Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, historic document, the declaration of independence.

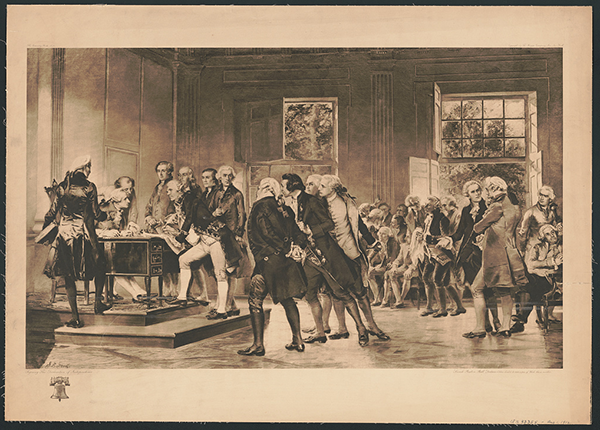

Second Continental Congress | 1776

On July 4, 1776, the United States officially declared its independence from the British Empire when the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration was authored by a “Committee of Five”—John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman—with Jefferson as the main drafter. But Jefferson himself later admitted that he was merely looking to reflect the “mind of Americans”—bringing together the core principles at the heart of the American Revolution. The Declaration also included a list of grievances against King George III, explaining to the world why the American colonies were separating from Great Britain. The American Revolution ended with the Battle of Yorktown in 1781 and the Treaty of Paris in 1783. A little over two decades after King George III took the throne, the American people had broken from Great Britain and begun a new experiment in republican government.

Selected by

The National Constitution Center

In Congress, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, —That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.—Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Smith's Primary Thesis

The Invisible Hand

- Government Interference

- Elements of Prosperity

- Overthrow of Mercantilism

- Faults of "The Wealth of Nations"

The Bottom Line

Adam smith and "the wealth of nations".

Adam Hayes, Ph.D., CFA, is a financial writer with 15+ years Wall Street experience as a derivatives trader. Besides his extensive derivative trading expertise, Adam is an expert in economics and behavioral finance. Adam received his master's in economics from The New School for Social Research and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in sociology. He is a CFA charterholder as well as holding FINRA Series 7, 55 & 63 licenses. He currently researches and teaches economic sociology and the social studies of finance at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/adam_hayes-5bfc262a46e0fb005118b414.jpg)

What was the most important document published in 1776? Most Americans would probably say "The Declaration of Independence." However, many would argue that Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations had a bigger and more global impact.

On March 9, 1776, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations —commonly referred to simply as The Wealth of Nations —was first published. Smith, a Scottish moral philosopher by trade, wrote the book to describe the industrialized capitalist system that was upending the mercantilist system.

Mercantilism held that wealth was fixed and finite. The only way to prosper was to hoard gold and place tariffs on products from abroad. According to this theory, nations should sell their goods to other countries while buying nothing in return. Predictably, countries fell into rounds of retaliatory tariffs that choked off international trade .

Key Takeaways

- The central thesis of Smith's The Wealth of Nations is that our individual need to fulfill self-interest results in societal benefit.

- He called the force behind this fulfillment the invisible hand.

- Self-interest and the division of labor in an economy result in mutual interdependencies that promote stability and prosperity through the market mechanism.

- Smith rejected government interference in market activities.

- He believed that a government's three functions should be to protect national borders, enforce civil law, and engage in public works (e.g., education).

Smith's Primary Thesis

The core of Smith's thesis was that humans' natural tendency for self-interest (or in modern terms, looking out for yourself) results in prosperity.

Smith argued that by giving everyone the freedom to produce and exchange goods as they pleased (free trade) and opening the markets up to domestic and foreign competition, people's natural self-interest would promote greater prosperity than could stringent government regulations.

Smith believed humans ultimately promote public interest through their everyday economic choices. In The Wealth of Nations he wrote:

He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain; and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.

This free-market force which Adam Smith called the invisible hand needed support to bring about its magic. In particular, the market that emerged from an increasing division of labor, both within production processes and throughout society, created a series of mutual interdependencies. These relationships promoted social welfare through individual profit motives.

In other words, if you specialize as a baker and produce only bread, you must rely on somebody else for your clothes, your meat, and your beer. Meanwhile, the people that specialize in clothes must rely on you for their bread, and so on. Prosperity emanates from the market that develops when people need goods and services that they can't create themselves.

Adam Smith is generally regarded as the father of modern economics.

The automatic pricing and distribution mechanisms in the economy (Smith's invisible hand) interact directly and indirectly with centralized, top-down planning authorities.

Human Nature vs. Government Policy

The invisible hand is not an actual, distinguishable entity. Instead, it is the sum of many phenomena that occur naturally when consumers and producers engage in commerce. Smith's insight was one of the most important in the history of economics. It remains one of the chief justifications for free-market ideologies.

Modern interpretations of the invisible hand theorem suggest that the means of production and distribution should be privately owned and that if trade occurs unfettered by regulation, in turn, society will flourish organically. These interpretations compete with the concept and function of government.

Government is not serendipitous. It is prescriptive and intentional. Politicians, regulators, and those who exercise legal force (such as the courts, police, and military) pursue defined goals through coercion.

In contrast, macroeconomic forces—supply and demand, buying and selling, profit and loss—occur voluntarily until government policy inhibits or overrides them. In this sense, it is accurate to conclude that government affects the invisible hand, not the other way around.

Government Interference in Free Markets

The absence of market mechanisms frustrates government planning. Some economists refer to this as the economic calculation problem.

When people and businesses make decisions based on their willingness to pay money for a good or service, that information is captured dynamically in the price mechanism. This, in turn, allocates resources automatically toward the most valued ends.

When governments interfere with this process, unwanted shortages and surpluses tend to occur. Consider the massive gas shortages in the United States during the 1970s. The then newly formed Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) cut production to raise oil prices. The Nixon and Ford administrations responded by introducing price controls to limit the cost of gasoline to American consumers. The goal was to make cheap gas available to the public.

Instead, gas stations had no incentive to stay open for more than a few hours. Oil companies had no incentive to increase production domestically. Consumers had every incentive to buy more gasoline than they needed. Large-scale shortages and gas lines resulted. Those gas lines disappeared almost immediately after controls were eliminated and prices were allowed to rise.

