- Utility Menu

0b914002f2182447cd9e906092e539f3

Dissertation, the dissertation.

After the successful completion of the general examination, a topic and adviser for the dissertation should be chosen. Students should discuss potential topics with several faculty members before beginning. The final prospectus should be approved not later than 3 months (within the academic calendar -- September through May) of passing the general examinations in order to be considered to be making satisfactory progress toward the degree. This is the time when the Thesis Reader and Dissertation Proposal form should be completed and submitted to the department office or DGS. Three signatures are now required on the thesis acceptance certificate. Two of the three signatories must be GSAS faculty. The primary adviser must be in the department of History of Art and Architecture; the secondary adviser need not be. In addition to the primary and secondary advisers the student may have one or more other readers. Two readers must be in the department.

Thesis Defense

The Department of History of Art and Architecture requires that all Ph.D. dissertations (of students entering in September 1997 and beyond) be defended. At the defense, the student has the opportunity to present and formally discuss the dissertation with respect to its sources, findings, interpretations, and conclusions, before a Defense Committee knowledgeable in the student's field of research. The Director of the thesis is a member of the Defense committee. A committee is permitted to convene in the absence of the thesis Director only in cases of emergency or other extreme circumstances. The Defense Committee may consist of up to five members, but no fewer than three. The suggested make-up of the members of the committee should be brought to the Director of Graduate Studies for approval. Two members of this committee should be from the Department of History of Art and Architecture. One member can be outside the Department (either from another Harvard department or outside the University). The Defense will be open to department members only (faculty and graduate students), but others may be invited at the discretion of the candidate. Travel for an outside committee member is not possible at this time; exceptions are made rarely. We encourage the use of Skype or conference calling for those committee members outside of Cambridge and have accommodation for either. A modest honorarium will be given for the reading of the thesis for one member of the jury outside the University. A minimum of one month prior to scheduling the defense, a final draft of the dissertation should be submitted to two readers (normally the primary and secondary advisors). Once the two readers have informed the director of graduate studies that the dissertation is “approved for defense,” the candidate may schedule the date, room, and time for the defense in consultation with the department and the appointed committee. This date should be no less than six weeks after the time the director of graduate studies has been informed that the dissertation was approved for defense. It should be noted that preliminary approval of the thesis for defense does not guarantee that the thesis will be passed. The defense normally lasts two hours. The candidate is asked to begin by summarizing the pertinent background and findings. The summary should be kept within 20 minutes. The Chair of the Defense Committee cannot be the main thesis advisor. The Chair is responsible for allotting time, normally allowing each member of the committee 20 to 30 minutes in which to make remarks on the thesis and elicit responses from the candidate. When each committee member has finished the questioning, the committee will convene in camera for the decision. The possible decisions are: Approved; Approved with Minor Changes; Approved Subject to Major Revision (within six months); Rejected. The majority vote determines the outcome. --Approved with minor changes: The dissertation is deemed acceptable subject to minor revisions. The dissertation is corrected by the candidate, taking into account the comments made by the committee. The revisions will be supervised by the primary adviser. Upon completion of the required revision, the candidate is recommended for the degree. --Approved subject to major revision within six months: The dissertation is deemed acceptable subject to major revisions. All revisions must be completed within six months from the date of the dissertation defense. Upon completion of the required revisions, the defense is considered to be successful. The revisions will be supervised by the primary adviser. --Rejected: The dissertation is deemed unacceptable and the candidate is not recommended for the degree. A candidate may be re-examined only once upon recommendation of two readers. Rejection is expected to be very exceptional. A written assessment of the thesis defense will be given to the candidate and filed in the Department by the Chair of the Defense Committee. Candidates should keep in mind the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences deadlines for submission of the thesis and degree application when scheduling the defense.

Submitting the Dissertation

Students ordinarily devote three years to research and writing the dissertation, and complete it prior to seeking full-time employment. The dissertation will be judged according to the highest standards of scholarship, and should be an original contribution to knowledge and understanding of art. The final manuscript must conform to University requirements described in the Supplement The Form of the Doctoral Thesis distributed by the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Graduate students should negotiate with their readers the timing of submission of drafts prior to final revisions. However, the complete manuscript of the dissertation must be submitted to the thesis readers not later than August 1 for a November degree, November 1 for a March degree, and April 1 for a May degree (this in order to provide both the committee with time to read and the candidate to revise, if necessary). The thesis readers may have other expectations regarding dates for submission which should be discussed and handled on an individual basis. The student is still responsible for distribution of the thesis to the committee for reading. In cases where a thesis defense is scheduled, the thesis must be submitted to the primary adviser at least one month prior to the defense. The thesis defense must be scheduled at least two weeks prior to the university deadline for thesis submission.

A written assessment by dissertation readers must be included with the final approval of each thesis including suggestions, as appropriate, on how the dissertation might be adapted for later publication.

The Dissertation is submitted online. The Dissertation Acceptance Certificate (original) must be on Harvard watermark paper and is submitted directly to the registrar’s office once it is signed.

Degree Application and Deadlines

Commencement

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

Published on 26 March 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 5 May 2022.

A dissertation is a large research project undertaken at the end of a degree. It involves in-depth consideration of a problem or question chosen by the student. It is usually the largest (and final) piece of written work produced during a degree.

The length and structure of a dissertation vary widely depending on the level and field of study. However, there are some key questions that can help you understand the requirements and get started on your dissertation project.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

When and why do you have to write a dissertation, who will supervise your dissertation, what type of research will you do, how should your dissertation be structured, what formatting and referencing rules do you have to follow, frequently asked questions about dissertations.

A dissertation, sometimes called a thesis, comes at the end of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree. It is a larger project than the other essays you’ve written, requiring a higher word count and a greater depth of research.

You’ll generally work on your dissertation during the final year of your degree, over a longer period than you would take for a standard essay . For example, the dissertation might be your main focus for the last six months of your degree.

Why is the dissertation important?

The dissertation is a test of your capacity for independent research. You are given a lot of autonomy in writing your dissertation: you come up with your own ideas, conduct your own research, and write and structure the text by yourself.

This means that it is an important preparation for your future, whether you continue in academia or not: it teaches you to manage your own time, generate original ideas, and work independently.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

During the planning and writing of your dissertation, you’ll work with a supervisor from your department. The supervisor’s job is to give you feedback and advice throughout the process.

The dissertation supervisor is often assigned by the department, but you might be allowed to indicate preferences or approach potential supervisors. If so, try to pick someone who is familiar with your chosen topic, whom you get along with on a personal level, and whose feedback you’ve found useful in the past.

How will your supervisor help you?

Your supervisor is there to guide you through the dissertation project, but you’re still working independently. They can give feedback on your ideas, but not come up with ideas for you.

You may need to take the initiative to request an initial meeting with your supervisor. Then you can plan out your future meetings and set reasonable deadlines for things like completion of data collection, a structure outline, a first chapter, a first draft, and so on.

Make sure to prepare in advance for your meetings. Formulate your ideas as fully as you can, and determine where exactly you’re having difficulties so you can ask your supervisor for specific advice.

Your approach to your dissertation will vary depending on your field of study. The first thing to consider is whether you will do empirical research , which involves collecting original data, or non-empirical research , which involves analysing sources.

Empirical dissertations (sciences)

An empirical dissertation focuses on collecting and analysing original data. You’ll usually write this type of dissertation if you are studying a subject in the sciences or social sciences.

- What are airline workers’ attitudes towards the challenges posed for their industry by climate change?

- How effective is cognitive behavioural therapy in treating depression in young adults?

- What are the short-term health effects of switching from smoking cigarettes to e-cigarettes?

There are many different empirical research methods you can use to answer these questions – for example, experiments , observations, surveys , and interviews.

When doing empirical research, you need to consider things like the variables you will investigate, the reliability and validity of your measurements, and your sampling method . The aim is to produce robust, reproducible scientific knowledge.

Non-empirical dissertations (arts and humanities)

A non-empirical dissertation works with existing research or other texts, presenting original analysis, critique and argumentation, but no original data. This approach is typical of arts and humanities subjects.

- What attitudes did commentators in the British press take towards the French Revolution in 1789–1792?

- How do the themes of gender and inheritance intersect in Shakespeare’s Macbeth ?

