Search form

How to write the best college assignments.

By Lois Weldon

When it comes to writing assignments, it is difficult to find a conceptualized guide with clear and simple tips that are easy to follow. That’s exactly what this guide will provide: few simple tips on how to write great assignments, right when you need them. Some of these points will probably be familiar to you, but there is no harm in being reminded of the most important things before you start writing the assignments, which are usually determining on your credits.

The most important aspects: Outline and Introduction

Preparation is the key to success, especially when it comes to academic assignments. It is recommended to always write an outline before you start writing the actual assignment. The outline should include the main points of discussion, which will keep you focused throughout the work and will make your key points clearly defined. Outlining the assignment will save you a lot of time because it will organize your thoughts and make your literature searches much easier. The outline will also help you to create different sections and divide up the word count between them, which will make the assignment more organized.

The introduction is the next important part you should focus on. This is the part that defines the quality of your assignment in the eyes of the reader. The introduction must include a brief background on the main points of discussion, the purpose of developing such work and clear indications on how the assignment is being organized. Keep this part brief, within one or two paragraphs.

This is an example of including the above mentioned points into the introduction of an assignment that elaborates the topic of obesity reaching proportions:

Background : The twenty first century is characterized by many public health challenges, among which obesity takes a major part. The increasing prevalence of obesity is creating an alarming situation in both developed and developing regions of the world.

Structure and aim : This assignment will elaborate and discuss the specific pattern of obesity epidemic development, as well as its epidemiology. Debt, trade and globalization will also be analyzed as factors that led to escalation of the problem. Moreover, the assignment will discuss the governmental interventions that make efforts to address this issue.

Practical tips on assignment writing

Here are some practical tips that will keep your work focused and effective:

– Critical thinking – Academic writing has to be characterized by critical thinking, not only to provide the work with the needed level, but also because it takes part in the final mark.

– Continuity of ideas – When you get to the middle of assignment, things can get confusing. You have to make sure that the ideas are flowing continuously within and between paragraphs, so the reader will be enabled to follow the argument easily. Dividing the work in different paragraphs is very important for this purpose.

– Usage of ‘you’ and ‘I’ – According to the academic writing standards, the assignments should be written in an impersonal language, which means that the usage of ‘you’ and ‘I’ should be avoided. The only acceptable way of building your arguments is by using opinions and evidence from authoritative sources.

– Referencing – this part of the assignment is extremely important and it takes a big part in the final mark. Make sure to use either Vancouver or Harvard referencing systems, and use the same system in the bibliography and while citing work of other sources within the text.

– Usage of examples – A clear understanding on your assignment’s topic should be provided by comparing different sources and identifying their strengths and weaknesses in an objective manner. This is the part where you should show how the knowledge can be applied into practice.

– Numbering and bullets – Instead of using numbering and bullets, the academic writing style prefers the usage of paragraphs.

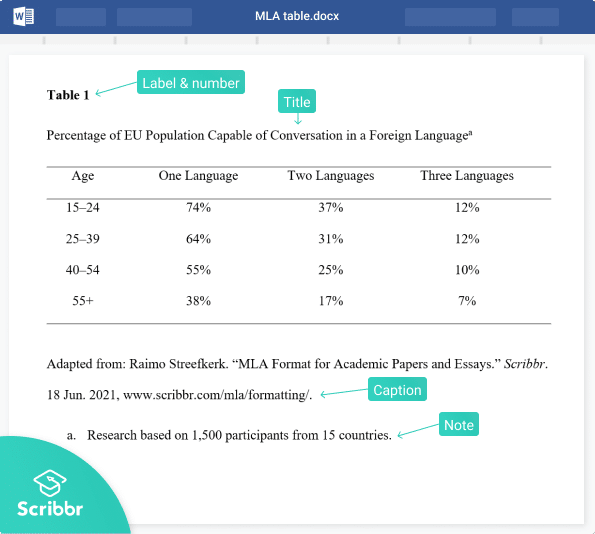

– Including figures and tables – The figures and tables are an effective way of conveying information to the reader in a clear manner, without disturbing the word count. Each figure and table should have clear headings and you should make sure to mention their sources in the bibliography.

– Word count – the word count of your assignment mustn’t be far above or far below the required word count. The outline will provide you with help in this aspect, so make sure to plan the work in order to keep it within the boundaries.

The importance of an effective conclusion

The conclusion of your assignment is your ultimate chance to provide powerful arguments that will impress the reader. The conclusion in academic writing is usually expressed through three main parts:

– Stating the context and aim of the assignment

– Summarizing the main points briefly

– Providing final comments with consideration of the future (discussing clear examples of things that can be done in order to improve the situation concerning your topic of discussion).

Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Table Normal"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif"; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Lois Weldon is writer at Uk.bestdissertation.com . Lives happily at London with her husband and lovely daughter. Adores writing tips for students. Passionate about Star Wars and yoga.

7 comments on “How To Write The Best College Assignments”

Extremely useful tip for students wanting to score well on their assignments. I concur with the writer that writing an outline before ACTUALLY starting to write assignments is extremely important. I have observed students who start off quite well but they tend to lose focus in between which causes them to lose marks. So an outline helps them to maintain the theme focused.

Hello Great information…. write assignments

Well elabrated

Thanks for the information. This site has amazing articles. Looking forward to continuing on this site.

This article is certainly going to help student . Well written.

Really good, thanks

Practical tips on assignment writing, the’re fantastic. Thank you!

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Understanding Writing Assignments

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource describes some steps you can take to better understand the requirements of your writing assignments. This resource works for either in-class, teacher-led discussion or for personal use.

How to Decipher the Paper Assignment

Many instructors write their assignment prompts differently. By following a few steps, you can better understand the requirements for the assignment. The best way, as always, is to ask the instructor about anything confusing.

- Read the prompt the entire way through once. This gives you an overall view of what is going on.

- Underline or circle the portions that you absolutely must know. This information may include due date, research (source) requirements, page length, and format (MLA, APA, CMS).

- Underline or circle important phrases. You should know your instructor at least a little by now - what phrases do they use in class? Does he repeatedly say a specific word? If these are in the prompt, you know the instructor wants you to use them in the assignment.

- Think about how you will address the prompt. The prompt contains clues on how to write the assignment. Your instructor will often describe the ideas they want discussed either in questions, in bullet points, or in the text of the prompt. Think about each of these sentences and number them so that you can write a paragraph or section of your essay on that portion if necessary.

- Rank ideas in descending order, from most important to least important. Instructors may include more questions or talking points than you can cover in your assignment, so rank them in the order you think is more important. One area of the prompt may be more interesting to you than another.

- Ask your instructor questions if you have any.

After you are finished with these steps, ask yourself the following:

- What is the purpose of this assignment? Is my purpose to provide information without forming an argument, to construct an argument based on research, or analyze a poem and discuss its imagery?

- Who is my audience? Is my instructor my only audience? Who else might read this? Will it be posted online? What are my readers' needs and expectations?