While some might be tempted to say that the invisible hand limits government, that wouldn't necessarily be correct. Rather, the forces that guide voluntary economic activity toward large societal benefit are the same forces that limit the effectiveness of government intervention.

Enlightened self-interest refers to the concept that regard for one's own good prompts a person to assist in promoting the good of others.

Smith's Elements of Prosperity

Smith believed a nation needed the following three elements to bring about universal prosperity.

1. Enlightened Self-Interest

Smith wanted people to practice thrift , hard work, and enlightened self-interest. He thought the practice of enlightened self-interest was natural for the majority of people.

In his famous example, a butcher does not supply meat based on good-hearted intentions, but because he profits by selling meat. If the meat he sells is poor, he will not have repeat customers and, thus, no profit.

Therefore, it's in the butcher's interest to sell good meat at a price that customers are willing to pay, so that both parties benefit in every transaction.

Smith believed that a long term point of view would keep most businesses from abusing customers. When that wasn't enough, he looked to government to enforce laws.

Likewise, Smith saw thrift and savings as important virtues, especially when savings were invested. Through investment, industry would have the capital to buy more labor-saving machinery and encourage innovation. This technological leap forward would increase returns on invested capital and raise the overall standard of living .

2. Limited Government

Smith saw the responsibilities of the government as being limited to the defense of the nation, universal education, public works (infrastructure such as roads and bridges), the enforcement of legal rights (property rights and contracts), and the punishment of crime.

The government should step in when people acted on their short-term interests. It should make and enforce laws against robbery, fraud, and other, similar crimes. Smith cautioned against larger, bureaucratic governments, writing, "there is no art which one government sooner learns of another, than that of draining money from the pockets of the people."

Smith believed that the role of universal education was to counteract the negative and dulling effects of the division of labor that was a necessary part of industrialization.

3. Solid Currency and Free-Market Economy

The third element Smith proposed was a solid currency twinned with free-market principles. By backing currency with hard metals, Smith hoped to curtail the government's ability to depreciate currency by circulating more of it. In turn, this could curb wasteful expenditures (such as spending on wars).

With hard currency acting as a check on spending, Smith wanted the government to follow free-market principles. These included keeping taxes low and eliminating tariffs to allow for free trade across borders. He pointed out that tariffs and other taxes only succeeded in making life more expensive for the people while stifling industry and trade abroad.

Smith’s Theories Overthrow Mercantilism

To drive home his point about the damaging nature of tariffs, Smith used the example of making wine in Scotland. He pointed out that good grapes could be grown in Scotland in hothouses. Yet the extra costs of heating would make Scottish wine 30 times more expensive than French wines. It would be far better, he reasoned, to trade something Scotland had in abundance, such as wool, for French wine.

France may have had a competitive advantage in producing wine. However, tariffs aimed at creating and protecting a Scottish wine industry would just waste resources and cost the public money.

Faults of "The Wealth of Nations"

The Wealth of Nations is a seminal book that represents the birth of free-market economics, but it's not without faults. It lacks proper explanations for pricing or a theory of value. Also, Smith failed to see the importance of the entrepreneur in breaking up inefficiencies and creating new markets.

Both the opponents of and believers in Adam Smith's free-market capitalism have added to the thesis of The Wealth of Nations . Like any good theory, free-market capitalism gets stronger with each reformulation, whether prompted by friend or foe.

Marginal utility , comparative advantage , entrepreneurship, the time-preference theory of interest, monetary theory , and many other pieces have been added to the whole since 1776.

There is still work to be done as the size and interconnectedness of the world's economies spur new and unexpected challenges to free-market capitalism.

Who Was Adam Smith?

Adam Smith was a philosopher and economic theorist born in Scotland in 1723. He's known primarily for his groundbreaking 1776 book on economics called An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations . Smith introduced the concept that free trade would benefit individuals and society as a whole. He believed that governments should not impose policies that interfered with free trade, domestically and abroad.

What Was Smith's Invisible Hand?

Adam Smith referred to the natural forces that guided self-interest to fulfill people's and society's needs on its own, without government intervention, as the invisible hand.

What Does Free-Market Capitalism Mean?

Free-market capitalism is an economic system that supports the free flow of capital and exchange of goods between individuals and nations without governments intervening to control that flow. In a free market, people in the market will price goods and services more effectively than a government.

The publishing of The Wealth of Nations marked the birth of modern capitalism as well as modern economics. Oddly enough, Adam Smith, the champion of the free market, spent the last years of his life as the Commissioner of Customs, responsible for enforcing all the tariffs. He took his work to heart and burned many of his clothes when he discovered they had been smuggled into shops from abroad.

Historical irony aside, his invisible hand continues to be a powerful force today. Smith overturned the miserly view of mercantilism and gave us a vision of plenty and freedom for all.

The free market he envisioned, though not yet fully realized, may have done more to raise the global standard of living than any other single idea in history.

Christie's. " The Wealth of Nations Adam Smith, 1776 ."

Project Gutenberg. " An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations ."

The University of Chicago Press Journals. " The Political Economy of Gasoline Taxes: Lessons from the Oil Embargo ," Pages 104-108.

Ian Simpson Ross. "The Life of Adam Smith," Page 6. Oxford University Press, 2010.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Economies-of-Scale-56a093c45f9b58eba4b1b0b2.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

The American Revolution Reader

Primary source: thomas paine calls for american independence, 1776.

Common Sense is a pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–76 that inspired people in the Thirteen Colonies to declare and fight for independence from Great Britain in the summer of 1776. The pamphlet explained the advantages of and the need for immediate independence in clear, simple language. It was published anonymously on January 10, 1776, at the beginning of the American Revolution and became an immediate sensation. It was sold and distributed widely and read aloud at taverns and meeting places.

Washington had it read to all his troops, which at the time had surrounded the British army in Boston. In proportion to the population of the colonies at that time (2.5 million), it had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history. As of 2006, it remains the all-time best selling American title.

Common Sense presented the American colonists with an argument for freedom from British rule at a time when the question of whether or not to seek independence was the central issue of the day. Paine wrote and reasoned in a style that common people understood. Forgoing the philosophical and Latin references used by Enlightenment era writers, he structured Common Sense as if it were a sermon, and relied on Biblical references to make his case to the people. He connected independence with common dissenting Protestant beliefs as a means to present a distinctly American political identity. Historian Gordon S. Wood described Common Sense as “the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era.”