- How did Plato’s Republic and Thomas More’s Utopia influence nineteenth century utopian socialist thought?

The first steps in this type of dissertation are to decide on your topic and begin collecting your primary and secondary sources .

Primary sources are the direct objects of your research. They give you first-hand evidence about your subject. Examples of primary sources include novels, artworks and historical documents.

Secondary sources provide information that informs your analysis. They describe, interpret, or evaluate information from primary sources. For example, you might consider previous analyses of the novel or author you are working on, or theoretical texts that you plan to apply to your primary sources.

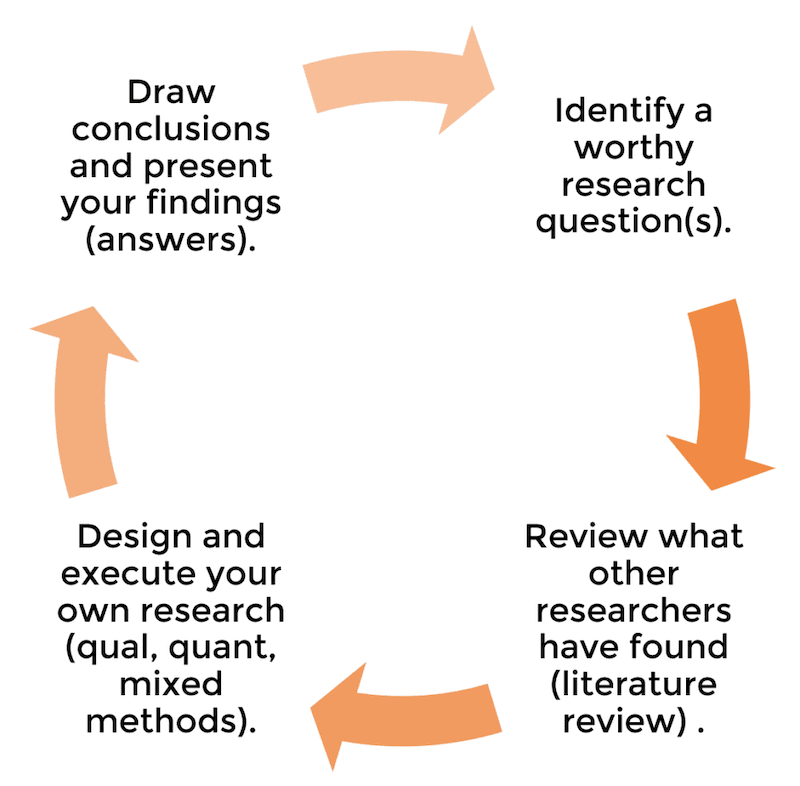

Dissertations are divided into chapters and sections. Empirical dissertations usually follow a standard structure, while non-empirical dissertations are more flexible.

Structure of an empirical dissertation

Empirical dissertations generally include these chapters:

- Introduction : An explanation of your topic and the research question(s) you want to answer.

- Literature review : A survey and evaluation of previous research on your topic.

- Methodology : An explanation of how you collected and analysed your data.

- Results : A brief description of what you found.

- Discussion : Interpretation of what these results reveal.

- Conclusion : Answers to your research question(s) and summary of what your findings contribute to knowledge in your field.

Sometimes the order or naming of chapters might be slightly different, but all of the above information must be included in order to produce thorough, valid scientific research.

Other dissertation structures

If your dissertation doesn’t involve data collection, your structure is more flexible. You can think of it like an extended essay – the text should be logically organised in a way that serves your argument:

- Introduction: An explanation of your topic and the question(s) you want to answer.

- Main body: The development of your analysis, usually divided into 2–4 chapters.

- Conclusion: Answers to your research question(s) and summary of what your analysis contributes to knowledge in your field.

The chapters of the main body can be organised around different themes, time periods, or texts. Below you can see some example structures for dissertations in different subjects.

- Political philosophy

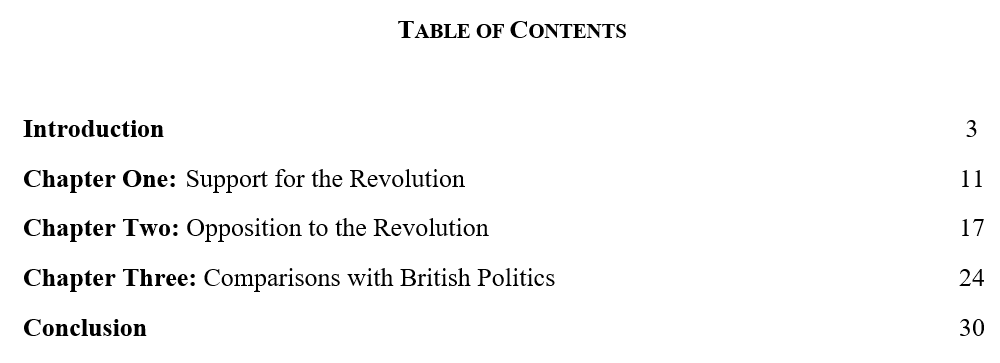

This example, on the topic of the British press’s coverage of the French Revolution, shows how you might structure each chapter around a specific theme.

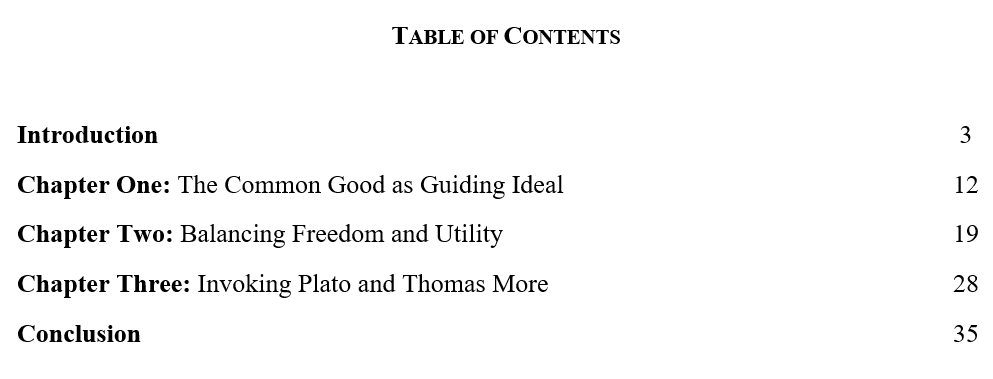

This example, on the topic of Plato’s and More’s influences on utopian socialist thought, shows a different approach to dividing the chapters by theme.

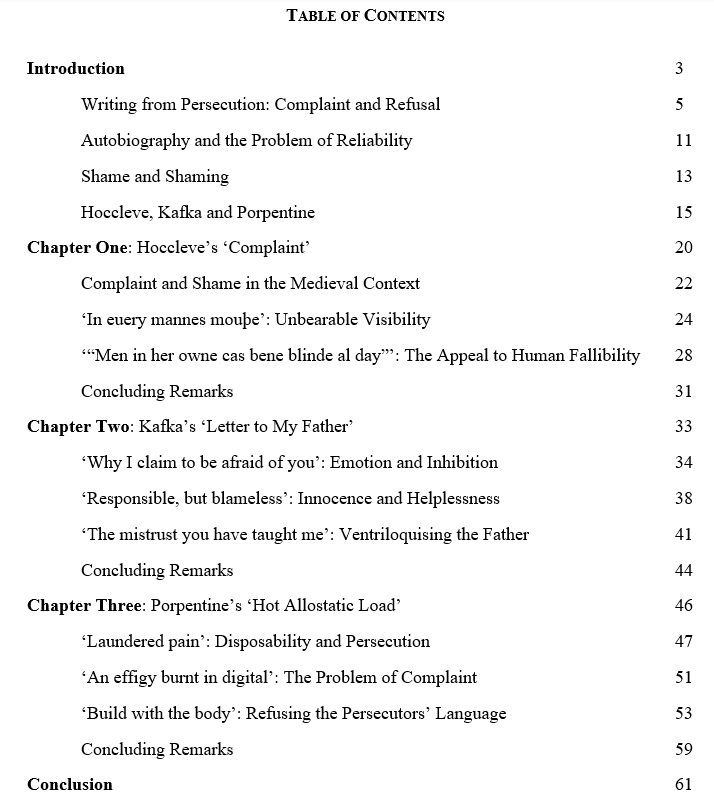

This example, a master’s dissertation on the topic of how writers respond to persecution, shows how you can also use section headings within each chapter. Each of the three chapters deals with a specific text, while the sections are organised thematically.

