- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Mesopotamia

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 24, 2023 | Original: November 30, 2017

Mesopotamia is a region of southwest Asia in the Tigris and Euphrates river system that benefitted from the area’s climate and geography to host the beginnings of human civilization. Its history is marked by many important inventions that changed the world, including the concept of time, math, the wheel, sailboats, maps and writing. Mesopotamia is also defined by a changing succession of ruling bodies from different areas and cities that seized control over a period of thousands of years.

Where is Mesopotamia?

Mesopotamia is located in the region now known as the Middle East, which includes parts of southwest Asia and lands around the eastern Mediterranean Sea. It is part of the Fertile Crescent , an area also known as “Cradle of Civilization” for the number of innovations that arose from the early societies in this region, which are among some of the earliest known human civilizations on earth.

The word “mesopotamia” is formed from the ancient words “meso,” meaning between or in the middle of, and “potamos,” meaning river. Situated in the fertile valleys between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the region is now home to modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, Turkey and Syria .

Mesopotamian Civilization

Humans first settled in Mesopotamia in the Paleolithic era. By 14,000 B.C., people in the region lived in small settlements with circular houses.

Five thousand years later, these houses formed farming communities following the domestication of animals and the development of agriculture, most notably irrigation techniques that took advantage of the proximity of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

Agricultural progress was the work of the dominant Ubaid culture, which had absorbed the Halaf culture before it.

Ancient Mesopotamia

These scattered agrarian communities started in the northern part of the ancient Mesopotamian region and spread south, continuing to grow for several thousand years until forming what modern humans would recognize as cities, which were considered the work of the Sumer people.

Uruk was the first of these cities, dating back to around 3200 B.C. It was a mud brick metropolis built on the riches brought from trade and conquest and featured public art, gigantic columns and temples. At its peak, it had a population of some 50,000 citizens.

Sumerians are also responsible for the earliest form of written language, cuneiform, with which they kept detailed clerical records.

By 3000 B.C., Mesopotamia was firmly under the control of the Sumerian people. Sumer contained several decentralized city-states—Eridu, Nippur, Lagash, Uruk, Kish and Ur.

The first king of a united Sumer is recorded as Etana of Kish. It’s unknown whether Etana really existed, as he and many of the rulers listed in the Sumerian King List that was developed around 2100 B.C. are all featured in Sumerian mythology as well.

Etana was followed by Meskiaggasher, the king of the city-state Uruk. A warrior named Lugalbanda took control around 2750 B.C.

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From the Sphinx of Egypt to the Kama Sutra, explore ancient history videos.

Gilgamesh, the legendary subject of the Epic of Gilgamesh , is said to be Lugalbanda’s son. Gilgamesh is believed to have been born in Uruk around 2700 B.C.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is considered to be the earliest great work of literature and the inspiration for some of the stories in the Bible. In the epic poem, Gilgamesh goes on an adventure with a friend to the Cedar Forest, the land of the Gods in Mesopotamian mythology. When his friend is slain, Gilgamesh goes on a quest to discover the secret of eternal life, finding: "Life, which you look for, you will never find. For when the gods created man, they let death be his share, and life withheld in their own hands."

King Lugalzagesi was the final king of Sumer, falling to Sargon of Akkad, a Semitic people, in 2334 B.C. They were briefly allies, conquering the city of Kish together, but Lugalzagesi’s mercenary Akkadian army was ultimately loyal to Sargon.

Sargon and the Akkadians

The Akkadian Empire existed from 2234-2154 B.C. under the leadership of the now-titled Sargon the Great. It was considered the world’s first multicultural empire with a central government.

Little is known of Sargon’s background, but legends give him a similar origin to the Biblical story of Moses. He was at one point an officer who worked for the king of Kish, and Akkadia was a city that Sargon himself established. When the city of Uruk invaded Kish, Sargon took Kish from Uruk and was encouraged to continue with conquest.

Sargon expanded his empire through military means, conquering all of Sumer and moving into what is now Syria. Under Sargon, trade beyond Mesopotamian borders grew, and architecture became more sophisticated, notably the appearance of ziggurats, flat-topped buildings with a pyramid shape and steps.

The final king of the Akkadian Empire, Shar-kali-sharri, died in 2193 B.C., and Mesopotamia went through a century of unrest, with different groups struggling for control.

Among these groups were the Gutian people, barbarians from the Zagros Mountains. The Gutian rule is considered a disorderly one that caused a severe downturn in the empire’s prospects.

In 2100 B.C. the city of Ur attempted to establish a dynasty for a new empire. The ruler of Ur-Namma, the king of the city of Ur, brought Sumerians back into control after Utu-hengal, the leader of the city of Uruk, defeated the Gutians.

Under Ur-Namma, the first code of law in recorded history, The Code of Ur-Nammu, appeared. Ur-Namma was attacked by both the Elamites and the Amorites and defeated in 2004 B.C.

The Babylonians

Choosing Babylon as the capital, the Amorites took control and established Babylonia .

Kings were considered deities and the most famous of these was Hammurabi , who ruled 1792–1750 B.C. Hammurabi worked to expand the empire, and the Babylonians were almost continually at war.

Hammurabi’s most famous contribution is his list of laws, better known as the Code of Hammurabi , devised around 1772 B.C.

Hammurabi’s innovation was not just writing down the laws for everyone to see, but making sure that everyone throughout the empire followed the same legal codes, and that governors in different areas did not enact their own. The list of laws also featured recommended punishments to ensure that every citizen had the right to the same justice.

In 1750 B.C. the Elamites conquered the city of Ur. Together with the control of the Amorites, this conquest marked the end of Sumerian culture.

The Hittites

The Hittites, who were centered around Anatolia and Syria, conquered the Babylonians around 1595 B.C.

Smelting was a significant contribution of the Hittites, allowing for more sophisticated weaponry that lead them to expand the empire even further. Their attempts to keep the technology to themselves eventually failed, and other empires became a match for them.

The Hittites pulled out shortly after sacking Babylon, and the Kassites took control of the city. Hailing from the mountains east of Mesopotamia, their period of rule saw immigrants from India and Europe arriving, and travel sped up thanks to the use of horses with chariots and carts.

The Kassites abandoned their own culture after a couple of generations of dominance, allowing themselves to be absorbed into Babylonian civilization.

The Assyrians

The Assyrian Empire under the leadership of Ashur-uballit I rose around 1365 B.C. in the areas between the lands controlled by the Hittites and the Kassites.

Around 1220 B.C., King Tukulti-Ninurta I aspired to rule all of Mesopotamia and seized Babylon. The Assyrian Empire continued to expand over the next two centuries, moving into modern-day Palestine and Syria.

Under the rule of Ashurnasirpal II in 884 B.C., the empire created a new capitol, Nimrud, built from the spoils of conquest and brutality that made Ashurnasirpal II a hated figure.

His son Shalmaneser spent the majority of his reign fighting off an alliance between Syria, Babylon and Egypt, and conquering Israel . One of his sons rebelled against him, and Shalmaneser sent another son, Shamshi-Adad, to fight for him. Three years later, Shamshi-Adad ruled.

A new dynasty began in 722 B.C. when Sargon II seized power. Modeling himself on Sargon the Great, he divided the empire into provinces and kept the peace.

His undoing came when the Chaldeans attempted to invade and Sargon II sought an alliance with them. The Chaldeans made a separate alliance with the Elamites, and together they took Babylonia.

Sargon II lost to the Chaldeans but switched to attacking Syria and parts of Egypt and Gaza, embarking on a spree of conquest before eventually dying in battle against the Cimmerians from Russia.

Sargon II’s grandson Esarhaddon ruled from 681 to 669 B.C. and went on a destructive campaign of conquest through Ethiopia, Palestine and Egypt, destroying cities he rampaged through after looting them. Esarhaddon struggled to rule his expanded empire. A paranoid leader, he suspected many in his court of conspiring against him and had them killed.

