Search the Site

Popular pages.

- Historic Places of Los Angeles

- Important Issues

- Events Calendar

Stahl House (Case Study House #22)

Immortalized by photographer Julius Shulman, the Stahl House epitomized the ideal of modern living in postwar Los Angeles.

Place Details

- Pierre Koenig

Designation

- Locally Designated

Property Type

- Single-Family Residential

- Los Angeles

Based on a recent approval by the City of Los Angeles for a new residence at the base of the hillside and below the historic Stahl House, this action now places this Modernist icon at risk. The hillside is especially fragile as it is prone to slides and susceptible to destabilization. This condition will be exacerbated as this proposed new residence is planned to cut into the hillside and erect large retaining walls.

The proposed project received approval despite opposition and documentation submitted that substantiates the problem and potential harm to the Stahl House. An appeal has been filed and the City is reviewing this now. No date has been set yet for when this might come back to the City Planning Commission.

To demonstrate your support for the Stahl House and to ensure the appeal is granted (sending the proposed project back for review), please sign on to the Save the Stahl House campaign .

Who hasn’t seen the iconic image of architect Pierre Koenig’s Stahl House (Case Study House #22), dramatically soaring over the Los Angeles basin? Built in 1960 as part of the Case Study House program, it is one of the best-known houses of mid-century Los Angeles.

The program was created in 1945 by John Entenza, editor of the groundbreaking magazine Arts & Architecture . Its mission was to shape and form postwar living through replicable building techniques that used modern industrial materials. With its glass-and-steel construction, the Stahl House remains one of the most famous examples of the program’s principles and aesthetics.

Original owners Buck and Carlotta Stahl found a perfect partner in Koenig, who was the only architect to see the precarious site as an advantage rather than an impediment. The soaring effect was achieved using dramatic roof overhangs and the largest pieces of commercially available glass at the time.

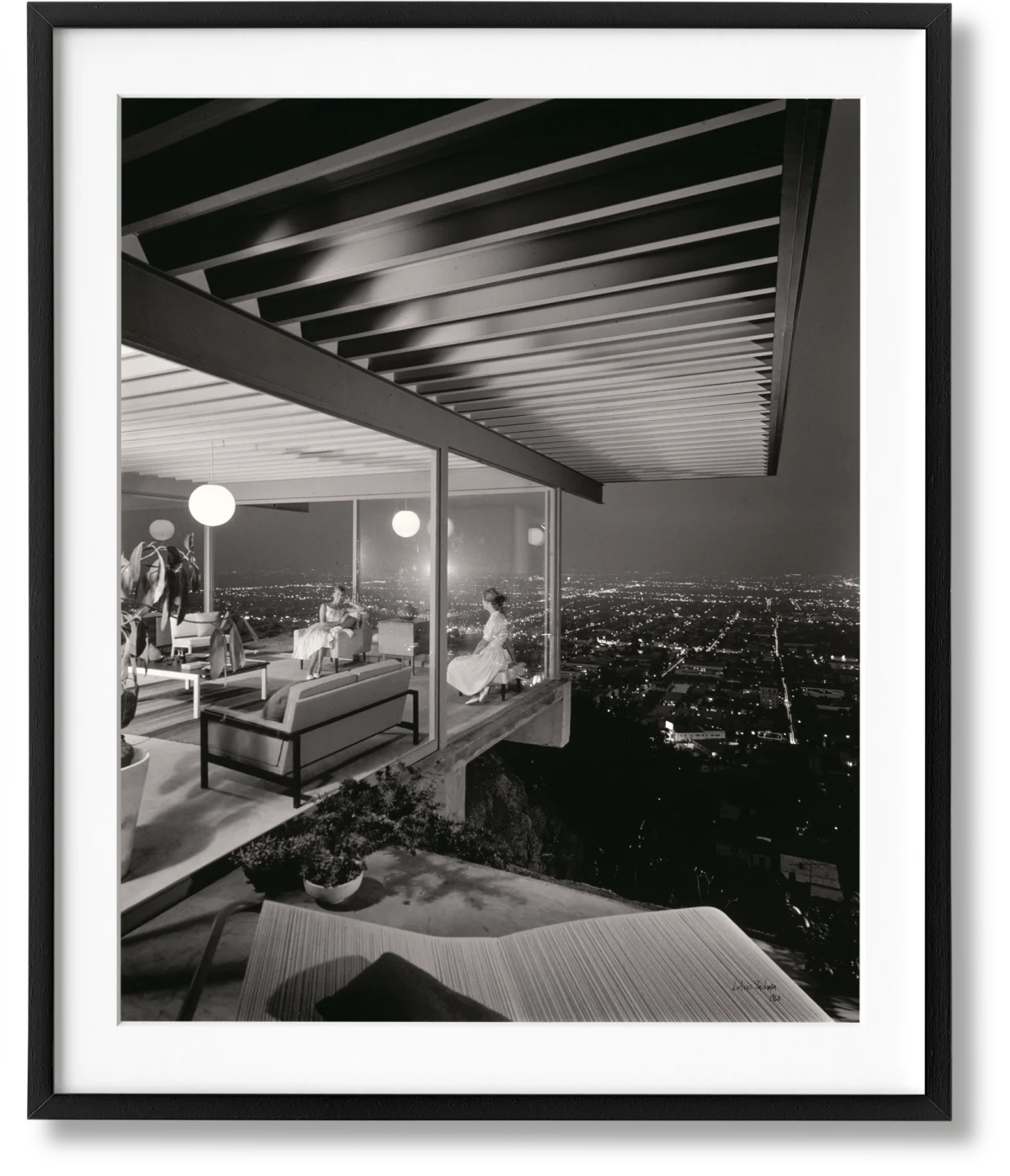

The enduring fame of the Stahl House can be partly attributed to renowned architectural photographer Julius Shulman, who captured nearly a century of growth and development in Southern California but was best-known for conveying the Modern architecture and optimistic lifestyle of postwar Los Angeles. Shulman’s most iconic photo perfectly conveys the drama of the Stahl House at twilight: two women casually recline in the glowing living room as it hovers over the sparkling metropolis below.

View the National Register of Historic Places Nomination

The Conservancy does not own or operate the Stahl House. For any requests, please contact the Stahl House directly at (208) 429-1058.

Issues including Stahl House (Case Study House #22)

Case Study Houses

Related content.

Casa de Cadillac

Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility Campus/Historic District

Fifth Church of Christ, Scientist

- Current Exhibitions

- Past Exhibitions

- Upcoming Exhibitions

- Gallery Map

- Research Appointments

- Volunteering

- Support Affiliate

- Hours & Directions

- Public Art Collection

- Public Art Map

- Photography

- Student Art

- Education Program

- Kids' Spot

- Press Releases

- Visitor Survey

- Image Permissions

Julius Shulman: Case Study

The Case Study House program was established by Arts & Architecture magazine in 1945 in an effort to produce model homes for efficient and affordable living during the housing boom generated after the end of World War II. Using Southern California as a location for the prototypes and commissioning top architects of the day, the program made important contributions to mid-twentieth-century American architecture. The majority of the program’s thirty-six commissioned designs were constructed, and featured the work of notable architects such as Charles and Ray Eames, Richard Neutra, Pierre Koenig, and Raphael Soriano.

The artist responsible for documenting these homes was Julius Shulman (1910–2009). A longtime resident of Southern California, Shulman began a career in architectural photography in 1936 when asked by an acquaintance working for Richard Neutra to photograph the architect’s recently completed Kun Residence. His visual interpretation of space struck a chord with Neutra, who hired him to document each of his projects. Shulman’s career quickly escalated, and by the mid-1950s he had become widely recognized as one of the nation’s foremost photographers of architecture. Much of his early success can be attributed to his dynamic images of the Case Study Houses. During the program’s active years, Shulman worked on assignment for the magazine and in collaboration with contributing architects to photograph the majority of the prototype homes. Vivid and persuasive, his photographs capture the essence of each home, rendering the steel and glass structures as inviting and attractive places for modern living.

