- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Evaluation Research: Definition, Methods and Examples

Content Index

- What is evaluation research

- Why do evaluation research

Quantitative methods

Qualitative methods.

- Process evaluation research question examples

- Outcome evaluation research question examples

What is evaluation research?

Evaluation research, also known as program evaluation, refers to research purpose instead of a specific method. Evaluation research is the systematic assessment of the worth or merit of time, money, effort and resources spent in order to achieve a goal.

Evaluation research is closely related to but slightly different from more conventional social research . It uses many of the same methods used in traditional social research, but because it takes place within an organizational context, it requires team skills, interpersonal skills, management skills, political smartness, and other research skills that social research does not need much. Evaluation research also requires one to keep in mind the interests of the stakeholders.

Evaluation research is a type of applied research, and so it is intended to have some real-world effect. Many methods like surveys and experiments can be used to do evaluation research. The process of evaluation research consisting of data analysis and reporting is a rigorous, systematic process that involves collecting data about organizations, processes, projects, services, and/or resources. Evaluation research enhances knowledge and decision-making, and leads to practical applications.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Why do evaluation research?

The common goal of most evaluations is to extract meaningful information from the audience and provide valuable insights to evaluators such as sponsors, donors, client-groups, administrators, staff, and other relevant constituencies. Most often, feedback is perceived value as useful if it helps in decision-making. However, evaluation research does not always create an impact that can be applied anywhere else, sometimes they fail to influence short-term decisions. It is also equally true that initially, it might seem to not have any influence, but can have a delayed impact when the situation is more favorable. In spite of this, there is a general agreement that the major goal of evaluation research should be to improve decision-making through the systematic utilization of measurable feedback.

Below are some of the benefits of evaluation research

- Gain insights about a project or program and its operations

Evaluation Research lets you understand what works and what doesn’t, where we were, where we are and where we are headed towards. You can find out the areas of improvement and identify strengths. So, it will help you to figure out what do you need to focus more on and if there are any threats to your business. You can also find out if there are currently hidden sectors in the market that are yet untapped.

- Improve practice

It is essential to gauge your past performance and understand what went wrong in order to deliver better services to your customers. Unless it is a two-way communication, there is no way to improve on what you have to offer. Evaluation research gives an opportunity to your employees and customers to express how they feel and if there’s anything they would like to change. It also lets you modify or adopt a practice such that it increases the chances of success.

- Assess the effects

After evaluating the efforts, you can see how well you are meeting objectives and targets. Evaluations let you measure if the intended benefits are really reaching the targeted audience and if yes, then how effectively.

- Build capacity

Evaluations help you to analyze the demand pattern and predict if you will need more funds, upgrade skills and improve the efficiency of operations. It lets you find the gaps in the production to delivery chain and possible ways to fill them.

Methods of evaluation research

All market research methods involve collecting and analyzing the data, making decisions about the validity of the information and deriving relevant inferences from it. Evaluation research comprises of planning, conducting and analyzing the results which include the use of data collection techniques and applying statistical methods.

Some of the evaluation methods which are quite popular are input measurement, output or performance measurement, impact or outcomes assessment, quality assessment, process evaluation, benchmarking, standards, cost analysis, organizational effectiveness, program evaluation methods, and LIS-centered methods. There are also a few types of evaluations that do not always result in a meaningful assessment such as descriptive studies, formative evaluations, and implementation analysis. Evaluation research is more about information-processing and feedback functions of evaluation.

These methods can be broadly classified as quantitative and qualitative methods.

The outcome of the quantitative research methods is an answer to the questions below and is used to measure anything tangible.

- Who was involved?

- What were the outcomes?

- What was the price?

The best way to collect quantitative data is through surveys , questionnaires , and polls . You can also create pre-tests and post-tests, review existing documents and databases or gather clinical data.

Surveys are used to gather opinions, feedback or ideas of your employees or customers and consist of various question types . They can be conducted by a person face-to-face or by telephone, by mail, or online. Online surveys do not require the intervention of any human and are far more efficient and practical. You can see the survey results on dashboard of research tools and dig deeper using filter criteria based on various factors such as age, gender, location, etc. You can also keep survey logic such as branching, quotas, chain survey, looping, etc in the survey questions and reduce the time to both create and respond to the donor survey . You can also generate a number of reports that involve statistical formulae and present data that can be readily absorbed in the meetings. To learn more about how research tool works and whether it is suitable for you, sign up for a free account now.

Create a free account!

Quantitative data measure the depth and breadth of an initiative, for instance, the number of people who participated in the non-profit event, the number of people who enrolled for a new course at the university. Quantitative data collected before and after a program can show its results and impact.

The accuracy of quantitative data to be used for evaluation research depends on how well the sample represents the population, the ease of analysis, and their consistency. Quantitative methods can fail if the questions are not framed correctly and not distributed to the right audience. Also, quantitative data do not provide an understanding of the context and may not be apt for complex issues.

Learn more: Quantitative Market Research: The Complete Guide

Qualitative research methods are used where quantitative methods cannot solve the research problem , i.e. they are used to measure intangible values. They answer questions such as

- What is the value added?

- How satisfied are you with our service?

- How likely are you to recommend us to your friends?

- What will improve your experience?

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

Qualitative data is collected through observation, interviews, case studies, and focus groups. The steps for creating a qualitative study involve examining, comparing and contrasting, and understanding patterns. Analysts conclude after identification of themes, clustering similar data, and finally reducing to points that make sense.

Observations may help explain behaviors as well as the social context that is generally not discovered by quantitative methods. Observations of behavior and body language can be done by watching a participant, recording audio or video. Structured interviews can be conducted with people alone or in a group under controlled conditions, or they may be asked open-ended qualitative research questions . Qualitative research methods are also used to understand a person’s perceptions and motivations.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

The strength of this method is that group discussion can provide ideas and stimulate memories with topics cascading as discussion occurs. The accuracy of qualitative data depends on how well contextual data explains complex issues and complements quantitative data. It helps get the answer of “why” and “how”, after getting an answer to “what”. The limitations of qualitative data for evaluation research are that they are subjective, time-consuming, costly and difficult to analyze and interpret.

Learn more: Qualitative Market Research: The Complete Guide

Survey software can be used for both the evaluation research methods. You can use above sample questions for evaluation research and send a survey in minutes using research software. Using a tool for research simplifies the process right from creating a survey, importing contacts, distributing the survey and generating reports that aid in research.

Examples of evaluation research

Evaluation research questions lay the foundation of a successful evaluation. They define the topics that will be evaluated. Keeping evaluation questions ready not only saves time and money, but also makes it easier to decide what data to collect, how to analyze it, and how to report it.

