Are computer and information research scientists happy?

Computer and information research scientists are about average in terms of happiness.

At CareerExplorer, we conduct an ongoing survey with millions of people and ask them how satisfied they are with their careers. As it turns out, computer and information research scientists rate their career happiness 3.3 out of 5 stars which puts them in the top 42% of careers.

To put this into perspective, we compared how happy computer and information research scientists are to similar careers in the industry. Take a look at the results below:

Salaries and satisfaction ratings in similar careers

So what does it mean to be happy in your career? Let’s break it down into different dimensions:

- Salary: Are computer and information research scientists happy with their salary?

- Meaning: Do computer and information research scientists find their jobs meaningful?

- Personality fit: How well suited are people’s personalities to their everyday tasks as computer and information research scientists?

- Work environment: How enjoyable are computer and information research scientist’s work environments?

- Skills utilization: Are computer and information research scientists making the best use of their abilities?

Are computer and information research scientists happy with their salary?

Computer and information research scientists rated their satisfaction with their salaries 3.2/5 . Few are explicitly unhappy with their salaries, with most computer and information research scientists having generally positive views of their salary.

We asked computer and information research scientists how fairly compensated they are for their work. Their response was:

3.2 out of 5 stars.

73 computer and information research scientists

15% of computer and information research scientists rated their compensation 5 stars

25% of computer and information research scientists rated their compensation 4 stars

30% of computer and information research scientists rated their compensation 3 stars

19% of computer and information research scientists rated their compensation 2 stars

11% of computer and information research scientists rated their compensation 1 stars

Do computer and information research scientists find their jobs meaningful?

On average, computer and information research scientists rate the meaningfulness of their work a 3.1/5 . Most tend to be satisified with the level of meaning they find in their careers.

We asked computer and information research scientists how meaningful they found their work. Their response was:

3.1 out of 5 stars.

74 computer and information research scientists

19% of computer and information research scientists rated how meaningful they found their career 5 stars

26% of computer and information research scientists rated how meaningful they found their career 4 stars

20% of computer and information research scientists rated how meaningful they found their career 3 stars

22% of computer and information research scientists rated how meaningful they found their career 2 stars

14% of computer and information research scientists rated how meaningful they found their career 1 stars

How well are people’s personalities suited to everyday tasks as computer and information research scientists?

Computer and information research scientists rated their personality fit with their work an average of 3.6/5 . The majority of computer and information research scientists find their personalities quite well suited to their work, with relatively few having complaints about their fit.

We asked computer and information research scientists how well their personalities fit into their careers. Their response was:

3.6 out of 5 stars.

77 computer and information research scientists

31% of computer and information research scientists rated their career fit 5 stars

31% of computer and information research scientists rated their career fit 4 stars

18% of computer and information research scientists rated their career fit 3 stars

10% of computer and information research scientists rated their career fit 2 stars

9% of computer and information research scientists rated their career fit 1 stars

How enjoyable is a computer and information research scientist’s work environment?

As a whole, computer and information research scientists rated their enjoyment of their work environment 3.7/5 . A solid majority of computer and information research scientists enjoy their work environment, probably contributing to overall higher satisfaction with working as a computer and information research scientist.

We asked computer and information research scientists how much they enjoyed their work environment. Their response was:

3.7 out of 5 stars.

75 computer and information research scientists

25% of computer and information research scientists rated their work environment 5 stars

41% of computer and information research scientists rated their work environment 4 stars

19% of computer and information research scientists rated their work environment 3 stars

11% of computer and information research scientists rated their work environment 2 stars

4% of computer and information research scientists rated their work environment 1 stars

Are computer and information research scientists making the best use of their abilities?

Former computer and information research scientists on CareerExplorer have rated their skills utilization 3.4/5 . Most computer and information research scientists surveyed find that they manage to use their abilities to their fullest as a computer and information research scientist, which helps contribute to higher career satisfaction in the long term.

We asked computer and information research scientists how well their abilities were used in their careers. Their response was:

3.4 out of 5 stars.

22% of computer and information research scientists rated their how well their skills were utilized in their career 5 stars

30% of computer and information research scientists rated their how well their skills were utilized in their career 4 stars

25% of computer and information research scientists rated their how well their skills were utilized in their career 3 stars

17% of computer and information research scientists rated their how well their skills were utilized in their career 2 stars

6% of computer and information research scientists rated their how well their skills were utilized in their career 1 stars

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Job Satisfaction: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Analysis in a Well-Educated Population

Paolo montuori.

1 Department of Public Health, University “Federico II”, Via Sergio Pansini N° 5, 80131 Naples, Italy

Michele Sorrentino

Pasquale sarnacchiaro.

2 Department of Law and Economics, University “Federico II”, 80131 Naples, Italy

Fabiana Di Duca

Alfonso nardo, bartolomeo ferrante, daniela d’angelo, salvatore di sarno, francesca pennino, armando masucci, maria triassi, antonio nardone, associated data.

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Job satisfaction has a huge impact on overall life quality involving social relationships, family connection and perceived health status, affecting job performances, work absenteeism and job turnover. Over the past decades, the attention towards it has grown constantly. The aim of this study is to analyze simultaneously knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward job satisfaction in a general population in a large metropolitan area. The data acquired from 1043 questionnaires—administered to subjects with an average age of 35.24 years—revealed that only 30% is satisfied by his job. Moreover, among all the tested sample, 12% receive, or often receive intimidation by their superior, and 23% wake up unhappy to go to work. Marital status and having children seem to be an important factor that negatively influences job satisfaction through worst behaviours. The multiple linear regression analysis shows how knowledge is negatively correlated to practices; although this correlation is not present in a simple linear regression showing a mediation role of attitudes in forming practices. On the contrary, attitudes, correlated both to knowledge and practices, greatly affect perceived satisfaction, leading us to target our proposed intervention toward mindfulness and to improve welfare regulation towards couples with children.

1. Introduction

Job satisfaction has been defined as a “pleasurable or positive emotional state, resulting from the appraisal of one’s job experiences” [ 1 ]. Job satisfaction reflects on overall life quality involving social relationships, family connection and perceived health status, affecting job performances, work absenteeism and job turnover, leading, in some cases, to serious psychological condition such as burnout [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ].

The recent Gallup statistics on job satisfaction indicated that a very large portion of the world’s 1 billion full-time workers is disengaged, more precisely, only 15% of workers are happy and production in the workplace, the remaining 47% of workers are “not engaged,” psychologically unattached to their work and company [ 7 ]. In the EU, approximately one in five residents (16.9%) currently in employment expressed low levels of satisfaction with their job, on the other hand approximately one in four (24.6%) expressed high levels of satisfaction, the remaining residents (58.5%) declared medium levels of satisfaction with their job [ 8 ]. Characteristics such as age, sex, education, occupation, commuting time and difficulty as inadequate income, seems to be related to job satisfaction as they tent to influence expectation and preferences of individuals’ reflection on their perceived working condition [ 9 , 10 ]; however, as assessed in Eurofound, European Working Conditions Surveys [ 11 ] the relation between age and job satisfaction is very weak, although a slight increase in low satisfaction prevalence was found in elder population, it does not increase significantly with age even though expectations change during lifetime; educational attainment and income seem to play a significant role in job satisfaction as they grow in parallel, leading to better positions and a higher wages, along with power and more decisional autonomy. Sex is a factor as women seems to be overall more satisfied by their job in despite of the worst general conditions [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Job satisfaction also relates to marital status as single subjects’ results as the most satisfied by their work in some European Countries [ 15 ]. In Italy, the overall perceived job satisfaction seems to be similar to other regions in EU, and social relations as well as family composition appear to play a relevant role [ 16 ].

