Nursing Workload and Patient Safety Essay

Introduction, nurses are not overworked, nurses are overworked, both views are right or wrong.

The United States faces an increased demand for nursing professionals in hospitals and other health care facilities. On the other hand, the number of nurses graduating into the profession is not increasing in the same rate as their demand. As a result, hospitals and other health institutions have to increase the working times of the present nurses. It is now common for nurses to work extensively on overtime just to match the demand for their services. The issue causes nurses to suffer fatigue, which compromises their patient care ability. I strongly disagree with the above claim that nurses are overworked.

Nurses face various situations in the hospital that require them to make rational choices instantly. They receive training on how to deal with emergencies as well as normal health conditions. Thus, the claim of overworking nurses is false. Many people go into the nursing profession due to their passions to assist people and not for the money. Therefore, they are motivated to assist as many patients as possible.

Previously, the government trained very few nurses. However, nurse shortages prompted for a reversal of that policy (Chang, et al., 2005). The nursing selection and training is vigorous enough to eliminate any person not keen on the professional demands of nursing. Everyone who becomes a nurse knows that the job requires his or her commitment at all times. Although they enjoy day offs, leaves and normal working hours, nurses know that they should be on call always. The nature of emergencies does no give nurses the luxury of avoiding overtimes at work.

There are different aspects of nursing, apart from general nursing, which require additional skills and proficiency. These specialization demand extra commitments on the part of the nurse during training (Carayon & Gurses, 2008). Given that the specialized nurses attract a higher pay than general nurses do, the professions attract many applicants. People who have a calling on helping people would like to do so with a high pay. The high number of applicants forces institutions to use a rigorous selection process. The process ensures that only the best and most prepared for the profession eventually turn to be nurses. The demanding process prepares all nurses for what will later come when they are in the job.

Complaints saying that nurses are overworked point to their negligence at work as an effect. Some say that nurses are uncaring. People expect nurses to share emotional connections with their patients. The reality is that nurses handle many cases in a day and they cannot afford to attach themselves. This does not imply that they are uncaring. It also does not mean that they are overworked.

Just like with any other profession, nurses are free to seek medical attention when they are not feeling good. They suffer from the effects of the economy like everyone else. Some face difficulties in some areas of their lives. Different personal conditional affecting nurses cause them to deviate from properly doing their jobs. As far as the nursing job goes, its demands do not exceed the capabilities of the people who serve as nurses. Some nurses do a terrible job, and complain of being overworked. Some hospitals face budget cuts and are understaffed. However, such cases are minute and their solutions appear immediately people raise complaints. These few cases do not represent the entire situation for nurses. Nurses work normally and receive compensation whenever they do overtime. Therefore, there is no issue of overworking.

On the other hand, nurses might actually be overworked. The characteristics of bad nurses offer signs of being overwhelmed (Chang, et al., 2005). Some nurses appear to neglect basis procedures and hygiene requirements (Rauhala, et al., 2007). For example, they have hanging hair, wear dirty shoes and smoke in or around hospitals. Patients complain that nurses neglect them. Nurses have many cases to attend. They prefer to deal with the straightforward cases and leave the complicated cases for later. Unfortunately, there is no later for nurses; patients keep streaming into hospitals. Therefore, the neglected patients are a sign of nurse work overload. Some people go into the profession to earn money. If you are motivated to earn more, then work becomes too much as long as your pay does not match your expectations. A high number of dropouts from nursing degrees indicate that the process is arduous. If the training process is that difficult, then what people are training for will demand much more than the training.

Based on the above arguments for both sides, the two positions could all be right. We can say that nurses are not overworked and at the same time say that nurses are overworked. The first part is a disagreement with the claim that nurses are overworked. This part shows that money is not the main attractiveness of the nursing profession. Therefore, it is wrong to equate the amount earn with the time put to work, and then use that to claim a work overload. The argument rightfully shows that the rigorous training for nurses equips them for the demands of their jobs. Since they are well equipped to handle the situations arising in hospitals, nurses should not claim to be overworked.

The second part of the argument could also be right. It points to the signs of negligence, which may point to a work overload situation. Yes, when nurses are seeing too many patients in a day, they will prefer to work with the easy cases. Eventually this will present a pile of neglected complicated cases. During their breaks, nurses become hostile to patients, which are an indication that they are facing many demands from work (Fitzpatrick, 2006). They would not like more work demands creeping into their personal time.

Again, assuming another perspective, both arguments for and against nurse’s work overload could be wrong. Rigorous training does not necessarily prepare a person for the emergencies that appear in actual nurse work. The training mindset is different from the working mindset. Secondly, the calling to help other people has its limits. When the demand of work is overwhelming, people would demand more compensation even if they like their jobs. Similarly, claiming that the signs of negligence are indications of work overload is wrong. There are different parameters within and outside the nursing career that influence a nurse to neglect their primary work duties (Carayon & Gurses, 2008).

Overall, the issue of work overload is not important. At any time, there would be mismatches in the number of staff and patients. It is the duty of management to balance the two variables. However, as explained above, each side of the argument has a valid case point. The issue of nurse work overload depends on the perspective that one chooses.

Carayon, P., & Gurses, A. P. (2008). Nursing workload and patient safety – A human factors engineering perspective. In H. R. G (Ed.), Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcase Research and Quality.

Chang, E. M., Hancock, K. M., Johnson, A., Daly, J., & Jackson, D. (2005). Role stress in nurses: Review of related factors and strategies for moving forward. Nursing & Health Sciences, 7 (1), 57-65.

Fitzpatrick, J. J. (Ed.). (2006). Encyclopedia of Nursing Research. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Rauhala, A., Mika, K., Lisabeth, F., Marko, E., Mariana, V., Jussi, V., et al. (2007). What degree of work overload is likely to cause increased sickness absenteeism among nurses? Evidence from the RAFAELA patient classification system. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 57 (3), 286-295.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, April 28). Nursing Workload and Patient Safety. https://ivypanda.com/essays/nursing-workload-and-patient-safety/

"Nursing Workload and Patient Safety." IvyPanda , 28 Apr. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/nursing-workload-and-patient-safety/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Nursing Workload and Patient Safety'. 28 April.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Nursing Workload and Patient Safety." April 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/nursing-workload-and-patient-safety/.

1. IvyPanda . "Nursing Workload and Patient Safety." April 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/nursing-workload-and-patient-safety/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Nursing Workload and Patient Safety." April 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/nursing-workload-and-patient-safety/.

- Are Australian Employees Overworked?

- The Role of Nurses and the Pressures They Face on a Daily Basis

- A Nursing Shortage Article by Marc et al.

- Iron Overload Diagnosing and Treating

- Emergency Medical Care and Nursing Overwork

- Solution to Overwhelming Amount of Work in College

- Organizational Structure in Business

- Vincent Valley Southview Clinic's Analysis

- Creating Environments for Excellence in Nursing

- Health Policy in the US Analysis

- Identifying Nursing Values and Realms of Caring

- Trends in Nursing, Leadership Styles, Career Plans

- The Responsibility of Professional Nurses

- Human Dignity in Nursing

- “The Evolution of the New Environmental Metaparadigms of Nursing” by Kleffel

Nursing workload: a concept analysis

Affiliation.

- 1 Hahn School of Nursing and Health Science, University of San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA.

- PMID: 26749124

- DOI: 10.1111/jonm.12354

Aim: The aim of the present study was to develop a comprehensive understanding of the concept 'workload' within the nursing profession in order to arrive at a clear definition of nursing workload based on the evidence in existing literature.

Background: Nursing workload is a common term used in the health literature, but often without specification of its exact meaning. Concept clarification is needed to delineate the meaning of the term 'nursing workload'.

Method: A concept analysis was conducted using Walker and Avant's method to clarify the defining attributes of nursing workload. As the subject matter was nursing focused, only one database was searched, the Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Articles that did not use 'workload' in the title or abstract were excluded. A model case, contrary case, related case and empirical referents were constructed to clarify the concept and to demonstrate how the workload is captured by the main attributes.

Results: The attributes of nursing workload found in the literature fall into five main categories: the amount of nursing time; the level of nursing competency; the weight of direct patient care; the amount of physical exertion; and complexity of care. The attributes were organised according to the leading antecedents, which were identified as the patient, nurse and health institution.

