Brown Vs. the Board of Education

How it works

The case of Brown versus the Board of Education was one of the biggest turning points in African American history, as it was the match that lit the fire under the Civil Rights Movement. The case was the start of a dramatic change, not only for African Americans, but for the rest of the world. This case had a large impact on many other similar cases as well. In the 1950’s public facilities, buildings, events, even water fountains, were segregated. There were “black” school were only colored kids went.

Then there were “white only” schools, often close to the neighborhoods and communities where children of color stayed. Many African American children had to walk far distances to get to school. It reached a point where their parents worried about their children’s safety getting to school. The parents had enough and finally decided to speak up. A man named Oliver Leon Brown brought the topic of segregated schools to court after his daughter, Linda Brown was denied entry into an all white school. After years the case closed finally, in the favor of Mr. Brown, his daughter Linda, and the other African American children. The supreme court made the decision that it’s not fair that the black and white children were segregated in different schools. This case still affects society and the education system today. Brown v. Board of Education was the reason that blacks and whites no longer have separate restrooms and water fountains, this was the case that truly destroyed the saying separate but equal, Brown vs. Board of education truly made everyone equal.

The case started in Topeka, Kansas. Oliver Brown’s daughter, a third-grader named Linda Brown was one of many children having to travel long distance to get to her segregated school. She had to walk over a mile through a railroad switchyard to get to her “blacks only” elementary school. There was a white elementary school only seven blocks away from their home, but when Oliver Brown attempted to enroll his daughter into the school, the principal denied his request, simply due to the fact that Linda was not white. Brown went to the head of Topeka’s branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and asked for help. The NAACP were eager to help the Browns. In fact they had been wanting to challenge segregation in public schools for a while, and this was their chance. The NAACP was excited to start on a case like this because they wanted to expose what had really been going on in a ‘separate but equal society’. When this case was taken to the state level, it was unfortunately lost. The final ruling stated that separation by color was not violating any law or amendment. In fact the state was not only allowing the separation, but also implying that segregation in schools was necessary because it would prepare young African Americans for what was to come in the real world. During this time all of society was segregated, due to Jim Crow laws, Jim Crow laws were a collection of laws in the US that varied from state to state.

These laws legalized racial segregation. For example, African Americans weren’t allowed to eat in the same restaurants, drink from the same water fountains, or even ride in the same car train as white people. After losing the state case, Brown and the NAACP decided to continue to pursue the case. Mr. Brown and the NAACP went to the United-States Supreme Court. In October, 1951, they appealed to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court , first heard from the lawyers December 9, 1952. Both sides argued their points. Brown’s lawyers argued that there shouldn’t be a segregation in the education system unless there was proof that black children were different from anyone else. The Board Of Education’s lawyers argued that many people including some blacks scholars, did not see a problem in attending an all black school. The arguments went on for three days. The supreme court talked the case over for three months. A year after the first arguments were heard, the case was reexamined. Three years passed until the court made their final decision on the case. Finally on May 17, 1954 the Supreme Court ruled, “separate schools for blacks and whites were unconstitutional. The court ordered all schools desegregated with “all deliberate speed.”” The final ruling of this case was monumental for African American history and the beginning of desegregation in society.

After the final ruling of the case in the favor of Linda Brown a lot of changes were supposed to be made. However, the changes that the Supreme Court court had demanded were not happening overnight, “ For a decade or more, little progress was made.. The first generation of desegregation plans for the late 1950s and early 1960s typically moved just a handful of black students into the white schools or allowed for voluntary transfers to different schools, producing only small read ductions and segregation” Many counties and states refused to go along with it. During the following years after the results of the trial the black population had to fight harder for their civil rights. After this one victory came many more trials. A number of school districts in the Southern and border states desegregated peacefully. In other places their was intense amounts of white resistance to school desegregation which resulted in open defiance and violent confrontations. Requiring the use of federal troops for example, Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. Elizabeth Eckford was a part of the little rock nine. She was integrating into white Central High School while surrounding her was, “an angry mob.. scores of adults and young whites were cruising in taunting her.. at times the mob uncontrollably surged forward, threatening Elizabeth’s life”. Efforts to end segregation in schools were connected with the refusal of welcoming African Americans into previously all-white schools. However, after all the intense hardships, the changes were slowly made. Brown v. Board of Education changed the nation, it changed history. The case changed the nature of race relations in America. By 1964, the NAACP’s focused legal campaign had been transformed into a mass movement to eliminate all traces of segregation and racism from the American life. This goal was built by struggle and sacrifice, Overtimes it captured the help and sympathy of the nation. Brown v. Board had inspired the dream of a society based on justice and racial equality. It had debunked the idea of ‘separate but equal’.

Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court decision that declared it unconstitutional to have separate public schools for black and white students, paving the way for integration. But how relevant is the framing of Brown v. Board to the current social, cultural and educational challenges today? The rulings of this case are reflected in the education system today, “ children of all races are allowed to attend public school together.. Academic achievement of African American children has dramatically increased since the ruling took place.” Even though this was an obvious effect of the case ruling, it is huge. The idea that at one point in history students were forced to go to a certain school based on skin color is crazy. However, Brown vs. Board also affects us socially and culturally today, “by focusing the nation’s attention on subjugation of blacks, it helped fuel a wave of freedom rides, sit-ins, voter registration efforts, and other actions leading ultimately to civil rights legislation in the late 1950s and 1960s.” The Supreme Court decision led to desegregation in schools, leading to desegregation throughout society. This led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Without the Supreme Court Ruling of Brown vs. The Board of Education, the lives of all Americans would be completely different.

The case of Brown versus the Board of Education is historically known as one of the biggest turning points for the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. This Supreme Court ruling led to more than the desegregation of schools, it led to desegregation in society. Schools could not be segregated by color or race. This provided the people of color access to quality education that had not been available to them before. This allowed many people of color to move into careers never thought possible due to the education required. The contact between children of different races was a significant push in reducing racial discrimination. White children with colored friends, which would have never been thought of before. Without it, society would be completely different today.

Works Cited

- Clark, K. B., Chein, I., & Cook, S. W. (2004). The Effects of Segregation and the Consequences of Desegregation A (September 1952) Social Science Statement in the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Supreme Court Case. American Psychologist, 59(6), 495-501.

- Norton, W. (2019). Shibboleth Authentication Request. [online] Ezproxy.bellevuecollege.edu. Available at: https://ezproxy.bellevuecollege.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.bellevuecollege.edu/docview/262861122?accountid=35840 [Accessed 20 Mar. 2019].

- Orley Ashenfelter, William J. Collins, Albert Yoon; Evaluating the Role of Brown v. Board of Education in School Equalization, Desegregation, and the Income of African Americans, American Law and Economics Review, Volume 8, Issue 2, 1 July 2006, Pages 213–248, https://doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahl001

- Reber, Sarah J. “Court-Ordered Desegregation: Successes and Failures Integrating American Schools since Brown versus Board of Education.” The Journal of Human Resources 40, no. 3 (2005): 559-90. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.bellevuecollege.edu/stable/4129552.

- Anonymous. “Fifty Years Ago: The Little Rock Nine Integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 57 (October 1, 2007): 5. http://search.proquest.com/docview/195549439/.

Cite this page

Brown Vs. The Board of Education. (2021, Mar 20). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/brown-vs-the-board-of-education/

"Brown Vs. The Board of Education." PapersOwl.com , 20 Mar 2021, https://papersowl.com/examples/brown-vs-the-board-of-education/

PapersOwl.com. (2021). Brown Vs. The Board of Education . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/brown-vs-the-board-of-education/ [Accessed: 25 Apr. 2024]

"Brown Vs. The Board of Education." PapersOwl.com, Mar 20, 2021. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/brown-vs-the-board-of-education/

"Brown Vs. The Board of Education," PapersOwl.com , 20-Mar-2021. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/brown-vs-the-board-of-education/. [Accessed: 25-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2021). Brown Vs. The Board of Education . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/brown-vs-the-board-of-education/ [Accessed: 25-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Brown v. Board of Education

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 27, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was a landmark 1954 Supreme Court case in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. Brown v. Board of Education was one of the cornerstones of the civil rights movement, and helped establish the precedent that “separate-but-equal” education and other services were not, in fact, equal at all.

Separate But Equal Doctrine

In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racially segregated public facilities were legal, so long as the facilities for Black people and whites were equal.

The ruling constitutionally sanctioned laws barring African Americans from sharing the same buses, schools and other public facilities as whites—known as “Jim Crow” laws —and established the “separate but equal” doctrine that would stand for the next six decades.

But by the early 1950s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ) was working hard to challenge segregation laws in public schools, and had filed lawsuits on behalf of plaintiffs in states such as South Carolina, Virginia and Delaware.

In the case that would become most famous, a plaintiff named Oliver Brown filed a class-action suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in 1951, after his daughter, Linda Brown , was denied entrance to Topeka’s all-white elementary schools.

In his lawsuit, Brown claimed that schools for Black children were not equal to the white schools, and that segregation violated the so-called “equal protection clause” of the 14th Amendment , which holds that no state can “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The case went before the U.S. District Court in Kansas, which agreed that public school segregation had a “detrimental effect upon the colored children” and contributed to “a sense of inferiority,” but still upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Brown v. Board of Education Verdict

When Brown’s case and four other cases related to school segregation first came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court combined them into a single case under the name Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka .

Thurgood Marshall , the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, served as chief attorney for the plaintiffs. (Thirteen years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson would appoint Marshall as the first Black Supreme Court justice.)

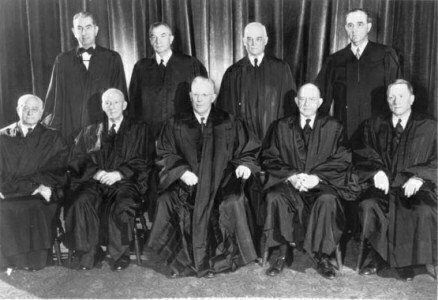

At first, the justices were divided on how to rule on school segregation, with Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson holding the opinion that the Plessy verdict should stand. But in September 1953, before Brown v. Board of Education was to be heard, Vinson died, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower replaced him with Earl Warren , then governor of California .

