The fiscal policy response to the pandemic

- Download Final Paper

- Download Online Appendix

- Download Data & Programs

- Download General Discussion on COVID Panel

Subscribe to the Economic Studies Bulletin

Christina d. romer christina d. romer nonresident senior fellow - economic studies.

March 24, 2021

The paper summarized here is part of the spring 2021 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity , the leading conference series and journal in economics for timely, cutting-edge research about real-world policy issues. Research findings are presented in a clear and accessible style to maximize their impact on economic understanding and policymaking. The editors are Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Northwestern University Professor of Economics Janice Eberly and Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Harvard University Professor of Economics James Stock . See the spring 2021 BPEA event page to watch paper presentations and read summaries of all the papers from this edition.

The enormous $5.2 trillion U.S. fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic likely has put the economy on a path to recovery, but it may end up discouraging future spending on other pressing needs, warns a paper presented at a Brookings Papers on Economic Activity conference on March 25.

Though the response “runs the gamut from highly useful and appropriate to largely ineffective and wasteful,” Christina D. Romer of the University of California-Berkeley judges that the economy “is likely to do well” unless “vaccinations flag or become less effective as new variants emerge”

U.S. spending early in the pandemic (through July) was much larger as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) than in most other countries—50 percent larger than in the United Kingdom and roughly three times as much as in France, Italy, or Spain, she notes in The fiscal policy response to the pandemic . Moreover, countries’ fiscal responses to the pandemic were not related to their initial debt loads—a change from the usual pattern in which countries with high debt loads respond less strongly to crises.

Romer argues that pandemic recessions are fundamentally different from ordinary recessions, and thus require different policy responses. She writes: “The unique characteristics of a pandemic recession imply that fiscal policy during a pandemic should be geared much more toward helping those who are directly harmed rather than toward increasing aggregate demand more generally. That is, it should be aimed at providing social insurance rather than broad stimulus.”

The $599 billion added to the federal deficit to pay for public health measures was “clearly necessary and valuable,” she writes. “Because both the recovery of demand and the safe pace of economic growth depend on getting the virus under control, it was imperative to take aggressive action on public health measures.” Likewise, the expansion of unemployment insurance, at $748 billion, was “clearly appropriate to the unique circumstances of the pandemic.” Also, federal aid to state and local governments ($597 billion) was a cost-effective way to help them meet pandemic-related needs, offset lost tax revenue, and avoid layoffs.

But some federal spending was misguided. Although direct payments (up to $1,200 per person followed by $600 and $1,400) “surely gave many households a much-needed boost at a difficult time,” she writes. “Most of the money went to people who had not been economically harmed by the pandemic.”

The Paycheck Protection Program ($808 billion), which provided forgivable loans to smaller businesses that largely maintained their payrolls, was “an interesting and noble experiment, but it was problematic on many levels,” Romer writes. Two studies suggest the implied cost per job preserved was “on the order of $225,000 to $350,000.”

She also identifies areas that would have warranted increased spending. The lack of a substantial federal program to provide hazard pay to frontline workers who endangered their health by remaining on the job was “an important missed opportunity.” And, although the swift development of vaccines was a public health triumph, “the painfully slow progression from vaccine discovery to actual inoculation strongly suggests that more funding and effort was needed to set up effective and rapid distribution programs.” And, she notes, the United States conducts fewer virus tests per 1,000 people than many other rich countries and “is even worse at genetic sequencing of cases to identify variants and patterns of transmission.”

The fiscal response to the pandemic will push the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio from 79 percent before it emerged to 110 percent by the end of the 2023 budget year, according to projections she cites. That likely won’t precipitate a fiscal crisis because “demand for U.S. government debt remains as strong as ever.” But she worries that the reduction in “fiscal space” will discourage policymakers from tackling issues such as climate change, crumbling infrastructure, and persistent poverty.

If “stimulus payments that did little to help those most affected by the pandemic end up precluding spending $1 trillion on infrastructure or climate change in the next few years, the United States will have made a very bad bargain indeed,” she writes.

Acknowledgement

David Skidmore authored the summary language for this paper.

Romer, Christina . 2021. “The Fiscal Policy Response to the Pandemic . ” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 89-110.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The author did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this paper. They are currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this paper.

The views expressed by the authors, discussants and conference participants in BPEA are strictly those of the authors, discussants and conference participants, and not of the Brookings Institution. As an independent think tank, the Brookings Institution does not take institutional positions on any issue. Please contact Haowen Chen ( [email protected] ) if you have any questions.

Economic Studies

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

April 3, 2024

March 29, 2024

The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C.

10:00 am - 11:30 am EDT

Estimating the impact of the financial cycle on fiscal policy

- Published: 30 June 2023

- Volume 65 , pages 2669–2709, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Beau Soederhuizen 1 ,

- Rutger Teulings ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9528-9617 1 &

