- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 15 October 2008

Chronic tophaceous gout presenting as acute arthritis during an acute illness: a case report

- Abhijeet Dhoble 1 ,

- Vijay Balakrishnan 1 &

- Robert Smith 1

Cases Journal volume 1 , Article number: 238 ( 2008 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

5 Citations

Metrics details

Gout is a metabolic disease that can manifest as acute or chronic arthritis, and deposition of urate crystals in connective tissue and kidneys. It can either manifest as acute arthritis or chronic tophaceous gout.

Case presentation

We present a 39-year-old male patient who developed acute arthritis during his hospital course. Later on, after a careful physical examination, patient was found to have chronic tophaceous gout. The acute episode was successfully treated with colchicines and indomethacin.

Gout usually flares up during an acute illness, and should be considered while evaluating acute mono articular arthritis. Rarely, it can also present with tophi as an initial manifestation.

Gout is a metabolic disease, which is characterized by acute or chronic arthritis, and deposition of monosodium urate crystals in joint, bones, soft tissues, and kidneys [ 1 – 4 ]. In 18 th century, Garrod proposed a causative relationship between elevated uric acid and urate crystal formation, which is underlying pathology for gout [ 4 ]. Gout can either manifest as acute arthritis or chronic arthropathy, which is also called tophaceous gout [ 1 , 2 , 5 ].

A 39-year-old African American male patient was admitted with one-day history of acute left lower quadrant pain, and was diagnosed with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis, confirmed by computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen. His medical and surgical history was unremarkable, and he denied any medication use. He denied smoking or illicit drug use, but admitted occasional alcohol use on every other weekend. He did not follow any particular diet. He had an average built with BMI of 29.6. He was started on intravenous antibiotics and pain medication, which led to significant clinical improvement within two days.

On the third day of hospitalization, he developed acute, severe pain and swelling of the left elbow. Within next few hours, pain worsened and he was unable to move the elbow joint, which was tender, erythematous, and swollen on examination (figure 1 ). Never investigated in the past, we also noted a firm 4 × 6 cm mass on each elbow, and another one surrounding the proximal inter-phalangeal joint of right middle finger (figure 2 ). There was no overlying edema or cellulitis. There were no other swellings or tophi noted especially on toes or ears. When asked particularly, he denied similar episodes in the past. He also denied any episode of swelling of great toe in the past.

Tophus at the back of right elbow.

Tophi/tophus around the proximal inter-phalangeal joint of right middle finger.

Plain radiography of left elbow showed joint effusion, and soft tissue swelling. Radiography of other joints including hands and feet was not performed. Laboratory values on the third day are given in table 1 . Liver function test was also performed, and the results were unremarkable. Diagnostic arthocentesis was performed on both the elbows, and revealed negatively birefringent needle-shaped crystals using polarized microscopy in both samples. Detailed analysis of synovial fluid is given in table 2 . The swelling on the right elbow was aspirated to determine the etiology because patient had that swelling for a long time.

The patient responded partially to colchicine, but later had great relief with indomethacin. Colchicine was used at the dose of 0.6 mg every two hourly. He received total of six doses, but it was stopped because he developed severe nausea and vomiting. He admitted that his pain was reduced to 4/10 in intensity from 9/10 before treatment, but swelling was persistent. We initiated indomethacin at 50 mg every eight hourly, and his pain and swelling was relieved to great extent in 48 hours.

Gout is a metabolic disease that can manifest as acute or chronic arthritis, and deposition of urate crystals in connective tissue and kidneys. All patients have hyperuricemia at some point of their disease. But, either normal or low serum uric acid levels can occur at the time of acute attack; and asymptomatic hyperuricemic individuals may never experience a clinical event resulting from urate crystal deposition [ 1 – 4 ]. Low to normal uric acid concentration can be due to excessive excretion of uric acid, crystal formation, or systemic inflammatory state [ 6 , 7 ]; however, exact mechanism is still not completely understood. A diagnosis of gout is most accurate when supported by visualization of uric acid crystals in a sample of joint or bursal fluid, or demonstrated histologically in excised tissue. Synovial fluid analysis of our patient was consistent with inflammatory arthritis. Mild leucocytosis in this patient was due to systemic inflammatory response.

Visible or palpable tophi, as this patient exhibited, are usually noted only among those patients who are hyperuricemic and have had repeated attacks of acute gout, often over many years. However, presentation of tophaceous deposits in the absence of gouty arthritis is also reported [ 5 , 8 ]. Pain and inflammation are manifested when uric acid crystals activate the humoral and cellular inflammatory processes [ 9 ].

During an acute illness, if systemic inflammatory state prevails, such as in an acute infection, cytokines and chemokines triggers inflammation and cause arthritis in the presence of urate crystals [ 10 , 11 ]. Phagocytosis of these crystals by macrophages in the synovial lining cells precedes influx of neutrophils in the joint [ 9 – 11 ]. This process releases various mediators of inflammation locally [ 12 , 13 ].

Hyperuricemia is often present in patients with tophaceous gout, and they can benefit from uric acid lowering therapy early during the course [ 14 , 15 ]. In our patient, serum uric acid and 24-hour urine uric acid level was within normal limits when measured in the hospital before his discharge from the hospital. It was decided to follow him up in the clinic in two weeks, and measure these values again during 'interval gout' before deciding to start him on any particular medication to prevent further attacks of acute arthritis.

Our patient presented with tophi as an initial presentation of gout, which is very rare, but has been reported [ 5 , 8 ]. Investigational studies due to acute elbow joint pain deciphered the underlying mystery of chronic swelling. Systemic inflammatory response secondary to diverticulitis exposed the joints to the effects of urate.

First-line treatments for an acute flare are either oral colchicine and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Systemic or intra-articular corticosteroids can also be used, and are equally effective, but with more side effects [ 16 , 17 ]. Interleukin-1 inhibitors are still under investigation, and are not approved for an acute attack of gout [ 18 ].

Gout usually flares up during an acute illness, and should always be considered while evaluating acute mono articular arthritis in hospitalized patients. Gout can present with tophi as an initial manifestation of the disease process.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images in Journal of Medical Case Reports. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Campion EW, Glynn RJ, DeLabry LO: Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Med. 1987, 82: 421-10.1016/0002-9343(87)90441-4.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hall AP, Barry PE, Dawber TR, McNamara PM: Epidemiology of gout and hyperuricemia: A long term population study. Am J Med. 1967, 42: 27-10.1016/0002-9343(67)90004-6.

Logan JA, Morrison E, McGill PE: Serum uric acid in acute gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997, 56: 696-7.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Garrod AB: The Nature and Treatment of Gout and Rheumatic Gout. 1863, 2

Google Scholar

Wernick R, Winkler C, Campbell S: Tophi as the initial manifestation of gout. Report of six cases and review of literature. Arch intern med. 1992, 152: 873-10.1001/archinte.152.4.873.

Urano W, Yamanaka H, Tsutani H, Nakajima H, Matsuda Y, Taniguchi A, Hara M, Kamatani N: The inflammatory process in the mechanism of decreased serum uric acid concentrations during acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002, 29 (9): 1950-3.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Simkin PA: The pathogenesis of podagra. Ann Intern Med. 1977, 86: 230.

Hollingworth P, Scott JT, Burry HC: Nonarticular gout: hyperuricemia and tophus formation without gouty arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1983, 26: 98-101. 10.1002/art.1780260117.

Beutler A, Schumacher HR: Gout and 'pseudogout': when are arthritic symptoms caused by crystal disposition?. Postgrad Med. 1994, 95: 103-6.

Schumacher HR, Phelps P, Agudelo CA: Urate crystal induced inflammation in dog joints: sequence of synovial changes. J Rheumatol. 1974, 1: 102.

Gordon TP, Kowanko IC, James M, Roberts-Thomson PJ: Monosodium urate crystal-induced prostaglandin synthesis in the rat subcutaneous air pouch. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1985, 3: 291.

Malawista SE, Duff GW, Atkins E, Cheung HS, McCarty DJ: Crystal-induced endogenous pyrogen production. A further look at gouty inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 1985, 28: 1039-10.1002/art.1780280911.

Falasca GF, Ramachandrula A, Kelley KA, O'onnor CR, Reginato AJ: Superoxide anion production and phagocytosis of crystals by cultured endothelial cells. Arthritis Rheum. 1993, 36: 105-10.1002/art.1780360118.

Sutaria S, Katbamna R, Underwood M: Effectiveness of interventions for the treatment of acute and prevention of recurrent gout – a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006, 45: 1422-10.1093/rheumatology/kel071.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wallace SL, Singer JZ: Therapy in gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1988, 14: 441.

Janssens HJ, Janssen M, Lisdonk van de EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C: Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 371 (9627): 1854-60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60799-0. 2008 May 31

Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Pascual E, Barskova V, Conaghan P, Gerster J, Jacobs J, Leeb B, Lioté F, McCarthy G, Netter P, Nuki G, Perez-Ruiz F, Pignone A, Pimentão J, Punzi L, Roddy E, Uhlig T, Zimmermann-Gòrska I, EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics: EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006, 65 (10): 1312-24. 10.1136/ard.2006.055269.

