31 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Story Analysis

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “the cabuliwallah”.

"The Cabuliwallah" is a short story by Rabindranath Tagore that utilizes realism to explore the themes of The Transcendental Quality of Human Connection , A Father’s Love , and The Passage of Time . The plot centralizes the unexpected friendship that blossoms between the narrator’s young daughter, Mini , and a Cabuliwallah (meaning a man from Kabul) named Rahmun. The story was first published in 1892 and is narrated from the first-person perspective of a Bengali writer and father, who offers glimpses into the unlikely cross-cultural bond his daughter forms with the Afghani peddler.

Tagore's appreciation for the poets of medieval Bengal and Bengali folk literature reflects in his storytelling, which often features characters from rural Bengal and explores the depths of human emotions. He draws from Indian philosophies and aesthetics to explore universal themes of love, nature, and the human spirit. Moreover, Tagore’s fruitful exchange with modern European literary tradition, especially the English Romantic poets, adds a touch of Romanticism and introspection to his works. These influences are apparent in "The Cabuliwallah," which explores human connection, love, and longing for loved ones.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,400+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,900+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

This guide refers to the version of the text that is freely available on Project Gutenberg.

The story opens with an introduction to Mini, a spirited five-year-old girl. The unnamed narrator, who is Mini’s father , describes her as a talkative child who “all her life […] hasn’t wasted a minute in silence” (1). Mini's constant chatter vexes her mother, but her father appreciates her inquisitive nature and enjoys engaging in conversations with her.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

Mini sits in her father’s study as he works on his novel. She spots a Cabuliwallah from their window and calls out to him. The Cabuliwallah, named Rahmun, is a tall and bearded man. He wears traditional Afghan clothing, including a turban, and carries a bag and boxes of grapes. Rahmun is a peddler who sells various goods, including dry fruits and shawls, and often visits Calcutta to sell his merchandise.

Mini is initially reluctant to meet Rahmun. She is frightened by Rahmun’s strangeness; she imagines that he has stuffed children in his bag. Rahmun tries to approach her, but she fearfully hides behind her father. After the first encounter, however, Mini lets her guard down and her fear subsides. She soon strikes up a friendship with Rahmun, who offers her small treats of raisins and nuts. As he continues his visits to Mini’s home, she grows fond of him and the two bond over shared jokes.

Meanwhile, the narrator is captivated by Rahmun's tales of the distant land of Afghanistan. Rahmun’s vagrant life contrasts with the narrator’s own rooted existence in Calcutta. While the narrator dreams of traveling the world, he is hesitant to leave his familiar surroundings. On the other hand, Mini's mother is concerned about Rahmun's presence, primarily due to his foreignness. The narrator tries reassuring his wife, but she persists in harboring doubts against Rahmun.

Despite Mini's mother's unease, Rahmun’s visits continue until one day, the narrator witnesses him being led away in handcuffs. Rahmun explains that he got into a scuffle with a customer who refused to pay for a shawl that he had taken. During the quarrel, it is implied that he stabbed the customer. Mini, oblivious to the gravity of the situation, asks if the Cabuliwallah is being taken to his “father-in-law,” a euphemism Rahmun uses for “jail.” Rahmun is imprisoned for a few years.

Mini gradually forgets about Rahmun, makes new friends, and also grows less attached to her own father. The narrator laments that he has lost the close connection he once shared with Mini.

The plot jumps forward several years, and it is revealed that Mini is about to get married. The morning of her wedding is described as “bright and festive, with wedding-pipes playing since early dawn” (12). The narrator reflects on the radiant sunlight and the pain that he feels at the approaching separation from his daughter.

Immersed in his study, the narrator is startled when Rahmun unexpectedly arrives at his house, having just been released from jail. Rahmun's appearance has changed—he no longer carries a bag, has long hair, or the same vigor that he used to possess. However, Mini's father recognizes him by his smile.

The narrator initially tries to dismiss Rahmun by telling him that they are busy with wedding preparations. However, Rahmun expresses a desire to see Mini, believing that she is still the same little girl who would run to him, calling out "O Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!" (7). When the narrator relents, Rahmun offers grapes, nuts, and raisins as a gift for Mini.

Rahmun then shows the narrator a crumpled piece of paper containing the handprint of his own daughter, Parbati, that he carries with him at all times. This show of a father's enduring love and longing for his child touches the narrator deeply, prompting a change of heart. The narrator calls Mini, who arrives dressed as a bride. The carefree little girl has transformed into an inhibited young woman.

When Mini enters the room, Rahmun presents her with a few almonds, raisins, and grapes wrapped in paper, just like he used to years ago. Now, the innocence of childhood has faded. She blushes and looks away, leaving the Cabuliwallah with a heavy heart.

As Mini departs, Rahmun is hit with a realization that his own daughter must have grown up like Mini. The narrator is touched by the deep love that Rahmun feels for his daughter; he sees himself reflected in the man’s defeated figure. He offers Rahmun money to help him return home. Though this means that the narrator can no longer finance a wedding band or electricity for Mini's wedding ceremony, he believes that this act of kindness brings a more gracious light to the occasion.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Rabindranath Tagore

My Lord The Baby

Rabindranath Tagore

The Home and the World

Featured Collections

View Collection

Indigenous People's Literature

Valentine's Day Reads: The Theme of Love

- Science & Math

- Sociology & Philosophy

- Law & Politics

Rabindranath Tagore’s The Cabuliwallah: Summary & Analysis

- Rabindranath Tagore’s The Cabuliwallah: Summary…

The Cabuliwallah is from Kabul. His real name is Abdur Rahman. He works as a peddler in India. He goes to Kabul once a year to visit his wife and little daughter. In the course of selling goods, once he reaches the house of writer, Rabindranath Tagore. Then his five years daughter, Mini calls him ‘Cabuliwallah! A Cabuliwallah’.

When Cabuliwallah goes to visit Mini she is afraid because he is wearing loose solid clothes and a tall turban. He looks gigantic. When the writer knows that Mini is afraid, he introduces her to him. The Cabuliwallah gives her some nuts and raisins. Mini becomes happy from next day, the Cabuliwallah often visits her and he gives her something to eat.

They crack jokes and laugh and enjoy. They also feel comfortable in the company of each other. The writer likes their friendship. But Mini’s mother doesn’t like it. She thinks that a peddler like Cabuliwallah can be a child lifter. However, Mini and the Cabuliwallah becomes an intimate friend.

The Cabuliwallah sells seasonal goods. Once he sells a Rampuri shawl to a customer on credit. He asks him for the money many times but he doesn’t pay. At last, he denies buying the shawl. The Cabuliwallah becomes very angry and stabs the customer.

Then he is arrested by police and taken to jail. He is jailed for eight years. When he is freed from jail at first he goes to visit Mini surprisingly. It is the wedding day and he isn’t allowed to visit her.

When he shows the finger of a piece of paper to the writer, he permits to meet Mini who is in a wedding dress. The writer knows that the Cabuliwallah has no money to go back to his house so the writer cuts of the wedding expenses like a light and bands and gives one hundred rupees to the Cabuliwallah and sends him to Kabul.

Interpretation:

The writer may be trying to show the attitude of peoples towards foreigners and poor peddlers. Although the Cabuliwallah is very simple and honest, the writer’s wife suspects him as a child lifter also tries to cheat him by not paying his money.

The story also shows the plight of the people due to poverty. If the Cabuliwallah had enough money, he would not come to India leaving his wife and daughter in Kabul. The writer seems to shows that temper ruins anyone.

If Cabuliwallah didn’t stab the customer, he wouldn’t have to go to jail. This story is also full of feelings of humanity. The writer cuts off the wedding expenses and helps the Cabuliwallah.

Critical Thinking:

Although this story is full of the feeling of humanity, some ideas of the writer are skeptical. Does a man leave his children freely with a stranger? Does a peddler give things to other children freely every time? Does the Cabuliwallah stab the customer? Can we find anyone who helps others by cutting off wedding expenses? So, I don’t agree with the writer totally.