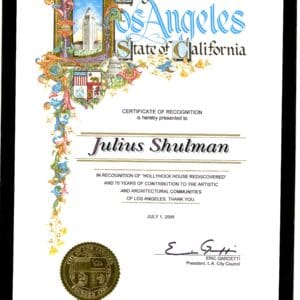

Born in Connecticut, Shulman moved to California in the 1920s, later studying at University of California, Los Angeles, and University of California, Berkeley. Shulman worked full-time as a commercial architectural photographer from 1936 until the late 1980s, then intermittently until the early 2000s. His work has appeared in countless publications and exhibitions, and has come to be valued both as an archive of historical importance, and for its place in the art world. Shulman held three honorary doctorates from various United States universities, and in 1998, he received a lifetime achievement award from the International Center for Photography in New York. In 2005, Shulman’s work was featured at the Getty Research Institute in a retrospective exhibition corresponding with the institute’s acquisition of his archive, which contains over 260,000 negatives, transparencies, and prints.

©2017 by San Francisco Airport Commission. All rights reserved.

Cookie banner

We use cookies and other tracking technologies to improve your browsing experience on our site, show personalized content and targeted ads, analyze site traffic, and understand where our audiences come from. To learn more or opt-out, read our Cookie Policy . Please also read our Privacy Notice and Terms of Use , which became effective December 20, 2019.

By choosing I Accept , you consent to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies.

Filed under:

Creating the iconic Stahl House

Two dreamers, an architect, a photographer, and the making of America’s most famous house

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/56342955/gri_2004_r_10_b190_f007_2980_17.0.jpg)

In 1953 a mutual friend introduced Clarence Stahl, better known as Buck, to Carlotta Gates. They met at the popular Mike Lyman’s Flight Deck restaurant, off Century Boulevard, which overlooked the runways at Los Angeles International Airport. Buck was 41 and Carlotta 24. The couple married a year later and remained together for more than 50 years, until Buck’s death in 2005.

Working with Pierre Koenig, an independent young architect whose primary materials were glass, steel, and concrete, the couple created perhaps the most widely recognized house in Los Angeles, and one of the most iconic homes ever built. No one famous ever lived in it, nor was it the site of a Hollywood scandal or constructed for a wealthy owner. It was just the Stahls’ dream home. And it almost did not come true.

As a newlywed, Carlotta moved into the house Buck was renting—the lower half of a two-story wood-frame house on Hillside Avenue in the Hollywood Hills, just west of Crescent Heights Boulevard and north of Sunset Boulevard. From the house, Buck and Carlotta looked across a ridge toward a promontory that drew their attention every morning and evening. As Carlotta explained during an interview with USC history professor Philip Ethington, this is how the dream of building their own home started: simply and incidentally. Although they felt emotionally and psychically drawn to the promontory, they did not have the financial means to buy the lot, even if it were available.

For months they looked intently across the ridge. Then, in May 1954, the couple decided “Let’s go over and see our lot. We’d already claimed it even though we’d never been here,” Carlotta told Ethington, adding, “And when we came up that day George Beha [the owner of the lot] was in from La Jolla. He and Buck talked, then, I would say an hour, hour and [a] half later, they shook hands. We bought the lot and he agreed to carry the mortgage.” They settled on a price of $13,500. At the end of their meeting, Buck gave Beha $100 as payment to make the agreement binding.

There were no houses along the hillside near the site that would become the Stahl House on Woods Drive, although the land was getting graded in anticipation of development. Richard D. Larkin, a real estate developer, acquired the lots on the ridge in a tax sale from the city of Los Angeles around 1958 and arranged to subdivide and grade them. The city hauled away the dirt without charge to use the decomposed granite for runway construction at LAX. In the process, the city made the road for Woods Drive.

The Stahls’ chance meeting with Beha abruptly made their vision more of a reality, but building was still a long way away. After nearly four years of mortgage payments to Beha, Buck prepared the lot for construction. He did this without having building specs, but knowing it would be necessary to shape the difficult hillside lot. In the first of many do-it-yourself accomplishments, he built up the edges to make the lot flat and level. To create a larger buildable area he laid the edge of the foundation with broken concrete, which was readily available at no cost from construction sites and provided Buck with flexibility for his layout. He could also lift and move the pieces without heavy equipment. He constructed a concrete wall and terracing with broken pieces of concrete. But he was told by architects and others that his effort would not improve the buildability of the property.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102365/gri_2004_r_10_b190_f006_2980_05.jpg)

The developer, Larkin, showed Buck how to lay out and stack the concrete, Buck recalled to Ethington. It was not a completely new concept, as photographer Julius Shulman, whose photograph of the Stahl House would later become internationally recognized, used broken concrete in the landscaping on his property. But Buck’s use was far more labor-intensive and consuming. On evenings and weekends he managed to pick up discarded concrete from construction sites around Los Angeles, asking the foremen if he could haul the debris away. He did this dozens of times before collecting enough for the concrete wall.

Buck used decomposed granite from the lot and surrounding area, instead of fresh cement, to fill in the gaps between the concrete pieces. The result was a solid form that remains intact and stable today, almost 60 years later. What had been the underlying layer for a man-made structure became the underlying layer for a new man-made structure—Buck’s layers of broken concrete added another facet to the topography of the house and the city, and this hands-on development of the lot connected the Stahls to the land and house.

As they completed their final monthly payments, Buck finished a scale model of their dream home, and the couple began to look for an architect. The central architectural feature of the model was a butterfly roof combined with flat-roofed areas. From the beginning, Buck and Carlotta envisioned a glass house without walls blocking the panoramic view.

Their frequent visits to the lot intensified their desire to build a home of their own design. Like an architect, Buck studied the composition of the land, the shape of the lot, the direction of light, and the best way to ensure the views. Perhaps most importantly, he considered the architectural style that would ideally highlight these qualities.

Carlotta told Ethington they decided to meet with three architects whose work they had seen in different publications: Craig Ellwood, Pierre Koenig, and one more whom she did not remember. She said Ellwood and the unidentified architect “came to the lot [and] said we were crazy. ‘You’ll never be able to build up here.’”

When Koenig visited the site with the Stahls, he and Buck “just clicked right away,” according to Carlotta. In the 1989 documentary The Case Study House Program, 1945-1966: An Anecdotal History & Commentary , Koenig recalled how Buck “wanted a 270-degree panorama view unobstructed by any exterior wall or sheer wall or anything at all, and I could do it.” The Stahls appreciated Koenig’s enthusiasm and willingness to work with them. They had a written agreement in November of 1957.

The massive spans of glass and the cantilevering of the structure, essential aspects of the design to Koenig, precluded traditional wood-frame house construction. To ensure the open floorplan, uninterrupted views, and the structure required to create those features, steel became inevitable. Steel would also offer greater stability than wood during an earthquake. The use of exposed glass, steel, and concrete was a functional and economic decision that defined the aesthetics of the house. In combination, these industrial materials were not then common choices in home construction, though they were materials Koenig used frequently. Exposing the material structure of the house illuminated its transparency as an indoor-outdoor living space.

Koenig kept the spirit of Buck’s model, but removed a key aspect: the butterfly roof. Koenig flattened the roof and removed the curves from Buck’s design, so the house consisted of two rectangular boxes that formed an L.

When he sited the house and drew his preliminary plans, Koenig aligned the house so that the roof and structural cantilever mirrored the grid-like arrangement of the streets below the lot. Once completed, the house visually extended into the Los Angeles cityscape. The symmetry enhanced the connection between the house and the land. In The Case Study House Program 1945-1966 documentary, Koenig says, “When you look out along the beams it carries your eye out right along the city streets, and the [horizontal] decking disappears into the vanishing point and takes your eye out and the house becomes one with the city below.”

With the design completed, the Stahls’ dream was closer to coming to life, but there were further obstacles. The unconventional design of the house and its hillside construction made it difficult to secure a traditional home loan; banks repeatedly turned down Buck because it was considered too risky. As Buck explained to Ethington, “Pierre [kept] looking [for financing] and he had his rounds of contacts.” Koenig was finally able to arrange financing for the Stahls through Broadway Federal Savings and Loan Association, an African-American-owned bank in Los Angeles.

Broadway Federal had one unusual condition for the construction loan: The Stahls were required to secure a second loan for the construction of a pool and would need another bank to finance it. They had had a yard in mind, but a pool would increase the overall cost of the home—for the bank, it added value to the property and made the loan less risky.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102373/gri_2004_r_10_b199_2980_02k.jpg)

After more searching, Buck found a lender for the pool construction so both projects could proceed. Broadway Federal loaned the Stahls $34,000. The second lender financed the pool at a cost of approximately $3,800.

