Introduction: The nature of political opposition in contemporary electoral democracies and autocracies

- Open access

- Published: 21 April 2021

- Volume 20 , pages 569–579, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ludger Helms 1

8472 Accesses

12 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

At the level of regime typologies, the uncertain status and inherent weakness of the opposition mark defining features of regimes beyond liberal democracy. However, even the performance and evolution of the latter tend to be shaped by oppositions and the regime’s approach to dealing with them. This article offers a bird’s-eye view of political oppositions in contemporary electoral democracies and competitive autocracies. It focuses on patterns of strategic choices and behavior by both governments and oppositions. That endeavor forms part of a larger joint venture seeking to give center stage to those actors living in the shadows of increasingly unscrupulous power-holders.

Similar content being viewed by others

The limits of institutionalizing predominance: understanding the emergence of Turkey’s new opposition

Bülent Aras & Ludger Helms

The Authoritarian Origins of Dominant Parties in Democracies: Opposition Fragmentation and Asymmetric Competition in India

Adam Ziegfeld

Opposition Party Political Dynamics in Egypt from the 2011 Revolution to Sisi

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Political oppositions beyond liberal democracy: conceptual issues

Democracy is as much about opposition as it is about government. Trantidis ( 2017 ) even suggests that government contestability by an effective opposition should be a constitutive part of any serious definition of democracy. However, opposition is not just a defining feature of democratic governance but of politics more generally. Indeed, to some extent even many oppositions operating in autocratic contexts tend to display some features that are reminiscent of democratic politics, or democratic opposition for that matter. After all, the conviction driving oppositions in fundamentally different types of regime, “that the world can be other than it is (…) that situations can be countered, outcomes altered, people’s lives changed through individual and collective action” (Keane 2009 : 853), is what democracy is ultimately all about.

It took international political science long to recognize the value of studying political opposition across democratic and autocratic regimes. Dahl’s seminal volume of 1966, which remained the unchallenged point of reference in the field for decades, famously focused on political oppositions in Western democracies (Dahl 1966 ). The realization that there can be genuine political opposition in different types of democratic and autocratic regimes did not break much before the turn of the century. A classic paper from this period is the one by Jean Blondel. As Blondel contended, “opposition is a “dependent” concept …. This means that the character of the opposition is tied to the character of the government. The notion of opposition is thus, so to speak, parasitic on ideas of government, of rule, of authority. (…) Yet the recognition that there is a dependence of opposition on government does not mean that variations in types and forms of opposition should not be looked into” (Blondel 1997 : 463).

Given its established status as a subject of international political research, it is curious how elusive, and contested, terminological and conceptual boundaries in this field have remained. While there is much consensus about the quality of government and opposition as any political system’s fundamental “binary code” (Luhmann 1989 ), it is far from universally acknowledged that what is not government in politics is necessarily “opposition.” Some reservations even concern the parliamentary arena in established democratic regimes. Specifically, some scholars have questioned the silent equation of non-government parties and opposition parties in parliament, suggesting that only those non-governing parties in parliament that seek to win governmental office and are viable coalition partners are genuine opposition parties (see, e.g., Niclauss 1995 : 50). Such a position surely can be justified. That said, ever since Sartori’s major work on parties and party systems (Sartori 1976 ), even outright “anti-system parties” have widely been members of the larger family of opposition parties (see also Norton 2008 : 237–238). Recent re-conceptualizations of anti-system parties have been driven specifically by the growing realization that, in many contexts, parties sharing some anti-system properties have effectively become institutionalized and integrated members of democratic political systems (Zulianello 2018 ).

As soon as one moves from here to studying political oppositions in regimes beyond liberal democracy, established terms tend to lose their familiar meanings. For example, anti-system opposition parties that we can find in many autocratic regimes as well are equivalents of anti-system opposition parties in democratic contexts in little more than name. While anti-system parties in democratic systems usually pursue agendas leading away from full-blown liberal democracy, anti-system parties in autocratic regimes are often, though not necessarily or always, committed to the ideals of democratic governance.

Another issue of major conceptual and empirical relevance concerns the status of party-based opposition, and other forms of opposition in different types of political regime. Again, there has been a major debate if or to what extent actors and activities from beyond the parliamentary arena should be considered to form part of “the opposition” at all. It is worth noting that opposition and resistance or dissidence have distinctly different roots in the History of Political Thought (see Jäger 1978 : 471), which has however not hindered contemporary scholars of International Political Theory to refer to opposition and dissidence as two forms of resistance (see Daase and Deitelhoff 2019 ). Moreover, the distinction between opposition and dissidence, or oppositionists and dissidents for that matter, has not just concerned scholars but practitioners, as well. As Szulecki ( 2019 : 22–28) has pointed out in the context of revisiting the politics of dissent in Communist Central Europe, there is a wealth of different notions of opposition, in relation to dissidence; while some understandings consider opposition and dissent as (near) synonyms, others carry genuinely different political meanings. For all that, echoing a passionate call by Brack and Weinblum ( 2011 ), the overall trend in more recent international research has been clearly towards more encompassing notions of political opposition, extending from party politics within and beyond the parliamentary arena to manifestations of protest and dissent.

