Become a Bestseller

Follow our 5-step publishing path.

Fundamentals of Fiction & Story

Bring your story to life with a proven plan.

Market Your Book

Learn how to sell more copies.

Edit Your Book

Get professional editing support.

Author Advantage Accelerator Nonfiction

Grow your business, authority, and income.

Author Advantage Accelerator Fiction

Become a full-time fiction author.

Author Accelerator Elite

Take the fast-track to publishing success.

Take the Quiz

Let us pair you with the right fit.

Free Copy of Published.

Book title generator, nonfiction outline template, writing software quiz, book royalties calculator.

Learn how to write your book

Learn how to edit your book

Learn how to self-publish your book

Learn how to sell more books

Learn how to grow your business

Learn about self-help books

Learn about nonfiction writing

Learn about fiction writing

How to Get An ISBN Number

A Beginner’s Guide to Self-Publishing

How Much Do Self-Published Authors Make on Amazon?

Book Template: 9 Free Layouts

How to Write a Book in 12 Steps

The 15 Best Book Writing Software Tools

Examples of Creative Nonfiction: What It Is & How to Write It

POSTED ON Jul 21, 2023

Written by P.J McNulty

When most people think of creative writing, they picture fiction books – but there are plenty of examples of creative nonfiction. In fact, creative nonfiction is one of the most interesting genres to read and write. So what is creative nonfiction exactly?

More and more people are discovering the joy of getting immersed in content based on true life that has all the quality and craft of a well-written novel. If you are interested in writing creative nonfiction, it’s important to understand different examples of creative nonfiction as a genre.

If you’ve ever gotten lost in memoirs so descriptive that you felt you’d walked in the shoes of those people, those are perfect examples of creative nonfiction – and you understand exactly why this genre is so popular.

But is creative nonfiction a viable form of writing to pursue? What is creative nonfiction best used to convey? And what are some popular creative nonfiction examples?

Today we will discuss all about this genre, including plenty of examples of creative nonfiction books – so you’ll know exactly how to write it.

This Guide to Creative Nonfiction Covers:

Need A Nonfiction Book Outline?

What is Creative Nonfiction?

Creative nonfiction is defined as true events written about with the techniques and style traditionally found in creative writing . We can understand what creative nonfiction is by contrasting it with plain-old nonfiction.

Think about news or a history textbook, for example. These nonfiction pieces tend to be written in very matter-of-fact, declarative language. While informative, this type of nonfiction often lacks the flair and pleasure that keep people hooked on fictional novels.

Imagine there are two retellings of a true crime story – one in a newspaper and the other in the script for a podcast. Which is more likely to grip you? The dry, factual language, or the evocative, emotionally impactful creative writing?

Podcasts are often great examples of creative nonfiction – but of course, creative nonfiction can be used in books too. In fact, there are many types of creative nonfiction writing. Let's take a look!

Types of creative nonfiction

Creative nonfiction comes in many different forms and flavors. Just as there are myriad types of creative writing, there are almost as many types of creative nonfiction.

Some of the most popular types include:

Literary nonfiction

Literary nonfiction refers to any form of factual writing that employs the literary elements that are more commonly found in fiction. If you’re writing about a true event (but using elements such as metaphor and theme) you might well be writing literary nonfiction.

Writing a life story doesn’t have to be a dry, chronological depiction of your years on Earth. You can use memoirs to creatively tell about events or ongoing themes in your life.

If you’re unsure of what kind of creative nonfiction to write, why not consider a creative memoir? After all, no one else can tell your life story like you.

Nature writing

The beauty of the natural world is an ongoing source of creative inspiration for many people, from photographers to documentary makers. But it’s also a great focus for a creative nonfiction writer. Evoking the majesty and wonder of our environment is an endless source of material for creative nonfiction.

Travel writing

If you’ve ever read a great travel article or book, you’ll almost feel as if you've been on the journey yourself. There’s something special about travel writing that conveys not only the literal journey, but the personal journey that takes place.

Writers with a passion for exploring the world should consider travel writing as their form of creative nonfiction.

For types of writing that leave a lasting impact on the world, look no further than speeches. From a preacher's sermon, to ‘I have a dream’, speeches move hearts and minds like almost nothing else. The difference between an effective speech and one that falls on deaf ears is little more than the creative skill with which it is written.

Biographies

Noteworthy figures from history and contemporary times alike are great sources for creative nonfiction. Think about the difference between reading about someone’s life on Wikipedia and reading about it in a critically-acclaimed biography.

Which is the better way of honoring that person’s legacy and achievements? Which is more fun to read? If there’s someone whose life story is one you’d love to tell, creative nonfiction might be the best way to do it.

So now that you have an idea of what creative nonfiction is, and some different ways you can write it, let's take a look at some popular examples of creative nonfiction books and speeches.

Examples of Creative Nonfiction

Here are our favorite examples of creative nonfiction:

1. In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

No list of examples of creative nonfiction would be complete without In Cold Blood . This landmark work of literary nonfiction by Truman Capote helped to establish the literary nonfiction genre in its modern form, and paved the way for the contemporary true crime boom.

2. A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway's A Moveable Feast is undeniably one of the best creative memoirs ever written. It beautifully reflects on Hemingway’s time in Paris – and whisks you away into the cobblestone streets.

3. World of Wonders by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

If you're looking for examples of creative nonfiction nature writing, no one does it quite like Aimee Nezhukumatathil. World of Wonders is a beautiful series of essays that poetically depicts the varied natural landscapes she enjoyed over the years.

4. A Walk in the Woods by Bill Bryson

Bill Bryson is one of the most beloved travel writers of our time. And A Walk in the Woods is perhaps Bryson in his peak form. This much-loved travel book uses creativity to explore the Appalachian Trail and convey Bryson’s opinions on America in his humorous trademark style.

5. The Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln

While most of our examples of creative nonfiction are books, we would be remiss not to include at least one speech. The Gettysburg Address is one of the most impactful speeches in American history, and an inspiring example for creative nonfiction writers.

6. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

Few have a way with words like Maya Angelou. Her triumphant book, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings , shows the power of literature to transcend one’s circumstances at any time. It is one of the best examples of creative nonfiction that truly sucks you in.

7. Hiroshima by John Hershey

Hiroshima is a powerful retelling of the events during (and following) the infamous atomic bomb. This journalistic masterpiece is told through the memories of survivors – and will stay with you long after you've finished the final page.

8. Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert

If you haven't read the book, you've probably seen the film. Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert is one of the most popular travel memoirs in history. This romp of creative nonfiction teaches us how to truly unmake and rebuild ourselves through the lens of travel.

9. Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

Never has language learning brought tears of laughter like Me Talk Pretty One Day . David Sedaris comically divulges his (often failed) attempts to learn French with a decidedly sadistic teacher, and all the other mishaps he encounters in his fated move from New York to Paris.

10. The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls

Many of us had complicated childhoods, but few of us experienced the hardships of Jeannette Walls. In The Glass Castle , she gives us a transparent look at the betrayals and torments of her youth and how she overcame them with grace – weaving her trauma until it reads like a whimsical fairytale.

Now that you've seen plenty of creative nonfiction examples, it's time to learn how to write your own creative nonfiction masterpiece.

Tips for Writing Creative Nonfiction

Writing creative nonfiction has a lot in common with other types of writing. (You won’t be reinventing the wheel here.) The better you are at writing in general, the easier you’ll find your creative nonfiction project. But there are some nuances to be aware of.

Writing a successful creative nonfiction piece requires you to:

Choose a form

Before you commit to a creative nonfiction project, get clear on exactly what it is you want to write. That way, you can get familiar with the conventions of the style of writing and draw inspiration from some of its classics.

Try and find a balance between a type of creative nonfiction you find personally appealing and one you have the skill set to be effective at.