Broadway Federal’s loan is ironic and extraordinary. Although it was not a reflection of the Stahls’ own values, the area that included their lot had legally filed Covenants, Conditions, and Restrictions from 1948 that indicated “the property shall not, nor shall any part thereof be occupied at any time by any person not of the Caucasian race, except that servants of other than the Caucasian race may be employed and kept thereon.” It was a discriminatory restriction against African Americans, and yet an African-American-owned bank made it possible for a Caucasian couple to build their home there.

When Pierre Koenig began work on the Stahl House, he was 32 years old and had built seven of the more than 40 projects he would design in his career. The Stahl House is the best known and is considered his masterwork, although Koenig considered the Gantert House (1981) in the Hollywood Hills the most challenging house he built. The long-term influence of the Stahl House is apparent in Gantert House and many of Koenig’s other projects.

Koenig built his first house in 1950—for himself—during his third year of architecture school at USC. It was a steel, glass, and cement structure. Although the architecture program had dropped its focus on Beaux Arts studies and modernism was coming to the fore, residential use of steel was not part of Koenig’s curriculum. But when he looked at the post-and-beam architecture then considered the standard of modern architecture, he felt the wood structures looked thin and fragile, and should be made of steel instead.

Koenig later told interviewer Michael LaFetra about a conversation with his instructor: “He said ‘No, you cannot use steel as an industrial material for domestic architecture. You cannot mix them up. The housewife won’t like [steel houses].’ The more he said I couldn’t do it, the more I wanted to do it. That’s my nature. He failed me. I got absolutely no help from him.”

But wartime production methods, particularly arc welding, were a source of inspiration for Koenig’s use of steel. Electric arc welding did not require bolts or rivets and instead created a rigid connection between beams and columns. Cross-bracing was not required, which opened greater possibilities: Aesthetically, it offered a streamlined look and allowed him to design a large open framework for unobstructed glass walls. The thin lines of the steel looked incidental compared to their strength.

His first house was originally designed as a wood building, but redesigned for steel construction. He commented years later that that was not the way to do it—he learned how to design for steel by taking an entirely new approach. There was little precedent to support his efforts: Such discoveries were an education for him, and he worked to resolve issues on his own. In Esther McCoy’s book Modern California Houses: Case Study Houses, 1945-1962 , Koenig declares, “Steel is not something you can put up and take down. It is a way of life.”

From then on, Koenig continued to develop his architectural vision—both pragmatic and philosophical. Prefabricated housing was a promising development following the war, but consumers found the homes’ cookie-cutter, invariable design unappealing. Koenig’s goal was to use industrialized components in different ways to create unique, innovative buildings using the same standard parts: endless variations with the core materials of glass, steel, and cement. Koenig’s intention, as captured in James Steel’s biography Pierre Koenig , “was to be part of a mechanism that could produce billions of homes, like sausages or cars in a factory.”

“The basic problem is whether the product is well designed in the first place,” Koenig further explained in a 1957 Los Angeles Times article by architectural historian Esther McCoy. “There are too many advantages to mass production to ignore it. We must accept mass production but we must insist on well-designed products.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102379/gri_2004_r_10_b190_f008_2980_24.jpg)

Reducing the number of parts and avoiding small parts were ways to reduce costs and streamline construction. In the case of the Stahl House, the efficiencies generated by the minimal-parts approach led to an inventory of fewer than 60 building components. In 1960, in an interview for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner , Koenig said:

“All I have done is to take what we know about industrial methods and bring it to people who would accept it. You can make anything beautiful given an unlimited amount of money. But to do it within the limits of economy is different. That’s why I never have steel fabricated especially to my design. I use only stock parts. That is the challenge—to take these common everyday parts and work them into an aesthetically pleasing concept.”

Although Koenig completed a plot plan for the Stahl House in January 1958, he did not submit blueprints to the city of Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety until that July. Due to the extensive use of steel and glass in a residential plan, combined with the hillside lot and dimensions and form that the department found irregular, the city did not consider the house up to code and would not approve construction. Instead they noted, “Board Action required to build on this site because of the extremely high steep slopes on the east and south sides.”

In a move typical of Koenig’s intellect and his ability to understand all details of construction, he prepared the technical drawings so he was able to discuss details with the planners. He spent several months explaining his design and material specifications to the city. Since they had not seen many plans for the extensive use of steel in home construction, the building officials asked him, “Why steel?”

In his interview with LaFetra, Koenig explained that he thought steel would last longer than wood and knew “building departments were not used to the ideas of modern architecture.” They would frown on “doing away with hip roof, shingles, you had to have a picket fence, window shutters.”

“The Building Department thought I was crazy,” Koenig said. “I can remember one of the engineers saying, ‘Why are you going to all this trouble? All you have to do is open up the code book and put down what’s in the code book. You could have a permit tomorrow.’ I asked myself, Why am I doing this?! I was motivated by some subconscious thing.” Koenig reduced the living room cantilever by 10 feet and removed the walkway around the house in order to move the plans forward.

He finally received approval in January 1959. Carlotta remembers, “One of the officials … said [there’ll] never be another house built like this ’cause they didn’t like the big windows. That was one of the things that bothered them more than anything, and the fact that we’re cantilevered.”

The city’s lengthy approval process contrasted with Koenig’s quick construction of the house. Due to its minimalist structural design and reduced number of building components compared to traditional wood construction, framing of the house was simplified. A crew of five men completed the job in one day.

The challenges of building were known, and they primarily related to the lot. “There’s very little land situated on this eagle nest high above Sunset Boulevard,” Koenig explained in the documentary film about the Case Study House Program. “So the swimming pool and the garage went on the best part, mainly because who wants to spend a lot of money supporting swimming pools and garages? And it’s very hard to support a pool on the edge of a cliff. The house it could handle. So the house is on the precarious edge.”

With the exception of the steel-frame fireplace (chimney and flue were prefabricated and brought to the site), Koenig used only two types of standard structural steel components: 12-inch beams and 4-inch H columns. The result is a profound demonstration of Koenig’s technical and aesthetic expertise with rigid-frame construction. The elimination of load-bearing walls on this scale represented the most advanced use of technology and materials for residential architecture ever.

Koenig’s success with steel-frame construction is partially due to William Porush, the structural engineer for the Stahl House. Porush engineered more than half of Koenig’s projects, beginning with Koenig’s first house in 1950.

A native of Russia, Porush emigrated to the U.S. in 1922 and graduated with a degree in civil engineering from the California Institute of Technology in 1926. After working for a number of firms in Los Angeles and later with the LA Department of Building and Safety during World War II, Porush opened his own office in 1946 and eventually designed his own post-and-beam house in Pasadena in 1956.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102383/gri_2004_r_10_b199_2980_09k.jpg)

The scale of his projects ranged from commercial buildings using concrete tilt-up construction in downtown Los Angeles to professional offices in Glendale, light industrial engineering, and a number of schools in Southern California—including traditional wood and brick, glass, and steel schools in Riverside.

Love midcentury homes?

Compare notes with other obsessives in our private Facebook group.

When Porush retired at 89 years old, his son Ted ran the practice for several years before retiring himself. Speaking of both his and his father’s experience working with Koenig in 2012, Ted said, “Koenig was quite devoted and always had something in mind all the time without being unreasonable or obstinate, really an artist perhaps,” and added that he and his father “welcomed Koenig’s engineering challenges—whether related to innovations, materials, or budget constraints.”

General contractor Robert J. Brady was the other key member of Koenig’s Stahl House crew. Brady gained industry experience running a construction business in Ojai, California, where he was a school teacher. This was the only time Brady and Koenig worked together, as Koenig was dissatisfied, he later wrote, with Brady’s management of the Stahl House, as indicated in a letter to Brady himself in the Pierre Koenig papers at the Getty Research Institute.

In 1957, Koenig approached Bethlehem Steel about the development of a program for architects using light-steel framing in home construction. At the time, Bethlehem Steel did not see a market or need to formalize a program. Residential use of steel, while known, was still very uncommon.

“The steel house is out of the pioneering stage, but radically new technologies are long past due,” Koenig explained in an interview with Esther McCoy. “Any large-scale experiment of this nature must be conducted by industry, for the architect cannot afford it. Once it is undertaken, the steel house will cost less than the wood house.”

By 1959, Bethlehem Steel saw how quickly the market was changing and started a Pacific Coast Steel Division in Los Angeles to work specifically with architects. The division then shared their preliminary specifications with Koenig for architecturally exposed steel and solicited his comments and opinions.