His son Ashurbanipal is considered to be the final great ruler of the Assyrian empire. Ruling from 669 to 627 B.C., he faced a rebellion in Egypt, losing the territory, and from his brother, the king of Babylonia, whom he defeated. Ashurbanipal is best remembered for creating Mesopotamia’s first library in what is now Nineveh, Iraq. It is the world’s oldest known library, predating the Library of Alexandria by several hundred years.

Nebuchadnezzar

In 626 B.C. the throne was seized by Babylonian public official Nabopolassar, ushering in the rule of the Semitic dynasty from Chaldea. In 616 B.C. Nabopolassar attempted to take Assyria but failed.

His son Nebuchadnezzar reigned over the Babylonian Empire following an invasion effort in 614 B.C. by King Cyaxares of Media that pushed the Assyrians further away.

Nebuchadnezzar is known for his ornate architecture, especially the Hanging Gardens of Babylon , the Walls of Babylon and the Ishtar Gate. Under his rule, women and men had equal rights.

Nebuchadnezzar is also responsible for the conquest of Jerusalem , which he destroyed in 586 B.C., taking its inhabitants into captivity. He appears in the Old Testament because of this action.

The Persian Empire

Persian Emperor Cyrus II seized power during the reign of Nabonidus in 539 B.C. Nabonidus was such an unpopular king that Mesopotamians did not rise to defend him during the invasion.

Babylonian culture is considered to have ended under Persian rule, following a slow decline of use in cuneiform and other cultural hallmarks.

By the time Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire in 331 B.C., most of the great cities of Mesopotamia no longer existed and the culture had been long overtaken. Eventually, the region was taken by the Romans in A.D. 116 and finally Arabic Muslims in A.D. 651.

Mesopotamian Gods

Mesopotamian religion was polytheistic, with followers worshipping several main gods and thousands of minor gods. The three main gods were Ea (Sumerian: Enki), the god of wisdom and magic, Anu (Sumerian: An), the sky god, and Enlil (Ellil), the god of earth, storms and agriculture and the controller of fates. Ea is the creator and protector of humanity in both the Epic of Gilgamesh and the story of the Great Flood.

In the latter story, Ea made humans out of clay, but the God Enlil sought to destroy humanity by creating a flood. Ea had the humans build an ark and mankind was spared. If this story sounds familiar, it should; foundational Mesopotamian religious stories about the Garden of Eden, the Great Flood, and the Creation of the Tower of Babel found their way into the Bible, and the Mesopotamian religion influenced both Christianity and Islam.

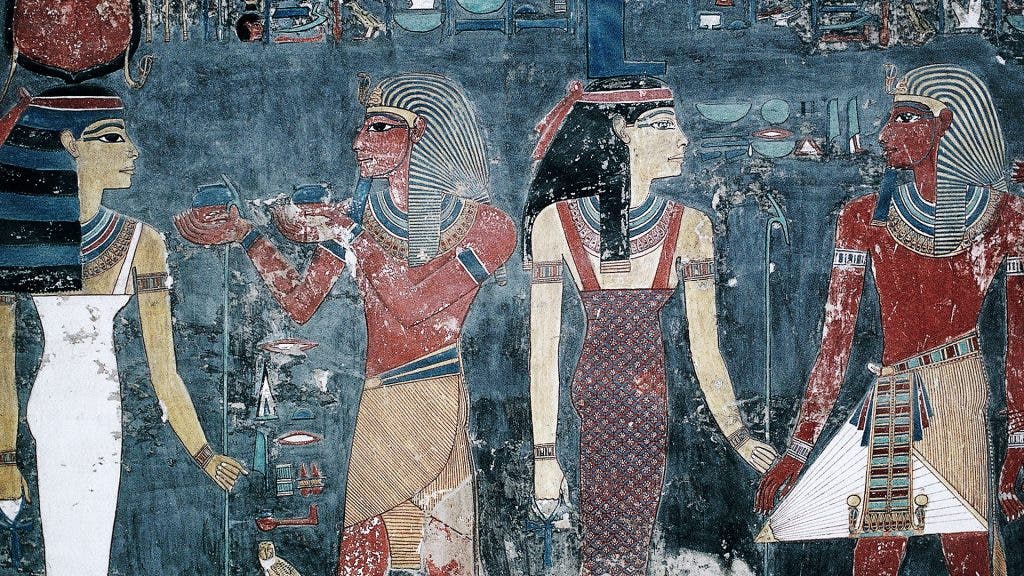

Each Mesopotamian City had its own patron god or goddess, and most of what we know of them has been passed down through clay tablets describing Mesopotamian religious beliefs and practices. A painted terracotta plaque from 1775 B.C. gives an example of the sophistication of Babylonian art, portraying either the goddess Ishtar or her sister Ereshkigal, accompanied by night creatures.

Mesopotamian Art

While making art predates civilization in Mesopotamia, the innovations there include creating art on a larger scale, often in the context of their grandiose and complex architecture, and frequently employing metalwork.

One of the earliest examples of metalwork in art comes from southern Mesopotamia, a silver statuette of a kneeling bull from 3000 B.C. Before this, painted ceramics and limestone were the most common art forms.

Another metal-based work, a goat standing on its hind legs and leaning on the branches of a tree, featuring gold and copper along with other materials, was found in the Great Death Pit at Ur and dates to 2500 B.C.

Mesopotamian art often depicted its rulers and the glories of their lives. Also created around 2500 B.C. in Ur is the intricate Standard of Ur, a shell and limestone structure that features an early example of complex pictorial narrative, depicting a history of war and peace.

In 2230 B.C., Akkadian King Naram-Sin was the subject of an elaborate work in limestone that depicts a military victory in the Zagros Mountains and presents Naram-Sin as divine.

Among the most dynamic forms of Mesopotamian art are the reliefs of the Assyrian kings in their palaces, notably from Ashurbanipal’s reign around 635 B.C. One famous relief in his palace in Nimrud shows him leading an army into battle, accompanied by the winged god Assur.

Ashurbanipal is also featured in multiple reliefs that portray his frequent lion-hunting activity. An impressive lion image also figures into the Ishtar Gate in 585 B.C., during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II and fashioned from glazed bricks.

Mesopotamian art returned to the public eye in the 21st century when museums in Iraq were looted during conflicts there. Many pieces went missing, including a 4,300-year-old bronze mask of an Akkadian king, jewelry from Ur, a solid gold Sumerian harp, 80,000 cuneiform tablets and numerous other irreplaceable items.

Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Paul Kriwaczek . Ancient Mesopotamia. Leo Oppenheim . Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History. University of Chicago . Mesopotamia 8000-2000 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art . 30,000 Years of Art. Editors at Phaidon . Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses. UPenn.edu .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

3.2 Ancient Mesopotamia

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify characteristics of civilization in Ancient Mesopotamia

- Discuss the political history of Mesopotamia from the early Sumerian city-states to the rise of Old Babylon

- Describe the economy, society, and religion of Ancient Mesopotamia

In the fourth millennium BCE, the world’s first great cities arose in southern Mesopotamia , or the land between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, then called Sumer . The ancient Sumerians were an inventive people responsible for a host of technological advances, most notably a sophisticated writing system. Even after the Sumerian language ceased to be spoken early in the second millennium BCE, Sumerian literary works survived throughout the whole of Mesopotamia and were often collected by later cities and stored in the first libraries.

The Rise and Eclipse of Sumer

The term Mesopotamia , or “the land between the rivers” in Greek, likely originated with the Greek historian Herodotus in the fifth century BCE and has become the common name for the place between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in what is now Iraq. The rivers flow north to south, from the Taurus Mountains of eastern Turkey to the Persian Gulf, depositing fertile soil along their banks. Melting snow and rain from the mountains carry this topsoil to the river valleys below. In antiquity, the river flow was erratic, and flooding was frequent but unpredictable. The need to control it and manage the life-giving water led to the building of cooperative irrigation projects.