Thoughts of the present state of American Affairs

The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ‘Tis not the affair of a city, a country, a province, or a kingdom, but of a continent of at least one eighth part of the habitable globe. ‘Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed time of continental union, faith and honor. The least fracture now will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; The wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

By referring the matter from argument to arms, a new æra for politics is struck; a new method of thinking hath arisen. All plans, proposals, &c. prior to the nineteenth of April, i. e. to the commencement of hostilities, are like the almanacks of the last year; which, though proper then, are superceded and useless now. Whatever was advanced by the advocates on either side of the question then, terminated in one and the same point, viz. a union with Great-Britain; the only difference between the parties was the method of effecting it; the one proposing force, the other friendship; but it hath so far happened that the first hath failed, and the second hath withdrawn her influence.

As much hath been said of the advantages of reconciliation, which, like an agreeable dream, hath passed away and left us as we were, it is but right, that we should examine the contrary side of the argument, and inquire into some of the many material injuries which these colonies sustain, and always will sustain, by being connected with, and dependant on Great-Britain. To examine that connexion and dependance, on the principles of nature and common sense, to see what we have to trust to, if separated, and what we are to expect, if dependant.

I have heard it asserted by some, that as America hath flourished under her former connexion with Great-Britain, that the same connexion is necessary towards her future happiness, and will always have the same effect. Nothing can be more fallacious than this kind of argument. We may as well assert that because a child has thrived upon milk, that it is never to have meat, or that the first twenty years of our lives is to become a precedent for the next twenty. But even this is admitting more than is true, for I answer roundly, that America would have flourished as much, and probably much more, had no European power had any thing to do with her. The commerce, by which she hath enriched herself are the necessaries of life, and will always have a market while eating is the custom of Europe.

But she has protected us, say some. That she hath engrossed us is true, and defended the continent at our expence as well as her own is admitted, and she would have defended Turkey from the same motive, viz. the sake of trade and dominion.

Alas, we have been long led away by ancient prejudices, and made large sacrifices to superstition. We have boasted the protection of Great-Britain, without considering, that her motive was interest not attachment; that she did not protect us from our enemies on our account, but from her enemies on her own account, from those who had no quarrel with us on any other account, and who will always be our enemies on the same account. Let Britain wave her pretensions to the continent, or the continent throw off the dependance, and we should be at peace with France and Spain were they at war with Britain. The miseries of Hanover last war ought to warn us against connexions.

It hath lately been asserted in parliament, that the colonies have no relation to each other but through the parent country, i. e. that Pennsylvania and the Jerseys, and so on for the rest, are sister colonies by the way of England; this is certainly a very round-about way of proving relationship, but it is the nearest and only true way of proving enemyship, if I may so call it. France and Spain never were, nor perhaps ever will be our enemies as Americans, but as our being the subjects of Great-Britain.

But Britain is the parent country, say some. Then the more shame upon her conduct. Even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their families; wherefore the assertion, if true, turns to her reproach; but it happens not to be true, or only partly so, and the phrase parent or mother country hath been jesuitically adopted by the king and his parasites, with a low papistical design of gaining an unfair bias on the credulous weakness of our minds. Europe, and not England, is the parent country of America. This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe. Hither have they fled, not from the tender embraces of the mother, but from the cruelty of the monster; and it is so far true of England, that the same tyranny which drove the first emigrants from home, pursues their descendants still.

In this extensive quarter of the globe, we forget the narrow limits of three hundred and sixty miles (the extent of England) and carry our friendship on a larger scale; we claim brotherhood with every European Christian, and triumph in the generosity of the sentiment.

It is pleasant to observe by what regular gradations we surmount the force of local prejudice, as we enlarge our acquaintance with the world. A man born in any town in England divided into parishes, will naturally associate most with his fellow parishioners (because their interests in many cases will be common) and distinguish him by the name of neighbour; if he meet him but a few miles from home, he drops the narrow idea of a street, and salutes him by the name of townsman; if he travel out of the county, and meet him in any other, he forgets the minor divisions of street and town, and calls him countryman; i. e. county-man; but if in their foreign excursions they should associate in France or any other part of Europe, their local remembrance would be enlarged into that of Englishmen. And by a just parity of reasoning, all Europeans meeting in America, or any other quarter of the globe, are countrymen; for England, Holland, Germany, or Sweden, when compared with the whole, stand in the same places on the larger scale, which the divisions of street, town, and county do on the smaller ones; distinctions too limited for continental minds. Not one third of the inhabitants, even of this province, are of English descent. Wherefore I reprobate the phrase of parent or mother country applied to England only, as being false, selfish, narrow and ungenerous.

But admitting, that we were all of English descent, what does it amount to? Nothing. Britain, being now an open enemy, extinguishes every other name and title: And to say that reconciliation is our duty, is truly farcical. The first king of England, of the present line (William the Conqueror) was a Frenchman, and half the Peers of England are descendants from the same country; wherefore, by the same method of reasoning, England ought to be governed by France.

Much hath been said of the united strength of Britain and the colonies, that in conjunction they might bid defiance to the world. But this is mere presumption; the fate of war is uncertain, neither do the expressions mean any thing; for this continent would never suffer itself to be drained of inhabitants, to support the British arms in either Asia, Africa, or Europe.

Besides, what have we to do with setting the world at defiance? Our plan is commerce, and that, well attended to, will secure us the peace and friendship of all Europe; because, it is the interest of all Europe to have America a free port. Her trade will always be a protection, and her barrenness of gold and silver secure her from invaders.

I challenge the warmest advocate for reconciliation, to shew, a single advantage that this continent can reap, by being connected with Great Britain. I repeat the challenge, not a single advantage is derived. Our corn will fetch its price in any market in Europe, and our imported goods must be paid for buy them where we will.

But the injuries and disadvantages we sustain by that connection, are without number; and our duty to mankind at large, as well as to ourselves, instruct us to renounce the alliance: Because, any submission to, or dependance on Great-Britain, tends directly to involve this continent in European wars and quarrels; and sets us at variance with nations, who would otherwise seek our friendship, and against whom, we have neither anger nor complaint. As Europe is our market for trade, we ought to form no partial connection with any part of it. It is the true interest of America to steer clear of European contentions, which she never can do, while by her dependance on Britain, she is made the make-weight in the scale on British politics.