Evaluation research questions must be developed and agreed on in the planning stage, however, ready-made research templates can also be used.

Process evaluation research question examples:

- How often do you use our product in a day?

- Were approvals taken from all stakeholders?

- Can you report the issue from the system?

- Can you submit the feedback from the system?

- Was each task done as per the standard operating procedure?

- What were the barriers to the implementation of each task?

- Were any improvement areas discovered?

Outcome evaluation research question examples:

- How satisfied are you with our product?

- Did the program produce intended outcomes?

- What were the unintended outcomes?

- Has the program increased the knowledge of participants?

- Were the participants of the program employable before the course started?

- Do participants of the program have the skills to find a job after the course ended?

- Is the knowledge of participants better compared to those who did not participate in the program?

MORE LIKE THIS

Top 17 UX Research Software for UX Design in 2024

Apr 5, 2024

Healthcare Staff Burnout: What it Is + How To Manage It

Apr 4, 2024

Top 15 Employee Retention Software in 2024

Top 10 Employee Development Software for Talent Growth

Apr 3, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Evaluation Research Design: Examples, Methods & Types

As you engage in tasks, you will need to take intermittent breaks to determine how much progress has been made and if any changes need to be effected along the way. This is very similar to what organizations do when they carry out evaluation research.

The evaluation research methodology has become one of the most important approaches for organizations as they strive to create products, services, and processes that speak to the needs of target users. In this article, we will show you how your organization can conduct successful evaluation research using Formplus .

What is Evaluation Research?

Also known as program evaluation, evaluation research is a common research design that entails carrying out a structured assessment of the value of resources committed to a project or specific goal. It often adopts social research methods to gather and analyze useful information about organizational processes and products.

As a type of applied research , evaluation research typically associated with real-life scenarios within organizational contexts. This means that the researcher will need to leverage common workplace skills including interpersonal skills and team play to arrive at objective research findings that will be useful to stakeholders.

Characteristics of Evaluation Research

- Research Environment: Evaluation research is conducted in the real world; that is, within the context of an organization.

- Research Focus: Evaluation research is primarily concerned with measuring the outcomes of a process rather than the process itself.

- Research Outcome: Evaluation research is employed for strategic decision making in organizations.

- Research Goal: The goal of program evaluation is to determine whether a process has yielded the desired result(s).

- This type of research protects the interests of stakeholders in the organization.

- It often represents a middle-ground between pure and applied research.

- Evaluation research is both detailed and continuous. It pays attention to performative processes rather than descriptions.

- Research Process: This research design utilizes qualitative and quantitative research methods to gather relevant data about a product or action-based strategy. These methods include observation, tests, and surveys.

Types of Evaluation Research

The Encyclopedia of Evaluation (Mathison, 2004) treats forty-two different evaluation approaches and models ranging from “appreciative inquiry” to “connoisseurship” to “transformative evaluation”. Common types of evaluation research include the following:

- Formative Evaluation

Formative evaluation or baseline survey is a type of evaluation research that involves assessing the needs of the users or target market before embarking on a project. Formative evaluation is the starting point of evaluation research because it sets the tone of the organization’s project and provides useful insights for other types of evaluation.

- Mid-term Evaluation

Mid-term evaluation entails assessing how far a project has come and determining if it is in line with the set goals and objectives. Mid-term reviews allow the organization to determine if a change or modification of the implementation strategy is necessary, and it also serves for tracking the project.

- Summative Evaluation

This type of evaluation is also known as end-term evaluation of project-completion evaluation and it is conducted immediately after the completion of a project. Here, the researcher examines the value and outputs of the program within the context of the projected results.

Summative evaluation allows the organization to measure the degree of success of a project. Such results can be shared with stakeholders, target markets, and prospective investors.

- Outcome Evaluation

Outcome evaluation is primarily target-audience oriented because it measures the effects of the project, program, or product on the users. This type of evaluation views the outcomes of the project through the lens of the target audience and it often measures changes such as knowledge-improvement, skill acquisition, and increased job efficiency.

- Appreciative Enquiry

Appreciative inquiry is a type of evaluation research that pays attention to result-producing approaches. It is predicated on the belief that an organization will grow in whatever direction its stakeholders pay primary attention to such that if all the attention is focused on problems, identifying them would be easy.

In carrying out appreciative inquiry, the research identifies the factors directly responsible for the positive results realized in the course of a project, analyses the reasons for these results, and intensifies the utilization of these factors.

Evaluation Research Methodology

There are four major evaluation research methods, namely; output measurement, input measurement, impact assessment and service quality

- Output/Performance Measurement

Output measurement is a method employed in evaluative research that shows the results of an activity undertaking by an organization. In other words, performance measurement pays attention to the results achieved by the resources invested in a specific activity or organizational process.

More than investing resources in a project, organizations must be able to track the extent to which these resources have yielded results, and this is where performance measurement comes in. Output measurement allows organizations to pay attention to the effectiveness and impact of a process rather than just the process itself.

Other key indicators of performance measurement include user-satisfaction, organizational capacity, market penetration, and facility utilization. In carrying out performance measurement, organizations must identify the parameters that are relevant to the process in question, their industry, and the target markets.

5 Performance Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- What is the cost-effectiveness of this project?

- What is the overall reach of this project?

- How would you rate the market penetration of this project?

- How accessible is the project?

- Is this project time-efficient?

- Input Measurement

In evaluation research, input measurement entails assessing the number of resources committed to a project or goal in any organization. This is one of the most common indicators in evaluation research because it allows organizations to track their investments.

The most common indicator of inputs measurement is the budget which allows organizations to evaluate and limit expenditure for a project. It is also important to measure non-monetary investments like human capital; that is the number of persons needed for successful project execution and production capital.

5 Input Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- What is the budget for this project?

- What is the timeline of this process?

- How many employees have been assigned to this project?

- Do we need to purchase new machinery for this project?

- How many third-parties are collaborators in this project?

- Impact/Outcomes Assessment

In impact assessment, the evaluation researcher focuses on how the product or project affects target markets, both directly and indirectly. Outcomes assessment is somewhat challenging because many times, it is difficult to measure the real-time value and benefits of a project for the users.

In assessing the impact of a process, the evaluation researcher must pay attention to the improvement recorded by the users as a result of the process or project in question. Hence, it makes sense to focus on cognitive and affective changes, expectation-satisfaction, and similar accomplishments of the users.

5 Impact Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- How has this project affected you?

- Has this process affected you positively or negatively?

- What role did this project play in improving your earning power?

- On a scale of 1-10, how excited are you about this project?

- How has this project improved your mental health?

- Service Quality

Service quality is the evaluation research method that accounts for any differences between the expectations of the target markets and their impression of the undertaken project. Hence, it pays attention to the overall service quality assessment carried out by the users.