Agricultural practices reached Mesopotamia by around 8000 BCE, if not earlier. However, for about two millennia afterward, populations remained quite small, typically living in small villages of between one hundred and two hundred people. Beginning around 5500 BCE, some had begun to establish settlements in southern Mesopotamia, a wetter and more forbidding environment. It was here that the Sumerian civilization emerged ( Figure 3.8 ). By around 4500 BCE, some of the once-small farming villages had become growing urban centers, some with thousands of residents. During the course of the fourth millennium BCE (3000s BCE), urbanization exploded in the region. By the end of the millennium, there were at least 124 villages with about one hundred residents each, twenty towns with as many as two thousand residents, another twenty small urban centers of about five thousand residents, and one large city, Uruk , with a population that may have been as high as fifty thousand. This growth helped make Sumer the earliest civilization to develop in Mesopotamia.

The fourth millennium BCE in Sumer was also a period of technological innovation. One important invention made after 4000 BCE was the process for manufacturing bronze, an alloy of tin and copper, which marked the beginning of the Bronze Age in Mesopotamia. In this period, bronze replaced stone as the premier material for tools and weapons and remained so for nearly three thousand years. The ancient Sumerians also developed the plow, the wheel, and irrigation techniques that used small channels and canals with dikes for diverting river water into fields. All these developments allowed for population growth and the continued rise of cities by expanding agricultural production and the distribution of agricultural goods. In the area of science, the Sumerians developed a sophisticated mathematical system based on the numbers sixty, ten, and one.

One of the greatest inventions of this period was writing. The Sumerians developed cuneiform , a script characterized by wedge-shaped symbols that evolved into a phonetic script, that is, one based on sounds, in which each symbol stood for a syllable ( Figure 3.9 ). They wrote their laws, religious tracts, and property transactions on clay tablets, which became very durable once baked, just like the clay bricks the Sumerians used to construct their buildings. The clay tablets held records of commercial exchanges, including contracts and receipts as well as taxes and payrolls. Cuneiform also allowed rulers to record their laws and priests to preserve their rituals and sacred stories. In these ways, it helped facilitate both economic growth and the formation of states.

Dueling Voices

The invention of writing in sumer.

Writing developed independently in several parts of the world, but the earliest known evidence of its birth has been found in Sumer, where cuneiform script emerged as a genuine writing system by around 3000 BCE, if not earlier. But questions remain about how and why ancient peoples began reproducing their spoken language in symbolic form.

Archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat argued in the 1990s that small clay representations of numbers and objects, often called “tokens,” date from thousands of years before the development of cuneiform writing and were its precursor. These tokens, she believed, were part of an accounting system, and each type represented a different good: livestock, grains, and oils. Some were found within hollow baseball-sized clay balls now called “bullae,” which were marked with pictures of the tokens inside. Schmandt-Besserat believed the pictures portray the type of transaction in which the goods represented by the tokens were exchanged, and thus they were a crucial step toward writing. Over time, she suggested, the marked bullae gave way to flat clay tablets recording the transactions, and the first truly written records emerged ( Figure 3.10 ).

Schmandt-Besserat’s linear interpretation is still one of the best-known explanations for the emergence of writing. But it is hardly the only one. One scholar who offers a different idea is the French Assyriologist Jean-Jacques Glassner. Glassner believes that rather than being an extension of accounting techniques, early writing was a purposeful attempt to render the Sumerian language in script. He equates the development of writing, which gives meaning to a symbol, to the process by which Mesopotamian priests interpreted omens for divining the future. Writing allowed people to place language, a creation of the gods, under human control. Glassner’s argument is complex and relies on ancient works of literature and various theoretical approaches, including that of postmodernist philosopher Jacques Derrida.

Many disagree with Glassner’s conclusions, and modern scholars concede that tokens likely played an important role, but probably not in the linear way Schmandt-Besserat proposed. Uncertainty about the origin of writing in Sumer still abounds, and the scholarly debate continues.

- Why do you think Schmandt-Besserat’s argument was once so appealing?

- If you lived in a society with no writing, what might prompt you to develop a way to represent your language in symbolic form?

Cuneiform was a very complex writing system, and literacy remained the monopoly of an elite group of highly trained writing specialists, the scribes. But the script was also highly flexible and could be used to symbolize a great number of sounds, allowing subsequent Mesopotamian cultures such as the Akkadians, Babylonians, and many more to adapt it to their own languages. Since historians deciphered cuneiform in the nineteenth century, they have read the thousands of clay tablets that survived over the centuries and learned much about the history, society, economy, and beliefs of the ancient Sumerians and other peoples of Mesopotamia.

The Sumerians were polytheists , people who revered many gods. Each Sumerian city had its own patron god, however, one with whom the city felt a special connection and whom it honored above the others. For example, the patron god of Uruk was Inanna, the goddess of fertility; the city of Nippur revered the weather god Enlil; and Ur claimed the moon god Sin. Each city possessed an immense temple complex for its special deity, which included a site where the deity was worshipped and religious rituals were performed. This site, the ziggurat , was a stepped tower built of mud-brick with a flat top ( Figure 3.11 ). At its summit stood a roofed structure that housed the sacred idol or image of the temple’s deity. The temple complex also included the homes of the priests, workshops for artisans who made goods for the temple, and storage facilities to meet the needs of the temple workers.

Sumerians were clearly eager to please their gods by placing them at the center of their society. These gods could be fickle, faithless, and easily stirred to anger. If displeased with the people, they might bring famine or conquest. Making sure the gods were praised and honored was thus a way of ensuring prosperity. Praising them, however, implied different things for different social tiers in Sumer . For common people, it meant living a virtuous life and giving to the poor. For priests and priestesses, it consisted of performing the various rituals at the temple complexes. And for rulers honoring the gods, it meant ensuring that the temples were properly funded, maintained, and regularly beautified and enlarged if possible.

By the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2650 BCE–2400 BCE), powerful dynasties of kings called lugals had established themselves as rulers of the cities. In each city, the lugals rose to power primarily as warlords, since the Sumerian cities often waged war against each other for control of farmland and access to water as well as other natural resources. Lugals legitimized their authority through the control of the religious institutions of the city. For example, at Ur, the daughter of the reigning lugal always served as the high priestess of the moon god Sin, the chief deity at Ur.

The lugals at Ur during this period, the so-called First Dynasty of Ur, were especially wealthy, as reflected in the magnificent beehive-shaped tombs in which they were buried. In these tombs, precious goods such as jewelry and musical instruments were stored, along with the bodies of servants who were killed and placed in the tomb to accompany the rulers to the Land of the Dead. One of the more spectacular tombs belonged to a woman of Ur called Pu-Abi, who was buried wearing an elaborate headdress and might have been a queen ( Figure 3.12 ). The most famous lugal in all Sumer in this early period was Gilgamesh of Uruk, whose legendary exploits were recounted later in fantastical form in the Epic of Gilgamesh .

Link to Learning

The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the world’s earliest examples of epic literature. To understand this ancient tale, first written down in the form we know today around 2100 BCE, read the overview of the Epic of Gilgamesh provided by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has a notable collection of ancient Mesopotamian artifacts.

The Rise of the World’s First Empire

Around 2300 BCE, the era of the independent Sumerian city-state , a political entity consisting of a city and surrounding territory that it controls, came to an end. Sumer and indeed all of Mesopotamia was conquered by Sargon of Akkad , who created the first-known empire, in this case, a number of regional powers under the control of one person. The word “Akkad” in his name was a reference to the Akkadians, a group that settled in central Mesopotamia, north of Sumer, around the ancient city of Kish. Over time, the Akkadians adopted Sumerian culture and adapted cuneiform to their own language, a language of the Semitic family that includes the Arabic and Hebrew spoken today. They also identified their own gods with the gods of the Sumerians and adopted Sumerian myths. For example, the Akkadians identified the fertility goddess Inanna with their own goddess Ishtar.