Europe is too thickly planted with kingdoms to be long at peace, and whenever a war breaks out between England and any foreign power, the trade of America goes to ruin, because of her connection with Britain. The next war may not turn out like the last, and should it not, the advocates for reconciliation now will be wishing for separation then, because, neutrality in that case, would be a safer convoy than a man of war. Every thing that is right or natural pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, ‘TIS TIME TO PART. Even the distance at which the Almighty hath placed England and America, is a strong and natural proof, that the authority of the one, over the other, was never the design of Heaven. The time likewise at which the continent was discovered, adds weight to the argument, and the manner in which it was peopled encreases the force of it. The Reformation was preceded by the discovery of America, as if the Almighty graciously meant to open a sanctuary to the persecuted in future years, when home should afford neither friendship nor safety.

The authority of Great-Britain over this continent, is a form of government, which sooner or later must have an end: And a serious mind can draw no true pleasure by looking forward, under the painful and positive conviction, that what he calls “the present constitution” is merely temporary. As parents, we can have no joy, knowing that this government is not sufficiently lasting to ensure any thing which we may bequeath to posterity: And by a plain method of argument, as we are running the next generation into debt, we ought to do the work of it, otherwise we use them meanly and pitifully. In order to discover the line of our duty rightly, we should take our children in our hand, and fix our station a few years farther into life; that eminence will present a prospect, which a few present fears and prejudices conceal from our sight.

- Introduction to Common Sense. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_Sense_%28pamphlet%29 . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Excerpt from Common Sense. Provided by : Wikisource. Located at : https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Common_Sense . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Declaration of Independence

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Declaration of Independence was the first formal statement by a nation’s people asserting their right to choose their own government.

When armed conflict between bands of American colonists and British soldiers began in April 1775, the Americans were ostensibly fighting only for their rights as subjects of the British crown. By the following summer, with the Revolutionary War in full swing, the movement for independence from Britain had grown, and delegates of the Continental Congress were faced with a vote on the issue. In mid-June 1776, a five-man committee including Thomas Jefferson , John Adams and Benjamin Franklin was tasked with drafting a formal statement of the colonies’ intentions. The Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence—written largely by Jefferson—in Philadelphia on July 4 , a date now celebrated as the birth of American independence.

America Before the Declaration of Independence

Even after the initial battles in the Revolutionary War broke out, few colonists desired complete independence from Great Britain, and those who did–like John Adams– were considered radical. Things changed over the course of the next year, however, as Britain attempted to crush the rebels with all the force of its great army. In his message to Parliament in October 1775, King George III railed against the rebellious colonies and ordered the enlargement of the royal army and navy. News of his words reached America in January 1776, strengthening the radicals’ cause and leading many conservatives to abandon their hopes of reconciliation. That same month, the recent British immigrant Thomas Paine published “Common Sense,” in which he argued that independence was a “natural right” and the only possible course for the colonies; the pamphlet sold more than 150,000 copies in its first few weeks in publication.

Did you know? Most Americans did not know Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence until the 1790s; before that, the document was seen as a collective effort by the entire Continental Congress.

In March 1776, North Carolina’s revolutionary convention became the first to vote in favor of independence; seven other colonies had followed suit by mid-May. On June 7, the Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion calling for the colonies’ independence before the Continental Congress when it met at the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall) in Philadelphia. Amid heated debate, Congress postponed the vote on Lee’s resolution and called a recess for several weeks. Before departing, however, the delegates also appointed a five-man committee–including Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and Robert R. Livingston of New York–to draft a formal statement justifying the break with Great Britain. That document would become known as the Declaration of Independence.

Thomas Jefferson Writes the Declaration of Independence

Jefferson had earned a reputation as an eloquent voice for the patriotic cause after his 1774 publication of “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” and he was given the task of producing a draft of what would become the Declaration of Independence. As he wrote in 1823, the other members of the committee “unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught [sic]. I consented; I drew it; but before I reported it to the committee I communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting their corrections….I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the committee, and from them, unaltered to the Congress.”

As Jefferson drafted it, the Declaration of Independence was divided into five sections, including an introduction, a preamble, a body (divided into two sections) and a conclusion. In general terms, the introduction effectively stated that seeking independence from Britain had become “necessary” for the colonies. While the body of the document outlined a list of grievances against the British crown, the preamble includes its most famous passage: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The Continental Congress Votes for Independence

The Continental Congress reconvened on July 1, and the following day 12 of the 13 colonies adopted Lee’s resolution for independence. The process of consideration and revision of Jefferson’s declaration (including Adams’ and Franklin’s corrections) continued on July 3 and into the late morning of July 4, during which Congress deleted and revised some one-fifth of its text. The delegates made no changes to that key preamble, however, and the basic document remained Jefferson’s words. Congress officially adopted the Declaration of Independence later on the Fourth of July (though most historians now accept that the document was not signed until August 2).

The Declaration of Independence became a significant landmark in the history of democracy. In addition to its importance in the fate of the fledgling American nation, it also exerted a tremendous influence outside the United States, most memorably in France during the French Revolution . Together with the Constitution and the Bill of Rights , the Declaration of Independence can be counted as one of the three essential founding documents of the United States government.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

When Thomas Jefferson penned ‘all men are created equal,’ he did not mean individual equality, says Stanford scholar

When the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, it was a call for the right to statehood rather than individual liberties, says Stanford historian Jack Rakove. Only after the American Revolution did people interpret it as a promise for individual equality.

In the decades following the Declaration of Independence, Americans began reading the affirmation that “all men are created equal” in different ways than the framers intended, says Stanford historian Jack Rakove .

With each generation, the words expressed in the Declaration of Independence have expanded beyond what the founding fathers originally intended when they adopted the historic document on July 4, 1776, says Stanford historian Jack Rakove. (Image credit: Getty Images)

On July 4, 1776, when the Continental Congress adopted the historic text drafted by Thomas Jefferson, they did not intend it to mean individual equality. Rather, what they declared was that American colonists, as a people , had the same rights to self-government as other nations. Because they possessed this fundamental right, Rakove said, they could establish new governments within each of the states and collectively assume their “separate and equal station” with other nations. It was only in the decades after the American Revolutionary War that the phrase acquired its compelling reputation as a statement of individual equality.

Here, Rakove reflects on this history and how now, in a time of heightened scrutiny of the country’s founders and the legacy of slavery and racial injustices they perpetuated, Americans can better understand the limitations and failings of their past governments.