- Rob Luginbuhl 1

215 Accesses

Explore all metrics

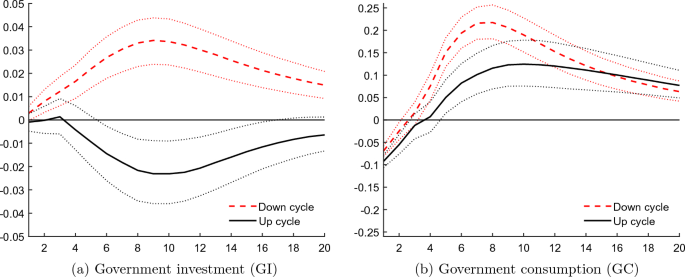

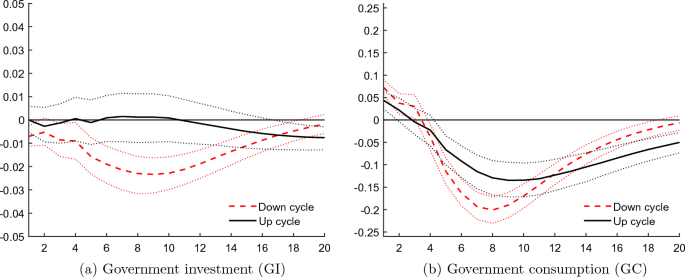

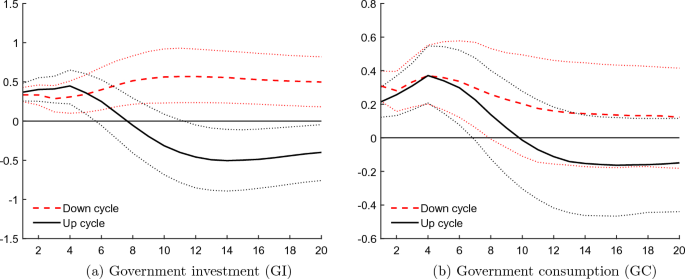

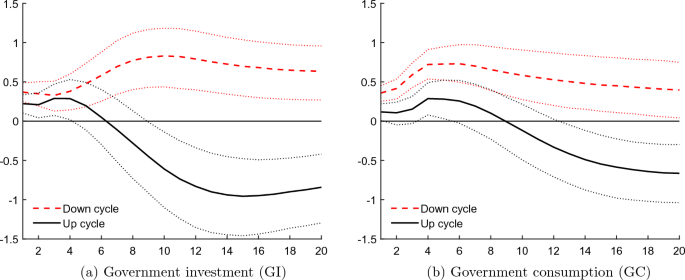

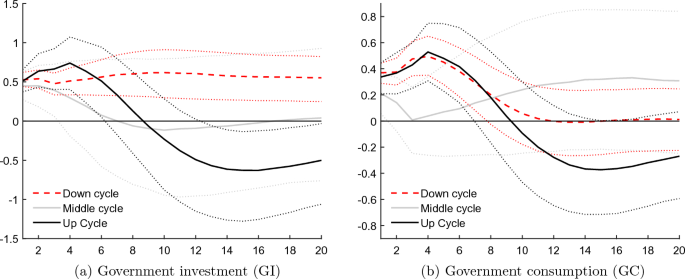

We investigate the impact of the financial cycle on fiscal policy by estimating fiscal multipliers for different types of government spending that are contingent on two states determined by the financial cycle. To obtain our estimates, we extend the threshold VAR method from a single country to a panel of high-income countries. Our results indicate that the multiplier for government investment is affected by the state of the financial cycle: while the initial impact is positive for both states, in an upturn it turns negative, while in a downturn it remains positive. In the case of government consumption, the multiplier does not seem to significantly depend on the financial cycle. However, jointly conditioning on the financial and business cycles produces multipliers of government consumption which vary over the states of both cycles. This contrasts with the results for government investment which are left essentially unchanged by the joint conditioning on the four states defined by both cycles.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

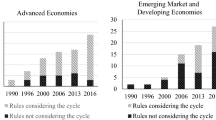

Fiscal rules and procyclicality: an empirical analysis

Sangita Misra & Rajiv Ranjan

Regime-Dependent Fiscal Multipliers in the United States

Gilles Dufrénot, Aurélia Jambois, … Guillaume Khayat

Fiscal policy and aggregate demand in the USA before, during, and following the Great Recession

David Cashin, Jamie Lenney, … William Peterman

The term “tight” for the credit regime suggests that the mechanism is supply driven, whereas it is also possible that the low level of credit is at least partially due to low demand.

Our code is based on the univariate TVAR estimation program by Gabriel Bruneau, freely available from his homepage.

We experimented with regime-dependent averages, this being the most flexible specification. This did not influence our main results in any noteworthy fashion. Results are available upon request.

Replacing the real interest rate by the nominal rate, to allow for the strict monetary policy reaction, does not alter the results.

Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, USA.

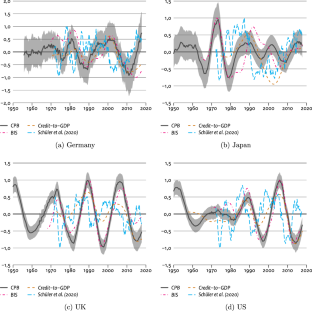

These data are based on the detrended credit-to-GDP gap using the HP-filter with \(\lambda _{\textrm{HP}}= 4\) 00,000. We obtained these detrended series from the BIS (Drehmann et al. 2016 ). The relatively large value of \(\lambda _{\textrm{HP}}\) they use to detrend the credit gap only removes the long-term trend, leaving the longer frequency cycle associated with the financial cycle in their series. This approach, however, also allows the higher frequencies associated with the business cycle to pass through the filter and remain in their financial cycle measure. To obtain a cleaner series containing only the longer financial cycle frequencies, we HP-filter the BIS’s series again with \(\lambda _{\textrm{HP}}=1600\) and use the resulting HP-filter trend component to obtain a smoother financial cycle. In this way we remove the higher business cycle frequencies from the BIS’s series.

The Schüler cycles we received from the authors are smoothed using a six-quarter one-sided moving average based on the weights of a Bartlett window. We demean the Schüler cycles to ensure that they fluctuate around zero, instead of 0.5 as in Schüler et al. ( 2020 ). Their approach, the power cohesion method, maps the growth rates of financial variables (such as credit volumes and house prices) into an empirical cumulative distribution function between zero and one. Therefore, these series do not exhibit long-term trends.

The BIS kindly provided us with their financial cycle estimates.

A special thanks to Yves Schüler and colleagues for providing their financial cycle estimates.

For example, in the cast of the BIS estimates, we lose in total 366 observations, which is a little under 10% of our total number of observations.

The phase concordance index is a measure for co-movement between two cycles, say, f and b (see Harding and Pagan 2002 ). The corresponding expression for country i is given by \(\Phi ^{fb}_{i}=1/T\sum _t\left( \phi ^f_{it}\phi ^b_{it}+(1-\phi ^f_{it})(1-\phi ^b_{it})\right) \) , where \(\phi ^{.}_{it}\) is 1 when the cycle is in an upturn and 0 when it is in a downturn as defined in the paper. If the phase concordance index equals 0 both cycles are perfectly counter-cyclical and when it equals 1 both cycles are perfectly pro-cyclical. If two cycles are independent we obtain the expected phase concordance, which can be obtained by replacing \(\phi ^{.}_{it}\) with fraction of time spent in an upturn for both cycles.