Sargon conquered not only Sumer but also what is today northern Iraq, Syria, and southwestern Iran. While the precise details of his origin and rise to power are not known, scholars believe the story Sargon told about himself, at least, has likely been accurately preserved in the Legend of Sargon , written two centuries after his death as a purported autobiography. It is a familiar story of a scrappy young hero born in humble circumstances and rising on his own merits to become a great leader. The Legend relates how, when Sargon was a baby, his unwed mother put him in a basket and cast it on the Euphrates River. A farmer found and raised him, and Ishtar loved Sargon and elevated him from a commoner to a great king and conqueror.

This interesting tale would have certainly been a powerful piece of propaganda justifying Sargon’s rule and endearing him to the common people, and some of it may even be true. But from what historians can tell, Sargon’s rise to power likely occurred during a period of turmoil as his kingdom of Kish, of which he had likely seized control, came under attack by another king named Lugalzagesi. Sargon’s eventual defeat of Lugalzagesi and conquest of all of Sumer proved to be the beginning of a larger conquest of Mesopotamia. The Akkadian Empire that Sargon created lasted for about a century and a half, officially coming to an end in the year 2193 BCE ( Figure 3.13 ).

One of the rivals of the Akkadian Empire was the city-state of Ebla, located in northwestern Syria. At some point, its people had adapted Sumerian cuneiform to their own language, which, like Akkadian, belonged to the Semitic family of languages, and archaeologists have discovered thousands of cuneiform tablets at the site. These tablets reveal that Ebla especially worshipped the storm god Adad, who was honored with the title “Ba‘al” or lord. More than one thousand years later in the Iron Age, people in this region still worshipped Baal, who was the main rival of Yahweh for the affections of the ancient Israelites.

Other rivals of the Akkadians were the Elamites , who inhabited the region to the immediate southeast of Mesopotamia in southwest Iran and whose city of Susa arose around 4000 BCE. The art and architecture of the Elamites suggest a strong Sumerian influence. They developed their own writing system around 3000 BCE, even though they adapted Sumerian cuneiform to their language later in the third millennium BCE. The Elamites also worshipped their own distinct deities, such as Insushinak, the Lord of the Dead. Both Elam and Ebla eventually suffered defeat at the hands of the Akkadians.

In the year 2193 BCE, however, the Akkadian Empire collapsed. The precise reason is not entirely clear. However, some ancient accounts point to the incursions of the nomadic Guti tribes, whose original homes were located in the Zagros Mountains of northwestern Iran, northwest of Mesopotamia. These Guti were originally pastoralists , who lived off their herds of livestock and moved from place to place to find pasture for their animals. While the Guti tribes certainly did move into the Akkadian Empire toward its end, modern scholarship suggests that the empire was likely experiencing internal decline and famine before this. The Guti appear to have exploited this weakness rather than triggering it. Regardless, for around a century, the Guti ruled over Sumer and adopted its culture as their own. Around 2120 BCE, however, the Sumerians came together under the leadership of the cities of Uruk and Ur and expelled the Guti from their homeland.

Later Empires in Mesopotamia

While Sargon’s empire lasted only a few generations, his conquests dramatically transformed politics in Mesopotamia. The era of independent city-states waned, and over the next few centuries, a string of powerful Mesopotamian rulers were able to build their own empires, often using the administrative techniques developed by Sargon as a model. For example, beginning about 2112 BCE, all Sumer was again united under the Third Dynasty of Ur as the Guti were driven out. The rulers of this dynasty held the title of lugal of all Sumer and Akkad, and they were also honored as gods. They built temples in the Sumerian city of Nippur, which was sacred to the storm god Enlil, the ruler of the gods in the Sumerian pantheon. The most famous lugal of this dynasty was Ur-Nammu (c. 2150 BCE), renowned for his works of poetry as well as for the law code he published.

At its height, the Third Dynasty extended its control over both southern and northern Mesopotamia. But by the end of the third millennium, change was on the horizon. Foreign invaders from the north, east, and west put tremendous pressure on the empire, and its rulers increased their military preparedness and even constructed a 170-mile fortification wall to keep them out. While these strategies were somewhat effective, they appear to have only postponed the inevitable as Amorites, Elamites, and other groups eventually poured in and raided cities across the land. By about 2004 BCE, Sumer had crumbled, and even Ur was violently sacked by the invaders.

The sack of Ur by the Elamites and others was the inspiration for a lament or song of mourning that became a classic of Sumerian literature. Read The Lament for Urim and pay attention to the way the writer attributes the destruction to the caprice of the gods; the actual invaders are merely tools. For descriptions of the destruction itself, focus on lines 161–229.

In the centuries after 2004 BCE, the migration of Amorites into Mesopotamia resulted in the gradual disappearance of Sumerian as a spoken language. People in the region came to speak Amorite, which belonged to the family of Semitic languages. Nonetheless, scribes continued to preserve and write works in Sumerian and Akkadian cuneiform. Sumerian and Akkadian became the languages of religious rituals, hymns, and prayers, as well as classic literary works such as the Epic of Gilgamesh . Consequently, the literary output of these earlier cultures was preserved and transmitted to the new settlers. When nomadic Amorite tribes settled in Mesopotamia, they eventually established new cities such as Mari, Asshur, and Babylon, and they adopted much of the culture they encountered. The ancient Sumerian cities of Larsa and Isin of this era also preserved these cultural traditions, even as they came under the rule of Amorite kings.

Hammurabi , the energetic ruler of Babylon during the first half of the eighteenth century BCE, defeated the kings of the rival cities of Mari and Larsa and created an empire that encompassed nearly all of Mesopotamia. To unify this new empire, Hammurabi initiated the construction of irrigation projects, built new temples at Nippur, and published his legal edicts throughout his realm. Hammurabi had these edicts inscribed on stone pillars erected in different places in the empire to inform his subjects about proper behavior and the laws of the land. Being especially clear, the Code of Hammurabi far outlived the king who created it. It also provides us with a fascinating window into how Mesopotamian society functioned at this time.

In Their Own Words

The law in old babylon.

Remarkable for its clarity, the Code of Hammurabi may have introduced concepts like the presumption of innocence and the use of evidence. It informed legal systems in Mesopotamia for many centuries after Hammurabi’s death ( Figure 3.14 ).

The Code of Hammurabi promoted the principle that punishment should fit the crime, but penalties often depended on social class:

199. If [a man] put out the eye of a man’s slave, or break the bone of a man’s slave, he shall pay one-half of its value. 202. If any one strike the body of a man higher in rank than he, he shall receive sixty blows with an ox-whip in public. Many edicts concern marriage, adultery, children, and marriage property. 129. If a man’s wife be surprised with another man, both shall be tied and thrown into the water, but the husband may pardon his wife and the king his slaves. 150. If a man give his wife a field, garden, and house and a deed therefor, if then after the death of her husband the sons raise no claim, then the mother may bequeath all to one of her sons whom she prefers, and need leave nothing to his brothers.

A good number of the code’s edicts concern the settling of commercial disputes:

9. If anyone lose an article, and find it in the possession of another [who says] “A merchant sold it to me, I paid for it before witnesses,” . . . The judge shall examine their testimony—both of the witnesses before whom the price was paid, and of the witnesses who identify the lost article on oath. The merchant is then proved to be a thief and shall be put to death. The owner of the lost article receives his property, and he who bought it receives the money he paid from the estate of the merchant. 48. If anyone owe a debt for a loan, and a storm prostrates the grain, or the harvest fail, or the grain does not grow for lack of water; in that year he need not give his creditor any grain, he washes his debt-tablet in water and pays no rent for this year. —"Hammurabi’s Code of Laws,” c. 1780 BCE, translated by L.W. King

- What do these edicts suggest about the different social tiers in Babylonian society? How were they organized?

- Was marriage similar to or different from marriage today?

- Do the edicts for resolving economic disputes seem fair to you? Why or why not?