It is not uncommon for organizations to build the expectations of target markets as they embark on specific projects. Service quality evaluation allows these organizations to track the extent to which the actual product or service delivery fulfils the expectations.

5 Service Quality Evaluation Questions

- On a scale of 1-10, how satisfied are you with the product?

- How helpful was our customer service representative?

- How satisfied are you with the quality of service?

- How long did it take to resolve the issue at hand?

- How likely are you to recommend us to your network?

Uses of Evaluation Research

- Evaluation research is used by organizations to measure the effectiveness of activities and identify areas needing improvement. Findings from evaluation research are key to project and product advancements and are very influential in helping organizations realize their goals efficiently.

- The findings arrived at from evaluation research serve as evidence of the impact of the project embarked on by an organization. This information can be presented to stakeholders, customers, and can also help your organization secure investments for future projects.

- Evaluation research helps organizations to justify their use of limited resources and choose the best alternatives.

- It is also useful in pragmatic goal setting and realization.

- Evaluation research provides detailed insights into projects embarked on by an organization. Essentially, it allows all stakeholders to understand multiple dimensions of a process, and to determine strengths and weaknesses.

- Evaluation research also plays a major role in helping organizations to improve their overall practice and service delivery. This research design allows organizations to weigh existing processes through feedback provided by stakeholders, and this informs better decision making.

- Evaluation research is also instrumental to sustainable capacity building. It helps you to analyze demand patterns and determine whether your organization requires more funds, upskilling or improved operations.

Data Collection Techniques Used in Evaluation Research

In gathering useful data for evaluation research, the researcher often combines quantitative and qualitative research methods . Qualitative research methods allow the researcher to gather information relating to intangible values such as market satisfaction and perception.

On the other hand, quantitative methods are used by the evaluation researcher to assess numerical patterns, that is, quantifiable data. These methods help you measure impact and results; although they may not serve for understanding the context of the process.

Quantitative Methods for Evaluation Research

A survey is a quantitative method that allows you to gather information about a project from a specific group of people. Surveys are largely context-based and limited to target groups who are asked a set of structured questions in line with the predetermined context.

Surveys usually consist of close-ended questions that allow the evaluative researcher to gain insight into several variables including market coverage and customer preferences. Surveys can be carried out physically using paper forms or online through data-gathering platforms like Formplus .

- Questionnaires

A questionnaire is a common quantitative research instrument deployed in evaluation research. Typically, it is an aggregation of different types of questions or prompts which help the researcher to obtain valuable information from respondents.

A poll is a common method of opinion-sampling that allows you to weigh the perception of the public about issues that affect them. The best way to achieve accuracy in polling is by conducting them online using platforms like Formplus.

Polls are often structured as Likert questions and the options provided always account for neutrality or indecision. Conducting a poll allows the evaluation researcher to understand the extent to which the product or service satisfies the needs of the users.

Qualitative Methods for Evaluation Research

- One-on-One Interview

An interview is a structured conversation involving two participants; usually the researcher and the user or a member of the target market. One-on-One interviews can be conducted physically, via the telephone and through video conferencing apps like Zoom and Google Meet.

- Focus Groups

A focus group is a research method that involves interacting with a limited number of persons within your target market, who can provide insights on market perceptions and new products.

- Qualitative Observation

Qualitative observation is a research method that allows the evaluation researcher to gather useful information from the target audience through a variety of subjective approaches. This method is more extensive than quantitative observation because it deals with a smaller sample size, and it also utilizes inductive analysis.

- Case Studies

A case study is a research method that helps the researcher to gain a better understanding of a subject or process. Case studies involve in-depth research into a given subject, to understand its functionalities and successes.

How to Formplus Online Form Builder for Evaluation Survey

- Sign into Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create your evaluation survey by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on “Create Form ” to begin.

- Edit Form Title

Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Evaluation Research Survey”.

Click on the edit button to edit the form.

Add Fields: Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for surveys in the Formplus builder.

Edit fields

Click on “Save”

Preview form.

- Form Customization

With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the outlook of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images, and even change the font according to your needs.

- Multiple Sharing Options

Formplus offers multiple form sharing options which enables you to easily share your evaluation survey with survey respondents. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages.

You can send out your survey form as email invitations to your research subjects too. If you wish, you can share your form’s QR code or embed it on your organization’s website for easy access.

Conclusion

Conducting evaluation research allows organizations to determine the effectiveness of their activities at different phases. This type of research can be carried out using qualitative and quantitative data collection methods including focus groups, observation, telephone and one-on-one interviews, and surveys.

Online surveys created and administered via data collection platforms like Formplus make it easier for you to gather and process information during evaluation research. With Formplus multiple form sharing options, it is even easier for you to gather useful data from target markets.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- characteristics of evaluation research

- evaluation research methods

- types of evaluation research

- what is evaluation research

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Formal Assessment: Definition, Types Examples & Benefits

In this article, we will discuss different types and examples of formal evaluation, and show you how to use Formplus for online assessments.

Recall Bias: Definition, Types, Examples & Mitigation

This article will discuss the impact of recall bias in studies and the best ways to avoid them during research.

What is Pure or Basic Research? + [Examples & Method]

Simple guide on pure or basic research, its methods, characteristics, advantages, and examples in science, medicine, education and psychology

Assessment vs Evaluation: 11 Key Differences

This article will discuss what constitutes evaluations and assessments along with the key differences between these two research methods.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Search form

- Table of Contents

- Troubleshooting Guide

- A Model for Getting Started

- Justice Action Toolkit

- Best Change Processes

- Databases of Best Practices

- Online Courses

- Ask an Advisor

- Subscribe to eNewsletter

- Community Stories

- YouTube Channel

- About the Tool Box

- How to Use the Tool Box

- Privacy Statement

- Workstation/Check Box Sign-In

- Online Training Courses

- Capacity Building Training

- Training Curriculum - Order Now

- Community Check Box Evaluation System

- Build Your Toolbox

- Facilitation of Community Processes

- Community Health Assessment and Planning

- Section 1. A Framework for Program Evaluation: A Gateway to Tools

Chapter 36 Sections

- Section 2. Community-based Participatory Research

- Section 3. Understanding Community Leadership, Evaluators, and Funders: What Are Their Interests?

- Section 4. Choosing Evaluators

- Section 5. Developing an Evaluation Plan

- Section 6. Participatory Evaluation

- Main Section

This section is adapted from the article "Recommended Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health Practice," by Bobby Milstein, Scott Wetterhall, and the CDC Evaluation Working Group.