Like other academic texts, it’s important that your dissertation follows the formatting guidelines set out by your university. You can lose marks unnecessarily over mistakes, so it’s worth taking the time to get all these elements right.

Formatting guidelines concern things like:

- line spacing

- page numbers

- punctuation

- title pages

- presentation of tables and figures

If you’re unsure about the formatting requirements, check with your supervisor or department. You can lose marks unnecessarily over mistakes, so it’s worth taking the time to get all these elements right.

How will you reference your sources?

Referencing means properly listing the sources you cite and refer to in your dissertation, so that the reader can find them. This avoids plagiarism by acknowledging where you’ve used the work of others.

Keep track of everything you read as you prepare your dissertation. The key information to note down for a reference is:

- The publication date

- Page numbers for the parts you refer to (especially when using direct quotes)

Different referencing styles each have their own specific rules for how to reference. The most commonly used styles in UK universities are listed below.

You can use the free APA Reference Generator to automatically create and store your references.

APA Reference Generator

The words ‘ dissertation ’ and ‘thesis’ both refer to a large written research project undertaken to complete a degree, but they are used differently depending on the country:

- In the UK, you write a dissertation at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a thesis to complete a PhD.

- In the US, it’s the other way around: you may write a thesis at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a dissertation to complete a PhD.

The main difference is in terms of scale – a dissertation is usually much longer than the other essays you complete during your degree.

Another key difference is that you are given much more independence when working on a dissertation. You choose your own dissertation topic , and you have to conduct the research and write the dissertation yourself (with some assistance from your supervisor).

Dissertation word counts vary widely across different fields, institutions, and levels of education:

- An undergraduate dissertation is typically 8,000–15,000 words

- A master’s dissertation is typically 12,000–50,000 words

- A PhD thesis is typically book-length: 70,000–100,000 words

However, none of these are strict guidelines – your word count may be lower or higher than the numbers stated here. Always check the guidelines provided by your university to determine how long your own dissertation should be.

At the bachelor’s and master’s levels, the dissertation is usually the main focus of your final year. You might work on it (alongside other classes) for the entirety of the final year, or for the last six months. This includes formulating an idea, doing the research, and writing up.

A PhD thesis takes a longer time, as the thesis is the main focus of the degree. A PhD thesis might be being formulated and worked on for the whole four years of the degree program. The writing process alone can take around 18 months.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, May 05). What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started. Scribbr. Retrieved 25 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/what-is-a-dissertation/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples.

How to Write Your MFA Thesis in Fine Art (And Beyond)

Ryan Seslow

Public Paper Draft

I enjoy writing and I find the process to be fun. Do you? I know that writing takes regular practice and it’s an essential part of my learning process. Writing helps me “see” and organize my thoughts. This allows me to edit and become clear about what it is I am expressing. Practicing my writing helps me identify mistakes (the endless typos..) as well as further emphasize what I really want to explore and write about. When a topic of interest strikes me the process is effortless. I notice how I feel about the topic and this is a key factor as to how quickly I will get working on as essay, blog post or tutorial. This is something I have identified in myself over time and through repetition. Writing induces and activates new awareness. In my experiences as a college art and design professor, I have taken notice of a few consistent patterns when it comes to more formal writing, especially a final thesis deadline. For some, the thought of generating a final graduate thesis can be a daunting thought in and of itself. Associated with that thought may be an outdated feeling that your body still remembers. This outdated association can be especially frustrating to the point of extreme procrastination. If you are unaware that you are the cause of this feeling then you will continue to perpetuate it. Sound familiar? If you choose to enroll into an MFA program you will be required to write a final thesis. This will be an in depth description of your concepts, process, references, discoveries, reflections and final analysis. The best part of writing a final thesis is that the writer gets to create, format, define and structure the entirety of it. Throw away any pre-conceived and or outdated perceptions of what you think you should do. You must take responsibility for your writing the same way that you discipline yourself in the creation and production of your art work.

Where do you begin?

Your final thesis is an official archival record of what you have completed, explored and accomplished throughout the duration of your MFA program. Not only will your thesis be written for yourself, it will prove and back up your convictions, theories, assessments and statements for other people. It should be known that the content in this tutorial could also be applied to other writing needs that may be similar to the MFA thesis structure. An MA thesis or undergraduate BFA thesis can also easily follow this format. By all means, you can share it and remix it.

A regular writing practice must be established. This means, you will need to create a plan for how and when practice will take place. The calendar on your mobile device or the computer that you use will work just fine to remind you of these appointments. Thirty minutes of practice twice a week can work wonders in the installation of a new habit. Are you up for that? Perhaps there is a way to make this decision seem effortless, keep reading.

You can get started right away. Technology in this area is very accessible and helpful. With the use of a blogging platform such as WordPress one can privately or publicly begin their writing practice and archiving process. Even setting up a basic default blog will do just fine. You can always customize and personalize it later. If a blog does not interest you (but I do hope it does) a word processing document will also do just fine. Either way, choosing to wait until your final semester to get started is a really bad idea and poor planning. Are there exceptions to this statement? Of course, and perhaps you will redefine my outlook, and prove me wrong, but until I experience this from someone, let’s make some longer-term plans.

I taught an MFA and MA thesis course between 2012 – 2019 at LIU Post in NY (but this format transcends into my CUNY courses as well) that put an emphasis on content and exposure to help students generate their final thesis. The course revolved around several exercises that contributed to the process as a whole. They were broken down into individual isolated parts for deeper focus. Much like your thesis itself, this process is modular, meaning, many parts will come and work together to make up the whole. One of the first exercises that we do with the class is identify a thesis template format. This is the basic structure that I have students brainstorm via a series of questions that I ask them. Keep in mind; you most likely already have a default version of this template. This could be the writing format that you learned in high school and had redefined by a professor in college. You may have been forced to use it or suffer the consequences of a poor grade solely on that formatting restriction. This feeling and program may still be running inside you. So how do we deal with this? Together as a class we discuss and record the answers directly onto a dry erase board (or word document will also do just fine) I ask one of the students to act as the scribe to record the list manually while notes are also individually taken. I later put the information into a re-capped blog post for our class blog. Are you surprised that I use a blog for my class?

The Format-

The format for an MFA thesis in Fine Art (applied arts & digital) will in almost all cases coincide with a final thesis exhibition of completed works. This formats fits accordingly with the thesis exhibition in mind. This is a criteria break down of the structure of the paper. It is a simplified guide. Add or remove what you may for your personal needs.

- Description/Abstract: Introduction. A detailed description of the concept and body of work that you will be discussing. Be clear and objective, you need not tell your whole life story here. Fragments of your current artist statement may fit in nicely.

- Process, Materials and Methods: Here you will discuss the descriptions of your working processes, techniques learned and applied, and the materials used to generate the art that you create. Why have you selected these specific materials and techniques to communicate your ideas? How do these choices effect how the viewer will receive your work? Have you personalized a technique in a new way? How so? Were their limitations and new discoveries?

- Resources and References: Historical and cultural referencing, artists, art movements, databases, and any other form of related influence. How has your research influenced your work, ideas, and decision-making process? What contrasts and contradictions have you discovered about your work and ideas? How has regular research and exposure during your program inspired you? Have you made direct and specific connections to an art movement or a series of artists? Explain your discoveries and how you came to those conclusions.

- Exhibition Simulation: You will be mounting a final thesis exhibition of your work. How will you be mounting your exhibition? Why have you selected this particular composition? How did the space itself dictate your choices for installation? How will your installation effect or alter the physical space itself? Will you generate a floor plan sketch to accompany the proposed composition? If so, please explain, if not, also explain why? What kind of help will you need to realize the installation? What materials will you be using to install? Do you have special requirements for ladders, technologies and additional help? Explain in detail.

