- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

Prehistoric Era Art – Rock Paintings (Indian Culture Series – NCERT)

Last updated on September 11, 2023 by ClearIAS Team

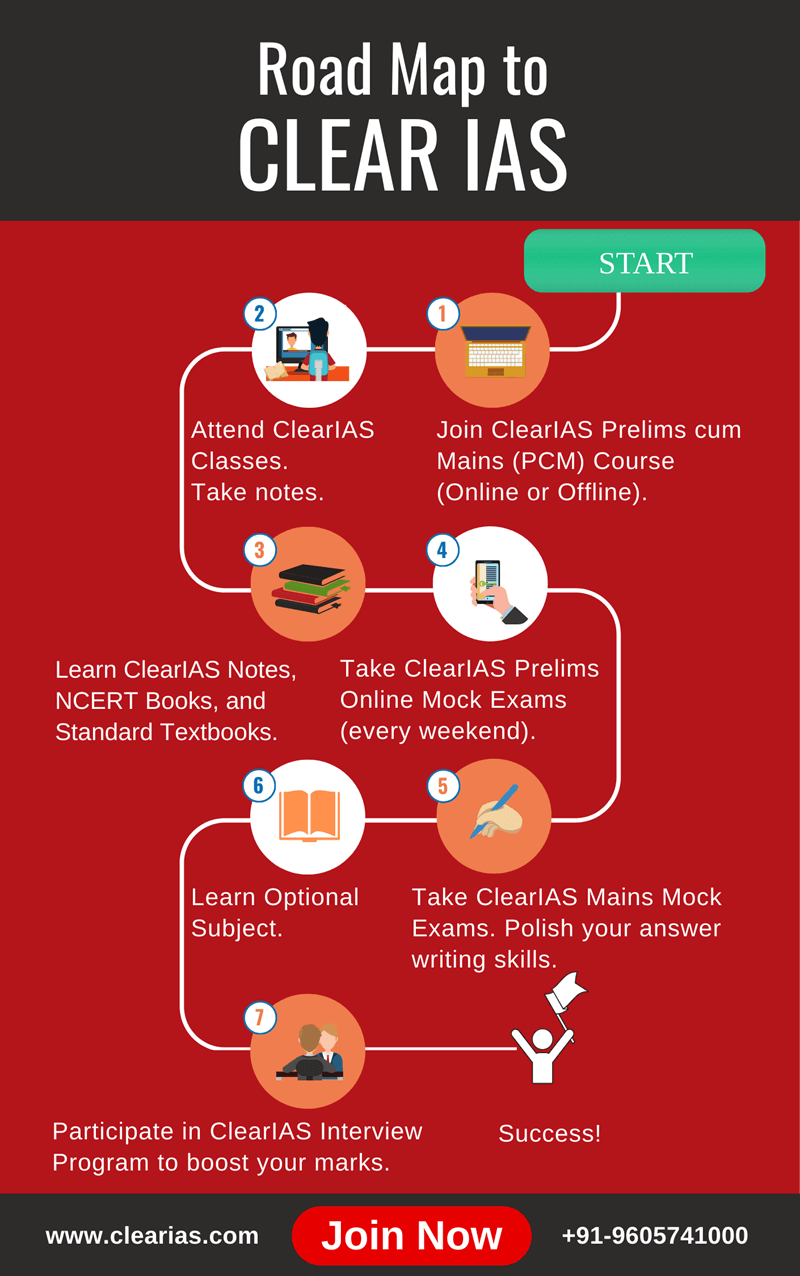

We suggest aspirants start from the book published by NCERT on Indian Culture and then move on to other online and offline sources. The book is titled ‘An Introduction to Indian Art’ – Part 1. Though many aspirants might not be aware, this textbook provides valuable knowledge for a beginner.

Clear IAS is starting a compilation of the important aspects of Indian culture based on the book ‘An Introduction to Indian Art’ – Part 1 so that aspirants can save time.

Table of Contents

What’s inside: An Introduction to Indian Art’ – Part 1

This NCERT textbook for Class XI extensively covers the tradition of cave paintings in the pre-historic era and their continuation in mural paintings of Buddhist era and later on in various parts of the country, Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu sculptural and architectural developments. During the Indo-Islamic period and before the Mughal rule, another era dawned upon India, which saw massive constructions in the form of forts and palaces. Different aspects of all these styles have been discussed to introduce students with the fabric of India’s culture. The approach is mostly chronological , and it extends from the pre-historic period till the Mughals.

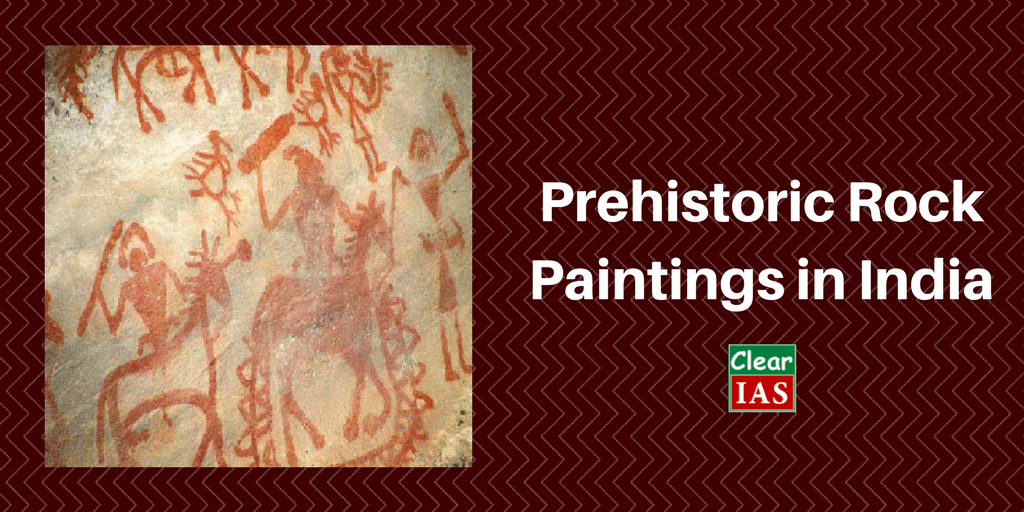

Prehistoric Rock Paintings in India

What is prehistoric?

- The distant past when there was no paper or language or the written word, and hence no books or written document, is called as the Prehistoric period.

- It was difficult to understand how Prehistoric people lived until scholars began excavations in Prehistoric sites.

- Piecing together of information deduced from old tools, habitat, bones of both animals and human beings and drawings on the cave walls scholars have constructed fairly accurate knowledge about what happened and how people lived in prehistoric times.

- Paintings and drawings were the oldest art forms practiced by human beings to express themselves using the cave wall as their canvas.

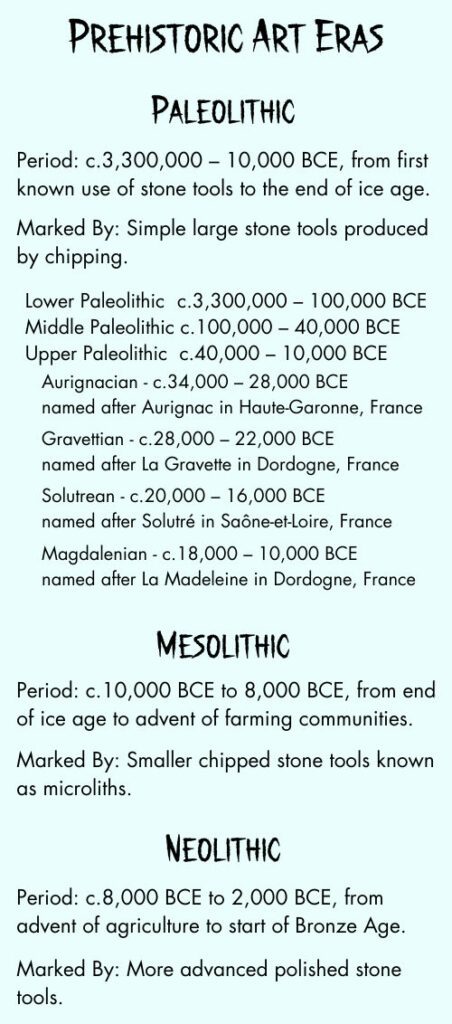

Prehistoric Period: Paleolithic Age, Mesolithic Age, and Chalcolithic Age

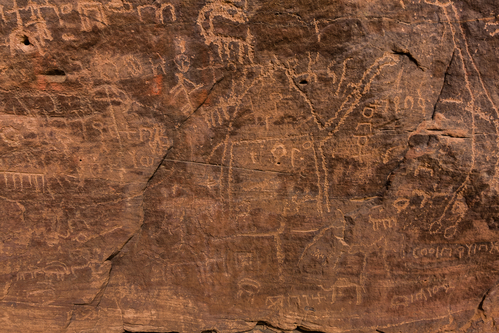

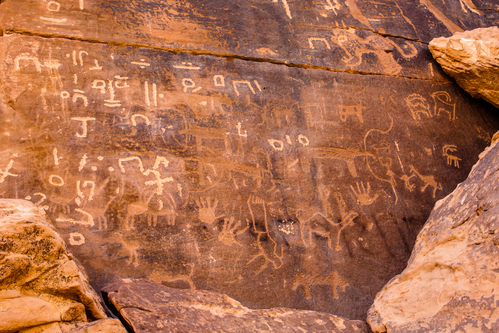

The drawings and paintings can be catagorised into seven historical periods. Period I, Upper Palaeolithic; Period II, Mesolithic; and Period III, Chalcolithic. After Period III there are four successive periods. But we will confine ourselves here only to the first three phases. Prehistoric Era art denotes the art (mainly rock paintings) during Paleolithic Age, Mesolithic Age and Chalcolithic Age.

(1) Paleolithic Age Art

- The prehistoric period in the early development of human beings is commonly known as the ‘Old Stone Age’ or ‘Palaeolithic Age’.

- The Paleolithic period can be divided into three phases: (1) Lower Palaeolithic (2.5 million years-100,000 years ago) (2) Middle Palaeolithic (300,000-30,000 years ago) (3) Upper Palaeolithic (40,000-10,000 years ago)

- We did not get any evidence of paintings from lower or middle paleolithic age yet.

- In the Upper Palaeolithic period, we see a proliferation of artistic activities.

- Subjects of early works confined to simple human figures, human activities, geometric designs, and symbols.

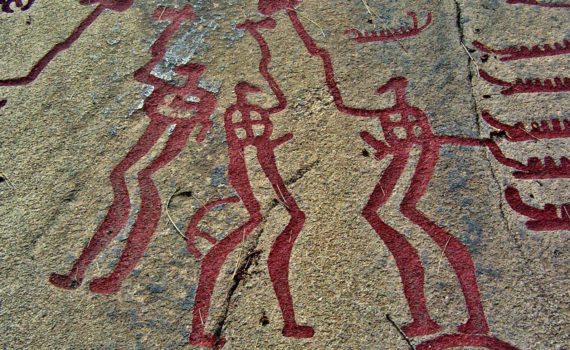

- First discovery of rock paintings in the world was made in India (1867-68) by an Archaeologist, Archibold Carlleyle , twelve years before the discovery of Altamira in Spain (site of oldest rock paintings in the world).