- What resources do I need to begin work? Do I need to conduct literature (hermeneutic or historical) research, or do I need to review important literature on the topic and then conduct empirical research, such as a survey or an observation? How many sources are required?

- Who - beyond my instructor - can I contact to help me if I have questions? Do you have a writing lab or student service center that offers tutorials in writing?

(Notes on prompts made in blue )

Poster or Song Analysis: Poster or Song? Poster!

Goals : To systematically consider the rhetorical choices made in either a poster or a song. She says that all the time.

Things to Consider: ah- talking points

- how the poster addresses its audience and is affected by context I'll do this first - 1.

- general layout, use of color, contours of light and shade, etc.

- use of contrast, alignment, repetition, and proximity C.A.R.P. They say that, too. I'll do this third - 3.

- the point of view the viewer is invited to take, poses of figures in the poster, etc. any text that may be present

- possible cultural ramifications or social issues that have bearing I'll cover this second - 2.

- ethical implications

- how the poster affects us emotionally, or what mood it evokes

- the poster's implicit argument and its effectiveness said that was important in class, so I'll discuss this last - 4.

- how the song addresses its audience

- lyrics: how they rhyme, repeat, what they say

- use of music, tempo, different instruments

- possible cultural ramifications or social issues that have bearing

- emotional effects

- the implicit argument and its effectiveness

These thinking points are not a step-by-step guideline on how to write your paper; instead, they are various means through which you can approach the subject. I do expect to see at least a few of them addressed, and there are other aspects that may be pertinent to your choice that have not been included in these lists. You will want to find a central idea and base your argument around that. Additionally, you must include a copy of the poster or song that you are working with. Really important!

I will be your audience. This is a formal paper, and you should use academic conventions throughout.

Length: 4 pages Format: Typed, double-spaced, 10-12 point Times New Roman, 1 inch margins I need to remember the format stuff. I messed this up last time =(

Academic Argument Essay

5-7 pages, Times New Roman 12 pt. font, 1 inch margins.

Minimum of five cited sources: 3 must be from academic journals or books

- Design Plan due: Thurs. 10/19

- Rough Draft due: Monday 10/30

- Final Draft due: Thurs. 11/9

Remember this! I missed the deadline last time

The design plan is simply a statement of purpose, as described on pages 40-41 of the book, and an outline. The outline may be formal, as we discussed in class, or a printout of an Open Mind project. It must be a minimum of 1 page typed information, plus 1 page outline.

This project is an expansion of your opinion editorial. While you should avoid repeating any of your exact phrases from Project 2, you may reuse some of the same ideas. Your topic should be similar. You must use research to support your position, and you must also demonstrate a fairly thorough knowledge of any opposing position(s). 2 things to do - my position and the opposite.

Your essay should begin with an introduction that encapsulates your topic and indicates 1 the general trajectory of your argument. You need to have a discernable thesis that appears early in your paper. Your conclusion should restate the thesis in different words, 2 and then draw some additional meaningful analysis out of the developments of your argument. Think of this as a "so what" factor. What are some implications for the future, relating to your topic? What does all this (what you have argued) mean for society, or for the section of it to which your argument pertains? A good conclusion moves outside the topic in the paper and deals with a larger issue.

You should spend at least one paragraph acknowledging and describing the opposing position in a manner that is respectful and honestly representative of the opposition’s 3 views. The counterargument does not need to occur in a certain area, but generally begins or ends your argument. Asserting and attempting to prove each aspect of your argument’s structure should comprise the majority of your paper. Ask yourself what your argument assumes and what must be proven in order to validate your claims. Then go step-by-step, paragraph-by-paragraph, addressing each facet of your position. Most important part!

Finally, pay attention to readability . Just because this is a research paper does not mean that it has to be boring. Use examples and allow your opinion to show through word choice and tone. Proofread before you turn in the paper. Your audience is generally the academic community and specifically me, as a representative of that community. Ok, They want this to be easy to read, to contain examples I find, and they want it to be grammatically correct. I can visit the tutoring center if I get stuck, or I can email the OWL Email Tutors short questions if I have any more problems.

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Teachers: Creating Writing Assignments

This page contains four specific areas:

Creating Effective Assignments

Checking the assignment, sequencing writing assignments, selecting an effective writing assignment format.

Research has shown that the more detailed a writing assignment is, the better the student papers are in response to that assignment. Instructors can often help students write more effective papers by giving students written instructions about that assignment. Explicit descriptions of assignments on the syllabus or on an “assignment sheet” tend to produce the best results. These instructions might make explicit the process or steps necessary to complete the assignment. Assignment sheets should detail:

- the kind of writing expected

- the scope of acceptable subject matter

- the length requirements

- formatting requirements

- documentation format

- the amount and type of research expected (if any)

- the writer’s role

- deadlines for the first draft and its revision

Providing questions or needed data in the assignment helps students get started. For instance, some questions can suggest a mode of organization to the students. Other questions might suggest a procedure to follow. The questions posed should require that students assert a thesis.

The following areas should help you create effective writing assignments.

Examining your goals for the assignment

- How exactly does this assignment fit with the objectives of your course?

- Should this assignment relate only to the class and the texts for the class, or should it also relate to the world beyond the classroom?

- What do you want the students to learn or experience from this writing assignment?

- Should this assignment be an individual or a collaborative effort?

- What do you want students to show you in this assignment? To demonstrate mastery of concepts or texts? To demonstrate logical and critical thinking? To develop an original idea? To learn and demonstrate the procedures, practices, and tools of your field of study?

Defining the writing task

- Is the assignment sequenced so that students: (1) write a draft, (2) receive feedback (from you, fellow students, or staff members at the Writing and Communication Center), and (3) then revise it? Such a procedure has been proven to accomplish at least two goals: it improves the student’s writing and it discourages plagiarism.

- Does the assignment include so many sub-questions that students will be confused about the major issue they should examine? Can you give more guidance about what the paper’s main focus should be? Can you reduce the number of sub-questions?

- What is the purpose of the assignment (e.g., review knowledge already learned, find additional information, synthesize research, examine a new hypothesis)? Making the purpose(s) of the assignment explicit helps students write the kind of paper you want.

- What is the required form (e.g., expository essay, lab report, memo, business report)?

- What mode is required for the assignment (e.g., description, narration, analysis, persuasion, a combination of two or more of these)?

Defining the audience for the paper

- Can you define a hypothetical audience to help students determine which concepts to define and explain? When students write only to the instructor, they may assume that little, if anything, requires explanation. Defining the whole class as the intended audience will clarify this issue for students.

- What is the probable attitude of the intended readers toward the topic itself? Toward the student writer’s thesis? Toward the student writer?

- What is the probable educational and economic background of the intended readers?

Defining the writer’s role

- Can you make explicit what persona you wish the students to assume? For example, a very effective role for student writers is that of a “professional in training” who uses the assumptions, the perspective, and the conceptual tools of the discipline.