Around the world, there exist many programs and interventions developed to improve conditions in local communities. Communities come together to reduce the level of violence that exists, to work for safe, affordable housing for everyone, or to help more students do well in school, to give just a few examples.

But how do we know whether these programs are working? If they are not effective, and even if they are, how can we improve them to make them better for local communities? And finally, how can an organization make intelligent choices about which promising programs are likely to work best in their community?

Over the past years, there has been a growing trend towards the better use of evaluation to understand and improve practice.The systematic use of evaluation has solved many problems and helped countless community-based organizations do what they do better.

Despite an increased understanding of the need for - and the use of - evaluation, however, a basic agreed-upon framework for program evaluation has been lacking. In 1997, scientists at the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognized the need to develop such a framework. As a result of this, the CDC assembled an Evaluation Working Group comprised of experts in the fields of public health and evaluation. Members were asked to develop a framework that summarizes and organizes the basic elements of program evaluation. This Community Tool Box section describes the framework resulting from the Working Group's efforts.

Before we begin, however, we'd like to offer some definitions of terms that we will use throughout this section.

By evaluation , we mean the systematic investigation of the merit, worth, or significance of an object or effort. Evaluation practice has changed dramatically during the past three decades - new methods and approaches have been developed and it is now used for increasingly diverse projects and audiences.

Throughout this section, the term program is used to describe the object or effort that is being evaluated. It may apply to any action with the goal of improving outcomes for whole communities, for more specific sectors (e.g., schools, work places), or for sub-groups (e.g., youth, people experiencing violence or HIV/AIDS). This definition is meant to be very broad.

Examples of different types of programs include:

- Direct service interventions (e.g., a program that offers free breakfast to improve nutrition for grade school children)

- Community mobilization efforts (e.g., organizing a boycott of California grapes to improve the economic well-being of farm workers)

- Research initiatives (e.g., an effort to find out whether inequities in health outcomes based on race can be reduced)

- Surveillance systems (e.g., whether early detection of school readiness improves educational outcomes)

- Advocacy work (e.g., a campaign to influence the state legislature to pass legislation regarding tobacco control)

- Social marketing campaigns (e.g., a campaign in the Third World encouraging mothers to breast-feed their babies to reduce infant mortality)

- Infrastructure building projects (e.g., a program to build the capacity of state agencies to support community development initiatives)

- Training programs (e.g., a job training program to reduce unemployment in urban neighborhoods)

- Administrative systems (e.g., an incentive program to improve efficiency of health services)

Program evaluation - the type of evaluation discussed in this section - is an essential organizational practice for all types of community health and development work. It is a way to evaluate the specific projects and activities community groups may take part in, rather than to evaluate an entire organization or comprehensive community initiative.

Stakeholders refer to those who care about the program or effort. These may include those presumed to benefit (e.g., children and their parents or guardians), those with particular influence (e.g., elected or appointed officials), and those who might support the effort (i.e., potential allies) or oppose it (i.e., potential opponents). Key questions in thinking about stakeholders are: Who cares? What do they care about?

This section presents a framework that promotes a common understanding of program evaluation. The overall goal is to make it easier for everyone involved in community health and development work to evaluate their efforts.

Why evaluate community health and development programs?

The type of evaluation we talk about in this section can be closely tied to everyday program operations. Our emphasis is on practical, ongoing evaluation that involves program staff, community members, and other stakeholders, not just evaluation experts. This type of evaluation offers many advantages for community health and development professionals.

For example, it complements program management by:

- Helping to clarify program plans

- Improving communication among partners

- Gathering the feedback needed to improve and be accountable for program effectiveness

It's important to remember, too, that evaluation is not a new activity for those of us working to improve our communities. In fact, we assess the merit of our work all the time when we ask questions, consult partners, make assessments based on feedback, and then use those judgments to improve our work. When the stakes are low, this type of informal evaluation might be enough. However, when the stakes are raised - when a good deal of time or money is involved, or when many people may be affected - then it may make sense for your organization to use evaluation procedures that are more formal, visible, and justifiable.

How do you evaluate a specific program?

Before your organization starts with a program evaluation, your group should be very clear about the answers to the following questions:.

- What will be evaluated?

- What criteria will be used to judge program performance?

- What standards of performance on the criteria must be reached for the program to be considered successful?

- What evidence will indicate performance on the criteria relative to the standards?

- What conclusions about program performance are justified based on the available evidence?

To clarify the meaning of each, let's look at some of the answers for Drive Smart, a hypothetical program begun to stop drunk driving.

- Drive Smart, a program focused on reducing drunk driving through public education and intervention.

- The number of community residents who are familiar with the program and its goals

- The number of people who use "Safe Rides" volunteer taxis to get home

- The percentage of people who report drinking and driving

- The reported number of single car night time crashes (This is a common way to try to determine if the number of people who drive drunk is changing)

- 80% of community residents will know about the program and its goals after the first year of the program

- The number of people who use the "Safe Rides" taxis will increase by 20% in the first year

- The percentage of people who report drinking and driving will decrease by 20% in the first year

- The reported number of single car night time crashes will decrease by 10 % in the program's first two years

- A random telephone survey will demonstrate community residents' knowledge of the program and changes in reported behavior

- Logs from "Safe Rides" will tell how many people use their services

- Information on single car night time crashes will be gathered from police records

- Are the changes we have seen in the level of drunk driving due to our efforts, or something else? Or (if no or insufficient change in behavior or outcome,)

- Should Drive Smart change what it is doing, or have we just not waited long enough to see results?

The following framework provides an organized approach to answer these questions.

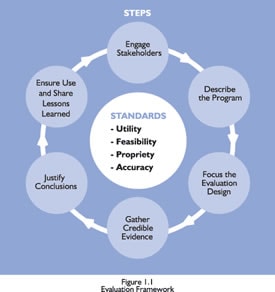

A framework for program evaluation

Program evaluation offers a way to understand and improve community health and development practice using methods that are useful, feasible, proper, and accurate. The framework described below is a practical non-prescriptive tool that summarizes in a logical order the important elements of program evaluation.

The framework contains two related dimensions:

- Steps in evaluation practice, and

- Standards for "good" evaluation.

The six connected steps of the framework are actions that should be a part of any evaluation. Although in practice the steps may be encountered out of order, it will usually make sense to follow them in the recommended sequence. That's because earlier steps provide the foundation for subsequent progress. Thus, decisions about how to carry out a given step should not be finalized until prior steps have been thoroughly addressed.

However, these steps are meant to be adaptable, not rigid. Sensitivity to each program's unique context (for example, the program's history and organizational climate) is essential for sound evaluation. They are intended to serve as starting points around which community organizations can tailor an evaluation to best meet their needs.