- In India, remnants of rock paintings have been found on the walls of caves situated in several districts of Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Bihar, and Uttarakhand.

- Some of the examples of sites early rock paintings are Lakhudiyar in Uttarakhand, Kupgallu in Telangana, Piklihal and Tekkalkotta in Karnataka, Bhimbetka and Jogimara in Madhya Pradesh etc .

- Paintings found here can be divided into three categories: Man, Animal, and Geometric symbols .

- Human beings are represented in a stick-like form.

- A long-snouted animal, a fox, a multi-legged lizard are main animal motifs in the early paintings (later many animals were drawn).

- Wavy lines, rectangular filled geometric designs and a group of dots also can be seen.

- Superimposition of paintings – earliest is Black, then red and later White.

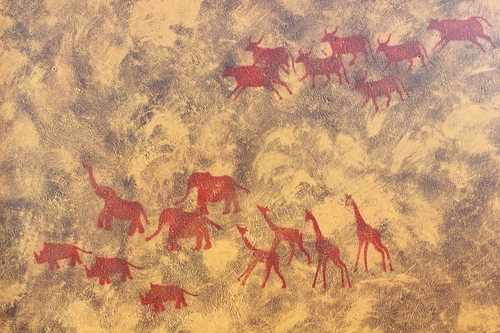

- In the late historic, early historic and Neolithic period the subjects of paintings developed and figures like Bulls, Elephants, Sambhars, Gazelles, Sheep, Horses, styled human beings, tridents and rarely vegetal motifs began to see.

- The richest paintings are reported from Vindhya range of Madhya Pradesh and their Kaimurean extension into U.P.

- These hills are fully Palaeolithic and Mesolithic remains.

- There are two major sites of excellent prehistoric paintings in India: (1) Bhimbetka Caves, Foothills of Vindhya, Madhya Pradesh. (2) Jogimara caves, Amarnath, Madhya Pradesh.

Bhimbetka Caves

Admissions Open: Join Prelims cum Mains Course 2025 Now

- Continuous occupation of the caves from 100,000 B.C– 1000 A.D

- Thus, it is considered as an evidence of long cultural continuity .

- It was discovered in 1957-58.

- Consists of nearly 400 painted rock shelters in five clusters.

- One of the oldest paintings in India and the world (Upper paleolithic). The features of paintings of three different phases are as follows (even though Bhimbetka contains many paintings of periods later, different from what is explained below, as we are dealing with the prehistoric period only, we are concluding by these three):

Upper Palaeolithic Period:

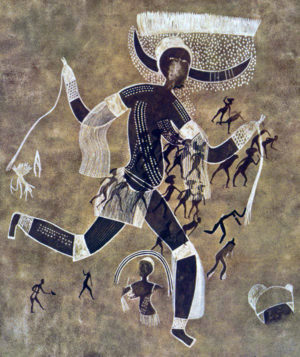

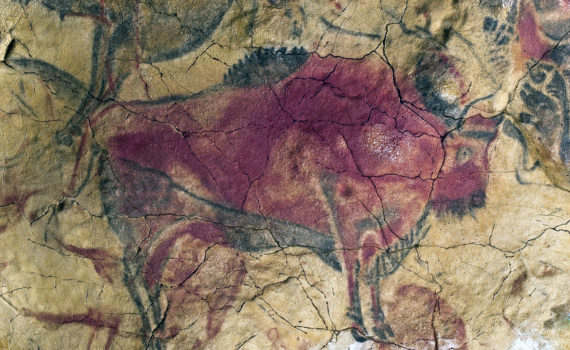

- Paintings are linear representations, in green and dark red, of huge animal figures, such as Bisons, Tigers, Elephants, Rhinos and Boars beside stick-like human figures.

- Mostly they are filled with geometric patterns.

- Green paintings are of dances and red ones of hunters.

(2) Mesolithic period Art:

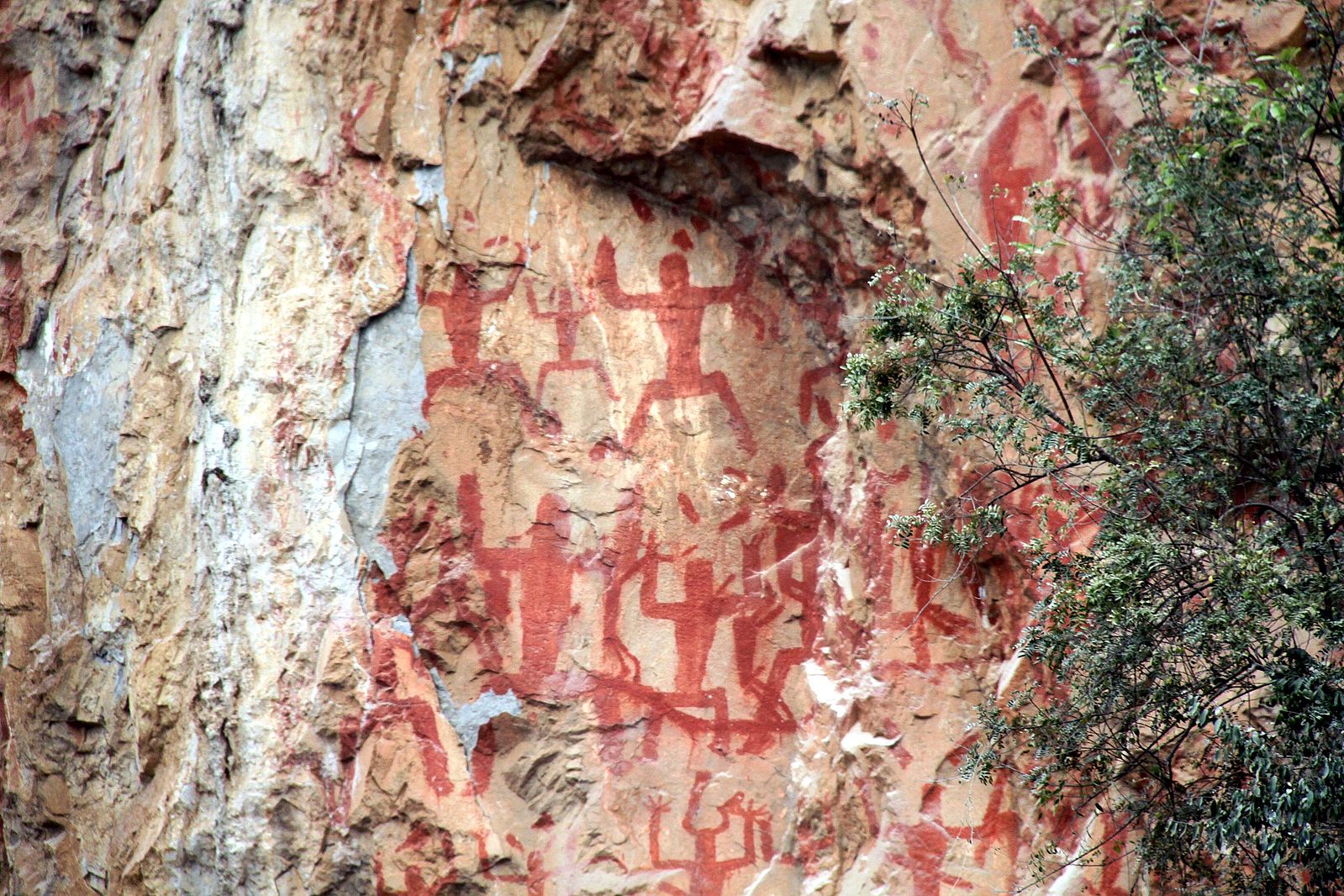

- The largest number of paintings belongs to this period.

- Themes multiply but the paintings are small in size.

- Hunting scenes predominate

- Hunters in groups armed with barbed spears pointed sticks, arrows, and bows.

- Trap and snares used to catch animals can be seen in some paintings.

- Mesolithic people loved to point animals.

- In some pictures, animals are chasing men and in others, they are being chased by hunter men.

- Animals painted in a naturalistic style and humans were depicted in a stylistic manner.

- Women are painted both in nude and clothed.

- Young and old equally find places in paintings.

- Community dances provide a common theme.

- Sort of family life can be seen in some paintings (woman, man, and children).

(3) Chalcolithic period Art:

- Copper age art.

- The paintings of this period reveal the association, contact and mutual exchange of requirements of the cave dwellers of this area with settled agricultural communities of the Malwa Plateau.

- Pottery and metal tools can be seen in paintings.

- Similarities with rock paintings: Common motifs (designs/patterns like cross-hatched squares, lattices etc)

- The difference with rock paintings: Vividness and vitality of older periods disappear from these paintings.

Some of the general features of Prehistoric paintings (based on the study of Bhimbetka paintings)

- Used colours, including various shades of white, yellow, orange, red ochre, purple, brown, green and black.

- But white and red were their favourite.

- The paints used by these people were made by grinding various coloured rocks.

- They got red from haematite (Geru in India).

- Green prepared from a green coloured rock called Chalcedony.

- White was probably from Limestone.

- Some sticky substances such as animal fat or gum or resin from trees may be used while mixing rock powder with water.

- Brushes were made of plant fiber.

- It is believed that these colours remained thousands of years because of the chemical reaction of the oxide present on the surface of rocks.

- Paintings were found both from occupied and unoccupied caves.

- It means that these paintings were sometimes used also as some sort of signals, warnings etc.

- Many rock art sites of the new painting are painted on top of an older painting.

- In Bhimbetka, we can see nearly 20 layers of paintings, one on top of another.

- It shows the gradual development of the human being from period to period.

- The symbolism is inspiration from nature along with slight spirituality.

- Expression of ideas through very few drawings (representation of men by the stick like drawings).

- Use of many geometrical patterns.

- Scenes were mainly hunting and economic and social life of people.

- The figure of flora, fauna, human, mythical creatures, carts, chariots etc can be seen.

- More importance for red and white colours.

Compiled by: Jijo Sudarshan

Aim IAS, IPS, or IFS?

About ClearIAS Team

ClearIAS is one of the most trusted learning platforms in India for UPSC preparation. Around 1 million aspirants learn from the ClearIAS every month.

Our courses and training methods are different from traditional coaching. We give special emphasis on smart work and personal mentorship. Many UPSC toppers thank ClearIAS for our role in their success.

Download the ClearIAS mobile apps now to supplement your self-study efforts with ClearIAS smart-study training.

Reader Interactions

June 22, 2015 at 10:52 pm

Very valuable

July 17, 2015 at 9:59 am

Please give advice on how many questions we can attempt safely in cs preliminary2015 GS paper since CSAT is only a qualifying one.

June 27, 2016 at 2:27 pm

65 to 70 would be good enough without negatives.

