- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

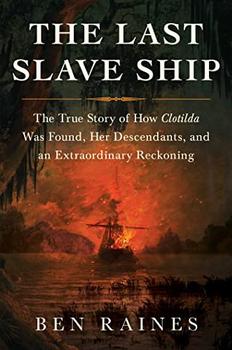

The Last Slave Ship review: the Clotilda, Africatown and a lasting American injustice

Ben Raines offers a welcome and affecting history lesson about a dark moment in US history and how its legacy lingered

In 1903, the African American comedic team of Bert Williams and George Walker appeared at Buckingham Palace, in celebration of the ninth birthday of the grandson of King Edward VII.

To acclaim, they reprised their Broadway hit, In Dahomey. The musical play featured the cake walk, which became a dance sensation, and a madcap plot set in Boston, Florida and the African nation now famed for royal bronzes plundered by imperialists. What, one wonders, did their audience know of Dahomey’s more sinister legacy?

“Of all our studies,” said Malcolm X, “history is best qualified to reward our research.” In our uncertain times, Ben Raines’s perceptive new book , The Last Slave Ship: The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning, is a welcome and affecting history lesson.

This story from long ago puts into context what the new spate of lawlessness in the US is all about. Raines tells a tale of racism and greed. Anyone who imagines that attempting to circumvent democracy is a new thing has forgotten the civil war.

Raines begins in 1860, 50 years after the Atlantic slave trade was outlawed. That was when a sleek, custom-built schooner, the Clotilda, returned to Mobile, Alabama , from Dahomey, which nowadays is known as Benin. Chartered by a planter and riverboat captain, Timothy Meaher, the Clotilda carried a valuable cargo: 110 young black captives. Meaher had made a thousand-dollar bet with passengers at the captain’s table. He could pull off the caper of bringing a boatload of enslaved Africans to Mobile – a capital offense – without consequence. Spoiler alert! He did.

For many, one suspects, the most enlightening part of this sad saga occurs at the start. Some who have heard of the direct involvement of Africans in the Atlantic slave trade have suspected apologists’ propaganda. True, as with today’s drug trade, without a lucrative market among Arabs, Europeans and Americans, slavery would have collapsed much sooner. But there is no exaggerating the extent to which the rulers of Dahomey were involved in capturing fellow Africans for both enslavement and sacrifice. Its victims are estimated in the hundreds of thousands.

Meaher and his accomplices decided it was prudent to destroy the evidence. In Mobile, William Foster, the captain who carried out the venture, set the Clotilda ablaze and scuttled her. Soon to resign from US law enforcement to join the Confederacy, the gang’s prosecutors probably knew where the vessel lay. But with plausible deniability, they maintained there was no evidence criminality had occurred.

Five years later, at civil war’s close, the Africans hit on a stratagem to restore their dignity. They determined to acquire land and establish a realm of their own. They called it Africatown. Predictably, their leader was rebuffed by their captor.

“Thou fool,” Meaher is said to have shouted. “Thinkest thou that I would give you property upon property? You do not belong to me now … I owe you nothing.”

The group of 30 ex-captives continued to toil in the cotton fields, on Meaher’s boats and at his saw mill. Saving most of what they earned, they bought land from Meaher. Collectively, they built solid if meager houses. They built a church and a school.

In much the same terms as whites disdained them, African Americans ridiculed and ostracized the Clotilda captives and their offspring. They denounced them as ignorant, savage and ape-like. It’s little wonder their descendants came to lose the language of their ancestors and often to deny their heritage too.

Once a highway and bridge connected Africatown to Mobile, three miles across the bay, more and more American-born Black people moved there. By the 1920s, when the Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston came to document the Africans, there were small houses for black factory workers. Black-owned businesses arose too: movie theaters, grocery stores, barber shops, beauty parlors. By the 1950s, the population was 13,000.

In the Jim Crow south, such autonomy was largely illusory. Unincorporated, unprotected by zoning or environmental regulations, Africatown was prey to exploitation. Privately held African property proved no match to eminent domain. Relative prosperity was no compensation for those employed by toxic factories, prey to chronic illness.

Just like that, the boom times went away. Factories closed and rather than pay taxes for sewer connections the Meahers destroyed houses after evicting tenants. In 1967, Augustine Meaher explained his position: renters couldn’t afford water bills on top of $4 monthly rent.

“Besides, people have lived perfectly healthily and happy for years without running water and sewers … He don’t need garbage service … He don’t need a bathtub … Wouldn’t know how to use it.”

Timothy Meaher’s grandson also said his company might keep a few houses for the old “darkies who work for us” but with pensions from the government, “you can’t get them to work as hard any more.”

Construction of an even bigger bridge, which destroyed the last of the original houses, presaged wholesale abandonment. With the population down to 3,000, crime, crack and despair pervaded. Now only the cemetery and the chimney of one of the founder’s houses survive.

However, the raising of the Clotilda, three years ago , has sparked an Africatown renaissance. The “discovery” refuted the lies of whites who maintained that the capture and displacement of 110 Africans never happened. Still fabulously rich, the Meahers of Mobile are as yet unrepentant. Or at least they are silent.

Mike Foster is not. As a direct descendant of Meaher’s agent and the captain of the Clotilda, news of the ship’s discovery roused him. Meeting Lorna Gail Woods, Joycelyn Davis, Darron Paterson, Garry Lumbers and two other members of the Clotilda Descendants Association, he offered an apology.

The heirs of Africatown stress that as they want reconciliation, so does Foster. And that they’ll achieve it.

The Last Slave Ship is published in the US by Simon & Schuster

- History books

Most viewed

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Shipwreck Leads to a Reckoning

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

By W. Caleb McDaniel

- Jan. 25, 2022

THE LAST SLAVE SHIP The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning By Ben Raines

On Election Day in Alabama in 1874, Cudjo Lewis, Pollee Allen and Charlie Lewis appeared at their polling place to cast their ballots, only to be stopped by Timothy Meaher, the man who had once enslaved them.

“See those Africans?” Meaher told election officials. “Don’t let them vote. They are not of this country.” They were turned away.

Such confrontations occurred across the Reconstruction South as white reactionaries sought to wrest the ballot from Black voters. But this experience was unique. Unlike African Americans whose ancestors had endured the Middle Passage in previous generations, these three men had been born in Africa and only brought to the United States in 1860, on a slave ship called the Clotilda.

Financed by Meaher and captained by William Foster, the ship had traveled from Alabama to present-day Benin, where Foster purchased slaves in defiance of federal and international bans on the Atlantic slave trade. After a perilous six-week return journey, the Clotilda arrived near Mobile with 110 Africans, who were forced to disembark, naked, under cover of night.