- Engage stakeholders

- Describe the program

- Focus the evaluation design

- Gather credible evidence

- Justify conclusions

- Ensure use and share lessons learned

Understanding and adhering to these basic steps will improve most evaluation efforts.

The second part of the framework is a basic set of standards to assess the quality of evaluation activities. There are 30 specific standards, organized into the following four groups:

- Feasibility

These standards help answer the question, "Will this evaluation be a 'good' evaluation?" They are recommended as the initial criteria by which to judge the quality of the program evaluation efforts.

Engage Stakeholders

Stakeholders are people or organizations that have something to gain or lose from what will be learned from an evaluation, and also in what will be done with that knowledge. Evaluation cannot be done in isolation. Almost everything done in community health and development work involves partnerships - alliances among different organizations, board members, those affected by the problem, and others. Therefore, any serious effort to evaluate a program must consider the different values held by the partners. Stakeholders must be part of the evaluation to ensure that their unique perspectives are understood. When stakeholders are not appropriately involved, evaluation findings are likely to be ignored, criticized, or resisted.

However, if they are part of the process, people are likely to feel a good deal of ownership for the evaluation process and results. They will probably want to develop it, defend it, and make sure that the evaluation really works.

That's why this evaluation cycle begins by engaging stakeholders. Once involved, these people will help to carry out each of the steps that follows.

Three principle groups of stakeholders are important to involve:

- People or organizations involved in program operations may include community members, sponsors, collaborators, coalition partners, funding officials, administrators, managers, and staff.

- People or organizations served or affected by the program may include clients, family members, neighborhood organizations, academic institutions, elected and appointed officials, advocacy groups, and community residents. Individuals who are openly skeptical of or antagonistic toward the program may also be important to involve. Opening an evaluation to opposing perspectives and enlisting the help of potential program opponents can strengthen the evaluation's credibility.

Likewise, individuals or groups who could be adversely or inadvertently affected by changes arising from the evaluation have a right to be engaged. For example, it is important to include those who would be affected if program services were expanded, altered, limited, or ended as a result of the evaluation.

- Primary intended users of the evaluation are the specific individuals who are in a position to decide and/or do something with the results.They shouldn't be confused with primary intended users of the program, although some of them should be involved in this group. In fact, primary intended users should be a subset of all of the stakeholders who have been identified. A successful evaluation will designate primary intended users, such as program staff and funders, early in its development and maintain frequent interaction with them to be sure that the evaluation specifically addresses their values and needs.

The amount and type of stakeholder involvement will be different for each program evaluation. For instance, stakeholders can be directly involved in designing and conducting the evaluation. They can be kept informed about progress of the evaluation through periodic meetings, reports, and other means of communication.

It may be helpful, when working with a group such as this, to develop an explicit process to share power and resolve conflicts . This may help avoid overemphasis of values held by any specific stakeholder.

Describe the Program

A program description is a summary of the intervention being evaluated. It should explain what the program is trying to accomplish and how it tries to bring about those changes. The description will also illustrate the program's core components and elements, its ability to make changes, its stage of development, and how the program fits into the larger organizational and community environment.

How a program is described sets the frame of reference for all future decisions about its evaluation. For example, if a program is described as, "attempting to strengthen enforcement of existing laws that discourage underage drinking," the evaluation might be very different than if it is described as, "a program to reduce drunk driving by teens." Also, the description allows members of the group to compare the program to other similar efforts, and it makes it easier to figure out what parts of the program brought about what effects.

Moreover, different stakeholders may have different ideas about what the program is supposed to achieve and why. For example, a program to reduce teen pregnancy may have some members who believe this means only increasing access to contraceptives, and other members who believe it means only focusing on abstinence.

Evaluations done without agreement on the program definition aren't likely to be very useful. In many cases, the process of working with stakeholders to develop a clear and logical program description will bring benefits long before data are available to measure program effectiveness.

There are several specific aspects that should be included when describing a program.

Statement of need

A statement of need describes the problem, goal, or opportunity that the program addresses; it also begins to imply what the program will do in response. Important features to note regarding a program's need are: the nature of the problem or goal, who is affected, how big it is, and whether (and how) it is changing.

Expectations

Expectations are the program's intended results. They describe what the program has to accomplish to be considered successful. For most programs, the accomplishments exist on a continuum (first, we want to accomplish X... then, we want to do Y...). Therefore, they should be organized by time ranging from specific (and immediate) to broad (and longer-term) consequences. For example, a program's vision, mission, goals, and objectives , all represent varying levels of specificity about a program's expectations.

Activities are everything the program does to bring about changes. Describing program components and elements permits specific strategies and actions to be listed in logical sequence. This also shows how different program activities, such as education and enforcement, relate to one another. Describing program activities also provides an opportunity to distinguish activities that are the direct responsibility of the program from those that are conducted by related programs or partner organizations. Things outside of the program that may affect its success, such as harsher laws punishing businesses that sell alcohol to minors, can also be noted.

Resources include the time, talent, equipment, information, money, and other assets available to conduct program activities. Reviewing the resources a program has tells a lot about the amount and intensity of its services. It may also point out situations where there is a mismatch between what the group wants to do and the resources available to carry out these activities. Understanding program costs is a necessity to assess the cost-benefit ratio as part of the evaluation.

Stage of development

A program's stage of development reflects its maturity. All community health and development programs mature and change over time. People who conduct evaluations, as well as those who use their findings, need to consider the dynamic nature of programs. For example, a new program that just received its first grant may differ in many respects from one that has been running for over a decade.

At least three phases of development are commonly recognized: planning , implementation , and effects or outcomes . In the planning stage, program activities are untested and the goal of evaluation is to refine plans as much as possible. In the implementation phase, program activities are being field tested and modified; the goal of evaluation is to see what happens in the "real world" and to improve operations. In the effects stage, enough time has passed for the program's effects to emerge; the goal of evaluation is to identify and understand the program's results, including those that were unintentional.

A description of the program's context considers the important features of the environment in which the program operates. This includes understanding the area's history, geography, politics, and social and economic conditions, and also what other organizations have done. A realistic and responsive evaluation is sensitive to a broad range of potential influences on the program. An understanding of the context lets users interpret findings accurately and assess their generalizability. For example, a program to improve housing in an inner-city neighborhood might have been a tremendous success, but would likely not work in a small town on the other side of the country without significant adaptation.

Logic model

A logic model synthesizes the main program elements into a picture of how the program is supposed to work. It makes explicit the sequence of events that are presumed to bring about change. Often this logic is displayed in a flow-chart, map, or table to portray the sequence of steps leading to program results.