Implications for nursing management: Nurse managers need to address the workload issues with regard to the real nature of nursing work; this could increase nurses' productivity, nurses' satisfaction, turnover, work stress and provide sufficient staffing to patient care needs.

Conclusion: The concept analysis demonstrated clearly the complexity of the concept and its implications for practice and research. It is believed that the current concept analysis will help to provide a better understanding of nursing workload and contribute towards the standardisation of the nursing workload and the development of a valid and reliable measurement system.

Keywords: acuity; competency; complexity of care; intensity; nursing workload; staffing.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Publication types

- Attitude of Health Personnel

- Concept Formation*

- Workload / standards*

- Open access

- Published: 07 July 2023

The association between workload and quality of work life of nurses taking care of patients with COVID-19

- Hassan Babamohamadi 1 , 2 ,

- Hossein Davari 1 , 2 ,

- Abbas-Ali Safari 3 ,

- Seifollah Alaei 1 , 2 &

- Sajjad Rahimi Pordanjani 4 , 5

BMC Nursing volume 22 , Article number: 234 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5272 Accesses

6 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 epidemic has brought significant changes and complexities to nurses’ working conditions. Given the crucial role of health workers, particularly nurses, in providing healthcare services, it is essential to determine the nurses’ workload, and its association with the quality of work life (QWL) during COVID-19 epidemic, and to explain the factors predicting their QWL.

A total of 250 nurses, who provided care for patients with COVID-19 in Imam Hossein Hospital of Shahrud, and met the inclusion criteria, were considered the samples in the present cross-sectional study in 2021–2022. Data were collected using the demographic questionnaire, NASA Task Load Index (TLX), and Walton’s QWL questionnaire, which were analyzed using SPSS26 and based on descriptive and inferential statistical tests. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant for all cases.

The nurses’ mean scores of workload and QWL were 71.43 ± 14.15 and 88.26 ± 19.5, respectively. Pearson’s correlation test indicated a significant inverse relationship between workload and QWL ( r=-0.308, p < 0.001 ). The subscales with the highest perceived workload scores were physical demand and mental demand (14.82 ± 8.27; 14.36 ± 7.43), respectively, and the subscale with the lowest workload was overall performance (6.63 ± 6.31). The subscales with the highest scores for QWL were safety and health in working conditions and opportunity to use and develop human capabilities (15.46 ± 4.11; 14.52 ± 3.84), respectively. The subscales with the lowest scores were adequate and fair compensation, work and total living space (7.46 ± 2.38; 6.52 ± 2.47), respectively. The number of children (β = 4.61, p = 0.004), work experience (β= -0.54, p = 0.019), effort (β = 0.37, p = 0.033) and total workload (β= -0.44, p = 0.000) explained 13% of the variance of nurses’ QWL.

Conclusions

The study’s findings showed that a higher workload score is associated with nurses’ lower perception of QWL. In order to improve the QWL of nurses, reducing the physical and mental demands of their workload and strengthening overall performance is necessary. Additionally, when promoting QWL, adequate and fair compensation and the work and living space should be considered. The researchers suggest that hospital managers should make more significant efforts to develop and promote the QWL of nurses. To achieve this goal, organizations can pay attention to other influential factors, primarily by increasing organizational support.

Peer Review reports

Nurses comprise the most significant healthcare and treatment systems workforce, serving as the care team’s backbone [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that there are approximately 27 million nurses worldwide, accounting for 50% of all health workers, and projects that this number will increase by 9 million by 2030 [ 2 ]. Nurses are responsible for most care and treatment measures and often must take on additional tasks beyond their primary roles [ 3 , 4 ]. Numerous studies have documented the high workload experienced by nurses [ 5 , 6 ]. Furthermore, nurses face various stressors, including unhealthy work environments, continuous fatigue, challenging workplace relationships, occupational hazards, and demanding workloads that can negatively impact their professional performance [ 7 ]. Over the past few decades, research has highlighted the stressful and demanding nature of nursing, characterized by its specialization, complexity, and the need to manage emergencies [ 8 ]. Considering the interconnectedness between caregivers and care, it is essential to prioritize the quality of care and the satisfaction of the care providers [ 9 ].

Nurses are one of the most crucial pillars of healthcare organizations in various situations, including the COVID-19 pandemic [ 10 ]. Although the severity of COVID-19 is gradually decreasing, nurses have been providing care to patients in various sectors of hospitals, including emergency departments, intensive care units, and wards, for nearly three years. One study has even suggested that 80% of the workload related to patient care and treatment in hospitals falls on the shoulders of nurses [ 11 ]. Workload refers to the total work done by an individual or team within a specific period. Although the workload is a concept that refers to the number of primary tasks assigned, it can threaten the physical and psychological safety of nurses and reduce job satisfaction while increasing job burnout [ 12 ]. Trait anxiety, psychological health, and social isolation are the primary factors affecting Turkish nurses’ quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 13 ]. Therefore, paying close attention to the factors influencing nurses’ performance and workplace, especially in critical situations, is crucial.

There are many consequences and preoccupations brought about by COVID-19, such as the severity of the disease, its unpredictability, and the lack of knowledge about the timing of the disease’s outbreak [ 14 ]. Fear and anxiety about possible infection with COVID-19 are destructive, as they can cause stress and psychological abnormalities in individuals [ 15 ]. The nature of this disease increases severe stress reactions, such as fatigue, anxiety, and depression in nurses [ 16 ]. A study indicated that among healthcare workers, nurses experienced higher anxiety about infection with COVID-19 for themselves and their families [ 9 ]. Evidence and data indicate that nursing care for COVID-19 patients is challenging and exhausting, and a high volume of services and work shift restrictions make nurses exhausted. Nurses participating in a study mentioned that patients’ higher care needs and fewer nursing personnel increased the nurses’ workload and fatigue [ 17 ]. The COVID-19 epidemic and changes in work status have significantly impacted nurses’ lives personally and professionally. In today’s interconnected world, the integration of personal and work life has resulted in work life overshadowing personal life, leading to the emergence of the quality of work life (QWL) [ 18 ]. QWL refers to the satisfaction of workers with their personal and work-related needs within their job roles [ 19 ]. Unlike in the past, where the focus was primarily on personal life, improving work life has now become a crucial social issue worldwide, with organizations and employees striving to achieve this goal [ 20 ].

QWL encompasses workplace processes, strategies, and conditions that contribute to employees’ overall job satisfaction, which, in turn, relies on favorable work conditions and organizational efficiency [ 21 ]. In order to enhance and optimize organizational efficiency, prioritizing employees’ capabilities, physical and mental health, and performance is essential [ 22 ]. The QWL and practical job performance have been recognized as critical success factors for any organization, including healthcare institutions like hospitals since 1973 [ 23 ].

By serving as an index, QWL offers valuable insights to managers regarding employees’ primary concerns, fostering a sense of ownership, self-management, security, and responsibility, thereby increasing employee productivity [ 24 ]. QWL has a direct relationship with job satisfaction but an inverse relationship with job turnover [ 25 ]. Therefore, QWL is essential in improving organizational commitment among healthcare workers [ 26 ], nurses’ performance, and care performance and outcomes [ 4 ].

Health managers, especially hospital managers, must take appropriate measures to make necessary changes in the model and contents of academic education in response to experiences related to recent events or other care conditions, such as natural crises [ 27 ], as well as management considerations. Undoubtedly, evaluating the workload and QWL of nurses is essential, despite the effective measures taken by health managers, particularly hospital managers, to recruit a new workforce, balance nurse workload, and provide suitable facilities and incentives.

The present study aimed to answer the question, “What is the relationship between the workload and the QWL of nurses providing care for patients with diseases?” Given the heterogeneous findings about workload [ 28 ] and the nurses’ QWL before the COVID-19 pandemic [ 29 ], the present study was thus conducted to determine: (1) the relationship between workload and the QWL of nurses caring for COVID-19 patients admitted to Imam Hossein Hospital, affiliated with Shahrud University of Medical Sciences, and (2) to elucidate the factors predicting their QWL.