So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J: A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007, 9: R28-10.1186/ar2143.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank patient for giving us consent for the publication of the case report.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Internal Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, USA

Abhijeet Dhoble, Vijay Balakrishnan & Robert Smith

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Abhijeet Dhoble .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in collecting patient data, chart review, and editing medical images. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Authors’ original file for figure 2, rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dhoble, A., Balakrishnan, V. & Smith, R. Chronic tophaceous gout presenting as acute arthritis during an acute illness: a case report. Cases Journal 1 , 238 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-238

Download citation

Received : 09 October 2008

Accepted : 15 October 2008

Published : 15 October 2008

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-238

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Diverticulitis

- Serum Uric Acid

- Uric Acid Level

Cases Journal

ISSN: 1757-1626

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 06 January 2014

Gout in a 15-year-old boy with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a case study

- Hallie Morris 2 ,

- Kristen Grant 1 ,

- Geetika Khanna 3 &

- Andrew J White 4

Pediatric Rheumatology volume 12 , Article number: 1 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

14 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Joint pain is a common complaint in pediatrics and is most often attributed to overuse or injury. In the face of persistent, severe, or recurrent symptoms, the differential typically expands to include bony or structural causes versus rheumatologic conditions. Rarely, a child has two distinct causes for joint pain. In this case, an obese 15-year-old male was diagnosed with gout, a disease common in adults but virtually ignored in the field of pediatrics. The presence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) complicated and delayed the consideration of this second diagnosis. Indeed, the absence of gout from this patient’s differential diagnosis resulted in a greater than two-year delay in receiving treatment. The patients’ BMI was 47.4, and he was also mis-diagnosed with osteochondritis dissecans and underwent medical treatment for JIA, assorted imaging studies, and multiple surgical procedures before the key history of increased pain with red meat ingestion, noticed by the patient, and a subsequent elevated uric acid confirmed his ultimate diagnosis. With the increased prevalence of obesity in the adolescent population, the diagnosis of gout should be an important consideration in the differential diagnosis for an arthritic joint in an overweight patient, regardless of age.

In the pediatric population, there are numerous causes of joint pain, stiffness, and swelling. Many can be attributed to minor activity or overuse-related injury, especially in the overweight and obese populations [ 1 ], but in the face of persistent, severe, or recurrent symptoms, other diagnoses must be considered. These typically fall into two categories in children and adolescents: bony or structural causes [ 2 ], or rheumatologic conditions [ 3 ]. Careful history and physical examination, along with use of imaging and laboratory studies, can often distinguish between the two [ 4 , 5 ]; however, when a complete work-up is performed and no clear answer emerges, the differential must be expanded [ 6 ]. In the rare case in which a firm primary diagnosis has been made, it is more difficult still to consider additional, secondary, causes of joint pain.

The following case describes an adolescent young man with severe ankle pain, as well as multiple other joint complaints, who was correctly diagnosed and treated for polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. While the majority of his joints improved, his ankle continued to be extremely tender and swollen. After two years of aggressive medical treatment, surgical procedures, and multiple imaging studies, it was careful probing into his history and classic physical examination findings that ultimately led to the additional diagnosis of gout.

Case presentation

A 15-year-old obese Hispanic young man presented to the orthopedic surgery service with right-sided ankle pain. His pain began after a sports injury approximately one year prior to presentation but did not respond to immobilization, physical therapy, or prolonged rest. The pain was located at the medial side of the ankle, was worse with activity, and was accompanied by intermittent swelling. He took ibuprofen at night occasionally that provided modest relief.

His past medical history was unremarkable. Family history was negative for autoimmune disease including JIA. His only medication was occasional ibuprofen, and his immunizations were up to date.

On examination, the patient was heavyset, weighing 142.8 kg and standing 173.6 cm tall, with a BMI of 47.4. His vital signs were normal and he was in no distress. Musculoskeletal exam revealed bilateral limited ankle dorsiflexion, worse on the right. He had tenderness to palpation over the medial aspect of his ankle just anterior to the medial malleolus. All other joints were normal.

His initial work-up consisted of radiographs of his right ankle, showing evidence of a healing osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesion. He was instructed to continue physical therapy and follow up in three months with the possibility of arthroscopy of the affected joint if there was no improvement.

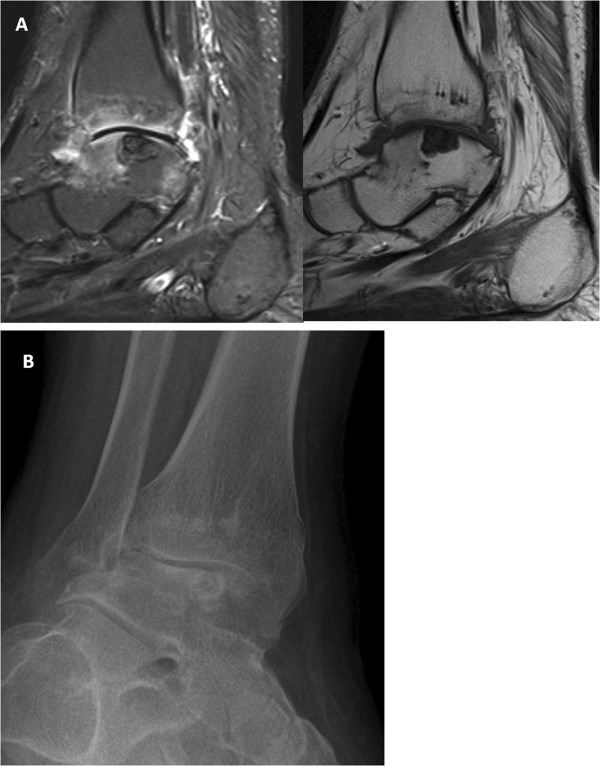

At follow-up, his pain was unchanged. Radiographs showed the previously seen presumed OCD lesion, now with a sclerotic border. He was scheduled for an MRI of the ankle, which was read as more consistent with a chondroblastoma versus an inflammatory process.

Several months later, he began complaining of left shoulder pain and decreased range of motion of gradual onset. He denied any trauma causing this new complaint. He was again seen by the orthopedic service and found to have significantly decreased range of motion and AC joint tenderness. Radiographs of the shoulder did not show any abnormalities. He was diagnosed with adhesive capsulitis and instructed to perform stretching exercises and take acetaminophen for pain. An MRI of the shoulder was performed given the unusual age of presentation for adhesive capsulitis, which revealed evidence of inflammation and synovitis consistent with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. He was referred to the rheumatology service.

The patient described daily pain and some morning stiffness for several weeks at a time, which would then subside for several weeks before returning. The pain and stiffness involved the right elbow, left knee, right wrist and several fingers in addition to the left shoulder and right ankle previously described. Examination by the pediatric rheumatologist noted improvement of his range of motion of the left shoulder with his home exercises and was back within normal limits. He did have moderate pain with extension of the shoulder. His left wrist was also tender with limited range of motion. His range of motion was limited bilaterally in the ankles and multiple PIP joints were painful and swollen. Considering the symmetric joint distribution, involvement of PIPs, and an elevated rheumatoid factor of 24.7 IV/mL (nl 0.0-13.9), the patient’s presentation was felt to be most consistent with early onset rheumatoid arthritis, or RF + polyarticular JIA. Subsequently, an anti-CCP antibody test was positive. He was prescribed naproxen and methotrexate. Laboratory studies from this initial visit were also notable for an elevated CRP 6.7 mg/dL, WBC 12.6 K/uL, Hgb of 12.3 g/dL, and ESR of 61 mm/hr. ANA, dsDNA, and HLA-B27 were negative.

The patient presented for follow-up approximately 2.5 months after beginning the naproxen and methotrexate regimen. At that time, the pain in the majority of his joints had improved substantially, however, the right ankle had become more tender and swollen. The pain was worse in the morning, to the point that he began using crutches. He was started on twice weekly etanercept injections, but when he experienced no relief, was subsequently switched to adalimumab and then to rituximab.

Given the lack of response of the patient’s ankle to this therapeutic regimen (Figure 1 ) over the course of the next year, despite improvement in his other joints, arthroscopic exploration of the right ankle with synovectomy and potential OCD curettage was performed. During surgery, the patient was found to have “significant debris” including a “crystalline white substance” within the joint space, which was attributed by the surgeons to “the previous steroid injection.” The fluid was not sent for culture, cell count or crystal studies, despite the fact that the patient had not ever received a steroid injection in that joint. The debris was removed, but not sent for pathology.

Imaging of gouty joint in an adolescent. (A) Synovitis on MRI with and without IV contrast of the right ankle with osteitis in the distal tibia and talar dome. Talar dome lesion was thought to represent an osteochondritis dissecans/osteonecrosis. (B) Radiographs performed 15 months later show marked joint space loss with persistent talar dome lesion which likely represents an intraosseous tophus.

After recovery from surgery, the patient returned to the rheumatology service for further management of his JIA. He continued to have pain and stiffness of his right ankle as well as several other joints that was difficult to manage. He was eventually started on a low dose of prednisone, previously avoided given his weight, which did offer moderate symptomatic relief. Ultimately the medication regimen of prednisone, etanercept, methotrexate, naproxen, and sulfasalazine had the greatest impact on his JIA symptoms, although his right ankle continued to be the most painful joint.