Rakove is the William Robertson Coe Professor of History and American Studies and professor of political science, emeritus, in the School of Humanities and Sciences. His book, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (1996), won the Pulitzer Prize in History. His new book, Beyond Belief, Beyond Conscience: The Radical Significance of the Free Exercise of Religion will be published next month.

With the U.S. confronting its history of systemic racism, are there any problems that Americans are reckoning with today that can be traced back to the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution?

I view the Declaration as a point of departure and a promise, and the Constitution as a set of commitments that had lasting consequences – some troubling, others transformative. The Declaration, in its remarkable concision, gives us self-evident truths that form the premises of the right to revolution and the capacity to create new governments resting on popular consent. The original Constitution, by contrast, involved a set of political commitments that recognized the legal status of slavery within the states and made the federal government partially responsible for upholding “the peculiar institution.” As my late colleague Don Fehrenbacher argued, the Constitution was deeply implicated in establishing “a slaveholders’ republic” that protected slavery in complex ways down to 1861.

But the Reconstruction amendments of 1865-1870 marked a second constitutional founding that rested on other premises. Together they made a broader definition of equality part of the constitutional order, and they gave the national government an effective basis for challenging racial inequalities within the states. It sadly took far too long for the Second Reconstruction of the 1960s to implement that commitment, but when it did, it was a fulfillment of the original vision of the 1860s.

As people critically examine the country’s founding history, what might they be surprised to learn from your research that can inform their understanding of American history today?

Two things. First, the toughest question we face in thinking about the nation’s founding pivots on whether the slaveholding South should have been part of it or not. If you think it should have been, it is difficult to imagine how the framers of the Constitution could have attained that end without making some set of “compromises” accepting the legal existence of slavery. When we discuss the Constitutional Convention, we often praise the compromise giving each state an equal vote in the Senate and condemn the Three Fifths Clause allowing the southern states to count their slaves for purposes of political representation. But where the quarrel between large and small states had nothing to do with the lasting interests of citizens – you never vote on the basis of the size of the state in which you live – slavery was a real and persisting interest that one had to accommodate for the Union to survive.

Second, the greatest tragedy of American constitutional history was not the failure of the framers to eliminate slavery in 1787. That option was simply not available to them. The real tragedy was the failure of Reconstruction and the ensuing emergence of Jim Crow segregation in the late 19th century that took many decades to overturn. That was the great constitutional opportunity that Americans failed to grasp, perhaps because four years of Civil War and a decade of the military occupation of the South simply exhausted Northern public opinion. Even now, if you look at issues of voter suppression, we are still wrestling with its consequences.

You argue that in the decades after the Declaration of Independence, Americans began understanding the Declaration of Independence’s affirmation that “all men are created equal” in a different way than the framers intended. How did the founding fathers view equality? And how did these diverging interpretations emerge?

When Jefferson wrote “all men are created equal” in the preamble to the Declaration, he was not talking about individual equality. What he really meant was that the American colonists, as a people , had the same rights of self-government as other peoples, and hence could declare independence, create new governments and assume their “separate and equal station” among other nations. But after the Revolution succeeded, Americans began reading that famous phrase another way. It now became a statement of individual equality that everyone and every member of a deprived group could claim for himself or herself. With each passing generation, our notion of who that statement covers has expanded. It is that promise of equality that has always defined our constitutional creed.

Thomas Jefferson drafted a passage in the Declaration, later struck out by Congress, that blamed the British monarchy for imposing slavery on unwilling American colonists, describing it as “the cruel war against human nature.” Why was this passage removed?

At different moments, the Virginia colonists had tried to limit the extent of the slave trade, but the British crown had blocked those efforts. But Virginians also knew that their slave system was reproducing itself naturally. They could eliminate the slave trade without eliminating slavery. That was not true in the West Indies or Brazil.

The deeper reason for the deletion of this passage was that the members of the Continental Congress were morally embarrassed about the colonies’ willing involvement in the system of chattel slavery. To make any claim of this nature would open them to charges of rank hypocrisy that were best left unstated.

If the founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, thought slavery was morally corrupt, how did they reconcile owning slaves themselves, and how was it still built into American law?

Two arguments offer the bare beginnings of an answer to this complicated question. The first is that the desire to exploit labor was a central feature of most colonizing societies in the Americas, especially those that relied on the exportation of valuable commodities like sugar, tobacco, rice and (much later) cotton. Cheap labor in large quantities was the critical factor that made these commodities profitable, and planters did not care who provided it – the indigenous population, white indentured servants and eventually African slaves – so long as they were there to be exploited.

To say that this system of exploitation was morally corrupt requires one to identify when moral arguments against slavery began to appear. One also has to recognize that there were two sources of moral opposition to slavery, and they only emerged after 1750. One came from radical Protestant sects like the Quakers and Baptists, who came to perceive that the exploitation of slaves was inherently sinful. The other came from the revolutionaries who recognized, as Jefferson argued in his Notes on the State of Virginia , that the very act of owning slaves would implant an “unremitting despotism” that would destroy the capacity of slaveowners to act as republican citizens. The moral corruption that Jefferson worried about, in other words, was what would happen to slaveowners who would become victims of their own “boisterous passions.”

But the great problem that Jefferson faced – and which many of his modern critics ignore – is that he could not imagine how black and white peoples could ever coexist as free citizens in one republic. There was, he argued in Query XIV of his Notes , already too much foul history dividing these peoples. And worse still, Jefferson hypothesized, in proto-racist terms, that the differences between the peoples would also doom this relationship. He thought that African Americans should be freed – but colonized elsewhere. This is the aspect of Jefferson’s thinking that we find so distressing and depressing, for obvious reasons. Yet we also have to recognize that he was trying to grapple, I think sincerely, with a real problem.

No historical account of the origins of American slavery would ever satisfy our moral conscience today, but as I have repeatedly tried to explain to my Stanford students, the task of thinking historically is not about making moral judgments about people in the past. That’s not hard work if you want to do it, but your condemnation, however justified, will never explain why people in the past acted as they did. That’s our real challenge as historians.

David McCullough

Everything you need for every book you read..

- Essays by Theme

- Political Economy

Division of Labor, Part 1

political economy division of labor wealth of nations pin factory extent of the market

Political economy, considered as a branch of the science of a statesman or legislator, proposes two distinct objects: first, to provide a plentiful revenue or subsistence for the people, or more properly to enable them to provide such a revenue or subsistence for themselves; and secondly, to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue sufficient for the public services. It proposes to enrich both the people and the sovereign. (Smith, 1776, Book IV).