Design, setting, and participants

The present cross-sectional study was conducted from October 10, 2021, to January 15, 2022. The city of Shahrud has three hospitals, two of which are affiliated with the university of medical sciences. Among these three hospitals, only one, Imam Hossein Hospital, serves as the designated referral center for COVID-19 patients. It has dedicated emergency units, infectious disease wards, and ICUs for their admission. In the sample, we included 250 nurses caring for COVID-19 patients admitted to Imam Hossein Hospital of Shahrud. We applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria using census sampling to select all nurses for the study.

The inclusion criteria were having at least three months of work experience caring for COVID-19 patients and expressing willingness and consent to participate in the study. We considered returning incomplete questionnaires and unwillingness to participate in research as the exclusion criteria.

Ethical considerations

Data collection began after the hospital management approved the project and obtained ethical approval (Approval: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1400.282). During the rest time of these nurses in a work shifts, the researcher explained the research objective to them and assured them that the research findings would be used only for research purposes and would be anonymous and confidential. The participating nurses completed informed consent forms to participate in the study and returned the questionnaires afterward.

Instruments and data collection

We collected data using the researcher-made demographic information questionnaire, which included questions about age, gender, marital status, clinical work experience, work shifts, and work experience in the COVID-19 unit. The NASA Task Load Index (TLX) questionnaire and Walton’s Quality of Work Life (QWL) questionnaire were employed.

The NASA Task Load Index questionnaire consists of two sections. The first section classifies the total activity workload into six subscales: Mental demand, Physical demand, Temporal demand, Overall performance, Effort, and Frustration. Each subscale ranks on a 100-point scale with 5-point steps. Individuals establish personal weights based on their perceived importance through pairwise comparisons. They then multiply these weights by the scale score of each dimension, divide them by 15, and obtain a workload score ranging from 0 to 100, representing the total workload index. Mean scores below 50 are acceptable, while scores above 50 indicate a high workload [ 30 ]. The reliability coefficient of the NASA-TLX scale has been reported as 0.746 using the test-retest method [ 31 ]. Additionally, the questionnaire’s reliability was confirmed among 30 nurses, yielding a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.847 [ 32 ]. In this study, we confirmed the reliability of the NASA-TLX through a pilot study involving ten nurses, resulting in a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

Walton’s QWL questionnaire (1973) encompasses components such as Adequate and fair compensations, Safety and health in working conditions, Work and total living space, Constitutionalism in the organization of work, Career opportunities and job security, Opportunity to use and develop human capabilities, Social relevance of work life, and Social integration in the organization [ 33 ]. The questionnaire includes 35 closed-ended questions, categorized on a 5-point Likert scale. The total score of each field and all questions determines the QWL index, which ranges from a minimum of 35 to a maximum of 175. Higher scores indicate better QWL. Previous studies among Iranian hospital workers and nurses have investigated the reliability and validity of this tool, confirming its validity and reporting a reliability of 0.94 using the Cronbach’s alpha test [ 34 ]. In our pilot study involving ten nurses, we confirmed the reliability of the QWL questionnaire, which yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80.

Data analysis

We performed statistical analysis using SPSS-26 software at a significance level of 0.05. We used descriptive and inferential statistics to analyze the data. We described, classified, and compared the research data using relative and absolute frequency tables. Before analyzing the data, we used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to determine the normal distribution. We analyzed the collected data using an independent t-test, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Additionally, we utilized backward multiple linear regression analysis to examine the prediction role of workload subscales and demographic characteristics in nurses’ QWL during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

The nurses’ mean age was 32.92 years, 73.6% were females, and 69.6% were married. The nurses’ mean work experience was 8.75 years, and 15 months were related to working in COVID-19 care units. Furthermore, 92% of nurses were working in rotational shifts (Table 1 ).

The mean score of workload, Walton’s quality of work life, and their subscales

Based on the results, the participants’ mean workload and QWL were 71.43 ± 14.15 and 88.26 ± 19.50, respectively. The maximum perceived workload belonged to physical demand (14.82 ± 8.27) and mental demand (14.36 ± 7.43), and the minimum workload belonged to overall performance (6.63 ± 6.31). The maximum score of QWL subscales belonged to safety and health in working conditions (15.46 ± 4.11), and the minimum score was related to the work and total living space (6.52 ± 2.47) (Table 2 ).

Relationship between workload, the quality of work life, and demographic variables in nurses

The study of the relationship between workload and its subscales with demographic variables indicated that workload had a positive and significant correlation only with age (` r = 0.140, p = 0.027). Even though there was no difference between the workload of single and married nurses, there was a negative and significant relationship between marital status and mental demand ( r =-0.126, p = 0.046). Furthermore, there was a significant positive relationship between the number of children and temporal demand ( r = 0.155, p = 0.014). There was no statistically significant relationship between work experience and workload ( r = 0.096, p = 0.129) and no significant relationship between workload and work experience in the COVID-19 department ( r = 0.036, p = 0.568). However, a statistically significant relationship existed between work experience and temporal demand ( r = 0.179, p = 0.004).

The study of the relationship between QWL and its subscales with demographic variables indicated no statistical association between age and QWL ( p = 0.057). There was a strong positive association between age and fair compensations for the subscales of QWL ( r = 0.151, p = 0.014). Pearson’s test showed no significant relationship between marital status and the number of children with a nurse’s QWL ( p = 0.618 and p = 0.311, respectively). Regarding the subscales of the QWL, there was a significant positive correlation between fair compensations and the number of children ( r = 0.155, p = 0.014).

Furthermore, there was no significant statistical relationship between the QWL, work experience ( r =-0.078, p = 0.222), and work experience in the COVID-19 unit ( r = 0.006, p = 0.923), but there was a negative and significant relationship between fair compensations subscale and work experience ( r =-0.159, p = 0.016).

Relationship between workload, the quality of work life, and work shift in nurses

Even though the workload of night shifts was less than in the morning and afternoon, the results of the one-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA) indicated no statistically significant relationship between workload and shift work, and it was the same for the relationship between each workload subscale and work shift. The frustration score on the night shift was close to the significance level ( p = 0.059). Also, the results of One-way ANOVA indicated no significant difference between the nurses’ QWL in different shifts. There was no significant relationship between work shifts and QWL ( p = 0.933), but the nurses’ QWL was more appropriate in night shifts (Table 3 ).

The relationship between QWL and its subscales with the workload in nurses

Based on the results, there was a significant negative correlation of 0.308 between workload and QWL in nurses ( r =-0.308, p < 0.001); in other words, a higher workload decreased the QWL. Furthermore, the workload had a significant inverse relationship with all subscales of the QWL (Table 4 ).

The multivariate linear regression analysis of the effect of the demographic characteristics and workload subscales on the QWL`

A multiple linear regression model was used to investigate the predictor variables (the demographic characteristics and workload subscales) that had a significant effect on global QWL based on the backward model. To evaluate the extent of the correlation of QWL score with each predictive variable, we used backward linear regression and the ‘margins’ post- estimation command to obtain estimated marginal means and associated confidence intervals. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test predictive variables for multicollinearity and the residuals for normal distribution. The results of the regression indicated the four predictors explained 13% of the variance ( R 2 = 0.14, F (4,244) = 10.28, p < 0.001). It was found that number of children (β = 4.61, p = 0.004), work experience (β= − 0.54, p = 0.019), Effort (β = 0.37, p = 0.033), and total workload (β = −0.44, p = 0.000) significantly predicted nurses’ QWL (Table 5 ).