July 22, 2015 at 9:15 pm

Seriously! this helps a lot.. thanks a lot

June 20, 2016 at 9:46 am

jogimara is in Chhatisgarh. So plz give right details…

June 24, 2016 at 2:51 pm

Seriously! this helps me a lot.. thanks a lot..!!!! Ambadnya

August 12, 2016 at 6:02 pm

from which site i can download Introduction to Indian Art – PartI book

January 1, 2018 at 7:14 pm

mesolithic people loved to paint animals not point as mentioned above

October 1, 2018 at 9:50 am

Thanku sir…it’s very useful for us…good compilation…

October 25, 2018 at 11:16 pm

February 25, 2019 at 5:57 pm

very nice answer that influenced me a lot

April 24, 2021 at 10:16 pm

It said that the first discovery of rock painting was in 1967-68, but then later said bhimbetka cave was discovered in 1957-58, which crontradict the first statement. Am i misunderstanding, can anyone explain?

January 18, 2022 at 11:43 am

First painting was discovered in 1867-68 not in 1967, read the above details again.. Make sense now?

April 4, 2023 at 12:07 pm

The first discovery of rock paintings in the world was made in India by archaeologist Archibald Carlleyle in 1867 – 68 (in Sohagighat, Mirzapur District, Uttar Pradesh).

January 18, 2022 at 11:44 am

April 4, 2023 at 12:33 pm

Hello Sir/Madam, ” JOGIMARA CAVE PAINTINGS ” are in CHATTISGARH (NOT IN MADHYA PRADESH) Plz do edit…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don’t lose out without playing the right game!

Follow the ClearIAS Prelims cum Mains (PCM) Integrated Approach.

Join ClearIAS PCM Course Now

UPSC Online Preparation

- Union Public Service Commission (UPSC)

- Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

- Indian Police Service (IPS)

- IAS Exam Eligibility

- UPSC Free Study Materials

- UPSC Exam Guidance

- UPSC Prelims Test Series

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Prelims

- UPSC Interview

- UPSC Toppers

- UPSC Previous Year Qns

- UPSC Age Calculator

- UPSC Calendar 2024

- About ClearIAS

- ClearIAS Programs

- ClearIAS Fee Structure

- IAS Coaching

- UPSC Coaching

- UPSC Online Coaching

- ClearIAS Blog

- Important Updates

- Announcements

- Book Review

- ClearIAS App

- Work with us

- Advertise with us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Talk to Your Mentor

Featured on

and many more...

- IAS Preparation

- UPSC Preparation Strategy

- Prehistoric Rock Paintings

NCERT Notes: Prehistoric Rock Paintings

NCERT notes on important topics for the UPSC civil services exam preparation. These notes will also be useful for other competitive exams like bank PO, SSC, state civil services exams and so on .

Prehistoric Rock Paintings (UPSC Notes):- Download PDF Here

- Prehistory: The time period in the past when there was no paper or the written word and hence no books or written accounts of events. Information about such an age is obtained from excavations which reveal paintings, pottery, habitat, etc.

- Drawings and paintings were the oldest form of artistic expression practised by humans. Reasons for such drawings: Either to decorate their homes or/and to keep a journal of events in their lives.

- Lower and Middle Palaeolithic Periods have not shown any evidence of artworks so far. The Upper Palaeolithic Age shows a lot of artistic activities.

- Earliest paintings in India are from the Upper Palaeolithic Age.

- The first discovery of rock paintings in the world was made in India by archaeologist Archibald Carlleyle in 1867 – 68 (in Sohagighat, Mirzapur District, Uttar Pradesh).

- Rock paintings have been found in the walls of caves at Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Karnataka, some in the Kumaon Hills of Uttarakhand.

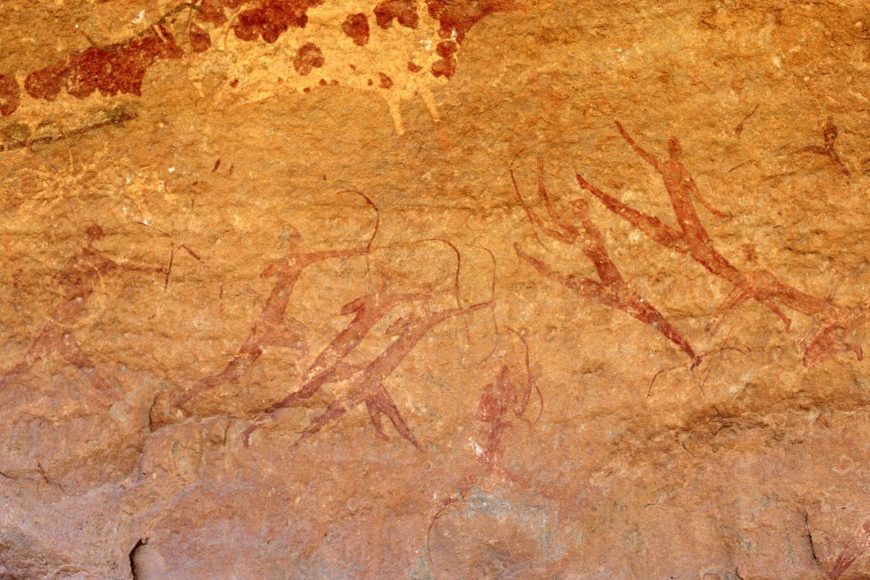

- Paintings at the rock shelters at Lakhudiyar on the banks of the Suyal River (Uttarakhand) –

- 3 categories of paintings: man, animal and geometric patterns in black, white and red ochre.

- Humans in stick-like forms, a long-snouted animal, a fox, a multiple-legged lizard, wavy lines, groups of dots and rectangle-filled geometric designs, hand-linked dancing humans.

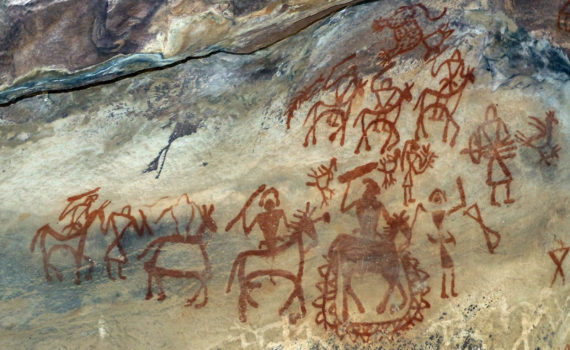

- Paintings in Kupgallu (Telangana), Piklihal and Tekkalkota (both in Karnataka)

- Mostly in white and red ochre.

- Subjects are bulls, sambhars, elephants, sheep, gazelles, goats, horses, stylised humans and tridents.

- Paintings in the Vindhya ranges at Madhya Pradesh extending into Uttar Pradesh –

- About 500 rock shelters at Bhimbetka in the Vindhya Hills at Madhya Pradesh.

- Images of hunting, dancing, music, elephant and horse riders, honey collection, animal fighting, decoration of bodies, household scenes, etc.

- Period I: Upper Palaeolithic

- Period II: Mesolithic

- Period III: Chalcolithic

- Two major sites of prehistoric rock/cave paintings in India: Bhimbetka Caves and Jogimara Caves (Amarnath, Madhya Pradesh).

- Continuous occupation of these caves from 100000 BC to 1000 AD.

- Discovered by archaeologist V S Wakankar in 1957 – 58.

- One of the oldest paintings in India and the world.

- Period I (Upper Palaeolithic)

- Linear representations of animals like bison, tigers, elephants, rhinos and boars; stick-like human figures.

- Paintings in green and dark red. Green paintings are of dancers and red ones are of hunters.

- Period II (Mesolithic)

- The largest number of paintings in this period.

- More themes but paintings reduce in size.

- Mostly hunting scenes – people hunting in groups with barbed spears, arrows and bows, and pointed sticks. Also, show traps and snares to catch animals.

- Hunters wear simple clothes; some men are shown with headdresses and masks. Women have been shown both clothed and in the nude.

- Animals seen – elephants, bisons, bears, tigers, deer, antelopes, leopards, panthers, rhinos, frogs, lizards, fish, squirrels and birds.

- Children are seen playing and jumping. Some scenes depict family life.

- Period III (Chalcolithic)

- Paintings indicate an association of these cave-dwellers with the agricultural communities settled at Malwa.

- Cross-hatched squares, lattices, pottery and metal tools are depicted.

- Colours used in Bhimbetka paintings – white, yellow, orange, red ochre, purple, brown, green and black. Most common colours – white and red.

- Red obtained from haematite (geru); green from chalcedony; white probably from limestone.

- Brushes were made from plant fibre.

- In some places, there are many layers of paintings, sometimes 20.

- Paintings can be seen in caves that were used as dwelling places and also in caves that had some other purpose, perhaps religious.

- The colours of the paintings have remained intact thousands of years perhaps due to the chemical reaction of the oxide present on the rock surface.

Also, See | NCERT Notes for UPSC Exams – Prehistoric age in India

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

Please give me important notes about current affairs

Current Affairs

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

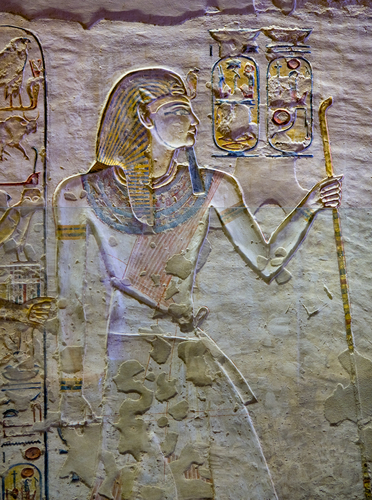

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Introduction to prehistoric art, 20,000–8000 b.c..

Laura Anne Tedesco Independent Scholar

August 2007

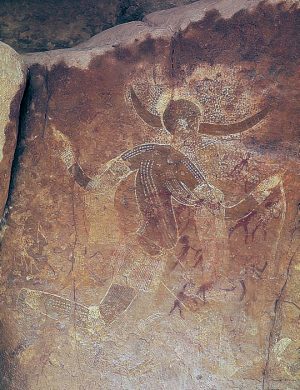

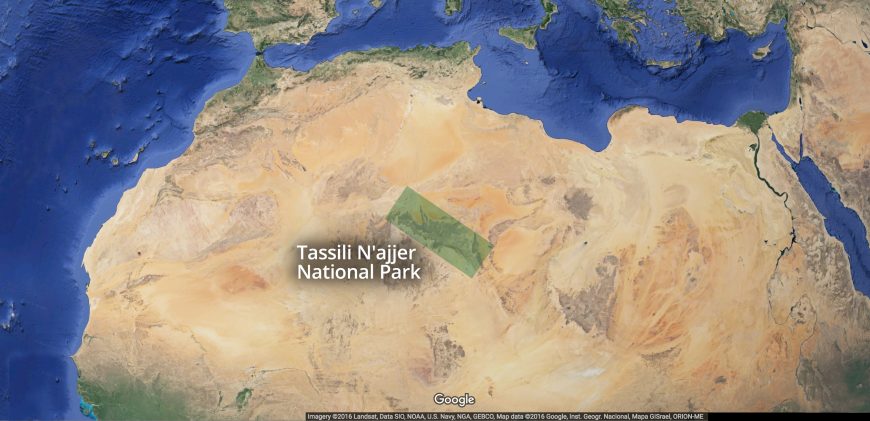

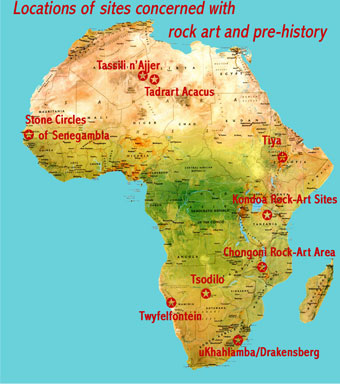

To describe the global origins of humans’ artistic achievement, upon which the succeeding history of art may be laid, is an encyclopedic enterprise. The Metropolitan Museum’s Timeline of Art History , covering the period roughly from 20,000 to 8000 B.C., provides a series of introductory essays about particular archaeological sites and artworks that illustrate some of the earliest endeavors in human creativity. The account of the origins of art is a very long one marked less by change than consistency. The first human artistic representations, markings with ground red ocher, seem to have occurred about 100,000 B.C. in African rock art . This chronology may be more an artifact of the limitations of archaeological evidence than a true picture of when humans first created art. However, with new technologies, research methods, and archaeological discoveries, we are able to view the history of human artistic achievement in a greater focus than ever before.