2.5 years after he first presented, the patient developed multiple non-tender scattered subcutaneous nodules over the extensor surface of his bilateral forearms, his left elbow, and his right knee (Figure 2 ). Their etiology was unclear, but attributed to rheumatoid nodules. Four months later, however, the patient spontaneously noted that his ankle pain seemed to worsen following the ingestion of red meat. With this new data in hand, a uric acid level was sent and was extremely elevated at 13.3 mg/dL. The nodules were deemed to be consistent with tophi, virtually pathognomonic for gout. The patient was started on colchicine and then allopurinol and improved. Over the course of time he did begin to complain of pain in his big toe, a more classic presentation of gout. Uric acid levels however, remained high, running between 11.7 and 13.5 mg/dL over the following year.

X-ray imaging of gouty tophus in an adolescent. Lateral view of the forearm shows subcutaneous nodules along the dorsal aspect of the proximal forearm.

At the time of the patient’s transition to adult care, he continued to exhibit active symptomatology, with joint pain in the knees, elbows, and ankles, limited range of motion in the aforementioned joints as well as his wrists, MCP’s and PIP’s, and difficulty ambulating. He continues to be treated for both JIA and gout.

Joint pain is a common complaint in pediatrics and in the face of persistent, severe, or recurrent symptoms, the differential typically expands to include bony or structural causes versus rheumatologic conditions. In this case, however, diagnosis was complicated because the child had two distinct etiologies causing joint pain. Moreover, the patient’s second diagnosis was gout, a very uncommon condition in a pediatric patient, even in the setting of morbid obesity.

Poly-articular juvenile idiopathic arthritis was considered as the unifying diagnosis when the patient presented with involvement of multiple joints. The typical presenting features of JIA are morning stiffness, pain and swelling of the joints, limited range of motion, and joint contractures [ 7 ]. Radiographs may show some soft tissue swelling and osteopenia early, with subchondral sclerosis and erosions evident after long-standing disease, but MRI has been shown to be more sensitive for bone marrow edema and tenosynovitis, as well as bone erosions, cartilage lesions, and synovial hypertrophy [ 8 ]. JIA is most often seen in children of European descent, but affects children throughout the world. The disease is thought to be idiopathic with its cause poorly understood, although there is mounting evidence that autoimmunity may be involved [ 7 ]. There is also thought to be potential genetic susceptibility in affected individuals [ 9 ]. While the majority of the patient’s overall complaints did seem to fit the diagnosis of JIA both in his clinical presentation and laboratory and imaging results, as well as his response to treatment, his right ankle continued to be refractory to treatment.

The acquisition of additional history led to the consideration of gout as a second diagnosis. Historically, gout has affected predominantly older, overweight men but in more recent years the male to female ratio has fallen to 2:1 [ 10 ]. A resurgence of gout across the population has been noted in recent years, and juvenile gout has also begun to be reported, with many of the cases being due solely to known risk factors such as being overweight [ 11 , 12 ]. On imaging, plain films may show little evidence of gout in early stages, but later in the course can show joint effusions, bony erosions, or tophi within the joint. Gout can appear similar to other arthritides on MRI, with mild bone marrow edema, tenosynovitis, and bony erosions, making diagnosis difficult but important to consider, especially in the setting of an overweight or obese patient. However, if tophi are present, MRI is able to detect this as a potentially differentiating characteristic. Other imaging studies may be of more use to differentiate gout from other diagnoses, as ultrasound may be able to detect crystals within the joint space, and can even differentiate between gout and pseudogout [ 13 ]. The gold standard for diagnosing gout remains the acquisition of urate crystals from synovial fluid. In the absence of this data, however, the presence of 2 of the 3 Rome clinical criteria (uric acid >7.0 mg/dL, history of painful joint with abrupt onset and remission within 2 weeks, and presence of tophus), as were existent in our patient, was found to have a positive predictive value of 76.9%, and a specificity of 88.5% [ 14 ].

While it seems likely the patient did have gout, gout alone does not seem most likely given the clinical picture. Gout simulating JIA is a possibility; a patient with untreated gout can develop bony erosions and deformities, leading to the disappearance of the intercritical periods which are usually pathognomonic of gout. Typically, however, one would expect gout to present as an episodic arthritis. Even in untreated individuals, complete resolution of the earliest attacks nearly always occurs within several weeks, which this patient never experienced. Moreover, the symmetric joint distribution with involvement of the PIPs along with a positive rheumatoid factor and CCP antibody point toward the concurrent JIA diagnosis in this case.

There were several missed opportunities to diagnose this patient earlier in his course. First, gout was not considered as a part of the original differential because of its propensity to affect older individuals. As the epidemic of childhood obesity grows, adult conditions usually a result of long term lifestyle consequences are being seen more frequently in the pediatric population, most notably type II diabetes but also musculoskeletal complaints and, as in this case, gout.

Secondly, if gout had been on the differential, the radiologic features may have been recognized as being consistent with this condition. Third, a uric acid level was not sent until after the additional diet history was obtained. And finally, proper examination of joint fluid, from either aspiration or surgical debridement, would have revealed the presence of negatively birefringent crystals, providing a timely diagnosis.

In conclusion, gout was diagnosed in this teenage patient with longstanding juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The diagnosis of gout should therefore be an important element of the differential for a refractory painful joint in an overweight patient regardless of age, and regardless of pre-existing diagnoses. Failing to consider this diagnosis may result in delay of optimal treatment and cause long-term effects of bone erosion and joint destruction. Sending joint fluid for crystalline analysis, checking uric acid levels, and performing imaging studies, specifically non-invasive, cost effective modalities such as ultrasound, are all reasonable parts of a complete work-up in any child with arthritis.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Deere KC: Obesity is a risk factor for musculoskeletal pain in adolescents: findings from a population-based cohort. Pain. 2012, 153 (9): 1932-1938. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.06.006.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Amendola A, Panarella L: Osteochondral lesions: medial vs. lateral, persistent pain, cartilage restoration options and indications. Foot Ankle Clin. 2009, 14 (2): 215-227. 10.1016/j.fcl.2009.03.004.

Jennings F, Lambert E, Fredericson M: Rheumatologic diseases presenting as sports-related injuries. Sports Med. 2008, 38 (11): 917-930. 10.2165/00007256-200838110-00003.

Punaro M: Rheumatologic conditions in children who may present to the orthopaedic surgeon. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011, 19 (3): 163-169.

PubMed Google Scholar

Wukich DK, Tuason DA: Diagnosis and treatment of chronic ankle pain. Instr Course Lect. 2011, 60: 335-350.

Choudhary S, McNally E: Review of common and unusual causes of lateral ankle pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2011, 40 (11): 1399-1413. 10.1007/s00256-010-1040-z.

Gowdie PJ, Tse SM: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012, 59 (2): 301-327. 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.03.014.

Breton S, Jousse-Joulin S, Finel E, Marhadour T, Colin D, de Parscau L, Devauchelle-Pensec V: Imaging approaches for evaluating peripheral joint abnormalities in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 41 (5): 698-711. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.08.004.

Prahalad S, Conneely KN, Jiang Y, Sudman M, Wallace CA, Brown MR: Susceptibility to childhood onset rheumatoid arthritis: investigation of a weighted genetic risk score that integrates cumulative effects of variants at five genetic loci. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65 (6): 1663-1667. 10.1002/art.37913.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Zampogna G, Andracco R, Parodi M, Cutolo M, Cimmino MA: Has the clinical spectrum of gout changed over the last decades?. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012, 30 (3): 414-416.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Chen SY, Shen ML: Juvenile gout in Taiwan associated with family history and overweight. J Rheumatol. 2007, 34 (11): 2308-2311.

Kedar E, Simkin PA: A perspective on diet and gout. Adv Chronic Kidnet Dis. 2012, 19 (6): 392-397. 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.07.011.

Article Google Scholar

Dalbeth N, Doyle AJ: Imaging of gout: an overview. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012, 26 (6): 823-838. 10.1016/j.berh.2012.09.003.