Gather the facts

Like all forms of nonfiction, your creative project will require a great deal of research and preparation. If you’re writing about an event, try and gather as many sources of information as possible – so you can imbue your writing with a rich level of detail.

If it’s a piece about your life, jot down personal recollections and gather photos from your past.

Plan your writing

Unlike a fictional novel, which tends to follow a fairly well-established structure, works of creative nonfiction have a less clear shape. To avoid the risk of meandering or getting weighed down by less significant sections, structure your project ahead of writing it.

You can either apply the classic fiction structures to a nonfictional event or take inspiration from the pacing of other examples of creative nonfiction you admire.

You may also want to come up with a working title to inspire your writing. Using a free book title generator is a quick and easy way to do this and move on to the actual writing of your book.

Draft in your intended style

Unless you have a track record of writing creative nonfiction, the first time doing so can feel a little uncomfortable. You might second-guess your writing more than you usually would due to the novelty of applying creative techniques to real events. Because of this, it’s essential to get your first draft down as quickly as possible.

Rewrite and refine

After you finish your first draft, only then should you read back through it and critique your work. Perhaps you haven’t used enough source material. Or maybe you’ve overdone a certain creative technique. Whatever you happen to notice, take as long as you need to refine and rework it until your writing feels just right.

Ready to Wow the World With Your Story?

You know have the knowledge and inspiring examples of creative nonfiction you need to write a successful work in this genre. Whether you choose to write a riveting travel book, a tear-jerking memoir, or a biography that makes readers laugh out loud, creative nonfiction will give you the power to convey true events like never before.

Who knows? Maybe your book will be on the next list of top creative nonfiction examples!

Related posts

Business, Writing

You Don’t Need to Hire a Business Book Ghostwriter – Here’s Why

Non-Fiction

This is My Official Plea for a Taylor Swift Book

Need some memorable memoir titles use these tips.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Creative Nonfiction: An Overview

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Creative Nonfiction (CNF) genre can be rather elusive. It is focused on story, meaning it has a narrative plot with an inciting moment, rising action, climax and denoument, just like fiction. However, nonfiction only works if the story is based in truth, an accurate retelling of the author’s life experiences. The pieces can vary greatly in length, just as fiction can; anything from a book-length autobiography to a 500-word food blog post can fall within the genre.

Additionally, the genre borrows some aspects, in terms of voice, from poetry; poets generally look for truth and write about the realities they see. While there are many exceptions to this, such as the persona poem, the nonfiction genre depends on the writer’s ability to render their voice in a realistic fashion, just as poetry so often does. Writer Richard Terrill, in comparing the two forms, writes that the voice in creative nonfiction aims “to engage the empathy” of the reader; that, much like a poet, the writer uses “personal candor” to draw the reader in.

Creative Nonfiction encompasses many different forms of prose. As an emerging form, CNF is closely entwined with fiction. Many fiction writers make the cross-over to nonfiction occasionally, if only to write essays on the craft of fiction. This can be done fairly easily, since the ability to write good prose—beautiful description, realistic characters, musical sentences—is required in both genres.

So what, then, makes the literary nonfiction genre unique?

The first key element of nonfiction—perhaps the most crucial thing— is that the genre relies on the author’s ability to retell events that actually happened. The talented CNF writer will certainly use imagination and craft to relay what has happened and tell a story, but the story must be true. You may have heard the idiom that “truth is stranger than fiction;” this is an essential part of the genre. Events—coincidences, love stories, stories of loss—that may be expected or feel clichéd in fiction can be respected when they occur in real life .

A writer of Creative Nonfiction should always be on the lookout for material that can yield an essay; the world at-large is their subject matter. Additionally, because Creative Nonfiction is focused on reality, it relies on research to render events as accurately as possible. While it’s certainly true that fiction writers also research their subjects (especially in the case of historical fiction), CNF writers must be scrupulous in their attention to detail. Their work is somewhat akin to that of a journalist, and in fact, some journalism can fall under the umbrella of CNF as well. Writer Christopher Cokinos claims, “done correctly, lived well, delivered elegantly, such research uncovers not only facts of the world, but reveals and shapes the world of the writer” (93). In addition to traditional research methods, such as interviewing subjects or conducting database searches, he relays Kate Bernheimer’s claim that “A lifetime of reading is research:” any lived experience, even one that is read, can become material for the writer.

The other key element, the thing present in all successful nonfiction, is reflection. A person could have lived the most interesting life and had experiences completely unique to them, but without context—without reflection on how this life of experiences affected the writer—the reader is left with the feeling that the writer hasn’t learned anything, that the writer hasn’t grown. We need to see how the writer has grown because a large part of nonfiction’s appeal is the lessons it offers us, the models for ways of living: that the writer can survive a difficult or strange experience and learn from it. Sean Ironman writes that while “[r]eflection, or the second ‘I,’ is taught in every nonfiction course” (43), writers often find it incredibly hard to actually include reflection in their work. He expresses his frustration that “Students are stuck on the idea—an idea that’s not entirely wrong—that readers need to think” (43), that reflecting in their work would over-explain the ideas to the reader. Not so. Instead, reflection offers “the crucial scene of the writer writing the memoir” (44), of the present-day writer who is looking back on and retelling the past. In a moment of reflection, the author steps out of the story to show a different kind of scene, in which they are sitting at their computer or with their notebook in some quiet place, looking at where they are now, versus where they were then; thinking critically about what they’ve learned. This should ideally happen in small moments, maybe single sentences, interspersed throughout the piece. Without reflection, you have a collection of scenes open for interpretation—though they might add up to nothing.

- All Online Classes

- 2024 Destination Retreats

- Testimonials

- Create account

- — View All Workshops

- — Fiction Classes

- — Nonfiction Classes

- — Poetry Classes

- — Lit Agent Seminar Series

- — 1-On-1 Mentorships

- — Screenwriting & TV Classes

- — Writing for Children

- — Tuscany September 2024: Apply Now!

- — ----------------

- — Dublin 2025: Join List!

- — Iceland 2025: Join List!

- — Hawaii 2025: Join List!

- — Paris 2025: Join List!

- — Mackinac Island 2025: Join List!

- — Latest Posts

- — Meet the Teaching Artists

- — Student Publication News

- — Our Mission

- — Testimonials

- — FAQ

- — Contact

Shopping Cart

by Writing Workshops Staff

- #Craft of Writing

- #Creative Writing Classes

- #Form a Writing Habit

- #Nonfiction Writing

- #Spiritual Nonfiction

- #Writing Advice

- #Writing Creative Nonfiction

- #Writing Tips

7 Essential Tips on How to Write Creative Nonfiction (A Step-by-Step Guide!)

“The essay becomes an exercise in the meaning and value of watching a writer conquer their own sense of threat to deliver themself of their wisdom.” ― Vivian Gornick, The Situation and the Story: The Art of Personal Narrative

We offer a lot of classes that will help you write Creative Nonfiction . But what makes creative nonfiction different from other types of essays? In creative nonfiction, personal details and anecdotes are used to make the story more relatable and interesting for the reader. Creators often use this style to share their personal thoughts, experiences, or beliefs in a way that can’t be achieved through fiction alone. With a little practice and the right tools, virtually anyone can write creative nonfiction. These tips will help you get started!

Introduction to Creative Nonfiction

Creative nonfiction is a detailed, thoughtful style of writing that allows the author to share their experiences with the reader. It’s similar to a memoir, but it doesn’t have to be a literal account of events. In creative nonfiction, personal details and anecdotes are used to make the story more relatable and interesting for the reader. There are many ways to break down the different types of nonfiction, but broadly speaking, all nonfiction uses the truth, either remembered or researched, to braid together a compelling narrative.