- Reflection: What have you learned over the course of your graduate program? How has the program influenced your work and how you communicate as an artist? What were your greatest successes? What areas do you need to work on? What skills will you apply directly into your continued professional practice? Do you plan to teach after you graduate? If so, what philosophies and theories will you apply into your teaching practice? Where do you see your self professionally as an artist in 3-5 years?

Individual Exercises to Practice-

The following exercises below were created to help practice and expand thinking about the thesis format criteria above. It is my intention to help my students actively contribute to their thesis over the course of the semester. The exercises can be personalized and expanded upon for your individual needs. I feel that weekly exercises performed with a class or one on one with a partner will work well. The weekly meetings in person are effective. Why? Having a classroom or person-to-person(s) platform for discussion allows for the energy of the body to expose itself. You (and most likely your audience) will take notice as to how you feel when you are discussing the ideas, feelings and concepts that you have written. Are you upbeat and positively charged? Or are you just “matter of fact” and lifeless in your verbal assertions? Writing and speaking should be engaging. Especially if it is about your work! The goal is to entice your reader and audience to feel your convictions and transcend those feelings directly. Awareness of this is huge. It will help you make not only edits in your writing but also make changes in your speaking and how you feel about what you have written.

- The Artist Interview – Reach out to a classmate or an artist that you admire. This could also be a professor, faculty member, or fellow classmate. It should be one that you feel also admires or has interest in your work if possible. Make appointments to visit each other in their studios or where ever you are creating current work. This can even be done via video chat if in person visits cannot be made. In advance prepare for each other a series of 15-20 questions that you would like to ask each other. Questions can be about the artist’s concepts, materials, process, resources and references about their works. Questions may be about how they choose to show or sell their work. Personal questions about the artist’s outlook on life, business, and wellbeing may come to mind and may also be considered. Record and exchange each other’s responses in a written format. You will make a copy for yourself to retain. Re-read and study your responses to the questions that the artist asked you. This will be helpful for you to read your spoken words coming from another format of communication. Do you find that you speak the same way that you write? Where do these words fit into the thesis criteria format above?

- The Artist Statement & Manifesto – Of course this will change and evolve over time but it is a necessary document that you will update each year as you evolve and grow. In one single page generate your artist statement or manifesto. Who are you? What is your work about? What are you communicating with your current work, projects and why? Who is your audience? How is your work affecting your audience, community and culture? Manifestos are usually published and placed into the public so that its creator can live up to its statements. Are you living up to yours? Keeping this public is a good reminder to walk your talk. Where do these words fit into the thesis criteria format above?

- Reactive Writing – Create a regular online space, document or journal to generate a chronological folio of reactive writing. Visit museums, galleries, lectures and screenings regularly. If you live outside of a city this may require a bit of research, but if you are in NYC this is all too easy. Bring a sketchbook and take notes! For each experience share your impressions, thoughts, feelings and reactions. Describe what you witness. Be objective down to the smallest details that have stayed with you. Reflect and find similarities and contrasts to what you are working on. Use this exercise as a free writing opportunity. Write with out editing or with out any formatting restrains, just express yourself in the immediacy that you feel about your experiences. At the end of each month (or designate a class for this aspect of the exercise) sit down and re-read your passages. Select the reaction(s) that you resonate with the most. Edit and format this selection into a more formal essay paying proper attention to a formatting style, grammar, punctuation and spelling. Where do these words fit into the thesis criteria format above?

- Tutorials & How To Guides – Writing tutorials and how-to guides are great ways to practice getting really clear about what you are doing. It helps you cultivate your vocabulary and describe the actions that you are performing with specific detail. It puts you in a position to list your steps, process, materials, and references and explain what the contributing contextual aspects are. Try this with a specific project or with the art that you are currently creating. Are you painter? Explain how you create a painting from start to finish. This includes the very first spark that inspires the idea for the painting, as well as how it will be installed, packaged, transported and exhibited. Details matter. Are you sculptor working in woodcarving? Explain the process from start to finish. Ask a fellow artist if you can sit in on his or her process and record what you experience. This is a really fantastic and fun exercise. It also contributes greatly to creating lesson plans for teaching. (I’m actually obsessed with this exercise a little bit.) Where do these words fit into the thesis criteria format above?

- Reviews & Critiques – Much like the reactive writing exercise above, generating reviews and critiques will foster great ways to find insight into your own work. With regular practice you will find common threads of thought and subject matter. You will discover similar referencing and contrasts. This can easily be done in two ways. You can visit specific museums, galleries, lectures and screenings to write about that excites you. This already puts a positive charge on the act of writing itself. I also suggest that you contrast this with subject matter and content that also does not agree with you. We want to be able to fully express what we do not like as well. Understanding why helps us become clear in our choices. Understanding this helps strengthen our position on what we do want to write about and what we want our audience to understand. It allows us to explore dichotomies. The second way to further exercises in writing reviews and critiques is to speak about them. Speaking about art in person is a great way to further the clarification of your writing. Where do these words fit into the thesis criteria format above?

Further Experimentation-

The spoken word versus the act of writing? I have come across many students and colleagues who find that they write much differently than they speak. I feel that writing needs to have a consistent flow and feel fluid to keep its reader engaged. Speaking well and articulating oneself clearly is also something that takes practice. I have found that sometimes recording my words and thoughts via a voice transcribing application is helpful to get ideas out and into a more accessible form. A lot of transcribing software is free for most mobile devices. Much like voice recording the powerful enhancement is to see your words take form after you have said them. You can simply copy and paste the text and edit what is valuable.

This essay is also a work in progress. It’s an ongoing draft in a published format that I will continue updating with new content and fresh ways to simplify the exercises.

I appreciate your feedback!

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pamm [missing word] 1. Artist Interview- Do you find that (you) speak the same way that you write? July 15, 2018 at 1:38 pm Reply

- Ryan Seslow Hi Marilyn! I see you! So weird, this is the first comment that has appeared on the paper. I have gotten several e-mails about past comments but still cant see where those are, lol! :)) September 18, 2018 at 1:05 pm Reply

Need help with the Commons?

Email us at [email protected] so we can respond to your questions and requests. Please email from your CUNY email address if possible. Or visit our help site for more information:

Welcome to Social Paper (beta) !

- About Social Paper

- Social Paper (beta)

Department of the History of Art

You are here, dissertations, completed dissertations.

1942-present

DISSERTATIONS IN PROGRESS

As of July 2023

Bartunkova, Barbora , “Sites of Resistance: Antifascism and the Czechoslovak Avant-garde” (C. Armstrong)

Betik, Blair Katherine , “Alternate Experiences: Evaluating Lived Religious Life in the Roman Provinces in the 1st Through 4th Centuries CE” (M. Gaifman)

Boyd, Nicole , “Science, Craft, Art, Theater: Four ‘Perspectives’ on the Painted Architecture of Angelo Michele Colonna and Agostino Mitelli” (N. Suthor).

Brown, Justin , “Afro-Surinamese Calabash Art in the Era of Slavery and Emancipation” (C. Fromont)

Burke, Harry , “The Islands Between: Art, Animism, and Anticolonial Worldmaking in Archipelagic Southeast Asia” (P. Lee)

Chakravorty, Swagato , “Displaced Cinema: Moving Images and the Politics of Location in Contemporary Art” (C. Buckley, F. Casetti)

Chau, Tung , “Strange New Worlds: Interfaces in the Work of Cao Fei” (P. Lee)

Cox, Emily , “Perverse Modernism, 1884-1990” (C. Armstrong, T. Barringer)

Coyle, Alexander , “Frame and Format between Byzantium and Central Italy, 1200-1300” (R. Nelson)

Datta, Yagnaseni , “Materialising Illusions: Visual Translation in the Mughal Jug Basisht, c. 1602.” (K. Rizvi)

de Luca, Theo , “Nicolas Poussin’s Chronotopes” (N. Suthor)

Dechant, D. Lyle . ” ‘daz wir ein ander vinden fro’: Readers and Performers of the Codex Manesse” (J. Jung)

Del Bonis-O’Donnell, Asia, “Trees and the Visualization of kosmos in Archaic and Classical Athenian Art” (M. Gaifman)

Demby, Nicole, “The Diplomatic Image: Framing Art and Internationalism, 1945-1960” (K. Mercer)

Donnelly, Michelle , “Spatialized Impressions: American Printmaking Outside the Workshop, 1935–1975” (J. Raab)

Epifano, Angie , “Building the Samorian State: Material Culture, Architecture, and Cities across West Africa” (C. Fromont)

Fialho, Alex , “Apertures onto AIDS: African American Photography and the Art History of the Storage Unit” (P. Lee, T Nyong’o)

Foo, Adela , “Crafting the Aq Qoyuniu Court (1475-1490) (E. Cooke, Jr.)