Related Posts

- Frank Herbert's Dune: Summary & Analysis

- Gary Paulsen’s Canyons: Summary & Analysis

- Great Gatsby: Chapter Two Analysis & Summary

- Barbara Hambly’s Dragonsbane: Summary & Analysis

- Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet: Summary & Analysis

Author: William Anderson (Schoolworkhelper Editorial Team)

Tutor and Freelance Writer. Science Teacher and Lover of Essays. Article last reviewed: 2022 | St. Rosemary Institution © 2010-2024 | Creative Commons 4.0

27 Comments

Thank you very much 😊

What is the theme/central idea of the story ‘the cabuliwallah’

HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS, FRIENDSHIP & FATHERLY LOVE

good great liked it!

What is the value in the story?

That is good bro or sis thanks for helping

Nice and easy to understand

story of feelings!!!!! also its super sad

Yes!! A man can leave his children with any stranger only when he feels that he is not stranger..Yes,of course,a peddler gives things freely to others children often if not everytime.. I’m totally agree with the writer and he is not skeptical regarding his ideas..

What are some style used by the narrator?

Its is a nice story

I am from the same language as was kabliwalla.Our pashtoon people even now give things free and sometimes with low price to forgners and espically to children.It always happens to me, whenever i go to my villiage. when my small sister asks for any thing at shop esp in town’s shop it is given free.So having skeptical remarks about kabliwallah is not right.The more you go past the more were the people generious and showed more affection to children in particular.

Not bad, but need more detail

Really helpful… and easy to understand😊👌

this is very helpful

very helpful… and its really interesting …

its really good

It is Kabuliwala actually. Please correct. Other than that its alright!!! 🙂

Its really helpful!! .

its good! shows a mixture of humanity, temper, friendship…etc.

Not bad …………….

Like sannia said, this is good for students. Good job.

Perfect way for student!

Ya of course

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post comment

Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories

By rabindranath tagore, rabindranath tagore: short stories summary and analysis of "kabuliwallah".

The story opens with the narrator talking about his precocious five-year-old daughter Mini, who learned how to talk within a year of being born and practically hadn’t stopped talking since. Her mother often tells her to be quiet, but her father prefers to let her talk, so she talks to him often.

One day while the narrator is writing, Mini starts crying out “Kabuliwallah, Kabuliwallah!” The man she’s shouting about is an Afghan in baggy clothes, walking along selling grapes and nuts. Mini fears him, convinced that she has children the size of herself stashed in his bag.

But a few days later, our narrator finds the Kabuliwallah sitting with Mini, paying close attention as she talks and talks. He has given her some grapes and pistachios, so the narrator gives the Kabuliwallah half a rupee. Later, Mini’s mother finds her with the half-rupee and asks where she got it, and is displeased to hear she took money from the man.

Mini and the Kabuliwallah develop a close relationship, spending time together every day joking around and talking. The narrator enjoys talking to the Kabuliwallah too, asking him about his home country of Afghanistan, and all about his travels. But Mini’s mother is alarmed by her daughter’s closeness with the man, worrying that he might try to abduct Mini. The narrator does not agree that there is any danger.

Every year in the middle of the month of Magh, the Kabuliwallah returns home. Before making the trip, he goes around collecting money he is owed. But this year, the Kabuliwallah gets in a scuffle with a man who owes him money and ends up stabbing him. This lands him in jail for the next several years, during which Mini grows up and starts enjoying the company of girls her age. The narrator more or less forgets about the Kabuliwallah.

But on the day of Mini’s wedding, the Kabuliwallah appears at the narrator’s house. Without a bag or his long hair, he is barely recognizable to the narrator, but he eventually welcomes him in. The narrator is uneasy, thinking about how the Kabuliwallah is the only would-be murderer he’s ever known, and tells the visitor to leave. He complies.

But shortly after, the Kabuliwallah returns, bringing a gift of grapes and pistachios for Mini. The narrator doesn’t tell him that it’s her wedding today, but simply repeats that there’s an engagement at their house and he must go. But the Kabuliwallah pulls a small piece of paper out of his coat pocket and shows it to the narrator. It’s a handprint in ash, and he explains that he has a daughter back home in Afghanistan, and that Mini helps him deal with the heartache of being so far from her. The narrator is touched and gets Mini.

Mini and the Kabuliwallah have an awkward exchange during which the man realizes that Mini has grown up, and therefore so has his own daughter. Like with Mini, he’ll have to reacquaint himself with his daughter. The narrator gives the Kabuliwallah money so that he can return home to Afghanistan to see his daughter, meaning that Mini’s wedding will lose some of the theatrics such as electric lights and a brass band. But the wedding will be “lit by a kinder, more gracious light.”

There are two central themes in this story, and Tagore masterfully plays them against each other to build tension in the narrative. The first key theme is otherness , with Kabuliwallah standing as a clear outsider who speaks broken Bengali and dresses in a way that situates him outside of typical Bengali society. The narrator is fascinated by him in part because of the fact that he’s seen parts of the world that are so different from Calcutta, while the narrator’s wife distrusts him precisely because he is a foreigner, and perhaps one who will kidnap her child, which she thinks Afghanis are wont to do.

The other theme is doubling , as the narrator and the Kabuliwallah are construed as mirror characters of one another. They are both shown as storytellers, and each is fascinated enough by Mini to listen to her talk for hours. But most importantly, Tagore reminds us that they’re both fathers, and the narrator seeing the Kabuliwallah as a man who is heartsick over a daughter that he has not seen in years helps the narrator see the man as a human being, not as some would-be murderer.

The genius of the story is the fact that the climax seems to come when Kabuliwallah stabs the debtor, which would confirm the narrator’s wife’s worst fears that this outsider is dangerous. During what seems like the denouement of the story, the Kabuliwallah returns and the narrator, who has clearly spent the intervening years considering the man a would-be murderer, tries to brush this outsider off.

But then the real climax comes. The Kabuliwallah pulls out the piece of paper with his daughter’s handprint inscribed on it. This image draws a link between the narrator and Kabuliwallah as men with daughters they love dearly. With the move to bond the narrator and the Kabuliwallah, Tagore crafts a tale about finding common humanity despite all of the differences that two men may have.

It’s worth noting here that one of the things that makes Tagore such an innovator given the context he was writing in was his unconventional narrative structure. Indeed, this story doesn’t play out over some sort of conflict and resolution like a typical narrative (or the adventure stories that the narrator writes) might. Instead, Tagore develops a set of relationships and shows us how those relationships play out when tempered by the sands of time.

Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Character sketch of kabuliwala

A traveling fruit and nut merchant from Afghanistan, the Kabuliwallah develops an unlikely friendship with a five-year-old girl while in Calcutta. After a period of time in jail, the Kabuliwallah returns to meet the girl, only to find her on her...

Discuss the contribution of Tagore to Indian education discussed in Uma Gupta's book.

I'm sorry, this is a short-answer question forum designed for text specific questions. I am unfamiliar with the book you've cited above.

Comment on themes of Tagore’s writing,

GradeSaver as a complete theme page readily available for your use in its study guide for the unit.

Study Guide for Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories

Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories study guide contains a biography of Rabindranath Tagore, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories

- Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories Summary

- Character List

Lesson Plan for Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for Rabindranath Tagore: Short Stories

- Introduction

- Family history

- Life and events

- The Man from Kabul

We first met Naajab on a dreary December evening. It was very cold and the wind pricked our faces with…

Arnab Banerjee | New Delhi | March 29, 2017 9:23 am

(PHOTO: SNS)

We first met Naajab on a dreary December evening. It was very cold and the wind pricked our faces with sharp, icy needles. We had just got off the bus and right in front of us, inside the bus stop shelter, was this tall gaunt man playing Hedwigs theme on his violin. My daughter, being a recently indoctrinated, diehard Harry Potter fan, was understandably excited. She stood rooted, rapt in awestruck admiration. I had to remind her that she would be late for her ballet lesson and Miss Sarah wouldnt be too happy. She asked me for a pound and with the greatest possible gentleness and care, deposited it inside the upturned, tattered cap on the pavement in front of the violinist, who had probably just met his biggest fan that evening.

I hurried along almost dragging my daughter by her hand. She continued to look behind her and though I did not turn back to see, I instinctively knew that that the fascinating object of her admiration was also holding her adoring gaze with a big toothy grin and violently nodding away at her, amid the gradual quickening tempo of the fiddling. When we came back to the bus stop after the lesson, much to the disappointment of my daughter, he was gone.