Empirically, there are distinct patterns of party/parliamentary and non-parliamentary forms of opposition even within a given family of regimes. For example, France has a longstanding tradition of “street politics,” which is conspicuous and exceptional by West European standards, and reflects both an institutionalized weakness of the parliamentary opposition in the Fifth French Republic and a particular arrogance of French executive leadership (Mény 2008 : 103). The major Yellow Vests movement marked just the latest phenomenon of its kind (Grossman 2019 ).

That said, some patterns are more generally related to the type of government or political regime. Specifically, regimes differ fundamentally in the extent to which the electoral and parliamentary arenas provide space for voicing opposition and dissent to power-holders. Generally, the more a given regime leans towards a closed autocracy—the fourth type of regime, alongside electoral autocracies, electoral democracies and liberal democracies, distinguished by Lührmann et al. ( 2018 : 3, Table. 1)—the less likely are the systematic functions of political opposition to be concentrated in the hands of political parties. The “other actors” include individual prominent dissidents, critical media as well as, and not least, participants in mass protests.

One of the most fascinating, and important, features of oppositional politics concerns the relationship between those different actors of the opposition. Overall, the relations between different actors forming part of the opposition have grown more complex and diverse in many regimes, including consolidated democratic systems. While historically parties and movements have been closely intertwined with parties operating as the parliamentary agent of the larger movement (see Maguire 1995 ), the recent past has witnessed a growing separation of oppositional parties and citizen groups in many Western democracies (see Butzlaff and Deflorian 2019 ). However, this applies more to recent developments at the micro-level of party-group (non-)relations in some of the advanced democracies than to other contexts. At the meso- and macro-levels of competitive authoritarian regimes, where possible regime transitions are usually played out, parties have largely reserved their reputation as more or less indispensable agents, equipping would-be leaders with the institutional and organizational resources needed for exerting large-scale political leadership. Belarus, where the protagonists of the mass protests surrounding the presidential election of 2020 and its aftermath eventually decided to form a new party, “Together,” marks a recent case in point (Ivanova 2020 ). Still, other recent evidence, from Russia and beyond, warns against taking the existence of anything like a natural correlation between mounting protests and increased support for the regime’s challengers and opposition parties for granted (Tertytchnaya 2020 ).

Oppositional politics in the era of “personalized authoritarian politics”

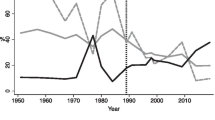

Recent scholarly debate on the global state of democratic and autocratic government has revolved around the rise of “a third wave of autocratization” (Lührmann and Lindberg 2019 ). What marks a distinct stage in the historical evolution of political regimes for some, with conspicuously many contemporary autocratization episodes affecting democracies (ibid: 1103–4), amounts to little more than a questionable set of indicators for others (Skaaning 2020 ). Yet such issues of conceptualization and measurement apart, there is a wide consensus on some of the defining features of the current and recent global transformations of political regimes. These include in particular notions of “executive aggrandizement” (Bermeo 2016 : 10) and “personalized authoritarian politics” (Kendall-Taylor et al. 2017 : 14). Indeed, the executive-centeredness of public attention in the current global state of public affairs is considerably more pronounced than at any time in recent decades (see Andeweg et al. 2020 ).

This is not necessarily bad news for potential challengers. Resent research suggests that “by increasing the degree of personalization, dictators reduce their vulnerability to insider challenges while at the same time increasing their vulnerability to outsider challenges” (Grundholm 2020 : 797). However, in regimes that are not run by outright dictators but autocratic leaders that have been elected and enjoy the support of a sizeable proportion of the population, such as Erdoğan in Turkey or Putin in Russia, there are more particular challenges of personalized rule. As a recent study on the “Erdoğanziation” of Turkish politics suggests, oppositional strategies centering on attacking and disavowing the man at the top personally may backfire. “Contrary to what the opposition leaders aimed to achieve, the negative agenda antagonized Erdoğan supporters and consolidated their in-group identity” (Selçuk et al. 2019 : 559; see also Aras and Helms 2021 ). Thus, overall, personalized competitive autocratic regimes are certainly not generally a more favorable playing ground for the opposition than other forms of autocratic or quasi-autocratic rule.

This symposium seeks to give center stage to the undervalued and understudied actors of the political opposition. It launches an agenda dedicated to providing consequently opposition-focused—and thus distinctly complementary—assessments of typically leader-centered electoral democracies and autocracies. While the case studies gathered for this symposium focus on European countries (with Turkey and Russia marking border cases), the next section of this introductory piece seeks to capture the nature of political oppositions beyond liberal democracy on a larger scale, accounting for issues and features observed both in and outside of Europe.