Franciosi, Caterina , “Latent Light: Energy and Nineteenth-Century British Art” (T. Barringer)

Frier, Sara , “Unbearable Witness: The Disfigured Body in the Northern European Brief (1500-1620)” (N. Suthor)

Gambert-Jouan, Anabelle , “Sculpture in Place: Medieval Wood Depositions and Their Environments” (J. Jung)

Gass, Izabel, “Painted Thanatologies: Théodore Géricault Against the Aesthetics of Life” (C. Armstrong)

Gaudet, Manon , “Property and the Contested Ground of North American Visual Culture, 1900-1945” (E. Cooke, Jr.)

Haffner, Michaela , “Nature Cure: ”White Wellness” and the Visual Culture of Natural Health, 1870-1930” (J. Raab)

Hepburn, Victoria , “William Bell Scott’s Progress” (T. Barringer)

Herrmann, Mitchell, “The Art of the Living: Biological Life and Aesthetic Experience in the 21st Century” (P. Lee)

Higgins, Lily , “Reading into Things: Articulate Objects in Colonial North America, 1650-1783” (E. Cooke, Jr.)

Hodson, Josie , “Something in Common: Black Art under Austerity in New York City, 1975-1990” (Yale University, P. Lee)

Hong, Kevin , “Plasticity, Fungibility, Toxicity: Photography’s Ecological Entanglements in the Mid-Twentieth-Century United States” (C. Armstrong, J Raab)

Kang, Mia , “Art, Race, Representation: The Rise of Multiculturalism in the Visual Arts” (K. Mercer)

Keto, Elizabeth , “Remaking the World: United States Art in the Reconstruction Era, 1861-1900.” (J. Raab)

Kim, Adela , “Beyond Institutional Critique: Tearing Up in the Work of Andrea Fraser” (P. Lee)

Koposova, Ekaterina , “Triumph and Terror in the Arts of the Franco-Dutch War” (M. Bass)

Lee, Key Jo , “Melancholic Materiality: History and the Unhealable Wound in African American Photographic Portraits, 1850-1877” (K. Mercer)

Levy Haskell, Gavriella , “The Imaginative Painter”: Visual Narrative and the Interactive Painting in Britain, 1851-1914” (T. Barringer, E. Cooke Jr)

Marquardt, Savannah, “Becoming a Body: Lucanian Painted Vases and Grave Assemblages in Southern Italy” (M. Gaifman)

Miraval, Nathalie , “The Art of Magic: Afro-Catholic Visual Culture in the Early Modern Spanish Empire” (C. Fromont)

Mizbani, Sharon , Water and Memory: Fountains, Heritage, and Infrastructure in Istanbul and Tehran (1839-1950) (K. Rizvi)

Molarsky-Beck, Marina, “Seeing the Unseen: Queer Artistic Subjectivity in Interwar Photography” (C. Armstrong)

Nagy, Renata , “Bookish Art: Natural Historical Learning Across Media in Seventeenth-century Northern Europe” (Bass, M)

Olson, Christine , “Owen Jones and the Epistemologies of Nineteenth-Century Design” (T. Barringer)

Petrilli-Jones, Sara , “Drafting the Canon: Legal Histories of Art in Florence and Rome, 1600-1800” (N. Suthor)

Phillips, Kate , “American Ephemera” (J. Raab)

Potuckova, Kristina , “The Arts of Women’s Monastic Liturgy, Holy Roman Empire, 1000-1200” (J. Jung)

Quack, Gregor , “The Social Fabric: Franz Erhard Walther’s Art in Postwar Germany” (P. Lee)

Rahimi-Golkhandan, Shabnam , “The Photograph’s Shabih-Kashi (Verisimilitude) – The Liminal Visualities of Late Qajar Art (1853-1911)” (K. Rizvi)

Rapoport, Sarah , “James Jacques Joseph Tissot in the Interstices of Modernity” (T. Barringer, C. Armstrong)

Riordan, Lindsay , “Beuys, Terror, Value: 1967-1979” (S. Zeidler)

Robbins, Isabella , “Relationality and Being: Indigeneity, Space and Transit in Global Contemporary Art” (P. Lee, N. Blackhawk)

Sen, Pooja , “The World Builders ” (J. Peters)

Sellati, Lillian , “When is Herakles Not Himself? Mediating Cultural Plurality in Greater Central Asia, 330 BCE – 365 CE” (M. Gaifman)

Tang, Jenny , “Genealogies of Confinement: Carceral Logics of Visuality in Atlantic Modernism 1930 – 1945” (K. Mercer)

Thomas, Alexandra , “Afrekete’s Touch: Black Queer Feminist Errantry and Global African Art” (P. Lee)

Valladares, Carlos , “Jacques Demy” (P. Lee)

Verrot, Trevor , “Sculpted Lamentation Groups in the Late Medieval Veneto” (J. Jung)

Von-Ow, Pierre , Visual Tactics: Histories of Perspective in Britain and its Empire, 1670-1768.” (T. Barringer)

Wang, Xueli , “Performing Disappearance: Maggie Cheung and the Off-Screen” (Q. Ngan)

Webley, John , “Ink, Paint, and Blood: India and the Great Game in Russian Culture” (T. Barringer, M. Brunson)

Werwie, Katherine , “Visions Across the Gates: Materiality, Symbolism, and Communication in the Historiated Wooden Doors of Medieval European Churches” (J. Jung)

Wisowaty, Stephanie , “Painted Processional Crosses in Central Italy, 1250-1400: Movement, Mediation and Multisensory Effects” (J. Jung)

Young, Colin , “Desert Places: The Visual Culture of the Prairies and the Pampas across the Nineteenth Century” (J. Raab)

Zhou, Joyce Yusi, “Objects by Her Hand: Art and Material Culture of Women in Early Modern Batavia (1619-1799) (M. Bass, E. Cooke, Jr.)

- Art Degrees

- Galleries & Exhibits

- Request More Info

Art History Resources

- Guidelines for Analysis of Art

- Formal Analysis Paper Examples

Guidelines for Writing Art History Research Papers

- Oral Report Guidelines

- Annual Arkansas College Art History Symposium

Writing a paper for an art history course is similar to the analytical, research-based papers that you may have written in English literature courses or history courses. Although art historical research and writing does include the analysis of written documents, there are distinctive differences between art history writing and other disciplines because the primary documents are works of art. A key reference guide for researching and analyzing works of art and for writing art history papers is the 10th edition (or later) of Sylvan Barnet’s work, A Short Guide to Writing about Art . Barnet directs students through the steps of thinking about a research topic, collecting information, and then writing and documenting a paper.

A website with helpful tips for writing art history papers is posted by the University of North Carolina.

Wesleyan University Writing Center has a useful guide for finding online writing resources.

The following are basic guidelines that you must use when documenting research papers for any art history class at UA Little Rock. Solid, thoughtful research and correct documentation of the sources used in this research (i.e., footnotes/endnotes, bibliography, and illustrations**) are essential. Additionally, these guidelines remind students about plagiarism, a serious academic offense.

Paper Format

Research papers should be in a 12-point font, double-spaced. Ample margins should be left for the instructor’s comments. All margins should be one inch to allow for comments. Number all pages. The cover sheet for the paper should include the following information: title of paper, your name, course title and number, course instructor, and date paper is submitted. A simple presentation of a paper is sufficient. Staple the pages together at the upper left or put them in a simple three-ring folder or binder. Do not put individual pages in plastic sleeves.