The current study’s findings, which sought to ascertain the relationship between nurses’ workload and the quality of their working lives while caring for COVID-19 patients, showed that the average workload for the nurses was 71.43 ± 14.15. Consistent with the results of the present study, Pourteimour et al. (2021) reported the mean workload of nurses who took care of patients with COVID-19 in Urmia and Hamedan hospitals (67.30 ± 14.53) [ 35 ]. The results of studies by Shoja et al. (2020) and Judek et al. (2018) also confirmed this finding [ 36 , 37 ]. Based on findings of research by Bakhshi et al. in Kermanshah hospitals (2017), the mean ± standard deviation of workload score was 69.73 ± 15.26 [ 5 ], and it was 59.95 ± 16.41in a study by Jarahian et al. [ 6 ], and it was partially less than the present study. In similar studies, nurses’ mean workload was moderate to low in non-critical situations [ 38 , 39 , 40 ]. Malekpour et al. (2014) reported that nurses were responsible for 80% of tasks in health and medical centers and generally had a heavy workload [ 3 ]. The COVID-19 epidemic has significantly increased the workload for nurses, as indicated by the results. According to the findings, mental demand was identified as the dimension with the highest perceived workload, while overall performance had the lowest workload, aligning with a study by Gharagozlou et al. (2020) [ 41 ]. Shoja et al. (2020) examined the subscales of the workload questionnaire and observed increased scores for mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, and frustration, leading them to conclude that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected staff workload and mental health [ 36 ]. A study conducted by Bakhshi et al. (2017) found that mental workload made the highest contribution, while the feeling of frustration had the lowest contribution [ 5 ]. Rafiee et al. (2015) conducted a study to measure the mental workload of nurses in the emergency department of a hospital and reported that the dimension of overall performance had the lowest score, while frustration had the highest score [ 42 ].

Furthermore, the nurses caring for COVID-19 patients endure high physical and mental demands. Based on the results of some studies conducted before the prevalence of COVID-19, nurses who took care of COVID-19 patients felt more frustrated and discouraged but considered their activities more effective. High and frequent workloads are two key factors leading to exhaustion and burnout [ 12 ], resulting in lower overall performance, memory, and thinking process, irritability, annoyance, and reduced learning [ 43 ]. The findings of Mohamadzadeh Tabrizis’ study show the negative impact of caring for COVID-19 patients on nurses’ quality of life [ 44 ].

This study showed that other than age, there was no link between workload and demographic factors like sex, marital status, number of children, working shifts, and years of work experience. There was a relationship between marital status, mental demand, the number of children, and temporal demand. There was no correlation between workload and work experience in the COVID-19 unit and shift work. Jarahian et al. (2018) found a correlation between workload, work experience, and the number of children. The study indicated that individuals with lower work experience and no children had lower mental workloads [ 6 ].

The findings of a study on determinants of workload indicated a significant relationship between physical workload with work experience, age, work pattern, number of shifts, and type of employment, and between temporal demand with body mass index (BMI), work experience, and type of employment [ 5 ]. Based on research by Shoja et al., the type of job, work shift, education level, and exposure to COVID-19 affected the workload score [ 36 ]. Older nurses, married individuals, and those with children might experience a higher workload due to increased work shifts and forced overtime. The higher workload, particularly regarding temporal demand, is especially evident. Establishing a balance between work life and personal/family demands is vital since research indicates that personal and professional lives often intertwine [ 4 ]. Nurses, regardless of gender or age, must work various shifts and wear protective masks in hospitals during the COVID-19 outbreak. Huang et al. (2018) confirm that nurses face high responsibility, heavy workload, intense work pressure, and the need to work in rotational shifts due to the unique nature of their profession [ 45 ].

Based on the results, the mean QWL of the nurses was 88.26 ± 19.50. In line with the findings of the present study, Nikeghbal et al. reported that the QWL of nurses who took care of patients with COVID-19 was 92.57 with a standard deviation of 13.2, which was better than the non-COVID-19 caregivers (79.43). A significant association between the two groups was revealed by the comparison ( p = 0.001) [ 46 ]. The results of Mohammadi’s study in Iran [ 29 ], and most studies in the world, show that nursing QWL is mainly at a moderate level and requires improvement interventions [ 40 , 42 , 47 ]. Some studies show an increase in depression, anxiety [ 48 ], stress, and burnout [ 49 , 50 ] among nurses during the pandemic of Coronavirus Disease.

Based on the results, the highest score of subscales belonged to safety and health in working conditions, while the lowest score belonged to work and total living space. Like Aminizadeh’s finding in pre-hospital staffs, Opportunity to use and develop human capabilities had a significant role in nurses’ QWL [ 26 ]. According to research on the relationship between job burnout, performance, and QWL, the constitutionalism in how work is organized contributed the most to the QWL score, while the social significance of work life contributed the least [ 51 ].

In a study on the relationship between the components of the QWL and job satisfaction of midwives, the results indicated that providing career opportunities and job security had the most significant contribution, and social relevance of work life in the organization had the minor contribution to the QWL in the midwives [ 52 ].

Falahi Khoshknab’s study before the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that 21% of nurses described their quality of work life (QWL) as moderate, while 67% described it as good, and 11% of nurses were delighted with their QWL [ 53 ]. In a study by Faraji et al. conducted prior to the prevalence of COVID-19, 61% of nurses had a low QWL, and even 39.7% of them wanted to leave their jobs [ 54 ]. In line with these studies, the current study, as well as Jafari’s study [ 48 ], suggests that nurses must receive adequate support to overcome workplace stressors. The findings of Shirali’s study showed job stress and low resilience as threatening factors in nurses during the care of COVID-19 patients [ 55 ]. Therefore, support for nurses should focus on both individual and organizational aspects.

Nurses’ workload has significantly increased, yet their work-life quality remains moderate. Various factors contribute to this category, and we will address some below. The present study identified a significant relationship among age, number of children, work experience, and specific aspects of QWL. Previous studies, such as those conducted by Gharagozlou et al. and Shafipour et al., found no significant relationship between QWL and demographic variables like age, gender, and marital status [ 41 , 56 ]. Dehghannayieri et al. [ 57 ] and Dargahi et al. [ 58 ] also found no significant relationship between marital status and QWL, but Khaghanizadeh [ 59 ] and Falahi Khoshknab [ 53 ] reported a significant relationship. Mohammadi et al. (2017) reported a significant correlation between the QWL and employment status, shift work, hospital, and satisfaction with the field of study ( p < 0.001) [ 29 ]. According to Gharagozlou’s study, there was no significant relationship between nurses’ QWL with the number of shifts and the number of patients in each shift, but there was a significant relationship between the QWL and overtime hours among the nurses [ 41 ]. In a study by Shafipour et al., there were significant relationships between the QWL, overtime hours, number of night shifts per month, and income level, but there was no significant relationship with the job unit [ 56 ]. A study indicated that working on the night shift negatively influences nurses’ QWL [ 60 ]. Researchers considered possible reasons for contradictions and differences in the types of sectors based on the characteristics of the participants and the study time (before and during the pandemic) in the study. The present study reported no difference among different shifts regarding QWL, but the night shift was associated with a better QWL. Researchers believe this was because most diagnostic and therapeutic procedures were carried out during the morning shift, and systemic supervision and nurses’ freedom of action were reduced during the night shift. However, the difference was not statistically significant.

Furthermore, there was a relationship between work experience and adequate and fair compensation, indicating the financial concerns of married nurses with higher experience and more children. In the present study, the Opportunity to use and develop human capabilities and safety and health in working conditions had the most significant contribution, adequate and fair compensations, and work and total living space had the minor contribution. Consistent with this finding, Jafari et al. reported that the highest contribution to the QWL was the development of human capabilities, career opportunities, and job security, but the lowest was fair compensations [ 34 ]. In a study by Dargahi et al. [ 58 ] and research in Ethiopia [ 4 ], there was a significant relationship between the monthly income level and the QWL. The QWL increased with higher total compensation. A study in Canada indicated that a higher level of income increased the QWL [ 61 ], but in a study by Nikeghbal et al., there was a significant relationship between the QWL index (adequate and fair compensations) and monthly income only in nurses who took care of COVID-19 patients [ 46 ].

The results of this study indicate a significant inverse relationship between nurses’ workload and quality of work life (QWL). In other words, a higher workload leads to a decrease in QWL. The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed difficult circumstances, and due to the intensity of the workload, nurses have had to put their own lives and the lives of their loved ones at risk while treating COVID-19 patients. The risk of infection and death from COVID-19 has caused significant psychosocial stress for nurses and other healthcare professionals [ 62 ]. In similar studies, Lai et al. [ 63 ] and Gharagozlou et al. [ 41 ] investigated the QWL and workload status using the same tools as in the present study and reported significant relationships between different dimensions of workload and QWL.