Art, as the product of human creativity and imagination, includes poetry, music, dance, and the material arts such as painting, sculpture, drawing, pottery, and bodily adornment. The objects and archaeological sites presented in the Museum’s Timeline of Art History for the time period 20,000–8000 B.C. illustrate diverse examples of prehistoric art from across the globe. All were created in the period before the invention of formal writing, and when human populations were migrating and expanding across the world. By 20,000 B.C., humans had settled on every continent except Antarctica. The earliest human occupation occurs in Africa, and it is there that we assume art to have originated. African rock art from the Apollo 11 and Wonderwerk Caves contain examples of geometric and animal representations engraved and painted on stone. In Europe, the record of Paleolithic art is beautifully illustrated with the magnificent painted caves of Lascaux and Chauvet , both in France. Scores of painted caves exist in western Europe, mostly in France and Spain, and hundreds of sculptures and engravings depicting humans, animals, and fantastic creatures have been found across Europe and Asia alike. Rock art in Australia represents the longest continuously practiced artistic tradition in the world. The site of Ubirr in northern Australia contains exceptional examples of Aboriginal rock art repainted for millennia beginning perhaps as early as 40,000 B.C. The earliest known rock art in Australia predates European painted caves by as much as 10,000 years.

In Egypt, millennia before the advent of powerful dynasties and wealth-laden tombs, early settlements are known from modest scatters of stone tools and animal bones at such sites as Wadi Kubbaniya . In western Asia after 8,000 B.C., the earliest known writing , monumental art, cities , and complex social systems emerged. Prior to these far-reaching developments of civilization, this area was inhabited by early hunters and farmers. Eynan/Ain Mallaha , a settlement in the Levant along the Mediterranean, was occupied around 10,000–8000 B.C. by a culture named Natufian. This group of settled hunters and gatherers created a rich artistic record of sculpture made from stone and bodily adornment made from shell and bone.

The earliest art of the continent of South Asia is less well documented than that of Europe and western Asia, and some of the extant examples come from painted and engraved cave sites such as Pachmari Hills in India. The caves depict the region’s fauna and hunting practices of the Mesolithic period. In Central and East Asia, a territory almost twice the size of North America, there are outstanding examples of early artistic achievements, such as the expertly and delicately carved female figurine sculpture from Mal’ta . The superbly preserved bone flutes from the site of Jiahu in China, while dated to slightly later than 8000 B.C., are still playable. The tradition of music making may be among the earliest forms of human artistic endeavor. Because many musical instruments were crafted from easily degradable materials like leather, wood, and sinew, they are often lost to archaeologists, but flutes made of bone dating to the Paleolithic period in Europe (ca. 35,000–10,000 B.C.) are richly documented.

North and South America are the most recent continents to be explored and occupied by humans, who likely arrived from Asia. Blackwater Draw in North America and Fell’s Cave in Patagonia, the southernmost area of South America, are two contemporaneous sites where elegant stone tools that helped sustain the hunters who occupied these regions have been found.

Whether the prehistoric artworks illustrated here constitute demonstrations of a unified artistic idiom shared by humankind or, alternatively, are unique to the environments, cultures, and individuals who created them is a question open for consideration. Nonetheless, each work or site superbly characterizes some of the earliest examples of humans’ creative and artistic capacity.

Tedesco, Laura Anne. “Introduction to Prehistoric Art, 20,000–8000 B.C.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/preh/hd_preh.htm (August 2007)

Further Reading

Price, T. Douglas. and Gary M. Feinman. Images of the Past . 5th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2006.

Scarre, Chris, ed. The Human Past: World Prehistory & the Development of Human Societies . London: Thames & Hudson, 2005.

Additional Essays by Laura Anne Tedesco

- Tedesco, Laura Anne. “ Blackwater Draw (ca. 9500–3000 B.C.) .” (originally published October 2000, last revised September 2007)

- Tedesco, Laura Anne. “ Wadi Kubbaniya (ca. 17,000–15,000 B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Tedesco, Laura Anne. “ Fell’s Cave (9000–8000 B.C.) .” (originally published October 2000, last revised September 2007)

- Tedesco, Laura Anne. “ Jiahu (ca. 7000–5700 B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Tedesco, Laura Anne. “ Lascaux (ca. 15,000 B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Tedesco, Laura Anne. “ Mal’ta (ca. 20,000 B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Tedesco, Laura Anne. “ Pachmari Hills (ca. 9000–3000 B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Tedesco, Laura Anne. “ Hasanlu in the Iron Age .” (October 2004)

- Tedesco, Laura Anne. “ Eynan/Ain Mallaha (12,500–10,000 B.C.) .” (October 2000; updated February 2024)

Related Essays

- African Rock Art

- Chauvet Cave (ca. 30,000 B.C.)

- Lascaux (ca. 15,000 B.C.)

- Neolithic Period in China

- Prehistoric Stone Sculpture from New Guinea

- African Rock Art: Game Pass

- African Rock Art: Tassili-n-Ajjer (?8000 B.C.–?)

- African Rock Art: The Coldstream Stone

- Apollo 11 (ca. 25,500–23,500 B.C.) and Wonderwerk (ca. 8000 B.C.) Cave Stones

- Blackwater Draw (ca. 9500–3000 B.C.)

- Cerro Sechín

- Cerro Sechín: Stone Sculpture

- Eynan/Ain Mallaha (12,500–10,000 B.C.)

- Fell’s Cave (9000–8000 B.C.)

- Indian Knoll (3000–2000 B.C.)

- Jiahu (ca. 7000–5700 B.C.)

- Jōmon Culture (ca. 10,500–ca. 300 B.C.)

- Mal’ta (ca. 20,000 B.C.)

- Pachmari Hills (ca. 9000–3000 B.C.)

- Ubirr (ca. 40,000?–present)

- Valdivia Figurines

- Wadi Kubbaniya (ca. 17,000–15,000 B.C.)

- X-ray Style in Arnhem Land Rock Art

- 8th Millennium B.C.

- Agriculture

- Archaeology

- Central and North Asia

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Iberian Peninsula

- Literature / Poetry

- Musical Instrument

- Mythical Creature

- North Africa

- North America

- Painted Object

- Personal Ornament

- Prehistoric Art

- Relief Sculpture

- Sculpture in the Round

- South America

- Wall Painting

- Wind Instrument

Human Relations Area Files

Cultural information for education and research, an introduction to rock art.

Jeffrey Vadala

Figure 1. Aerial view of monkey earth figure, etched into the Nazca Desert sand, Peru. By Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia.

Often considered evidence of humanity’s first artistry, prehistoric rock art has captivated people all over the world. Associated with many different cultures, the meaning and purpose of most forms of prehistoric rock art remain shrouded in mystery. Even the most experienced archaeologists continue to ask basic questions about rock art. What does it depict? What does it mean? Who produced it? When was it produced? What function did it serve?

Here, using eHRAF Archaeology and other sources, I will explore some examples of prehistoric rock art while demonstrating how scholars have attempted to understand the ancient people that produced these mysterious markers of human artistry and creativity.

Defining Rock Art

Most simply put, rock art is artwork done on natural rock surfaces. This means it can be found on the sides or walls of caves, cliffs, sheer standing rocks, and also boulders. Most of the rock art that I encountered while doing an archaeological survey in Southern California was located on the sides of massive granite boulders (for example, see Figure 2). Rock art may also be referred to as “rock carvings,” “rock engravings,” “rock drawings,” and “rock paintings.” There are three categories of rock art that have been studied and defined by archaeologists since a systematic study of rock art began. These include petroglyphs (carved rock art), pictographs (painted rock art), and earth figures (large surface scrapings).

Petroglyphs

The first of these categories is petroglyphs. This category contains all rock art that is considered to be rock engravings or carvings. For this type, a rock’s surface is carved or removed in specific patterns using a hammerstone. This tool is used to peck or hammer artistic details into the surface of a boulder, cave wall, or another natural stone surface. Alternatively, rather than using a hammerstone directly, a hammerstone can be used in tandem with a smaller chisel stone to produce finer details (Whitley 2005). The Hemet Maze Stone pictured below was most likely carved using the latter of these two methods.

Figure 2. The Helmet Maze Stone (a petrogylph) in Southern California. By Devin Sean Cooper, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia.

A commonly found, less complex form of petroglyph is a cupule. A cupule is a simple carving that looks like a cup-shaped hole in the side of a rock surface. Dating to the stone age or earlier, cupules are found all over the world. Many consider them to be the oldest form of rock art. Although they look simple, it is thought that cupules can express ritual or symbolic meaning. In the area near where the Maze stone was found, during several archaeological surveys, my team and I discovered many cupules on large boulders in the area. At one site, a large granite boulder was covered in hundreds of cupules. Given the amount of time carving granite takes, one can easily see how the cupules represent hours and hours of dedication. Why would the native people in this region spend so much time carving cupules all on one boulder?

Although the precise meaning cannot be determined, it has been theorized that they were carved during coming-of-age ceremonies (Hedges 1976:17). Over time, ritual practitioners would have noted that these cupules accumulated. Eventually an accumulation of cupules could come to represent a history of ritual action–a local record of ritual events over time.

Another, rarer form of petroglyph is created through incision or scratching rather than carving or chiseling, with tools like lithic obsidian blades. Given that obsidian blades have fine edges, smaller fine-grained details can be made upon rock surfaces using this method. That said, because such carvings are not very deep and rock surfaces erode over time, this form is often difficult for archaeologists to identify (Whitley 2005).

Pictographs

Figure 3. Negative hand paintings at Gargas caves in France. By José-Manuel Benito. Public Domain.