Advertisement

After that we saw him every week on our way to ballet lessons. If he was playing anything else on the violin, he would stop at once, as soon as he saw us, and immediately strike up Hedwigs theme to my daughters evident satisfaction.

Whats your name? he asked my daughter, one evening.

Rukmini, she mumbled shyly.

Mini, he laughed out loud, Mini, the leetil one, ha ha ha. He held out a bar of chocolate. Take, take, he insisted, I will be happy… Please!

Sensing my daughters hesitation and seeing the apparent delight on the face of the man opposite, I gave her a tiny nudge of encouragement. She almost snatched the chocolate off him and ran. As I trotted after her, I heard a guffaw as Hedwigs theme came back again on the airwaves. That evening, after dropping my daughter off, I came back to the bus stop. It was a relief to hear something else being played for a change. As I got into the shelter, he stopped playing and looked up, a little apprehensively. I rummaged in my pockets and offered him a fiver, Very kind of you but you shouldnt. Those are expensive chocolates. He refused point-blank, Leetil girl, she is baby, I dont. Not wishing to dilute the sentiment, I changed the subject, Whats your name? Naajab You from Afghanistan? Yes Whereabouts? Kabul Been here long? 14 years. I leeve in Pinner. How come we did not see you in the summer? My daughters started ballet in August. Summer, I do odd jobs here there. Help in garden. Garden, did you say? Perhaps you can help me then. The squirrels have dug up all my tulip bulbs. Can you replant them and cover the bed with some netting? Yes Tomorrow? Yes Eleven in the morning? Yes, I will go I jotted down my address and handed it to him. Then I went back to get my daughter. When we came to the bus stop again, Naajab was gone. On the bus ride home, I could not help thinking that this was straight from the pages of Tagore. You know Tagore, dont you, I asked my daughter. In a flash she uncoiled like a jack-in-the-box and stood up. Before I knew what was happening, to my utter consternation, in her accented Bengali she began belting out, Jana Gana Mana Adhinayaka jaya he, Bharata Bhagya Bidhata. Fortunately, no one on the bus seemed to mind, some even attempted little indulgent smiles. I was glad this was London, such a child-friendly city. The little tykes can get away with murder here. As for me I was glad that I did not have to stand up. Tagore also wrote stories, I told her, a lot of very good stories. You should read them. Perhaps I will read them to you and your sister, one day, when I have time. The Man from Kabul, I was already translating in my mind for my daughters eventual paraphrased consumption.

True to his word, Naajab was there the next morning. And on time too! My daughter could not believe her luck when she saw him, though she was a tad disappointed when she discovered Naajab did not have his violin with him. In the garden, Naajab knew what he was doing. Within an hour he was done. When the doorbell rang, the tulips were back in their beds, the protective netting in place; everything swept up and cleaned; all tools, nettings and strings put away neatly in the shed. As I handed him a little more than the pro-rated London minimum wage, I thanked him for a job well done and asked if he could come next week to remove the dead annuals and put them on a new compost heap.

Soon Naajab was a regular feature in our lives. Hedwigs theme on Friday evenings and his pottering about in the garden on Saturday mornings became routine. So where did you learn the violin, Naajab? I asked him one day. In Kabul I play rubab. One garden job here I find violin in shed. I take it. I listen to radio and play. Violin not so difficult. Not for you Naajab. You are a man of many talents.

Winter gave way to spring. Summer followed. My daughter started with her own violin lessons. We no longer had Hedwigs theme to entertain us on Friday evenings and I, for one, wasnt complaining. My daughter was a bit upset at first but since she saw Naajab every Saturday, she did not take it too much to heart. Naajab brought his violin on some Saturdays. The ever so familiar Hedwigs theme resumed, assailing my senses once again when I was on the phone with my mother in Calcutta. Rukmini lost her shyness and leaned heavily on Naajab when he played the violin. She taught him jelly on a plate, which Naajab, after a few exaggerated false starts and punctuated with shrill reprimands, Finally got it, to the exhilarated delight of both my daughters who, holding hands, broke into an impromptu dance. They played in the garden after Naajab finished work and all three grinned and giggled and rolled on the lawn laughing out loud till it was time for Naajab to tear himself away to his next job of the day. So when were you in Kabul last, Naajab? 14 years You havent been back since you came? No Do you have family Naajab? Yes, in Kabul. Two boys one girl. Do you Skype them? Do you Facetime them? No! Internet no good in Kabul. I talk to them. I send them money. How old are your children? Two, five and seven. But you said you havent been home for 14 years? Two, five and seven when I leeve Kaboul. 14 years ago. I leeve when they sleep. They dont see me go. So they are all grown up now? He shrugged his shoulders. Why dont you go back? They need money. I make money here. I dont go back. If I go back I cant come.

It was as I had feared. I had been providing employment to an illegal immigrant and had put myself on the wrong side of the law. Her Majestys law enforcement officers owed me a visit; social service too, when they found out we let our daughters play with Naajab, unsupervised. When I come I fill papers. Make me a refugee I ask. Afghanistan no safe. They take papers. Two years I get letter. Go back they say. Afghanistan is peace. No war no more. Democracy. I tear letter. I pack, I leeve Kent. I come to Harrow. I dont go back. I work. I make money. I send money home. Dont we all, I thought to myself. If they make me refugee I can bring family. That day we made a decision. Till he wanted, we would employ Naajab in some capacity or the other in summer and winter. He would see my daughters grow up. Not that it would lessen, in any way, the unarticulated pain of not seeing his own children blossom into young men and women, but at least every week, he would see expectant faces light up with innocent joy whenever he came to the garden through the back gate. He could talk to them about the stories he knew but never got to tell and play games he would have played in the Kabul that was never far from his mind. Sitting in his little room off Pinner Lane, perhaps he could see before him, a little more clearly, his own little children growing up in the barren, war-ravaged mountainous terrain of Afghanistan.

Next week before leaving for the airport, I popped my head into my daughters room to say goodbye. Both were deep in sleep. I knew when I came back home on Thursday, they would have gone to bed. So they get to see me only on Friday? Naajab, you either have a heart of stone or else a bank of resolve and a well of sorrows that puts me to shame, I whispered. In the flight I opened my long neglected, well-worn copy of Tagores collected short stories at the The Man from Kabul. I started to read and began to paraphrase, My seven-year-old daughter Mini cannot live without chattering. I really believe that in all her life she has not wasted a minute in silenceTears came to my eyes. I forgot that he was a poor man from Kabul, while I was, but no, what was I more than he? He also was a father. The memory of the sleeping faces of his little children in their distant mountain home that Naajab carried inside him every moment of his life, reminded me of my own daughters.

- Short Story

Related posts

The last rites.

The people, those sneering “bhadraloks” watched and concluded that they shouldn’t meddle in a brawl between “two groups of anti-socials”.

Mr Mirza s ordeal

Nowadays, Sohorab drinks his flavoured Darjeeling tea while sitting on his cozy arm-chair in the balcony.

Short story – Suicide

Fula had no words to defend herself. She was shattered into pieces. There was a spontaneous flow of tears from her eyes —they reached her nostrils, lips and chin. She thought that life saves the cruellest for the poor.

You might be interested in

Devotees flock to Ayodhya’s Ram temple in large number for ‘Ram Navami’ celebration

‘Big achievement’: Chhattisgarh CM lauds security forces after 29 Naxals killed in encounter in Kanker

India will soon be Naxal-free: Amit Shah after 29 Naxals killed in Chhattisgarh operation

Top headlines.

29 Naxals killed in encounter with security forces in Chhattisgarh

Sidelining a woman’s freedom of choice

BJP’s Blueprint

Congress’ pitch

Black Sea Games

PM spells out India’s position on China

Congress’ Challenge

Bala Literary Guide

Bala Literary Guide offers English literature summaries for college students

Saturday 28 July 2018

The man from kabul - rabindranath tagore, no comments:, post a comment, endymion book i - john keats.

Endymion Book I - John Keats "Endymion" by John Keats is an epic poem divided into four books, each exploring themes of l...