While Hammurabi’s empire lasted a century and a half, much of the territory he conquered began falling away from Babylon’s control shortly after he died. The empire continued to dwindle in size until 1595 BCE, when an army of Hittites from central Anatolia in the north (modern Turkey) sacked the city of Babylon. Shortly thereafter, Kassites from the Zagros Mountains of northwestern Iran conquered Babylon and southern Mesopotamia and settled there, unlike the Hittites who had returned to their Anatolian home. The Kassites established a dynasty that ruled over Babylon for nearly five hundred years, to the very end of the Bronze Age . Like the Guti and the Amorites before them, over time, the Kassite rulers adopted the culture of their Mesopotamian subjects.

Society and Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia

Thanks to the preservation of cuneiform clay tablets and the discovery and translation of law codes and works of literature, historians have at their disposal a wealth of information about Mesopotamian society. The study of these documents and the archaeological excavations carried out in Mesopotamia have allowed them to reconstruct the empire’s economy.

We know now that temples and royal palaces were not merely princely residences and places for religious rituals; they also functioned as economic redistribution centers. For example, agricultural goods were collected from farmers as taxes by civic and religious officials, who then stored them to provide payments to the artisans and merchants they employed. Palaces and temples thus needed to possess massive storage facilities. Scribes kept records in cuneiform of all the goods collected and distributed by these institutions. City gates served as areas where farmers, artisans, and merchants could congregate and exchange goods. Precious metals such as gold often served as a medium of exchange, but these goods had to be weighed and measured during commercial exchanges, since coinage and money as we understand it today did not emerge until the Iron Age, a millennium later.

Society in southern Mesopotamia was highly urban. About 70 to 80 percent of the population lived in cities, but not all were employed as artisans, merchants, or other traditional urban roles. Rather, agriculture and animal husbandry accounted for a majority of a city’s economic production. Much of the land was controlled by the temples, kings, or other powerful landowners and was worked by semi-free peasants who were tied to the land. The rest of the land included numerous small plots worked by the free peasants who made up about half the population. A much smaller portion was made up of enslaved people, typically prisoners of war or persons who had committed crimes or gone into debt. A man could sell his own children into slavery to cover a debt.

Much of the hard labor performed in the fields was done by men and boys, while the wives, mothers, and daughters of merchants and artisans were sometimes fully engaged in running family businesses. Cuneiform tablets tell us that women oversaw the business affairs of their families, especially when husbands were merchants who often traveled far from home. For example, cuneiform tablets from circa 1900 BCE show that merchants from Ashur in northern Mesopotamia conducted trade with central Anatolia and wrote letters to their female family members back home. Women were also engaged in the production of textiles like wool and linen. They not only produced these textiles in workshops with their own hands, but some appear to have held managerial positions within the textile industry.

Free peasant farmers, artisans, and merchants were all commoners. This put them in a higher social position than the semi-free peasants and slaves but lower than the elite nobility, who made up a very small percentage of the population and whose ranks included priests, official scribes, and military leaders. This aristocratic elite often received land in payment for their services to the kings and collected rents in kind from their peasant tenants. Social distinctions were also reflected in the law. For example, aspects of Hammurabi’s law code called for punishments for causing physical harm to another to be equal to the harm inflicted. This principle is best summarized in the line “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” However, the principle applied only to victims and perpetrators of the same social class. An aristocrat convicted of the murder of a fellow noble paid with their life, while an aristocrat who harmed or murdered a commoner might be required only to pay a fine.

Men and women were not equal under the Code of Hammurabi . A man was free to have multiple wives and divorce a wife at will, whereas a woman could divorce her husband only if she could prove he had been unkind to her without reason. However, a woman from a family of means could protect her position in a marriage if her family put up a dowry, which could be land or goods. Upon marriage, the husband obtained the dowry, but if he divorced or was unkind to his wife, he had to return it to her and her family.

Cuneiform tablets have also allowed historians to read stories about the gods and heroes of Mesopotamian cultures. Mesopotamians revered many different gods associated with forces of nature. These were anthropomorphic deities who not only had divine powers but also frequently acted on very human impulses like anger, fear, annoyance, and lust. Examples include Utu, the god of the sun ( Figure 3.15 ); Inanna (known to the Akkadians as Ishtar), the goddess of fertility; and Enlil (whose equivalent in other Mesopotamian cultures was Marduk), the god of wind and rain. The ancient Mesopotamians held that the gods were visible in the sky as heavenly bodies like stars, the moon, the sun, and the planets. This belief led them to pay close attention to these bodies, and over time, they developed a sophisticated understanding of their movement. This knowledge allowed them to predict astronomical events like eclipses and informed their development of a twelve-month calendar.

People in Mesopotamia believed human beings were created to serve the gods ( Figure 3.16 ). They were expected to supply the gods with food through the sacrifice of sheep and cattle in religious rituals, and to honor them with temples, religious songs or hymns, and expensive gifts. People sought divine support from their gods. But they also feared that their worship might be insufficient and anger the deity. When that happened, the gods could bring death and devastation through floods and pestilence. Stories of gods wreaking great destruction, sometimes for petty reasons, are common in Mesopotamian myths. For example, in one Sumerian myth, the storm god Enlil nearly destroyed the entire human race with a flood when the noise made by humans annoyed him and kept him from sleep.

The ancient Mesopotamians’ belief that the gods were fickle, destructive, and easily stirred to anger is one reason many historians believe they had a generally pessimistic worldview. From the literature they left behind, we can see that while they hoped for the best, they were often resigned to accept the worst. Given the environment in which Mesopotamian civilization emerged, this pessimism is somewhat understandable. River flooding was common and could often be unpredictable and destructive. Wars between city-states and the destruction that comes with conflict were also common. Life was difficult in this unforgiving world, and the profiles of the various gods of the Mesopotamians reflect this harsh reality.

Evidence of Mesopotamians’ pessimism is also present in their view of the afterlife. In their religion, after death all people spent eternity in a shadowy underworld sometimes called “the land of no return.” Descriptions of this place differ somewhat in the details, but the common understanding was that it was a gloomy and frightening place where the dead were consumed by sorrow, eating dust and clay and longing pitifully and futilely to return to the land of the living.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/world-history-volume-1/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Ann Kordas, Ryan J. Lynch, Brooke Nelson, Julie Tatlock

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: World History Volume 1, to 1500

- Publication date: Apr 19, 2023

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/world-history-volume-1/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/world-history-volume-1/pages/3-2-ancient-mesopotamia

© Dec 13, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Mesopotamian creation myths.

Ira Spar Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Stories describing creation are prominent in many cultures of the world. In Mesopotamia, the surviving evidence from the third millennium to the end of the first millennium B.C. indicates that although many of the gods were associated with natural forces, no single myth addressed issues of initial creation. It was simply assumed that the gods existed before the world was formed. Unfortunately, very little survives of Sumerian literature from the third millennium B.C. Several fragmentary tablets contain references to a time before the pantheon of the gods, when only the Earth (Sumerian: ki ) and Heavens (Sumerian: an ) existed. All was dark, there existed neither sunlight nor moonlight; however, the earth was green and water was in the ground, although there was no vegetation. More is known from Sumerian poems that date to the beginning centuries of the second millennium B.C.

A Sumerian myth known today as “ Gilgamesh and the Netherworld” opens with a mythological prologue. It assumes that the gods and the universe already exist and that once a long time ago the heavens and earth were united, only later to be split apart. Later, humankind was created and the great gods divided up the job of managing and keeping control over heavens, earth, and the Netherworld.

The origins of humans are described in another early second-millennium Sumerian poem, “The Song of the Hoe.” In this myth, as in many other Sumerian stories, the god Enlil is described as the deity who separates heavens and earth and creates humankind. Humanity is formed to provide for the gods, a common theme in Mesopotamian literature.