Malik A, Schumacher HR, Dinnella JE, Clayburne GM: Clinical diagnostic criteria for gout: comparison with the gold standard of synovial fluid analysis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009, 15 (1): 22-24. 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181945b79.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Boston Combined Residency Program, PGY1, Boston, Mass, USA

Kristen Grant

Washington University School of Medicine, WUSM IV, St Louis, Missouri, USA

Hallie Morris

Division of Radiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri, USA

Geetika Khanna

Division of Pediatric Rheumatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri, USA

Andrew J White

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrew J White .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KG participated in background research and drafting of the manuscript. HM was involved in drafting and revision of the manuscript. GK contributed figures and their impressions. AW conceived of the study, participated in its coordination, and was involved in drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Authors’ original file for figure 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Morris, H., Grant, K., Khanna, G. et al. Gout in a 15-year-old boy with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a case study. Pediatr Rheumatol 12 , 1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-12-1

Download citation

Received : 14 October 2013

Accepted : 24 December 2013

Published : 06 January 2014

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-12-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- Osteochondritis dissecans

- Treatment failure

Pediatric Rheumatology

ISSN: 1546-0096

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2021

Severe erosive lesion of the glenoid in gouty shoulder arthritis: a case report and review of the literature

- Huricha Bao 1 na1 ,

- Yansong Qi 1 na1 ,

- Baogang Wei 1 ,

- Bingxian Ma 1 ,

- Yongxiang Wang 1 &

- Yongsheng Xu 1

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders volume 22 , Article number: 343 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7479 Accesses

7 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Gout is a metabolic disease characterized by recurrent episodes of acute arthritis. Gout has been reported in many locations but is rarely localized in the shoulder joint. We describe a rare case of gouty arthritis involving bilateral shoulder joints and leading to severe destructive changes in the right shoulder glenoid.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old male was referred for pain and weakness in the right shoulder joint for two years, and the pain had increased in severity over the course of approximately nine months. A clinical examination revealed gout nodules on both feet and elbows. A laboratory examination showed a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), high levels of C-reactive protein and hyperuricemia, and an imaging examination showed severe osteolytic destruction of the right shoulder glenoid and posterior humeral head subluxation. In addition, the left humeral head was involved and had a lytic lesion. Because a definite diagnosis could not be made for this patient, a right shoulder biopsy was performed. The pathological examination of the specimen revealed uric acid crystal deposits and granulomatous inflammation surrounding the deposits. After excluding infectious and neoplastic diseases, the patient was finally diagnosed with gouty shoulder arthritis.

Conclusions

Gout affecting the bilateral shoulder joints is exceedingly uncommon, and to our knowledge, severe erosion of the glenoid has not been previously reported. When severe erosion is present, physicians and orthopedic surgeons should consider gouty shoulder arthritis according to previous medical history and clinical manifestations.

Peer Review reports

Gouty arthritis is usually monoarticular and frequently involves the synovial joints of the feet and hands and, rarely, the shoulders [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Monosodium urate crystals produce an inflammatory response that generally results in swollen, tender, hot joints. As described in the literature, the manifestations of shoulder gout are tophaceous deposits in the rotator cuff, intraosseous tophi in the humeral head, and tophi in the bursa around the shoulder joint [ 4 , 5 ]. Here, we report a rare case of gout involving bilateral shoulder joints that caused severe erosion of the right shoulder glenoid. In the clinical diagnosis and treatment process, gout may be misdiagnosed as degenerative, infectious arthritis or a malignancy, resulting in delays in diagnosis and treatment. To date, only four cases of shoulder gout have been reported in the English-language literature identified in PubMed, and we provide a brief literature review concerning shoulder gout [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The patient was informed that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication, and he provided consent.

A right-hand-dominant, 62-year-old obese man presented to our department due to progressive right shoulder pain and weakness. There was no history of recent trauma to the right shoulder. He had a 2-year history of intermittent pain in the right shoulder. Nine months prior, he started to experience worsening pain and weakness in the right shoulder with the restriction of active shoulder motion. He had been treated with conservative treatment (acupuncture, physical therapy, and subacromial steroid injections), which provided short periods of relief. The pain did not disappear, and he visited our hospital for further examination and treatment.

His past medical history included right clavicle fracture, hypertension, and gout. Thirty-six years prior, he suffered a right clavicle middle-shaft fracture that was treated conservatively with a figure-of-eight bandage. The patient recalled that there was no abnormality in the right shoulder at that time. He had a 20-year history of long-standing but suboptimally treated gout, and the gout intermittently led to redness and pain in the feet, which occurred 4–5 times a year. The symptoms were relieved by colchicine during acute episodes, and no systemic treatment was given. The patient had a body mass index of 31.9 kg/m 2 and no previous history of tuberculosis. The patient consumed excessive alcohol and had an alcohol consumption history of 250 ml/day for 30 years; additionally, he smoked 20 cigarettes a day for 35 years and followed no particular diet.