Political oppositions beyond liberal democracy: Some empirical features and patterns

The group of “political regimes beyond liberal democracy” that do not fall in the residual category of closed autocracies is immensely complex and diverse. Nevertheless, there are certain shared features, some of which are of immediate relevance in our context. As to elections and election-induced uncertainty, what can be largely taken for granted in electoral democracies is true for competitive authoritarian regimes or electoral autocracies, as well. “Even though democratic institutions may be badly flawed, both authoritarian incumbents and their opponents must take them seriously” (Levitsky and Way 2002 : 54), and notwithstanding the uneven playing field between government and opposition, incumbents can still lose elections. Arguably the single most important lesson emerging from an opposition-centered exploration into the world beyond liberal democracy is that even seemingly “primitive” competitive autocratic regimes (as well as closed autocracies) can be home to complex strategies of both incumbent and opposition actors (see Schedler 2013 ).

First, the strategic goal of governments in electoral autocracies cannot be reasonably reduced to simply banning any political oppositions altogether. Actually, the recent experience of Hong Kong, where Chinese power-holders not only banned the opposition from the streets but more recently also expelled defiant opposition members from parliament, marks an exception rather than the rule. As Armstrong et al. ( 2020 : 2) have observed, “in many of today’s autocracies … regime leaders divide the political opposition into a systemic component that is allowed to participate in official politics and a non-systemic component that is excluded from elections, spoils distribution, and policymaking.” In some settings, the “systemic” opposition is called the “loyal” or “official” opposition. Excluded groups meanwhile are sometimes referred to as the “radical opposition” or the “unrecognized opposition.” Prominent examples stretch from Suharto’s Indonesia and South Africa under apartheid to the Arab world. More specifically, autocratic power-holders can have a strong interest in allowing the existence of certain opposition groups as part of their legitimation or survival strategies (see Magaloni and Kricheli 2010 : 126–128). This may include the creation of “Ersatz” opposition parties to create the appearance of multiparty competition (see March 2009 ).

Second, not all opposition parties in electoral autocracies are invariably committed to overthrowing the regime . As Dettman notes, “the literature on democratization has tended to assume a fixed regime-changing or democratizing goal of opposition parties” (Dettman 2018 : 33), but non-government/opposition parties “can be pro-regime, showing willingness to join the ruling government and showing little outward evidence of pursuing regime change” (ibid: 36). Actually, this does not apply to opposition parties only; even social and protest movements, whose very raison d’être is generally believed to be about generating change, are not always progressive forces advancing democratization (see, e.g., Albrecht 2005 ; Kitirianglarp and Hewison 2009 ).

Third, opposition parties, actors or groups that are anti-government and anti-regime may still use fundamentally different strategies. This may include the formation of pre-election alliances and post-election coalitions, as well as organizing electoral boycotts. While there are few, if any, hard-and-fast rules of how exactly to deal with particular challenges, research on political oppositions in Venezuela and Colombia suggests that it is worthwhile for the opposition to make use of the institutional leverage a regime provides them with, rather than to rely primarily or exclusively on radical extra-institutional strategies (Gamboa 2017 ).

Cooperation and coalition-building between opposition actors have increasingly become an issue in its own right. While conventional wisdom holds that “there is no coalition in opposition” in democratic party government contexts, collective opposition strategies are notably widespread in autocratic regimes. Pre-electoral coalitions existed in a quarter of all authoritarian elections held in the first decade of the twenty-first century (Gandhi and Reuter 2013 : 140; see also Dettman 2018 : 57). Electoral coalitions among different opposition parties have proven successful in unseating incumbents from the Ukraine to the Philippines and Kenya, as well as in some cosmopolitan cities like Istanbul and Budapest. The most impressive recent example at the national level, however, relates to Malaysia, where the oppositional coalition Pakatan Harapan (or Hope Alliance) won the federal elections in 2018 for the first time in the history of the country (see Ufen 2020 ).

Systematic comparative research on electoral coalitions suggests that, other things being equal, the willingness of the opposition to form pre-electoral coalitions tends to increase when opposition actors do not expect the incumbent regime to win, that is, when change seems likely or at least possible. What is also worth noting is that coalitions that include previous regime insiders who defected to the opposition have often been more successful (Hauser 2019 ). Partly contrary to this, recent research on Morocco suggests that the recent increase in collaboration between the oppositional Left and Islamist movements was favored precisely by “the excluded nature of these actors and their lack of electoral interests” (Cassani 2020 : 1183). Other research has pointed out that electoral successes and defeats of opposition coalitions depend strongly on the willingness of voters to support the coalescing strategies of party leaders, policies and policy preferences (Gandhi and Ong 2019 ) as well as psychological characteristics of individuals (Young 2020 ), which matter in autocratic contexts just as much as they usually do in democracies. Balancing these diverging preferences is at the heart of the observed dilemmas faced by systemic and non-systemic oppositions seeking cooperation with each other (see Armstrong et al. 2020 ).