Documentation of Resources

The Chicago Manual of Style (CMS), as described in the most recent edition of Sylvan Barnet’s A Short Guide to Writing about Art is the department standard. Although you may have used MLA style for English papers or other disciplines, the Chicago Style is required for all students taking art history courses at UA Little Rock. There are significant differences between MLA style and Chicago Style. A “Quick Guide” for the Chicago Manual of Style footnote and bibliography format is found http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html. The footnote examples are numbered and the bibliography example is last. Please note that the place of publication and the publisher are enclosed in parentheses in the footnote, but they are not in parentheses in the bibliography. Examples of CMS for some types of note and bibliography references are given below in this Guideline. Arabic numbers are used for footnotes. Some word processing programs may have Roman numerals as a choice, but the standard is Arabic numbers. The use of super script numbers, as given in examples below, is the standard in UA Little Rock art history papers.

The chapter “Manuscript Form” in the Barnet book (10th edition or later) provides models for the correct forms for footnotes/endnotes and the bibliography. For example, the note form for the FIRST REFERENCE to a book with a single author is:

1 Bruce Cole, Italian Art 1250-1550 (New York: New York University Press, 1971), 134.

But the BIBLIOGRAPHIC FORM for that same book is:

Cole, Bruce. Italian Art 1250-1550. New York: New York University Press. 1971.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in a footnote is:

2 Anne H. Van Buren, “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits,” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 199.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in the BIBLIOGRAPHY is:

Van Buren, Anne H. “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits.” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 185-204.

If you reference an article that you found through an electronic database such as JSTOR, you do not include the url for JSTOR or the date accessed in either the footnote or the bibliography. This is because the article is one that was originally printed in a hard-copy journal; what you located through JSTOR is simply a copy of printed pages. Your citation follows the same format for an article in a bound volume that you may have pulled from the library shelves. If, however, you use an article that originally was in an electronic format and is available only on-line, then follow the “non-print” forms listed below.

B. Non-Print

Citations for Internet sources such as online journals or scholarly web sites should follow the form described in Barnet’s chapter, “Writing a Research Paper.” For example, the footnote or endnote reference given by Barnet for a web site is:

3 Nigel Strudwick, Egyptology Resources , with the assistance of The Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Cambridge University, 1994, revised 16 June 2008, http://www.newton.ac.uk/egypt/ , 24 July 2008.

If you use microform or microfilm resources, consult the most recent edition of Kate Turabian, A Manual of Term Paper, Theses and Dissertations. A copy of Turabian is available at the reference desk in the main library.

C. Visual Documentation (Illustrations)

Art history papers require visual documentation such as photographs, photocopies, or scanned images of the art works you discuss. In the chapter “Manuscript Form” in A Short Guide to Writing about Art, Barnet explains how to identify illustrations or “figures” in the text of your paper and how to caption the visual material. Each photograph, photocopy, or scanned image should appear on a single sheet of paper unless two images and their captions will fit on a single sheet of paper with one inch margins on all sides. Note also that the title of a work of art is always italicized. Within the text, the reference to the illustration is enclosed in parentheses and placed at the end of the sentence. A period for the sentence comes after the parenthetical reference to the illustration. For UA Little Rcok art history papers, illustrations are placed at the end of the paper, not within the text. Illustration are not supplied as a Powerpoint presentation or as separate .jpgs submitted in an electronic format.

Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream, dated 1893, represents a highly personal, expressive response to an experience the artist had while walking one evening (Figure 1).

The caption that accompanies the illustration at the end of the paper would read:

Figure 1. Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893. Tempera and casein on cardboard, 36 x 29″ (91.3 x 73.7 cm). Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, Norway.

Plagiarism is a form of thievery and is illegal. According to Webster’s New World Dictionary, to plagiarize is to “take and pass off as one’s own the ideas, writings, etc. of another.” Barnet has some useful guidelines for acknowledging sources in his chapter “Manuscript Form;” review them so that you will not be mguilty of theft. Another useful website regarding plagiarism is provided by Cornell University, http://plagiarism.arts.cornell.edu/tutorial/index.cfm

Plagiarism is a serious offense, and students should understand that checking papers for plagiarized content is easy to do with Internet resources. Plagiarism will be reported as academic dishonesty to the Dean of Students; see Section VI of the Student Handbook which cites plagiarism as a specific violation. Take care that you fully and accurately acknowledge the source of another author, whether you are quoting the material verbatim or paraphrasing. Borrowing the idea of another author by merely changing some or even all of your source’s words does not allow you to claim the ideas as your own. You must credit both direct quotes and your paraphrases. Again, Barnet’s chapter “Manuscript Form” sets out clear guidelines for avoiding plagiarism.

VISIT OUR GALLERIES SEE UPCOMING EXHIBITS

- School of Art and Design

- Windgate Center of Art + Design, Room 202 2801 S University Avenue Little Rock , AR 72204

- Phone: 501-916-3182 Fax: 501-683-7022 (fax)

- More contact information

Connect With Us

UA Little Rock is an accredited member of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design.

- How to format a science disertation

- Where to buy a thesis paper

- Structural engineering dissertation

- Creating a literature review

- Who can do my thesis?

- Writing on psychology of management

- Turning to a dissertation editing agency

- History thesis conclusion sample

- Linguistics dissertation writing guide

- Paying for a quality thesis

- Top tips for buying a dissertation

- Looking for a qualified writer

- Hiring a dissertation service

- Getting academic writing assistance

- Writing on bank bankruptcy

- Thesis paper proposal in nursing

- Instructions for completing a conclusion

- Composing an informatics dissertation

- Creating an abstract related to law

- Aims & objectives

- Postgraduate thesis in physics

- Real estate management thesis proposal

- Philosophy dissertation introduction

- Getting a Harvard style thesis sample

- Industrial engineering Master's thesis

- Getting a dissertation bibliography sample

- Completing an English literature thesis

- Art history thesis methods section

- Acknowledgements in the Turabian style

- Law dissertation body part

- Getting a defense presentation sample

- Completing a thesis about bullying

- Writing on psychiatric nursing

- Thesis topics on management

- Finding a skilled thesis writer

- Environmental science

- Film studies

- Linguistics

- Special education

- Clinical psychology

- German literature

- Ancient Greece

- Education leadership

- Health-care risk management

- Digital marketing

- Developmental psychology

- South Africa

- Anaesthesiology

- Social media

- Academic anxiety

- Events management

- Airline industry

- Graphic design

- Nuclear engineering

- Finance & banking

- Data mining

- Introduction

Art History Dissertation Methodology: 7 Things To Keep In Mind

The methodology section for an art history dissertation is shorter compared to counterparts in the sciences, but it’s still an integral part of the graduate project that requires your undivided attention. As it will likely be based on non-empirical information taken from literature that has already been published in the field, there are some really important things you need to keep in mind when writing it:

- Determine the appropriate methodology to employ

Art historians can use any of a number of methodologies to conduct their research study (e.g., chronological, logical, iconographical, critical analysis, etc.) so it’s important that you first identify the appropriate methodology and that you fully understand how you must frame your study within it.

- Make sure you address your advisor’s requests

If you are having any doubts about which methodology to use then you might benefit from brainstorming some ideas with your graduate advisor. Even though this is your personal academic study, it still must meet certain criteria. Discuss this to find out exactly what is expected from you by the committee.

- Provide a simple step by step explanation of approach

Don’t merely define the methodology you plan on using in your work; you should provide a step by step explanation of why you chose the approach as well as how you plan on going about conducting it. Remember to keep your personal opinions or findings out of this section. The content within should be straightforward.

- Don’t introduce complex approaches in methodologies

One of the things that trip students up is when they begin to introduce complex approaches in their methodologies. This can be both confusing to the reader and to you. The best approach is to think about the simplest method for finding something out and arriving to some definitive conclusion.

- Set your work aside for a few days before revising

The process of revision is very important in high academic writing. If you don’t give yourself plenty of time to revise you might not be taking full advantage of an exercise where the main purpose is to make your argument and presentation stronger. Start this with a clear mindset to reap all of its benefits.

- Thoroughly edit and Proofread the entire section

This piece of advice really does apply to every section and all types of written assignments. Edit for sentence and word clarity. Complex structures or multi-syllabic words can be confusing and much more difficult to understand. Also, make sure you have corrected all errors in grammar, punctuation and spelling. A document that is filled with errors will be poorly received.

- Always have a fresh set of eyes critique the section

You should constantly remind yourself that you want to keep your work interesting and understandable. Even though it will be reviewed by experts in the field, your work should be written and structured so that a person outside the field could also enjoy.