We have obtained higher concordance indices of around 0.6 between the Schüler cycle with a lead of two to eight quarters and the CPB cycle measures. A lead of two to eight quarters is actually short compared to the length of the financial cycle and there is still substantial overlap between the up- and down-phases of the Schüler and the CPB cycle.

When necessary we seasonally adjust the data using the X-12 algorithm.

Using other values for \(\lambda _{\textrm{HP}}\) yields qualitatively similar results.

We follow Hamilton ( 2018 ), who advises to use \(p=3\) and \(h=8\) for quarterly data.

If we include a short-term nominal interest rate (of the OECD’s Main Economic Indicators) instead of the real rate, all impulse responses are (roughly) unchanged aside from the interest rate. In this case the responses of the nominal rate display a resemblance of a standard Taylor rule for monetary policy with an increase following a rise in inflation, and a reduction after a drop in inflation.

We use the Fisher information matrix to calculate the standard error. However, because the log-likelihood is highly nonlinear, it is not certain that this results in a reliable standard error.

For the endogenous threshold 40% of the observations occur during an upturn of the financial cycle, while in the case of the exogenous threshold this percentage is 48%.

Austria, Germany, Italy, South Korea, The Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland show distinctly different patterns from the other countries and the overall main results. Denmark deviates to a lesser extent. For some of these countries, the data cover a shorter time period. However, it is also possible that an insufficient lag length, or a different underlying economic mechanism driving the interaction between the financial cycle and the investment multiplier might explain these results. We leave this for future research.

See footnote 16, replacing the real rate for a nominal rate does not change the results.

Germany, France, Japan, Norway, South Korea, Spain, The Netherlands, Switzerland and the USA show different patterns from the other countries and the overall main results (also see footnote 19).

To save space, the results are available upon request.

The results are also robust for the use of 2 lags, corresponding to 8 lags when using quarterly data. Since the information criteria only support the use of at most 6 lags when using quarterly data, there is no point in adding more lags to the model.

Changing the order of the endogenous variables leads indeed to identical results.

We find the same result with private GDP when using annual data.

Data are obtained from the World Bank over the period 1960–2016. The results are almost identical if we use the openness in 2016 instead of the entire sample.

Open economies: Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. The remaining eleven countries are closed economies.

Data obtained from Oxford Economics over the period 1980–2018.

Other orderings of the VAR model including debt lead to similar results.

Using the level of debt in 2017 instead of the entire sample, and using a cut-off of 100% such as Corsetti et al. ( 2012 ), yields similar results.

Highly indebted countries: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands and the USA. The remaining ten countries are all lowly indebted countries.

Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain.

We have also estimated this truncated sample using an endogenous threshold. In this case the results are very similar to our baseline results.

Placing the financial cycle as endogenous variable in a different ordering does not change the results.

Their model also includes seasonal components to correct for any seasonality in the data. We omit this aspect of the model here for simplicity.

Note that the covariance matrices of both disturbance vectors \(\vec \kappa _{it}^{C}\) and \(\vec \kappa _{it}^{C*}\) are restricted to be equal. This restriction is standard, see Harvey ( 1991 ) for details.

Asymptotically, however, the two financial cycles will be qualitatively the same, only differing in their amplitude.

Abiad A, Furceri D, Topalova P (2016) The macroeconomic effects of public investment: evidence from advanced economies. J Macroecon 50:224–240

Article Google Scholar

Afonso A, Baxa J, Slavík M (2018) Fiscal developments and financial stress: a threshold VAR analysis. Empir Econ 54(2):395–423

Aikman D, Lehnert A, Liang JN, Modugno M (2016) Financial vulnerabilities, macroeconomic dynamics, and monetary policy. In: Finance and economics discussion series 2016-055. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

Alichi A, Shibata I, Tanyeri K(2019) Fiscal policy multipliers in small states. IMF working papers 19/72. International Monetary Fund

Antonakakis N, Breitenlechner M, Scharler J (2015) Business cycle and financial cycle spillovers in the G7 countries. Q Rev Econ Finance 58:154–162

Auerbach AJ, Gorodnichenko Y (2012) Measuring the output responses to fiscal policy. Am Econ J Econ Policy 4(2):1–27

Balke NS (2000) Credit and economic activity: credit regimes and nonlinear propagation of shocks. Rev Econ Stat 82(2):344–349

Batini N, Eyraud L, Forni L, Weber A (2014) Fiscal multipliers: size, determinants, and use in macroeconomic projections. IMF technical notes and manuals 2014/04. International Monetary Fund

Baum A, Poplawski-Ribeiro M, Weber A (2012) Fiscal multipliers and the state of the economy. IMF working papers 12/286. International Monetary Fund

Beetsma R, Giuliodori M, Klaassen F (2008) The effects of public spending shocks on trade balances and budget deficits in the European Union. J Eur Econ Assoc 6(2–3):414–423

Beetsma R, Giuliodori M, Klaassen F (2009) Temporal aggregation and SVAR identification, with an application to fiscal policy. Econ Lett 105(3):253–255

Benetrix A, Lane P (2015) Financial cycles and fiscal cycles. Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, pp 315–346

Google Scholar

Blanchard O, Perotti R (2002) An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output. Q J Econ 117(4):1329–1368

Boehm CE (2020) Government consumption and investment: Does the composition of purchases affect the multiplier? J Monet Econ 115(C):80–93

Borio C (2014) The financial cycle and macroeconomics: What have we learnt? J Bank Finance 45(C):182–198

Borio C, Disyatat P, Juselius M (2017) Rethinking potential output: embedding information about the financial cycle. Oxf Econ Pap 69(3):655–677

Borsi MT (2018) Fiscal multipliers across the credit cycle. J Macroecon 56(C):135–151

Bouakez H, Guillard M, Roulleau-Pasdeloup J (2020) The optimal composition of public spending in a deep recession. J Monet Econ 114(C):334–349