Job satisfaction has been studied mostly over a specific category of workers [ 17 , 18 ], as some types of works seems to be more related to pathological conditions such as burnout [ 19 , 20 ] and job-related stress [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]; however, as reported by those authors, this kind of selection method could lead to selection biases. According to van Saane [ 24 ], although many studies were carried as since Job Satisfaction broke out in the last 70’s as a central topic of interest, nor a mathematical instrument as reliable as desired nor a comparative method were found, usually those studies were based on single components of job satisfaction, taken out from extra working environment, and without analysing the consequences on behaviours in day life [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. The literature research demonstrated that practices are the results of knowledge, attitudes, or their interaction. The KAP Survey Questionnaire [ 28 ] can be applied to highlight the main features of knowledge, attitude, and practice of a person, and to assess that person’s views on the matter. The purpose, when using the KAP Survey Model, is to measure a phenomenon through the quantitative collection method of a large amount of data through the administration of questionnaires and then statistically process the information obtained. Through a questionnaire, however, seems to be easier to quantify job satisfaction. In addition to that, studying broader populations’ consent to explore different components, both personal and environmental, which concur to influence it [ 29 , 30 ].

In the recent literature, a KAP model was used only once to analyse behaviours toward job satisfaction. In his work, Alavi [ 31 ] conducted a survey based cross-sectional study on 530 Iranian radiation workers; although it comprehends simultaneously knowledge, attitude, and practices, it was conducted on a specific category of workers and on a narrower population. Therefore, since to the best of our knowledge none of the studies presented in the literature are carried out on a broader population relating both knowledge and attitudes to behaviours on job satisfaction, the aim of this study is to analyse simultaneously knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours toward job satisfaction in a large metropolitan area. It is important to investigate this phenomenon to evaluate the condition and develop health education programs and community-based intervention to increase job satisfaction and knowledge and positively orienting attitudes.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. participants and procedure.

This cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2021 to February 2022 in the large metropolitan area of Naples, southern Italy, among working places, universities, and community centres. No specific category of participants was selected. In the questionnaire, respondents indicated their occupation by choosing from the following options: lawyer, architect, engineer, doctor, accountant, entrepreneur, teacher, law enforcement, trader, student, employee, worker, unemployed, other. Table 1 shows the categories indicated by the participants. The criteria for inclusion in the study required that respondents of a general population were over 18 years old, belonging to one of the categories of employment listed in Table 1 , and resided in the metropolitan area of Naples. Every participant directly received a questionnaire (available upon request from the corresponding author) and at the time of filling out the questionnaire, the aim of the study and the anonymity and privacy of the data collecting method being used was explained, both in written form, as an introduction part of the questionnaire, and verbally to each of the participants. The questionnaire consisted of basic information about participants (age, gender, children, civil state, education level, profession, smoke habits) and three pools of questions divided in knowledge, attitudes and behaviours concerning their job satisfaction for a total number of 37 questions. The construction of the questionnaire was carried out as recommended by the KAP Model [ 28 ], briefly was divided into four phases: (1) Constructing the survey protocol; (2) Preparing the survey; (3) Course of the KAP survey in field; (4) Data analysis and presentation of the survey report. To develop the questionnaire, research questions based on the “Objectives of the study” were first carried out to develop the research questions, according to KAP Survey Model [ 28 ], the knowledge was considered as a set of understandings, knowledge, and “science” while Attitude as a way of being, a position. After, the research questions were reduced in number by removing those questions that require unnecessary information. When the above step is also done, the difficult questions have been changed/removed (closed questions have been used because one of the most important things that will increase the relevance of the questions is that the questions must be closed questions). Knowledge and attitudes were assessed on a three-point Likert scale with options for “agree”, “uncertain”, and “disagree”, while inquiries regarding behaviours were in a four-answer format of “never”, “sometimes”, “often”, and “yes/always”. A pilot study was also carried out to test the questionnaire and to verify the reliability of questions. Finally, all the collected questionnaires were digitalized submitting the codified answers in an Excel worksheet (MS Office).

Study population characteristics.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Data reported by the study were analysed using IBM SPSS (vers. 27) statistical software program. The analysis was carried out in two stages. In the first stage, a descriptive statistic was used to summarize the basic information of the statistical units. In the second stage, a Multiple Linear Regression Analysis (MLRA) was used to model the linear relationship between the independent variables and dependent variable.

The dependent variables (Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours) had been obtained by adding the scores obtained in the corresponding questions (questions with inverse answers have been coded inversely). The independent variables were included in all models: sex (1 = male, 2 = female); age, in years; education level (1 = primary school, 2 = middle school, 3 = high school, 4 = university degree); civil state (1 = Single; 2 = In a relationship; 3 = Married; 4 = Separated/Divorced; 5 = Widowed).

The main results from a MLRA contains the statistical significance of the regression model as well as the estimation and the statistical significance of the beta coefficients ( p -value < 0.05) and the coefficient of determination (R-squared and adjusted R-squared), used to measure how much of the variation in outcome can be explained by the variation in the independent variables. Three MLRA were developed:

- (1) Knowledge about job satisfaction (Model 1);

- (2) Attitudes toward resilience and mindfulness (Model 2);

- (3) Actual behaviours regarding Job and Job-related life (Model 3).

In Model 2, we added Knowledge to the independent variables, and in Model 3, we added Knowledge and Attitudes to the independent variables. In the analysis, we considered Attitudes and Knowledge as indexes rather than a scale, which means that each observed variable (A1, …, A13 and K1, …, K12) is assumed to cause the latent variables associated (Attitude and Knowledge). In other terms, the relationship between observed variables and latent variables is formative. Therefore, inter-observed variables correlations are not required. On the contrary, the relationship between the observed variables (B1, …, B14) and latent variable Behaviour could be considered reflective (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.825). All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the results were statistically significant if the p -values were less than or equal to 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

Out of the 1057 participants, 1043 anonymous self-report surveys were returned, resulting in a response rate of 98.7%. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population: the mean age of the study population is 35.24 years; in 18–70 age range, the main group of distribution was 18–30 representing 44.6% of the sample; sex distribution shows that: 427 are men, 616 are woman. A large majority (73.5%) does not have children, while 26.5% of the sample has them. Most of the participants have a post graduate degree, while 29.1% are high school graduates. Among them, 22.2% are physicians, 15.1% teachers and 14.0% students ( Table 1 ).

