will be shared, and include this in participant-facing information at the start of the study.

f) when to communicate findings

When and how often you communicate findings depends on the type of research. For some studies, it will be possible to share interim findings or updates throughout the duration of the study, whereas other studies will only have findings right at the end. For a study with several phases or lots of endpoints, you may want to share findings for each of these as the study progresses. If doing so, it’s important to consider how sharing of results at multiple timepoints may influence the overall study design.

You might want to stagger information, giving participants some information when their involvement in the study is over and some at the end of the study. Keeping in contact with participants in this way helps them feel connected to the research even though their involvement has ended. You should discuss this with your public involvement group.

g) evaluate your communication

More research is needed to evaluate communication of findings strategies and determine best practice. Where possible, you should evaluate your communication methods (ideally in a randomised Study Within a Trial) to establish how effective your strategy is, and whether it has had the impact that you wanted. Depending on when you feedback results to participants, your strategy could become a retention intervention in and of itself.

Useful Resources

- Parkinson’s UK has a research communications toolkit developed with the HRA and our Research Ethics Committees. The Staying Connected Toolkit is a resource for research teams to use to achieve gold standard practices for communicating with participants throughout the course of the study.

This toolkit covers:

- general principles and timelines for communicating with participants throughout their research journey

- how to plan research communications ahead of time

- simple standardised tools and templates to help researchers to easily communicate with participants during the study

- guidance on how to build a sustainable relationship with the research participant community

2. The RECAP project provides stakeholder-informed guidance on sharing summaries of trial findings

3. The Show RESPECT study looks at the best ways to share study findings with participants

4. The Knowledge Mobilisation Alliance have created an infographic sharing 10 recommendations for communicating research findings to patients and the public

5. Our guidance on developing a plain language summary of your research findings

6. Our guidance on consent and UK GDPR

7. Guidance on What is and isn’t direct marketing? by NHS Transformation Directorate (england.nhs.uk).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Katie Gillies from the University of Aberdeen, Professor Matt Sydes and Annabelle South from University College London and Amelia Hursey from Parkinson's Europe, as well as all our public contributors, Anne-Laure Donskoy, Dianna Moylan and Mary Nettle, for their invaluable contribution to creating this guidance.

- Privacy notice

- Terms & conditions

- Accessibility statement

- Feedback or concerns

- How it works

Online Usability Testing

Understand user behavior on your website.

Mobile & Tablet UX Testing

Test usability on mobile devices and tablets.

Moderated Testing

Conduct live, guided user testing sessions.

Information Architecture Testing

Design or refine your information architecture.

Unmoderated Testing

Allow users to test without assistance.

True Intent Studies

Understand visitors’ goals and satisfaction.

A/B Testing

Determine which design performs better.

UX Benchmarking

Analyze your website against competitors.

Prototype Testing

Optimize design before development.

Search Engine Findability

Measure ease of finding your online properties.

Explore all Loop11 features →

Reporting Features

AI Insights

Gain deeper insights using the power of AI.

Clickstream Analytics

Track users’ clicks and navigation patterns.

Heatmap Analysis

Visualize user engagement and interaction.

User Session Recording & Replay

Capture user interactions for usability analysis.

Get access to all Loop11 features for free. Start free trial

- Clients & Testimonials

Written by Bridgette Hernandez

3 September, 2020

Writing good user research summaries can be hard.

They’re supposed to communicate complex, detailed user testing findings in a really concise and simple way. This can be a bit of a challenge for non-writer folks like UX designers.

Are you one of them?

If yes, you’re in the right place. This article is here to help you write clearly, so you don’t end up with a huge summary that no one really wants to read.

Keep reading to know how to write a great research summary everyone will want to get credit for.

How to Write a User Research Summary: Step-by-Step Instructions

Now, let me walk you through the nine steps of writing that epic user research summary.

Step 1. Go Over Research Findings Once Again

Used-based testing is complex. To make sense of the insights from testers, you have to pay attention to every single detail. Not to mention that some critical thinking skills are necessary to read between the lines and make meaningful recommendations.

How to make sure to cover all bases? Read/analyze/watch research materials once again before writing. Not only does this refresh your memory, but it also gives one more chance to spot something important.

So, go over the results and make notes for yourself. The goal would be to summarize the results and make it easier for yourself to structure the summary.

Step 2. Make an Outline

With the research findings and notes fresh in your mind, proceed to outline your summary. It’ll be helpful to structure your thoughts and present everything in a logical order.

There’s no magical formula for the best summary structure, but you can go for this one. It ensures a logical flow of information and covers all important areas.

Report Outline Example

- Research goals and objectives (research questions)

- Summary of the most important findings

- Methodology + participants

- The findings in more detail

- Bugs and other issues

- Recommendations.