For just as all other arts are developed to superior excellence in large cities, in that same way the food at the king’s palace is also elaborately prepared with superior excellence. For in small towns the same workman makes chairs and doors and plows and tables, and often this same artisan builds houses, and even so he is thankful if he can only find employment enough to support him. And it is, of course, impossible for a man of many trades to be proficient in all of them. In large cities, on the other hand, inasmuch as many people have demands to make upon each branch of industry, one trade alone, and very often even less than a whole trade, is enough to support a man: one man, for instance, makes shoes for men, and another for women; and there are places even where one man earns a living by only stitching shoes, another by cutting them out, another by sewing the uppers together, while there is another who performs none of these operations but only assembles the parts. It follows, therefore, as a matter of course, that he who devotes himself to a very highly specialized line of work is bound to do it in the best possible manner. (333; emphasis added).

(Socrates) A State, I said, arises, as I conceive, out of the needs of mankind; no one is self-sufficing, but all of us have many wants. Can any other origin of a State be imagined? (Adeimantus) There can be no other. (Socrates) Then, as we have many wants, and many persons are needed to supply them, one takes a helper for one purpose and another for another; and when these partners and helpers are gathered together in one habitation the body of inhabitants is termed a State… And they exchange with one another, and one gives, and another receives….that the exchange will be for their good. ( Republic , Book II)

The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgement with which it is any where directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labor.

- Causes: “… owing to three different circumstances; first , to the increase of dexterity in every particular workman …” That is, “labor” is not homogeneous; an experienced worker is more dexterous. But the required “experience” is actually determined by the division of labor! By breaking up the work into smaller parts the increase in productivity through dexterity is multiplied. Even a very dexterous artisan could realize the productivity gains captured by breaking the work up into 4, or in the case of Smith’s pin factory example, 18 separate smaller steps. Each of the 4 activities would be a “job,” in the small shop, and each of the 18 separate activities would be a “job” in a larger factory. The nature of jobs themselves, and what dexterity means, comes to depend on the extent of the market.

- “… secondly , to the saving of the time which is commonly lost in passing from one species of work to another; …..” Smith makes a memorable assessment of the problem here, when he says that, even if a person is working energetically, when that person switches from one task to another, “he commonly saunters a little.” Here Smith anticipates the famous “Time and Motion” studies (Taylor, 2003) that sought efficiency in work processes. Of course, Taylorism was applied to the individual jobs along a production line, but that was only because Smith had already figured out that the really big savings in “time and motion” was to apply division of labor in the first place.

- and lastly , to the invention of a great number of machines which facilitate and abridge labour, and enable one man to do the work of many .” Here, Smith includes a dynamic component that proved prescient. Of course, Smith was thinking at most of hand tools, or of the simplest kind of crude machinery. Still, fully foreseen or not, Smith recognized the opportunities to design new tools and new machinery. A person who does the same small task thousands of times conceives a tool to make it easier and faster and then envisions a way of using another machine to manipulate the first tool, and so on. Eventually, many steps are replaced by one machine.

- International

- Today’s Paper

- Premium Stories

- Bihar 10th Result

- Express Shorts

- Health & Wellness

- Board Exam Results

Explained: What is the 1776 Commission report released by White House?

The initiative, dubbed the ‘1776 commission’, is an apparent counter to the 1619 project, a pulitzer prize-winning collection of essays on african american history of the past four centuries, which explores the black community’s contribution in nation-building since the era of slavery to modern times..

The White House on Monday released the 1776 Commission report, just days before president-elect Joe Biden would take his oath in office. In September last year, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order to set up a “national commission to promote patriotic education” in the country. The move was aimed at pleasing his conservative voter base in the run-up to the November 3 elections.

The initiative, dubbed the ‘1776 Commission’, is an apparent counter to The 1619 Project , a Pulitzer Prize-winning collection of essays on African American history of the past four centuries, which explores the Black community’s contribution in nation-building since the era of slavery to modern times.

Trump announced the move at a history conference celebrating the 233rd anniversary of the signing of the US Constitution (on September 17, 1787); the document being written in the decade after the original 13 colonies declared independence from the British Empire in 1776.

In September, Trump said that he wanted $5 billion from companies that were building the US version of TikTok for setting up the “very large fund” that would teach American children “the real history, not the fake history.”

What is The 1619 Project?

The Project is a special initiative of The New York Times Magazine, launched in 2019 to mark the completion of 400 years since the first enslaved Africans arrived in colonial Virginia’s Jamestown in August 1619.

The project was initiated by Nikole Hannah-Jones, a MacArthur Grant-winning journalist. The collection aims “to reframe US history by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year,” according to Jake Silverstein, the publication’s editor-in-chief.

What is Trump’s 1776 Commission?

When he set it up, Trump was lagging behind president-elect Biden in polls for the presidential race. With this move Trump sought to activate his right-wing supporters by doubling down on what he described as “cancel culture”, “critical race theory” and “revisionist history”.

In remarks delivered at the National Archives Museum, where original copies of the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution and the Bill of Rights are kept, Trump said at the time, “Students in our universities are inundated with critical race theory. This is a Marxist doctrine holding that America is a wicked and racist nation, that even young children are complicit in oppression, and that our entire society must be radically transformed.”

A new “1776 Commission”, Trump said, would “encourage our educators to teach our children about the miracle of American history and make plans to honor the 250th anniversary of our founding,” and teach the youth to “love America.”

“The Left has warped, distorted, and defiled the American story. We want our sons and daughters to know they are the citizens of the most exceptional nation in the history of the world,” he added.

What does the report say?

According to a report in The New York Times, the 18-member commission formed by Trump “includes no professional historians but a number of conservative activists, politicians and intellectuals — in the heat of his re-election campaign in September, as he cast himself as a defender of traditional American heritage against “radical” liberals.”

“The declared purpose of the President’s Advisory 1776 Commission is to “enable a rising generation to understand the history and principles of the founding of the United States in 1776 and to strive to form a more perfect Union.” This requires a restoration of American education, which can only be grounded on a history of those principles that is “accurate, honest, unifying, inspiring, and ennobling.” And a rediscovery of our shared identity rooted in our founding principles is the path to a renewed American unity and a confident American future,” the report says.