Respondent’s knowledge about job satisfaction is presented in Table 2 . While a large majority of the sample population (91.7%) has a well-defined knowledge about job satisfaction main characteristics such as mains definitions, both of work-related stress and mobbing, most of them does not know or are not aware which risks are specifically related as only 31.4% knows that job related stress and mobbing are a threat to their cardiovascular health. Only 28.7% of the population knows that “Only 15% of worker, globally, are satisfied by their work” demonstrating that while knowledge regarding job related stress is well spread, the sample does not know how diffused it is and what kind of risks it involves, and that state provide a compensation for job related stress.

Knowledge of respondents toward job satisfaction.

* INAIL: Istituto Nazionale Assicurazione Infortuni sul Lavoro (National Institute for Occupational Accident Insurance).

In Table 3 are described attitudes toward job satisfaction. Most of the participants think that working out is relaxing and spending time is regenerating, showing a good attitude to copy with work related stress. According to 93.4% of the sample, workload plays a key role in job satisfaction, as well as adequate wages and a clear task schedule. Several studies have enlightened that when workers lack a clear definition of the tasks which are necessary to fulfil a specific role, their levels of job satisfaction are likely to be negatively affected [ 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Interestingly, most of the population sees challenges as a motivation to do better (80.2%) and are motivated by career opportunities (90.7%); however, 50.5% of the population has a negative attitude about changes. In confirmation of that, when asked if “Changes lead to stress”, only a small fraction of the sample (14.6%) disagreed. This allowed us to assume that, although most of the population sees problems as an opportunity to learn, improve and progress in their work, they are aware of the difficulties connected to changing scenarios. About 27.2% of the sample does not have a positive attitude toward sharing their feeling about problems at work talking out loud. Bad interpersonal relationships with co-workers are another reason for job dissatisfaction. Poor or unsupportive relationships and conflicts with colleagues and/or supervisors lead to negative psychological intensions, resulting in job dissatisfaction [ 35 , 36 ].

Attitude of respondents toward job satisfaction.

Behaviours of respondents are listed in Table 4 : A consistent part of the sample responded positively to the group of question toward behaviours regarding their coping level of stressful situation (B2, B4, B8, B9, B10) showing a reported good resilience. Commuting seems to be a problem for at least a third of the sample, also in a metropolitan area served by 2 subways, full bus service, car sharing services and a speedway. Job satisfaction is associated negatively with constraints such as commuting time. This dead time, mostly unpaid, is mandatory for workers to reach workplace. Although this is not considered as working time, and only a specific class is refunded, from the employers’ perspective, it is time dedicated to work and a strong determinant for low satisfaction levels. EU workers were much more likely to be highly (37.9%) or moderately satisfied (41.7%) with their commuting time compared to their job satisfaction. Most of the sample responded to not having experienced mobbing; although even a “low” result, such as a cumulative, summing both “yes/always” and “often”, of 11.8% is alarming and pushes us to study more about this phenomenon. Interestingly, 30.9% of respondents are satisfied about their work, reaching a total of 59.5%. In addition, with a “often” response showing a large appreciation of their jobs, 22.9% of the respondents “wake up unhappy to go to work”, and feel “stuck in a job with no career opportunities” (27.7%). The sample has no problems managing their work and social life (48.3%); however, only a complex of 35% of the sample usually spend their time with colleagues outside the office.

Behaviour of respondents toward job satisfaction.

Table 5 illustrates results of linear multiple regression in three models: in Model I Knowledge, as dependent variable, correlate, with a p -value < 0.001; with “sex”, interestingly, woman seem to have a higher overall score of knowledge in disagreement with Gulavani [ 37 ] whose study was conducted among a sample of nurses and found no significant relation between sex and knowledge on job satisfaction. Al-Haroon [ 38 ] evidenced that among health workers, men had a better overall level of knowledge. These results, however, were collected over specific categories of employees, in a narrower sample; whereas our study was represented by a general population of a metropolitan area. No statistically significant correlation between knowledge and age, civil status, children, and education levels was encountered.

Results of the linear multiple regression.

Previous research asses that attitude plays a key a role in job satisfaction, as some attitudinal characteristics of the subject influence perspective, coping skills and stressful situation management [ 39 , 40 , 41 ]. In Model II ( Table 5 ) we correlated, through MLRA, attitudes with age, sex, civil state, having children, education, and overall knowledge score. With a p -value < 0.001, two correlations were found with education and overall knowledge score, both positively. Those results reflect, in accordance with Alavi [ 31 ], who found that higher level of education was among 3 factors that predicted job satisfaction and attaining a higher university degree compared to lower degrees contributes to a feeling of coherence, success at work, personal growth and self-respect, self-realization and intrinsic motivation, that education level and therefore a higher level of knowledge contributes to generating a sense of job satisfaction. In the questionnaire we tried to collect all those propension and as a result: in agreement with Hermanwan [ 42 ], Andrews [ 43 ] and Choi [ 44 ], subjects with better knowledge and high levels of education tent to have better attitudes.

In Model III, behaviours taken as a dependent variable are correlated to age, sex, civil state, children, education, knowledge, and attitudes. The results of linear multiple regression in this model assess that behaviours are negatively correlated to civil state, sons, and knowledge, and positively correlated to attitudes. Our findings show that there is a positive correlation between behaviours and attitudes, in agreement with previous literature [ 45 , 46 , 47 ], demonstrating that people with better attitudes tent to have a better overall behaviour. Surprisingly, in Model III, knowledge also has a statistically significant correlation to behaviours but in a negative way. This correlation, however, is not present when we correlate those variables alone in a Pearson’s correlation between knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours ( Table 6 ). This evidence, therefore, suggests that attitude mediates the effect of knowledge on behaviours, assessing an important relation between those two determinants. People with a better overall score in behaviours tend to have a higher score in knowledge and attitude. In this sample, those who have a lower score in knowledge also has a higher behaviour score in accordance with a part of the previous literature [ 48 , 49 ]. This enlightens the importance of high levels of knowledge in order to form better attitudes in the pursuit of job satisfaction. Civil state and having children seem to play a key role in performing a better behaviour about job satisfaction; which is also evident in one specific question about behaviour: Question “B14” enlightens the social practices of subjects with colleagues outside the work environment, and the statistical analysis on this topic shows that subject with a more stable sentimental situation or with child tend to hang out with their colleagues less, likely worsening their relationships at work and getting a worse overall behaviour score and worse attitude toward the topic in agreement with Sousa-Poza [ 50 ] and Armstrong [ 51 ]. Job satisfaction has a strong correlation to family characteristics: Subjectst who have families with children have less positive behaviours towards their job satisfaction, directly affecting their overall behaviour score; this evidence is in contrast with Alavi [ 31 ], who states that job satisfaction is positively affected by family, assessing that “married employees have opportunities to receive support or advice from their family to mediate job conflicts,” Although he admits that in the literature, this result is controversial as some authors, such as Clark [ 52 ], found that “married employees experienced a higher level of job satisfaction than their unmarried co-workers”, and Booth and Van Ours’ [ 53 ], study did not find a statistically relevant correlation with the presence of children. Those results, therefore, suggest creating targeted educational programs, community-based intervention, and legal regulation, to improve self-awareness and resilience among workers, and a more practical intervention could be directed to families with child.

Pearson’s correlation between knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours.