Defining your evaluative criteria

1. If possible, explain the relative weight in grading assigned to the quality of writing and the assignment’s content:

- depth of coverage

- organization

- critical thinking

- original thinking

- use of research

- logical demonstration

- appropriate mode of structure and analysis (e.g., comparison, argument)

- correct use of sources

- grammar and mechanics

- professional tone

- correct use of course-specific concepts and terms.

Here’s a checklist for writing assignments:

- Have you used explicit command words in your instructions (e.g., “compare and contrast” and “explain” are more explicit than “explore” or “consider”)? The more explicit the command words, the better chance the students will write the type of paper you wish.

- Does the assignment suggest a topic, thesis, and format? Should it?

- Have you told students the kind of audience they are addressing — the level of knowledge they can assume the readers have and your particular preferences (e.g., “avoid slang, use the first-person sparingly”)?

- If the assignment has several stages of completion, have you made the various deadlines clear? Is your policy on due dates clear?

- Have you presented the assignment in a manageable form? For instance, a 5-page assignment sheet for a 1-page paper may overwhelm students. Similarly, a 1-sentence assignment for a 25-page paper may offer insufficient guidance.

There are several benefits of sequencing writing assignments:

- Sequencing provides a sense of coherence for the course.

- This approach helps students see progress and purpose in their work rather than seeing the writing assignments as separate exercises.

- It encourages complexity through sustained attention, revision, and consideration of multiple perspectives.

- If you have only one large paper due near the end of the course, you might create a sequence of smaller assignments leading up to and providing a foundation for that larger paper (e.g., proposal of the topic, an annotated bibliography, a progress report, a summary of the paper’s key argument, a first draft of the paper itself). This approach allows you to give students guidance and also discourages plagiarism.

- It mirrors the approach to written work in many professions.

The concept of sequencing writing assignments also allows for a wide range of options in creating the assignment. It is often beneficial to have students submit the components suggested below to your course’s STELLAR web site.

Use the writing process itself. In its simplest form, “sequencing an assignment” can mean establishing some sort of “official” check of the prewriting and drafting steps in the writing process. This step guarantees that students will not write the whole paper in one sitting and also gives students more time to let their ideas develop. This check might be something as informal as having students work on their prewriting or draft for a few minutes at the end of class. Or it might be something more formal such as collecting the prewriting and giving a few suggestions and comments.

Have students submit drafts. You might ask students to submit a first draft in order to receive your quick responses to its content, or have them submit written questions about the content and scope of their projects after they have completed their first draft.

Establish small groups. Set up small writing groups of three-five students from the class. Allow them to meet for a few minutes in class or have them arrange a meeting outside of class to comment constructively on each other’s drafts. The students do not need to be writing on the same topic.

Require consultations. Have students consult with someone in the Writing and Communication Center about their prewriting and/or drafts. The Center has yellow forms that we can give to students to inform you that such a visit was made.

Explore a subject in increasingly complex ways. A series of reading and writing assignments may be linked by the same subject matter or topic. Students encounter new perspectives and competing ideas with each new reading, and thus must evaluate and balance various views and adopt a position that considers the various points of view.

Change modes of discourse. In this approach, students’ assignments move from less complex to more complex modes of discourse (e.g., from expressive to analytic to argumentative; or from lab report to position paper to research article).

Change audiences. In this approach, students create drafts for different audiences, moving from personal to public (e.g., from self-reflection to an audience of peers to an audience of specialists). Each change would require different tasks and more extensive knowledge.

Change perspective through time. In this approach, students might write a statement of their understanding of a subject or issue at the beginning of a course and then return at the end of the semester to write an analysis of that original stance in the light of the experiences and knowledge gained in the course.

Use a natural sequence. A different approach to sequencing is to create a series of assignments culminating in a final writing project. In scientific and technical writing, for example, students could write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic. The next assignment might be a progress report (or a series of progress reports), and the final assignment could be the report or document itself. For humanities and social science courses, students might write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic, then hand in an annotated bibliography, and then a draft, and then the final version of the paper.

Have students submit sections. A variation of the previous approach is to have students submit various sections of their final document throughout the semester (e.g., their bibliography, review of the literature, methods section).

In addition to the standard essay and report formats, several other formats exist that might give students a different slant on the course material or allow them to use slightly different writing skills. Here are some suggestions:

Journals. Journals have become a popular format in recent years for courses that require some writing. In-class journal entries can spark discussions and reveal gaps in students’ understanding of the material. Having students write an in-class entry summarizing the material covered that day can aid the learning process and also reveal concepts that require more elaboration. Out-of-class entries involve short summaries or analyses of texts, or are a testing ground for ideas for student papers and reports. Although journals may seem to add a huge burden for instructors to correct, in fact many instructors either spot-check journals (looking at a few particular key entries) or grade them based on the number of entries completed. Journals are usually not graded for their prose style. STELLAR forums work well for out-of-class entries.

Letters. Students can define and defend a position on an issue in a letter written to someone in authority. They can also explain a concept or a process to someone in need of that particular information. They can write a letter to a friend explaining their concerns about an upcoming paper assignment or explaining their ideas for an upcoming paper assignment. If you wish to add a creative element to the writing assignment, you might have students adopt the persona of an important person discussed in your course (e.g., an historical figure) and write a letter explaining his/her actions, process, or theory to an interested person (e.g., “pretend that you are John Wilkes Booth and write a letter to the Congress justifying your assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” or “pretend you are Henry VIII writing to Thomas More explaining your break from the Catholic Church”).

Editorials . Students can define and defend a position on a controversial issue in the format of an editorial for the campus or local newspaper or for a national journal.

Cases . Students might create a case study particular to the course’s subject matter.

Position Papers . Students can define and defend a position, perhaps as a preliminary step in the creation of a formal research paper or essay.

Imitation of a Text . Students can create a new document “in the style of” a particular writer (e.g., “Create a government document the way Woody Allen might write it” or “Write your own ‘Modest Proposal’ about a modern issue”).

Instruction Manuals . Students write a step-by-step explanation of a process.

Dialogues . Students create a dialogue between two major figures studied in which they not only reveal those people’s theories or thoughts but also explore areas of possible disagreement (e.g., “Write a dialogue between Claude Monet and Jackson Pollock about the nature and uses of art”).

Collaborative projects . Students work together to create such works as reports, questions, and critiques.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.1 Reading and Writing in College

Learning objectives.

- Understand the expectations for reading and writing assignments in college courses.

- Understand and apply general strategies to complete college-level reading assignments efficiently and effectively.

- Recognize specific types of writing assignments frequently included in college courses.

- Understand and apply general strategies for managing college-level writing assignments.

- Determine specific reading and writing strategies that work best for you individually.

As you begin this chapter, you may be wondering why you need an introduction. After all, you have been writing and reading since elementary school. You completed numerous assessments of your reading and writing skills in high school and as part of your application process for college. You may write on the job, too. Why is a college writing course even necessary?

When you are eager to get started on the coursework in your major that will prepare you for your career, getting excited about an introductory college writing course can be difficult. However, regardless of your field of study, honing your writing skills—and your reading and critical-thinking skills—gives you a more solid academic foundation.