What have critics said about this commission?

Critics have lambasted Trump for making false claims during the speech in September and accused him of infringing on constitutional liberties.

During his address, Trump said that the USA’s founding “set in motion the unstoppable chain of events that abolished slavery”, while many pointed out that the institution continued unabated for almost two-and-a-half centuries, including 89 years after American independence.

Hannah-Jones, the 1619 Project’s founder, said at the time, “These are hard days we’re in but I take great satisfaction from knowing that now even Trump’s supporters know the date 1619 and mark it as the beginning of American slavery. 1619 is part of the national lexicon. That cannot be undone, no matter how hard they try.”

Hannah-Jones has also previously criticised Trump’s opposition to teaching the 1619 Project in schools as a government attempt to infringe on the First Amendment right to free speech and press in the country. She said, “The efforts by the president of the United States to use his powers to censor a work of American journalism by dictating what schools can and cannot teach and what American children should and should not learn should be deeply alarming to all Americans who value free speech.”

Interpreting the move

By attacking The 1619 Project, Trump hoped to win the support of conservatives who oppose its central idea that US history should be reframed around the date of August 1619, and who insist that the nation’s story should be told the way it has been over the years– beginning with the year 1776, when the Declaration of Independence was signed, or from 1788, when the US Constitution was ratified.

Last year, Trump threatened to withhold federal funding from public schools that used school syllabi based on the 1619 Project– which he said “warped” American history, adding that it claimed the US was “founded on the principle of oppression, not freedom”.

Will this be MS Dhoni’s Last Dance? Subscriber Only

What makes Ashish Vidyarthi’s stand-up special? Subscriber Only

With dogs, do size and breed matter? Subscriber Only

Patna Shuklla movie review

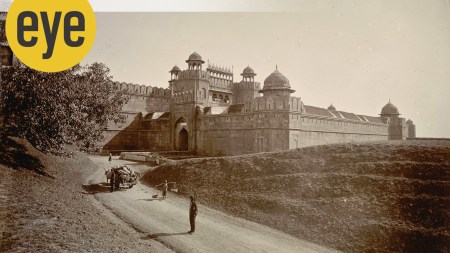

Why is the Red Fort still popular? Subscriber Only

Conservationist's book lives up to it's title Subscriber Only

Amitava Kumar's insights on writers Subscriber Only

Four new exciting book releases Subscriber Only

Knox Goes Away movie review

- donald trump

- Explained Global

- Express Explained

- White House

BSEB will declare the Bihar Board 10th exam results 2024 today at 1:30 pm. Around 16.4 lakh students took the offline exams from February 15 to 23, with strict measures in place to prevent cheating. A press conference will be held at the board's headquarters to announce the toppers' names.

More Explained

Best of Express

EXPRESS OPINION

Mar 31: Latest News

- 01 IPL 2024 fastest balls: Mayank Yadav tops chart with 155.8 kph delivery on debut, Nandre Burger second

- 02 Truce talks between Israel and Hamas to resume Sunday in Cairo, Egyptian local television station says

- 03 Who is Mayank Yadav, LSG debutant who bowled 155.8 kph scorcher against PBKS, fastest ball of IPL 2024

- 04 Ex-Cong leaders, a former diplomat, a Sufi singer: BJP releases first list of 6 candidates for Punjab

- 05 Under AB-MJPJAY: Maharashtra writes to ECI for Rs 5 Lakh universal coverage nod; further delays likely

- Elections 2024

- Political Pulse

- Entertainment

- Movie Review

- Newsletters

- Gold Rate Today

- Silver Rate Today

- Petrol Rate Today

- Diesel Rate Today

- Web Stories

17 New Books Coming in April

New novels from Emily Henry, Jo Piazza and Rachel Khong; a history of five ballerinas at the Dance Theater of Harlem; Salman Rushdie’s memoir and more.

Credit... The New York Times

Supported by

- Share full article

The Cemetery of Untold Stories , by Julia Alvarez

After decades in America, a Dominican writer named Alma Cruz “retires” to a scrappy piece of real estate she’s inherited in her homeland. But a riot of stories — historical, magical, irrepressible — are still fighting to be told, so she builds a graveyard where their spirits can rise once more.

Algonquin, April 2

The Mango Tree , by Annabelle Tometich

The felony that opens Tometich’s sweet, sharp memoir sets the tone for the whole story: Her mother has been arrested for brandishing a gun at a would-be mango thief. No one is shocked — Tometich’s mother is a force of nature, and her beloved mango tree is the metaphorical center of their sometimes chaotic, often complicated family.

Little, Brown, April 2

The Sicilian Inheritance , by Jo Piazza

Twinned narratives guide the fizzy, food-y latest from Piazza: the modern-day saga of a flailing Philadelphia chef who honors the dying wish of a beloved great-aunt by journeying back to her ancestral Italian homeland, and flashbacks to the plucky great-grandmother whose battle against the constraints of early-20th-century Sicilian womanhood may have ended in her murder.

Dutton, April 2

Sociopath , by Patric Gagne

“Rules do not factor into my decision-making,” the author, a Ph.D. in psychology, writes. “I’m capable of almost anything.” Her new memoir argues that this personality type is more common, and more complicated, than we think.

Simon & Schuster, April 2

Fi , by Alexandra Fuller

In her fifth memoir, Fuller writes about the sudden, unexplained death of her 21-year-old son. She also writes about his too-short life, and explores the adage about life going on. Does it, really? And if so, how?

Grove, April 9

The Limits , by Nell Freudenberger

There’s little limit to the ambitions of Freudenberger’s hefty new novel, which skips from a small volcanic island in the South Pacific to the concrete canyons of Manhattan in a complex tale of co-parenting, second marriages, class and climate change. (Also, coral reefs.)

Knopf, April 9

Somehow , by Anne Lamott

“Thoughts on Love” is the subtitle of Lamott’s 20th book, which considers the subject in its romantic, platonic and spiritual varieties.

Riverhead, April 9

The Wide Wide Sea , by Hampton Sides

When the British naval officer James Cook set off for his voyage across the globe in 1776, his ostensible goal was to ferry Mai, a handsome and witty Tahitian man, back to Polynesia. But, as Sides shows in this vivid recounting, the leitmotif of what became Cook’s final journey was his confrontation with the dire results of his meddling in the region.