Budina NT, Gracia B, Hu X, Saksonovs S (2015) Recognizing the bias; financial cycles and fiscal policy. IMF working papers 15/246. International Monetary Fund

Caggiano G, Castelnuovo E, Colombo V, Nodari G (2015) Estimating fiscal multipliers: news from a non-linear world. Econ J 125(584):746–776

Caldara D, Kamps C (2017) The analytics of SVARs: a unified framework to measure fiscal multipliers. Rev Econ Stud 84(05):1015–1040

Callegari G, Melina G, Batini N (2012) Successful austerity in the United States, Europe and Japan. IMF working papers 12/190. International Monetary Fund

Canzoneri M, Collard F, Dellas H, Diba B (2016) Fiscal multipliers in recessions. Econ J 126(590):75–108

Carrillo J, Poilly C (2013) How do financial frictions affect the spending multiplier during a liquidity trap? Rev Econ Dyn 16(2):296–311

Cerutti E, Claessens S, Rose AK (2019) How important is the global financial cycle? Evidence from capital flows. IMF Econ Rev 67(1):24–60

Christiano LJ, Eichenbaum M, Evans CL (1999) Monetary policy shocks: What have we learned and to what end? In: Taylor JB, Woodford M (eds) Handbook of macroeconomics, vol 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 65–148

Chapter Google Scholar

Christiano L, Eichenbaum M, Rebelo S (2011) When is the government spending multiplier large? J Polit Econ 119(1):78–121

Claessens S, Kose MA, Terrones ME (2012) How do business and financial cycles interact? J Int Econ 87(1):178–190

Coenen G, Straub R, Trabandt M (2012) Fiscal policy and the great recession in the Euro area. Am Econ Rev 102(3):71–76

Corsetti G, Meier A, Müller GJ (2012) What determines government spending multipliers? Econ Policy 27(72):521–565

Danthine J-P (2012) Taming the financial cycle. Swiss National Bank, Speech at SUERF Colloquium 2012, Zurich

Dosi G, Fagiolo G, Napoletano M, Roventini A (2013) Income distribution, credit and fiscal policies in an agent-based Keynesian model. J Econ Dyn Control 37(8):1598–1625

Drehmann M, Borio C, Tsatsaronis K (2012) Characterising the financial cycle: Don’t lose sight of the medium term! BIS working papers 380. Bank for International Settlements

Drehmann M, Pradhan K, Wooldridge P, Santos M, Vidal J, Szemere R (2016) Recent enhancements to the BIS statistics. BIS Q Rev, pp 35–44

Ellahie A, Ricco G (2017) Government purchases reloaded: informational insufficiency and heterogeneity in fiscal VARs. J Monet Econ 90:13–27

Fernández-Villaverde J (2010) Fiscal policy in a model with financial frictions. Am Econ Rev 100(2):35–40

Ferraresi T, Roventini A, Fagiolo G (2015) Fiscal policies and credit regimes: a TVAR approach. J Appl Econom 30(7):1047–1072

Gechert S, Mentges R (2018) Financial cycles and fiscal multipliers. Appl Econ 50(24):2635–2651

Gechert S, Rannenberg A (2018) Which fiscal multipliers are regime-dependent? A meta-regression analysis. J Econ Surv 32(4):1160–1182

Gieve SJ (2008) The financial cycle and the UK economy. Speech at London Stock Exchange. Bank of England, London, p 2008

Gonzalez-Garcia JR, Lemus A, Mrkaic M (2013) Fiscal multipliers in the ECCU. IMF working papers 13/117. International Monetary Fund

Hamilton JD (2018) Why you should never use the Hodrick–Prescott filter. Rev Econ Stat 100(5):831–843

Hansen BE (1996) Inference when a nuisance parameter is not identified under the null hypothesis. Econometrica 64(2):413–430

Hansen BE (1997) Inference in TAR models. Stud Nonlinear Dyn Econom 2(1):1–16

Harding D, Pagan A (2002) Dissecting the cycle: a methodological investigation. J Monet Econ 49(2):365–381

Harvey AC (1991) Forecasting, structural time series models and the Kalman filter. Cambridge Books, no. 9780521405737. Cambridge University Press

Hebous S (2011) The effects of discretionary fiscal policy on macroeconomic aggregates: a reappraisal. J Econ Surv 25(4):674–707

Holmström B, Tirole J (1998) Private and public supply of liquidity. J Polit Econ 106(1):1–40

Huidrom R, Kose MA, Lim JJ, Ohnsorge FL (2020) Why do fiscal multipliers depend on fiscal positions? J Monet Econ 114(C):109–125

Ilzetzki E, Mendoza EG, Végh CA (2013) How big (small?) are fiscal multipliers? J Monet Econ 60(2):239–254

Jordà Ò, Taylor AM (2016) The time for austerity: estimating the average treatment effect of fiscal policy. Econ J 126(590):219–255

Jordà Ò, Schularick M, Taylor AM, Ward F (2019) Global financial cycles and risk premiums. IMF Econ Rev 67(1):109–150

Kamps C (2005) The dynamic effects of public capital: VAR evidence for 22 OECD countries. Int Tax Public Finance 12(4):533–558

Laeven L, Valencia F (2018) Systemic banking crises revisited. IMF working paper, 206, pp 1–47

Leeper EM, Walker TB, Yang S-CS (2010) Government investment and fiscal stimulus. J Monet Econ 57(8):1000–1012

Leeper EM, Traum N, Walker TB (2017) Clearing up the fiscal multiplier morass. Am Econ Rev 107(8):2409–2454

Luginbuhl R (2020) Estimation of the financial cycle with a rank-reduced multivariate state-space model. CPB discussion paper. CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis

Luginbuhl R, Soederhuizen B, Teulings R (2019) Estimates of the financial cycle for advanced economies. CPB discussion paper. CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis

Maddala DS (1977) Econometrics. McGraw-Hill, New York

Mumtaz H, Sunder-Plassmann L (2021) Nonlinear effects of government spending shocks in the USA: evidence from state-level data. J Appl Econom 36(1):86–97