To introduce Bethlehem’s new marketing effort, they published a booklet in 1960, “The Steel-Framed House: A Bethlehem Steel Report Showing How Architects and Designers Are Making Imaginative Use of Light-Steel Framing In Houses.” Koenig’s Bailey House (CSH No. 21) and the Stahl House both appeared in the booklet. Bethlehem promoted Koenig’s architecture with Shulman photographs and accompanying text: “What could be more sensible than to make this magnificent view of Los Angeles a part of the house—to ‘paper the walls’ with it?” and “Problem Sites? Not with steel framing!” The brochure showed multiple views of the Stahl House.

For architects, having work published during this time led to recognition and often translated to future projects. Arts & Architecture magazine and its publisher John Entenza played an essential role in promoting Koenig’s architecture. Entenza conceived of the Case Study House Program in the months prior to the end of World War II, in anticipation of the demand for affordable, thoughtfully designed middle-class housing, and introduced it in the magazine’s January 1945 issue. The purpose of the program was to promote new ways of living based on advances in design, construction, building methods, and materials.

After the war, an impetus to produce new forms emerged. In architecture, that meant a move away from traditionally built homes and toward modern design. The postwar availability of industrial and previously restricted materials, especially glass, steel, and cement, offered architects freedom to pursue new ideas. In addition to materials, the modern approach in home design resulted in less formal floor plans that could offer continuity, ease of flow, multipurpose spaces, fewer interior walls, sliding glass walls and doors, entryways, and carports. Homes were generally built with a flat roof, which helped define a horizontal feel. Interior finishes were simple and unadorned, and there was no disguising of materials.

The absence of traditional details became part of the new aesthetic. Both exterior and interior structures were simplified. This all contributed to perhaps the most significant appeal of postwar architecture in Southern California: indoor-outdoor living. By physically, visually, and psychologically integrating the indoors and outdoors, it offered a new, casual way of life that more actively connected people to their environment. Combined with year-round mild weather, these new houses afforded a growing sense of independence and freedom of expression.

Arts & Architecture presented works-in-progress and completed homes throughout its pages, devoting more space in the magazine to the modern movement than other publications. Trends with finishes, built-ins, and low-cost materials spread across homes in Southern California after publication in Arts & Architecture . The magazine’s modern aesthetic extended across the country, where architects developed new solutions based on what they had seen in its pages. And since it reached dozens of countries, the international influence of California modernism through Entenza’s editorial eye was profound.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102411/gri_2004_r_10_b190_f006_2980_08.jpg)

The Case Study House Program provided a point of focus. As noted by Elizabeth Smith, art historian and museum curator, all 36 of the Case Study houses were featured in the magazine, although only 24 were built. With the exception of one apartment building, they were all single-family residences completed between 1945 and 1966.

“John Entenza’s idea was that people would not really understand modern architecture unless they saw it, and they weren’t going to see it unless it was built,” Koenig said in James Steel’s monograph. “[Entenza’s] talent was to promulgate ideas that many architects had at that time.”

In conjunction with the magazine, Entenza sponsored open houses at recently completed Case Study houses, giving visitors the opportunity to experience the modern aesthetic. Contemporary design pieces such as furniture, lamps, floor coverings, and decorative objects created a context for everyday living. The open houses took on a realistic dimension that generated a range of responses: “Oh, steel, glass and cement are cold.” “This is not homey.” “Could I live here?” “How would I live here?”

The program gave architects exposure and in many cases brought them credibility and a new clientele—although it was not a wealth-generating endeavor for the architects. For manufacturers and suppliers, it was a convenient way to receive publicity since people could see their products or services in use.

The Case Study House Program did not achieve Entenza’s goal: the development of affordable housing based on the design of houses in the program. None of the houses spurred duplicates or widespread construction of like-designed homes. The motivation from the building industry to apply the program’s new approaches was short-lived and not widely adopted.

Speaking many years later, Koenig stated in Steel’s monograph that “in the end the program failed because it addressed clients and architects, rather than contractors, who do 95 percent of all housing.” Instead, the known, accepted, and traditional design, methods of construction, and materials continued to prevail. Buyers still largely preferred conventional homes—a fact reinforced by the standard type of construction taught in many architecture schools during the postwar years.

However, today the program must be considered highly successful for its impact on residential architecture, and for initiating the California Modern Movement. The program influenced architects, designers, manufacturers, homeowners, and future home buyers. As McCoy reported, “The popularity of the Case Studies exceeded all expectations. The first six houses to be opened [built between 1946 and 1949] received 368,554 visitors.” The houses in the program, and their respective architects, now characterize their architectural era, representing the height of midcentury modern residential design.

The Stahl House became Case Study House No. 22 in the most informal way. With the success of Koenig’s Bailey House (CSH No. 21), Entenza told Koenig if he had another house for the program, to let him know. Koenig told him about his next project, the Stahl House.

In April 1959, months before construction started, Entenza and the Stahls signed an exclusive agreement indicating the house would become known as Case Study House No. 22 and appear in Arts & Architecture magazine. This also meant the house would be made available for public viewings over eight consecutive weekends and Entenza had the rights to publish photographs and materials in connection with the house. Additionally, he had approval of the furnishings. (He included an option for the Stahls to buy any or all of the furnishings at a discount.)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102405/gri_2004_r_10_b199_2980_13k.jpg)

By agreeing to make their house CSH No. 22, the Stahls were making their dream home more affordable. Equipment and material suppliers sold at cost in exchange for advertising space in the magazine. The arrangement gave Koenig the opportunity to negotiate further with vendors, since he was likely to use them in the future. Buck estimated in his interview with Ethington that it “ended up saving us conservatively $10,000 or $15,000” on the construction.

The house was featured in Arts & Architecture four times between May 1959 and May 1960, in articles documenting its progress and completion.

Arts & Architecture only ended up opening the house for public viewings on four weekends, from May 7 to May 29, 1960. The showings were well attended, and the shorter schedule meant the Stahls could move into the house sooner.

The Stahl House is a 2,200-square-foot home with two bedrooms and two bathrooms, built on an approximately 12,000-square-foot lot.

Construction began in May 1959 and was completed a year later, in May 1960. The pre-construction built estimate was $25,000, with Koenig to receive his usual 10 percent architect’s fee. His agreement with the Stahls additionally provided him 10 percent of any savings he secured on construction materials. The budget for the house was revised to $34,000, but Koenig’s fee of $2,500 did not change.

The final cost was over $15 per square foot—notably more than the average cost per square foot of $10 to $12 in Southern California at the time.

During its lifetime, the Stahl House has had very few modifications. For a short time, AstroTurf surrounded the pool area to serve as a lawn and make the area less slippery for the Stahls’ three children. There have been minor kitchen remodels with necessary updates to appliances. The kitchen cabinets, which were originally dark mahogany, were replaced with matched-grain white-oak cabinets due to fading caused by heavy exposure to sunlight. A catwalk along the outside of the living room, on the west side, was added to make it easier to wash the windows. Stones were applied to the fireplace, which was originally white-painted gypsum board with a stone base. A stone planter was also added to match the base. The pool was converted to solar heat.

These changes maintain the spirit of the house. Perhaps without effort, Koenig activated what architect William Krisel termed “defensive architecture”: building to preempt alterations and keep a structure as originally designed. Koenig's original steel design, comprehending potential earthquake risk, remains superior to traditional building materials.

The Stahl House has served as the setting for dozens of films, television shows, music videos, and commercials. Its appearances in print advertisements number in the hundreds. By Koenig’s count, the house can be seen in more than 1,200 books.

At times, the house has played a leading role. Its first commercial use was in 1962, when the Stahls made the house available for the Italian film Smog not long after they moved in.

Movies featuring the Stahl House

The First Power (1990)

The Marrying Man (1991)

Corina Corina (1994)

Playing By Heart (1998)

Why Do Fools Fall In Love (1998)

Galaxy Quest (1999)

The Thirteenth Floor (1999)

Nurse Betty (2000)

Where the Truth Lies (2005)

In Los Angeles magazine, years later, Carlotta recalled the production: “One of the days they were shooting, the view was too clear, so they got spray and smogged the windows.” The Stahls grew to accept such requests, and the result has been decades of commercial use.

Koenig explained its attraction in the New York Times : “The relationship of the house to the city below is very photogenic … the house is open and has simple lines, so it foregrounds the action. And it’s malleable. With a little color change or different furniture, you can modify its emotional content, which you can’t do in houses with a fixed mood and image.”