Pictographs, painted artwork on stone surfaces, are often regarded as the most beautiful rock art. Like the other forms of rock art, pictographs are found worldwide and date deep into the human past. The pigments used to make pictograph paints are ochres, charcoal, ground minerals, natural chalk, kaolinite clays, and even diatomaceous earth. Usually, these substances are mixed with liquids like water, eggs, and blood to make red, black, and white paints. Brushes, stamps, hands and fingers were used to apply these paints to rock surfaces (Whitley 2005). One of the most famous and well-known types of pictographs is the “handprint” type that is found at the Gargas caves in southern France. These paintings date to about 25,000 BCE. At the Gargas caves, the pictographs are negative prints that were created using the human hand as a stencil. A person would put their hand against the rock wall and spit or blow pigment through a bone tube creating a negative image or outline of the hand (Whitley 2005).

Figure 4. Low-relief petroglyph “El Rey” at Chalcatzingo. By Maunus, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia.

Pictographs and petroglyphs can be found together in close proximity. This is the case at the Mesoamerican site of Chalcatzingo. This site is well known for its petroglyphs that are often described as low-reliefs, yet it also has a number of pictographs at the site and nearby. The low-reliefs have been interpreted to be representations of cosmological ideas. More specifically, they represent cycles of nature, fertility, celestial beings, and beliefs about sacred relationships found in nature (Angulo 1987:155). Studied by Alex Apostolides (1987), the pictographs are simpler but harder to correlate with other site activities. The pictographs include “stick figures,” a “triangle and slit” design, a “sunburst,” “plumes,” and spirals. These design elements are combined and found at many places around the site. This includes caves, niches, and rock walls. Apostolides (1987) attempted to characterize patterns in the pictographs grouping them by location, color, and symbols but reached no major conclusions regarding the meaning or function of the artwork. This is because the pictographs were impossible to affirmatively date and often ambiguous in terms of their general form. More recently Julio Amador (2018) has argued that some of these pictographs represent water and or serpent imagery.

Earth Figures

“Earth figure” rock art is created by scraping large pictures or symbols into the surface of the earth. The Nazca lines are probably the most famous of this third category of rock art (see Figure 1). Scraped from the Peruvian desert floor, these massive forms of art have inspired many studies, theories, interpretations, and conspiracies because of their size and because they appear to be made to view from the sky. Today, most scholars agree that the lines were created by systematically removing dark desert top floor minerals which exposed the light soils beneath. Detailing how they look from the sky, astronomer Anthony Aveni (1990) wrote, “from an airplane, the markings appear as a tangled mass overlapping and intersecting one another, rather like the remains of an unerased blackboard at the end of a busy day of classroom activities.” Although many theories pointed to astronomical uses of the Nazca lines, Aveni (1990) found no evidence to support astronomical uses. Aveni speculated that rather than use the lines for astronomy, the Nazca may have used the lines as special ritual paths: “Perhaps one ought to sense the monkey or the hummingbird [shape] not by seeing it from the air, but rather by walking (or running) upon it. Thus one would perceive with the body every sinuous turn in the labyrinthine tail or the delicate curvature of each individual fragment of avian plumage.” Yet, in the early 2000s scholars found another clue as to the use of the lines. David Johnson and colleagues found that the lines may follow important water aquifers in the parched desert (Johnson et al. 2002). Most recently, Italian scholars have argued the lines serve special ritual functions related to calendric events at the nearby temples of Cahuachi (Masini et al. 2016).

There is still no real consensus to the use or meaning of Nazca lines. In many cases around the world, the meaning and function of famous examples of rock art continue to be debated and explored with no end in sight. Using eHRAF Archaeology , scholars can study rock art cross-culturally to find potential answers. Patterns in rock art could be defined and used to solve the mysteries of this most ancient form of human creativity.

Amador, Julio. 2018. Rock art at Chalcatzingo, Morelos: Methodology and Techniques for Recording Documenting and Elaborating Preservation Strategies. Conference Paper. The 82nd Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology

Angulo V., Jorge. 1987. “Chalcatzingo Reliefs: An Iconographic Analysis.” Ancient Chalcatzingo. Austin: University of Texas Press. https://ehrafarchaeology.yale.edu/document?id=nu95-013 .

Apostolides, Alex. 1987. “Chalcatzingo Painted Art.” Ancient Chalcatzingo. Austin: University of Texas Press. https://ehrafarchaeology.yale.edu/document?id=nu92-013 .

Aveni, Anthony F. 1990. “Assessment Of Previous Studies Of The Nazca Glyphs.” Lines Of Nazca. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. https://ehrafarchaeology.yale.edu/document?id=se51-007.

Hedges, Ken 1976. Roct Art at Hakwin: A Preliminary Report. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 12(1):9-20.

Johnson, D. W., Proulx. D. A., Mabee, S. B. 2002. The correlation between geoglyphs and subterranean water resources in the Rio Grande de Nasca drainage. In Silvermann H. & Isbell W. H. (Ed.), Andean Archaeology II: art, landscape, and society. New York, Kluwer Academic, pp. 307–332.

Masini, Nicola, Orefici, Giuseppe, Danese, M., Pecci, A., Scavone, M., Lasaponara, R. 2016. Cahuachi and Pampa de Atarco: Towards Greater Comprehension of Nasca Geoglyphs. In: Lasaponara R., Masini N., Orefici G. (Eds). The Ancient Nasca World New Insights from Science and Archaeology. Springer International Publishing, pp. 239–278.

Whitley, David S. (2005). Introduction to Rock Art Research. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press. ISBN 978-1598740004.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: Prehistoric Art

Introduction to prehistoric art.

The term Prehistory refers to all of human history that precedes the invention of writing systems (c. 3100 B.C.E.) and the keeping of written records, and it is an immensely long period of time, some ten million years according to current theories. For the purposes of an art history survey, we split our study of Prehistory into two broad periods: Paleolithic and Neolithic (from the Greek “ palaios ” (old) / “ neos ” (new) and “ lithos ” (stone), as these peoples worked with stone tools).

The timeline covered in this area of the survey is vast —c. 32,000 B.C.E. (Chauvet Caves) to 2,000 B.C.E. (Neolithic settlements)—but the question that unites this vast chronology is simple and compelling: what can we find out about objects and the people who made them and how do they connect to our contemporary experiences today? Geography also is vast – these periods existed on all inhabitable continents, although the chronology is not the same. Early humans arrived in the Americas much later.

Common questions about dates

B.C. or B.C.E.?

Many people use the abbreviations B.C. and A.D. with a year (for example, A.D. 2012). B.C. refers to “Before Christ,” and the initials, A.D., stand for Anno Domini , which is Latin for “In the year of our Lord.” This system was devised by a monk in the year 525.

A more recent system uses B.C.E. which stands for “Before the Common Era” and C.E. for “Common Era.” This newer system is now widely used as a way of expressing the same periods as B.C. and A.D., but without the Christian reference. According to these systems, we count time backwards Before the Common Era (B.C.E.) and forwards in the Common Era (C.E.).

Often dates will be preceded with a “c.” or a “ca.” These are abbreviations of the Latin word “circa” which means around, or approximately. We use this before a date to indicate that we do not know exactly when so mething happened, so c. 400 B.C.E. means approximately 400 years Before the Common Era.

Terms to know

The Paleolithic Age

The Paleolithic Art, or Old Stone Age, spanned from around 30,000 BCE until 10,000 BCE and produced the first accomplishments in human creativity. Due to a lack of written records from this time period, nearly all of our knowledge of Paleolithic human culture and way of life comes from archaeologic and ethnographic comparisons to modern hunter-gatherer cultures. The Paleolithic lasted until the retreat of the ice, when farming and the use of metals were adopted.

A typical Paleolithic society followed a hunter-gatherer economy. Humans hunted wild animals for meat and gathered food, firewood, and materials for their tools, clothes, or shelters. The adoption of both technologies—clothing and shelter—can not be dated exactly, but they were key to humanity’s progress. As the Paleolithic era progressed, dwellings became more sophisticated, more elaborate, and more house-like. At the end of the Paleolithic era, humans began to produce works of art such as cave paintings, rock art, and jewelry, and began to engage in religious behavior such as burial and rituals.

Dwellings and Shelters

The oldest examples of Paleolithic dwellings are shelters in caves, followed by houses of wood, straw, and rock. Early humans chose locations that could be defended against predators and rivals and that were shielded from inclement weather. Many such locations could be found near rivers, lakes, and streams, perhaps with low hilltops nearby that could serve as refuges. Since water can erode and change landscapes quite drastically, many of these campsites have been destroyed. Our understanding of Paleolithic dwellings is therefore limited.

As early as 380,000 BCE, humans were constructing temporary wood huts. Other types of houses existed; these were more frequently campsites in caves or in the open air with little in the way of formal structure. The oldest examples are shelters within caves, followed by houses of wood, straw, and rock. A few examples exist of houses built out of bones.

Caves are the most famous example of Paleolithic shelters, though the number of caves used by Paleolithic people is drastically small relative to the number of hominids thought to have lived on Earth at the time. Most hominids probably never entered a cave, much less lived in one. Nonetheless, the remains of hominid settlements show interesting patterns. In one cave, a tribe of Neanderthals kept a hearth fire burning for a thousand years, leaving behind an accumulation of coals and ash. In another cave, post holes in the dirt floor reveal that the residents built some sort of shelter or enclosure with a roof to protect themselves from water dripping on them from the cave ceiling. They often used the rear portions of the cave as middens, depositing their garbage there. In the Upper Paleolithic (the latest part of the Paleolithic), caves ceased to act as houses. Instead, they likely became places for early people to gather for ritual and religious purposes.

Tents and Huts

Modern archaeologists know of few types of shelter used by ancient peoples other than caves. Some examples do exist, but they are quite rare. In Siberia, a group of Russian scientists uncovered a house or tent with a frame constructed of mammoth bones. The great tusks supported the roof, while the skulls and thighbones formed the walls of the tent. Several families could live inside, where three small hearths, little more than rings of stones, kept people warm during the winter. Around 50,000 years ago, a group of Paleolithic humans camped on a lakeshore in southern France. At Terra Amata, these hunter-gatherers built a long and narrow house. The foundation was a ring of stones, with a flat threshold stone for a door at either end. Vertical posts down the middle of the house supported roofs and walls of sticks and twigs, probably covered over with a layer of straw. A hearth outside served as the kitchen, while a smaller hearth inside kept people warm. Their residents could easily abandon both dwellings. This is why they are not considered true houses, which were a development of the Neolithic period rather than the Paleolithic period.

Paleolithic Artifacts

The Paleolithic is separated into three periods: the Lower Paleolithic (the earliest subdivision), Middle Paleolithic, and Upper Paleolithic. The Paleolithic era is characterized by the use of stone tools, although at the time humans also used wood and bone tools. Other organic commodities were adapted for use as tools, including leather and vegetable fibres; however, due to their nature, these have not been preserved to any great degree. The Paleolithic era has a number of artifacts that range from stone, bone, and wood tools to stone sculptures.

The earliest undisputed art originated in the Upper Paleolithic. However, there is some evidence that a preference for aesthetics emerged in the Middle Paleolithic due to the symmetry inherent in discovered artifacts and evidence of attention to detail in such things as tool shape, which has led some archaeologists to interpret these artifacts as early examples of artistic expression. There has been much dispute among scholars over the terming of early prehistoric artifacts as “art.” Generally speaking, artifacts dating from the Lower and Middle Paleolithic remain disputed as objects of artistic expression, while the Upper Paleolithic provides the first conclusive examples of art-making.