Mumtaz H, Pirzada A, Theodoridis K (2018) Non-linear effects of oil shocks on stock prices. Working papers 865. Queen Mary University of London, School of Economics and Finance

Pereira AM (2000) Is all public capital created equal? Rev Econ Stat 82(3):513–518

Pesaran M, Smith R (1995) Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. J Econom 68(1):79–113

Praet P (2016) Financial cycles and monetary policy. ECB, Speech in the Context of a Panel on International Monetary Policy, Beijing

Ramey VA (2011a) Can government purchases stimulate the economy? J Econ Lit 49(3):673–685

Ramey VA (2011b) Identifying government spending shocks: it’s all in the timing. Q J Econ 126(1):1–50

Ramey VA (2019) Ten years after the financial crisis: What have we learned from the renaissance in fiscal research? J Econ Perspect 33(2):89–114

Ramey VA, Shapiro MD (1998) Costly capital reallocation and the effects of government spending. In: Carnegie-Rochester conference series on public policy, vol 48. Elsevier, pp 145–194

Ramey VA, Zubairy S (2018) Government spending multipliers in good times and in bad: evidence from US historical data. J Polit Econ 126(2):850–901

Romer CD, Romer DH (2010) The macroeconomic effects of tax changes: estimates based on a new measure of fiscal shocks. Am Econ Rev 100(3):763–801

Rozite K, Bezemer DJ, Jacobs JPAM (2019) Towards a financial cycle for the US, 1973–2014. N Am J Econ Finance 50:101023

Rünstler G, Vlekke M (2018) Business, housing, and credit cycles. J Appl Econom 33(2):212–226

Schüler YS, Hiebert PP, Peltonen TA (2020) Financial cycles: characterisation and real-time measurement. J Int Money Finance 100:102082

Strohsal T, Proaño CR, Wolters J (2019) Characterizing the financial cycle: evidence from a frequency domain analysis. J Bank Finance 106:568–591

Traum N, Yang S-CS (2015) When does government debt crowd out investment? J Appl Econom 30(1):24–45

Tsay RS (1998) Testing and modeling multivariate threshold models. J Am Stat Assoc 93(443):1188–1202

Winter J, Koopman SJ, Hindrayanto I, Chouhan A (2017) Modeling the business and financial cycle in a multivariate structural time series model. DNB Working Papers 573. Netherlands Central Bank, Research Department

Woodford M (1990) Public debt as private liquidity. Am Econ Rev 80(2):382–388

Download references

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, P.O. Box 80510, 2508 GM, The Hague, The Netherlands

Beau Soederhuizen, Rutger Teulings & Rob Luginbuhl

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rutger Teulings .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We would like to thank Roel Beetsma, Adam Elbourne, Albert van der Horst, Clemens Kool, Bert Smid, seminar participants and the anonymous referees for their valuable comments that helped improve this paper.

A State space model of CPB financial cycle

We denote the credit data for country i by \(y^1_{it}\) and the housing price index by \(y^2_{it}\) and define the data column vector \(\vec {y}_{it}=\left( y^1_{it}, y^2_{it}\right) '\) . Similarly, we denote the vector of the financial cycles for credit and the housing price index of country i as \(\vec {f}_{it}\) . We use the same notion for the vector of the business cycle components, \(\vec {b}_{it}\) . The state space model also includes two local linear trend components, one for credit and one for the housing price index, giving rise to the vector \(\vec {\mu }_{it}\) to capture the growth dynamics in the data. Each trend component is itself affected by a random walk growth component, which for both series we also denote by a vector: \(\vec {\beta }_{it}\) . Using this notation we can express the model in Luginbuhl et al. ( 2019 ) as follows Footnote 35 :

where the financial cycle component is given by

and the business cycle component by

Note that the components \(\vec {b}_{it}^{*}\) and \(\vec {f}_{it}^{*}\) are only required for the construction of the cycle components \(\vec {b}_{it}\) and \(\vec {f}_{it}\) . Also note that the model contains the vector disturbance terms \(\vec \varepsilon _{it}\) , \(\vec \eta _{it}\) , \(\vec \zeta _{it}\) , as well as \(\vec \kappa _{it}^C \sim N\left( 0, \Omega _{\kappa ,i}^C \right) \) and \(\vec \kappa _{it}^{C*} \sim N\left( 0, \Omega _{\kappa ,i}^C \right) \) for \(C=b\) or f . Footnote 36

The state space model (Luginbuhl et al. 2019 ) use in the estimation of the financial cycle is closely related to work of Rünstler and Vlekke ( 2018 ) and Winter et al. ( 2017 ), which are also based on unobserved cycle components to model financial cycles. The main difference here being that the estimation method by Luginbuhl et al. ( 2019 ) imposes the restriction of there being only one shared stochastic process driving both financial cycle components in their bi-variate model. This restriction is necessary to help identify one financial cycle for each country. In fact the financial cycle estimate \(f_{it}\) is the cycle component for the credit data. Although the housing price index shares the same stochastic disturbance driving the cycle, the housing price index has its own starting value. As a result, the housing price index financial cycle can deviate from the credit cycle in the initial part of the sample period. Footnote 37

The bi-variate state space models distinguish between the business cycle and the financial cycle by assuming that the financial cycle has a longer period cycle than the business cycle. The financial cycles are full-information, Kalman smoothing estimates obtained using Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo or MCMC methods.

B Data series

See Tables 4 and 5 .

C Correlation and phase concordance between financial and business cycles

See Tables 6 and 7 .

D IRFs of inflation and real interest rate, baseline specification

See Figs. 5 and 6 .

Impulse responses: inflation. See Sect. 5 for an elaboration on these results, and the note to Fig. 2 for a description of the construction of the confidence bands

Impulse responses: real interest rate. See Sect. 5 for an elaboration on these results, and the note to Fig. 2 for a description of the construction of the confidence bands

E Baseline results in alternative specifications

1.1 e.1 figures for baseline results in alternative specifications.