4. Conclusions

This study shows that the metropolitan population has general good knowledge about job satisfaction as well as a positive attitude. Job satisfaction, however, is reflected accordingly only with attitudes. While it has a negative relation to civil state and having children, this means that the experimental results of this study may be used to create targeted educational programs, community-based intervention, and legal regulation, to improve self-awareness and resilience among workers. A more direct intervention could be directed to families with children. Social networking with colleagues has an important impact on job satisfaction, as the part of the sample who responded positively to the specific question, had an overall better behaviour. Although, in this case, having children seems to be, as they negative correlate, a huge limitation to this practice. Considering that, as previously stated, the impact of job satisfaction on the population has a strong impact in terms of life balance, health, and economics, and it is well known that only a small fraction of workers are fully satisfied. It might be important to promote welfare regulation to allow a larger part of the population to conciliate work and family. Results of this paper could be an indicator of how to establish an educational program more efficiently. It is mandatory to strengthen specific knowledge about job satisfaction through the general population toward the importance of job satisfaction and the benefits related to a correct approach to work-life. The impact of a public health intervention could be even more effective by integrating another program to orient and define attitudes, which in turn will influence people to practice a mindfulness mental setting toward job satisfaction. In conclusion, a training program based on fundamental practices of job satisfaction should be improved in the young population, in early stage of family life, or before they have children, in order to achieve a double objective: “training family and spreading the practice to a future generation”.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

Data curation: P.M., M.S., P.S., F.D.D., A.N. (Alfonso Nardo), B.F., D.D., S.D.S., F.P., A.M. and M.T.; Formal analysis: M.S., F.D.D., A.N. (Alfonso Nardo), B.F., D.D., S.D.S. and F.P.; Resources: P.M. and M.T.; Software: P.S.; Supervision, P.M., M.T. and A.N. (Antonio Nardone); Writing—original draft: M.S., F.D.D., A.N. (Alfonso Nardo), B.F., D.D. and S.D.S.; Writing—review and editing: P.M., M.S., P.S., F.P., A.M., M.T. and A.N. (Antonio Nardone). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

National Science Foundation - Where Discoveries Begin

- Biological Sciences (BIO)

- Computer and Information Science and Engineering (CISE)

- Education and Human Resources (EHR)

- Engineering (ENG)

- Environmental Research and Education (ERE)

- Geosciences (GEO)

- Integrative Activities (OIA)

- International Science and Engineering (OISE)

- Mathematical and Physical Sciences (MPS)

Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences (SBE)

- Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP)

- Related Links

- Interdisciplinary Research

- NSF Organization List

- Responsible and Ethical Conduct of Research

- Staff Directory

- Understanding NSF Research

- About Funding

- Archived Funding Search

- Find Funding

- Merit Review

- Policies and Procedures

- Preparing Proposals

- Recent Opportunities

- Transformative Research

- Proposal and Award Policies and Procedures Guide (PAPPG)

- Research.gov

- Funding Opportunities For

- Graduate Students

- K-12 Educators

- Postdoctoral Fellows

- Undergraduate Students

- Small Business

- About Awards

- Award Statistics (Budget Internet Info System)

- Award Conditions

- Managing Awards

- Presidential and Honorary Awards

- Search Awards

- Public Access Initiative

- All Documents

- National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES)

- Obtaining Documents

- Search Documents

- For News Media

- Multimedia Gallery

- News Archive

- Search News

- Special Reports

- Speeches and Lectures

- About NSF Logo

- Broadening Participation/Diversity

- Budget and Performance

- Career Opportunities

- Contracting Opportunities

- National Science Board (NSB)

- NSF and Congress

- NSF Toolkit

- Office of Equity and Civil Rights

- Organization List

- Remote Participant Support

- Transparency and Accountability

- Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences (SBE) Home

- Behavioral and Cognitive Sciences (BCS)

- About NCSES

- Schedule of Release Dates

- Corrections

- Social and Economic Sciences (SES)

- SBE Office of Multidisciplinary Activities (SMA)

- Get NCSES Email Updates Get NCSES Email Updates Go

- Contact NCSES

- Research Areas

- Share on X/Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Send as Email

Replicating the Job Importance and Job Satisfaction Latent Class Analysis from the 2017 Survey of Doctorate Recipients with the 2015 and 2019 Cycles

Working papers are intended to report exploratory results of research and analysis undertaken by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this working paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation (NSF). This working paper has been released to inform interested parties of ongoing research or activities and to encourage further discussion of the topic and is not considered to contain official government statistics.

This research was completed while Dr. Fritz was on academic leave from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and participating in the NCSES Research Ambassador Program (formerly the Data Analysis and Statistics Research Program) administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) and Oak Ridge Associate Universities (ORAU). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this working paper are solely the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of NCSES, NSF, ORISE, or ORAU.

Replication and reproducibility of results is a cornerstone of scientific research, as replication studies can identify artifacts that affect internal validity, investigate sampling error, increase generalizability, provide further testing of the original hypothesis, and evaluate claims of fraud. The purpose of the current working paper is to determine whether the five-class, three-response latent class solutions for job importance and job satisfaction found by Fritz (2022) using the 2017 cycle of the Survey of Doctorate Recipients data replicate using data from the 2015 and 2019 cycles. A series of latent class analyses were conducted using the Mplus statistical software, which determined that the five-class, three-response solutions for job importance and job satisfaction were also the best models for the 2015 and 2019 data. In addition, the class prevalences and response probabilities were highly consistent across time, indicating that the interpretation of the latent classes is the same across time as well. All of this gives strong evidence that the 2017 results were successfully replicated in the 2015 and 2019 data, increasing confidence in the original results and also setting the stage for a future longitudinal investigation of the latent classes using latent transition analysis.

Introduction

Background and rationale.

Replication and reproducibility are central tenets of science and scientific inquiry. Put simply, replication is the idea that if it is possible to carry out a research study more than once, then any person who exactly follows the same research protocol as the original study should (within a small margin of error) find the same results as the original study (Fidler and Wilcox 2018), whereas reproducibility is the idea that two people analyzing the same data using the same statistical methods should get the same results. While the concepts of scientific replication and reproducibility are simple, in practice, replication studies often completely or partially fail to replicate the results of previously published scientific studies, leading some to talk about a “replication crisis” in science (Fidler and Wilcox 2018; Pashler and Wagenmakers 2012) or state more strongly that, “It can be proven that most claimed research findings are false” (Ioannidis 2005). Fidler and Wilcox (2018) argue that this “replication crisis” is caused by five interrelated characteristics of the current scientific publication process: (1) the rarity of published replication studies in many fields, (2) the inability to reproduce the statistically significant results of many published studies, (3) a bias towards only publishing scientific studies that report statistically significant effects, (4) a lack of transparency and completeness with regard to sampling and analyses in published studies, and (5) the use of “questionable research practices” such as p hacking in order to obtain significant results. In the U.S. federal statistical system, issues with transparency and reproducibility are important enough that the NCSES tasked the Committee on National Statistics, part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, to produce a consensus study report on the topic (NASEM 2021).