Excellent examples of Creative Nonfiction Include:

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

- The Glass Castle by Jeanette Walls

- Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi

- Committed by Elizabeth Gilbert

- Night Trilogy by Elie Wiesel

- Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- Silent Spring by Rachel Carson

- The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

- Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting by in America by Barbara Ehrenreich

- Dust Tracks on a Road: an autobiography by Nora Zeale Hurston

Select a Topic That You’re Passionate About

Most importantly, choose a topic that you’re passionate about. The topic doesn’t even have to be something that interests you “professionally”—it just has to be something you’re interested in. Begin your research by asking yourself what you’re curious about and what you’ve always wanted to know more about. This can be about yourself, someone else, or the wider world. It could be a current event happening in the world, an everyday activity that many overlook, or a piece of history that has always fascinated you. If you’re struggling to come up with a topic, consider what’s important to you. Your passions, beliefs, and interests can all be great topics to explore in creative nonfiction.

Come Up With Several Ideas for Your Piece

Once you’ve settled on a topic, put together a list of ideas for your creative nonfiction piece. If you’re writing about a current event, you’ll want to make sure that it’s relevant and timely. This way, your readers will be able to connect with your work. You may want to focus on a specific part of the event that interests you. Try to come at your topic from a different angle, or with a new perspective.

Research Your Subject Thoroughly

Once you’ve decided on your topic and idea, it’s time to start researching. In addition to personal experience and anecdote, researching is one of the fundamental parts of writing nonfiction, even if you're writing creatively. If you want to make your research more interesting and engaging for the reader, include anecdotes and personal details.

Now that you’ve put together an outline and researched your topic, it’s time to start writing! It might seem simple, but the hardest part of writing is just getting started. Once you’ve got your thoughts down on paper, the rest is smooth sailing.

Try writing a messy first draft in first person as if you’re speaking directly to your reader. To tap into your voice, don't shy away from using slang, jargon, or other kinds of expression that might be only be understood by a niche audience; you can always layer in more context in a subsequent draft. But whatever you do, don't edit out your style from the beginning. Be you on the page first and polish later.

It is okay to be messy in this draft. Write as naturally as possible so that you aren't sanding away the kind of observations and perspective that amplify your voice and lived experience.

Tips to Help You Write Creatively

Here are a few tips that can help you write creatively:

Read. This may seem obvious, but when you read, you're exposed to a wide range of styles and techniques that can help you understand and use different writing styles. If you're not reading, you're missing out on opportunities to learn from people who've done what you want to do, and that can be invaluable.

Experiment. Experimenting with different writing styles, topics, and approaches will help you to find your voice and discover the types of creative nonfiction that come most naturally to you.

Learn from your peers. Look to your peers and colleagues to learn from them—both their successes and their mistakes.

Find inspiration. Inspiration can come from anywhere, so make sure that you're open to observing new experiences, even in mundane day-to-day activities. Inspiration is everywhere if you're looking for it.

Don't be afraid to fail. This is most import! We learn from our mistakes and experiences, and that's true of writing, too.

Be yourself. The most authentic and interesting writing comes from the heart.

Have fun! Writing should be enjoyable, and trying to write creatively while feeling pressured and stressed out will only make it more difficult.

Discover a Creative Nonfiction Class that is just right for you!

Related Blog Posts

Meet the Teaching Artist: Book Proposal 101 with Tawny Lara

Meet the Teaching Artist: Leveraging Concision in Fiction Writing with Jon Roemer

On Writing Through Parenthood: an Interview with Katie Reilly

How to Conceive & Structure Personal Essays: an Interview with Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

How to get published.

A Guide to Writing Creative Nonfiction

by Melissa Donovan | Mar 4, 2021 | Creative Writing | 12 comments

Try your hand at writing creative nonfiction.

Here at Writing Forward, we’re primarily interested in three types of creative writing: poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction.

With poetry and fiction, there are techniques and best practices that we can use to inform and shape our writing, but there aren’t many rules beyond the standards of style, grammar, and good writing . We can let our imaginations run wild; everything from nonsense to outrageous fantasy is fair game for bringing our ideas to life when we’re writing fiction and poetry.

However, when writing creative nonfiction, there are some guidelines that we need to follow. These guidelines aren’t set in stone; however, if you violate them, you might find yourself in trouble with your readers as well as the critics.

What is Creative Nonfiction?

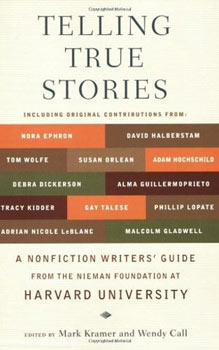

Telling True Stories (aff link).

What sets creative nonfiction apart from fiction or poetry?

For starters, creative nonfiction is factual. A memoir is not just any story; it’s a true story. A biography is the real account of someone’s life. There is no room in creative nonfiction for fabrication or manipulation of the facts.

So what makes creative nonfiction writing different from something like textbook writing or technical writing? What makes it creative?

Nonfiction writing that isn’t considered creative usually has business or academic applications. Such writing isn’t designed for entertainment or enjoyment. Its sole purpose is to convey information, usually in a dry, straightforward manner.

Creative nonfiction, on the other hand, pays credence to the craft of writing, often through literary devices and storytelling techniques, which make the prose aesthetically pleasing and bring layers of meaning to the context. It’s pleasurable to read.

According to Wikipedia:

Creative nonfiction (also known as literary or narrative nonfiction) is a genre of writing truth which uses literary styles and techniques to create factually accurate narratives. Creative nonfiction contrasts with other nonfiction, such as technical writing or journalism, which is also rooted in accurate fact, but is not primarily written in service to its craft.

Like other forms of nonfiction, creative nonfiction relies on research, facts, and credibility. While opinions may be interjected, and often the work depends on the author’s own memories (as is the case with memoirs and autobiographies), the material must be verifiable and accurately reported.

Creative Nonfiction Genres and Forms

There are many forms and genres within creative nonfiction:

- Autobiography and biography

- Personal essays

- Literary journalism

- Any topical material, such as food or travel writing, self-development, art, or history, can be creatively written with a literary angle

Let’s look more closely at a few of these nonfiction forms and genres:

Memoirs: A memoir is a long-form (book-length) written work. It is a firsthand, personal account that focuses on a specific experience or situation. One might write a memoir about serving in the military or struggling with loss. Memoirs are not life stories, but they do examine life through a particular lens. For example, a memoir about being a writer might begin in childhood, when the author first learned to write. However, the focus of the book would be on writing, so other aspects of the author’s life would be left out, for the most part.

Biographies and autobiographies: A biography is the true story of someone’s life. If an author composes their own biography, then it’s called an autobiography. These works tend to cover the entirety of a person’s life, albeit selectively.

Literary journalism: Journalism sticks with the facts while exploring the who, what, where, when, why, and how of a particular person, topic, or event. Biographies, for example, are a genre of literary journalism, which is a form of nonfiction writing. Traditional journalism is a method of information collection and organization. Literary journalism also conveys facts and information, but it honors the craft of writing by incorporating storytelling techniques and literary devices. Opinions are supposed to be absent in traditional journalism, but they are often found in literary journalism, which can be written in long or short formats.

Personal essays are a short form of creative nonfiction that can cover a wide range of styles, from writing about one’s experiences to expressing one’s personal opinions. They can address any topic imaginable. Personal essays can be found in many places, from magazines and literary journals to blogs and newspapers. They are often a short form of memoir writing.

Speeches can cover a range of genres, from political to motivational to educational. A tributary speech honors someone whereas a roast ridicules them (in good humor). Unlike most other forms of writing, speeches are written to be performed rather than read.

Journaling: A common, accessible, and often personal form of creative nonfiction writing is journaling. A journal can also contain fiction and poetry, but most journals would be considered nonfiction. Some common types of written journals are diaries, gratitude journals, and career journals (or logs), but this is just a small sampling of journaling options.

Writing Creative Nonfiction (aff link).