In the Sumerian poem “The Debate between Grain and Sheep,” the earth first appeared barren, without grain, sheep, or goats. People went naked. They ate grass for nourishment and drank water from ditches. Later, the gods created sheep and grain and gave them to humankind as sustenance. According to “The Debate between Bird and Fish,” water for human consumption did not exist until Enki, lord of wisdom, created the Tigris and Euphrates and caused water to flow into them from the mountains. He also created the smaller streams and watercourses, established sheepfolds, marshes, and reedbeds, and filled them with fish and birds. He founded cities and established kingship and rule over foreign countries. In “The Debate between Winter and Summer,” an unknown Sumerian author explains that summer and winter, abundance, spring floods, and fertility are the result of Enlil’s copulation with the hills of the earth.

Another early second-millennium Sumerian myth, “Enki and the World Order,” provides an explanation as to why the world appears organized. Enki decided that the world had to be well managed to avoid chaos. Various gods were thus assigned management responsibilities that included overseeing the waters, crops, building activities, control of wildlife, and herding of domestic animals, as well as oversight of the heavens and earth and the activities of women.

According to the Sumerian story “Enki and Ninmah,” the lesser gods, burdened with the toil of creating the earth, complained to Namma, the primeval mother, about their hard work. She in turn roused her son Enki, the god of wisdom, and urged him to create a substitute to free the gods from their toil. Namma then kneaded some clay, placed it in her womb, and gave birth to the first humans.

Babylonian poets, like their Sumerian counterparts, had no single explanation for creation. Diverse stories regarding creation were incorporated into other types of texts. Most prominently, the Babylonian creation story Enuma Elish is a theological legitimization of the rise of Marduk as the supreme god in Babylon, replacing Enlil, the former head of the pantheon. The poem was most likely compiled during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in the later twelfth century B.C., or possibly a short time afterward. At this time, Babylon , after many centuries of rule by the foreign Kassite dynasty , achieved political and cultural independence. The poem celebrates the ascendancy of the city and acts as a political tractate explaining how Babylon came to succeed the older city of Nippur as the center of religious festivals.

The poem itself has 1,091 lines written on seven tablets. It opens with a theogony, the descent of the gods, set in a time frame prior to creation of the heavens and earth. At that time, the ocean waters, called Tiamat, and her husband, the freshwater Apsu, mingled, with the result that several gods emerged in pairs. Like boisterous children, the gods produced so much noise that Apsu decided to do away with them. Tiamat, more indulgent than her spouse, urged patience, but Apsu, stirred to action by his vizier, was unmoved. The gods, stunned by the prospect of death, called on the resourceful god Ea to save them. Ea recited a spell that made Apsu sleep. He then killed Apsu and captured Mummu, his vizier. Ea and his wife Damkina then gave birth to the hero Marduk, the tallest and mightiest of the gods. Marduk, given control of the four winds by the sky god Anu, is told to let the winds whirl. Picking up dust, the winds create storms that upset and confound Tiamat. Other gods suddenly appear and complain that they, too, cannot sleep because of the hurricane winds. They urge Tiamat to do battle against Marduk so that they can rest. Tiamat agrees and decides to confront Marduk. She prepares for battle by having the mother goddess create eleven monsters. Tiamat places the monsters in charge of her new spouse, Qingu, who she elevates to rule over all the gods. When Ea hears of the preparations for battle, he seeks advice from his father, Anshar, king of the junior gods. Anshar urges Ea and afterward his brother Anu to appease the goddess with incantations. Both return frightened and demoralized by their failure. The young warrior god Marduk then volunteers his strength in return for a promise that, if victorious, he will become king of the gods. The gods agree, a battle ensues, and Marduk vanquishes Tiamat and Qingu, her host. Marduk then uses Tiamat’s carcass for the purpose of creation. He splits her in half, “like a dried fish,” and places one part on high to become the heavens, the other half to be the earth. As sky is now a watery mass, Marduk stretches her skin to the heavens to prevent the waters from escaping, a motif that explains why there is so little rainfall in southern Iraq. With the sky now in place, Marduk organizes the constellations of the stars. He lays out the calendar by assigning three stars to each month, creates his own planet, makes the moon appear, and establishes the sun, day, and night. From various parts of Tiamat’s body, he creates the clouds, winds, mists, mountains, and earth.

The myth continues as the gods swear allegiance to the mighty king and create Babylon and his temple, the Esagila, a home where the gods can rest during their sojourn upon the earth. The myth conveniently ignores Nippur, the holy city esteemed by both the Sumerians and the rulers of Kassite Babylonia . Babylon has replaced Nippur as the dwelling place of the gods.

Meanwhile, Marduk fulfills an earlier promise to provide provisions for the junior gods if he gains victory as their supreme leader. He then creates humans from the blood of Qingu, the slain and rebellious consort of Tiamat. He does this for two reasons: first, in order to release the gods from their burdensome menial labors, and second, to provide a continuous source of food and drink to temples.

The gods then celebrate and pronounce Marduk’s fifty names, each an aspect of his character and powers. The composition ends by stating that this story and its message (presumably the importance of kingship to the maintenance of order) should be preserved for future generations and pondered by those who are wise and knowledgeable. It should also be used by parents and teachers to instruct so that the land may flourish and its inhabitants prosper.

The short tale “Marduk, Creator of the World” is another Babylonian narrative that opens with the existence of the sea before any act of creation. First to be created are the cities, Eridu and Babylon, and the temple Esagil is founded. Then the earth is created by heaping dirt upon a raft in the primeval waters. Humankind, wild animals, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the marshlands and canebrake, vegetation, and domesticated animals follow. Finally, palm groves and forests appear. Just before the composition becomes fragmentary and breaks off, Marduk is said to create the city of Nippur and its temple, the Ekur, and the city of Uruk, with its temple Eanna.

“The Creation of Humankind” is a bilingual Sumerian- Akkadian story also referred to in scholarly literature as KAR 4. This account begins after heaven was separated from earth, and features of the earth such as the Tigris, Euphrates, and canals established. At that time, the god Enlil addressed the gods asking what should next be accomplished. The answer was to create humans by killing Alla-gods and creating humans from their blood. Their purpose will be to labor for the gods, maintaining the fields and irrigation works in order to create bountiful harvests, celebrate the gods’ rites, and attain wisdom through study.

Spar, Ira. “Mesopotamian Creation Myths.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/epic/hd_epic.htm (April 2009)

Further Reading

Black, J. A., G. Cunningham, E. Flückiger-Hawker, E. Robson, and G. Zólyomi, trans. The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature .. Oxford: , 1998–2006.

Foster, Benjamin R. Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature . 3d ed.. Bethesda, Md.: CDL Press, 2005.

Jacobsen, Thorkild. The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

Jacobsen, Thorkild, trans. and ed. The Harps That Once . . . : Sumerian Poetry in Translation . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

Lambert, W. G. "Mesopotamian Creation Stories." In Imagining Creation , edited by Markham J. Geller and Mineke Schipper, pp. 17–59. IJS Studies in Judaica 5.. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

Lambert, W. G., and Alan R. Millard. Atra-Hasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood . Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

Additional Essays by Ira Spar

- Spar, Ira. “ Flood Stories .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ Gilgamesh .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ Mesopotamian Deities .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ The Gods and Goddesses of Canaan .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ The Origins of Writing .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Flood Stories

- The Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian Periods (2004–1595 B.C.)

- Mesopotamian Deities

- The Akkadian Period (ca. 2350–2150 B.C.)

- Art of the First Cities in the Third Millennium B.C.

- Assyria, 1365–609 B.C.

- Early Excavations in Assyria

- The Gods and Goddesses of Canaan

- The Middle Babylonian / Kassite Period (ca. 1595–1155 B.C.) in Mesopotamia

- The Old Assyrian Period (ca. 2000–1600 B.C.)

- The Origins of Writing

- Mesopotamia, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Mesopotamia, 1–500 A.D.

- Mesopotamia, 2000–1000 B.C.

- Mesopotamia, 8000–2000 B.C.

- 10th Century B.C.

- 1st Century B.C.

- 2nd Century B.C.

- 2nd Millennium B.C.

- 3rd Century B.C.

- 3rd Millennium B.C.