Sounds good? If yes, read more about each section next.

Step 3. Research Goals and Objectives (Research Questions)

The first section of your report should give a quick project background. It will give context to the goals and objectives. Describing them will be the most important part to help readers understand how the project contributed to making a better product.

For example:

“For this user testing project, our team was looking to understand the user’s impressions and perceptions of ABC app.”

Consider using a bullet list to describe your goals. This format clarifies writing and is easy to spot and read.

Pro tip: Include a sentence describing the goal of your summary. It can be something like:

“This report describes the user testing process, how the data was collected, the most important results, and recommendations.”

Related: User Testing a Mobile App Prototype: Essential Checklist.

Step 4. Summary of the Most Important Findings

“So what did they find? What do I need to know?

This section should answer these questions. The findings you need to describe are the themes that occurred across more than one tester, e.g., three users struggling to understand how to complete a certain action.

Struggling to keep the sentences you’re writing short and clear? Consider getting professional writing help from tools like Hemingway Editor . Remember that a clear description is critical to making the entire summary useful.

One way to give a clear explanation is to group the findings by themes, e.g., “Navigation.” If you wish to introduce more structure, also consider giving each finding a priority value (low, medium, and high). For example, the findings that point to the most severe issues can be given a “high” priority.

Step 5. Methodology + Participants

Describe the methods that were used to complete the testing.

Say, you invited 30 people between the ages of 20 and 40 to your office and several coffee houses around the city. You asked them to test your new app and tell you their thoughts.

After they “played” with your app for about 20 minutes, you sat down with each tester and talked. So, the primary method of collecting data was an interview.

There were two parts to it. During the first part, the tester shared their experiences with the interviewer. The second part had the interviewer asking the tester a series of pre-written questions, e.g., “ Did you find it difficult to book a breakfast via our app?”

To describe this plausible UX research methodology, you can use this structure:

- Interview plan + questions . Here, list the structure of the interview, e.g., “ The interview started with a quick introduction…”

- Most important interview questions . Describe the questions in a bullet list and add your reasoning to each (see the next point)

- The reasoning behind questions. Include a short explanation of why a particular question was asked, e.g., “ With this question, we were trying to learn how to present information about additional hotel features in a way that even skeptical app users would click to see more”

- Participant description . Let the readers know how many testers participated, and give some demographic details like age, gender, and why they were chosen.

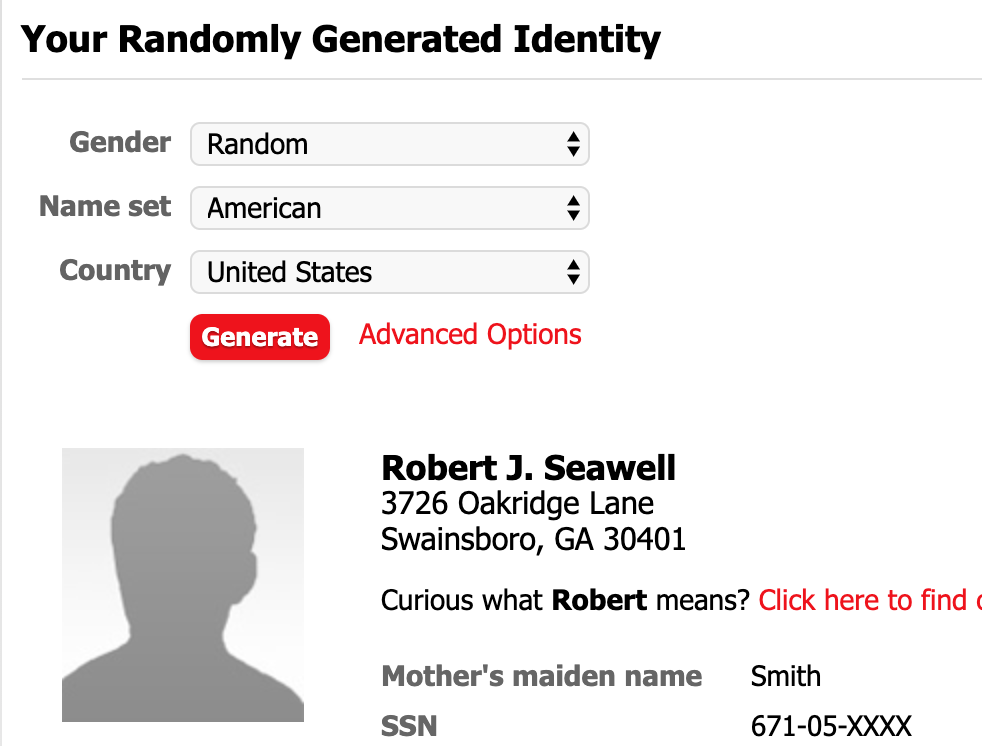

Pro tip : Consider giving the participants fake names in the summary. It’ll make them easier to remember compared to generic “Participant I” or “Participant II.” To make this process more fun, use the famous Fake Name Generator .