Any topic or subject matter is fair game in the realm of creative nonfiction. Some nonfiction genres and topics that offer opportunities for creative nonfiction writing include food and travel writing, self-development, art and history, and health and fitness. It’s not so much the topic or subject matter that renders a written work as creative; it’s how it’s written — with due diligence to the craft of writing through application of language and literary devices.

Guidelines for Writing Creative Nonfiction

Here are six simple guidelines to follow when writing creative nonfiction:

- Get your facts straight. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing your own story or someone else’s. If readers, publishers, and the media find out you’ve taken liberties with the truth of what happened, you and your work will be scrutinized. Negative publicity might boost sales, but it will tarnish your reputation; you’ll lose credibility. If you can’t refrain from fabrication, then think about writing fiction instead of creative nonfiction.

- Issue a disclaimer. A lot of nonfiction is written from memory, and we all know that human memory is deeply flawed. It’s almost impossible to recall a conversation word for word. You might forget minor details, like the color of a dress or the make and model of a car. If you aren’t sure about the details but are determined to include them, be upfront and include a disclaimer that clarifies the creative liberties you’ve taken.

- Consider the repercussions. If you’re writing about other people (even if they are secondary figures), you might want to check with them before you publish your nonfiction. Some people are extremely private and don’t want any details of their lives published. Others might request that you leave certain things out, which they want to keep private. Otherwise, make sure you’ve weighed the repercussions of revealing other people’s lives to the world. Relationships have been both strengthened and destroyed as a result of authors publishing the details of other people’s lives.

- Be objective. You don’t need to be overly objective if you’re telling your own, personal story. However, nobody wants to read a highly biased biography. Book reviews for biographies are packed with harsh criticism for authors who didn’t fact-check or provide references and for those who leave out important information or pick and choose which details to include to make the subject look good or bad.

- Pay attention to language. You’re not writing a textbook, so make full use of language, literary devices, and storytelling techniques.

- Know your audience. Creative nonfiction sells, but you must have an interested audience. A memoir about an ordinary person’s first year of college isn’t especially interesting. Who’s going to read it? However, a memoir about someone with a learning disability navigating the first year of college is quite compelling, and there’s an identifiable audience for it. When writing creative nonfiction, a clearly defined audience is essential.

Are you looking for inspiration? Check out these creative nonfiction writing ideas.

Ten creative nonfiction writing prompts and projects.

The prompts below are excerpted from my book, 1200 Creative Writing Prompts , which contains fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction writing prompts. Use these prompts to spark a creative nonfiction writing session.

1200 Creative Writing Prompts (aff link).

- What is your favorite season? What do you like about it? Write a descriptive essay about it.

- What do you think the world of technology will look like in ten years? Twenty? What kind of computers, phones, and other devices will we use? Will technology improve travel? Health care? What do you expect will happen and what would you like to happen?

- Have you ever fixed something that was broken? Ever solved a computer problem on your own? Write an article about how to fix something or solve some problem.

- Have you ever had a run-in with the police? What happened?

- Have you ever traveled alone? Tell your story. Where did you go? Why? What happened?

- Let’s say you write a weekly advice column. Choose the topic you’d offer advice on, and then write one week’s column.

- Think of a major worldwide problem: for example, hunger, climate change, or political corruption. Write an article outlining a solution (or steps toward a solution).

- Choose a cause that you feel is worthy and write an article persuading others to join that cause.

- Someone you barely know asks you to recommend a book. What do you recommend and why?

- Hard skills are abilities you have acquired, such as using software, analyzing numbers, and cooking. Choose a hard skill you’ve mastered and write an article about how this skill is beneficial using your own life experiences as examples.

Do You Write Creative Nonfiction?

Have you ever written creative nonfiction? How often do you read it? Can you think of any nonfiction forms and genres that aren’t included here? Do you have any guidelines to add to this list? Are there any situations in which it would be acceptable to ignore these guidelines? Got any tips to add? Do you feel that nonfiction should focus on content and not on craft? Leave a comment to share your thoughts, and keep writing.

12 Comments

Shouldn’t ALL non-fiction be creative to some extent? I am a former business journalist, and won awards for the imaginative approach I took to writing about even the driest of business topics: pensions, venture capital, tax, employment law and other potentially dusty subjects. The drier and more complicated the topic, the more creative the approach must be, otherwise no-one with anything else to do will bother to wade through it. [to be honest, taking the fictional approach to these ghastly tortuous topics was the only way I could face writing about them.] I used all the techniques that fiction writers have to play with, and used some poetic techniques, too, to make the prose more readable. What won the first award was a little serial about two businesses run and owned by a large family at war with itself. Every episode centred on one or two common and crucial business issues, wrapped up in a comedy-drama, and it won a lot of fans (happily for me) because it was so much easier to read and understand than the dry technical writing they were used to. Life’s too short for dusty writing!

I believe most journalism is creative and would therefore fall under creative nonfiction. However, there is a lot of legal, technical, medical, science, and textbook writing in which there is no room for creativity (or creativity has not made its way into these genres yet). With some forms, it makes sense. I don’t think it would be appropriate for legal briefings to use story or literary devices just to add a little flair. On the other hand, it would be a good thing if textbooks were a little more readable.

I think Abbs is right – even in academic papers, an example or story helps the reader visualize the problem or explanation more easily. I scan business books to see if there are stories or examples, if not, then I don’t pick up the book. That’s where the creativity comes in – how to create examples, what to conflate, what to emphasis as we create our fictional people to illustrate important, real points.

Thanks for the post. Very helpful. I’d never thought about writing creative nonfiction before.

You’re welcome 🙂

Hi Melissa!

Love your website. You always give a fun and frank assessment of all things pertaining to writing. It is a pleasure to read. I have even bought several of the reference and writing books you recommended. Keep up the great work.

Top 10 Reasons Why Creative Nonfiction Is A Questionable Category

10. When you look up “Creative Nonfiction” in the dictionary it reads: See Fiction

9. The first creative nonfiction example was a Schwinn Bicycle Assembly Guide that had printed in its instructions: Can easily be assembled by one person with a Phillips head screw driver, Allen keys, adjustable wrench and cable cutters in less than an hour.

8. Creative Nonfiction; Based on actual events; Suggested by a true event; Based on a true story. It’s a slippery slope.

7. The Creative Nonfiction Quarterly is only read by eleven people. Five have the same last name.

6. Creative Nonfiction settings may only include: hospitals, concentration camps, prisons and cemeteries. Exceptions may be made for asylums, rehab centers and Capitol Hill.

5. The writers who create Sterile Nonfiction or Unimaginative Nonfiction now want their category recognized.

4. Creative; Poetic License; Embellishment; Puffery. See where this is leading?

3. Creative Nonfiction is to Nonfiction as Reality TV is to Documentaries.

2. My attorney has advised that I exercise my 5th Amendment Rights or that I be allowed to give written testimony in a creative nonfiction way.

1. People believe it is a film with Will Ferrell, Emma Thompson and Queen Latifa.

Hi Steve. I’m not sure if your comment is meant to be taken tongue-in-cheek, but I found it humorous.

My publisher is releasing my Creative Nonfiction book based on my grandmother’s life this May 2019 in Waikiki. I’ll give you an update soon about sales. I was fortunate enough to get some of the original and current Hawaii 5-0 members to show up for the book signing.

Hi, when writing creative nonfiction- is it appropriate to write from someone else’s point of view when you don’t know them? I was thinking of writing about Greta Thungbrurg for creative nonfiction competition – but I can directly ask her questions so I’m unsure as to whether it’s accurate enough to be classified as creative non-fiction. Thank you!