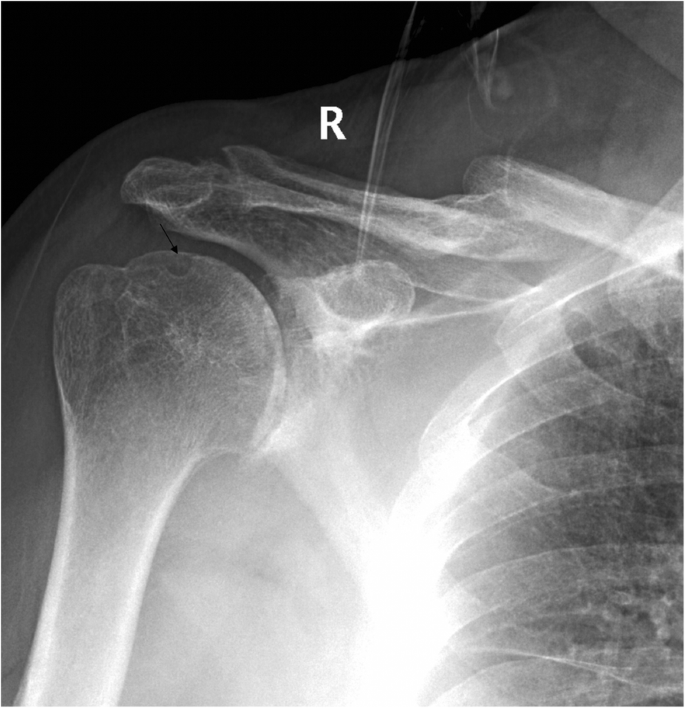

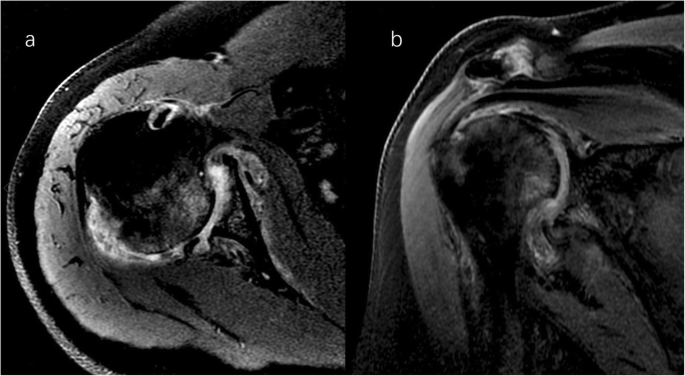

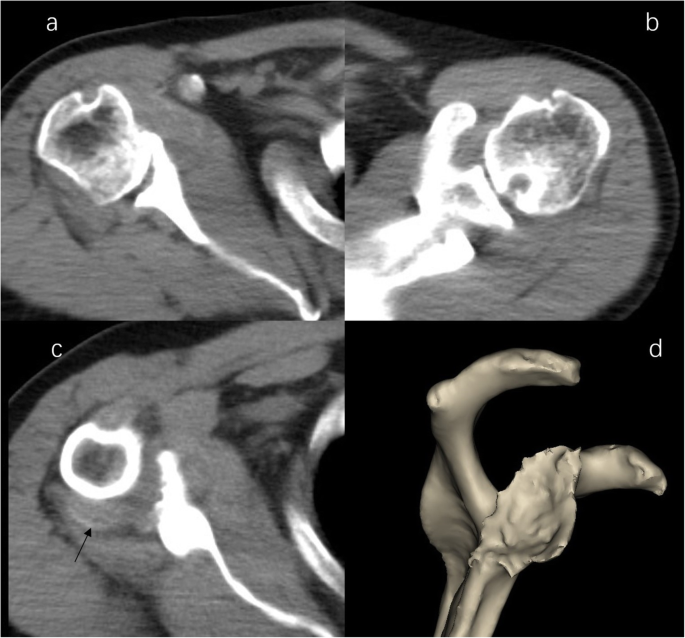

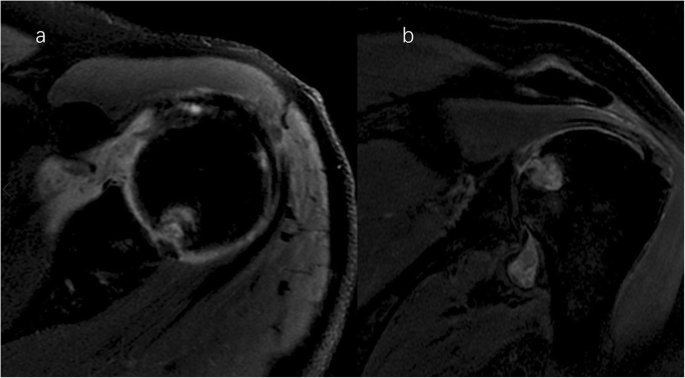

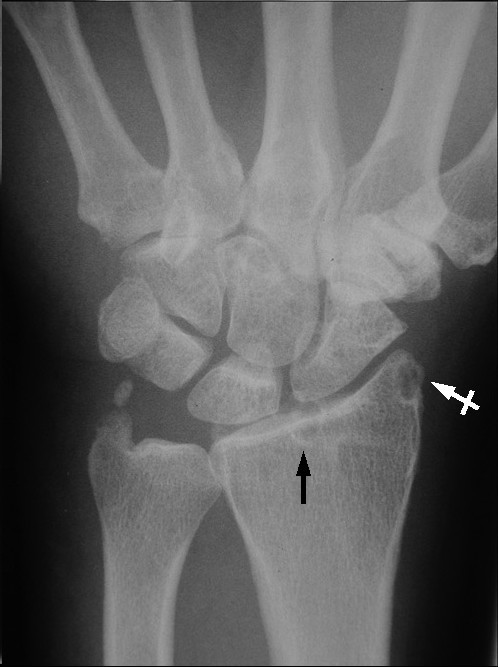

A clinical evaluation revealed that his right shoulder joint had a limited active range of motion, and the passive range of motion was nearly normal. On palpation, tenderness was noted in the anterior and posterior aspects of the shoulder joint, and there was no warmth, erythema, swelling, or redness. When the patient’s upper limb was raised, abducted, and externally rotated, the shoulder joint had a sense of movement, and there were a popping sound and a feeling of shoulder reduction. Gouty tophi were observed on the dorsal aspect of the bilateral great toe and extensor aspect of the bilateral elbows; all of the patient’s other joints were clinically normal, and the examination revealed nothing else of note. Plain radiographs of the affected shoulder showed glenohumeral joint space narrowing, erosions of the glenoid, and osteophyte formation on the inferior aspect of the glenoid. At the superolateral point of the humeral head, a lytic lesion (arrow) was detected, and malunion of the right clavicle fracture was also seen (Fig. 1 ). To assess the integrity of the soft tissue of the shoulder joint, we ordered a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination, which revealed that the axial and coronal proton density-weighted, fat-suppressed MRI exhibited an intact rotator cuff, joint effusion, synovial proliferation, effusion within the biceps long head tendon sheath, humoral head superolateral cystic erosion, posterior humeral head subluxation, and severe glenoid erosion (Fig. 2 ). A laboratory examination revealed an elevated uric acid level of 594 µmol/L (normal range 208.00-428.00 µmol/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 65 mm/h, C-reactive protein level of 34 mg/L, leukocyte count of 8.35 × 10 9 /L, and hemoglobin level of 12.8 g/dL. The patient had a negative test for rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs). The liver and kidney function of the patient were normal. No abnormalities were found on electromyography of the upper extremities. In consideration of the possibility of shoulder joint infection or malignancy, arthrocentesis was performed, and 20 ml of fluid was aspirated. The fluid was macroscopically cloudy and yellow. The synovial analysis revealed an inflammatory cell count with leukocytes 5200/mm 3 , which were predominantly neutrophils. Gram staining of the fluid was negative, and no organisms were cultured. A cytology analysis and the joint fluid Xpert MTB/RIF test were negative. A polarizing microscope was not available in our hospital; therefore, we could not examine the synovial fluid for crystals.

Plain radiographs of the right shoulder showed glenohumeral joint space narrowing and osteophyte formation on the inferior aspect of the glenoid. At the superolateral point of the humeral head, a lytic lesion (arrow) was detected, and malunion of the right clavicle fracture was also seen

Right shoulder magnetic resonance imaging (proton density-weighted fat-suppressed sequence ). Axial ( a ) and coronal ( b ) views revealed intact rotator cuff, joint effusion, synovial proliferation, effusion within the biceps long head tendon sheath, humoral head superolateral cystic erosion, posterior humeral head subluxation, and severe glenoid erosion

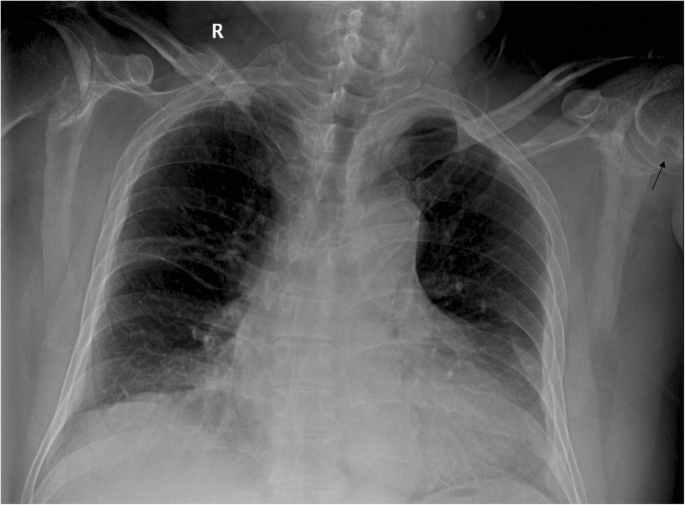

The plain radiograph of the chest showed no neoplastic or tuberculous changes. Serendipitously, the radiograph revealed a round contour lytic lesion in the left humeral head with sclerotic borders near the articular surface (Fig. 3 ). Therefore, a bilateral shoulder joint computed tomography (CT) scan and left shoulder MRI examination were performed. An infectious shoulder etiology appeared unlikely, and differential diagnoses included destructive arthritis or neoplastic lesions. Ultrasound and dual-energy CT imaging of the shoulder joints were not performed on this patient.

The plain radiograph of the chest showed no neoplastic or tuberculous changes. Serendipitously, the radiograph revealed a round contour lytic lesion (arrow) in the left humeral head with sclerotic borders near the articular surface

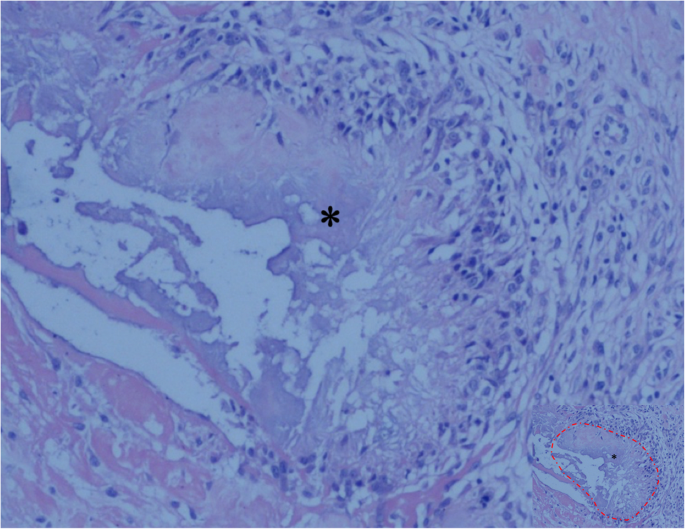

The CT scan demonstrated severe destructive lytic changes at the glenoid and erosive lesions and posterior subluxation of the humeral head in the right shoulder. A faint amorphous opacity could also be seen at the posterior capsule of the right shoulder. Circular lytic lesions in the left humeral head with sclerotic borders near the articular surface broke through the articular cartilage (Fig. 4 ). Left shoulder MRI revealed that the axial and coronal proton density-weighted, fat-suppressed MRI showed effusion, lytic destruction of the subchondral bone of the humeral head, erosion, and collapse of the articular cartilage medial to the lesion (Fig. 5 ). However, we still could not determine the cause of the bony destruction of the shoulder joint. Therefore, several biopsies were taken from the capsule and synovial membrane of the right shoulder. The biopsy showed inflammatory cells and gout crystals, and there was no evidence of malignancy or tuberculosis (Fig. 6 ). Based on these findings, we made a diagnosis of gouty arthritis of the bilateral shoulder. Etoricoxib and febuxostat treatment improved the patient’s clinical condition. The patient refused surgical intervention and decided to continue receiving physical therapy and medication for symptom control. After physical therapy and medication, the pain in the right shoulder diminished further but was not eliminated.

CT image of shoulder. b Right shoulder CT image demonstrated severe destructive lytic changes at the glenoid and erosive lesions and posterior subluxation of the humeral head in the right shoulder. b Left shoulder CT image shows a circular lytic lesion in the left humeral head with sclerotic borders near the articular surface broke through the articular cartilage. c a faint amorphous opacity (arrow) be seen at the posterior capsule of right shoulder. d 3D image shows severe destructive defect of the right shoulder glenoid

Light shoulder magnetic resonance imaging (proton density-weighted fat-suppressed sequence ). Axial ( a ) and coronal ( b ) MRI image demonstrate effusion, cystic destruction of the subchondral bone of the humeral head, erosion, and collapse of articular cartilage medial to the lesion

Tissue specimen from the right shoulder showing the deposition of uric acid crystals (asterisk, the part marked with a red dashed line in image with reduced size) surrounded by granulomatous inflammation, and there was no evidence of malignancy or tuberculosis (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×100)

Discussion and conclusions

Gout is a common inflammatory joint disease characterized by monosodium urate crystal deposition in joints and connective tissue. Gout often affects the feet, hands, elbows, and knees and is relatively uncommon in the shoulder joint. We presented a rare case of gouty arthritis involving bilateral shoulder joints and leading to severe destructive changes in the right shoulder glenoid.