- 4th Century B.C.

- 5th Century B.C.

- 6th Century B.C.

- 7th Century B.C.

- 8th Century B.C.

- 9th Century B.C.

- Agriculture

- Akkadian Period

- Ancient Near Eastern Art

- Aquatic Animal

- Architecture

- Astronomy / Astrology

- Babylonian Art

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Kassite Period

- Literature / Poetry

- Mesopotamian Art

- Mythical Creature

- Religious Art

- Sumerian Art

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

The Cuneiform Writing System in Ancient Mesopotamia: Emergence and Evolution

Detailed map of ancient Mesopotamia.

Wikimedia Commons

The earliest writing systems evolved independently and at roughly the same time in Egypt and Mesopotamia, but current scholarship suggests that Mesopotamia’s writing appeared first. That writing system, invented by the Sumerians, emerged in Mesopotamia around 3500 BCE. At first, this writing was representational: a bull might be represented by a picture of a bull, and a pictograph of barley signified the word barley. Though writing began as pictures, this system was inconvenient for conveying anything other than simple nouns, and it became increasingly abstract as it evolved to encompass more abstract concepts, eventually taking form in the world’s earliest writing: cuneiform. An increasingly complex civilization encouraged the development of an increasingly sophisticated form of writing. Cuneiform came to function both phonetically (representing a sound) and semantically (representing a meaning such as an object or concept) rather than only representing objects directly as a picture.

This lesson plan, intended for use in the teaching of world history in the middle grades, is designed to help students appreciate the parallel development and increasing complexity of writing and civilization in the Tigris and Euphrates valleys in ancient Mesopotamia. You may wish to use this lesson independently as an introduction to Mesopotamian civilization, or as an entry point into the study of Sumerian and Babylonian history and culture.

Guiding Questions

How did cuneiform writing emerge and evolve in ancient Mesopotamia?

How did the cuneiform writing system affect Mesopotamian civilization?

Learning Objectives

Identify specific artifacts that demonstrate how the writing system in Mesopotamia was transformed.

Analyze the purposes writing served in Mesopotamia with an emphasis on how those purposes evolved as the civilization changed.

Evaluate the extent to which the development of systems of writing and the development of civilization are linked.

Lesson Plan Details

The earliest known civilization developed along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in what is now the country of Iraq. The development of successful agriculture, which relied on the region’s fertile soils and an irrigation system that took advantage of its consistent water supply, led to the development of the world’s first cities. The development of stable agriculture through irrigation meant people no longer had to follow changing sources of food. With this stability farmers in the region were able to domesticate animals such as goats, sheep, and cattle. They successfully grew crops of barley and other grains, from which they began to produce dietary staples and other products, such as bread and beer. As their agricultural practices became more successful, farmers were able to create surpluses. In order to ensure the crop yield, a system of canals was dug to divert water for agriculture and lessen the impact of annual floods. With these advances, a significant population of successful farmers, herders, and traders were able to move beyond subsistence agriculture. A series of successive kingdoms—Sumer, Akkadia (also spelled Accadia), Assyria, Babylonia—built cities with monumental architecture, in which trade and commerce were thriving, and even early forms of plumbing were invented for the ruling class.

The development of trade was one of several important factors in Mesopotamia that created a need for writing. The development of complex societies, with social hierarchies, private property, economies that supported tax-funded authorities, and trade, all combined to create a need for written records. The increasingly sophisticated system of writing that developed also helped the civilization develop further, facilitating the management of complex commercial, religious, political, and military systems.

The earliest known writing originated with the Sumerians about 5500 years ago. Writing was not invented for telling stories of the great conquests of kings or for important legal documents. Instead, the earliest known writing documented simple commercial transactions.

The evolution of writing occurred in stages. In its earliest form, commercial transactions were represented by tokens. A sale of four sheep was represented by four tokens designed to signify sheep. At first such tokens were made of stone. Later, they were created from clay. Tokens were stored as a record of transactions.

In the next stage of development, pictographs (simple pictures of an object) were drawn into wet clay, and these images replaced the tokens. Scribes no longer drew four sheep pictographs to represent four sheep. Instead, the numeral for four was written beside one sheep pictograph.

Through this process writing was becoming disentangled from direct depiction. More complicated number systems began to develop. The pictographic symbols were refined into the writing system known as cuneiform. The English word cuneiform comes from the Latin cuneus , meaning “wedge.” Using cuneiform, written symbols could be quickly made by highly trained scribes through the skillful use of the wedge-like end of a reed stylus. Eventually, writing became phonetic as well as representational. Once the writing system had moved from being pictographic to phonetic writing could communicate abstractions more effectively: names, words, and ideas. With cuneiform, writers could tell stories, relate histories, and support the rule of kings. Cuneiform was used to record literature such as the Epic of Gilgamesh—the oldest epic still known. Furthermore, cuneiform was used to communicate and formalize legal systems, most famously Hammurabi’s Code.

NCSS.D1.2.6-8. Explain points of agreement experts have about interpretations and applications of disciplinary concepts and ideas associated with a compelling question. NCSS. D2.Geo.7.6-8. Explain how changes in transportation and communication technology influence the spatial connections among human settlements and affect the diffusion of ideas and cultural practices. NCSS.D2.His.1.6-8. Analyze connections among events and developments in broader historical contexts. NCSS.D2.His.2.6-8. Classify series of historical events and developments as examples of change and/or continuity. NCSS.D2.His.3.6-8. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to analyze why they, and the developments they shaped, are seen as historically significant. NCSS.D3.3.6-8. Identify evidence that draws information from multiple sources to support claims, noting evidentiary limitations.

- For additional detailed information on the development of writing in Mesopotamia, read the Introduction to the Cuneiform Collection available through the EDSITEment resource Internet Public Library.

- Review all websites and materials students will view. Download photographs of artifacts students will be viewing offline. Download and prepare as necessary handouts from the downloadable PDF for this lesson.

- Egyptian Symbols and Figures: Hieroglyphs

- The Alphabet is Historic

Activity 1. Why the Fertile Crescent?

This Crash Course World History video on Mesopotamia provides a quick, but comprehensive background to get students ready to investigate the materials and activities provided below.

This first activity will introduce students to the part of the world where writing first developed- the area once called Mesopotamia, which was located in what is today the country of Iraq. The earliest cities known today arose in Mesopotamia, an area that is part of what is sometimes called the Fertile Crescent. What clues can we get from the geography of the region to explain why Mesopotamia became the “Cradle of Civilization”? Share with the students the British Museum’s introduction to Mesopotamia: Geography , available through the EDSITEment-reviewed resource The Oriental Institute: The University of Chicago . Then use the Geography: Explore feature to investigate a variety of maps of the region by choosing them from the pull down menu.

- With which of these cities are you familiar?

- What do you notice about the locations of these modern cities?

- Where were most of the cities located? Why there?

- How does their location compare with that of the contemporary cities?

- Look to the northeast of Mesopotamia. Why is that area not as hospitable to agriculture? The southwest?

- Mesopotamia was agriculturally rich. Why did vibrant trade develop in the larger region shown on the map? One reason is that although the area was rich in agriculture, it was poor in many natural resources?

- What elements in the terrain also enabled Mesopotamia to develop trade (pay particular attention to the rivers, relatively flat terrain)?

Activity 2. Mesopotamia Timeline

In this activity students will be introduced to the time period in which the first writing developed, and the major events which coincided with this development in ancient Mesopotamia. The National Geographic

includes images, maps, and timelines relevant to the start of this activity.

Distribute the Timeline: Mesopotamia 4000-1000 BCE activity which is available as a PDF for this lesson, or you can do this as an online activity . Note that the timeline covers an extended period, not all of which will be covered in detail in this lesson. This activity will give students who have not had readings about the history of the Middle East, and specifically about Mesopotamia, the opportunity to gain some contextual understanding of the development of cuneiform writing. For students who have had the opportunity to learn about Mesopotamia this exercise will remind them of some of the major events in the history of the area.