This versatility offers a wide range of settings, from kitsch to urbane, comedy to drama. The house has also been rendered in 3D software for various architectural studies and appears in the game The Sims 3 , perhaps the most revealing proof of its demographic reach.

In nearly all appearances, the Stahl House conveys a sense of livability that is aspirational while remaining accessible. It reflects Koenig’s skillful architectural purpose. The architect is invisible by design. Understandably, Koenig was very pleased to see the frequent and varied use of the Stahl House. However, as he said in the New York Times , “My gripe is the movies use [houses] as props but never list the architect in the credits.” He added, “Architects, of course, get no residuals from it. The Stahls paid off the original $35,000 mortgage for the house and pool in a couple of years through location rentals, and now the house is their entire income.”

Once Buck retired in 1978, renting the house for commercial use became an especially helpful way to supplement their income. Today the family offers tours and rents the house for events and media activities. They also honor Carlotta’s restriction, noted in a 2001 interview with Los Angeles magazine: “I will not allow nudity. My Case Study House is not going to be associated with that.”

“Julius Shulman called. ... He’ll be there tonight. Call him at 6 p.m. and make arrangements for tonite. By then he’d appreciate it if you would know if Stahl could put off moving in until pictures are shot.”

This ordinary call logged in Koenig’s office journal eventually led to the creation of one of the most iconic photographs of the postwar modern era.

However, delays with completing interior details almost prevented Shulman from photographing the house and meeting his publication deadline, even after he negotiated with his editor to change it several times. The potential of missing an opportunity to promote the house frustrated Koenig. “As you know we were supposed to shoot Monday [April 18, 1960],” he wrote to his general contractor, Robert Brady:

“The deadline has been changed once but it is impossible to change it again. The die is set. Mr. Van Keppel is waiting to move furniture in. Shulman comes by the job every day to see when he can shoot. Mr. Entenza is shouting for photos so he can print the next issue. The president of Bethlehem is supposed to visit the finished house this Friday [April 22]. There is to be a press conference this week-end. Not to mention Mr. Stahl. This will give you some idea of the pressure being put on.”

After Brady completed the finishing work, and months after it was originally scheduled, Shulman photographed the house over the course of a week. There was still construction material in the carport, and the master bathroom was not complete.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102435/gri_2004_r_10_b199_2980_20k.jpg)

The color image of the two women sitting in the house with the city lights at night first appeared on the cover of the July 17, 1960, Los Angeles Examiner Pictorial Living section, a pull-out section in the Sunday edition of the newspaper. The article about the house, “Milestone on a Hilltop,” also included additional Shulman photographs.

By the time Shulman photographed the Stahl House he was an internationally recognized photographer. He was indirectly becoming a documentarian, historian, participant, witness, and promulgator of modern architecture and design in Los Angeles.

The Stahl House photograph, taken Monday, May 9, 1960, has the feel of a Saturday night, projecting enjoyment and life in a modern home. Shulman reinforces the open but private space by minimizing the separation of indoor and outdoor. The photograph achieves a visual balance through lighting that is both conventional and dramatic. As with much of Shulman’s signature work, horizontal and vertical lines and corners appear in the frame to create depth and direct the viewer’s eye, creating a dimensional perspective instead of a flat, straightforward position. The effect is a narrative that emphasizes Koenig’s architecture.

“What’s so amazing is that the house is completely ethereal,” architect Leo Marmol said in an interview with LaFetra in 2007. “It’s almost as though it’s not there. We talk about it as though it’s a photograph of an architectural expression but really, there’s very little architecture and space. It’s a view. It’s two people. It’s a relationship.”

Shulman recalled how the image came about in an interview with Taina Rikala De Noriega for the Archives of American Art:

So we worked, and it got dark and the lights came on and I think somebody had brought sandwiches. We ate in the kitchen, coffee, and we had a nice pleasant time. My assistant and I were setting up lights and taking pictures all along. I was outside looking at the view. And suddenly I perceived a composition. Here are the elements. I set up the furniture and I called the girls. I said, “Girls. Come over sit down on those chairs, the sofa in the background there.” And I planted them there, and I said, “You sit down and talk. I'm going outside and look at the view.” And I called my assistant and I said, “Hey, let's set some lights.” Because we used flash in those days. We didn't use floodlights. We set up lights, and I set up my camera and created this composition in which I assembled a statement. It was not an architectural quote-unquote “photograph.” It was a picture of a mood.

The two girls in the photograph were Ann Lightbody, a 21-year-old UCLA student, and her friend, Cynthia Murfee (now Tindle), a senior at Pasadena High School. At Shulman’s suggestion, Koenig told his assistant Jim Jennings, a USC architecture student, and his friend, fellow architecture student Don Murphy, to bring their girlfriends to the house. Shulman liked to include people in his photographs and intuitively felt the girls’ presence would offer more options. As for their white dresses, Tindle explains, “… in 1960, you didn't go out without wearing a dress. You would never have gone out wearing jeans or pants.”

In a rare explanation of the mechanics of his photography published in Los Angeles Magazine , Shulman described how he created the photograph: a double-exposure with two images captured on one negative with his Sinar 4x5 camera. He took the first image, a 7.5-minute exposure of the cityscape, while the girls sat still inside the house with the lights off. To ensure deep focus, he used a smaller lens opening (F/32) for the long exposure. After the exposure, Leland Lee, Shulman’s assistant, replaced the light bulbs in the globe-shaped ceiling lights with flash bulbs. Shulman then captured the second exposure, triggering the flash bulbs as the girls posed. The composite image belies Shulman’s technical and aesthetic achievement.

The same technique was applied when he photographed the man wearing the light-blue sport coat looking out over the city with his back to the camera. This photograph creates its own mystique around the man’s identity: perhaps a bachelor in repose, or homeowner Buck Stahl. But in fact, he was neither. The photograph was a pragmatic solution.

“We had been working all day photographing the house,” Shulman explained. “The representative from Bethlehem Steel was at the house. Bethlehem Steel provided the steel, and he was there to select certain areas they wanted to show for advertising. Pierre [Koenig] suggested we photograph the representative in the house, but the man from Bethlehem Steel could not be photographed as an employee of the company, so he stood in the doorway with his back to the camera.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102449/gri_2004_r_10_b199_2980_19k.jpg)

Shulman routinely staged interiors using furniture from his own home, particularly when a house was just completed or vacant. He believed realistic settings created warmth and helped viewers imagine scale. Placement of furniture could convey a clearer sense of life in a particular house and highlight the architecture. Although the Stahl House was vacant, Shulman did not bring in his own furniture. Instead, designer Hendrik Van Keppel of the firm Van Keppel-Green furnished the interiors in keeping with Koenig’s feeling that “everything in the house should be designed consistently with the same design throughout.”

Keppel-Green’s popular outdoor furniture, made with anodized metal frames and wrapped with nylon marine cord, are seen around the pool of the Stahl House. Although VKG sold “architectural pottery” in their design gallery, many of the large white planters both inside and outside the house were Koenig’s, which he brought over from his own house along with several outdoor pieces. For the interior, Van Keppel selected a different line of metal VKG pieces to parallel the thin lines of Koenig’s architecture. The furniture and other household goods made of steel and aluminum reflected the materials used in the construction.

Other pieces included a couch; a coffee table; side tables by Greta Grossman, made by Brown Saltman; and a chair, ottoman, and chaise by Stanley Young, made by Glenn of California. For the kitchen, Van Keppel arranged a set of Scandinavian pieces: Herbert Krenchel’s Krenit bowls made by Normann Copenhagen, Kobenstyle cookware by Jens Quistgaard for Dansk, and Descoware pans from Belgium.

Van Keppel placed the high-fidelity audio player in the dining area. The unit was from the A.E. Rediger Furniture Company, which also provided the kitchen appliances. The Prescolite lighting company, whose products ranged from commercial and industrial products down to desk lamps, provided the three large white-glass hanging globe lights: two inside, one outside (more than 55 years later, only the outside globe has been replaced).

The Stahls had the option to buy the furnishings, but as their daughter later said in a Los Angeles Times story about the house, “My mother always said she wished they would have left it, but my parents didn't have the money at the time.”

The popularity of Shulman’s photograph with the two girls speaks to the era’s postwar optimism and could be said to represent aspirational middle class ideals. Shulman received a variety of accolades for the photograph beginning in 1960, when he won first prize in the color category for architectural photography from the Architects Institute of America—the first time the AIA gave an award for a color photograph. As part of a traveling program arranged through the Smithsonian Institution, hundreds of people saw the photograph at nearly a dozen museums and university art galleries across the country from 1962 to 1964.