In college, academic expectations change from what you may have experienced in high school. The quantity of work you are expected to do is increased. When instructors expect you to read pages upon pages or study hours and hours for one particular course, managing your work load can be challenging. This chapter includes strategies for studying efficiently and managing your time.

The quality of the work you do also changes. It is not enough to understand course material and summarize it on an exam. You will also be expected to seriously engage with new ideas by reflecting on them, analyzing them, critiquing them, making connections, drawing conclusions, or finding new ways of thinking about a given subject. Educationally, you are moving into deeper waters. A good introductory writing course will help you swim.

Table 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments” summarizes some of the other major differences between high school and college assignments.

Table 1.1 High School versus College Assignments

This chapter covers the types of reading and writing assignments you will encounter as a college student. You will also learn a variety of strategies for mastering these new challenges—and becoming a more confident student and writer.

Throughout this chapter, you will follow a first-year student named Crystal. After several years of working as a saleswoman in a department store, Crystal has decided to pursue a degree in elementary education and become a teacher. She is continuing to work part-time, and occasionally she finds it challenging to balance the demands of work, school, and caring for her four-year-old son. As you read about Crystal, think about how you can use her experience to get the most out of your own college experience.

Review Table 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments” and think about how you have found your college experience to be different from high school so far. Respond to the following questions:

- In what ways do you think college will be more rewarding for you as a learner?

- What aspects of college do you expect to find most challenging?

- What changes do you think you might have to make in your life to ensure your success in college?

Reading Strategies

Your college courses will sharpen both your reading and your writing skills. Most of your writing assignments—from brief response papers to in-depth research projects—will depend on your understanding of course reading assignments or related readings you do on your own. And it is difficult, if not impossible, to write effectively about a text that you have not understood. Even when you do understand the reading, it can be hard to write about it if you do not feel personally engaged with the ideas discussed.

This section discusses strategies you can use to get the most out of your college reading assignments. These strategies fall into three broad categories:

- Planning strategies. To help you manage your reading assignments.

- Comprehension strategies. To help you understand the material.

- Active reading strategies. To take your understanding to a higher and deeper level.

Planning Your Reading

Have you ever stayed up all night cramming just before an exam? Or found yourself skimming a detailed memo from your boss five minutes before a crucial meeting? The first step in handling college reading successfully is planning. This involves both managing your time and setting a clear purpose for your reading.

Managing Your Reading Time

You will learn more detailed strategies for time management in Section 1.2 “Developing Study Skills” , but for now, focus on setting aside enough time for reading and breaking your assignments into manageable chunks. If you are assigned a seventy-page chapter to read for next week’s class, try not to wait until the night before to get started. Give yourself at least a few days and tackle one section at a time.

Your method for breaking up the assignment will depend on the type of reading. If the text is very dense and packed with unfamiliar terms and concepts, you may need to read no more than five or ten pages in one sitting so that you can truly understand and process the information. With more user-friendly texts, you will be able to handle longer sections—twenty to forty pages, for instance. And if you have a highly engaging reading assignment, such as a novel you cannot put down, you may be able to read lengthy passages in one sitting.

As the semester progresses, you will develop a better sense of how much time you need to allow for the reading assignments in different subjects. It also makes sense to preview each assignment well in advance to assess its difficulty level and to determine how much reading time to set aside.

College instructors often set aside reserve readings for a particular course. These consist of articles, book chapters, or other texts that are not part of the primary course textbook. Copies of reserve readings are available through the university library; in print; or, more often, online. When you are assigned a reserve reading, download it ahead of time (and let your instructor know if you have trouble accessing it). Skim through it to get a rough idea of how much time you will need to read the assignment in full.

Setting a Purpose

The other key component of planning is setting a purpose. Knowing what you want to get out of a reading assignment helps you determine how to approach it and how much time to spend on it. It also helps you stay focused during those occasional moments when it is late, you are tired, and relaxing in front of the television sounds far more appealing than curling up with a stack of journal articles.

Sometimes your purpose is simple. You might just need to understand the reading material well enough to discuss it intelligently in class the next day. However, your purpose will often go beyond that. For instance, you might also read to compare two texts, to formulate a personal response to a text, or to gather ideas for future research. Here are some questions to ask to help determine your purpose:

How did my instructor frame the assignment? Often your instructors will tell you what they expect you to get out of the reading:

- Read Chapter 2 and come to class prepared to discuss current teaching practices in elementary math.

- Read these two articles and compare Smith’s and Jones’s perspectives on the 2010 health care reform bill.

- Read Chapter 5 and think about how you could apply these guidelines to running your own business.

- How deeply do I need to understand the reading? If you are majoring in computer science and you are assigned to read Chapter 1, “Introduction to Computer Science,” it is safe to assume the chapter presents fundamental concepts that you will be expected to master. However, for some reading assignments, you may be expected to form a general understanding but not necessarily master the content. Again, pay attention to how your instructor presents the assignment.

- How does this assignment relate to other course readings or to concepts discussed in class? Your instructor may make some of these connections explicitly, but if not, try to draw connections on your own. (Needless to say, it helps to take detailed notes both when in class and when you read.)

- How might I use this text again in the future? If you are assigned to read about a topic that has always interested you, your reading assignment might help you develop ideas for a future research paper. Some reading assignments provide valuable tips or summaries worth bookmarking for future reference. Think about what you can take from the reading that will stay with you.

Improving Your Comprehension

You have blocked out time for your reading assignments and set a purpose for reading. Now comes the challenge: making sure you actually understand all the information you are expected to process. Some of your reading assignments will be fairly straightforward. Others, however, will be longer or more complex, so you will need a plan for how to handle them.

For any expository writing —that is, nonfiction, informational writing—your first comprehension goal is to identify the main points and relate any details to those main points. Because college-level texts can be challenging, you will also need to monitor your reading comprehension. That is, you will need to stop periodically and assess how well you understand what you are reading. Finally, you can improve comprehension by taking time to determine which strategies work best for you and putting those strategies into practice.

Identifying the Main Points

In college, you will read a wide variety of materials, including the following:

- Textbooks. These usually include summaries, glossaries, comprehension questions, and other study aids.

- Nonfiction trade books. These are less likely to include the study features found in textbooks.

- Popular magazine, newspaper, or web articles. These are usually written for a general audience.

- Scholarly books and journal articles. These are written for an audience of specialists in a given field.

Regardless of what type of expository text you are assigned to read, your primary comprehension goal is to identify the main point : the most important idea that the writer wants to communicate and often states early on. Finding the main point gives you a framework to organize the details presented in the reading and relate the reading to concepts you learned in class or through other reading assignments. After identifying the main point, you will find the supporting points , the details, facts, and explanations that develop and clarify the main point.

Some texts make that task relatively easy. Textbooks, for instance, include the aforementioned features as well as headings and subheadings intended to make it easier for students to identify core concepts. Graphic features, such as sidebars, diagrams, and charts, help students understand complex information and distinguish between essential and inessential points. When you are assigned to read from a textbook, be sure to use available comprehension aids to help you identify the main points.