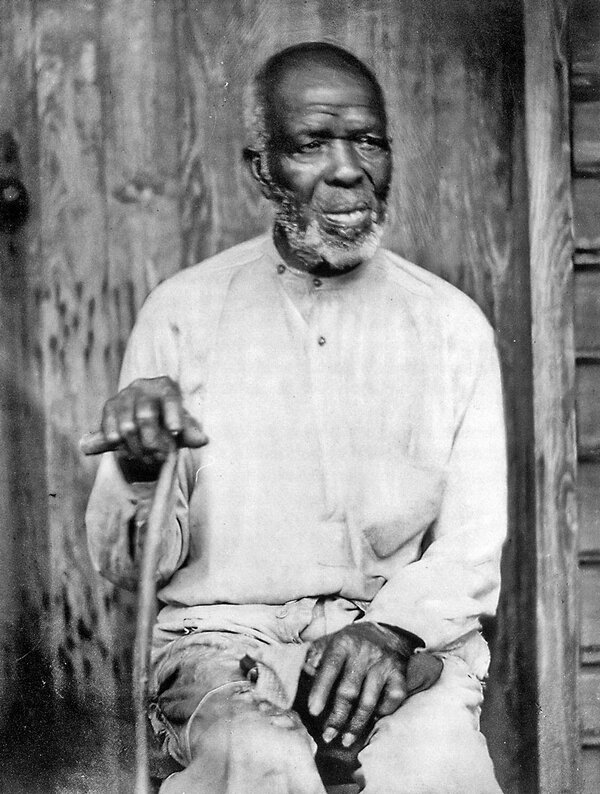

One of them was a 19-year-old called Kossula, who later took the name Cudjo Lewis and remained in Alabama until his death in 1935; another was Sally “Redoshi” Smith, who lived until 1937. They were the last survivors of the last recorded voyage of a slave ship from Africa to the United States.

The Clotilda itself was burned and sunk by Meaher and Foster to bury their crime. Its remains seemed lost forever until 2018. That’s when the author Ben Raines lifted a piece of wood with a large square nail from a submerged shipwreck off Twelve Mile Island in the Mobile River. A year later, archaeologists confirmed he had found the Clotilda, revitalizing efforts to memorialize the shipmates. In “The Last Slave Ship,” Raines reports on that discovery and its aftermath.

The fast-paced narrative begins with the voyage and follows the Clotilda’s survivors beyond the Civil War. After emancipation, many of the captives reunited from the plantations where Meaher had divided them. They hoped to return home. When this proved impossible and Meaher refused to repay them with land, the group saved money to purchase plots from him and other former enslavers, establishing a community in Alabama called Africatown.

Though much diminished today, the place survives, a monument to its founders’ courage. As Raines writes, “They stuck together and they fought back.” Even after Meaher challenged their right to vote in 1874, Cudjo, Pollee and Charlie (all naturalized citizens) eventually cast their votes at a different poll in Mobile, outwitting their former enslaver.

We know that story because the shipmates later dared to recount it. In the early 20th century, at the height of Jim Crow, Emma Langdon Roche interviewed residents of Africatown and published many of their stories. In 1927, Zora Neale Hurston visited Cudjo Lewis. He told her about the raid on his village by Dahomean warriors, who killed his family members and kidnapped those later forced onto the Clotilda. “Barracoon,” Hurston’s account of those conversations, was published in 2018.

Raines relies on these and other accounts to retell the captives’ story, while also sketching the geopolitical context that led Meaher to wager, correctly, that he could violate a congressional ban on international slaving (in effect since 1808) and get away with it.

The book makes some missteps. The founders of Africatown were not the first freed people to seek land or reparations, as Raines implies. Efforts to reopen the slave trade in the 1850s were not actually driven by fears of a “collapsing Southern economy.” Readers looking to better understand American complicity in trans-Atlantic slaving before the Civil War should consult John Harris’s “The Last Slave Ships,” plural. Detailed accounts of the Clotilda and Africatown have been published by Natalie S. Robertson and by Sylviane Diouf, whose scholarship Raines credits for helping him to locate the vessel.

What distinguishes Raines’s book is not only the story of that discovery, but also his perspective as a river guide in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta, the subject of his previous book, “Saving America’s Amazon.” Raines vividly conjures the watery landscape into which the Africans stepped, an alligator-filled swamp once thick with canebrake, now transformed by hydroelectric dams. Knowledge of these waterways also led Raines to locate the Clotilda in a place previous searchers had ignored.

Raines’s work as an environmental reporter helps him explain Africatown’s modern struggles, too. In 1927, a new freeway bridge was built that split the community. Heavy industry moved in, as Meaher’s descendants, still large landowners, leased real estate to paper mills. Their smokestacks rained ash and other harmful pollutants on the town the shipmates had built.

The 1960s incorporation of Africatown into Mobile brought city utilities but also more industry. As developers and landlords destroyed housing stock, many residents of the once thriving Black community left. Cudjo Lewis’s home was torn down. The area is now blighted by toxic landfills overseen by officials who view federal environmental regulation as disdainfully as Meaher once viewed Congress’s ban on the slave trade. A small welcome center housed in a mobile home was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

Today, activists and descendants hope that new grants for tourism centered on the Clotilda can finally bring needed resources to the community. One states his goal to Raines: “Making right what they’ve done to Africatown all these years.”

What does “making right” mean? Raines addresses that question in two final chapters. The first pivots abruptly to a trip to Benin, where Raines finds parallel efforts to boost tourism related to the slave trade and interviews a pastor who preaches “reconciliation” between descendants of the perpetrators and survivors of slavery. In a coda, Raines reports on a meeting between Darron Patterson, president of the Clotilda Descendants Association, and Mike Foster, a great-great-great-grandson of the Clotilda captain’s brother. After a nervous apology from Foster, he and several Clotilda descendants share hamburgers, hugs, laughter and tears at a bar called Kazoola’s, in homage to Cudjo Lewis’s African name. Raines writes that “reconciliation had begun.”

Yet given what Raines has related about the traumas of slavery, racial injustice and the powerful forces that despoiled Africatown, that moment feels less like repair than the smallest of starts.

Raines was unable to get direct descendants of Foster or Meaher to talk on the record or share artifacts. Before he died in 2020, Joe Meaher, great-grandson of the ship’s financier, told another writer that he and his father had once secretly dynamited parts of the wreck. And as recently as 2012, while Africatown foundered, Joe Meaher and his brothers held real estate valued at $35 million. Today, when Raines takes visitors to the shipwreck, he launches his boat from a state park named for one of the Meahers, who mostly “appear uninterested in reconciliation.”

Recently, archaeologists announced that the Clotilda itself is remarkably well preserved, confirming its international importance. But community members remain at odds with local officials, and sometimes with one another, over key questions: whether the Clotilda should be raised, what kind of museum it deserves and what “making right” requires.

Clearly, the story of the last slave ship is still far from over, and the “extraordinary reckoning” hinted at by Raines’s subtitle has barely begun.

W. Caleb McDaniel is the author of “Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America,” which won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for history.

THE LAST SLAVE SHIP The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning By Ben Raines Illustrated. 303 pp. Simon & Schuster. $26.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE LAST SLAVE SHIP

The true story of how clotilda was found, her descendants, and an extraordinary reckoning.

by Ben Raines ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 25, 2022

A highly readable, elucidating narrative that investigates all the layers of a traumatic history.

The complex history behind the recent discovery of the last known slave ship to convey Africans to the U.S. before the Civil War.

In 2019, environmental journalist Raines, who lives in Alabama, helped unearth from the muddy delta outside Mobile the sunken remains of the schooner Clotilda , which made its infamous run to the west coast of Africa in July 1860 and returned carrying 110 slaves. “This is the story of that ship,” writes the author, “the people shaped by her complex legacy, and the healing that began on both sides of the Atlantic when her wooden carcass finally came to the surface.” Although importing Africans for slavery had been illegal since 1807, the cost of cotton had skyrocketed, and the South desperately needed cheap labor. Timothy Meaher, the racist Alabama steamboat captain who organized the Clotilda ’s voyage, acted partly out of a bet, partly to make a fortune from human cargo, but mostly to defy federal enforcers. Raines weaves an impressively multilayered story, building on some of the information he provided in his previous book, Saving America’s Amazon (2020). The author discusses the reckless slave-owning Southern aristocracy and the brutal slave-capturing and -running Kingdom of Dahomey (now Benin), which “may have been responsible for capturing and deporting about 30 percent of all the Africans sold into bondage worldwide between 1600 and the 1880s.” Raines also focuses on the resilient community of Africatown, which the survivors of the Clotilda created outside of Mobile in the aftermath of the war. Sadly, the survivors could not raise the money to fund their return to Africa, but their town thrived, and they forged a community on their own terms. Raines should be commended for his dogged journalistic work locating the sunken ship, which the owners tried to destroy, as well as the descendants of those original enslaved Africans.