Then, as now, the photograph with the two girls is more often associated with its photographer than with the architect. “People request the photograph, or an editor or publisher writing to me or calling me says, ‘I want the picture of the two girls,’” Shulman explains. “They don’t say the Pierre Koenig house. All they ask is the picture of the two girls. That’s what creates an impact. This picture is now the most widely published architectural picture in the world since it was taken in 1960.”

That was not always the case. After the photograph first appeared as the cover for the Los Angeles Examiner Pictorial Living section, it virtually disappeared. Koenig told LaFetra: “That was the last of it until Reyner Banham was going through Julius’s file and he saw the picture of the two girls and he said ‘Oh, I like this. Can I use this?’ and Julius said, ‘Sure.’ [Banham] used it in one of his articles and it took off, it just caught on like crazy.” The photograph resurfaced in Banham’s essential 1971 book, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies .

Smog , the first Italian film produced in the United States, as noted by the New York Times , was shot entirely in Los Angeles.

The story’s central character is a formal, class-conscious, wealthy Italian lawyer played by Enrico Maria Salerno. En route to Mexico for a divorce case, he arrives at LAX for an extended layover. A representative from the airline encourages him to leave the airport and return later for his flight. He begins a 24-hour odyssey that involves meeting several Italians making new lives for themselves, having left Italy and its postwar political and economic struggles.

One of the expatriates Salerno meets in Hollywood is a woman, played by Annie Girardot, who is conflicted by her independence. The Stahl House features prominently as Girardot’s home. To varying degrees, the characters, especially Salerno and Girardot, struggle with the contradictions of modern life and tradition, resulting in feelings of alienation, hope, and despair. Emotionally, Smog is an Italian story transplanted to Los Angeles, where the characters’ psychological landscape parallels the topography of the city, incorporating the city’s air pollution as a character.

Curiously, the film credits an entirely different residence—the Geodesic Dome House designed by Bernard Judge—and that property’s owner, industrial designer Hendrik de Kanter. Neither the Stahls, their home, nor Koenig are acknowledged. Along with Judge’s appearance in a party scene, the error perpetuates the misidentification of the Stahl House in the film.

CSH No. 22 remains virtually unchanged since Smog was released. Its countless media appearances since then continue to convey the ideals and lifestyle represented by the house. Its influence is cross-generational and international: Instead of perpetuating an architectural cliche of residential living, the house is symbolic and inspirational; its identity and feeling are unmistakable. Rarely has a combination of client and architect, minimal use of materials, and uncomplicated design created such lasting dramatic impact.

Editor: Adrian Glick Kudler

How to Avert the Next Housing Crisis

The neighbors issue, can a neighborhood become a network, loading comments..., share this story.

Julius Shulman: Remembering the Illustrious Photographer

Julius Shulman

Julius Shulman at the Malin House , or Chemosphere , designed by John Lautner.

Photo © Juergen Nogai

Case Study House No. 22 , or Stahl House , Los Angeles, 1960. Architect: Pierre Koenig. House was built in 1959.

Photo © J. Paul Getty Trust/Julius Shulman Photography Archive

A shot of Julius Shulman outside Case Study House No. 22 , 1960.

Case Study House No. 21 , or Bailey House , 1960. Architect: Pierre Koenig. House was built in 1959.

Kaufmann House , Palm Springs, 1947. Architect: Richard Neutra. House was built in 1947.

Freeman House , Hollywood Hills. Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright. House was built in 1924.

Malin House, or Chemosphere , Los Angeles, 1961. Architect: John Lautner. House was built in 1960.

Frey House Addition , Palm Springs, 1953. Architect: Clark & Frey. House was built in 1940; addition was constructed in 1953.

Lovell “Health” House , Los Angeles, 1950. Architect: Richard Neutra. House was built in 1929.

The Castle , Los Angeles, 1966 or 1968. In this photograph, the Union Bank towers above a few remaining homes on Bunker Hill.

Bullock’s Wilshire Department Store , Los Angeles, 1969. Architect: John and Donald Parkinson. Building was completed in 1929.

Academy Theatre , Inglewood, 1940.

Century Plaza Hotel , Los Angeles, 1966. Architect: Minoru Yamasaki. Building was completed in 1966.

Mobil Gas Station , Anaheim, 1956.

A shot of Julius Shulman outside the May House in Los Angeles, 1954.

Calendar Notes

- Visual Acoustics: The Modernism of Julius Shulman , a documentary film by Eric Bricker, is slated for theatrical release in October.

- Julius Shulman & Juergen Nogai, exhibition at Craig Krull Gallery, Bergamot Station, 2525 Michigan Avenue, Building B-3, Santa Monica, CA 90404; July 4-August 22.

After a career spanning seven decades—and a client list running the gamut from Neutra to Rudolf Schindler, Frank Lloyd Wright, Charles and Ray Eames, John Lautner, Eero Saarinen, Mies van der Rohe, and many others, both famous and little known—the legendary architectural photographer died on July 15, a few months shy of his 99th birthday. Though he’d never met an architect until his mid-twenties nor aspired to a career behind a camera, he revolutionized the barely existent field of architectural photography.

Born in Brooklyn, to immigrant Russian Jewish parents, on October 10, 1910, he grew up on a Connecticut farm until his family moved to Los Angeles when he was 10. As a Boy Scout and through much of his life, he hiked the local mountains, cultivating a love of nature and awareness of light, which, he later suggested, deeply influenced his photography. Though he earned an A in the only photographic course he ever took (in high school) and sold occasional snapshots while briefly attending college at UCLA and Berkeley, he fell into a photographic career by chance.

In 1936, an acquaintance, who worked for Neutra, asked Shulman to take a few shots (with his amateur Kodak Vest Pocket camera) of the architect’s nearly completed Kun House in the Hollywood Hills. Neutra liked the images and hired the photographer for subsequent projects, soon introducing him to an entire community of leading and emerging architects. As Shulman told The Los Angeles Times in 1994: “I was lucky to be doing the right thing at the right place at the right time. Anytime anybody wanted a photograph of a modern house, Uncle Julius provided the picture.”

But he didn’t just photograph California Modernist houses. Gas stations, tract housing developments, urban sites, and more, all across the United States (plus a few in Europe and South America), inhabit the Julius Shulman archive of 260,000 negatives, prints, transparencies, and related materials, acquired by the Getty Research Institute (GRI) in 2005. The photographer’s original goal, as he often described it, was to “sell architecture”—often promoting the Case Study ideal of a casual, sunbathed, indoor-out lifestyle—to the editors and readers of the consumer and architectural magazines. “Though he photographed many extraordinary buildings,” says Wim de Wit, GRI’s curator of architectural collections, “he could also take something absolutely ordinary and make it glow.”

While most previous architectural photography was straightforward documentation, Shulman, working mostly in rich, silvery black-and-white, gave his compositions a dynamic and stylish glamour—often animating a scene with people, sometimes notoriously propping in branches for instant landscaping. His passion for architecture was palpable. And he never needed a light meter. “He totally understood light, especially in Southern California,” says de Wit. “He could just walk around a building and say, ‘I’ll be back at 10:43,’ knowing instinctively, or from experience, that the light would be exactly right then.”

His worldview fit the Modernist era. “He was the most optimistic person I’ve ever known,” recalls Craig Krull, whose Santa Monica, California, gallery represents Shulman. “That outlook perfectly suited a ‘translator’ of Modernism’s optimistic spirit—with its belief in the promise of the future and the capacity of technology to improve civilization.” The photographer’s own 1949 home in the Hollywood Hills, a commission he entrusted to architect Raphael Soriano, epitomizes the period.

Though Shulman “retired” more than once (the first time, he suggested, in protest against Postmodernism), he kept bouncing back. His last comeback, in 1999, launched a decade-long collaboration with Nogai. Twice widowered, the late photographer is survived by his only child, Judy McKee, and a grandson.

Over the years, Shulman spoke out for environmental, architectural, and urban causes, opposing, in particular, developer-driven sprawl. Since he was often hired to revisit earlier subjects (such as the Kaufmann House), his legacy includes an invaluable record of the evolution of key buildings and their surroundings.

As Shulman, whose excitement about his work never diminished, summed it up a year ago: “In the right place at the right time and—wham!—70 years ago I became a photographer!” He flashed his trademark smile, and added, “It’s breathtaking.”