Creating a logic model allows stakeholders to improve and focus program direction. It reveals assumptions about conditions for program effectiveness and provides a frame of reference for one or more evaluations of the program. A detailed logic model can also be a basis for estimating the program's effect on endpoints that are not directly measured. For example, it may be possible to estimate the rate of reduction in disease from a known number of persons experiencing the intervention if there is prior knowledge about its effectiveness.

The breadth and depth of a program description will vary for each program evaluation. And so, many different activities may be part of developing that description. For instance, multiple sources of information could be pulled together to construct a well-rounded description. The accuracy of an existing program description could be confirmed through discussion with stakeholders. Descriptions of what's going on could be checked against direct observation of activities in the field. A narrow program description could be fleshed out by addressing contextual factors (such as staff turnover, inadequate resources, political pressures, or strong community participation) that may affect program performance.

Focus the Evaluation Design

By focusing the evaluation design, we mean doing advance planning about where the evaluation is headed, and what steps it will take to get there. It isn't possible or useful for an evaluation to try to answer all questions for all stakeholders; there must be a focus. A well-focused plan is a safeguard against using time and resources inefficiently.

Depending on what you want to learn, some types of evaluation will be better suited than others. However, once data collection begins, it may be difficult or impossible to change what you are doing, even if it becomes obvious that other methods would work better. A thorough plan anticipates intended uses and creates an evaluation strategy with the greatest chance to be useful, feasible, proper, and accurate.

Among the issues to consider when focusing an evaluation are:

Purpose refers to the general intent of the evaluation. A clear purpose serves as the basis for the design, methods, and use of the evaluation. Taking time to articulate an overall purpose will stop your organization from making uninformed decisions about how the evaluation should be conducted and used.

There are at least four general purposes for which a community group might conduct an evaluation:

- To gain insight .This happens, for example, when deciding whether to use a new approach (e.g., would a neighborhood watch program work for our community?) Knowledge from such an evaluation will provide information about its practicality. For a developing program, information from evaluations of similar programs can provide the insight needed to clarify how its activities should be designed.

- To improve how things get done .This is appropriate in the implementation stage when an established program tries to describe what it has done. This information can be used to describe program processes, to improve how the program operates, and to fine-tune the overall strategy. Evaluations done for this purpose include efforts to improve the quality, effectiveness, or efficiency of program activities.

- To determine what the effects of the program are . Evaluations done for this purpose examine the relationship between program activities and observed consequences. For example, are more students finishing high school as a result of the program? Programs most appropriate for this type of evaluation are mature programs that are able to state clearly what happened and who it happened to. Such evaluations should provide evidence about what the program's contribution was to reaching longer-term goals such as a decrease in child abuse or crime in the area. This type of evaluation helps establish the accountability, and thus, the credibility, of a program to funders and to the community.

- Empower program participants (for example, being part of an evaluation can increase community members' sense of control over the program);

- Supplement the program (for example, using a follow-up questionnaire can reinforce the main messages of the program);

- Promote staff development (for example, by teaching staff how to collect, analyze, and interpret evidence); or

- Contribute to organizational growth (for example, the evaluation may clarify how the program relates to the organization's mission).

Users are the specific individuals who will receive evaluation findings. They will directly experience the consequences of inevitable trade-offs in the evaluation process. For example, a trade-off might be having a relatively modest evaluation to fit the budget with the outcome that the evaluation results will be less certain than they would be for a full-scale evaluation. Because they will be affected by these tradeoffs, intended users have a right to participate in choosing a focus for the evaluation. An evaluation designed without adequate user involvement in selecting the focus can become a misguided and irrelevant exercise. By contrast, when users are encouraged to clarify intended uses, priority questions, and preferred methods, the evaluation is more likely to focus on things that will inform (and influence) future actions.

Uses describe what will be done with what is learned from the evaluation. There is a wide range of potential uses for program evaluation. Generally speaking, the uses fall in the same four categories as the purposes listed above: to gain insight, improve how things get done, determine what the effects of the program are, and affect participants. The following list gives examples of uses in each category.

Some specific examples of evaluation uses

To gain insight:.

- Assess needs and wants of community members

- Identify barriers to use of the program

- Learn how to best describe and measure program activities

To improve how things get done:

- Refine plans for introducing a new practice

- Determine the extent to which plans were implemented

- Improve educational materials

- Enhance cultural competence

- Verify that participants' rights are protected

- Set priorities for staff training

- Make mid-course adjustments

- Clarify communication

- Determine if client satisfaction can be improved

- Compare costs to benefits

- Find out which participants benefit most from the program

- Mobilize community support for the program

To determine what the effects of the program are:

- Assess skills development by program participants

- Compare changes in behavior over time

- Decide where to allocate new resources

- Document the level of success in accomplishing objectives

- Demonstrate that accountability requirements are fulfilled

- Use information from multiple evaluations to predict the likely effects of similar programs

To affect participants:

- Reinforce messages of the program

- Stimulate dialogue and raise awareness about community issues

- Broaden consensus among partners about program goals

- Teach evaluation skills to staff and other stakeholders

- Gather success stories

- Support organizational change and improvement

The evaluation needs to answer specific questions . Drafting questions encourages stakeholders to reveal what they believe the evaluation should answer. That is, what questions are more important to stakeholders? The process of developing evaluation questions further refines the focus of the evaluation.

The methods available for an evaluation are drawn from behavioral science and social research and development. Three types of methods are commonly recognized. They are experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational or case study designs. Experimental designs use random assignment to compare the effect of an intervention between otherwise equivalent groups (for example, comparing a randomly assigned group of students who took part in an after-school reading program with those who didn't). Quasi-experimental methods make comparisons between groups that aren't equal (e.g. program participants vs. those on a waiting list) or use of comparisons within a group over time, such as in an interrupted time series in which the intervention may be introduced sequentially across different individuals, groups, or contexts. Observational or case study methods use comparisons within a group to describe and explain what happens (e.g., comparative case studies with multiple communities).

No design is necessarily better than another. Evaluation methods should be selected because they provide the appropriate information to answer stakeholders' questions, not because they are familiar, easy, or popular. The choice of methods has implications for what will count as evidence, how that evidence will be gathered, and what kind of claims can be made. Because each method option has its own biases and limitations, evaluations that mix methods are generally more robust.

Over the course of an evaluation, methods may need to be revised or modified. Circumstances that make a particular approach useful can change. For example, the intended use of the evaluation could shift from discovering how to improve the program to helping decide about whether the program should continue or not. Thus, methods may need to be adapted or redesigned to keep the evaluation on track.

Agreements summarize the evaluation procedures and clarify everyone's roles and responsibilities. An agreement describes how the evaluation activities will be implemented. Elements of an agreement include statements about the intended purpose, users, uses, and methods, as well as a summary of the deliverables, those responsible, a timeline, and budget.