Hi Madeleine. I’m not aware of creative nonfiction being written in first person from someone else’s point of view. The fact of the matter is that it wouldn’t be creative nonfiction because a person cannot truly show events from another person’s perspective. So I wouldn’t consider something like that nonfiction. It would usually be a biography written in third person, and that is common. You can certainly use quotes and other indicators to represent someone else’s views and experiences. I could probably be more specific if I knew what kind of work it is (memoir, biography, self-development, etc.).

Dear Melissa: I am trying to market a book in the metaphysical genre about an experience I had, receiving the voice of a Civil War spirit who tells his story (not channeling). Part is my reaction and discussion with a close friend so it is not just memoir. I referred to it as ‘literary non-fiction’ but an agent put this down by saying it is NOT literary non-fiction. Looking at your post, could I say that my book is ‘creative non-fiction’? (agents can sometimes be so nit-picky)

Hi Liz. You opened your comment by classifying the book as metaphysical but later referred to it as literary nonfiction. The premise definitely sounds like a better fit in the metaphysical category. Creative nonfiction is not a genre; it’s a broader category or description. Basically, all literature is either fiction or nonfiction (poetry would be separate from these). Describing nonfiction as creative only indicates that it’s not something like a user guide. I think you were heading in the right direction with the metaphysical classification.

The goal of marketing and labeling books with genres is to find a readership that will be interested in the work. This is an agent’s area of expertise, so assuming you’re speaking with a competent agent, I’d suggest taking their advice in this matter. It indicates that the audience perusing the literary nonfiction aisles is simply not a match for this book.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Top Picks Thursday! For Writers & Readers 03-11-2021 | The Author Chronicles - […] If your interests leans toward nonfiction, Melissa Donovan presents a guide to writing creative nonfiction. […]

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Subscribe and get The Writer’s Creed graphic e-booklet, plus a weekly digest with the latest articles on writing, as well as special offers and exclusive content.

Recent Posts

- Writing Resources: No Plot? No Problem!

- Character-Driven Fiction Writing Prompts

- From 101 Creative Writing Exercises: Invention of Form

- How to Write Better Stories

- How to Start Writing Poetry

Write on, shine on!

Pin It on Pinterest

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

A Guide to Writing Creative Nonfiction

4-minute read

- 21st August 2022

Creative nonfiction is a genre that uses literary elements usually associated with fiction writing (e.g., narrative arc, character development) to tell true stories. Sometimes referred to as narrative nonfiction, creative nonfiction can range from tweet-sized stories to book-length memoirs.

Creative Nonfiction , a magazine dedicated to the genre, defines it succinctly as “true stories, well told.” In today’s post, we offer our advice to anyone setting out to write a piece of creative nonfiction:

- Tell the truth.

- Use literary devices.

- Record your sources.

- Include your own thoughts and opinions.

- Check your work for errors.

If you’re inspired to write a literary journalistic article , personal essay, biography , or any other piece of creative nonfiction, read on to learn more about these points:

1. Don’t Make Anything Up

Everything you say in creative nonfiction must be true (the clue’s in the name). You must, therefore, be diligent in recording only verifiable events that you have thoroughly researched or that you personally remember.

It can be especially hard to do this if you’re writing your own story. It’s tempting to leave out or alter details that cast you in a bad light. However, the creative nonfiction genre demands honesty and accuracy.

Sometimes, of course, information will be unavailable, or you’ll have conflicting accounts of an event or conversation. The golden rule is to never contradict what you know to be true. If there are different versions of an incident, present both (or all) of them and let the reader decide which is the most convincing.

2. Use the Tools of a Fiction Writer

Creative nonfiction is different than a textbook or news article. Rather than simply reporting a series of facts, writers of creative nonfiction present those facts in narrative form. To do this, you have all the tools of fiction writing at your disposal.

Rather than telling your story chronologically, you could employ in medias res . In other words, start things off by plunging the reader straight into the action. You can reveal the events that led up to this dramatic moment by jumping back to an earlier time, or referring to it in flashbacks and conversations.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Draw readers into your story by using vibrant, descriptive language that brings to life the setting and characters. You can also enrich your writing by using foreshadowing, metaphors, symbolism, dramatic irony, and all manner of other literary devices.

3. Keep Track of Your Information Sources

To tell your story accurately, you’ll have to do a lot of research. Even if you’re writing about your own experience, you’ll want to draw on other people’s memories of events rather than simply rely on your own.

Additionally, you could gain relevant information from books, old newspapers, and the internet, or by visiting places that are significant to your story.

It’s vital to keep a record of where all your information comes from. Even if you don’t refer to your sources in your book or article, you might be called on to verify something you’ve written. Moreover, if you want to go back over something to check the finer details, it can be hard to remember where to look if you haven’t written it down.

4. Let Your Own Voice Be Heard

One of the things that sets creative nonfiction apart from traditional journalism is that the writer’s voice is a key element of creative nonfiction. While you must relate events truthfully, you are free to share your own opinions and feelings and allow them to influence the way you write.

5. Remember to Proofread

While it’s up to you to faithfully depict the events, characters, and setting of your creative nonfiction piece, we can help you eliminate writing errors like typos and grammatical mistakes.

Our proofreading service includes tweaking sentences that don’t flow smoothly and suggesting corrections for anything unclear. Our team is available around the clock and will return your document error-free within 24 hours. Find out more today with a free trial .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Related Topics

- How to Write a Book

- Writing a Book for the First Time

- How to Write an Autobiography

- How Long Does it Take to Write a Book?

- Do You Underline Book Titles?

- Snowflake Method

- Book Title Generator

- How to Write Nonfiction Book

- How to Write a Children's Book

- How to Write a Memoir

- Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Book

- How to Write a Book Title

- How to Write a Book Introduction

- How to Write a Dedication in a Book

- How to Write a Book Synopsis

- Types of Writers

- How to Become a Writer

- Author Overview

- Document Manager Overview

- Screenplay Writer Overview

- Technical Writer Career Path

- Technical Writer Interview Questions

- Technical Writer Salary

- Google Technical Writer Interview Questions

- How to Become a Technical Writer

- UX Writer Career Path

- Google UX Writer

- UX Writer vs Copywriter

- UX Writer Resume Examples

- UX Writer Interview Questions

- UX Writer Skills

- How to Become a UX Writer

- UX Writer Salary

- Google UX Writer Overview

- Google UX Writer Interview Questions

- Technical Writing Certifications

- Grant Writing Certifications

- UX Writing Certifications

- Proposal Writing Certifications

- Content Design Certifications

- Knowledge Management Certifications

- Medical Writing Certifications

- Grant Writing Classes

- Business Writing Courses

- Technical Writing Courses

- Content Design Overview

- Documentation Overview

- User Documentation

- Process Documentation

- Technical Documentation

- Software Documentation

- Knowledge Base Documentation

- Product Documentation

- Process Documentation Overview

- Process Documentation Templates

- Product Documentation Overview

- Software Documentation Overview

- Technical Documentation Overview

- User Documentation Overview

- Knowledge Management Overview

- Knowledge Base Overview

- Publishing on Amazon

- Amazon Authoring Page

- Self-Publishing on Amazon

- How to Publish

- How to Publish Your Own Book

- Document Management Software Overview

- Engineering Document Management Software

- Healthcare Document Management Software

- Financial Services Document Management Software

- Technical Documentation Software

- Knowledge Management Tools

- Knowledge Management Software

- HR Document Management Software

- Enterprise Document Management Software

- Knowledge Base Software

- Process Documentation Software

- Documentation Software

- Internal Knowledge Base Software

- Grammarly Premium Free Trial

- Grammarly for Word

- Scrivener Templates

- Scrivener Review

- How to Use Scrivener

- Ulysses vs Scrivener

- Character Development Templates

- Screenplay Format Templates

- Book Writing Templates

- API Writing Overview

- Business Writing Examples

- Business Writing Skills

- Types of Business Writing

- Dialogue Writing Overview

- Grant Writing Overview

- Medical Writing Overview

- How to Write a Novel

- How to Write a Thriller Novel

- How to Write a Fantasy Novel

- How to Start a Novel

- How Many Chapters in a Novel?

- Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Novel

- Novel Ideas

- How to Plan a Novel

- How to Outline a Novel

- How to Write a Romance Novel

- Novel Structure

- How to Write a Mystery Novel

- Novel vs Book

- Round Character

- Flat Character

- How to Create a Character Profile

- Nanowrimo Overview

- How to Write 50,000 Words for Nanowrimo

- Camp Nanowrimo

- Nanowrimo YWP

- Nanowrimo Mistakes to Avoid

- Proposal Writing Overview

- Screenplay Overview

- How to Write a Screenplay

- Screenplay vs Script

- How to Structure a Screenplay

- How to Write a Screenplay Outline

- How to Format a Screenplay

- How to Write a Fight Scene

- How to Write Action Scenes

- How to Write a Monologue

- Short Story Writing Overview

- Technical Writing Overview

- UX Writing Overview

- Reddit Writing Prompts

- Romance Writing Prompts

- Flash Fiction Story Prompts

- Dialogue and Screenplay Writing Prompts

- Poetry Writing Prompts

- Tumblr Writing Prompts

- Creative Writing Prompts for Kids

- Creative Writing Prompts for Adults

- Fantasy Writing Prompts

- Horror Writing Prompts

- Book Writing Software

- Novel Writing Software

- Screenwriting Software

- ProWriting Aid

- Writing Tools

- Literature and Latte

- Hemingway App

- Final Draft

- Writing Apps

- Grammarly Premium

- Wattpad Inbox

- Microsoft OneNote

- Google Keep App

- Technical Writing Services

- Business Writing Services

- Content Writing Services

- Grant Writing Services

- SOP Writing Services

- Script Writing Services

- Proposal Writing Services

- Hire a Blog Writer

- Hire a Freelance Writer

- Hire a Proposal Writer

- Hire a Memoir Writer

- Hire a Speech Writer

- Hire a Business Plan Writer

- Hire a Script Writer

- Hire a Legal Writer

- Hire a Grant Writer

- Hire a Technical Writer

- Hire a Book Writer

- Hire a Ghost Writer

Home » Blog » How to Write a Nonfiction Book (8 Key Stages)

How to Write a Nonfiction Book (8 Key Stages)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

This article explores how to write a nonfiction book, a genre encompassing various subjects from history and biography to self-help and science.

Nonfiction writing, distinct from its fictional counterpart, demands a rigorous approach to factual accuracy, comprehensive research, and clarity in presentation. We aim to provide a pragmatic guide for aspiring authors, delineating the steps involved in a nonfiction work’s conceptualization, research, writing, editing, and publishing.

This guide serves both novice and experienced writers, offering insights into each phase of the book-writing process. By adhering to a methodical approach, writers can transform their knowledge and ideas into compelling, well-structured nonfiction books.

How to Write a Nonfiction Book

Here are the main 8 stages of writing a nonfiction book. Let’s start.

Choosing a Topic

Selecting the right topic is the cornerstone of writing a successful nonfiction book. This step is crucial because it influences your writing journey and impacts the appeal to your target audience.

Whether you are writing a nonfiction book for the first time or the tenth time, it never hurts to use a good template. Squibler provides writing-ready templates, including for nonfiction topics.

Identifying Your Passion

Begin by introspecting about subjects you are interested in or even a personal story that you have. The ideal topic should intrigue you and sustain your interest over the long process of writing a book. It could be a field you have expertise in, a hobby you are passionate about, or a subject you have always wanted to explore in depth.

Use Portent’s Content Idea Generator to generate ideas based on any subject you have in mind.

Assessing Market Demand

Once you have a list of potential topics, the next step is to analyze the market demand. This involves researching current trends, finding a popular nonfiction book title in your chosen genre, and identifying gaps in the available literature. Tools like Google Trends and Amazon’s Best Sellers lists can provide insights into what readers are currently interested in.

Conducting Initial Research

Before finalizing your topic, conduct preliminary research to ensure there’s enough information available to cover your subject comprehensively. This research will also help you understand the different perspectives and debates surrounding your topic. It’s important to ensure that the topic is not too broad, making it difficult to cover thoroughly or too narrow, limiting the book’s appeal to a wider audience.

Finalizing Your Topic

After considering your passion, market demand, and the availability of research material, narrow down your choices to one topic. This topic should be interesting and marketable and offer a unique angle or perspective that distinguishes your book from existing works in the field.

Use the Hedgehog Concept to find a great topic for your nonfiction book. Read all about this concept here .

In summary, choosing a topic for your nonfiction book requires balancing personal interest, market viability, and availability of sufficient content. This careful consideration will set the foundation for a compelling and successful nonfiction book.

Research and Gathering Information

Conducting research is a fundamental aspect of writing nonfiction. It involves gathering, organizing, and verifying information to ensure reliability.

Detailed Methods for Conducting Effective Research

Here are helpful methods for conducting research:

- Identify Reliable Sources: Identify authoritative sources such as academic journals, books by respected authors, government publications, and reputable news organizations. Online databases and libraries can be invaluable for this.

- Diverse Research Techniques: Use primary sources (like interviews, surveys, and firsthand observations) and secondary sources (such as books, articles, and documentaries). This mix provides depth and perspective to your research.

- Note-Taking and Documentation: As you gather information, take detailed notes. Record bibliographic information (author, title, publication date, etc.) for each source to make referencing easier later. Tools like Zotero or EndNote can help manage citations.

Tips for Organizing and Compiling Research Materials

Here are some further tips for organizing your nonfiction book writing process.

- Categorize Information: Organize your research into categories related to different aspects of your topic. This will make it easier to find information when you start writing.

- Use Digital Tools: Utilize digital tools such as spreadsheets, document folders, or specialized research software to keep your information organized.

- Maintain a Research Log: Keep a log of your research activities, including where you found information and keywords or topics searched. This log will be invaluable if you need to revisit a source.

By using Squibler for your writing, you can use many tools to organize your writing to stick to a steady schedule.

Ethical Considerations and Fact-Checking in Nonfiction Writing

Here are ethical considerations to be aware of when learning how to write a nonfiction book:

- Fact-Checking: Rigorously check the facts you plan to include in your book. Verify dates, names, quotes, and statistics from multiple sources.

- Avoid Plagiarism: Always give proper credit to the sources of your information. Paraphrase where necessary and use quotations for direct citations.

- Ethical Reporting: Be aware of the ethical implications of your writing, especially when dealing with sensitive topics. Strive for fairness and accuracy in your representation of different viewpoints.

Effective research for a nonfiction book requires a systematic and ethical approach to gathering, organizing, and verifying information. You can ensure that your nonfiction work is credible and compelling by using various research methods, maintaining organized notes, and adhering to ethical standards.

Planning and Outlining the Book

Planning and outlining are critical steps in writing a nonfiction book. This phase involves structuring your ideas and research findings into a coherent and logical framework to guide your writing process.

Importance of Creating a Detailed Outline

Read about the importance of having a detailed outline.

- Blueprint for Your Book: An outline serves as a roadmap for your book, helping you organize your thoughts and research systematically. It ensures that your narrative flows and that you cover all key points.

- Efficiency and Focus: A well-structured outline helps you write. It keeps you focused on your main points and prevents you from veering off-topic.

- Identifying Gaps: During the outlining process, you may identify areas where further research or elaboration is needed, allowing you to address these gaps before you begin writing.

Here is an example of how to outline your book based on the structure:

Methods for Outlining Nonfiction Books

Here, you’ll learn about key methods for creating an outline:

- Chronological Structure: A chronological approach might be most effective for topics that unfold over time, such as historical events or biographies.

- Thematic Structure: If your book covers different aspects of a topic, organizing your outline by themes or subjects can help present information in a more integrated way.