Pub Date: Jan. 25, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-982136-04-8

Page Count: 304

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Review Posted Online: Oct. 11, 2021

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Nov. 1, 2021

HISTORY | AFRICAN AMERICAN | UNITED STATES | WORLD

Share your opinion of this book

More by Ben Raines

BOOK REVIEW

by Ben Raines ; photographed by Ben Raines

by Max Cleland with Ben Raines

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2017

New York Times Bestseller

IndieBound Bestseller

National Book Award Finalist

KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON

The osage murders and the birth of the fbi.

by David Grann ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 18, 2017

Dogged original research and superb narrative skills come together in this gripping account of pitiless evil.

Greed, depravity, and serial murder in 1920s Oklahoma.

During that time, enrolled members of the Osage Indian nation were among the wealthiest people per capita in the world. The rich oil fields beneath their reservation brought millions of dollars into the tribe annually, distributed to tribal members holding "headrights" that could not be bought or sold but only inherited. This vast wealth attracted the attention of unscrupulous whites who found ways to divert it to themselves by marrying Osage women or by having Osage declared legally incompetent so the whites could fleece them through the administration of their estates. For some, however, these deceptive tactics were not enough, and a plague of violent death—by shooting, poison, orchestrated automobile accident, and bombing—began to decimate the Osage in what they came to call the "Reign of Terror." Corrupt and incompetent law enforcement and judicial systems ensured that the perpetrators were never found or punished until the young J. Edgar Hoover saw cracking these cases as a means of burnishing the reputation of the newly professionalized FBI. Bestselling New Yorker staff writer Grann ( The Devil and Sherlock Holmes: Tales of Murder, Madness, and Obsession , 2010, etc.) follows Special Agent Tom White and his assistants as they track the killers of one extended Osage family through a closed local culture of greed, bigotry, and lies in pursuit of protection for the survivors and justice for the dead. But he doesn't stop there; relying almost entirely on primary and unpublished sources, the author goes on to expose a web of conspiracy and corruption that extended far wider than even the FBI ever suspected. This page-turner surges forward with the pacing of a true-crime thriller, elevated by Grann's crisp and evocative prose and enhanced by dozens of period photographs.

Pub Date: April 18, 2017

ISBN: 978-0-385-53424-6

Page Count: 352

Publisher: Doubleday

Review Posted Online: Feb. 1, 2017

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 15, 2017

GENERAL HISTORY | TRUE CRIME | UNITED STATES | FIRST/NATIVE NATIONS | HISTORY

More by David Grann

by David Grann

More About This Book

BOOK TO SCREEN

THE EARP BROTHERS, DOC HOLLIDAY, AND THE VENDETTA RIDE FROM HELL

by Tom Clavin ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 21, 2020

Buffs of the Old West will enjoy Clavin’s careful research and vivid writing.

Rootin’-tootin’ history of the dry-gulchers, horn-swogglers, and outright killers who populated the Wild West’s wildest city in the late 19th century.

The stories of Wyatt Earp and company, the shootout at the O.K. Corral, and Geronimo and the Apache Wars are all well known. Clavin, who has written books on Dodge City and Wild Bill Hickok, delivers a solid narrative that usefully links significant events—making allies of white enemies, for instance, in facing down the Apache threat, rustling from Mexico, and other ethnically charged circumstances. The author is a touch revisionist, in the modern fashion, in noting that the Earps and Clantons weren’t as bloodthirsty as popular culture has made them out to be. For example, Wyatt and Bat Masterson “took the ‘peace’ in peace officer literally and knew that the way to tame the notorious town was not to outkill the bad guys but to intimidate them, sometimes with the help of a gun barrel to the skull.” Indeed, while some of the Clantons and some of the Earps died violently, most—Wyatt, Bat, Doc Holliday—died of cancer and other ailments, if only a few of old age. Clavin complicates the story by reminding readers that the Earps weren’t really the law in Tombstone and sometimes fell on the other side of the line and that the ordinary citizens of Tombstone and other famed Western venues valued order and peace and weren’t particularly keen on gunfighters and their mischief. Still, updating the old notion that the Earp myth is the American Iliad , the author is at his best when he delineates those fraught spasms of violence. “It is never a good sign for law-abiding citizens,” he writes at one high point, “to see Johnny Ringo rush into town, both him and his horse all in a lather.” Indeed not, even if Ringo wound up killing himself and law-abiding Tombstone faded into obscurity when the silver played out.

Pub Date: April 21, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-250-21458-4

Page Count: 400

Publisher: St. Martin's

Review Posted Online: Jan. 19, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 15, 2020

GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | GENERAL HISTORY | BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | HISTORICAL & MILITARY | UNITED STATES | HISTORY

More by Tom Clavin

by Tom Clavin

by Bob Drury & Tom Clavin

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

“The Last Slave Ship: The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning" By: Ben Raines

“The Last Slave Ship: The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning”

Author: Ben Raines

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Price: $27.99 (Hardcover)

On April 9, 2018, after years of research and some disappointments, Ben Raines of Fairhope, Alabama, in SCUBA gear, dove to the bottom of the Mobile River on the east side of Twelve Mile Island and brought up a piece of the “Clotilda.” That ship, the last ship to bring slaves to America, had lain undiscovered for over one hundred and fifty years.

With eloquent prose and a controlled, if sometimes nearly incredulous tone, Raines tells the story of that ship’s last voyage, the forces that prompted the voyage, and the fate of the Africans who were brought across the Atlantic in the hold of that ship, down to the present day.

In the beginning was the bet.

Multimillionaire Timothy Meaher of Mobile made a bet of $1,000—$30,000 in today’s dollars—that he could send a ship to Africa, buy slaves there and return safely to Mobile. The international slave trade had been outlawed since 1808, so, if caught, the punishment could be hanging.

It should be noted that Meaher did not go himself.

He hired Captain William Foster whose payment would be ten of the captives, and fitted out the “Clotilda” to carry prisoners. At about 86 feet, she was small but fast.

Among the many astonishing revelations in Raines’ book is the story of the Kingdom of Dahomey.

As a boy I had no real idea of how westerners captured Africans and brought them back. I may have had some notion of Portuguese sailors going ashore themselves on a raid.

That didn’t happen much, if at all.

As Raines describes, the kingdom of Dahomey was entirely organized around this venture. There were 50,000 warriors, one fourth of the entire population. It was a Sparta but with ferocious Amazon warriors as well as males. The Dahomans raided neighboring villages, killing and beheading everybody not between 12 and 30 and bringing the rest back in chains to the barracoons near the shore to sell to westerners. This went on for 250 years, with hundreds of thousands captured and sold. They sold tens of thousands per year for about $50-60 apiece.

You have never heard anything like it.

Foster returned in July of 1860 with 110 Africans.

One able-bodied male brought perhaps $1200-1400, $50,000 in today's money.

Meaher off-loaded the captives, worth 6 million dollars in today’s cash, then burned and sank the ship to avoid discovery. In fact, no one was ever punished for this crime, but that is just the first chapter in this incredible story.