Trade books and popular articles may not be written specifically for an educational purpose; nevertheless, they also include features that can help you identify the main ideas. These features include the following:

- Trade books. Many trade books include an introduction that presents the writer’s main ideas and purpose for writing. Reading chapter titles (and any subtitles within the chapter) will help you get a broad sense of what is covered. It also helps to read the beginning and ending paragraphs of a chapter closely. These paragraphs often sum up the main ideas presented.

- Popular articles. Reading the headings and introductory paragraphs carefully is crucial. In magazine articles, these features (along with the closing paragraphs) present the main concepts. Hard news articles in newspapers present the gist of the news story in the lead paragraph, while subsequent paragraphs present increasingly general details.

At the far end of the reading difficulty scale are scholarly books and journal articles. Because these texts are written for a specialized, highly educated audience, the authors presume their readers are already familiar with the topic. The language and writing style is sophisticated and sometimes dense.

When you read scholarly books and journal articles, try to apply the same strategies discussed earlier. The introduction usually presents the writer’s thesis , the idea or hypothesis the writer is trying to prove. Headings and subheadings can help you understand how the writer has organized support for his or her thesis. Additionally, academic journal articles often include a summary at the beginning, called an abstract, and electronic databases include summaries of articles, too.

For more information about reading different types of texts, see Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” .

Monitoring Your Comprehension

Finding the main idea and paying attention to text features as you read helps you figure out what you should know. Just as important, however, is being able to figure out what you do not know and developing a strategy to deal with it.

Textbooks often include comprehension questions in the margins or at the end of a section or chapter. As you read, stop occasionally to answer these questions on paper or in your head. Use them to identify sections you may need to reread, read more carefully, or ask your instructor about later.

Even when a text does not have built-in comprehension features, you can actively monitor your own comprehension. Try these strategies, adapting them as needed to suit different kinds of texts:

- Summarize. At the end of each section, pause to summarize the main points in a few sentences. If you have trouble doing so, revisit that section.

- Ask and answer questions. When you begin reading a section, try to identify two to three questions you should be able to answer after you finish it. Write down your questions and use them to test yourself on the reading. If you cannot answer a question, try to determine why. Is the answer buried in that section of reading but just not coming across to you? Or do you expect to find the answer in another part of the reading?

- Do not read in a vacuum. Look for opportunities to discuss the reading with your classmates. Many instructors set up online discussion forums or blogs specifically for that purpose. Participating in these discussions can help you determine whether your understanding of the main points is the same as your peers’.

These discussions can also serve as a reality check. If everyone in the class struggled with the reading, it may be exceptionally challenging. If it was a breeze for everyone but you, you may need to see your instructor for help.

As a working mother, Crystal found that the best time to get her reading done was in the evening, after she had put her four-year-old to bed. However, she occasionally had trouble concentrating at the end of a long day. She found that by actively working to summarize the reading and asking and answering questions, she focused better and retained more of what she read. She also found that evenings were a good time to check the class discussion forums that a few of her instructors had created.

Choose any text that that you have been assigned to read for one of your college courses. In your notes, complete the following tasks:

- Summarize the main points of the text in two to three sentences.

- Write down two to three questions about the text that you can bring up during class discussion.

Students are often reluctant to seek help. They feel like doing so marks them as slow, weak, or demanding. The truth is, every learner occasionally struggles. If you are sincerely trying to keep up with the course reading but feel like you are in over your head, seek out help. Speak up in class, schedule a meeting with your instructor, or visit your university learning center for assistance.

Deal with the problem as early in the semester as you can. Instructors respect students who are proactive about their own learning. Most instructors will work hard to help students who make the effort to help themselves.

Taking It to the Next Level: Active Reading

Now that you have acquainted (or reacquainted) yourself with useful planning and comprehension strategies, college reading assignments may feel more manageable. You know what you need to do to get your reading done and make sure you grasp the main points. However, the most successful students in college are not only competent readers but active, engaged readers.

Using the SQ3R Strategy

One strategy you can use to become a more active, engaged reader is the SQ3R strategy , a step-by-step process to follow before, during, and after reading. You may already use some variation of it. In essence, the process works like this:

- Survey the text in advance.

- Form questions before you start reading.

- Read the text.

- Recite and/or record important points during and after reading.

- Review and reflect on the text after you read.

Before you read, you survey, or preview, the text. As noted earlier, reading introductory paragraphs and headings can help you begin to figure out the author’s main point and identify what important topics will be covered. However, surveying does not stop there. Look over sidebars, photographs, and any other text or graphic features that catch your eye. Skim a few paragraphs. Preview any boldfaced or italicized vocabulary terms. This will help you form a first impression of the material.

Next, start brainstorming questions about the text. What do you expect to learn from the reading? You may find that some questions come to mind immediately based on your initial survey or based on previous readings and class discussions. If not, try using headings and subheadings in the text to formulate questions. For instance, if one heading in your textbook reads “Medicare and Medicaid,” you might ask yourself these questions:

- When was Medicare and Medicaid legislation enacted? Why?

- What are the major differences between these two programs?

Although some of your questions may be simple factual questions, try to come up with a few that are more open-ended. Asking in-depth questions will help you stay more engaged as you read.

The next step is simple: read. As you read, notice whether your first impressions of the text were correct. Are the author’s main points and overall approach about the same as what you predicted—or does the text contain a few surprises? Also, look for answers to your earlier questions and begin forming new questions. Continue to revise your impressions and questions as you read.

While you are reading, pause occasionally to recite or record important points. It is best to do this at the end of each section or when there is an obvious shift in the writer’s train of thought. Put the book aside for a moment and recite aloud the main points of the section or any important answers you found there. You might also record ideas by jotting down a few brief notes in addition to, or instead of, reciting aloud. Either way, the physical act of articulating information makes you more likely to remember it.

After you have completed the reading, take some time to review the material more thoroughly. If the textbook includes review questions or your instructor has provided a study guide, use these tools to guide your review. You will want to record information in a more detailed format than you used during reading, such as in an outline or a list.

As you review the material, reflect on what you learned. Did anything surprise you, upset you, or make you think? Did you find yourself strongly agreeing or disagreeing with any points in the text? What topics would you like to explore further? Jot down your reflections in your notes. (Instructors sometimes require students to write brief response papers or maintain a reading journal. Use these assignments to help you reflect on what you read.)

Choose another text that that you have been assigned to read for a class. Use the SQ3R process to complete the reading. (Keep in mind that you may need to spread the reading over more than one session, especially if the text is long.)

Be sure to complete all the steps involved. Then, reflect on how helpful you found this process. On a scale of one to ten, how useful did you find it? How does it compare with other study techniques you have used?

Using Other Active Reading Strategies

The SQ3R process encompasses a number of valuable active reading strategies: previewing a text, making predictions, asking and answering questions, and summarizing. You can use the following additional strategies to further deepen your understanding of what you read.