- Problem-Solution Framework: For topics like business or self-help, structuring your outline to present problems and their solutions can engage readers.

Tips for Structuring Your Book

Read some further tips for creating a book structure:

- Start with a Broad Overview: Begin your outline with a broad overview of your topic, then break it into more specific chapters or sections.

- Balance Your Chapters: Try to balance the length and depth of each chapter to keep readers engaged and ensure a smooth flow.

- Include Introduction and Conclusion: Plan for an introductory section to set the context of your book and a conclusion to wrap up and reinforce your key messages.

- Consider Readers’ Needs: Keep your intended audience in mind while outlining. Structure your content to address the readers’ interests, background knowledge, and expectations.

Writing the First Draft

Writing the first draft of a nonfiction book is where you transform your research and outline into a manuscript. This stage is about getting your ideas down on paper and shaping the raw material of your research into a readable and engaging narrative.

Starting the Writing Process

Here, you will read the main steps in writing nonfiction and healthy writing habits for creative nonfiction.

- Overcoming the Blank Page: The first step is to overcome the intimidation of the blank page. Begin by writing about the parts you are most comfortable with or most excited about. This builds momentum.

- Refer to Your Outline: Consult your outline to stay on track. However, be flexible enough to deviate if a section needs more elaboration or a different direction.

- Set Realistic Goals: Establish daily or weekly word count goals. Consistency is key to making steady progress.

- Write Consistent Conversations: A nonfiction writer creates a conversation with their readers. Create a consistent information flow by using one of the four types.

Here are four types of conversations that will give you an idea of what will work best for your audience.

Maintaining a Consistent Writing Routine

Learn how to maintain a writing routine in each writing phase:

- Create a Writing Schedule: Set aside dedicated time for writing each day or week. Consistency is crucial, whether an hour every morning or a full day over the weekend.

- Create a Writing Environment: Find or create a space where you can write without distractions. The right environment can significantly boost your productivity and focus.

Dealing with Writer’s Block

Read about the basics of overcoming writer’s block.

- Take Breaks: Step away from your work if you hit a block. Sometimes, taking a short walk or engaging in a different activity can refresh your mind.

- Write Freely: Don’t be too concerned with perfection in the first draft. Allow yourself to write freely without worrying too much about grammar or style at this stage.

- Talk It Out: Discussing your ideas with someone can provide new perspectives and help overcome blocks.

Staying Motivated

Learn how to stay motivated:

- Track Your Progress: Tracking your progress can be a great motivational tool. Seeing how far you’ve come can encourage you to keep going.

- Seek Feedback: Sharing sections of your draft with trusted friends or other nonfiction authors provides encouragement and constructive feedback.

- Remember Your Purpose: Remind yourself why you started this project. Revisiting your initial inspiration can reignite your enthusiasm.

Writing the first draft of your nonfiction book involves starting with confidence, maintaining a disciplined routine, tackling challenges like writer’s block, and staying motivated throughout the process. This stage is less about perfection and more about bringing your ideas to life in a coherent structure. Remember, the first draft is just the beginning, and refinement comes later in the editing stages.

Editing and Revising

Editing and revising are about refining your first draft and enhancing its clarity, coherence, and overall quality. It involves scrutinizing and improving your manuscript at different levels, from overall structure to individual sentences.

The Importance of a Self-Editing Process

Read about self-editing.

- First Layer of Refinement: Self-editing is your first opportunity to review and improve your work. This process includes reorganizing sections, ensuring each chapter flows logically into the next, and checking for consistency in tone and style.

- Focus on Clarity and Conciseness: Look for areas where arguments can be made clearer, descriptions more vivid, and redundancies eliminated. It’s crucial to be concise and to the point in nonfiction writing.

Seeking Feedback

Here, you will read about basic tips for seeking feedback.

- Beta Readers and Writing Groups: Share your manuscript with trusted individuals representing your target audience. Beta readers or members of writing groups can provide invaluable feedback from a reader’s perspective.

- Constructive Criticism: Be open to constructive criticism. It can provide insights into areas you might have overlooked or not considered fully.

Hiring a Professional Editor

Here’s what to consider if you think you need a professional editor.

- When and Why It’s Necessary: A professional editor can bring a level of polish and expertise that’s hard to achieve on your own. They can help with structural issues, language clarity, and fact-checking. Consider hiring an editor, especially if you plan to self-publish.

- Types of Editing Services: Understand the different editing services available, including developmental editing, copyediting, and proofreading. Each serves a different purpose and is relevant at different stages of the revision process.

Revising Your Manuscript

Here, you’ll read about revising the manuscript.

- Iterative Process: Revision is an iterative process. It may require several rounds to get your manuscript to the desired quality.

- Attention to Detail: Check grammar, punctuation, and factual accuracy. Nonfiction books, in particular, need to be factually correct and well-cited.

- Incorporating Feedback: Integrate the feedback from your beta readers and editor judiciously. Balance maintaining your voice and message with addressing valid concerns and suggestions.

Editing and revising are where your manuscript transforms into its final form. This stage requires patience, attention to detail, and, often, external input. By embracing the editing and revising process, you can significantly enhance the quality of your nonfiction book, making it more engaging, credible, and polished.

Publishing Options

After writing, editing, and revising your nonfiction book, the next critical step in the how-to-write-a-nonfiction-book process is to decide how to publish it. Today, a nonfiction author has various options, each with its own set of advantages and challenges. Understanding these can help you choose the best path for your nonfiction book.

Traditional Publishing

Here, you can read about traditional publishing routes.

- Working with Literary Agents: Traditional publishing typically involves securing a literary agent to represent your book to publishers. An agent’s knowledge of the market and industry contacts can be invaluable.

- The Submission Process: This involves preparing a proposal and sample chapters to send to publishers, often through your agent. The process can be lengthy and competitive.

- Advantages: Traditional publishers offer editorial, design, and marketing support. They can also provide broader distribution channels.

- Considerations: It can be challenging to get accepted by a traditional publisher. They usually control the final product and a significant share of the profits.

Self-Publishing

Here, you can read about the possibility of self-published books.

- Complete Creative Control: Self-publishing gives you total control over every aspect of your book, from the content to the cover design and pricing.

- The Self-Publishing Process: This includes tasks like formatting the book, obtaining an ISBN, and choosing distribution channels (e.g., Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing).

- Marketing and Promotion: Self-publishing means you are responsible for marketing and promoting your book. This can be a significant task but also offers the opportunity for higher royalties per book sold.

- Accessibility: Platforms like Amazon, Smashwords, and Draft2Digital have made self-publishing more accessible, offering tools and services to assist authors.

Hybrid Publishing

The third option is hybrid publishing. Read more about it:

- Combination of Traditional and Self-Publishing: Hybrid publishing models combine elements of both traditional and self-publishing, offering more support than self-publishing alone but with more flexibility and control for the author.

- Costs and Services: These publishers often charge for their services, but they also offer professional editing, design, and marketing services.

Choosing the Right Option

Finally, here are tips for deciding exactly what the route to take:

- Consider Your Goals: Consider what you want to achieve with your book. Are you looking to reach a wide audience, maintain creative control, or see your book in bookstores?

- Understand Your Audience: Knowing where your target audience buys books can guide your choice. Some genres do exceptionally well in self-publishing, while others fare better with traditional publishers.

- Assess Your Resources: Consider your budget, available time for marketing, and your comfort level with the various aspects of the publishing process.

The choice between traditional, self-publishing, and hybrid options depends on your goals, resources, and the level of control and support you desire. Each path has its unique set of benefits and challenges, and understanding these can help you make an informed decision about the best way to bring your nonfiction book to your readers.