Share This Story

Post a comment to this article

Report abusive comment.

Restricted Content

You must have JavaScript enabled to enjoy a limited number of articles over the next 30 days.

Related Articles

An Eye Toward the Past: Remembering Architectural Photographer Cervin Robinson (1928–2022)

Remembering robert lautman, 85, architectural photographer.

Shulman Home & Studio by Raphael Soriano and Lorcan O'Herlihy Architects

The latest news and information, #1 source for architectural design, news and products.

Copyright ©2024. All Rights Reserved BNP Media.

Design, CMS, Hosting & Web Development :: ePublishing

Iconic Photos

Famous, Infamous, and Iconic Images

Case Study House No. 22, 1960

Between 1945 and 1966, Californian magazine Arts & Architecture asked major architects of the day to design model homes. The magazine was responding to the postwar building boom with prototype modern homes that could be both easily replicated and readily affordable to the average American. Among many criteria given to the architects was to use “as far as is practicable, many war-born techniques and materials best suited to the expression of man’s life in the modern world.”

Thirty-six model homes were commissioned from major architects of the day, including Richard Neutra, Raphael Soriano, Craig Ellwood, Charles and Ray Eames, Pierre Koenig, Eero Saarinen, A. Quincy Jones, and Ralph Rapson. Not all of them were built but some thirty of them were, mostly around the Greater Los Angeles area.

The magazine also engaged an architectural photographer named Julius Shulman to dutifully record this experiment in residential architecture. Fittingly for Shulman, one of the first architectural photographers to include the inhabitants of homes in the pictures, his most famous image was the 1960 view of Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House No. 22 (also the Stahl House), which showed two well-dressed women conversing casually inside.

In the photo, the cantilevered living room appears to float diaphanously above Los Angeles. “The vertiginous point of view contrasts sharply with the relaxed atmosphere of the house’s interior, testifying to the ability of the Modernist architect to transcend the limits of the natural world,” praised the New York Times . Yet this view was created as meticulously as the house itself. Wide-angle photography belied the actual smallness of the house; furniture and furnishings were staged, and as were the women. Although they were not models (but rather girlfriends of architectural students), they were asked to sit still in the dark as Shulman exposed the film seven minutes to capture lights from LA streets. Then, lights inside were quickly switched on to capture two posing women.

Case Study House No.22 as it appeared in Arts and Architecture . Shulman’s photo with inhabitants did not appear here.

See other Case Study Houses here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Case_Study_Houses

Result was the photo Sir Norman Foster termed his favorite “architectural moment”. Indeed, the photo captured excitement and promises the house held, and propelled Case Study No. 22 into the forefront of national consciousness. Some called it the most iconic building in LA. It appeared as backdrop in many movies, TV series and advertisements. Tim Allen was abducted by aliens here in Galaxy Quest ; Greg Kinnear would make it his bachelor pad in Nurse Betty , and Columbo opened its pilot episode here. Italian models in slicked-back hair would frolic poolside in Valentino ads. It was even replicated in the 2004 video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas. According to Koenig, Case Study No. 22. was featured in more than 1,200 books — more often than Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater.

0 thoughts on “ Case Study House No. 22, 1960 ”

does delta 8 get uou high

Good short article! Extremely instructive and effectively prepared. You coated the topic in good detail and presented fantastic examples to back up your factors. This information will be a terrific source for the people looking To find out more concerning the subject matter. Thanks for The good do the job!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Cookie banner

We use cookies and other tracking technologies to improve your browsing experience on our site, show personalized content and targeted ads, analyze site traffic, and understand where our audiences come from. To learn more or opt-out, read our Cookie Policy . Please also read our Privacy Notice and Terms of Use , which became effective December 20, 2019.

By choosing I Accept , you consent to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies.

Site search

- Los Angeles

- San Francisco

- Archive.curbed.com

- For Sale in LA

- For Rent in LA

- Curbed Comparisons

- Neighborhoods

- Real Estate Market Reports

- Rental Market Reports

- Homelessness

- Development News

- Transportation

- Architecture

Filed under:

- Hollywood Hills

- Midcentury Modern

Time Magazine names Stahl House photo one of the most influential in history

The Julius Shulman shot of an LA house helped reshape ideas of architecture and the American Dream

Time Magazine has trained its editorial eye on the millions of images produced in the nearly 200-year-old history of the photographic medium and come up with 100 that it deems the most influential in the history of the world. Appearing on that prestigious list is Julius Shulman’s iconic image of one of the most famous homes in Los Angeles: the Stahl House.

Also known as Case Study House No. 22, the home was designed by Pierre Koenig as part of the Case Study program sponsored by Arts & Architecture that showcased the works of some of California’s greatest modern architects. Perched in the Hollywood Hills, the glass-walled home seems to float above the lights of the city in Shulman’s brilliant photos—smartly taken both at night and during the day, when views from the pool deck are equally impressive.

The two women Shulman enlisted to pose within the glass-walled home look a little out of place among the burnt bodies and war-torn cities depicted in many of the other photos on the list, but it’s certainly true that Shulman’s photo significantly impacted contemporary attitudes toward modern architecture, Los Angeles, and even the American Dream.

At a time when a two-story home fronted by a green lawn and a white picket fence still embodied success for many Americans, Shulman’s shot presented a starkly different alternative: a dramatic, glassy box that seems to defy gravity—and yet still looks like home.

As Time argues, the picture “perfected the art of aspirational staging, turning a house into the embodiment of the Good Life, of stardusted Hollywood, of California as the Promised Land.”

- The Most Influential Images of All Time [Time Magazine]

- Mapped: The Case Study Houses That Made Los Angeles a Modernist Mecca [Curbed LA]

- LA's Most Famous House Finally Makes the National Register [Curbed LA]

- LA's Most Iconic House is at the Center of an Ugly Legal Battle [Curbed LA]

Next Up In Midcentury Modern

- Glendale Mid-Century Near 244-Acre Open-Space Preserve Asks $1.3M

- 1970s desert home with breeze blocks, pink trim asks $899K

- Perfectly preserved midcentury modern asking $2.2M in Pasadena

- Classic California modern in La Habra Heights seeks $1.1M

- Swinging ’60s modern in Palm Springs asking $1.1M

- 1950s post and beam below the Hollywood Sign asks $1.6M

Loading comments...

Share this story.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Picture Show

Daily picture show, julius shulman: 98 and still photographing.

Claire O'Neill

Read Susan Stamberg's Story on Shulman, Photographer Captures L.A.'s Vintage Homes

In 1960, Julius Shulman took a photograph that to this day remains the paragon of architectural photography. Case Study House #22 (below) shows the dreamlike, cinematic Los Angeles that has been etched into our collective conscious. Even at the age of 98, Shulman continues to take photographs with the help of his working partner Juergen Nogai. The two met about 10 years ago, and Shulman came out of retirement to work with the like-minded Nogai.

For full screen, click on the four-cornered arrow icon in the viewer's bottom right.

If you have an idea of what California looked like in the 1960s and '70s, Shulman is probably partially responsible for it. He has set the industry standard on many levels — for both architects and photographers alike.

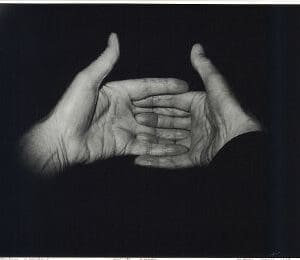

Despite a lifetime behind the lens, however, Shulman and Nogai both eschew the term photo shoot. "Shoot?" says Shulman, laughing. "Look at me. Do I have a gun? I'm a photographer." Nogai explains: "People are not thinking anymore; they're just shooting." Some would agree that the digital age has enabled a decrease in deliberation. If you can fill up a memory card with 1,000 images until you get the perfect one, after all, why stop to carefully compose?

But what most typifies a Shulman/Nogai photograph is meticulous composition that will guide your eye endlessly, if you allow it. These photographers are notorious for the amount of careful consideration that formulates each frame. They've spent up to nine hours on assignment to leave with a mere 11 frames. Eleven perfect frames, that is.

When describing their photographic process, Nogai explained his affinity for film, as well as his concerns about changes to the medium in general. "We're living in a world where everything is 'good enough.' It's not good anymore. And for me that means a reduction in quality." He has a digital Nikon D3x and rents digital backs for his film cameras. "I'm not saying digital photography is bad," he clarified, "but that it has a place."