The clinical stage of gout is divided into asymptomatic hyperuricemia, acute gouty arthritis, the intercritical period, and chronic tophaceous gout [ 8 ]. The typical clinical manifestation of acute gouty arthritis is characterized by sudden, severe pain, swelling, redness, and tenderness in the joints. Poorly controlled gout may develop into chronic tophaceous gout, and long-standing gout may present with more atypical symptoms. A chronic deposition of monosodium urate crystals in joints and other body tissues can manifest as a wide array of presentations and can lead to severe joint damage. Such atypical presentations are likely a result of the complexity of reasons. In our case, the patient’s symptoms were pain and weakness in the right shoulder, and the onset of symptoms was relatively insidious, while the patient’s left shoulder joint did not have any clinical symptoms or discomfort. A plain radiograph of the patient’s right shoulder joint revealed degenerative changes, including glenohumeral joint space narrowing, erosion, and osteophyte formation on the glenoid, with a lytic lesion on the humeral head. The left shoulder showed an osteolytic lesion of the humeral head. MRI revealed an intact rotator cuff, inflammatory synovitis, humoral head cystic erosion, posterior humerus subluxation, and a severe glenoid defect. The CT scan further confirmed the severe bone erosive defect of the right shoulder glenoid and posterior humeral head subluxation. From the CT scan, we also observed a round contour lytic lesion with sclerotic borders near the articular surface in the left humeral head. We did not find obvious intra- or extra-articular gout crystal deposition on plain radiographs, CT scans, or MRI images of the bilateral shoulder joints, except in the bilateral humeral head and at the posterior capsule of the right shoulder.

Radiological characteristics of chronic gouty arthritis include punched-out erosions with overhanging cortex and sclerotic margins, preservation of joint space, and dense nodules of soft tissues, which are sometimes calcified [ 9 ]. The typical MRI manifestations of tophaceous gouty arthritis are homogeneous intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and heterogeneous intermediate-to-low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, depending on the calcium concentration within a tophus [ 10 ]. There are several descriptions of gouty shoulder arthritis in the literature, as well as rare cases of coexisting gout and septic shoulder arthritis. Sean et al. first reported a case of subacromial impingement caused by tophaceous gout of the rotator cuff. There was no abnormality on MRI except supraspinatus tendonitis. Arthroscopic findings revealed tophaceous deposits of the supraspinatus and subscapularis tendon [ 4 ]. Chao et al. reported a case of tophaceous gout involving the rotator cuff. In this case, the patient complained of intermittent pain and a limited range of motion of the right shoulder after a shoulder injury. A plain radiograph of the right shoulder demonstrated a faint amorphous opacity above the humeral head. MRI revealed urate crystal deposits in intrasubstance areas and the articular side of the supraspinatus tendon [ 5 ]. Toru et al. reported the coexistence of gouty and septic shoulder arthritis after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair surgery. The patient developed a high fever postoperatively, and at the same time, the left shoulder presented pain, swelling, and warmth. However, the article did not describe the imaging manifestations of the shoulder joint [ 6 ]. Ana et al. reported a case of tophaceous gout of the right shoulder joint. The patient presented with pain in the right shoulder with certain movements and when lying on his affected shoulder at night. A plain radiograph of the shoulder joint showed a punched-out eccentric bony erosion in the clavicle region of the right acromioclavicular joint and irregular opacity occupying the subacromiodeltoid bursa. MRI showed tophi deposits along the upper ridge of the distal end of the clavicle and in the subacromiodeltoid bursa [ 7 ]. Gouty arthritis of the shoulder joint, as described in the literature, is presented as tophaceous gout of the rotator cuff, causing subacromial impingement or rotator cuff tendinitis and shoulder dysfunction. In our case, the patient had no distinct appearance of acute arthritis, and there was severe bone destruction of the glenoid, resulting in severe dysfunction of the right shoulder joint. The gold standard for diagnosing gout is identifying characteristic monosodium urate crystals in the synovial fluid using polarized microscopy. During the patient’s diagnosis process, we considered the possibility of the patient suffering from gouty shoulder arthritis. Since a polarizing microscope was not available in our hospital, the diagnosis of gouty arthritis needed to be confirmed by clinical symptoms or histopathological analysis. The patient’s shoulder bone tissue was severely damaged, and at the same time, there was not a typical presentation of gouty arthritis. Therefore, we focused more attention on the possibility of shoulder neoplasia or infection. After diagnosing the case through histological examination, we carefully observed the patient’s imaging data. We found the typical features of gout: centralized erosions, sclerotic rim, and overhanging edges on the plain radiograph and CT.

In clinical work, gouty arthritis should be considered in patients who present with shoulder pain, weakness, and limited mobility, especially patients who have no distinct appearance of acute arthritis and have severe bone destruction of the shoulder joint. The differentiation of gouty arthritis from infectious arthritis or osteomyelitis is not always easy. It is necessary to exclude other possible etiologies, such as infection, neoplasia, and bone destructive disease. The following conditions must be considered in differential diagnosis: septic shoulder arthritis is associated with acute inflammation, redness, swelling, and pain; laboratory tests have a high percentage of white blood cells and neutrophils, and joint fluid examination will indicate microbes or pus cells. Tuberculous shoulder arthritis manifests as pain, dysfunction, muscular atrophy, and fistula; patients also have systemic symptoms of tuberculosis and are positive for the Xpert test [ 11 ]. Rapid destructive arthropathy of the shoulder joint is described as follows: the course of the disease develops rapidly; and there is bone destruction and tearing of the rotator cuff [ 12 ]. Milwaukee shoulder is a destructive calcium phosphate crystalline arthropathy related to the following factors: trauma or overuse, calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate crystal deposition, neuroarthropathy, dialysis arthropathy, denervation, female sex, and advanced age. The imaging findings are as follows: narrowing of the joint space, subchondral bone sclerosis with cystic changes, subchondral bone destruction, soft tissue swelling, calcification of the joint capsule, free bodies in the joint cavity, rotator cuff tears, and massive haemorrhagic joint effusion [ 13 ].

In this study, the patient’s shoulder joint pathology was insidious, and no apparent acute gout episodes occurred during the entire course of the disease; the condition mainly manifested as chronic arthritis, with right shoulder pain, weakness, and limited mobility. Although the patient had a history of gout, there had been no gout attacks in the shoulder joint; the attacks were mainly manifested in the bilateral feet. Additionally, it was found that the left shoulder joint was also affected by a gouty attack. However, there were no clinical symptoms, which caused some confusion and challenges regarding the diagnosis and treatment. The possibility of gouty arthritis was not initially considered. The patient had a long history of gout, with 2–3 attacks per year, mainly manifested in the bilateral feet, but there were no obvious gout attacks in other parts of the body. Only colchicine was taken orally during the gout attack periods to relieve the symptoms. The patient did not receive an effective and systematic treatment of gout. We believe that the severe destruction of the glenoid was related to an unhealthy diet and the lack of effective and systematic treatment. With effective therapy earlier in the disease process, severe bone destruction of the shoulder bone tissue can be avoided. This condition can lead to significant debilitation in patients if not identified early and managed appropriately.

Gouty arthritis involves the shoulder joint relatively rarely, and cases of osteolytic destruction of the bone tissue of the shoulder joint are rare. Gouty arthritis of the shoulder with severe bone destruction is easily misdiagnosed as a shoulder tumor or infectious disease. In conclusion, although gouty shoulder arthritis is considered unusual, when a patient has a history of gout, atypical manifestations, and severe erosive lesions of the glenoid in the shoulder joint, physicians and orthopedic surgeons should consider the possibility of gout causing severe lesions that mimic infection or neoplastic disease (Table 1 ). This case study aimed to alert physicians to the unusual manifestations and presentations of gouty arthritis, which could be missed if there is no suspicion.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Computed tomography

Magnetic resonance imaging

Alqatari S, Visevic R, Marshall N, Ryan J, Murphy G. An unexpected cause of sacroiliitis in a patient with gout and chronic psoriasis with inflammatory arthritis: a case report. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):126.

Article Google Scholar

Singh JA, Gaffo A. Gout epidemiology and comorbidities. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(Suppl 3):11–6.

Dehlin M, Jacobsson L, Roddy E. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence, treatment patterns and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(7):380–90.

O’leary ST, Goldberg JA, Walsh WR. Tophaceous gout of the rotator cuff: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(2):200–1.

Chang CH, Lu CH, Yu CW, Wu MZ, Hsu CY, Shih TT. Tophaceous gout of the rotator cuff. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):178–82.

Ichiseki T, Ueda S, Matsumoto T. Rare coexistence of gouty and septic arthritis after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(3):4718–20.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tierra Rodriguez AM, Pantoja Zarza L, Brañanova López P, Diez Morrondo C. Tophaceous gout of the shoulder joint. Reumatol Clin. 2019;15(5):e55-6.

Ragab G, Elshahaly M, Bardin T. Gout: An old disease in new perspective - A review. J Adv Res. 2017;8(5):495–511.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Gentili A. The advanced imaging of gouty tophi. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8(3):231–5.

McQueen FM, Doyle A, Dalbeth N. Imaging in gout–what can we learn from MRI, CT, DECT and US. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(6):246.

Longo UG, Marinozzi A, Cazzato L, Rabitti C, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Tuberculosis of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):e19–21.