Displaying considerable political skill and determination, the new chief justice succeeded in engineering a unanimous verdict against school segregation the following year.

In the decision, issued on May 17, 1954, Warren wrote that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” as segregated schools are “inherently unequal.” As a result, the Court ruled that the plaintiffs were being “deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.”

Little Rock Nine

In its verdict, the Supreme Court did not specify how exactly schools should be integrated, but asked for further arguments about it.

In May 1955, the Court issued a second opinion in the case (known as Brown v. Board of Education II ), which remanded future desegregation cases to lower federal courts and directed district courts and school boards to proceed with desegregation “with all deliberate speed.”

Though well intentioned, the Court’s actions effectively opened the door to local judicial and political evasion of desegregation. While Kansas and some other states acted in accordance with the verdict, many school and local officials in the South defied it.

In one major example, Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas called out the state National Guard to prevent Black students from attending high school in Little Rock in 1957. After a tense standoff, President Eisenhower deployed federal troops, and nine students—known as the “ Little Rock Nine ”— were able to enter Central High School under armed guard.

Impact of Brown v. Board of Education

Though the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board didn’t achieve school desegregation on its own, the ruling (and the steadfast resistance to it across the South) fueled the nascent civil rights movement in the United States.

In 1955, a year after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. Her arrest sparked the Montgomery bus boycott and would lead to other boycotts, sit-ins and demonstrations (many of them led by Martin Luther King Jr .), in a movement that would eventually lead to the toppling of Jim Crow laws across the South.

Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , backed by enforcement by the Justice Department, began the process of desegregation in earnest. This landmark piece of civil rights legislation was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 .

Runyon v. McCrary Extends Policy to Private Schools

In 1976, the Supreme Court issued another landmark decision in Runyon v. McCrary , ruling that even private, nonsectarian schools that denied admission to students on the basis of race violated federal civil rights laws.

By overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine, the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education had set the legal precedent that would be used to overturn laws enforcing segregation in other public facilities. But despite its undoubted impact, the historic verdict fell short of achieving its primary mission of integrating the nation’s public schools.

Today, more than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education , the debate continues over how to combat racial inequalities in the nation’s school system, largely based on residential patterns and differences in resources between schools in wealthier and economically disadvantaged districts across the country.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

History – Brown v. Board of Education Re-enactment, United States Courts . Brown v. Board of Education, The Civil Rights Movement: Volume I (Salem Press). Cass Sunstein, “Did Brown Matter?” The New Yorker , May 3, 2004. Brown v. Board of Education, PBS.org . Richard Rothstein, Brown v. Board at 60, Economic Policy Institute , April 17, 2014.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- Introduction to the Civil Rights Movement

- African American veterans and the Civil Rights Movement

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- Emmett Till

- The Montgomery Bus Boycott

- "Massive Resistance" and the Little Rock Nine

- The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- SNCC and CORE

- Black Power

- The Civil Rights Movement

- In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) a unanimous Supreme Court declared that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

- The Court declared “separate” educational facilities “inherently unequal.”

- The case electrified the nation, and remains a landmark in legal history and a milestone in civil rights history.

A segregated society

The brown v. board of education case, thurgood marshall, the naacp, and the supreme court, separate is "inherently unequal", brown ii: desegregating with "all deliberate speed”, what do you think.

- James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 387.

- James T. Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 25-27.

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 387.

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 32.

- See Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, and Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality (New York: Knopf, 2004).

- Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education, 43-45.

- Supreme Court of the United States, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

- Patterson, Grand Expectations, 394-395.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Brown v. Board of Education: Annotated

The 1954 Supreme Court decision, based on the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, declared that “separate but equal” has no place in education.

The US Supreme Court’s decision in the case known colloquially as Brown v. Board of Education found that the “[t]he ‘separate but equal ’ doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537, has no place in the field of public education.” The Plessy case, decided in 1896, had found that the segregation laws which created “separate but equal” accommodations for Black Americans, specific to transportation but applicable generally, were not a violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. Segregation in education had been challenged throughout the first half of the twentieth century, and rulings in a number coalesced to propel Brown to the level of the Supreme Court to address segregation in all public schools.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Below is an annotation of the opinion, with relevant scholarship covering the legal, social and education history leading up to and after the decision. As always, the supporting research is free to read and download.

The red J indicates free access to the linked research on JSTOR . ____________________________________________________________________________

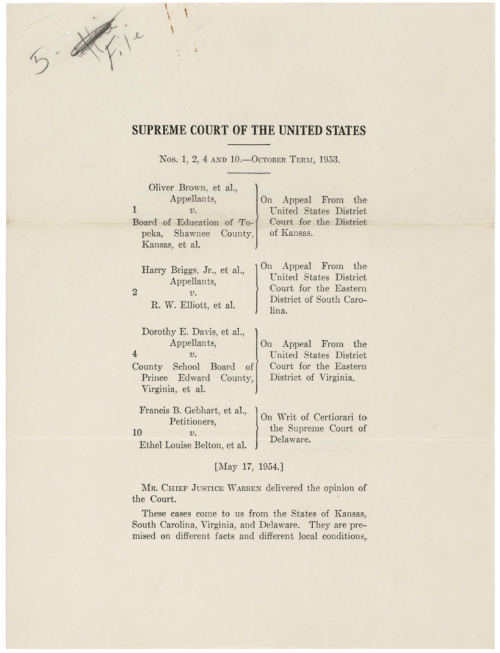

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954) (USSC+)

Argued December 9, 1952

Reargued December 8, 1953

Decided May 17, 1954

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS*

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment —even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors of white and Negro schools may be equal.