There's a real concern among photographers who have long been in the industry — even among those who haven't — that their art is dying. They long to turn off their computer monitors and hold their prints in hand. Nogai's advice to aspiring photographers is to study, create a vision and tell a story. He and Shulman have been doing so for decades, and their photographs are a testament to that.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

- Newsletters

Inside L.A.’s Ultimate Mid-century Modern Home

By Mark Rozzo

All featured products are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, Vanity Fair may earn an affiliate commission.

In March 1954, Clarence “Buck” Stahl and Carlotta May Gates drove from Los Angeles to Las Vegas and got married in a chapel. They each worked in aviation (Buck in sales, Carlotta as a receptionist), had previous marriages, and were strapping, tall, and extremely good looking—California Apollonians out of central casting. Buck was 41, Carlotta, 24. Back home in L.A., as the newlyweds pondered their future, they became preoccupied with a promontory of land jutting out like the prow of a ship from Woods Drive in the Hollywood Hills, about 125 feet above Sunset Boulevard. It was as conspicuous as it was forbidding, visible from the couple’s house on nearby Hillside Avenue. “This lot was in pure view—every morning, every night,” Carlotta Stahl recalled. Locals called it Pecker Point, presumably because it was a prime makeout venue. For the Stahls, it became the blank screen on which they projected their dreams of a life together, a place to build a future, a family, and a house like no other.

Buck Stahl teaches his infant son Mark how to swim, 1967.

Carlotta with daughter Shari on the lounge chair and Bruce in the pool.

About two months after their dash to Las Vegas, the Stahls decided to drive up to this mystery spot and have a look around. They found themselves gawping at the entirety of Los Angeles spread out below in a grid that went on for an eternity or two. While they stood there, the owner of the lot rolled up. He lived down in La Jolla and rarely came to L.A. In the kismet-filled conversation that followed, Buck agreed to buy the barren one-eighth-acre lot for $13,500, with $100 down and the seller maintaining the mortgage until the Stahls paid it off. A handshake later, the couple owned 1635 Woods Drive. On that site, they would construct Case Study House #22, designed by Pierre Koenig, arguably the most famous of all the houses in the famous Case Study program that Arts & Architecture magazine initiated in 1945. For generations of pilgrims, gawkers, architecture students, and midcentury-modern aficionados, it would be known simply as the Stahl House.

The house in 1960, as captured by Julius Shulman during the day.

Sixty-one years since its completion, the modestly scaled L-shaped dwelling still exemplifies everything that is Californian and modern, a built metaphor in prefabricated steel and glass for Los Angeles itself. Yet the Stahl House—which began as a model that Buck fashioned out of beer cans and clay—transcends time and place. Its very image, as the architect Sir Norman Foster once wrote, embodies “the whole spirit of late 20th-century architecture.”

The family’s streamlined kitchen.

You probably know that image, the one Julius Shulman, the architectural photographer, created of the Stahl House in 1960, when the house was barely complete: black and white, twilight, a pair of seated women in conversation, the glass corner of the house cantilevering 10 feet out into nothing except a forever view of glistening, celestial L.A. In 2016, Time Magazine declared it one of the 100 most influential photographs of all time. “If I had to choose one snapshot, one architectural moment, of which I would like to have been the author,” Foster wrote, “this is surely it.” The image continues to hold sway over contemporary practitioners. “That photograph was pivotal in so many peoples’ lives,” the laureled Seattle-based architect Tom Kundig said. “I mean, is there any other photograph that captures in a single image the potential of architecture, the optimism of it? I don’t know if there is.”

Buck and his nephew, Robert, in front of his DIY model of the house.

Carlotta and a family friend (left) with Mark in 1967.

Thanks to a seven-and-a-half-minute exposure, Shulman had managed to capture a serenely futuristic, even utopian, tableau. But the shoot, with plaster dust everywhere and a furniture delivery man taking a detour to visit his mother in Kansas City, was chaos. The backstory of that photograph is one of many spun out in The Stahl House: Case Study House #22 , a sumptuous new book by two of the Stahls’ children, Bruce Stahl and Shari Stahl Gronwald, with the journalist Kim Cross. (Buck and Carlotta, and the youngest Stahl sibling, Mark, are no longer living.) “As kids,” the authors write, “we didn’t know our house was special. It was simply ‘home.’ ” Their book is a startlingly intimate document, chockablock with family snapshots, that goes beyond steel decking, glass walls, concrete caissons, and the geometry of H columns and I beams. It’s a love song to a global icon that was, for the residents themselves, no museum.

Shulman’s famous seven-minute exposure captures the house and its sprawling city backdrop.

As the Stahls tell it, the house may have been a modernist glass bubble, but the glass had smudgy handprints all over it. The towheaded Stahl kids liked to roller-skate across the concrete floors and got up to the usual youthful japery—setting Barbies afire and the like. Jumping off the dramatic, oversailing roof into the swimming pool was an important rite, one eventually passed down to the Stahls’ grandchildren. Buck would shout for the kids to “aim for the drain,” meaning the deep end, and they would take flight, the turquoise water rushing toward them and sky all around. The pool was the center of everything. Shari once rode her tricycle into it, and Bruce developed into a champion swimmer who broke the world record for the 50-meter freestyle. Carlotta, for her part, made delicious treats in a kitchen outfitted with pink GE appliances. Adolf Loos’s dictum “ornament is crime” may have animated Koenig’s minimalist design, but she went to town on a tucked-away powder room: floral wallpaper, shag carpet, framed embroidery, and plastic daisies. Buck was the kind of dad who built the children’s nightstands himself; the Stahls’ decor was no high-end fantasia of Eames, Knoll, and Nelson. Like the prototypical postwar suburban family, the Stahls made do and got by.

Eventually, the Stahl House, like all midcentury houses, fell out of fashion. But in 1989 it was rebuilt, in replica, as the star attraction of the “Blueprints for Modern Living” show at L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art, a surreal experience for the Stahls, who strolled through a parallel-universe version of their family home that had been styled as if for a Hollywood production. And then, more and more, real productions began beating a path up to the real Stahl House: movies, television, Vogue shoots. In 1990, the vocal trio Wilson Phillips filmed the video for their hit “Release Me” there, with director Julien Temple evoking Shulman’s famous photograph. For Carnie Wilson, one of the singers, the experience was the apotheosis of all things Los Angeles. “Here we were in a house that overlooked all of L.A., thinking of the Beach Boys and the Mamas and the Papas,” she said, referring to the group’s pop-royalty parentage. “It just felt all encompassing there.” Modernism came back in style and the Stahl House, owned by the Stahl family to this day and open to hundreds of visitors on guided tours every year, became one of the most photographed buildings in the world. The house was even a guest star on The Simpsons. It doesn’t get much more pantheonic than that.

“When I built in steel, what you saw was what you got,” the plain-spoken Koenig once said. What Buck and Carlotta Stahl got when they drove up to Woods Drive in 1954 was more than they ever envisioned. “They simply built their dream home,” their children write. It’s a dream that never ends.

Photos excerpted from The Stahl House: Case Study House #22: The Making of a Modernist Icon by Shari Stahl Gronwald, Bruce Stahl, and Kim Cross, published by Chronicle Chroma 2021.

All products featured on Vanity Fair are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

— A Messy Vaccinated Wedding Season Has Arrived — How Harry and Meghan Decided On the Name Lilibet Diana — Black Joy Comes to Shakespeare in the Park — Even More Kanye West and Irina Shayk Details Emerge — The Bennifer Story Really Does Have Everything — Ahead of the Diana Tribute, Harry and William Are Still Working On Their Relationship — Tommy Dorfman on Rewriting Queer Narratives and the Smell of Good Sweat — From the Archive: A Spin on the Top DJs in the World — Sign up for the “Royal Watch” newsletter to receive all the chatter from Kensington Palace and beyond.

Royal Watch

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Chris Murphy

By Julie Miller

By Eve Batey

By Bess Levin

Your Shopping Cart

Your shopping cart is empty!

- About Julius

Julius Shulman – Case Study House #28. Thousand Oaks, Ca. -Buff, Straub & Hensman. 1966

$ 795.00

Description

Photographer: Julius Shulman

Subject: Case Study House #28

Location: Thousand Oaks, California

Architects: C. Buff, C. Straub, D. Hesman

Job: 4037-1

Year: 1954 / 1956

Assignment: Buff, Straub & Hensman

This Julius Shulman Print arrives with a “Certificate of Authenticity” authorized by the “Julius Shulman Trust & Photographic Archives”