Kekatpure AL, Sun JH, Sim GB, Chun JM, Jeon IH. Rapidly destructive arthrosis of the shoulder joints: radiographic, magnetic resonance imaging, and histopathologic findings. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):922–7.

Nadarajah CV, Weichert I. Milwaukee shoulder syndrome. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:458708.

Towiwat P, Chhana A, Dalbeth N. The anatomical pathology of gout: a systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):140.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank American Journal Experts for their language editing, which greatly improved the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 81560374 and 81960399, and the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia under Grants 2018BS08002 and 2020MS03064.

Author information

Huricha Bao and Yansong Qi contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Orthopedics, Inner Mongolia People’s Hospital, No. 20 Zhao Wu Da Street, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, 010017, Hohhot, China

Huricha Bao, Yansong Qi, Baogang Wei, Bingxian Ma, Yongxiang Wang & Yongsheng Xu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HRCB collected the patient’s clinical data and wrote the manuscript. YSQ critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. BGW was involved in the pathological data collection. BXM and YXW were involved in the clinical case data collection. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript. YSX was responsible for the clinical management of the patient and the drafting and editing of the manuscript. All authors are aware of the manuscript submitted and they all agreed on it.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yongsheng Xu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Clinical Investigation in the Inner Mongolia People’s Hospital.

Consent for publication

A written informed consent form for participation in the case was obtained from the patient. he is aware of this case report and the possibility of it being published.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bao, H., Qi, Y., Wei, B. et al. Severe erosive lesion of the glenoid in gouty shoulder arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22 , 343 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04217-5

Download citation

Received : 18 August 2020

Accepted : 03 April 2021

Published : 12 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04217-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders

ISSN: 1471-2474

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Establishment of a clinical diagnostic model for gouty arthritis based on the serum biochemical profile: A case-control study

Affiliations.

- 1 National Pharmaceutical Engineering Center for Solid Preparation in Chinese Herbal Medicine, Jiangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

- 2 Department of Pathology, Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital, People's Hospital of Hangzhou Medical College, Hangzhou.

- 3 State Key Laboratory of Innovative Drug and Efficient Energy-Saving Pharmaceutical Equipment, Nanchang, China.

- PMID: 33879701

- PMCID: PMC8078334

- DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025542

The disease progression of gouty arthritis (GA) is relatively clear, with the 4 stages of hyperuricemia (HUA), acute gouty arthritis (AGA), gouty arthritis during the intermittent period (GIP), and chronic gouty arthritis (CGA). This paper attempts to construct a clinical diagnostic model based on blood routine test data, in order to avoid the need for bursa fluid examination and other tedious steps, and at the same time to predict the development direction of GA.Serum samples from 579 subjects were collected within 3 years in this study and were divided into a training set (n = 379) and validation set (n = 200). After a series of multivariate statistical analyses, the serum biochemical profile was obtained, which could effectively distinguish different stages of GA. A clinical diagnosis model based on the biochemical index of the training set was established to maximize the probability of the stage as a diagnosis, and the serum biochemical data from 200 patients were used for validation.The total area under the curve (AUC) of the clinical diagnostic model was 0.9534, and the AUCs of the 5 models were 0.9814 (Control), 0.9288 (HUA), 0.9752 (AGA), 0.9056 (GIP), and 0.9759 (CGA). The kappa coefficient of the clinical diagnostic model was 0.80.This clinical diagnostic model could be applied clinically and in research to improve the accuracy of the identification of the different stages of GA. Meanwhile, the serum biochemical profile revealed by this study could be used to assist the clinical diagnosis and prediction of GA.

Copyright © 2021 the Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Publication types

- Validation Study

- Area Under Curve

- Arthritis, Gouty / diagnosis*

- Arthritis, Gouty / etiology

- Biomarkers / blood

- Blood Sedimentation

- Blood Urea Nitrogen

- C-Reactive Protein / analysis

- Case-Control Studies

- Clinical Decision Rules*

- Disease Progression

- Hematologic Tests / statistics & numerical data*

- Hyperuricemia / blood

- Hyperuricemia / complications

- Least-Squares Analysis

- Leukocyte Count

- Lipoproteins, HDL / blood

- Middle Aged

- Multivariate Analysis

- Predictive Value of Tests

- Principal Component Analysis

- Regression Analysis

- Reproducibility of Results

- Uric Acid / blood

- Lipoproteins, HDL

- C-Reactive Protein

Grants and funding

- 81560636/Natural Science Foundation of China

- 81760702/Natural Science Foundation of China

- 2019YFC1712300/National Key R&D Program of China

- 20165BCB19009/Jiangxi Province 5511 innovative talent Project

- 2020YBBGWL002/Key R&D project of Jiangxi Province

- 20194AFD45001/Jiangxi Science and Technology Innovation Platform Project

- 20192ZDD02002/Special Project for Central Guidance of Local Science and Technology Development

- GJJ201257/Science and Technology Research Project of Education Department of Jiangxi Province

- 202110124/Science and Technology Project of Health Commission of Jiangxi Province

- 2020BSZR016/Doctoral Research Foundation of Jiangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 17 September 2013

Efficacy of anakinra in gouty arthritis: a retrospective study of 40 cases

- Sébastien Ottaviani 1 ,

- Anna Moltó 2 ,

- Hang-Korng Ea 2 ,

- Séverine Neveu 3 ,

- Ghislaine Gill 1 ,

- Lauren Brunier 1 ,

- Elisabeth Palazzo 1 ,

- Olivier Meyer 1 ,

- Pascal Richette 2 ,

- Thomas Bardin 2 ,

- Yannick Allanore 4 ,

- Frédéric Lioté 2 ,

- Maxime Dougados 3 &

- Philippe Dieudé 1

Arthritis Research & Therapy volume 15 , Article number: R123 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

7130 Accesses

16 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

Gout is a common arthritis that occurs particularly in patients who frequently have associated comorbidities that limit the use of conventional therapies. The main mechanism of crystal-induced inflammation is interleukin-1 production by activation of the inflammasome. We aimed to evaluate the efficacy and tolerance of anakinra in gouty patients.

We conducted a multicenter retrospective review of patients receiving anakinra for gouty arthritis. We reviewed the response to treatment, adverse events and relapses.

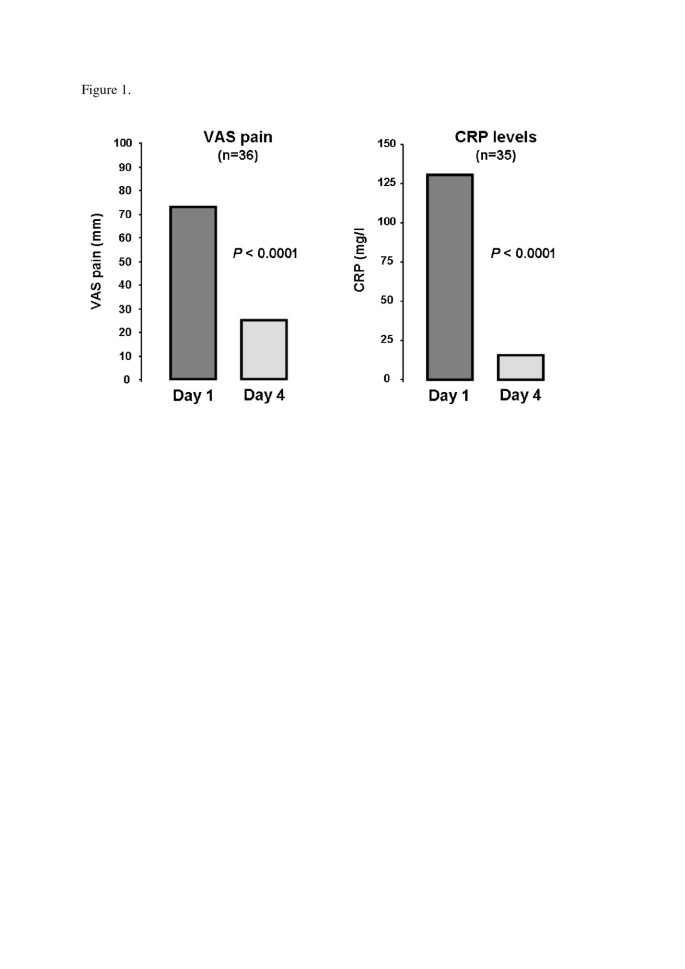

We examined data for 40 gouty patients (32 men; mean age 60.0 ± 13.9 years) receiving anakinra. Mean disease duration was 8.7 ± 8.7 years. All patients showed contraindications to and/or failure of at least two conventional therapies. Most (36; 90%) demonstrated good response to anakinra. Median pain on a 100-mm visual analog scale was rapidly decreased (73.5 (70.0 to 80.0) to 25.0 (20.0 to 32.5) mm, P <0.0001), as was median C-reactive protein (CRP) level (130.5 (55.8 to 238.8) to 16.0 (5.0 to 29.5) mg/l, P <0.0001). After a median follow-up of 7.0 (2.0 to 13.0) months, relapse occurred in 13 patients after a median delay of 15.0 (10.0 to 70.0) days. Seven infectious events, mainly with long-term use of anakinra, were noted.