Our earliest technology?

Handaxe, lower paleolithic, about 1.8 million years old, hard green volcanic lava (phonolite), 23.8 x 10 cm, found at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, Africa © The Trustees of the British Museum

Made nearly two million years ago, stone tools such as this are the first known technological invention.

This chopping tool and others like it are the oldest objects in the British Museum. It comes from an early human campsite in the bottom layer of deposits in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Potassium-argon dating indicates that this bed is between 1.6 and 2.2 million years old from top to bottom. This and other tools are dated to about 1.8 million years.

Using another hard stone as a hammer, the maker has knocked flakes off both sides of a basalt (volcanic lava) pebble so that they intersect to form a sharp edge. This could be used to chop branches from trees, cut meat from large animals or smash bones for marrow fat—an essential part of the early human diet. The flakes could also have been used as small knives for light duty tasks.

Deliberate shaping

To some people this artifact might appear crude; how can we even be certain that it is humanly made and not just bashed in rock falls or by trampling animals? A close look reveals that the edge is formed by a deliberate sequence of skillfully placed blows of more or less uniform force. Many objects of the same type, made in the same way, occur in groups called assemblages which are occasionally associated with early human remains. By contrast, natural forces strike randomly and with variable force; no pattern, purpose or uniformity can be seen in the modifications they cause.

Chopping tools and flakes from the earliest African sites were referred to as Oldowan by the archaeologist Louis Leakey. He found this example on his first expedition to Olduvai in 1931, when he was sponsored by the British Museum.

Handaxes were still in use there some 500,000 years ago by which time their manufacture and use had spread throughout Africa, south Asia, the Middle East and Europe where they were still being made 40,000 years ago. They have even been found as far east as Korea in recent excavations. No other cultural artifact is known to have been made for such a long time across such a huge geographical range.

Handaxes are always made from stone and were held in the hand during use. Many have this characteristic teardrop or pear shape which might have been inspired by the outline of the human hand.

The beginnings of an artistic sense?

Although handaxes were used for a variety of everyday tasks including all aspects of skinning and butchering an animal or working other materials such as wood, this example is much bigger than the usual useful size of such hand held tools. Despite its symmetry and regular edges it appears difficult to use easily. As language began to develop along with tool making, was this handaxe made to suggest ideas? Does the care and craftsmanship with which it was made indicate the beginnings of the artistic sense unique to humans?

Rock art and the origins of art in Africa

Genetic and fossil evidence tells us that Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans who evolved from an earlier species of hominids) developed on the continent of Africa more than 100,000 years ago and spread throughout the world. But what we do not know—what we have only been able to assume—is that art too began in Africa. Is Africa, where humanity originated, home to the world’s oldest art? If so, can we say that art began in Africa?

The first examples of what we might term “art” in Africa, dating from between 100,000–60,000 years ago, emerge in two very distinct forms: personal adornment in the form of perforated seashells suspended on twine, and incised and engraved stone, ochre and ostrich eggshell. Despite some sites being 8,000 km and 40,000 years apart, an intriguing feature of the earliest art is that these first forays appear remarkably similar. It is worth noting here that the term “art” in this context is highly problematic, in that we cannot assume that humans living 100,000 years ago, or even 10,000 years ago, had a concept of art in the same way that we do, particularly in the modern Western sense. However, it remains a useful umbrella term for our purposes here.

Pattern and design

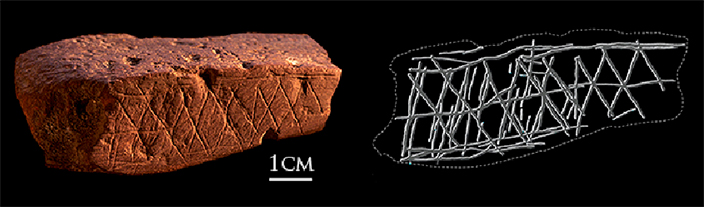

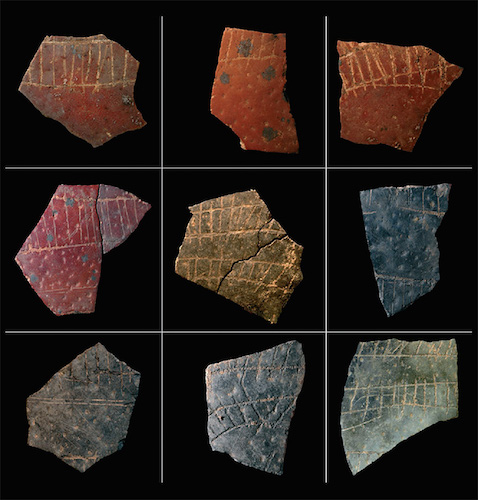

The practice of engraving or incising, which emerges around 12,000 years ago in Saharan rock art, has its antecedents much earlier, up to 100,000 years ago. Incised and engraved stone, bone, ochre and ostrich eggshell have been found at sites in southern Africa. These marked objects share features in the expression of design, exhibiting patterns that have been classified as cross-hatching.

One of the most iconic and well-publicized sites that have yielded cross-hatch incised patterning on ochre is Blombos Cave, on the southern Cape shore of South Africa. Of the more than 8,500 fragments of ochre deriving from the MSA (Middle Stone Age) levels, 15 fragments show evidence of engraving. Two of these, dated to 77,000 years ago, have received the most attention for the design of cross-hatch pattern.

Incised ochre from Blombos Cave, South Africa. Photo by Chris. S. Henshilwood © Chris. S. Henshilwood

For many archaeologists, the incised pieces of ochre at Blombos are the most complex and best-formed evidence for early abstract representations, and are unequivocal evidence for symbolic thought and language. The debate about when we became a symbolic species and acquired fully syntactical language—what archaeologists term ‘modern human behaviour’—is both complex and contested. It has been proposed that these cross-hatch patterns are clear evidence of thinking symbolically, because the motifs are not representational and as such are culturally constructed and arbitrary. Moreover, in order for the meaning of this motif to be conveyed to others, language is a prerequisite.

The Blombos engravings are not isolated occurrences, since the presence of such designs occur at more than half a dozen other sites in South Africa, suggesting that this pattern is indeed important in some way, and not the result of idiosyncratic behavior. It is worth noting, however, that for some scholars, the premise that the pattern is symbolic is not so certain. The patterns may indeed have a meaning, but it is how that meaning is associated, either by resemblance (iconic) or correlation (indexical), that is important for our understanding of human cognition.

Fragments of engraved ostrich eggshells from the Howiesons Poort of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa, dated to 60,000 BP. Courtesy of Jean-Pierre Texier, Diepkloof project. © Jean-Pierre Texier

Personal ornamentation and engraved designs are the earliest evidence of art in Africa, and are inextricably tied up with the development of human cognition. For tens of thousands of years, there has been not only a capacity for, but a motivation to adorn and to inscribe, to make visual that which is important. The interesting and pertinent issue in the context of this project is that the rock art we are cataloguing, describing and researching comes from a tradition that goes far back into African prehistory. The techniques and subject matter resonate over the millennia.

Blombos Cave

Discoveries of engraved stones and beads in the Blombos Cave of South Africa has led some archaeologists to believe that early Homo sapiens were capable of abstraction and the production of symbolic art. Made from ochre , the stones are engraved with abstract patterns, while the beads are made from Nassarius shells. While they are simpler than prehistoric cave paintings found in Europe, some scholars believe these engraved stones represent the earliest known artworks, dating from 75,000 years ago.

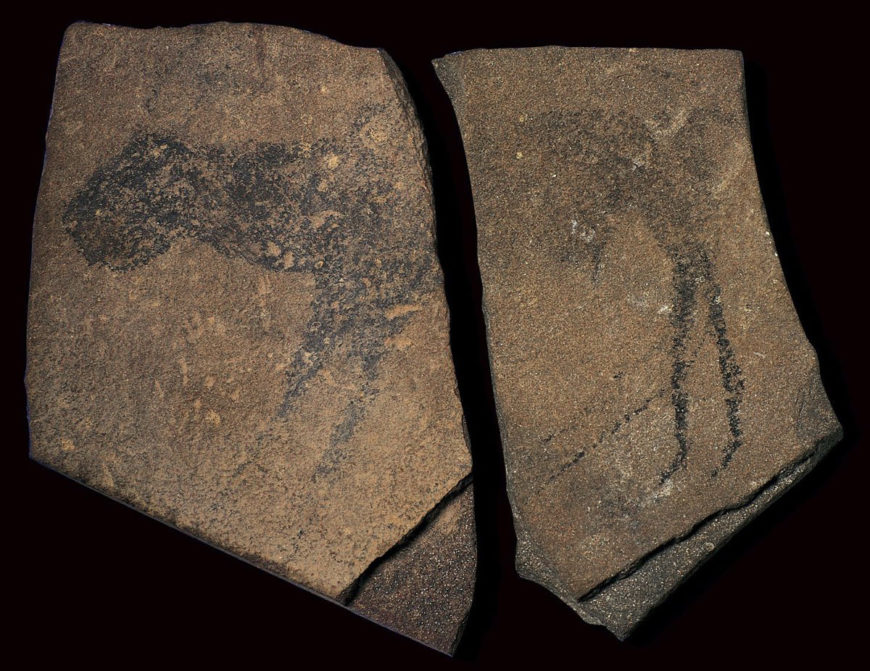

Apollo 11 Cave Stones, Namibia

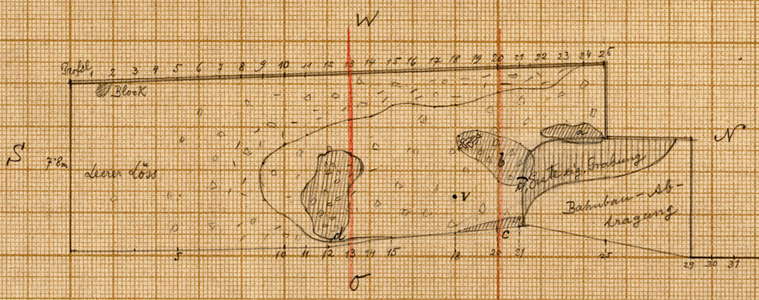

Approximately 25,000 years ago, in a rock shelter in the Huns Mountains of Namibia on the southwest coast of Africa (today part of the Ai-Ais Richtersveld Transfrontier Park), an animal was drawn in charcoal on a hand-sized slab of stone. The stone was left behind, over time becoming buried on the floor of the cave by layers of sediment and debris until 1969 when a team led by German archaeologist W. E. Wendt excavated the rock shelter and found the first fragment. Wendt named the cave “Apollo 11” upon hearing on his shortwave radio of NASA’s successful space mission to the moon. It was more than three years later however, after a subsequent excavation, when Wendt discovered the matching fragment, that archaeologists and art historians began to understand the significance of the find.

The Apollo 11 rock shelter overlooks a dry gorge, sitting twenty meters above what was once a river that ran along the valley floor. The cave entrance is wide, about twenty-eight meters across, and the cave itself is deep: eleven meters from front to back. While today a person can stand upright only in the front section of the cave, during the Middle Stone Age, as well as in the periods before and after, the rock shelter was an active site of ongoing human settlement.