(a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education.

(b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation.

(c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

(d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities , even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal.

(e) The “separate but equal” doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537, has no place in the field of public education.

(f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees.

MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are premised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion.

In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each instance, they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a three-judge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the so-called “separate but equal” doctrine announced by this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537 . Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. In the Delaware case , the Supreme Court of Delaware adhered to that doctrine, but ordered that the plaintiffs be admitted to the white schools because of their superiority to the Negro schools.

The plaintiffs contend that segregated public schools are not “equal” and cannot be made “equal,” and that hence they are deprived of the equal protection of the laws. Because of the obvious importance of the question presented, the Court took jurisdiction. Argument was heard in the 1952 Term, and reargument was heard this Term on certain questions propounded by the Court.

Reargument was largely devoted to the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It covered exhaustively consideration of the Amendment in Congress, ratification by the states, then-existing practices in racial segregation, and the views of proponents and opponents of the Amendment. This discussion and our own investigation convince us that, although these sources cast some light, it is not enough to resolve the problem with which we are faced. At best, they are inconclusive. The most avid proponents of the post-War Amendments undoubtedly intended them to remove all legal distinctions among “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.” Their opponents, just as certainly, were antagonistic to both the letter and the spirit of the Amendments and wished them to have the most limited effect. What others in Congress and the state legislatures had in mind cannot be determined with any degree of certainty.

An additional reason for the inconclusive nature of the Amendment’s history with respect to segregated schools is the status of public education at that time. In the South, the movement toward free common schools, supported by general taxation, had not yet taken hold . Education of white children was largely in the hands of private groups. Education of Negroes was almost nonexistent, and practically all of the race were illiterate. In fact, any education of Negroes was forbidden by law in some states. Today, in contrast, many Negroes have achieved outstanding success in the arts and sciences, as well as in the business and professional world. It is true that public school education at the time of the Amendment had advanced further in the North, but the effect of the Amendment on Northern States was generally ignored in the congressional debates. Even in the North, the conditions of public education did not approximate those existing today. The curriculum was usually rudimentary; ungraded schools were common in rural areas; the school term was but three months a year in many states, and compulsory school attendance was virtually unknown. As a consequence, it is not surprising that there should be so little in the history of the Fourteenth Amendment relating to its intended effect on public education.

In the first cases in this Court construing the Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all state-imposed discriminations against the Negro race. The doctrine of “separate but equal” did not make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson , supra, involving not education but transportation. American courts have since labored with the doctrine for over half a century. In this Court, there have been six cases involving the “separate but equal” doctrine in the field of public education. In Cumming v. County Board of Education , 175 US 528 , and Gong Lum v. Rice , 275 US 78 , the validity of the doctrine itself was not challenged. In more recent cases, all on the graduate school level, inequality was found in that specific benefits enjoyed by white students were denied to Negro students of the same educational qualifications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada , 305 US 337 ; Sipuel v. Oklahoma , 332 US 631; Sweatt v. Painter , 339 US 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , 339 US 637 . In none of these cases was it necessary to reexamine the doctrine to grant relief to the Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v. Painter , supra, the Court expressly reserved decision on the question whether Plessy v. Ferguson should be held inapplicable to public education.

In the instant cases, that question is directly presented. Here, unlike Sweatt v. Painter , there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other “tangible” factors. Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education.

In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868, when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896, when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.

Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship . Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race , even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.

In Sweatt v. Painter , supra, in finding that a segregated law school for Negroes could not provide them equal educational opportunities, this Court relied in large part on “those qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness in a law school.” In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , supra, the Court, in requiring that a Negro admitted to a white graduate school be treated like all other students, again resorted to intangible considerations: “…his ability to study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with other students, and, in general, to learn his profession.” Such considerations apply with added force to children in grade and high schools. To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs:

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law , for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system .

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson , this finding is amply supported by modern authority. Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this finding is rejected.

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal . Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Because these are class actions, because of the wide applicability of this decision, and because of the great variety of local conditions, the formulation of decrees in these cases presents problems of considerable complexity . On reargument, the consideration of appropriate relief was necessarily subordinated to the primary question—the constitutionality of segregation in public education. We have now announced that such segregation is a denial of the equal protection of the laws. In order that we may have the full assistance of the parties in formulating decrees, the cases will be restored to the docket, and the parties are requested to present further argument on Questions 4 and 5 previously propounded by the Court for the reargument this Term The Attorney General of the United States is again invited to participate. The Attorneys General of the states requiring or permitting segregation in public education will also be permitted to appear as amici curiae upon request to do so by September 15, 1954, and submission of briefs by October 1, 1954.