Related: Top 10 Questions When Recruiting Participants for User Tests.

Step 6. Test Findings, in More Detail

You’ve given some idea of test findings already, but now it’s time to really go in detail. In this section, you don’t just state the findings, but also provide your explanation of why the test ended this way.

Here’s how you can write the explanation (a very concise one, go for more details):

“The testers weren’t interested in viewing the extra booking features on the app’s home page. According to them, they rarely got to the bottom of the page where the banner was placed. To engage more users, we need to move it up close to the search feature.”

Jenny Amendola, a UX writer from SupremeDissertations , advises to “Differentiate the results by assigning values like ‘Good’ and ‘Bad’ to them. This way, you can make it easier to understand the results.”

Let the readers know how you organized, analyzed, and grouped the results into themes, too.

Step 7. Bugs and Other Issues

In this section, provide the description of problems discovered during the test that affected the results. Feel free to make it into a bullet list where each bug/issue comes with an explanation.

Categorizing them is also a good idea to clarify the text. For example…

Important! Be sure to include screenshots and images to visualize each issue. It’ll help UX designers understand what you mean.

Step 8. Recommendations

It’s time for your critical thinking genius to shine. In this section, list the ideas for improvement, from most important to least important.

Feel free to follow the structure we’ve used so far: the themes, categories, and bullet lists with explanations. Also, consider supporting each recommendation with a quote from a tester.

“Recommendation 1: We need to focus more on making extra booking options visible above the fold on the home page:

Tester review: ‘I rarely scroll down to the bottom of the home page, so I didn’t see that banner.’”

Some visuals with your recommendations could also be useful even if you create something really simple in an image processing app.

Need some help with spotting improvement opportunities and coming up with useful recommendations? Read a beginner-friendly, simple guide below to get started.

Read the Guide: A Beginner’s Guide to User Experience Testing .

Just One More Thing…

Put your name on that awesome summary.

As a UX researcher or someone involved in doing user research, you’ll be writing many more summaries in the future. Keep this outline to make the next one easier.

Happy writing!

- Recent Posts

- How to Write Actionable User Research Summaries -

Were sorry to hear about that, give us a chance to improve.

Article contents

Related articles

How to Use Rating Scale Questions in Your UX Research

Are you trying to figure out what your audience really wants? How can you improve the customer experience (CX) unless you know what they prefer? Doing user experience (UX) research can take on many different tools and tactics. One excellent way to figure out what your customers need is by conducting some rating scale question […]

How To Track The Value Of UX In Your Project

User experience projects are often ambiguous and challenging, especially in terms of tracking value. Remember the three constraints: cost, scope, and time. Stakeholders are unlikely to consider a project if it costs them much for too little value. Tracking value becomes a bit hard for UX projects for numerous reasons. *Enter UX benchmarking.* UX benchmarking […]

Screener Questions to Find Great Research Participants

Recruiting participants for user experience research is a formidable hurdle in any burgeoning project. It can be a lengthy, tedious process — full of rejections, reschedules, and no-shows. But, one foolproof way to guarantee your UX research study proceeds smoothly with little fuss is to filter out the bad apples early on. That’s where screener […]

Create your free trial account

- Free 14-day trial. Easy set-up. Cancel anytime

- No UX or coding experience required

We love sharing interesting UX topics and work by creatives out there. Follow us for weekly UX posts, inspirations and reels!

Follow us on Instagram

Maybe next time!

Research summary template

Synthesize and summarize research findings Analyze and frame problems

How to create a Research summary template

Get started with this template right now.

Research summary template frequently asked questions

Template by

Mural is the only platform that offers both a shared workspace and training on the LUMA System™, a practical way to collaborate that anyone can learn and apply.

More Research & analysis templates

.jpeg)

Trend card deck

Persona grid

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on the Return of Individual-Specific Research Results Generated in Research Laboratories; Downey AS, Busta ER, Mancher M, et al., editors. Returning Individual Research Results to Participants: Guidance for a New Research Paradigm. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018 Jul 10.

Returning Individual Research Results to Participants: Guidance for a New Research Paradigm.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

Biospecimens from research participants are an essential resource for a broad range of studies, from exploratory, basic science inquiries to clinical trials using well-validated tests. These types of research have been enormously valuable in advancing knowledge about almost every aspect of human health and disease. The conduct of research with human volunteers is dependent on a collaborative, productive relationship between participants who give their time and samples and the investigators and research teams that conduct the research. This complex relationship has many elements, but in the past the communication of individual research results to participants has generally not been one of them.