- Creating a Master's dissertation

- How to cite a Chicago thesis paper

- Hiring dissertation writers

- Dissertation in HR management

- Graduate thesis example online

- Doctoral physiology thesis abstract

- Writing on the Spanish Civil war

- How to recognize a reliable agency?

- Completing a biology dissertation

- International business thesis proposal

Useful sites

Get professional thesis writing and editing services at ThesisGeek - 24/7 online support.

2012-2024. idarts.org. All rights reserved. Updated: 03/25/2024

- Formatting Your Dissertation

- Introduction

Harvard Griffin GSAS strives to provide students with timely, accurate, and clear information. If you need help understanding a specific policy, please contact the office that administers that policy.

- Application for Degree

- Credit for Completed Graduate Work

- Ad Hoc Degree Programs

- Acknowledging the Work of Others

- Advanced Planning

- Dissertation Submission Checklist

- Publishing Options

- Submitting Your Dissertation

- English Language Proficiency

- PhD Program Requirements

- Secondary Fields

- Year of Graduate Study (G-Year)

- Master's Degrees

- Grade and Examination Requirements

- Conduct and Safety

- Financial Aid

- Non-Resident Students

- Registration

On this page:

Language of the Dissertation

Page and text requirements, body of text, tables, figures, and captions, dissertation acceptance certificate, copyright statement.

- Table of Contents

Front and Back Matter

Supplemental material, dissertations comprising previously published works, top ten formatting errors, further questions.

- Related Contacts and Forms

When preparing the dissertation for submission, students must follow strict formatting requirements. Any deviation from these requirements may lead to rejection of the dissertation and delay in the conferral of the degree.

The language of the dissertation is ordinarily English, although some departments whose subject matter involves foreign languages may accept a dissertation written in a language other than English.

Most dissertations are 100 to 300 pages in length. All dissertations should be divided into appropriate sections, and long dissertations may need chapters, main divisions, and subdivisions.

- 8½ x 11 inches, unless a musical score is included

- At least 1 inch for all margins

- Body of text: double spacing

- Block quotations, footnotes, and bibliographies: single spacing within each entry but double spacing between each entry

- Table of contents, list of tables, list of figures or illustrations, and lengthy tables: single spacing may be used

Fonts and Point Size

Use 10-12 point size. Fonts must be embedded in the PDF file to ensure all characters display correctly.

Recommended Fonts

If you are unsure whether your chosen font will display correctly, use one of the following fonts:

If fonts are not embedded, non-English characters may not appear as intended. Fonts embedded improperly will be published to DASH as-is. It is the student’s responsibility to make sure that fonts are embedded properly prior to submission.

Instructions for Embedding Fonts

To embed your fonts in recent versions of Word, follow these instructions from Microsoft:

- Click the File tab and then click Options .

- In the left column, select the Save tab.

- Clear the Do not embed common system fonts check box.

For reference, below are some instructions from ProQuest UMI for embedding fonts in older file formats:

To embed your fonts in Microsoft Word 2010:

- In the File pull-down menu click on Options .

- Choose Save on the left sidebar.

- Check the box next to Embed fonts in the file.

- Click the OK button.

- Save the document.

Note that when saving as a PDF, make sure to go to “more options” and save as “PDF/A compliant”

To embed your fonts in Microsoft Word 2007:

- Click the circular Office button in the upper left corner of Microsoft Word.

- A new window will display. In the bottom right corner select Word Options .

- Choose Save from the left sidebar.

Using Microsoft Word on a Mac:

Microsoft Word 2008 on a Mac OS X computer will automatically embed your fonts while converting your document to a PDF file.

If you are converting to PDF using Acrobat Professional (instructions courtesy of the Graduate Thesis Office at Iowa State University):

- Open your document in Microsoft Word.

- Click on the Adobe PDF tab at the top. Select "Change Conversion Settings."

- Click on Advanced Settings.

- Click on the Fonts folder on the left side of the new window. In the lower box on the right, delete any fonts that appear in the "Never Embed" box. Then click "OK."

- If prompted to save these new settings, save them as "Embed all fonts."

- Now the Change Conversion Settings window should show "embed all fonts" in the Conversion Settings drop-down list and it should be selected. Click "OK" again.

- Click on the Adobe PDF link at the top again. This time select Convert to Adobe PDF. Depending on the size of your document and the speed of your computer, this process can take 1-15 minutes.

- After your document is converted, select the "File" tab at the top of the page. Then select "Document Properties."

- Click on the "Fonts" tab. Carefully check all of your fonts. They should all show "(Embedded Subset)" after the font name.

- If you see "(Embedded Subset)" after all fonts, you have succeeded.

The font used in the body of the text must also be used in headers, page numbers, and footnotes. Exceptions are made only for tables and figures created with different software and inserted into the document.

Tables and figures must be placed as close as possible to their first mention in the text. They may be placed on a page with no text above or below, or they may be placed directly into the text. If a table or a figure is alone on a page (with no narrative), it should be centered within the margins on the page. Tables may take up more than one page as long as they obey all rules about margins. Tables and figures referred to in the text may not be placed at the end of the chapter or at the end of the dissertation.

- Given the standards of the discipline, dissertations in the Department of History of Art and Architecture and the Department of Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Planning often place illustrations at the end of the dissertation.

Figure and table numbering must be continuous throughout the dissertation or by chapter (e.g., 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.2, etc.). Two figures or tables cannot be designated with the same number. If you have repeating images that you need to cite more than once, label them with their number and A, B, etc.

Headings should be placed at the top of tables. While no specific rules for the format of table headings and figure captions are required, a consistent format must be used throughout the dissertation (contact your department for style manuals appropriate to the field).

Captions should appear at the bottom of any figures. If the figure takes up the entire page, the caption should be placed alone on the preceding page, centered vertically and horizontally within the margins.

Each page receives a separate page number. When a figure or table title is on a preceding page, the second and subsequent pages of the figure or table should say, for example, “Figure 5 (Continued).” In such an instance, the list of figures or tables will list the page number containing the title. The word “figure” should be written in full (not abbreviated), and the “F” should be capitalized (e.g., Figure 5). In instances where the caption continues on a second page, the “(Continued)” notation should appear on the second and any subsequent page. The figure/table and the caption are viewed as one entity and the numbering should show correlation between all pages. Each page must include a header.

Landscape orientation figures and tables must be positioned correctly and bound at the top so that the top of the figure or table will be at the left margin. Figure and table headings/captions are placed with the same orientation as the figure or table when on the same page. When on a separate page, headings/captions are always placed in portrait orientation, regardless of the orientation of the figure or table. Page numbers are always placed as if the figure were vertical on the page.

If a graphic artist does the figures, Harvard Griffin GSAS will accept lettering done by the artist only within the figure. Figures done with software are acceptable if the figures are clear and legible. Legends and titles done by the same process as the figures will be accepted if they too are clear, legible, and run at least 10 or 12 characters per inch. Otherwise, legends and captions should be printed with the same font used in the text.

Original illustrations, photographs, and fine arts prints may be scanned and included, centered between the margins on a page with no text above or below.

Use of Third-Party Content

In addition to the student's own writing, dissertations often contain third-party content or in-copyright content owned by parties other than you, the student who authored the dissertation. The Office for Scholarly Communication recommends consulting the information below about fair use, which allows individuals to use in-copyright content, on a limited basis and for specific purposes, without seeking permission from copyright holders.

Because your dissertation will be made available for online distribution through DASH , Harvard's open-access repository, it is important that any third-party content in it may be made available in this way.

Fair Use and Copyright

What is fair use?

Fair use is a provision in copyright law that allows the use of a certain amount of copyrighted material without seeking permission. Fair use is format- and media-agnostic. This means fair use may apply to images (including photographs, illustrations, and paintings), quoting at length from literature, videos, and music regardless of the format.

How do I determine whether my use of an image or other third-party content in my dissertation is fair use?

There are four factors you will need to consider when making a fair use claim.

1) For what purpose is your work going to be used?

- Nonprofit, educational, scholarly, or research use favors fair use. Commercial, non-educational uses, often do not favor fair use.