Opposition boycotts mark an alternative election-related strategy of opposition parties that has been particularly prominent in Africa, but by no means strictly confined to that region. Most early work on boycotts suggests that opposition parties will boycott in particular when they believe they will do poorly in a given election, that is, essentially to “save face.” However, as a recent major study on political oppositions in Arab regimes contends, “the strategies adopted by opposition groups during and after authoritarian elections are driven by perceptions of regime strength and stability, extending well beyond election-related considerations, such as the freeness and fairness of the election and an opposition group’s prospects of victory at the polls” (Buttorff 2019 : 7).

While boycotts are in one sense a non-violent tactic that opposition parties may adopt to gain concessions from authoritarian powers, they can also be part of a larger strategy to inspire post-election protests that may ultimately undermine the stability and authority of a given regime. Apart from elusive losses of reputation, boycotts tend to produce lower turnout, “which can make the incumbent vulnerable to future criticisms and electoral challenges” and thus “may open up the electoral playing field further in the long term, allowing for future opposition victories” (Hauser 2019 : 21). Importantly, however, as Dettman ( 2018 : 256) points out, even “opposition parties that win power by unseating the incumbent through elections face the choice of implementing democratizing reforms, or preserving the advantages of authoritarian incumbency” (see also Wahman 2014 ).

What seems important to add under the heading of strategic agency of opposition actors in competitive autocratic regimes is that oppositional strategies are clearly not limited to the electoral or parliamentary arenas. As Bedford and Vinatier ( 2019 ) remind us in their carefully conceptualized study of “oppositional ghettos” and “resistance models,” electoral activities can equally well focus on the media, lobbying or educational activities. As the authors further contend, a common characteristic of these different “models of resistance” is that challenging the current authorities’ hegemony often takes priority over achieving any long-term goals that may be impossible to realize. In that sense, “the opposition actors’ work becomes “oppositional for the sake of it”” (ibid: 707).

Fourth, regime types do matter even in authoritarian contexts . Overall, while in the family of democratic regimes it is generally parliamentary systems that offer the most favorable opportunity structures to opposition parties (Helms 2008 ), the chances for political oppositions in autocratic contexts to leave their mark on the wider political process often seem to be better in presidential than in other types of autocratic regime. Opposition parties can nominate a widely popular individual for election, even if they struggle to appeal to voters in legislative elections (Dettman 2018 : 75). Also, electoral coalitions have been particularly successful in presidential autocracies (Gandhi and Ong 2019 : 949–950). Other differences that exist are more difficult to assess in terms of failure and success. For example, boycotts have been more frequent in presidential elections, as Hauser ( 2019 : 20) suggests, though this says little about the ultimate successes of opposition forces to oust incumbent autocrats.

Fifth, regime-related legacies matter. There is reason to believe that it makes much of a difference if a regime turns into an electoral autocracy from a formerly closed autocracy, or from a more democratic type of regime. This is because dictatorships have distinct legacies and tend to cast a particular shadow on political oppositions and their tactical and strategic choices (see Bermeo 1992 : 273–274; for a more recent example, see also Conduit and Akbarzadeh 2019 : 8). Importantly, those legacies do not have to be of a toxic nature. Rather, the hurtful memory of massacres under the previous regime may drive new oppositions to pursue mainly peaceful strategies.

The articles and key findings of this symposium

The cases gathered for this symposium share one major common feature with each other: With few exceptions, all major countries covered here were identified as prime examples of autocratization in the latest V-Dem Democracy Report of 2020 which focuses on the developments of the past decade. The single most important exception concerns Russia, where the democratic rollback set in a full decade earlier, with no significant reverses recorded ever since. Another thing that unites these articles, or their authors for that matter, is the belief that the institutional parameters characterizing a given regime tend to shape oppositional behavior and performance to a considerable extent. After all, virtually all agency in politics is “structured agency,” and all strategies—that guide the actions of political actors in opposition and elsewhere—are little else but ideas for, or manifestations of, rational behavior seeking to exploit institutional (and other contextual) opportunities to advance the achievement of particular goals (Helms 2014 ). However, this does not imply that institutions would ever actually determine the behavior and fate of actors pursuing competing missions in complex environments. Indeed, the articles of this symposium provide fresh evidence for the limits of purely institutional explanations of oppositional performance.

Further, in line with the established tradition of small-n political research, which is at its best when it comes to identifying new causalities and developing hypotheses for future research, rather than testing sweeping theories, the majority of articles proceeds inductively in capturing key features of the politics of opposition in these countries. In a field that has been infamous for the striking immunity of its key subjects to grand-scale theorizing (see De Giorgi and Ilonszki 2018 : 244), anything else would seem unreasonable and misplaced.