- ESSENTIAL OF EDUCATION - SIR RICHARD LIVINGSTONE ESSENTIAL OF EDUCATION - SIR RICHARD LIVINGSTONE Introduction Sir Richard Livingstone is a famous British Educationist and a...

- THE PRAISE OF CHIMNEY SWEEPERS – CHARLES LAMB THE PRAISE OF CHIMNEY SWEEPERS – CHARLES LAMB The essay ‘The Praise of Chimney Sweepers’ reveals Lamb’s sympathy for the low and...

- THE BEST LAID PLANS - Farrel Mitchell THE BEST LAID PLANS Farrel Mitchell Farrel Mitchell is the author the one-act play “The Best Laid Plans”. It is about the plan of ...

Rabindranath Tagore

Ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions, the narrator, rahamat / the “kabuliwala”, the narrator’s wife / mini’s mother.

Kabuliwala by Rabindranath Tagore

Fresh Reads

The Fruitseller from Kabul

My five years’ old daughter Mini cannot live without chattering. I really believe that in all her life she has not wasted a minute in silence. Her mother is often vexed at this, and would stop her prattle, but I would not. To see Mini quiet is unnatural, and I cannot bear it long. And so my own talk with her is always lively.

One morning, for instance, when I was in the midst of the seventeenth chapter of my new novel, my little Mini stole into the room, and putting her hand into mine, said: “Father! Ramdayal the door-keeper calls a crow a krow! He doesn’t know anything, does he?”

Before I could explain to her the differences of language in this world, she was embarked on the full tide of another subject. “What do you think, Father? Bhola says there is an elephant in the clouds, blowing water out of his trunk, and that is why it rains!”

And then, darting off anew, while I sat still making ready some reply to this last saying, “Father! what relation is Mother to you?”

“My dear little sister in the law!” I murmured involuntarily to myself, but with a grave face contrived to answer: “Go and play with Bhola, Mini! I am busy!”

The window of my room overlooks the road. The child had seated herself at my feet near my table, and was playing softly, drumming on her knees. I was hard at work on my seventeenth chapter, where Protrap Singh, the hero, had just caught Kanchanlata, the heroine, in his arms, and was about to escape with her by the third story window of the castle, when all of a sudden Mini left her play, and ran to the window, crying, “A Kabuliwala! a Kabuliwala!” Sure enough in the street below was a Kabuliwala, passing slowly along. He wore the loose soiled clothing of his people, with a tall turban; there was a bag on his back, and he carried boxes of grapes in his hand.

I cannot tell what were my daughter’s feelings at the sight of this man, but she began to call him loudly. “Ah!” I thought, “he will come in, and my seventeenth chapter will never be finished!” At which exact moment the Kabuliwala turned, and looked up at the child. When she saw this, overcome by terror, she fled to her mother’s protection, and disappeared. She had a blind belief that inside the bag, which the big man carried, there were perhaps two or three other children like herself. The pedlar meanwhile entered my doorway, and greeted me with a smiling face.

So precarious was the position of my hero and my heroine, that my first impulse was to stop and buy something, since the man had been called. I made some small purchases, and a conversation began about Abdurrahman, the Russians, she English, and the Frontier Policy.

As he was about to leave, he asked: “And where is the little girl, sir?”

And I, thinking that Mini must get rid of her false fear, had her brought out.

She stood by my chair, and looked at the Kabuliwala and his bag. He offered her nuts and raisins, but she would not be tempted, and only clung the closer to me, with all her doubts increased.

This was their first meeting.

One morning, however, not many days later, as I was leaving the house, I was startled to find Mini, seated on a bench near the door, laughing and talking, with the great Kabuliwala at her feet. In all her life, it appeared; my small daughter had never found so patient a listener, save her father. And already the corner of her little sari was stuffed with almonds and raisins, the gift of her visitor, “Why did you give her those?” I said, and taking out an eight-anna bit, I handed it to him. The man accepted the money without demur, and slipped it into his pocket.

Alas, on my return an hour later, I found the unfortunate coin had made twice its own worth of trouble! For the Kabuliwala had given it to Mini, and her mother catching sight of the bright round object, had pounced on the child with: “Where did you get that eight-anna bit?”

“The Kabuliwala gave it me,” said Mini cheerfully.

“The Kabuliwala gave it you!” cried her mother much shocked. “Oh, Mini! how could you take it from him?”

I, entering at the moment, saved her from impending disaster, and proceeded to make my own inquiries.

It was not the first or second time, I found, that the two had met. The Kabuliwala had overcome the child’s first terror by a judicious bribery of nuts and almonds, and the two were now great friends.

They had many quaint jokes, which afforded them much amusement. Seated in front of him, looking down on his gigantic frame in all her tiny dignity, Mini would ripple her face with laughter, and begin: “O Kabuliwala, Kabuliwala, what have you got in your bag?”

And he would reply, in the nasal accents of the mountaineer: “An elephant!” Not much cause for merriment, perhaps; but how they both enjoyed the witticism! And for me, this child’s talk with a grown-up man had always in it something strangely fascinating.

Then the Kabuliwala, not to be behindhand, would take his turn: “Well, little one, and when are you going to the father-in-law’s house?”

Now most small Bengali maidens have heard long ago about the father-in-law’s house; but we, being a little new-fangled, had kept these things from our child, and Mini at this question must have been a trifle bewildered. But she would not show it, and with ready tact replied: “Are you going there?”

Amongst men of the Kabuliwala’s class, however, it is well known that the words father-in-law’s house have a double meaning. It is a euphemism for jail, the place where we are well cared for, at no expense to ourselves. In this sense would the sturdy pedlar take my daughter’s question. “Ah,” he would say, shaking his fist at an invisible policeman, “I will thrash my father-in-law!” Hearing this, and picturing the poor discomfited relative, Mini would go off into peals of laughter, in which her formidable friend would join.

These were autumn mornings, the very time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it, and at the sight of a foreigner in the streets, I would fall to weaving a network of dreams,—the mountains, the glens, and the forests of his distant home, with his cottage in its setting, and the free and independent life of far-away wilds. Perhaps the scenes of travel conjure themselves up before me, and pass and repass in my imagination all the more vividly, because I lead such a vegetable existence, that a call to travel would fall upon me like a thunderbolt. In the presence of this Kabuliwala, I was immediately transported to the foot of arid mountain peaks, with narrow little defiles twisting in and out amongst their towering heights. I could see the string of camels bearing the merchandise, and the company of turbaned merchants, carrying some of their queer old firearms, and some of their spears, journeying downward towards the plains. I could see—but at some such point Mini’s mother would intervene, imploring me to “beware of that man.”

Mini’s mother is unfortunately a very timid lady. Whenever she hears a noise in the street, or sees people coming towards the house, she always jumps to the conclusion that they are either thieves, or drunkards, or snakes, or tigers, or malaria or cockroaches, or caterpillars, or an English sailor. Even after all these years of experience, she is not able to overcome her terror. So she was full of doubts about the Kabuliwala, and used to beg me to keep a watchful eye on him.

I tried to laugh her fear gently away, but then she would turn round on me seriously, and ask me solemn questions.

Were children never kidnapped?

Was it, then, not true that there was slavery in Cabul?

Was it so very absurd that this big man should be able to carry off a tiny child?

I urged that, though not impossible, it was highly improbable. But this was not enough, and her dread persisted. As it was indefinite, however, it did not seem right to forbid the man the house, and the intimacy went on unchecked.

Once a year in the middle of January Rahmun, the Kabuliwala, was in the habit of returning to his country, and as the time approached he would be very busy, going from house to house collecting his debts. This year, however, he could always find time to come and see Mini. It would have seemed to an outsider that there was some conspiracy between the two, for when he could not come in the morning, he would appear in the evening.

Even to me it was a little startling now and then, in the corner of a dark room, suddenly to surprise this tall, loose-garmented, much bebagged man; but when Mini would run in smiling, with her, “O! Kabuliwala! Kabuliwala!” and the two friends, so far apart in age, would subside into their old laughter and their old jokes, I felt reassured.