- A transformative use (repurposing or recontextualizing the in-copyright material) favors fair use. Examining, analyzing, and explicating the material in a meaningful way, so as to enhance a reader's understanding, strengthens your fair use argument. In other words, can you make the point in the thesis without using, for instance, an in-copyright image? Is that image necessary to your dissertation? If not, perhaps, for copyright reasons, you should not include the image.

2) What is the nature of the work to be used?

- Published, fact-based content favors fair use and includes scholarly analysis in published academic venues.

- Creative works, including artistic images, are afforded more protection under copyright, and depending on your use in light of the other factors, may be less likely to favor fair use; however, this does not preclude considerations of fair use for creative content altogether.

3) How much of the work is going to be used?

- Small, or less significant, amounts favor fair use. A good rule of thumb is to use only as much of the in-copyright content as necessary to serve your purpose. Can you use a thumbnail rather than a full-resolution image? Can you use a black-and-white photo instead of color? Can you quote select passages instead of including several pages of the content? These simple changes bolster your fair use of the material.

4) What potential effect on the market for that work may your use have?

- If there is a market for licensing this exact use or type of educational material, then this weighs against fair use. If however, there would likely be no effect on the potential commercial market, or if it is not possible to obtain permission to use the work, then this favors fair use.

For further assistance with fair use, consult the Office for Scholarly Communication's guide, Fair Use: Made for the Harvard Community and the Office of the General Counsel's Copyright and Fair Use: A Guide for the Harvard Community .

What are my options if I don’t have a strong fair use claim?

Consider the following options if you find you cannot reasonably make a fair use claim for the content you wish to incorporate:

- Seek permission from the copyright holder.

- Use openly licensed content as an alternative to the original third-party content you intended to use. Openly-licensed content grants permission up-front for reuse of in-copyright content, provided your use meets the terms of the open license.

- Use content in the public domain, as this content is not in-copyright and is therefore free of all copyright restrictions. Whereas third-party content is owned by parties other than you, no one owns content in the public domain; everyone, therefore, has the right to use it.

For use of images in your dissertation, please consult this guide to Finding Public Domain & Creative Commons Media , which is a great resource for finding images without copyright restrictions.

Who can help me with questions about copyright and fair use?

Contact your Copyright First Responder . Please note, Copyright First Responders assist with questions concerning copyright and fair use, but do not assist with the process of obtaining permission from copyright holders.

Pages should be assigned a number except for the Dissertation Acceptance Certificate . Preliminary pages (abstract, table of contents, list of tables, graphs, illustrations, and preface) should use small Roman numerals (i, ii, iii, iv, v, etc.). All pages must contain text or images.

Count the title page as page i and the copyright page as page ii, but do not print page numbers on either page .

For the body of text, use Arabic numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.) starting with page 1 on the first page of text. Page numbers must be centered throughout the manuscript at the top or bottom. Every numbered page must be consecutively ordered, including tables, graphs, illustrations, and bibliography/index (if included); letter suffixes (such as 10a, 10b, etc.) are not allowed. It is customary not to have a page number on the page containing a chapter heading.

- Check pagination carefully. Account for all pages.

A copy of the Dissertation Acceptance Certificate (DAC) should appear as the first page. This page should not be counted or numbered. The DAC will appear in the online version of the published dissertation. The author name and date on the DAC and title page should be the same.

The dissertation begins with the title page; the title should be as concise as possible and should provide an accurate description of the dissertation. The author name and date on the DAC and title page should be the same.

- Do not print a page number on the title page. It is understood to be page i for counting purposes only.

A copyright notice should appear on a separate page immediately following the title page and include the copyright symbol ©, the year of first publication of the work, and the name of the author:

© [ year ] [ Author’s Name ] All rights reserved.

Alternatively, students may choose to license their work openly under a Creative Commons license. The author remains the copyright holder while at the same time granting up-front permission to others to read, share, and (depending on the license) adapt the work, so long as proper attribution is given. (By default, under copyright law, the author reserves all rights; under a Creative Commons license, the author reserves some rights.)

- Do not print a page number on the copyright page. It is understood to be page ii for counting purposes only.

An abstract, numbered as page iii , should immediately follow the copyright page and should state the problem, describe the methods and procedures used, and give the main results or conclusions of the research. The abstract will appear in the online and bound versions of the dissertation and will be published by ProQuest. There is no maximum word count for the abstract.

- double-spaced

- left-justified

- indented on the first line of each paragraph

- The author’s name, right justified

- The words “Dissertation Advisor:” followed by the advisor’s name, left-justified (a maximum of two advisors is allowed)

- Title of the dissertation, centered, several lines below author and advisor

Dissertations divided into sections must contain a table of contents that lists, at minimum, the major headings in the following order:

- Front Matter

- Body of Text

- Back Matter

Front matter includes (if applicable):

- acknowledgements of help or encouragement from individuals or institutions

- a dedication

- a list of illustrations or tables

- a glossary of terms

- one or more epigraphs.

Back matter includes (if applicable):

- bibliography

- supplemental materials, including figures and tables

- an index (in rare instances).

Supplemental figures and tables must be placed at the end of the dissertation in an appendix, not within or at the end of a chapter. If additional digital information (including audio, video, image, or datasets) will accompany the main body of the dissertation, it should be uploaded as a supplemental file through ProQuest ETD . Supplemental material will be available in DASH and ProQuest and preserved digitally in the Harvard University Archives.

As a matter of copyright, dissertations comprising the student's previously published works must be authorized for distribution from DASH. The guidelines in this section pertain to any previously published material that requires permission from publishers or other rightsholders before it may be distributed from DASH. Please note:

- Authors whose publishing agreements grant the publisher exclusive rights to display, distribute, and create derivative works will need to seek the publisher's permission for nonexclusive use of the underlying works before the dissertation may be distributed from DASH.

- Authors whose publishing agreements indicate the authors have retained the relevant nonexclusive rights to the original materials for display, distribution, and the creation of derivative works may distribute the dissertation as a whole from DASH without need for further permissions.

It is recommended that authors consult their publishing agreements directly to determine whether and to what extent they may have transferred exclusive rights under copyright. The Office for Scholarly Communication (OSC) is available to help the author determine whether she has retained the necessary rights or requires permission. Please note, however, the Office of Scholarly Communication is not able to assist with the permissions process itself.

- Missing Dissertation Acceptance Certificate. The first page of the PDF dissertation file should be a scanned copy of the Dissertation Acceptance Certificate (DAC). This page should not be counted or numbered as a part of the dissertation pagination.

- Conflicts Between the DAC and the Title Page. The DAC and the dissertation title page must match exactly, meaning that the author name and the title on the title page must match that on the DAC. If you use your full middle name or just an initial on one document, it must be the same on the other document.

- Abstract Formatting Errors. The advisor name should be left-justified, and the author's name should be right-justified. Up to two advisor names are allowed. The Abstract should be double spaced and include the page title “Abstract,” as well as the page number “iii.” There is no maximum word count for the abstract.

- The front matter should be numbered using Roman numerals (iii, iv, v, …). The title page and the copyright page should be counted but not numbered. The first printed page number should appear on the Abstract page (iii).

- The body of the dissertation should be numbered using Arabic numbers (1, 2, 3, …). The first page of the body of the text should begin with page 1. Pagination may not continue from the front matter.

- All page numbers should be centered either at the top or the bottom of the page.

- Figures and tables Figures and tables must be placed within the text, as close to their first mention as possible. Figures and tables that span more than one page must be labeled on each page. Any second and subsequent page of the figure/table must include the “(Continued)” notation. This applies to figure captions as well as images. Each page of a figure/table must be accounted for and appropriately labeled. All figures/tables must have a unique number. They may not repeat within the dissertation.

- Any figures/tables placed in a horizontal orientation must be placed with the top of the figure/ table on the left-hand side. The top of the figure/table should be aligned with the spine of the dissertation when it is bound.

- Page numbers must be placed in the same location on all pages of the dissertation, centered, at the bottom or top of the page. Page numbers may not appear under the table/ figure.

- Supplemental Figures and Tables. Supplemental figures and tables must be placed at the back of the dissertation in an appendix. They should not be placed at the back of the chapter.

- Permission Letters Copyright. permission letters must be uploaded as a supplemental file, titled ‘do_not_publish_permission_letters,” within the dissertation submission tool.