Marketing and Promotion

The success of a nonfiction book depends on effective marketing and promotion strategies. Here are tactics that you can use:

- Building an Author Platform: A strong author platform is essential for success in marketing. This involves establishing your online and offline presence, which can be achieved through a professional website, active social media profiles, blogging, and networking in relevant communities. An effective platform helps in building credibility and a loyal reader base.

- Effective Marketing Strategies: Developing and implementing a comprehensive marketing plan is key. This could include arranging book launch events, participating in speaking engagements, creating promotional content, and engaging in online marketing efforts. Tailoring these strategies to your target audience and leveraging the right channels are critical for maximum impact.

- Utilizing Social Media: Social media is a powerful tool for promoting your book. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn offer direct engagement with your audience. Regular posts, interactive content, and targeted ads on these platforms increase your book’s visibility and attract potential readers.

- Book Tours and Speaking Engagements: Conducting book tours and speaking at relevant events can enhance your book’s exposure. These engagements provide opportunities for personal interaction with your audience through physical events or virtual webinars and talks. They are effective in generating interest and boosting sales.

- Engaging with Media and PR: Media engagement is another vital aspect of book promotion. Reaching out to newspapers, magazines, radio, and TV programs related to your book’s topic can help gain wider exposure. Press releases, interviews, and book reviews are traditional yet effective ways to attract media attention.

- Email Marketing: Email marketing involves contacting your audience directly through newsletters and email campaigns. It’s an effective way to keep your readers informed about your book, upcoming events, and any new content you produce.

- Collaborations and Partnerships: Partnering with other authors, bloggers, and organizations can amplify your marketing efforts. These collaborations can include joint promotional events, guest blogging, or featuring on podcasts. Such partnerships can help you reach a broader audience and gain credibility in your field.

Here are the most frequently asked questions about how to write a nonfiction book.

1. How do I choose the right topic for my nonfiction book?

Choosing the right topic involves balancing your interests, expertise, and what readers are interested in. Consider topics you are passionate about and know well, then research the market to see if there’s a demand for information on these subjects. It’s also important to ensure there’s enough material available to write a comprehensive book on the topic.

2. How much research should I do for my nonfiction book?

The amount of research needed varies depending on the subject. However, gathering comprehensive and accurate information is vital to establish credibility and trust with your readers. Use a mix of primary and secondary sources and verify facts from multiple sources. Remember, in nonfiction, the quality and reliability of your information are as important as how you present it.

3. Should I write an outline before starting my nonfiction book?

Yes, creating an outline is highly recommended. An outline is a roadmap for your whole book idea, whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction. It ensures you cover all necessary points and maintain a logical flow throughout the book. Outlines can be modified as you write, but having a basic structure in place can significantly ease the writing process.

4. What are the key steps in editing and revising my nonfiction book?

Editing and revising involves several steps: First, conduct a self-edit to improve structure, clarity, and coherence. Next, get feedback from beta readers or a writing group. Finally, consider hiring a professional editor for developmental editing, copyediting, and proofreading. Pay attention to factual accuracy and consistency, and eliminate redundancies or unclear sections. Remember, editing and revising are crucial for enhancing the quality and readability of your book.

Related Posts

Published in What is Book Writing?

Join 5000+ Technical Writers

Get our #1 industry rated weekly technical writing reads newsletter.

The 5-Minute Nonfiction Chapter Outline

By Brannan Sirratt

Download the Math of Storytelling Infographic

“We need another chapter, don’t we?”

We were on the last leg of revisions, with a deadline at play, and the gap had just become clear. Painfully so. A serious pivot in the author’s life required a serious pivot in his Big Idea book (or Big Idea-lite, if you’re exploring that concept with me), and we didn’t have much time to do it. After a couple hours exploring possibilities, we’d found a way to pull the threads together, but it required another chapter. One we needed to get right—and we needed the chapter outline fast.

Theories about refining our work are fun to play with when time isn’t a factor, but when you’re on deadline, all that matters is one key skill: how to draft a nonfiction chapter, both quickly and effectively.

There are many reasons a deadline can pop up in your writing timeline, and it’s not easy to be your best creative self under the constraints of time and external pressure.

Then again, sometimes the pressure we’re up against is needed. Having too much time and too much room to explore can lead us to spin out in theoretical possibilities, trying to over-sharpen our ideas down to a nub before they ever have a chance.

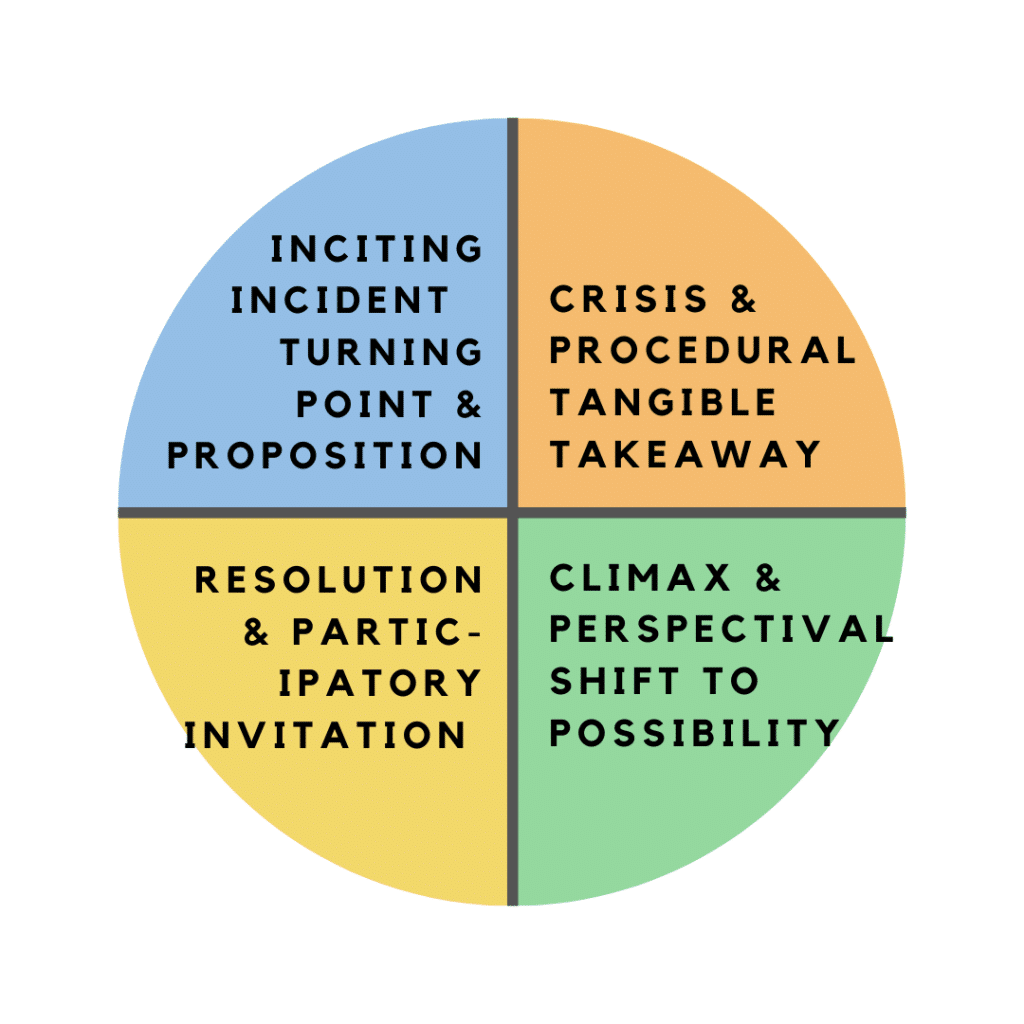

We’ve talked about the commandments of nonfiction storytelling , and how the different levels of quadrants can give us fresh angles on the way our work flows. And as all storytelling commandments go, these concepts apply at global, sequence, scene, and beat levels.