See Figs. 7 , 8 and 9 .

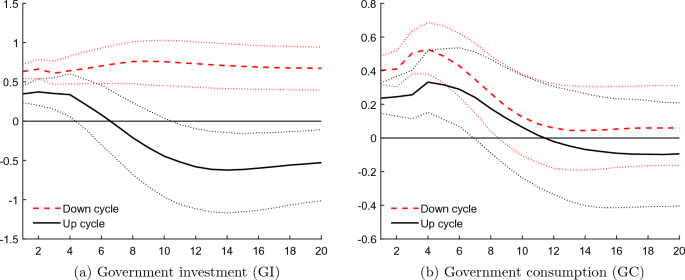

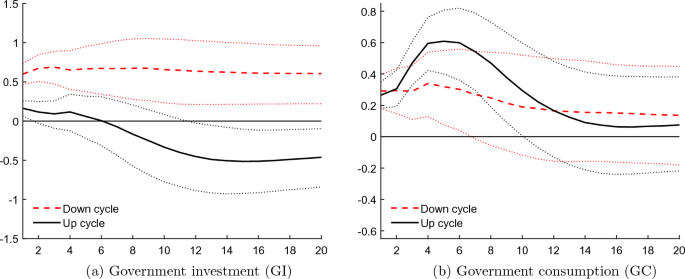

Cumulative fiscal multipliers with an endogenous threshold. See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

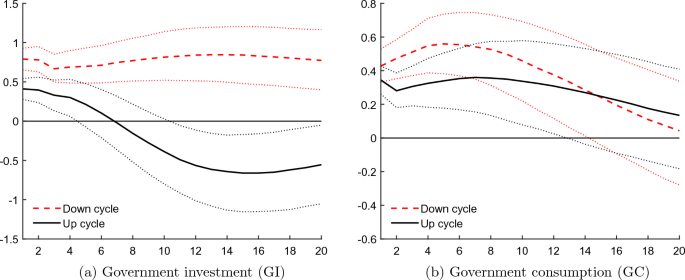

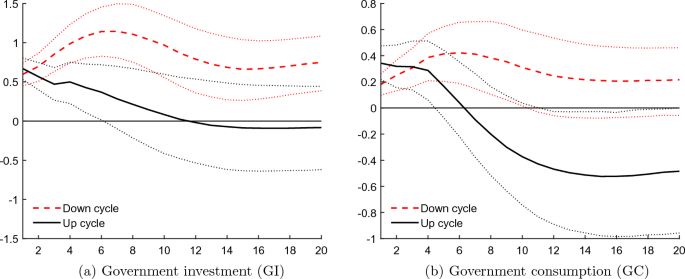

Detrending with the projection method. We detrend all non-stationary variables using the projection method, where we follow Hamilton ( 2018 ) and project the variable at time \(t+8\) onto the four most recent values \(t-3,\ldots ,t\) . See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

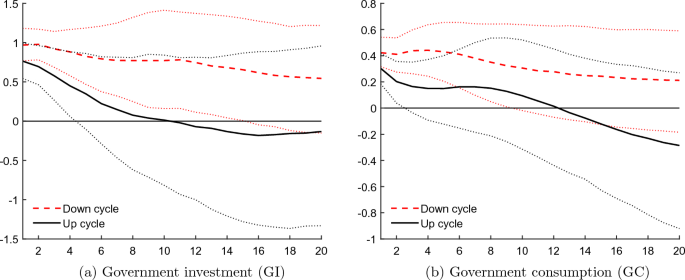

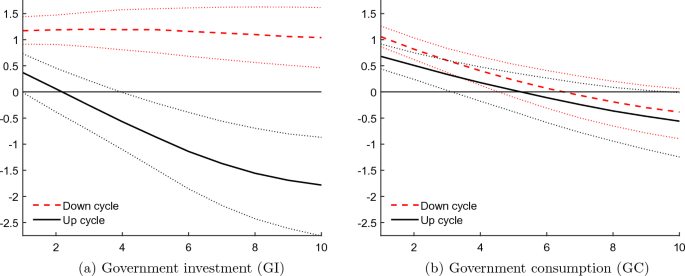

Cumulative fiscal multipliers using weighted mean group estimation. We only use 2 lags instead of 4 because of a shortage of degrees of freedom at the country level. We weight the country-specific cumulative fiscal multipliers using number of observations per country as weight and take the average to construct the weighted mean group estimate. See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

1.2 E.2 Alternative financial cycles

See Figs. 10 , 11 and 12 .

Cumulative fiscal multipliers using the BIS cycle as financial cycle. See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

Cumulative fiscal multipliers using credit-to-GDP gap as financial cycle. See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

Cumulative fiscal multipliers using the Schüler financial cycles. See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

F Additional figures of the robustness checks

See Figs. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 and 17 .

Cumulative fiscal multipliers with yearly data. The model is estimated with year data and include \(L=1\) lags. See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

Cumulative fiscal multipliers with private GDP as first endogenous variable. Private GDP is ordered as the first endogenous variable. Therefore, the cumulative multipliers are equal to one by construction in the first period. See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

Cumulative fiscal multipliers including debt-to-GDP as endogenous variable. Government debt-to-GDP is added to the baseline model as additional endogenous variable and is ordered between government spending real GDP. (Color figure online)

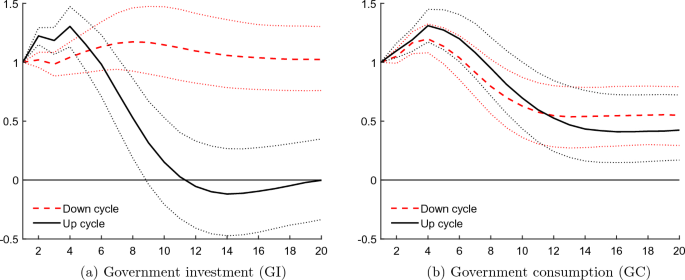

Cumulative fiscal multipliers with three regimes and two endogenous thresholds. See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