- Connect what you read to what you already know. Look for ways the reading supports, extends, or challenges concepts you have learned elsewhere.

- Relate the reading to your own life. What statements, people, or situations relate to your personal experiences?

- Visualize. For both fiction and nonfiction texts, try to picture what is described. Visualizing is especially helpful when you are reading a narrative text, such as a novel or a historical account, or when you read expository text that describes a process, such as how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

- Pay attention to graphics as well as text. Photographs, diagrams, flow charts, tables, and other graphics can help make abstract ideas more concrete and understandable.

- Understand the text in context. Understanding context means thinking about who wrote the text, when and where it was written, the author’s purpose for writing it, and what assumptions or agendas influenced the author’s ideas. For instance, two writers might both address the subject of health care reform, but if one article is an opinion piece and one is a news story, the context is different.

- Plan to talk or write about what you read. Jot down a few questions or comments in your notebook so you can bring them up in class. (This also gives you a source of topic ideas for papers and presentations later in the semester.) Discuss the reading on a class discussion board or blog about it.

As Crystal began her first semester of elementary education courses, she occasionally felt lost in a sea of new terms and theories about teaching and child development. She found that it helped to relate the reading to her personal observations of her son and other kids she knew.

Writing at Work

Many college courses require students to participate in interactive online components, such as a discussion forum, a page on a social networking site, or a class blog. These tools are a great way to reinforce learning. Do not be afraid to be the student who starts the discussion.

Remember that when you interact with other students and teachers online, you need to project a mature, professional image. You may be able to use an informal, conversational tone, but complaining about the work load, using off-color language, or “flaming” other participants is inappropriate.

Active reading can benefit you in ways that go beyond just earning good grades. By practicing these strategies, you will find yourself more interested in your courses and better able to relate your academic work to the rest of your life. Being an interested, engaged student also helps you form lasting connections with your instructors and with other students that can be personally and professionally valuable. In short, it helps you get the most out of your education.

Common Writing Assignments

College writing assignments serve a different purpose than the typical writing assignments you completed in high school. In high school, teachers generally focus on teaching you to write in a variety of modes and formats, including personal writing, expository writing, research papers, creative writing, and writing short answers and essays for exams. Over time, these assignments help you build a foundation of writing skills.

In college, many instructors will expect you to already have that foundation.

Your college composition courses will focus on writing for its own sake, helping you make the transition to college-level writing assignments. However, in most other college courses, writing assignments serve a different purpose. In those courses, you may use writing as one tool among many for learning how to think about a particular academic discipline.

Additionally, certain assignments teach you how to meet the expectations for professional writing in a given field. Depending on the class, you might be asked to write a lab report, a case study, a literary analysis, a business plan, or an account of a personal interview. You will need to learn and follow the standard conventions for those types of written products.

Finally, personal and creative writing assignments are less common in college than in high school. College courses emphasize expository writing, writing that explains or informs. Often expository writing assignments will incorporate outside research, too. Some classes will also require persuasive writing assignments in which you state and support your position on an issue. College instructors will hold you to a higher standard when it comes to supporting your ideas with reasons and evidence.

Table 1.2 “Common Types of College Writing Assignments” lists some of the most common types of college writing assignments. It includes minor, less formal assignments as well as major ones. Which specific assignments you encounter will depend on the courses you take and the learning objectives developed by your instructors.

Table 1.2 Common Types of College Writing Assignments

Part of managing your education is communicating well with others at your university. For instance, you might need to e-mail your instructor to request an office appointment or explain why you will need to miss a class. You might need to contact administrators with questions about your tuition or financial aid. Later, you might ask instructors to write recommendations on your behalf.

Treat these documents as professional communications. Address the recipient politely; state your question, problem, or request clearly; and use a formal, respectful tone. Doing so helps you make a positive impression and get a quicker response.

Key Takeaways

- College-level reading and writing assignments differ from high school assignments not only in quantity but also in quality.

- Managing college reading assignments successfully requires you to plan and manage your time, set a purpose for reading, practice effective comprehension strategies, and use active reading strategies to deepen your understanding of the text.

- College writing assignments place greater emphasis on learning to think critically about a particular discipline and less emphasis on personal and creative writing.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

College Writing

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you figure out what your college instructors expect when they give you a writing assignment. It will tell you how and why to move beyond the five-paragraph essays you learned to write in high school and start writing essays that are more analytical and more flexible.

What is a five-paragraph essay?

High school students are often taught to write essays using some variation of the five-paragraph model. A five-paragraph essay is hourglass-shaped: it begins with something general, narrows down in the middle to discuss specifics, and then branches out to more general comments at the end. In a classic five-paragraph essay, the first paragraph starts with a general statement and ends with a thesis statement containing three “points”; each body paragraph discusses one of those “points” in turn; and the final paragraph sums up what the student has written.

Why do high schools teach the five-paragraph model?

The five-paragraph model is a good way to learn how to write an academic essay. It’s a simplified version of academic writing that requires you to state an idea and support it with evidence. Setting a limit of five paragraphs narrows your options and forces you to master the basics of organization. Furthermore—and for many high school teachers, this is the crucial issue—many mandatory end-of-grade writing tests and college admissions exams like the SAT II writing test reward writers who follow the five-paragraph essay format.

Writing a five-paragraph essay is like riding a bicycle with training wheels; it’s a device that helps you learn. That doesn’t mean you should use it forever. Once you can write well without it, you can cast it off and never look back.

Why don’t five-paragraph essays work well for college writing?

The way college instructors teach is probably different from what you experienced in high school, and so is what they expect from you.

While high school courses tend to focus on the who, what, when, and where of the things you study—”just the facts”—college courses ask you to think about the how and the why. You can do very well in high school by studying hard and memorizing a lot of facts. Although college instructors still expect you to know the facts, they really care about how you analyze and interpret those facts and why you think those facts matter. Once you know what college instructors are looking for, you can see some of the reasons why five-paragraph essays don’t work so well for college writing:

- Five-paragraph essays often do a poor job of setting up a framework, or context, that helps the reader understand what the author is trying to say. Students learn in high school that their introduction should begin with something general. College instructors call these “dawn of time” introductions. For example, a student asked to discuss the causes of the Hundred Years War might begin, “Since the dawn of time, humankind has been plagued by war.” In a college course, the student would fare better with a more concrete sentence directly related to what he or she is going to say in the rest of the paper—for example, a sentence such as “In the early 14th century, a civil war broke out in Flanders that would soon threaten Western Europe’s balance of power.” If you are accustomed to writing vague opening lines and need them to get started, go ahead and write them, but delete them before you turn in the final draft. For more on this subject, see our handout on introductions .

- Five-paragraph essays often lack an argument. Because college courses focus on analyzing and interpreting rather than on memorizing, college instructors expect writers not only to know the facts but also to make an argument about the facts. The best five-paragraph essays may do this. However, the typical five-paragraph essay has a “listing” thesis, for example, “I will show how the Romans lost their empire in Britain and Gaul by examining military technology, religion, and politics,” rather than an argumentative one, for example, “The Romans lost their empire in Britain and Gaul because their opponents’ military technology caught up with their own at the same time as religious upheaval and political conflict were weakening the sense of common purpose on the home front.” For more on this subject, see our handout on argument .