In his article on political opposition in Putin’s Russia, Andrey Semenov offers a succinct assessment of the complex evolutionary dynamics of the past two decades. The particular focus of this piece is on the regime’s continuous efforts to deal with its challengers by operating a sophisticated system of organizational control, and the oppositions’ desperate attempts of coping with this. Focusing on Erdoğan’s Turkey, Bülent Aras and Ludger Helms show how the attempts of a longstanding power-holder to tighten his grip, and institutionalize his predominance, may generate inverse effects by creating unintended incentives for opposition actors to pool their resources.

Both articles provide new evidence for the well-founded assumption that longstanding political strongmen and their supporters can give opponents and oppositions a particularly hard time. Still, their findings are not at odds with the observation that “personalizing autocrats” are marked by a particular vulnerability to challengers and challenges from beyond their close environment. Overall, recent opposition-related developments in Turkey have been considerably more heartening than developments in Russia. This finding is in line with other recent research suggesting that—notwithstanding apparent parallels between “Erdoğanism” and “Putinism”—for the time being at least, Erdoğan’s Turkey and Putin’s Russia, remain distinctly different regimes (see Bechev and Kınıklıoğlu 2020 ).

Two comparative analyses follow these two single-case studies of the symposium. Authored by Gabriella Ilonszki and Agnieszka Dudzińska, the first one of these assesses oppositional behavior in Hungary and Poland—two “post-communist” EU member states. Finally, Claudia Laštro and Florian Bieber provide a wide-ranging comparative assessment of the political opposition in the three competitive authoritarian regimes of the Western Balkans, i.e. Montenegro, Serbia and North Macedonia.

Echoing the lessons drawn by Aras and Helms, the key findings of these two papers point to the limits of purely institutional (as well as cultural and historical) explanations of political opposition. Neither institutional similarities nor shared historical legacies determine the nature of political opposition. There is no single pattern of opposition politics valid across these samples of cases, and no determining effect of contextual parameters. Political agency (of both governments and oppositions) shapes the patterns of oppositional power and performance to a significant extent. These findings concur with other recent research on the varied performance of Central and Eastern European political oppositions during the Corona pandemic (see Guasti 2020 ).

For oppositions in political regimes beyond liberal democracy, the central proposition emerging from this symposium is that their actions can make all the difference.

Albrecht, H. 2005. How can opposition support authoritarianism? Lessons from Egypt. Democratization 12 (3): 378–397.

Google Scholar

Andeweg, R.B., R. Elgie, L. Helms, J. Kaarbo, and F. Müller-Rommel. 2020. The political executive returns: Re-empowerment and rediscovery. In The Oxford handbook of political executives , ed. R.B. Andeweg, et al., 1–22. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aras, B., and L. Helms. 2021. The Limits of institutionalizing predominance: Understanding the emergence of Turkey’s new opposition. European Political Science . https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00327-9 .

Article Google Scholar

Armstrong, D., O.J. Reuter, and G.B. Robertson. 2020. Getting the opposition together: Protest coordination in authoritarian regimes. Post-Soviet Affairs 36 (1): 1–19.

Bedford, S., and L. Vinatier. 2019. Resisting the irresistible: ‘Failed opposition’ in Azerbaijan and Belarus revisited. Government and Opposition 54 (4): 686–714.

Bechev, D. and S. Kınıklıoğlu, 2020. Turkey and Russia: No birds of the same feather . SWP Comment No. 24, Berlin: Center for Applied Turkish Studies.

Bermeo, N. 1992. Democracy and the lessons of dictatorship. Comparative Politics 24 (3): 273–291.

Bermeo, N. 2016. On democratic backsliding. Journal of Democracy 27 (1): 5–19.

Blondel, J. 1997. Political opposition in the contemporary world. Government and Opposition 32 (4): 462–486.

Brack, N., and S. Weinblum. 2011. “Political opposition”: Towards a renewed research agenda. Interdisciplinary Political Studies 1 (1): 69–79.

Buttorff, G.J. 2019. Authoritarian elections and opposition groups in the Arab World . Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Butzlaff, F., and M. Deflorian. 2019. Die neue alltagspolitische Opposition (APO)? Wie Parteien und Nischenbewegungen auseinanderdriften. INDES 3: 43–54.

Cassani, A. 2020. Cross-ideological coalitions under authoritarian regimes: Islamist-left collaboration among Morocco’s excluded opposition. Democratization 27 (7): 1183–1201.

Conduit, D., and S. Akbarzadeh. 2019. Contentious politics and Middle Eastern oppositions after the uprisings. In New oppositions in the Middle East , ed. D. Conduit and S. Akbarzadeh, 1–14. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Daase, C., and N. Deitelhoff. 2019. Opposition and dissidence: Two modes of resistance against international rule. Journal of International Political Theory 15 (1): 11–30.