Numerous studies have indicated that a high workload endangers the quality and safety of patient care, increases errors, and ultimately prolongs hospitalization time. This situation affects the relationship between nurses, physicians, and patients [ 64 ]. In a study by Ardesatni Rostami et al. (2019) focusing on nurses in ICUs, a negative correlation was found between workload and job performance. According to the study, 75% of nurses rated their performance moderate [ 65 ]. These studies were conducted primarily before the COVID-19 pandemic, but nurses have always had to work long hours to manage their workload. Although the pandemic has further increased their workload, it has not significantly impacted the quality of their work life. Similar to the pre-COVID-19 era, the quality of work life remains predominantly dependent on organizational factors such as support and financial assistance.

The present findings indicate that an increase in the number of children and effort contributes to a high level of QWL, while work experience and total workload decrease the QWL of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consistent with these findings, Navales et al. (2021) reported a relationship between individual factors, such as older nurses, females, bachelor graduates with more dependents, more children, and job positions with more extended work experience, and nurses’ QWL in Indonesia [ 66 ]. Woon et al. (2021) found that social support from friends and significant others (such as children and spouse) predicted higher QWL. Despite the COVID-19 restrictions, encouragement regarding family and children appears to have positively influenced the quality of nurses’ work life [ 67 ].

Contrary to the findings of Gharagozlou’s study, nurses who encounter COVID-19 patients require additional effort, potentially resulting in an enhanced QWL [ 41 ]. Hence, despite the numerous adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on nurses, it has also presented opportunities for provisional, organizational, and individual improvements in their quality of life.

The mental burden experienced by nurses in these job groups is significant. Several factors contribute to the creation and escalation of this burden, including consistent and uninterrupted work, work duration, job requirements (such as concentration, accuracy, and effort), physical stress-induced fatigue, age, work experience, environmental factors (such as sound and vibration), equipment usage, individual feedback on work and interpersonal interactions, overtime, and ergonomic working conditions [ 46 ]. Thus, these factors are among those that contribute to the increased workload of nurses. Furthermore, as these employees operate within a consistent and stable work environment characterized by the nature of the job and working conditions, they often have longer working hours. Consequently, this leads to physical and mental fatigue, exhaustion, burnout and ultimately diminishing their QWL. In line with the negative effect of workload on QWL, Nikeghbal et al.‘s study supported that an increased workload was associated with a decreased QWL [ 46 ].

Limitations of the study

Since we conducted this research solely on the Shahrud University of Medical Sciences nursing staff, it is essential to exercise caution when generalizing the results to other settings. We recommend conducting multicenter studies with larger sample sizes. We maintained a continuous presence in different units and shifts to address the main barriers for nurses to participate in the study, namely the lack of free time and high workload. We also followed up to increase participation in the study. Another limitation was that nurses were less focused on answering the questionnaires because they had to complete them during work hours. Some nurses hesitated to complete the questionnaires due to insufficient information from prior research. We assured the participants that they would have access to the research results. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the participants’ mental state during the questionnaire completion could also influence the research results.

Recommendations for future research

We recommend conducting multicenter studies with larger samples in settings with different cultures to identify other unrecognized effective factors in relation to workload and QWL. It is essential to carry out interventional studies, mainly focusing on nurses’ psychological empowerment and organizational support. Additionally, qualitative research is required to explain the process of QWL development and comprehend nurses’ lived experiences.

Clinical implications for nursing managers and policymakers

In order to achieve a better quality of work life (QWL), nursing managers can take active steps to improve nurses’ work conditions. These steps include reducing nurses’ workload, creating a respectful working atmosphere, considering their work experience, work shifts, and age, and ensuring adequate and fair pay. Additionally, effective measures should be taken to recruit a new workforce, balance nurses’ workload, and provide suitable facilities and incentives.

The high workload was a significant stressor for hospital staff and nurses. The nurses’ workload increased, leading to increased stress and decreased productivity, ultimately affecting their quality of life. Compared to studies before the outbreak of COVID-19, there was a partial increase in nurses’ workload, but there was no noticeable change in the quality of their work life, which remained at a moderate level. Therefore, acquiring knowledge about the influential factors for positive quality of work life (QWL) development among nurses is crucial to improve their QWL. Developing QWL in nurses can increase their loyalty to the profession and promote the quality of care and patient satisfaction while decreasing nurses’ exhaustion and burnout.

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting the study findings are within the manuscript. Additional detailed information and raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

World Health Organization

Quality of work life

Gerami Nejad N, Hosseini M, Mousavi Mirzaei S, Ghorbani Moghaddam Z. Association between Resilience and Professional Quality of Life among Nurses Working in Intensive Care Units. IJN. 2019;31(116):49–60.

Article Google Scholar

World Health Organization. State of the world’s nursing 2020: investing in education, jobs and leadership. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279 .

Malekpour F, Mohammadian Y, Malekpour AR, Mohammadpour Y, Sheikh Ahmadi A, Shakarami A. Assessment of mental workload in nursing using NASA-TLX. Nurs Midwifery J. 2014;11(11):892–99.

Google Scholar

Mosisa G, Abadiga M, Oluma A, Wakuma B. Quality of work-life and associated factors among nurses working in wollega zones public hospitals, West Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2022;17:100466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2022.100466 .

Bakhshi E, Mazlomi A, Hoseini SM. Mental workload and its determinants among nurses in one hospital in Kermanshah City, Iran. J Occup Hygiene Eng (JOHE). 2017;3(4):53–60.

Jarahian Mohammady M, Sedighi A, Khaleghdoost T, Kazem Nejad E, Javadi-Pashaki N. Relationship between Nurses’ subjective workload and occupational cognitive failure in Intensive Care Units. J Crit Care Nurs (jccnursing). 2018;11(4):53–61.

Abdi F, Khaghanizade M, Sirati M. Determination of the amount burnout in nursing staff. J Behav Sci. 2008;2(1):51–9.

Chou L, Li C, Hu SC. Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004185. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004185 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nemati M, Ebrahimi B, Nemati F. Assessment of iranian nurses’ knowledge and anxiety toward COVID-19 during the current outbreak in Iran. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2020;15(COVID–19):e102848. https://doi.org/10.5812/archcid.102848 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Jamebozorgi M, Jafari H, Sadeghi R, Sheikhbardsiri H, Kargar M, Gharaghani MA. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among nurses during the coronavirus disease 2019: a comparison between nurses in the frontline and the second line of care delivery. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2021;10(3):188–93. https://doi.org/10.4103/nms.nms_103_20 .

Razu SR, Yasmin T, Arif TB, Islam M, Islam SMS, Gesesew HA, Ward P. Challenges faced by healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative inquiry from Bangladesh. Front public health. 2021;9:647315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.647315 .

Jamebozorgi MH, Karamoozian A, Bardsiri TI, Sheikhbardsiri H. Nurses burnout, resilience, and its association with socio-demographic factors during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2022;12:803506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.803506 .

Potas N, Koçtürk N, Toygar SA. Anxiety effects on quality of life during the COVID-19 outbreak: a parallel-serial mediation model among nurses in Turkey. Work. 2021;69(1):37–45. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-205050 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bo HX, Li W, Yang Y, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Cheung T, Wu X, Xiang YT. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitude toward crisis mental health services among clinically stable patients with COVID-19 in China. Psychol Med. 2021;51(6):1052–3. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720000999 .

Poursadeghiyan M, Abbasi M, Mehri A, Hami M, Raei M, Ebrahimi MH. Relationship between job stress and anxiety, depression and job satisfaction in nurses in Iran. The Soc Sci. 2016;11(9):2349–55.

Rahimian Boogar E, Nouri A, Oreizy H, Molavi H, Foroughi Mobarake A. Relationship between adult attachment styles with job satisfaction and job stress in nurses. Iran J psychiatry Clin Psychol (IJPCP). 2007;13(2):148–57.

Galehdar N, Toulabi T, Kamran A, Heydari H. Exploring nurses’ perception of taking care of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a qualitative study. Nurs Open. 2020;11(1):171–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.616 .