- Five-paragraph essays are often repetitive. Writers who follow the five-paragraph model tend to repeat sentences or phrases from the introduction in topic sentences for paragraphs, rather than writing topic sentences that tie their three “points” together into a coherent argument. Repetitive writing doesn’t help to move an argument along, and it’s no fun to read.

- Five-paragraph essays often lack “flow.” Five-paragraph essays often don’t make smooth transitions from one thought to the next. The “listing” thesis statement encourages writers to treat each paragraph and its main idea as a separate entity, rather than to draw connections between paragraphs and ideas in order to develop an argument.

- Five-paragraph essays often have weak conclusions that merely summarize what’s gone before and don’t say anything new or interesting. In our handout on conclusions , we call these “that’s my story and I’m sticking to it” conclusions: they do nothing to engage readers and make them glad they read the essay. Most of us can remember an introduction and three body paragraphs without a repetitive summary at the end to help us out.

- Five-paragraph essays don’t have any counterpart in the real world. Read your favorite newspaper or magazine; look through the readings your professors assign you; listen to political speeches or sermons. Can you find anything that looks or sounds like a five-paragraph essay? One of the important skills that college can teach you, above and beyond the subject matter of any particular course, is how to communicate persuasively in any situation that comes your way. The five-paragraph essay is too rigid and simplified to fit most real-world situations.

- Perhaps most important of all: in a five-paragraph essay, form controls content, when it should be the other way around. Students begin with a plan for organization, and they force their ideas to fit it. Along the way, their perfectly good ideas get mangled or lost.

How do I break out of writing five-paragraph essays?

Let’s take an example based on our handout on thesis statements . Suppose you’re taking a course on contemporary communication, and the professor asks you to write a paper on this topic:

Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.

Thanks to your familiarity with the five paragraph essay structure and with the themes of your course, you are able to quickly write an introductory paragraph:

Social media allows the sharing of information through online networks among social connections. Everyone uses social media in our modern world for a variety of purposes: to learn about the news, keep up with friends, and even network for jobs. Social media cannot help but affect public awareness. In this essay, I will discuss the impact of social media on public awareness of political campaigns, public health initiatives, and current events.

Now you have something on paper. But you realize that this introduction sticks too close to the five-paragraph essay structure. The introduction starts too broadly by taking a step back and defining social media in general terms. Then it moves on to restate the prompt without quite addressing it: while it’s reasserted that there is an impact, the impact is not actually discussed. And the final sentence, instead of presenting an argument, only lists topics in sequence. You are prepared to write a paragraph on political campaigns, a paragraph on public health initiatives, and a paragraph on current events, but you aren’t sure what your point will be.

So you start again. Instead of trying to come up with something to say about each of three points, you brainstorm until you come up with a main argument, or thesis, about the impact of social media on public awareness. You think about how easy it is to share information on social media, as well as about how difficult it can be to discern more from less reliable information. As you brainstorm the effects of social media on public awareness in connection to political campaigns specifically, you realize you have enough to say about this topic without discussing two additional topics. You draft your thesis statement:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

Next you think about your argument’s parts and how they fit together. You read the Writing Center’s handout on organization . You decide that you’ll begin by addressing the counterargument that misinformation on social media has led to a less informed public. Addressing the counterargument point-by-point helps you articulate your evidence. You find it ends up taking more than one paragraph to discuss the strategies people use to compare and evaluate information as well as the evidence that people end up more informed as a result.

You notice that you now have four body paragraphs. You might have had three or two or seven; what’s important is that you allowed your argument to determine how many paragraphs would be needed and how they should fit together. Furthermore, your body paragraphs don’t each discuss separate topics, like “political campaigns” and “public health.” Instead they support different points in your argument. This is also a good moment to return to your introduction and revise it to focus more narrowly on introducing the argument presented in the body paragraphs in your paper.

Finally, after sketching your outline and writing your paper, you turn to writing a conclusion. From the Writing Center handout on conclusions , you learn that a “that’s my story and I’m sticking to it” conclusion doesn’t move your ideas forward. Applying the strategies you find in the handout, you may decide that you can use your conclusion to explain why the paper you’ve just written really matters.

Is it ever OK to write a five-paragraph essay?

Yes. Have you ever found yourself in a situation where somebody expects you to make sense of a large body of information on the spot and write a well-organized, persuasive essay—in fifty minutes or less? Sounds like an essay exam situation, right? When time is short and the pressure is on, falling back on the good old five-paragraph essay can save you time and give you confidence. A five-paragraph essay might also work as the framework for a short speech. Try not to fall into the trap, however, of creating a “listing” thesis statement when your instructor expects an argument; when planning your body paragraphs, think about three components of an argument, rather than three “points” to discuss. On the other hand, most professors recognize the constraints of writing blue-book essays, and a “listing” thesis is probably better than no thesis at all.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Blue, Tina. 2001. “AP English Blather.” Essay, I Say (blog), January 26, 2001. http://essayisay.homestead.com/blather.html .

Blue, Tina. 2001. “A Partial Defense of the Five-Paragraph Theme as a Model for Student Writing.” Essay, I Say (blog), January 13, 2001. http://essayisay.homestead.com/fiveparagraphs.html .

Denecker, Christine. 2013. “Transitioning Writers across the Composition Threshold: What We Can Learn from Dual Enrollment Partnerships.” Composition Studies 41 (1): 27-50.

Fanetti, Susan et al. 2010. “Closing the Gap between High School Writing Instruction and College Writing Expectations.” The English Journal 99 (4): 77-83.

Hillocks, George. 2002. The Testing Trap: How State Assessments Control Learning . New York and London: Teachers College Press.

Hjortshoj, Keith. 2009. The Transition to College Writing , 2nd ed. New York: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Shen, Andrea. 2000. “Study Looks at Role of Writing in Learning.” Harvard Gazette (blog). October 26, 2000. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2000/10/study-looks-at-role-of-writing-in-learning/ .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Common Assignments: Journal Entries

Basics of journal entries, related webinar.

Didn't find what you need? Search our website or email us .

Read our website accessibility and accommodation statement .