One morning, a few days before he had made up his mind to go, I was correcting my proof sheets in my study. It was chilly weather. Through the window the rays of the sun touched my feet, and the slight warmth was very welcome. It was almost eight o’clock, and the early pedestrians were returning home, with their heads covered. All at once, I heard an uproar in the street, and, looking out, saw Rahmun being led away bound between two policemen, and behind them a crowd of curious boys. There were blood-stains on the clothes of the Kabuliwala, and one of the policemen carried a knife. Hurrying out, I stopped them, and enquired what it all meant. Partly from one, partly from another, I gathered that a certain neighbour had owed the pedlar something for a Rampuri shawl, but had falsely denied having bought it, and that in the course of the quarrel, Rahmun had struck him. Now in the heat of his excitement, the prisoner began calling his enemy all sorts of names, when suddenly in a verandah of my house appeared my little Mini, with her usual exclamation: “O Kabuliwala! Kabuliwala!” Rahmun’s face lighted up as he turned to her. He had no bag under his arm today, so she could not discuss the elephant with him. She at once therefore proceeded to the next question: “Are you going to the father-in-law’s house?” Rahmun laughed and said: “Just where I am going, little one!” Then seeing that the reply did not amuse the child, he held up his fettered hands. “Ali,” he said, “I would have thrashed that old father-in-law, but my hands are bound!”

On a charge of murderous assault, Rahmun was sentenced to some years’ imprisonment.

Time passed away, and he was not remembered. The accustomed work in the accustomed place was ours, and the thought of the once-free mountaineer spending his years in prison seldom or never occurred to us. Even my light-hearted Mini, I am ashamed to say, forgot her old friend. New companions filled her life. As she grew older, she spent more of her time with girls. So much time indeed did she spend with them that she came no more, as she used to do, to her father’s room. I was scarcely on speaking terms with her.

Years had passed away. It was once more autumn and we had made arrangements for our Mini’s marriage. It was to take place during the Puja Holidays. With Durga returning to Kailas, the light of our home also was to depart to her husband’s house, and leave her father’s in the shadow.

The morning was bright. After the rains, there was a sense of ablution in the air, and the sun-rays looked like pure gold. So bright were they that they gave a beautiful radiance even to the sordid brick walls of our Calcutta lanes. Since early dawn to-day the wedding-pipes had been sounding, and at each beat my own heart throbbed. The wail of the tune, Bhairavi, seemed to intensify my pain at the approaching separation. My Mini was to be married to-night.

From early morning noise and bustle had pervaded the house. In the courtyard the canopy had to be slung on its bamboo poles; the chandeliers with their tinkling sound must be hung in each room and verandah. There was no end of hurry and excitement. I was sitting in my study, looking through the accounts, when some one entered, saluting respectfully, and stood before me. It was Rahmun the Kabuliwala. At first I did not recognise him. He had no bag, nor the long hair, nor the same vigour that he used to have. But he smiled, and I knew him again.

“When did you come, Rahmun?” I asked him.

“Last evening,” he said, “I was released from jail.”

The words struck harsh upon my ears. I had never before talked with one who had wounded his fellow, and my heart shrank within itself, when I realised this, for I felt that the day would have been better-omened had he not turned up.

“There are ceremonies going on,” I said, “and I am busy. Could you perhaps come another day?”

At once he turned to go; but as he reached the door he hesitated, and said: “May I not see the little one, sir, for a moment?” It was his belief that Mini was still the same. He had pictured her running to him as she used, calling “O Kabuliwala! Kabuliwala!” He had imagined too that they would laugh and talk together, just as of old. In fact, in memory of former days he had brought, carefully wrapped up in paper, a few almonds and raisins and grapes, obtained somehow from a countryman, for his own little fund was dispersed.

I said again: “There is a ceremony in the house, and you will not be able to see any one to-day.”

The man’s face fell. He looked wistfully at me for a moment, said “Good morning,” and went out. I felt a little sorry, and would have called him back, but I found he was returning of his own accord. He came close up to me holding out his offerings and said: “I brought these few things, sir, for the little one. Will you give them to her?”

I took them and was going to pay him, but he caught my hand and said: “You are very kind, sir! Keep me in your recollection. Do not offer me money!—You have a little girl, I too have one like her in my own home. I think of her, and bring fruits to your child, not to make a profit for myself.”

Saying this, he put his hand inside his big loose robe, and brought out a small and dirty piece of paper. With great care he unfolded this, and smoothed it out with both hands on my table. It bore the impression of a little band. Not a photograph. Not a drawing. The impression of an ink-smeared hand laid flat on the paper. This touch of his own little daughter had been always on his heart, as he had come year after year to Calcutta, to sell his wares in the streets.

Tears came to my eyes. I forgot that he was a poor Cabuli fruit-seller, while I was—but no, what was I more than he? He also was a father. That impression of the hand of his little Parbati in her distant mountain home reminded me of my own little Mini.

I sent for Mini immediately from the inner apartment. Many difficulties were raised, but I would not listen. Clad in the red silk of her wedding-day, with the sandal paste on her forehead, and adorned as a young bride, Mini came, and stood bashfully before me.

The Kabuliwala looked a little staggered at the apparition. He could not revive their old friendship. At last he smiled and said: “Little one, are you going to your father-in-law’s house?”

But Mini now understood the meaning of the word “father-in-law,” and she could not reply to him as of old. She flushed up at the question, and stood before him with her bride-like face turned down.

I remembered the day when the Kabuliwala and my Mini had first met, and I felt sad. When she had gone, Rahmun heaved a deep sigh, and sat down on the floor. The idea had suddenly come to him that his daughter too must have grown in this long time, and that he would have to make friends with her anew. Assuredly he would not find her, as he used to know her. And besides, what might not have happened to her in these eight years?

The marriage-pipes sounded, and the mild autumn sun streamed round us. But Rahmun sat in the little Calcutta lane, and saw before him the barren mountains of Afghanistan.

I took out a bank-note, and gave it to him, saying: “Go back to your own daughter, Rahmun, in your own country, and may the happiness of your meeting bring good fortune to my child!”

Having made this present, I had to curtail some of the festivities. I could not have the electric lights I had intended, nor the military band, and the ladies of the house were despondent at it. But to me the wedding feast was all the brighter for the thought that in a distant land a long-lost father met again with his only child.

Related posts:

- The Fighting Cocks and the Eagle by Aesop

- The Camel and the Pig by Ramaswami Raju

- The Elfin Hill by Hans Christian Andersen

- The Nightingale by Hans Christian Andersen

Why I Write by George Orwell

What is fascism by george orwell, the shoemaker and the devil by anton chekhov.

Try aiPDF , our new AI assistant for students and researchers

Summary and Questions Answers of Kabuliwala by Robindranath Tagore

Table of Contents

Kabuliwala by Rabindranath Tagore

Introduction

Kabuliwala is a subtle exploration of the links of friendship, affection, and separation in the relationship between a middle-aged Pathan trader and a five-year-old Bengali child. The story is set in early twentieth-century Kolkata. It is a simple storey about a father’s love for his daughter and how that love is passed on to another young girl. It is a love that knows no bounds in terms of race, religion, or language.

Please enable JavaScript

Kabuliwala, which translates to “The Kabuli Man” (also known as “The Fruitseller from Kabul”), is a storey about a historic and loving bond between India and Kabul city.

Summary of Kabuliwala

Mini, a five-year-old girl, and Rahamat, a dried fruit vendor in Kabul, are the central characters in the “Kabuliwala” storey. Mini is talkative and innocent, calm, and gives his load of nuts to someone who has been suspended. Kabuliwala patiently listens to Mini. Mini’s father is friends with the young man, and he loves it when he sees him laughing at Mini and talking to him about life in Afghanistan and what he has seen on his travels among the Kabuliwala fruit sellers.

Because of the narrator, the pastor invites a Ramat (dry fruit) trader from Kabul to a wedding interview with an innocent Mini, and the Kabuliwala reunites with his daughter and has a happy life in Kabul. Tagore’s short “Kabuliwala” storey, from a collection of Tagore stories, is recounted by the father of an unknown man named Mini, and the reader knows he is reading a communication narrative by reading Tagore.