Shiri A, Yari AB, Dehghani M. A study of relation between Job Rotation and Staff’s Organizational Commitment (A Case Study at Ilam University). Trends Adv Sci Engin. 2012;5(1):82–6.

Yunus YM, Idris K, Rahman AA, Lai HI. The role of quality of nursing work life and turnover intention in primary healthcare services among registered nurses in Selangor. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci. 2017;7(6):1201–13. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i6/3353 .

Abrishamirad S, Kordi M, Abbasi T. A comparison of Employee’s Engagement Models with emphasis on Human Resources in Iranian Organizations. Iran J Comp Educ. 2021;4(3):1329–48. https://doi.org/10.22034/IJCE.2021.256255.1236 .

Ruževičius J. Quality of Life and of Working Life: Conceptions and research. 17th Toulon-Verona International Conference. Liverpool John Moores University. Excellence in Services. Liverpool (England). Conference Proceedings ISBN 9788890432743, August 28-29, 2014: 317-334.

Hosseini M, Sedghi Goyaghaj N, Alamadarloo A, Farzadmehr M, Mousavi A. The relationship between job burnout and job performance of clinical nurses in Shiraz Shahid Rajaei hospital (thruma) in 2016. J Clin Nurs Midwifery. 2017;6(2):59–68.

Kuzey C. Impact of Health Care Employees’ job satisfaction on Organizational Performance Support Vector Machine Approach (January 19, 2018). J Econ Financial Anal. 2018;2(1):45–68.

Abadi F, Abadi F, Nouhi E. Survey factors affecting of quality of work life in the clinical nurses. Nurs Midwifery J. 2019;16(11):832–40.

Salahat MF, Al-Hamdan ZM. Quality of nursing work life, job satisfaction, and intent to leave among jordanian nurses: a descriptive study. Heliyon. 2022;8(7):e09838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09838 .

Aminizadeh M, Saberinia A, Salahi S, Sarhadi M, Jangipour Afshar P, Sheikhbardsiri H. Quality of working life and organizational commitment of iranian pre-hospital paramedic employees during the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak. Int J Healthc Manag. 2022;15(1):36–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2020.1836734 .

Mehryar HR, Garkaz O, Sepandi M, Taghdir M, Paryab S. How to manage emergency response of health teams to natural disasters in Iran: a systematic review. Arch Trauma Res. 2021;10(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/atr.atr_20_20 .

Stavropoulou A, Rovithis M, Sigala E, Moudatsou M, Fasoi G, Papageorgiou D, Koukouli S. Exploring nurses’ working experiences during the First Wave of COVID-19 outbreak. Healthc (Basel). 2022;10(8):1406. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10081406 .

Mohammadi M, Mozaffari N, Dadkhah B, Etebari Asl F, Etebari Asl M. Study of work-related quality of life of nurses in Ardabil Province Hospitals. J Health Care (JHC). 2017;19(3):108–16.

Mohamed R, Raman M, Anderson J, McLaughlin K, Rostom A, Coderre S. Validation of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task load index as a tool to evaluate the learning curve for endoscopy training. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(3):155–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/892476 .

Mohammadi M, Nasl Seraji J, Zeraati H. Developing and assessing the validity and reliability of a questionnaire to assess the mental workload among ICUs Nurses in one of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences hospitals, Tehran, Iran. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2013;11(2):87–96.

Safari S, Mohammadi-Bolbanabad H, Kazemi M. Evaluation Mental Work load in nursing critical care unit with National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task load index (NASA-TLX). J Health Syst Res. 2013;9(6):613–9.

Walton RE. Quality of working life: what is it? Sloan Management Review. 1973;15(1):11–21.

Jafari M, Habibi Houshmand B, Maher A. Relationship of occupational stress and quality of work life with turnover intention among the Nurses of Public and private hospitals in selected cities of Guilan Province, Iran, in 2016. J Health Res Commun. 2017;3(3):12–24.

Pourteimour S, Yaghmaei S, Babamohamadi H. The relationship between mental workload and job performance among iranian nurses providing care to COVID-19 patients: a cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(6):1723–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13305 .

Shoja E, Aghamohammadi V, Bazyar H, Moghaddam HR, Nasiri K, Dashti M, Choupani A, Garaee M, Aliasgharzadeh S, Asgari A. Covid-19 effects on the workload of iranian healthcare workers. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1636. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09743-w .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Judek C, Verhaegen F, Belo J, Verdel T. Crisis managers’ workload assessment during a simulated crisis situation. By Malizia A, D’Arienzo M, editors. Enhancing CBRNE Safety & Security: Proceedings of the SICC 2017Conference. Spinger Nature 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3/319-91791-7_37 .

Destiani W, Mediawati AS, Permana RH. The mental workload of nurses in the role of nursing care providers. J Nurs Care. 2020;3(1):11–8. https://doi.org/10.24198/jnc.v3il.22938 .

Mohammadi M, Mazloumi A, Kazemi Z, Zeraati H. Evaluation of Mental workload among ICU Ward’s nurses. Health Promot Perspect. 2016;5(4):280–7. https://doi.org/10.15171/hpp.2015.033 .

Asamani JA, Amertil NP, Chebere M. The influence of workload levels on performance in a rural hospital. Br J Healthc Manage. 2015;21(12):577–86. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2015.21.12.577 .

Gharagozlou F, karamimatin B, Kashefi H, Nikravesh Babaei D, Bakhtyarizadeh F, Rahimi S. The relationship between quality of working life of nurses in educational hospitals of Kermanshah with their perception and evaluation of workload in 2017. Iran Occup Health (ioh). 2020;17(1):25–36.

Rafiee N, Hajimaghsoudi M, Bahrami Ma GN, Mazrooei M. Evaluation nurses’ mental work load in Emergency Department: case study. Quart J Nurse Manag. 2015;3(4):43–50.

Sorić M, Golubić R, Milosević M, Juras K, Mustajbegović J. Shift work, quality of life and work ability among croatian hospital nurses. Coll Antropol. 2013;37(2):379–84. PMID: 23940978.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mohamadzadeh Tabrizi Z, Mohammadzadeh F, Davarinia Motlagh Quchan A, Bahri N. COVID-19 anxiety and quality of life among iranian nurses. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00800-2 .

Huang CLC, Wu MP, Ho CH, Wang JJ. Risks of treated anxiety, depression, and insomnia among nurses: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0204224. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204224 .

Nikeghbal K, Kouhnavard B, Shabani A, Zamanian Z. Covid-19 Effects on the Mental workload and quality of Work Life in iranian nurses. Ann Glob Health. 2021;87(1):79. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3386 .

Parra-Giordano D, Quijada Sánchez D, Grau Mascayano P, Pinto-Galleguillos D. Quality of Work Life and work process of assistance nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(11):6415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116415 .

Jafari H, Amiri Gharaghani M. Cultural challenges: the most important challenge of COVID-19 control policies in Iran. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2020;35(4):470–1. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X20000710 .

Jose S, Dhandapani M, Cyriac MC. Burnout and resilience among frontline nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in the emergency department of a tertiary care center, North India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24(11):1081–88. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23667 .

Kishi H, Watanabe K, Nakamura S, Taguchi H, Narimatsu H. Impact of nurses’ roles and burden on burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: Multicentre cross-sectional survey. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(6):1922–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13648 .

Bakhshi E, Gharagozlou F, Moradi A, Naderi MR. Quality of work life and its association with job burnout and job performance among iranian healthcare employees in Islamabad-e Gharb, 2016. J Occup Health Epidemiol. 2019;8(2):94–101.

Hadizadeh Talasaz Z, Nourani Saadoldin S, Shakeri MT. Relationship between components of quality of Work Life with Job satisfaction among midwives in mashhad, 2014. J Hayat. 2015;21(1):56–67.

Falahi Khoshknab M, Karimlou M, Rahgoy A, Fattah Moghaddam L. Quality of life and factors related to it among psychiatric nurses in the university teaching hospitals in Tehran. Hakim Res J. 2007;9(4):24–30.

Faraji O, Salehnejad G, Gahramani S, Valiee S. The relation between nurses’ quality of work life with intention to leave their job. Nurs Pract Today (NPT). 2017;4(2):103–11.