It is so ordered.

* Together with No. 2, Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, argued December 9–10, 1952, reargued December 7–8, 1953; No. 4, Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, argued December 10, 1952, reargued December 7–8, 1953, and No. 10, Gebhart et al. v. Belton et al. , on certiorari to the Supreme Court of Delaware, argued December 11, 1952, reargued December 9, 1953.

[Transcript available from the National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/brown-v-board-of-education ]

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

Remembering Sun Yat Sen Abroad

Taking Slavery West in the 1850s

Webster’s Dictionary 1828: Annotated

Life in the Islands of the Dead

Recent posts.

- Sheet Music: the Original Problematic Pop?

- Ostrich Bubbles

- Smells, Sounds, and the WNBA

- A Bodhisattva for Japanese Women

- Asking Scholarly Questions with JSTOR Daily

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Milestone Documents

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

Citation: Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , Opinion; May 17, 1954; Records of the Supreme Court of the United States; Record Group 267; National Archives.

View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog

View Transcript

In this milestone decision, the Supreme Court ruled that separating children in public schools on the basis of race was unconstitutional. It signaled the end of legalized racial segregation in the schools of the United States, overruling the "separate but equal" principle set forth in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case.

On May 17, 1954, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas . State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" precedent set by the Supreme Court nearly 60 years earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement during the decade of the 1950s.

Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine just how the ruling would be imposed. Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II , instructing the states to begin desegregation plans "with all deliberate speed."

Despite two unanimous decisions and careful, if vague, wording, there was considerable resistance to the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education . In addition to the obvious disapproving segregationists were some constitutional scholars who felt that the decision went against legal tradition by relying heavily on data supplied by social scientists rather than precedent or established law. Supporters of judicial restraint believed the Court had overstepped its constitutional powers by essentially writing new law.

However, minority groups and members of the civil rights movement were buoyed by the Brown decision even without specific directions for implementation. Proponents of judicial activism believed the Supreme Court had appropriately used its position to adapt the basis of the Constitution to address new problems in new times. The Warren Court stayed this course for the next 15 years, deciding cases that significantly affected not only race relations, but also the administration of criminal justice, the operation of the political process, and the separation of church and state.

Teach with this document.

Previous Document Next Document

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (USSC+)

Argued December 9, 1952

Reargued December 8, 1953

Decided May 17, 1954

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS*

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment -- even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors of white and Negro schools may be equal.

(a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education.

(b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation.

(c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

(d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal.

(e) The "separate but equal" doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 U.S. 537, has no place in the field of public education.

(f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees.

MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court. These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are premised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion.

In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each instance, they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a three-judge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the so-called "separate but equal" doctrine announced by this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537. Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. In the Delaware case, the Supreme Court of Delaware adhered to that doctrine, but ordered that the plaintiffs be admitted to the white schools because of their superiority to the Negro schools.

The plaintiffs contend that segregated public schools are not "equal" and cannot be made "equal," and that hence they are deprived of the equal protection of the laws. Because of the obvious importance of the question presented, the Court took jurisdiction. Argument was heard in the 1952 Term, and reargument was heard this Term on certain questions propounded by the Court.

Reargument was largely devoted to the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It covered exhaustively consideration of the Amendment in Congress, ratification by the states, then-existing practices in racial segregation, and the views of proponents and opponents of the Amendment. This discussion and our own investigation convince us that, although these sources cast some light, it is not enough to resolve the problem with which we are faced. At best, they are inconclusive. The most avid proponents of the post-War Amendments undoubtedly intended them to remove all legal distinctions among "all persons born or naturalized in the United States." Their opponents, just as certainly, were antagonistic to both the letter and the spirit of the Amendments and wished them to have the most limited effect. What others in Congress and the state legislatures had in mind cannot be determined with any degree of certainty.

An additional reason for the inconclusive nature of the Amendment's history with respect to segregated schools is the status of public education at that time. In the South, the movement toward free common schools, supported by general taxation, had not yet taken hold. Education of white children was largely in the hands of private groups. Education of Negroes was almost nonexistent, and practically all of the race were illiterate. In fact, any education of Negroes was forbidden by law in some states. Today, in contrast, many Negroes have achieved outstanding success in the arts and sciences, as well as in the business and professional world. It is true that public school education at the time of the Amendment had advanced further in the North, but the effect of the Amendment on Northern States was generally ignored in the congressional debates. Even in the North, the conditions of public education did not approximate those existing today. The curriculum was usually rudimentary; ungraded schools were common in rural areas; the school term was but three months a year in many states, and compulsory school attendance was virtually unknown. As a consequence, it is not surprising that there should be so little in the history of the Fourteenth Amendment relating to its intended effect on public education.