Doubleday, April 9

The Wives , by Simone Gorrindo

When Gorrindo’s husband joined an army unit and was promptly deployed overseas, the New York-based journalist was not just relocated to a base in Georgia, but to a completely new life. “The Wives” — both memoir and love letter — is a tribute to the community of women she found there, a unique source of support unlike any she had ever known.

Scout Press, April 9

Knife , by Salman Rushdie

Rushdie’s new memoir is a detailed account of the harrowing events of Aug. 12, 2022, when he was attacked onstage at a public talk. More than 30 years after the supreme leader of Iran issued a fatwa on his life, the writer turns to his craft to “make sense of the unthinkable.”

Random House, April 16

A Body Made of Glass , by Caroline Crampton

Crampton, a British journalist, weaves her own cancer diagnosis, and its cure, into this cultural history of hypochondria, which also considers such literary figures as Charles Darwin, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Philip Larkin.

Ecco, April 23

Funny Story , by Emily Henry

Henry’s latest contribution to the library of lightheartedness is a novel of opposites. What happens when spurned lovers team up against the people who hurt them? Bonus points because one character in this love square happens to be a small town librarian.

Berkley, April 23

Reboot , by Justin Taylor

This satire of modern media and pop culture follows a former child actor who is trying to revive the TV show that made him famous. Taylor delves into the worlds of online fandom while exploring the inner life of a man seeking redemption — and something meaningful to do.

Pantheon, April 23

The Demon of Unrest , by Erik Larson

Abraham Lincoln hadn’t even settled into his new job as president of the United States when the country he was narrowly elected to lead began to crack apart. Larson, a best-selling historian, traces the figures who tried to stop the American Civil War from happening in the lead-up to the attack on Fort Sumter.

Crown, April 30

A Life Impossible, by Steve Gleason and Jeff Duncan

In 2011, Steve Gleason, a former safety for the New Orleans Saints, learned that he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (A.L.S.) and was told he had three years to live. “A Life Impossible” is his memoir of marriage, fatherhood, his football career and surviving the last decade.

Knopf, April 30

Real Americans , by Rachel Khong

Khong’s sophomore novel is a tale about the evolution of one family over the course of generations. As the story opens, Lily, who is the daughter of Chinese immigrants, begins a love affair with Matthew, the wealthy son of an aristocratic family. But as Lily and her child eventually learn, their family history is more complicated than it seems.

The Swans of Harlem , by Karen Valby

In the wake of M.L.K.’s assassination, the George Balanchine protégé Arthur Mitchell felt compelled to establish a space where Black bodies could break the lily-white codes of ballet and hold center stage. And so the Dance Theater of Harlem was born — and with it, the careers of five “swans” whose journey through the cultural, political and physical tumult of the times Valby chronicles here.

Pantheon, April 30

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

James McBride’s novel sold a million copies, and he isn’t sure how he feels about that, as he considers the critical and commercial success of “The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store.”

How did gender become a scary word? Judith Butler, the theorist who got us talking about the subject , has answers.

You never know what’s going to go wrong in these graphic novels, where Circus tigers, giant spiders, shifting borders and motherhood all threaten to end life as we know it .

When the author Tommy Orange received an impassioned email from a teacher in the Bronx, he dropped everything to visit the students who inspired it.

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Advertisement

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Exclusively available on IvyPanda. 1776, which adds a new scholarship and a fresh perspective to events that took place at the start of the American Revolution, is a historical book written by David McCullough that is considered a companion to his earlier biography of John Adams. This 1776 book review essay shall analyze the story by McCullough.

1776 by David McCullough is a book about a pivotal year in the American Revolution in which the Continental Congress met in ... What are the thesis, themes, and purpose of 1776 by David McCullough

1776 Summary. Next. Chapter 1. In October of 1775, the Revolutionary War is just beginning. American "rebels" have fired on British soldiers at Lexington and Concord, and King George III of England proposes sending thousands of additional troops, including German mercenaries known as Hessians, to America to quell the uprising.

David McCullough wrote 1776 as a companion to his previous, much longer biography, John Adams (2001), about the Founding Father and second president of the United States. In John Adams, McCullough writes about the Revolutionary War from the perspective of the idealists and politicians who organized it, whereas 1776 is more focused on the soldiers and generals who fought in battle.

Right away, 1776 draws an important contrast between the two sides of the American Revolution. On one hand, the revolution is the product of Enlightenment values. The Founding Fathers, one could argue, are motivated by their philosophical commitment to the principles of freedom, democracy, and self-determination, as epitomized in the Declaration of Independence.

In a companion volume to his best-selling biography John Adams (2001), David McCullough closely examines a year of near-mythic status in the American collective memory: 1776. It was the year that ...

In Congress, July 4, 1776. The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect ...

Adam Smith was a philosopher and economic theorist born in Scotland in 1723. He's known primarily for his groundbreaking 1776 book on economics called An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the ...

Common Sense is a pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775-76 that inspired people in the Thirteen Colonies to declare and fight for independence from Great Britain in the summer of 1776. The pamphlet explained the advantages of and the need for immediate independence in clear, simple language. It was published anonymously on January 10, 1776, at the beginning of the American Revolution and ...

Part 2, Chapter 5. A violent storm breaks over New York on August 21, 1776, "and for those who saw omens in such unleashed fury from the el... Read More. Part 3, Chapter 6. In the aftermath of defeat, Joseph Reed writes to his wife that though he is alive and well, his spirits are not.

Declaration of Independence, in U.S. history, document that was approved by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and that announced the separation of 13 North American British colonies from Great Britain. It explained why the Congress on July 2 "unanimously" by the votes of 12 colonies (with New York abstaining) had resolved that "these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be ...

The U.S. Declaration of Independence, adopted July 4, 1776, was the first formal statement by a nation's people asserting the right to choose their government.

On June 18, 1776, Arnold will be the last to retreat from Canada and the still undefeated city of Montreal, then commanded by Sir Guy Carleton. On January 27, Washington will write Arnold to commiserate with him on the failure of the campaign. Arnold is commissioned a brigadier general in the Continental Army on January 10, 1776.

List of key facts related to the Declaration of Independence. This document, approved on July 4, 1776, by the Continental Congress, announced the separation of 13 North American British colonies from Great Britain. The American Revolution had gradually convinced the colonists that separation from Britain was essential.