Mini, a five-year-old girl from Kabul who is a suspended fruit seller, and Kabuliwala, a man who deals with Calcutta’s past, are the primary characters in the novel. Mini is the narrator of this narrative and is a sweet and talkative girl who falls in love with her Babuji. Mini’s father, who is five years old, tells the storey “Kabuliwala”

Kabuliwali arrives in India for a year to sell dried fruit and meets Mini. Rahmat Chhabi Biswas, a middle-aged Afghan fruit seller, arrives in Calcutta to peddle her wares and make friends with Mini Oindrila Tagore (Tinku Tagore), a Bengali girl who reminds her of her Afghan daughter. The Kabuliwala have a daughter who is the same size as Mini, and they believe Mini is their daughter, with whom they share the responsibilities of a father and his daughter.

When Mini’s father learns of Kabuliwala’s hardship, he offers her enough money to visit her daughter in Kabul. Kabuliwali pays one rupee to her daughter for each dried fruit she provides her for free. Kabuliwala’s father begins a pleasant relationship with Mini after learning about him, and they meet every day.

The narrative begins with a teacher chatting to his five-year-old daughter Mini, who has spent years learning to speak and was born prematurely and has never stopped speaking since. Mini’s mother encourages her to quiet down, but her father allows her to express herself and converses with her.

As the youngsters fled the dreadful Kabuliwala, a young girl named Mini risked to be her friend. Her father remembers her and she visits him every day to give him news and gifts. A father dressed in Afghan baggy clothes, like his five-year-old daughter Mini, had learnt to speak within a year of his birth and had never stopped shouting grapes and nuts in the streets.

In this short storey about the friendship between a five-year-old girl named Mini, a member of the Calcutta royal family, and an Afghan fruit seller in Kabul, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) can be found. Tagore was the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, and was considered one of the most important literary figures. This is the twentieth century. Despite being written in the first person, “Cabuliwallah” is a storey presented from the perspective of Mini’s father. Tagore reminds us that they are both fathers, and that a first-person description of a man with a grieving daughter whom he has not seen in years aids him in seeing her as a person rather than a killer.

The vendor spends the evening at the narrator’s house, talking to Mini, as part of his plans to go to Calcutta to collect the money the customer owes him.

Questions and Answers of Kabuliwala

Question 1 : Read the extract given below and answer the questions that follow.

“Stopping her game abruptly Mini ran to the window which overlooked the main road, and began calling out at the top of her voice, “Kabuliwala, O Kabuliwala!”

i) Where is Mini at this time? How can you say that she is a very talkative girl?

Answer : Mini is at home at the moment. Her behaviour indicates that she is a very talkative girl. Her father says she has not squandered a single awakened moment of her life by remaining mute.

ii) What was Mini doing before the game?

Answer : Mini sat with her father before going outside to play. She was questioning him, but he was too preoccupied with his work. Mini was sent to play with Bhola, so he told her to go. She got down next to his writing desk and began playing knick-knacks.

iii) What was Mini’s father doing at this time?

Answer : Mini’s father, who is the narrator of the chapter, was working on the seventeenth chapter of the novel. In the seventeenth chapter of the novel, Pratap Singh and Knachanmala were jumping off a high balcony at night with a friend. That did not stop Mini from asking him a lot of different kinds of questions though.

iv) What did Mini do when the Kabuliwala approached the house?

Answer : Mini immediately paused her gaming and shouted out to the Kabuliwala. He walked up to the home. Mini, on the other hand, raced inside and was nowhere to be found. The Kabuliwala and his sack frightened her.

v) Give the description of the Kabuliwala.

Answer : The Kabuliwala was a tall, unkempt Afghan street trader. He was wearing a turban, carrying a bag, and holding a few crates of dry grapes. Rahamat was the name of the boy. Mini had a childhood worry that the Kabuliwala kidnapped children and held them in his bag.

Question 2 : Read the extract given below and answer the questions that follow.

“The Kabuliwala saw Mini and became confused; their good-natured humour of old also didn’t work out. In the end, with a smile, he asked, ‘Girl, are you going to the in-law’s house?’ ”

i) Who is the Kabuliwala?

Answer : The Kabuliwala was a tall, unkempt Afgan street trader. He wore a turban, had a bag over his shoulders, and held a few boxes of dry grapes. Rahamat was his name.

ii) Why was the Kabuliwala confused?

Answer : The Kabuliwala happened to notice a girl he did not recognise. In fact, he last saw Mini when she was a very young child. She was now all dressed up and ready to be married. As a result, he was perplexed because he had that childlike vision of her in his mind.

iii) What had happened to the Kabuliwala?

Answer : The Kabuliwala had been sent to jail for causing grievous injury to a man. He had a customer in the narrator’s colony who denied paying his debt for a shawl. Things got nasty and Rahamat had stabbed the man in the heat of the moment.

iv) Why was the Kabuliwala so attached to the narrator’s daughter?

Answer : Rahamat was a native of Afghanistan. He came to Kolkata for business. He had a daughter like Mini back home. He longed to be with her. He saw his daughter’s reflections in Mini and hence got attached to her very much.

v) How did Mini react to his question? How would she earlier react to his question?

Answer : When Rahamt inquired as to her whereabouts, she became embarrassed and her face turned scarlet. Immediately, she exited the room. Previously, she was unaware of the meaning of the term ‘in-laws’ and would dismiss the question. Earlier, she would respond to him by asking if he intended to see his in-laws, to which he would respond that he would thump them.

Long Answer Type Question

Question 1 : Comment on the changing relationship between Mini and Rahamat. Why was Rahamat so attached to Mini?

Answer : Mini was five years old when she first encountered Rahamat. She was a very talkative child, and even her father did not always have ears for her. The narrator was working one day when Mini began to pester him with questions. He advised her to seek entertainment elsewhere. She was engaged in a game when Kabuliwala arrived. She dashed towards the window and yelled at him. However, when he smiled as he approached the house, she raced inside and was no longer visible. She was terrified as a child that he would kidnap children.

Rahamt arrived at the house, and the narrator decided that now was the time to help Mini overcome her worries. He summoned Mini. She approached and stood anxiously, her gaze suspiciously fixed on the Kabuliwala and his bag. He offered Mini some raisins and apricots, but she rejected and remained snuggled against the narrator’s knees. That was the conclusion of their initial meeting.

A few days later, the narrator noticed his young daughter seated on a bench next Rahamat and chattering incessantly. The narrator realised that Mini had never encountered a more receptive listener in her little life. Additionally, he had given her some raisins and nuts. The narrator requested that he refrain from doing so in the future and handed him a half-rupee coin. Rahamat instead gave the currency to Mini, sparking a full-fledged argument at the narrator’s house.

The narrator discovered that this was not their second encounter. They had been meeting on a near-daily basis. Rahamat won the child’s heart. They also kept a few of their personal gags on hand. Then something happened in their brief friendship. Rahamat was charged with causing grievous bodily harm to his customer and sentenced to several years in prison.

He was imprisoned, and Mini grew up to marry. Rahamat was released on the wedding day. He paid a visit to Mini. He was perplexed to see Mini because he had a mental image of her as a young girl. He inquired as to if she was on her way to her in-place. law’s Mini became embarassed and retreated inside.

That was their final encounter. Rahamat slouched on the floor, heaving a long, deep sigh as he realised his own daughter back home in Afghanistan had grown up to be just like Mini. He always carried a small impression of her with him. He was so devoted to Mini that he saw a reflection of his own small daughter in her.

Discover more from Smart English Notes

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Improving writing skills since 2002

(855) 4-ESSAYS

Type a new keyword(s) and press Enter to search

Man from kabul.

- Word Count: 552

- Approx Pages: 2

- View my Saved Essays

- Downloads: 7

- Grade level: High School

- Problems? Flag this paper!