The enslaved aboard the “Clotilda” had grown up together, knew one another, and in servitude around Mobile, they still communicated.

They had their established customs. For example, they would NOT be struck. A field hand, struck by an overseer, would fight back, joined by his mates. A house servant, slapped, set up a wail heard all over the plantation. Dozens came to her rescue.

Five years later, when the Civil War ended, these 110 people were freed but the story continues. Unlike the legions of other enslaved people, they remembered life in their home village. They knew perfectly well how to be free. After trying unsuccessfully to save enough money to return to what is now Benin, they bought land, which they named Africatown, and set up a village government with hierarchies of leadership, their own judicial system. They farmed, opened businesses, cooperated, built a church, a school.

Much of what we know about life in Africa and early Africatown, we learned from Cudjo Lewis who lived long enough—until 1935—to be interviewed extensively by Zora Neale Hurston among others.

The town thrived for decades. In the ’70s the population was 12,000. Then the Meahers, still local rich folk, bulldozed the cottages they were renting, the industrial pollution all around the town went beyond toxic all the way to deadly, generating a cancer cluster, and the government put a highway through, tearing the community in two.

Raines’ previous book was the environmental cri du coeur “Saving America’s Amazon,” and his expertise and outrage infuse this section of the story. In the interests of commerce and "development" environmental regulations were ignored by the worst environmental protection agency in the country.

Raines has researched the story of the “Clotilda” through all the written materials on the subject, through his own exploration of the Mobile Delta and by an extensive trip to Benin, the territory which was Dahomey and surrounding territory.

There he learned, to his and the reader's surprise, that there are discussions ongoing between the descendants of the Dahomans and the descendants of the peoples they captured, killed and sold into slavery. Not too surprisingly, there are still some bad feelings. There is talk of reparations, reconciliation, apology and forgiveness.

Here in Alabama, Raines argues, the “Clotilda” should be raised, and become the centerpiece of an Africatown museum which would be educational and attract tourism to rival the Legacy Museum in Montgomery and revitalize that much-abused community.

Don Noble’s newest book is Alabama Noir, a collection of original stories by Winston Groom, Ace Atkins, Carolyn Haines, Brad Watson, and eleven other Alabama authors.

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

The Last Slave Ship : Book summary and reviews of The Last Slave Ship by Ben Raines

Summary | Reviews | More Information | More Books

The Last Slave Ship

The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning

by Ben Raines

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' rating:

Published Jan 2022 304 pages Genre: History, Current Affairs and Religion Publication Information

Rate this book

About this book

Book summary.

The incredible true story of the last ship to carry enslaved people to America, the remarkable town its survivors founded after emancipation, and the complicated legacy their descendants carry with them to this day - by the journalist who discovered the ship's remains.

Fifty years after the Atlantic slave trade was outlawed, the Clotilda became the last ship in history to bring enslaved Africans to the United States. The ship was scuttled and burned on arrival to hide evidence of the crime, allowing the wealthy perpetrators to escape prosecution. Despite numerous efforts to find the sunken wreck, Clotilda remained hidden for the next 160 years. But in 2019, journalist Ben Raines made international news when he successfully concluded his obsessive quest through the swamps of Alabama to uncover one of our nation's most important historical artifacts. Traveling from Alabama to the ancient African kingdom of Dahomey in modern-day Benin, Raines recounts the ship's perilous journey, the story of its rediscovery, and its complex legacy. Against all odds, Africatown, the Alabama community founded by the captives of the Clotilda , prospered in the Jim Crow South. Zora Neale Hurston visited in 1927 to interview Cudjo Lewis, telling the story of his enslavement in the New York Times bestseller Barracoon . And yet the haunting memory of bondage has been passed on through generations. Clotilda is a ghost haunting three communities—the descendants of those transported into slavery, the descendants of their fellow Africans who sold them, and the descendants of their American enslavers. This connection binds these groups together to this day. At the turn of the century, descendants of the captain who financed the Clotilda 's journey lived nearby—where, as significant players in the local real estate market, they disenfranchised and impoverished residents of Africatown. From these parallel stories emerges a profound depiction of America as it struggles to grapple with the traumatic past of slavery and the ways in which racial oppression continue to this day. And yet, at its heart, The Last Slave Ship remains optimistic – an epic tale of one community's triumphs over great adversity and a celebration of the power of human curiosity to uncover the truth about our past and heal its wounds.

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews.

"Journalist Raines unearths in this riveting chronicle the story of the last slave ship to arrive in the U.S...an evocative and informative tale of exploitation, deceit, and resilience." - Publishers Weekly (starred review) "Raines weaves an impressively multilayered story...[he] should be commended for his dogged journalistic work locating the sunken ship, which the owners tried to destroy, as well as the descendants of those original enslaved Africans. A highly readable, elucidating narrative that investigates all the layers of a traumatic history." - Kirkus Reviews (starred review) "Raines effectively blends historical research and journalism into a gripping transatlantic tale of trauma, hope, and reconciliation. An absolutely essential book." - Library Journal (starred review) "Ben Raines' passionate detective work led him to discover the most famous slave shipwreck… Raines has written a crucial chapter in this unique story of loss and exploitation, but also of unsurmountable strength and hopefulness. An inspiring and captivating book." - Sylviane A. Diouf, PhD, author of Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America " The Last Slave Ship is all at once the true story of a terrible crime and its survivors, a riveting account of discovering the evidence its perpetrators hoped would never be found, and a moving attempt to grapple with its legacy. We may never ultimately be able to reckon adequately with slavery, but Ben Raines reminds us that the task's immensity is no excuse for neglecting it. This is a powerful and important book." - Joshua Rothman, the Dept. of History professor at University of Alabama "Raines' adroit descriptions of the people and events triggered by the voyage of Clotilda are not only riveting, but speak to the true spirits of all involved." - Darron Patterson, President of The Clotilda Descendants Association

Click here and be the first to review this book!

Author Information

Ben Raines is an award-winning environmental journalist, filmmaker, and charter captain. He lives with his wife in Fairhope, Alabama.

More Author Information

More Recommendations

Readers also browsed . . ..

- Better Living Through Birding by Christian Cooper

- The Country of the Blind by Andrew Leland

- Those Pink Mountain Nights by Jen Ferguson

- Impossible Escape by Steve Sheinkin

- Fatherland by Burkhard Bilger

- Absolution by Alice McDermott

- The Making of Yolanda la Bruja by Lorraine Avila

- A Fever in the Heartland by Timothy Egan

- Red Memory by Tania Branigan

- Flee North by Scott Shane

more history, current affairs and religion...

Support BookBrowse

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The Mystery Writer by Sulari Gentill

There's nothing easier to dismiss than a conspiracy theory—until it turns out to be true.

Help Wanted by Adelle Waldman

From the best-selling author of The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. comes a funny, eye-opening tale of work in contemporary America.

The Divorcees by Rowan Beaird

A "delicious" debut novel set at a 1950s Reno divorce ranch about the complex friendships between women who dare to imagine a different future.

Book Club Giveaway!

Douglas Westerbeke's much anticipated debut

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue meets Life of Pi in this dazzlingly epic.

Solve this clue:

N N I Good N

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

The Washington Informer

Black News, Commentary and Culture | The Washington Informer

BOOK REVIEW: ‘The Last Slave Ship’ by Ben Raines and ‘The Black Joke’ by A.E. Rooks

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Sign up to stay connected

Get the top stories of the day around the DMV.