Regardless of the reason, many replication studies fail to reproduce the results of the original study; a consequence of increased focus on replicability is an increased emphasis on the need to reproduce the results from any individual study through the use of one or more replication studies, especially in the social sciences. In general, replication studies fall into two categories: exact replications, which seek to exactly replicate a prior study, and conceptual replications, which seek to determine whether the results of the original study generalize to a new population or context. Regardless of whether a replication study is exact or conceptual, Schmidt (2009) lists five functions of replications studies: (1) control for fraud, (2) control for sampling error, (3) control for artifacts that affect internal validity, (4) increase in generalizability, and (5) further testing of the original hypothesis. In the context of longitudinal survey work, the replication of results at multiple time points increases confidence in the original results and decreases the likelihood that the results at any individual point in time are due solely to artifacts specific to that time point or due to sampling error and measurement error. This increase in confidence, in turn, increases the generalizability of the original results. Ignoring for the moment cases of explicit fraud or data entry and analytic errors, failure to replicate the findings from data collected at one point in time at another point in time could be an indicator of time-specific artifacts or that the effect of interest is changing over time, both of which would require a deeper investigation of the longitudinal structure of the data as a whole.

The purpose of the current working paper is twofold. First is to determine whether the results from Fritz (2022), who found five latent job importance classes and five latent job satisfaction classes using the 2017 cycle of the Survey of Doctorate Recipients (SDR), replicate with the 2015 and 2019 cycle data. Specifically, this paper seeks to rule out the possibility that the results from Fritz (2022) were caused solely by time-specific artifacts (and to a lesser extent, sampling and measurement error) that affected only the 2017 data collection in order to increase confidence in and generalizability of the results of the original study. Second is to lay the groundwork for a future working paper investigating whether individuals move between latent job importance and job satisfaction classes across time (and if so, who moves between classes and in what direction) using latent transition analysis (LTA). Because the first step in conducting an LTA is to determine the latent class structure at each time point, this replication study also fulfills this requirement.

Participants

Survey questions, analyses and software.

The current working paper uses the publicly available microdata from the 2015, 2017, and 2019 cycles of the SDR; information about inclusion criteria and sampling are provided in the supporting documentation for the public use files (NCSES 2018, 2019, 2021). To participate in a specific SDR cycle, individuals must have completed a research doctorate in a science, engineering, or health (SEH) field from a U.S. academic institution prior to 1 July two calendar years previous to the current cycle year (e.g., prior to 1 July 2017 for the 2019 cycle). Participants must also be less than 76 years of age and not institutionalized or terminally ill on 1 February of the cycle year. All individuals who were selected to participate in a specific cycle and continued to meet the inclusion criteria were eligible to participate in later cycles, with each cycle’s sample supplemented by individuals who had graduated since the previous cycle. For the 2019 cycle, individuals who did not respond to either the 2015 or 2017 cycles were removed, while 14,564 individuals eligible but not selected for the 2015 cycle were added, and a new stratification design that strengthened reporting for minority groups and small SEH degree fields was utilized. For the final data set of each cycle, missing values were imputed using both logical and statistical methods, and sampling weights were calculated to adjust for the stratified sampling schema; unknown eligibility; nonresponse; and demographic characteristics including gender, race and ethnicity, location, degree year, and degree field.

Only participants who were asked to respond to the job importance and job satisfaction questions for each cycle were included in the current paper, resulting in final sample sizes of 78,286 individuals for the 2015 cycle, 85,720 individuals for the 2017 cycle, and 80,869 individuals for the 2019 cycle. Table 1 contains the sampling weight–estimated population frequencies by year for gender, physical disability, race and ethnicity, age (in 10-year increments), degree area, whether the participant was living in the United States at the time of data collection, workforce status, and employment sector. Note that these values are based on the reduced samples used for the current analyses and should not be considered official statistics. Although there are some differences across time, in general, the population remained relatively stable in regard to demographics, with the majority of SEH doctoral degree holders for all three cycles identifying as male, White, employed, holding a degree in science, and reporting no physical disability.

Population estimates of Survey of Doctorate Recipients participant characteristics, by selected years: 2015, 2017, and 2019

The values presented here are provided for reference only as they are based on applying the sampling weights to the reduced samples for each collection cycle used for the current project (2015: n = 78,286; 2017: n = 85,720; 2019: n = 80,869) and therefore do not match the official values reported by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. All participants who identified as Hispanic were included in the Hispanic category, and only in the Hispanic category, regardless of whether they also identified with one or more of the racial categories. The Other category included individuals who identified as multiracial.

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Doctorate Recipients, 2015, 2017, and 2019.

The current working paper focuses on two SDR questions: “When thinking about a job, how important is each of the following factors to you?” and “Thinking about your principal job held during the week of February 1, please rate your satisfaction with that job’s….” For each question, the participants were asked to rate nine job factors on a 4-point response scale. As in the final models for Working Paper NCSES 22-207 (Fritz 2022), the “somewhat unimportant” and “not important at all” options were combined into a single “unimportant” category and the “somewhat dissatisfied” and “very dissatisfied” options were combined into a single “dissatisfied” category resulting in three response categories for each question. Table 2 shows the sampling weight–estimated population response rates for the three response options for each of the nine job factors for importance and satisfaction. As with Table 1 , these values are based on the reduced samples used for the current analyses and should not be considered official statistics. Despite some small variability across time, in general, the response rates for each response option for each job factor were remarkably similar for all three cycles.

Population estimates of response proportions in percentages for importance of and satisfaction with nine job-related factors, by selected years: 2015, 2017, and 2019

The values presented here are provided for reference only as they are based on applying the sampling weights to the reduced samples for each collection cycle used for the current project (2015: n = 78,286; 2017: n = 85,720; 2019: n = 80,869) and therefore do not match the official values reported by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Latent Class Analyses

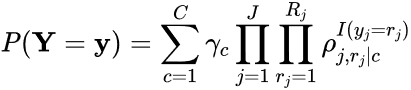

The current paper uses latent class analysis (LCA), which has the mathematical model (Collins and Lanza 2010)

where J is the number of indicators (i.e., job factors, so J = 9), R j is the number of response options for indicator j (here, R j = 3), C is the number of latent classes, γ c is the prevalence of class c , and ρ j,r j | c is the probability of giving response r j to indicator j for a member of class c . While previous work (Fritz 2022) has indicated that there are five job importance latent classes and five job satisfaction latent classes, given that the purpose of the current analyses is to test the veracity of this prior work, multiple models with differing numbers of latent classes were estimated and compared, and the correct number of classes to retain was based on four criteria: (1) percentage decrease in adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC) value when an extra latent class was added, (2) solution stability across 1,000 random starts, (3) model entropy, and (4) interpretability of the latent classes.

Sampling weight–estimated population frequencies were computed using PROC SURVEYFREQ with the WEIGHT option in SAS 9.4 (SAS 2021). All LCA models were estimated with Mplus 8.4 (Muthèn and Muthèn 2021) using the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors estimator, treating the indicators as ordered categories (CATEGORICAL) and using 1,000 random starts, each of which was carried through all three estimation stages (STARTS ARE 1000 1000 1000;). Note that while Mplus and PROC LCA (Lanza et al. 2015) give almost identical results (e.g., the results from the 2017 five-class, three-response job importance LCA model in Mplus were identical to the same model in PROC LCA to at least three decimal places), Mplus calculates the aBIC based on the loglikelihood whereas PROC LCA calculates the aBIC based on the G 2 statistic, which changes the scaling of the aBIC values. As such, all LCA results for the 2017 SDR cycle reported here have been rerun in Mplus to put the 2017 model aBIC values on the same scale as the 2015 and 2019 model values.