Distribute the Timeline Labels handout, which is available as a PDF for this lesson. If practical you may wish to project the timeline onto a screen or redraw the timeline on the board.

As a class, look through the labels. Which do students hypothesize would appear earlier/later on the timeline?

Divide the class into small groups of three or four and assign each group one of the labels. Students can scan through the two summaries of key events in Mesopotamian history that are available on the EDSITEment web resource Metropolitan Museum of Art:

- Key Events 8000-2000 BCE

- Key Events 2000-1000 BCE

These timelines of key events can be used by students to determine where each label should be placed and to indicate when certain innovations became important.

Note: Cuneiform continued to be used in Mesopotamia well into the first millennium BCE, however, as this lesson is concentrating on the early development of the writing system the timeline in this activity will end before cuneiform writing ceased to be used.

Moving in chronological order, place the labels on the timeline. Each group should work together to provide any additional information about the development that was in the event summary. Challenge students to put together a simple narrative of developments in the Tigris-Euphrates River Valley based on the events in the timeline.

What developments in the civilization would have been facilitated by or even require a system of writing?

Activity 3. Jobs in Mesopotamia

In this activity students will begin to think about the development and urbanization of Mesopotamian civilization by thinking about the kinds of occupations that developed over time. Students will also begin to think about the relationship between the evolution of civilization in Mesopotamia and how writing enhanced its development.

Students have probably already studied in their classes about the shift of human societies from the nomadic pursuit of game and wild vegetation, to settled cultivation, and eventually towards settled villages, towns, and cities. As societies became, first, more settled as farmers, and then in certain places more urbanized as some populations became townsfolk, what kinds of new tasks and jobs would need to be done?

Ask students to return to their timeline worksheets. Based on what students learned from the timeline activity, what do they think are some jobs that probably existed in ancient Mesopotamia: Farmer? Trader? Ruler? Builder? Others? Divide the class into small groups and have each group work together to create a list of jobs they believe might have existed in ancient Mesopotamia. Ask each group to contribute one job to a running list that will be written on the board. You may wish to go around the room two or three times.

You can download a list of some occupations which were part of life in ancient Mesopotamia. This is not a comprehensive list, but it will give your class an idea of what life in ancient Mesopotamia was like. You can use this list as a point of comparison with the list that the class has compiled. Students may be surprised to discover which occupations were and were not part of life in ancient Mesopotamia. Ask students to think about the following questions:

- What are some jobs the students did not list?

- What are some jobs students wouldn’t expect to be on the list, such as factory worker?

- What jobs on the list no longer exist?

- Which jobs are unfamiliar to students?

- Were the students surprised to learn some of the listed jobs existed in ancient Mesopotamia?

- Which occupations do they think were the most common? Why?

- Which of the jobs on the list are part of an industry, trade, or profession with a need for record keeping? Explain your answers.

Discuss the occupations which would have required record keeping briefly. You may wish to discuss the role of the priestly class in ancient Mesopotamia, as elite, Mesopotamian priests had a far more expanded role in society than students may have experienced with members of the clergy today. The priests of ancient Mesopotamia were part of the ruling class, and much of the tax money that was collected went to the priests and the temples. Next, have students discuss the following questions. You may wish to have them work together in small groups.

- Would it have been possible to complete the tasks of these occupations without being able to write anything down? How?

- If there were no written records connected to these occupations how would that have affected the occupation?

- How might it have made it easier? How might it have made it harder?

- Do students think that the appearance of these occupations might have affected the development of writing? How?

Activity 4. Thinking About Writing

The above video is an excerpt from the film The Cyrus Cylinder and provides an overview of the origins of cuneiform.

In addition to the historical basis for these activities, this lesson is also about the nature of written language, how it evolves and how it serves civilization.

Ask the students the purposes of writing in the world today. You may wish to have them discuss questions such as:

- Where is writing used as the primary communication device?

- What information does it convey?

- When is it used in addition to other forms of communication-like speaking?

- For what do they use written forms of communication?

Next, ask them to imagine that in an instant all knowledge of alphabetic writing disappeared. Only the drawing of simple pictures remained as the means of written communication. Have the class brainstorm: What would be some of the most essential things for which you would need signs? Which objects, concepts and ideas are the ones you would make sure were standardized and learned right away?

Review the list of essential signs that the class has compiled. Have students create a few of them and draw them on the board. See if a few volunteers can use these “standardized” signs to put together a message someone else in the class will actually understand. Discuss examples of messages relatively easy to communicate with pictographs and others that would be more difficult. Using the signs you’ve made up today, and assuming you had thousands more like them, could you write:

- Your name? (Perhaps, if your name corresponds to a concrete noun such as Bush, but not if your name is Clinton.

- Verbs like: walk, run, fly?

- Adjectives like: delicious, lovely, awesome?

- The words: “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness?

- A Man and a Woman

- Through the Wire

- You Don’t Know My Name

Ask students to discuss the following questions:

- What does picture writing do well? Students may note that pictographs can represent nouns, small numbers, and some prepositions—“Two men on horseback.”

- What advantages does picture writing have? Students may note that even those without specialized knowledge could potentially understand it.

- What are its weaknesses? Students should note that pictographic images have a limited ability to communicate such things as abstractions, sounds and certain parts of speech.

- Can a pictograph convey what the word it is depicting sounds like?

Writing in ancient Mesopotamia arose from necessity—specifically, the need to keep records. Gradually, civilization in the Tigris-Euphrates River Valley became more urbanized. Eventually, a number of complex systems developed: political, military, religious, legal, and commercial. Writing developed as well, becoming essential to those systems.

Did writing enable those complex systems to arise or did complex systems create the need for a more sophisticated system of writing? Ask students to recall a time they started to do a task and then realized at some point that they should have been writing things down? For example, they might imagine organizing a collection of trading cards by writing down categories. Did writing change the way they approached the task? For example, they might think of deciding to make lists of the cards by category. They could do the task without writing, but writing would better enable them to do it—now the cards are organized by category and there’s a list to check against to identify lost cards. Ask students to think about the following questions as they track the evolution of civilization and writing in ancient Mesopotamia:

- What kinds of tasks can be accomplished without writing?

- What kinds of tasks cannot be accomplished without writing?

- Could a country be ruled, an army trained, a religion organized, laws maintained, buildings built, products marketed, crops raised and sold without writing?

- How does writing enhance the ability to do those things?

Activity 5. Barley and the Story of Writing

In this activity students will be introduced to the world’s first writing system—cuneiform—as they work through the British Museum's Mesopotamia site interactive online activity The Story of Writing , available through the EDSITEment resource The Oriental Institute: The University of Chicago .

Introduce the activity by asking students to think about our word “barley.” How many students know what barley is? How is it used? What does it look like in its natural state? You may wish to sketch barley on the board, or show a photograph of barley, such as this photograph .

Barley was a very important crop in ancient Mesopotamia. A pictograph, a pictorial representation of barley—presumably like the one you’ve drawn on the board -- is one of the signs we find on the oldest examples of writing from the region. The first Mesopotamian written representation of barley was a picture. Ask students to think about and discuss the following questions:

- What’s the relationship between the way our word “barley” looks and barley itself?

- What are the elements of our word for barley -- how do we know that the symbols which make up the word represent the grain?

Students should come to the idea that in the written word “barley” it is the phonetic representations of the sounds of the word as we say it that connect the written word to the concept. Barley in Mesopotamia was called “she.”

Next, navigate with the class, or have students navigate on their own, through The Story of Writing website. Each page contains information on the history and development of the cuneiform character for the word "barley" over time. Students should complete the quiz Treasure Hunt: Bowling for Barley .

When students have completed the answers to the treasure hunt have the class discuss the answers to each of the questions, which are available in the teacher’s rubric . Have students answer the following questions in class discussion. For larger classes you may wish to divide the class into small groups and have each group work on answering one of the following questions, which they should share with the rest of the class.