Dahl, R.A., ed. 1966. Political oppositions in Western democracies . New Haven: Yale University Press.

De Giorgi, E., and G. Ilonskzki. 2018. Conclusions. In Opposition parties in European legislatures: Conflict or consensus? , ed. E. De Giorgi and G. Ilonszki, 229–246. London: Routledge.

Dettman, S. 2018. Dilemmas of opposition: Building parties and coalitions in authoritarian regimes . Ph.D.-Dissertation, Cornell University.

Gamboa, L. 2017. Opposition at the margins: Strategies against the erosion of democracy in Colombia and Venezuela. Comparative Politics 49 (4): 457–477.

Gandhi, J., and O.J. Reuter. 2013. The incentives for pre-electoral coalitions in non-democratic elections. Democratization 20 (1): 137–159.

Gandhi, J., and E. Ong. 2019. Committed or conditional democrats? Opposition dynamics in electoral autocracies. American Journal of Political Science 63 (4): 948–963.

Geddes, B., J. Wright, and E. Frantz. 2018. How dictatorships work . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grossman, E. 2019. France’s yellow vests-symptom of a chronic disease. Political Insight 10 (1): 30–34.

Grundholm, A.T. 2020. Taking it personal? Investigating regime personalization as an autocratic survival strategy. Democratization 27 (5): 797–815.

Guasti, P. 2020. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in central and Eastern Europe. Democratic Theory 7 (2): 47–60.

Hauser, M. 2019. Electoral strategies under authoritarianism: Evidence from the former Soviet Union . Lanham: Lexington/Lynne Rienner.

Helms, L. 2008. Studying parliamentary opposition in old and new democracies: Issues and perspectives. Journal of Legislative Studies 14 (1–2): 6–19.

Helms, L. 2014. Institutional analysis. In The Oxford Handbook of political leadership , ed. P.T. Hart and R.A.W. Rhodes, 195–209. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ivanova, P. 2020. Belarus opposition leaders to create new political party, The Independen t, 1 September 2020, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/belarus-protests-opposition-election-maria-kolesnikova-lukashenko-together-a9697916.htm

Jäger, W. 1978. Opposition. In Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe , vol. 4, ed. O. Brunner, et al., 496–517. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Keane, J. 2009. The life and death of democracy . New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Kendall-Taylor, A., E. Frantz, and J. Wright. 2017. The global rise of personalized politics: It’s not just dictators anymore. The Washington Quarterly 40 (1): 7–19.

Kitirianglarp, K., and K. Hewison. 2009. Social movements and political opposition in contemporary Thailand. The Pacific Review 22 (4): 451–477.

Levitsky, S., and L.A. Way. 2002. Elections without democracy: The rise of competitive authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy 13 (2): 51–65.

Luhmann, N. 1989. Theorie der politischen Opposition. Zeitschrift Für Politik 36 (1): 13–26.

Lührmann, A., and S.I. Lindberg. 2019. A third wave of autocratization is here: What is new about it? Democratization 26 (7): 1095–1113.

Lührmann, A., M. Tannenberg, and S. Lindberg. 2018. Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening new avenues for the comparative study of political regimes. Politics and Governance 6 (1): 60–77.

Magaloni, B., and R. Kricheli. 2010. Political order and one-party rule. Annual Review of Political Science 13: 123–143.

Maguire, D. 1995. Opposition movements and opposition parties: Equal partners or dependent relations in the struggle for power and reform? In The politics of social protest. Comparative perspectives on states and social movements , ed. J.C. Jenkins and B. Klandermans, 99–112. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

March, L. 2009. Managing opposition in a hybrid regime: Just Russia and parastatal opposition. Slavic Review 68 (3): 504–527.

Mény, Y. 2008. France: The institutionalization of leadership. In Comparative European politics , ed. J.M. Colomer, 94–134. London: Routledge.

Niclauss, K. 1995. Das Parteiensystem der Bundesrepublik Deutschland . Paderborn: Schöningh.

Norton, P. 2008. Making sense of opposition. Journal of Legislative Studies 14 (1–2): 236–250.

Sartori, G. 1976. Parties and party systems . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schedler, A. 2013. The politics of uncertainty: Sustaining and subverting electoral authoritarianism . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skaaning, S.-E. 2020. Waves of autocratization and democratization: A critical note on conceptualization and measurement. Democratization 27 (8): 1533–1542.

Selçuk, O., D. Hekimci, and O. Erpul. 2019. The Erdoğanization of Turkish politics and the role of the opposition. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 19 (4): 541–564.

Szulecki, K. 2019. Dissidents in communist central Europe: Human rights and the emergence of new transnational actors . Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Tertytchnaya, K. 2020. Protests and voter defections in electoral autocracies: Evidence from Russia. Comparative Political Studies 53 (12): 1926–1956.

Trantidis, A. 2017. Is government contestability an integral part of the definition of democracy? Politics 37 (1): 67–81.