Latent Classes: Job Importance

Latent classes: job satisfaction.

All LCA models with between one and eight latent classes were fit to the 9 three-response job importance factors separately for the 2015, 2017, and 2019 cycles of SDR data. All models converged normally, although not all 1,000 random starting values converged for the seven- and eight-class models. Table 3 contains the aBIC, percentage decrease in aBIC between models with C + 1 and C classes, entropy, and stability values for each model by year. As described previously, the aBIC values for the 2017 cycle do not match the values from Fritz (2022) because Mplus computes the aBIC values using the loglikelihood rather than G 2 . Table 3 reveals high consistency in model fit across years. These values indicate that the five-class solution fits the best for all three cycles. For example, adding an additional class reduces the aBIC value by 1.2% or more up through five classes, but adding a sixth latent class only reduces the aBIC value by 0.5% or less for each cycle. In addition, the stability for the five-class solution is highest of the four- through eight-class solutions for all three cycles, and the stability drops substantially for models with more than five classes while the entropy values stay approximately the same.

Model fit indices for job importance latent class analysis models, by selected years: 2015, 2017, and 2019

aBIC = adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion.

Stability is based on 1,000 random starts unless denoted with an asterisk (*), which indicates that not all 1,000 starts converged. When one or more starts failed to converge, stability is based on the number of starts out of 1,000 that did converge. The preferred 5-class solution is shown in bold.

The next step is to investigate the interpretation of the five-class solution for the 2015 and 2019 cycles as it is possible that there are five latent classes for each cycle, but that the interpretation of one or more classes is different in the 2017 cycle than the other cycles. The prevalence (i.e., estimated percentage of the population) for each class, as well as the response probabilities for each job factor, of the five-class, three response LCA model are shown in Table 4 by year. As with the previous tables, while the prevalances and response probabilities are not identical for each cycle, Table 4 shows a high level of consistency across years. The largest class for all three cycles is the Everything I s Very Important class whose members have a high probability of rating all nine job factors as “very important.” The second largest class for all three cycles is the Challenge and Independence A re More Important T han Salary and Benefits class whose members are most likely to rate a job’s intellectual challenge, level of independence, and contribution to society as “very important” and the job’s salary and benefits as only “somewhat important.” The Benefits and Salary A re More Important T han Responsibility class is the third largest class for all three cycles, and its members are mostly likely to rate a job’s salary, benefits, and security as “very important” and the job’s level of responsibility as “somewhat important.” The fourth largest class for all three cycles is the Everything I s Somewhat Important class whose members are most likely to rate all nine job factors as “somewhat important.” And the smallest class for each cycle is the Advancement, Security, and Benefits A re Unimportant class whose members are mostly likely to rate a job’s benefits, security, and opportunity for advancement as “unimportant,” although members of this group are likely to rate the job’s location as “very important.” Note that this smallest class is always larger than the 5% rule of thumb for retaining a class (Nasserinejad et al. 2017). Based on this, the five-class, three-response job importance solution reported by Fritz (2022) for the 2017 SDR data does replicate with the 2015 and 2019 cycles of the SDR.

Five-class job importance latent class analysis solution with three response options, by selected years: 2015, 2017, and 2019

Probabilities may not sum to 1.000 due to rounding. Response probabilities greater than or equal to 0.500 are considered salient and are represented in bold. Response probabilities more than twice as large as the next largest probability for that item for a specific year are highlighted in blue.

All LCA models with between one and eight latent classes were fit to the 9 three-response job satisfaction factors separately for the 2015, 2017, and 2019 cycles of SDR data. All models converged normally; again, a small percentage of the 1,000 random starting values did not converge, although just for the eight-class model. Table 5 shows the aBIC, percentage decrease in aBIC between models with C + 1 and C classes, entropy, and stability values for each model by year. As with the model fit indices for job importance, there is a high level of consistency in model fit across cycles for job satisfaction, and stability was 72.2% or higher for the one- through six-class solutions. Unlike the job importance models, however, adding a fifth class reduced the aBIC value by less than 1% for the job satisfaction models. It is important to remember that the decision to include the fifth job satisfaction class in Fritz (2022) was based more on the increased interpretability of the five-class solution compared to the four- and six-class solutions than the improvement in model fit. That is, while inclusion of the fifth class increased model fit modestly, the fifth class improved the separation of the other four classes, making them easier to interpret.

Model fit indices for job satisfaction latent class analysis models, by selected years: 2015, 2017, and 2019

Investigating the response probabilities and prevalences of the five-class model, shown in Table 6 , reveals that the interpretation of the five-class solution is identical for the 2015, 2017, and 2019 cycles, although the rank order of the smaller classes does vary (note that the order of classes in Table 6 is based on the 2017 prevalences). The largest class for all three cycles is the Very Satisfied W ith Independence, Challenge, and Responsibility class whose members are most likely to rate their satisfaction with their job’s level of independence, intellectual challenge, level of responsibility, and contribution to society as high but are less satisfied with their salary, benefits, and opportunities for advancement. The second largest class for all three cycles is the Very Satisfied W ith Everything class whose members report being very satisfied with all facets of their current job. While the three smaller classes vary in terms of rank, most likely due to sampling error as the prevalences for these three classes are very similar, the classes themselves are the same across time. Members of the Very Satisfied W ith Benefits class are most likely to rate their satisfaction with their job’s benefits, salary, and security as “very satisfied,” but only rate their satisfaction with their opportunity for advancement and level of responsibility as “somewhat satisfied.” Members of the Dissatisfied W ith Opportunities F or Advancement class are defined by their high probability of being dissatisfied with their opportunities for advancement in their current job. And the Somewhat Satisfied W ith Everything class members are mostly likely to rate their satisfaction with all of their job’s facets as “somewhat satisfied.” Based on these results, the five-class, three-response solution was determined to be the correct model for the 2015 and 2019 data, and, as a result, the five-class, three-response job satisfaction solution reported by Fritz (2022) for the 2017 SDR data does replicate with the 2015 and 2019 cycles of the SDR.