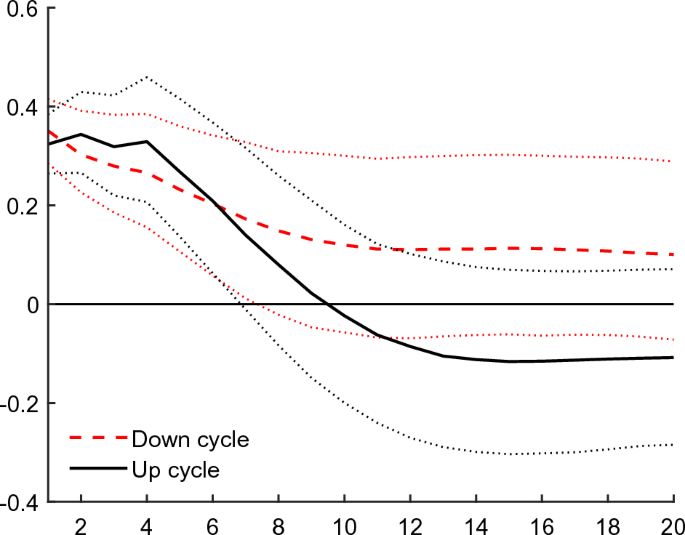

Cumulative fiscal multipliers for total government expenditure. See the note in Fig. 2 for more information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Soederhuizen, B., Teulings, R. & Luginbuhl, R. Estimating the impact of the financial cycle on fiscal policy. Empir Econ 65 , 2669–2709 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-023-02448-0

Download citation

Received : 22 December 2021

Accepted : 24 May 2023

Published : 30 June 2023

Issue Date : December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-023-02448-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Government spending multipliers

- Credit markets

- Financial cycles

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

fiscal policy Recently Published Documents

Total documents.

- Latest Documents

- Most Cited Documents

- Contributed Authors

- Related Sources

- Related Keywords

Does fiscal policy spur environmental issues? New evidence from selected developed countries

Does external debt as a new determinants of fiscal policy influence sustainable economic growth: implications after covid-19, what determine the corporate tax rates during the covid-19 evidence from 113 countries.

Fiscal policy implications become an important tool to soften the negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given this backdrop, this paper analyses the drivers of corporate tax rates during the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., in 2020 and 2021). The results from 113 advanced and developing economies show that a higher level of the COVID-19-related uncertainty is positively associated with the corporate tax rates. Similarly, the country size (measured by total population) increases the corporate tax rates. Per capita income is negatively related to the corporate tax rates, but this evidence is insufficient to consider different estimation techniques. The paper also discusses potential fiscal policy implications for the driving mechanism of corporate tax rates for the post-COVID-19 era.

Fiscal policy and private investment in developing economies: Evidence from Ethiopia

Fiscal policy, monetary policy and price volatility: evidence from an emerging economy.

Vietnam is an Asian emerging country, which now is ranked in the group of the fastest-gro-wing economies worldwide. However, this economy has faced galloping inflation in recent years. So the Vietnamese experience is a valuable reference for the policymakers in the developing world in order to successfully control price volatility. Our study applies the Vector autoregressive method, the Johansen cointegration test, and the Granger causality test to examine the impact of fiscal and monetary policy on price volatility in Vietnam with a quarterly data sample collected over the period from 2004 to 2018. The study results confirm the existence of a long-term cointegration relationship between these policies and price volatility in Vietnam. Besides, the variance decomposition and impulse response function also show that the impact of these policies on inflation is clear, however, the fiscal policy more strongly affects inflation than the monetary policy. Finally, the Granger causality test also indicates one-way causality relationships from the government expenditure as well as the exchange rate to price volatility in the study period.

Italy's presidential vote carries significant risks

Significance One of the front-runners to replace Mattarella is Prime Minister Mario Draghi, who recently gave a strong indication that he intends to run. However, if Draghi is elected president, there does not appear to be an alternative government which could guarantee political stability and make progress on Italy’s crucial reform agenda. Impacts A situation where there is no strong alternative to Draghi’s leadership may boost the electoral appeal of the far-right Brothers of Italy. The return of political instability would diminish Italy’s leverage in the EU regarding important issues such as foreign and fiscal policy. Unless the right-wing parties perform poorly, it is unlikely that Draghi would be elected as prime minister after the next election.

4 Fiscal policy in managing the economic recovery

Fiscal policy and redistribution in a small open economy with aging population, fiscal sustainability and low interest rates: what an indicator can(’t) tell.

AbstractThe indicator that is commonly used to assess the long-term fiscal sustainability of public finances in EU member states (“S2”) is also defined if government borrowing rates are assumed to be permanently lower than the growth rate of GDP. Under these circumstances, however, it no longer provides a reliable orientation for fiscal policy. I illustrate these findings based on simulations prepared for the Fifth Sustainability Report published by the German Federal Ministry of Finance. In addition, I discuss the interpretation of the indicator in a low-interest environment and the assumption that relevant interest rates may continue to be low if there are substantial challenges for fiscal sustainability, e.g., through demographic ageing.

AN EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE OF ECONOMIC RECOVERY DURING THE PANDEMIC PERIOD INTO WORLD ECONOMY

We are in the midst of an asymmetrical recovery. In some countries, COVID-19 infection rates have fallen significantly, while in others, the virus remains difficult to control. But whether governments are actively managing outbreaks or returning to normality, economic recovery is central to their forward-looking agenda without a broad-based economic expansion, it is difficult to address other challenges, such as education and healthcare.The International Monetary Fund(IMF) recently raised its projection for economic growth in 2021 to 6%, up from 5.5%, and projects 4.4% growth in 2022. The upgraded outlook is based on how well the pandemic continues to be controlled, the efficacy of fiscal policy in mitigating economic damage and global financial conditions. Although businesses are the engines of the economy, governments create the environment and structure that enable enterprise to flourish . How governments create and shape the environment for economic recovery—and the opportunities and challenges they face in doing so—will depend on two decisions they make about their approach.

Export Citation Format

Share document.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The aim of this paper is to review the research work conducted on fiscal policies and economic growth, noting that there are two types of fiscal policy; the first type is spending, while the ...