Shirali GA, Amiri A, Chanani KT, Silavi M, Mohipoor S, Rashnuodi P. Job stress and resilience in iranian nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case-control study. Work. 2021;70(4):1011–20. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-210476 .

Shafipour V, Momeni B, YazdaniCharati J, Esmaeili R. Quality of working life and its related factors in critical care unit nurses. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2016;26(142):117–26.

Dehghannyieri N, Salehi T, Asadinoghabi A. Assessing the quality of work life, productivity of nurses and their relationship. IJNR. 2008;3(9):8.

Dargahi H, Gharib M, Goodarzi M. Quality of work life in nursing employees of Tehran University of Medical Sciences Hospitals. J Hayat. 2007;13(2):13–21.

Khaghanizadeh M, Ebadi A, Cirati nair M, Rahmani M. The study of relationship between job stress and quality of work life of nurses in military hospitals. J Mil Med. 2008;10(3):175–84.

Ebatetou E, Atipo-Galloye P, Moukassa D. Shift work: impact on nurses’ Health and Quality Life in Pointe-Noire (Congo). Open J Epidemiol. 2021;11:16–30. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojepi.2021.111002 .

Sale JE, Smoke M. Measuring quality of work-life: a participatory approach in a canadian cancer center. J Cancer Educ. 2007;22(1):62–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03174378 .

Huang L, Lin G, Tang L, Yu L, Zhou Z. Special attention to nurses’ protection during the COVID-19 epidemic. Crit Care. 2020;24:120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2841-7 .

Lai SL, Chang J, Hsu LY. Does effect of workload on quality of work life vary with generations? Asia Pac Manage Rev. 2017;17(4):437–51. https://doi.org/10.6126/APMR.2012.17.4.06 .

Boonrod W. Quality of working life: perceptions of professional nurses at Phramongkutklao Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92(Suppl 1):S7-15 PMID: 21302412.

Ardesatni Rostami R, Ghasembaglu A, Bahadori M. Relationship between work load of nurses and their performance in the intensive care units of educational hospitals in Tehran. SJNMP. 2019;4(3):63–71.

Navales JV, Jallow AW, Lai CY, Liu CY, Chen SW. Relationship between quality of nursing work life and uniformed nurses’ attitudes and practices related to COVID-19 in the Philippines: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):9953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199953 .

Woon LS, Mansor NS, Mohamad MA, Teoh SH, Leong Bin Abdullah MFI. Quality of life and its predictive factors among healthcare workers after the end of a movement lockdown: the salient roles of COVID-19 stressors, psychological experience, and social support. Front Psychol. 2021;12:652326. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.652326 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We took the present manuscript from the nursing master’s thesis, which Semnan University of Medical Sciences approved and supported. We express our gratitude to the management and nursing staff of Shahrud Hospital for their cooperation in facilitating the data collection.

We conducted this study without financial support.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nursing Care Research Center, Education and Research Campus, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Po Box: 3513138111, 5 Kilometer of Damghan Road, Semnan, Iran

Hassan Babamohamadi, Hossein Davari & Seifollah Alaei

Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Student Research Committee, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Abbas-Ali Safari

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Sajjad Rahimi Pordanjani

Department of Community Medicine, School of Medicine, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SA, AS, and HB conceived and designed the study. AS and HD collected, inputted, and checked the data. SR analyzed the data. SA and HB draft the manuscript. HB and SA revised the manuscript, and SA submitted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Seifollah Alaei .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The researchers first considered respecting participants’ rights and protecting their health and rights under the guidance of the principles outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. This study strictly adheres to ethical principles. The Ethics Committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences approved the research (IR.SEMUMS.REC.1400.282). After obtaining permission from the hospital officials, the researchers initiated data collection. Since the current study was a cross-sectional study with the only risk of participants’ privacy, the researchers introduced themselves to the nurses when conducting the survey. They provided thorough explanations regarding the study objectives and methods, the confidentiality of the data, and the voluntary nature of participation. The nurses’ questions were also addressed, and written informed consent was obtained from them to participate in the study. The researchers distributed the questionnaires among the nurses and requested them to complete and return them in the presence of the researcher.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Babamohamadi, H., Davari, H., Safari, AA. et al. The association between workload and quality of work life of nurses taking care of patients with COVID-19. BMC Nurs 22 , 234 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01395-6

Download citation

Received : 09 March 2023

Accepted : 22 June 2023

Published : 07 July 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01395-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Quality of Work Life

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2020

Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review

- Chiara Dall’Ora 1 ,

- Jane Ball 2 ,

- Maria Reinius 2 &

- Peter Griffiths 1 , 2

Human Resources for Health volume 18 , Article number: 41 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

241k Accesses

290 Citations

321 Altmetric

Metrics details

Workforce studies often identify burnout as a nursing ‘outcome’. Yet, burnout itself—what constitutes it, what factors contribute to its development, and what the wider consequences are for individuals, organisations, or their patients—is rarely made explicit. We aimed to provide a comprehensive summary of research that examines theorised relationships between burnout and other variables, in order to determine what is known (and not known) about the causes and consequences of burnout in nursing, and how this relates to theories of burnout.

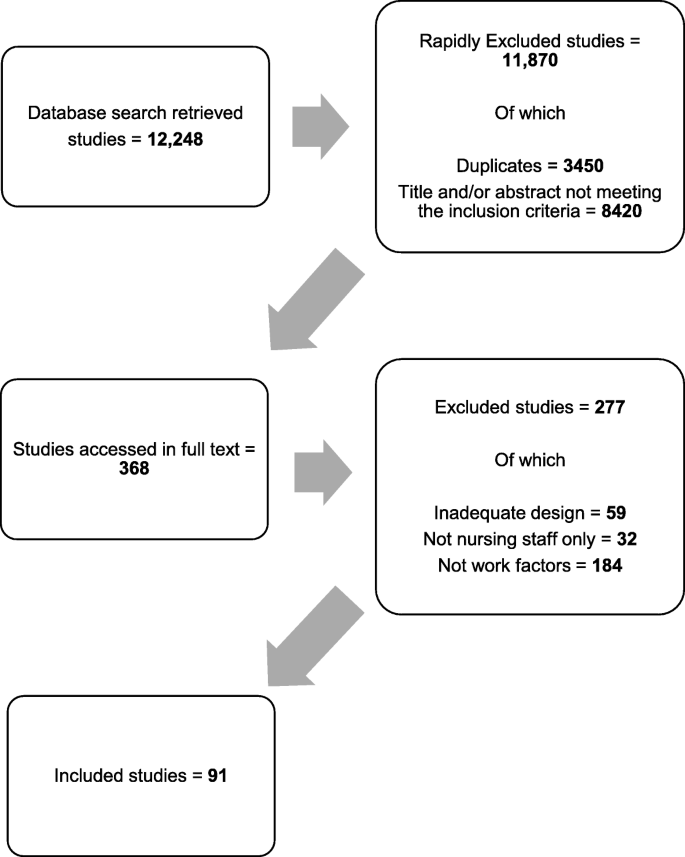

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. We included quantitative primary empirical studies (published in English) which examined associations between burnout and work-related factors in the nursing workforce.