Conclusions

Anakinra may be efficient in gouty arthritis, is relatively well tolerated with short-term use, and could be a relevant option in managing gouty arthritis when conventional therapies are ineffective or contraindicated. Its long-term use could be limited by infectious complications.

Gout is a common arthritis caused by deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals within and around joints secondary to chronic hyperuricemia. It affects 1% to 2% of adults in developed countries and may be increasing in prevalence [ 1 ]. Acute gouty arthritis may be associated with high inflammatory clinical and biological symptoms. Thus, one of the goals of management is rapid relief of inflammation [ 2 , 3 ].

Acute gouty attacks are usually treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), colchicine and corticosteroids [ 3 ]. Gouty patients often have concomitant renal, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal diseases as well as diabetes mellitus [ 4 ]. These comorbidities and associated treatments can lead to increased frequency of side effects or contraindications to conventional therapies for gouty arthritis [ 4 ]. We have abundant evidence of side effects from the use of colchicine (for example, for diarrhea) [ 5 ] and NSAIDs (for example, for gastrointestinal bleeding, cardiovascular events including myocardial infarction, renal impairment) [ 6 , 7 ], so care must be taken when prescribing such drugs. Thus, alternative therapies are needed for these 'difficult-to-treat' cases.

The main mechanism of crystal-induced inflammation is interleukin 1β (IL-1β) production by activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [ 8 ], which strengthens the relevance of targeting IL-1β in patients with crystal-induced arthritis. Anti-IL-1 agents, such as anakinra, have been evaluated in gouty arthritis, for treating acute attacks or for preventing gouty attacks while initiating urate-lowering therapy [ 9 – 14 ]. To date, only two small open studies have evaluated the efficacy of anakinra in acute gouty arthritis [ 13 , 14 ] although anakinra has been labeled for rheumatoid arthritis treatment for more than 10 years. Other IL-1 inhibitors, canakinumab and rilonacept, appear to be effective in reducing pain and signs of inflammation in randomized controlled trials, which validate IL-1 as playing a pivotal role in gout inflammation [ 9 , 10 , 12 , 15 ].

Here, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of anakinra in patients with acute and chronic gouty arthritis but with contraindications to or failure of conventional therapies.

This was a multicenter retrospective review of charts for patients who received anakinra for gouty arthritis. Patients were identified by treating rheumatologists and by searching available electronic medical records with the keyword 'anakinra' or 'Kineret ® '. Patients receiving anakinra who had concomitant connective tissue diseases were not included. Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of gouty arthritis defined as recommended by the identification of MSU crystals in synovial fluid [ 16 ] and at least one documented visit after the acute gouty arthritis requiring anakinra. The study was approved by the local institutional review board of Paris North Hospitals (No. 12-081) and all patients provided informed written consent to their physician to receive anakinra.

We retrospectively assessed response to anakinra at baseline and at the first documented visit following the acute gouty arthritis according to the following items: swollen joint count (SJC) and tender joint count (TJC), patient evaluation of pain by a visual analog scale (VAS pain, 0 to 100 mm) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (mg/L). We collected data on demographics (age, gender), clinical variables (tophus, localization of arthritis, comorbid conditions, and disease and flare duration), radiologic features of gouty arthropathy and biological variables (serum uric acid levels (SUA), CRP and creatinine). The outcome of anakinra treatment was classified as good, partial, or no response. A good response was arbitrarily defined as an improvement >50% in VAS pain or CRP level and/or documentation in the chart of the word 'good' response after anakinra treatment. A partial response was defined as a report of improvement in joint symptoms but not a 'good' response (20% to 50% improvement). No response was defined as the absence of symptom relief (<20% improvement).

Adverse events were defined as diarrhea, myopathy and skin reactions with colchicine treatment; gastrointestinal bleeding, cardiovascular events, renal impairment and skin reactions with NSAIDs; hyperglycemia, hypertension and cardiovascular events with steroids; and local skin reaction, infection and neutropenia with anakinra.

Contraindications to conventional therapies and comorbidities were as described [ 4 ], except for osteoporosis and hyperlipidemia, which we did not consider a comorbidity limiting prescription of conventional therapies.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range (IQR)) or number (%). Non-parametric or Fisher's exact test was used to compare quantitative or categorical data, respectively. A two-tailed P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Baseline characteristics

We investigated data for 40 patients (32 men) who received anakinra for gouty arthritis. Their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 . In all, 79% and 92% of patients showed clinical tophi and gouty arthropathy, respectively.

At baseline, the median (IQR) pain level was 73.5 (70.0 to 80.0) mm. The median TJC and SJC was 5.0 (3.5 to 8.0) and 4.0 (3.0 to 5.5), respectively. The median CRP level was 130.5 (55.8 to 238.8) mg/L. The mean SUA was 534 ± 172 μM. In all, 17 (43%) patients had received urate-lowering therapy (allopurinol ( n = 11), febuxostat ( n = 6), benzbromarone ( n = 1)). Diuretic drugs were prescribed for 14 patients (hydrochlorothiazides ( n = 3), loop diuretics ( n = 11)). All patients had a contraindication to or past history of adverse events with conventional treatments for acute gouty arthritis (Table 1 ).

The number of patients with gouty arthritis that was acute (<6 weeks), subacute (6 to 12 weeks) and chronic (>12 weeks) was 34, 2 and 4, respectively.

Among the 40 patients, 23 received anakinra following the protocol used by So et al .[ 14 ]: 100 mg daily for three days subcutaneously. Seven patients received anakinra for <15 days (100 mg/day: n = 6, 100 mg/2 days: n = 1). The 10 remaining patients received anakinra for the long term (>15 days), followed by a spacing of the dose regimen (median total duration: 5.0 (2.3 to 11.8) months).

Anakinra response for gouty arthritis

Whole population.

Of the 40 patients, good, partial and non-response to anakinra were noted in 36 (90%), 2 (5%) and 2 patients (5%), respectively. Pain score decreased from 73.5 (70.0 to 80.0) to 25.0 (20.0 to 32.5) mm, P <0.0001), as did CRP level (130.5 (55.8 to 238.8) to 16.0 (5.0 to 29.5) mg/L, P <0.0001) (Figure 1 ). In all, 30 patients received treatment to prevent relapse (Table 2 ). After a median follow-up of 7.0 (2.0 to 13.0) months, relapse occurred in 13 (32.5%) patients with a median delay of 15.0 (10.0 to 70.0) days. Relapse occurred particularly in patients not receiving therapy to prevent acute flare (7/10 versus 6/30, P = 0.006). No relapse occurred with long-term use of anakinra (>15 days).

Pain on a visual analog scale (VAS) and C-reactive protein level (CRP) on days 1 and 4 of anakinra treatment for gouty arthritis . VAS, visual analog scale (mm); CRP, C-reactive protein (mg/l).

Anakinra response according to the dose regimen

A total of 23 patients received anakinra, 100 mg/day, for up to three days, with good response in 20 (87%); 17 (74%) showed relapse prevention after resolution of the flare. After a median follow-up of 6.0 (1.5 to 14.0) months, relapse occurred in six (26%) patients at a median delay of 15.0 (6.0 to 26.3) days.

In all, 17 patients received anakinra for more than three days, with good response in 16 (94%); 13 (76%) showed relapse prevention after flare resolution. After a median follow-up of 8.0 (3.0 to 13.0) months, relapse occurred in seven (41%) patients at a median delay of 60.0 (12.5 to 125.0) days.

No patient reported anakinra-related skin hypersensitivity. A total of seven infectious complications, mainly staphylococcal infections, were reported in six patients (Table 2 ). One H1N1 viral infection occurred one day after anakinra was started (previously reported in [ 17 ]). All other infectious complications occurred in patients with long-term use of anakinra and were successfully treated with antibiotics. Of the six patients, five restarted anakinra after the resolution of infection. No patient has shown tuberculosis or pneumococcal infection.

Recently, the emerging role of IL-1β in the pathogenesis of inflammation in crystal-induced arthritis [ 8 , 18 , 19 ] led to considering anti-IL-1 therapies as a relevant alternative to conventional therapies for gouty arthritis. Here, we report on our experience with anakinra therapy, a recombinant receptor antagonist against IL-R blocking both IL-1β and β, for gouty arthritis in a large series of patients. Our results are in good agreement with those of the first open-label trial of anakinra showing improved patient-reported symptoms by at least 50% of all 10 patients enrolled [ 14 ]. Chen et al . suggested an efficiency in 6 of 10 patients with good response [ 13 ]. Similar to So et al ., we observed a rapid decrease of both VAS pain and CRP levels. Recently, randomized controlled trials found that two anti-IL-1β biologic agents (rilonacept and canakinumab) prevented gouty arthritis during the initiation of urate-lowering therapy with allopurinol [ 10 , 11 ], but only canakinumab demonstrated efficacy for acute gouty arthritis [ 9 , 12 ]. In these cases, rilonacept failed to induce a rapid relief of symptoms [ 20 ] but could decrease pain in chronic gouty arthritis [ 15 ]. These data strengthen the argument to target IL-1 blockade for acute gouty arthritis. Of interest, canakinumab recently obtained European authorization [ 21 ].