Five-class job satisfaction latent class analysis solution with three response options, by selected years: 2015, 2017, and 2019

There are three major take-aways from the results presented here. First, the replication was successful. As shown in Table 3 and Table 5 , the fit of the various LCA models is very similar across time, and Table 4 and Table 6 show that the prevalences and response probabilities (and hence, the interpretation) of the latent classes in the 2017 five-class solutions are almost identical to those for the 2015 and 2019 cycles for both job importance and job satisfaction. Perhaps this is unsurprising given the very similar response rates for each cycle shown in Table 2 , but all of this indicates that the five-class, three-response LCA solutions for the 2017 SDR data reported by Fritz (2022) do replicate for both job importance and job satisfaction in the 2015 and 2019 cycles of the SDR. While the replication of these five-class solutions provides evidence that these models were not selected solely due to an artifact of the 2017 SDR data, it is important to note that replicating the 2017 results with the 2015 and 2019 data does not rule out all alternative explanations. For example, because the SDR employs a longitudinal, repeated-measures design, with many of the doctoral degree holders who participated in the 2015 cycle also participating in the 2017 and 2019 cycles, it is possible the replication results are due to sampling error, and a different solution would be found with a different sample of doctoral degree holders. In addition, the replication says nothing about whether these five importance and five satisfaction classes are absolute in the sense that what doctoral degree holders in the latter half of the 2010s view as important, and their satisfaction with those job factors may not be the same as for doctoral degree holders in the 1980s or the 2040s. Regardless, replicating the 2017 results strengthens the validity and the generalizability of the original findings (Schmidt 2009).

Second, the replication highlights several findings from Fritz (2022) that, while reported in the original paper, were not as apparent until the results from the 2015, 2017, and 2019 cycles were considered together. For example, for all three cycles, over 70% of respondents were mostly likely to rate opportunities for advancement as “somewhat important” or “unimportant” ( Table 4 , Classes 2, 3, 4, and 5), but less than 30% of respondents were most likely to rate their satisfaction with their opportunities for advancement at their current job as “very satisfied” ( Table 6 , Class 2). This would indicate that most respondents were likely to believe their opportunities for advancement at their current job could be improved, and an important area of future research could be investigating why most doctoral degree holders feel this way and what would need to change in order for them to be very satisfied with their opportunities for advancement at their current job.

Another result that stands out in the replication concerns the job location. Table 4 shows that for all three cycles, over 85% of respondents were most likely to rate a job’s location as “very important” (Classes 1, 2, 3, and 5—only members of Class 4 are mostly likely to rate location as “somewhat important”), indicating that job location does not follow the intrinsic or extrinsic divide found by Fritz (2022) for Classes 2 and 3. The same pattern is seen in Table 6 for job satisfaction with members of Class 1, who are mostly likely to rate their satisfaction with only their job’s intrinsic facets as very high, and members of Class 3, who are mostly likely to rate their satisfaction with only their job’s extrinsic facets as very high, both being most likely to rate their satisfaction with their current job’s location as “very satisfied.” This would suggest that a job’s location is neither intrinsic nor extrinsic (or is somehow both). It is also possible that different respondents are interpretating the term “location” differently, with some conceptualizing location as country or state and others conceptualizing job location as a specific neighborhood or distance from their residence (e.g., length of daily commute). As with advancement, future research on doctoral degree holders could seek to better understand how job location relates to satisfaction.

Third, and finally, since the replication involved additional time points using the same sample, some potential longitudinal effects can be examined. For example, the size of some classes appears to systematically change over time, especially for job satisfaction. Most notably, the prevalence of the Satisfied W ith Independence, Challenge, and Responsibility (Class 1), Dissatisfied W ith Opportunities F or Advancement (Class 4), and Somewhat Satisfied W ith Everything (Class 5) classes all decrease from 2015 to 2019, whereas the size of the Satisfied W ith Everything (Class 2) and Satisfied W ith Benefits (Class 3) classes increase with each additional SDR cycle. While it is tempting to interpret this apparent trend to mean that overall job satisfaction is increasing or that average salary and benefits for doctoral degree holders is increasing, interpreting longitudinal effects in this replication study is problematic for several reasons. The most important issue is that the LCA models presented here do not model or statistically test any longitudinal hypotheses. As noted by Kenny and Zautra (1995), any individual’s score at a specific point in time in repeated-measures data is made up of three types of variability: trait, state, and error. Traits remain stable or change systematically across time; states are nonrandom, time-specific deviations from a trait; and errors are random deviations from a trait. For example, someone who has been in the same job for 10 years might be generally very satisfied with their current job for all 10 years (trait) but was dissatisfied on the day they filled out the SDR because they had an argument with a coworker the previous day (state) and selected “somewhat dissatisfied” because there was no “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied” response option (error).

Longitudinal models that can distinguish between trait, state, and error variability are therefore necessary to test and make conclusions about longitudinal effects. In more exact terms, while the replication of the 2017 solutions with the 2015 and 2019 data indicates that job importance and job satisfaction exhibit a high level of equilibrium that resulted in the same LCA solution at each time point, the replication does not provide any evidence for stability or stationarity of job satisfaction or importance across time. In this context, equilibrium is the consistency of the patterns of covariances and variances between items at a single point in time across repeated measurements (Dwyer 1983), while stability is the consistency of the mean level of a variable across time, and stationarity refers to an unchanging causal relationship between variables across time (Kenny 1979). Investigating whether the average level of satisfaction changed across time or whether the way in which satisfaction changed across time (i.e., the trajectory) differed by latent class would require the use of a latent growth curve model or a growth mixture model, respectively. In addition, the replication does not provide any insight into whether individuals tend to stay in the same class across time or whether individuals change classes, which would require the use of a latent transition model. Based on this, there are numerous longitudinal hypotheses that could be tested in order to gain a more complete understanding of the latent job importance and job satisfaction classes for doctoral degree holders.

Collins LM, Lanza ST. 2010. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis for Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Dwyer JH. 1983. Statistical Models for the Social and Behavioral Sciences . New York: Oxford University Press.

Fidler F, Wilcox J. 2018. Reproducibility in Scientific Results. In Zalta EN, editor, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Available at https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scientific-reproducibility/#MetaScieEstaMoniEvalReprCris .

Fritz MS; National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). Job Satisfaction versus Job Importance: A Latent Class Analysis of the 2017 Survey of Doctorate Recipients. Working Paper NCSES 22-207. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation. Available at https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2022/ncses22207/ .

Ioannidis JPA. 2005. Why Most Research Findings Are False. PLoS Medicine 2(8):e124. Available at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124 .

Kenny DA. 1979. Correlation and Causality . New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Kenny DA, Zautra A. 1995. The Trait-State-Error Model for Multiwave Data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 63(1):52–59. Available at https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.52 .

Lanza ST, Dziak JJ, Huang L, Wagner A, Collins LM. 2015. PROC LCA & PROC LTA (Version 1.3.2) . [Software]. University Park, PA: Methodology Center, Pennsylvania State University. Available at https://www.latentclassanalysis.com/software/proc-lca-proc-lta/ .

Muthèn BO, Muthèn LK. 2021. Mplus (Version 8 .4) . [Software]. Los Angeles, CA: Muthèn & Muthèn.

Nasserinejad K, van Rosmalen J, de Kort W, Lesaffre E. 2017. Comparison of Criteria for Choosing the Number of Latent Classes in Bayesian Finite Mixture Models. PLoS ONE 12:1–23. Available at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168838 .

National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). 2021. Transparency in Statistical Information for the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics and All Federal Statistical Agencies . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/transparency-and-reproducibility-of-federal-statistics-for-the-national-center-for-science-and-engineering-statistics .

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). 2018. Survey of Doctorate Recipients , 2015 . Data Tables. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation. Available at https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/doctoratework/2015/ .

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). 2019. Survey of Doctorate Recipients , 2017 . Data Tables. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation. Available at https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/doctoratework/2017/ .