The formality of the agreement depends upon the relationships that exist between those involved. For example, it may take the form of a legal contract, a detailed protocol, or a simple memorandum of understanding. Regardless of its formality, creating an explicit agreement provides an opportunity to verify the mutual understanding needed for a successful evaluation. It also provides a basis for modifying procedures if that turns out to be necessary.

As you can see, focusing the evaluation design may involve many activities. For instance, both supporters and skeptics of the program could be consulted to ensure that the proposed evaluation questions are politically viable. A menu of potential evaluation uses appropriate for the program's stage of development could be circulated among stakeholders to determine which is most compelling. Interviews could be held with specific intended users to better understand their information needs and timeline for action. Resource requirements could be reduced when users are willing to employ more timely but less precise evaluation methods.

Gather Credible Evidence

Credible evidence is the raw material of a good evaluation. The information learned should be seen by stakeholders as believable, trustworthy, and relevant to answer their questions. This requires thinking broadly about what counts as "evidence." Such decisions are always situational; they depend on the question being posed and the motives for asking it. For some questions, a stakeholder's standard for credibility could demand having the results of a randomized experiment. For another question, a set of well-done, systematic observations such as interactions between an outreach worker and community residents, will have high credibility. The difference depends on what kind of information the stakeholders want and the situation in which it is gathered.

Context matters! In some situations, it may be necessary to consult evaluation specialists. This may be especially true if concern for data quality is especially high. In other circumstances, local people may offer the deepest insights. Regardless of their expertise, however, those involved in an evaluation should strive to collect information that will convey a credible, well-rounded picture of the program and its efforts.

Having credible evidence strengthens the evaluation results as well as the recommendations that follow from them. Although all types of data have limitations, it is possible to improve an evaluation's overall credibility. One way to do this is by using multiple procedures for gathering, analyzing, and interpreting data. Encouraging participation by stakeholders can also enhance perceived credibility. When stakeholders help define questions and gather data, they will be more likely to accept the evaluation's conclusions and to act on its recommendations.

The following features of evidence gathering typically affect how credible it is seen as being:

Indicators translate general concepts about the program and its expected effects into specific, measurable parts.

Examples of indicators include:

- The program's capacity to deliver services

- The participation rate

- The level of client satisfaction

- The amount of intervention exposure (how many people were exposed to the program, and for how long they were exposed)

- Changes in participant behavior

- Changes in community conditions or norms

- Changes in the environment (e.g., new programs, policies, or practices)

- Longer-term changes in population health status (e.g., estimated teen pregnancy rate in the county)

Indicators should address the criteria that will be used to judge the program. That is, they reflect the aspects of the program that are most meaningful to monitor. Several indicators are usually needed to track the implementation and effects of a complex program or intervention.

One way to develop multiple indicators is to create a "balanced scorecard," which contains indicators that are carefully selected to complement one another. According to this strategy, program processes and effects are viewed from multiple perspectives using small groups of related indicators. For instance, a balanced scorecard for a single program might include indicators of how the program is being delivered; what participants think of the program; what effects are observed; what goals were attained; and what changes are occurring in the environment around the program.

Another approach to using multiple indicators is based on a program logic model, such as we discussed earlier in the section. A logic model can be used as a template to define a full spectrum of indicators along the pathway that leads from program activities to expected effects. For each step in the model, qualitative and/or quantitative indicators could be developed.

Indicators can be broad-based and don't need to focus only on a program's long -term goals. They can also address intermediary factors that influence program effectiveness, including such intangible factors as service quality, community capacity, or inter -organizational relations. Indicators for these and similar concepts can be created by systematically identifying and then tracking markers of what is said or done when the concept is expressed.

In the course of an evaluation, indicators may need to be modified or new ones adopted. Also, measuring program performance by tracking indicators is only one part of evaluation, and shouldn't be confused as a basis for decision making in itself. There are definite perils to using performance indicators as a substitute for completing the evaluation process and reaching fully justified conclusions. For example, an indicator, such as a rising rate of unemployment, may be falsely assumed to reflect a failing program when it may actually be due to changing environmental conditions that are beyond the program's control.

Sources of evidence in an evaluation may be people, documents, or observations. More than one source may be used to gather evidence for each indicator. In fact, selecting multiple sources provides an opportunity to include different perspectives about the program and enhances the evaluation's credibility. For instance, an inside perspective may be reflected by internal documents and comments from staff or program managers; whereas clients and those who do not support the program may provide different, but equally relevant perspectives. Mixing these and other perspectives provides a more comprehensive view of the program or intervention.

The criteria used to select sources should be clearly stated so that users and other stakeholders can interpret the evidence accurately and assess if it may be biased. In addition, some sources provide information in narrative form (for example, a person's experience when taking part in the program) and others are numerical (for example, how many people were involved in the program). The integration of qualitative and quantitative information can yield evidence that is more complete and more useful, thus meeting the needs and expectations of a wider range of stakeholders.

Quality refers to the appropriateness and integrity of information gathered in an evaluation. High quality data are reliable and informative. It is easier to collect if the indicators have been well defined. Other factors that affect quality may include instrument design, data collection procedures, training of those involved in data collection, source selection, coding, data management, and routine error checking. Obtaining quality data will entail tradeoffs (e.g. breadth vs. depth); stakeholders should decide together what is most important to them. Because all data have limitations, the intent of a practical evaluation is to strive for a level of quality that meets the stakeholders' threshold for credibility.

Quantity refers to the amount of evidence gathered in an evaluation. It is necessary to estimate in advance the amount of information that will be required and to establish criteria to decide when to stop collecting data - to know when enough is enough. Quantity affects the level of confidence or precision users can have - how sure we are that what we've learned is true. It also partly determines whether the evaluation will be able to detect effects. All evidence collected should have a clear, anticipated use.

By logistics , we mean the methods, timing, and physical infrastructure for gathering and handling evidence. People and organizations also have cultural preferences that dictate acceptable ways of asking questions and collecting information, including who would be perceived as an appropriate person to ask the questions. For example, some participants may be unwilling to discuss their behavior with a stranger, whereas others are more at ease with someone they don't know. Therefore, the techniques for gathering evidence in an evaluation must be in keeping with the cultural norms of the community. Data collection procedures should also ensure that confidentiality is protected.

Justify Conclusions

The process of justifying conclusions recognizes that evidence in an evaluation does not necessarily speak for itself. Evidence must be carefully considered from a number of different stakeholders' perspectives to reach conclusions that are well -substantiated and justified. Conclusions become justified when they are linked to the evidence gathered and judged against agreed-upon values set by the stakeholders. Stakeholders must agree that conclusions are justified in order to use the evaluation results with confidence.