Seven painted stone slabs of brown-grey quartzite, depicting a variety of animals painted in charcoal, ochre and white, were located in a Middle Stone Age deposit (100,000–60,000 years ago). These images are not easily identifiable to species level, but have been interpreted variously as felines and/or bovids; one in particular has been observed to be either a zebra, giraffe or ostrich, demonstrating the ambiguous nature of the depictions.

Apollo 11 Cave Stones, Namibia, quartzite, c. 25,500–25,300 B.C.E. Image courtesy of State Museum of Namibia.

View across Fish River Canyon toward the Huns Mountains, /Ai-/Ais – Richtersveld Transfrontier Park, southern Namibia (photo: Thomas Schoch , CC-BY-SA-3.00

Excavation site of the Apollo 11 stones (photo: Jutta Vogel Stiftung)

Inside the cave, above and below the layer where the Apollo 11 cave stones were found, archaeologists unearthed a sequence of cultural layers representing over 100,000 years of human occupation. In these layers stone artifacts, typical of the Middle Stone Age period—such as blades, pointed flakes, and scraper—were found in raw materials not native to the region, signaling stone tool technology transported over long distances. Among the remnants of hearths, ostrich eggshell fragments bearing traces of red color were also found—either remnants of ornamental painting or evidence that the eggshells were used as containers for pigment.

Recently discovered examples of patterned stone, ochre and ostrich eggshell, as well as evidence of personal ornamentation emerging from Middle Stone Age Africa, have demonstrated that “art” is not only a much older phenomenon than previously thought, but that it has its roots in the African continent. Africa is where we share a common humanity.

The cave stones are what archaeologists term art mobilier —small-scale prehistoric art that is moveable. But mobile art, and rock art generally, is not unique to Africa. Rock art is a global phenomenon that can be found across the World—in Europe, Asia, Australia, and North and South America. While we cannot know for certain what these early humans intended by the things that they made, by focusing on art as the product of humanity’s creativity and imagination we can begin to explore where, and hypothesize why, art began.

Paleolithic art, an introduction

Replica of the painting from the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in southern France (Anthropos museum, Brno)

The oldest art: ornamentation

Humans ( Homo sapiens ) make art. We do this for many reasons and with whatever technologies are available to us. Recent research suggests that Neanderthals also made art.

Extremely old, non-representational ornamentation has been found across Africa. The oldest firmly-dated example is a collection of 82,000 year old Nassarius snail shells found in Morocco that are pierced and covered with red ochre. Wear patterns suggest that they may have been strung beads. Nassarius shell beads found in Israel may be more than 100,000 years old and in the Blombos cave in South Africa, pierced shells and small pieces of ochre (red Hematite) etched with simple geometric patterns have been found in a 75,000-year-old layer of sediment.

The oldest representational art

Some of the oldest known representational imagery comes from the Aurignacian culture of the Upper Paleolithic period (Paleolithic means old stone age). Archaeological discoveries across a broad swath of Europe (especially Southern France, Northern Spain, and Swabia, in Germany) include over two hundred caves with spectacular Aurignacian paintings, drawings, and sculpture that are among the earliest undisputed examples of representational image-making. Among the oldest of these is a 2.4-inch tall female figure carved out of mammoth ivory that was found in six fragments in the Hohle Fels cave near Schelklingen in southern Germany. It dates to 35,000 B.C.E.

Female Figure of Hohlefels, c. 35,000 B.C.E., ivory, found in cave near Schelklinge, southern Germany (photo: Ramessos, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Warty pig (Sus celebensis), c. 43,900 B.C.E., painted with ocher (clay pigment), Maros-Pangkep caves, Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

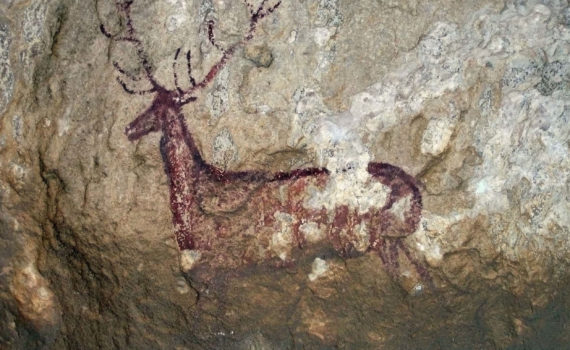

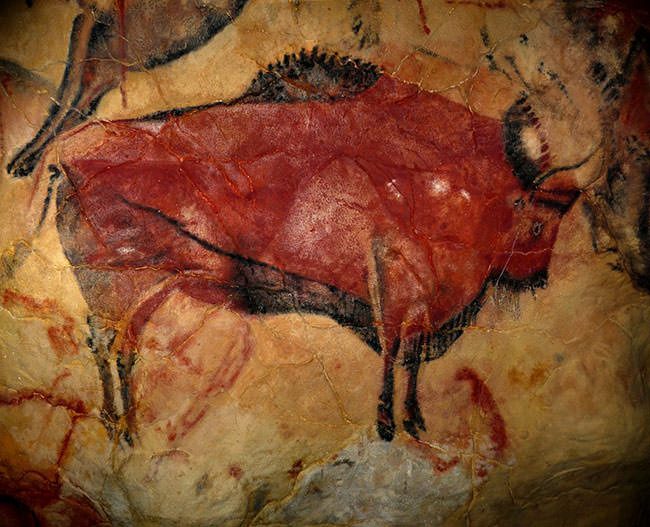

The caves at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc, Lascaux , Pech Merle, and Altamira contain the best known examples of pre-historic painting and drawing. Here are remarkably evocative renderings of animals and some humans that employ a complex mix of naturalism and abstraction. Archaeologists that study Paleolithic era humans, believe that the paintings discovered in 1994, in the cave at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc in the Ardéche valley in France, are more than 30,000 years old. The images found at Lascaux and Altamira are more recent, dating to approximately 15,000 B.C.E. The paintings at Pech Merle date to both 25,000 and 15,000 B.C.E. The world’s oldest known cave painting was found in Sulawesi, Indonesia in 2017 and was made at least 45,500 years ago.

What can we really know about the creators of these paintings and what the images originally meant? These are questions that are difficult enough when we study art made only 500 years ago. It is much more perilous to assert meaning for the art of people who shared our anatomy but had not yet developed the cultures or linguistic structures that shaped who we have become. Do the tools of art history even apply? Here is evidence of a visual language that collapses the more than 1,000 generations that separate us, but we must be cautious. This is especially so if we want to understand the people that made this art as a way to understand ourselves. The desire to speculate based on what we see and the physical evidence of the caves is wildly seductive.

Replica of the painting from the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in southern France

Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc

The cave at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc is over 1,000 feet in length with two large chambers. Carbon samples date the charcoal used to depict the two head-to-head Rhinoceroses (see the image above, bottom right) to between 30,340 and 32,410 years before 1995 when the samples were taken. The cave’s drawings depict other large animals including horses, mammoths, musk ox, ibex, reindeer, aurochs, megaceros deer, panther, and owl (scholars note that these animals were not then a normal part of people’s diet). Photographs show that the drawing at the top of this essay is very carefully rendered but may be misleading. We see a group of horses, rhinos, and bison and we see them as a group, overlapping and skewed in scale. But the photograph distorts the way these animal figures would have been originally seen. The bright electric lights used by the photographer create a broad flat scope of vision; how different to see each animal emerge from the dark under the flickering light cast by a flame.

A word of caution

In a 2009 presentation at University of California San Diego, Dr. Randell White, Professor of Anthropology at New York University, suggested that the overlapping horses pictured above might represent the same horse over time, running, eating, sleeping, etc. Perhaps these are far more sophisticated representations than we have imagined. In addition to the drawings, the cave is littered with the skulls and bones of cave bear and the track of a wolf. There is also a footprint thought to have been made by an eight-year-old boy.

Two main types of Upper Paleolithic art have survived. The first we can classify as permanently located works found on the walls within caves. Mostly unknown prior to the final decades of the nineteenth century, many such sites have now been discovered throughout much of southern Europe and have provided historians and archaeologists new insights into humankind millennia prior to the creation of writing. The subjects of these works vary: we may observe a variety of geometric motifs, many types of flora and fauna, and the occasional human figure. They also fluctuate in size; ranging from several inches to large-scale compositions that span many feet in length.

The second category of Paleolithic art may be called portable since these works are generally of a small-scale—a logical size given the nomadic nature of Paleolithic peoples. Despite their often diminutive size, the creation of these portable objects signifies a remarkable allocation of time and effort.

Paleolithic Sculpture

Sculptural work from the Paleolithic consists mainly of figurines, beads, and some decorative utilitarian objects constructed with stone, bone, ivory, clay, and wood. During prehistoric times, rock shelters were places of dwelling and communal gathering as well as possible spaces for rituals Unsurprisingly, caves were the locations of many archeological discoveries owing to their secluded locations and protection from the elements. Paintings were also found in caves – those that have survived were ritual spaces, there is no evidence that the deep and remote caves were inhabited. All of the surviving sculptures are small and portable – they would easily fit in your pocket. Surviving sculpture are mostly carved from stone or animal ivory and bones. A few ceramic works have been found (the clay figures were air-dried – firing technology is not known to have existed in the Paleolithic). The most common subject is the female form, often with exaggerated secondary sexual characteristics and the facial features are minimal. The best known of these figures is the Woman of Willendorf.

Woman of Willendorf

The name of this prehistoric sculpture refers to a Roman goddess—but what did she originally represent?

Can a 25,000-year-old object be a work of art?

The artifact known as the Venus of Willendorf dates to between 24,000–22,000 B.C.E., making it one of the oldest and most famous surviving works of art. But what does it mean to be a work of art?

The Oxford English Dictionary, perhaps the authority on the English language, defines the word “art” as

the application of skill to the arts of imitation and design, painting, engraving, sculpture, architecture; the cultivation of these in its principles, practice, and results; the skillful production of the beautiful in visible forms.

Some of the words and phrases that stand out within this definition include “application of skill,” “imitation,” and “beautiful.” By this definition, the concept of “art” involves the use of skill to create an object that contains some appreciation of aesthetics. The object is not only made, it is made with an attempt of creating something that contains elements of beauty.

anything made by human art and workmanship; an artificial product. In Archaeol[ogy] applied to the rude products of aboriginal workmanship as distinguished from natural remains.

Again, some keywords and phrases are important: “anything made by human art,” and “rude products.” Clearly, an artifact is any object created by humankind regardless of the “skill” of its creator or the absence of “beauty.”

Click here to go to Sketchfab by the Natural History Museum, Vienna

Artifact, then, is anything created by humankind, and art is a particular kind of artifact, a group of objects under the broad umbrella of artifact, in which beauty has been achieved through the application of skills. Think of the average plastic spoon: a uniform white color, mass produced, and unremarkable in just about every way. While it serves a function—say, for example, to stir your hot chocolate—the person who designed it likely did so without any real dedication or commitment to making this utilitarian object beautiful. You have likely never lovingly gazed at a plastic spoon and remarked, “Wow! Now that’s a beautiful spoon!” This is in contrast to a silver spoon you might purchase at Tiffany & Co. While their spoon could just as well stir cream into your morning coffee, it was skillfully designed by a person who attempted to make it aesthetically pleasing; note the elegant bend of the handle, the gentle luster of the metal, the graceful slope of the bowl.