- WIN Daily Start your weekdays right with the most recent stories from the Washington Informer website. Once a day Monday-Friday.

- JPMorgan Chase Money Talks Presented with JPMorgan Chase, this financial education series is dedicated to bridging the racial wealth gap. Let's embark on a journey of healthy financial conversations together. Bi-Monthly.

- Our House D.C. Dive deep into our monthly exploration of the challenges and rewards of Black homeownership. Monthly.

- Deals & Offers Exclusive perks, updates, and events from The Washington Informer partners just for you.

“The Last Slave Ship” by Ben Raines c.2022, Simon & Schuster $27.99 307 pages

===============

“The Black Joke” by A.E. Rooks c.2022, Scribner $29 400 pages

You can only imagine.

There was fear, of course, but also pain and a feeling of suffocation. Surely, there was a sense of embarrassment when clothes were lost and bodily smells were unavoidable. Outrage, too, that was surely present, but you can only imagine. If you’re compelled to know, read these two great new books about the ships of the Middle Passage.

Not long ago, the news was buzzing with a very unexpected discovery: the remains of the Clotilda, a 160-year-old ship, were discovered in Alabama waters, half-burned but in good enough shape for its discoverers to know what it was and the importance it held …

“The Last Slave Ship” by Ben Raines begins the tale of those ruins in 1860, when more than five decades had passed since the importation of slaves from Africa had become law. Still, Timothy Meaher was a betting man. Meaher wagered that he could somehow send the Clotilda across the ocean, and back with human cargo, without getting caught. History, of course, didn’t allow that.

But this isn’t just a tale of a white man and a ship. It’s also a story of warfare, the capture of 110 people, and their sale in Africa by a king who showed no mercy and who almost re-captured the slaves-to-be to resell them. It’s a story of peril and politics, and it extends to the descendants of the captain and his cargo today.

“The Last Slave Ship” is an action-packed, whip-smart true account that’s filled with science, history, and compassion. Readers will devour it.

A nice companion to the Raines book is “The Black Joke” by A.E. Rooks .

In the time between Napoleon’s fall in France and the very height of Queen Victoria’s reign in England, the Black Joke sailed the Atlantic on behalf of England to end the slave trade — not just in Great Britain, but on both sides of the ocean.

Until its capture by the Royal Navy in 1827, the Black Joke was a notoriously fast slave ship that shuttled humans from Africa to parts elsewhere. The Brits knew exactly what to do with it, once they had possession of the ship: they recycled it, making the Black Joke into an important part of their anti-slavery fleet and a speedy way to capture slaving vessels and free the people aboard them.

Like “The Last Slave Ship,” “The Black Joke” is full of action and heroism, but in a different way: the former includes the recovery of an important bit of U.S. history, while the latter is a wider story, both in scope and geography. Readers will be happy (and very well-informed) to read one, then the other, in quick succession.

Once you’ve done that, you may want more information so check with your favorite bookseller or librarian. They have many more stories of slave ships at their fingertips, including firsthand accounts from many points of view. All you have to do is ask and you’ll find more similar books than you can imagine.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

America's Black Holocaust Museum

Bringing Our History to Light

The Last Slave Ship review: the Clotilda, Africatown and a lasting American injustice

More breaking news.

Oprah, Ozempic and Us

First of 6 Mississippi ex-officers sentenced to 20 years for torturing 2 Black men: ‘I’m so sorry … I hate myself for it’

First charter flight with US citizens fleeing Haiti lands in Miami

As AI tools get smarter, they’re growing more covertly racist, experts find

‘American Society of Magical Negroes’ cast and director say not to judge the film by its trailer

Victims of the Flint Water Crisis Are Still Waiting to Get Paid

6 Massachusetts teens charged in racial bullying incident with mock slave auction on Snapchat

Elon Musk Keeps Spreading a Very Specific Kind of Racism

Explore Our Galleries

African Peoples Before Captivity

Kidnapped: The Middle Passage

Nearly Three Centuries Of Enslavement

Reconstruction: A Brief Glimpse of Freedom

One Hundred Years of Jim Crow

I Am Somebody! The Struggle for Justice

NOW: Free At Last?

Memorial to the Victims of Lynching

The Freedom-Lovers’ Roll Call Wall

Special Exhibits

Portraiture of Resistance

Breaking news.

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Michael Henry Adams , The Guardian

Ben Raines offers a welcome and affecting history lesson about a dark moment in US history and how its legacy lingered

Raines begins in 1860, 50 years after the Atlantic slave trade was outlawed. That was when a sleek, custom-built schooner, the Clotilda, returned to Mobile, Alabama , from Dahomey, which nowadays is known as Benin. Chartered by a planter and riverboat captain, Timothy Meaher, the Clotilda carried a valuable cargo: 110 young black captives. Meaher had made a thousand-dollar bet with passengers at the captain’s table. He could pull off the caper of bringing a boatload of enslaved Africans to Mobile – a capital offense – without consequence. Spoiler alert! He did.

For many, one suspects, the most enlightening part of this sad saga occurs at the start. Some who have heard of the direct involvement of Africans in the Atlantic slave trade have suspected apologists’ propaganda. True, as with today’s drug trade, without a lucrative market among Arabs, Europeans and Americans, slavery would have collapsed much sooner. But there is no exaggerating the extent to which the rulers of Dahomey were involved in capturing fellow Africans for both enslavement and sacrifice. Its victims are estimated in the hundreds of thousands.

Meaher and his accomplices decided it was prudent to destroy the evidence. In Mobile, William Foster, the captain who carried out the venture, set the Clotilda ablaze and scuttled her. Soon to resign from US law enforcement to join the Confederacy, the gang’s prosecutors probably knew where the vessel lay. But with plausible deniability, they maintained there was no evidence criminality had occurred.

Five years later, at civil war’s close, the Africans hit on a stratagem to restore their dignity. They determined to acquire land and establish a realm of their own. They called it Africatown. Predictably, their leader was rebuffed by their captor.

Read the full article here.

Learn what life was like on a slave ship here .

More Breaking News here .

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech . Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here .

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

- Sign up and get a free ebook!

- Don't miss our $0.99 ebook deals!

The Last Slave Ship

The true story of how clotilda was found, her descendants, and an extraordinary reckoning.

- Unabridged Audio Download

Trade Paperback

LIST PRICE $18.99

Buy from Other Retailers

- Amazon logo

- Bookshop logo

Table of Contents

- Rave and Reviews

About The Book

About the author.