Ufen, A. 2020. Opposition in transition: Pre-electoral coalitions and the 2018 electoral breakthrough in Malaysia. Democratization 27 (2): 167–184.

Whaman, M. 2014. Democratization and electoral turnovers in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond. Democratization 21 (2): 220–243.

York, E.A. 2020. Democratic Institutions under autocracy , Ph.D. thesis, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Columbia University.

Young, L.E. 2020. Who dissents? Self-efficacy and opposition action after state-sponsored election violence. Journal of Peace Research 57 (1): 62–76.

Zulianello, M. 2018. Anti-system parties revisited: Concept formation and guidelines for empirical research. Government and Opposition 53 (4): 653–681.

Download references

Acknowledgments

I am immensely grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the editors of this journal, in particular Daniel Stockemer, for their most valuable constructive critique of an earlier draft of this paper and this Symposium more generally. Further, I gratefully acknowledge the generous support by Agnieszka Dudzińska and David M. Willumsen who commented on a previous draft of this intro piece. Finally, I would like to thank Sebastian Dettman for kindly sharing his unpublished Cornell PhD dissertation, and the inspiration provided by this major work. Needless to say, the usual disclaimer applies.

Open Access funding provided by Universitat Innsbruck.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Innsbruck, Universitätsstraße 15, 6020, Innsbruck, Austria

Ludger Helms

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ludger Helms .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Helms, L. Introduction: The nature of political opposition in contemporary electoral democracies and autocracies. Eur Polit Sci 20 , 569–579 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00323-z

Download citation

Accepted : 08 February 2021

Published : 21 April 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00323-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Competitive autocracies

- Electoral democracies

- Political opposition

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

2 Government and Opposition

- Published: September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The success of democracy rests in large part on both the opposition and the government. In order for democracy to operate successfully, the opposition must be recognized as legitimate and given an institutional form. The emergence of the political party as an institution has played a critical role in shaping the relationship between government and opposition as a distinctive feature of democratic political systems. This chapter discusses the contribution of the party system to the development of a symbiotic relationship between government and opposition, focusing on the case of Britain. It examines the role of the opposition, and the relationship between government and opposition, both within and outside Parliament, in India. It also considers ‘partyless democracy’ in India along with factions and factional politics, party politics, and the importance of trust between government and opposition in strengthening the foundations of democracy.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Welcome {{logInuser.firstName}} (Logout)

- Daily Articles

Role of Opposition in Democracy

- Date: {{formatDate('Mon Nov 15 2021 21:36:18 GMT+0530 (India Standard Time)') }}

- By: Empower IAS

- For More Updates: Telegram

Opposition in Democracy Meaning :

- Opposition is the largest non-government party or coalition of parties who are elected representatives of peoples, who are not members of the treasury benches and play an important role of questioning government decisions and actions and also raised matter of public importance in functioning political democracy .

Role and functions of opposition in democracy :

1- Constructive criticism of the Govt. policies, plans, bills, law and programs, and make the Govt. to work in accordance with social welfare and public good.

2- Main role of the opposition is to question the ruling Govt. and hold them accountable to peoples.

3- Opposition carry the suggestions of the civil society to the parliament/ ruling Govt.

4- Opposition should not criticize each and every decision of the ruling Govt. but its support is necessary to the decisions which are good and in public interest.

5- Constructive opposition expose the weakness of the ruling Govt.

6- Opposition is the guardian of the public interest and remind the ruling Govt. its duty towards the people who elected them to power.

7- Opposition and the ruling party are the two faces of the same coin.

8- Opposition provides checks and balances in the functioning of democracy e.g., members of opposition included in various parliamentary committees.

9- Members of the opposition who are members of parliamentary committees have a further opportunity to scrutinize new legislation as part of the committee process.

10- Opposition may utilize the media to reach the electorates with its views.

Malfunctioning of opposition in parliamentary proceedings :

- Fragmented opposition : Degree of fragmented opposition has consequences for the electoral performance of the parliamentary proceedings.

- Agenda for discussion: The Govt. alone has the right to set the agenda for discussion but some times opposition trying to distract discussion and raised other issues in house which creates hurdles in time management .

- Interruption: Interjection by a member during the speech of another member/discussion on a listed item.

- Disruption: A longer break in parliamentary proceedings, encompasses an undesired statement, action and gesture that delay the transaction of business in house, also violates the dignity of house e.g., showing placards, shouting of slogans, entering the well of the house, and adjournment motions.

- Walk-outs : Constitutes a legitimate form of protest to show their disagreement with ruling Govt.

Leader of opposition (LOP) :

- LOP is only the leader for the time being of the Chief Opposition Party (2nd main party temporarily in a minority), who are ready to form an alternative govt. when time arises. The process of parliamentary govt. will break down if there is absence of mutual tolerance. Meeting of the LOP with the Prime Minister/ Ministers, helps to remove barriers in parliamentary proceedings to reach on constructive solutions. LOP with the helps of other opposition members demands debates, watches for encroachment on the rights if minorities.