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). 2021. Survey of Doctorate Recipients, 201 9 . NSF 21-320. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation. Available at https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf21320/ .

Pashler H, Wagenmakers E-J. 2012. Editors’ Introduction to the Special Section on Replicability in Psychological Science: A Crisis of Confidence? Perspectives on Psychological Science 7(6):528–30. Available at https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612465253 .

SAS. 2021. SAS (Version 9.4) . Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Schmidt S. 2009. Shall We Really Do It Again? The Powerful Concept of Replication Is Neglected in the Social Sciences. Review of General Psychology 13(2):90–100. Available at https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015108 .

Suggested Citation

Fritz MS; National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). 2022. Replicating the Job Importance and Job Satisfaction Latent Class Analysis from the 2017 Survey of Doctorate Recipients with the 2015 and 2019 Cycles . Working Paper NCSES 22-208. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation. Available at https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/ncses22208 .

Matthew S. Fritz NCSES Research Ambassador/Fellow–Established Scientist, NCSES Associate Professor of Practice, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Nebraska–Lincoln E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected]

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences National Science Foundation 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W14200 Alexandria, VA 22314 Tel: (703) 292-8780 FIRS: (800) 877-8339 TDD: (800) 281-8749 E-mail: [email protected]

Read more about the source: Survey of Doctorate Recipients (SDR) .

Can't Find What You Are Looking For?

- Search NCSES to find data and reports.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 10 November 2021

Scientists count the career costs of COVID

- Chris Woolston 0

Chris Woolston is a freelance writer in Billings, Montana.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Martha Nelson was in her element in early 2020. As the world grappled with the outbreak of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, Nelson, who studied viruses with pandemic potential at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), felt her work was suddenly more urgent and relevant than ever. Friends and family assumed that she had ultimate job security. “People were telling me that I must be on top of the world because my work is so important,” she says.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 599 , 331-334 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-03040-1

Related Articles

Africa’s postdoc workforce is on the rise — but at what cost?

Career Feature 02 APR 24

Impact factors are outdated, but new research assessments still fail scientists

World View 02 APR 24

How scientists are making the most of Reddit

Career Feature 01 APR 24

Long COVID still has no cure — so these patients are turning to research

News Feature 02 APR 24

Google AI could soon use a person’s cough to diagnose disease

News 21 MAR 24

COVID’s toll on the brain: new clues emerge

News 20 MAR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

How two PhD students overcame the odds to snag tenure-track jobs

How can we make PhD training fit for the modern world? Broaden its philosophical foundations

Correspondence 02 APR 24

Postdoctoral Fellow (Aging, Metabolic stress, Lipid sensing, Brain Injury)

Seeking a Postdoctoral Fellow to apply advanced knowledge & skills to generate insights into aging, metabolic stress, lipid sensing, & brain Injury.

Dallas, Texas (US)

UT Southwestern Medical Center - Douglas Laboratory

High-Level Talents at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

For clinical medicine and basic medicine; basic research of emerging inter-disciplines and medical big data.

Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

POSTDOCTORAL Fellow -- DEPARTMENT OF Surgery – BIDMC, Harvard Medical School

The Division of Urologic Surgery in the Department of Surgery at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School invites applicatio...

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Director of Research

Applications are invited for the post of Director of Research at Cancer Institute (WIA), Chennai, India.

Chennai, Tamil Nadu (IN)

Cancer Institute (W.I.A)

Postdoctoral Fellow in Human Immunology (wet lab)

Join Atomic Lab in Boston as a postdoc in human immunology for universal flu vaccine project. Expertise in cytometry, cell sorting, scRNAseq.

Boston University Atomic Lab

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Scientists who work in industry are more satisfied and better paid than are colleagues in academia, according to the self-selected group of respondents, which comprised more than 3,200 working ...

The drop in job satisfaction despite the increase in salary satisfaction might seem contradictory, but Lizzie Knight, a researcher and professional careers counsellor at the University of Victoria ...

Scientists are about average in terms of happiness. At CareerExplorer, we conduct an ongoing survey with millions of people and ask them how satisfied they are with their careers. As it turns out, scientists rate their career happiness 3.3 out of 5 stars which puts them in the top 46% of careers. To put this into perspective, we compared how ...

By performing factor analysis and a clustering procedure on variables describing researchers' job. expectations we were able to categorize the respondents into three groups: 1) demanding, 2 ...

Academic life scientists above 65 reported mean salaries of $133,000, more than three times as large as those in the youngest (25 to 34) age group, who earn a mean of $41,000. For the general population, the ratio of peak earnings to early-career earnings is only 1.24, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Computer and information research scientists are about average in terms of happiness. At CareerExplorer, we conduct an ongoing survey with millions of people and ask them how satisfied they are with their careers. As it turns out, computer and information research scientists rate their career happiness 3.3 out of 5 stars which puts them in the top 42% of careers.

This study aims to explore professors' job satisfaction and the factors that influence their satisfaction. Professors whose main duties were instruction, research, service, and advising (i.e., four types of responsibilities) were invited to participate in the study; the participants of the study (n = 117) completed a questionnaire survey, and interviews (n = 50) were also conducted to ...

The aim of this study is to analyze simultaneously knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward job satisfaction in a general population in a large metropolitan area. The data acquired from 1043 questionnaires—administered to subjects with an average age of 35.24 years—revealed that only 30% is satisfied by his job.

A career in computer science can offer professionals a sense of job security with the expected outlook for computer and information research science occupations. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a faster than average employment growth for computer scientists at 22% from 2020 to 2030. This growth percentage also considers the ...

The research environment is classified into the organizational support, the leadership, the autonomy, and result-centered management. We analyzed the influence of research production on job satisfaction. Research production is classified into the research paper and the SCI (science citation index) paper.

A recent LinkedIn study says that Machine Learning Engineer, Data Scientist are top US emerging jobs and Glassdoor says that Data Scientist is the best job in America, 3 years in a row. However, a recent post Why so many data scientists are leaving their jobs by Jonny Brooks seems to have touched a nerve and brought a lot of dissatisfaction to ...

Fig 1: A conceptual model of Working Environment and Job Satisfaction This research study will test the relationship between working conditions and the job satisfaction. The hypothesis below is developed to analyze the relationship between the variables. ... International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(2), 206-213. Buglear, J. (2005 ...

The topic of job satisfaction research with co-citations analysis aims to . ... Articles in this study were provided by Science Direct and Emerald over a five-year . period from 2017 to 2022.

Google Scholar. Science Research Associates (1973) SRA Attitude Survey. Chicago. Google Scholar. Seashore, S.E. (1973) "Job satisfaction as an indicator of quality of employment." Prepared for the Symposium on Social Indicators of the Quality of Working Life, Canada Department of Labor. Google Scholar.

Having explored the factors influencing job satisfaction on the basis of the two-factor theory (Herzberg et al., 1959), previous studies have mainly used survey analyses through interviews or questionnaires (Alrawahi et al., 2020; Lo et al., 2016; Matei & Abrudan, 2016; Sanjeev & Surya, 2016).However, these types of methodologies using survey data pose the risk of incorporating the researcher ...