Ben Raines is an award-winning environmental journalist, filmmaker, and charter captain. He lives with his wife in Fairhope, Alabama.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (January 24, 2023)

- Length: 304 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982136154

Browse Related Books

- History > Africa > West

- Social Science > Ethnic Studies > American > African American Studies

- History > United States > State & Local > South (AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV)

Raves and Reviews

"The fast-paced narrative begins with the voyage and follows the Clotilda’s survivors beyond the Civil War....Raines vividly conjures the watery landscape into which the Africans stepped... Knowledge of these waterways also led Raines to locate the Clotilda in a place previous searchers had ignored." — The New York Times (Editors' Choice) "In our uncertain times, The Last Slave Ship .. is a welcome and affecting history lesson... Enlightening." — The Guardian " A multidimensional exploration of the Clotilda, its bad actors and the descendants of the survivors... an important, weighty, timely read." — The Atlanta Journal-Constitution "Ben Raines made headlines in 2019 when he discovered the remains of the Clotilda, the last ship to bring enslaved people to America. His gripping, affecting book chronicles his search for the vessel in the swamps of Alabama and tells the stories of its captives and their descendants." — The Christian Science Monitor (Best Books of February ) " The Last Slave Ship is an action-packed, whip-smart true account that’s filled with science, history, and compassion. Readers will devour it." — The Washington Informer "Ben Raines’ passionate detective work led him to discover the most famous slave shipwreck… Raines has written a crucial chapter in this unique story of loss and exploitation, but also of unsurmountable strength and hopefulness. An inspiring and captivating book.” — Sylviane A. Diouf, PhD, author of Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America " The Last Slave Ship is all at once the true story of a terrible crime and its survivors, a riveting account of discovering the evidence its perpetrators hoped would never be found, and a moving attempt to grapple with its legacy. We may never ultimately be able to reckon adequately with slavery, but Ben Raines reminds us that the task’s immensity is no excuse for neglecting it. This is a powerful and important book." — Joshua Rothman, the Dept. of History professor at University of Alabama "Raines’ adroit descriptions of the people and events triggered by the voyage of Clotilda are not only riveting, but speak to the true spirits of all involved." — Darron Patterson, President of The Clotilda Descendants Association "An evocative and informative tale of exploitation, deceit, and resilience.” — Publishers Weekly (starred review) “A highly readable, elucidating narrative that investigates all the layers of a traumatic history. — Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

Resources and Downloads

High resolution images.

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Last Slave Ship Trade Paperback 9781982136154

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today!

Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

More books from this author: Ben Raines

You may also like: Thriller and Mystery Staff Picks

More to Explore

Limited Time eBook Deals

Check out this month's discounted reads.

Our Summer Reading Recommendations

Red-hot romances, poolside fiction, and blockbuster picks, oh my! Start reading the hottest books of the summer.

This Month's New Releases

From heart-pounding thrillers to poignant memoirs and everything in between, check out what's new this month.

Tell us what you like and we'll recommend books you'll love.

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

The Last Slave Ship: The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning

Embed our reviews widget for this book

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

March 20, 2024

- Read Hammer & Hope’s special issue on Palestine

- The widely unknown story of Julia Chinn

- In praise of slow writers

Books | “The Survivors of the Clotilda” tells of the…

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Food & Drink

- TV Listings

Things To Do

Books | “the survivors of the clotilda” tells of the last slave ship to america | book review, the book is an extraordinary story of the captives, who faced brutal oppression and discrimination.

Kossula was just 19 years old when rival African warriors swept through his town in what is now Nigeria, killing and capturing him and others. The captives walked for days, then were penned up for weeks before being loaded onto the Clotilda for a 45-day journey across the water to the United States.

Terrified, the prisoners of that 1860 voyage were crowded onto “shelves, their clothes ripped from them, and they lay for days in their own filth, crying for water and food.” Once they reached their destination, they were chained and marched through swamps and woods until they were sold into slavery.

After a lifetime that included brutal slavery and years of poverty and starvation, Kossula, still remembered the terrors of his capture and the details of his homeland shortly before his death in 1935, at the age of 94. So did other survivors of the Clotilda. Even in their last days, they wanted to return to Africa.

The last Clotilda survivor was Matilda, who was abducted as a 2-year-old. She died in 1940 at age 81 or 82.

Although America had long outlawed slave ships, stealthy slavers still managed to land their cargo of Africans in the antebellum South. Over the years, some 36,000 slave-ship voyages were made across the Atlantic to the Americas. The 110 captives on the Clotilda were a small number of the estimated 12.5 million who made the voyages to the Americas starting in the early 1700s. The Clotilda was the last slave ship to land in the United States, in 1860.

In a heavily researched book, Hannah Durkin tells the story of the Clotilda’s voyage and its aftermath. “The Survivors of the Clothilda” follows the men and women from their capture in Africa to their lives as slaves in the U.S. South and finally to their years as free people. The book is an extraordinary story of the captives, who faced brutal oppression and discrimination. Even as free men and women, some still spent their lives working on the plantations of their enslavers. Most spent their post-slavery years in poverty and near starvation.

The Clotilda’s voyage came about as a bet between wealthy slave-owners that they could sneak a shipload of Africans into the U.S. without government knowledge. The Africans, who had no idea their miserable journey would get even worse once the ship landed, were acquired by plantation owners looking for strong men to work the fields and fertile women to provide additional slaves.

Dinah, 13, who family legend says was sold for only a dime because she was so small, was sent to the cotton fields to work. She was forced to live in a cabin with four young, healthy men who raped her repeatedly, until, after giving birth, she was sent to cook and clean for an enslaver’s wife. “The slave women were bred like they breed hogs and cows,” her great-granddaughter said in a 2002 interview.

Dinah never got over her rage at her kidnapping and captivity, and in later years, forced her great-grandchildren to listen daily to the story of her life so that they would never forget.

At age 46, Dinah moved to Gee’s Bend, Ala., near where she had been enslaved, and may have become one of the community’s famed quilters. The quilters used worn-out clothes in their quilts, in part to memorialize loved ones. “I can point to my grandmother’s dress and tell my kids what she did in that dress,” said a later Gee’s Bend quilter. “We didn’t have cameras growing up; we had quilts.” Discovered 50 years ago by textiles connoisseurs, Gee’s Bend unique quilts made from used work clothes are rich examples of Black folk art.

As the years passed, the story of the Clotilda and its cargo of Africans became sanitized. Journalists discovered survivors such as Kossula and wrote about them in a patronizing way. They were turned into Uncle Remus-like characters and the brutality of their lives softened.

With her research and her sympathetic writing, Durkin has rescued the survivors of the Clotilda from such ignominy. “The Survivors of the Clotilda is a gripping account of one of the most despicable events in U.S. history.

The Survivors of the Clotilda

Author: By Hannah Durkin

Publisher: Amistad

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, In The Know, to get entertainment news sent straight to your inbox.

- Report an Error

- Submit a News Tip

More in Books

Movies | It’s never too late to fall in love with Star Wars

Books | The Book Club: “Small Mercies” and more short reviews from readers

Books | Tik Tok star librarian resigns due to cyberbullying

Books | “Birding Under the Influence” and more short book reviews from readers

Book Review: The Last Slave Ships: New York and the End of the Middle Passage

by David T. Dixon

Posted on June 4, 2021

By John Harris Yale University Press, 2020, $30.00 hardcover Reviewed by David T. Dixon

A large crowd gathered in the yard of a New York City jail nicknamed “The Tombs” to witness the execution of Nathaniel Gordon on February 21, 1862. Gordon had been convicted of violating the Act of 1820 that forbid slave trading and was sentenced to death. President Abraham Lincoln rebuffed petitions for clemency from more than 11,000 New Yorkers. With two state governors, various federal and local officials, and eighty-four U.S. Marines looking on, Gordon ascended the steps to the scaffold while cursing district attorney Delafield Smith. As the body of the condemned man dangled in silence from the noose end of a rope, Gordon’s widow may have wondered why her former husband had been treated with such cruelty. After all, the illegal slave trade had been booming while hiding in plain sight in America for decades, yet Gordon was the first and only slave trader ever executed under American law.

John Harris, an assistant professor of history at Erskine College in South Carolina and a native of Northern Ireland, expanded his PhD dissertation to create The Last Slave Ships: New York and the End of the Middle Passage . Harris explains how and why illicit human trafficking thrived in defiance of international efforts to suppress it and U.S. laws designed to end it. Harris employed deep research in primary sources from archives in Brazil, Portugal, Great Britain, Cuba, and America to construct a convincing and original argument in clear and concise prose.