- LOP can develop his own proposals and policies without the power to implement them.

- In India LOP on Lower House and the Counsel of States are accorded statutory recognition. Recommendation of PAGE committee suggest that the leader of the largest recognised opposition party should be recognised as the LOP.

Role of opposition in various parliamentary committees:

1- Public Accounts Committee : is a committee of elected members of parliament to check expenditures bill and the Audit report of CAG after it is laid in the Parliament. PAC consists of not more than 22 members. PAC is headed by the LOP. Presently Adhir Ranjan Chowdhary is chairperson of PAC.

2- Standing Committees : is a committee consisting of MPs. These committees constituted as per "Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business" of Parliament. Members of opposition who are nominated in these committees give their contribution via raising issues related to general public and good,

3- Ad-hoc committees : are formed for specific purpose such as Select and Joint Committees on Bills.

Measures to strengthen role of opposition in enriching democracy :

1- Provisions related to give right to hold ruling party accountable instead of having to resort to disruptions of the house may introduce in rules for conduct of business in the Parliament.

2- There should be provisions to answer every question of the opposition's parties,

3- "Opposition days" is a parliamentary oversight mechanism under which certain days has to be allotted for the opposition parties to set the agenda of the house.

4- Presently Parliamentary time is controlled by ruling party which, as a rule, does not give sufficient time for opposition to seek matters of public importance.

Conclusion:

Functional parliamentary democracy completely depends upon political maturity of the elected representatives which make check and balances on the Executive and Legislature, and also fixed the accountability of the executive to improve the governance. In India as a parliamentary democracy a strong opposition is indispensable in a modern democracy.

Related Posts

- {{posts.publishedAt | formatDate}}

{{posts.title |formatSubStrin(posts.title,50)}} {{posts.title |formatSubStrin(posts.title,50)}}

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Role of Opposition in a Democracy: A Bibliometric Analysis

Related Papers

Muhammad Akhtar Rind

Sebnem Cansun

This study investigates the bibliometric characteristics of publications on democracy in Turkey, a country arguably having recently gone through a particular democratic backsliding. Focusing on SSCI and A&HCI between 1980 and 2019, a total of 691 publications were found: articles (83.79%) and book reviews (11.43%), with a particular increase of publications starting with the late 2000s. Most of the publications were written in English (95%), under the research category of Political Science. Turkish Studies was the journal where most of the publications appeared. The phrases that were mostly used within abstracts were the Justice and Development Party, the European Union, the Middle East, and democracy in Turkey. The results show that publications on democracy tend to appear mostly in regionally focused journals, be written mostly in the Political Science research category and in English, highlight the contemporary democratic advances and deficiencies of the countries, and be mostly within comparative frameworks. Öz Bu çalışma, son zamanlarda özel bir demokratik gerileme geçirdiği iddia edilen ülke Türkiye'de, demokrasi üzerine yayınların bibliyometrik niteliklerini incelemektedir. SSCI ve A&HCI'de 1980 ile 2019 arasında toplam 691 yayın bulunmuştur: makaleler (%83,79) ve kitap incelemeleri (%11,43) 2000'lerin sonunda özel bir artış göstermektedir. Yayınların çoğu İngilizce (%95), Siyaset Bilimi, araştırma kategorisinde yazılmıştır. En çok yayının basıldığı dergi Turkish Studies'dir. Yayın özetlerinde en sık kullanılan ibareler Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, Avrupa Birliği, Ortadoğu ve Türkiye'de demokrasi'dir. Sonuçlar, demokrasi üzerine yayınların ağırlıkla bölgesel odaklı dergilerde çıktığını, çoğunlukla Siyaset Bilimi araştırma kategorisinde ve İngilizce yazıldığını, ülkelerin güncel demokratik ilerleme ve eksikliklerine dikkat çektiğini ve özellikle karşılaştırmalı çerçevede olduğunu göstermektedir.

Nathalie Brack

JWP (Jurnal Wacana Politik)

Muhammad Syaifuddin

Politics is a discipline of science that is part of social science. What distinguishes political science from other social sciences is the object studied. The development of research on the theory of political science and politics becomes a question in this paper. Topic mapping and topic classification based on keywords, countries, and themes discussed were the main focus of this research, including visual density based on keywords, showing the level of saturation political science theory. In this study, the data used were data that had been downloaded from the Scopus database with several limitations to limit and be more specific to the results of the discussion. After the documents to be reviewed and analyzed are bibliographical using the VOSViewer and NVivo 12 Plus software, the data is exported .CSV and .RIS formats. This study aims to provide insights into subsequent research on the theory of political science

DEMOCRACIES UNDER PRESSURE A GLOBAL SURVEY (VOLUME I)

Dominique Reynie