- Previous Page: Writing a Successful Response to Another's Post

- Next Page: Read the Prompt Carefully

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

APA (7th Edition) Referencing Guide

- Information for EndNote Users

- Authors - Numbers, Rules and Formatting

- In-Text Citations

- Reference List

- Books & eBooks

- Book chapters

- Journal Articles

- Conference Papers

- Newspaper Articles

- Web Pages & Documents

- Specialised Health Databases

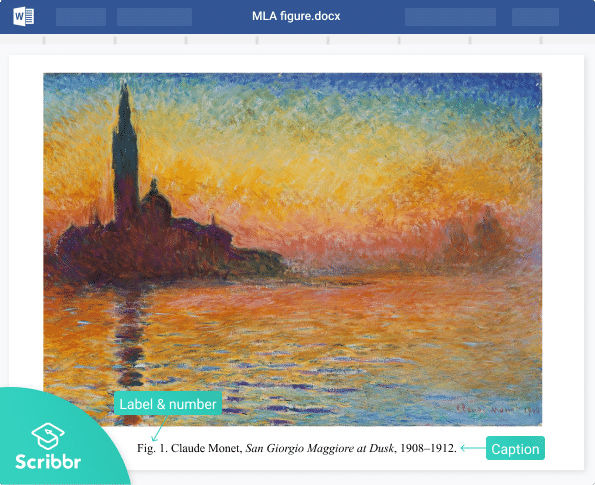

- Using Visual Works in Assignments & Class Presentations

- Using Visual Works in Theses and Publications

- Using Tables in Assignments & Class Presentations

- Custom Textbooks & Books of Readings

- ABS AND AIHW

- Videos (YouTube), Podcasts & Webinars

- Blog Posts and Social Media

- First Nations Works

- Dictionary and Encyclopedia Entries

- Personal Communication

- Theses and Dissertations

- Film / TV / DVD

- Miscellaneous (Generic Reference)

- AI software

APA 7th examples and templates

Apa formatting tips, thesis formatting, tables and figures, acknowledgements and disclaimers.

- What If...?

- Other Guides

You can view the samples here:

- APA Style Sample Papers From the official APA Style and Grammar Guidelines

Quick formatting notes taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association 7th edition

Use the same font throughout the text of your paper, including the title and any headings. APA lists the following options (p. 44):

- Sans serif fonts such as 11-point Calibri, 11 point-Arial, 10-point Lucida,

- Serif fonts such as 12-point Times new Roman, 11-point Georgia or 10-point Computer Modern.

(A serif font is one that has caps and tails - or "wiggly bits" - on it, like Times New Roman . The font used throughout this guide is a sans serif [without serif] font). You may want to check with your lecturer to see if they have a preference.

In addition APA suggests these fonts for the following circumstances:

- Within figures, use a sans serif font between 8 and 14 points.

- When presenting computer code, use a monospace font such as 10-point Lucida Console or 10-point Courier New.

- Footnotes: a 10-point font with single line spacing.

Line Spacing:

"Double-space the entire paper, including the title page, abstract, text, headings, block quotations, reference list, table and figure notes, and appendices, with the following exceptions:" (p. 45)

- Table and figures: Words within tables and figures may be single-, one-and-a-half- or double-spaced depending on what you decide creates the best presentation.

- Footnotes: Footnotes appearing at the bottom of the page to which they refer may be single-spaced and formatted with the default settings on your word processing program i.e. Word.

- Equations: You may triple- or quadruple-space before and after equations.

"Use 1 in. (2.54 cm) margins on all sides (top, bottom, left, and right) of the page." If your subject outline or lecturer has requested specific margins (for example, 3cm on the left side), use those.

"Align the text to the left and leave the right margin uneven ('ragged'). Do not use full justification, which adjusts the spacing between words to make all lines the same length (flush with the margins). Do not manually divide words at the end of a line" (p. 45).

Do not break hyphenated words. Do not manually break long DOIs or URLs.

Indentations:

"Indent the first line of every paragraph... for consistency, use the tab key... the default settings in most word-processing programs are acceptable. The remaining lines of the paragraph should be left-aligned." (p. 45)

Exceptions to the paragraph indentation requirements are as follows:

- Title pages to be centred.

- The first line of abstracts are left aligned (not indented).

- Block quotes are indented 1.27 cm (0.5 in). The first paragraph of a block quote is not indented further. Only the first line of the second and subsequent paragraphs (if there are any) are indented a further 1.27 cm (0.5 in). (see What if...Long quote in this LibGuide)

- Level 1 headings, including appendix titles, are centred. Level 2 and Level 3 headings are left aligned..

- Table and figure captions, notes etc. are flush left.

Page numbers:

Page numbers should be flush right in the header of each page. Use the automatic page numbering function in Word to insert page numbers in the top right-hand corner. The title page is page number 1.

Reference List:

- Start the reference list on a new page after the text but before any appendices.

- Label the reference list References (bold, centred, capitalised).

- Double-space all references.

- Use a hanging indent on all references (first line is flush left, the second and any subsequent lines are indented 1.27 cm (0.5 in). To apply a hanging indent in Word, highlight all of your references and press Ctrl + T on a PC, or Command (⌘) + T on a Mac.

Level 1 Heading - Centered, Bold, Title Case

Text begins as a new paragraph i.e. first line indented...

Level 2 Heading - Flush Left, Bold, Title Case

Level 3 Heading - Flush Left, Bold, Italic, Title Case

Level 4 Heading Indented, Bold, Title Case Heading, Ending With a Full Stop. Text begins on the same line...

Level 5 Heading, Bold, Italic, Title Case Heading, Ending with a Full Stop. Text begins on the same line...

Please note : Any formatting requirements specified in the subject outline or any other document or web page supplied to the students by the lecturers should be followed instead of these guidelines.

What is an appendix?

Appendices contain matter that belongs with your paper, rather than in it.

For example, an appendix might contain

- the survey questions or scales you used for your research,

- detailed description of data that was referred to in your paper,

- long lists that are too unweildy to be given in the paper,

- correspondence recieved from the company you are analysing,

- copies of documents being discussed (if required),

You may be asked to include certain details or documents in appendices, or you may chose to use an appendix to illustrate details that would be inappropriate or distracting in the body of your text, but are still worth presenting to the readers of your paper.

Each topic should have its own appendix. For example, if you have a survey that you gave to participants and an assessment tool which was used to analyse the results of that survey, they should be in different appendices. However, if you are including a number of responses to that survey, do not put each response in a separate appendix, but group them together in one appendix as they belong together.

How do you format an appendix?

Appendices go at the very end of your paper , after your reference list. (If you are using footnotes, tables or figures, then the end of your paper will follow this pattern: reference list, footnotes, tables, figures, appendices).

Each appendix starts on a separate page. If you have only one appendix, it is simply labelled "Appendix". If you have more than one, they are given letters: "Appendix A", "Appendix B", "Appendix C", etc.

The label for your appendix (which is just "Appendix" or "Appendix A" - do not put anything else with it), like your refrerence list, is placed at the top of the page, centered and in bold , beginning with a capital letter.

You then give a title for your appendix, centered and in bold , on the next line.

Use title case for the appendix label and title.

The first paragraph of your appendix is not indented (it is flush with the left margin), but all other paragraphs follow the normal pattern of indenting the first line. Use double line spacing, just like you would for the body of your paper.

How do I refer to my appendices in my paper?

In your paper, when you mention information that will be included or expanded upon in your appendices, you refer to the appendix by its label and capitalise the letters that are capitalised in the label:

Questions in the survey were designed to illicit reflective responses (see Appendix A).

As the consent form in Appendix B illustrates...

How do I use references in my appendices?