Harris begins by summarizing efforts led by the British to ban the transatlantic slave trade during the first half of the nineteenth century. Illegal importation of enslaved African people directly to U.S. shores dried up in the 1820s, but Americans remained heavily invested in the illegal trade to Brazil and Cuba. American vessels delivered more than a half million captives to plantations in those countries, benefitting from diplomatic arrangements with Great Britain that made search and seizure of U.S. flagged vessels difficult. Once Brazil outlawed the Atlantic slave trade in 1850, Portuguese merchants relocated to Lower Manhattan in New York City, where they set up shop, purchasing ships under the names of American citizens, devising elaborate money laundering schemes, bribing local customs officials, and managing a high-risk triangle trade of African slaves, Cuban sugar, and American ships that generated a 91 percent return on investment.

Harris hits his narrative stride in chapter three with vivid and disturbing accounts of life aboard American slave ships, using detailed testimony taken during the trial of the owners and captain of the slaver Julia Moulton . She transported 664 captive African people, as many as half of whom were children who took up less place and thus yielded increased profits. Four hundred enslaved people suffered below deck, “stacked like cordwood” according to one crew member. Five and a half square feet was allocated to each male adult amid three and a half feet of headspace. Enslaved people on another ship, the Clotilda , were kept below deck for thirteen consecutive days and nights with hatches nailed shut to avoid detection by the British Navy’s West African Squad.

Suppression efforts on the part of the American government were lax and ineffective, so British prime minister Lord Palmerston hired Cuban American Emilio Sanchez and others to spy on Americans in New York City and report on slave trading. By the middle of the 19 th century, Great Britain was spending 1.3% of its annual budget on efforts to suppress the slave trade. The British counsel in New York leaked some of Sanchez’s intelligence to U.S. authorities, who did nothing with the information. Successive Democratic presidential administrations obfuscated rather than take action against the illegal trade. Many Southern politicians blamed Spain for the illicit commerce. Their proposed remedy: annex Cuba as a future slave state. Legislation to cripple the Atlantic slave trade in the U.S. Senate, led by William Seward, foundered in 1859 as the sectional crisis neared its tipping point.

The incoming Lincoln administration provided both the will and financing for the U.S. government to finally get serious about ending the transatlantic slave trade, securing funds for former harbormaster turned New York federal marshal Robert Murray to step up enforcement efforts. Such work resulted in the arrest, trial and conviction of Nathaniel Gordon, among others. After Gordon’s execution, Secretary of State William Seward negotiated a treaty with the British that relaxed right of search rules for British cruisers who intercepted slavers flying the U.S. colors. This effort was important in light of the recent Trent Affair that had damaged U.S./British relations and fed Lincoln’s strong desire to deter Great Britain from recognizing the Confederate government. Seward’s diplomacy effectively ended American involvement in the international slave trade. Portuguese merchants who had dominated the illicit activity were gone from Manhattan with a year and the American slave ship Marquita , flying Spanish colors despite having sailed from New York, was captured by the British of the coast near the Congo River in 1863.

Harris’s fine book synthesizes the latest scholarship on the transatlantic slave trade and adds critical insight into how global capital markets, geopolitics, transnational criminal syndicates, and international espionage rings operated and exerted influence on U.S. events throughout the Civil War period in America.

David T. Dixon is the author of Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2020).

Share this:

10 responses to book review: the last slave ships: new york and the end of the middle passage.

Interesting and relatively fair article. The comments on Cuba are mildly off; in the earlier 1850s, there was talk, both North and South, about annexing Cuba to expand the cotton trade with Britain, etc., but it died out as the possibility of war with Spain arose (google: Knights of the Golden Circle). By the time of the Civil War, big plans for international expansion of cotton had dwindled to a small spot in Mexico and possibly one small Central American country, with little enthusiasm from any potential recipients. The Northwest Territories were never seen as potential for cotton; the admission of Texas in 1845 did add territory for cotton. Since cotton was the agricultural export gold rush of its day (57% of all exports in 1857), it was a key economic issue for all. The Northern slave trade was not essential to the South, and was in fact a burden, as seen in the Constitution when the South compromised grudgingly to allow it only until 1809, with a $10/head tax for the Federal Government for as long as it persisted.

The execution is an interesting new revelation; when I think of NYC during the Civil War, I picture the draft riots of 1863.

Here here! That and Zouaves

The New York newspapers called it “the thunder clap.” In it’s wake, the slave traders tucked tail and fled the U.S.

Great review. I want to read the book.

There was slavery in Cuba? The Erie (Nathaniel Gordon’s ship) was one of many known to have been engaged in the illicit trans-Atlantic slave trade during the antebellum. Hermosa in 1840; Cora and Clotilda were two other ships operating in 1859/ 1860; Nightingale in 1861; and the Esmeralda was captured in November 1864. The trade would not have been conducted if it were not profitable; and a “merchant” ship sets out on a voyage only if it has someplace to discharge its cargo. Of course, slave ships were not all bound for the USA; legally, NONE of them were. In 1860 there were many nations/ locations in the Western hemisphere involved in the slave trade, as receivers: but none “legally” because the trans-Atlantic slave trade was outlawed. It appears that “they arrived here because of a storm” became common excuse for the arrival of slave ships: sometimes the captured persons were returned to Africa; other times, Slave Interests quickly mobilized and spirited the people away, beyond the reach of law enforcement. (The “coasting trade” was not supposed to reach to Cuba, but sometimes storms came up…) Countries known to have “assisted” with perpetuation of the slave trade from 1820 -1861 include Cuba, Peru, Texas, West Indies (various islands), Brazil… Nicaragua had its laws against slavery repealed during William Walker’s rule of 1856 – 1857. And filibusters from the United States appear to have as one of their goals “expansion of slave territory.” Then, of course, there was “railroad expansion to the Pacific.” Interests North and South competed to build that first Eldorado of a rail line promising boundless profits, with southern interests (remember the Gadsden Purchase) believing it would lead to continued viability of the slavery system: expansion of slave holdings; access to more cotton markets (and tobacco markets) from the West Coast. Reference: De Bow’s Commercial Review: a monthly magazine reflecting Southern agricultural and business interests, firs published at New Orleans in 1846 by J.D.B. De Bow https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008923645 [To fully understand how the U.S. Civil War came about, it is important to recognize the direction that leaders of the American South were attempting to go. This book by John Harris appears to broach some important questions…]

Good review. The tie-in of New York finance to slavery as well as the reliance of the sugar refiners in Brooklyn and New York form the other two legs of the area’s slave stool.

- Pingback: Around the Web July 2021: Best of Civil War & Reconstruction Blogs and Social Media - The Reconstruction Era

This ties in nicely with a book I’m currently reading, “Dreams of Africa in Alabama” by Sylviane A. Diouf. It’s about the Clotilda, the last slave ship to land Africans on American soil in the summer of 1860. It also talks about the boom of illegal slave trade and mentions Gordon in one of the chapters. The tragic part is that even if a slave ship was discovered before landing, the “cargo” would not be returned to their where they embarked, but sent to Liberia or Sierra Leon. if they were already in America, no effort was made to send them home. It talks a great deal about the illegal slave trade in the south and how so many people got away with it up to the 1840s and 50s. It’d be a nice companion to Harris’ book.

Thanks to David Dixon for a great review of my book. Much appreciated!

Please leave a comment and join the discussion! Cancel reply

ECW Podcast

Publications.

Contributors

Your subscription makes our work possible.

We want to bridge divides to reach everyone.