The principal elements involved in justifying conclusions based on evidence are:

Standards reflect the values held by stakeholders about the program. They provide the basis to make program judgments. The use of explicit standards for judgment is fundamental to sound evaluation. In practice, when stakeholders articulate and negotiate their values, these become the standards to judge whether a given program's performance will, for instance, be considered "successful," "adequate," or "unsuccessful."

Analysis and synthesis

Analysis and synthesis are methods to discover and summarize an evaluation's findings. They are designed to detect patterns in evidence, either by isolating important findings (analysis) or by combining different sources of information to reach a larger understanding (synthesis). Mixed method evaluations require the separate analysis of each evidence element, as well as a synthesis of all sources to examine patterns that emerge. Deciphering facts from a given body of evidence involves deciding how to organize, classify, compare, and display information. These decisions are guided by the questions being asked, the types of data available, and especially by input from stakeholders and primary intended users.

Interpretation

Interpretation is the effort to figure out what the findings mean. Uncovering facts about a program's performance isn't enough to make conclusions. The facts must be interpreted to understand their practical significance. For example, saying, "15 % of the people in our area witnessed a violent act last year," may be interpreted differently depending on the situation. For example, if 50% of community members had watched a violent act in the last year when they were surveyed five years ago, the group can suggest that, while still a problem, things are getting better in the community. However, if five years ago only 7% of those surveyed said the same thing, community organizations may see this as a sign that they might want to change what they are doing. In short, interpretations draw on information and perspectives that stakeholders bring to the evaluation. They can be strengthened through active participation or interaction with the data and preliminary explanations of what happened.

Judgments are statements about the merit, worth, or significance of the program. They are formed by comparing the findings and their interpretations against one or more selected standards. Because multiple standards can be applied to a given program, stakeholders may reach different or even conflicting judgments. For instance, a program that increases its outreach by 10% from the previous year may be judged positively by program managers, based on standards of improved performance over time. Community members, however, may feel that despite improvements, a minimum threshold of access to services has still not been reached. Their judgment, based on standards of social equity, would therefore be negative. Conflicting claims about a program's quality, value, or importance often indicate that stakeholders are using different standards or values in making judgments. This type of disagreement can be a catalyst to clarify values and to negotiate the appropriate basis (or bases) on which the program should be judged.

Recommendations

Recommendations are actions to consider as a result of the evaluation. Forming recommendations requires information beyond just what is necessary to form judgments. For example, knowing that a program is able to increase the services available to battered women doesn't necessarily translate into a recommendation to continue the effort, particularly when there are competing priorities or other effective alternatives. Thus, recommendations about what to do with a given intervention go beyond judgments about a specific program's effectiveness.

If recommendations aren't supported by enough evidence, or if they aren't in keeping with stakeholders' values, they can really undermine an evaluation's credibility. By contrast, an evaluation can be strengthened by recommendations that anticipate and react to what users will want to know.

Three things might increase the chances that recommendations will be relevant and well-received:

- Sharing draft recommendations

- Soliciting reactions from multiple stakeholders

- Presenting options instead of directive advice

Justifying conclusions in an evaluation is a process that involves different possible steps. For instance, conclusions could be strengthened by searching for alternative explanations from the ones you have chosen, and then showing why they are unsupported by the evidence. When there are different but equally well supported conclusions, each could be presented with a summary of their strengths and weaknesses. Techniques to analyze, synthesize, and interpret findings might be agreed upon before data collection begins.

Ensure Use and Share Lessons Learned

It is naive to assume that lessons learned in an evaluation will necessarily be used in decision making and subsequent action. Deliberate effort on the part of evaluators is needed to ensure that the evaluation findings will be used appropriately. Preparing for their use involves strategic thinking and continued vigilance in looking for opportunities to communicate and influence. Both of these should begin in the earliest stages of the process and continue throughout the evaluation.

The elements of key importance to be sure that the recommendations from an evaluation are used are:

Design refers to how the evaluation's questions, methods, and overall processes are constructed. As discussed in the third step of this framework (focusing the evaluation design), the evaluation should be organized from the start to achieve specific agreed-upon uses. Having a clear purpose that is focused on the use of what is learned helps those who will carry out the evaluation to know who will do what with the findings. Furthermore, the process of creating a clear design will highlight ways that stakeholders, through their many contributions, can improve the evaluation and facilitate the use of the results.

Preparation

Preparation refers to the steps taken to get ready for the future uses of the evaluation findings. The ability to translate new knowledge into appropriate action is a skill that can be strengthened through practice. In fact, building this skill can itself be a useful benefit of the evaluation. It is possible to prepare stakeholders for future use of the results by discussing how potential findings might affect decision making.

For example, primary intended users and other stakeholders could be given a set of hypothetical results and asked what decisions or actions they would make on the basis of this new knowledge. If they indicate that the evidence presented is incomplete or irrelevant and that no action would be taken, then this is an early warning sign that the planned evaluation should be modified. Preparing for use also gives stakeholders more time to explore both positive and negative implications of potential results and to identify different options for program improvement.

Feedback is the communication that occurs among everyone involved in the evaluation. Giving and receiving feedback creates an atmosphere of trust among stakeholders; it keeps an evaluation on track by keeping everyone informed about how the evaluation is proceeding. Primary intended users and other stakeholders have a right to comment on evaluation decisions. From a standpoint of ensuring use, stakeholder feedback is a necessary part of every step in the evaluation. Obtaining valuable feedback can be encouraged by holding discussions during each step of the evaluation and routinely sharing interim findings, provisional interpretations, and draft reports.

Follow-up refers to the support that many users need during the evaluation and after they receive evaluation findings. Because of the amount of effort required, reaching justified conclusions in an evaluation can seem like an end in itself. It is not . Active follow-up may be necessary to remind users of the intended uses of what has been learned. Follow-up may also be required to stop lessons learned from becoming lost or ignored in the process of making complex or political decisions. To guard against such oversight, it may be helpful to have someone involved in the evaluation serve as an advocate for the evaluation's findings during the decision -making phase.

Facilitating the use of evaluation findings also carries with it the responsibility to prevent misuse. Evaluation results are always bounded by the context in which the evaluation was conducted. Some stakeholders, however, may be tempted to take results out of context or to use them for different purposes than what they were developed for. For instance, over-generalizing the results from a single case study to make decisions that affect all sites in a national program is an example of misuse of a case study evaluation.

Similarly, program opponents may misuse results by overemphasizing negative findings without giving proper credit for what has worked. Active follow-up can help to prevent these and other forms of misuse by ensuring that evidence is only applied to the questions that were the central focus of the evaluation.

Dissemination