In the first cases in this Court construing the Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all state-imposed discriminations against the Negro race. The doctrine of "separate but equal" did not make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson , supra, involving not education but transportation. American courts have since labored with the doctrine for over half a century. In this Court, there have been six cases involving the "separate but equal" doctrine in the field of public education. In Cumming v. County Board of Education , 175 U.S. 528, and Gong Lum v. Rice , 275 U.S. 78, the validity of the doctrine itself was not challenged. In more recent cases, all on the graduate school level, inequality was found in that specific benefits enjoyed by white students were denied to Negro students of the same educational qualifications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada , 305 U.S. 337; Sipuel v. Oklahoma , 332 U.S. 631; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , 339 U.S. 637. In none of these cases was it necessary to reexamine the doctrine to grant relief to the Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v. Painter , supra, the Court expressly reserved decision on the question whether Plessy v. Ferguson should be held inapplicable to public education.

In the instant cases, that question is directly presented. Here, unlike Sweatt v. Painter , there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other "tangible" factors. Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education.

In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868, when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896, when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.

Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.

In Sweatt v. Painter , supra, in finding that a segregated law school for Negroes could not provide them equal educational opportunities, this Court relied in large part on "those qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness in a law school." In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , supra, the Court, in requiring that a Negro admitted to a white graduate school be treated like all other students, again resorted to intangible considerations: ". . . his ability to study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with other students, and, in general, to learn his profession." Such considerations apply with added force to children in grade and high schools. To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs:

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system.

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson , this finding is amply supported by modern authority. Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this finding is rejected.

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Because these are class actions, because of the wide applicability of this decision, and because of the great variety of local conditions, the formulation of decrees in these cases presents problems of considerable complexity. On reargument, the consideration of appropriate relief was necessarily subordinated to the primary question -- the constitutionality of segregation in public education. We have now announced that such segregation is a denial of the equal protection of the laws. In order that we may have the full assistance of the parties in formulating decrees, the cases will be restored to the docket, and the parties are requested to present further argument on Questions 4 and 5 previously propounded by the Court for the reargument this Term The Attorney General of the United States is again invited to participate. The Attorneys General of the states requiring or permitting segregation in public education will also be permitted to appear as amici curiae upon request to do so by September 15, 1954, and submission of briefs by October 1, 1954.

It is so ordered.

* Together with No. 2, Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, argued December 9-10, 1952, reargued December 7-8, 1953; No. 4, Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, argued December 10, 1952, reargued December 7-8, 1953, and No. 10, Gebhart et al. v. Belton et al. , on certiorari to the Supreme Court of Delaware, argued December 11, 1952, reargued December 9, 1953.

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, brown v. board: when the supreme court ruled against segregation.

May 17, 2023 | by NCC Staff

The decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka on May 17, 1954 is perhaps the most famous of all Supreme Court cases, as it started the process ending segregation. It overturned the equally far-reaching decision of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896.

In the Plessy case, the Supreme Court decided by a 7-1 margin that “separate but equal” public facilities could be provided to different racial groups. In his majority opinion, Justice Henry Billings Brown pointed to schools as an example of the legality of segregation. “The most common instance of this is connected with the establishment of separate schools for white and colored children, which has been held to be a valid exercise of the legislative power even by courts of States where the political rights of the colored race have been longest and most earnestly enforced,” he said.

The lone dissenter, Justice John Marshall Harlan, wrote, “In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case” (referencing the controversial 1857 decision about slavery and the citizenship of Blacks).

“Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens,” he added.

The Plessy decision institutionalized Jim Crow laws that allowed racial segregation to continue for decades. By 1951, the issue was heading back to the Court for review, and the outlook didn’t look promising for the forces that had united to overturn the Plessy decision. The NAACP and its attorney, Thurgood Marshall, had been litigating segregation in court for years and had won some significant victories.

The Brown case was actually a combination of five cases involving segregation at public schools in Kansas, Delaware, Virginia, South Carolina, and the District of Columbia. Oliver Brown, the father of lead plaintiff Linda Brown, sued on her behalf after Linda was refused admission to an all-white secondary public school in Topeka, Kansas.

The justices who first heard the case in 1953 were divided.

Chief Justice Fred Vinson, from Kentucky, wasn’t convinced that Plessy should be overturned on constitutional grounds. Several other justices were undecided and possibly leaning toward upholding Plessy. Four justices seemed to be committed to overturning Plessy , but five votes were needed, and there were concerns about a divided court.

Another concern was about how the Brown decision if it overturned segregation, could be enforced in 19 states and the District of Columbia without widespread violence.

The court decided in June 1953 to hear additional arguments in the case later in the year. But in September 1953, Chief Justice Vinson died suddenly from a heart attack. President Dwight Eisenhower had promised the next Supreme Court opening to the politically powerful Earl Warren, the former Governor of California.

Warren was appointed Chief Justice and the court met in a private session in December to discuss the Brown case. Two justices took notes of the meeting, which indicate that Warren made a powerful opening statement that made it clear the Court was heading toward the end of segregation.

Warren talked about the abilities of Marshall and the legal team from the NAACP.

“I don’t see how we can continue in this day and age to set one group apart from the rest and say that they are not entitled to exactly the same treatment as all others,” Warren said. “At present, my instincts and tentative feelings would lead me to say that in these cases we should abolish, in a tolerant way, the practice of segregation in public schools,” he said.