Get stories that empower and uplift daily.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads .

Select free newsletters:

A selection of the most viewed stories this week on the Monitor's website.

Every Saturday

Hear about special editorial projects, new product information, and upcoming events.

Select stories from the Monitor that empower and uplift.

Every Weekday

An update on major political events, candidates, and parties twice a week.

Twice a Week

Stay informed about the latest scientific discoveries & breakthroughs.

Every Tuesday

A weekly digest of Monitor views and insightful commentary on major events.

Every Thursday

Latest book reviews, author interviews, and reading trends.

Every Friday

A weekly update on music, movies, cultural trends, and education solutions.

The three most recent Christian Science articles with a spiritual perspective.

Every Monday

From Africa to Alabama: Stories of survivors of the last slave ship

Captives on the ship Clotilda survived the middle passage and enslavement. After Emancipation, they carved out lives and towns in Alabama. But they struggled to escape poverty.

- By Barbara Spindel Contributor

March 7, 2024

The horrors of the trans-Atlantic slave trade are often expressed in numerical terms whose enormity can be difficult to grasp. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, 12.5 million people in Africa were forced onto slave ships bound for the Americas; 10.7 million survived the crossing and entered a life of bondage. As a result of the brutal conditions that captives were subjected to on the ships, 1.8 million died along the way.

The story of the Clotilda, the last slave ship to arrive on U.S. shores, gives human dimension to those staggering statistics. As British historian Hannah Durkin observes in her absorbing and affecting book “The Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave Trade,” the circumstances of those on the ship were uniquely well documented. “Archival material relating to the Clotilda and its survivors collectively represents by far the most detailed record of a single slave ship voyage and its legacies,” she writes. “Moreover, it is the only Middle Passage story that can be told comprehensively from the perspective of those enslaved.”

The wealth of information stems from the voyage’s timing. The Clotilda docked in Mobile, Alabama, in July 1860, five decades after the abolition of the American slave trade. (Slavery itself was not abolished until 1865.) The illegal endeavor grew out of a $1,000 bet made by planter Timothy Meaher, who boasted that he could elude the ban and successfully import a ship of human cargo. He won the wager, and he was never punished for his crime.

But because the Civil War erupted months later, the Clotilda survivors – who were all abducted from the same town in present-day Nigeria by raiders from the kingdom of Dahomey in present-day Benin – were emancipated within five years. They attracted the attention of researchers and writers who were interested in interviewing formerly enslaved people who remembered their lives in Africa and could describe the miseries of the middle passage.

The ship itself has drawn attention. Its sunken remains, which were concealed by Meaher and his co-conspirators, were finally uncovered in 2018; Ben Raines, the journalist and charter boat captain who discovered the wreckage, published a gripping book, “The Last Slave Ship,” in 2022. That year also saw the release of “Descendant,” a feature-length documentary about the Clotilda. Both the book and the film address efforts by the progeny of the survivors to wrestle with their traumatic family histories.

For her part, Durkin remains focused on the Clotilda passengers themselves. She begins with the kidnapping and sale of 110 captives, primarily teenagers and children, to the ship’s captain, William Foster. (He chose young people who would presumably be able to labor and bear children for years to come.) After chronicling their perilous and frightening 45-day voyage, the author goes on to describe the sale of the 103 survivors of the journey to various enslavers in Alabama, their five years of bondage, and their hardscrabble lives following emancipation.

Some of the shipmates attempted to raise money to return to Africa after the war; when their efforts failed, they bought land from Meaher, their former enslaver. They created a community known as Africa Town (now called Africatown), which, in Durkin’s words, was “a highly ordered society that drew on the social structures and teachings they learned as children.”

One of Africa Town’s best-known residents was Cudjo Lewis, also known as Kossula, whose recollections formed the basis of Zora Neale Hurston’s nonfiction book “Barracoon.” When he died in 1935 at the age of 94, he was remembered as the last living person brought to America on a slave ship. But Durkin’s research reveals that a woman named Redoshi outlived Kossula by more than a year.

It’s a fitting discovery for a book that sheds new light on the experiences of female survivors of the slave trade. In interviews, Redoshi recalled the hard labor and frequent beatings during her years of enslavement. Like many of the other Clotilda survivors – and like African Americans in general in the post-Reconstruction South – she struggled in the face of economic exploitation, racial violence, and the loss of political rights. She lived on her enslaver’s property because she had nowhere else to go. “Redoshi was never able to escape her poverty and only nominally did she escape slavery,” Durkin writes.

The author captures the complexities of the survivors’ experiences. “Their lives document the manifold ways, big and small, that a group of enslaved children and young adults resisted their imprisonment, impoverishment and geographical isolation and asserted their West African identities in the United States both during and after slavery,” she notes. Still, even while stressing their extraordinary endurance, Durkin never loses sight of what was lost. Decades after emancipation, Clotilda survivor Osia Keeby was interviewed by Booker T. Washington, who asked the older man if he hoped to return to his homeland one day. Keeby replied, “I goes back to Africa every night, in my dreams.”

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Unlimited digital access $11/month.

Digital subscription includes:

- Unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

- CSMonitor.com archive.

- The Monitor Daily email.

- No advertising.

- Cancel anytime.

Related stories

Wild seas and alien wonder: get carried away with january’s best books, 10 best books of april: the courage to look under the surface, how barbados became a leader in caribbean calls for reparations, share this article.

Link copied.

Give us your feedback

We want to hear, did we miss an angle we should have covered? Should we come back to this topic? Or just give us a rating for this story. We want to hear from you.

Dear Reader,

About a year ago, I happened upon this statement about the Monitor in the Harvard Business Review – under the charming heading of “do things that don’t interest you”:

“Many things that end up” being meaningful, writes social scientist Joseph Grenny, “have come from conference workshops, articles, or online videos that began as a chore and ended with an insight. My work in Kenya, for example, was heavily influenced by a Christian Science Monitor article I had forced myself to read 10 years earlier. Sometimes, we call things ‘boring’ simply because they lie outside the box we are currently in.”

If you were to come up with a punchline to a joke about the Monitor, that would probably be it. We’re seen as being global, fair, insightful, and perhaps a bit too earnest. We’re the bran muffin of journalism.

But you know what? We change lives. And I’m going to argue that we change lives precisely because we force open that too-small box that most human beings think they live in.

The Monitor is a peculiar little publication that’s hard for the world to figure out. We’re run by a church, but we’re not only for church members and we’re not about converting people. We’re known as being fair even as the world becomes as polarized as at any time since the newspaper’s founding in 1908.

We have a mission beyond circulation, we want to bridge divides. We’re about kicking down the door of thought everywhere and saying, “You are bigger and more capable than you realize. And we can prove it.”

If you’re looking for bran muffin journalism, you can subscribe to the Monitor for $15. You’ll get the Monitor Weekly magazine, the Monitor Daily email, and unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

Subscribe to insightful journalism

Subscription expired

Your subscription to The Christian Science Monitor has expired. You can renew your subscription or continue to use the site without a subscription.

Return to the free version of the site

If you have questions about your account, please contact customer service or call us at 1-617-450-2300 .

This message will appear once per week unless you renew or log out.

Session expired

Your session to The Christian Science Monitor has expired. We logged you out.

No subscription

You don’t have a Christian Science Monitor subscription yet.

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $16.69 $16.69 FREE delivery: Tuesday, March 26 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $10.54

Other sellers on amazon.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Africatown: America's Last Slave Ship and the Community It Created Hardcover – February 21, 2023

Purchase options and add-ons.