In the last several decades, questions have been raised about the practice of not returning test results generated in a research study to the study's participants; early on, much of the discussion was focused on returning results from imaging studies, while more recently the focus has moved more to the disciplines of genetics and environmental research. At the same time, the push for increased community and participant engagement across the research study life cycle and the rise of technology-enabled open science and data-sharing movements have added further momentum to the issue. Recent significant changes to federal regulations have promoted transparency and allowed individuals greater access to their clinical and research test results. These changes include the elimination of the laboratory exclusion from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy rule and revisions to the Common Rule that require prospective participants to be told during the consent process whether clinically relevant individual research results will be returned. On the other hand, the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) bars laboratories that are not CLIA certified from reporting individual research results. This creates a dilemma when research results that are clinically relevant or otherwise valuable to participants, particularly those that might not otherwise be discovered, are generated in research laboratories that are not CLIA certified. See Box S-1 for a brief description of these federal regulations. ( Box 6-1 in Chapter 6 , from which Box S-1 is adapted, includes additional laws and regulations relevant to the return of individual research results.)

HIPAA, CLIA, and the Common Rule.

Over the last couple of decades expert groups have written position statements supporting the return of individual research results and secondary findings 2 under certain conditions, such as when the results are clinically actionable, valid, and reliable. However, participant demand for individual research results is driven not just by the potential benefits that individuals could gain by learning about clinically actionable information, but also by their desire to learn about themselves from information that they would not otherwise obtain. More specific guidance is needed on how stakeholders should consider the benefits, risks, and costs associated with the return of individual research results, including the broad spectrum of results which may not be accurate, medically actionable, or have clear meaning.

Seeking guidance on these issues from a consensus body of experts representing diverse perspectives, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to conduct a study and generate a report that reviews and evaluates the ethical, societal, regulatory, and operational issues related to the return of individual-specific research results generated from research on human biospecimens. The full Statement of Task for the committee is presented in Box S-2 .

Statement of Task for the Committee on the Return of Individual-Specific Research Results Generated in Research Laboratories.

- SCOPE AND KEY TERMINOLOGY

The topic of the return of research results is exceptionally broad in scope and encompasses all fields of human research (e.g., biomedical, psychological, behavioral). During its first meeting on July 19, 2017, the committee had an opportunity to clarify the scope of the study with representatives of the three sponsoring federal agencies. In the course of that discussion, the study sponsors clarified that the committee was intended to focus on research results that are generated from the analysis of human biospecimens (samples of material collected from the human body, such as urine, blood, tissue, and cells). The committee was not to consider the return of results from imaging, behavioral, or cognitive tests, for example. Of note, the committee's charge was not limited to the return of genetic test results, as many other kinds of research are performed on human biospecimens. These include, for example, basic science studies using tumor biopsies to identify a new biomarker for colon cancer, clinical trials that evaluate blood samples for antibody levels induced by a new malaria vaccine, and epidemiological studies measuring the level of a suspected toxin in urine samples for an environmental exposure study—all of these involve laboratory tests on human biospecimens and are in the scope of this report.

In recent years, this topic has generated immense interest and debate among bioethicists and scientists, particularly in the fields of genetics and environmental exposure research. In the field of genetics, much of the debate has been focused on the return of clinically actionable secondary findings —results that were not the primary objective of the research. This is an important issue in the broader context of returning information generated in the course of research to individual participants, but the sponsors clarified that it was not intended to be a central focus of this committee's report. Instead, in this report the committee uses the term individual research results to refer to results that are generated in the course of a study to help answer the research question or otherwise support the study objectives (e.g., to determine clinical trial inclusion/exclusion) and that are specific to one participant. Distinctions can also be made between different types of individual research results according to the kind of information provided—i.e., uninterpreted data versus interpreted findings. In the genetics field there is also an ongoing discussion about the return of sequencing information, which is generally referred to as “raw data.” For the purposes of this report, all of these types of information are included in the term “individual research results.” Chapter 5 discusses ways to facilitate the understanding of different types of individual research results.

While not a primary focus of the committee's deliberations, there was recognition that secondary findings remain an important part of the discussion about returning research results, given that many sequencing and other “omics” research studies have no primary target. Moreover, the issue of returning secondary findings has a long history (e.g., in the context of returning results from imaging tests), and the committee recognized that the lessons learned from those experiences might be relevant to the committee's task. Furthermore, the committee acknowledged that the recommendations in this report may have impact beyond their application to results generated from biospecimens. In addressing its charge, the committee considered three general scenarios in which consideration of the return of individual research results is relevant:

the planned offer of anticipated individual research results to participants,

the return of individual research results upon the request of participants, and

the offer of unanticipated research results to an individual participant.