Warren also made it clear he would work with the justices to find “unanimity and uniformity, even if we have some differences.”

Two justices—Robert Jackson and Stanley Reed—had concerns about the Supreme Court making a decision that would be better left to Congress. There were also questions about Marshall’s arguments, which referred much to the sociological evidence about the damage caused by segregation (and not as much to prior case law).

On May 17, 1954, Warren read the final decision: The Supreme Court was unanimous in its decision that segregation must end. In its next session, it would tackle the issue of how that would happen.

“We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” Warren said.

The announcement made international headlines and more than a few newspapers saw the decision as vindication for Justice Harlan’s dissent in the 1896 Plessy case.

Not long after the Brown decision, in October 1954, Justice Robert Jackson died and President Eisenhower picked his replacement from the Second Circuit Court: Judge John Marshall Harlan, the grandson and namesake of the famous dissenter.

More from the National Constitution Center

Constitution 101

Explore our new 15-unit core curriculum with educational videos, primary texts, and more.

Search and browse videos, podcasts, and blog posts on constitutional topics.

Founders’ Library

Discover primary texts and historical documents that span American history and have shaped the American constitutional tradition.

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Brown vs. Board of Education Research Paper

Introduction, analysis and discussion, reference list.

The 20 th century saw the American education system faced with the issue of segregation, resulting in many students being denied the chance to attend schools of their choice on the basis of their race. During this time, schools adopted structured curricula that were not student-centered.

With time, however, the American education system underwent a major transformation process. Today, the American educational curricula are not only student-centered, but also inclusive. In addition, different policies have also been passed in support of an inclusive education system. The passing of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) 2001 is also part of the educational reforms that were envisaged in the American education system. The policy was part of educational initiatives aimed at promoting education in the United States.

The campaign has given all students equal educational opportunities regardless of their socio-cultural, economic, or racial backgrounds. However, high cost of education and income discrepancies among the Americans of diverse socio-economic backgrounds have been the major setbacks in ensuring that education for all is realized. The current research paper examines the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas case as a major turning point for the education system in the U.S.

The objective of the research paper is to develop a vision of education for the future based on past educational theories, trends and practices. The premise of the study is that school and educational systems have been undergoing progressive transformation.

The decision made by the Supreme Court as regard the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas case is of importance to the American educational system. In addition, it also challenged the Plessy v. Ferguson , bringing to end segregation in the school system (Miller, 2004).

Previously, separate schools were set for Whites and Blacks (Cozzens, 1998). To encourage equality in school facilities (libraries and offices) and equal pay, civil rights activists and other human rights groups in America fought endlessly for change. In other words, the struggle for education for all started a long time ago and was part of civil rights movement in the U.S.

In the case Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas , the Supreme Court ruled that segregation in public schools posed a detrimental effect on colored students (Miller, 2004). In addition, Black students were denied an equal chance to benefit from the same educational system as their White counterparts. Consequently, Black students developed an inferiority complex, thereby affecting their learning capabilities (Cozzen, 1998).

The ruling further stated that segregation in schools had the capacity to retard the mental and educational development of Black students (Miller, 2004). This is because it was thought to deprive the students some of major benefits enjoyed in racially integrated schools. As such, there was need to implement an integrated school system. Following this ruling, students from minority races could now be admitted to public schools hitherto regarded as a preserve for the Whites.

Many people credited and applauded the ruling of the Supreme Court on the Brown case for the change it brought to the education system. Others saw the decision as a turning point for the schools admission system (Miller, 2004). For instance, minority students who had been denied places on White public schools could easily get admitted.

In addition, the Supreme Court ruling made the Plessy v. Ferguson interpretation and ruling invalid. The case allowed for the protection of Minorities as required in the Fourteenth Amendment on Equal Protection Clause. This meant that Black students could be admitted in schools which were previously the preserve of White students.

The ruling by the Supreme Court on this case was a major milestone in the U.S. education systems as schools became disintegrated allowing students of mixed races to attend same learning institutions. However, despite the recommendation to integrate minority students with white students, there still lacked a framework which specified an implementation plan for the proposed changes (Cozzens, 1998). However, this was a historical step towards full disintegration of public schools (Cozzens, 1998).

Drawing from the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas case, it is important to note that full disintegration of public schools was a progressive act in the education system. According to Kremer (2005), progressive education was initiated in the 20 th century as part of educational reforms in public schools.

Furthermore, it was a philosophy that focused on how students should be taught in schools. It was “a response to the traditional way of teaching kids, which was very structured, dry, and authoritarian” (Kremer, 2004, p.32-33). As a result, progressive education focused on the adoption of humanistic values and democratic behaviors, as opposed to the traditional authoritative strategy.

Progressivism as an educational theory is based on the premise that schools should be child centered. The progressive model of education has been described as “new education” which advocates for the combination of education and actual experience (Kumar, 2004). The underlying philosophy in progressive model of education has been to change how schools teach students.

The education system has undergone tremendous transformation through the adoption of the progressivism philosophy as progressive educators have helped students reach conscientization. According to Kumar (2004), conscientization involves the breaking of prevailing mythologies in education to create new degrees of awareness, especially awareness of oppression. In other words, the progressive model focuses on continuity in the education system.