In the short story, "The Man From Kabul- by Rabindranath Tagore, there was a man known as the Kabuliwallah. He was a man from the mountains of Afghanistan, who made his living as a peddler of fruits and nuts. He had left his family behind to make his way through life, and during this time he began longing to see his daughter. Then one day he came across a young girl named Mini whom he felt resembled his daughter and he became attached. Through the beginning of their relationship the Kabuliwallah and Mini were the best of friends. They would sing and laugh together for hours on end and some days the Kabuliwallah would bring the young girl dried fruits and nuts, but instead of paying the usual price for these goods the Kabuliwallah would give them to the young girl not out of personal profit but out of sheer happiness of the thought that Mini would enjoy them. One of the important pieces of the relationship and the story was when Mini and the Kabuliwallah would sing. The special part of the song went as followed; the Kabuliwallah would say: "Well, little one, and when are you going to your father-in-law's house?- then Mini would say: " are you going there?- and shaking his fist at an invisible policemen he would reply: "I shall thrash my father-in-law."" At the time Mini did not understand that this term father-in-law meant jail, and as for the Kabuliwallah he looked at this expression as a place of free room and board. Later on the Kabuliwallah was to turn return to Mini one afternoon, but that morning Mini's father saw the Kabuliwallah in the street covered in blood and being arrested. Then her father had come to learn later of an assault of a man over a business dispute committed by the Kabuliwallah. Years later the Kabuliwallah returned at the time of Mini's wedding, but he had changed after jail. His hair was short he seemed aged and he carried no bag of goods at his side. Also Mini had changed a great deal over the years; she had become a woman and was on her way to marriage.

- Page 1 of 2

Essays Related to Man from Kabul

1. womens rights around the world.

From the New York Times there is an article titled "The 15 Women Awaiting Justice in Kabul Prison." ... Her father tracked them down and brought her back to Kabul and imprisoned. ... Muzghan does not deserve to be put behind bars because she didn't want to marry the man her parents chose. ... I have always known that under Islamic law a man can take up to four wives but I learned from this article that there is absolutely no way out of it for women, unless they want to face imprisonment. ... American prisons are far from this one. ...

- Word Count: 742

- Approx Pages: 3

- Grade Level: High School

2. The Underground Girls of Kabul

Within the context of Jenny Nordberg's novel, "The Underground Girls of Kabul," she interviews girls in Afghanistan posing as boys. This novel describes several case studies of women from different social classes and age. ... Although the Taliban fell from power in 2001, most of the rules they set regarding women still hold sway. According to female parliamentarian Azita, progress for women is limited to urban areas, "Yes, more women are seen on the streets of Kabul and a few other larger cities since the Taliban was in power, and more girls are enrolled in school, but just...

- Word Count: 887

- Approx Pages: 4

- Has Bibliography

3. The Kite Runner - The Unattianable Dream

Life shifts from sunny and pleasurable to grim and difficult. ... When he goes to write a check, the elderly man that owns the store routinely asks to see an ID. ... In Kabul, they used a simple tree branch as a credit card. ... In Afghanistan, Baba is widely accepted as a leader and a trustworthy man; he is accustomed to believing everyone recognizes him. ... Out of necessity to provide for themselves, Amir and Baba stray even further from the image they hold in Kabul. ...

- Word Count: 1319

- Approx Pages: 5

4. Women under the Taliban

From the last sermon of Prophet Mohammed The Taliban entered Kabul on Sept 24 1996, after executing Najibullah, the last communist president of Afghanistan. ... During its rise to power, the Taliban received support from Pakistan and from Afghans seeking a return to peace after nearly two decades of war. ... It is estimated that by the early 1990s, 70% of schoolteachers, 50% of government workers and university students, and 40% of doctors in Kabul were women. ... (A man must not hear a woman's footsteps.) Ban on women riding in a taxi without a mahram. ...

- Word Count: 2219

- Approx Pages: 9

5. Fatherhood in The Kite Runner

This act of heroism proves Baba is a man who stand for what he believes in and has good, pure morals. ... Another man who displays courage and risks his life for a child in need is Amir. Amir goes back to his homeland, Afghanistan, to rescue Hassan's son Sohrab from war-ravaged Kabul, a place so devastated even he, who was born and raised in Afghanistan, could not recognize. ... Baba, a wealthy man in afghan standards, displays this necessary characteristic. ... "(46) The lives of Kabul's less fortunate children change for the better when Baba buys an orphanage. ...

- Word Count: 745

6. Amir from The Kite Runner - Character Analysis

Coming from a privileged society, Amir is accustomed to having whatever he wanted. ... However, after receiving Rahim Khan's call, Amir flew back to Kabul in order to safe Sohrab, whom existence was uncertain. ... Kabul is dangerous, you know that, and you'd have me risk everything for" (233) a stranger. ... A boy who would not stand up for himself, can become a man who can stand up to anything. ... Contradicting Baba's predictions, Amir changed himself for the better; from selfish to selfless, from cowardly to courageous, from dishonest to honest. ...

- Word Count: 751

7. Book Review - The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

Amir and his father live in a nice house in Kabul, Afghanistan, with their two Hazara (Afghan minority) servants. ... Finally, he is given the chance to redeem himself by going to Kabul and rescuing Hassan's son. Early in the book, Baba says to Rahim Kahn that "A boy who won't stand up for himself becomes a man who can't stand up to anything" (17). ... A prime example comes after Hassan's operation, when the bandages are removed from his face. ... Soon, it was just a pink jagged line running up from his lip. ...

- Word Count: 1836

- Approx Pages: 7

8. Short Story - From Dream to Reality

"Well at least it keeps us safe and away from the scary Taliban's.... As the two girls where walking back to a dilapidated area in Kabul, where beggars and homeless people found beside their destroyed and abandoned homes that have been bombed and artillery. ... " "Do you see that man over there? ... "Look Soraya, were leaving Kabul!...

- Word Count: 798

9. Christmas in the Sandbox

On Christmas day of 2009 during a return convoy from Bagram, Afghanistan the communications rang out "Oh s---! ... All of a sudden while in between two buildings that looked to be like some type of market, you hear the radio chatter start and smoke rolling off of the tires from a couple of trucks up ahead. ... Once the casualty was stabilized, we loaded him into the back of the MRAP and moved forward to Kabul International Airport Hospital where the individual later died. ... After the investigation was complete, it had been determined that the man had dishonored his family and wanted ...

- Word Count: 660

The Kabuliwala Summary | Rabindranath Tagore

“Kabuliwala” by Tagore is a tale of heart-rending friendship between a 5-year-old Bengali girl Minnie and an Afghan moneylender, Abdur Rahman or Rahamat. The story beautifully ties a bond of mutual affection and the unconventional relationship between the two.

Table of Contents

Inception of an Odd Friendship

The voice of the story is lent by the father of Minnie. Rahamat, who is a hawker of dry fruits and shawls from Kabul, frequents the Bengali locales where Minnie and her family reside. He was a strapping, turban-clad man and fascinated Minnie.

One day she called him from the window of her house. But as he approached closer she got startled and ran back inside. Minnie’s father talked to Rahmat and learned about his family in Kabul.

He introduced Minnie to him with the title of Kabuliwala. To make her more comfortable Rahmat offered some dry fruits to Minnie. He started calling Minnie as Khuki (a child).

As their friendship blossomed, Minnie and Rahmat started meeting and interacting every day. Rahmat narrated stories of his homeland to Minnie and the young girl happily returned the warmth with her own innocent tales and playfulness. Kabuliwala listened to the young girl with great intent and relish.

Misfortune Overtakes the Kabuliwala

However, the maidservant of Mini’s parents started filling the ears of Rama, Minnie’s mother regarding the Kabuliwala’s true intention. Soon, Minnie’s mother grew suspicious of this flourishing friendship and feared that Rahmat might even kidnap and sell her daughter. She also stopped paying Kabuliwala for his goods.

On the other hand, Kabuliwala’s woes magnified as he got arrested for stabbing a customer after getting involved in a scuffle. The tiff started due to non-payment of a Rampuri shawl that the Kabuliwala sold to the customer. The customer denied having ever bought the shawl and that caused Rahmat to lose his control.

During the trial, he confessed to killing the man even after being advised against it by his lawyer. The judge decided to reduce his punishment to 10-years imprisonment after being impressed by his honesty. After getting released several years later he went to see Minnie.

Return of a Friend

To his surprise, a lot had changed and the day he arrived was actually Minnie’s wedding day. But when Minnie’s father realized his presence, he asked Rahmat to leave the premises owing to his ill-fated and inauspicious absence.

Kabuliwala obliged but while leaving offered some raisins for Minnie. He also showed a scruffy piece of paper with a handprint of his daughter that he left in Kabul.

Seeing that her father’s heart melted and he called Minnie. Mini was dressed and embellished like a bride but was too apprehensive to meet her long-forgotten friend.