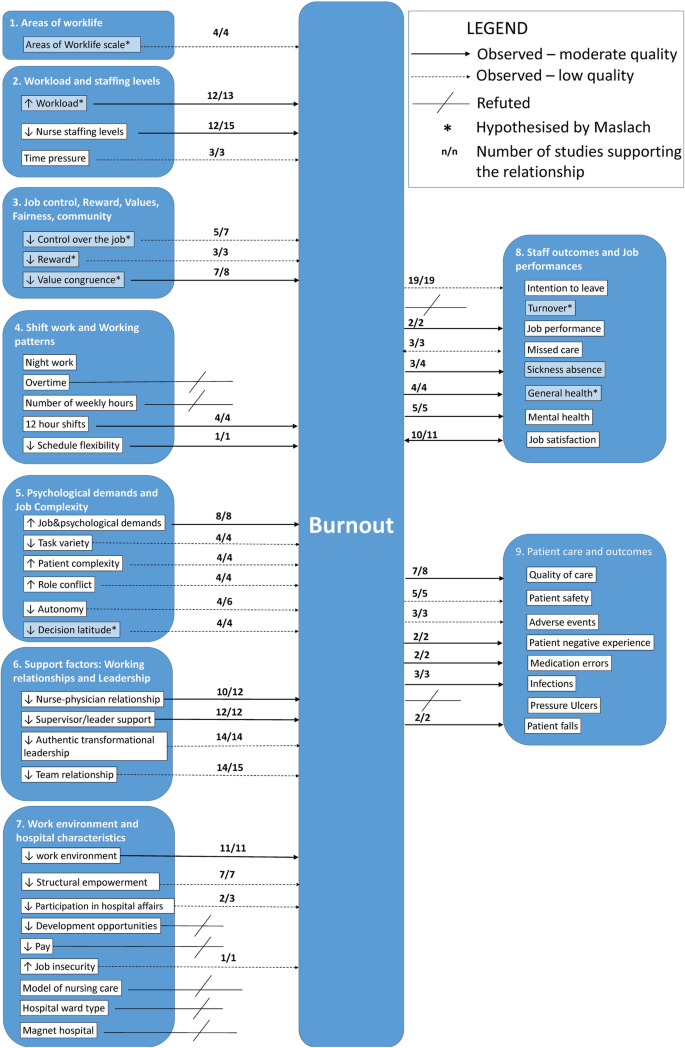

Ninety-one papers were identified. The majority ( n = 87) were cross-sectional studies; 39 studies used all three subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Scale to measure burnout. As hypothesised by Maslach, we identified high workload, value incongruence, low control over the job, low decision latitude, poor social climate/social support, and low rewards as predictors of burnout. Maslach suggested that turnover, sickness absence, and general health were effects of burnout; however, we identified relationships only with general health and sickness absence. Other factors that were classified as predictors of burnout in the nursing literature were low/inadequate nurse staffing levels, ≥ 12-h shifts, low schedule flexibility, time pressure, high job and psychological demands, low task variety, role conflict, low autonomy, negative nurse-physician relationship, poor supervisor/leader support, poor leadership, negative team relationship, and job insecurity. Among the outcomes of burnout, we found reduced job performance, poor quality of care, poor patient safety, adverse events, patient negative experience, medication errors, infections, patient falls, and intention to leave.

Conclusions

The patterns identified by these studies consistently show that adverse job characteristics—high workload, low staffing levels, long shifts, and low control—are associated with burnout in nursing. The potential consequences for staff and patients are severe. The literature on burnout in nursing partly supports Maslach’s theory, but some areas are insufficiently tested, in particular, the association between burnout and turnover, and relationships were found for some MBI dimensions only.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The past decades have seen a growing research and policy interest around how work organisation characteristics impact upon different outcomes in nursing. Several studies and reviews have considered relationships between work organisation variables and outcomes such as quality of care, patient safety, sickness absence, turnover, and job dissatisfaction [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Burnout is often identified as a nursing ‘outcome’ in workforce studies that seek to understand the effect of context and ‘inputs’ on outcomes in health care environments. Yet, burnout itself—what constitutes it, what factors contribute to its development, and what the wider consequences are for individuals, organisations, or their patients—is not always elucidated in these studies.

The term burnout was introduced by Freudenberger in 1974 when he observed a loss of motivation and reduced commitment among volunteers at a mental health clinic [ 5 ]. It was Maslach who developed a scale, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which internationally is the most widely used instrument to measure burnout [ 6 ]. According to Maslach’s conceptualisation, burnout is a response to excessive stress at work, which is characterised by feelings of being emotionally drained and lacking emotional resources—Emotional Exhaustion; by a negative and detached response to other people and loss of idealism—Depersonalisation; and by a decline in feelings of competence and performance at work—reduced Personal Accomplishment [ 7 ].

Maslach theorised that burnout is a state, which occurs as a result of a prolonged mismatch between a person and at least one of the following six dimensions of work [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]:

Workload: excessive workload and demands, so that recovery cannot be achieved.

Control: employees do not have sufficient control over the resources needed to complete or accomplish their job.

Reward: lack of adequate reward for the job done. Rewards can be financial, social, and intrinsic (i.e. the pride one may experience when doing a job).

Community: employees do not perceive a sense of positive connections with their colleagues and managers, leading to frustration and reducing the likelihood of social support.

Fairness: a person perceiving unfairness at the workplace, including inequity of workload and pay.

Values: employees feeling constrained by their job to act against their own values and their aspiration or when they experience conflicts between the organisation’s values.

Maslach theorised these six work characteristics as factors causing burnout and placed deterioration in employees’ health and job performance as outcomes arising from burnout [ 7 ].

Subsequent models of burnout differ from Maslach’s in one of two ways: they do not conceptualise burnout as an exclusively work-related syndrome; they view burnout as a process rather than a state [ 10 ].

The job resources-demands model [ 11 ] builds on the view of burnout as a work-based mismatch but differs from Maslach’s model in that it posits that burnout develops via two separate pathways: excessive job demands leading to exhaustion, and insufficient job resources leading to disengagement. Along with Maslach and Schaufeli, this model sees burnout as the negative pole of a continuum of employee’s well-being, with ‘work engagement’ as the positive pole [ 12 ].

Among those who regard burnout as a process, Cherniss used a longitudinal approach to investigate the development of burnout in early career human services workers. Burnout is presented as a process characterised by negative changes in attitudes and behaviours towards clients that occur over time, often associated with workers’ disillusionment about the ideals that had led them to the job [ 13 ]. Gustavsson and colleagues used this model in examining longitudinal data on early career nurses and found that exhaustion was a first phase in the burnout process, proceeding further only if nurses present dysfunctional coping (i.e. cynicism and disengagement) [ 14 ].

Shirom and colleagues suggested that burnout occurs when individuals exhaust their resources due to long-term exposures to emotionally demanding circumstances in both work and life settings, suggesting that burnout is not exclusively an occupational syndrome [ 15 , 16 ].

This review aims to identify research that has examined theorised relationships with burnout, in order to determine what is known (and not known) about the factors associated with burnout in nursing and to determine the extent to which studies have been underpinned by, and/or have supported or refuted, theories of burnout.

This was a theoretical review conducted according to the methodology outlined by Campbell et al. and Pare et al. [ 17 , 18 ]. Theoretical reviews draw on empirical studies to understand a concept from a theoretical perspective and highlight knowledge gaps. Theoretical reviews are systematic in terms of searching and inclusion/exclusion criteria and do not include a formal appraisal of quality. They have been previously used in nursing, but not focussing on burnout [ 19 ]. While no reporting guideline for theoretical reviews currently exists, the PRISMA-ScR was deemed to be suitable, with some modifications, to enhance the transparency of reporting for the purposes of this review. The checklist, which can be found as Additional file 2 , has been modified as follows:

Checklist title has been modified to indicate that the checklist has been adapted for theoretical reviews.

Introduction (item 3) has been modified to reflect that the review questions lend themselves to a theoretical review approach.

Selection of sources of evidence (item 9) has been modified to state the process for selecting sources of evidence in the theoretical review.

Limitations (item 20) has been amended to discuss the limitations of the theoretical review process.

Funding (item 22) has been amended to describe sources of funding and the role of funders in the theoretical review.

All changes from the original version have been highlighted.

Literature search

A systematic search of empirical studies examining burnout in nursing published in journal articles since 1975 was performed in May 2019, using MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. The main search terms were ‘burnout’ and ‘nursing’, using both free-search terms and indexed terms, synonyms, and abbreviations. The full search and the total number of papers identified are in Additional file 1 .

We included papers written in English that measured the association between burnout and work-related factors or outcomes in all types of nurses or nursing assistants working in a healthcare setting, including hospitals, care homes, primary care, the community, and ambulance services. Because there are different theories of burnout, we did not restrict the definition of burnout according to any specific theory. Burnout is a work-related phenomenon [ 8 ], so we excluded studies focussing exclusively on personal factors (e.g. gender, age). Our aim was to identify theorised relationships; therefore, we excluded studies which were only comparing the levels of burnout among different settings (e.g. in cancer services vs emergency departments). We excluded literature reviews, commentaries, and editorials.

Data extraction and quality appraisal