Just like in the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas case ruling, progressivism called for constant change in school system rather than being static. Currently, the education system has adopted the K-12 education system in public schools which encourages compulsory education for all. Moreover, there is an emerging trend in the schools system in regard to how students learn and how schools teach (Wilen-Daugenti & McKee, 2008).

For example, compared to the 20 th century, the current education process has now evolved into collaborative learning. Different stakeholders have come on board to transform the education system through research and students placements. The emerging trends are a sign that segregation in school system has continued to decline even as the number of minorities continues to increase (Stevenson, 2010).

The U.S education system requires visionary leaders who can implement policies which allow for continuity in the system. My vision of the purpose and structure of schools in the future entails embracing a progressive model which is student-centered. In other words, schools should adopt a curriculum which embraces both education and actual experience.

Although the current K-12 education system faces some challenges, the incorporation of NCLB has led to improvement in the education system. Nonetheless, a visionary curriculum which embraces the global changes to make our students excel academically, gain the necessary skills and knowledge which would make them competitive at international markets is necessary.

The future structure of schools has to adopt curricula and policies that allow for change, fosters the need for collaboration in different sectors, and integrates different learning styles and approaches.

As advocated for by the progressive model of education, the structure should be accommodating to all students, including those who are physically challenged. In other words, education systems have to be more accommodative and progressive in order to give room for new changes and ideas. They should not rely on structured and authoritarian curriculum.

The education and schools systems continue to undergo transformation. The decision of the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas case was a major turning point in the schools systems as it encouraged disintegration of public schools. In addition, a progressive model of education has played a major role in schools and education system as it allows child centered form of education. As part of transformation in education, progressivism philosophy focuses on education and experience.

The model tries to do away with traditional ways of teaching and instead adopt new trend in the education system. Such new trends in the education system have shown progressivism philosophy and what the plaintiffs fought for in the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas case.

School systems have changed and minority students are no longer denied the chance to join public schools. My vision of the education purpose and structure of schools in the future should be based on the progressive model and education offered should be continuous and not static.

Cozzens, L. (1998). Brown v. Board of Education . Web.

Kremer, R. (2005). Progressive education: One parents journey. Education/Ideology , 6(1), 32-42.

Kumar, A. (2004). Philosophical trends, theories of educational intervention and adult learning . Web.

Miller, J. (2004). Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka: Challenging school segregation in the Supreme Court . New York, NY: PowerKids Press.

Stevenson, K. R. (2010). Educational trends shaping school planning, design, construction, funding and operations . Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Building Sciences.

Wilen-Daugenti, T., & McKee, A. G. R. (2008). 21st century trends for higher education: Top trends, 2008–2009. California: Cisco Internet Business Solutions Group.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 28). Brown vs. Board of Education. https://ivypanda.com/essays/brown-vs-board-of-education/

"Brown vs. Board of Education." IvyPanda , 28 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/brown-vs-board-of-education/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Brown vs. Board of Education'. 28 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Brown vs. Board of Education." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/brown-vs-board-of-education/.

1. IvyPanda . "Brown vs. Board of Education." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/brown-vs-board-of-education/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Brown vs. Board of Education." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/brown-vs-board-of-education/.

- Progressivism in the American Reform Period

- Racial Equality in the Brown v Board of Education Case

- Fairness in Schooling: Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision

- Administrative Progressivism in Relation to Online Learning

- Case Brief on the Brown vs Board of Education

- Creating and Implementing Connect-Type Learning Activities

- American Progressivism and Woodrow Wilson

- Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

- The History of Education and Progressivism

- The African American Rights Movement Success

- Online Learning Is a Superior Form of Education

- Meaning of Educational Change

- Re-evaluating Freire and Seneca

- Online Education and Pragmatism

- The development of the American education

The annotated bibliography includes information about related Web resources and teacher materials, as well as fiction and non-fiction books for children, young adults, and adults.

The timeline provides an overview of events related to Brown v. Board of Education, from 1849-2003.

Project Essay (.pdf) This essay by project co-curator Alonzo Smith develops some of the major themes presented in the Separate Is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education exhibition and Web site.

Teacher’s Guide The teacher’s guide complements the curriculum from Reconstruction through the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s to today. Each unit begins with background information for the teacher based on the museum’s Separate Is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education exhibition. Following the narrative are suggested lesson plans. All of the lessons address the historical thinking standards of chronological thinking, historical comprehension, historical analysis and interpretation, and historical issues and decision-making. Along with the guide you will find images, teacher briefing sheets, ands student handouts that accompany each unit.

Electronic Field Trips

Two 50 minute broadcasts, one for middle school students and one for high school students were broadcast on the Internet on May 19, 2004. The archived field trips include a special tour of the Separate Is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education exhibition by curators Alonzo Smith and Harry Rubenstein, film footage from the exhibition, and a Q&A session between curators, and school children from around the country.

For Visiting School Groups

The Museum invites students to connect with people, ideas, and events of the past through an exciting array of standards-based programs.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law