Fiscal policy can also share the stabilisation role with monetary policy, whose effectiveness under the ZLB is much reduced. ... Ramey presents a comprehensive survey on what we have learned in fiscal research since the financial crisis. The paper highlights prominent theoretical analyses, empirical methods and newly constructed data sets ...

The fiscal response to the pandemic will push the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio from 79 percent before it emerged to 110 percent by the end of the 2023 budget year, according to projections she cites ...

Osinowo (2015) focuses on the impact of fiscal policy on the sectoral output growth of Nigeria and finds a positive relationship between fiscal expenditure and output in all the sectors except agriculture. His finding suggests that inflation rate and sectoral outputs are negatively correlated except in manufacturing.

Fiscal Policy in the Age of COVID: Does it 'Get in all of the Cracks?' Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Ṣebnem Kalemli-Özcan, Veronika Penciakova, and Nick Sander NBER Working Paper No. 29293 September 2021 JEL No. C67,D2,E62,E65,F32,F41,G33 ABSTRACT We study the effects of fiscal policy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic at the firm, sector,

Mountford and Uhlig (2009) applied this. approach to examine the effects of fiscal polic y on economic activity in the U.S. and found. that a surprise deficit-financed tax cut is the best fiscal ...

Abstract. Purpose The effectiveness of fiscal policy is an interesting field in literature of macroeconomics. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the effects of fiscal policy on economic growth under contributions from the differences in institutions and external debt levels. Design/methodology/approach The authors use panel data from ...

Abstract. In recent years, a vast literature has appeared on the relationship between fiscal policy and long-run economic growth. With the aim to give an overview of the recent discussion and establish a point of departure for future research, this study used time series techniques and rigor empirical model to investigate the link between various components of fiscal policy on Ethiopia's ...

Fiscal policy in the U.S. and other countries renders intertemporal budgets non-differentiable, nonconvex, and discontinuous. Consequently, assessing work and saving responses to policy requires global optimization. This paper develops the Global Life-Cycle Optimizer (GLO), a stochastic pattern-search algorithm.

Our research follows a growing literature on the linkages between financial markets and fiscal policy. For instance, Afonso et al. use debt-to-GDP ratios to show that expansionary fiscal policy has a larger impact on output during a high-stress regime, potentially as a result of counter-cyclical fiscal policy offsetting reduced credit flows.

Fiscal Policy in a Networked Economy. Joel P. Flynn, Christina Patterson & John Sturm. Working Paper 29619. DOI 10.3386/w29619. Issue Date December 2021. Advanced economies feature complicated networks that connect households, firms, and regions.

Governments and central banks have responded to the pandemic and the economic crisis using both fiscal and monetary tools on a scale that the world has not witnessed before. This paper analyzes the determinants of fiscal and monetary policies during the Covid-19 crisis. We find that high-income countries announced larger fiscal policies than ...

I. Introduction. The question whether and how fiscal policy contributed to stabilizing the economy during the COVID-19 crisis has attracted the interest of researchers and policymakers (e.g. Carvalho, Cardomingo, and Toneto Citation 2021; Deb et al. Citation 2021; Gourinchas et al. Citation 2021).Fiscal policy in advanced economies was significantly countercyclical during the pandemic years ...

Based on the assumption that fiscal policy has an important role in government policy as a GDP determinant, which represents the main conclusion of our previous research, the aim of this paper is to characterize, explain and compare the properties of fiscal policy that government uses in time of crisis in two developing countries, Romania and Turkey.

This paper characterizes optimal fiscal policy in a growth model with incomplete markets, heterogeneous agents (households and entrepreneurs), and idiosyncratic productivity risk. Entrepreneurs run risky production, which they cannot finance optimally because of an agency problem. In the second-best optimum, they issue continuously traded bonds.

This paper examines the role of fiscal policy in the economic growth ensuring in advanced and emerging market economies over the period from 2001 to 2015. The research indicates the growing role of the state (in general) and the budget (in particular) in regulation of social and economic processes. Based on the methods of economic regression ...

The economic implications of government expenditure have been shown to be significant and broad. In particular, government spending has been shown to enhance long-run economic growth by increasing the level of human capital and Research and Development (R&D) expenditure, and by improving public infrastructure. On the other hand, there is evidence that a greater size of government spending may ...

Interactions between monetary and fiscal authorities. Besides estimating the policies of each authority, we also decided to include fiscal (monetary) variables in the monetary (fiscal) regression, in order to highlight, in a different way, the real concerns of national governments and central banks, along the lines of Wyplosz ( 1999 ).

This paper will assist the junior researchers to find the gap and design their future research on fiscal policy as this paper compiles the database of the last five decades available on Scopus ...

This paper—a product of the Public Sector Governance Department—is part of a larger effort in the Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM) Vice-Presidency to encourage active policy research on fiscal policy and growth issues, with a particular focus on expenditure composition choices and their growth and sustainability implications.

We find that on average Covid-19 fiscal spending is 4.97% of GDP. When we include government guarantees in fiscal spending, the average increases to 7.71%. Furthermore, high-income countries - those with GDP per capita above the median in our sample - announced fiscal policies that amount on average to 6.8% of GDP, as.

University in the fall of 2014. His broad research interests are in applied macroeconomics, monetary and fiscal policy, and his doctoral research focuses on the heterogeneous impacts of monetary/fiscal policies over the distribution of heterogeneous firms/households. In the fourth year of his PhD period, Mr.

Produced by the Research Support Team Abstract The Policy Research Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about development issues. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. The papers carry the

Per Capita. Fiscal policy implications become an important tool to soften the negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given this backdrop, this paper analyses the drivers of corporate tax rates during the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., in 2020 and 2021). The results from 113 advanced and developing economies show that a higher level of the ...

He did his M.A and M.Phil from University of Hyderabad, and Ph.D. from Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore. His research areas are macro-monetary economics, fiscal policy, international money & finance, macroeconomic modelling and development economics. In these areas he has authored nearly 70 research papers and five books.