These terms are important to bear in mind when analyzing prehistoric art. While it is unlikely people from the Upper Paleolithic period cared to conceptualize what it meant to make art or to be an artist, it cannot be denied that the objects they created were made with skill, were often made as a way of imitating the world around them, and were made with a particular care to create something beautiful. They likely represent, for the Paleolithic peoples who created them, objects made with great competence and with a particular interest in aesthetics.

Caves and pockets – permanent and portable

Two main types of Upper Paleolithic art have survived. The first we can classify as permanently located works found on the walls within caves. Mostly unknown prior to the final decades of the nineteenth century, many such sites have now been discovered throughout much of southern Europe and have provided historians and archaeologists new insights into humankind millennia prior to the creation of writing. The subjects of these works vary: we may observe a variety of geometric motifs, many types of flora and fauna, and the occasional human figure. They also fluctuate in size; ranging from several inches to large-scale compositions that span many feet in length.

The second category of Paleolithic art may be called portable since these works are generally of a small-scale—a logical size given the nomadic nature of Paleolithic peoples. Despite their often diminutive size, the creation of these portable objects signifies a remarkable allocation of time and effort. As such, these figurines were significant enough to take along during the nomadic wanderings of their Paleolithic creators.

The Venus of Willendorf is a perfect example of this. Josef Szombathy, an Austro-Hungarian archaeologist, discovered this work in 1908 outside the small Austrian village of Willendorf. Although generally projected in art history classrooms to be several feet tall, this limestone figurine is petite in size. She measures just under 11.1 cm high, and could fit comfortably in the palm of your hand. This small scale allowed whoever carved (or, perhaps owned) this figurine to carry it during their nearly daily nomadic travels in search of food.

Naming and dating

Clearly, the Paleolithic sculptor who made this small figurine would never have named it the Venus of Willendorf . Venus was the name of the Roman goddess of love and ideal beauty. When discovered outside the Austrian village of Willendorf, scholars mistakenly assumed that this figure was likewise a goddess of love and beauty. There is absolutely no evidence though that the Venus of Willendorf shared a function similar to its classically inspired namesake. However incorrect the name may be, it has endured and tells us more about those who found her than those who made her.

Dating too can be a problem, especially since Prehistoric art, by definition, has no written record. In fact, the definition of the word prehistoric is that written language did not yet exist, so the creator of the Venus of Willendorf could not have incised “Bob made this in the year 24,000 B.C.E.” on the back. In addition, stone artifacts present a special problem since we are interested in the date that the stone was carved, not the date of the material itself. Despite these hurdles, art historians and archaeologists attempt to establish dates for prehistoric finds through two processes. The first is called relative dating and the second involves an examination of the stratification of an object’s discovery.

Relative dating is an easily understood process that involves stylistically comparing an object whose date is uncertain to other objects whose dates have been firmly established. By correctly fitting the unknown object into this stylistic chronology, scholars can find a very general chronological date for an object. A simple example can illustrate this method. The first Chevrolet Corvette was sold during the 1953 model year, and this particular car has gone through numerous iterations up to its most recent version. If presented with pictures of the Corvette’s development from every five years to establish the stylistic development from its earliest model to the most recent (for example, images from the 1953, 1958, 1963, and all the way to the current model), you would have a general idea of the changes the car underwent over time. If then given a picture of a Corvette from an unknown year, you could, on the basis of stylistic analysis, generally place it within the visual chronology of this car with some accuracy. The Corvette is a convenient example, but the same exercise could be applied to iPods, Coca-Cola bottles, suits, or any other object that changes over time.

The second way scholars date the Venus of Willendorf is through an analysis of where it was found. Generally, the deeper an object is recovered from the earth, the longer that object has been buried. Imagine a penny jar that has had coins added to it for hundreds of years. It is a good bet that the coins at the bottom of that jar are the oldest whereas those at the top are the newest. The same applies to Paleolithic objects. Because of the depth at which these objects are found, we can infer that they are very old indeed.

What did it mean?

In the absence of writing, art historians rely on the objects themselves to learn about ancient peoples. The form of the Venus of Willendorf —that is, what it looks like—may very well inform what it originally meant. The most conspicuous elements of her anatomy are those that deal with the process of reproduction and child rearing. The artist took particular care to emphasize her breasts, which some scholars suggest indicates that she is able to nurse a child. The artist also brought deliberate attention to her pubic region. Traces of a pigment —red ochre—can still be seen on parts of the figurine.

In contrast, the sculptor placed scant attention on the non-reproductive parts of her body. This is particularly noticeable in the figure’s limbs, where there is little emphasis placed on musculature or anatomical accuracy. We may infer from the small size of her feet that she was not meant to be free standing, and was either meant to be carried or placed lying down. The artist carved the figure’s upper arms along her upper torso, and her lower arms are only barely visible resting upon the top of her breasts. As enigmatic as the lack of attention to her limbs is, the absence of attention to the face is even more striking. No eyes, nose, ears, or mouth remain visible. Instead, our attention is drawn to seven horizontal bands that wrap in concentric circles from the crown of her head. Some scholars have suggested her head is obscured by a knit cap pulled downward, others suggest that these forms may represent braided or beaded hair and that her face, perhaps once painted, is angled downward.

If the face was purposefully obscured, the Paleolithic sculptor may have created, not a portrait of a particular person, but rather a representation of the reproductive and child rearing aspects of a woman. In combination with the emphasis on the breasts and pubic area, it seems likely that the Venus of Willendorf had a function that related to fertility.

Without doubt, we can learn much more from the Venus of Willendorf than its diminutive size might at first suggest. We learn about relative dating and stratification. We learn that these nomadic people living almost 25,000 years ago cared about making objects beautiful. And we can learn that these Paleolithic people had an awareness of the importance of the women.

The Venus of Willendorf is only one example dozens of paleolithic figures we believe may have been associated with fertility. Nevertheless, it retains a place of prominence within the history of human art

The Lion Man

The cave lion was the fiercest animal of the ice age, and this mammoth ivory carving combines human with lion.

URL: https://youtu.be/mJWUPBQpX1c

Cite this page as: The British Museum, “ Lion Man ,” in Smarthistory , March 30, 2018, accessed December 27, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/lion-man-2/ .

Paleolithic Cave Painting

We are as likely to communicate using easily interpretable pictures as we are text. Portable handheld devices enable us to tell others via social media what we are doing and thinking. Approximately 15,000 years ago, we also communicated in pictures—but with no written language.

Lascaux II (replica of the original cave, which is closed to the public), original cave: c. 16,000–14,000 B.C.E., 11 feet 6 inches long (photo: Francesco Bandarin , CC BY-SA 3.0)

The cave of Lascaux, France is one of almost 350 similar sites that are known to exist—most are isolated to a region of southern France and northern Spain . Both Neanderthals (named after the site in which their bones were first discovered—the Neander Valley in Germany) and Modern Humans (early Homo Sapiens Sapiens) coexisted in this region 30,000 years ago. Life was short and very difficult; resources were scarce and the climate was very cold.

Map showing the location of three well-known prehistoric cave painting sites in France and Spain © Google

Location, location, location!

Detail of Hall of Bulls, Lascaux II (replica of the original cave, which is closed to the public), original cave: c. 16,000–14,000 B.C.E.

How did they do it?

The animals are rendered in what has come to be called “ twisted perspective ,” in which their bodies are depicted in profile while we see the horns from a more frontal viewpoint. The images are sometimes entirely linear—line drawn to define the animal’s contour. In many other cases, the animals are described in solid and blended colors blown by mouth onto the wall. In other portions of the Lascaux cave, artists carved lines into the soft calcite surface. Some of these are infilled with color—others are not.

The cave spaces range widely in size and ease of access. The famous Hall of Bulls is large enough to hold some fifty people. Other “rooms” and “halls” are extraordinarily narrow and tall.

Archaeologists have found hundreds of stone tools. They have also identified holes in some walls that may have supported tree-limb scaffolding that would have elevated an artist high enough to reach the upper surfaces. Fossilized pollen has been found; these grains were inadvertently brought into the cave by early visitors and are helping scientists understand the world outside.

Left wall of the Hall of Bulls, Lascaux II (replica of the original cave, which is closed to the public), original cave: c. 16,000–14,000 B.C.E., 11 feet 6 inches long

Hall of Bulls

Why did they do it.

Many scholars have speculated about why prehistoric people painted and engraved the walls at Lascaux and other caves like it. Perhaps the most famous theory was put forth by a priest named Henri Breuil. Breuil spent considerable time in many of the caves, meticulously recording the images in drawings when the paintings were too challenging to photograph. Relying primarily on a field of study known as ethnography , Breuil believed that the images played a role in “hunting magic.” The theory suggests that the prehistoric people who used the cave may have believed that a way to overpower their prey involved creating images of it during rituals designed to ensure a successful hunt. This seems plausible when we remember that survival was entirely dependent on successful foraging and hunting, though it is also important to remember how little we actually know about these people.

Disemboweled bison and bird-headed human figure? Cave at Lascaux, c. 16,000–14,000 B.C.E.

Drawn in strong, black lines, bristles with energy, as the fur on the back of its neck stands up and the head is radically turned to face us. A form drawn under the bison’s abdomen is interpreted as internal organs, spilling out from a wound. A more crudely drawn form positioned below and to the left of the bison may represent a humanoid figure with the head of a bird. Nearby, a thin line is topped with another bird and there is also an arrow with barbs. Further below and to the far left the partial outline of a rhinoceros can be identified.

Interpreters of this image tend to agree that some sort of interaction has taken place among these animals and the bird-headed human figure—in which the bison has sustained injury either from a weapon or from the horn of the rhinoceros. Why the person in the image has the rudimentary head of a bird, and why a bird form sits atop a stick very close to him is a mystery. Some suggest that the person is a shaman —a kind of priest or healer with powers involving the ability to communicate with spirits of other worlds. Regardless, this riveting image appears to depict action and reaction, although many aspects of it are difficult to piece together.

Preservation for future study

The Caves of Lascaux are the most famous of all of the known caves in the region. In fact, their popularity has permanently endangered them. From 1940 to 1963, the numbers of visitors and their impact on the delicately balanced environment of the cave—which supported the preservation of the cave images for so long—necessitated the cave’s closure to the public. A replica called Lascaux II was created about 200 yards away from the site. The original Lascaux cave is now a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. Lascaux will require constant vigilance and upkeep to preserve it for future generations. Many mysteries continue to surround Lascaux, but there is one certainty. The very human need to communicate in the form of pictures—for whatever purpose—has persisted since our earliest beginnings.

Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain (UNESCO/NHK)

URL: https://youtu.be/qyIfPbn0RDs

The Neolithic revolution

Neolithic art and architecture.

by DR. SENTA GERMAN

A settled life