Kabuliwala was taken aback to see a girl he could not recognize and struggled to cope with the reality of the time he lost while imprisoned. He was tormented by the thought of having lost his own daughter’s childhood. She would have been a grown woman like Minnie.

Minnie’s father understood his precarious condition and offered him enough money for a safe trip back to Kabul and a reunion with his own daughter. Even Minnie’s mother, realizing her misjudgment, extended the money she saved for Minnie’s wedding ceremony.

Minnie’s father set aside a portion of the wedding expenses like for lights etc in order to arrange 100 rupees for Rahmat. In a way, they could sympathize with the plight of another parent longing for his long-separated daughter.

Key Lessons

The fundamental message of the story is that people have the ability to do good as well as bad to others. Often, it is easier to side with our fears and suspect someone who is not like us. It can be a different skin colour or a different language.

But if we are patient with people and try to understand their situations and problems then we can find some common ground. They go through the same emotions and conflicts as we do.

They are also faced with difficult choices like us. Therefore, we must show empathy for their struggles if we expect to receive the same from them In the end, we all live to make each other’s life easier and worth living. Refer to this site for a shorter summary.

Further Reading

- Play quiz on Kabuliwala

- Questions-Answers of Kabuliwala

Related Posts:

- The Woman Speaks to the Man who has Employed her Son Poem by Lorna Goodison Summary, Notes and Line by Line Explanation in English

- Good Country People Short Story by Flannery O'Connor Summary and Analysis

- Random Harry Potter Character Generator

- Daddy Poem Summary and Line by Line Explanation by Sylvia Plath in English

- Active vs. Passive Voice: Choosing the Right Voice for Your Writing

- Random Arabic Name Generator [from english]

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Shadow City, Invisible City: Walking Through an Ever-Changing Kabul

Taran khan on life in an uncertain afghanistan.

It comes in waves.

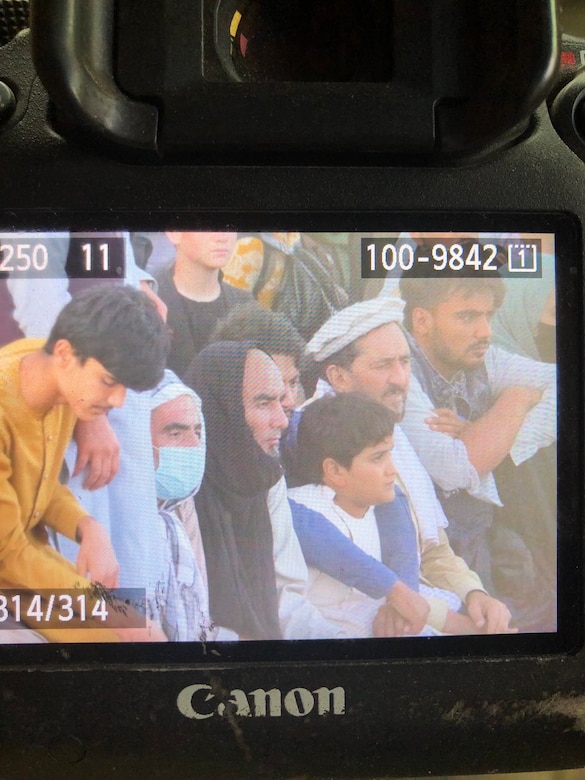

On my phone: Three missed calls and several voice messages, hours before the last evacuation flight leaves Kabul. My fingers falter between scrolling through and forwarding messages, stopped short by a little girl’s face on my screen.

Tayyaba is at the airport in Kabul, in the middle of the botched evacuation of Afghans by the United States and its allies. Her mother’s name is on the list of evacuees but hers is not. Neither is her brother’s or her grandmother’s. Her mother, Shazia, is divorced and has spent years working with different organizations in Kabul to help vulnerable Afghan women. None of these employers have turned up to support Shazia in this dire moment and she sees no other way for her family but to flee the country.

I was sent Shazia and Tayyaba’s information by their relative, my friend, an Afghan now living in Europe. Was there anyone who could help get them through the barricades? Anyone who could get their names on the list? On a plane? Should they wait where they were, in a sewage ditch under the blazing sun? Or should they go back to a city controlled by the Taliban; go home to a home that is profoundly changed?

My first return to Kabul was in the autumn of 2006. It was August, a time that a friend had told me was the most beautiful season in the city. The toot (mulberry) trees are bright with color, he had said. You can see them everywhere.

It was a time that was not quite war and not peace. Over the next few years, I would walk through the city and watch the seasons turn. I saw arghawan trees blossom in spring and spent summer weekends on picnics with friends. On Christmas I saw the streets emptied of their customary rush of Land Cruisers, as most consultants and international staff departed for the holidays.

In the years that followed the security situation progressively worsened. I watched as the international community and the Afghan government withdrew behind sandbags and boom barriers. Concrete walls topped by concertina wires took over entire thoroughfares, dividing the city into a cruel hierarchy. If there was a blast in their vicinity, these walls were likely to turn the impact outwards, towards those on the streets.

I recognize these same walls again now in the images from Kabul airport, including those of Tayyaba’s family. Keeping thousands of Afghans at bay, cutting them off from the flights departing to safety.

In 2013, on my last journey to Kabul, most of my conversations with friends revolved around the formal end of the NATO combat mission, scheduled for the next year. Their talk was of departures to other cities, of different lives in faraway places where they could envisage a future. A future that had vanished for them from Kabul.

Kabul changed years before the Taliban entered the city on August 15th, 2021, and yet in the news and in mainstream narratives, I find it presented as a surprise.

Walking through Kabul then, I had found it to be what one historian has described as an “amnesiac city”—a place where the past is obscured below the surface, leaving few visible traces. Writing about Kabul, I had also collided with its periodic, deliberate invisibility; how it appeared and vanished to the outside world. Now you see it, now you don’t. Surprise, I find, is another word for wilful forgetting, a different shade of amnesia. A way to talk only of those who were “saved,” rather than those who had no choice but to remain.

In Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Marco Polo describes city after city to the great ruler Kublai Khan. Some of these, or all of these, could be real. Or they could be fictions, places existing only in the imagination of the listener, or of the narrator. They could be stories woven by them both.

One of these is Eusapia, a city that exists in reverse below the earth, as a city of the dead. Reading Calvino’s description of these mirroring terrains, above and below the ground, I think of Kabul on a spring day in 2013, seen from a hill in the Graveyard of the Pious Martyrs, the Shuhada-e-Saliheen. This valley on the southern edge of the city is dotted with Muslim shrines and pilgrimages now, but it has been hallowed ground for over 2000 years. Where I stood, on Tepe Naranj, or Orange Hill, a team of archaeologists were excavating the remains of a Buddhist monastery, raising steps and prayer chambers from the Kabuli earth.

Around the site, the city circled closer. Houses were being built between the graves. Wire fences protected the excavations from the creeping sprawl of habitations. From this vantage point, Kabul’s diverse past lay revealed to me as if on the pages of a book, as though to prove it existed. I think of that spot now, under the control of the Taliban, and of the rueful reality faced by the archaeologists, that sometimes the safest way to protect Afghanistan’s heritage was to leave it buried.

Wandering through the graveyards and monuments of Kabul, I had found few formal memorials to the upheavals of its recent past. The city has changed many times without leaving traces on its terrain. But it is also possible to see it in reverse, to find that there are, in fact, few things that do not serve as memorials in this city. In the middle of a crowded Soviet-era apartment complex, for instance, stands a shrine to a young woman chased to her death by local militia during the civil war. A ruined cinema, an empty spot at a table, a missing father’s photo on a wall. Like Calvino’s city of Eusapia, below the Kabul of the surface that is unmarked by memory, exists a Kabul of remembering.

My grandmother, who had grown up in northern India in a home marked by rigid gender segregation, told me how she used to listen to the poets who frequented the male quarters of her house through cracks in the wall.

In the days after the Taliban’s takeover, I listened to Kabul through cracks in the silence that descended on the city. In the voices of friends I could reach on the phone, and behind their fear and their laughter, their assurances and their hesitating requests, I heard the streets and the soundtrack of the city’s everyday life, away from the transient media glare.